Abstract

Objectives

Albumin-adjusted total calcium is often used as a surrogate marker for free calcium to evaluate hypocalcaemia or hypercalcaemia. Many adjustment formulas based on simple linear regression models have been published, and continue to be used in spite of questionable diagnostic accuracy. In the hope of finding a more pure albumin effect on total calcium, we used multiple linear regression models to adjust for other relevant variables. The regression coefficients of albumin were used to construct local adjustment formulas, and we tested whether the diagnostic accuracy was improved compared with previously published formulas and unadjusted calcium.

Design

A retrospective hospital laboratory data study.

Data sources

The local hospital laboratory data system.

Setting

Norway, 2006–2015.

Participants

6549 patients above 2 years of age, where free calcium standardised at pH 7.40, total calcium, creatinine, albumin and phosphate had been analysed in a single blood draw, including hospitalised patients and patients from outpatient clinics and general practice.

Main outcome measures

Diagnostic accuracy by Harrell’s c and receiver operating characteristic curve analysis, using free calcium standardised at pH 7.40 as a gold standard, in subgroups with estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) ≥60 or <60 mL/min/1.73 m2.

Results

In the subgroup with eGFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2, the Harrell’s c of unadjusted total calcium (0.801) was significantly larger than those of the local formulas (0.790, p=0.002) and the best formula taken from literature (0.791, p=0.004). In the subgroup with eGFR ≥60 mL/min/1.73 m2, no significant differences were found between these three formulas.

Conclusions

Our study shows that the diagnostic accuracy of unadjusted total calcium is superior to several commonly used adjustment formulas, and we suggest that the use of such formulas should be abandoned in clinical practice. If the clinician does not trust total calcium to reflect the calcium status of the patient, free calcium should be measured.

Keywords: albumin, calcium

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Albumin-adjusted total calcium is often used as a surrogate marker for free calcium, to evaluate hypocalcaemia or hypercalcaemia. Many adjustment formulas have been published, and continue to be used in spite of questionable diagnostic accuracy in various patient populations.

The diagnostic accuracy was evaluated using free calcium as the gold standard, both as a dichotomous one (with receiver operating characteristic curve analysis (ROC)) and as a continuous gold standard (with Harrell’s c index), the latter providing less loss of information, but corresponding to ROC area under curve (AUC) when the gold standard is binary.

This study includes a large group of both hospitalised and ambulant patients from a large regional hospital, representative of a broad spectrum of disease.

No diagnostic information of the population was available, and a limited number of variables were included, as we wanted to retain a large sample size.

Introduction

Disturbances in calcium homeostasis are not uncommon in hospitalised patients,1 2 although the exact prevalence in the general population is unknown. All calcium atoms in the body are ionised. In plasma, only 50% of the calcium ions are free to exert biological effects, whereas the rest are bound to proteins, mostly albumin, and a few per cent are bound in complexes with anions like lactate and citrate.3 The concentration of free calcium ions (hereafter named ‘free calcium’) is closely regulated, and patients with abnormal albumin concentrations may have a normal concentration of free calcium despite abnormal concentration of total calcium. Unfortunately, free calcium is not as easily measured as total calcium, the latter being a part of routine test panels of large automatic clinical chemistry instruments. Accordingly, clinicians often try to compensate for an abnormal concentration of albumin, by calculating an albumin-adjusted calcium value, that is, the clinician asks “What would be this patient’s concentration of total calcium if the albumin concentration were normal?” Changes in the concentration of free calcium due to acidaemia or alkalaemia are disregarded in these cases. Several adjustment formulas have been used,4–7 and continue to be so,8 in spite of their rather questionable diagnostic accuracy,9 which may be worse than that of unadjusted calcium in certain populations.10

It is not completely clear why these adjustment formulas perform so poorly. Some speculate that a certain formula is only valid for specific patient populations,10 others that a certain formula may only be valid for certain analytical methods.11 We hypothesise a more fundamental flaw—that the adjustment formulas are based on wrongly formulated regression models. These formulas are estimated from patient populations with a range of total calcium and albumin concentrations, where the investigators have regressed the concentration of total calcium against albumin, using simple linear regression.4 5 The regression coefficient of albumin, usually in the range of 0.018–0.025,6 then shows how much the total concentration of calcium is expected to change for one unit change in albumin concentration, comparing two hypothetical patients with different albumin concentrations. However, when making an albumin adjustment, we should use a coefficient that shows how much the total concentration of calcium is expected to change for one unit change in albumin concentration, when the patient’s condition is otherwise unchanged, specifically when the concentration of free calcium is unchanged. To estimate that coefficient, we have to regress the concentration of total calcium against albumin and free calcium, sex, age or whatever explanatory variable is relevant, not only albumin. Then, the interpretation of the albumin coefficient gets in line with its use.

The purpose of this study was (1) to estimate regression coefficients for albumin from regression models which include the concentration of free calcium and other relevant explanatory variables, and (2) to test whether the regression coefficients from these models yielded albumin-adjusted calcium values of better diagnostic accuracy than that of published formulas and unadjusted calcium.

Material and methods

Material

Data from our laboratory database were collected retrospectively, from 1 January 2006 to 18 September 2015 from all available patient records where the analysis of total calcium, free calcium standardised at pH 7.40, creatinine, albumin and phosphate had been performed in samples from the same blood draw (6567 patients). Only a single dataset (the oldest) from each patient was included. This included samples from both hospitalised patients and patients from outpatient clinics and general practice. No clinical information was collected. The population included very few critically ill patients, as free calcium in those patients was monitored using blood gas instruments in the intensive care units and the analytical results were not transferred to the laboratory information system. All samples were analysed at our laboratory at St.Olavs hospital, Trondheim, Norway, a full service acute care hospital.

Sample handling for analysis of free calcium

Almost all samples, from both hospitalised and ambulatory patients, consisted of venous blood drawn anaerobically into serum gel tubes with minimal use of stasis and muscle contraction, centrifuged with stopper in place within 1 hour and analysed within 24 hours after blood draw. Rarely, some samples from hospitalised patients or ambulatory patients may have been obtained anaerobically using blood gas syringes with electrolyte-balanced heparin. In these cases, the samples were analysed within 30 min after blood draw. Only samples with pH within 7.20–7.60 were accepted for analysis.

Laboratory analyses

Albumin, total calcium, creatinine and phosphate were assayed by colorimetric methods on fully automated Modular P800 or Roche Cobas 6000 c501 instruments (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany). The bromocresol green method was used for albumin. The creatinine assay was an enzymatic method calibrated against an isotope dilution mass spectrometry reference method. The concentration of free calcium was measured by an ion-selective electrode mounted in an automated blood gas analyser (ABL 725 or ABL 825, Radiometer, Copenhagen, Denmark) and standardised at pH 7.40. Standard internal and external quality control procedures were followed for all analytical methods.

Reference ranges

Reference ranges for total calcium are 2.15–2.51 mmol/L12 and 1.18–1.32 mmol/L for free calcium,13 whereas our laboratory use age-specific and sex-specific reference ranges for albumin and creatinine.12 14 15

Patient involvement

There was no direct patient involvement in the development, design or conduct of the study.

Statistical analysis

The dataset was divided into subgroups with estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) below or above 60 mL/min/1.73 m2, as others have found different albumin coefficients in individuals with renal failure compared with individuals with normal renal function.16 We used the full age spectrum (FAS) equation to calculate eGFR,17 because the FAS equation is valid for both children (above 2 years of age) and adults. Values of eGFR above 200 mL/min/1.73 m2 were truncated at that level.18 In addition, for patients with eGFR ≥60 mL/min/1.73 m2, we divided the dataset according to albumin concentrations below or above 30 g/L, as locally weighted scatter plot smoothing of total calcium against albumin indicated non-linearity overall, but linearity below and above 30 g/L. No such non-linear trend was observed for patients with eGFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2.

This procedure resulted in three subgroups. For each subgroup, we created albumin-adjustment formulas: Adjusted calcium=calcium+coefficient×(40−albumin), where the subgroup-specific albumin coefficients were estimated using multiple linear regression models with total calcium as the dependent variable and free calcium, albumin, phosphate, eGFR, gender, age and hospitalisation (or not) as the explanatory variables. We used backwards elimination until all remaining explanatory variables were statistically significant (p<0.05). We also used simple linear regression with total calcium as the dependent variable and albumin as the sole explanatory variable, to estimate unadjusted albumin coefficients.

The diagnostic accuracy of albumin-adjusted calcium calculated from the local formulas was compared to unadjusted total calcium and six other adjustment formulas, taken from literature.4–7 19 20 First, we used free calcium as a dichotomous gold standard to compare the diagnostic accuracies with receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis, where the patients were classified as hypocalcaemic or not, and hypercalcaemic or not, according to four different definitions of the diagnoses (cut points for hypocalcaemia: 1.12, 1.14, 1.16 and 1.18 mmol/L, and for hypercalcaemia: 1.26, 1.28, 1.30 and 1.32 mmol/L). Second, we used free calcium as a continuous gold standard with Harrell’s c index as a measure of diagnostic accuracy. This index is related to the area under the ROC curve. Both measures are 0.5 at no diagnostic accuracy and 1.0 at perfect diagnostic accuracy. Harrell’s c takes on the same value as the area under the ROC curve when the gold standard is binary.21 The diagnostic accuracy was studied for subgroups with eGFR below or above 60 mL/min/1.73 m2.

Laboratory data were extracted using SAS (V.9.2 for Windows) and analysed using STATA (V.14.1 for Windows, StataCorp). Harrell’s c index was calculated by the ‘somersd’ procedure and differences between two indexes by the ‘lincom’ procedure. Differences between proportions were tested by the χ2 test and differences between medians by the Mann-Whitney U test. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Clinical data

Data from a total of 6567 patients were collected, from 3895 women (59.3%) and 2672 men (40.7%). We excluded 18 patients below 2 years of age, as the FAS eGFR equation is validated for individuals aged 2 years or older.17 Characteristics of the 6549 included patients are given in table 1. The hospitalised patients differed significantly from the outpatients in all characteristics.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study population

| Characteristic | Inpatients | Outpatients | P values |

| Number of individuals | 778 | 5771 | |

| Per cent women | 45.1 | 61.2 | <0.0001 |

| Age (years) | 67 (7–90) | 47 (13–82) | <0.0001 |

| Total calcium (mmol/L) | 2.22 (1.61–3.03) | 2.31 (2.09–2.61) | <0.0001 |

| Per cent hypocalcaemia | 35.2 | 5.2 | < 0.0001 |

| Per cent hypercalcaemia | 10.8 | 5.4 | < 0.0001 |

| Free calcium (mmol/L) | 1.19 (0.85–1.67) | 1.23 (1.13–1.39) | <0.0001 |

| Per cent hypocalcaemia | 41.7 | 9.2 | < 0.0001 |

| Per cent hypercalcaemia | 11.3 | 5.3 | < 0.0001 |

| Albumin (g/L) | 33 (18–45) | 41 (34–46) | <0.0001 |

| Per cent hypoalbuminaemia | 60.0 | 4.9 | < 0.0001 |

| Per cent hyperalbuminaemia | 0.6 | 2.0 | 0.0063 |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 39 (7–171) | 96 (19–154) | <0.0001 |

| Per cent < 60 | 62.3 | 18.2 | < 0.0001 |

| Phosphate (mmol/L) | 1.18 (0.48–2.68) | 1.00 (0.64–1.54) | <0.0001 |

Continuous variables are given as medians (2.5–97.5 percentile).

eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate.

Albumin coefficients

The results of simple and multiple linear regression analyses are given in table 2. The unadjusted regression coefficients of albumin were significantly different below and above 30 g/L for patients with eGFR ≥60 mL/min/1.73 m2 (p<0.001). With multiple linear regression, patients with eGFR ≥60 mL/min/1.73 m2 and albumin <30 g/L had a 32.5% higher adjusted regression coefficient than patients with eGFR ≥60 mL/min/1.73 m2 and albumin ≥30 g/L.

Table 2.

Results of simple linear regression of total calcium against albumin, and multiple linear regression of total calcium against albumin and other relevant variables

| Subpopulation | Simple linear regression | Multiple linear regression | |

| Unadjusted albumin coefficient (95% CI) | Significant variables | Adjusted albumin coefficient (95% CI) | |

| All with eGFR ≥60 mL/min/1.73 m2, n=5013 | 0.0167 (0.0158 to 0.0176) | Albumin, free calcium, gender, age, eGFR, phosphate | 0.0126 (0.0121 to 0.0132) |

| eGFR ≥60 mL/min/1.73 m2 and albumin<30 g/L, n=103 | 0.0282 (0.0158 to 0.0406) | Albumin, free calcium | 0.0159 (0.0112 to 0.0206) |

| eGFR ≥60 mL/min/1.73 m2 and albumin≥30 g/L, n=4910 | 0.0154 (0.0142 to 0.0166) | Albumin, free calcium, gender, age, eGFR, phosphate, hospitalisation status | 0.0120 (0.0113 to 0.0128) |

| All with eGFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2, n=1536 | 0.0160 (0.0140 to 0.0181) | Albumin, free calcium, age, eGFR, phosphate | 0.0123 (0.0113 to 0.0133) |

Only the adjusted albumin coefficients were used to construct the local group-specific formulas for albumin-adjusted calcium.

eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate.

Diagnostic accuracy

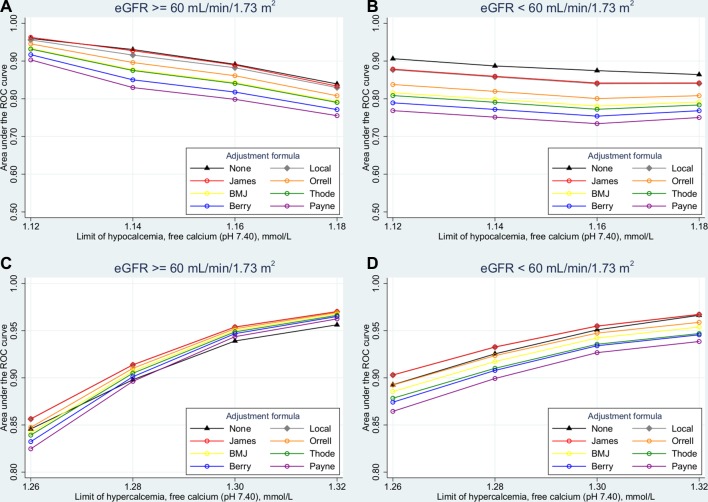

The diagnostic accuracy of unadjusted calcium and albumin-adjusted calcium values calculated from the locally constructed formulas and formulas taken from literature is shown in figure 1 (ROC curve analysis) and table 3 (Harrell’s c index). In patients with eGFR ≥60 mL/min/1.73 m2, unadjusted calcium was not inferior to any albumin-adjustment formulas in diagnosing hypocalcaemia (figure 1A). In patients with eGFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2, unadjusted calcium outperformed all albumin-adjustment formulas in diagnosing hypocalcaemia, independent of the definitions of hypocalcaemia used in this study (p<0.001 at all definitions when compared with the formula of James et al20 (figure 1B)). In diagnosing hypercalcaemia, unadjusted calcium performed somewhat worse than some albumin-adjustment formulas (figure 1C,D). When free calcium was treated as a continuous gold standard, using Harrell’s c Index, unadjusted calcium performed significantly better than the best calcium-adjustment formula (the formula of James et al,20 p=0.004) and the locally constructed formulas (p=0.002) in patients with eGFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2. In patients with eGFR ≥60 mL/min/1.73 m2, unadjusted calcium was not inferior to those formulas (p=0.43 vs the James et al formula and p=0.97 vs the locally constructed formulas) and significantly better than the other formulas (p<0.001 in all cases).

Figure 1.

Accuracy in the diagnosis of (A) and (B) hypocalcaemia and (C) and (D) hypercalcaemia in patients with estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) (A) and (C) above or (B) and (D) below 60 mL/min/1.73 m2, given as the area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve for various albumin-adjustment formulas and for unadjusted calcium.

Table 3.

Agreement between total calcium and free calcium as measured by Harrell’s c Index (95% CI) in patients with estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) above or below normal 60 mL/min/1.73 m2

| Adjustment formula | eGFR≥60 mL/min/1.73 m2 (n=5013) | eGFR<60 mL/min/1.73 m2 (n=1536) |

| None | 0.749 (0.741–0.758) | 0.801 (0.788–0.813) |

| Local* | 0.749 (0.741–0.758) | 0.790 (0.776–0.803) |

| James et al20 | 0.751 (0.743–0.759) | 0.791 (0.777–0.804) |

| Orrell4 | 0.736 (0.728–0.745) | 0.766 (0.751–0.781) |

| BMJ6 | 0.728 (0.719–0.737) | 0.753 (0.738–0.769) |

| Thode 19 | 0.726 (0.717–0.735) | 0.747 (0.731–0.763) |

| Berry et al7 | 0.716 (0.707–0.725) | 0.736 (0.720–0.752) |

| Payne et al5 | 0.707 (0.698–0.716) | 0.723 (0.707–0.740) |

*The local adjustment formulas were constructed using three subgroup-specific albumin coefficients; see Material and methods.

Discussion

In this work, we estimated regression coefficients for albumin that reflected how much total calcium changes per unit change in albumin, adjusted for other relevant variables. To our knowledge, that has not been done before. Although theoretically sound and lower albumin coefficients were found (table 2), this procedure was nevertheless a disappointment, as the locally constructed formulas performed worse than unadjusted calcium in the subgroup of patients with eGFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2, and no better than unadjusted calcium in the subgroup with eGFR ≥60 mL/min/1.73 m2 (table 3). This was even more disappointing, as the local formulas were derived from and tested in the same dataset, so one would expect that their performance were positively biased. In fact, our locally constructed formulas performed very much like the formula of James et al.20 Given that our regression coefficients for most patients are the same as or close to the value of 0.012 in the James et al formula, equal performance is no surprise. It is more remarkable that we estimated about the same regression coefficients as James et al when the populations, albumin methods and regression methods were different.20 However, James et al did not adjust for other relevant variables, so only the unadjusted albumin coefficients can be directly compared. Those coefficients were higher in our population than in the population of James et al (table 2), probably due to different albumin methods (bromocresol green vs bromocresol purple) as well different populations. Our finding of a statistically significantly lower adjusted regression coefficient in patients with albumin ≥30 g/L compared with those with albumin <30 g/L in the group with eGFR ≥60 mL/min/1.73 m2 (table 2) may not be clinically significant, as our formulas did not outperform the formula of James et al who used the same coefficient in all patient groups.

The diagnostic accuracy of albumin-adjustment formulas has been questioned previously. Almost 40 years ago, Ladenson et al9 compared 13 different adjustment formulas in a population of 375 hospitalised patients and 53 controls, among them the albumin-adjustment formulas of Orrell,4 Berry et al7 and Payne et al,5 and found that none correlated better with free calcium than unadjusted calcium. We have found no evidence in the literature supporting that albumin-adjusted calcium is superior to unadjusted calcium in this aspect. Our study includes a relatively large group of both hospitalised and ambulant patients from a large regional hospital, representing an unselected population with a broad spectrum of disease. Compared with Ladenson et al,9 our findings are strengthened by a much larger study population. In addition, we have evaluated the diagnostic accuracy using free calcium both as a continuous gold standard (with Harrell’s c index) and as a dichotomous one (with ROC curve analysis).

The various adjustment formulas use different normal values of albumin. We normalised to 40 g/L, as did Payne et al,5 while Orrell4 used 34 g/L and Berry et al746 g/L. The choice of normal albumin value does not influence the diagnostic accuracy, because adjusted calcium=calcium+coefficient×(normal albumin−albumin)=calcium+coefficient×normal albumin−coefficient×albumin= calcium+constant+coefficient×albumin. Adding a constant to the value of a diagnostic marker does not change its diagnostic accuracy. The choice of normal albumin value does, however, influence the optimal cut-off value of albumin-adjusted calcium. Finding the optimal cut-off value could be done by ROC analysis if the prevalence of the clinical condition and the consequences of false and true positive and negative results are known,22 but such an analysis was beyond the scope of this work.

As judged by ROC curve analysis, some of the other formulas taken from literature performed rather poorly in the diagnosis of hypocalcaemia in all patients (figure 1A,B), and in the diagnosis of hypercalcaemia in patients with eGFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2 (figure 1D). In the diagnosis of hypercalcaemia in patients with eGFR ≥60 mL/min/1.73 m2, they all performed rather well (figure 1C). As judged by Harrell’s c index, unadjusted calcium was the most accurate diagnostic test in patients with eGFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2, and not inferior to any formula in patients with eGFR ≥60 mL/min/1.73 m2. The commonly used BMJ formula (Calciumadj(mmol/L)=total calcium(mmol/L)+0.02×(40 − albumin (g/L), suggested in BMJ in 19776), was significantly less accurate than unadjusted calcium in both eGFR groups. All calcium measures performed better in patients with eGFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2 than in those with eGFR ≥60 mL/min/1.73 m2. The ROC curve analyses partly corroborated this; however, in the diagnosis of hypercalcaemia in patients with eGFR ≥60 mL/min/1.73 m2, some albumin-adjustment formulas performed slightly better than unadjusted calcium. Furthermore, the calcium measures were no better in patients with eGFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2 than in patients with eGFR ≥60 mL/min/1.73 m2. We have no explanation of this divergence between the two methods of evaluating diagnostic accuracy, other than the information loss from dichotomisation of the continuous gold standard in the ROC curve analyses. This loss of information was partly taken into consideration, as we used four different definitions of hypocalcaemia and hypercalcaemia in the ROC curves analyses. We extended both definitions downwards from our reference limits of 1.18 and 1.32 mmol/L, as more recent work indicates that our reference limits may be somewhat high.23 As expected, the area under the ROC curves increased when hypocalcaemia and hypercalcaemia were defined more stringently, that is, when the diagnoses represented more pathological cases.

Limitations of the study

Some limitations of our study should be mentioned. First, the use of pH-adjusted free calcium as a gold standard could be questioned. Although the actual concentration of free calcium in correctly sampled blood specimens should be the most relevant measure of calcium status, Thode et al found that pH-adjusted free calcium was as useful as the actual (unadjusted) free calcium in 183 patients with various calcium disorders.24 Anyway, pH-adjusted free calcium was the only measure we could use, as the actual (unadjusted) free calcium was recorded in only 26 patients. Second, as no diagnostic information was available to us we do not know whether our findings are applicable to every clinical condition. However, the renal function could be estimated. The fraction of patients with an eGFR less than 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 was very different in ambulant and hospitalised patients (18% vs 62%), indicating that reduced renal function was more prevalent in hospitalised patients and/or that free calcium was more likely to be requested in hospitalised patients with reduced renal function. The relatively large number of patients with reduced renal function in the study population may be an advantage, as we know from this and other studies16 25 26 that albumin-adjustment formulas perform differently in patients with and without renal failure. Third, we did not collect data on sodium, magnesium and parathyroid hormone. Such data could have been included for a better estimate of the albumin coefficient. However, the inclusion of more variables in the same blood draw would significantly have reduced the sample size. We wanted to keep the samples size as large as possible to get a reliable estimate of the albumin coefficient.

Conclusion

We found that the diagnostic accuracy of unadjusted calcium in general is superior to that of albumin-adjusted total calcium based on formulas from literature, and even to that of locally constructed adjustment formulas especially adapted to our dataset. Despite that many have questioned the diagnostic accuracy of albumin-adjustment formulas previously, they continue to be used in general clinical practice. We believe that the clinician should order measurement of free calcium instead of albumin-adjusted calcium in patients where total calcium is not to be trusted, as the analysis of free calcium is now widely available.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: Both authors contributed to the acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data for the work, drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content. AÅ was the main contributor in the conception and design of the work. IAL is the guarantor.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Ethics approval: The study was carried out in full accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. According to the Norwegian Health Research Act, this type of project which uses anonymous information from local health registers, is not required to be evaluated by the Norwegian Regional Ethical Committee.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The full dataset is available upon request from the corresponding author (ingrid.alsos.lian@gmail.com).

References

- 1.Aishah AB, Foo YN. A retrospective study of serum calcium levels in a hospital population in Malaysia. Med J Malaysia 1995;50:246–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hästbacka J, Pettilä V. Prevalence and predictive value of ionized hypocalcemia among critically ill patients. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2003;47:1264–9. 10.1046/j.1399-6576.2003.00236.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baird GS. Ionized calcium. Clin Chim Acta 2011;412:696–701. 10.1016/j.cca.2011.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Orrell DH. Albumin as an aid to the interpretation of serum calcium. Clin Chim Acta 1971;35:483–9. 10.1016/0009-8981(71)90224-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Payne RB, Little AJ, Williams RB, et al. Interpretation of serum calcium in patients with abnormal serum proteins. Br Med J 1973;4:643–6. 10.1136/bmj.4.5893.643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anon. Correcting the calcium. Br Med J 1977;1:598. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berry EM, Gupta MM, Turner SJ, et al. Variation in plasma calcium with induced changes in plasma specific gravity, total protein, and albumin. Br Med J 1973;4:640–3. 10.1136/bmj.4.5893.640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hannan FM, Thakker RV. Investigating hypocalcaemia. BMJ 2013;346:f2213 10.1136/bmj.f2213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ladenson JH, Lewis JW, Boyd JC. Failure of total calcium corrected for protein, albumin, and pH to correctly assess free calcium status. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1978;46:986–93. 10.1210/jcem-46-6-986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clase CM, Norman GL, Beecroft ML, et al. Albumin-corrected calcium and ionized calcium in stable haemodialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2000;15:1841–6. 10.1093/ndt/15.11.1841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Labriola L, Wallemacq P, Gulbis B, et al. The impact of the assay for measuring albumin on corrected (’adjusted') calcium concentrations. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2009;24:1834–8. 10.1093/ndt/gfn747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rustad P, Felding P, Franzson L, et al. The nordic reference interval project 2000: recommended reference intervals for 25 common biochemical properties. Scand J Clin Lab Invest 2004;64:271–84. 10.1080/00365510410006324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bruunhuus I, Magdal U. Kompendium 2000 - Kompendium i Laboratoriemedicin online [Edited 2008]. http://www.dskb.dk/Clubs/CommonDrive/Components/GetWWWFile.aspx?fileID=45556

- 14.Mårtensson A, Rustad P, Lund H, et al. Creatininium reference intervals for corrected methods. Scand J Clin Lab Invest 2004;64:439–41. 10.1080/00365510410002832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ceriotti F, Boyd JC, Klein G, et al. Reference intervals for serum creatinine concentrations: assessment of available data for global application. Clin Chem 2008;54:559–66. 10.1373/clinchem.2007.099648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jain A, Bhayana S, Vlasschaert M, et al. A formula to predict corrected calcium in haemodialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2008;23:2884–8. 10.1093/ndt/gfn186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pottel H, Hoste L, Dubourg L, et al. An estimated glomerular filtration rate equation for the full age spectrum. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2016;31:798–806. 10.1093/ndt/gfv454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Coresh J, Selvin E, Stevens LA, et al. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease in the United States. JAMA 2007;298:2038–47. 10.1001/jama.298.17.2038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thode J, Juul-Jørgensen B, Bhatia HM, et al. Comparison of serum total calcium, albumin-corrected total calcium, and ionized calcium in 1213 patients with suspected calcium disorders. Scand J Clin Lab Invest 1989;49:217–23. 10.3109/00365518909089086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.James MT, Zhang J, Lyon AW, et al. Derivation and internal validation of an equation for albumin-adjusted calcium. BMC Clin Pathol 2008;8:12 10.1186/1472-6890-8-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Newson RB. Interpretation of Somers' D under four simple models [Edited 2014]. http://www.imperial.ac.uk/nhli/r.newson/miscdocs/intsomd1.pdf

- 22.Metz CE. Basic principles of ROC analysis. Semin Nucl Med 1978;8:283–98. 10.1016/S0001-2998(78)80014-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Klæstrup E, Trydal T, Pedersen JF, et al. Reference intervals and age and gender dependency for arterial blood gases and electrolytes in adults. Clin Chem Lab Med 2011;49:1495–500. 10.1515/CCLM.2011.603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thode J, Holmegaard SN, Transbøl I, et al. Adjusted ionized calcium (at pH 7.4) and actual ionized calcium (at actual pH) in capillary blood compared for clinical evaluation of patients with disorders of calcium metabolism. Clin Chem 1990;36:541–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gauci C, Moranne O, Fouqueray B, et al. Pitfalls of measuring total blood calcium in patients with CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol 2008;19:1592–8. 10.1681/ASN.2007040449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morton AR, Garland JS, Holden RM. Is the calcium correct? Measuring serum calcium in dialysis patients. Semin Dial 2010;23:283–9. 10.1111/j.1525-139X.2010.00735.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.