Abstract

Objective

Cigarette smoke-induced oxidative stress plays an important role in the pathogenesis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Dietary antioxidants are thought to prevent smoke-induced oxidative damage. The aim of this study was to investigate associations between lung function and the consumption of antioxidant vitamins in Korean adults.

Methods

In total, 21 148 participants from the Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (2007–2014) were divided into four groups based on smoking history and gender. Multivariate regression models were used to evaluate associations between lung function and intake of dietary antioxidants.

Results

Subjects in the highest intake quintile (Q5) of vitamin A, carotene and vitamin C intake had mean forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) measurements that were 30 mL, 32 mL and 36 mL higher than those of individuals in the lowest intake quintile (Q1), respectively (p for trend; p=0.008, p=0.010 and p<0.001, respectively). The risks of COPD for male smokers in Q1 increased 7.60-fold (95% CI 5.92 to 9.76), 7.16-fold (95% CI 5.58 to 9.19) and 7.79-fold (95% CI 6.12 to 9.92), for vitamin A, carotene and vitamin C, respectively, compared with those of female non-smokers in Q5. Among patients with COPD, men who smoked >20 pack-years had mean FEV1 measurements that were 192 mL, 149 mL and 177 mL higher than those of patients in Q1 (p for trend; p=0.018, p=0.024 and p=0.043, for vitamin A, carotene and vitamin C, respectively).

Conclusions

These findings indicate that the influence of antioxidant vitamins on lung function depends on gender and smoking status in the Korean COPD population.

Keywords: lung function, gender, smoking, antioxidant vitamins

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study revealed that the influence of antioxidant vitamins on lung function depends on gender and smoking status in Korean patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

This is a cross-sectional study with a large sample size collected from a national health survey.

Main limitations include a possible recall bias and no further verification of nutritional intake.

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) causes morbidity and mortality.1 Smoking is a primary risk factor for COPD; however, other factors also contribute as only 10%–20% of smokers develop airflow limitations.2

Dietary antioxidants protect against oxidative stress caused by smoking,3 and multiple studies have revealed associations between the intake of antioxidant vitamins or fibres and respiratory diseases.4–8 However, evidence supporting the benefits of vitamin supplement therapy is lacking.9 10

Because micronutrient status is affected by dietary intake and metabolic turnover, which are regulated by oxidative stress, the benefits of antioxidant vitamins may vary by gender and smoking status. Multiple studies have shown that different antioxidants exhibit different effects based on smoking status. Morabia et al reported an association between airway obstruction and vitamin A intake in smokers compared with former smokers, whereas Hu et al reported that carotene was less strongly associated with FEV1 in smokers compared with former smokers and non-smokers.11 12

This study used Korean National Health and Nutritional Examination Survey (KNHANES) data to investigate whether dietary antioxidant vitamins were independently associated with pulmonary function and COPD in the Korean population. This study also evaluated whether the effects of antioxidant vitamins on pulmonary function differed based on gender or smoking status.

Patients and methods

Study population

Participants were sampled from KNHANES (2007–2014) IV–VI, a nationwide survey designed to be representative of the population that is used to establish health policies. KNHANES contains a massive database with information about demographic characteristics, comorbidities, lung function, nutritional status and health (https://knhanes.cdc.go.kr/knhanes).

A two-stage stratified systemic sampling method was use to select 65 973 individuals to survey between February 2007 and December 2014. Of the chosen individuals, 34 278 participants over 40 years of age responded to questionnaires regarding diet and smoking history and underwent a medical examination. After excluding subjects who omitted lung function or nutrition data, we analysed data from 21 148 (8804 men and 12 344 women) in this study. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Korean Centres for Disease Control and Prevention. All participants provided informed written consent.

Protocol

KNHANES collects survey data through health questionnaire surveys, screening surveys and nutrition surveys. Health questionnaires were divided into household survey, health interview survey and health behaviour survey. The health interview survey examined the use of medical services, activity limitations, education and economic activities and physical activity by interview method. The health behaviour survey examined smoking status, drinking, mental health and safety consciousness by self-filling method. The screening consisted of physical measurement, blood pressure and pulse measurement, blood and urine test, oral examination, pulmonary function test, visual and refractive examination, colour vision test, hearing test and muscle strength test. Nutrition surveys consisted of dietary behaviours, dietary supplements, nutritional knowledge and the contents of food intake (24-hour recall method) a day before the survey.

Spirometry and airflow obstruction definitions

The pulmonary function test was performed using dry-rolling seal volume spirometers (Model 2130; Sensor Medics, Yorba Linda, California, USA) and standardised according to the American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society criteria.13 Qualified technicians and principal investigators assessed the spirometry data for acceptability and reproducibility. The predictive equations for the forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) and the forced vital capacity (FVC) were derived from survey data on non-smokers who had normal chest X-rays and no history of respiratory diseases.14 COPD was defined as an FEV1/FVC<70 %.15

Dietary assessments

Food intake data were obtained using the 24-hour recall method, in which participants were asked to report the foods and amounts thereof consumed during the previous 24 hours. Total energy (kJ/d (kcal/d)) and total intake of antioxidant vitamins were calculated using the Korean Food Composition Table16 as the reference. Antioxidant vitamin consumption was adjusted for total energy intake.

Potential confounders

Data regarding demographic information, education level, household income, smoking status, smoking amount, alcohol intake, place of residence, body mass index (BMI) and comorbid diseases were obtained. Educational level was categorised as elementary school or lower, completion of middle school, completion of high school and college or higher. Household income was divided by quartile. Place of residence was divided to rural and urban.

Smokers were subjects who smoked more than 100 cigarettes in their lifetime.17 Participants were categorised in terms of smoking status as follows: smoker, ex-smoker or never smoked. Those who answered in the negative to the question ‘Do you currently smoke?’ were defined as ex-smokers.

The smoking amount was determined in pack-years, which was calculated by multiplying the duration of smoking (years) by the number of packs of cigarettes smoked. Comorbid diseases included hypertension, stroke, cardiovascular disease, arthritis, tuberculosis, asthma, diabetes mellitus, thyroid disorders, renal failure, liver disease and malignancy.

Statistical analysis

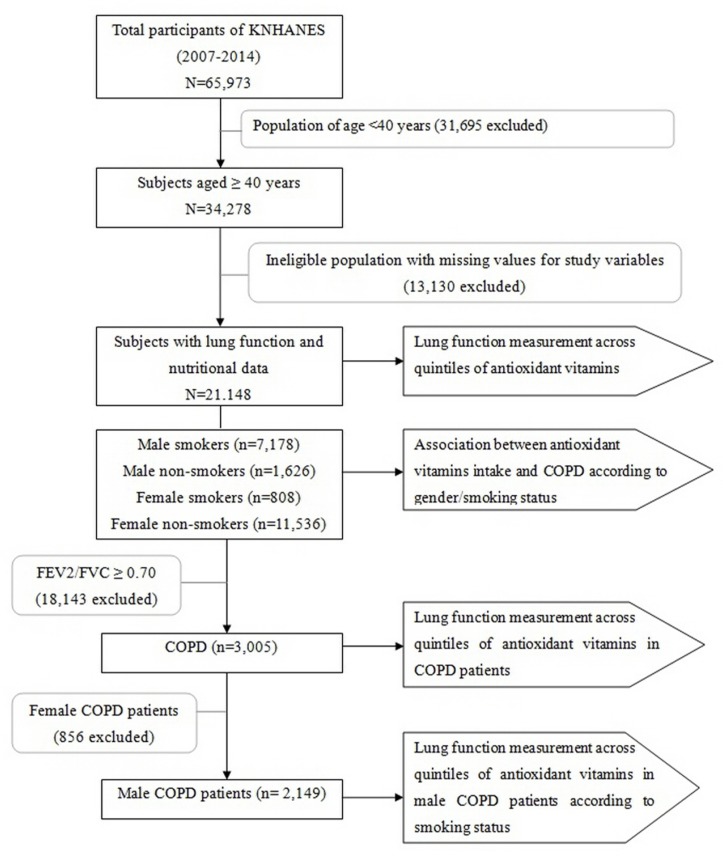

A total of 21 148 subjects participated in this study (figure 1). The relationship between antioxidant vitamin intake and lung function was analysed using multiple linear regression analyses. We analysed the energy-adjusted antioxidant vitamin intake by quintiles. The adjustment factors were age, sex, BMI, educational level, household income, total energy intake, place of residence, number of comorbid diseases, smoking history, alcohol intake and pack-years.4 11 18 Assessments of linear trends across increasing antioxidant vitamin quintiles were also performed.

Figure 1.

The study population framework. COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; FVC, forced vital capacity; FEV2, forced expiratory volume in 2 s; KNHANES, Korean National Health and Nutritional Examination Survey.

We estimated the ORs of COPD using multivariate logistic regression analyses of quintiles after adjusting for confounding factors. Participants were divided into four groups based on gender and smoking status (male smokers, male non-smokers, female smokers, female non-smokers) to determine whether the relationship between COPD risk and antioxidant vitamin intake is related to gender and smoking status. For combined analyses between the effects of antioxidant vitamin intake, gender and smoking status on the risk of COPD, interaction tests were performed. Patients with COPD and male patients with COPD were analysed separately. We attempted to determine whether the association of antioxidant vitamins and lung function varies with gender and smoking status in patients with COPD. Multiple linear regression analyses were performed after categorising patients with COPD by smoking status and amount.

Statistical analyses were performed using PASW Statistics V.20 (SPSS) and SAS V.9.4 (SAS Institute) software. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

The baseline characteristics of the 21 148 participants are shown in table 1. All subjects were classified into four groups based on smoking history and gender. Of the 7986 smokers, 7178 were male (mean age, 57.8±11.0 years) and 808 were female (mean age, 57.4±12.5 years). Of the 13 162 individuals who had never smoked, 1626 were male (mean age, 57.9±11.3 years) and 11 536 were female (mean age, 57.1±10.8 years). Among all subjects, 3005 were diagnosed with COPD. The prevalence of COPD was highest in male smokers (26.4%) and lowest in female non-smokers (6.4%).

Table 1.

Study population characteristics

| Total | Male smokers | Male non-smokers | Female smokers | Female non-smokers | P values | |

| (n=21 148) | (n=7178) | (n=1.626) | (n=808) | (n=11 536) | ||

| Age* | 57.4 (10.9) | 57.8 (11.0) | 57.9 (11.3) | 57.4 (12.5) | 57.1 (10.8) | <0.001 |

| 40–49 | 6048 (28.6) | 1998 (27.8) | 464 (28.5) | 273 (33.8) | 3313 (28.7) | <0.001 |

| 50–59 | 6131 (29.0) | 1981 (27.6) | 431 (26.5) | 199 (24.6) | 3520 (30.5) | |

| 60–69 | 5387 (25.5) | 1913 (26.7) | 430 (26.4) | 158 (19.6) | 2866 (25.0) | |

| 70– | 3582 (16.9) | 1286 (17.9) | 301 (18.5) | 178 (22.0) | 1817 (15.8) | |

| BMI* | 24.2 (3.0) | 24.2 (2.8) | 24.3 (2.8) | 23.8 (3.6) | 24.2 (3.2) | 0.007 |

| Education | <0.001 | |||||

| Elementary | 7229 (34.2) | 1763 (24.6) | 321 (19.7) | 381 (47.2) | 4764 (41.3) | |

| Middle school | 3315 (15.7) | 1216 (16.9) | 267 (16.4) | 112 (13.9) | 1720 (14.9) | |

| High school | 6427 (30.4) | 2366 (33.0) | 458 (28.2) | 228 (28.2) | 3375 (29.3) | |

| More than college | 4169 (19.7) | 1831 (25.5) | 580 (35.7) | 87 (10.8) | 1671 (14.5) | |

| Household income | <0.001 | |||||

| First quartile | 4763 (22.5) | 1440 (20.1) | 289 (17.8) | 315 (39.0) | 2719 (23.6) | |

| Second quartile | 5427 (25.7) | 1874 (26.1) | 391 (24.1) | 223 (27.6) | 2939 (25.5) | |

| Third quartile | 5162 (24.4) | 1869 (26.1) | 414 (25.5) | 145 (17.9) | 2734 (23.7) | |

| Fourth quartile | 5780 (27.3) | 1988 (27.7) | 530 (32.6) | 125 (15.5) | 3137 (27.2) | |

| Comorbidity* | 0.9 (1.1) | 0.9 (1.0) | 0.8 (0.9) | 1.0 (1.2) | 1.0 (1.1) | <0.001 |

| Pack-years* | 4.7 (13.6) | 13.3 (20.3) | 0.2 (2.2) | 3.3 (11.9) | 0.0 (0.0) | <0.001 |

| Alcohol | 17 554 (83.0) | 6877 (95.8) | 1399 (86.0) | 714 (88.4) | 8564 (74.2) | <0.001 |

| Energy intake (kcal/day)* | 1901.5 (797.8) | 2266.5 (869.7) | 2212.6 (855.9) | 1538.2 (653.4) | 1656.0 (630.0) | <0.001 |

| Vitamin A (μg RE/day)* | 822.5 (1118.5) | 881.9 (1067.5) | 925.5 (1095.2) | 600.3 (644.2) | 786.6 (1173.9) | <0.001 |

| Carotene (μg/day)* | 4337.3 (6206.0) | 4596.2 (5557.8) | 4803.8 (5506.6) | 3143.5 (3682.6) | 4194.1 (6780.6) | <0.001 |

| Vitamin C (mg/day)* | 111.9 (107.6) | 111.8 (97.9) | 128.8 (107.1) | 84.8 (96.9) | 111.5 (113.5) | <0.001 |

| FEV1 (mL)* | 2.60 (0.67) | 3.02 (0.68) | 3.09 (0.66) | 2.23 (0.56) | 2.30 (0.46) | <0.001 |

| FVC (mL)* | 3.38 (0.84) | 4.07 (0.72) | 4.04 (0.73) | 2.88 (0.62) | 2.89 (0.51) | <0.001 |

| FEV1/FVC (%)* | 77.3 (7.9) | 73.9 (9.1) | 76.6 (7.9) | 77.2 (8.0) | 79.5 (6.1) | <0.001 |

| COPD | 3005 (14.2) | 1893 (26.4) | 256 (15.7) | 119 (14.7) | 737 (6.4) | <0.001 |

*Numbers represent mean percentages (SD).

BMI, body mass index; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; FVC, forced vital capacity; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s; RE, retinol equivalent.

The four groups differed regarding age, BMI, educational level, household income and alcohol usage (p<0.001). Energy intake was significantly higher in men than women (men, 2256.5 kcal; women, 1648.3 kcal; p<0.001). The levels of vitamin A, carotene and vitamin C were highest in the male non-smoker group and lowest in the female smoker group. Korean male non-smokers are predisposed to COPD compared with female non-smokers (incidence rate of 15.7% vs 6.4%). Age and the percentage of alcohol intake were higher in Korean male non-smokers than female non-smokers.

Table 2 showed the association between lung function (FEV1, FVC) and dietary antioxidant vitamin levels. Participants in the highest quintile (Q5) of vitamin A intake had 30 mL higher FEV1 (p for trend across quintiles=0.008) and 33 mL higher FVC (p for trend across quintiles=0.007) compared with participants in the lowest quintile (Q1). Participants in Q5 for carotene intake had 32 mL higher FEV1 (p for trend across quintiles=0.010) and 36 mL higher FVC (p for trend across quintiles=0.005) measurements compared with participants in Q1. Participants in Q5 of vitamin C intake had 36 mL higher FEV1 (p for trend across quintiles<0.001) and 35 mL higher FVC (p for trend across quintiles=0.014) measurements compared with participants in Q1. A statistically significant dose–response relationship was observed (all, p for trend across quintiles<0.005), but participants in Q3 of vitamin A and carotene had comparable lung function to those in Q5.

Table 2.

Mean values of adjusted lung function measurements across quintiles of vitamin A, carotene and vitamin C intake

| Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Difference between Q5 and Q1 (95% CI) | P values for trend | |

| Vitamin A | |||||||

| Mean intake (μg RE) | 151.2 | 353.6 | 573.1 | 893.9 | 2140.8 | ||

| FEV1 (mL) | 2379 | 2389 | 2410 | 2397 | 2409 | 30 (10 to 50) | 0.008 |

| FVC (mL) | 3119 | 3136 | 3158 | 3148 | 3152 | 33 (10 to 57) | 0.007 |

| Predicted FEV1 (%) | 91.37 | 91.44 | 91.91 | 91.45 | 91.94 | 0.57 (-0.08 to 1.22) | 0.185 |

| Predicted FVC (%) | 90.93 | 91.06 | 91.45 | 91.22 | 91.48 | 0.55 (0.00 to 1.10) | 0.195 |

| Carotene | |||||||

| Mean intake (μg) | 691.1 | 1747.4 | 2938.9 | 4736.1 | 11 574.1 | ||

| FEV1 (mL) | 2347 | 2363 | 2376 | 2370 | 2379 | 32 (12 to 52) | 0.010 |

| FVC (mL) | 3088 | 3117 | 3127 | 3119 | 3124 | 36 (13.59) | 0.005 |

| Predicted FEV1 (%) | 91.55 | 92.03 | 92.26 | 91.85 | 92.31 | 0.76 (0.12 to 1.39) | 0.096 |

| Predicted FVC (%) | 91.02 | 91.68 | 91.78 | 91.41 | 91.82 | 0.80 (0.26 to 1.33) | 0.015 |

| Vitamin C | |||||||

| Mean intake (mg) | 24.2 | 53.6 | 84.2 | 128.8 | 268.9 | ||

| FEV1 (mL) | 2411 | 2423 | 2436 | 2441 | 2453 | 36 (16.56) | <0.001 |

| FVC (mL) | 3117 | 3122 | 3132 | 3140 | 3154 | 35 (12.58) | 0.014 |

| Predicted FEV1 (%) | 91.3 | 91.5 | 91.9 | 91.99 | 92.21 | 0.91 (0.27 to 1.55) | 0.050 |

| Predicted FVC (%) | 91.29 | 91.33 | 91.58 | 91.77 | 92.0 | 0.71 (0.17 to 1.26) | 0.118 |

Data were adjusted for age, sex, body mass index, energy intake, number of comorbid diseases, alcohol consumption, place of residence smoking history, pack-years (smoking amount), household income and education level. P values were determined using tests for linear trends across increasing quintiles (means) of antioxidant vitamin intake.

FVC, forced vital capacity; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s; RE, retinol equivalent; Q1, lowest quintile; Q5, highest quintile.

The effects of gender, smoking and dietary antioxidant vitamins on the risk of COPD are summarised in table 3. The risk of COPD for male smokers in Q1 for vitamin A, carotene and vitamin C intake increased by 7.60-fold (95% CI 5.92 to 9.76), 7.16-fold (95% CI 5.58 to 9.19) and 7.79-fold (95% CI 6.12 to 9.92), respectively, which was greater than that observed for female non-smokers in Q5 for antioxidant vitamin intake. Interestingly, the risk of COPD for male non-smokers in Q5 for vitamin A, carotene and vitamin C intake increased by 3.26-fold (95% CI 2.24 to 4.75). 3.35-fold (95% CI 2.31 to 4.86) and 3.28-fold (95% CI 2.27 to 4.73), respectively, compared with female non-smokers in Q5 for antioxidant vitamin intake. The risk of COPD for male non-smokers in Q1 for vitamin A, carotene and vitamin C intake increased by 2.80-fold (95% CI 1.90 to 4.12). 3.25-fold (95% CI 2.21 to 4.78) and 3.17-fold (95% CI 2.04 to 4.91), respectively, compared with female non-smokers in Q1 for antioxidant vitamin intake. These results suggest that men may have other causes of COPD as well as smoking, compared with women who took similar amounts of antioxidant vitamins.

Table 3.

Association between vitamin A, carotene and vitamin C intake and COPD according to gender and smoking status

| Intake | COPD | OR | P interaction | ||||

| Q5 | Q1 | Q5 | Q1 | Q5 | Q1 | ||

| Vitamin A | <0.001 | ||||||

| Female non-smokers | 2096 | 2564 | 105 | 242 | Ref | 1.16 (0.89, 1.49) | |

| Female smokers | 109 | 264 | 16 | 53 | 3.90 (2.12, 7.17) | 2.42 (1.63, 3.58) | |

| Male non-smokers | 394 | 225 | 53 | 47 | 3.26 (2.24, 4.75) | 3.15 (2.10, 4.72) | |

| Male smokers | 1630 | 1176 | 320 | 444 | 5.54 (4.28, 7.16)* | 7.60 (5.92, 9.76)* | |

| Carotene | |||||||

| Female non-smokers | 2118 | 2529 | 108 | 226 | Ref | 1.10 (0.85, 1.42) | <0.001 |

| Female smokers | 104 | 268 | 15 | 49 | 3.47 (1.86, 6.47) | 2.16 (1.45, 3.23) | |

| Male non-smokers | 397 | 243 | 55 | 50 | 3.35 (2.31, 4.86) | 3.24 (2.18, 4.82) | |

| Male smokers | 1610 | 1189 | 321 | 425 | 5.83 (4.51, 7.53)* | 7.16 (5.58, 9.19)* | |

| Vitamin C | |||||||

| Female non-smokers | 2303 | 2466 | 112 | 465 | Ref | 1.00 (0.77, 1.30) | <0.001 |

| Female smokers | 107 | 294 | 12 | 35 | 2.37 (1.20, 4.71) | 2.27 (1.55, 3.34) | |

| Male non-smokers | 401 | 191 | 55 | 55 | 3.28 (2.27, 4.73) | 3.24 (2.07, 5.06) | |

| Male smokers | 1419 | 1278 | 317 | 204 | 6.20 (4.82, 7.98)* | 7.79 (6.12, 9.92)* | |

OR was determined following adjustment for age, body mass index, energy intake, number of comorbid diseases, alcohol consumption, place of residence, household income and education level.

*The risk for COPD was significantly different between Q1 and Q5.

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; Q1, lowest quintile; Q5, highest quintile.

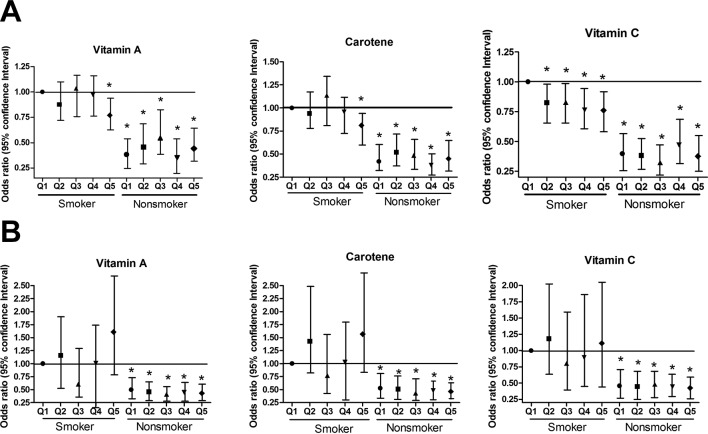

The interaction exists between the antioxidant vitamin intake and gender/smoking status on the risk of COPD (all p values<0.001). The effect of the antioxidant vitamin intake depends on the gender/smoking status. When assessing the risk of COPD following reduction of antioxidant intake from Q5 to Q1, only male smokers showed significant difference in risk of COPD, but other three groups did not. Figure 2 shows that the risk of COPD was influenced by dietary antioxidant vitamin levels in male smokers in detail. In male smokers, the risk of COPD in subjects in Q5 for antioxidant vitamins intake was significantly lower than that for subjects in Q1 (vitamin A, OR=0.77, 95% CI 0.63 to 0.94, p=0.009; carotene, OR=0.81, 95% CI 0.67 to 0.99, p=0.041; vitamin C, OR=0.74, 95% CI 0.61 to 0.91, p=0.004). The dose–dependent effect of vitamin C was observed between COPD risk and dietary antioxidant vitamin levels, but it was not for vitamin A and carotene. Although not significant, Q3 group of carotene had increased risk to develop COPD than Q1 group of carotene.

Figure 2.

OR for the association between antioxidant vitamin intake and COPD among (A) male and (B) female smokers and non-smokers. OR were adjusted for age, body mass index, energy intake, number of comorbid diseases, alcohol consumption, place of residence, household income and education level.

The prevalence of COPD did not increase significantly as the intake of dietary antioxidant vitamins increased in male non-smokers, female smokers or female non-smokers. No significant interaction between the effects of antioxidant vitamins on COPD and smoking status was observed. The correlation between the risk of COPD and antioxidant vitamin intake was stronger in male smokers who smoked less than 20 pack-years (not shown).

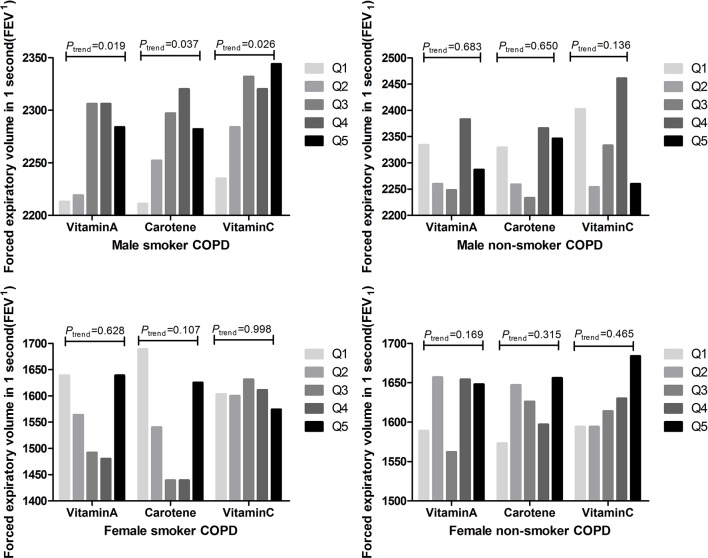

We investigated the association between dietary antioxidant vitamin intake and lung function after limiting the analyses to individuals with COPD. The changes in FEV1 were not statistically significant based on the levels of dietary antioxidant vitamins in subjects with COPD. Similar to the previous results, only male smokers in subjects with COPD, exhibited a beneficial association between dietary antioxidant vitamin intake and FEV1 (figure 3). Male smokers with COPD in Q5 for vitamin A intake had a 71 mL higher FEV1 (p for trend across quintiles=0.019) compared with those in Q1. Male smokers with COPD in Q5 of carotene and vitamin C intake had 71 mL higher FEV1 (p for trend across quintiles=0.037) and a 109 mL higher FEV1 (p for trend across quintiles=0.026), respectively, compared with individuals in Q1.

Figure 3.

Mean values of adjusted FEV1 measurements across quintiles of vitamin A, carotene and vitamin C intake (energy adjusted) in subjects with COPD. Adjusted for age, body mass index, energy intake, number of comorbid diseases, alcohol consumption, place of residence, household income and education level. P values were determined using tests for linear trends across increasing quintiles (means) of antioxidant vitamin intake. COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s.

Additional analyses were performed to determine if lung function was reduced by smoking amount or smoking status in male smoker patients with COPD. Male patients with COPD who had smoked ≥20 pack-years exhibited a beneficial association between dietary antioxidant vitamin intake and FEV1 (figure 4). Male patients with COPD in Q5 of vitamin A intake who had smoked ≥20 pack-years had a 192 mL higher FEV1 (p for trend across quintiles=0.018) compared with individuals in Q1. Patients with COPD in Q5 of carotene intake who had smoked ≥20 pack-years had a 149 mL higher FEV1 (p for trend across quintiles=0.024) compared with patients in Q1. Patients with COPD in Q5 of vitamin C intake who had smoked >20 pack-years had a 177 mL higher FEV1 (p for trend across quintiles=0.043) compared with patients in Q1.

Figure 4.

Mean values of adjusted FEV1 measurements across quintiles of vitamin A, carotene and vitamin C intake (energy adjusted) in male patients with COPD according to smoking status. Values were adjusted for age, BMI, energy intake, number of comorbid diseases, alcohol consumption, place of residence, household income and education level. P values were determined using tests for linear trends across increasing quintiles (median) of antioxidant vitamin intake. BMI, body mass index; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s.

Discussion

This study examined the association between the intake of antioxidant vitamins and lung functions in the Korean population. Previous studies showed that antioxidant vitamins, including vitamin C, were protective of the human lung,5 12 whereas high levels of vitamin A and carotene were also associated with increased lung functions in multiple studies.11 19–23 In a randomised controlled trial, Keranis et al reported that increasing the intake of antioxidants improved lung function.24

Cigarette smoking is the primary cause of COPD as it increases oxidative stress in the lungs and activates inflammatory responses.25 Notably, one inhalation from a cigarette generates more than 1015 free radicals and other oxidants.26

Antioxidants protect against the damage caused by smoking in multiple ways.3 For example, as it is water soluble, vitamin C scavenges free radicals in the cytoplasm. Koike et al reported that vitamin C diminished smoke-induced oxidative stress and corrected emphysematous lungs in vivo.27

Carotenoids quench singlet oxygen and inhibit lipid peroxidation.3 In an animal study, the respiratory epithelial of retinol-deficient animals had atrophied ciliated cells and modified lipid contents.28 The pathological features of the retinol-deficient animals were similar to those of human smokers.29

Smokers exhibit nicotine-induced reductions in intestinal absorption and elevated metabolic turnover.30 The metabolism or destruction of antioxidant vitamins increases in inflammatory environments,31–34 which suggests that smokers with COPD require larger amounts of antioxidant vitamins to achieve the same blood levels as non-smokers. A study by Sargeant and Jaeckel found that vitamin C may modify the adverse effects of smoking and the risk of COPD in the European population.35 Additionally, Shin et al reported that Korean smokers with adequate vitamin C intake had acceptable pulmonary functions36 and Park et al showed that dietary vitamin C provides protection against COPD.37 Additionally, Morabia et al identified that airway obstruction was reduced by vitamin A in smokers.11

One notable finding in the current study was that the effects of antioxidant vitamin intake on lung function were stronger among male smokers. Additionally, the association between the risk of COPD and antioxidant vitamin intake was clear for male but not female smokers. Male smokers with lower antioxidant vitamin intakes had increased ORs of COPD compared with female smokers. Although the dose-dependent effect on COPD risk was not obvious in vitamin A and carotene, contrary to vitamin C (figure 2), male smokers with Q5 intake showed a clearly reduced risk to develop COPD than male smokers with Q1 intake in all three antioxidant vitamins.

After limiting the analysis to subjects with COPD, a significant association between antioxidant vitamin intake and FEV1 was observed in male smokers but not in other groups. This finding was similar to that of Joshi et al, where changes in COPD risk and dietary vitamin C and vitamin E intake differed between men and women.38

It is not known how gender differences impact pulmonary functions based on antioxidant vitamin intake; however, animal studies have revealed gender differences in antioxidant vitamin requirements. Al-Rejaie et al reported gender-related differences in the protective roles of ascorbic acid against oxidative stress,39 whereas Jiao et al revealed gender differences in the regulation and expression of oxidative genes in mice.40

Studies detailing the effects of antioxidant vitamins on lung function in smokers and non-smokers are lacking.5 23 In the US population, Britton et al revealed that the relationship between vitamin C intake and FEV1 was stronger in ex-smokers than non-smokers or current smokers.5 Shahar et al reported a relationship between individuals in Q1 of vitamin A intake and airway obstruction among individuals who smoked >41 pack-years.23

Among male patients with COPD, those smoking ≥20 pack-years had improved lung functions as antioxidant vitamin intake increased. These results support that associations between antioxidants and lung function may differ according to smoking status in patients with COPD patients. However, it is unknown what causes such differences. One hypothesis is that the efficacy of antioxidant vitamins is proportional to the level of oxidant burden in COPD. Additional studies are required to determine whether the benefits of antioxidant vitamins depend on the smoking duration or dose in patients with COPD.

This study has several limitations that should be noted. As we used a cross-sectional design, the data cannot be used to answer questions regarding causation. Additionally, because data on nutritional intake were obtained by 24 hours recall, inaccurate responses may have been offered. This study used the prebronchodilator FEV1 for determining COPD; however, the definition of COPD is based on postbronchodilator FEV1.15 This study failed to obtain data regarding air pollution or occupational exposure and, therefore, could not associate these variables with lung function; however, the strength of this study is that these data represent the Korean population.

Conclusion

This study supports that antioxidant vitamins have beneficial effects on pulmonary function in the Korean population. The data indicate that there is a stronger association between antioxidant vitamin intake and the risk of COPD in male smokers. The beneficial effects of antioxidant vitamins in patients with COPD differed by gender and smoking status, and future investigations should determine the roles of dietary antioxidant vitamins in specific groups.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: JYH and YSK equally contributed to the conception and design of the research; YSK contributed to the design of the research; CYL contributed to the acquisition and analysis of the data; MGL and YSK contributed to the interpretation of the data and JYH drafted the manuscript. All authors critically revised the manuscript, agreed to be fully accountable for ensuring the integrity and accuracy of the work and read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This research was supported by the Bio and Medical Technology Development Program of the National Research Foundation (NRF) and funded by the Korean Government (MSIT) (NRF-2017M3A9E8033225). This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea Grant funded by the Korean Government (NRF 2017R1C1B5017879).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: Institutional Review Board of the Korean Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Viegi G, Pistelli F, Sherrill DL, et al. Definition, epidemiology and natural history of COPD. Eur Respir J 2007;30:993–1013. 10.1183/09031936.00082507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Capocaccia R, Verdecchia A, Micheli A, et al. Breast cancer incidence and prevalence estimated from survival and mortality. Cancer Causes Control 1990;1:23–9. 10.1007/BF00053180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Northrop-Clewes CA, Thurnham DI. Monitoring micronutrients in cigarette smokers. Clin Chim Acta 2007;377:14–38. 10.1016/j.cca.2006.08.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kan H, Stevens J, Heiss G, et al. Dietary fiber, lung function, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in the atherosclerosis risk in communities study. Am J Epidemiol 2008;167:570–8. 10.1093/aje/kwm343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Britton JR, Pavord ID, Richards KA, et al. Dietary antioxidant vitamin intake and lung function in the general population. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1995;151:1383–7. 10.1164/ajrccm.151.5.7735589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schünemann HJ, Freudenheim JL, Grant BJ. Epidemiologic evidence linking antioxidant vitamins to pulmonary function and airway obstruction. Epidemiol Rev 2001;23:248–67. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a000805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ford ES, Li C, Cunningham TJ, et al. Associations between antioxidants and all-cause mortality among US adults with obstructive lung function. Br J Nutr 2014;112:1662–73. 10.1017/S0007114514002669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rodríguez-Rodríguez E, Ortega RM, Andrés P, et al. Antioxidant status in a group of institutionalised elderly people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Br J Nutr 2016;115:1740–7. 10.1017/S0007114516000878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu TC, Huang YC, Hsu SY, et al. Vitamin E and vitamin C supplementation in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int J Vitam Nutr Res 2007;77:272–9. 10.1024/0300-9831.77.4.272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heart Protection Study Collaborative Group. MRC/BHF Heart Protection Study of antioxidant vitamin supplementation in 20 536 high-risk individuals: a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2002;360:23–33. 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09328-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morabia A, Sorenson A, Kumanyika SK, et al. Vitamin A, cigarette smoking, and airway obstruction. Am Rev Respir Dis 1989;140:1312–6. 10.1164/ajrccm/140.5.1312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hu G, Cassano PA. Antioxidant nutrients and pulmonary function: the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III). Am J Epidemiol 2000;151:975–81. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a010141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miller MR, Hankinson J, Brusasco V, et al. Standardisation of spirometry. Eur Respir J 2005;26:319–38. 10.1183/09031936.05.00034805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Choi JK, Paek D, Lee JO. Normal predictive values of spirometry in Korean population. Tuberc Respir Dis 2005;58:230–42. 10.4046/trd.2005.58.3.230 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rabe KF, Hurd S, Anzueto A, et al. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: GOLD executive summary. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2007;176:532–55. 10.1164/rccm.200703-456SO [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.RRD I. Food composition table. 7th ed Suwon, Korea: Rural Resource Development Institute, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yoo KH, Kim YS, Sheen SS, et al. Prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in Korea: the fourth Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2008. Respirology 2011;16:659–65. 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2011.01951.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hong JY, Kim SY, Chung KS, et al. Factors associated with the quality of life of Korean COPD patients as measured by the EQ-5D. Qual Life Res 2015;24:2549–58. 10.1007/s11136-015-0979-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kelly Y, Sacker A, Marmot M. Nutrition and respiratory health in adults: findings from the health survey for Scotland. Eur Respir J 2003;21:664–71. 10.1183/09031936.03.00055702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McKeever TM, Lewis SA, Smit HA, et al. A multivariate analysis of serum nutrient levels and lung function. Respir Res 2008;9:67 10.1186/1465-9921-9-67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miedema I, Feskens EJ, Heederik D, et al. Dietary determinants of long-term incidence of chronic nonspecific lung diseases. The Zutphen Study. Am J Epidemiol 1993;138:37–45. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McKeever TM, Scrivener S, Broadfield E, et al. Prospective study of diet and decline in lung function in a general population. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002;165:1299–303. 10.1164/rccm.2109030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shahar E, Folsom AR, Melnick SL, et al. Does dietary vitamin A protect against airway obstruction? The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study Investigators. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1994;150:978–82. 10.1164/ajrccm.150.4.7921473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Keranis E, Makris D, Rodopoulou P, et al. Impact of dietary shift to higher-antioxidant foods in COPD: a randomised trial. Eur Respir J 2010;36:774–80. 10.1183/09031936.00113809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alberg AJ, Chen JC, Zhao H, et al. Household exposure to passive cigarette smoking and serum micronutrient concentrations. Am J Clin Nutr 2000;72:1576–82. 10.1093/ajcn/72.6.1576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pryor WA, Stone K. Oxidants in cigarette smoke. Radicals, hydrogen peroxide, peroxynitrate, and peroxynitrite. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1993;686:12–27. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1993.tb39148.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Koike K, Ishigami A, Sato Y, et al. Vitamin C prevents cigarette smoke-induced pulmonary emphysema in mice and provides pulmonary restoration. Am J Respir Cell MolBiol 2014;50:347–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Iakovleva OA, Pentiuk AA G VI, et al. Effect of vitamin A deficiency on surfactants and enzymes of xenobiotic metabolism in the rat lung]. Vopr Pitan 1987;4:61–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nettesheim P, Snyder C, Kim JC. Vitamin A and the susceptibility of respiratory tract tissues to carcinogenic insult. Environ Health Perspect 1979;29:89–93. 10.1289/ehp.792989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kallner AB, Hartmann D, Hornig DH. On the requirements of ascorbic acid in man: steady-state turnover and body pool in smokers. Am J Clin Nutr 1981;34:1347–55. 10.1093/ajcn/34.7.1347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lykkesfeldt J, Loft S, Nielsen JB, et al. Ascorbic acid and dehydroascorbic acid as biomarkers of oxidative stress caused by smoking. Am J Clin Nutr 1997;65:959–63. 10.1093/ajcn/65.4.959 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cser MA, Majchrzak D, Rust P, et al. Serum carotenoid and retinol levels during childhood infections. Ann Nutr Metab 2004;48:156–62. 10.1159/000078379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thurnham DI, McCabe GP, Northrop-Clewes CA, et al. Effects of subclinical infection on plasma retinol concentrations and assessment of prevalence of vitamin A deficiency: meta-analysis. The Lancet 2003;362:2052–8. 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)15099-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pelletier O. Smoking and vitamin C levels in humans. Am J Clin Nutr 1968;21:1259–67. 10.1093/ajcn/21.11.1259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sargeant LA, Jaeckel A, Wareham NJ. Interaction of vitamin C with the relation between smoking and obstructive airways disease in EPIC Norfolk. European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition. Eur Respir J 2000;16:397–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shin JY, Shim JY, Lee DC, et al. Smokers with adequate vitamin C intake show a preferable pulmonary function test. J Am Coll Nutr 2015;34:385–90. 10.1080/07315724.2014.926152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Park HJ, Byun MK, Kim HJ, et al. Dietary vitamin C intake protects against COPD: the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey in 2012. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2016;11:2721–8. 10.2147/COPD.S119448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Joshi P, Kim WJ, Lee SA. The effect of dietary antioxidant on the COPD risk: the community-based KoGES (Ansan-Anseong) cohort. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2015;10:2159–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Al-Rejaie S, Abuohashish H, Alkhamees O, et al. Gender difference following high cholesterol diet induced renal injury and the protective role of rutin and ascorbic acid combination in Wistar albino rats. Lipids Health Dis 2012;11:41 10.1186/1476-511X-11-41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jiao Y, Chen H, Yan J, et al. Genome-wide gene expression profiles in antioxidant pathways and their potential sex differences and connections to vitamin C in mice. Int J Mol Sci 2013;14:10042–62. 10.3390/ijms140510042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.