Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the effects of the T-cell costimulation blocker abatacept on anti-citrullinated protein antibodies (ACPA) and rheumatoid factor (RF) in early rheumatoid arthritis (RA), and associations between changes in serological status and clinical response.

Methods

Post hoc analysis of the phase III AGREE study in methotrexate (MTX)-naïve patients with early RA and poor prognostic factors. Patients were randomised to abatacept (~10 mg/kg intravenously according to weight range) or placebo, plus MTX over 12 months followed by open-label abatacept plus MTX for 12 months. Autoantibody titres were determined by ELISA at baseline and months 6 and 12 (double-blind phase). Conversion to seronegative status and its association with clinical response were assessed at months 6 and 12.

Results

Abatacept plus MTX was associated with a greater decrease in ACPA (but not RF) titres and higher rates of both ACPA and RF conversion to seronegative status versus MTX alone. More patients converting to ACPA seronegative status receiving abatacept plus MTX achieved remission according to Disease Activity Score in 28 joints (C-reactive protein) or Clinical Disease Activity Index than patients who remained ACPA seropositive. Patients who converted to ACPA seronegative status treated with abatacept plus MTX had a greater probability of achieving sustained remission and less radiographic progression than MTX alone or patients who remained ACPA seropositive (either treatment).

Conclusions

Treatment with abatacept plus MTX was more likely to induce conversion to ACPA/RF seronegative status in patients with early, erosive RA. Conversion to ACPA seronegative status was associated with better clinical and radiographic outcomes.

Trial registration number

Keywords: early rheumatoid arthritis, DMARD (biologic), rheumatoid factor, ant-CCP

Key messages.

What is already known about this subject?

In the AGREE study, patients with early, poor prognostic rheumatoid arthritis (RA) (erosions, highly active disease and seropositivity; 96.5% and 89.0% of patients were rheumatoid factor (RF) or anti-citrullinated protein antibody (ACPA) seropositive), who were treated with abatacept in combination with methotrexate (MTX) for 12 months achieved sustainable clinical, functional and radiographic benefits compared with patients treated with MTX alone.

What does this study add?

In patients with early erosive RA, treatment with abatacept in combination with MTX led to a decrease in autoantibody titres, resulting in some patients undergoing conversion to ACPA and RF seronegative status.

Conversion to ACPA seronegative status was associated with a better treatment response, including higher rates of remission, an increased likelihood of achieving sustained remission and less radiographic progression.

How might this impact on clinical practice?

These findings demonstrate that abatacept is an effective treatment in patients with early RA and that, by modulating T-cell responses at very early stages of the disease, it might be possible to alter underlying autoimmune processes with the potential for sustained drug-free remission.

Background

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is characterised by the production of autoantibodies, in particular rheumatoid factor (RF) and anti-citrullinated protein antibodies (ACPA).1 An estimated 50%–70% of patients with RA present with detectable ACPA titres, which are mainly of the IgG isotype and directed against post-translationally modified, citrullinated proteins.1–3 RF autoantibodies are primarily of the IgM isotype and directed against the Fc portion of the IgG isotype.1 RF and ACPA can be present without clinical symptoms for up to 10 years before the onset of RA,4–8 and as such make interesting early biomarkers for the disease. Both RF and ACPA are moderately correlated with markers of inflammation, although the correlation is greater for RF.9 ACPA is particularly sensitive for diagnosis and is a better prognostic indicator than RF for more severe RA and more rapid disease progression.1 3 In an early RA cohort, ACPA positivity was associated with a higher rate of joint destruction.10 Hecht et al demonstrated that both erosion number and size were highest in patients with concomitant ACPA and RF, and that their effects were additive.11 However, the presence of RF compared with its absence has been associated with higher disease activity in ACPA-positive patients,12 in line with the amplifying role of RF.13 In addition, RF- and ACPA-producing B cells are detectable at high levels in the synovial fluid of patients with RA, suggesting a direct contribution to synovial inflammation.14–17

A recent report from Rombouts et al provides evidence for a role of T cells in ACPA production. The authors reported that, unlike other autoantibodies or non-reactive IgG, ACPA IgG undergoes N-linked glycosylation of the Fab variable domains.18 The authors hypothesised that this glycosylation requires N-linked glycan consensus sites not present in the germline Fab domain sequence, and that these sites are introduced by somatic hypermutation of the Ig variable region.18 Somatic hypermutation occurs during the process of B-cell proliferation and differentiation that is regulated in part by activated T cells.3 In addition, the strong association between ACPA and human leucocyte antigen class II genes suggests a role for antigen-specific CD4+ T cells in the humoral immune response against citrullinated proteins.19

Abatacept is a soluble fusion protein consisting of the extracellular domain of human cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 linked to the modified Fc portion of human IgG1. Abatacept binds to CD80/CD86 on antigen-presenting cells (APC), thereby blocking the interaction between CD80/CD86 and CD28 on T cells and inhibiting T-cell costimulation.20 21 In addition to peptide–major histocompatibility complex recognition between APCs and T cells, costimulation is required for (naïve) T cells to become fully activated.1 Thus, if costimulation is blocked, T-cell-dependent B-cell differentiation into antibody-producing cells will likely be inhibited and antibody production impaired. Treatment with abatacept, through inhibition of T-cell costimulation, might therefore be expected to impact antibody production by B cells.

Abatacept is an effective treatment for both established22 23 and early RA,24 25 and early treatment of RA has been shown to prevent disease progression and joint damage.24–27 The Abatacept trial to Gauge Remission and joint damage progression in methotrexate-naïve patients with Early Erosive rheumatoid arthritis (AGREE) was a 2-year, phase III study with a 1-year, double-blind phase that assessed the efficacy, safety and tolerability of intravenous abatacept plus methotrexate (MTX) compared with placebo plus MTX, in MTX-naïve patients with early erosive RA and poor prognostic indicators.28 29 The primary results of the study demonstrated that treatment with abatacept plus MTX resulted in significantly greater and more sustained clinical and radiographic benefits than treatment with placebo plus MTX.

As abatacept’s mode of action includes inhibition of T-cell costimulation, it was hypothesised that patients who converted to a seronegative status might have a better clinical response to abatacept treatment than those who remained seropositive. This post hoc analysis of the AGREE study investigated the effects of abatacept in combination with MTX versus MTX alone on conversion to seronegative status in ACPA-seropositive and RF-seropositive patients, and the relationship between seroconversion and clinical response.

Methods

Patient population and study design

This was a post hoc analysis performed using data from the previously published AGREE study (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT00122382).28 29 Briefly, MTX-naïve patients with early RA (≤2 years since diagnosis) who were positive for RF and/or ACPA antibodies and had evidence of erosion were randomised 1:1 to receive abatacept (~10 mg/kg intravenously according to weight range) plus MTX or placebo plus MTX (hereafter referred to as ‘MTX alone’) over a 12-month double-blind period followed by open-label abatacept plus MTX for an additional 12 months.28 29 At baseline, all patients had high disease activity based on a tender joint count of ≥12, a swollen joint count of ≥10 and C-reactive protein (CRP) levels of ≥0.45 mg/dL.

Determination of autoantibody titres

Serum samples to assess levels of RF and ACPA (by assessment of second-generation anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide-2 (CCP-2) antibodies) were taken at screening and at months 6 and 12 of the double-blind period and stored at –80°C. Anti-CCP-2 and RF (IgM isotype) antibody titres were determined by ELISA; for each patient, samples from different time points were analysed within the same assay. The cut-off for ACPA positivity was 5 AU/mL and 15 IU/mL for RF positivity.

Outcome measures

ACPA and RF seroconversion was determined by comparing baseline antibody titres with titres at month 6 or 12 of the double-blind phase. All patients were positive for RF and/or ACPA at baseline. Those with antibody titres below the cut-off value (ACPA 5 AU/mL; RF 15 IU/mL) at month 6 or 12 were considered to have converted to a seronegative state.

Disease activity was measured using the Disease Activity Score in 28 joints (CRP) (DAS28 (CRP)) or the Clinical Disease Activity Index (CDAI) at each study visit (screening, days 1, 15 and 29, and then every 28 days) over 12 months. Remission was defined as DAS28 (CRP) <2.6 or CDAI ≤2.8. First remission was defined as the first visit at which a patient met the requirements to achieve remission. Sustained first remission was defined as the first visit at which remission was reached and subsequently maintained for every visit up to month 12. The proportions of patients in remission at months 6 and 12 and the cumulative probability of time to achieve first sustained DAS28 (CRP) remission (<2.6) over 12 months of treatment were determined.

Radiographs of the hands and feet were taken at screening, at months 6 and 12, and at the discontinuation visit. The Genant-modified Sharp scoring method was used to assess the mean change from baseline in total Sharp score (TSS), and erosion and joint space narrowing (JSN) scores at months 6 and 12.

Statistical analysis

In the original study, DAS28 (CRP)-defined remission was evaluated for the intent-to-treat population, with patients who discontinued considered to be non-responders. For the purpose of this report, all analyses were descriptive and were based on patients with DAS28 (CRP) and CDAI data available at baseline and months 6 and 12. The proportions of patients achieving remission according to DAS28 (CRP) and CDAI were analysed as point estimates with 95% CIs, estimated using classic binomial distribution. Cumulative probability of time to achieve first remission and sustained first remission according to DAS28 (CRP)-defined and CDAI criteria were evaluated based on Kaplan-Meier estimates with 95% CIs. Patients who lost remission status were censored at the time of remission loss.

Mean changes from baseline in ACPA and RF titres were evaluated by analysis of covariance with treatment, baseline score and disease status as covariates. The adjusted mean change, treatment differences and corresponding 95% CIs were presented for months 6 and 12. In addition, the proportions of patients with conversion to ACPA and RF seronegative status at months 6 and 12 were analysed using point estimates with 95% CIs. The relationship between DAS28 (CRP) or CDAI remission and conversion to ACPA or RF seronegative status was investigated by determining the proportions (95% CIs) of patients in remission by seroconversion status at months 6 and 12. Mean changes from baseline in TSS, erosion and JSN scores were evaluated by analysis of covariance with treatment, baseline score and disease status as covariates. The adjusted mean change, treatment differences and corresponding 95% CIs were presented for months 6 and 12.

Results

Patient population

In the original study, 509 patients were randomly assigned to receive abatacept plus MTX (n=256) or MTX alone (n=253).29 Of these, 459 patients completed year 1 and 433 completed year 2.28 Demographic data and baseline characteristics have been previously published.28 29 All patients were positive for RF and/or ACPA at baseline. Of the 435 patients for whom ACPA status measurements were available at baseline and both months 6 and 12, 21 (4.8%) were seronegative at month 6. Of the 461 patients for whom RF status measurements were available at baseline and both months 6 and 12, 61 (13.2%) were seronegative at month 6. Baseline RF/ACPA mean (SD) for patients who received abatacept plus MTX versus MTX alone are given in figure 1.

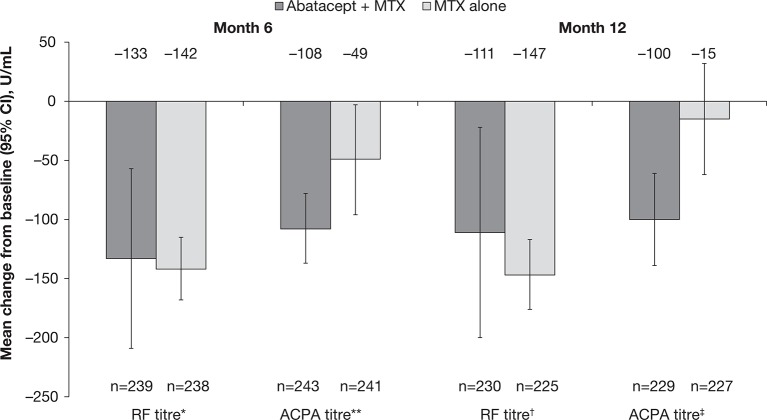

Figure 1.

ACPA and RF titres in patients with early RA treated with abatacept+MTX compared with MTX alone. Antibody titres were determined by ELISA at baseline and months 6 and 12. Baseline to month 6 and baseline to month 12 were carried out as separate analyses. Baseline means (SD) for: *abatacept+MTX versus MTX alone were 305 (469) vs 273 (342); **abatacept+MTX versus MTX alone were 305 (534) vs 272 (514); †abatacept+MTX versus MTX alone were 297 (426) vs 272 (344); ‡abatacept+MTX versus MTX alone were 300 (537) vs 270 (524). ACPA titres were determined by assessment of second-generation anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide-2 antibodies. ACPA, anti-citrullinated protein antibody; MTX, methotrexate; RA, rheumatoid arthritis; RF, rheumatoid factor.

Patient demographic data and baseline disease characteristics by conversion to ACPA and RF seronegative status at month 6 are shown in table 1. Mean baseline DAS28 (CRP) in patients who seroconverted was 6.2 in the abatacept plus MTX arm and 5.9 in the MTX alone arm. Patients who seroconverted had lower mean autoantibody levels at baseline compared with those who remained seropositive.

Table 1.

Patient demographic data and baseline disease characteristics by conversion to ACPA and RF seronegative status at month 6

| Conversion to ACPA seronegative status | Persistent ACPA seropositive | Conversion to RF seronegative status | Persistent RF seropositive | |||||

| Abatacept+MTX (n=15) |

MTX alone (n=6) |

Abatacept+MTX (n=212) |

MTX alone (n=202) |

Abatacept+MTX (n=39) |

MTX alone (n=22) |

Abatacept+MTX (n=191) |

MTX alone (n=209) |

|

| Age, years | 50.7 (11.1) | 61.2 (11.4) | 49.8 (12.3) | 48.8 (12.7) | 51.6 (10.3) | 49.5 (14.4) | 49.6 (12.6) | 49.7 (12.8) |

| Female, n (%) | 13 (86.7) | 6 (100) | 157 (74.1) | 159 (78.7) | 29 (74.4) | 18 (81.8) | 145 (75.9) | 170 (81.3) |

| Weight, kg | 65.6 (17.0) | 68.8 (16.6) | 72.3 (17.8) | 72.7 (17.9) | 71.2 (17.2) | 68.1 (16.1) | 71.9 (18.3) | 73.5 (18.1) |

| Race, white, n (%) | 14 (93.3) | 4 (66.7) | 167 (78.8) | 173 (85.6) | 34 (87.2) | 20 (90.9) | 147 (77.0) | 179 (85.6) |

| Region, n (%) | ||||||||

| North America | 2 (13.3) | 0 | 40 (18.9) | 27 (13.4) | 9 (23.1) | 3 (13.6) | 32 (16.8) | 34 (16.3) |

| South America | 5 (33.3) | 0 | 83 (39.2) | 87 (43.1) | 7 (17.9) | 9 (40.9) | 88 (46.1) | 88 (42.1) |

| Europe | 7 (46.7) | 4 (66.7) | 72 (34.0) | 75 (37.1) | 20 (51.3) | 8 (36.4) | 56 (29.3) | 74 (35.4) |

| ROW | 1 (6.7) | 2 (33.3) | 17 (8.0) | 13 (6.4) | 3 (7.7) | 2 (9.1) | 15 (7.9) | 13 (6.2) |

| Duration of RA, months | 8.9 (8.8) | 1.7 (1.5) | 6.0 (7.4) | 7.0 (7.1) | 3.7 (5.0) | 6.9 (8.0) | 7.1 (8.0) | 7.0 (7.1) |

| Tender joints | 30.0 (16.2) | 20.3 (6.9) | 31.1 (14.9) | 30.3 (13.7) | 24.6 (14.3) | 29.8 (15.0) | 32.9 (15.1) | 30.9 (14.0) |

| Swollen joints | 23.2 (10.3) | 15.8 (7.6) | 22.9 (11.7) | 22.4 (10.4) | 20.9 (9.6) | 20.4 (10.1) | 23.7 (11.9) | 22.4 (10.4) |

| Patient pain assessment | 62.5 (25.5) | 56.6 (27.4) | 67.2 (22.2) | 66.8 (22.5) | 64.6 (24.9) | 61.4 (22.3) | 67.9 (22.4) | 67.6 (22.8) |

| HAQ-DI | 1.4 (0.7) | 1.7 (0.6) | 1.7 (0.7) | 1.7 (0.7) | 1.6 (0.5) | 1.7 (0.6) | 1.7 (0.7) | 1.7 (0.7) |

| Patient global assessment, 100 mm VAS | 61.7 (25.7) | 50.3 (28.2) | 66.3 (21.3) | 64.3 (23.6) | 67.5 (22.0) | 61.5 (22.9) | 65.4 (22.6) | 63.7 (24.3) |

| Physician global assessment, 100 mm VAS | 59.4 (16.3) | 56.7 (17.4) | 67.9 (18.2) | 65.4 (19.1) | 64.1 (18.5) | 61.9 (16.0) | 68.2 (18.3) | 66.1 (19.4) |

| DAS28 (CRP) | 6.2 (0.9) | 5.9 (0.7) | 6.3 (1.0) | 6.3 (1.0) | 6.1 (0.9) | 6.0 (1.1) | 6.4 (1.0) | 6.3 (1.0) |

| DAS28 (ESR) | 7.2 (0.6) | 6.2 (0.7) | 6.9 (1.0) | 6.7 (1.1) | 6.7 (0.8) | 6.4 (1.3) | 6.9 (1.0) | 6.8 (1.1) |

| ESR, mm/hour | 44.4 (18.0) | 55.5 (34.3) | 49.5 (28.8) | 49.8 (32.9) | 48.5 (21.3) | 41.2 (24.3) | 49.4 (29.9) | 51.1 (32.7) |

| CRP, mg/dL | 2.4 (2.0) | 4.7 (3.4) | 3.3 (3.3) | 3.8 (5.4) | 3.0 (3.0) | 2.6 (3.2) | 3.2 (3.1) | 3.8 (5.4) |

| Baseline RF positive, n (%) | 14 (93.3) | 6 (100) | 204 (96.2) | 197 (97.5) | 39 (100) | 22 (100) | 191 (100) | 209 (100) |

| Baseline RF titre, IU/mL | 267.2 (465.0) | 192.2 (214.5) | 323.8 (481.4) | 297.6 (359.3) | 61.9 (84.5) | 39.2 (36.1) | 369.0 (503.5) | 306.7 (352.2) |

| Baseline ACPA positive, n (%) | 15 (100) | 6 (100) | 212 (100) | 202 (100) | 34 (87.2) | 15 (68.2) | 179 (93.7) | 185 (88.5) |

| Baseline ACPA titre, AU/mL | 18.6 (29.8) | 9.0 (2.2) | 347.9 (558.9) | 323.7 (546.2) | 202.7 (291.3) | 143.8 (226.0) | 341.3 (585.0) | 292.8 (543.4) |

| TSS | 7.1 (8.7) | 15.4 (17.1) | 7.7 (9.8) | 6.7 (8.6) | 6.6 (10.6) | 5.7 (5.9) | 7.6 (9.3) | 6.5 (8.6) |

| JSN score | 2.5 (4.6) | 5.8 (9.7) | 2.1 (4.1) | 1.8 (3.9) | 2.0 (4.8) | 1.5 (2.5) | 2.1 (3.9) | 1.9 (4.1) |

| Erosion score | 4.6 (5.0) | 9.6 (8.1) | 5.6 (6.3) | 4.9 (5.5) | 4.6 (6.2) | 4.2 (3.9) | 5.5 (6.1) | 4.6 (5.2) |

Data are mean (SD) unless stated otherwise. Conversion to ACPA or RF seronegative status at month 6 meant that patients who were ACPA or RF seropositive at baseline, respectively, became seronegative at month 6; persistent ACPA or RF seropositive meant that patients were ACPA or RF seropositive at both baseline and at month 6.

ACPA, anti-citrullinated protein antibody; CRP, C-reactive protein; DAS28, Disease Activity Score in 28 joints; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; HAQ-DI, Health Assessment Questionnaire-Disability Index; JSN, joint space narrowing; MTX, methotrexate; RA, rheumatoid arthritis; RF, rheumatoid factor; ROW, rest of world; TSS, total Sharp score; VAS, visual analogue scale.

RF and ACPA titres following treatment with abatacept plus MTX or MTX alone

A decrease in autoantibody levels after 6 and 12 months, compared with baseline, was observed for all study groups. Mean ACPA and RF titres decreased from baseline following treatment with abatacept plus MTX and MTX alone (figure 1). Whereas similar decreases in RF titres were observed in both treatment groups, treatment with abatacept plus MTX resulted in a larger decrease in ACPA titres versus MTX alone at both months 6 and 12 (the 95% CI of the estimate of difference did not cross 0; figure 1).

For patients who converted to seronegative RF status at month 6, mean decreases from baseline in autoantibody levels were numerically larger following treatment with abatacept plus MTX versus MTX alone: respectively, mean changes in RF titres (IU/mL) were −50.4 vs −28.1 at month 6, and −37.9 vs 3.2 at month 12; mean decreases in ACPA titres (AU/mL) were −116.0 vs −80.4 at month 6, and −114.2 vs −39.9 at month 12. Similar findings were observed for patients who converted to seronegative ACPA status at month 6: in the respective treatment groups, mean decreases from baseline in RF titres (IU/mL) were −233.8 vs −131.5 at month 6, and −210.7 vs −150.2 at month 12, and mean decreases in ACPA titres (AU/mL) were −15.9 vs −6.0 at month 6, and −7.4 vs −6.5 at month 12.

In contrast, among patients with persistent RF seropositivity at month 6, mean decreases from baseline in RF titres (IU/mL) were similar or numerically smaller with abatacept plus MTX versus MTX alone: −155.9 vs −159.1 at month 6, and −125.5 vs −171.8 at month 12, respectively. However, mean decreases in ACPA titres (AU/mL) for these patients were numerically larger with abatacept plus MTX versus MTX alone: −114.0 vs −47.8 at month 6, and −101.4 vs −13.0 at month 12, respectively. A similar pattern was seen for patients with persistent ACPA seropositivity at month 6: with abatacept plus MTX versus MTX alone, respectively, mean decreases from baseline in RF titres (IU/mL) were −132.8 vs −157.3 at month 6, and −105.4 vs −165.3 at month 12, whereas mean decreases from baseline in ACPA titres (AU/mL) were −123.2 vs −57.8 at month 6, and −115.4 vs −19.4 at month 12.

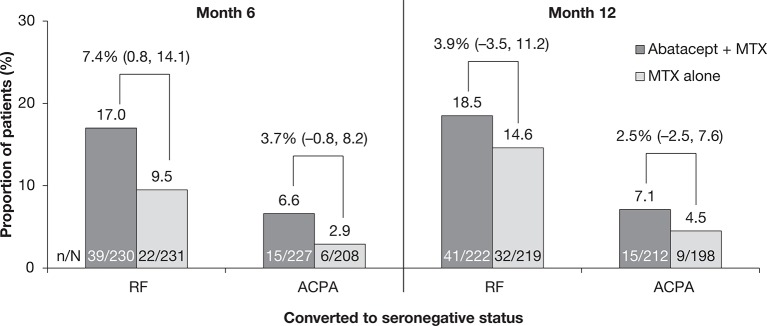

Conversion to RF and ACPA seronegative status following treatment with abatacept plus MTX or MTX alone

A numerically larger proportion of patients converted to become RF or ACPA seronegative in response to treatment with abatacept plus MTX versus MTX alone after 6 and 12 months of treatment. At month 6, 17.0% (39/230) and 6.6% (15/227) of patients treated with abatacept plus MTX were RF and ACPA seronegative, respectively, compared with 9.5% (22/231) and 2.9% (6/208) of patients treated with MTX alone. Of the patients who were RF and ACPA seronegative at month 6, 17.9% (7/39) and 13.3% (2/15) of those treated with abatacept plus MTX, and 18.2% (4/22) and 0% (0/6) of those treated with MTX alone, respectively, converted back to RF and ACPA seropositivity at month 12. At month 12, 18.5% (41/222) and 7.1% (15/212) of patients treated with abatacept plus MTX were RF and ACPA seronegative, respectively, compared with 14.6% (32/219) and 4.6% (9/198) of patients treated with MTX alone. The proportion of patients who converted to seronegative status was numerically higher in the abatacept plus MTX treatment group than in the MTX alone group. Estimated differences (95% CIs) between treatment groups for conversion to RF and ACPA seronegative status were, respectively, 7.4% (0.8–14.1) and 3.7% (−0.8 to 8.2) at month 6, and 3.9% (−3.5 to 11.2) and 2.5% (−2.5 to 7.6) at month 12; only the estimate of difference (95% CI) for RF seroconversion at month 6 did not cross 0 (figure 2), indicating that abatacept plus MTX may have a particularly prominent effect on RF seroconversion in early treatment.

Figure 2.

Conversion to ACPA and RF seronegative status in patients with early RA treated with abatacept+MTX compared with MTX alone. The proportion of patients with conversion to ACPA and RF seronegative status at months 6 and 12 and estimates of difference (95% CIs) between treatment groups are shown. Baseline to month 6 and baseline to month 12 were carried out as separate analyses. ACPA, anti-citrullinated protein antibody; MTX, methotrexate; N, total number of patients in respective analysis; n, number of patients that showed seroconversion; RA, rheumatoid arthritis; RF, rheumatoid factor.

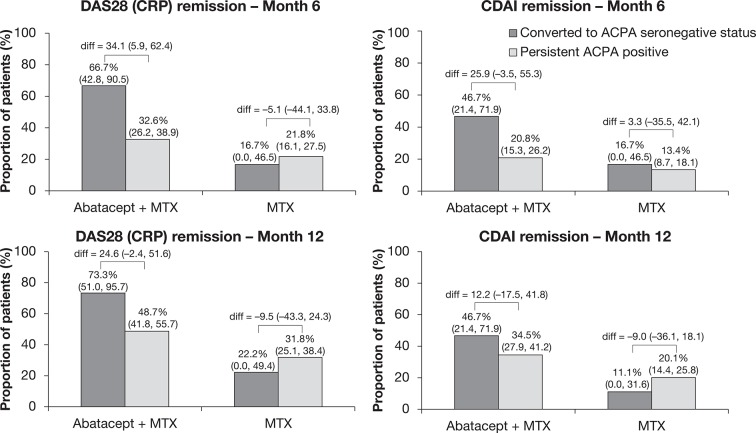

Clinical and radiographic responses by conversion to seronegative status

In the abatacept plus MTX arm, a higher proportion of patients who converted to ACPA seronegative status achieved DAS28 (CRP) and CDAI remission at month 6 compared with patients who were persistently ACPA seropositive (figure 3); the estimate of difference (95% CI) between converters to seronegative status and those who were persistently ACPA seropositive did not cross 0 for DAS28 (CRP)-defined remission at month 6. The proportions (95% CIs) of patients who converted to ACPA seronegative status in the abatacept plus MTX arm and achieved DAS28 (CRP) and CDAI remission were 66.7% (42.8–90.5) and 46.7% (21.4–71.9) at month 6, and 73.3% (51.0–95.7) and 46.7% (21.4–71.9) at month 12, respectively. In comparison, the proportions (95% CIs) of patients who were persistently ACPA seropositive and achieved DAS28 (CRP) and CDAI remission were 32.6% (26.2–38.9) and 20.8% (15.3–26.2) at month 6, and 48.7% (41.8–55.7) and 34.5% (27.9–41.2) at month 12, respectively. A higher proportion of patients treated with abatacept plus MTX achieved DAS28 (CRP) or CDAI remission at months 6 and 12 compared with patients treated with MTX alone, regardless of whether they converted to seronegative status or not. In the MTX alone arm, the proportions (95% CIs) of patients achieving DAS28 (CRP) and CDAI remission were 16.7% (0.0–46.5) and 16.7% (0.0–46.5) at month 6, and 22.2% (0.0–49.4) and 11.1% (0.0–31.6) at month 12, respectively, for patients who converted to ACPA seronegative status; and 21.8% (16.1–27.5) and 13.4% (8.7–18.1) at month 6, and 31.8% (25.1–38.4) and 20.1% (14.4–25.8) at month 12, respectively, for patients who were persistently ACPA seropositive.

Figure 3.

Percentage of patients achieving remission by conversion to ACPA seronegative status. Antibody titres were determined by ELISA at baseline and months 6 and 12. Baseline to month 6 and baseline to month 12 were carried out as separate analyses. ACPA, anti-citrullinated protein antibody; CDAI, Clinical Disease Activity Index; CRP, C-reactive protein; DAS28, Disease Activity Score in 28 joints; diff, difference; MTX, methotrexate.

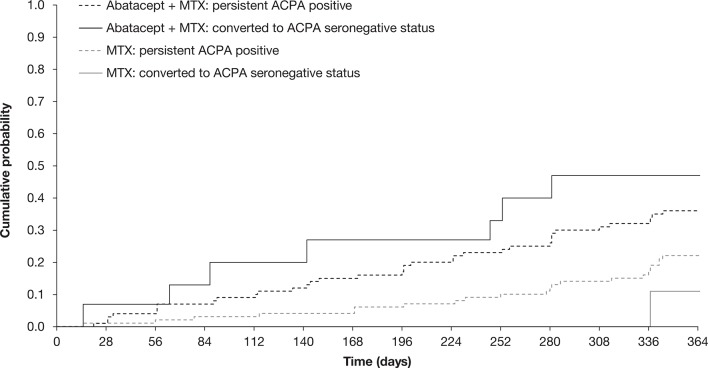

In the abatacept plus MTX treatment arm, numerically, there was a higher cumulative probability of reaching sustained first DAS28 (CRP)-defined remission among patients who converted to seronegative status compared with those who remained ACPA seropositive (figure 4). This difference was not observed among patients who received MTX alone. The proportion of patients who achieved sustained remission was consistently higher in the abatacept plus MTX treatment group versus MTX alone.

Figure 4.

Cumulative probability of time to achieve first sustained DAS28 (CRP) remission by conversion to ACPA seronegative status. The cumulative probability of the time to achieve sustained first DAS28 (CRP) remission over 12 months in all patients treated with abatacept+MTX or MTX alone who underwent conversion to ACPA seronegative status compared with those who remained ACPA seropositive was evaluated based on estimated Kaplan-Meier curves. DAS28 (CRP) values were measured at all study visits (screening, days 1, 15 and 29, and then every 28 days) over 12 months. Antibody titres were determined by ELISA at baseline and months 6 and 12. Baseline to month 6 and baseline to month 12 were carried out as separate analyses. ACPA, anti-citrullinated protein antibody; CRP, C-reactive protein; DAS28, Disease Activity Score in 28 joints; MTX, methotrexate.

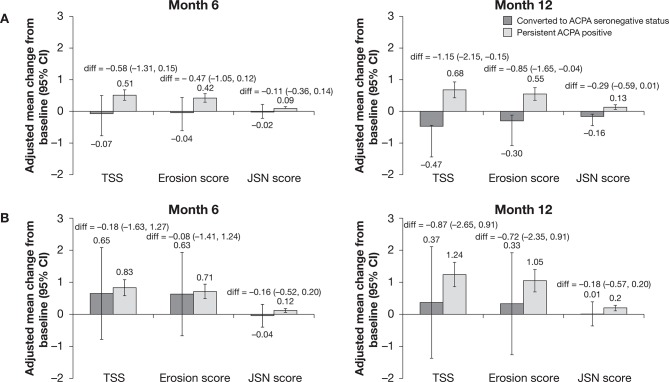

In both treatment groups, patients who underwent conversion to ACPA seronegative status showed less radiographic progression, as indicated by a smaller mean change from baseline in Genant-modified TSS, erosion and JSN scores at both month 6 and month 12, than patients who were persistently ACPA seropositive (figure 5). The estimate of difference (95% CI) between those who converted to seronegative status and those who remained ACPA seropositive did not cross 0 only for TSS and erosion score in the abatacept plus MTX group at month 12. Differences in TSS and erosion scores, but not JSN scores, between converters to ACPA seronegative status and patients who were persistently ACPA seropositive were larger among patients treated with abatacept plus MTX compared with those who received MTX alone.

Figure 5.

Radiographic outcomes in patients with early RA treated with (A) abatacept+MTX or (B) MTX alone by conversion to ACPA seronegative status. Antibody titres were determined by ELISA at baseline and months 6 and 12. Baseline to month 6 and baseline to month 12 were carried out as separate analyses. Error bars represent 95% CIs. ACPA, anti-citrullinated protein antibody; diff, difference; JSN, joint space narrowing; MTX, methotrexate; RA, rheumatoid arthritis; TSS, total Sharp score.

Discussion

In the AGREE study, patients with early, poor prognostic RA (erosions, highly active disease and seropositivity; 96.5% and 89.0% of patients were RF or ACPA seropositive), who were treated with abatacept plus MTX for 12 months achieved sustainable clinical, functional and radiographic benefits compared with patients treated with MTX alone.28–30 The present post hoc analysis investigated the effect of abatacept in combination with MTX on RF and ACPA titres and the potential association between ACPA titres and clinical response. Combined treatment with abatacept and MTX led to a decrease in both RF and ACPA titres over 6 and 12 months, and conversion to RF and ACPA seronegative status in 17.0%–18.5% and 6.6%–7.1% of patients, respectively. In those patients who converted to an autoantibody-negative status, the remission rates were higher than in those patients who did not seroconvert.

Abatacept inhibits T-cell costimulation by binding to CD80 and CD86 on APCs and blocking the binding of CD28 to CD80/86.20 B cells proliferate and differentiate into antibody-producing cells and switch from production of IgM to IgG antibodies in response to stimuli from activated CD4+ T cells, for example, increased cytokine production.3 Thus, abatacept has the potential to indirectly impact IgG isotype switching by inhibiting the costimulation and activation of T cells.

In the present study, after 6 and 12 months, a greater decrease in ACPA titres was observed with treatment with abatacept plus MTX compared with MTX alone in the overall population and by autoantibody status at month 6. Conversely, mean decreases from baseline in RF titres were similar for the two treatment arms in the overall population, although there was some evidence of a treatment effect in patients who converted to seronegative autoantibody status. In observational studies, reductions in RF as well as ACPA levels have been observed independent of the use of biological agents and, indeed, in line with the present study, more frequent RF seroconversion than ACPA seroconversion was reported. Reductions of both autoantibodies were observed in parallel with a reduction in disease activity.30 31 RF autoantibodies are primarily of the IgM isotype whereas ACPAs are primarily of the IgG isotype.1 B cells do not require T-cell help to produce IgM isotype antibodies. However, B-cell production of antibodies may change from one isotype to another through the processes of isotype switching and somatic hypermutation, which occurs during proliferation and differentiation of B cells—in part regulated by activated T cells.3 Thus, the difference in effect of abatacept plus MTX compared with MTX alone on RF versus ACPA titres might be explained by this difference in autoantibody isotype and by the effect of monotherapy versus combination therapy on B-cell subsets. Treatment with abatacept plus MTX led to higher rates of conversion to RF or ACPA seronegative status compared with treatment with MTX alone. Although abatacept inhibits T-cell activation, it also exerts anti-inflammatory effects in a T-cell-independent way,32 potentially through direct effects on B cells33 and macrophages.34

Current treatment strategies for RA employ a targeted approach aimed at reaching remission or low disease activity.35 36 The present analysis showed that in the abatacept plus MTX treatment arm the proportion of patients who achieved DAS28 (CRP)-defined or CDAI-defined remission was higher among those who converted to seronegative status than those who remained persistently ACPA seropositive. Furthermore, the cumulative probability of achieving sustained first remission according to DAS28 (CRP)-defined criteria was higher among patients who converted to ACPA seronegative status treated with abatacept plus MTX than in those who remained ACPA seropositive. The small proportion of patients who were converters to ACPA seronegative status showed less radiographic progression over 12 months than patients who remained ACPA seropositive, regardless of treatment.

These findings are in line with previous studies of abatacept in patients with early RA. In the Abatacept study to Determine the effectiveness in preventing the development of rheumatoid arthritis in patients with Undifferentiated inflammatory arthritis and to evaluate Safety and Tolerability (ADJUST) trial,24 patients with undifferentiated arthritis or very early RA treated with abatacept for 6 months had delayed disease progression and prolonged inhibition of radiographic progression after cessation of treatment versus placebo, with a decrease from baseline in RF and ACPA titres.24 In the Assessing Very Early Rheumatoid arthritis Treatment (AVERT) study,25 compared with patients treated with MTX alone, patients treated with abatacept plus MTX showed significantly higher rates of remission and a higher number of patients achieved sustained drug-free remission after withdrawal of all therapies, as well as reduced inflammation and structural damage progression as assessed by changes in MRI scores (synovitis, osteitis and bone erosions).37 Furthermore, in a post hoc analysis of the AVERT study (MTX-naïve patients with early RA and highly active and erosive disease; 100% and 95.2% of patients were ACPA and RF positive, respectively), a higher proportion of patients receiving abatacept plus MTX underwent conversion to ACPA seronegative status compared with those receiving MTX alone.38 In addition, a numerically higher proportion of patients treated with abatacept plus MTX who became seronegative (ACPA IgM isotype) achieved clinical remission at month 12 compared with those who did not seroconvert, differences that were not seen for patients treated with MTX alone.38 However, a post hoc analysis of the Abatacept versus adaliMumab comParison in bioLogic-naïvE RA patients with background MTX (AMPLE) trial suggested that, despite a similar clinical response over 2 years between the two treatment groups, only abatacept plus MTX produced a continuous decline in the median levels of most ACPAs beyond 1 year of treatment; an effect that was not sustained with adalimumab plus MTX.39

In the abatacept plus MTX group, a link between conversion to seronegative status and remission/inhibition of structural damage was noticeable, while this link was less obvious in the MTX group. Taken together, these data demonstrate that abatacept is an effective treatment in patients with early RA and that, by modulating T-cell responses at very early stages of the disease, it might be possible to alter underlying autoimmune processes; that is, slowing or halting disease progression with the potential for sustained drug-free remission.

There are limitations to post hoc analyses, which should be considered when interpreting the data presented here. The present post hoc analysis was a completers-only analysis, carried out on a relatively small subset of patients included in the original AGREE study who had complete data sets. Given the small numbers of patients with seroconversion, particularly those who converted to ACPA seronegative status, the findings should be interpreted with caution. The study was not designed or powered to detect differences between the treatment groups based on seroconversion status, and all analyses were descriptive in nature. The findings would benefit from validation in a larger patient population.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the present post hoc analysis demonstrated that treatment with abatacept in combination with MTX led to a decrease in autoantibody titres, resulting in some patients undergoing conversion to RF and ACPA seronegative status. Conversion to ACPA seronegative status was associated with higher rates of remission, an increased likelihood of achieving sustained remission and less radiographic progression.

Acknowledgments

Yedid Elbez, biostatistician at Excelya, Boulogne-Billancourt, France, contributed to the writing of the manuscript and analysis of the data. Professional medical writing and editorial assistance was provided by Catriona McKay at Caudex and was funded by Bristol-Myers Squibb.

Footnotes

Contributors: PE, JSS, RW, MLB, SEC, REMT and TWJH made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the work and interpretation of the data. DTSLJ drafted the work and participated in the analysis and interpretation of data. JY participated in the statistical analysis and interpretation of the results. All authors were involved in critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content and all authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript to be published.

Funding: This study was funded by Bristol-Myers Squibb.

Competing interests: PE: clinical trials and expert advice: Pfizer, MSD, AbbVie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, UCB, Roche, Novartis, Samsung, Sandoz and Lilly. JSS: expert advice and speakers’ bureau: Bristol-Myers Squibb; institutional grants: Phadia. RW: advisory board: Janssen; principal investigator: Galapagos; research grants: Roche; speakers’ bureau: Bristol-Myers Squibb. MLB: employee and shareholder: Bristol-Myers Squibb. SEC: employee and shareholder: Bristol-Myers Squibb. JY: employee and shareholder: Bristol-Myers Squibb. TWJH: the Department of Rheumatology at LUMC has received lecture fees/consultancy fees from Merck, UCB, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Biotest, Pfizer, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, Roche, Sanofi-Aventis, Abbott, Crescendo Bioscience, Nycomed, Boehringer, Takeda, Zydus, Epirus and Eli Lilly. DTSLJ and REMT: nothing to disclose.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: The protocol and patients’ informed consent for the original AGREE study received institutional review board/independent ethics committee approval, and the study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was consistent with International Conference on Harmonisation Good Clinical Practice.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: BMS policy on data sharing may be found at https://www.bms.com/researchers-and-partners/clinical-trials-and-research/disclosure-commitment.html

References

- 1. Scott DL, Wolfe F, Huizinga TW. Rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet 2010;376:1094–108. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60826-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Schellekens GA, de Jong BA, van den Hoogen FH, et al. . Citrulline is an essential constituent of antigenic determinants recognized by rheumatoid arthritis-specific autoantibodies. J Clin Invest 1998;101:273–81. 10.1172/JCI1316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. van Heemst J, van der Woude D, Huizinga TW, et al. . HLA and rheumatoid arthritis: how do they connect? Ann Med 2014;46:304–10. 10.3109/07853890.2014.907097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Aho K, Heliövaara M, Maatela J, et al. . Rheumatoid factors antedating clinical rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol 1991;18:1282–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Aho K, von Essen R, Kurki P, et al. . Antikeratin antibody and antiperinuclear factor as markers for subclinical rheumatoid disease process. J Rheumatol 1993;20:1278–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Nielen MM, van Schaardenburg D, Reesink HW, et al. . Specific autoantibodies precede the symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis: a study of serial measurements in blood donors. Arthritis Rheum 2004;50:380–6. 10.1002/art.20018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rantapää-Dahlqvist S, de Jong BA, Berglin E, et al. . Antibodies against cyclic citrullinated peptide and IgA rheumatoid factor predict the development of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2003;48:2741–9. 10.1002/art.11223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. van de Stadt LA, de Koning MH, van de Stadt RJ, et al. . Development of the anti-citrullinated protein antibody repertoire prior to the onset of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2011;63:3226–33. 10.1002/art.30537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ursum J, Bos WH, van de Stadt RJ, et al. . Different properties of ACPA and IgM-RF derived from a large dataset: further evidence of two distinct autoantibody systems. Arthritis Res Ther 2009;11:R75 10.1186/ar2704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. van der Helm-van Mil AH, Verpoort KN, Breedveld FC, et al. . Antibodies to citrullinated proteins and differences in clinical progression of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther 2005;7:R949–58. 10.1186/ar1767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hecht C, Englbrecht M, Rech J, et al. . Additive effect of anti-citrullinated protein antibodies and rheumatoid factor on bone erosions in patients with RA. Ann Rheum Dis 2015;74:2151–6. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-205428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Aletaha D, Alasti F, Smolen JS. Rheumatoid factor, not antibodies against citrullinated proteins, is associated with baseline disease activity in rheumatoid arthritis clinical trials. Arthritis Res Ther 2015;17:229 10.1186/s13075-015-0736-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Laurent L, Anquetil F, Clavel C, et al. . IgM rheumatoid factor amplifies the inflammatory response of macrophages induced by the rheumatoid arthritis-specific immune complexes containing anticitrullinated protein antibodies. Ann Rheum Dis 2015;74:1425–31. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Amara K, Steen J, Murray F, et al. . Monoclonal IgG antibodies generated from joint-derived B cells of RA patients have a strong bias toward citrullinated autoantigen recognition. J Exp Med 2013;210:445–55. 10.1084/jem.20121486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 15. Jasin HE. Autoantibody specificities of immune complexes sequestered in articular cartilage of patients with rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum 1985;28:241–8. 10.1002/art.1780280302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Snir O, Widhe M, Hermansson M, et al. . Antibodies to several citrullinated antigens are enriched in the joints of rheumatoid arthritis patients. Arthritis Rheum 2010;62:44–52. 10.1002/art.25036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wernick RM, Lipsky PE, Marban-Arcos E, et al. . IgG and IgM rheumatoid factor synthesis in rheumatoid synovial membrane cell cultures. Arthritis Rheum 1985;28:742–52. 10.1002/art.1780280704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Rombouts Y, Willemze A, van Beers JJ, et al. . Extensive glycosylation of ACPA-IgG variable domains modulates binding to citrullinated antigens in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2016;75:578–85. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-206598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Huizinga TW, Amos CI, van der Helm-van Mil AH, et al. . Refining the complex rheumatoid arthritis phenotype based on specificity of the HLA-DRB1 shared epitope for antibodies to citrullinated proteins. Arthritis Rheum 2005;52:3433–8. 10.1002/art.21385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Linsley PS, Nadler SG. The clinical utility of inhibiting CD28-mediated costimulation. Immunol Rev 2009;229:307–21. 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2009.00780.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Moreland L, Bate G, Kirkpatrick P. Abatacept. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2006;5:185–6. 10.1038/nrd1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Genovese MC, Becker JC, Schiff M, et al. . Abatacept for rheumatoid arthritis refractory to tumor necrosis factor alpha inhibition. N Engl J Med 2005;353:1114–23. 10.1056/NEJMoa050524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kremer JM, Westhovens R, Leon M, et al. . Treatment of rheumatoid arthritis by selective inhibition of T-cell activation with fusion protein CTLA4Ig. N Engl J Med 2003;349:1907–15. 10.1056/NEJMoa035075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Emery P, Durez P, Dougados M, et al. . Impact of T-cell costimulation modulation in patients with undifferentiated inflammatory arthritis or very early rheumatoid arthritis: a clinical and imaging study of abatacept (the ADJUST trial). Ann Rheum Dis 2010;69:510–6. 10.1136/ard.2009.119016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Emery P, Burmester GR, Bykerk VP, et al. . Evaluating drug-free remission with abatacept in early rheumatoid arthritis: results from the phase 3b, multicentre, randomised, active-controlled AVERT study of 24 months, with a 12-month, double-blind treatment period. Ann Rheum Dis 2015;74:19–26. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-206106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kremer JM, Russell AS, Emery P, et al. . Long-term safety, efficacy and inhibition of radiographic progression with abatacept treatment in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and an inadequate response to methotrexate: 3-year results from the AIM trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2011;70:1826–30. 10.1136/ard.2010.139345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kremer JM, Peterfy C, Russell AS, et al. . Longterm safety, efficacy, and inhibition of structural damage progression over 5 years of treatment with abatacept in patients with rheumatoid arthritis in the abatacept in inadequate responders to methotrexate trial. J Rheumatol 2014;41:1077–87. 10.3899/jrheum.130263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bathon J, Robles M, Ximenes AC, et al. . Sustained disease remission and inhibition of radiographic progression in methotrexate-naive patients with rheumatoid arthritis and poor prognostic factors treated with abatacept: 2-year outcomes. Ann Rheum Dis 2011;70:1949–56. 10.1136/ard.2010.145268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Westhovens R, Robles M, Ximenes AC, et al. . Clinical efficacy and safety of abatacept in methotrexate-naive patients with early rheumatoid arthritis and poor prognostic factors. Ann Rheum Dis 2009;68:1870–7. 10.1136/ard.2008.101121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Smolen JS, Wollenhaupt J, Gomez-Reino JJ, et al. . Attainment and characteristics of clinical remission according to the new ACR-EULAR criteria in abatacept-treated patients with early rheumatoid arthritis: new analyses from the Abatacept study to Gauge Remission and joint damage progression in methotrexate (MTX)-naive patients with Early Erosive rheumatoid arthritis (AGREE). Arthritis Res Ther 2015;17:157 10.1186/s13075-015-0671-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Böhler C, Radner H, Smolen JS, et al. . Serological changes in the course of traditional and biological disease modifying therapy of rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2013;72:241–4. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Jansen DT, el Bannoudi H, Arens R, et al. . Abatacept decreases disease activity in a absence of CD4(+) T cells in a collagen-induced arthritis model. Arthritis Res Ther 2015;17:220 10.1186/s13075-015-0731-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Rozanski CH, Arens R, Carlson LM, et al. . Sustained antibody responses depend on CD28 function in bone marrow-resident plasma cells. J Exp Med 2011;208:1435–46. 10.1084/jem.20110040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bonelli M, Ferner E, Göschl L, et al. . Abatacept (CTLA-4IG) treatment reduces the migratory capacity of monocytes in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2013;65:599–607. 10.1002/art.37787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Singh JA, Saag KG, Bridges SL Jr, et al. . 2015 American College of Rheumatology Guideline for the Treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol 2016;68:1–26. 10.1002/art.39480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Smolen JS, Landewé R, Breedveld FC, et al. . EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: 2013 update. Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73:492–509. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Peterfy C, Burmester GR, Bykerk VP, et al. . Sustained improvements in MRI outcomes with abatacept following the withdrawal of all treatments in patients with early, progressive rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2016;75:1501–5. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-208258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Huizinga TWJ, Connolly SE, Johnsen A, et al. . Effect of anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide 2 immunoglobulin M serostatus on efficacy outcomes following treatment with abatacept plus methotrexate in the AVERT trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2015;74(Suppl 2):234–5. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-eular.1983 24106048 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Connolly S, Maldonado M, Schiff M, et al. . Modulation of the ACPA fine specificity in patients with RA treated with either abatacept or adalimumab in the AMPLE study. Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73(Suppl 2):395 10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-eular.2469 [DOI] [Google Scholar]