Abstract

Background

Dispositional impulsivity has been consistently implicated as a risk factor for problem drinking among college students and research suggests that this relationship may be explained in part by alcohol expectancies. A subset of alcohol expectancies, sex-related alcohol expectancies, is particularly linked to problem drinking among college students. The acquired preparedness model of risk postulates that people with dispositional impulsivity develop stronger sex-related alcohol expectancies, are subsequently more likely to drink at problematic levels in sexual situations, and thus, engage in more problem drinking.

Objectives

Using this model, the current study examined whether sex-related alcohol expectancies and alcohol use at sex mediated the relationship between impulsivity and problem drinking among college students.

Methods

College students (N = 101) completed self-report measures of alcohol use, sex-related alcohol expectancies, and five dimensions of impulsivity: negative urgency, positive urgency, sensation seeking, lack of premeditation and lack of perseverance.

Results

Two facets of impulsivity—sensation seeking and lack of premeditation—provided unique contributions to problem drinking. Sex-related alcohol expectancies significantly mediated the effects of lack of premeditation and sensation seeking on problem drinking. In support of the acquired preparedness model, the relationship between the impulsivity traits and problem drinking was serially mediated by sex-related alcohol expectancies and alcohol use at sex.

Conclusions

Results suggest that sensation seeking and lack of premeditation continue to be areas of intervention for problem drinking among college students, and implicate sex-related alcohol expectancies as an area of intervention for alcohol use at sex and problem drinking.

Keywords: impulsivity, alcohol use, college students, expectancies, sexual risk-taking

Introduction

The prevalence of alcohol use among young adults age 18-24 exceeds that of any other age group within the United States (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2012; Courtney & Polich, 2009). Further, drinking rates among young adults attending college are higher than those of their same-aged, non-college peers (Hingson, Heeren, Zakocs, Kopstein, & Wechsler, 2002; Hingson, Zha, & Weitzman, 2009). Johnston et al. (2015) found that 63% of American college students used alcohol in the past 30-days and 35% reported a recent occasion of binge drinking compared to 56% and 29%, respectively, of non-college young adults. These high rates of alcohol use and binge drinking among college students are concerning, as such rates have persisted for the past 30 years (Johnston et al., 2015) and are associated with profound mental, social, and physical health consequences, including unintentional injury and death (Hingson et al., 2009), and increased risk for sexually transmitted infections as a consequence of alcohol-related risky sexual behavior (Caldeira et al., 2010; Neal & Fromme, 2007). For example, 21.2% of American college students report having unprotected sex after drinking alcohol in the past year (American College Health Association [ACHA], 2016). Moreover, risk of being a victim or perpetrator of coerced sex has been shown to increase as a function of level of intoxication among college students (Neal & Fromme, 2007).

Problematic alcohol use has been defined by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism as excessive consumption of alcohol in frequency and/or quantity (Enoch & Goldman, 2002). Among college students, dispositional impulsivity has been identified as an important personality trait in understanding risk for problem drinking behaviors and related consequences (Baer, 2002; Ham & Hope, 2003). For example, a review by Ham & Hope (2003) identified that students of the sensation seeking personality type were at greatest risk for drinking compared to other types. Similarly, Baer (2002) illustrated that sensation seeking and impulsivity were more consistently related to increased drinking than any other individual factor (e.g., social affiliation, family, motives and norms). However, some have raised concern about use of “impulsivity” in risk models, as disparate definitions have been used for the construct across studies. These have included acting without premeditation, sensation seeking, risk-taking, novelty seeking, adventurousness, boredom susceptibility, unreliability, and unorderliness (Depue & Collins, 1999; Whiteside & Lynam, 2001). Thus, researchers have suggested that different conceptualizations of impulsivity should be considered when examining risk for drinking and drinking-related problems (Curcio & George, 2011).

As such, researchers have identified five dimensions of impulsive behavior that are inter-related, but that each represent a distinct psychological disposition towards rash action (Cyders & Smith, 2007, 2008; Whiteside & Lynam, 2001) and have been shown to differentially predict drinking patterns among college students (Coskunpinar, Dir, & Cyders, 2013; Curcio & George, 2011; Cyders, Flory, Rainer, & Smith, 2009). Two traits represent a higher-order affect-based disposition. Positive and negative urgency—defined as the tendency to act rashly in response to intense positive and negative mood, respectively—have consistently been shown to predict increases in drinking quantity (Curcio & George, 2011; Coskunpinar et al., 2013; Cyders et al., 2009; Fischer & Smith, 2008; LaBrie, Kenney, Napper, & Miller, 2014; Settles et al., 2012; Settles, Cyders, & Smith, 2010). In contrast, sensation seeking—defined as a tendency to seek out novel or thrilling stimulation and sensations—is associated with history of heavy drinking (Lynam & Miller, 2004), drinking quantity, drinking frequency and daily alcohol use in cross-sectional studies (Curcio & George, 2011; Fischer & Smith, 2008; LaBrie et al., 2014; Magid, MacLean, & Colder, 2007; Miller, Flory, Lynam, & Leukefeld, 2003) and has been shown to predict increases in frequency of drinking in a prospective study (Cyders et al., 2009).

Related to a disposition characterized by low conscientiousness, lack of premeditation refers to the tendency to act without forethought or care of potential consequences. Like sensation seeking, lack of premeditation is associated with frequency of alcohol use (Fischer & Smith, 2008; Miller et al., 2003) and has also been associated with lifetime frequency of heavy drinking (Lynam & Miller, 2004) among college students. Researchers have suggested that students low on premeditation may not consider the negative consequences of alcohol use before drinking, and thus may be more likely to engage in higher levels of use (Shin, Hong, & Jeon, 2012). As such, lack of premeditation has been associated with problem drinking among college samples (Adams, Kaiser, Lynam, Charnigo, & Milich, 2012) and has been shown to be the strongest predictor of drinking frequency of all five dimensions of impulsivity among young adults (Lynam & Miller, 2004; Miller et al., 2003). However, one study by Cyders and colleagues (2009) found that lack of premeditation did not longitudinally predict drinking frequency or drinking quantity above and beyond what is predicted by the urgency traits and sensation seeking.

Like lack of premeditation, lack of perseverance—defined as an inability to tolerate boredom or remain focused on a task—is a disposition related to low conscientiousness (Whiteside & Lynam, 2001). Coskunpinar et al. (2013) conducted a meta-analysis utilizing 96 studies examining the relationship between impulsivity and drinking outcomes among clinical and non-clinical adult and youth samples. The authors reported that the bivariate relationship between impulsivity and drinking quantity was largest for lack of perseverance compared to correlations observed among the other traits. Research that has exclusively examined the relationship between lack of perseverance and drinking among college populations is more limited, and although a significant bivariate correlation has observed between lack of perseverance and drinking outcomes, most studies show that lack of perseverance does not predict indicators of problem drinking (e.g., frequency, quantity, binge) above and beyond what is predicted by the other dimensions of impulsivity (Cyders et al., 2009; Miller et al., 2003; Lynam & Miller, 2004; Shin et al., 2012; Smith et al., 2007). Thus the unique predictability of lack of perseverance on drinking outcomes among college populations after controlling for the effect of other impulsivity traits appears to be limited.

The relationship between impulsivity traits and problem drinking among college students may be explained in part by learned alcohol expectancies. The Acquired Preparedness Model of risk (AP Model; Smith & Anderson, 2001) posits that adolescents with dispositional impulsivity are predisposed to form positive expectancies for behaviors such as alcohol use due to a learning bias toward reinforcing rather than punishing consequences of such behavior. Several tests of the AP Model have provided support for the theory's application to problem drinking among college students. For example, those high in positive and negative urgency at the start of college endorse more alcohol expectancies after the first semester, and are subsequently more likely to drink in higher quantities after the first year of college (Settles et al., 2010). A similar mediation pathway has been found with sensation seeking: alcohol expectancies explain its relationship with drinking among college students (Darkes, Greenbaum, & Goldman, 2004; Finn, Sharkansky, Brandt, & Turcotte, 2000).

A subset of alcohol expectancies, sex-related alcohol expectancies, is particularly linked to problem drinking among college samples. The AP Model would postulate that young people with higher dispositional impulsivity develop more positive sex-related alcohol expectancies, or beliefs that alcohol will enhance their sexual experience, and thus, are more likely to drink at problematic levels in sexual situations and engage in problematic drinking more generally. Accordingly, researchers have shown that positive sex-related alcohol expectancies increase the frequency of drinking and likelihood of intoxication before sex in both cross-sectional (Carey, 1995; Dermen & Cooper, 1994b; Leigh, 1990; Patrick & Maggs, 2009) and prospective study designs (Kalichman & Cain, 2004; White, Fleming, Catalano, & Bailey, 2009), suggesting a causal effect of these expectancies. Additionally, a recent study documented a mediation model in which individuals with higher negative urgency and sensation seeking reported more positive sex-related alcohol expectancies, which was associated with more problem drinking (Dir, Cyders, & Coskunpinar, 2013). However, the full indirect path model, in which alcohol use at sex mediates the relationship between sex-related alcohol expectancies and problem drinking, has not been examined.

Given evidence supporting the AP Model that sex-related alcohol expectancies mediate the relationship between certain dimensions of impulsivity and problem drinking, and also predict alcohol use at sex, we aim to examine whether a full indirect effects model exists in which dispositional impulsivity works through sex-related alcohol expectancies and alcohol use at sex to affect problem drinking among college students. Thus, we hypothesize that when examining the facets of impulsivity together, consistent with the previous findings and theory of the impulsivity dimensions, sensation seeking, lack of premeditation, positive urgency and negative urgency will predict unique variance in problem drinking. However, based on existing literature, we hypothesize that lack of perseverance will have no effect on problem drinking. Consistent with previous literature and expectancy theory we also hypothesize that these relationships between impulsivity and problem drinking are positive and mediated by sex-related alcohol expectancies. Finally, we expect the relationship between sex-related alcohol expectancies and problem drinking to be further mediated by alcohol use at sex, so that the relationship between impulsivity and problem drinking is serially mediated by sex-related alcohol expectancies and alcohol use at sex, respectively. Although a casual conclusion cannot be inferred regarding mediation due to the cross-sectional nature of the data, the indirect pathways will be tested using a statistical meditation model.

Methods

Participants

Participants were 101 college students age 18–33 (M = 20.16, SD = 2.65) at an urban, mid-western university enrolled in an introductory psychology course. The majority of participants reported being female (58.8%), European-American (79.4%), heterosexual (91.2%) and engaged in a committed romantic relationship (52.9%; see Table 1 for full descriptive statistics).

Table 1. Demographics and descriptive statistics for the college sample (N = 101).

| Variable | N or Mean | % or SD |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 20.16 | 2.66 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 41 | 40.6 |

| Female | 60 | 59.4 |

| Race | ||

| European-American/White | 81 | 80.2 |

| African-American/Black | 6 | 5.9 |

| Asian-American/Pacific Islander | 3 | 3.0 |

| Multi-racial | 6 | 5.9 |

| Other | 5 | 5.0 |

| Urgency | 2.06 | .54 |

| Sensation seeking | 2.78 | .59 |

| Lack of premeditation | 1.90 | .46 |

| Lack of perseverance | 1.90 | .46 |

| Sex-related alcohol expectancies | 37.94 | 16.35 |

| Alcohol at sex | 1.86 | .97 |

| Problem drinking | 2.85 | 2.64 |

Measures

Impulsivity

The UPPS-P Impulsive Behavior Scale (Lynam et al., 2006) was used to measure five dimensions of impulsivity: lack of premeditation, lack of perseverance, negative urgency, positive urgency and sensation seeking. Responses on this 59-item scale range from 1 (agree strongly) to 4 (disagree strongly) with higher scores indicating more impulsive tendencies. The five subscales range from 10-to-14 items, and have shown good convergent validity and good discriminant validity from each other. Estimates of internal consistency for each scale were good in the current sample (positive urgency: α = .93; negative urgency: α = .88; sensation seeking: α = .86; lack of premeditation: α = .84; lack of perseverance: .80).

Sex-related alcohol expectancies

The Sex-Related Alcohol Expectancy Questionnaire (Dermen & Cooper, 1994a) measures positive sex-related alcohol expectancies on a scale from 1 (disagree strongly) to 6 (agree strongly), with higher scores indicating more positive sex-related alcohol expectancies. The 13-item scale is composed of three subscales: sexual enhancement, sexual risk taking, and disinhibition of sexual behavior. However, the total scaled score was used for the current study due to its strong reliability estimate in this sample (α = .95).

Alcohol use at sex

One item adapted from Hendershot, Stoner, George, and Norris (2007) assessed frequency of alcohol use before or during sex: “In the last year, how much of the time have you used alcohol when you've had sexual intercourse.” A 5-point Likert-type response was used with the following response options: Never (1), Rarely (2), Sometimes (3), Often (4), Always (5).

Problem drinking

Problem drinking was measured using the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test–Consumption (AUDIT–C; Bush, Kivlahan, McDonell, Fihn, & Bradley, 1998; Saunders, Aasland, Babor, de la Fuente, & Grant, 1993). The AUDIT–C is a 3-item measure developed as a brief screener for problem drinking based on reported drinking frequency, drinking quantity, and frequency of binge drinking. Each item is scored from 0–4 for a scaled score ranging from 0-12. The AUDIT–C has been established as a valid screening tool in the general population (Dawson, Grant, Stinson, & Zhou, 2006) and among young adults (Kelly, Donovan, Chung, Bukstein, &Cornelius, 2009). It has been shown to perform better than the full AUDIT in identifying heavy drinkers (Bush et al., 1998), and is predictive of negative health outcomes among young adult pouplations (Brown & Vanable, 2007). The AUDIT-C showed strong internal consistency in the current samlpe (α = .83).

Procedure and Data Analysis

One hundred ten participants completed the questionnaire online and were compensated with research participation credit for class per university IRB approval. Data were screened for outliers on the variables of interest and age; univariate skewness and kurtosis were also examined for the variables of interest and each were found to be within an acceptable range. One participant was excluded for age (> 35) and 8 others were excluded for missing more than 70% of data on a study variable for a total sample size of 101.

All analyses were performed using SPSS 20.0. A hierarchical linear regression analysis was performed to determine the contribution of each dimension of impulsivity to problem drinking. Age and gender were entered into the first step and all impulsivity-related variables were entered into the second step to evaluate their unique and combined contribution to problem drinking.

Analyses of indirect effects were performed using the PROCESS macro (Hayes, 2013) to explore the relationship between each facet of impulsivity and problem drinking, with sex-related alcohol expectancies (simple mediation: Model 4 specified by Hayes, 2013) and alcohol use at sex (serial mediation with two mediators: Model 6 specified by Hayes, 2013) as mediators. Although the term mediation is used for these analyses, given the cross-sectional nature of the data, temporal order could not be explicitly examined. However, Model 4 and 6 provide indirect effects, which are consistent with mediation analysis (Preacher & Hayes, 2004). The PROCESS macro estimates the total and direct effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable, as well as the indirect effect of the independent variable through the mediator(s). It uses bootstrapping, a technique which does not carry a normality assumption, to generate bias-corrected confidence intervals for the indirect effect and various indices of effect size for the indirect effect (Hayes, 2013). For all analyses of indirect effects in the current study, we used 5,000 bootstrap samples and age and gender were included as covariates.

Results

Missing Data

Scaled scores were computed for the UPPS-P subscales and sex-related alcohol expectancies if no more than one item on each scale was missing. No data was imputed for missing items on the UPPS-P subscales, as scaled scores are computed as the mean of all items. Included in these analyses are 12 cases that were missing one item on the UPPS-P; these cases did not differ from the others on any study variable. Mean-substitution scores were imputed for the missing items on the sex-related alcohol expectancies scale. Participants with imputed items on this scale (n = 2) also did not differ on any study variable.

Preliminary Analyses

Preliminary analyses indicated no differences based on age, but men had significantly higher AUDIT–C scores than women (t = 2.03, p = .045). Pearson's correlations indicated that negative urgency and positive urgency were strongly correlated (r = .80, p < .001), suggesting that they measured similar constructs in this sample. Further, these traits were highly collinear in predicting problem drinking (VIF = 2.76). Considering their collinearity and that these two traits are regarded as lower-order facets of a higher-order urgency domain (Cyders & Smith, 2007), a composite score of negative urgency (M = 2.24, SD = .56) and positive urgency (M = 1.90, SD = .59) items was calculated (as the mean score of items of both scales) and used for subsequent analyses (urgency; M = 2.06, SD = .54). The data showed strong internal consistency on this composite measure (α = .95), which is consistent with previous research that has reliably combined negative and positive urgency (Smith, Guller, & Zapolski, 2013).

Patterns of Alcohol Use

The majority of our sample (70.3%) reported drinking at least occasionally in the past year. Among those who reported past year use, 36.6% reported drinking no more than 2-4 times per month. Another 42.3% reported drinking at least 2-4 times per week, and 21.1% reported drinking 4 or more times per week. Of the total sample, 47.5% of students received a score on the AUDIT–C (M = 2.85, SD = 2.64) indicating hazardous alcohol use (43.33% of women scored 3 or higher and 53.66% of men scored 4 or higher). The majority of our sample (51.5%) also reported using alcohol before or during sex in the past year (M = 1.86, SD = .97), frequency of which was strongly correlated with problem drinking (r = .69, p< .001).

Regression analysis

Bivariate correlations between the study variables were conducted and are presented in Table 2. Next, regression analyses were run predicting problem drinking. Controlling for age and gender, sensation seeking (b = 1.33, β = .30, p = .003) and lack of premeditation (b = 1.61, β = .28, p = .012) significantly predicted problem drinking, but urgency (b = -.11, β = -.02, ns) and lack of perseverance (b = .28, β = .05, ns) did not. Notably, sensation seeking was the strongest predictor of problem drinking, uniquely accounting for 7.51% of variance in scores, followed by lack of premeditation, which uniquely predicted 5.29% of the variance in scores.

Table 2. Associations of study variables.

| GEN | URG | SS | LPM | LPV | SRAE | AUS | ALC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AGE | .18 | .01 | .02 | .03 | -.06 | -.03 | .15 | .11 |

| GEN | .10 | .19 | .01 | .05 | .16 | .01 | .20* | |

| URG | .19* | .42*** | .47*** | .35*** | .12 | .19 | ||

| SS | .15 | -.10 | .22* | .27** | .36*** | |||

| LPM | .51*** | .31** | .28** | .34*** | ||||

| LPV | .24* | .07 | .15 | |||||

| SRAE | .44*** | .43*** | ||||||

| AUS | .69*** |

Note. N = 101 college students. AGE = age; GEN = gender (0 = female, 1 = male); URG = composite score of positive and negative urgency; SS = sensation seeking; LPM = lack of premeditation; LPV = lack of perseverance; SRAE = sex-related alcohol expectancies; AUS = alcohol use at sex; ALC = problem drinking.

p< .05,

p < .01,

p< .001, two-tailed

Indirect Effect Analyses

Urgency was not significantly associated with problem drinking, and failed to predict problem drinking when other facets of impulsivity were considered. Thus, urgency was not included in analyses of indirect effects, precluding us from fully testing our second hypothesis.

Sensation seeking

Sex-related alcohol expectancies mediated the relationship between sensation seeking and problem drinking: higher sensation seeking was associated with more positive sex-related alcohol expectancies (b = 5.44,β = .20, p=.052);sex-related alcohol expectancies in turn predicted problem drinking (b = .06, β = .36,p< .001) when controlling for sensation seeking. The estimate of the indirect effect of sensation seeking on problem drinking through sex-related alcohol expectancies was significant (point estimate = .32, Boot SE = .20, 95% Boot CI:.01, .83). The direct effect of sensation seeking on problem drinking was also significant (b = 1.16,β = .26, p= .005), suggesting that this relationship is only partially explained by sex-related alcohol expectancies.

Lack of premeditation

Lack of premeditation was significantly positively associated with sex-related alcohol expectancies (b = 10.94, β = .30, p=.002), which were significantly associated with more problem drinking (b = .05, β = .34, p< .001). The indirect effect of lack of premeditation on problem drinking through sex-related alcohol expectancies was significant (point estimate = .60, Boot SE = .26, 95% Boot CI: .21, 1.26). The direct effect of lack of premeditation on problem drinking was also significant (b = 1.36, β = .23,p=.012), suggesting that this relationship is partially explained by sex-related alcohol expectancies.

Sex-related alcohol expectancies and alcohol at sex

Positive sex-related alcohol expectancies significantly predicted more alcohol use at sex (b = .03, β = .46, p<.001), which predicted problem drinking when controlling for the effect of sex-related alcohol expectancies (b = 1.74, β = .64, p<.001). The indirect effect of sex-related alcohol expectancies on problem drinking was significant (point estimate =.05, Boot SE = .01, 95% Boot CI: .02, .07), but the direct effect was not (b = .02, β = .12, ns), indicating that this relationship is fully explained by alcohol at sex.

Full model

We examined the full indirect effects model to examine whether sex-related alcohol expectancies and alcohol use at sex would serially mediate the relationship between the dimensions of impulsivity and problem drinking. Again, based on the preliminary regression results, urgency was excluded from these analyses.

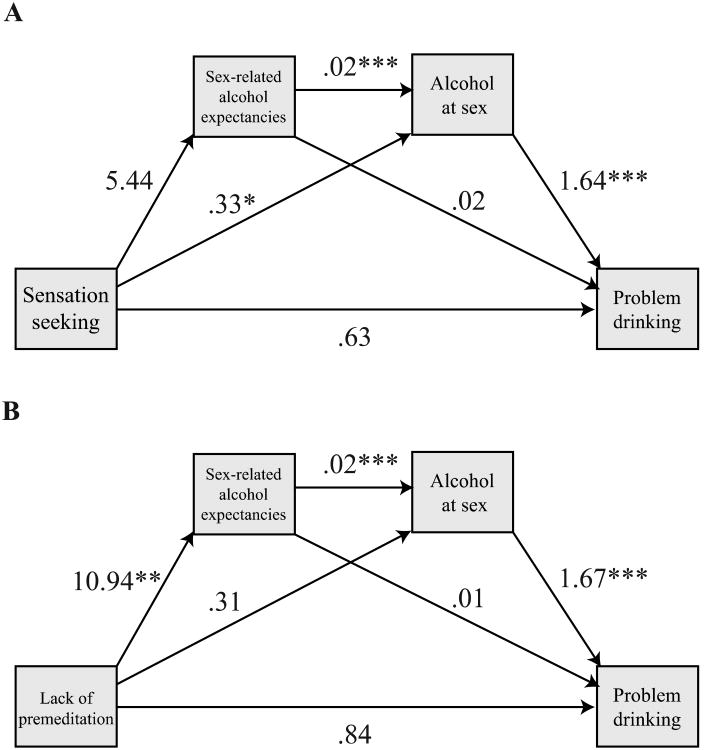

The relationship between sensation seeking and problem drinking was serially mediated by sex-related alcohol expectancies and alcohol use at sex (point estimate = .22, Boot SE = .15, 95% Boot CI: .01, .63). The direct effect of sensation seeking was not significant (b = .63, β = .14, ns), suggesting that the two mediators fully explain its relationship with problem drinking (see Figure 1 for all path coefficients). The total effect of sensation seeking explained 15.17% of variance in problem drinking.

Figure 1.

The relationship between impulsivity ([A] sensation seeking and [B] lack of premeditation) and problem drinking is serially mediated by sex-related alcohol expectancies and alcohol use at sex among college students (N = 101)

Note. Age and gender were included in the models as covariates but are not depicted. Including covariates, the models explained 54.20% (A) and 54.35% (B) of the variance in problem drinking.

*p< .05, **p< .01, ***p< .001

The relationship between lack of premeditation and problem drinking was also mediated by sex-related alcohol expectancies and alcohol use at sex, respectively (point estimate = .44, Boot SE = .19, 95% Boot CI: .17, .95). The direct effect of lack of premeditation on problem drinking trended towards significance (b = .84, β = .14, p= .051), suggesting that this relationship was partially explained by sex-related alcohol expectancies and alcohol use at sex (see Figure 1). The total effect of lack of premeditation explained 16.16% of the variance in problem drinking

Discussion

The current study aimed to expand the literature on the relationship between impulsivity and problematic college drinking, and explore the role of sex-related alcohol expectancies in this relationship. Specifically, we examined these factors in the context of the AP Model, expecting that college students with higher impulsivity would be more likely to endorse positive sex-related alcohol expectancies, and in turn, would be more likely to drink proximal to sexual intercourse. Based on previous research suggesting that sex-related alcohol expectancies also mediate the relationship between impulsivity and problem drinking (Dir et al., 2013), we expected that the pathway from impulsivity to alcohol use at sex would subsequently contribute to greater problem drinking in general.

Of the four dimensions of impulsivity explored (the urgency traits were collapsed due to high collinearity), we hypothesized that sensation seeking, lack of premeditation, and urgency would predict unique variance in problem drinking among college students. It was hypothesized that lack of perseverance would not be associated with problem drinking. This hypothesis was partially supported: consistent with previous research, sensation seeking and lack of premeditation significantly predicted greater problem drinking (Fischer & Smith, 2008; Miller et al., 2003), but lack of perseverance did not. Contrary to our hypothesis, urgency did not contribute unique variance when all four impulsivity dimensions were considered. Although this finding is inconsistent with previous literature (Cyders et al., 2009; LaBrie et al., 2014; Settles et al., 2010), it may be accounted for by the drinking patterns of our sample. Though the AUDIT-C measures drinking frequency, drinking quantity, and frequency of binge drinking, scores in our sample were primarily driven by drinking frequency. Approximately half of the sample reporting at least 2-3 drinking occasions per week, whereas only 22.8% reported consuming five or more drinks on a typical drinking occasion and 24.7% reported binge drinking on a monthly basis or more frequently. Thus, as previous literature has found urgency to be most strongly associated with drinking quantity and drinking-related problems, it may have been less predictive of problem drinking in the present study. Further, sensation seeking and lack of premeditation, the two facets of impulsivity that are most consistently associated with drinking frequency (Magid & Colder, 2007; Miller et al., 2003; Shin et al., 2012), were the only two facets significantly related to problem drinking in our sample and the two significant predictors in our model.

Our second hypothesis, that sex-related alcohol expectancies would mediate the effect of impulsivity on problem drinking, was supported with lack of premeditation and sensation seeking. These results correspond with recent findings (Dir et al., 2013) indicating that impulsivity affects problem drinking, at least in part, through positive expectations about the effects of alcohol on sex. Further, findings support the AP Model of drinking risk with sex-related alcohol expectancies, suggesting that those higher on the sensation seeking and lack of premeditation traits are more likely to hold positive beliefs about the effects of alcohol on one's sexual experience, in turn contributing to greater alcohol consumption among these individuals.

Moreover, findings from our third hypothesis, which stated that the relationship between sex-related alcohol expectancies and problem drinking would be mediated by alcohol use at sex, clarified that the effect of sex-related alcohol expectancies on problem drinking was fully explained by alcohol use at sex. This finding supports evidence that positive sex-related alcohol expectancies are most predictive of drinking in sexual situations (Dermen & Cooper, 1994b; Leigh, 1990), and suggests that drinking in sexual situations in turn contributes to patterns of problem drinking. As hypothesized, when these study variables were examined together, the relationship between impulsivity and problem drinking was explained by greater sex-related alcohol expectancies and more alcohol use at sex, respectively, indicating a unique pathway through which impulsivity influences problem drinking.

Previous research has supported the AP Model prospectively among college students, demonstrating that dispositional impulsivity predicts increases in positive alcohol expectancies, which predict subsequent increases in alcohol consumption (Darkes et al., 2004; Settles et al., 2010). However, those studies combined positive alcohol expectancies regarding social, physical and sexual enhancement. The current findings support the AP Model with expectancies specifically related to sexual enhancement and implicates a pathway to problem drinking through alcohol use proximal to sex. The medium effect size of alcohol use at sex on problem drinking suggests that students who more frequently drink alcohol before sex are also more likely to engage in heavy drinking in general. Although heavy alcohol use and risky sexual behavior are thought to increase during college independent of previous behavior (Fromme, Corbin, & Kruse, 2008), the current study suggests that sex-related alcohol expectancies may underlie both of these behaviors through the use of alcohol at sex, implicating this risk behavior in the increasing rates of morbidity and mortality among college students (Hingson et al., 2009),

These findings should be interpreted with consideration of the study's limitations. First, though hypotheses on the pathway through which impulsivity influences problem drinking were based on previous literature and theory, the study used a cross-sectional design, so causal relationships between the study variables could not be confirmed. Future research exploring the mediating role of sex-related alcohol expectancies prospectively is necessary to confirm the suggested causal pathways. A second limitation is the sample size, which possibly produced limited power to detect important gender differences in problem drinking that has been found in previous literature (see Ham & Hope, 2003 for review). Additionally, the small sample size likely contributed to the large confidence intervals observed around the estimates of the indirect effects. Although bias-corrected bootstrapping is recommended as the most powerful and reasonable method of examining indirect effects (e.g., Preacher & Hayes, 2008; MacKinnon, Lockwood, & Williams, 2004), bias-corrected bootstrap methods have been shown to be more susceptible to Type I error (MacKinnon et al., 2004). Third, although the current study is novel in that an indirect pathway from impulsivity to problem drinking through sex-related alcohol expectancies and alcohol use at sex was found, it is unclear how much of the problem drinking occurred outside of alcohol use at sex as a causal relationship cannot be inferred. It is also possible that for some individuals, alcohol use may be used exclusively within a sexual context, whereas for others, alcohol use at sex may increase risk for problem drinking independent of alcohol use at sex. The AUDIT-C asks respondents about general consumption patterns; thus, we cannot determine how much drinking occurred independent of sex within our sample. This differentiation in drinking patterns should be further investigated in future research. Finally, the use of a college student, majority female and majority European American sample may limit the generalizability of the results. However, because alcohol use tends to increase in late adolescence and early adulthood (Dawson, Grant, Stinson, & Chou, 2004; Hingson et al., 2002; Johnston et al., 2015; White et al., 2006) and is more prevalent among European American populations compared to most ethnic minority groups (Bachman et al., 1991; Chen & Jacobson, 2012; Johnston, O'Malley, Bachman, Schulenberg, & Miech, 2014; Poulin, 1991), this is a relevant sample among which to explore drinking behaviors.

The current study explored the indirect effect of sex-related alcohol expectancies and alcohol use at sex on the relationship between impulsivity and problem drinking among college students. Findings indicated that lack of premeditation and sensation seeking were the two impulsivity dimensions most strongly associated with problem drinking and that sex related-alcohol expectancies partially explain this relationship by working through the use of alcohol before or during sexual intercourse. Considering high, enduring rates of college drinking and the strong association between impulsivity and college drinking, future research should continue to explore mediating factors that contribute to problem drinking among this population of young adults. Moreover, interventions targeting these dimensions of impulsivity should be tested among college students to mitigate risk for negative outcomes associated with drinking proximal to sexual intercourse, including problem drinking, risky sexual behavior and sexual assault (ACHA, 2016; Caldeira et al., 2010; Connor, Gray, & Kypri, 2010; Neal & Fromme, 2007). For example, interventions such as cognitive mediation training and highly stimulating media messages that suggest alternative ways to pursue stimulation have been suggested to manage risk associated with lack of premeditation and sensation seeking, respectively (Zapolski et al., 2010).

The current study also suggests that interventions focusing on changing or managing expectancies may also be effective in reducing drinking proximal to sexual intercourse, which may contribute to reductions in problem drinking among college students. Expectancy challenge techniques, which highlight that experiences associated with alcohol use have more to do with alcohol expectancies rather than the amount of alcohol consumed, have been efficacious for not only reducing positive alcohol expectancies, but also alcohol use and frequency of heavy drinking (Darkes & Goldman, 1993; Scott-Sheldon, Terry, Carey, Garey, & Carey, 2012). As positive sex-related alcohol expectancies are associated with problem drinking through alcohol use at sex, challenging such expectancies could be an effective strategy to prevent and reduce problem drinking and risky sexual behavior that is associated with the use of alcohol use at sex (Cooper, 2002; Hendershot et al., 2007; Howells & Orcutt, 2014; Scott-Sheldon, Carey, & Carey, 2010). Future research should continue to investigate this pathway from impulsivity to problem drinking in order to prevent drinking-related problems including risky sexual behavior and sexual assault among college students.

Acknowledgments

Preparation of this article was made possible with support from Grant Numbers KL2TR001106 and UL1TR001108 (A. Shekhar, PI) from the National Institutes of Health, National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, Clinical and Translational Sciences Award to Tamika Zapolski.

Glossary

- Positive urgency

The dispositional tendency to act rashly in response to intense positive emotion

- Negative urgency

The dispositional tendency to act rashly in response to intense positive emotion

- Sensation seeking

The dispositional tendency to seek out novel or thrilling situations or stimulation

- Lack of premeditation

The dispositional tendency to act without forethought, planning or consideration of potential consequences

- Lack of perseverance

The dispositional inability to tolerate boredom or remain focused on a task

- Sex-related alcohol expectancies

Beliefs about the personal consequences of drinking on one's sexual experience

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

Contributor Information

Devin E. Banks, Indiana University–Purdue University Indianapolis

Tamika C. B. Zapolski, Indiana University–Purdue University Indianapolis

References

- American College Health Association. Hanover, MD: American College Health Association; 2016. American College Health Association-National College Health Assessment II: Undergraduate Students Reference Group Executive Summary Fall 2015. Retrieved June 12, 2016 from http://www.acha-ncha.org/docs/NCHA-II_FALL_2015_UNDERGRADUATE_REFERENCE_GROUP_EXECUTIVE_SUMMARY.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Adams ZW, Kaiser AJ, Lynam DR, Charnigo RJ, Milich R. Drinking motives as mediators of the impulsivity-substance use relation: Pathways for negative urgency, lack of premeditation, and sensation seeking. Addictive Behaviors. 2012;37(7):848–855. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachman JG, Wallace JM, O'Malley PM, Johnston LD, Kurth CL, Neighbors HW. Racial/ethnic differences in smoking, drinking, and illicit drug use among American high school seniors, 1976-1989. American Journal of Public Health. 1991;81(3):372–377. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.81.3.372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer JS. Student factors: understanding individual variation in college drinking. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, Supplement. 2002;14:40–53. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birthrong A, Latzman RD. Aspects of impulsivity are differentially associated with risky sexual behaviors. Personality and Individual Differences. 2014;57:8–13. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2013.09.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brown JL, Vanable PA. Alcohol use, partner type, and risky sexual behavior among college students: Findings from an event-level study. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32(12):2940–2952. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bush K, Kivlahan DR, McDonell MB, Fihn SD, Bradley KA. The AUDIT alcohol consumption questions (AUDIT-C): an effective brief screening test for problem drinking. Archives of Internal Medicine. 1998;158(16):1789–1795. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.16.1789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldeira KM, Arria AM, O'Grady KE, Zarate EM, Vincent KB, Wish ED. Prospective associations between alcohol and drug consumption and risky sex among female college students. Journal of Alcohol and Drug Education. 2009;53(2) [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey KB. Alcohol-related expectancies predict quantity and frequency of heavy drinking among college students. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 1995;9(4):236–241. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.9.4.236. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Disease Control (CDC; Vital signs: binge drinking prevalence, frequency, and intensity among adults—United States, 2010. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2012;61(1):14–19. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6101a4.htm. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen P, Jacobson KC. Developmental trajectories of substance use from early adolescence to young adulthood: Gender and racial/ethnic differences. The Journal of Adolescent Health. 2012;50(2):154–163. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connor J, Gray A, Kypri K. Drinking history, current drinking and problematic sexual experiences among university students. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health. 2010;34(5):487–494. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-6405.2010.00595.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML. Alcohol use and risky sexual behavior among college students and youth: Evaluating the evidence. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2002;14:101–117. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtney KE, Polich J. Binge drinking in young adults: Data, definitions, and determinants. Psychological Bulletin. 2009;135(1):142–156. doi: 10.1037/a0014414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coskunpinar A, Dir AL, Cyders MA. Multidimensionality in Impulsivity and Alcohol Use: A Meta-Analysis using the UPPS Model of Impulsivity. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research. 2013;37(9):1441–1450. doi: 10.1111/acer.12131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curcio AL, George AM. Selected impulsivity facets with alcohol use/problems: The mediating role of drinking motives. Addictive Behaviors. 2011;36:959–964. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyders MA, Flory K, Rainer S, Smith GT. The role of personality dispositions to risky behavior in predicting first year college drinking. Addiction. 2009;104(2):193–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02434.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyders MA, Smith GT. Mood-based rash action and its components: Positive and negative urgency. Personality and Individual Differences. 2007;43(4):839–850. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2007.02.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cyders MA, Smith GT. Emotion-based dispositions to rash action: Positive and negative urgency. Psychological Bulletin. 2008;134(6):807–828. doi: 10.1037/a0013341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darkes J, Goldman MS. Expectancy challenge and drinking reduction: experimental evidence for a mediational process. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1993;61(2):344–353. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.61.2.344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darkes J, Greenbaum PE, Goldman MS. Alcohol expectancy mediation of biopsychosocial risk: Complex patterns of mediation. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2004;12(1):27–38. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.12.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson DA, Grant BF, Stinson FS, Chou PS. Another look at heavy episodic drinking and alcohol use disorders among college and noncollege youth. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2004;65(4):477–488. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2004.65.477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson DA, Grant BF, Stinson FS, Zhou Y. Effectiveness of the derived alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT-C) In screening for alcohol use disorders and risk drinking in the US general population. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2005;29(5):844–854. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000164374.32229.a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Depue RA, Collins PF. Neurobiology of the structure of personality: Dopamine, facilitation of incentive motivation, and extraversion. Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 1999;22(03):491–517. doi: 10.1017/s0140525×99002046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dermen KH, Cooper ML. Sex-related alcohol expectancies among adolescents: I. Scale development. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 1994a;8(3):152–160. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.8.3.152. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dermen KH, Cooper ML. Sex-related alcohol expectancies among adolescents: II. Prediction of drinking in social and sexual situations. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 1994b;8(3):161–168. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.8.3.161. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dir AL, Cyders MA, Coskunpinar A. From the bar to the bed via mobile phone: A first test of the role of problematic alcohol use, sexting, and impulsivity-related traits in sexual hookups. Computers in Human Behavior. 2013;29(4):1664–1670. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2013.01.039. [Google Scholar]

- Enoch MA, Goldman D. Problem drinking and alcoholism: diagnosis and treatment. American Family Physician. 2002;65(3):441–454. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer S, Smith GT. Binge eating, problem drinking, and pathological gambling: Linking behavior to shared traits and social learning. Personality and individual Differences. 2008;44(4):789–800. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2007.10.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Finn PR, Sharkansky EJ, Brandt KM, Turcotte N. The effects of familial risk, personality, and expectancies on alcohol use and abuse. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2000;109(1):122. doi: 10.1037/0021-843x.109.1.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fromme K, Corbin WR, Kruse MI. Behavioral risks during the transition from high school to college. Developmental Psychology. 2008;44(5):1497–1504. doi: 10.1037/a0012614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ham LS, Hope DA. College students and problematic drinking: A review of the literature. Clinical Psychology Review. 2003;23(5):719–759. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(03)00071-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York: Guilford Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hendershot CS, Stoner SA, George WH, Norris J. Alcohol use, expectancies, and sexual sensation seeking as correlates of HIV risk behavior in heterosexual young adults. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2007;21(3):365–372. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.21.3.365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hingson RW, Heeren T, Zakocs RC, Kopstein A, Wechsler H. Magnitude of alcohol-related mortality and morbidity among US college students ages 18-24. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;63(2):136–144. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2002.63.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hingson RW, Zha W, Weitzman ER. Magnitude of and trends in alcohol-related mortality and morbidity among U.S. college students ages 18-24, 1998-2005. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs Supplement. 2009;16:12–20. doi: 10.15288/jsads.2009.s16.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howells NL, Orcutt HK. Diary study of sexual risk taking, alcohol use, and strategies for reducing negative affect in female college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2014;75(3):399. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2014.75.399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoyle RH, Fejfar MC, Miller JD. Personality and sexual risk taking: A quantitative review. Journal of Personality. 2000;68(6):1203–1231. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.00132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O'Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE, Miech RA. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2013: volume I, Secondary school students. 2014 Retrieved from: http://www.monitoringthefuture.org/pubs/monographs/mtf-vol1_2013.pdf.

- Johnston LD, O'Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE, Miech RA. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2014: Volume 2, College students and adults ages 19–55. 2015 Retrieved from Ann Arbor: http://www.monitoringthefuture.org//pubs/monographs/mtf-vol2_2014.pdf.

- Kalichman SC, Cain D. A prospective study of sensation seeking and alcohol use as predictors of sexual risk behaviors among men and women receiving sexually transmitted infection clinic services. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2004;18(4):367–373. doi: 10.1037/0893-164x.18.4.367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly TM, Donovan JE, Chung T, Bukstein OG, Cornelius JR. Brief screens for detecting alcohol use disorder among 18-20 year old young adults in emergency departments: Comparing AUDIT-C, CRAFFT, RAPS4-QF, FAST, RUFT-Cut, and DSM-IV 2-Item Scale. Addictive Behaviors. 2009;34(8):668–674. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.03.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaBrie JW, Kenney SR, Napper LE, Miller K. Impulsivity and alcohol-related risk among college students: Examining urgency, sensation seeking and the moderating influence of beliefs about alcohol's role in the college experience. Addictive Behaviors. 2014;39(1):159–164. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.09.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latzman RD, Chan WY, Shishido Y. Impulsivity moderates the association between racial discrimination and alcohol problems. Addictive Behaviors. 2013;38(12):2898–2904. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latzman RD, Vaidya JG. Common and distinct associations between aggression and alcohol problems with trait disinhibition. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2013;35(2):186–196. doi: 10.1007/s10862-012-9330-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lau-Barraco C, Dunn ME. Evaluation of a single-session expectancy challenge intervention to reduce alcohol use among college students. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2008;22(2):168. doi: 10.1037/0893-164x.22.2.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leigh BC. The relationship of sex-related alcohol expectancies to alcohol consumption and sexual behavior. British Journal of Addiction. 1990;85(7):919–928. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1990.tb03722.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynam DR, Miller JD. Personality pathways to impulsive behavior and their relations to deviance: Results from three samples. Journal of Quantitative Criminology. 2004;20(4):319–341. doi: 10.1007/s10940-004-5867-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lynam DR, Smith GT, Whiteside SP, Cyders MA. The UPPS-P: Assessing five personality pathways to impulsive behavior. Technical Report 2006 [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Williams J. Confidence limits for the indirect effect: Distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2004;39(1):99–128. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr3901_4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magid V, Colder CR. The UPPS Impulsive Behavior Scale: Factor structure and associations with college drinking. Personality and Individual Differences. 2007;43(7):1927–1937. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2007.06.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Magid V, MacLean MG, Colder CR. Differentiating between sensation seeking and impulsivity through their mediated relations with alcohol use and problems. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32(10):2046–2061. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller J, Flory K, Lynam D, Leukefeld C. A test of the four-factor model of impulsivity-related traits. Personality and Individual Differences. 2003;34(8):1403–1418. doi: 10.1016/S0191-8869(02)00122-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Neal DJ, Fromme K. Event-level covariation of alcohol intoxication and behavioral risks during the first year of college. Journal Of Consulting And Clinical Psychology. 2007;75(2):294–306. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.2.294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick ME, Maggs JL. Does drinking lead to sex? Daily alcohol–sex behaviors and expectancies among college students. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2009;23(3):472–481. doi: 10.1037/a0016097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poulin JE. Racial differences in the use of drugs and alcohol among low income youth and young adults. Journal of Sociology and Social Welfare. 1991;18:159. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers. 2004;36(4):717–731. doi: 10.3758/bf03206553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods. 2008;40(3):879–891. doi: 10.3758/BRM.40.3.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, de la Fuente JR, Grant M. Development of the alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT): WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption-II. Addiction. 1993;88(6):791–804. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott-Sheldon LAJ, Carey MP, Carey KB. Alcohol and risky sexual behavior among heavy drinking college students. AIDS and Behavior. 2010;14(4):845–853. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9426-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott-Sheldon LAJ, Terry DL, Carey KB, Garey L, Carey MP. Efficacy of expectancy challenge interventions to reduce college student drinking: A meta-analytic review. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2012;26(3):393–405. doi: 10.1037/a0027565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Settles RE, Fischer S, Cyders MA, Combs JL, Gunn RL, Smith GT. Negative urgency: A personality predictor of externalizing behavior characterized by neuroticism, low conscientiousness, and disagreeableness. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2012;121(1):160–172. doi: 10.1037/a0024948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Settles RF, Cyders MA, Smith GT. Longitudinal validation of the acquired preparedness model of drinking risk. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2010;24(2):198–208. doi: 10.1037/a0017631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin SH, Hong HG, Jeon SM. Personality and alcohol use: The role of impulsivity. Addictive Behaviors. 2012;37(1):102–107. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith GT, Anderson KG. Personality and learning factors combine to create risk for adolescent problem drinking. In: Monti PM, Colby SM, O'Leary T, editors. Adolescents, alcohol, and substance abuse: Reaching teens through brief interventions. New York: Guilford; 2001. pp. 109–141. [Google Scholar]

- Smith GT, Fischer S, Cyders MA, Annus AM, Spillane NS, McCarthy DM. On the validity and utility of discriminating among impulsivity-like traits. Assessment. 2007;14(2):155–170. doi: 10.1177/1073191106295527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith GT, Guller L, Zapolski TC. A comparison of two models of urgency: Urgency predicts both rash action and depression in youth. Clinical Psychological Science. 2013;1:266–275. doi: 10.1177/2167702612470647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wardell JD, Read JP, Colder CR, Merrill JE. Positive alcohol expectancies mediate the influence of the behavioral activation system on alcohol use: A prospective path analysis. Addictive Behaviors. 2012;37(4):435–443. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White HR, Fleming CB, Catalano RF, Bailey JA. Prospective associations among alcohol use-related sexual enhancement expectancies, sex after alcohol use, and casual sex. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2009;23(4):702–707. doi: 10.1037/a0016630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White HR, McMorris BJ, Catalano RF, Fleming CB, Haggerty KP, Abbott RD. Increases in alcohol and marijuana use during the transition out of high school into emerging adulthood: The effects of leaving home, going to college, and high school protective factors. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2006;67(6):810–822. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteside SP, Lynam DR. The five factor model and impulsivity: Using a structural model of personality to understand impulsivity. Personality and Individual Differences. 2001;30(4):669–689. doi: 10.1016/s0191-8869(00)00064-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zapolski TCB, Settles RE, Cyders MA, Smith GT. Borderline personality disorder, bulimia nervosa, antisocial personality disorder, ADHD, substance use: Common threads, common treatment needs, and the nature of impulsivity. Independent Practitioner. 2010;30(1):20–23. doi: 10.1037/e695012007-001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuckerman M. Sensation Seeking (Psychology Revivals): Beyond the Optimal Level of Arousal. New York: Psychology Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]