Abstract

Background

Thyroid nodules (TNs) are common thyroid lesions in older population. Few studies have focused on the prevalence of TNs and their relationship to lifestyle characteristics and dietary habits in centenarians. The current study aimed at determining the prevalence of TNs in Chinese centenarians by using high-resolution ultrasound (US) equipment and at investigating its relationship to lifestyle characteristics and dietary habits.

Participants and methods

The current study was part of the China Hainan Centenarian Cohort Study that was conducted in Hainan, an iodine-sufficient region in People’s Republic of China. A total of 874 permanent residents aged ≥100 years (mean age =102.8±2.8 years) without any missing data were included in the analysis.

Results

Among the participants, 649 of them were detected at least one TN under the US examinations. The overall prevalence rate of TNs was 74.3%. The prevalence of TNs was higher in participants who were women, had hypertension, had diabetes, and were underweight compared with their counterparts. Multivariate logistic regression analyses showed that being female, hypertensive, and diabetic; betel quid consumption; and red meat consumption were independent risk factors, while being underweight and nut consumption were independent protective factors for TNs.

Conclusion

Our findings indicate that the presence of TNs was highly prevalent in Chinese centenarians, particularly in women. In addition to gender, having hypertension, having diabetes, and being underweight, the presence of TNs was independently associated with betel quid, red meat, and nut consumption. Further prospective studies are warranted to verify these associations in populations from different age strata, races, cultures, and iodine supplementation.

Keywords: thyroid nodules, ultrasound, lifestyle, dietary, betel quid, red meat, nut, centenarians

Introduction

Thyroid nodules (TNs) are common thyroid lesions in older population. High-resolution ultrasonography has made the detection of asymptomatic and nonpalpable TNs possible.1 The prevalence of TNs detected by high-resolution ultrasonography was 19%–68% in randomly selected individuals, with annually increasing trends worldwide.2,3 The clinical importance of TN detection rests with the need to exclude thyroid cancer, which occurs in 5%–15% of TN cases.1,4 A recent study reported that the occurrence of TNs increased as people age, with a prevalence of 74% in a community-based sample of Chinese senior adults.5 However, the prevalence of this lesion in centenarians remained understudied. Considering the issues mentioned above, there is a need to specifically determine the prevalence of TNs in late life, particularly in centenarians.

The high prevalence rate of TNs was partly due to the widespread application of high-resolution ultrasound (US) and early diagnosis. In addition, recent studies also proposed that several risk factors could be attributed to TNs. Among these risk factors, some factors were nonmodifiable, such as age, gender, and the history of irradiation exposure, while others were modifiable, including iodine intake, smoking, alcohol drinking, obesity, and metabolic syndrome.5–8 However, some other modifiable factors, including passive smoking, red meat consumption, and nut intake, which were related to lifestyle and dietary habits, were seldom regarded in TN studies. Therefore, further investigations into the relationship between the prevalence of TNs and potential lifestyle characteristics, as well as dietary habits, are of epidemiological and clinical significance.

The aims of this study were to determine the prevalence of TNs in Chinese centenarians and to investigate their relationship to lifestyle characteristics and dietary habits. The data from the China Hainan Centenarian Cohort Study (CHCCS) were used in this study. It was hypothesized that 1) TNs were highly prevalent in centenarians; and 2) the occurrence of TNs was correlated to several lifestyle characteristics and dietary habits such as betel quid consumption, red meat consumption, and nut intake.

Participants and methods

Study population

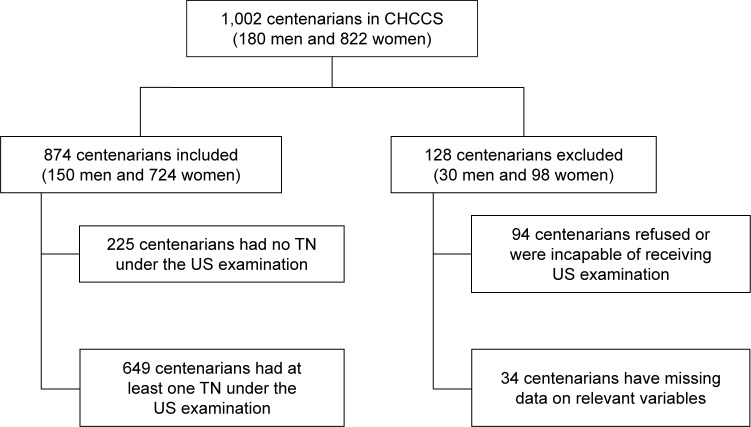

The sample for this study was obtained from the CHCCS, one of the largest centenarian health interdisciplinary studies conducted in People’s Republic of China from June 2014 to December 2016. Details of this study have been described elsewhere.9 The CHCCS is located in Hainan province, which is both a longevity area, with the highest density of centenarians in People’s Republic of China, and an iodine-sufficient region with abundant seafood provided.10 Based on the National Civil Registry, 1,002 centenarians were recruited in the present study. Age was ascertained from national identification cards. There were 874 centenarians, including 150 men and 724 women without any missing data in the final analysis (Figure 1). The present study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Hainan branch of Chinese People’s Liberation Army General Hospital (Number: 301hn11201601; Sanya, Hainan, People’s Republic of China). The participants were informed about the research contents and signed the informed consent form.

Figure 1.

Diagram of the study population.

Abbreviations: CHCCS, China Hainan Centenarian Cohort Study; TN, thyroid nodule; US, ultrasound.

Thyroid US procedure

The US scans of the thyroid glands and neck areas were operated using standard procedure by sonographers who were board-certified with >3 years of experience in thyroid US. A TN is a discrete lesion within the thyroid gland that is radiologically distinct from the surrounding thyroid parenchyma.4 The US equipment used in the study was Philips CX50 (Philips Medical Systems, Andover, MA, USA) instrument with 3–12-MHz linear array transducers. All the US examinations complied with the same protocol for thyroid scanning. US images were stored in separate hard drives and separately reviewed by two radiologists with 5 and 12 years of experience. The participants were dichotomized into TN+ (have at least one nodule) and TN− (normal thyroid gland without nodule).

Demographic and health-related variables

Home interviews were conducted to collect data on the demographic details (age, gender, ethnicity, level of education, and work type before retirement). Health examinations were performed, and blood samples were obtained from each participant. Ethnicity was categorized into Han and non-Han. Given that the majority of centenarians received no education, the participants were categorized into illiterate and primary school or above. Considering that only 2.7% of centenarians were doing manual works such as farming before retirement, work types before retirement were classified as heavy manual work, moderate manual work, and intellectual work. Health-related variables included body mass index (BMI), hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, anemia, and self-rated health. Height and weight were measured according to the standard procedures, and BMI was calculated as the weight in kilograms divided by the square height in meters. BMI was dichotomized into underweight (<18.5 kg/m2) and normal or overweight (≥18.5 kg/m2) according to the World Health Organization (WHO) criteria.11 Systolic blood pressure (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) were measured two times consecutively, with at least 1-minute intervals between the measurements, and the reported blood pressures were the average of the two measurements. Samples of venous blood were obtained from the centenarians in a seated position and transported in cold storage (4°C) to the Central Laboratory within 4 hours. Serum concentrations of triglyceride (TG), total cholesterol (TC), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-c), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-c), fasting blood glucose (FBG), and hemoglobin (Hb) were measured using enzymatic assays (Roche Products Ltd., Basel, Switzerland) on a fully automatic biochemical autoanalyzer (COBAS c702; Roche Products Ltd.). The centenarians who had SBP ≥140 mmHg and DBP ≥90 mmHg or who were treated with antihypertensive agents were considered to have hypertension.12 The centenarians who had FBG ≥7.0 mmol/L or who were treated with antidiabetic agents/insulins were considered to have diabetes.13 The centenarians who had TG ≥1.7 mmol/L, TC ≥5.18 mmol/L, LDL-c ≥3.37 mmol/L, HDL-c <1.04 mmol/L or who were treated with lipid-regulating agents were considered to have dyslipidemia.14 Anemia was defined as an Hb level <12 g/dL in women and <13 g/dL in men according to the WHO criteria.15 Self-rated health was defined as the subjective perception of health status and was classified as good, fair, and poor.16

Lifestyle characteristics and dietary habits

Data regarding lifestyle characteristics and dietary habits, including smoking; alcohol drinking; tea drinking; passive smoking; taste preference; and red meat, poultry, seafood, vegetable, fruit, betel quid, egg, milk, and nut consumption, were collected. Habits of smoking, alcohol drinking, and tea drinking were categorized as current, former, and never. Passive smoking was defined as involuntary inhalation of smoke by persons other than the intended “active” smoker.17 Passive smoking exposure was dichotomized as yes (at least once per week for >1 year) and no.18 Taste preferences were divided into three groups: salty, average, and bland according to the subjective evaluation. Consumption of red meat, poultry, seafood, vegetable, fruit, egg, milk, and nut was categorized into three groups: frequent (≥3 times/week), occasional (<3 times/week), and never. Betel quid generally consists of areca nut, betel leaf, catechu, slaked lime, and often tobacco.19 Given that most of the centenarians were incapable of chewing betel quid in their 100s, this habit was dichotomized as yes (in the present or the past) and no.

Statistical analysis

The data were reported as mean values and standard deviations for normally distributed variables or as median values and corresponding 25th and 75th percentiles for non-normally distributed variables. The counts and percentages were reported for the categorical variables. Differences in the continuous variables were explored using the unpaired Student’s t-test, Mann–Whitney U test, and one-way analysis of variance; χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test was used to compare categorical variables. Multivariate logistic regression analyses were used to determine the independent factors correlated to TNs. All the analyses were carried out by using SPSS software (Version 19.0 for windows, serial number: 5087722; IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). A P-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

General characteristics

A total of 874 individuals aged ≥100 years were included in this study. Mean age of the participants was 102.8±2.8 years. As shown in Table 1, the majority of the participants were female (82.8%), illiterate (90.8%), and of Han ethnicity (87.3%). More than 42% of the study participants did heavy manual work before retirement. Fifty-three percent of the study participants were underweight. The prevalence of chronic conditions was 67.3%, 10.2%, and 23.7% for hypertension, diabetes, and dyslipidemia, respectively. About one third of the study participants were anemic. The proportions of self-rated health were 23.6%, 60.3%, and 16.1% for good, fair, and poor, respectively. None of the participants declared that they had iodine supplementation in the present and the past. Besides, there was no radiation exposure before and after retirement of the participants.

Table 1.

General characteristics of the participants by thyroid nodules

| Variables | Total n=874 |

TN+ n=649 |

TN− n=225 |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 102.8±2.8 | 102.9±2.8 | 102.8±2.7 | 0.724 |

| Women, % | 82.8 | 86.6 | 72.0 | <0.001 |

| Illiterate, % | 90.8 | 91.4 | 89.3 | 0.361 |

| Han ethnic, % | 87.3 | 87.2 | 87.6 | 0.894 |

| Heavy manual work, % | 42.7 | 41.9 | 44.9 | 0.436 |

| Underweight, % | 53.0 | 51.5 | 57.3 | 0.128 |

| Hypertension, % | 67.3 | 69.8 | 60.0 | 0.007 |

| Diabetes, % | 10.2 | 11.6 | 6.2 | 0.023 |

| Dyslipidemia, % | 23.7 | 22.8 | 26.2 | 0.299 |

| Anemia, % | 32.0 | 33.3 | 28.4 | 0.180 |

| Self-rated health, % | 0.190 | |||

| Good | 23.6 | 24.8 | 20.0 | |

| Fair | 60.3 | 58.6 | 65.3 | |

| Poor | 16.1 | 16.6 | 14.7 |

Notes: TN+, participants with at least one thyroid nodule under the ultrasound examinations; TN−, participants without thyroid nodule.

Abbreviation: TN, thyroid nodule.

Prevalence of TNs

Among the 874 centenarians interviewed, 649 centenarians had at least one detected TN under the US procedure. The overall prevalence rate of TNs was 74.3% (Table 1). Female gender was more frequent in subjects who had TNs than in those who did not have TNs (86.6% vs 72.0%; P<0.001). In addition to gender, the comparison of age, level of education, ethnicity, and work type before retirement in the participants with or without TNs showed insignificant variations. Figure S1 shows the US images of the TNs. When examining the health-related factors, the prevalence of TNs was significantly more common among those who had hypertension and diabetes (all P<0.05). Proportions of underweight and dyslipidemia were higher in participants who had TNs than in those who did not have TNs, but with no statistical significance. The patterns of self-rated health between the participants with and without TNs were not significantly different.

Analyses of TNs with lifestyle characteristics and dietary habits

Comparison analyses on lifestyle and dietary variables between the participants with and without TNs were performed (Table 2). The prevalence of betel quid consumption in participants who had TNs was significantly higher than in those who had no TN (6.9% vs 2.7%; P<0.05). For the other factors regarding lifestyle and dietary habits, no significant variation was found between the participants with and without TNs.

Table 2.

Lifestyle characteristics and dietary habits of the participants by thyroid nodules

| Variables | Total n=874 |

TN+ n=649 |

TN− n=225 |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Smoking, % | 0.373 | |||

| Current | 5.9 | 5.4 | 7.6 | |

| Former | 4.9 | 4.6 | 5.8 | |

| Never | 89.1 | 90.0 | 86.7 | |

| Alcohol drinking, % | 0.865 | |||

| Current | 11.9 | 11.9 | 12.0 | |

| Former | 5.9 | 5.7 | 6.7 | |

| Never | 82.2 | 82.4 | 81.3 | |

| Tea drinking, % | 0.397 | |||

| Frequent | 5.5 | 6.0 | 4.0 | |

| Occasional | 7.2 | 7.6 | 6.2 | |

| Never | 87.3 | 86.4 | 89.8 | |

| Passive smoking, % | 0.739 | |||

| Yes | 44.5 | 44.8 | 43.6 | |

| No | 55.5 | 55.2 | 56.4 | |

| Taste preference, % | 0.647 | |||

| Salty | 13.8 | 14.5 | 12.0 | |

| Average | 19.3 | 19.3 | 19.6 | |

| Bland | 66.8 | 66.3 | 68.4 | |

| Red meat consumption, % | 0.125 | |||

| Frequent | 77.5 | 77.5 | 77.3 | |

| Occasional | 17.7 | 18.5 | 15.6 | |

| Never | 4.8 | 4.0 | 7.1 | |

| Poultry consumption, % | 0.850 | |||

| Frequent | 36.3 | 36.1 | 36.9 | |

| Occasional | 58.6 | 58.6 | 58.7 | |

| Never | 5.1 | 5.4 | 4.4 | |

| Seafood consumption, % | 0.108 | |||

| Frequent | 63.2 | 61.2 | 68.9 | |

| Occasional | 32.2 | 34.1 | 26.7 | |

| Never | 4.7 | 4.8 | 4.4 | |

| Vegetable consumption, % | 0.471 | |||

| Frequent | 92.9 | 92.4 | 94.2 | |

| Occasional | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.7 | |

| Never | 4.6 | 5.1 | 3.1 | |

| Fruit consumption, % | 0.263 | |||

| Frequent | 39.0 | 37.8 | 42.7 | |

| Occasional | 57.0 | 57.8 | 54.7 | |

| Never | 4.0 | 4.5 | 2.7 | |

| Betel quid consumption, % | 0.019 | |||

| Yes | 5.8 | 6.9 | 2.7 | |

| No | 94.2 | 93.1 | 97.3 | |

| Egg consumption, % | 0.515 | |||

| Frequent | 36.3 | 36.4 | 36.0 | |

| Occasional | 54.3 | 53.6 | 56.4 | |

| Never | 9.4 | 10.0 | 7.6 | |

| Milk consumption, % | 0.217 | |||

| Frequent | 28.7 | 29.7 | 25.8 | |

| Occasional | 53.7 | 51.9 | 58.7 | |

| Never | 17.6 | 18.3 | 15.6 | |

| Nut consumption, % | 0.057 | |||

| Frequent | 3.7 | 3.2 | 4.9 | |

| Occasional | 66.5 | 64.9 | 71.1 | |

| Never | 29.9 | 31.9 | 24.0 |

Notes: TN+, participants with at least one thyroid nodule under the ultrasound examinations; TN−, participants without thyroid nodule.

Abbreviation: TN, thyroid nodule.

Table 3 shows the results from the logistic regression analyses. After adjusting for all the related factors, the multivariate model revealed that being female, hypertensive, diabetic, and underweight and consuming betel quid, red meat, and nuts were significantly independent correlates of the presence of TNs. Among these correlates, being female, hypertensive, and diabetic and consumption of betel quid and red meat were risk factors, while being underweight and the consumption of nuts were protective factors for TNs.

Table 3.

Significant factors of TNs by logistic regression analysis

| Variables | β | SE | OR | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 1.21 | 0.27 | 3.36 | 1.97–5.75 | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 0.49 | 0.18 | 1.63 | 1.16–2.30 | 0.005 |

| Diabetes | 0.94 | 0.33 | 2.55 | 1.35–4.83 | 0.004 |

| Underweight | −0.35 | 0.17 | 0.71 | 0.50–0.99 | 0.045 |

| Betel quid consumption | 1.12 | 0.48 | 3.08 | 1.21–7.85 | 0.019 |

| Red meat consumption | |||||

| Frequent | 1.03 | 0.40 | 2.80 | 1.28–6.09 | 0.010 |

| Occasional | 1.23 | 0.44 | 3.43 | 1.45–8.15 | 0.005 |

| Never (reference) | – | – | 1.00 | – | – |

| Nut consumption | |||||

| Frequent | −0.97 | 0.46 | 0.38 | 0.15–0.94 | 0.037 |

| Occasional | −0.58 | 0.23 | 0.56 | 0.35–0.89 | 0.013 |

| Never (reference) | – | – | 1.00 | – | – |

Abbreviations: β, logistic regression coefficient; CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio; SE, standard error; TNs, thyroid nodules.

Discussion

According to the results of the present study, the hypothesis was accepted that the presence of TNs was highly prevalent in Chinese centenarians, particularly in female subjects. In addition, this study also determined that several lifestyle characteristics and dietary habits, including betel quid, red meat, and nut consumption, were independent factors related to the presence of TNs. This study first reported the prevalence of TNs in a population-based sample of centenarians in People’s Republic of China using high-resolution US equipment. Furthermore, this study provided a comprehensive look at the correlation between the prevalence of TNs and lifestyle characteristics as well as diet habits in this population.

The findings of this study showed that the overall prevalence of TNs in centenarians was 74.3%, ranging from 77.6% in women to 58.0% in men. This result indicated a relatively high prevalence of TNs in this exceptionally aged population. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to report the prevalence of TNs among centenarians. According to the previous studies, the prevalence of TNs in the senior population was 73.7% in People’s Republic of China, 54.9% in Korea, and 46.2% in Cameroon.5,20,21 The differences in the prevalence may be due to age, gender, race, culture, dietary patterns, and iodine supplements.7,22,23

The prevalence of TNs was higher in the members of the study population who were female, hypertensive, diabetic, and underweight compared with their counterparts. The gender disparity of the presence of TNs was in accordance with previous studies.5,20,21 Interestingly, this study found a higher odds ratio (OR) of TNs (3.36, 95% confidence interval [CI] =1.97–5.75; P<0.001) in women compared with previous studies, which indicates a potentially increasing trend of gender disparity on TNs with age. Further studies are needed to verify this trend. In addition to gender, other age-related conditions, including hypertension, diabetes, and underweight, were independently correlated to TNs. The associations between TNs and hypertension, as well as diabetes, have been reported in the general population.8,24,25 Previous studies have investigated the relationship between obesity and TNs, indicating that people who were overweight and with a higher BMI were more likely to have TNs compared with those who were not.5,22,26 In centenarians, approximately half of them were underweight (53.0%) and another half were of normal weight (47.0%). Participants who were underweight were less likely to have TNs compared with those who were not (0.71, 95% CI =0.50–0.99; P=0.045). The combination of the previous findings and this finding may suggest that the prevalence of TNs is positively correlated to BMI. Further studies are necessary to elaborate the mechanisms of the association between BMI and TNs.

Considering that only a few modifiable factors associated with TNs have been identified, this study conducted a comprehensive analysis on the relationship between TNs and 14 modifiable factors regarding the lifestyle characteristics and dietary habits.6 The results showed that betel quid intake and red meat consumption were independent risk factors, while nut intake was a protective factor in multivariate logistic analyses. The associations between the prevalence of TNs and smoking, as well as alcohol drinking, were reported in several studies,5–7 yet these associations were not found in the present study. The discrepancy might be explained by differences in iodine status, as the associations seem to be stronger in iodine-deficient regions.27 The betel quid was affirmed as carcinogenic to humans (group 1) by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC).28 There was sufficient evidence that betel quid and the areca nut cause oral and esophageal cancer.19,29 However, no evidence supports that betel quid consumption is associated with TNs or thyroid cancer. One previous study on rat experiments found that arecoline, a carcinogenic element of betel quid, initially stimulated the thyroid and eventually inhibited the activity, and chronic arecoline treatment caused light degenerations of thyroid follicular cells.30 Further studies are required to examine the association between betel quid and TNs.

Red meat was considered as a 2A-level carcinogen by the IARC.31 Previous studies reported that red meat consumption is associated with increased thyroid cancer risk.32,33 To the best of our knowledge, however, there is no study on the association between red meat and TNs. Interestingly, the OR of occasional consumption for red meat was higher compared with frequent consumption in this study. We hypothesize that the subjects who frequently consumed red meat in their 100s have better ingestive function and healthier conditions and thus might have a lower prevalence of TNs. Further studies are necessary to verify this association. The logistic regression analyses also showed that nut intake was a potential protective factor of TNs. In addition, the nut intake was inversely correlated to the prevalence of TNs in this study. The main hypothesis is that nut consumption is inversely associated with BMI and the risk of obesity, and higher BMI was associated with an increased frequency of TNs.34,35 Thus, the prevalence rate of TNs was lower in participants who frequently consumed nuts compared with those who did not. This finding provided a novel insight that frequent nut consumption is associated with lower odds of TNs under US. Further studies on nut consumption and TNs are needed to examine this association cross-sectionally and prospectively.

As there is little knowledge regarding the prevalence of TNs and their correlation to lifestyle characteristics and dietary habits in centenarians, this study addressed the knowledge gap and provided novel insight into this correlation in a population-based sample of Chinese centenarians. In addition, the participants were from iodine-sufficient areas and were free from iodine intake and radiation exposure, which enhances the reliability of the findings by excluding these key confounders. Nevertheless, there are several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, this study was cross-sectionally designed, and thus, causality could not be inferred. Further prospective studies are required to verify the association between lifestyle characteristics and dietary factors and the prevalence of TNs. Second, the indices of thyroid function including thyroid stimulating hormone, triiodothyronine, and thyroxine could not be measured. Hence, potential confounders may remain unrecognized.36 However, this study was conducted in the iodine-sufficient region, and the population in this region was more likely to have a normal range of thyroid function.37

Conclusion

This study determined the prevalence of TNs and its association with lifestyle characteristics and dietary habits in a population-based sample of Chinese centenarians. The results showed that the presence of TNs by US is highly prevalent in centenarians. Female gender, hypertension, diabetes, and underweight were independently associated with the prevalence of TNs. Betel quid intake and red meat consumption were independent lifestyle characteristics and dietary risk factors, while nut intake was a protective factor. Considering that TNs were common among elderly populations, these findings may provide some insights into intervention strategies for TNs. Further prospectively designed population studies and clinical trials are needed to clarify the roles of betel quid, red meat, and nut consumption in TN progression and prevention.

Supplementary material

Ultrasound images of thyroid glands with or without nodule in centenarians. (A) Normal thyroid gland without TN, female, 104 years old; (B) a solitary cystic thyroid nodule in the right lobe of thyroid gland, female, 101 years old; (C) a solitary solid nodule in the right lobe of thyroid gland, female, 103 years old; (D) multiple nodules including solid and mixed mass in the left lobe of thyroid gland, female, 101 years old. Arrows point to the three thyroid nodules.

Abbreviation: TN, thyroid nodule.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the support received from National Key Research and Development Program (2016YFC1303603), National Natural Science Foundation of China (81773502), the Key Research and Development Program of Hainan (ZDYF2016124, ZDYF2016135, ZDYF2016169, and ZDYF2017095), and Medical Research Major Program of Hainan (14A210275). We are grateful to all the staff in the program of CHCCS, and a special thanks to Libo Wang, Yanhui Liu, Ziyu Jiao, Lu Qiao, Qiuyang Li, Jianqiu Hu, Liuqiong Ren, Bingqi Zhang, and Xuexia Shan, for their professional detection and diagnoses of TNs for centenarians in the field work.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Kang HW, No JH, Chung JH, et al. Prevalence, clinical and ultrasonographic characteristics of thyroid incidentalomas. Thyroid. 2004;14(1):29–33. doi: 10.1089/105072504322783812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tan GH, Gharib H. Thyroid incidentalomas: management approaches to nonpalpable nodules discovered incidentally on thyroid imaging. Ann Intern Med. 1997;126(3):226–231. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-126-3-199702010-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guth S, Theune U, Aberle J, Galach A, Bamberger CM. Very high prevalence of thyroid nodules detected by high frequency (13 MHz) ultrasound examination. Eur J Clin Invest. 2009;39(8):699–706. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2009.02162.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haugen BR, Alexander EK, Bible KC, et al. 2015 American Thyroid Association Management Guidelines for Adult Patients with Thyroid Nodules and Differentiated Thyroid Cancer: The American Thyroid Association Guidelines Task Force on Thyroid Nodules and Differentiated Thyroid Cancer. Thyroid. 2016;26(1):1–133. doi: 10.1089/thy.2015.0020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jiang H, Tian Y, Yan W, et al. The prevalence of thyroid nodules and an analysis of related lifestyle factors in Beijing communities. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2016;13(4):442. doi: 10.3390/ijerph13040442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Knudsen N, Bulow I, Laurberg P, Perrild H, Ovesen L, Jorgensen T. Alcohol consumption is associated with reduced prevalence of goitre and solitary thyroid nodules. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2001;55(1):41–46. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2265.2001.01325.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Knudsen N, Laurberg P, Perrild H, Bulow I, Ovesen L, Jorgensen T. Risk factors for goiter and thyroid nodules. Thyroid. 2002;12(10):879–888. doi: 10.1089/105072502761016502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Feng S, Zhang Z, Xu S, et al. The prevalence of thyroid nodules and their association with metabolic syndrome risk factors in a moderate iodine intake area. Metab Syndr Relat Disord. 2017;15(2):93–97. doi: 10.1089/met.2016.0077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.He Y, Zhao Y, Yao Y, et al. Cohort Profile: The China Hainan Centenarian Cohort Study (CHCCS) Int J Epidemiol. 2018 Feb;:28. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyy017. Epub. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hao Z, Liu Y, Li Y, et al. Association between longevity and element levels in food and drinking water of typical Chinese longevity area. J Nutr Health Aging. 2016;20(9):897–903. doi: 10.1007/s12603-016-0690-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.World Health Organization . Obesity: Preventing and Managing the Global Epidemic Report of a WHO Consultation. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2000. pp. 1–252. (World Health Organization Technical Report Series 894). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Committee of Cardio-Cerebro-Vascular Diseases of Gerontological Society of China. Chinese College of Cardiovascular Physicians of Chinese Medical Doctor Association 中国老年学和老年医学学会心 脑血管病专业委员会, 中国医师协会 心血管内科医师分会. 老年高 血压的诊断与治疗中国专家共识(2017版) [Chinese expert consensus on the diagnosis and treatment of hypertension in the elderly (2017)] Zhonghua Nei Ke Za Zhi. 2017;56(11):885–893. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0578-1426.2017.11.024. Chinese. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tong YZ, Tong NW, Teng WP, et al. Consensus on the prevention of type 2 diabetes in Chinese adults. Chin Med J (Engl) 2017;130(5):600–606. doi: 10.4103/0366-6999.200532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Joint Committee for Developing Chinese guidelines on Prevention and Treatment of Dyslipidemia in Adults 中国成人血脂异常防治指南制 订联合委员会. 中国成人血脂异常防治指南 [Chinese guidelines on prevention and treatment of dyslipidemia in adults] Zhonghua Xin Xue Guan Bing Za Zhi. 2007;35(5):390–419. Chinese. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cappellini MD, Motta I. Anemia in clinical practice-definition and classification: does hemoglobin change with aging? Semin Hematol. 2015;52(4):261–269. doi: 10.1053/j.seminhematol.2015.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gama EV, Damian JE, Perez de Molino J, Lopez MR, Lopez Perez M, Gavira Iglesias FJ. Association of individual activities of daily living with self-rated health in older people. Age Ageing. 2000;29(3):267–270. doi: 10.1093/ageing/29.3.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bonita R, Duncan J, Truelsen T, Jackson RT, Beaglehole R. Passive smoking as well as active smoking increases the risk of acute stroke. Tob Control. 1999;8(2):156–160. doi: 10.1136/tc.8.2.156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu Y, Dai M, Bi Y, et al. Active smoking, passive smoking, and risk of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD): a population-based study in China. J Epidemiol. 2013;23(2):115–121. doi: 10.2188/jea.JE20120067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Secretan B, Straif K, Baan R, et al. A review of human carcinogens – Part E: tobacco, areca nut, alcohol, coal smoke, and salted fish. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10(11):1033–1034. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(09)70326-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moon JH, Hyun MK, Lee JY, et al. Prevalence of thyroid nodules and their associated clinical parameters: a large-scale, multicenter-based health checkup study. Korean J Intern Med. 2017 Jul;:7. doi: 10.3904/kjim.2015.273. Epub. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moifo B, Moulion Tapouh JR, Dongmo Fomekong S, Djomou F, Manka’a Wankie E. Ultrasonographic prevalence and characteristics of non-palpable thyroid incidentalomas in a hospital-based population in a sub-Saharan country. BMC Med Imaging. 2017;17(1):21. doi: 10.1186/s12880-017-0194-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zheng L, Yan W, Kong Y, Liang P, Mu Y. An epidemiological study of risk factors of thyroid nodule and goiter in Chinese women. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8(7):11379–11387. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Panagiotou G, Komninou D, Anagnostis P, et al. Association between lifestyle and anthropometric parameters and thyroid nodule features. Endocrine. 2017;56(3):560–567. doi: 10.1007/s12020-017-1285-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ayturk S, Gursoy A, Kut A, Anil C, Nar A, Tutuncu NB. Metabolic syndrome and its components are associated with increased thyroid volume and nodule prevalence in a mild-to-moderate iodine-deficient area. Eur J Endocrinol. 2009;161(4):599–605. doi: 10.1530/EJE-09-0410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guo H, Sun M, He W, et al. The prevalence of thyroid nodules and its relationship with metabolic parameters in a Chinese community-based population aged over 40 years. Endocrine. 2014;45(2):230–235. doi: 10.1007/s12020-013-9968-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Buscemi S, Massenti FM, Vasto S, et al. Association of obesity and diabetes with thyroid nodules. Endocrine. 2017 Aug;:23. doi: 10.1007/s12020-017-1394-2. Epub. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Knudsen N, Bulow I, Laurberg P, Ovesen L, Perrild H, Jorgensen T. Association of tobacco smoking with goiter in a low-iodine-intake area. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162(4):439–443. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.4.439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans Betel-quid and areca-nut chewing and some areca-nut derived nitrosamines. IARC Monogr Eval Carcinog Risks Hum. 2004;85:1–334. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee CH, Lee JM, Wu DC, et al. Independent and combined effects of alcohol intake, tobacco smoking and betel quid chewing on the risk of esophageal cancer in Taiwan. Int J Cancer. 2005;113(3):475–482. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dasgupta R, Chatterji U, Nag TC, Chaudhuri-Sengupta S, Nag D, Maiti BR. Ultrastructural and hormonal modulations of the thyroid gland following arecoline treatment in albino mice. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2010;319(1–2):1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2010.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bouvard V, Loomis D, Guyton KZ, et al. Carcinogenicity of consumption of red and processed meat. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(16):1599–1600. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00444-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wie GA, Cho YA, Kang HH, et al. Red meat consumption is associated with an increased overall cancer risk: a prospective cohort study in Korea. Br J Nutr. 2014;112(2):238–247. doi: 10.1017/S0007114514000683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tavani A, La Vecchia C, Gallus S, et al. Red meat intake and cancer risk: a study in Italy. Int J Cancer. 2000;86(3):425–428. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(20000501)86:3<425::aid-ijc19>3.0.co;2-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Flores-Mateo G, Rojas-Rueda D, Basora J, Ros E, Salas-Salvado J. Nut intake and adiposity: meta-analysis of clinical trials. Am J Clin Nutr. 2013;97(6):1346–1355. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.111.031484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xu W, Chen Z, Li N, et al. Relationship of anthropometric measurements to thyroid nodules in a Chinese population. BMJ Open. 2015;5(12):e008452. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fiore E, Vitti P. Serum TSH and risk of papillary thyroid cancer in nodular thyroid disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97(4):1134–1145. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-2735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Volzke H, Alte D, Kohlmann T, et al. Reference intervals of serum thyroid function tests in a previously iodine-deficient area. Thyroid. 2005;15(3):279–285. doi: 10.1089/thy.2005.15.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Ultrasound images of thyroid glands with or without nodule in centenarians. (A) Normal thyroid gland without TN, female, 104 years old; (B) a solitary cystic thyroid nodule in the right lobe of thyroid gland, female, 101 years old; (C) a solitary solid nodule in the right lobe of thyroid gland, female, 103 years old; (D) multiple nodules including solid and mixed mass in the left lobe of thyroid gland, female, 101 years old. Arrows point to the three thyroid nodules.

Abbreviation: TN, thyroid nodule.