Abstract

Pre-eclampsia is characterized by new-onset hypertension and proteinuria at ≥20 weeks of gestation. In the absence of proteinuria, hypertension together with evidence of systemic disease (such as thrombocytopenia or elevated levels of liver transaminases) is required for diagnosis. This multisystemic disorder targets several organs, including the kidneys, liver and brain, and is a leading cause of maternal and perinatal morbidity and mortality. Glomeruloendotheliosis is considered to be a characteristic lesion of pre-eclampsia, but can also occur in healthy pregnant women. The placenta has an essential role in development of this disorder. Pathogenetic mechanisms implicated in pre-eclampsia include defective deep placentation, oxidative and endoplasmic reticulum stress, autoantibodies to type-1 angiotensin II receptor, platelet and thrombin activation, intravascular inflammation, endothelial dysfunction and the presence of an antiangiogenic state, among which an imbalance of angiogenesis has emerged as one of the most important factors. However, this imbalance is not specific to pre-eclampsia, as it also occurs in intrauterine growth restriction, fetal death, spontaneous preterm labour and maternal floor infarction (massive perivillous fibrin deposition). The severity and timing of the angiogenic imbalance, together with maternal susceptibility, might determine the clinical presentation of pre-eclampsia. This Review discusses the diagnosis, classification, clinical manifestations and putative pathogenetic mechanisms of pre-eclampsia.

Introduction

Pre-eclampsia is characterized by new-onset hypertension and proteinuria at ≥20 weeks of gestation.1–6 In the absence of proteinuria, diagnosis requires the presence of hypertension together with evidence of systemic disease (such as thrombocytopenia, elevated levels of liver transaminases, renal insufficiency, pulmonary oedema and visual or cerebral disturbances).7,8 This gestation-specific syndrome affects 3–5% of all pregnancies, and is a leading cause of maternal and perinatal morbidity and mortality.1–7,9 Pre-eclampsia can progress to eclampsia, which is characterized by new-onset grand mal seizures and affects 2.7–8.2 women per 10,000 deliveries.10 Complications of pre-eclampsia or eclampsia include cerebrovascular accidents, liver rupture, pulmonary oedema or acute renal failure that can result in maternal death.11 Adverse perinatal outcomes of pre-eclampsia and eclampsia are attributed largely to preterm delivery, which occurs secondary to maternal or fetal complications, intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) and fetal death.9

A placenta, but not the fetus, is required for the development of pre-eclampsia, as pre-eclampsia can occur in patients with hydatidiform moles.12 Indeed, the only effective treatment for pre-eclampsia is delivery of the placenta. The traditional view of the pathogenetic mechanisms involved in pre-eclampsia is that an ischaemic placenta produces soluble factors (formerly called toxins—hence the name toxaemia of pregnancy) that, when released into the maternal circulation, are responsible for the clinical manifestations of the disease.13,14 These soluble factors are thought to cause endothelial cell dysfunction,15,16 intravascular inflammation17–19 and activation of the haemostatic system;20 accordingly, pre-eclampsia is considered to be primarily a vascular disorder. The clinical manifestations of pre-eclampsia result from the involvement of multiple organs, including the kidneys, liver, brain, heart, lung, pancreas and the vasculature.2,21 This Review discusses the diagnosis, classification, clinical manifestations and putative pathogenetic mechanisms of pre-eclampsia. Its prediction, prevention and management will be addressed in part 2 of this Review as a separate article.22

A historical overview

Eclampsia was first recognized as a convulsive disorder of pregnancy; the name is derived from the Greek word eklampsis (meaning lightning), reflecting the sudden onset of convulsions in pregnant women.23 Albuminuria was reported in patients with eclampsia in 1840,24 and approximately 50 years later, the presence of hypertension was also recognized in such patients.25 The term pre-eclampsia was subsequently introduced to describe the state preceding eclampsia.1 In the early 20th century, differentiating between glomerulonephritis (then known as Bright disease) and pre-eclampsia in pregnant women was challenging, as both conditions are associated with hypertension and proteinuria.21 The prevention of eclampsia was proposed as a major goal of prenatal care in 1901, which led directly to the current emphasis on detecting early signs of pre-eclampsia.26 As a consequence, pregnant women now have their blood pressure measured and urine tested for proteinuria at every antenatal visit.

Risk factors

Pre-eclampsia often occurs in young women having their first pregnancy. This observation has been attributed to an immune mechanism, as the maternal immune system develops tolerance to paternal alloantigens following exposure to seminal fluid and/or sperm.27 Prolonged exposure to semen is thought to decrease the risk of developing pre-eclampsia (Box 1),27 possibly explaining the increased risk of this condition in women with a short interval between first coitus and conception, those undergoing assisted reproductive technologies involving artificial insemination, women using barrier methods of contraception and in multiparous women who have changed partner since the previous pregnancy.27 A paternal component to the risk of pre-eclampsia has also been proposed, known as the ‘dangerous father’ hypothesis, according to which men who have fathered a previous pregnancy complicated by pre-eclampsia have an increased risk of doing so again with a new partner.28

Box 1. Risk factors for pre-eclampsia192.

Nulliparous women

History of pre-eclampsia in previous pregnancy

Multi-fetal gestation

Family history of pre-eclampsia (mother or sister)

Pre-existing medical conditions, including chronic hypertension, diabetes mellitus, antiphospholipid syndrome,197,198 thrombophilia, autoimmune disease, renal disease, infertility

Limited sperm exposure

Familial clustering supports a genetic component to the risk of developing pre-eclampsia.29 In twin studies, estimates of the heritability of pre-eclampsia range from 22% to 47%.30 Candidate-gene studies have demonstrated significant associations between DNA variants and pre-eclampsia for a few genes in the maternal and fetal genome, including collagen α1(I) chain (COL1A1), IL-1α (IL1A) for the maternal genotype and urokinase plasminogen activator surface receptor (PLAUR) for the fetal genotype.31 Moreover, maternal-fetal genotype incompatibility of lymphotoxin-α (LTA), von Willebrand factor (VWF) and collagen α2(IV) chain (COL4A2) seem to be a risk factor for pre-eclampsia.32 Other specific DNA variants that increase the risk of pre-eclampsia include the Factor V Leiden mutation, mutations in endothelial nitric oxide synthase, human leukocyte antigen and angiotensin-converting enzyme.33 A meta-analysis of 11 studies, involving 1,297 cases of pre-eclampsia and 1,791 controls, found a modest but significant association between pre-eclampsia and the single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) rs1799889 in SERPINE1. Specifically, this association involved the –675 4G/5G polymorphism (4G versus 5G) and, for the recessive genetic model (4G/4G versus 4G/5G + 5G/5G), the odds ratio was 1.36 (95% CI 1.13–1.64, P = 0.001).34 By contrast, a genome-wide association study of 177 cases of pre-eclampsia and 166 controls did not identify any variants associated with pre-eclampsia;35 however, associations with four SNPs in PSG11 (which encodes pregnancy-specific β1-glycoprotein 11) reached nominal significance.35

Diagnosis of pre-eclampsia

Typical presentation

Pre-eclampsia is traditionally diagnosed by new-onset hypertension and proteinuria at ≥20 weeks of gestation. Although hypertension is essential according to all diagnostic criteria, the requirement of proteinuria for the diagnosis of pre-eclampsia is a matter of debate. Some professional organizations allow diagnosis of pre-eclampsia on the basis of the presence of new-onset hypertension together with evidence of systemic involvement, such as thrombocytopenia, elevated levels of liver transaminases, renal insufficiency, pulmonary oedema and visual or cerebral disturbances (Box 2).7,8 The rationale for omitting proteinuria is that pre-eclampsia might manifest before glomerular capillary endotheliosis becomes severe enough to induce proteinuria.36,37 Moreover, patients with nonproteinuric pre-eclampsia (with evidence of systemic involvement) are more likely than those with gestational hypertension to have severe hypertension and undergo premature delivery. However, women with proteinuric pre-eclampsia are at greater risk than women with nonproteinuric pre-eclampsia to have severe hypertension, and deliver premature babies or babies who are small for their gestational age.38

Box 2. Classification of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy.

Chronic hypertension

Blood pressure ≥140/90 mmHg before pregnancy and at <20 weeks of gestation, or diagnosed for the first time during pregnancy and does not resolve postpartum

Pre-eclampsia and eclampsia

Blood pressure ≥140/90 mmHg on two occasions at least 4 h apart or ≥160/110 mmHg within a shorter interval (minutes), at ≥20 weeks of gestation, in women with previously normal blood pressure and proteinuria*

In the absence of proteinuria, new-onset hypertension plus new onset of any of the following features: serum creatinine concentrations >97 µmol/l or doubling of serum creatinine concentration in the absence of other renal disease; elevation of liver transaminases to twice normal concentration; pulmonary oedema; and cerebral or visual symptoms

Eclampsia: seizures in women with pre-eclampsia that cannot be attributed to other causes

Pre-eclampsia superimposed on chronic hypertension

Women with hypertension (at <20 weeks gestation) and new-onset proteinuria*

In women with hypertension and proteinuria* (at <20 weeks gestation), development of any of the following features: sudden increase in proteinuria;* sudden increase in blood pressure in women whose hypertension was previously well controlled; thrombocytopenia (platelet count <100,000 per mm3); and elevated liver transaminase levels

Gestational hypertension

New-onset blood pressure ≥140/90 mmHg detected at ≥20 weeks gestation without proteinuria

Pre-eclampsia does not develop and blood pressure returns to normal by 12 weeks postpartum

*Defined as urinary protein excretion ≥300 mg/24 h, a total protein:creatinine ratio ≥30 mg/mmol (or ≥0.3 when both are measured in mg/dl) or a dipstick reading of ≥1+ (only if other quantitative methods are not available).7

The gold standard for diagnosis of proteinuria during pregnancy is total protein ≥300 mg in a 24 h urine sample. However, this cut-off has not been adequately validated and might be too high;39 a subsequent study demonstrated that the mean total protein concentration in 24 h urine samples from normal pregnant women was 117.0 mg (upper limit of 95% CI –259.4 mg).39 Urinary dipstick tests for proteinuria are considered unreliable owing to variations in protein excretion, activity, diet and posture at the time of assessment.39 However, a dipstick result of ≥1+ has a positive-predictive value of 82–92% for predicting 24 h urinary protein levels of ≥300 mg.35,36 By contrast, the negative predictive value of a negative or trace dipstick result was low (34–60%).40,41 The assessment of proteinuria by protein:creatinine ratios is recommended in several guidelines, with the most commonly used cut-off value being ≥30 mg/mmol.7 However, protein:creatinine ratios can vary depending on the time of day the measurement is taken42 and this parameter might, therefore, be unreliable for the diagnosis of proteinuria.39 Indeed, a recent study examined the urinary protein:creatinine ratio at three different time points (at 0800 h, 1200 h and 1700 h) and showed that the ratios varied throughout the day (mean coefficient of variation 36%). However, no differences among the three measurements with respect to sensitivity (89–96%) and specificity (75–78%) to predict proteinuria were found.43 A systematic review concluded that the spot protein:creatinine ratio is a reasonable ‘rule out’ test for significant proteinuria during pregnancy because of its high sensitivity and low negative likelihood ratio (0.12).44 Of note, although the presence of proteinuria can aid in the diagnosis of pre-eclampsia, the severity of proteinuria has limited prognostic value45 and, consequently, severe proteinuria has been removed from the diagnostic criteria for severe pre-eclampsia by some professional organizations.7

Atypical presentations

Hypertension and proteinuria have been recognized as the essential criteria for diagnosis of pre-eclampsia. However, this multisystemic disease can also present with atypical manifestations, giving rise to its nickname ‘the great imitator’.46 Some patients present with HELLP syndrome (haemolysis, elevated liver transaminases, low platelets),47–49 which is widely regarded as a form of pre-eclampsia, despite it failing to meet conventional diagnostic criteria. HELLP syndrome occurs only in pregnant women, resolves with delivery and is frequently, but not always, associated with hypertension and proteinuria.50 Patients can also present with right upper quadrant pain (attributable to distention of the capsule of Glisson), and some components of HELLP syndrome, but without hypertension and proteinuria.50

Classification

Pre-eclampsia can be classified as early (<34 weeks) or late (≥34 weeks), according to gestational age at diagnosis or delivery (Box 3).3,51 Although several other gestational age cut-offs have been suggested (such as 32 weeks and 36 weeks),52 34 weeks remains the most commonly used,53,54 presumably as the rate of neonatal morbidities declines considerably after reaching this gestational time point. For instance, in women with severe pre-eclampsia, expectant management is no longer considered and induction of labour is recommended after the 34th week of gestation.7 However, whether early and late pre-eclampsia have different pathogenetic mechanisms or are merely gradations of the same underlying condition remains unclear.55 Pre-eclampsia can also be classified according to its severity (Box 4);1,56 nonetheless, to avoid conveying a false sense of security to clinicians, some professional organizations have abandoned the term ‘mild or severe’ pre-eclampsia in favour of ‘pre-eclampsia with or without severe features’.7

Box 3. Classification of pre-eclampsias.

Early pre-eclampsia (<34 weeks*)

Uncommon (prevalence 0.38% or 12% of all pre-eclampsia)201

Associated with extensive villous and vascular lesions of the placenta

Higher risk of maternal and fetal complications than late pre-eclampsia

Late pre-eclampsia (≥34 weeks*)

Majority of all cases of pre-eclampsia (prevalence 2.72% or 88% of all pre-eclampsia)201

Minimal placental lesions

Maternal factors (such as metabolic syndrome and hypertension) have important roles

Most cases of eclampsia and maternal death occur in late disease

Box 4. Severe features of pre-eclampsia (one or more of these findings).

Systolic blood pressure ≥160 mmHg, or diastolic blood pressure ≥110 mmHg on two occasions at ≥4 h apart while the patient is on bed rest

Platelet count <100,000 per mm3

Elevated liver enzymes (twice normal concentrations)

Renal insufficiency (serum creatinine concentration >1.1 mg/dl or a doubling of serum creatinine concentration) or oliguria (<500 ml in 24 h)

Pulmonary oedema or cyanosis

New-onset cerebral or visual disturbances

Severe persistent right upper quadrant or epigastric pain

Adapted from the Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 205, Sibai, B. M. Evaluation and management of severe preeclampsia before 34 weeks’ gestation, 191–198 © (2011), with permission from Elsevier.

Pathogenetic mechanisms

Placental ischaemia

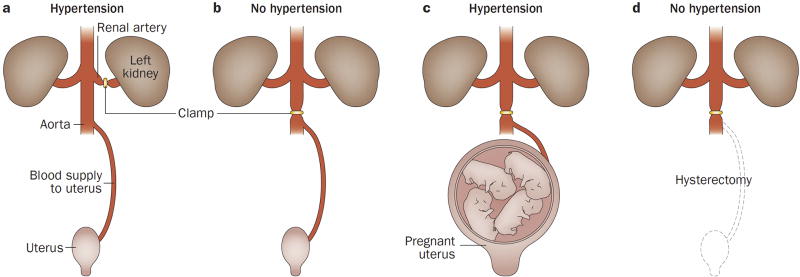

The central hypothesis governing our understanding of pre-eclampsia is that the disorder results from ischaemia of the placenta, which in turn releases factors into the maternal circulation that are capable of inducing the clinical manifestations of the disease. This concept emerged from observations that placental infarctions are common in patients with eclampsia.13 In 1914, researchers proposed that placental infarctions are due to interference with the maternal blood supply to the placenta, and that a necrotic placenta releases products directly into the intervillous space and maternal circulation.13 Importantly, this hypothesis was supported by studies in which the injection of placental extracts into guinea pigs elicited convulsions with hepatic and renal lesions, similar to those observed in women who died of eclampsia.13 In 1940, studies in pregnant dogs showed that clamping of the abdominal aorta (which reduced uteroplacental perfusion by 50%) led to maternal hypertension that resolved after release of the clamp (Figure 1). This hypertensive response was not observed in nonpregnant dogs.57 A uteroplacental origin of the signal driving this hypertensive response was supported by the observation that, after removal of the pregnant uterus, clamping of the aorta no longer elicited hypertension.57 Subsequent work revealed that uteroplacental blood flow is decreased in women with pre-eclampsia.58

Figure 1. An experiment supporting the concept that hypertension in pregnancy represents a uteroplacental response to ischaemia.

A. In the Goldblatt model of renovascular hypertension, clamping the renal artery leads to development of hypertension through renal ischaemia in nonpregnant animals. B. By contrast, clamping the aorta below the renal arteries does not induce hypertension in nonpregnant animals. C. Aortic clamping in pregnant animals leads to hypertension. D. After hysterectomy, however, hypertension can no longer be elicited by aortic clamping, suggesting that the ischaemic pregnant uterus is the source of signals that lead to maternal systemic hypertension. Permission obtained from Semin. Perinatol. 12, Romero, R. et al. Toxemia: new concepts in an old disease, 302–323 © Elsevier (1988).

Transformation of the spiral arteries

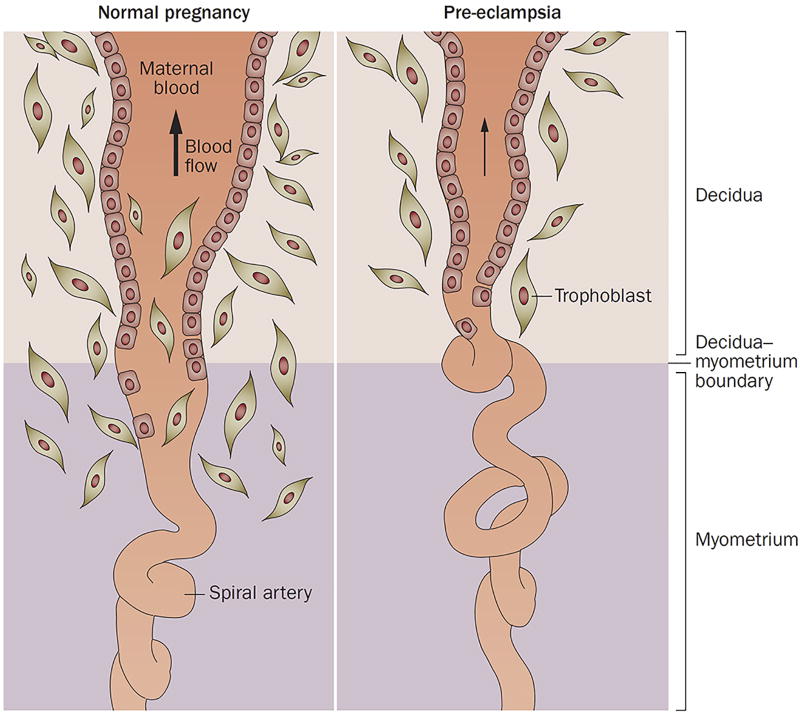

During a normal pregnancy, uterine blood flow increases to enable perfusion of the intervillous space of the placenta and to support fetal growth. The increased blood flow is achieved by physiological transformation of the spiral arteries of the uterus, a process in which trophoblasts invade the arterial wall, destroy the media and transform the spiral arteries from narrow-diameter to large-diameter vessels, thereby enabling adequate perfusion of the placenta (Figures 2 and 3a).59

Figure 2. Failure of physiological transformation of the spiral arteries is implicated in pre-eclampsia.

A. In a normal pregnancy, physiological transformation of the myometrial segment of the spiral artery occurs. Trophoblast cells extend to both the decidual segment and one-third of the myometrial segment of the spiral artery. Both the arterial media and endothelium are destroyed by trophoblasts, converting the arteries into wide-calibre vessels and increasing the delivery of blood to the intervillous space. B. In pregnancies affected by pre-eclampsia, a key feature associated with the failure of physiological transformation of the spiral arteries is lack of invasion of the trophoblasts into the myometrial segment of the spiral artery. The resulting lack of transformation of blood vessels results in narrow spiral arteries, a disturbed pattern of blood flow and reduced uteroplacental perfusion. Permission obtained from Nature Publishing Group © Moffett-King, A. et al. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2, 656–663 (2002).

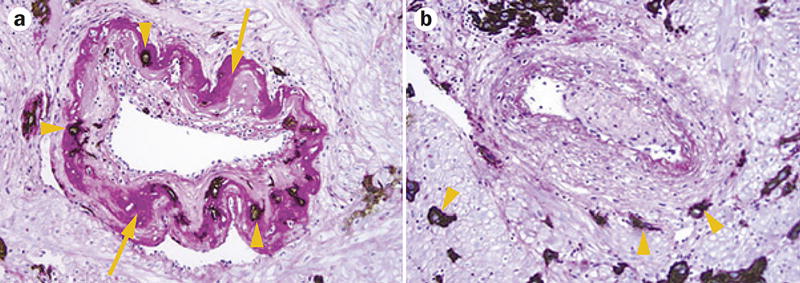

Figure 3. Transformed and nontransformed spiral arteries in the myometrium.

A. Transformed spiral arteries are characterized by the presence of intramural trophoblasts (arrowheads) and fibrinoid degeneration (arrows) of the arterial wall. B. Nontransformed spiral arteries lack intramural trophoblasts and fibrinoid degeneration, and retain intact arterial contours. Arrowheads indicate the presence of trophoblasts in myometrium, but not in the wall of the spiral artery. Both images stained with cytokeratin 7 (brown) and periodic acid–Schiff (pink), magnification ×200. Permission obtained from the NIH © Espinoza, J. et al. J. Perinat. Med. 34, 447–458 (2006).

In pre-eclampsia (and eclampsia), the myometrial segment of the spiral artery fails to undergo physiological transformation during the second trimester (Figures 2 and 3b),60 which is thought to explain the uteroplacental ischaemia observed in pre-eclampsia. Moreover, nontransformed spiral arteries are prone to atherosis, characterized by the presence of lipid-laden macrophages within the lumen, fibrinoid necrosis of the arterial wall and a mononuclear perivascular infiltrate.61,62 The atherotic lesions resemble atherosclerotic plaques and are proposed to result from several pathophysiological mechanisms that include immunological reaction against fetal tissue,63,64 shear flow stress caused by abnormal blood flow in nontransformed spiral arteries, a systemic inflammatory response that involves the uterine decidua and maternal genetic predisposition.65 Atherosis might further impede blood flow to the placenta during the third trimester. However, the reader should note that failure of physiological transformation of the spiral arteries is neither specific to pre-eclampsia nor sufficient to cause it,66 as such failure has also been observed in other obstetric syndromes, including spontaneous abortion,67,68 IUGR,69,70 fetal death,68 placental abruption,71 preterm labour72 and preterm premature rupture of membranes.73 The mechanisms responsible for failure of physiological transformation of the spiral arteries have not been fully elucidated.

Human pregnancy is characterized by deep placentation, in which trophoblast cells in the placental bed invade not only the decidua, but also one-third of the thickness of the myometrium.59,66,74 As invasive trophoblasts are responsible for transformation of the spiral arteries, some researchers have suggested that an abnormality in trophoblasts might result in shallow placentation and inadequate transformation of the spiral arteries, leading to pre-eclampsia.75

Other than trophoblast abnormalities, the effects of shear stress on vascular endothelium can affect remodelling of the spiral arteries. The diameter of the uterine artery (especially the proximal portion of vessels that are upstream of the branches into the spiral arteries) increases prior to completion of placentation, possibly as a consequence of the vasodilatatory properties of elevated levels of oestrogen.76 Blood flow in the uterine arteries also changes during the first few weeks of pregnancy and subsequently, haemochorial placentation converts the spiral arteries into a low-velocity, high-flow chamber.59 Decreased downstream resistance accelerates blood flow velocity in afferent (radial and arcuate) arteries, increasing shear stress on the arterial wall. The increase in shear stress stimulates the endothelium to augment its production of nitric oxide, resulting in vasodilatation, which further lowers uterine vascular resistance, and in turn, normalizes shear stress on the arterial wall. The increase in blood flow resulting from a large lumen (but decreased flow velocity) might stimulate changes in both vascular smooth muscle and the extracellular matrix and, in turn, vascular remodelling.77

Hypoxia and trophoblast invasion

Upon arrival of the conceptus to the endometrium, nutrition is initially provided by secretions from the endometrial glands (histiotrophic nutrition).78 Subsequently, the blastocyst invades the decidua. In the early phases of implantation, the gestational sac exists in an environment with low oxygen tension, which favours trophoblast proliferation. Trophoblasts anchor the blastocyst to maternal tissues, and also plug the tips of the spiral arteries within the decidua.79 Eventually, lacunae are formed within the trophoblasts, which subsequently coalesce to create the intervillous space. Opening of the spiral arteries into the intervillous space enables the development of haemochorial placentation, and shifts nutrition from a histiotrophic to haematotrophic type.80

The initial burst of blood into the intervillous space increases oxygen tension, generating oxidative stress on the trophoblasts, which promotes trophoblast differentiation from a proliferative to an invasive phenotype. Differentiated trophoblasts invade deeper into the decidua, reaching into the superficial myometrium80 and facilitating physiological transformation of the spiral arteries. Thus, the initial phase of placentation occurs under conditions of relative hypoxia.81 Indeed, hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-1α, a marker of cellular oxygen deprivation, is expressed at high levels in trophoblasts. Persistent hypoxia or failure to downregulate transforming growth factor β3 (TGF-β3) expression after 9 weeks of gestation might result in failure of trophoblasts to differentiate from the proliferative to invasive phenotype,82 shallow trophoblast invasion and inadequate transformation of the spiral arteries,82 although this hypothesis remains unproven.

Considerable evidence supports a role for hypoxia in creating an environment that predisposes to implantation disorders, including pre-eclampsia: expression of HIF-1α and HIF-2α protein is increased in the placentas of women with pre-eclampsia;83 overexpression of HIF-1α leads to hypertension, proteinuria and fetal growth restriction in mice;84 mice with deletion of the Comt gene, which encodes catechol O-methyltransferase (an enzyme that catabolizes estradiol to 2-methoxyestradiol), develop hypertension and proteinuria when pregnant;85 and 2-methoxyestradiol, an inhibitor of HIF-1α, can suppress the production of soluble vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 1 (sVEGFR-1), a potent antiangiogenic factor.85 This observation is consistent with the finding that women with pre-eclampsia had lower placental COMT protein expression85 and serum levels of 2-methoxyestradiol85 than healthy controls; however, these findings could not be replicated in subsequent studies.86,87 An important point to note is that direct evidence for the presence of hypoxia in the intervillous space in patients destined to develop pre-eclampsia is lacking because these measurements cannot be performed in ongoing pregnancies. Moreover, expression of HIF-1α is upregulated not only by hypoxia, but also by inflammatory stimuli (for example, thrombin, vasoactive peptides, cytokines, such as tumour necrosis factor [TNF], and reactive oxygen species [ROS]), especially those mediated by nuclear factor κB (NF-κB), as the promoter of HIF-1α contains an NF-κB binding site.88

Inadequate deep placentation can also result from a decidual defect; optimal decidualization requires proper preconditioning, which is achieved by successive menstruations.89 Inadequate preconditioning might explain the high rate of pre-eclampsia in young women (such as those aged <20 years).89 Another possibility is that defective placentation might be the result of combinations of factors that affect both decidua and trophoblasts.89 Indeed, implantation creates conditions in which fetal cells (carrying paternal antigens) and maternal cells come into contact in the decidua; a role for the immune system in normal placentation is, therefore, easy to envision. Successful pregnancy requires that the maternal immune system does not reject the trophoblast.27 Roles for natural killer cells in the decidua, HLA-C molecules on the fetal trophoblast (its only known polymorphic histocompatibility antigen) and regulatory T cells have been implicated in the tolerogenic state associated with normal pregnancy, as well as in pre-eclampsia.27

Maternal-fetal immune recognition at the site of placentation is highly individualized by two polymorphic gene systems: HLA-C molecules of trophoblasts and their cognate receptors, killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptors (KIRs) of natural killer cells.27 At least two haplotype groups of KIR (A and B) and two types of HLA-C (C1 and C2) are known. HLA-C2 interacts with KIRs more strongly than does HLA-C1.27,90 Uterine natural killer cells release chemokines, angiogenic factors and cytokines that promote trophoblast invasion. These secretions are increased upon binding of HLA-C antigens to stimulatory KIRs (haplotype B), whereas they are reduced by antigen binding to haplotype A of KIRs. Thus, KIR BB mothers carrying HLA-C1 fetuses might have the best chance of adequate placentation and avoiding pre-eclampsia. By contrast, KIR AA mothers carrying HLA-C2 fetuses might have an increased susceptibility to pre-eclampsia.27,90

Endoplasmic reticulum stress

Narrow spiral arteries create conditions for ischaemia-reperfusion injury in the intervillous space. This injury, in turn, might lead to endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress, which regulates cell homeostasis through its involvement in post-translational modifications and protein folding.91 During states of energy crisis (such as hypoxia), the ER suspends protein folding (referred to as the unfolded protein response, or UPR).92 The UPR can lead to cessation of cell proliferation and, when severe, apoptosis. Trophoblast apoptosis93 results in the release of microparticles and nanoparticles into the maternal circulation, which can stimulate an intravascular inflammatory response.94 Evidence supporting the involvement of ER stress in pre-eclampsia and IUGR includes activation of the UPR, as shown by upregulation of factors involved in several signalling pathways characteristic of UPR activation following ER stress in the placenta.92,95

Oxidative stress

Oxidative stress arises when the production of ROS overwhelms the intrinsic antioxidant defence mechanisms operating in tissues.96 Oxidative stress is relevant to the pathophysiology of pre-eclampsia, as it induces the release of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines as well as trophoblast debris.97 The cause of oxidative stress in the placentas of women with pre-eclampsia is thought to be intermittent hypoxia and reoxygenation, probably resulting from deficient conversion of the myometrial segment of the spiral arteries, which contains a contractile portion of the artery.96 Indeed, radiographic studies of the spiral arteries note these constricted portions at the myometrial segment of the spiral artery just proximal to the myometrial-endometrial junction in both the human and the rhesus monkey.98,99

Increased ROS exposure can lead to protein carboxylation, lipid peroxidation and DNA oxidation—all of which have been observed in placentas of patients with pre-eclampsia.96 Under pathological conditions, such as hypoxia or ischaemia–reperfusion injury, increased conversion of xanthine dehydrogenase to xanthine oxidase promotes the production of uric acid and superoxide from degraded purines (such as xanthine and hypoxanthine).96 Xanthine oxidase expression and activity are increased in invasive trophoblasts obtained from patients with pre-eclampsia.100 Furthermore, placental antioxidant mechanisms are impaired in patients with pre-eclampsia, as shown by their decreased expression of superoxide dismutase and glutathione peroxidase compared with women with normal pregnancies.101

Another important source of free radicals in humans is free haeme, a pro-oxidant molecule produced daily via the degradation of circulating red blood cells. Protection from free haeme is afforded by the actions of haeme oxygenase, which converts free haeme first to biliverdin and subsequently to bilirubin, releasing free iron and carbon monoxide.102 Biliverdin and bilirubin have potent antioxidant properties, whereas carbon monoxide induces vasodilatation, has antiapoptotic properties and promotes angiogenesis.102 Three isoforms of haeme oxygenase have been characterized: HO-1 (inducible), HO-2 (constitutive) and HO-3 (unknown function).102 Several lines of evidence support a role for haeme oxygenases in the pathogenesis of pre-eclampsia. Pregnant Hmox1+/– mice, which have a partial deficiency in HO-1, demonstrate hypertension, small placentas and elevated plasma levels of sVEGFR-1 (all features of pre-eclampsia).103 HO-1 and HO-2 mRNA104 and protein105 expression are decreased in women with pre-eclampsia (the decreased protein expression was detected in peri-infarct regions of the placenta).105 In trophoblasts obtained from women at 11 weeks gestation, HO-1 mRNA expression was lower in individuals who went on to develop pre-eclampsia than in those who had a normal pregnancy.106 mRNA expression of superoxide dismutase and catalase are also lower in peripheral blood samples from patients with pre-eclampsia than in samples from normal pregnant women.104 These findings indicate that pre-eclampsia is associated with a deficiency of antioxidant enzymes in the placenta and probably in the peripheral blood as well.104 Interest in manipulating the expression of HO-1 as a potential therapeutic intervention for pre-eclampsia has been fuelled by preclinical studies; pharmacological induction of HO-1 expression (by cobalt protoporphyrin or pravastatin) can attenuate hypertension, decrease oxidative stress and reduce serum concentrations of sVEGFR-1 in rodent models of pre-eclampsia (generated by either reduced uterine perfusion pressure107 or overexpression of sVEGFR-1 resulting from adenovirus-mediated sFlt1 gene transfer).108

Antibodies to type-1 angiotensin II receptor

Normal pregnancy is characterized by reduced vascular responsiveness to angiotensin II.109 However, pregnant women with pre-eclampsia have increased sensitivity to the effects of angiotensin II, a difference that can be detected as early as 24 weeks of gestation.109 The mechanisms responsible for the physiological refractoriness to angiotensin II in normal pregnancy and the enhanced response to it in pre-eclampsia include genetic predisposition, maladaptive immune responses and environmental triggers.110 A subset of women with pre-eclampsia have detectable serum autoantibodies against type-1 angiotensin II receptor (AT1),111 and such autoantibodies can activate AT1 in endothelial cells, vascular smooth muscle cells and mesangial cells. In pregnant rats, anti-AT1 autoantibodies (either produced endogenously in response to transgenic expression of human renin and angiotensinogen112 or administered by injection of purified anti-AT1 autoantibodies from women with pre-eclampsia113) leads to hypertension, proteinuria, glomerular capillary endotheliosis and increased production of sVEGFR-1114 and soluble endoglin114—these effects can be attenuated by administration of losartan (an AT1-receptor blocker). These observations indicate that proteinuria and renal pathology in rats with anti-AT1 autoantibodies might result from AT1 activation. Anti-AT1 autoantibodies can stimulate the synthesis of NADPH oxidase, a rate-limiting enzyme in the synthesis of ROS, leading to oxidative stress.115 These autoantibodies can also stimulate tissue factor release by monocytes and vascular smooth muscle cells, as well as plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) release by mesangial and trophoblast cells.115 Collectively, these actions can lead to increased thrombin generation, impaired fibrinolysis and consequently fibrin deposition. Anti-AT1-autoantibodies can also stimulate placental production of sVEGFR-1 and, therefore, lead to an antiangiogenic state.114

Of interest, reduced uterine perfusion pressure in rats induces production of anti-AT1-autoantibodies, sVEGFR-1, TNF and endothelin-1, as well as hypertension and proteinuria.116 Similarly, administration of TNF,116 IL-6116 or IL-17117 to pregnant rats results in hypertension, placental oxidative stress and enhanced AT1 activity, the effects of which can be abrogated by AT1 blockade. Furthermore, anti-AT1 autoantibodies stimulate deposition of complement C3 in the placenta and kidneys of pregnant mice, whereas treatment with a complement C3a receptor antagonist inhibited autoantibody-induced elevation of sVEGFR-1, small placenta formation and IUGR.118 These findings suggest that anti-AT1 autoantibodies mediate hypertension during pregnancy through activation of complement C3 and production of antiangiogenic factors.118 However, it is noteworthy that glomerular capillary endotheliosis, a characteristic renal lesion of pre-eclampsia, has not been demonstrated in the reduced uterine perfusion pressure rat model of pre-eclampsia.116

A subset of B cells (CD19+CD5+) might be involved in production of anti-AT1 autoantibodies in pre-eclampsia, as addition of sera from patients with pre-eclampsia to these cells increased both the proportion of CD19+CD5+ cells and anti-AT1 autoantibody activity.119 Moreover, the proportion of CD19+CD5+ B cells was also enriched in peripheral blood from patients with pre-eclampsia versus that from women with normal pregnancies. By contrast, administration of rituximab (an antibody directed against CD20, a co-stimulatory molecule on B cells) to rats with reduced uterine perfusion pressure reduced anti-AT1 autoantibody titres, blood pressure and endothelin-1 levels, as well as depleting B cells. Adoptive transfer of CD4+ T lymphocytes from rats with reduced uterine perfusion pressure to normal pregnant rats increased blood pressure and anti-AT1 autoantibody activity.119 These effects were abrogated by administration of losartan or by B-cell depletion using rituximab.120

Some investigators have proposed that parvovirus infection might be a predisposing factor for pre-eclampsia, as the AT1 epitope recognized by anti-AT1 autoantibodies shares a high degree of homology with parvovirus B19 capsid proteins.121 However, the presence of parvovirus B19 IgG (a marker of previous viral infection) does not correlate with the presence or activity of anti-AT1 autoantibodies.122 Currently, the lack of an immunoassay for this specific AT1 epitope might hinder progress in the understanding and implementation of anti-AT1 autoantibody testing in clinical practice.

Intravascular inflammation

Normal pregnancy is characterized by phenotypic and functional evidence of activation of circulating granulocytes and monocytes,17,123 and the magnitude of this intravascular inflammatory response is increased in patients with pre-eclampsia.17–19 Observational evidence supporting this view includes findings of elevated levels of proinflammatory cytokines in maternal blood of pre-eclampsia.124 Experimental studies have also shown that some features of pre-eclampsia, such as hypertension and placental oxidative stress, can be elicited by administration of TNF,125 IL-6125 or IL-17.117 Although the maternal manifestations of pre-eclampsia have been attributed to intravascular inflammation,17–19 several studies have demonstrated that patients with other obstetric syndromes (such as preterm labour with intact membranes,126 preterm prelabour rupture of membranes,127 IUGR128,129 and pyelonephritis123) have evidence of intravascular inflammation without hypertension and proteinuria. Intravascular inflammation is, therefore, a feature of pre-eclampsia, but is not sufficient to cause the disorder. The mechanisms responsible for intravascular inflammation in pre-eclampsia are thought to include increased release of microparticles and nanoparticles from the syncytiotrophoblast into the maternal circulation,94 as well as proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines released upon activation of NF-κB in the context of ER and oxidative stress.97

Endothelial cell activation and/or dysfunction

Endothelial cell activation and/or dysfunction has been proposed to be a central feature of pre-eclampsia130—a concept that has considerable appeal, as vasospasm is a key component of this disorder. Proteinuria can also be considered as a manifestation of damage to the fenestrated glomerular endothelium. In the original observation supporting this hypothesis, sera from patients with pre-eclampsia (but not from normal pregnant women) induced the release of 51 Cr by human umbilical vein endothelial cells.16,130 Subsequent studies showed that maternal levels of E-selectin and vascular cell adhesion protein 1 (VCAM-1) were higher in patients with pre-eclampsia than in normal pregnant women.131 However, the E-selectin findings are not specific for pre-eclampsia, as elevated levels are also observed in other obstetric syndromes (including pregnancies with small for gestational age fetuses).132 Endothelial cell activation and/or dysfunction is postulated to be secondary to intravascular inflammation.18 Given that other obstetric syndromes also feature intravascular inflammation, a clear explanation of why this phenomenon would lead to endothelial cell dysfunction in some patients and not others is lacking. One possibility is that the different clinical presentations depend upon the degree of inflammation and/or maternal susceptibility to endothelial cell injury.

Platelet and thrombin activation

Pre-eclampsia can be associated with thrombocytopenia (owing to platelet consumption), which is also associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes.49 Moreover, thrombocytopenia can occur before the development of hypertension.49 Several lines of evidence support a role of platelet activation in pre-eclampsia: increased platelet size, reduced platelet lifespan, increased maternal plasma levels of platelet factor 4, β-thromboglobulin and platelet-specific proteins stored in α granules (and released upon activation) and increased production of thromboxane B2 by platelets.20 Platelet activation might also lead to thrombi in the microcirculation of several target organs.2

Since vasospasm and platelet consumption are features of pre-eclampsia, this disorder was proposed to represent an endothelium-platelet abnormality owing to a deficiency in prostacyclin.2 Indeed, prostacyclin has vasodilatatory effects and inhibits platelet aggregation.2 Reduced levels of a stable metabolite of prostacyclin in maternal blood133 and urine2 has been reported in association with pre-eclampsia. Moreover, the placentas of women with pre-eclampsia produce more thromboxane A2 than prostacyclin, and thromboxane A2 can induce vasoconstriction and platelet aggregation.134 A similar argument has been made for a role of nitric oxide in pre-eclampsia, as a deficiency of nitric oxide can cause vasoconstriction and increased platelet aggregation.135 Experimental evidence supporting this hypothesis came from the observation that administration of nitric oxide blockers (inhibitors of nitric oxide synthase such as or L-nitroarginine methyl ester) to pregnant rats resulted in a pre-eclampsia-like syndrome that included hypertension, proteinuria, IUGR and glomerular injury.136

A prominent feature of pre-eclampsia is activation of soluble components of the coagulation cascade.137 Excessive thrombin generation has been consistently demonstrated in pre-eclampsia138 and can be subclinical in nature, or lead to overt disseminated intravascular coagulation in the presence of placental abruption. Excessive thrombin generation might be related to endothelial cell dysfunction, platelet activation, chemotaxis of monocytes, proliferation of lymphocytes, neutrophil activation or excessive generation of tissue factor in response to the activity of proinflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1β and TNF. Thrombin activation can also lead to deposition of fibrin in multiple organ systems, which is a major contributor to the pathology of pre-eclampsia.2 Excessive thrombin generation can be assessed by measuring the concentration of thrombin–antithrombin complexes,138 antithrombin III activity139 or by a thrombin generation assay.140 In some patients, pre-eclampsia and/or HELLP syndrome can be considered as thrombotic microangiopathy-like disorders, in light of the similarities in clinical presentation and pathology observed in multiple organs (thrombocytopenia, haemolysis, endothelial injury, complement activation and deposition of thrombin and/or fibrin in arterioles and capillaries of the brain, kidneys and liver). Examples of other thrombotic microangiopathic disorders include thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura and haemolytic uremic syndrome.141

An antiangiogenic state

Angiogenesis, the formation of new blood vessels from pre-existing ones, is essential for a successful pregnancy.142 Defective angiogenesis has long been considered as a pathway to pre-eclampsia,143 and rigorous research showed that an antiangiogenic state is involved in the pathogenesis of pre-eclampsia.144 Following on from observations that patients with cancer who were treated with antiangiogenic agents—such as bevacizumab, which targets vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-A—developed proteinuria and hypertension,145 an analysis of differential gene expression patterns (microarray experiments) showed that mRNA levels of the soluble VEGF receptor VEGFR-1 were higher in the placentas of patients with pre-eclampsia than in those of healthy pregnant women.144 Subsequently, persuasive evidence was gathered in support of the concept that sVEGFR-1 has a role in the pathogenesis of pre-eclampsia: the median plasma and/or serum levels of sVEGFR-1 are higher in women with pre-eclampsia than in women with normal pregnancies;144,146,147 pre-eclampsia is associated with decreased plasma and/or serum levels of free VEGF and placental growth factor (PlGF);143,144 sera from women with pre-eclampsia demonstrated antiangiogenic effects on endothelial tube formation (a bioassay for angiogenesis), and this effect could be reversed by addition of VEGF and PlGF;144 high levels of sVEGFR-1 in pregnant animals (achieved by adenovirus-mediated sFlt1 gene transfer) induced hypertension, proteinuria and glomerular capillary endotheliosis;144 maternal plasma concentrations of sVEGFR-1 are increased prior to clinical diagnosis of pre-eclampsia146,148–150 and decrease dramatically after delivery;144 maternal plasma levels of sVEGFR-1 are higher in severe pre-eclampsia than in forms of the disease without severe features (previously termed mild pre-eclampsia), as well as higher in early than in late pre-eclampsia;146,147 levels of sVEGFR-1 in plasma samples from the uterine vein are significantly higher than in samples from the antecubital vein in patients with pre-eclampsia, but not in normal pregnant women;151 and several risk factors for pre-eclampsia are associated with increased plasma and/or serum levels of sVEGFR-1 (including a history of pre-eclampsia,152 nulliparity,153 multi-fetal gestations,154 diabetes mellitus,155 chronic hypertension152 and gestational hypertension156).

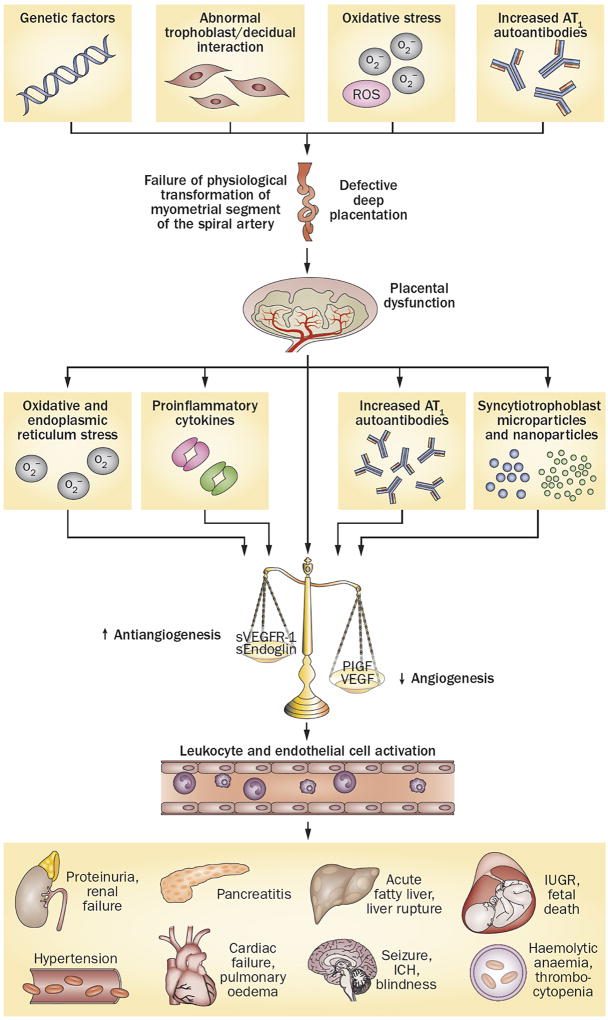

The primary source of the elevated plasma levels of sVEGFR-1 in pre-eclampsia is the placenta,144 although sVEGFR-1 can also be produced by peripheral blood mononuclear cells, macrophages, endothelial cells and vascular smooth muscle cells.157 Initially, sVEGFR-1 was reported to be a ∼90 kDa protein that also existed in a glycosylated form, with a molecular weight ranging 100–120 kDa. Subsequent studies found several variants of this protein, including 60, 100, 145 and 185 kDa isoforms. The 100 kDa isoform (and, to a lesser extent, the 145 kDa isoform) was the main isoform found in cultured cytotrophoblasts, peripheral blood mononuclear cells and uterine microvascular cells, whereas the 145 kDa (along with the 100 kDa) isoform was the predominant form in the plasma of women with pre-eclampsia in one study.158 Another study found that the 130 kDa sVEGFR1–14 variant (which is expressed specifically in vascular smooth muscle cells) is the predominant isoform in the placenta and serum of women with pre-eclampsia.159 Reduced uteroplacental blood flow,160,161 damage to the villous trees,162 syncytial shedding of antiangiogenic factors,162 oxidative stress,103 anti-AT1 autoantibodies,113 proinflammatory cytokines,114 excess thrombin163 and hypoxia164 have all been proposed to be responsible for the shift in the balance of angiogenic and antiangiogenic factors in favour of an antiangiogenic state in pre-eclampsia (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Integrated model of the complex pathophysiology of pre-eclampsia.

Genetic (including maternal–fetal genotype incompatibility) and environmental (preconception exposure to paternal antigens) factors disrupt pregnancy-induced immunomodulation, leading to trophoblast and decidual pathology, shallow endometrial invasion and failure of physiological transformation of the spiral arteries (a disorder of deep placentation). The degree of uterine ischaemia is determined by the severity of the placentation defect and fetal demand on the blood supply. Obstetric disorders occur when these two factors are mismatched. The timing and extent of the mismatch determines the clinical presentation (fetal death, pre-eclampsia with IUGR, IUGR alone and late pre-eclampsia). Pre-eclampsia occurs as a result of adaptive responses involving the release of inflammatory cytokines, anti-AT1 autoantibodies, angiogenic and antiangiogenic factors and syncytiotrophoblast-derived particles into the maternal circulation. Collectively, these factors induce leukocyte activation, intravascular inflammation, endothelial cell dysfunction and excessive thrombin generation. The multiorgan features of pre-eclampsia result from the consequences of these processes in different target organs. Abbreviations: AT1, type-1 angiotensin II receptor; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; ICH, intracerebral haemorrhage; IUGR, intrauterine growth restriction; PlGF, placental growth factor; ROS, reactive oxygen species; s, soluble; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor; VEGFR-1, vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 1.

sVEGFR-1 induced hypertension and proteinuria

sVEGFR-1 exerts antiangiogenic effects by binding to and inhibiting the biological activity of circulating VEGF and PlGF.165 VEGF is important for the maintenance of endothelial cell function, especially in fenestrated endothelium, which is found in brain, liver and glomeruli.166 Indeed, knockout of even only a single allele (Vegfa+/–) results in progressive endothelial degeneration, which is fatal at days 11–12 in mice.142 Increased availability of sVEGFR-1 in pre-eclampsia might also counteract the nitric-oxide-induced vasodilatatory effects of VEGF, which result in hypertension.144 Indeed, plasma nitrite and sVEGFR-1 levels are inversely correlated in pre-eclampsia.167 The overall effect of increased production of sVEGFR-1 is increased maternal vascular tone, which maintains uterine perfusion. Moreover, sVEGFR-1 might antagonize the effects of VEGF-A, and thereby prime endothelial cells to have increased sensitivity to proinflammatory factors such as TNF. These findings suggest the possibility of convergent effects between an antiangiogenic factor and a proinflammatory cytokine.168

In addition, sVEGFR-1 can induce proteinuria by blocking the effects of VEGF-A. Mice with podocyte-specific deletion of Vegfa develop glomerular capillary endotheliosis, the renal lesion observed in pre-eclampsia.169 Conversely, overexpression of VEGF-A in podocytes leads to end-stage renal disease, indicating that appropriate expression of VEGF-A is essential for maintenance of glomerular function.169 Furthermore, women in the second trimester (25–28 weeks gestation) who subsequently developed pre-eclampsia, and those at the time of diagnosis of pre-eclampsia, have higher numbers of podocytes per milligram of creatinine in their urine, identified by immunostaining for podocin after culturing urinary sediments for 24 h, than do those with a normal pregnancy.170 In another study, the number of urinary podocytes (identified by immunostaining for podocalyxin) per millilitre of urine correlated with total urinary protein, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, and was inversely correlated with both free PlGF and the PlGF to sVEGFR-1 ratio at the time of diagnosis of pre-eclampsia.170,171 These observations strengthen the evidence supporting an imbalance between angiogenic and antiangiogenic factors and podocyte injury as having a role in development of the clinical features of pre-eclampsia.

Role of soluble endoglin

Pregnant rats with sVEGFR-1 overexpression (owing to adenovirus-mediated transfection with sFlt1) do not display the full spectrum of clinical symptoms observed in pre-eclampsia.172 Specifically, these animals develop hypertension, proteinuria and glomerular capillary endotheliosis, but not fetal growth restriction, liver dysfunction or thrombocytopenia.172 A second antiangiogenic factor implicated in the pathogenesis of preeclampsia is soluble endoglin, a cell-surface co-receptor of TGF-β1 and TGF-β3 that induces migration and proliferation of endothelial cells.172 Loss-of-function mutations in the human ENG gene cause hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia, a disease characterized by vascular malformations.173 Mice lacking endoglin (Eng−/−) die from defective vascular development, poor vascular smooth muscle development and arrest of endothelial remodelling.174 Recombinant soluble endoglin inhibits endothelial tube formation to the same extent as does sVEGFR-1 in in vitro assays.172 Combined administration of adenoviral vectors encoding endoglin and sFlt-1 to pregnant rats generated a phenotype resembling HELLP syndrome.172 Evidence for the involvement of soluble endoglin in the pathogenetic mechanisms of pre-eclampsia includes higher maternal plasma concentrations of soluble endoglin in women with pre-eclampsia than in healthy pregnant women, both before156 and at the time of 172 clinical diagnosis; levels correlated with severity of disease.156,172 Furthermore, higher maternal serum levels of soluble endoglin were recorded in patients with HELLP syndrome than in those with pre-eclampsia but without HELLP syndrome.172 However, subsequent studies found that plasma levels of soluble endoglin in patients with HELLP syndrome were either higher than175 or not significantly different from176 those in patients with preeclampsia, indicating that soluble endoglin might not be a specific marker for HELLP syndrome.

Specificity of the angiogenic balance

Abnormalities in the profiles of angiogenic and antiangiogenic factors are not pathognomonic for pre-eclampsia. Indeed, such abnormalities are also present in other conditions, including IUGR,150,177 spontaneous preterm labour,178 fetal death,179,180 maternal floor infarction (massive perivillous fibrin deposition),181 spontaneous abortion182 and placental abruption with hypertension.183 Precisely why abnormal angiogenic and antiangiogenic profiles are associated with pre-eclampsia as well as these other complications of pregnancy remains to be elucidated. We believe that the severity and timing of the antiangiogenic state, and probably also maternal susceptibility, might determine the phenotype. For example, a profoundly antiangiogenic state could lead to fetal death, with lesser degrees of severity resulting in pre-eclampsia with IUGR, isolated IUGR or preterm labour with intact membranes. Moreover, several obstetric conditions that are considered to be risk factors for pre-eclampsia—such as molar pregnancy,184 pregnancies with fetal trisomy 13 (the FLT1 gene, which encodes VEGFR-1, is located on chromosome 13)185 and twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome186—also have disruption in the balance of angiogenic and antiangiogenic factors, either in the placenta or peripheral blood.

‘Great obstetrical syndromes’

Obstetric disorders, in contrast to diseases in the nonpregnant state, develop in the context of a unique biological situation—two individuals with different genomes coexisting, one inside the other. The common interest of mother and fetus is successful reproduction; however, conflict can occur when the interests of mother and fetus diverge, perhaps as the result of insults (such as infection or a compromised blood supply). We have proposed the term ‘great obstetrical syndromes’ to describe common features of important obstetric diseases. These features include multiple aetiologies, a long subclinical phase, fetal involvement, generally adaptive clinical manifestations and the involvement of gene–environment interactions.187,188 Although this concept emerged in the context of preterm labour, it applies equally to pre-eclampsia. For example, it has become increasingly clear that pre-eclampsia is not one disorder, but rather different entities recognized by a common phenotype (hypertension and proteinuria), which represents the manifestation of one or more insults to the uteroplacental unit. Thus, we should not be surprised that multiple pathogenetic mechanisms and predisposing factors have been implicated in pre-eclampsia. Patients at risk of pre-eclampsia have an abnormal response to angiotensin II weeks before the clinical diagnosis can be made,109 and abnormal uterine artery Doppler velocimetry measurements and elevated levels of angiogenic factors often manifest months before a clinical diagnosis of pre-eclampsia. Within this long subclinical phase lies the opportunity for prediction and prevention of pre-eclampsia. Although pre-eclampsia is diagnosed by clinical signs in the mother (hypertension and proteinuria), fetal involvement can manifest as IUGR as well as other more-subtle abnormalities, such as thrombocytopenia or neutropenia.189 Importantly, hypertension is not the cause of pre-eclampsia, but it can be considered an adaptive response of the ischaemic uteroplacental unit, which signals to the mother the need to maintain perfusion. The resolution of maternal hypertension that follows fetal death in some patients with pre-eclampsia supports this view.190 However, adaptive responses can become maladaptive; for instance, a hypertensive crisis can result in cerebrovascular accident and maternal death. Finally, the factors that determine pre-eclampsia are likely to result from a combination of genetic predisposition and environmental factors. Patients with urinary tract infections or asymptomatic bacteriuria (considered to result from environmental exposure) during pregnancy are at increased risk of developing pre-eclampsia.191 Familial clustering of cases29 and the results of candidate gene studies suggest that pre-eclampsia has a genetic component;33 however, a gene–environment interaction for pre-eclampsia remains to be proven. Pre-eclampsia also shares many features with atherosclerosis, in which solid evidence of gene–environment interactions exists. An attractive possibility is that pre-eclampsia could be considered a pregnancy-specific clinical manifestation of an increased risk of atherosclerosis.65 This concept might explain why mothers with pre-eclampsia are at increased risk of cardiovascular disease later in life. Pre-eclampsia can also be considered to have survival value. A compromised uterine blood supply can lead to IUGR, which is an adaptive mechanism whereby the fetus slows its growth to avoid outstripping the delivery of oxygen. This adaptation alone might be sufficient for the fetus to reach the end of pregnancy. However, when IUGR alone is insufficient, signals originating from an ischaemic placenta increase the maternal blood pressure to sustain the fetus and prevent its death.

Conclusions

Pre-eclampsia is a leading cause of maternal and perinatal morbidity and mortality. The diagnosis of pre-eclampsia is currently based on nonspecific clinical symptoms and laboratory tests. Multiple pathogenetic mechanisms have been implicated in this disorder, among which an imbalance between angiogenic and antiangiogenic factors has emerged as one of the most important. Thus, diagnosis and subclassification of pre-eclampsia based on biomarkers of specific aetiologies might be useful for identifying patients at risk, monitoring disease progression and providing effective interventions. The roles of anti-AT1 autoantibodies, B cells and gene–environment interactions in the pathogenesis of pre-eclampsia and other obstetric syndromes should be investigated. Further understanding of the mechanisms of abnormal placentation could advance current knowledge of the pathogenesis of pre-eclampsia as well as other disorders, such as fetal growth restriction, stillbirth and some types of spontaneous preterm delivery. In part 2 of this Review, we discuss the prediction, prevention and management of pre-eclampsia.22

Review criteria

A search for original research and review articles published in English between 1840 and 2013 focusing on pre-eclampsia was performed in PubMed, using the following search terms, alone or in combination: “pre-eclampsia,” “toxaemia,” “pregnancy-induced hypertension” and “eclampsia.” The bibliographies of pertinent articles were also examined to identify further relevant papers.

Key points.

Diagnosis of pre-eclampsia is based on new-onset hypertension and proteinuria at ≥20 weeks of gestation or, in the absence of proteinuria, hypertension together with evidence of systemic disease.

Genetic and environmental factors are thought to create conditions leading to defective deep placentation; the injured placenta then releases factors into the maternal circulation that induce pre-eclampsia.

Pre-eclampsia is characterized by multiple aetiologies and pathogenetic mechanisms, a long subclinical phase, fetal involvement, adaptive clinical manifestations and gene-environment interactions.

An imbalance between angiogenic and antiangiogenic factors has emerged as a central pathogenetic mechanism in pre-eclampsia.

An antiangiogenic state can also be observed in conditions other than preeclampsia, including intrauterine growth restriction, fetal death, spontaneous preterm labour and maternal floor infarction.

The severity and timing of the antiangiogenic state, as well as maternal susceptibility, might determine the clinical presentation of pre-eclampsia.

Acknowledgments

Funding

The authors’ research is supported, in part, by the Perinatology Research Branch, Division of Intramural Research, Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, NIH, Department of Health and Human Services (NICHD/NIH/DHHS) and, in part, with Federal funding from the NICHD and NIH under contract no. HHSN275201300006C.

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Author contributions

All authors researched data for the article, made substantial contributions to discussion of the content, wrote, reviewed and edited the manuscript before submission.

References

- 1.Lindheimer MD, Roberts JM, Cunningham GC, Chesley L. In: Chesley’s Hypertensive Disorders in Pregnancy. Lindheimer MD, Roberts JM, Cunningham GC, editors. Elsevier; 2009. pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Romero R, Lockwood C, Oyarzun E, Hobbins JC. Toxemia: new concepts in an old disease. Semin. Perinatol. 1988;12:302–323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Redman CW, Sargent IL. Latest advances in understanding preeclampsia. Science. 2005;308:1592–1594. doi: 10.1126/science.1111726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roberts JM, Gammill HS. Preeclampsia: recent insights. Hypertension. 2005;46:1243–1249. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000188408.49896.c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sibai B, Dekker G, Kupferminc M. Pre-eclampsia. Lancet. 2005;365:785–799. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17987-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Steegers EA, von Dadelszen P, Duvekot JJ, Pijnenborg R. Pre-eclampsia. Lancet. 2010;376:631–644. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60279-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Task Force on Hypertension in Pregnancy, Hypertension in Pregnancy [online] 2013 doi: 10.1097/GRF.0000000000000247. http://www.acog.org/resources_and_publications/task_force_and_work_group_reports/hypertension_in_pregnancy. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Lowe SA, et al. Guidelines for the management of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy 2008. Aust. NZ J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2009;49:242–246. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-828X.2009.01003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hutcheon JA, Lisonkova S, Joseph KS. Epidemiology of pre-eclampsia and the other hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2011;25:391–403. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2011.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thornton C, Dahlen H, Korda A, Hennessy A. The incidence of preeclampsia and eclampsia and associated maternal mortality in Australia from population-linked datasets: 2000–2008. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2013;208:476. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2013.02.042. e471-e475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Adu-Bonsaffoh K, Samuel OA, Binlinla G. Maternal deaths attributable to hypertensive disorders in a tertiary hospital in Ghana. Int. J. Gynaecol Obstet. 2013;123:110–113. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2013.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Acosta-Sison H. The relationship of hydatidiform mole to pre-eclampsia and eclampsia; a study of 85 cases. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1956;71:1279–1282. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(56)90437-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Young J. The aetiology of eclampsia and albuminuria and their relation to accidental haemorrhage: (an anatomical and experimental investigation.) Proc. R. Soc. Med. 1914;7:307–348. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Page EW. On the pathogenesis of pre-eclampsia and eclampsia. J. Obstet. Gynaecol Br. Commonw. 1972;79:883–894. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1972.tb12184.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rodgers GM, Taylor RN, Roberts JM. Preeclampsia is associated with a serum factor cytotoxic to human endothelial cells. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1988;159:908–914. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(88)80169-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roberts JM, Edep ME, Goldfien A, Taylor RN. Sera from preeclamptic women specifically activate human umbilical vein endothelial cells in vitro: morphological and biochemical evidence. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 1992;27:101–108. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.1992.tb00735.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sacks GP, Studena K, Sargent K, Redman CW. Normal pregnancy and preeclampsia both produce inflammatory changes in peripheral blood leukocytes akin to those of sepsis. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1998;179:80–86. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(98)70254-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Redman CW, Sacks GP, Sargent IL. Preeclampsia: an excessive maternal inflammatory response to pregnancy. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1999;180:499–506. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(99)70239-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gervasi MT, et al. Phenotypic and metabolic characteristics of monocytes and granulocytes in preeclampsia. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2001;185:792–797. doi: 10.1067/mob.2001.117311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kenny LC, Baker PN, Cunningham FG. In: Chesley’s Hypertensive Disorders in Pregnancy. Lindheimer MD, Roberts JM, Cunningham GC, editors. Elsevier; 2009. pp. 335–351. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lindheimer MD, Roberts JM, Cunningham GC, Chesley L. In: Chesley’s Hypertensive Disorders in Pregnancy. Lindheimer MD, Roberts JM, Cunningham GC, editors. Elsevier; 2009. pp. 25–36. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chaiworapongsa T, Chaemsaithong P, Korzeniewski SJ, Yeo L, Romero R. Pre-eclampsia part 2: prediction, prevention and management. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2014.103. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nrneph.2014.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Lindheimer MDW. Benson and Pamela Harer Seminar on History. The History of Preeclampsia and Eclampsia as Seen by a Nephrologist. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lever JC. Cases of puerperal convulsions with remarks. Guys Hosp. Rep. 1843;2:495–517. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ballantyne JW. Sphygmographic tracings in puerperal eclampsia. Edinburgh Med. J. 1885;30:1007–1020. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ballantyne JW. A plea for a pro-maternity hospital. Br. Med. J. 1901;1:813–814. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.2101.813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Redman CW, Sargent IL. Immunology of pre-eclampsia. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2010;63:534–543. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2010.00831.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dekker G, Robillard PY, Roberts C. The etiology of preeclampsia: the role of the father. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2011;89:126–132. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2010.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chesley LC, Annitto JE, Cosgrove RA. The familial factor in toxemia of pregnancy. Obstet. Gynecol. 1968;32:303–311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thornton JG, Macdonald AM. Twin mothers, pregnancy hypertension and pre-eclampsia. Br. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 1999;106:570–575. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1999.tb08326.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Goddard KA, et al. Candidate-gene association study of mothers with pre-eclampsia, and their infants, analyzing 775 SNPs in 190 genes. Hum. Hered. 2007;63:1–16. doi: 10.1159/000097926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Parimi N, et al. Analytical approaches to detect maternal/fetal genotype incompatibilities that increase risk of pre-eclampsia. BMC Med. Genet. 2008;9:60. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-9-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ward K, Lindheimer MD. In: Chesley’s Hypertensive Disorders in Pregnancy. Lindheimer MD, Roberts JM, Cunningham GC, editors. Elsevier; 2009. pp. 51–71. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhao L, Bracken MB, Dewan AT, Chen S. Association between the SERPINE1 (PAI-1) 4G/5G insertion/deletion promoter polymorphism (rs1799889) and pre-eclampsia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 2013;19:136–143. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gas056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhao L, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies a maternal copy-number deletion in PSG11 enriched among preeclampsia patients. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2012;12:61. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-12-61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Morgan MA, Thurnau GR. Pregnancy-induced hypertension without proteinuria: is it true preeclampsia? South. Med. J. 1988;81:210–213. doi: 10.1097/00007611-198802000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Barton JR, O’Brien JM, Bergauer NK, Jacques DL, Sibai BM. Mild gestational hypertension remote from term: progression and outcome. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2001;184:979–983. doi: 10.1067/mob.2001.112905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Homer CS, Brown MA, Mangos G, Davis GK. Non-proteinuric pre-eclampsia: a novel risk indicator in women with gestational hypertension. J. Hypertens. 2008;26:295–302. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e3282f1a953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lindheimer MD, Kanter D. Interpreting abnormal proteinuria in pregnancy: the need for a more pathophysiological approach. Obstet. Gynecol. 2010;115:365–375. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181cb9644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Meyer NL, Mercer BM, Friedman SA, Sibai BM. Urinary dipstick protein: a poor predictor of absent or severe proteinuria. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1994;170:137–141. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(94)70398-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kuo VS, Koumantakis G, Gallery ED. Proteinuria and its assessment in normal and hypertensive pregnancy. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1992;167:723–728. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(11)91578-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lindow SW, Davey DA. The variability of urinary protein and creatinine excretion in patients with gestational proteinuric hypertension. Br. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 1992;99:869–872. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1992.tb14431.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Verdonk K, et al. Variation of urinary protein to creatinine ratio during the day in women with suspected pre-eclampsia. BJOG. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.12803. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.12803. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.Cote AM, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of urinary spot protein:creatinine ratio for proteinuria in hypertensive pregnant women: systematic review. BMJ. 2008;336:1003–1006. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39532.543947.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Thangaratinam S, et al. Estimation of proteinuria as a predictor of complications of pre-eclampsia: a systematic review. BMC Med. 2009;7:10. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-7-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Goodlin RC. Severe pre-eclampsia: another great imitator. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1976;125:747–753. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(76)90841-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Weinstein L. Syndrome of hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelet count: a severe consequence of hypertension in pregnancy. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1982;142:159–167. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(16)32330-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Romero R, et al. Clinical significance of liver dysfunction in pregnancy-induced hypertension. Am. J. Perinatol. 1988;5:146–151. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-999675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Romero R, et al. Clinical significance, prevalence, and natural history of thrombocytopenia in pregnancy-induced hypertension. Am. J. Perinatol. 1989;6:32–38. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-999540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sibai BM. Diagnosis, controversies, and management of the syndrome of hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelet count. Obstet. Gynecol. 2004;103:981–991. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000126245.35811.2a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.von Dadelszen P, Magee LA, Roberts JM. Subclassification of preeclampsia. Hypertens. Pregnancy. 2003;22:143–148. doi: 10.1081/PRG-120021060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Crispi F, et al. Predictive value of angiogenic factors and uterine artery Doppler for early-versus late-onset pre-eclampsia and intrauterine growth restriction. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2008;31:303–309. doi: 10.1002/uog.5184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Soto E, et al. Late-onset preeclampsia is associated with an imbalance of angiogenic and anti-angiogenic factors in patients with and without placental lesions consistent with maternal underperfusion. J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal Med. 2012;25:498–507. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2011.591461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Parra-Cordero M, et al. Prediction of early and late pre-eclampsia from maternal characteristics, uterine artery Doppler and markers of vasculogenesis during first trimester of pregnancy. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2013;41:538–544. doi: 10.1002/uog.12264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ogge G, et al. Placental lesions associated with maternal underperfusion are more frequent in early-onset than in late-onset preeclampsia. J. Perinat. Med. 2011;39:641–652. doi: 10.1515/JPM.2011.098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sibai BM. Evaluation and management of severe preeclampsia before 34 weeks’ gestation. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2011;205:191–198. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ogden E, Hildebrand GJ, Page EW. Rise of blood pressure during ischemia of gravid uterus. Proc. Soc. Exp. Bio Med. 1940;43:49–51. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lunell NO, Nylund LE, Lewander R, Sarby B. Uteroplacental blood flow in pre-eclampsia measurements with indium-113m and a computer-linked gamma camera. Clin. Exp. Hypertens. B. 1982;1:105–117. doi: 10.3109/10641958209037184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Brosens I, Robertson WB, Dixon HG. The physiological response of the vessels of the placental bed to normal pregnancy. J. Pathol. Bacteriol. 1967;93:569–579. doi: 10.1002/path.1700930218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Brosens I, Renaer M. On the pathogenesis of placental infarcts in pre-eclampsia. J. Obstet. Gynaecol Br. Commonw. 1972;79:794–799. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1972.tb12922.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hertig AT. Vascular pathology in hypertensive albuminuric toxemias of pregnancy. Clinics. 1945;4:1011–1015. [Google Scholar]

- 62.De Wolf F, Robertson WB, Brosens I. The ultrastructure of acute atherosis in hypertensive pregnancy. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1975;123:164–174. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(75)90522-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Robertson WB, Brosens I, Dixon HG. The pathological resonse of the vessels of the placental bed to hypertensive pregnancy. J. Pathol. Bacteriol. 1967;93:581–592. doi: 10.1002/path.1700930219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Labarrere CA. Acute atherosis. A histopathological hallmark of immune aggression? Placenta. 1988;9:95–108. doi: 10.1016/0143-4004(88)90076-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Staff AC, Dechend R, Redman CW. Review: Preeclampsia, acute atherosis of the spiral arteries and future cardiovascular disease: two new hypotheses. Placenta. 2013;34(Suppl):S73–S78. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2012.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Brosens I, Pijnenborg R, Vercruysse L, Romero R. The “Great Obstetrical Syndromes” are associated with disorders of deep placentation. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2011;204:193–201. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Khong TY, Liddell HS, Robertson WB. Defective haemochorial placentation as a cause of miscarriage: a preliminary study. Br. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 1987;94:649–655. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1987.tb03169.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ball E, Bulmer JN, Ayis S, Lyall F, Robson SC. Late sporadic miscarriage is associated with abnormalities in spiral artery transformation and trophoblast invasion. J. Pathol. 2006;208:535–542. doi: 10.1002/path.1927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Brosens IA, Robertson WB, Dixon HG. The role of the spiral arteries in the pathogenesis of preeclampsia. Obstet. Gynecol. Annu. 1972;1:177–191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Khong TY, De Wolf F, Robertson WB, Brosens I. Inadequate maternal vascular response to placentation in pregnancies complicated by pre-eclampsia and by small-for-gestational age infants. Br. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 1986;93:1049–1059. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1986.tb07830.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Dommisse J, Tiltman AJ. Placental bed biopsies in placental abruption. Br. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 1992;99:651–654. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1992.tb13848.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kim YM, et al. Failure of physiologic transformation of the spiral arteries in patients with preterm labor and intact membranes. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2003;189:1063–1069. doi: 10.1067/s0002-9378(03)00838-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]