SUMMARY

Starvation is life-threatening and therefore strongly modulates many aspects of animal behavior and physiology [1]. In mammals, hunger causes a reduction in body temperature and metabolism [2], resulting in conservation of energy for survival. However, the molecular basis of the modulation of thermoregulation by starvation remains largely unclear. While mammals control their body temperature internally, small ectotherms such as Drosophila set their body temperature by selecting an ideal temperature through temperature preference behaviors [3, 4]. Here, we demonstrate in Drosophila that starvation results in a lower preferred temperature, which parallels the reduction in body temperature in mammals. The insulin/insulin-like growth factor (IGF) signaling (IIS) pathway is involved in starvation-induced behaviors and physiology and is well conserved in vertebrates and invertebrates [5–7]. We show that insulin-like peptide 6 (Ilp6) in the fat body (fly liver and adipose tissues) is responsible for the starvation-induced reduction in preferred temperature (Tp). Temperature preference behavior is controlled by the anterior cells (ACs), which respond to warm temperatures via Transient receptor potential A1 (TrpA1) [4]. We demonstrate that starvation decreases the responding temperature of ACs via insulin signaling, resulting in a lower Tp than in nutrient-rich conditions. Thus, we show that hunger information is conveyed from fat tissues via Ilp6 and influences the sensitivity of warm-sensing neurons in the brain, resulting in a lower temperature set-point. Since starvation commonly results in a lower body temperature in both flies and mammals, we propose that insulin signaling is an ancient mediator of starvation-induced thermoregulation.

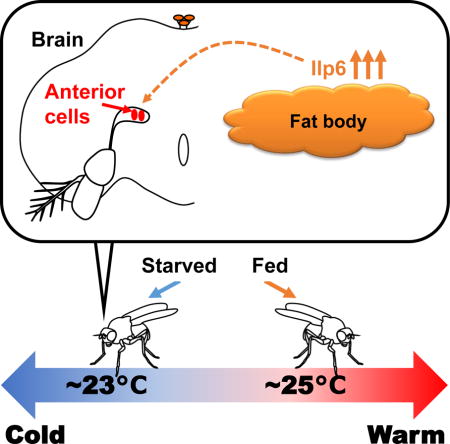

Graphical abstract

In mammals, hunger causes a reduction in body temperature. Umezaki et al. demonstrate in Drosophila that starvation results in a lower preferred temperature, which parallels the reduction in body temperature in mammals. The data suggest that internal nutrient conditions dramatically influence the body temperature of both flies and mammals.

RESULTS

Starvation reduces the preferred temperature in Drosophila

Due to the low mass of small ectotherms, their body temperatures are nearly equivalent to the surrounding temperature [8, 9]. Small ectotherms such as Drosophila avoid harmful temperatures and select appropriate surrounding temperatures to set their body temperature [3, 4, 10]. This behavior, referred to as temperature preference behavior, was examined using a gradient of temperatures ranging from 18–32 °C [4]. To evaluate the effect of starvation on the preferred temperature (Tp), w1118 (control) flies were starved for 18–21 hrs (overnight; O/N) and tested for their temperature preference behavior (Figure 1A). While the normally fed flies preferred a temperature of ~25 °C (Figure 1B: Fed, white box), the flies that were starved overnight preferred an ~ 1.8 °C lower temperature (Figure 1B: starved overnight (Stv 1 O/N), gray box). This reduction in Tp was confirmed in another independent line, yellow white (yw), which preferred an ~ 1.2 °C lower temperature after overnight starvation (Figure S1A). Thus, we determined that starvation dramatically reduces Tp.

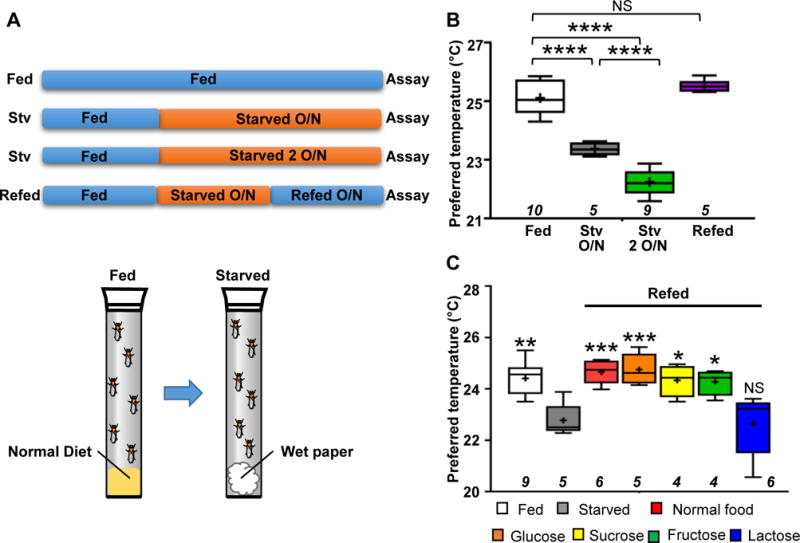

Figure 1. Starvation causes a lower preferred temperature (Tp).

(A) A schematic diagram of the experimental conditions. The flies were reared under normal food conditions (Fed; blue-colored bars), then transferred to starved conditions (water-soaked paper) for either 18–21 hr (overnight (1 O/N)) or 42–45 hr (2 O/N) (starved; orange-colored bars) and tested in behavioral assays for temperature preference. The flies starved for 24 hr were refed overnight (Refed 1 O/N). The details are provided in the experimental procedures.

(B) Comparison of Tp among fed (white box), starved overnight (gray box), starved 2 O/N (green box) and refed (purple box) conditions in w1118 (control) flies. The behavioral experiments were performed at Zeitgeber time (ZT) 4–7. The behavioral experiments performed at ZT 1–3, 4–6, 7–9 and 10–12 are shown in Figure S1B (Fed: blue line, Starved: orange line). Whiskers indicate the minimum-maximum data range of Tp, and boxes indicate the 25–75th percentile data range of Tp. A horizontal line and a cross in each box represent the median and mean, respectively. Italicized numbers indicate the number of trials. One-way ANOVA followed by a post hoc Dunnett’s test was performed to compare each Tp to the control (fed condition). **p<0.01. NS indicates no significance.

(C) Comparison of Tp among flies that were normally fed (white box), starved overnight (gray box), refed with normal food (red box) and refed with the following sugar solutions: Glucose, 1% glucose (orange box); Sucrose, 1% sucrose (yellow box); Fructose, 1% fructose (green box); and Lactose, 1% lactose (blue box). The behavioral experiments were performed at ZT 1–3. The plotting pattern is the same as in Figure 1B. One-way ANOVA and post hoc Dunnett’s test was performed to compare Tp under each condition to starved conditions (gray box). *p<0.05. **p<0.01. ***p<0.001. NS indicates no significance. See also Figure S1 and Table S2.

Longer starvation causes a lower body temperature in mammals [2], we assessed the relationship between the length of starvation and Tp. We found that flies that were starved for 42–45 hrs (over two nights) preferred an ~ 3 °C lower temperature than normally fed flies (Figure 1A and 1B: Stv 2 O/N, green box) and an ~ 1.2 °C lower temperature than the flies that were starved overnight. Therefore, we concluded that starvation dramatically reduces Tp depending on the duration of starvation.

Refeeding results in recovery of the starvation-induced reduction in Tp

While starvation reduces body temperature, refeeding after starvation results in recovery of body temperature in mammals, reaching a similar range to that of normally fed mammals [2]. Therefore, we performed a refeeding test in which the flies were starved for 24 hr and subsequently refed normal fly food overnight (Figure 1A). We found that the refed flies preferred a temperature similar to that of normally fed flies (Figure 1B: Refed, purple box), suggesting that food intake is critical for the modulation of the Tp.

Because normal fly food contains a variety of nutrients including sugar, we asked whether sugar was important for this recovery. To investigate the sugar dependency of the observed effect, we used several sugar solutions and performed refeeding tests. The flies were starved for 24 hr and subsequently refed several sugar solutions overnight (Figure 1A). We found that the flies that were refed glucose, fructose, or sucrose preferred a similar temperature to that of the normally fed flies, but the flies that were refed lactose still preferred a lower temperature (Figure 1C). Notably, flies are not able to detect or digest lactose as a sugar nutrient [11, 12]. Therefore, these data suggest that dietary sugar alone is sufficient for the recovery of the starvation-induced reduction in Tp.

Ilp6 in the fat body is necessary and sufficient for the starvation-induced reduction in Tp

The IIS pathway is involved in starvation-induced behavior and physiology [5–7]. In flies, there are eight Ilps that are expressed in various neurons and organs, and each Ilp has several physiological functions, including the regulation of growth rates, sleep, body size and life-span [13, 14]. First, we asked whether Ilps are involved in the starvation-induced reduction in Tp and compared Tp between fed and starved conditions using ilp1-ilp7 null mutant flies [15]. We found that ilp1, ilp2, ilp3, ilp4, ilp5 and ilp7 single mutants and a triple mutant (ilp2–3,5−/−) showed a starvation-induced reduction in Tp (Figure S2A). Thus, Ilp1, Ilp2, Ilp3, Ilp4, Ilp5, Ilp7 are not required for the starvation-induced reduction in Tp.

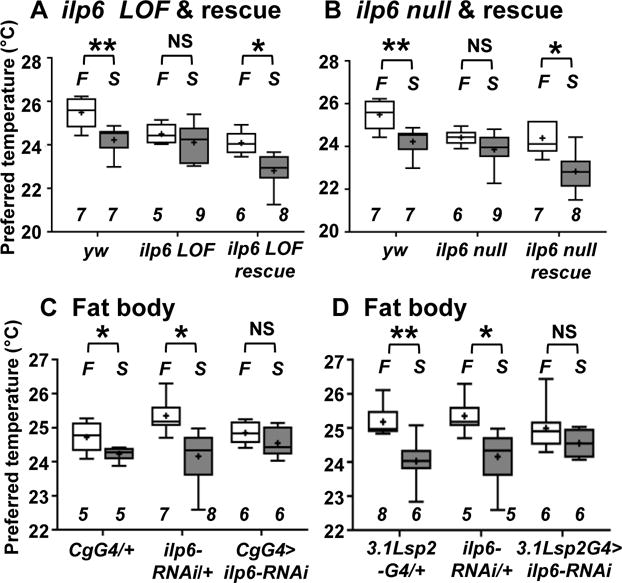

On the other hand, we found that starved ilp6 mutant flies (ilp6 loss-of-function (ilp6 LOF) and ilp6 null mutants) [15, 16] preferred a temperature similar to that of the fed flies (Figure 2A and 2B). Ilp6 is secreted from the fat body and glial cells [17–20] and is known to be upregulated in the fat body in starved larvae [16] and starved adult flies [21]. Therefore, we sought to determine whether Ilp6 in the fat body is required for the starvation-induced reduction in Tp (Figure 2C and 2D). We found that the Tp of flies subjected to RNAi knockdown of ilp6 in the fat body using fat body-specific Gal4s (3.1Lsp2-Gal4 or Cg-Gal4) [22, 23] was similar in fed and starved conditions, suggesting that Ilp6 in the fat body is necessary for the starvation-induced reduction in Tp. Furthermore, to examine whether ilp6 expression in the fat body is sufficient for the starvation-induced reduction in Tp, ilp6 was expressed in the fat body using Cg-Gal4 in ilp6 mutants. We found that ilp6 expression in the fat body restored the starvation-induced reduction in Tp (Figure 2A and 2B). Thus, we conclude that Ilp6 in the fat body is necessary and sufficient for the starvation-induced reduction in Tp.

Figure 2. Ilp6 in the fat body is necessary and sufficient for regulation of the starvation-induced reduction in Tp.

Comparison of Tp between fed (F: fed, white box) and starved overnight (S: starved O/N, gray box) conditions in the groups of flies indicated below.

(A) yw (control), ilp6 loss-of-function (LOF) (ilp6 LOF) and ilp6 LOF rescue (ilp6 LOF; Cg-Gal4/uas-ilp6) flies, in which ilp6 is expressed in the fat body using Cg-Gal4 in the ilp6 LOF mutant background. Whiskers show the minimum-maximum data range of Tp, and boxes show the 25–75th percentile data range of Tp. A horizontal line and a cross in each box represent the median and mean, respectively. Italicized numbers indicate the number of trials. A t-test was performed to compare Tp under fed and starved conditions in each genotype. The behavioral experiments performed at ZT 1–3, 4–6, 7–9 and 10–12 are shown in Figure S2B.

(B) yw (control), ilp6 null and ilp6 null rescue (ilp6 null; Cg-Gal4/uas-ilp6) flies, in which ilp6 is expressed in the fat body using Cg-Gal4 in the ilp6 null mutant background. In the fed condition, the Tp of both ilp6 LOF and ilp6 null flies was lower than that of yw flies, however, it did not differ from that of the rescued flies (Table S1).

(C) RNAi knockdown of ilp6 in the fat body: CgG4/+ (Cg-Gal4/+), ilp6-RNAi/+ (uas-ilp6-RNAi/+) and CgG4> ilp6-RNAi (Cg-Gal4/uas-ilp6-RNAi) flies.

(D) RNAi knockdown of ilp6 in the fat body: 3.1Lsp2G4/+ (3.1Lsp2-Gal4/+), ilp6-RNAi/+ and 3.1Lsp2G4> ilp6-RNAi (uas-ilp6-RNAi/+; 3.1Lsp2-Gal4/+) flies.

The plotting pattern and statistical analysis are the same as in Figure 2A. *p<0.05. **p<0.01. NS indicates no significance. See also Figure S2, S3, Table S1 and S2.

Notably, since Ilp6 is not the only signal expressed in the fat body [7], we focused on the leptin ortholog Unpaired 2 (Upd2) and adipokinetic hormone (AKH) (Figure S3A and B). However, our data suggest that neither Upd2 nor AKH is involved in the starvation-induced reduction in Tp.

ACs are responsible for the starvation-induced reduction in Tp

Temperature preference behavior is controlled by the ACs [4], which are located near the brain surface where the antennal nerves enter the brain and respond to warm temperatures > ~25 °C via TrpA1 [4, 24]. The strong loss-of-function mutant TrpA1ins [4] cannot avoid from warm temperature due to the lack of TrpA1, resulting in a preference for a warmer temperature (~29 °C) [4]. To confirm the importance of ACs in temperature preference behavior, TrpA1-cDNA was expressed in ACs using TrpA1SH-Gal4 (an AC driver) [4]. We found that the normal temperature preference phenotype (~24 °C) was restored in the flies (Figure S4A), suggesting that TrpA1 in ACs is sufficient for controlling temperature preference behavior. Therefore, these data, together with the previous data [4], indicate that ACs are key neurons regulating temperature preference behavior.

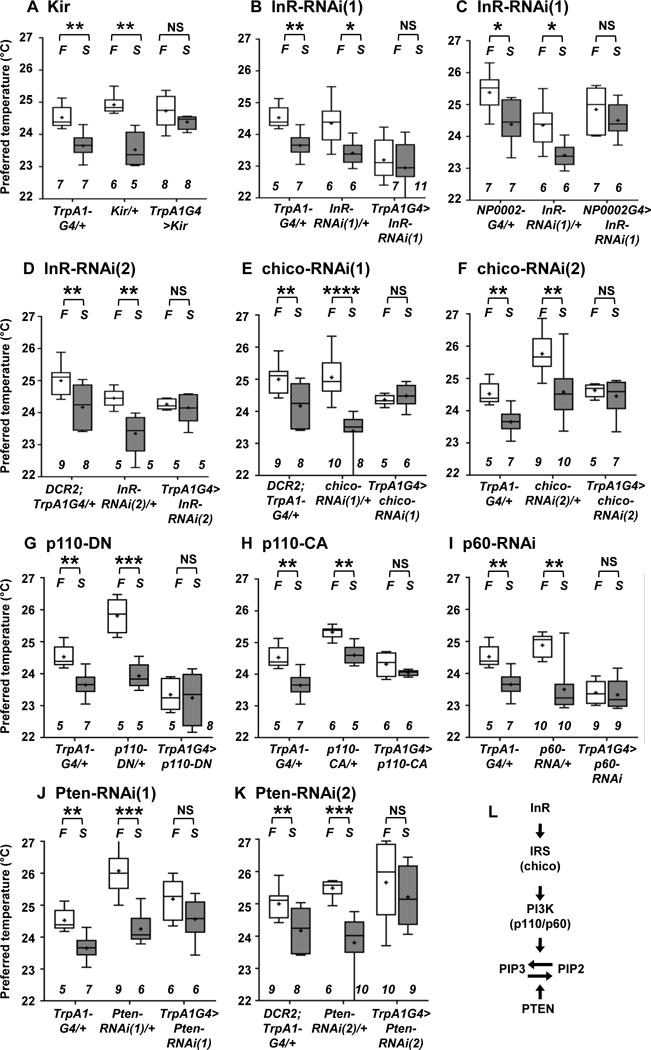

To examine whether ACs are important for the starvation-induced reduction in Tp, we inhibited the activity of ACs using the inwardly rectifying potassium channel (Kir2.1) and compared the Tp of these flies in fed and starved conditions. We found that the Tp of flies in which AC activity was inhibited (TrpA1G4>Kir) was similar in both fed and starved conditions (Figure 3A), suggesting that ACs are required for the starvation-induced reduction in Tp.

Figure 3. InR and its downstream pathways in ACs are important for the starvation-induced reduction in Tp.

Comparison of Tp between the fed (F: fed, white box) and starved overnight (S: starved O/N, gray box) conditions in the groups of flies indicated below.

(A) Inhibition of ACs by Kir expression: TrpA1G4/+, Kir/+ (UAS-Kir/+) and TrpA1G4>Kir (TrpA1SH-Gal4/+; UAS-Kir/+) flies. AC-inhibited flies still avoided warm temperatures and preferred a temperature of ~25 °C in fed conditions (white box). These data suggest that ACs may not be the only neurons that regulate warmth-avoidance behavior and that other redundant temperature-sensing mechanisms could contribute to this warm avoidance phenotype under the conditions applied in the present study. Given that ACs are responsible for the starvation-induced reduction in Tp, ACs represent the critical thermosensor for setting a new homeostatic set-point in starved conditions but might not be sole regulator of the warmth-avoidance phenotype.

(B) RNAi knockdown of InR in ACs: TrpA1G4/+, InR-RNAi(1)/+ (UAS- InR-RNAi(1)/+) and TrpA1G4>InR-RNAi(1) (TrpA1SH-Gal4/UAS-InR-RNAi(1)) flies.

(C) RNAi knockdown of InR in ACs: NP0002/+ (NP0002-Gal4/+), InR-RNAi(1)/+ (UAS- InR-RNAi(1)/+) and NP0002>InR-RNAi(1) (NP0002-Gal4/UAS-InR-RNAi(1)) flies.

(D) RNAi knockdown of InR in ACs: DCR2; TrpA1G4/+ (uas-DCR2/+; TrpA1SH-Gal4/+), InR-RNAi(2)/+ (uas-InR-RNAi(2)/+) and DCR2; TrpA1G4> InR-RNAi(2) (uas-DCR2/+; TrpA1SH-Gal4/+; uas-InR-RNAi(2)/+) flies. InR-RNAi(1) and InR-RNAi(2) are different RNAi lines targeting different regions of the InR sequence.

(E) RNAi knockdown of chico in ACs: DCR2; TrpA1G4/+, chico-RNAi(1)/+ (uas-chico-RNAi(1)/+) and TrpA1G4> chico-RNAi(1) (uas-DCR2/+; TrpA1SH-Gal4/+; uas-chico-RNAi(1)/+) flies.

(F) RNAi knockdown of chico in ACs: TrpA1G4/+, chico-RNAi(2)/+ (uas-chico-RNAi(2)/+) and TrpA1G4> chico-RNAi(2) (TrpA1SH-Gal4/uas-chico-RNAi(2)) flies. chico-RNAi(1) and chico-RNAi(2) are different RNAi lines targeting different regions of the chico sequence.

(G) Expression of a dominant-negative form of p110 (p110-DN) in ACs: TrpA1G4/+, p110-DN/+ (uas-p110-DN/+) and TrpA1G4>p110-DN (TrpA1SH-Gal4/uas-p110-DN) flies. DN means a dominant-negative form of p110.

(H) Expression of a constitutive active form of p110 (p110-CA) in ACs: TrpA1G4/+, p110-CA/+ (uas-p110-CA/+) and TrpA1G4>p110-CA (uas-p110-CA/+; TrpA1SH-Gal4/+) flies. CA means a constitutive active form of p110.

(I) RNAi knockdown of p60 in ACs: TrpA1G4/+, p60-RNAi/+ (uas-p60-RNAi/+) and TrpA1G4>p60-RNAi (TrpA1SH-Gal4/uas-p60-RNAi) flies.

(J) RNAi knockdown of Pten in ACs: TrpA1G4/+, Pten-RNAi (1)/+ (uas-Pten-RNAi(1)/+) and TrpA1G4>Pten-RNAi (1) (TrpA1SH-Gal4/uas-Pten-RNAi(1)) flies.

(K) RNAi knockdown of Pten in ACs: TrpA1G4/+, Pten-RNAi(2)/+ (uas-Pten-RNAi(2)/+) and TrpA1G4> Pten-RNAi(1) (uas-DCR2/+; TrpA1SH-Gal4/+; uas-Pten-RNAi(2)/+) flies. Pten-RNAi(1) and Pten-RNAi(2) are different RNAi lines targeting different regions of the Pten sequence.

(L) A schematic diagram of IIS.

The plotting pattern and statistical analysis are the same as in Figure 2A. *p<0.05. **p<0.01. ***p<0.001. ****p<0.0001. NS indicates no significance. See also Figure S4, Table S1 and S2.

Furthermore, because temperature preference behavior is mediated not only by warm-sensing pathways but also by cold-sensing pathways [4, 25], cold-sensing neurons might also play a role in the starvation-induced reduction in Tp. To examine this possibility, we inhibited cold-sensing neurons with Kir2.1 using R11F02-Gal4 (a cold neuron driver) (Figure S4B and S4C). R11F02-Gal4 is expressed in Dorsal Organ Cool Cells, which respond to decreases in temperatures in larvae [26, 27]. We found that R11F02-Gal4 cold-sensing neurons are also required for the cold avoidance phenotype in adults (Figure S4B). However, fed and starved flies in which the R11F02-Gal4 neurons were inhibited were still capable of preferring different temperatures (Figure S4C), suggesting that R11F02-Gal4 cold-sensing neurons are not required for the regulation of the starvation-induced reduction in Tp. Together, these data suggest that ACs, but not R11F02-Gal4 cold-sensing neurons, are required for the starvation-induced reduction in Tp.

IIS in ACs is necessary for the starvation-induced reduction in Tp

Because we showed that Ilp6 in the fat body was responsible for the starvation-induced reduction in Tp (Figure 2) and that ACs were required for this reduction (Figure 3A), we further asked whether the receptor for Ilp6, the Insulin-like receptor (InR), in ACs is involved in regulating the starvation-induced reduction in Tp. First, we performed RNAi knockdown of InR in ACs using TrpA1SH-Gal4 and another ACs-specific Gal4 line, NP0002-Gal4 (Figure 3B and C) [28]. To ensure the phenotype, we used two independent RNAi lines whose targets are different regions of InR mRNA. We found that the Tp of flies subjected to RNAi knockdown of InR in ACs was similar in fed and starved conditions (Figure 3D), indicating that InR in ACs is required for the starvation-induced reduction in Tp.

Next, we asked whether IIS in ACs is important for the starvation-induced reduction in Tp (Figure 3L). We focused on components of IIS: insulin receptor substrate (IRS: referred to as chico), phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K: referred to as p110/p60) and phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) (Figure 3E–K). We found that the Tp of flies subjected to RNAi knockdown of chico, p60 or Pten in ACs was similar in fed and starved conditions and that the Tp of flies expressing a dominant-negative form (p110-DN) or a constitutive-active form (p110-CA) of p110 in ACs was similar in fed and starved conditions (Figure 3E–K). However, control flies (TrpA1SH-Gal4/+, uas-p110-DN/+, uas-p110-CA/+ and each UAS-RNAi fly line) exhibited the starvation-induced reduction in Tp. Thus, these data suggest that IIS in ACs plays an important role in the starvation-induced reduction in Tp.

Starvation causes ACs to respond to lower temperatures

Because starvation modulates olfactory neurons or secondary taste neurons [29–31], we reasoned that starvation might cause a reduction in the responding temperature of ACs, resulting in a lower Tp. To investigate this possibility, a calcium indicator, GCaMP3.0 [32, 33], was expressed in ACs using TrpA1SH-Gal4, causing Ca2+ influx upon neuronal activation. Intracellular Ca2+ then binds to calmodulin-conjugated GFP, resulting in increased GFP fluorescence. While we found that GCaMP fluorescence (ΔF/F) in ACs peaked at 24.5 °C in the normally fed flies (Figure 4A and G), it peaked at a temperature ~2 °C lower in the starved flies (Figure 4B and G). However, the amplitude of GCaMP fluorescence (ΔF/F) at the peak points was not different between the fed and starved flies (Figure 4H). Therefore, these data suggest that starvation lowers the responding temperature of ACs but does not cause a change in the intensity of the Ca2+ influx. Because the activity of TrpA1 has recently been suggested to depend on the rate of the temperature increase (dT/dt) [34], we also assessed the rates of the temperature increase and confirmed that they were consistent between fed and starved flies (Figure 4I). The data suggest that starvation causes ACs to respond to lower temperatures.

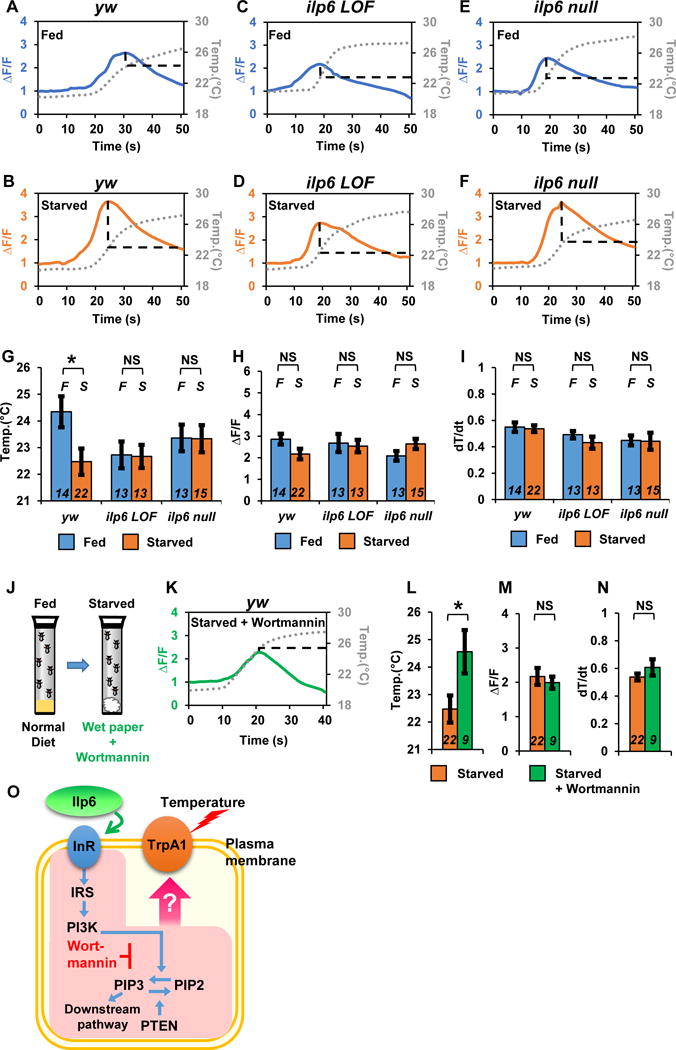

Figure 4. Ilp6 is important for resetting the responding temperature in ACs.

(A–F) Representative profiles of the changes in GCaMP fluorescence in ACs under fed (A, C and E, blue-colored line) and starved (B, D and F, orange-colored line) conditions using yw; TrpA1SH-Gal4, UAS-GCaMP3.0 (yw (control); A and B), ilp6 LOF (C and D) and ilp6 null (E and F) flies. The temperature ramp is shown with gray dotted lines. F indicates the averaged basal fluorescence signal before warm-temperature stimulation. ΔF/F is the change in GCaMP fluorescence relative to the basal level of fluorescence.

(G–I) Mean temperature (G) and mean ΔF/F (H) at peak points and mean dT/dt (I). Blue- and orange-colored bars indicate fed and starvation conditions, respectively. Italicized F and S indicate fed and starvation conditions, respectively. Italicized numbers indicate the number of trials. A t-test was utilized to compare the raw data between the fed and starvation conditions. *p<0.05. NS indicates no significance. Error bars indicate sem.

(J) Schematic representation of the experimental conditions for Wortmannin treatment. Fed flies were starved with Wortmannin overnight, and GCaMP fluorescence was then examined.

(K) Representative profiles of changes in GCaMP fluorescence in the ACs of TrpA1SH-Gal4, UAS-GCaMP3.0 flies under starved plus Wortmannin conditions (B, green line). The temperature ramp is shown with gray dotted lines.

(L–N) Mean temperature (L) and mean ΔF/F (M) at peak points as well as the mean dT/dt (N). The same data from starved conditions (orange-colored bars) employed in Figure 5G–5I are used. *p<0.05. NS indicates no significance. Error bars indicate sem.

(O) A schematic diagram of IIS and the inhibition of PI3K activity by Wortmannin. Wortmannin blocks phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) activity [35]. Starvation causes an increase in ilp6 expression in the fat body [21]. See also Table S2.

IIS modulates the responding temperature of ACs upon starvation

Given that Ilp6 in the fat body is important for the starvation-induced reduction in Tp (Figure 2), Ilp6 might influence the responding temperatures of ACs upon starvation. To examine this possibility, we compared the temperature at which ACs exhibited peak for GCaMP fluorescence in ilp6 LOF and ilp6 null mutants in fed and starved conditions. We found that in the ilp6 mutants, the responding temperatures of the ACs were similar between fed and starved conditions (Figure 4C–F and G). Neither the fluorescence intensity (Figure 4H) nor the rate of temperature increase (Figure 4I) in the flies was significantly different. The data indicate that Ilp6 is necessary for the starvation-induced temperature response in ACs.

We further used a PI3K inhibitor, Wortmannin (Figure 4O) [35]. Because starvation modulates IIS, we reasoned that inhibition of IIS by Wortmannin might prevent the change in AC temperature sensitivity upon starvation. When the flies were starved and provided only with water, the responding temperature of the ACs was ~22.5 °C (Figure 4B, G and L). However, when the flies were starved but provided with both water and Wortmannin (Figure 4J), the responding temperature of the ACs increased to ~24.5 °C (Figure 4K and L). The data suggest that inhibition of IIS prevents the change in AC temperature sensitivity upon starvation. Again, neither the fluorescence intensity (Figure 4M) nor the rate of temperature increase (Figure 4N) in the flies was significantly different. Therefore, our data suggest that IIS is important for modulating the temperature response of ACs upon starvation.

DISCUSSION

Here, we first demonstrated that starvation causes a reduction in Tp in Drosophila that parallels starvation-induced hypothermia in mammals, suggesting that internal nutrient conditions dramatically influence the body temperature of both flies and mammals.

How is Ilp6 distinguished from other Ilps in the regulation of the starvation-induced reduction in Tp?

Our data suggest that Ilp6 is responsible for conveying hunger information to ACs. That said, there are other Ilps that can activate InR, and how Ilp6 is distinguished from other Ilps and regulates the starvation-induced reduction in Tp is therefore mystery. Ilp2 is the major Ilp and its expression level accounts for 80% of all ilp expression in the head [36]. In nutrient-poor conditions, ilp2, ilp3, and ilp5 expression either shows no change or is downregulated [18, 37–39] whereas ilp6 mRNA in the fat body is upregulated. Overexpressing ilp6 in the fat body causes lower expression of ilp2 mRNA and ilp5 mRNA in the brain [21]. Interestingly, in the ilp2, ilp3, ilp5 triple mutant, ilp6 mRNA in the body is upregulated [15]. Therefore, although it is still unclear how increasing Ilp6 can affect InR signaling in ACs, we speculate that the higher expression level of ilp6 might be important in the control of the starvation-induced reduction in Tp.

Given that starvation modulates olfactory and gustatory behaviors via olfactory neurons and secondary taste neurons [29–31] and that InR is involved in the starvation-dependent modulation of the olfactory neurons [29], it is of interest to investigate whether Ilp6 is also involved in the starvation-dependent modulation of olfactory or taste behavior. Further characterization of the function of Ilp6 in different sensory systems will shed a new light on how and whether the Ilps-InR system contribute to starvation-dependent sensory modulation.

How can IIS modulate the temperature response in ACs under starvation?

Because TrpA1 plays a role in the warm response of ACs [6], IIS downstream signaling may modulate the temperature response of TrpA1 under starvation (Figure 4O). The downstream effects of IIS results in PI3K phosphorylating phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) to generate phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-triphosphate (PIP3). PIP2 and PIP3 function not only in many cellular processes, such as membrane trafficking, the membrane/cytoskeletal interface, and cell signaling, but also in modulating several K+ and Ca2+ channels [40], including mammalian TrpA1 or TrpV1 channels [41–43]. Therefore, the pathways downstream of IIS might change the responding temperature of TrpA1 in ACs under starvation (Figure 4O). It is important to note that, in the fed condition, when InR, PI3K (p110 or p60) were constitutively inhibited, actual Tp was lower than in control flies (Gal4 or UAS controls) (Figure 3B, G, and I, Table S1). However, in the rest of the data (Figure 3C, D, E, F, H, J, and K), IIS manipulation did not change the actual Tp, although the differential Tp between fed and starved flies was blunted. Therefore, the actual Tp. regulation is unlikely controlled by the same pathway which regulates starvation-induced reduction in Tp.

Additionally, changes in PIP2 and PIP3 levels might not be the only causes of the starvation-induced reduction in Tp. Several reports have shown that Ca2+ cations, calmodulin and calmodulin kinases also modulate TRP channel activity [44, 45]. Therefore, the variation of Ca2+ levels in ACs might modulate the responding temperature under starved conditions. It is still unclear how starvation changes the temperature response in ACs; the second messengers in the IIS pathway and Ca2+ levels are two potential mechanisms that may be responsible for the starvation-induced reduction in Tp.

Tp might be modulated by different diets or sensory cues

We showed that sugar is one of the critical nutrients for the starvation-induced reduction in Tp. However, since fly food also contains proteins and other nutrients, sugar may not be the only nutrient that contributes to the modulation of Tp. In fact, as a recent paper suggests that the activation of neural circuits controlling protein hunger inhibits sugar consumption [46]. Hence, dietary proteins may also directly or indirectly influence the starvation-induced reduction in Tp.

Metabolism is associated with numerous physiological responses, including the regulation of body temperature, and starved flies have been shown to prefer “nutritive” sugar over non-nutritive sugar [47]. Therefore, it was reasonable to find that the starvation-induced reduction in Tp was restored in flies that consumed nutritive sugar (Figure 1C). However, emerging evidence suggests that non-nutritive sugar intake can influence several behavioral phenotypes [48, 49]. Therefore, it is of interest to examine whether non-nutritive sugar intake modulates Tp. In this case, olfactory or gustatory cues likely influence these behaviors. Elucidation of the underlying mechanisms will be important for understating diet- or sensory-dependent thermoregulation.

Starvation does not disrupt the fluctuation of Tp during the day

Tp fluctuates over the course of the day, which is controlled by the circadian clock [50]. Tp increases during the daytime and decreases at night, and this phenotype is referred to as the temperature preference rhythm (TPR), which is a similar phenomenon to mammalian body temperature rhythms (BTR) [50]. We found that a rhythmic Tp was sustained in starved w1118 flies (Figure S1B) and ilp6 mutant flies (Figure S2B), indicating that starvation does not disrupt the rhythmic Tp. Interestingly, starvation also does not disrupt the mammal BTR [2]. Thus, circadian oscillation is too robust to be disrupted by the feeding state in both mammals and flies.

Reduction of body temperature is a strategy for survival in a nutrient-scarce environment

Under nutrient-poor conditions, animals need to save their energy by adjusting their behaviors and physiology for survival. In mammals, starvation dramatically lowers metabolism and body temperature [1, 2]. Although body temperature is controlled differently in mammals and flies, starvation-induced hypothermia appears to be a common feature. Given that the metabolic rate of flies is lower at 18 °C than at 25 °C and the surrounding temperature strongly influences the metabolic rate [51, 52], a lower Tp could also cause a reduction in metabolic rates. Several studies show that starvation causes a lower Tp in ectotherms such as mosquitoes, cockroaches, and rainbow trout [10]. Therefore, a starvation-induced reduction in body temperature may be a survival strategy in both ectotherms and endotherms when there is a food shortage.

Interestingly, it has recently been shown in mice that the IGF1 receptor in the central nervous system is involved in the regulation of body temperature under caloric restriction [53]. Given that Drosophila Ilp6 is functionally and structurally similar to IGFs [16, 18], the mechanism underlying the starvation-induced reduction in body temperature may be evolutionarily conserved in these animal species.

Star Methods

Contact for Reagent and Resource Sharing

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Fumika Hamada (fumika.hamada@cchmc.org).

Experimental Model and Subject Details

All flies were raised under a 12 h-light/12 h-dark (LD) cycle at 25 °C in an incubator (DRoS33SD, Powers Scientific Inc.) with an electric timer. w1118 and yellow white (yw) flies were used as control flies. 3.1Lsp2-Gal4 was provided by Dr. Brigitte Dauwalder [23]. yw; uas-ilp6 (II) was provided by Dr. Ernst Hafen [37]. TrpA1SH-Gal4 and TrpA1ins were provided by Dr. Paul A. Garrity [4]. NP0002-Gal4 was provided by Kyoto DGRC [28]. Other flies were provided by the Bloomington Drosophila fly stock center. The information for all fly lines is described in the Key Resources Table.

Method details

Temperature preference behavioral assay

The temperature preference behavioral assays were examined using a gradient of temperatures, ranging from 18–32°C and were performed for 30 min in an environmental room maintained at 25 °C/65–70% RH [54]. A total of 30–40 flies were used for one trial, and the flies were never reused. The one exception was that 50–60 flies were used for the experiments using ilp2–3,5−/− triple mutant flies, due to their small body size, they often climbed on the wall and ceiling, which resulted in fewer flies in the arena. Control and experimental trials were performed in parallel or independently. The behavioral assays were performed at Zeitgeber time (ZT) 4–7 (Light on is defined as ZT0), and starvation was initiated at ZT 10 (starved for 18–21 hr), except in Figure 1C, where the behavioral assays were performed during ZT 1–3, and starvation was initiated at ZT 8 (starved for 18–20 hr). The flies were reared on our normal fly food, with the following composition per 1 L of food: 6.0 g sucrose, 7.3 g agar, 44.6 g cornmeal, 22.3 g yeast and 16.3 mL molasses. For the starvation assays, the collected flies were maintained in plastic vials with 3 mL of distilled water, absorbed by a Kimwipe.

GCaMP imaging

Calcium imaging was performed in yw; TrpA1SH-Gal4, uas-GCamp3.0, yw, ilp6 LOF; TrpA1SH-Gal4, uas-GCamp3.0 and yw, ilp6 null; and TrpA1SH-Gal4, uas-GCamp3.0 flies. TrpA1SH-Gal4 drove the expression of the GCaMP calcium indicator in ACs. GCaMP imaging was performed from ZT 4–7, which corresponded to the same times as the behavioral assays.

Fly brains were dissected in oxygenized modified solution F (5 mM HEPES, 115 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 6 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 4 mM NaHCO3, 5 mM trehalose, 10 mM glucose, 65 mM sucrose, pH 7.5)[55]. This solution was also utilized as the bath solution. A platinum-wired holder held the dissected brain in the bath [56]. The prepared brain samples, together with the holder, were mounted on a laminar flow perfusion chamber beneath the ×40 water immersion objective of a fixed-stage upright microscope (Zeiss Axio Examiner. Z1). For better accessibility, the brain was placed face up to acquire AC signals. The fluorescence signal was continuously monitored for at least 40 s.

Optical images of the preparation were acquired using a digital CCD camera (C10600-10B-H; Hamamatsu) with a 512 × 512-pixel resolution. The data from each image were digitized and analyzed using AxonVision 4.9.1 (Zeiss).

Pharmacology

Wortmannin (LC Laboratories, Woburn, MA) was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) (Sigma) at a 10-mM stock concentration [57]. Flies were fed 996 μL of distilled water plus 4 μL of Wortmannin solution (final concentration, 40 μM) for 18–21 hr at night (overnight), which was the same as the duration of starvation, and were then used for Ca2+ imaging assays.

Quantification and Statistical Analysis

Temperature preference behavior data analysis

After the 30-min behavioral assay, the number of flies whose bodies were completely located on the apparatus were counted. Flies whose bodies were partially or completely located on the walls of the apparatus cover were not included in the data analysis. The percentage of flies within each one-degree temperature interval on the apparatus was calculated by dividing the number of flies within each one-degree interval by the total number of flies on the apparatus. The location of each one-degree interval was determined by measuring the temperature at 6 different points on the bottom of the apparatus. Data points were plotted as the percentage of flies within a one-degree temperature interval. The weighted mean of Tp was calculated by totaling the product of the percentage of flies within a one-degree temperature interval and the corresponding temperature (e.g., fractional number of flies × 17.5 °C + fractional number of flies × 19.5 °C +……… fractional number of flies × 32.5 °C). If the SEM of the averaged Tp was not <0.3 after the five trials, we performed additional trials until the SEM reached < 0.3.

GCaMP imaging data analaysis

The mean fluorescence intensity of the monitored neuron was calculated for each frame. Concurrently, the background fluorescence (calculated from the average fluorescence of at least two chosen non-GCaMP-expressing areas) was subtracted from the mean fluorescence intensity of the regions of interest for each frame. Background-subtracted values were then expressed as the percentage ΔF/F, where F is the mean fluorescence intensity before activation.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism (Ver. 7.02) and Microsoft Excel. The Shapiro-Wilk test was employed to test normality (α=0.05). The t-test was used to compare mean values. Kruskal-Wallis test and the post hoc test (Dunn’s test) were employed to compare multiple groups as a non-parametric test. One-way ANOVA and post hoc tests (Tukey-Kramer and Dunnett’s tests) were used to compare multiple groups.

KEY RESOURCES TABLE

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Chemicals, Peptides, and Recombinant Proteins | ||

| Wortmannin | LC Laboratories |

W-2990 [35] |

| Dimethyl sulfoxide | Sigma | D8418 |

| HEPES | Sigma | H3375 |

| NaCl | Fisher scientific |

BP358-10 |

| KCl | Fisher scientific | BP366-500 |

| CaCl2 | Sigma | C7902 |

| MgCl2 | Fisher scientific |

BP214-500 |

| NaHCO3 | Sigma | S5761 |

| Trehalose | Acros organics |

182550250 |

| Glucose | Sigma | G6152 |

| Sucrose | Sigma | S0389 |

| Fructose | AMRESCO | 0226-2.5KG |

| Lactose | Sigma | L3625 |

| Corn meal | Aunt Jemima | Yellow corn meal http://www.auntjemima.com/products/other_products/yellow_corn_meal |

| Yeast | Red star | Red star Active Dry Yeast http://redstaryeast.com/products/red-star/red-star-active-dry-yeast/ |

| Agar | Global Bioingredients |

Agarmex AN-160452 http://globalbioingredients.com/ |

| Morasses | Barkman Honey |

http://www.barkmanhoney.com/products/other-sweeteners/molasses/ |

| Sucrose (used for fly food) | Supreckels | Supreckels granuate pure sugar 50lbs |

| Propionic acid | Acros organics |

14930-0025 |

| Tegosept | Genesee scientific |

20-259 |

| Experimental Models: Organisms/Strains | ||

| D. melanogaster | ||

| w1118 | Bloomington | BDSC_5905 |

| yw | N/A | |

| TrpA1SH-Gal4 | Garrity Lab | N/A [4] |

| TrpA1ins | Garrity Lab | N/A [4] |

| uas-TrpA1 | Garrity Lab | N/A [4] |

| uas-Kir2.1 | N/A [58] | |

| uas-GCaMP3.0 | Bloomington | BDSC_52231 [32, 33] |

| ilp6 LOF | Bloomington | BDSC_30885 [15, 16] |

| ilp6 null | Bloomington | BDSC_30886 [15, 16] |

| Cg-Gal4 | Bloomington | BDSC_7011 [22] |

| 3.1Lsp2-Gal4 | Dawalder lab | N/A [23] |

| uas-DCR2 (on X) | Bloomington | BDSC_24644 |

| uas-ilp6-RNAi | TRiP, Bloomington | BDSC_33684 |

| uas-ilp6 (on II) | Hafen Lab | N/A [37] |

| uas-InR-RNAi(1) | TRiP, Bloomington | BDSC_51518 |

| uas-InR-RNAi(2) | TRiP, Bloomington | BDSC_31037 |

| NP0002-Gal4 | NP line, DGRC | DGRC_112002 [28] |

| uas-chico-RNAi(1) | TRiP, Bloomington | BDSC_28329 |

| uas-chico-RNAi(2) | TRiP, Bloomington | BDSC_36665 |

| uas-p110-CA (on X) | Bloomington | BDSC_8294 |

| uas-p110-DN (on II) | Bloomington | BDSC_8289 |

| uas-p60-RNAi | TRiP, Bloomington | BDSC_38991 |

| uas-Pten-RNAi(1) | TRiP, Bloomington | BDSC_33643 |

| uas-Pten-RNAi(2) | TRiP, Bloomington | BDSC_25967 |

| ilp1−/− | Bloomington | BDSC_30880 [15] |

| ilp2−/− | Bloomington | BDSC_30881 [15] |

| ilp3−/− | Bloomington | BDSC_30882 [15] |

| ilp4−/− | Bloomington | BDSC_30883 [15] |

| ilp5−/− | Bloomington | BDSC_30884 [15] |

| ilp7−/− | Bloomington | BDSC_30887 [15] |

| ilp2-3,5−/− | Bloomington | BDSC_30889 [15] |

| R11F02-Gal4 | Bloomington | BDSC_49828 [26, 27] |

| upd2Δ | Bloomington | BDSC_55727 |

| Akh-Gal4 (on II) | Bloomington | BDSC_25683 |

| Software and Algorithms | ||

| Microsoft Excel | Microsoft | https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/download/details.aspx?id=10 |

| Graphpad Prism (v 7.02) | Graphpad Software | https://www.graphpad.com/ |

| ZEISS AxioVision 4.9.1 | ZEISS | https://www.zeiss.com/microscopy/int/products/microscope-software/axiovision.html |

Supplementary Material

HIGHLIGHTS.

Starvation causes a lower preferred temperature (Tp) in Drosophila.

Ilp6 in the fat body is responsible for the starvation-induced reduction in Tp.

Insulin signaling in ACs is important for the starvation-induced reduction in Tp.

Starvation results in a reduction in the responding temperature of ACs.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Drs. Brigitte Dauwalder, Ernst Hafen and Paul A. Garrity as well as Kyoto DGRC and the Bloomington Drosophila fly stock center for the fly lines. We thank Drs. Jun Ma, Christina Gross, KyeongJin Kang and Piali Sengupta as well as the members of the Hamada laboratory for their critical comments and advice on the manuscript, Dr. Richard A. Lang and his laboratory members for their comments and kind sharing of reagents, Mr. Matthew Batie for constructing the behavioral testing apparatuses, and Drs. Takahisa Nakamura, Ryusuke Niwa, Yuko Niwa-Shimada, Taishi Yoshii and Kenji Tomioka for their critical advice. This research was supported by a Trustee Grant and RIP funding from Cincinnati Children’s Hospital, JST (Japan Science and Technology)/Precursory Research for Embryonic Science and Technology (PRESTO), the March of Dimes, and NIH R01 grant GM107582 to F. N. H.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributions

F.N.H and Y.U designed the experiments. Y.U. performed the GCaMP imaging assays. Y.U, S.E.H, M.L.C, H.W.S and P.S. performed the temperature preference behavioral assays. F.N.H and Y.U wrote the manuscript.

Declaration of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests

References

- 1.Keys A, Brožek J, Henschel A, Mickelsen O, Taylor HL. The Biology of Human Starvation. University of Minnesota Press 1950 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Piccione G, Caola G, Refinetti R. Circadian modulation of starvation-induced hypothermia in sheep and goats. Chronobiology international. 2002;19:531–541. doi: 10.1081/cbi-120004225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sayeed O, Benzer S. Behavioral genetics of thermosensation and hygrosensation in Drosophila. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1996;93:6079–6084. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.12.6079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hamada FN, Rosenzweig M, Kang K, Pulver SR, Ghezzi A, Jegla TJ, Garrity PA. An internal thermal sensor controlling temperature preference in Drosophila. Nature. 2008;454:217–220. doi: 10.1038/nature07001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nassel DR, Kubrak OI, Liu Y, Luo J, Lushchak OV. Factors that regulate insulin producing cells and their output in Drosophila. Frontiers in physiology. 2013;4:252. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2013.00252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Teleman AA. Molecular mechanisms of metabolic regulation by insulin in Drosophila. Biochem J. 2009;425:13–26. doi: 10.1042/BJ20091181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pool AH, Scott K. Feeding regulation in Drosophila. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2014;29:57–63. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2014.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stevenson RD. Body size and limits to the daily range of body temperature in terrestrial ectotherms. Am Nat. 1985:102–117. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stevenson RD. The relative importance of behavioral and physiological adjustments controlling body temperature in terrestrial ectotherms. The American Naturalist. 1985;126 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dillon ME, Wang G, Garrity PA, Huey RB. Review: Thermal preference in Drosophila. J Therm Biol. 2009;34:109–119. doi: 10.1016/j.jtherbio.2008.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schnuch M, Seebauer H. Sugar cell responses to lactose and sucrose in labellar and tarsal taste hairs of Musca domestica. J Comp Physiol A. 1998;182:767–775. doi: 10.1007/s003590050221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cohen AL. Insect Diets: Science and Technology. Second. CRC Press; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Owusu-Ansah E, Perrimon N. Modeling metabolic homeostasis and nutrient sensing in Drosophila: implications for aging and metabolic diseases. Dis Model Mech. 2014;7:343–350. doi: 10.1242/dmm.012989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nassel DR, Liu Y, Luo J. Insulin/IGF signaling and its regulation in Drosophila. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 2015;221:255–266. doi: 10.1016/j.ygcen.2014.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gronke S, Clarke DF, Broughton S, Andrews TD, Partridge L. Molecular evolution and functional characterization of Drosophila insulin-like peptides. PLoS genetics. 2010;6:e1000857. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Slaidina M, Delanoue R, Gronke S, Partridge L, Leopold P. A Drosophila insulin-like peptide promotes growth during nonfeeding states. Dev Cell. 2009;17:874–884. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Geminard C, Rulifson EJ, Leopold P. Remote control of insulin secretion by fat cells in Drosophila. Cell Metab. 2009;10:199–207. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Okamoto N, Yamanaka N, Yagi Y, Nishida Y, Kataoka H, O’Connor MB, Mizoguchi A. A fat body-derived IGF-like peptide regulates postfeeding growth in Drosophila. Dev Cell. 2009;17:885–891. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chell JM, Brand AH. Nutrition-responsive glia control exit of neural stem cells from quiescence. Cell. 2010;143:1161–1173. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sousa-Nunes R, Yee LL, Gould AP. Fat cells reactivate quiescent neuroblasts via TOR and glial insulin relays in Drosophila. Nature. 2011;471:508–512. doi: 10.1038/nature09867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bai H, Kang P, Tatar M. Drosophila insulin-like peptide-6 (dilp6) expression from fat body extends lifespan and represses secretion of Drosophila insulin-like peptide-2 from the brain. Aging Cell. 2012;11:978–985. doi: 10.1111/acel.12000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Asha H, Nagy I, Kovacs G, Stetson D, Ando I, Dearolf CR. Analysis of Ras-induced overproliferation in Drosophila hemocytes. Genetics. 2003;163:203–215. doi: 10.1093/genetics/163.1.203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lazareva AA, Roman G, Mattox W, Hardin PE, Dauwalder B. A role for the adult fat body in Drosophila male courtship behavior. PLoS genetics. 2007;3:e16. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Viswanath V, Story GM, Peier AM, Petrus MJ, Lee VM, Hwang SW, Patapoutian A, Jegla T. Opposite thermosensor in fruitfly and mouse. Nature. 2003;423:822–823. doi: 10.1038/423822a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gallio M, Ofstad TA, Macpherson LJ, Wang JW, Zuker CS. The coding of temperature in the Drosophila brain. Cell. 2011;144:614–624. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.01.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Klein M, Afonso B, Vonner AJ, Hernandez-Nunez L, Berck M, Tabone CJ, Kane EA, Pieribone VA, Nitabach MN, Cardona A, et al. Sensory determinants of behavioral dynamics in Drosophila thermotaxis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2015;112:E220–229. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1416212112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ni L, Klein M, Svec KV, Budelli G, Chang EC, Ferrer AJ, Benton R, Samuel AD, Garrity PA. The Ionotropic Receptors IR21a and IR25a mediate cool sensing in Drosophila. Elife. 2016;5 doi: 10.7554/eLife.13254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tang X, Roessingh S, Hayley SE, Chu ML, Tanaka NK, Wolfgang W, Song S, Stanewsky R, Hamada FN. The role of PDF neurons in setting preferred temperature before dawn in Drosophila. Elife. 2017;6 doi: 10.7554/eLife.23206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Root CM, Ko KI, Jafari A, Wang JW. Presynaptic facilitation by neuropeptide signaling mediates odor-driven food search. Cell. 2011;145:133–144. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kain P, Dahanukar A. Secondary taste neurons that convey sweet taste and starvation in the Drosophila brain. Neuron. 2015;85:819–832. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.LeDue EE, Mann K, Koch E, Chu B, Dakin R, Gordon MD. Starvation-Induced Depotentiation of Bitter Taste in Drosophila. Current biology: CB. 2016;26:2854–2861. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2016.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tian L, Hires SA, Mao T, Huber D, Chiappe ME, Chalasani SH, Petreanu L, Akerboom J, McKinney SA, Schreiter ER, et al. Imaging neural activity in worms, flies and mice with improved GCaMP calcium indicators. Nat Methods. 2009;6:875–881. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nakai J, Ohkura M, Imoto K. A high signal-to-noise Ca(2+) probe composed of a single green fluorescent protein. Nat Biotechnol. 2001;19:137–141. doi: 10.1038/84397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Luo J, Shen WL, Montell C. TRPA1 mediates sensation of the rate of temperature change in Drosophila larvae. Nat Neurosci. 2017;20:34–41. doi: 10.1038/nn.4416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Arcaro A, Wymann MP. Wortmannin is a potent phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase inhibitor: the role of phosphatidylinositol 3,4,,5-trisphosphate in neutrophil responses. Biochem J. 1993;296(Pt 2):297–301. doi: 10.1042/bj2960297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Buch S, Melcher C, Bauer M, Katzenberger J, Pankratz MJ. Opposing effects of dietary protein and sugar regulate a transcriptional target of Drosophila insulin-like peptide signaling. Cell Metab. 2008;7:321–332. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ikeya T, Galic M, Belawat P, Nairz K, Hafen E. Nutrient-dependent expression of insulin-like peptides from neuroendocrine cells in the CNS contributes to growth regulation in Drosophila. Current biology: CB. 2002;12:1293–1300. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)01043-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Okamoto N, Nishimura T. Signaling from Glia and Cholinergic Neurons Controls Nutrient-Dependent Production of an Insulin-like Peptide for Drosophila Body Growth. Dev Cell. 2015;35:295–310. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2015.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Colombani J, Raisin S, Pantalacci S, Radimerski T, Montagne J, Leopold P. A nutrient sensor mechanism controls Drosophila growth. Cell. 2003;114:739–749. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00713-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Suh BC, Hille B. PIP2 is a necessary cofactor for ion channel function: how and why? Annu Rev Biophys. 2008;37:175–195. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.37.032807.125859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kim D, Cavanaugh EJ, Simkin D. Inhibition of transient receptor potential A1 channel by phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2008;295:C92–99. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00023.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Karashima Y, Prenen J, Meseguer V, Owsianik G, Voets T, Nilius B. Modulation of the transient receptor potential channel TRPA1 by phosphatidylinositol 4,5-biphosphate manipulators. Pflugers Arch. 2008;457:77–89. doi: 10.1007/s00424-008-0493-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Prescott ED, Julius D. A modular PIP2 binding site as a determinant of capsaicin receptor sensitivity. Science. 2003;300:1284–1288. doi: 10.1126/science.1083646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zurborg S, Yurgionas B, Jira JA, Caspani O, Heppenstall PA. Direct activation of the ion channel TRPA1 by Ca2+ Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:277–279. doi: 10.1038/nn1843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sokabe T, Tsujiuchi S, Kadowaki T, Tominaga M. Drosophila painless is a Ca2+-requiring channel activated by noxious heat. The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2008;28:9929–9938. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2757-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liu Q, Tabuchi M, Liu S, Kodama L, Horiuchi W, Daniels J, Chiu L, Baldoni D, Wu MN. Branch-specific plasticity of a bifunctional dopamine circuit encodes protein hunger. Science. 2017;356:534–539. doi: 10.1126/science.aal3245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dus M, Min S, Keene AC, Lee GY, Suh GS. Taste-independent detection of the caloric content of sugar in Drosophila. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108:11644–11649. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1017096108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Musso PY, Lampin-Saint-Amaux A, Tchenio P, Preat T. Ingestion of artificial sweeteners leads to caloric frustration memory in Drosophila. Nature communications. 2017;8:1803. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-01989-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang QP, Lin YQ, Zhang L, Wilson YA, Oyston LJ, Cotterell J, Qi Y, Khuong TM, Bakhshi N, Planchenault Y, et al. Sucralose Promotes Food Intake through NPY and a Neuronal Fasting Response. Cell Metab. 2016;24:75–90. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kaneko H, Head LM, Ling J, Tang X, Liu Y, Hardin PE, Emery P, Hamada FN. Circadian Rhythm of Temperature Preference and Its Neural Control in Drosophila. Current biology: CB. 2012;22:1851–1857. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Berrigan D, Partridge L. Influence of temperature and activity on the metabolic rate of adult Drosophila melanogaster. Comp Biochem Physiol A Physiol. 1997;118:1301–1307. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9629(97)00030-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schilman PE, Waters JS, Harrison JF, Lighton JR. Effects of temperature on responses to anoxia and oxygen reperfusion in Drosophila melanogaster. The Journal of experimental biology. 2011;214:1271–1275. doi: 10.1242/jeb.052357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cintron-Colon R, Sanchez-Alavez M, Nguyen W, Mori S, Gonzalez-Rivera R, Lien T, Bartfai T, Aid S, Francois JC, Holzenberger M, et al. Insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor regulates hypothermia during calorie restriction. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2017;114:9731–9736. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1617876114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Goda T, Leslie JR, Hamada FN. Design and analysis of temperature preference behavior and its circadian rhythm in Drosophila. Journal of visualized experiments: JoVE. 2014:e51097. doi: 10.3791/51097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ng M, Roorda RD, Lima SQ, Zemelman BV, Morcillo P, Miesenbock G. Transmission of olfactory information between three populations of neurons in the antennal lobe of the fly. Neuron. 2002;36:463–474. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00975-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gu H, O’Dowd DK. Cholinergic synaptic transmission in adult Drosophila Kenyon cells in situ. The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2006;26:265–272. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4109-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ko KI, Root CM, Lindsay SA, Zaninovich OA, Shepherd AK, Wasserman SA, Kim SM, Wang JW. Starvation promotes concerted modulation of appetitive olfactory behavior via parallel neuromodulatory circuits. Elife. 2015;4 doi: 10.7554/eLife.08298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Baines RA, Uhler JP, Thompson A, Sweeney ST, Bate M. Altered electrical properties in Drosophila neurons developing without synaptic transmission. The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2001;21:1523–1531. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-05-01523.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.