Abstract

The study examined sexual delay discounting, or the devaluation of condom-protected sex in the face of delay, as a risk factor for sexually transmitted infection (STI) among college students. Participants (143 females, 117 males) completed the Sexual Delay Discounting Task (SDDT; Johnson & Bruner, 2012) and questionnaires of risky sexual behavior, risk perception, and knowledge. Participants exhibited steeper sexual delay discounting (above and beyond general likelihood of having unprotected sex) when partners were viewed as more desirable or less likely to have a STI, with males demonstrating greater sexual delay discounting than females across most conditions. Importantly, greater self-reported risky sexual behaviors were associated with higher rates of sexual delay discounting, but not with likelihood of using a condom in the absence of delay. These results provide support for considering sexual delay discounting, with particular emphasis on potential delays to condom use, as a risk factor for STI among college students.

Keywords: sexual delay discounting, risky sexual behavior, college students, sexual delay discounting task

Individuals between 15 and 24 years old bear a disproportionate burden of sexually transmitted infections (STI) relative to other age groups. While representing only 27% of the sexually active population, this age group constitutes half of the 19 million who are diagnosed with a STI each year (CDC, 2014; Weinstock, Berman, & Cates et al., 2004; Satterwhite et al., 2013). With thirty percent of total diagnoses detected among college students (Rimsza, 2005), elevated STI incidence rates highlight the need to understand psychological factors related to risky sex in this group in order to guide effective STI prevention efforts.

While an established body of literature strongly supports behavioral (e.g., substance use), and cognitive and affective variables (e.g., attitudes toward condom use) as STI risk factors, the literature on delay discounting as an important variable influencing risky sexual behavior is expanding. Delay discounting, or the degree to which future consequences are devalued as a function of delay, is one such trait-like factor; higher delay discount rates for money (i.e., greater preference for immediate relative to delayed money) are associated with an earlier age of sexual debut (Reimers, Maylor, Stewart, & Chater, 2009), failure to engage in health maintenance behaviors (Bradford, 2010), and substance use behaviors associated with engagement in risky sex (e.g., Yi, Mitchell, & Bickel, 2010; MacKillop, Amlung, Few, et al., 2011). Despite this evidence highlighting the associations between of delay discounting of money and sexual health behaviors, more recent research indicates that delay discounting of clinically-relevant outcomes shows stronger associations with the specific clinical issue (e.g., Hendrickson & Rasmussen, 2013; Rasmussen, Lawyer, & Reilly, 2010).

Accordingly, delay discounting of sex outcomes has been examined previously. Sexual delay discounting tasks have mirrored monetary discounting tasks in that participants have been asked to make choices between smaller-immediate versus larger-delayed durations of sexual encounters (e.g., 3 minutes of sexual activity right now vs. 10 minutes of sexual activity in 1 week; Lawyer & Schoepflin, 2013; Lawyer, Williams, Prihodova, et al., 2010), smaller-immediate versus larger-delayed numbers of sexual encounters (e.g., 3 sexual encounters right now vs. 10 sexual encounters in 1 week; Jarmolowicz, Bickel, & Gatchalian, 2013; Jarmolowicz et al., 2014), or imperfect and immediate versus ideal and delayed sexual encounters (Holt, Newquist, Smits & Tiry, 2014) or partners (Jarmolowicz, Lemley, Asmussen, & Reed, 2015). Although results indicate that hypothetical sexual activity can be characterized using methods modeled on delay discounting of money, and that sexual activity is often systematically discounted due to delay, a limitation of these tasks for understanding sexual health is that they do not model risk of STI transmission.

Addressing this important limitation, the Sexual Delay Discounting task (SDDT) of Johnson and Bruner (2012) specifically examines the impact of delay on likelihood of waiting to engage in condom-protected sex. The SDDT has shown associations with self-reported risky sex behaviors and high test-retest reliability (Johnson & Bruner, 2012; 2013; Herrmann et al., 2015), and multiple studies have found that users of illicit substances discount condom-protected sex more steeply than healthy controls (Bruner & Johnson, 2012; Herrmann et al., 2014; Herrmann et al., 2015; Johnson, Johnson, Herrmann & Sweeney 2015). Recently, a SDDT study of youth (18–25 years old) recruited from an urban city and surrounding metro area characterized by high STI prevalence rates, crime, and drug use (Dariotis & Johnson, 2015) indicated greater sexual delay discounting for hypothetical partners that they judged as “most want to have sex with” (relative to “least”) and “least likely to have an STI” (relative to “most”), with males showing higher likelihood of engaging in unprotected sex than females when facing no delay but no sex differences in the rate of sexual delay discounting. Moreover, greater sexual discounting in some conditions was significantly associated with a greater number of risky sexual partners in the lifetime.

With this background, the present investigation of college students contributes to the literature on sexual delay discounting in important ways. First, the study’s focus was on the most common developmental transition after high school, i.e., college (National Center for Education Statistics, 2013). The peer-dominated, collegiate environment increases youth’s exposure to risk taking opportunities (Arria et al., 2009) such as having unprotected sex, sex with multiple partners, and sex under the influence of alcohol and other drugs (American College Health Association, 2014; Flannery, Ellingson, Votaw, & Schaefer, 2003; Gullette & Lyons, 2006; Pluhar, Fongillo, Stycos, & Dempster-McClain, 2003). Importantly, the high rates of casual, uncommitted sexual encounters or “hook-ups” in college (Garcia, Reiber, Massey & Merriwether, 2013; Paul, 2006) tend to be associated with low rates condom use (MacDonald & Hynie, 2008). The rapidly increasing college enrollment rates (National Center for Education Statistics, 2014), coupled with the high rates of STI diagnosed in college students each year (e.g., Rimsza, 2005), underscore the importance of understanding factors that place this population at elevated risk for STI. Second, the study evaluated gender differences in sexual delay discounting and likelihood of having unprotected sex. To our knowledge, only one previous study (Dariotis & Johnson, 2015) examined gender differences in an adequately powered sample of high-risk female and male participants, with no indication of gender differences in sexual delay discounting. The current study is the first to examine gender differences in sexual delay discounting in a normative, yet at-risk sample. Finally, as in Dariotis and Johnson (2015), we examined possible correlates of sexual delay discounting and self-reported risky sex behaviors, HIV knowledge, and risk perception.

Method

Participants

Two hundred sixty-two college students from a large Mid-Atlantic public university participated in the study. This investigation was part of a larger study examining sexual risk taking among college students. Participants were recruited through the university’s Department of Psychology online portal of research studies, and received course credit for completion. To participate in the study, individuals had to be at least 18 years old, be proficient in English reading and writing, and willing to answer questions about sexual behaviors. The university’s Institutional Review Board approved all study procedures.

Measures

Sexual Delay Discounting Task (SDDT; Johnson & Bruner, 2012)

The SDDT is a visual analog scale (VAS) task designed to assess the delay discounting of hypothetical condom-protected sex. Prior to completing the task, participants were asked to pretend that they are not in a committed sexual relationship and that they would not be cheating if they indicated that they would have sex with someone in the SDDT. At the beginning of the SDDT, participants viewed 60 photographs of diverse, clothed individuals (30 females, 30 males) and selected photographs of individuals they would consider engaging in sexual intercourse with under the right circumstances. From this subset of photographs, the participant selected: 1) the partner that they would most want to have sex with [MOST WANT SEX], 2) the partner that they would least want to have sex with [LEAST WANT SEX], 3) the partner that they perceived as being the most likely to have a STI [MOST LIKELY STI], and 4) the partner that they perceived as being the least likely have an STI [LEAST LIKELY STI]. Selection of the same photograph for more than one partner condition (e.g., MOST WANT SEX and LEAST LIKELY STI) was allowed.

For each of the four partner conditions, the task presented participants with the corresponding picture and the following directions:

This is the person you would be [(most/least) likely to have sex with OR believe is the (most/least) likely to have an STI]. Imagine that you have just met this person. You are getting along great and they are interested in having sex with you now. Imagine you are confident that there is no chance of pregnancy, for example you know that one of you is either on the pill, has had their “tubes tied” or had a vasectomy.

For the first SDDT trial, participants were asked to imagine that there was a condom readily and immediately available (referred to as the zero-delay trial). Using the VAS located below the condition-specific instructions, the participant was asked to provide a score between 0 and 100, where 0 indicated “I will definitely have sex with this person without a condom” and 100 indicated “I will definitely have sex with this person with a condom.” In subsequent SDDT trials, participants provided scores for the same situation and partner, with the exception that sex with a condom would occur after waiting a period of time (delay). Delays were presented in ascending order (i.e., 1 hour, 3 hours, 6 hours, 1 day, 1 week, 1 month, and 3 months). Participants rated their likelihood of waiting these delays on the VAS. The order of the partner conditions was counterbalanced.

CDC Sexual Behavior Questionnaire (CSBQ; CDC, 2011)

The CSBQ includes questions about the frequency with which individuals engaged in unprotected oral, vaginal, and anal sex in the past six months, as well as if this occurred with potentially high-risk partners (e.g., prostitute, individual with HIV or AIDS diagnosis, injection drug users) or those with unknown sexual history. For the purposes of the present study, we weighted the sexual risk behaviors according to the relative ordinal risk of contracting STI (e.g., Smith, Grohskopf, Black et al., 2005) by assigning a value of 1 to instances of unprotected oral sex and a value of 2 to instances of unprotected vaginal/anal sex (e.g., Collado, Loya & Yi, 2015).

Brief HIV Knowledge Questionnaire (Carey, 2002)

This questionnaire asks respondents to indicate whether a statement about HIV transmission (e.g., “A person can get HIV by sharing a glass of water with someone who has HIV”) is true, false, or unknown. The sum of correct responses ranges from 0 to 18, with higher scores reflecting higher HIV knowledge. The scale has strong reliability and validity, with high internal consistency across samples (α≥.75). In the present study, the scale achieved an internal consistency of 0.64.

STI Risk Perception

This scale was modeled from a risk perception scale for alcohol use (Hampson, Severson, Burns, Slovic & Fisher, 2001). Participants indicated the extent to which they perceived risk for contracting STI from engaging in 1) unprotected oral sex, 2) unprotected vaginal sex, and 3) unprotected anal sex on a scale from 1 (not risky at all) to 10 (very risky). Modeling other studies of risk perception (e.g., Collado, Loya & Yi, 2015), a self-rated risk perception composite score was computed by summing the three items. Scores ranged from 3 to 30. Cronbach’s alpha for our composite risk perception score was .74.

Procedure

Following informed consent, participants completed all measures using a computer in a single session. Questionnaires (e.g., CSBQ, Brief HIV Knowledge Questionnaire) were completed in a counterbalanced order prior to completing the SDDT.

Data Analytic Plan

Consistent with previous research using the SDDT, participants who selected fewer than 2 pictures were excluded from data analyses (Dariotis & Johnson, 2015). The scores obtained in the SDDT are equivalent to what are called indifference points in conventional delay discounting jargon, and we refer to them as such going forward. The orderliness of the indifference points was assessed according to a criterion proposed by Johnson and Bickel (2008), and the application of these guidelines was consistent with previous research using the SDDT (Dariotis & Johnson, 2015). That is, nonsystematic indifference points (a point that is 0.20 greater than the previous point) were flagged and substituted with the average of the neighboring points of the nonsystematic value.

Standardized indifference points were computed by dividing each indifference point from a delay condition by the indifference point from the zero-delay trial, resulting in a metric that isolates the impact of delay on likelihood of using a condom by controlling for individual differences in likelihood of using a condom at all. To determine an index of sexual delay discounting within each partner condition, area under the curve (AUC; Myerson, Green, & Warusawitharana, 2001) measures were calculated using these standardized indifference points, where smaller values indicate less likelihood of waiting to have sex with a condom (i.e., greater sexual delay discounting).

In order to evaluate overall likelihood of engaging in unprotected sex, two 2 × 2 mixed ANOVAs were conducted on the indifference point from the zero-delay condition. The first ANOVA examined the effect of participant gender (male/female), the MOST WANT SEX and LEAST WANT SEX conditions, and their interaction. The second ANOVA examined the effect of participant gender (male/female), the LEAST LIKELY STI and MOST LIKELY STI), and their interaction. Identical ANOVAs were conducted on AUC to evaluate delay discounting of condom-protected sex.

Correlations were conducted between SDDT measures and HIV knowledge scores, risk perception scores, self-reported composite risky sexual behavior, and self-reported high risk vaginal, oral, and anal sex. In the case that there were gender differences in any of the partner conditions, we controlled for gender in partial correlations.

Results

Table 1 shows the sample’s descriptive statistics. The mean age was 19.72 years (SD = 1.99), and mean number of lifetime sexual partners was 3.83 (SD = 2.77). Most participants were female (54.8%). The racial distribution was: White (43.2%), Black (19.3%), Asian (14.3%), Latino/a (8.5%) and “Other” (14.7%). Participants had a mean HIV knowledge score of 12.75 (SD = 2.77) and a mean risk perception score of 23.62 (SD = 1.99). In the CSBQ, participants did not report engaging in anal, oral, or vaginal sex with a prostitute; anal, oral, or vaginal sex with someone who had HIV or AIDS; or anal sex with someone who injected drugs. The mean CSBQ score was 3.03 (SD = 2.37). Participants’ romantic relationship status was not related to sexual delay discounting in any condition (p-values ≥ 0. 71).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics

| Variable | Total sample |

|---|---|

| Age (M(SD)) | 19.72(1.99) |

| Sex | |

| Females (n, %) | 143, 54.8 |

| Males (n, %) | 117, 44.8 |

| Class standing | |

| Freshmen (n, %) | 87, 33.3 |

| Sophomores (n, %) | 69, 26.4 |

| Juniors (n, %) | 63, 24.1 |

| Seniors (n, %) | 41, 15.7 |

| Oral sex (yes, n, %) | 221, 84.4 |

| Vaginal sex (yes, n, %) | 193, 73.7 |

| Anal sex (yes, n, %) | 57, 21.8 |

| Total number of sexual partners (M(SD)) | 3.83 (3.71) |

| HIV Knowledge score (M(SD)) | 13.75 (2.77) |

| Real-world risky sexual behavior score (M(SD)) | 3.03 (2.37) |

| Risk Perception score (M(SD)) | 23.62 (1.99) |

Photo Selection

Participants who did not select any photos (n = 10) or only one photo (n = 12) across all partner conditions were excluded from analyses. Characteristics associated with selecting an insufficient number of photos included being female (r = −0.20, p < 0.001), greater HIV knowledge (r = 0.17, p = 0.02), and greater risk perception (r = −0.12, p = 0.05). The remaining participants selected between 2 and 36 photos of individuals with whom they would consider having sex (M = 9.08; SD = 6.53): Males selected more photos (M = 10.92, SD = 6.13) than females (M = 7.40, SD = 9.08; F [1, 237] = 18.53, p < 0.001).

Orderliness

Across all participants, there were 1008 sets of indifference points and 100 (9.92%) were flagged as having one nonsystematic point. Twenty-nine (2.89%) sets of indifference points were flagged as having two or more nonsystematic points and were excluded from further analyses. A total of 979 data sets remained for analyses (240 for MOST WANT SEX, 246 for LEAST WANT SEX, 247 for MOST LIKELY STI, and 246 for LEAST LIKELY STI)1.

General Likelihood of Engaging in Unprotected Sex

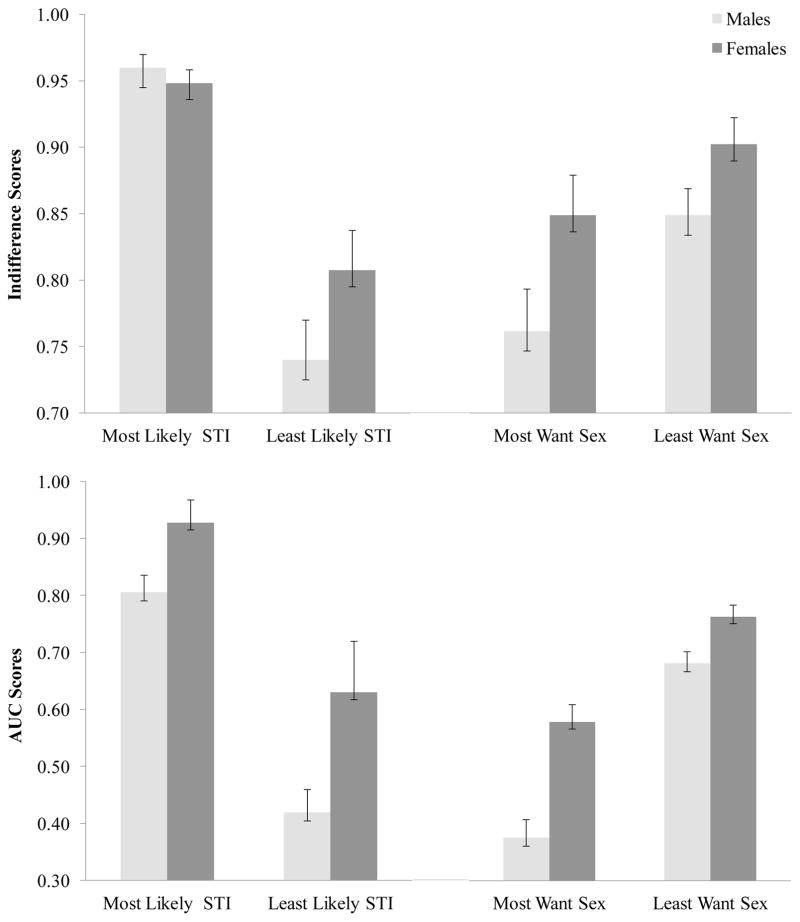

We examined college students’ general likelihood of engaging in unprotected sex despite having a condom immediately available, indexed by the indifference point from the zero-delay trial. The upper right graph of Figure 1 depicts ANOVA results of a significant main effect of gender [F (1, 458) = 7.56, p = 0.006; η2 = 0.02], a significant main effect of MOST/LEAST WANT SEX [F (1, 458) = 7.53, p < 0.001; η2 = 0.02], but no significant interaction (p = 0.51). Males exhibited a significantly greater likelihood of engaging in unprotected sex than females. Further, there was a significantly greater likelihood of engaging in unprotected sex with the MOST WANT SEX (M = 0.80, SD = 0.31) relative to the LEAST WANT SEX partner [M = 0.87, SD = 0.25].

Figure 1.

Bar graphs depicting means and standard errors of general likelihood of engaging in unprotected sex and sexual delay discounting scores across partner conditions for males and females.

Note. STI = Sexually Transmitted Infection; Lower AUC and indifference scores denote steeper sexual delay discounting and general likelihood of engaging in unprotected sex. AUC and indifferences scores range from 0–1.0.

The upper left graph of Figure 1 shows a significant main effect of MOST/LEAST LIKELY STI [F (1, 463) = 60.77, p < 0.001; η2 = 0.12], no significant main effect of gender (p = 0.23), and no significant interaction (p = 0.09). Participants indicated a significantly greater likelihood of engaging in unprotected sex in the LEAST LIKELY STI (M = 0.78, SD = 0.33) relative to the MOST LIKELY STI partner condition (M = 0.95, SD = 0.16).

Sexual Delay Discounting

The lower right graph of Figure 1 shows that the AUC revealed significant main effects of gender [F (1, 439) = 11.14, p = 0.001; η2 = 0.03] and MOST/LEAST WANT SEX [F (1, 439) = 33.82, p < 0.001; η2 = 0.07], but no interaction (p = 0.16). Males showed steeper sexual delay discounting relative to females. Generally, participants showed significantly greater sexual discounting in the MOST WANT SEX (M = 0.82, SD = 0.31) compared to LEAST WANT SEX (M = 0.87, SD = 0.25) partner conditions. See Figure 1, lower right graph.

The lower left graph of Figure 1 shows results from an ANOVA conducted using AUC scores and indicates significant main effects of gender [F (1, 445) = 8.51, p = 0.004; η2 = 0.02] and MOST/LEAST LIKELY STI [F (3, 451) = 36.07, p < 0.001; η2 = 0.08], but no interaction (p = 0.44). Males exhibited significantly steeper sexual delay discounting than females. Participants exhibited significantly steeper sexual discounting in the LEAST LIKELY STI (M = 0.78, SD = 0.33) compared to the MOST LIKELY STI (M = 0.95, SD = 0.16) partner conditions.

Correlates of SDDT Risky Sexual Behavior

Greater general likelihood of engaging in unprotected sex (i.e., likelihood of condom use in zero-delay trial) was significantly associated with greater HIV knowledge only in the MOST LIKELY STI condition (r = 0.26, p < 0.001; Table 2), indicating that individuals that are knowledgeable about HIV are more likely to use a condom with a partner that is perceived as being more likely to have an STI. Likelihood of engaging in unprotected sex was not significantly correlated with either self-reported risk perception or risky sexual behaviors.

Table 2.

Correlation Coefficients between Study Variables, Sexually Delay Discounting, and Likelihood of Engaging in Unprotected Sex

| Most Likely STI | Least Likely STI· | Most Want Sex· | Least Want Sex | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Construct | 0-delay | AUC | 0-delay | AUC | 0-delay | AUC | 0-delay | AUC |

| HIV Knowledge | 0.26** | −0.12 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.09 | 0.05 | −0.01 | −0.10 |

| Risk Perception | −0.01 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.15* | 0.03 | 0.12 | 0.09 | 0.07 |

| Self-reported composite risky sexual behaviors | 0.10 | −0.19** | 0.04 | −0.17* | −0.09 | −0.17* | −0.05 | −0.20** |

Note. STI = Sexually Transmitted Infection; 0-delay denotes general likelihood of engaging in unprotected sex; AUC denotes standardized scores of sexual delay discounting;

Analyses controlled for sex;

p < 0.05,

p < 0.01.

Greater sexual delay discounting was significantly associated with higher engagement in self-reported risky sexual behaviors across partner all conditions (see Table 2 for coefficients). A significant positive correlation was observed between sexual delay discounting in the LEAST LIKELY STI condition and self-reported risk perception (r = 0.15, p = 0.02), suggesting that college students were more likely to wait to use a condom with a partner perceived less risky for STI transmission at lower levels of self-reported risk perception. No significant relations were observed between sexual delay discounting and HIV knowledge.

Discussion

The current study extends earlier research examining delay discounting of condom-protected sex with samples at high-risk for STI contraction and transmission, including individuals with substance use disorders (e.g., Herrmann et al., 2014; Herrmann et al., 2015; Johnson & Bruner, 2012; Johnson et al., 2015) and youth from socioeconomically disadvantaged backgrounds (Dariotis & Johnson, 2015). The present study demonstrates that college students are less likely to use an immediately available condom and less likely to wait to engage in condom-protected sex when partners are viewed as more desirable (i.e., MOST WANT SEX) and less likely to have an STI (i.e., LEAST LIKELY STI). The findings also indicate that males are less likely to use an immediately available condom and less likely to wait to engage in condom-protected sex relative to females under these same circumstances. Broadly, an important implication of these findings is the critical role of perception of partners’ STI status. Additionally, risky sexual behavior is particularly likely when the partner is viewed as very sexually attractive. The findings suggest that educational programs for STI should include modules that target risk misperceptions and discuss how to make safer sex decisions when having strong feelings of attraction toward a sexual partner.

Given that males exhibited steeper sexual delay discounting compared to females when partner desirability was high and perceived risk of STI was low, males appear to be particularly at-risk for STI when a condom is not immediately available. A reasonable public health recommendation that follows is that males (and females who have sex with males) should carry a condom at all times (Dariotis & Johnson, 2015). However, based on the zero-delay trial findings, males’ general likelihood of having sex without a condom suggests that even when a condom is immediately available, males may not opt to use it, particularly in cases where the partner is perceived as being highly desirable. And despite the present results indicating that females are less prone to have unprotected sex relative to males, females remain at risk; notably, females’ general likelihood for unprotected sex did not differ from that of males when they perceived that a hypothetical sexual partner had a low risk of STI. By visually inspecting Figure 1, the pattern of results suggests that delays to sex also increase STI risk among females. Additionally, the entire sample exhibited a decreased likelihood of waiting for condom-protected sex with partners perceived as highly desirable or carrying low-risk of STI transmission. Altogether, delays to sex should be considered a critical STI risk factor for both male and female college students.

While no relations were generally observed between the delay discounting of condom-protected sex and HIV knowledge nor risk perception, sexual delay discounting was correlated with the assessment with the greatest conceptual overlap: self-reported risky sex behaviors. This is consistent with the findings reported in research with individuals who met criteria for cocaine dependence (Johnson & Bruner, 2012). The correlation between self-reported risky sexual behavior and sexual delay discounting but not with general likelihood of using a condom is noteworthy. These findings indicate that while there is no relation between whether a person uses an available condom and whether they engage in risky sex practices, willingness to wait for condom-protected sex (i.e., delay gratification) is associated with whether a person engages in self-reported risky sexual practices. This corroborates that delay to condom-protected sex is a potentially critical contributor to risky sex behaviors.

Interestingly, in a previous study of a sample of high-risk youth (Dariotis & Johnson, 2015), only sexual delay discounting in the MOST WANT SEX partner condition was significantly correlated with self-reported risky sex. Various possibilities could exist for the discrepancy between our results and the results reported in Dariotis and Johnson (2015). First, the current sample is larger which could have increased our power to detect significant associations. Second, the college sample may differ from the high-risk, urban sample that was recruited in Dariotis and Johnson’s study (2015). Finally, this discrepancy may be due to differences across studies in the index of risky sexual behavior (lifetime number of risky partners in Dariotis & Johnson, 2015); the composite measure of the present study can be considered a more comprehensive and perhaps accurate measure of sexual risk taking, particularly amongst college students. Altogether, these differences between our results and previous studies with high-risk youth confirm the importance and uniqueness of examining sexual delay discounting among college students. Few relations between sexual delay discounting and common correlates of self-reported risky sexual behavior were observed, consistent with previous literature indicating low predictive power of these putative risk factors and risky sexual behavior (e.g., Kirby & DiClemente, 1994; Scott-Sheldon, Carey & Carey, 2008). Also consistent with previous suggestions (e.g., Collado, Loya, & Yi, 2015), we believe that future adequately powered studies should examine the interaction of each these risk factors and in more nuanced models.

The current study should be interpreted in light of its limitations. First, the study effect sizes were relatively small and future studies are warranted to replicate these results. A second limitation is that the analyses excluded 22 participants who did not select a sufficient number of photographs; these participants were more likely to be female, had higher HIV knowledge, and reported greater perceived risk. The non-random exclusion of these participants may suggest limited internal validity. In their research, Johnson and Bruner (2012) suggested that the number of photographs selected may be considered a model of promiscuity within the SDDT. Nonetheless, it is important that future studies examine the extent to which these non-random exclusions generalize in different, larger, and STI at-risk samples. A third limitation is the hypothetical nature of the sexual delay discounting task. However, the significant relations between the task and self-reported risk discussed above, and previous finding suggesting that similar results are obtained with hypothetical and real money (e.g., Johnson and Bickel, 2002; Baker et al., 2003; Johnson et al., 2007) partially serve to mitigate this concern. Nonetheless, the hypothetical task, combined with retrospective and self-report assessment of risky sexual behavior, limits our ability to draw conclusions about the predictive validity of the SDDT. As an additional limitation, demand characteristics may have influenced participant responding on the SDDT because the task presents delays to sex in ascending order. To mitigate this potential bias, future investigations using the SDDT may choose to randomize the order in which the delays are presented. We also did not examine alcohol and drug use in the context of risky sex, which play a substantial role is risky sexual practices by college students (Scott-Sheldon, Carey, & Carey, 2010; Wechsler, Lee, Juo, & Lee, 2000).

Despite these limitations, the current study contributes to the growing literature on the partner and situational characteristics that impact college students’ likelihood of engaging in unprotected sex, with emphasis on important gender differences. The current study highlights an inability to wait for condom-protected sex as an important factor for risky sexual behavior among college students, and provides support for the use of the SDDT with a normative sample of college students. Future research should examine additional moderators and mediators of sexual delay discounting, as well as capitalize on the extensive literature on approaches to reduce delay discounting in order to minimize STI risk of college students.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Nicole Roper and the RSF team for collecting study data.

Funding: Anahi Collado was supported by NIMH grant 5F31MH098512-02. Patrick S. Johnson was supported by NIDA grant T32DA007209. Richard Yi was supported by NIDA grant R01 DA11682. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Data were also analyzed by 1) removing the problematic indifference points only, 2) removing participant cases in which problematic indifference points were observed, and 3) by leaving the data intact. The findings remained consistent with the results reported in this manuscript.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Ethical approval: This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- American College Health Association. American College Health Association-National College Health Assessment II: Reference Group Executive Summary. 2014 Retrieved on September 20, 2015 from http://www.acha-ncha.org/docs/ACHA-NCHA-II_ReferenceGroup_ExecutiveSummarySpring2014.pdf.

- Arria AM, Vincent KB, Caldeira KM. Measuring liability for substance use disorder among college students: Implications for screening and early intervention. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2009;35(4):233–241. doi: 10.1080/00952990903005957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford WD. The association between individual time preferences and health maintenance habits. Medical Decision Making. 2010;30(1):99–112. doi: 10.1177/0272989x09342276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey MP, Schroder KEE. Development and psychometric evaluation of the brief HIV Knowledge Questionnaire. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2002;14(2):172–182. doi: 10.1521/aeap.14.2.172.23902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Control HIV/STD Behavioral Surveillance Working Group. Sexual Behavior Questions. 2011 Retrieved from http://chipts.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/downloads/2012/01/CDC-Sexual-Behavior-Questions-CSBQ.pdf.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance 2013. 2014 Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/std/stats13/adol.htm.

- Collado A, Loya JM, Yi R. The interaction of HIV knowledge, perceived risk, and gender differences on risky sex. International Journal of Sexual Health. 2015;27(4):418–428. doi: 10.1080/19317611.2015.1031312. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dariotis JK, Johnson MW. Sexual discounting among high-risk youth ages 18–24: Implications for sexual and substance use risk behaviors. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2015;23(1):49–58. doi: 10.1037/a0038399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flannery D, Ellingson L, Votaw KS, Schaefer EA. Anal intercourse and sexual risk factors among college women, 1993–2000. American Journal of Health Behavior. 2003;27(3):228–234. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.27.3.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia JR, Reiber C, Massey SG, Merriwether AM. Sexual hook-up culture. American Psychological Association. 2013;44:60. doi: 10.1037/e505012013-009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gullette DL, Lyons MA. Sensation seeking, self-esteem, and unprotected sex in college students. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care. 2006;17(5):23–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hampson SE, Severson HH, Burns WJ, Slovic P, Fisher KJ. Risk perception, personality factors and alcohol use among adolescents. Personality and Individual Differences. 2001;30(1):167–181. doi: 10.1016/s0191-8869(00)00025-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrickson KL, Rasmussen EB. Effects of mindful eating training on delay and probability discounting for food and money in obese and healthy-weight individuals. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2013;51(7):399–409. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2013.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann ES, Hand DJ, Johnson MW, Badger GJ, Heil SH. Examining delay discounting of condom-protected sex among opioid-dependent women and non-drug-using control women. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2014;144:53–60. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.07.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann ES, Johnson PS, Johnson MW. Examining Delay Discounting of Condom-Protected Sex Among Men Who Have Sex with Men Using Crowdsourcing Technology. AIDS and Behavior. 2015;19:1655–65. doi: 10.1007/s10461-015-1107-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holliday SB, King C, Heilbrun K. Offenders’ perception of risk factors for self and others: Theoretical importance and some empirical data. Criminal Justice and Behavior. 2013;40(9):1044–1061. doi: 10.1177/0093854813482308. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Holt DD, Newquist MH, Smits RR, Tiry AM. Discounting of food, sex, and money. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. 2014;21(3):794–802. doi: 10.3758/s13423-013-0557-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarmolowicz DP, Bickel WK, Gatchalian KM. Alcohol-dependent individuals discount sex at higher rates than controls. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2013;131(3):320–323. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarmolowicz DP, Landes RD, Christensen DR, Jones BA, Jackson L, Yi R, Bickel WK. Discounting of money and sex: Effects of commodity and temporal position in stimulant-dependent men and women. Addictive Behaviors. 2014;39(11):1652–1657. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.04.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarmolowicz DP, Lemley SM, Asmussen L, Reed DD. Mr. right versus Mr. right now: A discounting-based approach to promiscuity. Behavioural Processes. 2015;115:117–122. doi: 10.1016/j.beproc.2015.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MW, Bickel WK. An algorithm for identifying nonsystematic delay-discounting data. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2008;16(3):264–274. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.16.3.264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MW, Bruner NR. The Sexual Discounting Task: HIV risk behavior and the discounting of delayed sexual rewards in cocaine dependence. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2012;123(1–3):15–21. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.09.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MW, Bruner NR. Test–retest reliability and gender differences in the sexual discounting task among cocaine-dependent individuals. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2013;21(4):277–286. doi: 10.1037/a0033071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MW, Johnson PS, Herrmann ES, Sweeney MM. Delay and probability discounting of sexual and monetary outcomes in individuals with cocaine use disorders and matched controls. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(5):e0128641. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0128641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby D, DiClemente RJ. School-based interventions to prevent unprotected sex and HIV among adolescents. AIDS Prevention and Mental Health. 1994:117–139. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4899-1193-3_7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lawyer SR, Schoepflin FJ. Predicting domain-specific outcomes using delay and probability discounting for sexual versus monetary outcomes. Behavioural Processes. 2013;96:71–78. doi: 10.1016/j.beproc.2013.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawyer SR, Williams SA, Prihodova T, Rollins JD, Lester AC. Probability and delay discounting of hypothetical sexual outcomes. Behavioural Processes. 2010;84(3):687–692. doi: 10.1016/j.beproc.2010.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald TK, Hynie M. Ambivalence and unprotected sex: failure to predict sexual activity and decreased condom use. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 2008;38(4):1092–1107. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.2008.00340.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- MacKillop J, Amlung MT, Few LR, Ray LA, Sweet LH, Munafò MR. Delayed reward discounting and addictive behavior: A meta-analysis. Psychopharmacology. 2011;216(3):305–321. doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2229-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myerson J, Green L, Warusawitharana M. Area under the curve as a measure of discounting. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 2001;76(2):235–243. doi: 10.1901/jeab.2001.76-235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Education Statistics. Immediate transition to college. 2014 Retrieved on November 5, 2015 from https://nces.ed.gov/fastfacts/display.asp?id=51.

- Paul E. Beer goggles, catching feelings, and the walk of shame: Myths and realities of the hook up experience. In: Kirkpatrick DC, Duck S, Foley MK, editors. Relating difficulty: The processes of constructing and managing difficult interaction. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2006. pp. 141–160. [Google Scholar]

- Pluhar EI, Frongillo EA, Stycos JM, Dempster-McClain D. Changes over time in college student’s family planning knowledge, preference, and behavior and implications for contraceptive education and prevention of sexually transmitted infections. College Student Journal. 2003;37(3):420–434. [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen EB, Lawyer SR, Reilly W. Percent body fat is related to delay and probability discounting for food in humans. Behavioural Processes. 2010;83(1):23–30. doi: 10.1016/j.beproc.2009.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reimers S, Maylor EA, Stewart N, Chater N. Associations between a one-shot delay discounting measure and age, income, education and real-world impulsive behavior. Personality and Individual Differences. 2009;47(8):973–978. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2009.07.026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rimsza ME. Sexually transmitted infections: New guidelines for an old problem on the college campus. Pediatric Clinics of North America. 2005;52(1):217–228. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2004.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satterwhite CL, Torrone E, Meites E, Dunne EF, Mahajan R, Ocfemia MCB, … Weinstock H. Sexually transmitted infections among US women and men. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2013;40(3):187–193. doi: 10.1097/olq.0b013e318286bb53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott-Sheldon LAJ, Carey KB, Carey MP. Health behavior and college students: Does Greek affiliation matter? Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2007;31(1):61–70. doi: 10.1007/s10865-007-9136-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott-Sheldon LA, Carey MP, Carey KB. Alcohol and risky sexual behavior among heavy drinking college students. AIDS and Behavior. 2010;14(4):845–853. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9426-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DK, Grohskopf LA, Black RJ, Auerbach JD, Veronese F, Struble KA, … Greenberg AE. Antiretroviral postexposure prophylaxis after sexual, injection-drug use, or other nonoccupational exposure to HIV in the United States: Recommendations from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. MMWR Recommendations and Reports. 2005;54(RR02):1–20. doi: 10.1037/e548812006-001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- So J, Nabi R. Reduction of perceived social distance as an explanation for media’s influence on personal risk perceptions: A test of the risk convergence model. Human Communication Research. 2013;39(3):317–338. doi: 10.1111/hcre.12005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler H, Lee JE, Juo M, Lee H. College binge drinking in the 1990’s: A continuing problem. Journal of American College Health. 2000;48(5):199–210. doi: 10.1080/07448480009599305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinstock H, Berman S, Cates W. Sexually transmitted diseases among American youth: Incidence and prevalence estimates, 2000. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2004;36(1):6–10. doi: 10.1363/3600604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi R, Mitchell SH, Bickel WK. Delay discounting and substance abuse-dependence. In: Madden GJ, Bickel WK, editors. Impulsivity: The behavioral and neurological science of discounting. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2010. pp. 191–211. [DOI] [Google Scholar]