Introduction

Stillbirth is a major concern, affecting 0.6 per 1000 pregnancies in the United States [1] Preeclampsia is a common obstetric disorder, occurring in 2% to 7% of pregnancies [2, 3] and is a major risk factor for stillbirth, increasing the odds by 1.2 to 4.0 fold [4, 5, 6, 7]. The rate of stillbirth in women with preeclampsia in high-income countries is estimated as 0.3–1.9%, although it was previously as high as 4.4–7% [8, 9, 10]. Hypertensive disorders contribute to 9.2% of stillbirths in a contemporary cohort [10]. Risk factors for the two overlap, including obesity, pre-gestational diabetes mellitus, lupus, renal disease, advanced maternal age, nulliparity, non-Hispanic black race, and multifetal gestation [2, 12, 13, 14].

Placental insufficiency is often implicated in stillbirth, particularly in the setting of preeclampsia. Placental insufficiency is when a maladaptive placenta fails to provide adequate oxygen and nutrients to the growing fetus, leading to both adverse obstetric sequelae and fetal programming [15]. The pathophysiology of placental insufficiency includes abnormal trophoblast invasion or placental damage, leading to decreased placental perfusion [16, 17, 18, 19, 20]. Placental lesions can be divided into “maternal malperfusion” or “fetal vascular abnormalities. Maternal malperfusion lesions involve the maternal circulation, such as abnormal maternal vasculature, parenchymal infarct or thrombus, and intervillous/perivillous lesions. Fetal vascular abnormalities reflect lesions on the fetal side of the placenta, including abnormal development or thrombus/infarct of the fetal vasculature within the placenta [21].

In case-control studies, lesions consistent with both maternal vascular malperfusion and fetal vascular abnormalities have been noted more frequently in placentas from women with early onset, severe preeclampsia. These include decidual vasculopathy, infarcts, distal villous hypoplasia, and excessive syncytial knots [19, 22, 23, 24]. Placentas in preeclamptic pregnancies are also typically smaller for gestational age than those from normal pregnancies (20). Early-onset preeclampsia appears to have a more severe placental phenotype than late-onset preeclampsia [25, 26].

Because of this, we believe placental pathology in stillbirths associated with preeclampsia will be different than stillbirths not associated with preeclampsia. We aim to compare placental pathology 1) in stillbirths with and without preeclampsia and 2) in stillbirths with preeclampsia and live births with preeclampsia (and we speculate that this latter comparison will be similar).

Methods

This is a subanalysis of a population-based case-control study of stillbirth conducted by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Stillbirth Collaborative Research Network [27]. Participants were enrolled at delivery between March 2006 and September 2008. There were five catchment areas defined by state and county boundaries, including Rhode Island and portions of Massachusetts, Georgia, Texas, and Utah. 59 hospitals participated, ensuring access to at least 90% of births in each catchment area.

Study methods, study design, and sample size considerations have been previously published [27]. We attempted to enroll all women with a stillbirth (cases) in the catchment areas and a representative sample of women with a live birth (controls). Women delivering live births before 32 weeks of gestation were oversampled to ensure adequate numbers for stratified analyses. The study was approved by the institutional review boards of each clinical site and the Data Coordinating and Analysis Center, and all mothers gave written informed consent.

Our primary comparison was stillbirths with PE/GH vs. stillbirths without PE/GH. This analysis was stratified by term or preterm delivery. Secondary comparison was stillbirths with PE/GH vs. live births with PE/GH. Given that preterm births secondary to preterm labor are associated with abnormal histopathology as well [29], we stratified analyses by term (delivery at or beyond 37 weeks of gestation) and preterm (delivery prior to 37 weeks of gestation).

Stillbirths were defined as births at or after 20 weeks’ gestation with Apgar scores of 0 at 1 and 5 minutes and no signs of life on direct observation. Fetal deaths at 18 or 19 weeks’ gestation without good dating criteria were also enrolled so as to include all potential cases at or after 20 weeks’ gestation. Gestational age was determined using data from assisted reproductive technology, first day of last menstrual period, and ultrasound [27]. Deliveries resulting from termination of a live fetus were excluded.

Maternal interviews and medical record abstractions were conducted for all participants, and a standardized detailed placental examination protocol was performed as previously described [28]. Prior to study initiation, workshops were held to standardize the pathology examination and reporting. No fewer than five full-thickness placental tissue samples were obtained, one at the umbilical cord insertion and four others randomly. The full placental examination protocol included digital imaging under specified lighting, macroscopic examination, collection of frozen and ambient temperature samples of the cord, membranes and the placental disc, and microscopic examination of sections collected per protocol. Pathologists were not blinded to stillbirth or live birth status, as these evaluations were included as part of the clinical evaluation of cause of death or other adverse pregnancy outcome.

Placental lesions were categorized by potential mechanisms including developmental, inflammatory, and circulatory mechanisms using standard definitions [29]. The extent of the lesion was defined as follows: focal, present in one area or on one slide; multifocal or patchy, present in more than one area or in multiple slides, or both; and diffuse, when the lesions involved the full thickness of the placental disk and involved all slides to a similar degree. Inflammatory lesions were defined as maternal (involving the free chorioamnion, decidua, and chorionic plate of the placental disc) or fetal (involving the umbilical cord or fetal vessels of the chorionic plate).

The analyses were weighted for oversampling and other aspects of the study design and for availability of the placental examination using SUDAAN 11.0.0 software [27]. Construction of the weights for the overall study [27] and for the placental examination [28], have been previously described. If fewer than 5 subjects were present in any given category, we did not calculate OR for that comparison. Analysis was restricted to placentas from singleton gestations.

Subjects were identified as having pre-eclampsia/gestational hypertension (PE/GH) if: PE/GH was specifically noted in the chart for any hospitalizations during pregnancy or for the delivery hospitalization; magnesium sulfate was administered during the delivery hospitalization for PE; antihypertensive medications were prescribed during the pregnancy and not prior to the pregnancy; or hypertension was noted during the pregnancy in combination with a 24 hour urine protein >300 mg, serum creatinine >0.8 mg/dl, or platelets <100,000/mm [27]. Hypertension was defined as a systolic blood pressure greater than or equal to 140 mmHg or a diastolic blood pressure greater than or equal to 90 mmHg. Subjects not meeting these criteria were coded as “no PE/GH.” Because data regarding proteinuria and maternal serum laboratory testing were not available on each participant, we combined the categories of pre-eclampsia and gestational hypertension.

Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals were calculated from univariable logistic regression models.

Results

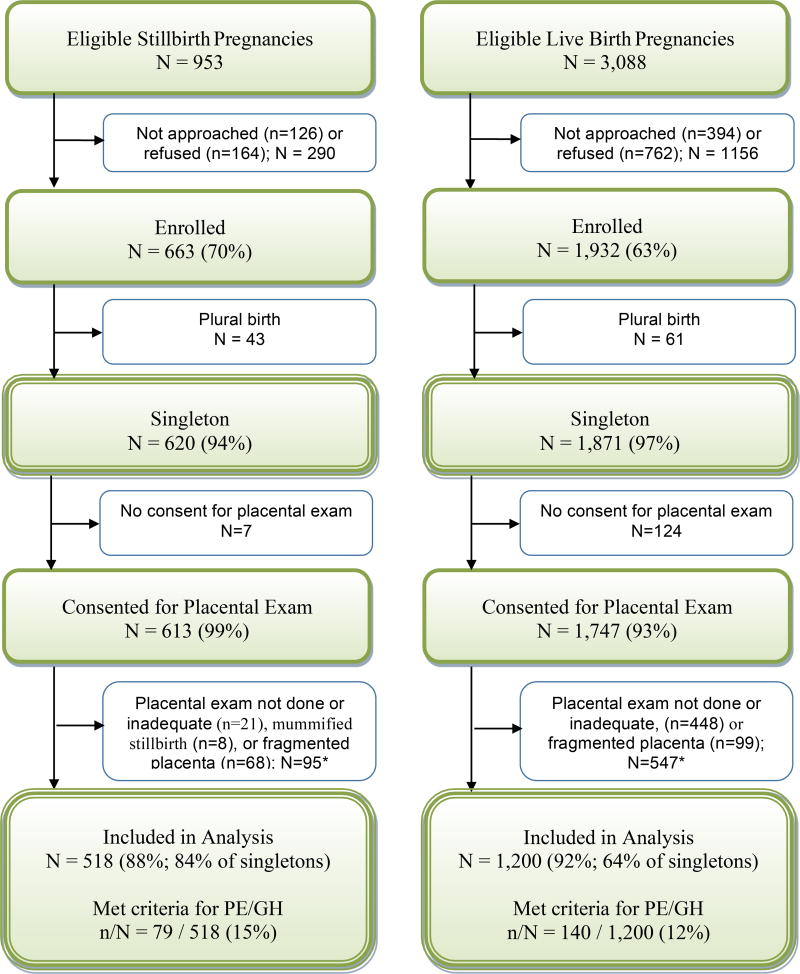

Figure 1 depicts study enrollment. 663/953 (70%) of eligible stillbirth pregnancies were enrolled. 620/663 (94%) were singleton gestations, and 518/620 (84%) had analyzable placentas for examination. Of those, 79/518 (15%) stillbirths met criteria for PE/GH. 1,932/3,088 (63%) eligible live births were enrolled, of which 1,871/1,932 (97%) were singleton gestations, and 1,200/1,871 (64%) had analyzable placental examinations. Of those, 140/1,200 (12%) live births met criteria for PE/GH. Table 1 shows demographics of deliveries analyzed.

Figure 1.

This analysis compares placental examination results for subgroups of singleton stillbirth and live birth pregnancies, with particular focus on PE/GH. A pregnancy was categorized as a stillbirth pregnancy if there were any stillbirths delivered and as a live birth pregnancy if all live births were delivered. A fetal death was defined by Apgar scores of 0 at 1 and 5 minutes and no signs of life by direct observation. Fetal deaths were classified as stillbirths if the best clinical estimate of gestational age at death was 20 or more weeks. Fetal deaths at 18 and 19 weeks without good dating were also included as stillbirths.

* A placenta examination was deemed inadequate for this analysis if conducted by a pathologist other than those trained to follow the Stillbirth Collaborative Research Network placental exam protocol or if only slides were available for review. Mummified stillborn fetuses were those with Grade IV-V maceration among fragmented fetuses and Grade V maceration among intact fetuses. Two stillborn fetuses were both fragmented and macerated.

Table 1.

Characteristics for Singleton Pregnancies for Stillbirths and Live Births by PE/GH Status – Placental Analysis Weights

| Characteristic - weighted %a | Stillbirths | Live Births | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||

| PE/GH | No PE/GH | P-value | PE/GH | No PE/GH |

P-value | |

|

|

|

|||||

| Unweighted sample size | N=79 | N=439 | N=140 | N=1060 | ||

| Weighted sample size | Nw=78 | Nw=440 | Nw=105 | Nw=862 | ||

|

| ||||||

| Maternal age at delivery, years | ||||||

| <20 | 7 (9.4) | 67 (15.2) | 0.0179 | 9 (8.9) | 90 (10.5) | 0.0780 |

| 20–34 | 50 (63.9) | 308 (70.1) | 72 (69.2) | 665 (77.2) | ||

| 35–39 | 18 (22.9) | 44 (10.0) | 19 (18.5) | 87 (10.1) | ||

| 40+ | 3 (3.8) | 21 (4.7) | 4 (3.5) | 19 (2.3) | ||

| Total | 78 | 440 | 105 | 862 | ||

| Maternal race/ethnicity | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 23 (29.8) | 154 (34.9) | 0.7103 | 48 (45.9) | 387 (44.9) | 0.2072 |

| Non-Hispanic black | 19 (25.2) | 95 (21.6) | 12 (11.5) | 100 (11.7) | ||

| Hispanic | 29 (37.4) | 167 (37.9) | 42 (39.8) | 310 (35.9) | ||

| Other | 6 (7.5) | 24 (5.5) | 3 (2.9) | 65 (7.5) | ||

| Total | 77 | 440 | 105 | 862 | ||

| Marital status | ||||||

| Not married or cohabitating | 21 (29.4) | 102 (25.0) | 0.6151 | 20 (20.2) | 124 (15.0) | 0.6151 |

| Cohabitating | 16 (21.5) | 108 (26.4) | 21 (21.7) | 190 (23.1) | ||

| Married | 36 (49.1) | 199 (48.6) | 56 (58.1) | 508 (61.9) | ||

| Total | 73 | 409 | 97 | 822 | ||

| Maternal education, grade | ||||||

| 0–11 (none/primary/some secondary) | 21 (29.6) | 94 (23.1) | 0.4619 | 16 (16.5) | 151 (18.5) | 0.8167 |

| 12 (completed secondary) | 21 (29.7) | 120 (29.4) | 28 (29.2) | 221 (26.9) | ||

| 13+ (college) | 29 (40.7) | 193 (47.4) | 52 (54.3) | 448 (54.6) | ||

| Total | 71 | 408 | 96 | 821 | ||

| Insurance/method of payment | ||||||

| No insurance | 3 (3.8) | 30 (6.8) | 0.5786 | 3 (3.3) | 39 (4.5) | 0.5984 |

| Any public/private assistance | 43 (56.6) | 231 (52.6) | 56 (53.8) | 419 (48.6) | ||

| VA/commercial health ins/HMO | 30 (39.5) | 178 (40.5) | 45 (42.9) | 404 (46.9) | ||

| Total | 76 | 438 | 105 | 861 | ||

| Household income | ||||||

| Public/private assistance only | 8 (11.4) | 33 (8.1) | 0.2887 | 16 (16.7) | 38 (4.7) | 0.2887 |

| Public/private assistance and personal income | 30 (42.5) | 145 (35.8) | 34 (35.2) | 314 (38.5) | ||

| Personal income only | 33 (46.1) | 227 (56.1) | 46 (48.0) | 464 (56.8) | ||

| Total | 71 | 405 | 96 | 816 | ||

| Gestational age | ||||||

| 18–19 | 1 (1.4) | 10 (2.2) | 0.0045 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | <.0001 |

| 20–23 | 8 (10.1) | 156 (35.6) | 0 (0.1) | 3 (0.3) | ||

| 24–27 | 16 (20.0) | 61 (13.8) | 1 (1.1) | 3 (0.4) | ||

| 28–31 | 15 (19.3) | 51 (11.5) | 4 (4.1) | 3 (0.3) | ||

| 32–36 | 19 (24.4) | 86 (19.5) | 13 (12.1) | 61 (7.1) | ||

| 37+ | 19 (24.9) | 77 (17.5) | 86 (82.6) | 791 (91.9) | ||

| Total | 78 | 440 | 105 | 862 | ||

|

| ||||||

| Parity | ||||||

| Nulliparous | 35 (44.3) | 200 (45.7) | 0.8253 | 51 (48.5) | 282 (33.0) | 0.0041 |

| Multiparous | 43 (55.7) | 237 (54.3) | 54 (51.5) | 572 (67.0) | ||

| Total | 78 | 437 | 105 | 855 | ||

Weighted percentages and p-values are shown. The weights take into account the study design, differential consent based on characteristics recorded on all eligible pregnancies that were screened for the study, and differential losses to placental examination. Unweighted and weighted samples sizes are also provided. Sample sizes vary slightly by characteristic included in the table.

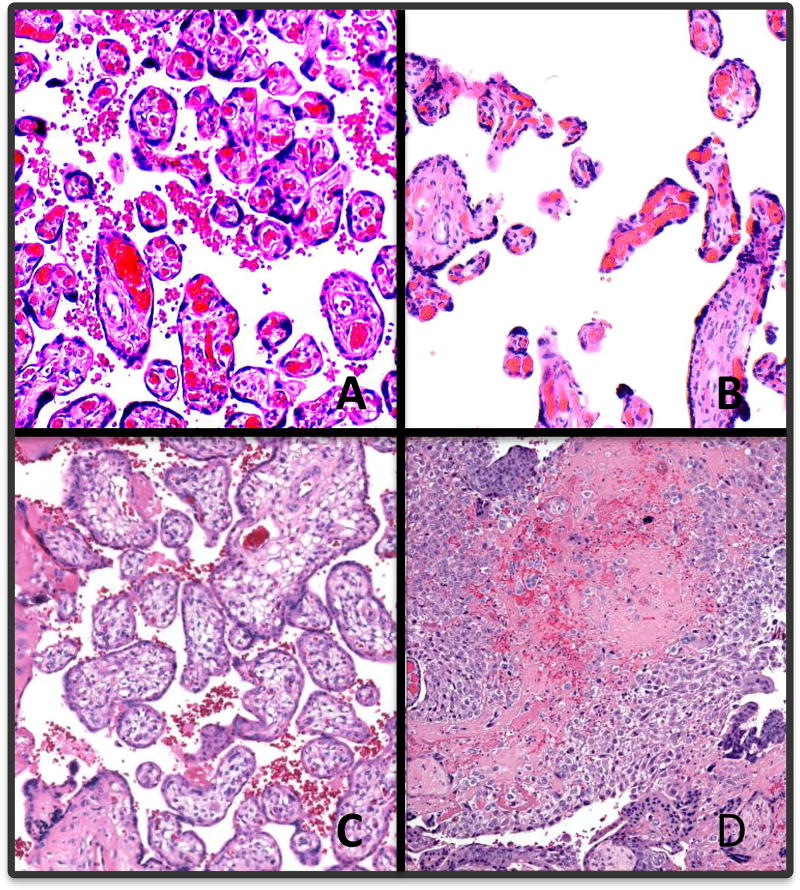

All stillbirths were analyzed after stratifying by term or preterm and comparing those with PE/GH to those without (Table 2). Figure 2 shows a representative sample of potential placental lesions, including distal villous hypoplasia, immature distal villi, and massive perivillous fibrin deposition. When considering all preterm stillbirths, there was a higher feto-placental ratio in PE/GH pregnancies (OR 1.24 [95% CI 1.11, 1.37) per unit increase). There were higher percentages of parenchymal infarction in preterm stillbirths with PE/GH than in preterm stillbirths without PE/GH: focal (OR 4.06 [95% CI 1.87, 8.83]), multifocal (OR 6.68 [95% CI 3.19, 13.98]), diffuse (OR 11.19 [3.49, 35.87]), and any (OR 5.77 [3.18, 10.47]). Inflammatory disorders were similar between PE/GH and no PE/GH preterm stillbirth deliveries. In term stillbirths, there were no differences in placental histology including infarction between pregnancies involving PE/GH and not involving PE/GH. Results were similar when limited to non-anomalous stillbirths, with the exception of a lower percentage of acute chorioamnionitis involving the chorionic plate in PE/GH affected preterm non-anomalous stillbirths compared to PE/GH unaffected preterm non-anomalous stillbirths (data not shown).

Table 2.

Selected Placental Findings for Stillbirth Pregnancies, PE\GH vs. No PE/GH Stratified by Prematurity

| Placental Characteristics | Preterm | Term | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||

| PE/GH N=60 |

No PE/GH N=359 |

OR | PE/GH N=19 |

No PE/GH N=80 |

OR | |

| Nw=59 | Nw=363 | Nw=19 | Nw=77 | |||

|

| ||||||

| PLACENTAL WEIGHT | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Placental weight | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Mean (SE) | 211.2 (19.4) | 203.6 (7.1) | 1.04 (0.84, 1.29) | 398.2 (33.7) | 425.2 (12.0) | 0.79 (0.40, 1.56) |

|

| ||||||

| Median (min-max) | 159.5 (59–764) | 161.9 (36–988) | OR per 100 g change | 353.7 (189–770) | 418.9 (152–713) | OR per 100 g change |

|

| ||||||

| Fetoplacental ratio | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Mean (SE) | 5.8 (0.4) | 4.5 (0.1) | 1.24 (1.11, 1.37) | 7.7 (0.5) | 8.0 (0.2) | 0.93 (0.71, 1.21) |

|

| ||||||

| Median (min-max) | 5.9 (2–15) | 3.8 (0–15) | OR per 1 unit change | 7.8 (2–11) | 7.7 (4–17) | OR per 1 unit change |

|

| ||||||

| Fetoplacental ratio categorized- % | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| <2.0 | 4.6 | 8.1 | 0.30 (0.08, 1.07) | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.00 (1.00, 1.00) |

|

| ||||||

| 2.0 – 2.9 | 8.7 | 21.9 | 0.21 (0.08, 0.58) | 6.9 | 0.0 | -- |

|

| ||||||

| 3.0 – 3.9 | 14.0 | 23.3 | 0.32 (0.14, 0.73) | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.00 (1.00, 1.00) |

|

| ||||||

| 4.0 – 4.9 | 10.8 | 14.0 | 0.41 (0.17, 1.00) | 0.0 | 1.7 | -- |

|

| ||||||

| 5.0+ | 61.9 | 32.7 | reference | 93.1 | 98.3 | reference |

|

| ||||||

| DEVELOPMENTAL DISORDERS | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Umbilical Cord- % | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Single umbilical artery | 6.6 | 8.7 | 0.75 (0.25, 2.23) | 5.3 | 4.8 | 1.10 (0.11, 10.61) |

|

| ||||||

| Velamentous insertiona | 1.7 | 6.3 | 0.26 (0.03, 1.99) | 10.3 | 0.0 | -- |

|

| ||||||

| Furcate insertiona | 0.0 | 1.9 | -- | 5.5 | 1.9 | 3.04 (0.18, 51.13) |

|

| ||||||

| Placental Membranes- % | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Circummarginateb | 11.7 | 12.3 | 0.94 (0.40, 2.25) | 11.2 | 12.1 | 0.92 (0.17, 4.89) |

|

| ||||||

| Circumvallateb | 2.9 | 2.5 | 1.15 (0.24, 5.58) | 4.8 | 0.9 | 5.46 (0.32, 92.44) |

|

| ||||||

| Fetal Villous Capillaries- % | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Delayed villous maturity (diffuse) | 5.1 | 10.5 | 0.46 (0.13, 1.57) | 15.1 | 11.6 | 1.35 (0.32, 5.75) |

|

| ||||||

| Terminal villous hypoplasia (diffuse) | 5.6 | 3.5 | 1.63 (0.42, 6.24) | 4.7 | 0.0 | -- |

|

| ||||||

| INFLAMMATORY DISORDERS | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Maternal Inflammatory Response- % | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Acute chorioamnionitis – placental membranes | 24.3 | 31.7 | 0.69 (0.36, 1.32) | 25.9 | 30.1 | 0.81 (0.26, 2.56) |

|

| ||||||

| Acute chorioamnionitis – chorionic plate | 14.9 | 23.9 | 0.56 (0.25, 1.25) | 29.9 | 24.6 | 1.30 (0.43, 3.96) |

|

| ||||||

| Fetal Inflammatory Response- % | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Acute funisitis | 4.0 | 11.8 | 0.31 (0.07, 1.39) | 5.7 | 3.6 | 1.61 (0.15, 16.66) |

|

| ||||||

| Acute umbilical cord arteritis (one or more arteries) | 2.6 | 4.1 | 0.61 (0.08, 4.81) | 0.0 | 1.0 | -- |

|

| ||||||

| Acute umbilical cord phlebitis | 2.5 | 5.3 | 0.47 (0.06, 3.58) | 10.6 | 3.7 | 3.12 (0.46, 20.96) |

|

| ||||||

| Chorionic plate acute vasculitis | 4.2 | 9.0 | 0.44 (0.10, 2.01) | 10.5 | 4.5 | 2.48 (0.41, 14.95) |

|

| ||||||

| Chorionic plate vascular degenerative changes | 1.6 | 6.7 | 0.23 (0.03, 1.72) | 6.5 | 3.6 | 1.83 (0.18, 18.76) |

|

| ||||||

| Villitis- % | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Acute diffuse villitis | 1.2 | 0.8 | 1.65 (0.17, 16.28) | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.00 (1.00, 1.00) |

|

| ||||||

| Chronic diffuse villitis | 0.0 | 1.6 | -- | 5.5 | 1.7 | 3.48 (0.21, 58.68) |

|

| ||||||

| CIRCULATORY DISORDERS | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Maternal Circulatory Disorders- % | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Retroplacental hematoma | 30.9 | 27.5 | 1.18 (0.63, 2.22) | 16.1 | 3.6 | 5.09 (0.91, 28.39) |

|

| ||||||

| Parenchymal Infarctionc | ||||||

| Focal | 22.6 | 11.6 | 4.06 (1.87, 8.83) | 24.7 | 15.7 | 1.92 (0.52, 7.01) |

| Multifocal | 29.0 | 9.0 | 6.68 (3.19, 13.98) | 11.2 | 6.2 | 2.19 (0.45, 10.66) |

| Diffuse | 11.4 | 2.1 | 11.19 (3.49, 35.87) | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.00 (1.00, 1.00) |

| Any Parenchymal Infarction | 63.0 | 22.8 | 5.77 (3.18, 10.47) | 35.9 | 21.9 | 1.99 (0.66, 5.99) |

|

| ||||||

| Intraparenchymal thrombus | 10.6 | 19.2 | 0.50 (0.20, 1.25) | 12.5 | 31.1 | 0.32 (0.07, 1.50) |

|

| ||||||

| Perivillous/intervillous fibrin/fibrinoid deposition (diffuse) | 9.6 | 10.6 | 0.89 (0.33, 2.45) | 5.1 | 3.5 | 1.50 (0.13, 17.85) |

|

| ||||||

| Fetal Circulatory Disorders- % | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Fetal vascular thrombi in the chorionic plate | 22.4 | 20.0 | 1.15 (0.57, 2.34) | 42.2 | 32.7 | 1.50 (0.52, 4.37) |

|

| ||||||

| Avascular villid | ||||||

| Focal | 3.4 | 6.7 | 0.49 (0.11, 2.14) | 9.5 | 14.5 | 0.71 (0.14, 3.52) |

| Multifocal | 11.9 | 7.6 | 1.50 (0.62, 3.67) | 13.5 | 2.6 | 5.62 (0.72, 43.62) |

| Diffuse | 1.4 | 5.4 | 0.26 (0.03, 1.97) | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.00 (1.00, 1.00) |

| Any Avascular Villi | 16.7 | 19.7 | 0.82 (0.39, 1.72) | 23.0 | 17.1 | 1.45 (0.41, 5.12) |

|

| ||||||

| Edema (Placental Hydrops) | 5.1 | 6.6 | 0.76 (0.22, 2.67) | 9.8 | 5.6 | 1.83 (0.30, 10.99) |

Nw is the weighted N

Includes umbilical cords with both velamentous and furcate insertion.

Includes membranes with both circummarginate and circumvallate insertion.

Reference group is no parenchymal infarction.

Reference group is no avascular villi.

Figure 2.

Hematoxylin and eosin micrographs of placental chorionic villi, 100× magnification. A) Normal term; B) distal villous hypoplasia; C) immature distal villi; D) massive perivillous fibrin deposition.

Table 3 shows all subjects with PE/GH and compares placental lesions found in stillbirths to those found in live births. Placentas from stillbirths were significantly smaller than those from live births (258.4 versus 435.4 grams), although this comparison is not adjusted for gestational age at delivery. In pregnancies affected by PE/GH, live births had higher feto-placental weight ratios than stillbirths overall (OR 0.8 [95% CI 0.65, 0.97] per 1 unit increase). There was a higher rate of velamentous cord insertion in the stillbirth group (3.9% versus 0%) but no significant difference in the odds associated with furcate insertion or single umbilical artery. There were higher percentages of maternal circulatory disorders in stillbirths compared to live births including retroplacental hematoma (OR 4.39 [95% CI 1.69, 11.37]), multifocal parenchymal infarction (OR 5.74 [2.46, 13.35]), and perivillous /intervillous fibrin/fibrinoid deposition (diffuse) (OR 6.67 [95% CI 1.17, 37.88]). Additionally, there were higher percentages of fetal circulatory disorders in stillbirth placentas including fetal vascular thrombi in the chorionic plate (OR 2.85 [95% CI 1.24, 6.51]), any avascular villi (OR 4.62 [95% CI 1.63, 13.07]), and multifocal avascular villi (OR 13.25 [95% CI 3, 58.60]).

Table 3.

Selected Placental Findings for Singleton Pregnancies, PE\GH Affected Stillbirths vs. PE\GH Affected Live Births Stratified by Prematurity

| CHARACTERISTICS | PE/GH | OR for PE/GH Affected Stillbirths vs. PE\GH Affected Live Births |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||||

| Stillbirths | Livebirths | ||||||

|

|

|

||||||

| PTB N=60 |

Term N=19 |

Overall N=79 |

PTB N=49 |

Term N=91 |

Overall N=140 |

||

| Nw=59 | Nw=19 | Nw=78 | Nw=18 | Nw=86 | Nw=105 | ||

|

| |||||||

| PLACENTAL WEIGHT | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Placental weight | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Mean (SE) | 211.2 (19.4) | 398.2 (33.7) | 258.4 (19.6) | 322.8 (26.9) | 459.1 (12.0) | 435.4 (11.9) | 0.42 (0.30, 0.60) |

|

| |||||||

| Median (min-max) | 159.5 (59–764) | 353.7 (189–770) | 232.1 (59–770) | 303.4 (76–568) | 445.5 (207–700) | 435.8 (76–700) | OR per 100 g change |

|

| |||||||

| Fetoplacental ratio | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Mean (SE) | 5.8 (0.4) | 7.7 (0.5) | 6.3 (0.3) | 6.2 (0.2) | 7.4 (0.2) | 7.2 (0.1) | 0.80 (0.65, 0.97) |

|

| |||||||

| Median (min-max) | 5.9 (2–15) | 7.8 (2–11) | 6.3 (2–15) | 6.1 (2–9) | 7.3 (5–14) | 7.0 (2–14) | OR per 1 unit change |

|

| |||||||

| Fetoplacental ratio categorized- % | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| <2.0 | 4.6 | 0.0 | 3.4 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 143.85 (14.39, 1437.72) |

|

| |||||||

| 2.0 – 2.9 | 8.7 | 6.9 | 8.2 | 1.9 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 34.78 (4.79, 252.74) |

|

| |||||||

| 3.0 – 3.9 | 14.0 | 0.0 | 10.4 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 299.46 (36.24, 2474.43) |

|

| |||||||

| 4.0 – 4.9 | 10.8 | 0.0 | 8.0 | 8.1 | 1.5 | 2.6 | 4.20 (1.16, 15.28) |

|

| |||||||

| 5.0+ | 61.9 | 93.1 | 70.0 | 89.6 | 98.5 | 96.9 | reference |

|

| |||||||

| DEVELOPMENTAL DISORDERS | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Umbilical Cord- % | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Single umbilical artery | 6.6 | 5.3 | 6.3 | 3.9 | 0.7 | 1.3 | 5.15 (0.99, 26.83) |

|

| |||||||

| Velamentous insertiona | 1.7 | 10.3 | 3.9 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 81.99 (8.32, 807.97) |

|

| |||||||

| Furcate insertiona | 0.0 | 5.5 | 1.4 | 6.0 | 0.9 | 1.8 | 0.77 (0.07, 8.84) |

|

| |||||||

| Placental Membranes- % | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Circummarginateb | 11.7 | 11.2 | 11.6 | 3.8 | 5.6 | 5.3 | 2.35 (0.84, 6.59) |

|

| |||||||

| Circumvallateb | 2.9 | 4.8 | 3.3 | 0.0 | 1.7 | 1.4 | 2.38 (0.24, 23.63) |

|

| |||||||

| Fetal Villous Capillaries- % | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Delayed villous immaturity (diffuse) | 5.1 | 15.1 | 7.7 | 10.0 | 1.7 | 3.2 | 2.52 (0.69, 9.17) |

|

| |||||||

| Terminal villous hypoplasia (diffuse) | 5.6 | 4.7 | 5.4 | 12.0 | 2.0 | 3.8 | 1.45 (0.33, 6.31) |

|

| |||||||

| INFLAMMATORY DISORDERS | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Maternal Inflammatory Response- % | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Acute chorioamnionitis – placental membranes | 24.3 | 25.9 | 24.7 | 5.2 | 10.1 | 9.2 | 3.22 (0.97, 10.73) |

|

| |||||||

| Acute chorioamnionitis – chorionic plate | 14.9 | 29.9 | 18.6 | 1.7 | 13.0 | 11.0 | 1.85 (0.60, 5.73) |

|

| |||||||

| Fetal Inflammatory Response- % | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Acute funisitis | 4.0 | 5.7 | 4.4 | 1.3 | 1.7 | 1.7 | 2.71 (0.49, 14.95) |

|

| |||||||

| Acute umbilical cord arteritis (one or more arteries) | 2.6 | 0.0 | 2.0 | 0.6 | 2.9 | 2.5 | 0.78 (0.08, 7.68) |

|

| |||||||

| Acute umbilical cord phlebitis | 2.5 | 10.6 | 4.4 | 0.0 | 2.3 | 1.9 | 2.40 (0.45, 12.63) |

|

| |||||||

| Chorionic plate acute vasculitis | 4.2 | 10.5 | 5.8 | 9.6 | 3.2 | 4.4 | 1.36 (0.33, 5.66) |

|

| |||||||

| Chorionic plate vascular degenerative changes | 1.6 | 6.5 | 2.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | -- |

|

| |||||||

| Villitis- % | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Acute diffuse villitis | 1.2 | 0.0 | 0.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | -- |

|

| |||||||

| Chronic diffuse villitis | 0.0 | 5.5 | 1.4 | 2.3 | 0.0 | 0.4 | 3.41 (0.29, 40.09) |

|

| |||||||

| CIRCULATORY DISORDERS | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Maternal Circulatory Disorders- % | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Retroplacental hematoma | 30.9 | 16.1 | 27.1 | 4.8 | 8.5 | 7.8 | 4.39 (1.69, 11.37) |

|

| |||||||

| Parenchymal Infarctionc | |||||||

| Focal | 22.6 | 24.7 | 23.1 | 15.6 | 20.6 | 19.7 | 1.96 (0.89, 4.29) |

| Multifocal | 29.0 | 11.2 | 24.5 | 17.6 | 4.9 | 7.1 | 5.74 (2.46, 13.35) |

| Diffuse | 11.4 | 0.0 | 8.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | *not defined* |

| Any Parenchymal Infarction | 63.0 | 35.9 | 56.2 | 33.3 | 25.4 | 26.8 | 3.49 (1.85, 6.60) |

|

| |||||||

| Intraparenchymal thrombus | 10.6 | 12.5 | 11.1 | 10.1 | 11.2 | 11.0 | 1.00 (0.39, 2.60) |

|

| |||||||

| Perivillous/intervillous fibrin/fibrinoid deposition (diffuse) | 9.6 | 5.1 | 8.5 | 8.3 | 0.0 | 1.4 | 6.67 (1.17, 37.88) |

|

| |||||||

| Fetal Circulatory Disorders- % | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Fetal vascular thrombi in the chorionic plate | 22.4 | 42.2 | 27.4 | 19.0 | 10.2 | 11.7 | 2.85 (1.24, 6.51) |

|

| |||||||

| Avascular villid | |||||||

| Focal | 3.4 | 9.5 | 4.9 | 0.0 | 4.3 | 3.5 | 1.62 (0.38, 6.89) |

| Multifocal | 11.9 | 13.5 | 12.3 | 2.5 | 0.8 | 1.1 | 13.25 (3.00, 58.60) |

| Diffuse | 1.4 | 0.0 | 1.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | -- |

| Any Avascular Villi | 16.7 | 23.0 | 18.3 | 2.5 | 5.1 | 4.6 | 4.62 (1.63, 13.07) |

|

| |||||||

| Edema (Placental Hydrops) | 5.1 | 9.8 | 6.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | -- |

Nw is the weighted N

Includes umbilical cords with both velamentous and furcate insertion.

Includes membranes with both circummarginate and circumvallate insertion.

Reference group is no parenchymal infarction.

Reference group is no avascular villi.

Discussion

Both stillbirth and PE/GH were associated with several placental abnormalities. Stillbirths had more maternal and fetal placental lesions then live births, consistent with previous studies suggesting abnormal placental development as a cause of some stillbirths [31]. In this cohort, it has previously been reported that placental abnormalities were responsible for 23.6% of stillbirths [11]. Other causes included obstetric conditions (29.3%), fetal genetic/structural abnormalities (13.7%), infection (12.9%), umbilical cord abnormalities (10.4%), hypertensive disorders (9.2%), and other maternal medical conditions (7.8%) [11]. Parenchymal infarction was the one lesion associated with stillbirths in women with PE/GH, but only in the preterm stratum. Overall, PE/GH pregnancies that were delivered preterm had more histologic abnormalities and more severe abnormalities than those delivered at term. Notably, amongst term stillbirths, there was no difference in parenchymal infarctions between PE/GH affected and unaffected pregnancies. This may reflect a milder phenotype of PE/GH at term in this sample.

Placental lesions of note in our study are overwhelmingly lesions of maternal malperfusion. Others have reported that placental lesions of the fetal vasculature may be more predominant in pregnancies affected by both fetal growth restriction (FGR) and pre-eclampsia [23, 32]. We demonstrate chorionic villi with distal villous hypoplasia, immature distal villi, and massive fibrin deposition in Figure 2. The degree of maternal malperfusion on histopathology has been shown to correlate with clinical severity and preterm gestational age [25, 26, 33, 34], which is consistent with our findings. An investigation of 1,210 placental examinations from pregnancies complicated by pre-eclampsia found more placental hypoplasia (39% vs 18%, p<0.001) and more placental vascular lesions (53% vs 26%, p<0.001) in deliveries prior to 34 weeks compared to deliveries at or beyond 37 weeks gestation [26].

Lower feto-placental weight ratio was associated with stillbirth but not specifically with PE/GH in our analysis. In fact, PE/GH associated preterm stillbirths actually had higher feto-placental weight ratios than non-PE/GH associated stillbirths. Fetal growth restriction has previously been associated with diminished feto-placental ratio [32], suggesting that a less effective placenta producing fewer grams of fetus per gram of placenta causes fetal morbidity and mortality, although this is an imperfect marker. Feto-placental weight ratio is more clinically relevant than simple placental weight, as unadjusted weight is biased by gestational age at delivery. Perhaps stillbirth is more common when the placenta is less efficient, suggesting a failure at a functional level.

It is important to note that placental changes in the setting of stillbirth may not be causal. Rather, they may be sequelae of the intrauterine demise. The feto-placental ratio may be decreased in stillbirth due to decreased fetal perfusion. However, since lesions of the fetal vasculature are also noted in fetal growth restriction, these lesions may indeed be causal [23, 32].

A distinct strength of this study is that all placentas were examined and reported in a thorough, standardized protocol, with extensive sampling. Many previous studies evaluating placental lesions associated with pre-eclampsia were hampered by pathologists’ prior knowledge of PE/GH diagnosis and lack of consistency in pathologic reporting. The rigorous reporting protocol makes our findings less biased than many previous.

One limitation is that pathologists were not blinded to stillbirth or live birth status as they were also performing fetal autopsies and the placental examination was clinically reported. We are also limited by our sample size, which precludes extensive sub-analysis into various phenotypes of preeclampsia.

Placental pathology represents an endpoint view of abnormal development that ultimately led to the adverse outcomes of preeclampsia and/or stillbirth. Although parenchymal infarctions are more common in PE/GH affected preterm stillbirths, placental lesions found in placentas from both stillbirths and pregnancies affected by preeclampsia have significant overlap.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.MacDorman MF, Reddy UM, Silver RM. Trends in stillbirth by gestational age in the United States, 2006–2012. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126:1146–1150. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sibai B, Dekker G, Kupferminc M. Pre-eclampsia. Lancet. 2005;365:785–799. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17987-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abalos E, Cuesta C, Carroli G, Qureshi Z, Widmer M, Vogel JP, et al. WHO Multicountry Survey on Maternal and Newborn Health Research Network. Pre-eclampsia, eclampsia and adverse maternal and perinatal outcomes: a secondary analysis of the World Health Organization Multicountry Survey on Maternal and Newborn Health. BJOG. 2014;121:14–24. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.12629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haddad B, Mercer BM, Livingston JC, Sibai BM. Obstetric antecedents to apparent stillbirth (Apgar score zero at 1 minute only) Obstet Gynecol. 2001;97:961–964. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(01)01352-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fretts RC. Etiology and prevention of stillbirth. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193:1923–1935. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.03.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reddy UM, Laughon SK, Sun L, Troendle J, Willinger M, Zhang J. Prepregnancy risk factors for antepartum stillbirth in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116:1119–1126. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181f903f8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harmon QE, Huang L, Umbach DM, Klungsoyr K, Engel SM, Magnus P, et al. Risk of fetal death with preeclampsia. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:628–635. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cruz MO, Gao W, Hibbard JU. Obstetrical and perinatal outcomes among women with gestational hypertension, mild preeclampsia and mild chronic hypertension. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;205:e1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ahmad AS, Samuelse SO. Hypertensive disorders in pregnancy and fetal death at different gestational lengths: a population study of 2 121 371 pregnancies. BJOG. 2012;119:1521–1528. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2012.03460.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Basso O, Rasmussen S, Weinberg CR, Wilcox AJ, Irgens LM, Skjaerven R. Trends in fetal and infant survival following preeclampsia. JAMA. 2006;296:1357–1362. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.11.1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stillbirth Collaborative Research Network Writing Group. Causes of death among stillbirths. JAMA. 2011;306:2459–2468. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Steegers EAP, von Dadelszen P, Duvekot JJ, Pijnenborg R. Pre-eclampsia. Lancet. 2010;376:631–644. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60279-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pare E, Parry S, McElrath TF, Pucci D, Newton A, Lim KH. Clinical risk factors for preeclampsia in the 21st century. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124:763–770. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stillbirth Collaborative Research Network Writing Group. Association between stillbirth and risk factors known at pregnancy confirmation. JAMA. 2011;306:2469–2479. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Longtine MS, Nelson DN. Placental dysfunction and fetal programming: The importance of placental size, shape, histopathology, and molecular composition. Semin Reprod Med. 2011;29:187–196. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1275515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lockwood CJ, Huang SJ, Krikun G, Caze R, Rahman M, Buchwalder LF, et al. Decidual hemostasis, inflammation, and angiogenesis in pre-eclampsia. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2011;37:1–12. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1270344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lyall F, Robson SC, Bulmer JN. Spiral artery remodeling and trophoblast invasion in preeclampsia and fetal growth restriction: relationship to clinical outcome. Hypertension. 2013;62:1046–1054. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.113.01892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Osol G, Moore LG. Maternal uterine vascular remodeling during pregnancy. Microcirculation. 2014;21:38–47. doi: 10.1111/micc.12080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roberts DJ, Post MD. The placenta in pre-eclampsia and intrauterine growth restriction. J Clin Pathol. 2008;61:1254–1260. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2008.055236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Soto E, Romero R, Kusanovic JP, Ogge G, Hussein Y, Yeo L, et al. Late-onset preeclampsia is associated with an imbalance of angiogenic and anti-angiogenic factors in patients with and without placental lesions consistent with maternal underperfusion. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2012;25:498–507. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2011.591461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Redline RW. Classification of placental lesions. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;213:S21–S28. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2015.05.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Devisme L, Merlot B, Ego A, Houfflin-Debarge V, Deruelle P, Subtil D. A case-control study of placental lesions associated with pre-eclampsia. Int J Gyn Obstet. 2013;120:165–168. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2012.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kovo M, Schreiber L, Ben-Haroush A, Wand S, Golan A, Bar J. Placental vascular lesion differences in pregnancy-induced hypertension and normotensive fetal growth restriction. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202:e1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moldenauer JS, Stanek J, Warshak C, Khoury J, Sibai B. The frequency and severity of placental findings in women with preeclampsia are gestational age dependent. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189:1173–1177. doi: 10.1067/s0002-9378(03)00576-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ogge G, Chaiworapongsa T, Romero R, Hussein Y, Kusanovic JP, Yeo L, et al. Placental lesions associated with maternal underperfusion are more frequent in early-onset than in late-onset preeclampsia. J Perinat Med. 2011;39:641–652. doi: 10.1515/JPM.2011.098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nelson DB, Ziadie MS, McIntire DD, Rogers BB, Leveno KJ. Placental pathology suggesting that preeclampsia is more than one disease. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;210:e1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2013.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Parker CB, Hogue CJR, Koch MA, Willinger M, Reddy UM, Thorsten VR, et al. for the Stillbirth Collaborative Research Network. Stillbirth Collaborative Research Network: design, methods and recruitment experience. Paediatr and Perinatal Epidemiol. 2011;25:425–435. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2011.01218.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pinar H, Koch M, Hawkins H, Heim-Hall J, Shehata B, Thorsten VR, et al. The Stillbirth Collaborative Research Network (SCRN) placental and umbilical cord examination protocol. Am J Perinatol. 2011;28:781–792. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1281509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baergen R. Manual of Benirschke and Kaufmann’s pathology of the human placenta. Springer; New York: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stanek J. Comparison of placental pathology in preterm, late-preterm, near-term, and term births. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;210:e1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2013.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pinar H, Goldenberg RL, Koch M, Heim-Hall J, Hawkins HK, Shehata B, et al. Placental findings in singleton stillbirths. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123:325–336. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kovo M, Schreiber L, Ben-Haroush A, Gold E, Golan A, Bar J. The placental component in early-onset and late-onset preeclampsia in relation to fetal growth restriction. Prenatal Diagnosis. 2012;32:632–637. doi: 10.1002/pd.3872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stevens DU, Al-Nasiry S, Bulten J, Spaanderman MEA. Decidual vasculopathy in preeclampsia: Lesion characteristics relate to disease severity and perinatal outcome. Placenta. 2013;34:805–809. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2013.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Redman CW, Sargent IL, Staff AC. IFPA Senior Award Lecture: Making sense of pre-eclampsia – two placental causes of preeclampsia? Placenta. 2014;28:S20–S25. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2013.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.