Abstract

The nature and extent to which hydrological changes induced by the Asian summer monsoon affected key biogeochemical processes remain poorly defined. This study explores the relationship between peatland drying and carbon cycling on centennial timescales in central China using lipid biomarkers. The difference between peat n-alkane δ2H and a nearby stalagmite δ18O record reveals that intervals of prominent peatland drying occurred during the mid-Holocene. Synchronous with these drier conditions, leaf wax δ13C values show large negative excursions, with the utilization of CO2 respired from the peatland subsurface for plant photosynthesis being a possible mechanism. Crucially, successive drying events appear to have had a cumulative impact on the susceptibility of peat carbon stores to climate change. Concurrently, bacterially derived hopane δ13C values suggest the occurrence of enhanced methane oxidation during the drier periods. Collectively, these observations expand our understanding of how respiration and degradation of peat are enhanced during drying events.

The effect of Asian summer monsoon hydrological changes on key biogeochemical processes remains poorly understood. Here, using a suite of biomarkers, the authors reconstruct palaeohydrological conditions during the Holocene and show that the peatland carbon cycle is strongly sensitive to paleohydrological changes.

Introduction

Peatlands are a vast store of organic carbon and play a significant role in the global carbon cycle1, 2. The height of the water table in such environments is the primary influence on carbon degradation pathways and peatland carbon storage, exerting local control on redox conditions in the shallow subsurface3. Hence, changes in peatland hydrology will impact carbon storage; for example, dry conditions associated with drought bring about depression of the water table, enhancing degradation of organic matter and release of CO2 to the atmosphere3. Because global warming is likely to produce more frequent and/or severe droughts in many regions4, including in the monsoon region of China, it is crucial to better understand the relationship between hydrological change and the peatland carbon cycle across multiple timescales and particularly in regions expected to experience changing rainfall under future warming scenarios.

The hydrological impact on peatland carbon cycles, especially on varying timescales, continues to be debated. Even on annual timescales, the relationship between water-table lowering and soil organic carbon (SOC) dynamics in peatlands remains unclear; the conventional viewpoint is that drier conditions enhance SOC decomposition through the “enzyme latch” mechanism5. In contrast, recent work proposed a new “iron gate” mechanism to interpret the negative relationship between water-table decline and SOC decomposition in settings with abundant iron6. On longer timescales, our knowledge of how the peatland carbon cycle responds to drier conditions is even poorer, particularly in monsoon dominated regions7, 8. In East Asia, monsoon-mediated rainfall has varied both spatially and temporally since the late deglaciation9, 10, likely impacting the carbon cycle8.

In this study, we examine the response of the carbon cycle in a central China peatland to hydrological change over the past 18 ky, but especially to dry intervals during the middle Holocene. During the mid-Holocene, pronounced drier conditions occurred commonly in Indian monsoon dominated regions11. In eastern China, however, evidence for drier conditions during the mid-Holocene is limited, with most evidence coming from central China10, 12. The occurrence of such conditions in the middle Holocene in central China provides an opportunity to explore the relationship between paleohydrological conditions and the peatland carbon cycle.

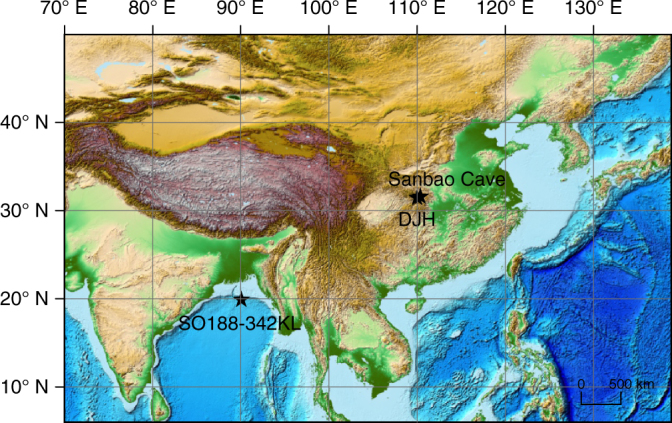

The Dajiuhu peatland is a typical subtropical subalpine peatland in central China (Fig. 1)13, and due to the monsoon-influenced climate, it was exposed to severe drying and flooding events12. To reconstruct paleohydrological conditions, we determined the controls on hydrogen isotope compositions in modern pore water, plants, and peats; based on those constraints and radiocarbon chronology, we use the difference between Dajiuhu leaf wax hydrogen isotope compositions (δ2Hwax) and the nearby Sanbao stalagmite δ18O sequence14, complemented by other biomarker indicators of vegetation and bacterial changes, to identify potential dry intervals in the Dajiuhu sequence over the past 18 ky. These records are then integrated with δ13C values for the same leaf waxes, as well as those of bacterially derived hopanes and carbon accumulation rates, to explore the response of peatland carbon cycle to drier conditions in the middle Holocene. Collectively, this study shows that the peatland carbon cycle is strongly sensitive to paleohydrological changes, expanding our understanding of how respiration and degradation of peat are enhanced during dry intervals.

Fig. 1.

Map of the sampling site. The Sanbao Cave and SO188-342KL site are also labeled. The public ETOPO1 data downloaded from https://ngdc.noaa.gov/mgg/global/relief/ETOPO1/image/ were used to plot the topographic map with the software of ArcGIS 9

Results

δ2H values of pore water and surface peat and modern plant lipids

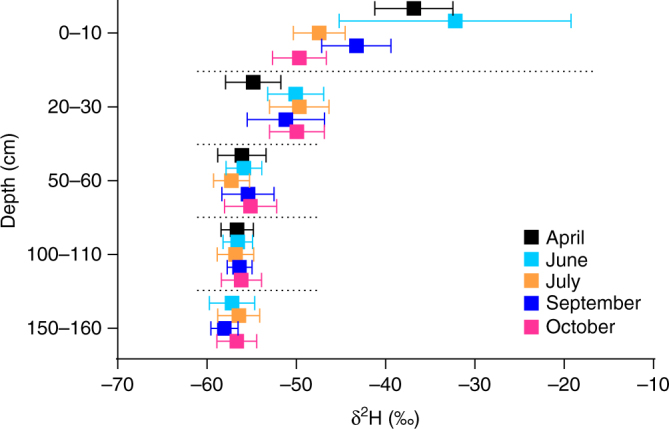

The 1-year monitoring of pore water δ2H (δ2Hpw) values in Dajiuhu reveals a clear depth pattern (Fig. 2). The δ2Hpw values in the surface 30 cm are highly variable, whereas the δ2Hpw values are stable at depths from 50 to 160 cm throughout the year. In 2015, the mean δ2Hpw value in the upper 30 cm (−46‰, n = 50) was significantly different (t-test, p < 0.0001) from the mean δ2Hpw value for 50–160 cm (−56‰; n = 69). Moreover, both the shallow and deep pore water mean δ2Hpw values were enriched relative to the yearly averaged δ2H value (−64‰) of Dajiuhu precipitation derived from the model of Bowen et al.15. Modeled annual δ2H values of precipitation must be considered cautiously when applied to a specific site, especially at higher altitude locations; however, the δ2H values of precipitation measured in June and July 2015 (Supplementary Table 1) are similar or even lower (avg. −82‰) than those estimated from models. Such a difference between the mean δ2Hpw and the actual rainfall δD data clearly indicates that the δ2H values of pore water are affected by evaporation.

Fig. 2.

Seasonal fluctuations of δ2H values in peat pore water in 2015. For each depth at a sampling time, five repeat water samples were collected. Error bars represent 1 s.d. of the batch samples (n = 5)

Peat-forming plants uptake peat water as the hydrogen source for lipid biosynthesis. Previous studies have shown that leaf wax δ2H values can be affected by various physiological and environmental factors, such as plant life forms, leaf wax production time and regeneration rate, and evapotranspiration16, 17. Leaf samples of dominant herb species (Carex argyi, Sanguisorba officinalis, Euphorbia esula) in Dajiuhu exhibited a mean n-C29 δ2H (δ2H29) value of −198‰ and a mean n-C31 δ2H value of −191‰ during the mature stage in 2010 (July–September). The root depths of these herb species range from 12 to 29 cm (n = 50 for each species). Assuming the mean δ2Hpw value of the surface 30 cm represents the annual average, the hydrogen isotope fractionation from the pore water to leaf wax n-C29 alkane (εalk/p) is −159‰. Such a εalk/p value is larger than a previously calculated value based on surface soil samples in eastern China (−130‰ to −140‰)18, and the biosynthesis value of forbs (−113‰ ± 31‰)16. These differences could result from the response of εalk/p to plant habitat conditions (e.g., relative humidity and its impact on evapotranspiration), seasonality of leaf wax production19, or differences among plant species16.

Peat deposits always have very high organic matter contents (normally >30%; Fig. 3). In such a terrestrial setting, in situ peat-forming plants contribute almost all long-chain n-alkanes to the underlying peat horizons20, 21. Consistent with this, in Dajiuhu, the mean δ2H29 value (−204‰)22 in surface peats (n = 26) is indistinguishable from those of the plant leaves, indicating an isotopic signal inherited from leaves, without a significant alteration during early diagenesis. Collectively, these observations mean that sedimentary leaf wax δ2H values record those of the peat-forming plants, which in turn appear to be strongly governed by both evaporative and evapotranspirative processes.

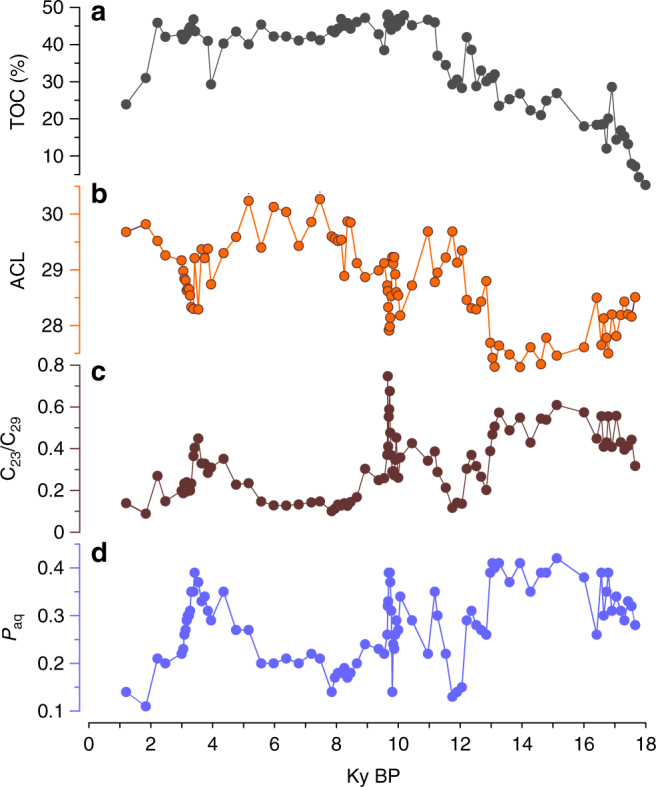

Fig. 3.

Variations of TOC and n-alkane ratios in the ZK-5 peat core. a TOC. b ACL. c C23/C29 ratio. d Paq

Leaf wax molecular ratios and δ2H and δ13C values in the peat core

Long-chain n-alkanes, with a strong odd-over-even predominance (carbon preference index (CPI) 2.2–9.4, averaging 5.9), are abundant in all sections of ZK-5 (Supplementary Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 2). The concentrations of total n-alkanes range from 25 to 860 μg g−1 dry peat, with an average of 250 μg g−1 dry peat (Supplementary Fig. 1). The average chain length (ACL) values range from 27.3 to 30.3 with an average of 28.8 in the whole peat core, with lower values during glacial intervals. The Sphagnum associated indices23, C23/C29 (the concentration of C23 relative to that of C29 n-alkane) and Paq (P-aqueous ratio), vary closely and exhibit quite low values from 9 to 3.5 ky (Fig. 3).

Since n-C29 and n-C31 are the predominant long-chain n-alkanes, and their δ2H values vary closely (Supplementary Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table 3), the former is used as a representative of leaf wax n-alkanes in the following discussion. Although n-C23 provides a useful additional record more reflective of Sphagnum plants23, its abundance was low in parts of the profile, preventing generation of a complete record. Over the whole peat core, δ2H29 values fluctuate between −188 and −233‰ (Fig. 4). δ2H29 values are relatively high during the last glacial, except for the interval from 13.2 to 11.5 ky, and generally lower during the Holocene, which is broadly consistent with other records from the region24, 25. After the onset of the Holocene, the δ2H29 values are relatively high varying from 11.5 to 10.3 ky and then become lower toward 7 ky. The interval of 7–3.5 ky is characterized by highly variable δ2H29 values, with some values being as high as those observed in the glacial. From 3.0 ky onwards, the δ2H29 values are relatively low and constant.

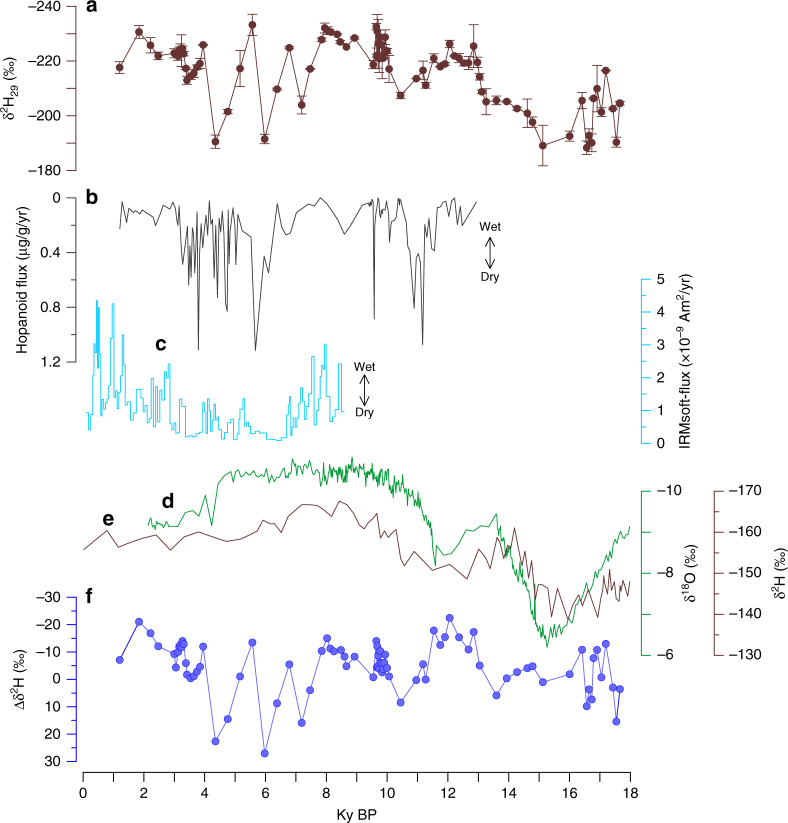

Fig. 4.

Comparisons of paleohydrological records. a ZK-5 δ2H29 values. b ZK-3 hopanoid flux12. c IRMsoft-flux in stalagmite HS410. d The calcite δ18O record from Sanbao Cave14. e The C29 and C31 n-alkane weight-averaged δ2H values of SO188-342KL37 over the last 18 ky. f The Δδ2H (between Sanbao Cave carbonate and ZK-5 leaf waxes). Error bars represent 1 s.d. of replicate runs

In the ZK-5 core, the δ13C values of n-C29 (δ13C29) and n-C31 (δ13C31) alkanes vary between −30.3 and −36.7‰ over the last 18 ky (Fig. 5 and Supplementary Fig. 2). The mean δ13C values of n-C29, and n-C31 are similar and relatively low (−32.7‰ and −32.0‰, respectively), indicating that they primarily derive from C3 plants26 and are consistent with the dominant flora contributors in peat sequences27. Over the last 18 ky, δ13C29 values vary by as much as 6‰, far exceeding the influence of changes in the concentration and carbon isotopic composition of atmospheric CO2 since the Last Glacial Maximum28. These δ13C29 variations normally occur rapidly. For example, in the interval from 4.5 to 3.5 ky, the δ13C29 values decrease by 5‰ in 100–200 years. These variations are larger than those observed in other investigations of Holocene peat vegetation29–31.

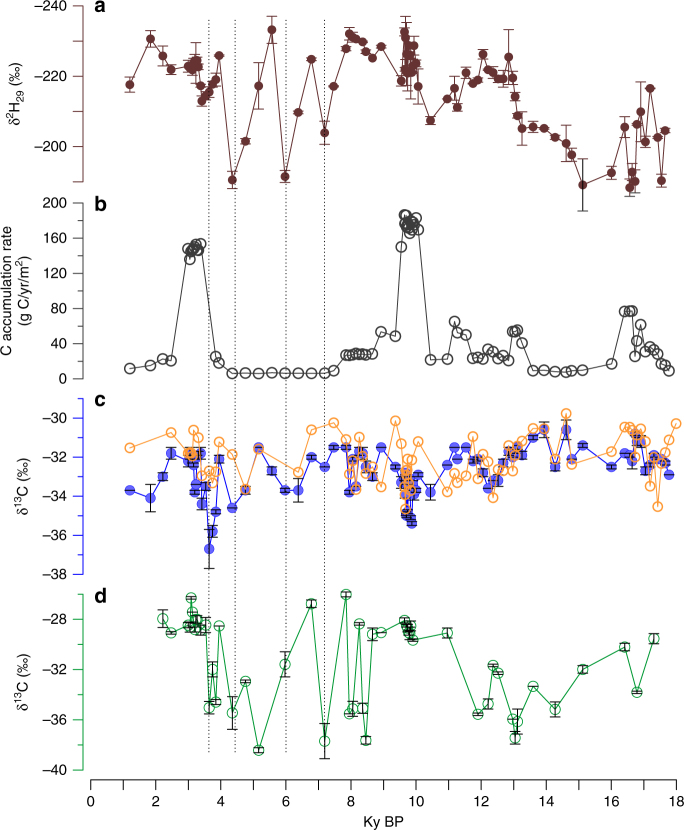

Fig. 5.

Comparisons of paleohydrological and carbon-related records in ZK-5 core. a δ2H29 values. b Carbon accumulation rate. c The δ13C values of C23 (unfilled circle) and C29 n-alkane (filled circle). d C29 ββ hopane. Error bars represent 1 s.d. of replicate runs. The dashed vertical lines infer the drier episodes

Hopane δ13C values in the peat core

Hopane concentrations in the ZK-5 core are high but variable. The distribution is dominated by the 17α,21β(H)-homohopane with an R-configuration at C-22 (C31 αβ) (Supplementary Fig. 3), consistent with a previous study in Dajiuhu on a different core (ZK-3)32 and other investigations of peat deposits29, 30, 33. Throughout the whole 18 ky, the δ13C values of the C31 αβ homohopane (δ13C31αβ) range from −22.5‰ to −30.9‰, which is 5–6‰ higher than those of the long-chain n-alkanes (Supplementary Fig. 4 and Supplementary Table 4). These isotopic signatures are consistent with previous reports from other peats29, 30, 33, 34. The 17β,21β(H)-norhopane (C29 ββ) is also present but less abundant than the 17α,21β(H)-homohopane; it generally has lower and more variable δ13C values than the C31 αβ hopane (Fig. 6). Over the whole 18 ky, the δ13C31αβ values generally increase, with relatively higher values occurring in the Holocene than in the deglacial. In contrast, the δ13C values of C29 ββ (δ13C29ββ) do not show any clear temporal trend, but are characterized by lower values from 15 to 11.5 ky and a highly variable interval from 9 to 3 ky (Fig. 5).

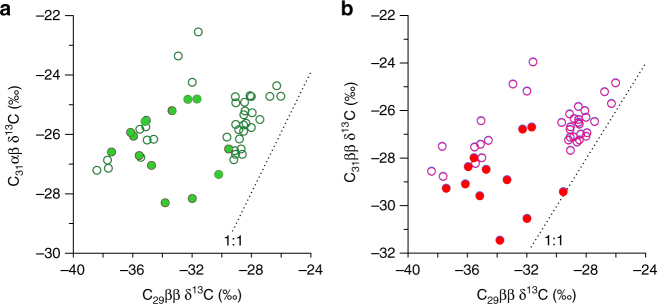

Fig. 6.

Cross-plots between the carbon isotope ratios of hopane homologues. a C29 ββ vs. C31 αβ hopane. b C29 ββ vs C31 ββ hopane. In each panel, samples from the glacial period are labeled as solid circles, while samples from the Holocene are labeled as open circles

Discussion

In this study, to explore the relationship between peatland carbon cycle and drier conditions, we combine leaf wax hydrogen and carbon isotope analyses on the same compounds in the same samples, which minimize the influence of other factors, such as vegetation source and sedimentological leads and lags that will affect, for example, microbial biomarkers8, 35.

Leaf wax δ2H values reveal both changes in water source on glacial–interglacial timescales and in response to Holocene dry intervals. During photosynthesis, terrestrial plants utilize soil water as their major H source, thereby recording the isotopic signatures of the source water, i.e., precipitation (δ2Hp). Leaf wax δ2H values are affected by additional factors, such as soil evaporation, and leaf transpiration, as well as plant-specific physiological and biochemical differences16. In peat deposits, in situ peat-forming plants, especially herbaceous subaerial plants (C3 plants), are the predominant contributor of long-chain n-alkanes35, which has also been confirmed by our previous study at Dajiuhu36. Such an inference is further supported by the n-alkane ratios, which reveal a predominance of vascular plants rather than Sphagnum during much of the Holocene and especially the last 9 ky (Fig. 3). Moreover, where biomarkers indicate changes in peat-forming plant distributions (Fig. 3 and see below), they are not correlated with leaf wax δ2H values and certainly do not appear to be driving variations in those values. This likely reflects the narrower range of sources for the high-molecular-weight leaf waxes, C3 herb plants that generally exhibit a narrow range of apparent hydrogen isotope fractionation between source water and wax lipids16. Thus, variations in plant life forms appear to be not an important control on δ2H variations in the ZK-5 δ2H29 sequence.

The broad match (r = 0.63, p < 0.001) between the ZK-5 δ2H29 sequence and the nearby Sanbao Cave (<50 km) δ18Ocarbonate record14 is consistent with vapor source being an important factor controlling the ZK-5 δ2H29 values on millennial timescales (Fig. 4). This inference is further supported by the first order similarity to the δ2Hwax record from the Bengal Bay37, an important vapor source for the East Asia region38.

However, prominent differences exist between the Sanbao calcite δ18O and the ZK-5 δ2H29 records, exemplified by large variations in the Δδ2H between the two sites (determined by converting the former into meteoric δ2H values, Fig. 4), especially during the 7.4–3 ky interval. This indicates that factors other than vapor source control the δ2H29 variations at Dajiuhu. Relative humidity, via its influence on evaporation and/or evapotranspiration, is a likely factor39. Peats are known to be particularly sensitive to changes in evaporative water balance40, and therefore, it is unsurprising that the Dajiuhu sequence exhibits variability not observed for the Sanbao Cave (for more detailed discussion, please refer the Supplementary Note 1). This is supported by the modern vertical profile of δ2Hp values, in which the upper layers are seasonally variable and 2H-enriched relative to deeper sections (Fig. 2) and precipitation water, presumably due to evaporative enrichment.

An interval of relatively drier conditions in the mid-Holocene Dajiuhu sequence is further supported by biomarker indicators of vegetation (Fig. 3). Leaf wax indicators of peat vegetation change must be used with caution41, but in the Dajiuhu peat sequence they exhibit significant changes that could reflect changes in the relative importance of Sphagnum species (high n-C23/n-C29 ratios and high Paq indices), which tend to dominate under wetter conditions23. Both indices are low over the past 9 ky and especially from 9 to 5 ky. This corresponds with but slightly precedes δ2H evidence for dry conditions, suggesting different climatic thresholds for vegetation change. Additional evidence for mid-Holocene aridity is provided by hopanoid abundances in the adjacent ZK-3 core (Supplementary Fig. 5). In the Dajiuhu peatland, hopanoids are mainly biosynthesized by aerobic bacteria, such that hopanoid concentrations serve as a proxy for water-table depth12, i.e., high-hopanoid abundances are indicative of a deeper water table and aerobic conditions. High abundances are associated with high Δδ2H29 values and low inferred relative humidity (Fig. 4), and both proxies indicate prolonged drier conditions at 11.6–10.6 ky, and 7–3 ky.

It is unclear if mid-Holocene drier conditions in the Dajiuhu peat sequence reflect a regional climate event and again we note that they are not documented in the Sanbao calcite δ18O record. However, a prolonged drying, and perhaps even drought, during the mid-Holocene has also been inferred from the IRMsoft-flux in speleothems of central China10. This proxy records the flux of soil-derived magnetic minerals and correlates with rainfall amount and intensity, and in particular ENSO-related storms. During 6.7–3.4 ky, IRMsoft-flux exhibits lower values, suggesting drier conditions10. A synthesis of paleoenvironmental investigations in the Poyang Basin, central China, also demonstrates drier conditions during 6.0–3.6 ka42. Modeling further supports the conclusion that drier conditions prevailed in central China during the mid-Holocene43, 44. A review of the mid-Holocene dry climate was recently presented in Liu et al.45.

The drier conditions during the mid-Holocene in central China contrast with the proposed wet interval of 8–3 ky in the north and the south of China11. A previous study interpreted such a spatial pattern as the influence of the western Pacific subtropical high (WPSH) and the associated ENSO variance11. During the mid-Holocene, the west–east surface sea temperature gradient was strong46, and thus the average position of WPSH would have moved north and west, such that the middle and lower reaches of the Yangtze River became dominated by downdraft. In fact, a similar mechanism has been proposed to interpret the negative relationship between precipitation in the middle and lower reaches of the Yangtze River and the summer monsoon intensity on decadal timescales47.

In the middle Holocene, multiple strong but brief positive Δδ2H shifts occurred (Fig. 4). The three most prominent δ2H intervals (20–40‰), centered at 7.2, 5.6, and 4.4 ky, correspond to high-hopanoid concentrations and inferred drier conditions12 (Fig. 4). The occurrence of prominent drier conditions in the middle Holocene provides an opportunity to explore the relationship between paleohydrological conditions and the peatland carbon cycle. The most direct evidence for this impact is documented by prolonged low carbon accumulation rates from about 9 to 3.5 ky (Fig. 5) in the ZK-5 core. This likely reflects a combination of decreased production and increased respiration, collectively leading to decreased carbon storage. The leaf wax and bacterial biomarker carbon isotopic signatures provide additional insights into changes in carbon cycling during the mid-Holocene dry interval. For C3 plants, leaf δ13C values are mainly governed by the air isotopic composition and isotope discrimination during photosynthesis (ɛp)48. Over the last 18 ky, atmospheric CO2 δ13C has changed by <1‰28, far too low to account for the shifts observed here. Moreover, although CO2 concentrations have changed slightly and these affect ɛp values, the effect is likely to have been small49, especially during the Holocene. Similarly, ɛp is sensitive to water stress with dry periods associated with decreased ɛp and, therefore, high plant δ13C values50. It is unexpected, therefore, that during the drier episodes of the mid-Holocene, leaf wax δ13C values always display negative excursions (Fig. 5). In addition, vegetation shifts inferred from palynogical data51 or leaf wax distributions (Fig. 3) do not match the δ13C29 variations.

Consequently, we argue that some of the large shifts in leaf wax δ13C values record changes in peatland carbon cycling, in particular increased plant uptake of respired CO2 during dry intervals. Dry intervals can be associated with enhanced peat degradation5, and previous studies have proposed that refixation of microbially respired CO2 is an important mechanism to maintain the higher primary productivity in peat bogs52–54. Such respired CO2 will have δ13C values close to the δ13C values of bulk OM55 and much lower than that of atmospheric CO256. Each of the three Holocene positive Δδ2H shifts is associated with a decrease in leaf wax δ13C values. Increased microbial respiration under warmer and drier climate conditions, by increasing the release of 13C-depleted CO2 available for photosynthesis56, 57, provides a mechanistic link between these observations. This is also consistent with the lower TOC contents and peat accumulation rates from 9 to 3.5 ky (Fig. 5). However, not all episodes of 13C depletion are associated with inferred drier intervals, indicating that the relationship between the two was likely nonlinear and/or that other factors govern some of the δ13C variability in the Dajiuhu peat.

Throughout the interval of inferred dry (but variable) conditions in the mid-Holocene, the amplitudes of the negative δ13Calk excursions become larger over time; consequently, a relatively minor positive Δδ2H excursion at 3.4 ky is associated with a large 4.6‰ δ13Calk shift (Fig. 5). Such a pattern suggests that the supply of respired CO2 could be sensitive to the cumulative effect of drying cycles, rather than simply linearly responding to a single event. Fenner and Freeman5 observed an increase of carbon losses from peat exposed to climatic variation and suggested that severe drying and subsequent rewetting would destabilize peatland carbon stocks. More contemporary studies emphasize the importance of drying–rewetting on peatland carbon dynamics58. As such, the nonlinear coupling of leaf wax carbon and hydrogen isotope ratios suggests that multiple drying cycles led to destabilization of Dajiuhu peat stock and pulses of organic matter respiration on centennial–millennial scales.

The influence of drier conditions on peatland carbon cycling is further evidenced by the carbon isotope shifts of bacterially derived hopanes. The controls on hopane carbon isotopic compositions are complex33, but previous work on peats suggests that the balance between heterotrophy (including the carbon isotopic composition of different substrates) and methanotrophy is crucial59. This is likely true in Dajiuhu, where hopanoids are mainly biosynthesized by aerobic bacteria (based on analyses of sqhC genes)12, 60. However, the C29 ββ hopane is both more 13C-depleted and more isotopically variable than the two C31 hopane isomers (Fig. 6 and Supplementary Fig. 4).

Previous studies reveal that the carbon isotope offset between C31 αβ homohopane and leaf wax n-alkanes is commonly between 4 and 6‰29. Consistent with this, in the modern surface peats collected from Dajiuhu in July 2012, the C31 αβ homohopane is 6–7‰ enriched relative to the C29 n-alkane. This offset suggests that hopane-producing bacteria in acidic peats are probably heterotrophic and utilizing isotopically heavy carbohydrates as their major substrate29, 33. However, from the late deglacial to the late Holocene, the δ13C31αβ values increase by 2–3‰ (Supplementary Fig. 4), whereas those of the leaf waxes decrease. This isotopic decoupling between the putative organic matter source and the consumer bacteria could arise from a number of factors, but we tentatively propose that it reflects the temperature control on substrate availability. Under cooler glacial conditions, we suggest that lower rates of respiration are associated with a reduced bias toward microbial assimilation of carbohydrates.

In contrast, δ13C values of the C29 ββ hopane, while also being lower in the glacial interval than the Holocene, exhibit a depth profile dominated by profound variability from 9 to 3 ky (in fact, the C31 hopanes also exhibit stronger variability during this interval, although less pronounced than for the C29 hopane). The dramatic variability appears to be broadly associated with the drier interval, with δ13C29ββ values decreasing by up to 10‰, to values as low as −40‰ (Fig. 5). The interval of lowest δ13C29ββ values is deeper than the drier interval and individual shifts are not directly correlated to shifts in Δδ2H; this is likely due to depth offset, due to bacteria living in subsurface layers. This would be especially true for transient dry events, which would allow hopanoid-producing bacteria to periodically thrive in aerated regions of deeper peat. Consequently, hopane carbon isotope signals appear to stratigraphically lead the dry events recorded by Δδ2H.

Shifts to such low δ13C29ββ values are difficult to explain via changes in organic matter sources (and in fact, in some cases, δ13C29ββ values are 4–6‰ lower than those of the n-alkanes), and instead likely reveal contributions from 13C-depleted methanotrophic bacteria during dry intervals. An increased methanotroph contribution during a dry interval seems counter-intuitive, as a low water table is likely associated with reduced rates of methanogenesis; however, it is similar to findings from a recent study of the Hongyuan peat sequence, southwest China, which revealed very low diploptene δ13C values during a dry interval of the mid-Holocene8. In that work, the low δ13C values were attributed to more diffusive flux of methane during dry intervals (as opposed to root-mediated transport), which could have facilitated growth of methanotrophs. Alternatively, the low δ13C29ββ values could arise from changes in the abundance of Sphagnum symbiotic methanotrophs61, which are known to produce <C31 hopenes62. However, such a possibility is not supported by the n-alkane ratios during the drier interval in the mid-Holocene, which reveal a low contribution from Sphagnum (Fig. 3). In addition, symbiotic methanotrophs associated with Sphagnum are more active in wetter conditions63.

By integrating multiple isotope records, this work provides new evidence for Chinese drier intervals on centennial–millennial timescales, as well as direct evidence that these drier conditions impacted the peatland carbon cycle. The difference between peat leaf wax δ2H values and the nearby cave calcite δ18O record reveals that prominent drier intervals, centered at 7.2, 5.6, 4.4, and 3.4 ky, occurred during the mid-Holocene in central China. This conclusion is reinforced by an absence of Sphagnum species during this interval and elevated abundances of hopanoids of putative aerobic bacteria origin. Corresponding to these drier intervals, carbon accumulation rates are very low and leaf wax δ13C values decrease markedly, opposite to the expected effect of decreased moisture, suggesting an increase in photosynthetic assimilation by the bog vegetation of isotopically depleted CO2 derived from microbial respiration within the peat. The magnitude of the leaf wax δ13C perturbations increases with successive drying cycles, indicating a cumulative effect of drier conditions on peatland carbon dynamics. At approximately the same time, carbon isotope ratios of bacterial biomarkers, especially those of C29 ββ hopane, become much more variable, providing further evidence of a perturbed carbon cycle, which we attribute to changes in the dynamics of methane production, flux, and consumption. Collectively, these processes resulted in a dramatic reduction in carbon accumulation rates, such that this work directly demonstrates that the peatland carbon cycle is sensitive to paleohydrological changes on long-term, centennial to millennial timescales.

Methods

Site description

Dajiuhu is a closed subalpine basin located in the middle reaches of the Yangtze River, central China. This basin has a mean elevation of 1730 m and a total area of 16 km2. Since the late deglaciation, peat developed in this basin to a depth of 2–3 m. The modern dominant peat-forming plants include sedge species, S. officinalis, and Sphagnum palustre. Water in this basin is drained through sinkholes to the Du River. Climate in this region is dominated by the Asian monsoon, with hot-wet summers and cold-dry winters, mean annual precipitation of 1560 mm and mean annual temperature of 7.2 °C. This region is located at the transition from the eastern lowland to the western highland, making it particularly sensitive to climate changes.

A 3-m core (ZK-5; 31°28′56″ N, 109°59′56″ E, a.s.l. 1758 m) was collected from Dajiuhu peatland in July 2013. The upper 2.6-m of ZK-5 core was peat, and the lower section was gray clay, presumably deposited under lacustrine conditions. Sub-samples of peat for biomarker analyses were collected from the upper 2.6 m peat layer, sliced at 1-cm intervals in the field.

AMS 14C dating and chronology

The chronology of ZK-5 is based on the 14C accelerator mass spectrometer (AMS) analyses of 20 organic sediments (Supplementary Table 5). AMS measurements were conducted at Beta AMS Lab (Miami, USA). Following the study of Zhou et al.64, the 90–300 μm fraction was sieved from the bulk samples, and then subjected to an acid–alkali–acid treatment before AMS analysis. The calendar age was calibrated using the clam age-depth model65 (Supplementary Fig. 6).

Lipid extraction and analysis

Freeze-dried peat samples were ground to pass a 60-mesh sieve (0.18 mm) and were ultrasonically extracted 6 × 10 min with dichloromethane/methanol (9:1, v/v). The apolar fraction was isolated by elution from a silica gel chromatographic column with hexane. Gas chromatography–mass spectrometry analysis for the apolar fraction was conducted with an Agilent 6890 gas chromatograph interfaced with an Agilent 5973 mass selective detector, with the instrumental conditions identical with the previous study32. Compound-specific hydrogen isotope compositions of n-alkanes were determined using a Trace GC coupled with a Delta V advantage isotope ratio mass spectrometer. To check the system stability, an n-alkane mixture (n-C23, n-C25, n-C27, n-C29, and n-C31 alkane) and the Indiana A4 mixture with known δ2H values were analyzed between every two samples. Squalane (δ2H −167‰) was used as the internal standard. Standard deviation for hydrogen isotope analysis was better than ±5‰, based on at least duplicate analyses. Results are reported in the delta notation (‰) relative to the Vienna Standard Mean Ocean Water standard.

Compound-specific carbon isotope analysis was conducted using a Finnigan Trace GC attached to a Finnigan Delta Plus XP isotope ratio mass spectrometer, equipped with a DB-5MS capillary column (30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 μm). The injector temperature was set at 300 °C. The GC oven temperature initiated at 50 °C (held 1 min), and then ramped to 220 °C at a rate of 10 °C min−1 (held 2 min), and further ramped to 300 °C at a rate of 2 °C min−1, and finally to 310 °C at a rate of 10 °C min−1 (held 20 min). Helium was used as the carrier gas (1.4 ml min−1). The combustion oven was set at 950 °C. Instrument performance was verified before and after each sample run using an n-alkane standard mixture with known δ13C values (n-C16−n-C30, Indiana University). Reproducibility for specific compounds was better than ±0.5‰ (standard deviation), based on at least duplicate analyses. Results are reported in the delta notation (‰) relative to the VPDB standard.

Calculations of the n-alkane ratios

The ACL, CPI, and Paq were calculated using the following equations:

| 1 |

| 2 |

| 3 |

Sampling of water and δ2H analysis

Peat pore waters were obtained from Dajiuhu during five sampling trips in 2015. These samples were collected using a MacroRhizon soil moisture sampler (with a length of 10 cm and pore size of 0.2 µm; Rhizosphere Research Products B.V., The Netherlands). The samplers were established at five different depths (0–10, 20–30, 50–60, 100–110, and 150–160 cm (except April, for which 150–160 cm was not collected)) at five locations. During June and July 2015, rainfall samples were collected using a 1000-ml flask, blocked with a ping-pong ball on the bottleneck. During water collection, olefin was added to prevent water evaporation.

The hydrogen isotopic compositions of the peat pore waters and rainfall were analyzed using an IWA-35-EP Liquid Water Isotope Analyzer (LGR, USA) at the State Key Laboratory of Biogeology and Environmental Geology. The analytical precision was better than 0.2‰ for δ18O and 0.6‰ for δ2H. Data for the batch of water samples collected in October 2015 have been published in Huang et al.22.

Total organic carbon concentration analysis

The peat samples were first freeze-dried and then ground to fine powder (<100 mesh) and homogenized. The total organic carbon concentration was measured on the Vario MICRO cube Element Analyzer.

Calculation of carbon accumulation rate

The method was followed reference7:

C accumulation rate (g C m−2 year−1) = peat accumulation rate (mm year−1)/1000 × ash-free bulk density (g m−3) × 0.52 × TOC (g g−1 dry weight) (4)

The ash-free bulk density utilized the mean value (0.12 g cm−3) from a nearby peat core retrieved from Dajiuhu66.

Calculation of Δδ2H

The Δδ2H values were calculated using Eqs. (5) and (6):

δ2Hp = 7.9 × δ18Oca + 8.2, (5)

where δ18Oca is the carbonate oxygen isotope values from Sanbao Cave11. Here we assume the carbonate δ18O record in Sanbao Cave is representative of precipitation oxygen isotope composition, and omit the combined effect of air temperature on precipitation δ18O values and of cave temperature on oxygen isotope fractionation during carbonate precipitation from drip water (ca. +0.05‰ ºC−1 in the eastern China67). The intercept (8.2) and slope (7.9) arise from the regional meteoric water line68. We then calculated Δδ2H using the equation:

Δδ2H = δ2H29 − εalk/w − δ2Hp − a (6)

where εalk/w is the hydrogen isotope fractionation between long-chain n-alkanes and precipitation, assumed to be −149‰ based on our recent study of surface peat in Dajiuhu22. The constant a represents the altitude effect on precipitation oxygen isotopes (−0.021‰ m−1 for Shennongjia Mountain69), applied to the 200 m altitude difference between Sanbao Cave and Dajiuhu.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are included in the supplementary information files.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the NSFC (41330103, 41472308), 111 Project (grant B08030), and the fundamental research funds for the central universities (CUGCJ1703). Z. Zhang from Shennongjia National Park Administration, Dr. X. Chen, Y. Gao, R. Wang, Y. Zhang, B. Zhao, Q. Song are thanked for their help in the field. Dr. X. Li and Y. Wang are thanked for the analysis of peat water δ2H composition.

Author contributions

X.H., J.X., and Y.G. performed the field work; J.X. and X.H. conducted biomarker and water isotope composition measurement and analysis. S.X. and X.H. designed the project. The manuscript was written by X.H., R.D.P., R.P.E. and S.X. with contributions from all authors.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41467-018-03804-w.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Gorham E. Northern peatlands: role in the carbon cycle and probable responses to climatic warming. Ecol. Appl. 1991;1:182–195. doi: 10.2307/1941811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yu Z. Northern peatland carbon stocks and dynamics: a review. Biogeosciences. 2012;9:4071–4085. doi: 10.5194/bg-9-4071-2012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Limpens J, et al. Peatlands and the carbon cycle: from local processes to global implications – a synthesis. Biogeosciences. 2008;5:1475–1491. doi: 10.5194/bg-5-1475-2008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.IPCC. Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (eds. Stocker, T. F. et al.) (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2013).

- 5.Fenner N, Freeman C. Drought-induced carbon loss in peatlands. Nat. Geosci. 2011;4:895–900. doi: 10.1038/ngeo1323. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang Y, Wang H, He JS, Feng X. Iron-mediated soil carbon response to water-table decline in an alpine wetland. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:15972. doi: 10.1038/ncomms15972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhao Y, et al. Peatland initiation and carbon accumulation in China over the last 50,000 years. Earth Sci. Rev. 2014;128:139–146. doi: 10.1016/j.earscirev.2013.11.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zheng Y, et al. Holocene variations in peatland methane cycling associated with the Asian summer monsoon system. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:4631. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.An ZS, et al. Asynchronous Holocene optimum of the East Asian monsoon. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2000;19:743–762. doi: 10.1016/S0277-3791(99)00031-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhu Z, et al. Holocene ENSO-related cyclic storms recorded by magnetic minerals in speleothem of central China. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2017;114:852–857. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1610930114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rao Z, Li Y, Zhang J, Jia G, Chen F. Investigating the long-term palaeoclimatic controls on the δD and δ18O of precipitation during the Holocene in the Indian and East Asian monsoonal regions. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2016;159:292–305. doi: 10.1016/j.earscirev.2016.06.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xie S, et al. Concordant monsoon-driven postglacial hydrological changes in peat and stalagmite records and their impacts on prehistoric cultures in central China. Geology. 2013;41:827–830. doi: 10.1130/G34318.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhao, K. et al. Mires in China (in Chinese) 559–562 (Science Press, Beijing, 1999).

- 14.Wang Y, et al. Millennial- and orbital-scale changes in the East Asian monsoon over the past 224,000 years. Nature. 2008;451:1090–1093. doi: 10.1038/nature06692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bowen GJ, Wassenaar LI, Hobson K. Global application of stable hydrogen and oxygen isotopes to wildlife forensics. Oecologia. 2005;143:337–348. doi: 10.1007/s00442-004-1813-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sachse D, et al. Molecular paleohydrology: interpreting the hydrogen-isotopic composition of lipid biomarkers from photosynthesizing organisms. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 2012;40:221–249. doi: 10.1146/annurev-earth-042711-105535. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sessions AL. Factors controlling the deuterium contents of sedimentary hydrocarbons. Org. Geochem. 2016;96:43–64. doi: 10.1016/j.orggeochem.2016.02.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rao Z, et al. Compound specific δD values of long chain n-alkanes derived from terrestrial higher plants are indicative of the δD of meteoric waters: evidence from surface soils in eastern China. Org. Geochem. 2009;40:922–930. doi: 10.1016/j.orggeochem.2009.04.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sachse D, Dawson TE, Kahmen A. Seasonal variation of leaf wax n-alkane production and δ2H values from the evergreen oak tree, Quercus agrifolia. Isot. Environ. Heal. Stud. 2015;51:124–142. doi: 10.1080/10256016.2015.1011636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nott CJ, et al. n-Alkane distributions in ombrotropic mires as indicators of vegetation change related to climatic variation. Org. Geochem. 2000;31:231–235. doi: 10.1016/S0146-6380(99)00153-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pancost RD, Baas M, van Geel B, Sinninghe Damsté JS. Biomarkers as proxies for plant inputs to peats: an example from a sub-boreal ombrotrophic bog. Org. Geochem. 2002;33:675–690. doi: 10.1016/S0146-6380(02)00048-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huang X, Meyers PA, Xue J, Zhang Y, Wang X. Paleoclimate significance of n-alkane molecular distributions and δ2H values in surface peats across the monsoon region of China. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2016;461:77–86. doi: 10.1016/j.palaeo.2016.08.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nichols JE, Booth RK, Jackson S, Pendall E, Huang Y. Paleohydrologic reconstruction based on n-alkane distributions in ombrotrophic peat. Org. Geochem. 2006;37:1505–1513. doi: 10.1016/j.orggeochem.2006.06.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Seki O, et al. Plant-wax hydrogen isotopic evidence for postglacial variations in delivery of precipitation in the monsoon domain of China. Geology. 2011;39:875–878. doi: 10.1130/G32117.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thomas EK, et al. Changes in dominant moisture sources and the consequences for hydroclimate on the northeastern Tibetan Plateau during the past 32 kyr. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2016;131:157–167. doi: 10.1016/j.quascirev.2015.11.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Collister JW, Rieley G, Stern B, Eglinton G, Fry B. Compound-specific δ13C analyses of leaf lipids from plants with differing carbon dioxide metabolisms. Org. Geochem. 1994;21:619–627. doi: 10.1016/0146-6380(94)90008-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ménot G, Burns SJ. Carbon isotopes in ombrogenic peat bog plants as climatic indicators: calibration from an altitudinal transect in Switzerland. Org. Geochem. 2001;32:233–245. doi: 10.1016/S0146-6380(00)00170-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schmitt J, et al. Carbon isotope constraints on the deglacial CO2 rise from ice cores. Science. 2012;336:711–713. doi: 10.1126/science.1217161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pancost RD, Baas M, van Geel B, Sinninghe Damsté JS. Response of an ombrotrophic bog to a regional climate event revealed by macrofossil, molecular and carbon isotopic data. Holocene. 2003;13:921–932. doi: 10.1191/0959683603hl674rp. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xie S, et al. Molecular and isotopic stratigraphy in an ombrotrophic mire for paleoclimate reconstruction. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 2004;68:2849–2862. doi: 10.1016/j.gca.2003.08.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yamamoto S, et al. Environmental influences over the last 16 ka on compound-specific δ13C variations of leaf wax n-alkanes in the Hani peat deposit from the northeast China. Chem. Geol. 2010;277:261–268. doi: 10.1016/j.chemgeo.2010.08.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huang X, et al. Environmental factors affecting the low temperature isomerization of homohopanes in acidic peat deposits, central China. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 2015;154:212–228. doi: 10.1016/j.gca.2015.01.031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pancost RD, van Geel B, Baas M, Sinninghe Damsté JS. δ13C values and radiocarbon dates of microbial biomarkers as tracers for carbon recycling in peat deposits. Geology. 2000;28:663–666. doi: 10.1130/0091-7613(2000)28<663:CVARDO>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Inglis GN, et al. Ecological and biogeochemical change in an early Paleogene peat-forming environment: linking biomarkers and palynology. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2015;438:245–255. doi: 10.1016/j.palaeo.2015.08.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pancost RD, et al. Archaeol as a methanogen biomarker in ombrotrophic bogs. Org. Geochem. 2011;42:1279–1287. doi: 10.1016/j.orggeochem.2011.07.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huang X, et al. Hydrologic influence on δ13C variations in long-chain n-alkanes in the Dajiuhu peatland, central China. Org. Geochem. 2014;69:114–119. doi: 10.1016/j.orggeochem.2014.01.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Contreras-Rosales LA, et al. Evolution of the Indian Summer Monsoon and terrestrial vegetation in the Bengal region during the past 18 ka. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2014;102:133–148. doi: 10.1016/j.quascirev.2014.08.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ding Y, Li C, Liu Y. Overview of the South China Sea Monsoon experiment. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 2004;21:343–360. doi: 10.1007/BF02915563. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kahmen A, Schefuβ E, Sachse D. Leaf water deuterium enrichment shapes leaf wax n-alkane δD values of angiosperm plants I: experimental evidence and mechanistic insights. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 2013;111:39–49. doi: 10.1016/j.gca.2012.09.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Holden J. Peatland hydrology and carbon release: why small-scale process matters. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A. 2005;363:2891–2913. doi: 10.1098/rsta.2005.1671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bush RT, McInerney FA. Leaf wax n-alkane distributions in and across modern plants: implications for paleoecology and chemotaxonomy. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 2013;117:161–179. doi: 10.1016/j.gca.2013.04.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xu J, et al. Geographic distribution of archaeological sites and their response to climate and environmental changes between 10.0-2.8 ka BP in the Poyang Lake Basin, China. J. Geogr. Sci. 2016;26:603–618. doi: 10.1007/s11442-016-1288-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jiang D, Tian Z, Lang X. Mid-Holocene net precipitation changes over China: model-data comparison. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2013;82:104–120. doi: 10.1016/j.quascirev.2013.10.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dallmeyer A, Claussen M, Wang Y, Herzschuh U. Spatial variability of Holocene changes in the annual precipitation pattern: a model-data synthesis for the Asian monsoon region. Clim. Dyn. 2013;40:2919–2936. doi: 10.1007/s00382-012-1550-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liu J, et al. Holocene East Asian summer monsoon records in northern China and their inconsistency with Chinese stalagmite δ18O records. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2015;148:194–208. doi: 10.1016/j.earscirev.2015.06.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Koutavas A, Joanides S. El Niño–Southern Oscillation extrema in the Holocene and Last Glacial Maximum. Paleoceanography. 2012;27:PA4208. doi: 10.1029/2012PA002378. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ding YH, Wang ZY, Sun Y. Inter-decadal variation of the summer precipitation in East China and its association with decreasing Asian summer monsoon. Part I: observed evidences. Int. J. Climatol. 2008;28:1139–1161. doi: 10.1002/joc.1615. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Farquhar GD, Ehleringer JR, Hubick KT. Carbon isotope discrimination and photosynthesis. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 1989;40:503–537. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pp.40.060189.002443. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schubert BA, Jahren AH. Reconciliation of marine and terrestrial carbon isotope excursions based on changing atmospheric CO2 level. Nat. Commun. 2013;4:1653. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Diefendorf AF, Mueller KE, Wing SL, Koch PL, Freeman KH. Global patterns in leaf 13C discrimination and implications for studies of past and future climate. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:5738–5743. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910513107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhu C, et al. A detailed pollen record of vegetation and climate changes in central China during the past 16000 years. Boreas. 2010;39:69–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1502-3885.2009.00098.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rydin H, Clymo RS. Transport of carbon and phosphorus compounds about Sphagnum. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. 1989;237:63–84. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1989.0037. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Turetsky MR, Wieder RK. Boreal bog Sphagnum refixes soil-produced and respired 14CO2. Ecoscience. 1999;6:587–591. doi: 10.1080/11956860.1999.11682559. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Smolders AJP, Tomassen HBM, Pijnappel HW, Lamers LPM, Roelofs JGM. Substrate-derived CO2 is important in the development of Sphagnum spp. New Phytol. 2001;152:325–332. doi: 10.1046/j.0028-646X.2001.00261.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Clymo RS, Bryant CL. Diffusion and mass flow of dissolved carbon dioxide, methane, and dissolved organic carbon in a 7-m deep raised peat bog. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 2008;72:2048–2066. doi: 10.1016/j.gca.2008.01.032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dorrepaal E, et al. Carbon respiration from subsurface peat accelerated by climate warming. Nature. 2009;460:616–619. doi: 10.1038/nature08216. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Flanagan LB, Syed KH. Stimulation of both photosynthesis and respiration in response to warmer and drier conditions in a boreal peatland ecosystem. Glob. Change Biol. 2011;17:2271–2287. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2486.2010.02378.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Knorr KH, Oosterwoud MR, Blodau C. Experimental drought alters rates of soil respiration and methanogenesis but not carbon exchange in soil of a temperate fen. Soil. Biol. Biochem. 2008;40:1781–1791. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2008.03.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pancost RD, Sinninghe Damsté JS. Carbon isotopic compositions of prokaryotic lipids as tracers of carbon cycling in diverse settings. Chem. Geol. 2003;195:29–58. doi: 10.1016/S0009-2541(02)00387-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gong L, et al. pH shaping the composition of sqhC-containing bacterial communities. Geomicrobiol. J. 2015;32:433–444. doi: 10.1080/01490451.2014.950363. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.van Winden JF, et al. Bacteriohopanepolyol signatures as markers for methanotrophic bacteria in peat moss. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 2012;77:52–61. doi: 10.1016/j.gca.2011.10.026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.van Winden JF, et al. Lipids of symbiotic methane-oxidizing bacteria in peat moss studied using stable carbon isotopic labelling. Org. Geochem. 2010;41:1040–1044. doi: 10.1016/j.orggeochem.2010.04.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kip N, et al. Global prevalence of methane oxidation by symbiotic bacteria in peat-moss ecosystems. Nat. Geosci. 2010;3:617–621. doi: 10.1038/ngeo939. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhou WJ, et al. Peat record reflecting Holocene climatic changes in the Zoigȇ Plateau and AMS radiocarbon dating. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2002;47:66–70. doi: 10.1360/02tb9013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Blaauw M. Methods and code for 'classical' age-modelling of radiocarbon sequences. Quat. Geochronol. 2010;5:512–518. doi: 10.1016/j.quageo.2010.01.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zhao Y, Hölzer A, Yu Z. Late Holocene natural and human-induced environmental change reconstructed from peat records in eastern central China. Radiocarbon. 2007;49:789–798. doi: 10.1017/S0033822200042661. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhang C, Yuan D. Study on continental paleoenvironmental proxy based on speleothems (drop stones) Adv. Earth Sci. 2001;16:374–381. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zheng S, Hou F, Ni B. Study on the hydrogen and oxygen isotope compositions of precipitation in China. Chin. Sci. Bull. 1983;28:801–806. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Luo P, et al. Empirical relationship between leaf wax n-alkane δD and altitude in the Wuyi, Shennongjia and Tianshan Mountains: implications for paleoalimetry: China. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2011;301:285–296. doi: 10.1016/j.epsl.2010.11.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are included in the supplementary information files.