Abstract

Pemphigoid gestationis (PG), also known as herpes gestationis, is a rare autoimmune blistering disease specific to pregnancy, which usually presents in the second or third trimesters and, in 15%–25% of cases, during the immediate postpartum period.1Although the ethiopathogeny of PG is not fully clarified, most patients develop antibodies against a 180 kDa transmembrane hemidesmosomal protein (BP180; BPAG2; collagen XVII).2 PG has a strong association with human leucocyte antigens DR3 and DR4.3

We report a case of a 29-year-old female patient with PG successfully treated with intravenous immunoglobulin.

Keywords: dermatology; obstetrics, gynaecology and fertility; obstetrics and gynaecology

Background

The rarity of PG and its limited treatment options make the approach and management of these patients difficult, highlighting the importance of reporting successful cases with a protracted course successfully treated with intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG).

Case presentation

A 29-year-old female patient, with gestational diabetes and hypothyroidism diagnosed in the first trimester of pregnancy, presented at the 32nd week of gestation with pruritic and urticarial plaques located in the navel area, with subsequent extension to abdomen and legs. Due to dermatosis exacerbation after delivering (at 39 weeks and 3 days), she was referred to dermatology. Physical examination revealed annular erythemato-oedematous plaques, associated with vesicles, tense bullae (clear fluid filled) and haemorrhagic crusts, dispersed throughout the limbs and trunk (figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1.

Erythemato-oedematous plaques located on the abdomen and thighs.

Figure 2.

Erythemato-oedematous plaques centred by vesicles and tense blisters (left thigh).

Investigations

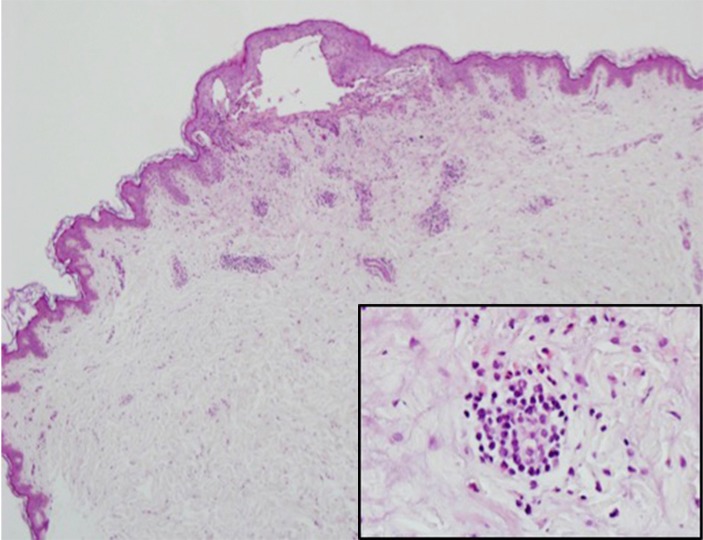

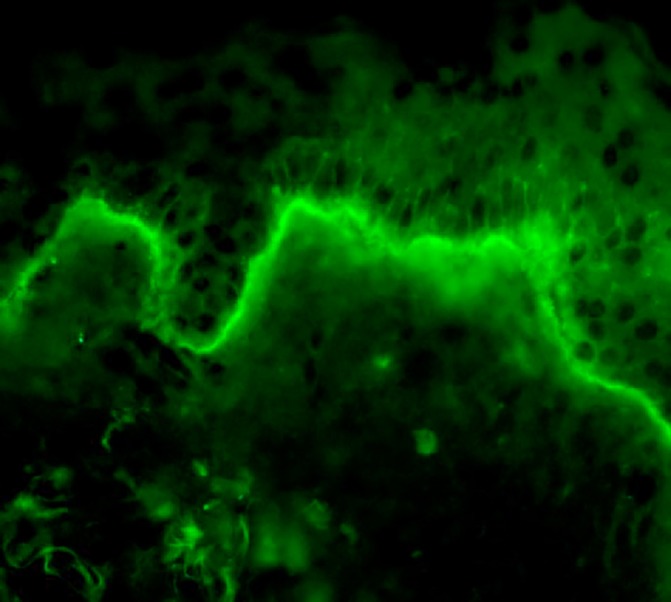

A clinical diagnosis of pemphigoid gestationis (PG) was made. This was supported by histology that showed a dermo-epidermal blister with conspicuous eosinophils within the blister and in the papillary dermis (figure 3). Direct immunofluorescence (IF) demonstrated a linear deposition of C3 along the basement membrane (figure 4).

Figure 3.

Skin with a dermo-epidermal blister containing polymorphonuclear neutrophils (H&E 100×). Inset: perivascular inflammatory infiltrate with eosinophils in the dermis (H&E 400×).

Figure 4.

Linear deposition of C3 along the dermo-epidermal junction (direct immunofluorescence).

Treatment

We decided to initiate treatment with oral prednisolone (0.5 mg/kg/day), oral antihistamine and topical steroids. After 3 days, the appearance of new lesions in the trunk and buttocks led to prednisolone increase to 0.75 mg/kg/day mg per day. After 1 week, given the evolution to generalised bullous eruption, pruritus worsening and diagnosis of gestational diabetes, we decided to start IVIG 25 g per day, during 5 days. The lesions started to improve, and the patient referred pruritus decreasing.

Outcome and follow-up

The patient completed six mensal IVIG cycles. A significant improvement in both pruritus and skin lesions was observed after the first course of IVIG. Oral corticotherapy was also gradually tapered. At the third cycle of IVIG, a complete remission was observed. The newborn did not develop cutaneous lesions. The patient remains asymptomatic 3 months after therapy.

Discussion

PG is rare, and its treatment is challenging, with a lack of controlled studies.4 Side effects can be harmless both to mother and baby, even though immunosuppressive drugs and plasmapheresis have been attempted in recalcitrant disease.5 Topical and oral corticosteroids are the mainstay of therapy,6 but when the disease persists, therapeutic options are limited.7 8 IVIG has been used to treat autoimmune skin blistering disorders, with successful suppression of blisters, allowing at the same time a reduction in the dose of corticosteroids.9 Given this, some authors reported the use of IVIG for treating PG, and it has occasionally been used in combination with immunosuppressants such as ciclosporin or azathioprine.10–15

Few cases of PG successfully treated with IVIG were reported in the literature, highlighting the interest of our case.

Learning points.

Pemphigoid gestationis (PG) clinical presentation and course may vary considerably, but in 75% of the patients occurs a flare at the time of delivery.

Neonatal disease occurs in up to 10% of cases and is typically mild with spontaneous resolution.

In patients’ refractory to conventional therapy, IVIG should be considered, given its safety profile.

PG tends to recur in subsequent pregnancies, usually with an earlier onset and more severe course.

Footnotes

Contributors: FTA, RS and CB contributed to the planning, conduction and report of the work. FTA, RS and JP contributed to the conception and design of the work. FTA and JP contributed to the acquisition of analysis and interpretation of the results. All authors are responsible for the overall content.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Hallaji Z, Mortazavi H, Ashtari S, et al. Pemphigoid gestationis: clinical and histologic features of twenty-three patients. Int J Womens Dermatol 2017;3:86–90. 10.1016/j.ijwd.2016.11.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ingen-Housz-Oro S. [Pemphigoid gestationis: a review]. Ann Dermatol Venereol 2011;138:209–13. 10.1016/j.annder.2011.01.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Al-Fouzan AW, Galadari I, Oumeish I, et al. Herpes gestationis (Pemphigoid gestationis). Clin Dermatol 2006;24:109–12. 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2005.10.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Semkova K, Black M. Pemphigoid gestationis: current insights into pathogenesis and treatment. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2009;145:138–44. 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2009.05.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sadik CD, Lima AL, Zillikens D. Pemphigoid gestationis: toward a better understanding of the etiopathogenesis. Clin Dermatol 2016;34:378–82. 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2016.02.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.PD L, Ralston J, Kamino H, et al. Pemphigoid gestationis. Dermatol Online J 2010;16:10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Intong LR, Murrell DF. Pemphigoid gestationis: current management. Dermatol Clin 2011;29:621–8. 10.1016/j.det.2011.06.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sävervall C, Sand FL, Thomsen SF. Pemphigoid gestationis: current perspectives. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol 2017;10:441–9. 10.2147/CCID.S128144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Czernik A, Toosi S, Bystryn JC, et al. Intravenous immunoglobulin in the treatment of autoimmune bullous dermatoses: an update. Autoimmunity 2012;45:111–8. 10.3109/08916934.2011.606452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ko BJ, Whang KU. Intravenous immunoglobulin therapy for persistent pemphigoid gestationis with steroid induced iatrogenic cushing’s syndrome. Ann Dermatol 2014;26:661–3. 10.5021/ad.2014.26.5.661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ruiz-Villaverde R, Sánchez-Cano D, Ramirez-Tortosa CL. Penfigoide gestacional. Respuesta terapéutica a inmunoglobulinas pre y postparto. Actas Dermo-Sifiliográficas 2011;102:735–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Doiron P, Pratt M. Antepartum intravenous immunoglobulin therapy in refractory pemphigoid gestationis: case report and literature review. J Cutan Med Surg 2010;14:189–92. 10.2310/7750.2009.09001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rodrigues CS, Filipe P, Solana MM, et al. Persistent herpes gestationis treated with high-dose intravenous immunoglobulin. Acta Derm Venereol 2007;87:184–6. 10.2340/00015555-0209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kreuter A, Harati A, Breuckmann F, et al. Intravenous immune globulin in the treatment of persistent pemphigoid gestationis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2004;51:1027–8. 10.1016/j.jaad.2004.07.052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sereno C, Filipe P, Marques-Gomes M, et al. Refractory herpes gestationis responsive to intravenous immunoglobulin: a case report. J Am Acad Dermatol 2005;52(3 Suppl 1):116 abstract: P1604. [Google Scholar]