Abstract

There is a scarcity of empirical data on the influence of initiatives supporting evidence-informed health system policy-making (EIHSP), such as the knowledge translation platforms (KTPs) operating in Africa. To assess whether and how two KTPs housed in government-affiliated institutions in Cameroon and Uganda have influenced: (1) health system policy-making processes and decisions aiming at supporting achievement of the health millennium development goals (MDGs); and (2) the general climate for EIHSP. We conducted an embedded comparative case study of four policy processes in which Evidence Informed Policy Network (EVIPNet) Cameroon and Regional East African Community Health Policy Initiative (REACH-PI) Uganda were involved between 2009 and 2011. We combined a documentary review and semi structured interviews of 54 stakeholders. A framework-guided thematic analysis, inspired by scholarship in health policy analysis and knowledge utilization was used. EVIPNet Cameroon and REACH-PI Uganda have had direct influence on health system policy decisions. The coproduction of evidence briefs combined with tacit knowledge gathered during inclusive evidence-informed stakeholder dialogues helped to reframe health system problems, unveil sources of conflicts, open grounds for consensus and align viable and affordable options for achieving the health MDGs thus leading to decisions. New policy issue networks have emerged. The KTPs indirectly influenced health policy processes by changing how interests interact with one another and by introducing safe-harbour deliberations and intersected with contextual ideational factors by improving access to policy-relevant evidence. KTPs were perceived as change agents with positive impact on the understanding, acceptance and adoption of EIHSP because of their complementary work in relation to capacity building, rapid evidence syntheses and clearinghouse of policy-relevant evidence. This embedded case study illustrates how two KTPs influenced policy decisions through pathways involving policy issue networks, interest groups interaction and evidence-supported ideas and how they influenced the general climate for EIHSP.

Keywords: Africa, Cameroon, Uganda, evidence informed health policy-making, health governance, influence, knowledge translation platforms, malaria, maternal and child health, MDGs

Key Messages

This comparative case study of four health system policy-making processes aiming at supporting achievement of the health MDGs, in which Evidence Informed Policy Network (EVIPNet) Cameroon and Regional East African Community Health Policy Initiative (REACH-PI) Uganda were involved between 2009 and 2011, uses a framework-guided thematic analysis, inspired by scholarship in health policy analysis and knowledge utilization to generate the empirical evidence on the actual influence of knowledge translation platforms (KTPs).

EVIPNet Cameroon and REACH-PI Uganda have influenced policy decisions through pathways involving policy issue networks, interest groups interaction and evidence-supported ideas. The coproduction of evidence briefs combined with tacit knowledge gathered during inclusive evidence-informed stakeholder dialogues helped to reframe health system problems, unveil sources of conflicts, open grounds for consensus and align viable and affordable options for achieving the health MDGs thus leading to decisions. The KTPs were change agents with positive impact on the understanding, acceptance and adoption of EIHSP because of their complementary work in relation to capacity building, rapid evidence syntheses and clearinghouse of policy-relevant evidence. The KTPs indirectly influenced health policy processes by introducing safe-harbour deliberations and intersection with contextual ideational factors by improving access to policy-relevant evidence.

The findings illustrate that efforts towards EIHSP through KTPs are worthwhile especially to achieve the health goals. It furthers the centrality of policy analysis and scientific information to health policy change and the urgency for health development stakeholders to pursue their efforts to establish and support KTPs and the alike. The coproduction of evidence briefs for policy shall be complemented by safe-harbour stakeholder dialogues in order to bring about change in health system governance.

Future scholarship on health systems governance shall incorporate performance indicators pertaining to the activities of KTPs and the alike including the criteria of ‘good governance’ of evidence in health policy and the pervasiveness of supra-national influences on health policy change and their impact on behaviours prevailing in polities across LMICs. Such scholarly investigation yields valuable contribution to inform the efforts towards learning health systems which are most needed to achieve the sustainable development goals.

Introduction

Targets set for the health Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) were not achieved by 2015 in most sub Saharan countries partially because of the so called ‘know-do’ gap in understanding and prioritizing health problems and in selecting and implementing health system interventions (Lavis et al. 2004; Green and Bennett 2007; Oxman et al. 2009; Lozano et al. 2011; WHO 2013; AFRO-WHO 2014). The 2013 World Health Report underscored the challenge that in spite of nearly a decade of calls and seed funds to support evidence-informed health systems in low- and middle- income countries (LMICs), sustained efforts were still needed to ensure that national health research systems optimally support evidence-informed policy-making processes related to ensuring universal health coverage (WHO 2008; Tetroe et al. 2008; Cordero et al. 2008; WHO 2013). Evidence Informed Policy Networks (EVIPNet), operating as knowledge translation platforms (KTPs) (i.e. partnerships among policymakers, researchers, civil society organization representatives, the media and other key stakeholders to institute evidence informed health system policy-making (EIHSP)) are cited as benchmarks in this endeavour (Lavis et al. 2012; Campbell 2013; WHO 2013).

However, there persists a scarcity of empirical evidence on the actual influence of KTPs operating in LMICs on health system policy-making (HSP) (Clar et al. 2011; Sutherland et al. 2012; Liverani et al. 2013; Oliver et al. 2014b), which contrasts with the growing evidence base on barriers to and facilitators of EIHSP (Lomas 2005; Lavis et al. 2008; Bennett et al. 2012; Orion 2011; Liverani et al. 2013; El-Jardali et al. 2014; Moat et al. 2014; Oliver et al. 2014a), as well as on the rising global stock of evidence relevant for HSP (Wilson et al. 2013). In addition, empirically tested conceptual frameworks and methods are needed to guide the impact evaluation of KTPs (Clar et al. 2011) and a renewed scholarship of ‘evidence to policy’ is called for as well as a paradigm shift from moralistic researcher-led perspectives towards more pragmatic and integrated perspectives (Oliver et al. 2014b). Within this context, scholars have been encouraged to apply sound theoretical frameworks and rigorous enquiry methods in order to investigate whether and how policy-relevant evidence intersects with HSP (Walt et al. 2008; Gilson and Raphaely 2008; James and Jorgensen 2009; Sutherland et al. 2012; Oliver et al. 2014b).

The integrated model for linking evidence to policy exemplified by KTPs purports to alter ‘receptor’-related factors such as training, organizational culture and structures. The latter encourage policy-makers to learn from interaction, to commission and learn from evidence syntheses and policy analyses, and to base policies on appraised evidence and a balance among other factors. It posits that the coproduction of evidence syntheses on priority health issues and convening of evidence-informed stakeholder deliberations, within a broader context of joint capacity building and of linkage and exchange, will improve the use of research evidence in HSP (Hanney et al. 2003; Jacobson 2003; Graham et al. 2006; Lomas 2005; Van Kammen et al. 2006; Lavis et al. 2006; Green and Bennett 2007; Ward et al. 2009).

Inspired by studies on EVIPNet (Campbell 2013; El-Jardali et al. 2014; Moat et al. 2014; Ongolo-Zogo et al. 2014) we sought to study the influence of two KTPs housed in government-affiliated institutions in Cameroon and Uganda on HSP to achieve the health MDGs. Both KTPs typically conduct stakeholder analyses and priority setting exercises, prepare evidence briefs on priority issues and convene evidence-informed stakeholder dialogues to deliberate on such issues, run rapid response units that provide evidence syntheses for stakeholders’ urgent needs and, administer clearinghouses of policy relevant evidence and, build capacities of stakeholders to demand, produce and use relevant evidence.

The study aims to assess whether and how the above mentioned KTPs have influenced: (1) health system policy-making processes and decisions aiming at supporting achievement of the health MDGs; and (2) the general climate for EIHSP. Specific objectives were to investigate whether and how the multifaceted activities undertaken by KTPs intersect with contextual factors such as—institutions, interests, ideas and external factors—by responding to the following questions:

Whether and how the KTP activities especially the evidence briefs and stakeholder dialogues have influenced directly the health policy decisions related to health MDGs?

Whether and how the KTP activities have influenced policy processes over time through intersections with contextual factors to achieve health MDGs?

What was the perceived impact of KTPs on the general climate for EIHSP in both countries?

Study context

The Cameroonian and Ugandan political systems present several commonalities. They feature presidential regimes established within the last 50 years, following colonization. The state boundaries were defined irrespective of the millennial traditional tribal kingdoms and ruling systems. The head of state and the ruling party have not changed since the mid 1980s. Veto and check and balance systems are similarly weak, with a powerful executive led by the president, who appoints the cabinet and almost all the senior technocrats. Presidential parties hold large majorities in parliaments. According to the World Bank, governance indices in both countries point to a fragile rule-of-the-law, the absence of fair and transparent electoral processes, and fragmented opposition parties. Both systems are featuring quasi monolithic and centralized systems ‘ruled’ by technocrats and cronyism, albeit with some efforts towards decentralization since the late 1990s. A neoliberal economy was imposed during the 1990s by international financial institutions through structural adjustment plans. In practice, the neoliberal paradigm is translated into ‘growth and employment’ and ‘national development’ plans promoting pro-poor economic growth strategies and targeted social safety nets. Both countries adhered to the declarations of the United Nations as well as those of regional political and economic bodies. International NGOs and bilateral donors are actively supporting health activities to achieve global commitments such as the health MDGs. Cameroon and Uganda featured broadly similar health systems and missed their targets set for MDGs 4 and 5 by 2015. Several higher health education and research institutions and networks are active. CSOs and the media are gaining prominence within the good governance initiatives established to buttress poverty reduction policies (Ongolo-Zogo et al. 2015).

Theoretical underpinnings

The reputation of policy-making for social development across sub-Saharan countries—as opaque due to weak and poorly democratic institutions (Carden 2009)—has been shifting over time as progress is made towards good governance (Ongolo-Zogo et al. 2015). We concur with scholars of the political economy of policy change that implementing change and using research evidence in HSP involve complex contextual interactions among the factors that influence policy-making, and research evidence constitutes only one input competing with these other factors, which are often grouped according to whether they relate to institutions, interests, ideas and external factors (Sabatier 1988; Grindle and Thomas 1989; Thomas and Grindle 1990; Dolowitz and Marsh 1996; Campbell 1998; Dolowitz and Marsh 2000; Campbell 2002; Lavis et al. 2002; John 2003, Oliver 2006, Garden 2009; Beland 2009; James and Jorgensen 2009; Bennett et al. 2012). We equally concur with others that the use of research evidence and the factors that influence this use, vary by both the context and the issues at hand (e.g. technical versus value-laden issues) (Beyer and Trice 1982; Hanney et al. 2003; Lomas 2005; Graham et al. 2006; Green and Bennett 2007; Brownson et al. 2009; Moat et al. 2013).

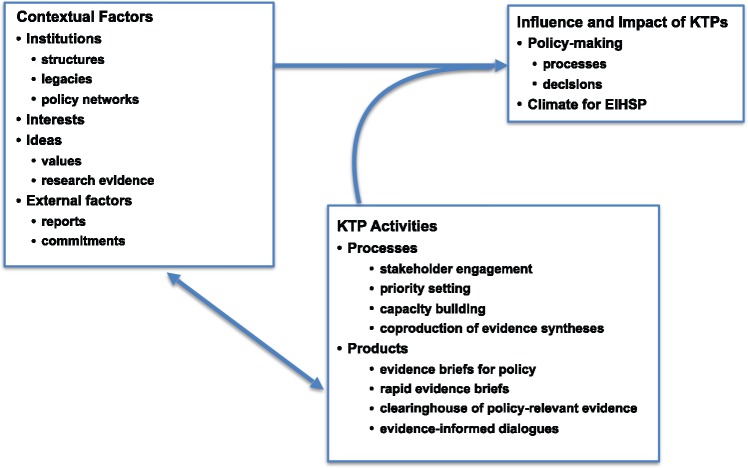

Mindful of the nascent conducive climate for EIHSP in Cameroon and Uganda and the historical account of EVIPNet Cameroon and REACH-PI Uganda (Ongolo-Zogo et al. 2014, 2015), we follow the calls (Anderson et al. 2005; Gilson and Raphaely 2008; Walt et al. 2008; Gilson 2012; Adam and de Savigny 2012; Oliver et al. 2014b; Yin 1999, 2009) to adopt a critical realist stance to interpret the complex interactions among the factors influencing HSP to achieve the health MDGs. We contend HSP is a political process and needs to be studied as such (Sabatier 1988; Sabatier and Jenkins-Smith 1999; John 2003; Oliver 2006; Beland 2009; Brownson et al. 2009; James and Jorgensen 2009). Moreover, influence in policymaking is not unidirectional but rather comprises path dependence and feedback loops (Lindquist 2001; Adam and de Savigny 2012; Paina and Peters 2011). Our approach was guided by the logical framework of KTP influence adapted by the authors from scholarship in political sciences, health policy analysis and knowledge utilization (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Logical framework for KTP influence

Methods

Design

This was a qualitative comparative embedded case study (Anderson et al. 2005; Yin 2009) combining documentary review and face-to-face semi-structured interviews with key informants. We opted for a case study design admitting health systems as complex adaptive systems comprising several embedded sub systems (Agyepong and Adjei 2008; Paina and Peters 2011).

Case selection

In line with our goal, we selected EVIPNet Cameroon and REACH-PI Uganda, which were launched in 2006 and considered the most active KTPs in sub Saharan Africa with significant but time-limited international financial and technical support (Campbell 2013, Ongolo-Zogo et al. 2014). They are housed in government-affiliated institutions, a teaching hospital linked to the Cameroon ministry of health and a public university in the case of Uganda. Based on their reports of activities, we selected two policy processes (embedded cases) in each country for which the KTPs have prepared evidence briefs and organized stakeholder dialogues in the period between January 2009 and December 2011. Mindful of the duration of the legislative electoral cycle in both countries (5 years) and of the typical HSP cycles (1–4 years), we set a minimum 3-year timeframe for observation after the stakeholder dialogue was organized. There were the efforts to improve governance for health district development and scale up malaria control interventions in Cameroon and, task shifting to optimize the roles of health workers for maternal and child health and improve access to skilled birth attendance in Uganda (Ongolo-Zogo et al. 2014).

Data sources

Standing as insiders leading KTP secretariats (POZ, NKS) and collaborators associated with both KTPs as co-investigators in KTP research and evaluation (JNL, GT), we have combined documents and semi-structured interviews with key stakeholders as data sources (Table 1).

Panel 1: Cases description

| Title | Prevailing contextual factors | Why and how the KTP get involved | Events during and after dialogues |

|---|---|---|---|

| Case 1: Improving governance for health district development in Cameroon |

|

|

|

| EVIPNet Cameroon prepared two evidence briefs and organized one stakeholder dialogue. The brief to foster stakeholder involvement was disseminated to a selected audience in 2010 while the second pertaining to good governance for health district development was pre-circulated to inform the dialogue convened in March 2011 by the ministry of public health. Both briefs were made publicly available on a website | |||

| Case 2: Scaling up malaria control interventions in Cameroon |

|

|

|

| Cameroon Coalition against Malaria (CCAM) (www.cameroon-coalition-malaria.org), a NGO linked to Malaria Consortium was identified as a champion. EVIPNet-Cameroon and CCAM co-produced an evidence brief and co-hosted a stakeholder dialogue in October 2010 with all the stakeholder groups represented at the Cameroon Roll Back Malaria committee in attendance | |||

| Case 3: Task shifting to optimize the roles of health workers for maternal and child health in Uganda |

|

|

|

| The evidence brief was prepared with technical assistance from the global EVIPNet support group and in collaboration with an ad hoc task force comprising senior officials from the ministry of health such as members of the health policy advisory committee (Nabudere 2011) Two stakeholder dialogues were co-hosted in May 2010 by the Uganda National Health Research Organization and REACH-PI Uganda with parliamentarians, health bureaucrats, representatives from UN agencies and CSOs, and researchers in attendance | |||

| Case 4: Improving access to skilled birth attendance in Uganda |

|

|

|

| REACH-PI Uganda secretariat and a task force of officials from the ministry of health co-produced the evidence brief (Nabudere, 2013) and co-hosted two stakeholder dialogues in August 2011. The attendance comprised health authorities, representatives from CSOs and private not-for-profit healthcare organizations, women members of parliament, UN agencies and researchers |

Documentary review

The purpose was to interpret the political context and provide a narrative historical account of each policy process by identifying the actors, describing the key steps in each policy process, and analysing the content of decisions or policies in relation to evidence briefs and stakeholder dialogues. Accordingly, we searched the websites of respective ministries of health for relevant policy documents pertaining to the topics of interest with the support of both KTP secretariats (e.g.; strategic plans, grants, reports of KTPs activities, evidence briefs and summaries of the dialogues including the lists of participants). In addition, we searched peer-reviewed papers from Medline to identify relevant scientific papers on the issues of interest during the period 2004–2014 using the following search terms: Cameroon, Uganda, research, health governance, malaria control, task shifting, maternal child health and skilled birth attendance.

Semi-structured interviews with stakeholders

We used techniques of stakeholder analysis (Gilson et al. 2012) and contribution mapping (Kok and Schuit 2012) to purposively sample informants from among KTP staff and the participants at the dialogues, based on their characteristics, roles, experiences and involvement in HSP, and their ability to elucidate a range of issues relevant to our research questions. The 54 interviewees were senior officials from the respective ministries of health—permanent secretaries, technical advisors, directors of planning, commissioners, policy analysts and national programme managers—as well as representatives from CSOs, donor agencies, journalists and researchers including KTP staff (Table 2). The interviewees were contacted to request their participation by an email that included an information sheet for the study, and they were then called back to check their availability for an interview. Prior to all the interviews, the explicit consent was obtained in writing using a standardized form. Interviews mostly took place in the interviewee’s office. The interviews, conducted in English in Uganda and in French and English in Cameroon, were audio recorded for 36 participants or recorded in writing for 18 participants declining the audio recording. All audio recordings were transcribed verbatim. Between June and December 2014, one of us (POZ), assisted by a research assistant in each country, conducted all the interviews, each time using the same guiding questions (see appendix one). A two-page summary sheet was prepared soon after each interview so as to capture a concise picture of its context and content, to serve as a checklist of outstanding items and issues, and to triangulate information and reflect on data saturation.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the stakeholders interviewed

| Stakeholder self-identified categories | Cameroon | Uganda |

|---|---|---|

| Government officials | 6 | 11a |

| Health care providers | 5a | 5a |

| Representatives of civil society organizations | 3 | 5a |

| Representatives of external donors | 3 | 4 |

| Media | 2 | 2 |

| Researchers | 7a | 9a |

Several interviewees self identified in more than one category.

Data analysis

The content analysis of documents and interview transcripts aimed to describe the context in which HSP and decisions to achieve health MDGs occurred and to identify the intersection of KTP activities with contextual factors and, to determine the perceived influence of KTP activities on HSP and country general climate for EIHSP. We used NVivo qualitative data analysis software (QSR International Pty Ltd. Version 10, 2014) to facilitate the documentary review. The framework-guided thematic coding approach was aligned to the logical framework for KTP influence derived from scholarship in political sciences, health policy analysis and knowledge utilization (Figure 1). We conceived of influence as a process guided by history, path dependence and feedback loops, and we described the nature of influence in terms of (1) direct influence on decision to change a policy/program or the decision not to change, (2) indirect influence through the intersection with contextual factors of HSP (e.g. broadening of policy horizons through sense making) (Lindquist 2001; Carden 2009; Paina and Peters 2011; Adam and de Savigny 2012). Institutions were defined as the structures, the political and health system decision-making culture and procedures arising from past decisions (policy legacies), and policy networks inclusive of government, parliament and civil society. Interests were referred to as the organized societal groups, bureaucrats or elected officials with perceived positive or negative incentives relating to the policy process. Ideas were defined as values about ‘what ought to be’ regarding health system and policy and perceptions on problem, as well as research evidence as illustrated in issue clarification, options framing and implementation considerations. External factors were categorized in terms of external donors influence, release of major reports and regional or global focus event or commitment (Campbell 1998, 2002; John 2003; Beland 2009; Lavis et al. 2012). We specifically looked at decisions or changes perceived as directly linked to KTPs activities in terms of institutional arrangements, power struggle amongst interest groups, ideational and external factors. We strived for reliability through a systematic and comprehensive maintenance of records and careful account of the analytical process. Information from interviews was triangulated across interviewees and with information from the documentary review. The influence on HSP was compared within countries and contrasted across cases and countries.

Results

Cases description

Panel 1 provides the narrative description of the four policy cases including the prevailing contextual features at the time the policy processes occurred, why and how KTPs were involved and the events during and after the stakeholder dialogues. The involvement of both KTPs were justified by the high priority of the issues in relation to achieving health MDGs. The KTP secretariats were engaged to prepare the evidence briefs in close collaboration with the « owners » of the issue from within the ministry of health (e.g. permanent secretary, malaria control programme manager, commissioners in charge of human resources and reproductive health).

Influence of KTPs

Overall, the KTPs had direct influence on decisions and indirect influence through intersection with contextual factors. Decisions were reached only when a policy entrepreneur (e.g. program manager, senior health official and health minister) seized the opportunity to align a priority health problem with stakeholder consensus palpable during the dialogues and affordable policy options and related implementation considerations suggested in evidence briefs. The co-produced evidence briefs favoured the interactions between national actors and the epistemic community fostering EIHSP and raising awareness on and use of systematic reviews. The processes (e.g. participatory priority setting, structured stakeholder analysis and co-production of evidence briefs) leading to inclusive safe-harbour evidence-informed stakeholder dialogues have altered contextual factors especially policy issue networks, interest groups interaction and prominence of evidence related ideas and contributed to enhance health governance and equity and to strengthen democratic processes. KTPs intersected with contextual factors by improving the capacities to access and to use relevant evidence. It equally promoted policy learning within emerging policy issue networks. The external factors of policy change were amongst others the global push for scaling up effective interventions to achieve the health MDGs and to improve public governance in response to the escalating poverty and unacceptable health inequities. Table 3 provides an overview of direct influence on decisions and the indirect influence over time through the intersection of KTPs processes with contextual factors.

Table 3.

Influence of KTP activities

| Cameroon |

Uganda |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Improving governance for health district development | Scaling up malaria control interventions | Task shifting to optimize the roles of health workers | Improving access to skilled birth attendance | |

| Direct influence of evidence briefs and stakeholder dialogues on decisions related to policy and research | ||||

| Decisions |

|

|

|

|

| Influence of KTPs activities over time through intersections with contextual factors | ||||

| Institutions | ||||

| Structures |

|

|

|

|

| Legacies |

|

|

|

|

| Policy issue networks |

|

|

|

|

| Interests | ||||

|

|

|

||

| Ideas | ||||

| Values |

|

|

||

| Research evidence |

|

|||

The direct influence on decisions

The two cases (e.g. malaria control, access to skilled birth attendance) with « straightforward go decisions » pertained to delivery arrangements and implementation strategies to scale up access to proven effective interventions. The evidence briefs provided new compelling frames of the system problems and sets of evidence-based policy options (from systematic reviews) embodying an equity lens as well as being attentive to relevant contextual implementation challenges. The causal model was primarily managerial (e.g. inappropriate allocation of human, material and financial resources to servicing health districts). In both cases, decision-making was incremental; options and implementation strategies suggested in the evidence briefs were adopted and implemented through a multi-stage approach. The evidence briefs enhanced the legitimacy and the voice of interest groups in both countries and furthered evidence-based practice in the fight against malaria. Access to skilled birth attendance attracted much sympathy and attention from the media, CSOs and politicians. Stakeholder dialogues furthered policy learning as they helped gathering decisive tacit knowledge, and uncovered grounds for consensus and sources of conflicts. As a consequence, new policy issue networks emerged (e.g. consortium of health NGOs and community based associations). The ear-marked funding opportunities from global health initiatives (GHI) facilitated convergence among stakeholders and prompted decisions by government officials and development partners.

On the other hand, the cases on health district governance and task shifting were more complex and value-laden thus bolstering the intricate nature of politics. In the case of Cameroon, the evidence briefs and the dialogue led to a « mixed decision » on strategies to improve governance for district development. The revision of the legal and regulatory framework in order to entrust greater role and responsibilities to mayors in health district governing bodies was delayed because it appeared politically complex and ‘risky’ due to dispersed interest-driven behaviours and power struggles opposing central level bureaucrats to district level managers on one hand and district level managers to elected mayors on the other hand. Instead, the availability of funds from the World Bank and the German cooperation prompted decisions purporting to boost stakeholder engagement and social control in health districts through « visible » activities (e.g. seminars for members of health district dialogue structures).

Despite the Government of Uganda having endorsed the regional commitment to regulate task shifting and the push by international NGOs and private not-for-profit organizations operating in Uganda, a « no go decision » for a written policy on task shifting was made. The emergence during and after the dialogue of vehement actors defending legacies in terms of ‘rule of the game’ for training, accrediting and licensing healthcare professionals and anchored ideas on ‘what ought to be’ in terms of quality and safety of healthcare influenced the course of events. This policy issue network with its broad membership was instrumental countering a written policy and instead advocating for decent working conditions and staff recruitment for health districts. Interviewees noted that the safe-harbour deliberations enabled health professionals and CSOs to voice their interests and gain new allies among media representatives and female politicians to criticize task shifting at times of sky-rocketing unemployment rates among trained professionals and ‘miserable’ wages served to civil servants in the health sector.

The push for greater room for CSOs in the development issues was exemplified in both countries. A CSO in Cameroon with international ties inspired a successful grant application informed by the evidence briefs. Similarly, a health consumers’ organization with international ties led a nationwide advocacy campaign using the rights-based approach to boost workforce recruitment and retention in order to improve access to skilled birth attendance in Uganda.

In all four cases, the critical elements leading to decisions were: (1) the risk assessment by senior managers and political leaders within the respective ministries of health; (2) the perceived locus of responsibility for the underlying factors of the challenges at stake; (3) the technical complexity of the issue, the affordability of the tabled evidence-based options and the feasibility of strategies to address implementation barriers and (4) the variation in political polarization translating into consensual or conflicting positions amongst stakeholders during the dialogues and thereafter. Overall, KTPs helped individuals making sense of the priority issues by largely disseminating (e.g. identified stakeholders, media and open access website) compelling evidence-based frames of health problems and affordable policy options embodying the equity lens thus inspiring new policy issue networks instilling and maintaining a pro-change mood.

The indirect influence through the intersection with contextual factors

KTPs intersected with contextual institutional, ideational and external factors by improving capacities to access and to use relevant evidence and by aligning national efforts to global calls for good governance and enhanced equity in health. The synergistic efforts of officials and KTP secretariats enabled resource mobilization from GHI and research funders either to develop resources and tools for EIHSP or to implement evidence-informed health operations. Both KTPs were co-implementing the SURE project (European commission grant to support the use of research evidence for African health systems) and as such were involved in framing and clarifying priority health system challenges through ad hoc task forces whose membership included the legitimate ‘owner’ as well as key actors identified during a structured stakeholder analysis. This approach purported to secure inasmuch exhaustive gathering of views and perceptions on the issue from actors and to expand the scope of interested parties thus providing room for emerging actors.

In addition, the inclusive approach to stakeholder dialogues embodying transparency and fairness changed the meaning and understanding of democratic deliberations on health priorities. KTPs were perceived as change agents enhancing the democratic culture in HSP through the redistribution of power resources and the alteration of interest groups interaction. Because people were talking altogether and reacting to the same evidence synthesis, stakeholder dialogues were perceived as drastically different from traditional consultative processes happening in both countries within the framework of participatory governance for growth and development. During the latter, policy proposals prepared by government officials and external donors and primarily submitted to stakeholders for endorsement typically open grounds for emotional and ideological debates partially because of unequal access to relevant evidence and divergent understanding. The hiring of a facilitator during the dialogue and the compliance to the Chatham House rule (http://www.chathamhouse.org) were perceived to further legitimate the voice of all interested parties.

The external technical assistance and guidance to appraise and to contextualize systematic reviews at the inception of the SURE project as well as capacity building activities to better access and use research evidence, and to appropriately engage stakeholders and to co-produce user-friendly evidence briefs for policy furthered policy transfer and learning across jurisdictions and bridged global epistemic communities and national actors thus altering the context of national HSP. Most interviewees admitted remarkable change in health actors’ awareness and attitude towards EIHSP especially as it aligns with global push for good governance and equitable health systems.

Comparing and contrasting the cases

The differences across cases pertained to the prevailing institutional arrangements for policy formulation and the issues at hand. In comparing HSP in Cameroon and Uganda, the institutional arrangements for policy formulation differ within the respective ministries of health, cabinet and parliament. In the case of Uganda, the health policy analysis unit and the health policy advisory committee established within the framework of the health SWAp in the 1990s laid the ground for systematic demand of policy-relevant evidence during HSP. The hierarchical consultative and decision-making chains were clearly outlined as opposed to the Cameroon ministry of public health where a policy analysis unit was missing notwithstanding the existing division of operations research and pathways for HSP and the referee roles of cabinet and parliament were opaque. The latter context opened a manoeuvring space for health bureaucrats, program managers and political leaders to set the agenda and mobilize ad hoc committees to prepare and push policy proposals. The launching of a health SWAp in May 2006 failed to rally participation from a majority of health development partners.

The prominence of interests groups differ across countries. The pharmacist union in Cameroon couldn’t mobilize further support to oppose community management of malaria while health professionals bodies succeeded to rally CSOs, parliamentarians and media to counter a written policy on task shifting in Uganda. In both countries, the availability of funds to support stakeholder consultations and to implement new decisions and programmes was equally critical. While financial contribution and influence from external funders were perceived to be generally higher in Uganda compared to Cameroon, in the four policy processes under scrutiny, the GHI and bilateral cooperation agencies played identical roles by providing easy-to-mobilize and ear-marked funds for program and project implementation.

The perceived impact on the general climate for EIHSP

KTPs were perceived broadly as change agents with positive impact on the understanding, acceptance and adoption of EIHSP because of their complementary work in relation to capacity building, rapid evidence syntheses through rapid response units and clearinghouse of policy-relevant evidence. They were perceived equally to fulfilling their purpose for both KTPs were established in response to global calls to foster EIHSP within the framework of the health MDGs. Their activities converged with global development rhetoric on health system strengthening, good governance and renewed public management. Stakeholders were appreciative and supportive of the KTPs because they enhanced the access to relevant evidence and empowered CSOs representatives including media to demand, access and appraise relevant evidence and to further articulate their advocacy campaigns, views and expectations. Views and perceptions on quality evidence and quality policy briefs were altered. The introduction of a rapid response service to respond to urgent needs of policy-relevant evidence was qualified by policy analysts as a dramatic change in the public policy-making landscape in Uganda. However, a majority of stakeholders expressed concerns regarding the sustainable funding for both KTPs.

Interviewees noted that clearer understanding of the attributes of EIHSP has broadened policy horizons and created new careers opportunity for policy analysts and young researchers. The emphasis on evidence syntheses (e.g. systematic reviews, evidence briefs) as best sources of evidence to inform policy options and of reliable monitoring and evaluation systems to inform problem definition induced demands for expertise in the then neglected domains of secondary research and secondary analysis of routine health information. The latter created incentives for researchers and research organizations, health bureaucrats and policy-makers, knowledge brokers and CSOs. An emerging community of EIHSP champions came into life. Further, universities in both countries incorporated short courses in KT into their programmes. An office in charge of KT was established at Makerere College of Health Sciences in Uganda.

In both countries, pressing evidence needs were uncovered in terms of costs, cost-effectiveness and cost-benefits analyses of policy options and implementation strategies suggested in the evidence briefs. The knowledge gaps identified in evidence briefs triggered research activities in both countries and boosted resources allocation for monitoring, evaluation and operational research in Cameroon.

Discussion

This comparative embedded case-study uncovered a novel understanding of the pathways of the influence of EVIPNet Cameroon and REACH-PI Uganda on HSP and the general climate for EIHSP. KTP activities had direct influence on policy decisions and indirect influence on policy processes through intersections with contextual factors. Both KTPs were perceived to have a positive impact on the general climate for EIHSP in terms of greater value of evidence synthesis, deepening of the meaning and understanding of EIHSP, and resources allocation and career opportunities.

Findings in relation to other studies

The policy processes examined here illustrate the primacy of the politics of HSP and shed light on the commonalities across countries notwithstanding the issue or the country economic wealth. The evidence briefs and the stakeholder dialogues facilitated the trade-offs by policy entrepreneur within prevailing institutional rules, problem attributes and socio-cultural values (James and Jorgensen 2009; Weible et al. 2009). The critical factors pertaining to the use of health services research in provincial health policy observed by Lavis et al. (2002) in Canada equally apply to Cameroon and Uganda with variations related to institutions, the issue at hand and the affordability of options. KTPs activities directly influenced the managerial bottlenecks pertaining to distributive policies while the influence was less potent on redistributive health system decisions. The lessons learned concur with previous studies on the value of evidence briefs and influence of stakeholder dialogues. Almost all the stakeholders exposed to the evidence briefs perceived them as accessible and prompting action (Moat et al. 2014, El-Jardali et al. 2014), our findings ascertain that stakeholders furthered their positive attitudes and moved to decision points following the dialogues. Our findings align with the two pathways of influence (Moat et al. 2013) of the evidence briefs on ‘ideas’ (e.g. a longitudinal pathway by initiating shifts in the stakeholders’ perceptions of the aspects of the health bottleneck and a cross-sectional interaction with existing ideas and institutions) resulting in an incremental policy change. As indicated by others, the issue characteristics such as whether the issue is familiar or not and its political polarization influenced the decisions and how the evidence was used (Beyer and Trice 1982; Hanney et al. 2003; Lomas 2005; Graham et al. 2006; Green and Bennett 2007; Brownson et al. 2009; Moat et al. 2013; Bennett and Howlett 1992).

Strengths

This study features four strengths. First, it aligns with recommendations for a renewed scholarship of ‘evidence to policy’ (Walt et al. 2008, Gilson and Raphaely 2008, James and Jorgensen 2009, Gilson 2012, Oliver et al. 2014b) by its design as a multiple comparative case study using a systems thinking lens with a cross country scope (Gilson and Raphaely 2008; Walt et al. 2008; Gilson 2012; Moat et al. 2013). Second, it generates empirical evidence on the influence of KTP activities on priority health system challenges and policy decisions and the system level intersections and effects of theory-driven strategies to facilitate the uptake of research into HSP in LMICs. Third, it applies an analytical framework furthering political sciences informed perspectives on KTPs to identify variables influencing decision-making in polities with reputedly opaque decision-making (Carden 2009) thus contributing a realist and pragmatic analytical framework to assess the influence of KTPs in LMICs (Lavis et al. 2006; Green and Bennett 2007; Gilson and Raphaely 2008; Walt et al. 2008; James and Jorgensen 2009; Clar et al. 2011, Liverani et al. 2013, Oliver et al. 2014b). This attempt furthers the framework developed by Lavis et al. (2006) to assess country efforts to link research to policy. We herein illustrate that combining Lavis framework with techniques of stakeholder analysis (Gilson et al. 2012) and contribution mapping (Kok and Schuit 2012) can furthered the descriptive categories for efforts engaged by a given country (e.g. systematic identification of actors and their interaction, exploration of actors views and perceptions on the influence of KTP) and enable the comprehensive assessment of the influence of KTP on HSP. Fourth, this study illustrates how KTPs enacted nascent policy issue networks to boost the achievement of health MDGs and uncovered potential coalitions, policy brokers and belief systems at play although their stability could not be assessed due a relatively short period of observation (Sabatier 1988; Sabatier and Jenkins-Smith 1999; Weible et al. 2009).

Limitations

A few limitations pertaining to time, access to administrative and media archives and access to politicians are embedded in this study. First, the policy processes were described based on 3- to 5-year period of observation as opposed to previous scholarship recommending at least a 10-year period (Sabatier 1988; Sabatier and Jenkins-Smith 1999; Agyepong and Adjei 2008). Second, the poor administrative archiving infrastructures including the lack of open access to minutes of senior or top management meetings in ministries of health and the absence of institutions devoted to policy and program evaluation restricted the depth and breadth of this enquiry. Only relevant policy documents publicly available were analysed thus failing to capture the power struggles arising at the interface between ministry of health and cabinet and between cabinet and parliament. Due to the research budgetary constraints and the absence of comprehensive online media archiving systems in Cameroon as opposed to Uganda, we did not include media analysis to assess the public opinion perspective. Media analyses are reputedly sound methods to capture political struggles in elitist and pluralist systems (Gilson 2012). Third, parliamentarians, ministers and stakeholders with informal/confidential political roles were not accessible. Finally, the retrospective tone of this enquiry might have suffered from time recall-related bias from interviewees and the risk of interviewees ‘rewriting the history’ in relation to social desirability of EIHSP and national moods towards good governance for development (Ongolo-Zogo et al. 2015). To account for the latter, we consistently triangulated data across informants and data sources and contributed our collective knowledge as insiders to ensure as much neutrality as achievable.

Implications for policy and practice

The findings illustrate that efforts towards EIHSP through KTPs are worth especially to strengthen health systems. This study furthers the centrality of policy analysis and scientific information to health policy change and the urgency for development actors to pursue their efforts to establish and support KTPs and the alike. The co-production of evidence briefs for policy shall be complemented by safe-harbour stakeholder dialogues in order to enhance the prospects for evidence-informed decisions and to improve health governance. The complementary work of KTPs in building capacities to use policy-relevant evidence and maintaining clearinghouses of health system evidence is worth considering as a priority investment when strategizing for health system strengthening in LMICs. It is critical that all health stakeholders encourage and support mechanisms to warrant open access to administrative archives in order to strengthen social control over and general public oversight on health decision-makers on one hand and lay the ground for in-depth health policy analysis that will benefit citizens and tax payers, policy-makers, and researchers on the other hand (Lavis et al. 2002; Sabatier 1988; Agyepong and Adjei 2008; Gilson and Raphaely 2008; Walt et al. 2008; James and Jorgensen 2009; Oliver et al. 2014b).

Implications for research

This documentation of the pathways through which KTPs enlighten HSP has implications for research. First, scholarship on health governance in LMICs needs to incorporate performance indicators pertaining to the activities of KTPs and the alike. EIHSP shall be conceived of as a belief system—‘sets of value priorities and causal assumptions about how to realize them’ (Sabatier 1988) and its scholarship shall integrate the broader dimension of governance especially to uncover the meanings and attributes of ‘good governance’ of evidence during HSP (Hawkins and Parkhurst 2015). Because most health system bottlenecks in LMICs exhibit technical attributes including quantifiable indicators to assess the current state of affairs and, are amenable to scientific reasoning on their causal mechanisms above socio-cultural values and economic considerations, we suggest to further investigate the interdependencies of emerging policy issue networks in relation to the diversity of national and supranational institutions, interests and ideas at play. Especially, scholars shall investigate the national-global interface to comprehend the supra-national influences (Oliver 2006; Ssengooba et al. 2011; Lavis et al. 2012; Nabyonga Orem et al. 2013) on HSP change (Dolowitz and Marsh 1996, 2000; James and Jorgensen 2009) and their impact on behaviours prevailing in polities in LMICs (Carden 2009, Ongolo-Zogo et al. 2015). Such investigation yields valuable contribution to inform the efforts towards learning health systems which are most needed to achieve the sustainable development goals (Buse et al. 2015). Second, there are pressing evidence needs regarding the affordability of policy options and implementation strategies and scholars are called upon to pursue efforts to augment the global stock of evidence relevant for HSP particularly economic evaluations targeting LMICs (Wilson et al. 2013). Third, this study offers a pragmatic response to the debate on the appropriate evaluative framework of knowledge brokerage institutions in LMICs (Clar et al. 2011; Bennett et al. 2012; Oliver et al. 2014b), the logical framework presented in this study shall inform future scholarship of health policy change and policy-oriented learning in LMICs.

Conclusion

Two KTPs housed in government-affiliated institutions have influenced policy decisions through pathways involving policy issue networks, interest groups interaction, redistribution of power resources and evidence-supported ideas, all within prevailing political arrangements and external factors for HSP. The findings support the need to further develop KTPs and the alike to strengthen health systems within the framework of sustainable development goals.

Ethics: This study was approved by the higher degrees research and ethics committee at Makerere University, College of Health Sciences, Kampala, Uganda and the Division of the Health Operations Research of the Ministry of Health in Cameroon.

Funding

The research was supported by the International Research Chair Initiative in Evidence-Informed Health Policies, and the Canadian Global Health Research Initiative through the joint McMaster University – Makerere University Doctoral Program on Health Policy and Knowledge Translation.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

References

- AFRO-WHO. 2014. Annual report of the WHO work in the African Region, Brazzaville, Congo.

- Adam T, de Savigny D.. 2012. Systems thinking for strengthening health systems in LMICs: need for a paradigm shift. Health Policy and Planning 27: iv1–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agyepong IA, Adjei S.. 2008. Public social policy development and implementation: a case study of the Ghana national health insurance scheme. Health Policy and Planning 23: 150–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson AR, Crabtree FB, Steele JD, McDaniel RRJ.. 2005. Case study research: the view from complexity science. Qualitative Health Research 15: 669–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baine OS, Kasangaki A.. 2014. A scoping study on task shifting; the case of Uganda. BMC Health Services Research 14: 184..http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6963/14/184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beland D. 2009. Ideas, institutions and policy change. Journal of European Public Policy 16: 701–18. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett C, Howlett M.. 1992. The lessons of learning: reconciling theories of policy learning and policy change. Policy Sciences 25: 275–94. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett S, Corluka A, Doherty J. et al. 2012. Influencing policy change: the experience of health think tanks in low- and middle-income countries. Health Policy and Planning 27: 194–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beyer JM, Trice HM.. 1982. The utilization process: a conceptual framework and synthesis of empirical findings. Administrative Science Quarterly 27: 591–622. [Google Scholar]

- Brownson RC, Fielding JE, Maylahn CM.. 2009. Evidence-based public health: a fundamental concept for public health practice. Annual Review of Public Health 30: 175–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buse K, Hawkes S., Hawkes, 2015. Health in the sustainable development goals: ready for a paradigm shift? Globalization and Health 11: 13.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell JL. 1998. Institutional analysis and the role of ideas in political economy. Theory and Society 27: 377–409. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell JL. 2002. Ideas, politics, and public policy. Annual Review of Sociology 28: 21–38. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell S. 2013. EVIPNet Africa: Lessons Learned 2006–2012. Geneva: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Carden F. 2009. Knowledge to Policy: Making the Most of Developmental Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: International Development Research Centre, Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Clar C, Campbell S, Davidson L, Graham W.. 2011. Systematic Review: What Are the Effects of Interventions to Improve the Uptake of Evidence from Health Research into Policy in Low and Middle-Income Countries? Aberdeen: DFID, University of Aberdeen and University of East Anglia; http://r4d.dfid.gov.uk/PDF/Outputs/SystematicReviews/SR_EvidenceIntoPolicy_Graham_May2011_MinorEditsJuly2011.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Cordero C, Delino R, Jeyaseelan L. et al. , 2008. Funding agencies in low- and middle-income countries: support for knowledge translation. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 86: 524–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolowitz D, Marsh D.. 1996. Who learns what from whom? A review of the policy transfer literature. Political Studies 44: 343–57. [Google Scholar]

- Dolowitz D, Marsh D.. 2000. Learning from abroad: the role of policy transfer in contemporary policy-making. Governance: An International Journal of Policy and Administration 13: 5–24. [Google Scholar]

- El-Jardali F, Lavis J, Moat K, Pantoja T, Ataya N.. 2014. Capturing lessons learned from evidence-to-policy initiatives through structured reflection. Health Research Policy and Systems 12: 2..http://www.health-policy-systems.com/content/12/1/2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilson L, (ed), 2012Health Policy and Systems Research: A Methodology Reader. Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research, Geneva: World Health Organization, 21–60. [Google Scholar]

- Gilson L, Raphaely N.. 2008. The terrain of health policy analysis in low and middle income countries: a review of published literature 1994–2007. Health Policy and Planning 23: 294–307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilson L, Erasmus E, Borghi J. et al. 2012. Using stakeholder analysis to support moves towards universal coverage: lessons from the SHIELD project. Health Policy and Planning 27: i64–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham ID, Logan J, Harrison MB. et al. 2006. Lost in knowledge translation: time for a map? Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions 26: 13–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green A, Bennett S (eds). 2007. Sound Choices: Enhancing Capacity for Evidence-Informed Health Policy. Geneva: World Health Organization, 37–56 [Google Scholar]

- Grindle MS, Thomas JW.. 1989. Policy makers, policy choices and policy outcomes: the political economy of reform in developing countries. Policy Sciences 22: 213–48. [Google Scholar]

- Hanney SR, Gonzalez-Block MA, Buxton MJ, Kogan M.. 2003. The utilisation of health research in policy-making: concepts, examples and methods of assessment. Health Research Policy and Systems 1: 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins B, Parkhurst J.. 2015. The ‘good governance’ of evidence in health policy. Evidence and Policy 12: 575. [Google Scholar]

- James TE, Jorgensen PD.. 2009. Policy knowledge, policy formulation, and change: revisiting a foundational question. Policy Studies Journal 37: 141–62. [Google Scholar]

- John P. 2003. Is there life after policy streams, advocacy coalitions, and punctuations: using evolutionary theory to explain policy change? Policy Studies Journal 31: 481–98. [Google Scholar]

- Kok MO, Schuit AJ.. 2012. Contribution mapping: a method for mapping the contribution of research to enhance its impact? Health Research Policy and Systems 10: 21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavis JN, Ross SE, Hurley JE. et al. 2002. Examining the role of health services research in public policymaking. The Milbank Quarterly 80: 125–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavis JN, Posada FB, Haines A, Osei E.. 2004. Use of research to inform public policymaking. Lancet 364: 1615–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavis JN, Lomas J, Hamid M, Sewankambo NK.. 2006. Assessing country-level efforts to link research to action. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 84: 620–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavis JN, Oxman AD, Moynihan R, Paulsen EJ.. 2008. Evidence-informed health policy 1: synthesis of findings from a multi-method study of organizations that support the use of research evidence. Implementation Science 3: 53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavis JN, Røttingen JA, Bosch-Capblanch X. et al. 2012. Guidance for evidence-informed policies about health systems: linking guidance development to policy development. PLoS Medicine 9: e1001186.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindquist EA. 2001. Discerning Policy Influence: Framework for a Strategic Evaluation of IDRC-Supported Research. Victoria, Australia: School of Public Administration, University of Victoria. [Google Scholar]

- Liverani M, Hawkins B, Parkhurst JO.. 2013. Political and institutional influences on the use of evidence in public health policy, a systematic review. PLoS One 8: e77404.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lomas J. 2005. Using research to inform healthcare managers’ and policy makers’ questions: from summative to interpretive synthesis. Healthcare Policy 1: 55–71. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lozano R, Wang H, Foreman KJ. et al. 2011. Progress towards Millennium Development Goals 4 and 5 on maternal and child mortality: an updated systematic analysis. Lancet 378: 1139–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mbacham WF, Mangham-Jefferies L, Cundill B. et al. 2014. Basic or enhanced clinician training to improve adherence to malaria treatment guidelines: a cluster-randomised trial in two areas of Cameroon. Lancet Global Health 2: e346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moat AK, Lavis JN, Abelson J.. 2013. How contexts and issues influence the use of policy-relevant research syntheses: a critical interpretive synthesis. The Milbank Quarterly 91: 604–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moat AK, Lavis JN, Clancy SJ, El-Jardali F, Pantoja T. and the Knowledge Translation Platform Evaluation study team, 2014. Evidence briefs and deliberative dialogues: perceptions and intentions to act on what was learnt. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 92: 20–8. http://dx.doi.org/10.2471/BLT.12.116806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nabudere H, Asiimwe D, Mijumbi R.. 2011. Task shifting in maternal and child health care: an evidence brief for Uganda. International Journal of Technology Assessment in Health Care 27: 173–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nabudere H, Asiimwe D, Amandua J.. 2013. Improving access to skilled attendance at delivery: a policy brief for Uganda. International Journal of Technology Assessment in Health Care 29: 207–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nabyonga Orem J, Marchal B, Kaawa Mafigiri D. et al. 2013. Perspectives on the role of stakeholders in knowledge translation in health policy development in Uganda. BMC Health Services Research 13: 324.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver K, Innvaer S, Lorenc T, Woodman J, Thomas J.. 2014a. A systematic review of barriers to and facilitators of the use of evidence by policymakers. BMC Health Services Research 14: 2..http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6963/14/2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver K, Lorenc T, Innvaer S.. 2014b. New directions in evidence-based policy research: a critical analysis of the literature. Health Research Policy and Systems 12: 34.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver TR. 2006. The politics of public health policy. The Annual Review of Public Health 27: 195–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ongolo-Zogo P, Lavis NJ, Tomson G, Sewankambo N.. 2014. Initiatives supporting evidence informed health system policymaking in Cameroon and Uganda: a comparative historical case study. BMC Health Services Research 14: 612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ongolo-Zogo P, Lavis NJ, Tomson G, Sewankambo N.. 2015. Climate for evidence informed health system policymaking in Cameroon and Uganda before and after the introduction of knowledge translation platforms: a structured review of governmental policy documents. Health Research Policy and Systems 13: 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orton L, Lloyd-Williams F, Taylor-Robinson D. et al. 2011. The use of research evidence in public health decision making processes: systematic review. PLoS One 6: e21704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oxman AD, Lavis JN, Lewin S, Fretheim A.. 2009. SUPPORT Tools for evidence informed health Policymaking (STP) 1: What is evidence-informed policymaking? Health Research Policy and Systems 7: S1.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paina L, Peters DH.. 2011. Understanding pathways for scaling up health services through the lens of complex adaptive systems. Health Policy and Planning 26: 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabatier PA. 1988. An advocacy coalition framework of policy change and the role of policy-oriented learning therein. Policy Sciences 21: 129–68. [Google Scholar]

- Sabatier PA, Jenkins-Smith HC.. 1999. The advocacy coalition framework, an assessment. In: Sabatier PA (ed). Theories of the Policy Process chap. 6, 117–166.

- Sewankambo N, Tumwine JK, Tomson G. et al. 2015. Enabling dynamic partnerships through joint degrees between low- and high-income countries for capacity development in global health research: experience from the Karolinska Institutet/Makerere University Partnership. PLoS Medicine 12: e1001784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ssengooba F, Atuyambe L, Kiwanuka SN. et al. 2011. Research translation to inform national health policies: learning from multiple perspectives in Uganda. BMC International Health and Human Rights 11: S13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland WJ, Bellingan L, Bellingham JR. et al. 2012. A collaboratively-derived science-policy research agenda. PLoS One 7: e31824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tetroe JM, Graham ID, Foy R. et al. 2008. Health research funding agencies' support and promotion of knowledge translation: an international study. The Milbank Quarterly 86: 125–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas JW, Grindle MS.. 1990. After decision: implementing policy reforms in developing countries. World Development 18: 1163–81. 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Van Kammen J, de Savigny D, Sewankambo N.. 2006. Using knowledge brokering to promote evidence-based policy-making: the need for support structures. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 84: 608–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward V, House A, Hamer S.. 2009. Knowledge brokering: the missing link in the evidence to action chain? Evidence and Policy 5: 267–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walt G, Shiffman J, Schneider H. et al. 2008. ‘Doing’ health policy analysis: methodological and conceptual reflections and challenges. Health Policy and Planning 23: 308–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weible CM, Sabatier PA, McQueen K.. 2009. Themes and variations: taking stock of the advocacy coalition framework. The Policy Studies Journal 37: 121–40. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson MG, Moat KA, Lavis JN.. 2013. The global stock of research evidence relevant for health system policy. Health Research Policy and Systems 11: 32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO, 2008. Everybody’s Business, World Health Report. Geneva: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- WHO, 2013. Research for Universal Health Coverage, World Health Report. Geneva: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Yin RK. 1999. Improving the quality of case studies in health services research. Health Services Research 34: 1209–24. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin RK. 2009. Case Study Research: Design and Methods, 4th edn Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]