Abstract

We have isolated a 590-bp full-length cDNA clone designated Dg93, an mRNA that is highly expressed in symbiotic root nodules of the actinorhizal host Datisca glomerata. Dg93 mRNA encodes a deduced polypeptide of 105 amino acids with significant identity (74%) to the soybean (Glycine max) early nodulin (ENOD) gene GmENOD93 (Kouchi and Hata, 1993). Dg93 mRNA is abundant in nodules at 4 weeks post inoculation, the earliest time assayed, and steady-state mRNA levels remain elevated 11 weeks after inoculation. Spatial patterns of Dg93 mRNA expression are complex, with transcript accumulation in the nodule lobe meristem, early infection zone, periderm, and cells of the vascular cylinder, but not in the surrounding uninfected cortical cells. Dg93 is encoded by a small gene family in D. glomerata. To our knowledge, this is the first report of a gene from an actinorhizal host that is expressed in the nodule meristem and that shares sequence homology with an early nodulin gene from a legume.

Organogenesis of symbiotic root nodules involves the induction of multiple developmental processes that are initiated by a host-endosymbiont interaction and that result in a functional exchange of nitrogen and carbon that supports both host and endosymbiont. Both legume and actinorhizal hosts share common aspects of nodule development, including the infection process and nitrogen assimilatory pathways (for review, see Pawlowski and Bisseling, 1996; Hirsch and LaRue, 1997; Pawlowski, 1997). Likewise, molecular components of nitrogen assimilation and oxygen partitioning, such as Gln synthetase, nitrogenase, and leghemoglobin, are synthesized in both legume and actinorhizal nodules.

Datisca glomerata nodules are modified lateral roots, indeterminate, generally multi-lobed, with a periderm four to eight cells thick (Benson and Silvester, 1993). Each nodule lobe contains an infected area, visible as a crescent covering about two-thirds of the nodule when viewed in transverse section, and a surrounding uninfected region. The nodule is traversed by a central vascular cylinder, which is enclosed by a multi-layered pericycle. Eventually, the nodule meristem grows out to form an ageotropic nodule root.

The expression of early nodulin (ENOD) genes has been well characterized in several legume species. Based on their biochemical attributes and expression patterns, they are postulated to have roles in cell structure (see Franssen et al., 1992; Küster et al., 1995; Greene et al., 1998), in the control of nodule ontogeny by the degradation of Nod factor (Goormachtig et al., 1998a), and in carbon metabolism (Coba de la Peña et al., 1997). Some ENODs are proposed to be involved in oxygen partitioning (van de Wiel et al., 1990), but the findings of Wycoff et al. (1998) suggest that ENOD2 is not a part of the oxygen exclusion system. The induction of ENOD40 (Fang and Hirsch, 1998), ENOD2 (Silver et al., 1996; Goormachtig et al., 1998b), ENOD12 (Bauer et al., 1996), carbonic anhydrase (Coba de la Peña et al., 1997), and other ENOD genes by Nod factor or cytokinin indicates a hierarchy of action in nodule organogenesis. In general, ENOD genes exhibit complex spatial and temporal expression patterns, indicating that they are required at various times and in various cell types throughout nodule development.

In actinorhizal hosts, genes associated with nodule morphogenesis have been primarily expressed in mature nodules (e.g. Pawlowski et al., 1993; Ribeiro et al., 1995; Gherbi et al., 1997; Franche et al., 1998; Jacobsen-Lyon et al., 1995). One Alnus gene of unknown function is specifically expressed in cells of the infected region and the pericycle (Pawlowski, 1997). There remains a paucity of information on genes expressed during the early stages of nodule development. We present evidence for the isolation and characterization of the first actinorhizal early nodulin.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Material

Datisca glomerata plants were grown in the greenhouse and inoculated with crushed, Frankia-infected nodules of Ceanothus griseus, as described previously (Liu and Berry, 1991). For RNA analyses, young leaves, developing fruits containing immature seeds, flowers (sepals, anthers, stamens, and styles), roots, and nodules at 4, 5, 7, and 11 weeks after inoculation were harvested into liquid nitrogen. For fixation, nodules were collected in water at 1 and 6 months post inoculation.

cDNA Isolation and RNA Analysis

Dg93 was originally identified as a chimeric nucleotide sequence adjoined to a full-length cDNA clone of Rubisco activase (P.A. Okubara and A.M. Berry, unpublished data). The chimeric clone had been obtained from a Lambda Zap II (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) cDNA library representing mRNAs of D. glomerata nodules harvested 4, 5, and 7 weeks after inoculation (P.A. Okubara and A.M. Berry, unpublished data). To obtain plasmids containing only Dg93 cDNA, 8 × 104 unamplified recombinant clones from the cDNA library were screened with a Dg93-specific probe obtained from the chimeric cDNA clone following digestion with EcoRI (Bethesda Research Laboratory, Gaithersburg, MD) and Bsp106I (Stratagene). One resulting Dg93 clone was selected for all subsequent work.

Analysis of RNA expression in northern blots was carried out essentially as described in Pawlowski et al. (1994). Dg93 cDNA was excised from the Bluescript phagemid vector and radiolabeled by incorporation of [α-32P]dCTP (Amersham, Arlington Heights, IL) using the Multiprime DNA Labeling System (Amersham) to specific activities of 1.8 to 3.7 × 104 Bq μg−1 (1–2 × 106 cpm ng−1). Radiolabel was quantified from freshly washed nylon membranes using a phosphor imager (Storm, Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, CA) and imaging plate (BAS III, Fuji, Tokyo), and analyzed with imaging software (Image QuanNT, version 4.00, Molecular Dynamics).

DNA Isolation and Southern-Blot Analysis

Total DNA was obtained from young leaves of D. glomerata as described in Ribeiro et al. (1995). DNA was transferred to Zeta Probe nylon membranes (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) following treatment with HindIII or EcoRI restriction enzymes (Sambrook et al., 1989). Hybridization of blots was carried out as recommended by the manufacturer, using the probes described below.

In Situ Hybridization

One- and 6-month-old nodules were fixed in 14.3% (w/v) paraformaldehyde, 0.25% (w/v) glutaraldehyde in phosphate buffer, rinsed in buffer, dehydrated, and stored in 80% (v/v) ethanol at −20°C. Fixed nodules were shipped on ice prior to dehydration in the tert-butyl alcohol series and Paraplast embedding medium (McKhann and Hirsch, 1993). Sections were cut at 10 μm and mounted with water onto Vector bond-treated slides (Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA). The in situ hybridization protocol of McKhann and Hirsch (1993) was carried out except that the slides were pretreated at 37°C with increased amounts of proteinase K (5 μg mL−1) and acetic anhydride (0.5%, w/v). Dg93 cDNA was used to generate antisense and sense riboprobes labeled with digoxigenin-11-UTP (Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis). Color development was carried out for 12 to 16 h. The slides were not counterstained. Photographs were taken with Ektachrome Tungsten 160 slide film (Eastman Kodak, Rochester, NY) on a microscope (Axiophot, Carl Zeiss, Thornwood, NY). The slides were scanned into a computer and processed with Photoshop software (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA).

Computerized Sequence Analyses

Nucleotide and deduced amino acid sequences of Dg93 were compared to GenBank database entries using BLASTN and BLASTX algorithms, respectively (Altschul et al., 1997). Amino acid sequence alignments were carried out with ClustalW 1.7 (http://dot.imgen.bcm.tmc.edu:9331/multi-align/multi-align.html) and the Shading Utility program of GeneDoc (http://www.cris.com/∼ketchup/genedoc.html, and refs. therein). Nucleotide and amino acid sequence identity values were obtained using Align (http://dot.imgen.bcm.tmc.edu:9331/seq-search/alignment.html). Protein folding was examined on the Baylor College of Medicine Protein Secondary Structure Prediction website (http://dot.imgen.bcm.tmc.edu:9331/pssprediction/pssp.html, and refs. therein). Protein motifs were analyzed using the Baylor College of Medicine PSITE and NNPREDICT programs (http://www.cmpharm.ucsf.edu/∼nomi/nnpredict, and refs. therein). Consensus signal sequences were analyzed using PSORT (http://psort.nibb.ac.jp, and refs. therein).

RESULTS

Molecular Characterization of Dg93

As a part of our interest in the molecular basis of organogenesis of actinorhizal nodules, we have isolated a highly expressed, nodule-specific cDNA (Dg93) from symbiotic root nodules of D. glomerata. Using a probe obtained from a chimeric Dg93-Rubisco activase clone, we screened 8 × 104 unamplified recombinant phage and identified about 50 clones hybridizing to the Dg93 probe. The retrieval frequency of one clone in 1.6 × 103 indicated that Dg93 was abundant in our cDNA library.

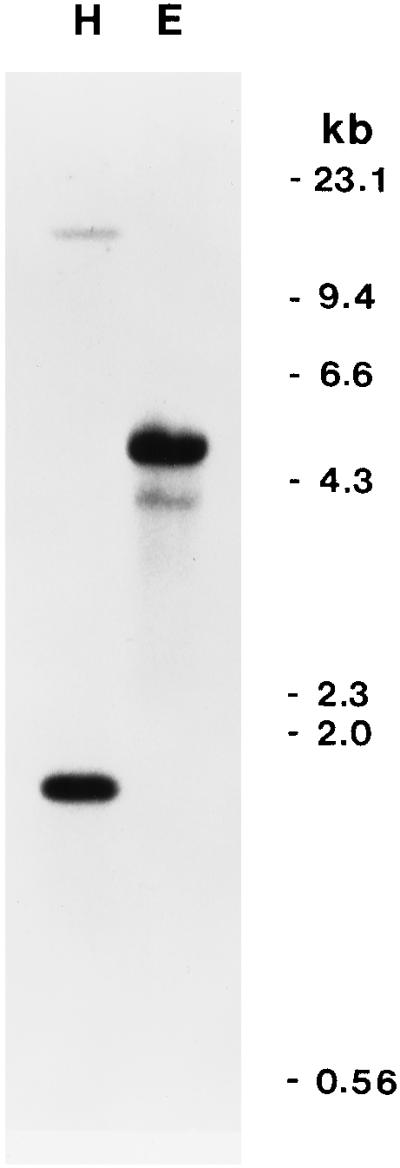

One strongly hybridizing HinDIII fragment of 1.65 kb and one strongly hybridizing EcoRIII fragment of 5.0 kb were detected in a Southern blot of total D. glomerata DNA hybridized to the Dg93 cDNA (Fig. 1). One weakly hybridizing HindIII fragment and one weakly hybridizing EcoRI fragment were also observed in the autoradiograph. The sequence of the Dg93 cDNA does not contain a HindIII or an EcoRI restriction site. Therefore, our data indicate the presence of one or two copies of Dg93 in the D. glomerata genome.

Figure 1.

Southern blot of total DNA of D. glomerata treated with HindIII (H) or EcoRI (E) and hybridized to radiolabeled Dg93 cDNA probe. Autoradiography was carried out at −80°C for 5 d.

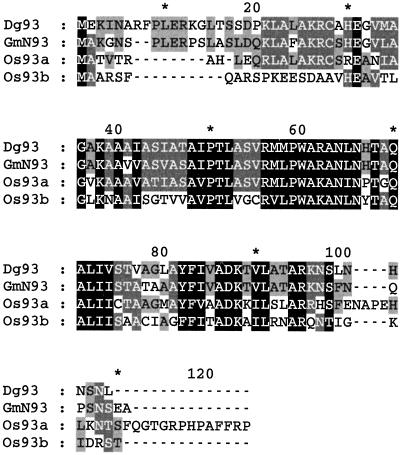

In database searches using the BLASTN and BLASTX algorithms (Altschul et al., 1997), Dg93 was highly similar (P[N] = 1.3 × 10−35 for amino acid sequences) to a soybean ENOD, GmENOD93 (Kouchi and Hata, 1993). A nucleotide sequence comparison yielded 83% identity. Deduced polypeptides of both genes were 105 amino acids in length and shared 74% identity (Fig. 2). Dg93 also showed 44% and 40% amino acid sequence identity to polypeptides encoded by two rice cDNA clones, OsENOD93a and OsENOD93b, respectively (Reddy et al., 1998). Twenty-two residues (21%) of the putative Dg93 polypeptide were Ala, rendering it particularly rich in this amino acid. Protein-folding algorithms predicted that the Dg93 polypeptide is comprised mainly of α-helical secondary structure, with putative sites for N-glycosylation, protein kinase phosphorylation, and myristoylation.

Figure 2.

Comparison of the deduced amino acid sequences of Dg93, GmENOD93 (GmN93; Kouchi and Hata, 1993), and two rice homologs (Os93a and Os93b; Reddy et al., 1998) obtained from analysis of a ClustalW alignment with the shading program of GeneDoc. The black-boxed portions indicate identical or conserved amino acids found in all four sequences; lighter shadings indicate conservation among three or fewer sequences.

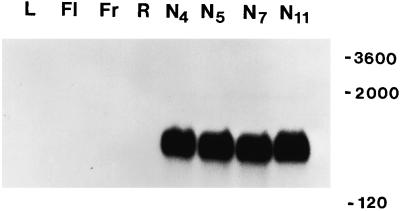

Dg93 mRNA was abundant in nodules at 4 to 11 weeks after Frankia inoculation, but transcripts were not detectable in leaves, flowers, developing fruits, or roots of D. glomerata (Fig. 3). Thus, Dg93 appears to be nodule specific. Quantitation of radiolabel on freshly washed nylon membranes indicated that the steady-state levels of mRNA in the nodule remained constant over the 7-week sampling period (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Expression of Dg93 mRNA in various organs of D. glomerata. Total RNA samples (5 μg per lane) from young leaves (L), flowers (Fl), developing fruits (Fr), roots (R), and nodules harvested 4 (N4), 5 (N5), 7 (N7), and 11 weeks (N11) after inoculation were hybridized to radiolabeled Dg93 cDNA in a northern blot. Autoradiography was conducted at 25°C for 21.5 h.

Spatial Patterns of Dg93 Transcript Expression

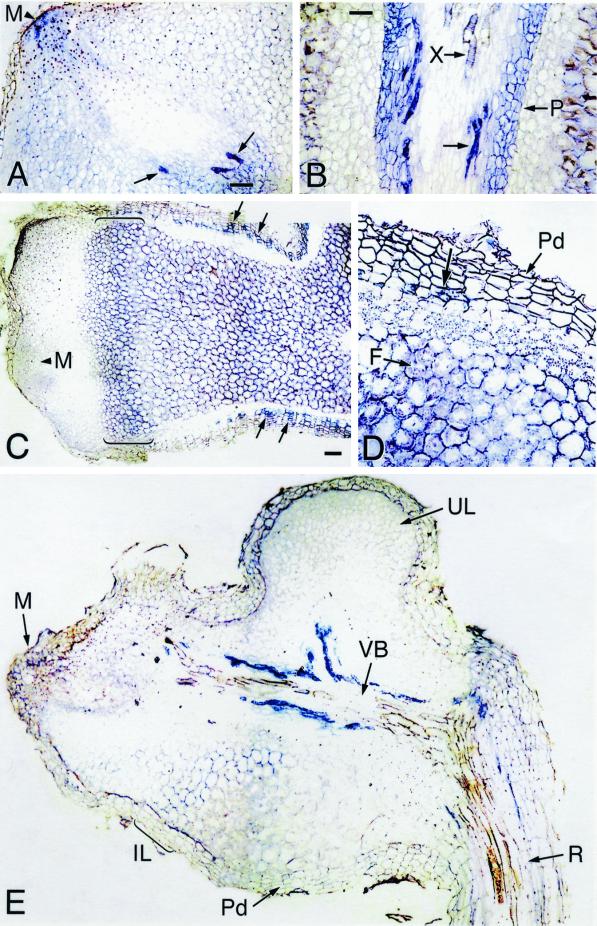

To localize Dg93 transcripts within the D. glomerata nodule, we examined nodules harvested 1 and 6 months after Frankia inoculation. The expression pattern of Dg93 message, indicated by the dark blue color of precipitated digoxigenin conjugate, was complex. At 1 and 6 months after inoculation, Dg93 transcripts were expressed in the nodule lobe meristem, closely associated with meristematic cells destined to form the vascular cylinder (Fig. 4, A, C, and E). Dg93 transcripts were also detected in cells within the phloem tissue, distal to the apical meristem (Fig. 4, A, B, and E). At 6 months post inoculation, a lower level of Dg93 expression was also observed in the multi-layered pericycle (Fig. 4B). Cytoplasm-containing cells of the periderm also accumulated Dg93 transcripts, whereas the uninfected, starch-filled cortical cells surrounding the infection zone were completely devoid of Dg93 message (Fig. 4, C and D).

Figure 4.

In situ localization of Dg93 transcripts in longitudinal sections of D. glomerata nodules harvested 6 months (A–D) and 1 month (E) after inoculation with Frankia. A, Dark blue color indicating Dg93 gene expression is present in the nodule apical meristem (M) and is associated with the vascular cylinder. Arrows indicate cells in the phloem that contain Dg93 transcripts. Bar = 20 μm. B, Enlargement of the infected-cell region distal to the apical meristem. Dg93 transcripts are present in the phloem tissue (arrow) and in the multi-layered pericycle (P). X, Xylem vessel. Bar = 20 μm. C, A mature lobe containing infected cells. Dg93 transcripts are found in the meristem (M), in the periderm (arrows), and in the infected central region of the nodule. Brackets indicate a region of the infection zone where Dg93 transcripts accumulate to a high level. The infected tissue appears banded due to varying levels of Dg93 gene expression. Bar = 40 μm. D, Enlargement of the distal (Legend continues on facing page.)part of the nodule. The Dg93 transcripts seen in the band of young infected cells in brackets in C is to the right of this micrograph. Transcripts are also seen in the inner cells (arrow) of the periderm (Pd) and in the host cells surrounding the Frankia (F). Magnification same as B. E, Off-median section in which Dg93 gene expression is most evident in the central vascular bundle (VB). Some blue color is apparent in the meristem (M) and in the early-infected region of the nodule lobe (IL), but not in mature infected cells, where the host cytoplasm containing Frankia surrounds a small central vacuole in a doughnut shape. The innermost cells of the periderm (Pd) are also labeled. Uninfected regions of the nodule lobe (UL) and parent root (R) cortex show no detectable Dg93 expression. Magnification same as C.

In the Frankia-infected zones of the nodule at 6 months post inoculation, we observed differential accumulation of blue color in bands across the infected region, as shown in Figure 4C. Dg93 transcripts accumulated to high levels in a band of cells proximal to the nodule meristem, some of which contained visible Frankia (Fig. 4, C and D). A region of less-intense blue can be seen below the first zone (Fig. 4, C and D). The peripheral, doughnut-shaped configuration of Frankia within cells of this second zone is typical of mature, vesicle-containing tissue in D. glomerata (Benson and Silvester, 1993; Okubara et al., 1999). Below this region, further into the mature-infected zone, digoxigenin staining increased in intensity again.

In nodules at 1 month post-inoculation, as shown in Figure 4E, Dg93 mRNA was detected in the nodule meristem (M) and in a band of early-infected cells (IL), but not in the mature, vesicle-containing tissue just basal to this zone. As in the 6-month post-inoculation nodules, blue color indicating the presence of Dg93 mRNA was especially prevalent in the phloem, and was also observed in the periderm (Pd). Very few transcripts were found in the cells of the pericycle at this stage. The uninfected region of this nodule lobe was devoid of Dg93 transcripts except in the innermost layer of the periderm.

Nodule sections incubated with the sense Dg93 transcript showed no detectable color (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

Dg93 has several characteristics in common with GmENOD93, a highly homologous gene from soybean (Kouchi and Hata, 1993). Both mRNAs are about 600 nt in length, produce a putative polypeptide of 105 amino acids and are coded by single-gene or small gene families. Like GmENOD93 (and the rice homologs), the deduced amino acid sequence of Dg93 is Ala rich, although its Ser content is not as high as its soybean counterpart. Both mRNAs are abundant in nodules but not detectable in other organs of the host plant, including leaves and roots. These shared features suggest that Dg93 is an actinorhizal homolog of GmENOD93.

The spatial expression pattern of Dg93 in D. glomerata nodules may be compared to that of GmENOD93 in soybean nodules. In the early stages of soybean nodule development, GmENOD93 is expressed in dividing cells or in the nodule meristem. In mature nodules, GmENOD93 is only expressed in infected cells (Kouchi and Hata, 1993). In D. glomerata, Dg93 expression is first observed in the nodule lobe meristem and in cells undergoing Frankia infection, then is detectable to a lesser degree in mature Frankia-containing cells. In contrast to GmENOD93, Dg93 transcripts accumulate to higher levels in the young infected cells, in cells of the vascular cylinder, and in cytoplasm-containing periderm cells. This pattern of expression more closely resembles that of ENOD2 in Sesbania rostrata nodules (Goormachtig et al., 1998b), and of ENOD40 in soybean nodules (Yang et al., 1993).

In soybean, GmENOD93 transcripts were detectable as early as 3 d following incubation with Bradyrhizobium, and mRNA levels were examined up to 17 d post inoculation. Our earliest assay point was approximately 4 weeks post inoculation, or 1 week after formation of visible nodules on D. glomerata roots. The presence of an early nodulin transcript in mature, 11-week-old D. glomerata nodules can be attributed in part to the indeterminate nature of these nodules, in which an active meristem is maintained, and a developmental gradient of infection is present over a period of months following initial infection by Frankia. Since Dg93 transcripts also accumulated in tissues of mature nodules, the term “early nodulin” does not entirely accurately describe this gene.

Computerized secondary protein structure analyses predict one major, Ala-rich α-helix of 28 amino acids (MKLALAKRCAHEGVMAGAKAAAIASIATAI), four phosphorylation sites, three N-myristoylation sites, and targeting to the endoplasmic reticulum membrane. Dg93 lacks an apparent N-terminal signal sequence and other peptide motifs of known function. The high Ala content of the deduced polypeptide is expected to confer hydrophobicity, a characteristic that might have a role in protein aggregation or membrane protection. The Alas are generally distributed throughout the Dg93 polypeptide, unlike the PASSA repeat motif found in Ser/Ala-rich structural proteins from lower eukaryotes (described by Goldman et al. [1994]). Ala richness is also a characteristic of some cold-regulated genes, including KIN1 (Kurkela and Franck, 1990) and cor6.6 (Gilmour et al., 1992) from Arabidopsis and Wcs19 (Chauvin et al., 1993) from wheat.

Until now, actinorhizal homologs of legume early nodulins have not been found, possibly due to differences in the biochemical nature of the host-microbe interface (Pawlowski, 1997). The actinorhizal nodule arises from cell divisions of the pericycle and, although the prenodule formed in many actinorhizal roots originates from cortical cells, these nodules are clearly modified roots (for review, see Berry and Sunell, 1990). The legume nodule originates in cortical tissues and does not bear obvious resemblance to lateral roots (for review, see Hirsch and LaRue, 1997). Differences in the developmental origins and cellular architecture of the two nodule types might account for the apparent lack of actinorhizal ENODs. For example, ENOD2 is expressed in the legume nodule parenchyma (van de Wiel et al., 1990; Goormachtig et al., 1998b) for which there is no cellular equivalent in the actinorhizal nodule. Alternatively, biological function might be based on overall protein structure or conformation rather than on specific amino acid sequences. For example, ENOD40 genes from soybean and alfalfa share 79% nucleotide sequence homology (Asad et al., 1994). At the amino acid level, however, the degree of homology between the putative homologs is significantly lower (39%). Likewise, the ENOD12 gene from Medicago truncatula shares 65% nucleotide sequence identity with ENOD12B from pea, yet the amino acid sequences are 50% identical. It is also possible that nucleotide sequence divergence among legume and actinorhizal functional homologs might reflect the significant evolutionary distance between the legume family and the various actinorhizal groups (Soltis et al., 1995), and might account for the lack of detection of homologs in hybridization experiments.

As in the case of the hemoglobin genes from Casuarina (Jacobsen-Lyon et al., 1995), the nodule-expressed Dg93 might be a member of a family of divergent genes. The presence of a weakly hybridizing fragment in our genomic Southern blot raises the possibility that a divergent family member is expressed in non-nodule tissues and is not detectable in our stringent northern blots. Alternatively, Dg93 might be expressed in non-symbiotic tissues of D. glomerata, but at levels below the threshold of detection in our northern blots.

ENOD-like mRNAs are expressed in organs and tissues of non-nodulating plants. The presence of OsENOD93a mRNA in dividing cultured rice cells suggests that some ENOD-like genes are involved in cell division or de-differentiation (Reddy et al., 1998). OsENOD93b mRNA was most abundant in rice roots, but was also detected at reduced levels in etiolated and green leaves. In legumes, ENOD12 is also expressed in the stem and flower (Govers et al., 1991). We noted that the Dg93 deduced polypeptide shares identity with small polypeptides encoded by mRNAs expressed in tomato ovaries (58% identity, accession no. AI487889), maize endosperm (50% identity, accession no. AI664823), tomato shoots (44% identity, accession no. AI491189), pepper leaves (44% identity, accession no. AA840637), and cotton fibers (44% identity, accession no. AW108647). Comparing the most conserved 77 amino acids, identity to Dg93 was as high as 73% for the maize polypeptide, and 55% to 58% for polypeptides from the other species. Reddy et al. (1998) postulate that early nodulin genes have a general role in the development of multiple organs of both nodulating and non-nodulating plants, and that these genes have been recruited for nodule organogenesis in the legumes. The expression of Dg93-like mRNAs in numerous organs of diverse plant species is consistent with this hypothesis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank David Gilchrist and members of the National Science Foundation Center for Engineering Plants for Resistance Against Pathogens (Davis, CA) for use of the facilities for cDNA cloning and sequence analysis; Dean Lavelle at the Plant Genetics Facility, University of California (Davis), for expert sequencing; Katharina Pawlowski for RNA preparations; and Donald D. Kasarda, U.S. Department of Agriculture-Agricultural Research Service (Albany, CA), for advice on protein structure analyses. We are especially grateful to Margaret Kowalczyk for Figure 4.

Footnotes

This work was supported by California Agricultural Experiment Station Project no. 6,258 to A.M.B. and by the National Science Foundation (grant no. 94–0–2271 to A.M.H.).

LITERATURE CITED

- Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schaffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman DJ. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asad S, Fang Y, Wycoff KL, Hirsch AM. Isolation and characterization of cDNA and genomic clones of MsENOD40: transcripts are detected in meristematic cells of alfalfa. Protoplasma. 1994;183:10–23. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer P, Ratet P, Crespi MD, Schultze M, Kondorosi A. Nod factors and cytokinins induce similar cortical cell division, amyloplast deposition and MsEnod12A expression patterns in alfalfa roots. Plant J. 1996;10:91–105. [Google Scholar]

- Benson DR, Silvester WB. Biology of Frankia strains, actinomycete symbionts of actinorhizal plants. Microbiol Rev. 1993;57:293–319. doi: 10.1128/mr.57.2.293-319.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry AM, Sunell LA. The infection process and nodule development. In: Schwintzer CR, Tjepkema JD, editors. The Biology of Frankia and Actinorhizal Plants. New York: Academic Press; 1990. pp. 61–81. [Google Scholar]

- Chauvin L-P, Houde M, Sarhan F. A leaf-specific gene stimulated by light during wheat acclimation to low temperature. Plant Mol Biol. 1993;23:255–265. doi: 10.1007/BF00029002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coba de la Peña T, Frugier F, McKhann HI, Bauer P, Brown S, Kondorosi A, Crespi M. A carbonic anhydrase gene is induced in the nodule primordium and its cell-specific expression is controlled by the presence of Rhizobium during development. Plant J. 1997;11:407–420. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1997.11030407.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang Y, Hirsch AM. Studying early nodulin gene ENOD40 expression and induction by nodulation factor and cytokinin in transgenic alfalfa. Plant Physiol. 1998;116:53–68. doi: 10.1104/pp.116.1.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franche C, Laplaze L, Duhoux E, Bogusz D. Actinorhizal symbioses: recent advances in plant molecular and genetic transformation studies. Crit Rev Plant Sci. 1998;17:1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Franssen HJ, Vijn I, Yang WC, Bisseling T. Developmental aspects of the Rhizobium-legume symbiosis. Plant Mol Biol. 1992;19:89–107. doi: 10.1007/BF00015608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gherbi H, Duhoux E, Franche C, Pawlowski K, Nassar A, Berry AM, Bogusz D. Cloning of a full-length symbiotic hemoglobin cDNA and in situ localization of the corresponding mRNA in Casuarina glauca root nodule. Physiol Plant. 1997;99:608–616. [Google Scholar]

- Gilmour SJ, Artus NN, Thomashow MF. cDNA sequence analysis and expression of two cold-regulated genes of Arabidopsis. Plant Mol Biol. 1992;18:13–21. doi: 10.1007/BF00018452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman GH, Vasseur V, Conteras R, Van Montagu M. Sequence analysis and expression studies of a gene encoding a novel Ser+Ala-rich protein in Trichoderma harzianum. Gene. 1994;144:113–117. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)90213-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goormachtig S, Lievens S, Van de Velde W, Van Montagu M, Holsters M. Srch13, a novel early nodulin from Sesbania rostrata, is related to acidic class III chitinases. Plant Cell. 1998a;10:905–915. doi: 10.1105/tpc.10.6.905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goormachtig S, Van Montagu M, Holsters M. The early nodulin gene ENOD2 shows different expression patterns during Sesbania rostrata stem nodule development. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 1998b;3:237–241. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.1997.10.3.316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Govers F, Harmsen H, Heidstra R, Michielsen P, Prins M, van Kammen A, Bisseling T. Characterization of the pea ENOD12B gene and expression analyses of the two ENOD12 genes in nodule, stem and flowers. Mol Gen Genet. 1991;228:160–166. doi: 10.1007/BF00282461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene EA, Erard M, Dedieu A, Barker DG. MtENOD16 and 20 are members of a family of phytocyanin-related early nodulins. Plant Mol Biol. 1998;36:775–783. doi: 10.1023/a:1005916821224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch AM, LaRue TA. Is the legume nodule a modified root or stem or an organ sui generis? Crit Rev Plant Sci. 1997;16:361–392. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen-Lyon K, Jensen EO, Jørgensen J-E, Marcker KA, Peacock JA, Dennis ES. Symbiotic and non-symbiotic hemoglobin genes of Casuarina glauca. Plant Cell. 1995;7:213–223. doi: 10.1105/tpc.7.2.213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouchi H, Hata S. Isolation and characterization of novel nodulin cDNAs representing genes expressed at early stages of soybean nodule development. Mol Gen Genet. 1993;238:106–119. doi: 10.1007/BF00279537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurkela S, Franck M. Cloning and characterization of a cold- and ABA-inducible Arabidopsis gene. Plant Mol Biol. 1990;15:137–144. doi: 10.1007/BF00017731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Küster H, Schröder G, Früling M, Pich U, Pieping M, Schubert I, Perlick AM, Pühler A. The nodule-specific VfENOD-GRP3 gene encoding a Gly-rich early nodulin is located on chromosome I of Vicia faba L. and is predominantly expressed in the interzone II-III of root nodules. Plant Mol Biol. 1995;28:405–421. doi: 10.1007/BF00020390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q, Berry AM. The infection process and nodule initiation in the Frankia-Ceanothus root nodule symbiosis. Protoplasma. 1991;163:82–92. [Google Scholar]

- McKhann HI, Hirsch AM. In situ localization of specific mRNAs in plant tissues. In: Thompson JE, Glick BR, editors. Methods in Plant Molecular Biology and Biotechnology. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 1993. pp. 173–205. [Google Scholar]

- Okubara PA, Pawlowski K, Murphy TM, Berry AM. Symbiotic root nodules of the actinorhizal plant Datisca glomerata express Rubisco activase mRNA. Plant Physiol. 1999;120:411–420. doi: 10.1104/pp.120.2.411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawlowski K. Nodule-specific gene expression. Physiol Plant. 1997;99:617–631. [Google Scholar]

- Pawlowski K, Bisseling T. Rhizobial and actinorhizal symbioses: what are the shared features? Plant Cell. 1996;8:1899–1913. doi: 10.1105/tpc.8.10.1899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawlowski K, Kunze R, de Vries S, Bisseling T. Isolation of total, poly(A) and polysomal RNA from plant tissues. In: Gelvin SB, Schilperoort RA, editors. Plant Molecular Biology Manual D5. Ed 2. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1994. pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Pawlowski K, Ribeiro A, Guan C-H, van Kammen AB, Akkermans A, Bisseling T. Differential gene expression in root nodules of Alnus glutinosa. In: Hegazi NA, Fayez M, Monib M, editors. Nitrogen Fixation with Non-Legumes. American University in Cairo Press, Cairo. 1993. pp. 185–190. [Google Scholar]

- Reddy PM, Kouchi H, Ladha JK. Isolation, analysis and expression of homologs of the soybean early nodulin gene GmENOD93 (GmN93) from rice. Biochim Biophys Acta Gene Struct Exp. 1998;1443:386–392. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4781(98)00232-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro A, Akkermanns ADL, van Kammen A, Bisseling T, Pawlowski K. A nodule-specific gene encoding a subtilisin-like protease is expressed in early stages of actinorhizal nodule development. Plant Cell. 1995;7:785–794. doi: 10.1105/tpc.7.6.785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. Ed 2. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Silver DL, Pinaev A, Chem R, de Bruijn FJ. Posttranscriptional regulation of the Sesbania rostrata early nodulin gene SrEnod2 by cytokinin. Plant Physiol. 1996;112:559–567. doi: 10.1104/pp.112.2.559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soltis DE, Soltis PS, Morgan DR, Swensen SM, Mullin BC, Dowd JM, Martin PG. Chloroplast gene sequence data suggest a single origin of the predisposition for symbiotic nitrogen fixation in angiosperms. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:2647–2651. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.7.2647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van de Wiel C, Scheres B, Franssen H, van Lierop M-J, van Lammeren A, van Kammen A, Bisseling T. The early nodulin transcript ENOD2 is located in the nodule parenchyma (inner cortex) of pea and soybean root nodules. EMBO J. 1990;9:1–7. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb08073.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wycoff KL, Hunt S, Gonzales MB, VandenBosch KA, Layzell DB, Hirsch AM. Effects of oxygen on nodule physiology and expression of nodulins in alfalfa. Plant Physiol. 1998;117:385–395. doi: 10.1104/pp.117.2.385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang W-C, Katinakis P, Hendriks P, Smolders A, de Vries F, Spee J, van Kammen A, Bisseling T, Franssen H. Characterization of GmENOD40, a gene showing novel patterns of cell-specific expression during soybean nodule development. Plant J. 1993;3:573–585. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1993.03040573.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]