Abstract

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is known as a progressive lung disease and the fourth leading cause of death worldwide. Despite valuable efforts, there is still no accurate diagnostic and prognostic tool for COPD. Hence, it seems that finding new biomarkers could contribute to provide better therapeutic platforms for COPD patients. Among various biomarkers, microRNAs (miRNAs) have emerged as new biomarkers for the prognosis and diagnosis of patients with COPD. It has been shown that deregulation of miRNAs targeting a variety of cellular and molecular pathways such as Notch, Wnt, hypoxia-inducible factor-1α, transforming growth factor, Kras, and Smad could be involved in COPD pathogenesis. Multiple lines of evidence have indicated that extracellular vesicles such as exosomes could carry a variety of cargos (i.e., mRNAs, miRNAs, and proteins) which transfer various cellular and molecular signals to recipient cells. Here, we summarized various miRNAs which could be applied as diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers in the treatment of patients with COPD. Moreover, we highlighted the role of extracellular vesicles containing miRNAs as diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers in COPD patients.

Keywords: Biomarker, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diagnosis, exosome, microRNA, therapy

INTRODUCTION

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a disease due to chronic inflammation of the airways. This disease is accompanied by the presence of chronic obstruction.[1] Multiple lines of evidence have indicated that a wide range of factors (i.e., genetical and environmental) are involved in the initiation and progression of COPD. Smoking is known as one of the main factors which could be associated with chronic inflammation of the airways.[1] Inflammation is an important factor which has critical role in the initiation and progression of COPD.[2] It has been shown that various immune cells and a variety of cellular and molecular pathways are involved in inflammation and play critical roles in COPD pathogenesis.[3,4] Among many cellular and molecular targets, microRNAs (miRNAs) have emerged to be involved in COPD pathogenesis.[5,6] Deregulation of miRNAs is associated with the initiation and progression of several diseases such as stroke, cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, cancer, and inflammatory diseases.[7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14] Many miRNAs including miR-223, miR-1274a, miR-101, and miR-144 exert their effects via inhibition/activation of a sequence of cellular and molecular pathways (i.e., Smad, transforming growth factor β [TGF-β], Kras, Notch, and Wnt) involved in COPD.[5,6] Hence, it seems that these molecules could be used as new diagnostic and therapeutic biomarkers for patients with COPD. Alterations of miRNA expression could occur due to various events such as mutations and inhibition/activation of various targets.[15,16,17] Exosomes are extracellular vesicles which could change the expression of miRNAs in recipient cells. These nanocarriers could transfer various signals via cargos such as messenger RNAs (mRNAs), miRNAs, and proteins to recipient cells.[18,19] It has been shown that several exosomal miRNAs such as miR-100, miR-21, and miR-181a could be used as diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers in COPD.[19,20,21] In the current review, we focus on various miRNAs that could be utilized as diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers for COPD patients. Moreover, we highlighted the role of exosomes containing various cargos, especially miRNAs as diagnostic and therapeutic biomarkers for patients with COPD.

MICRO-RNA AS DIAGNOSTIC AND THERAPEUTIC BIOMARKERS IN CHRONIC OBSTRUCTIVE PULMONARY DISEASE

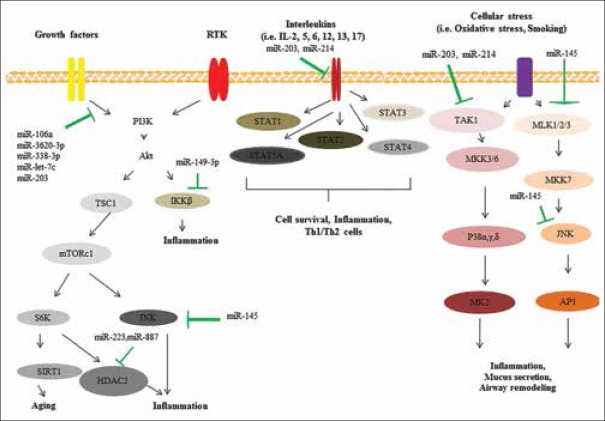

COPD is a chronic heterogeneous disease of the lungs which could be characterized by persistent and excessive inflammation, alveolar lesions, accelerated decrease in lung function, and airflow limitation.[22] Many factors such as inflammation and cell structure changes could be involved in the initiation and progression of COPD. miRNAs have also been suggested to be involved in the COPD pathogenesis [Figure 1]. These molecules are known as epigenetic regulators which exert their effects via targeting a variety of cellular and molecular pathways.[19,23,24,25,26,27,28,29] It has been shown that deregulation of miRNAs could be associated with the initiation and progression of several diseases such as cardiovascular diseases, stroke, diabetes, cancer, and COPD.[5,30,31,32,33,34,35] Multiple lines of evidence have revealed that up/down-regulation of various miRNAs (i.e., miR-21, miR-145, miR-181, miR-1, miR-144, and miR-101) could be related to COPD pathogenesis.[5,6] It has been showed that a variety of external factors (i.e., smoking and oxidative stress) and internal factors (i.e., deregulation of various growth factor ligands, interleukins [ILs], and receptor tyrosine kinase) could lead to deregulation of many cellular and molecular pathways and miRNA expression.[36,37,38] These events are associated with small and large alterations in molecular and cellular levels and could contribute to the progression of COPD.[36]

Figure 1.

Various cellular and molecular pathways involved in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

MiRNAs are involved in various signaling pathways such as TGF-β signaling pathway. Several studies have confirmed that TGF-β pathways play critical roles in COPD pathogenesis.[39,40] Baraldo et al. confirmed that downregulation of TGF-β type II receptor (TGF-βR2) is associated with the progression of COPD.[41] Their results indicated that the expression profile of TGF-β1 in bronchial glands was similar in the two groups of cases while there was a decreased in expression of TGF-βR2 in smokers with COPD than in smokers with normal lung function. Expression of TGF-βR2 was associated with the values of Reid's index which is known as a measure of gland size. These findings suggested that TGF-β signaling pathway has key roles in COPD pathogenesis.[41]

Ezzie et al. assessed gene expression profiles of many miRNAs and mRNAs in 26 patients with COPD.[5] They showed that miR-146a, miR-15b, miR-223, and miR-1274a were upregulated in COPD samples. Moreover, they showed that a variety of genes (e.g. BMP5 and BMP6, TGF-βR1 and TGF-βR2, and SMAD7) involved in TGF-β signaling pathway were downregulated in patients with COPD. Bioinformatics analysis indicated that various miRNAs could target these genes in COPD patients. For example, upregulation of miR-15b in a bronchial epithelial cell line could be associated with downregulation of SMAD7, SMURF2, and downstream decorin protein. These results proposed that many miRNAs are involved in TGF-β signaling pathway via targeting various genes and thus could contribute to the initiation and progression of COPD.[5]

O'Leary et al. indicated that miR-145 targets SMAD3 which is known as one of the important downstream signaling molecules in the TGF-β pathway and plays critical roles in the initiation and progression of COPD.[42] They showed that TGF-β could induce the expression of SMAD3 via increasing miR-145 in COPD patients. It has been shown that of miR-145 could be regulated by the MAP kinases, MEK-1/2, and p38 MAPK pathways. Upregulation of miR-145 in patients with COPD could inhibit the release of IL-6 and CXCL8. These findings suggest that miR-145 could regulate pro-inflammatory cytokine release from airway smooth muscle cells in COPD via targeting SMAD3.[42]

Kusko et al. assessed several genes and pathways involved in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) and COPD.[43] They showed that various members of the signaling pathways including hypoxia-inducible factor-1α, MDM2, and NFKBIB are involved in COPD and IPF pathogenesis. Moreover, they revealed that alternative splicing of p53/hypoxia pathway-related molecules NUMB and PDGFA occurred more frequently in IPF or COPD compared with the control group. RNA-seq analysis indicated that among many miRNAs, miR-96 acts as a major regulatory hub in the p53/hypoxia gene-expression network. The regulation of miR-96 in vitro recapitulates disease-related gene-expression network.[43] These findings suggest that a variety of signaling pathways that regulate miRNAs network are involved in COPD pathogenesis and miRNAs could be utilized as potential candidates for the diagnosis and prognosis of COPD.

Accumulating evidence indicates that smoking is one of the major risk factors for COPD which could be associated with the progression of COPD in various stages.[44] Numerous studies have confirmed that smoking can down/up-regulate many miRNAs and could thus affect COPD progression.

Du et al. assessed the expression levels of miR-181c in 34 patients with COPD (smoking cases) compared with healthy controls.[45] Their results indicated that miR-181c could be significantly downregulated in patients with COPD versus healthy controls who had never smoked. They also showed that upregulation of miR-181c could be associated with several effects such as reduction of the inflammatory response, neutrophil infiltration, reactive oxygen species generation, and inflammatory cytokines production. Downregulation of miR-181c could be associated with opposite effects. Moreover, they revealed that miR-181c exerts its effects via targeting CCN1. Downregulation of miR-181c could lead to an increase in CCN1 expression in the lung tissues of COPD patients compared with healthy controls. These findings suggested that miR-181c could be used as a therapeutic target for the treatment of patients with COPD.[45]

Multiple lines of evidence have indicated that DNA damage pathways are main players for aging disorders such as COPD.[46] This damage could be due to many factors such as oxidative stress and activates ataxia telangiectasia-mutated (ATM) kinase which has critical roles in the DNA damage response.[47] It has been shown that the increasing of DNA in the lung biopsies from smokers and COPD patients may accelerate lung aging and pathogenesis of COPD.[48,49]

Paschalaki et al. indicated that deregulation of miR-126 is associated with activation of ATM kinase.[50] They showed that the levels of miR-126 were downregulated in blood outgrowth endothelial cells from smokers and COPD patients compared with nonsmoker subjects. These results suggested that downregulation of miR-126 via targeting ATM could promote tissue aging and dysfunction in smoker and COPD subjects. Hence, this miRNA could be utilized as a novel therapeutic target in patients with COPD.[50]

Besides the role as therapeutic targets, miRNAs could be employed as prognostic and diagnostic biomarkers in various diseases such as COPD.[6] COPD is a multifactorial disease, and various efforts to find effective diagnostic and therapeutic platforms for treatment of patients with COPD have been made. It has been shown that the levels of various cytokines (i.e., IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, IL-17, IL-12p70, and IL-1β), cysteinyl-leukotrienes (LTs), LTB4, prostaglandin E(4), hydrogen peroxide (H(2)O(2)), and 8-isoprostane could be associated with COPD pathogenesis.[51] Despite many efforts, effective diagnostic biomarkers are still rare. Previous studies confirmed that miRNAs play critical roles in COPD pathogenesis. Hence, it seems that these molecules may be utilized as new prognostic and diagnostic biomarkers for monitoring patients with COPD.[6]

Soeda et al. investigated the expression levels of various circulating miRNAs in the plasma of 40 COPD patients.[52] They indicated that deregulation of many miRNAs could be associated with progression of COPD. Their results revealed that a variety of miRNAs including miR-29b, miR-483-5p, miR-152, miR-629, miR-26b, miR-101, miR-106b, miR-532-5p, and miR-133b were significantly downregulated in the plasma from COPD patients compared with control group. Moreover, they showed that there was negative association between the levels of miR-106b and duration of disease since the diagnosis in COPD ex-smokers and duration of smoking in COPD current smokers. These findings suggested that downregulation of miR-106b could reflect persistent and systemic alteration even after the discontinuation of smoking in patients with COPD. Hence, miRNAs may be utilized as diagnostic biomarkers for COPD patients.[52]

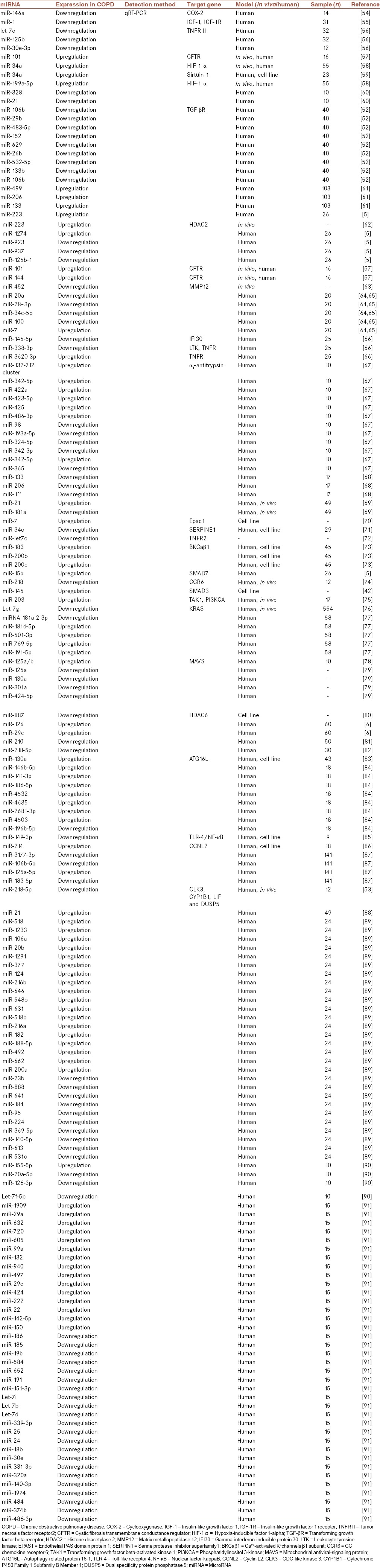

Kara et al. assessed the expression levels of several miRNAs including miR-16, miR-17, miR-29c, miR-92, miR-125, miR-126, miR-146, miR-155, miR-181, and miR-122 using real-time polymerase chain reaction in 60 patients with COPD.[6] Their results indicated that miR-29c and miR-126 were upregulated in COPD patients Stage III compared with healthy controls. These findings propose that these miRNAs may be utilized as diagnostic biomarkers for patients with COPD.[6] Table 1 lists various miRNAs involved in COPD pathogenesis which could be used as diagnostic and therapeutic biomarkers for the treatment of patients with COPD.

Table 1.

Several microRNAs involved in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease pathogenesis

MiR-218-5p is another important miRNA which has a main role in COPD pathogenesis and it seems that it could be used as an effective candidate for the diagnosis and monitoring of patients with COPD.[53] Conickx et al. indicated that various miRNAs such as miR-218-5p were deregulated in COPD patients.[53] They showed that the expression of miR-218-5p could be decreased in smokers without airflow limitation and in COPD patients compared with never-smokers. These results suggest that miR-218-5p has a protective role in cigarette smoke (CS)-induced inflammation and COPD patients and could be used as diagnostic and therapeutic biomarker for the detection and monitoring of patients with COPD.[53]

EXOSOME AND CHRONIC OBSTRUCTIVE PULMONARY DISEASE

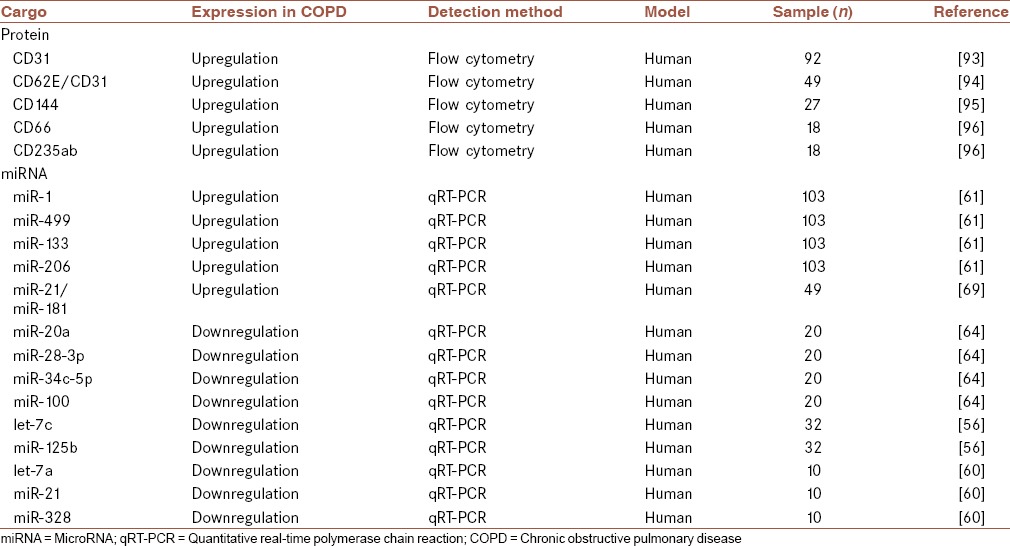

Many cells could change their behavior via receiving a variety of cellular and molecular signals. Extracellular vesicles (i.e., exosomes, apoptotic bodies, and microvesicles) are able to carry several signals to recipient cells.[12,92] Exosomes are known as one of the important nanovehicles which have critical roles in various physiological events. These vesicles could carry many cargos such as DNAs, mRNAs, miRNAs, and proteins.[18,19] Accumulating evidence has indicated that these extracellular vesicles could be employed as diagnostic and therapeutic biomarkers in the treatment of various diseases such as cancer and COPD [Table 2].[19,20,21]

Table 2.

Several cargos which carried by different microparticles such as exosomes

Several studies have indicated that extracellular vesicles such as exosomes are able to carry various cargos. Among several cargos, miRNAs are important and can transfer various cellular and molecular signals to recipient cells.[97] Hence, exosomal miRNAs could be used as new tools for diagnosis and treatment of various diseases such as COPD.

Fujita et al. investigated the effect of exosomal miRNAs in the suppression of autophagy in COPD patients.[98] It has been shown that CS exposure could lead to emphysema, increasing of myofibroblast, and airway remodeling, which all contribute to COPD progression. They showed that CS could induce upregulation of exosomal miR-210 in bronchial epithelial cells. Exosomal miR-210 could induce myofibroblast differentiation in lung fibroblasts (LFs). Exosomal miR-210 could directly control autophagy processes via affecting ATG7. The exosomal miR-210 expression is associated with downregulation of ATG7 in LFs. They reported decreased autophagy in LFs from COPD patients, and also, the silencing of ATG7 in LFs could lead to myofibroblast differentiation. These results indicated that CS exposure induces the modification of exosome components and exosomal miR-210 acts as a paracrine autophagy regulator of myofibroblast differentiation. This molecule could be employed as a therapeutic biomarker for patients with COPD.[97]

Skeletal muscle weakness is an important systemic complication of COPD which could affect exercise capacity and mortality. Burke et al. assessed the role of exosomal miRNAs in COPD patients who had skeletal muscle weakness.[98] They isolated exosomal miRNAs from serum and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) of four patients with COPD. Their results indicated that one exosomal miRNA was upregulated in serum of COPD patients and four exosomal miRNAs were downregulated in BALF of patients with COPD. In silico analysis indicated that these miRNAs could exert their effects via targeting many genes including S6K involved in the mTORC1 signaling pathway which serves as a key regulator of skeletal muscle wasting. These results indicated that exosomal miRNAs play critical roles in skeletal muscle wasting in patients with COPD and could be utilized as diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers for the detection, treatment, and monitoring of patients with this disease.[98]

Exosomal proteins (i.e., CD31, C-reactive protein [CRP], soluble tumor necrosis factor receptor 1 [sTNFR1], CD114, and CD66) are other types of biomarkers which could be employed for diagnosis and monitoring of COPD patients [Table 2].[99] Recently, Tan et al. assessed the expression levels of exosomes in plasma of patients with acute exacerbations of COPD (AECOPD) (n = 20), stable COPD (sCOPD; n = 20), and nonsmoking healthy group (n = 20).[99] Their results revealed that plasma levels of exosomes in AECOPD and sCOPD were significantly increased compared with healthy controls. Moreover, they showed that expression levels of exosomes were associated with plasma levels of CRP, sTNFR1, and IL-6. These findings suggested that exosomes could be anticipated in various pathogenic events involved in AECOPD and sCOPD. Hence, it seems that exosomes and their cargo could be utilized as diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers for the treatment of patients with COPD.[99]

It has been shown that persistence of inflammation is one of the important characteristics of COPD.[100] Exosomes could be involved in these events via targeting various cellular and molecular pathways involved in inflammation.[101] Multiple lines of evidence have revealed that several factors such as smoking, acceleration of epithelial cell senescence, airway epithelial cell injury, destruction of pulmonary capillary vasculature, and airway remodeling are associated with COPD pathogenesis.[102] Among various factors, airway epithelial cell injury is known as an important player in COPD pathogenesis. Several studies have indicated that injured lung epithelial cells could be an important source for inflammatory mediators such as granulocyte-macrophage-colony-stimulating factor, IL-1β, tumor necrosis factor-α, TGF-β and CXCL-8.[102] These mediators could exert their autocrine and paracrine effects on several cells. For example, TGF-β could stimulate remodeling of airway cells via modulation and induction of myofibroblast differentiation which is known as one of the main causes of fibrosis development during airway remodeling.[102] It has been revealed that the expression levels of TGF-β in the small airway epithelium of patients with COPD could be associated with the severity of airway obstruction.[103] Li et al. indicated that paracrine activity of various mediators is mediated by various exosomes released from human macrophages.[104] Hence, it seems that chronic exposure to CS could lead to epithelial cell death and lung tissue loss via targeting various exosomes containing mediators.[104]

Another study indicated that prolonged exposure to CS could induce the release of CCN1-enriched exosomes from lung epithelial cells. It has been indicated that CCN1 has critical roles in tissue remodeling and repair process as an extracellular matrix protein.[105] This protein could improve release of CXCL-8 from cells via targeting a variety of cellular and molecular signaling pathways such as Wnt signaling pathway.[106] These findings suggested that exosomes containing CCN1 could be associated with the paracrine stimulation of CXCL-8 in the lung mesenchyme or parenchyma and the subsequent recruitment of inflammatory cells.[105,107,108] These physiological events could lead to lung tissue fibrosis.[105,107,108] Letsiou et al. revealed that CS could increase the numbers of circulating lung epithelial cell-derived exosomes.[109] It has also been shown that the degree of lung endothelial injury in patients with COPD could be used as a diagnostic biomarker.[109] These studies suggested that various exosomes could be employed as diagnostic and therapeutic biomarkers in patients with COPD.[109,110]

CONCLUSION

COPD is known as a multifactorial disease, in which many factors such as smoking play critical roles. These factors could exert their effect via targeting vital pathways involved in inflammation. Among many molecules and pathways involved in COPD pathogenesis, miRNAs and exosomes have emerged as important players. It has been indicated that modulation of miRNAs via targeting various cellular and molecular pathways involved in COPD could contribute to the initiation and progression of COPD. The recognition of new markers that related with prognosis, diagnosis, therapy, and response to therapy may help improve and monitor of disease progression in COPD-afflicted patients. Among of various markers, miRNAs and exosomes have been emerged as new tools for using as diagnostic and therapeutic biomarkers in the treatment of COPD.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Szymczak I, Wieczfinska J, Pawliczak R. Molecular background of miRNA role in asthma and COPD: An updated insight. Biomed Res Int. 2016;2016:7802521. doi: 10.1155/2016/7802521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee SW, Lien HC, Chang CS, Yeh HZ, Lee TY, Tung CF, et al. The impact of acid-suppressing drugs to the patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A nationwide, population-based, cohort study. J Res Med Sci. 2015;20:263–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li Y, Lu Y, Zhao Z, Wang J, Li J, Wang W, et al. Relationships of MMP-9 and TIMP-1 proteins with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease risk: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Res Med Sci. 2016;21:12. doi: 10.4103/1735-1995.178737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Amra B, Borougeni VB, Golshan M, Soltaninejad F. Pulmonary function tests and impulse oscillometry in severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients' offspring. J Res Med Sci. 2015;20:697–700. doi: 10.4103/1735-1995.166229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ezzie ME, Crawford M, Cho JH, Orellana R, Zhang S, Gelinas R, et al. Gene expression networks in COPD: MicroRNA and mRNA regulation. Thorax. 2012;67:122–31. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2011-200089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kara M, Kirkil G, Kalemci S. Differential expression of microRNAs in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Adv Clin Exp Med. 2016;25:21–6. doi: 10.17219/acem/28343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mashreghi M, Azarpara H, Bazaz MR, Jafari A, Masoudifar A, Mirzaei H, et al. Angiogenesis biomarkers and their targeting ligands as potential targets for tumor angiogenesis. J Cell Physiol. 2018;233:2949–65. doi: 10.1002/jcp.26049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hoseini Z, Sepahvand F, Rashidi B, Sahebkar A, Masoudifar A, Mirzaei H, et al. NLRP3 inflammasome: Its regulation and involvement in atherosclerosis. J Cell Physiol. 2018;233:2116–32. doi: 10.1002/jcp.25930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rashidi B, Malekzadeh M, Goodarzi M, Masoudifar A, Mirzaei H. Green tea and its anti-angiogenesis effects. Biomed Pharmacother. 2017;89:949–56. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2017.01.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gholamin S, Mirzaei H, Razavi SM, Hassanian SM, Saadatpour L, Masoudifar A, et al. GD2-targeted immunotherapy and potential value of circulating microRNAs in neuroblastoma. J Cell Physiol. 2018;233:866–79. doi: 10.1002/jcp.25793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moridikia A, Mirzaei H, Sahebkar A, Salimian J. MicroRNAs: Potential candidates for diagnosis and treatment of colorectal cancer. J Cell Physiol. 2018;233:901–13. doi: 10.1002/jcp.25801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Banikazemi Z, Haji HA, Mohammadi M, Taheripak G, Iranifar E, Poursadeghiyan M, et al. Diet and cancer prevention: Dietary compounds, dietary microRNAs, and dietary exosomes. J Cell Biochem. 2018;119:185–96. doi: 10.1002/jcb.26244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mirzaei H, Ferns GA, Avan A, Mobarhan MG. Cytokines and microRNA in coronary artery disease. Adv Clin Chem. 2017;82:47–70. doi: 10.1016/bs.acc.2017.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Simonian M, Mosallayi M, Mirzaei H. Circulating miR-21 as novel biomarker in gastric cancer: Diagnostic and prognostic biomarker. J Cancer Res Ther. 2017 doi: 10.4103/0973-1482.175428. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Salarinia R, Sahebkar A, Peyvandi M, Mirzaei HR, Jaafari MR, Riahi MM, et al. Epi-drugs and epi-miRs: Moving beyond current cancer therapies. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2016;16:773–88. doi: 10.2174/1568009616666151207110143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mirzaei HR, Sahebkar A, Mohammadi M, Yari R, Salehi H, Jafari MH, et al. Circulating microRNAs in hepatocellular carcinoma: Potential diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers. Curr Pharm Des. 2016;22:5257–69. doi: 10.2174/1381612822666160303110838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gholamin S, Pasdar A, Khorrami MS, Mirzaei H, Mirzaei HR, Salehi R, et al. The potential for circulating microRNAs in the diagnosis of myocardial infarction: A novel approach to disease diagnosis and treatment. Curr Pharm Des. 2016;22:397–403. doi: 10.2174/1381612822666151112151924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mirzaei H, Sahebkar A, Jaafari MR, Goodarzi M, Mirzaei HR. Diagnostic and therapeutic potential of exosomes in cancer: The beginning of a new tale? J Cell Physiol. 2017;232:3251–60. doi: 10.1002/jcp.25739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saadatpour L, Fadaee E, Fadaei S, Nassiri Mansour R, Mohammadi M, Mousavi SM, et al. Glioblastoma: Exosome and microRNA as novel diagnosis biomarkers. Cancer Gene Ther. 2016;23:415–8. doi: 10.1038/cgt.2016.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kadota T, Fujita Y, Yoshioka Y, Araya J, Kuwano K, Ochiya T, et al. Extracellular vesicles in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17:E1801. doi: 10.3390/ijms17111801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hough KP, Chanda D, Duncan SR, Thannickal VJ, Deshane JS. Exosomes in immunoregulation of chronic lung diseases. Allergy. 2017;72:534–44. doi: 10.1111/all.13086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Decramer M, Janssens W, Miravitlles M. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Lancet. 2012;379:1341–51. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60968-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Khanmohammadi R, Mir F, Baniebrahimi G, Mirzaei H. Oral tumors in children: Diagnosis and management. J Cell Biochem. 2017 doi: 10.1002/jcb.26316. doi: 10.1002/jcb.26316. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Masoudi MS, Mehrabian E, Mirzaei H. MiR-21: A key player in glioblastoma pathogenesis. J Cell Biochem. 2018;119:1285–1290. doi: 10.1002/jcb.26300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Golabchi K, Soleimani-Jelodar R, Aghadoost N, Momeni F, Moridikia A, Nahand JS, et al. MicroRNAs in retinoblastoma: Potential diagnostic and therapeutic biomarkers. J Cell Physiol. 2018;233:3016–23. doi: 10.1002/jcp.26070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Keshavarzi M, Sorayayi S, Jafar Rezaei M, Mohammadi M, Ghaderi A, Rostamzadeh A, et al. MicroRNAs-based imaging techniques in cancer diagnosis and therapy. J Cell Biochem. 2017;118:4121–8. doi: 10.1002/jcb.26012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mirzaei H, Khataminfar S, Mohammadparast S, Sales SS, Maftouh M, Mohammadi M, et al. Circulating microRNAs as potential diagnostic biomarkers and therapeutic targets in gastric cancer: Current status and future perspectives. Curr Med Chem. 2016;23:4135–50. doi: 10.2174/0929867323666160818093854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mohammadi M, Goodarzi M, Jaafari MR, Mirzaei HR, Mirzaei H. Circulating microRNA: A new candidate for diagnostic biomarker in neuroblastoma. Cancer Gene Ther. 2016;23:371–2. doi: 10.1038/cgt.2016.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fathullahzadeh S, Mirzaei H, Honardoost MA, Sahebkar A, Salehi M. Circulating microRNA-192 as a diagnostic biomarker in human chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Cancer Gene Ther. 2016;23:327–32. doi: 10.1038/cgt.2016.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mirzaei H, Masoudifar A, Sahebkar A, Zare N, Sadri Nahand J, Rashidi B, et al. MicroRNA: A novel target of curcumin in cancer therapy. J Cell Physiol. 2018;233:3004–15. doi: 10.1002/jcp.26055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mirzaei H. Stroke in women: Risk factors and clinical biomarkers. J Cell Biochem. 2017;118:4191–202. doi: 10.1002/jcb.26130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rabieian R, Boshtam M, Zareei M, Kouhpayeh S, Masoudifar A, Mirzaei H, et al. Plasminogen activator inhibitor type-1 as a regulator of fibrosis. J Cell Biochem. 2018;119:17–27. doi: 10.1002/jcb.26146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Keshavarzi M, Darijani M, Momeni F, Moradi P, Ebrahimnejad H, Masoudifar A, et al. Molecular imaging and oral cancer diagnosis and therapy. J Cell Biochem. 2017;118:3055–60. doi: 10.1002/jcb.26042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mirzaei H, Momeni F, Saadatpour L, Sahebkar A, Goodarzi M, Masoudifar A, et al. MicroRNA: Relevance to stroke diagnosis, prognosis, and therapy. J Cell Physiol. 2018;233:856–65. doi: 10.1002/jcp.25787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rashidi B, Hoseini Z, Sahebkar A, Mirzaei H. Anti-atherosclerotic effects of Vitamins D and E in suppression of atherogenesis. J Cell Physiol. 2017;232:2968–76. doi: 10.1002/jcp.25738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Barnes PJ. Kinases as novel therapeutic targets in asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Pharmacol Rev. 2016;68:788–815. doi: 10.1124/pr.116.012518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Osei ET, Florez-Sampedro L, Timens W, Postma DS, Heijink IH, Brandsma CA, et al. Unravelling the complexity of COPD by microRNAs: It's a small world after all. Eur Respir J. 2015;46:807–18. doi: 10.1183/13993003.02139-2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sato T, Baskoro H, Rennard SI, Seyama K, Takahashi K. MicroRNAs as therapeutic targets in lung disease: Prospects and challenges. Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis. 2015;3:382–8. doi: 10.15326/jcopdf.3.1.2015.0160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.de Boer WI, van Schadewijk A, Sont JK, Sharma HS, Stolk J, Hiemstra PS, et al. Transforming growth factor beta1 and recruitment of macrophages and mast cells in airways in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;158:1951–7. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.158.6.9803053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Takizawa H, Tanaka M, Takami K, Ohtoshi T, Ito K, Satoh M, et al. Increased expression of transforming growth factor-beta1 in small airway epithelium from tobacco smokers and patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163:1476–83. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.163.6.9908135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Baraldo S, Bazzan E, Turato G, Calabrese F, Beghé B, Papi A, et al. Decreased expression of TGF-beta type II receptor in bronchial glands of smokers with COPD. Thorax. 2005;60:998–1002. doi: 10.1136/thx.2005.046292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.O'Leary L, Sevinç K, Papazoglou IM, Tildy B, Detillieux K, Halayko AJ, et al. Airway smooth muscle inflammation is regulated by microRNA-145 in COPD. FEBS Lett. 2016;590:1324–34. doi: 10.1002/1873-3468.12168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kusko RL, Brothers JF 2nd, Tedrow J, Pandit K, Huleihel L, Perdomo C, et al. Integrated genomics reveals convergent transcriptomic networks underlying chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;194:948–60. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201510-2026OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Laniado-Laborín R. Smoking and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Parallel epidemics of the 21 century. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2009;6:209–24. doi: 10.3390/ijerph6010209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Du Y, Ding Y, Chen X, Mei Z, Ding H, Wu Y, et al. MicroRNA-181c inhibits cigarette smoke-induced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease by regulating CCN1 expression. Respir Res. 2017;18:155. doi: 10.1186/s12931-017-0639-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Aoshiba K, Zhou F, Tsuji T, Nagai A. DNA damage as a molecular link in the pathogenesis of COPD in smokers. Eur Respir J. 2012;39:1368–76. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00050211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gorgoulis VG, Vassiliou LV, Karakaidos P, Zacharatos P, Kotsinas A, Liloglou T, et al. Activation of the DNA damage checkpoint and genomic instability in human precancerous lesions. Nature. 2005;434:907–13. doi: 10.1038/nature03485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Caramori G, Adcock IM, Casolari P, Ito K, Jazrawi E, Tsaprouni L, et al. Unbalanced oxidant-induced DNA damage and repair in COPD: A link towards lung cancer. Thorax. 2011;66:521–7. doi: 10.1136/thx.2010.156448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tsuji T, Aoshiba K, Nagai A. Alveolar cell senescence exacerbates pulmonary inflammation in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respiration. 2010;80:59–70. doi: 10.1159/000268287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Paschalaki KE, Zampetaki A, Baker JR, Birrell MA, Starke RD, Belvisi MG, et al. Downregulation of microRNA-126 augments DNA damage response in cigarette smokers and COPD patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017 doi: 10.1164/rccm.201706-1304LE. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201706-1304LE. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Koutsokera A, Kostikas K, Nicod LP, Fitting JW. Pulmonary biomarkers in COPD exacerbations: A systematic review. Respir Res. 2013;14:111. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-14-111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Soeda S, Ohyashiki JH, Ohtsuki K, Umezu T, Setoguchi Y, Ohyashiki K, et al. Clinical relevance of plasma miR-106b levels in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int J Mol Med. 2013;31:533–9. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2013.1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Conickx G, Mestdagh P, Avila Cobos F, Verhamme FM, Maes T, Vanaudenaerde BM, et al. MicroRNA profiling reveals a role for microRNA-218-5p in the pathogenesis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;195:43–56. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201506-1182OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sato T, Liu X, Nelson A, Nakanishi M, Kanaji N, Wang X, et al. Reduced miR-146a increases prostaglandin E2in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease fibroblasts. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182:1020–9. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201001-0055OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lewis A, Riddoch-Contreras J, Natanek SA, Donaldson A, Man WD, Moxham J, et al. Downregulation of the serum response factor/miR-1 axis in the quadriceps of patients with COPD. Thorax. 2012;67:26–34. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2011-200309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Van Pottelberge GR, Mestdagh P, Bracke KR, Thas O, van Durme YM, Joos GF, et al. MicroRNA expression in induced sputum of smokers and patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:898–906. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201002-0304OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hassan F, Nuovo GJ, Crawford M, Boyaka PN, Kirkby S, Nana-Sinkam SP, et al. MiR-101 and miR-144 regulate the expression of the CFTR chloride channel in the lung. PLoS One. 2012;7:e50837. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0050837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mizuno S, Bogaard HJ, Gomez-Arroyo J, Alhussaini A, Kraskauskas D, Cool CD, et al. MicroRNA-199a-5p is associated with hypoxia-inducible factor-1α expression in lungs from patients with COPD. Chest. 2012;142:663–72. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-2746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Baker J, Colley T, Ito K, Barnes P. The key role of microRNA-34a in the reduction of sirtuin-1 in COPD. Eur Respir Soc. 2016;48:OA4977. DOI: 10.1183/13993003.congress-2016.OA4977. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pinkerton M, Chinchilli V, Banta E, Craig T, August A, Bascom R, et al. Differential expression of microRNAs in exhaled breath condensates of patients with asthma, patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and healthy adults. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;132:217–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Donaldson A, Natanek SA, Lewis A, Man WD, Hopkinson NS, Polkey MI, et al. Increased skeletal muscle-specific microRNA in the blood of patients with COPD. Thorax. 2013;68:1140–9. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2012-203129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Leuenberger C, Schuoler C, Bye H, Mignan C, Rechsteiner T, Hillinger S, et al. microRNA-223 suppresses histone deacetylase 2 in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Mol Med (Berl) 2016;94:725–34. doi: 10.1007/s00109-016-1388-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Graff JW, Powers LS, Dickson AM, Kim J, Reisetter AC, Hassan IH, et al. Cigarette smoking decreases global microRNA expression in human alveolar macrophages. PLoS One. 2012;7:e44066. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0044066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Akbas F, Coskunpinar E, Aynaci E, Oltulu YM, Yildiz P. Analysis of serum micro-RNAs as potential biomarker in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Exp Lung Res. 2012;38:286–94. doi: 10.3109/01902148.2012.689088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mi S, Zhang J, Zhang W, Huang RS. Circulating microRNAs as biomarkers for inflammatory diseases. Microrna. 2013;2:63–71. doi: 10.2174/2211536611302010007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wang M, Huang Y, Liang Z, Liu D, Lu Y, Dai Y, et al. Plasma miRNAs might be promising biomarkers of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Clin Respir J. 2016;10:104–11. doi: 10.1111/crj.12194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Molina-Pinelo S, Pastor MD, Suarez R, Romero-Romero B, González De la Peña M, Salinas A, et al. MicroRNA clusters: Dysregulation in lung adenocarcinoma and COPD. Eur Respir J. 2014;43:1740–9. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00091513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Puig-Vilanova E, Aguiló R, Rodríguez-Fuster A, Martínez-Llorens J, Gea J, Barreiro E, et al. Epigenetic mechanisms in respiratory muscle dysfunction of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. PLoS One. 2014;9:e111514. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0111514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Xie L, Wu M, Lin H, Liu C, Yang H, Zhan J, et al. An increased ratio of serum miR-21 to miR-181a levels is associated with the early pathogenic process of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in asymptomatic heavy smokers. Mol Biosyst. 2014;10:1072–81. doi: 10.1039/c3mb70564a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Oldenburger A, van Basten B, Kooistra W, Meurs H, Maarsingh H, Krenning G, et al. Interaction between epac1 and miRNA-7 in airway smooth muscle cells. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2014;387:795–7. doi: 10.1007/s00210-014-1015-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Savarimuthu Francis SM, Davidson MR, Tan ME, Wright CM, Clarke BE, Duhig EE, et al. MicroRNA-34c is associated with emphysema severity and modulates SERPINE1 expression. BMC Genomics. 2014;15:88. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-15-88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Shin JI, Brusselle GG. Mechanistic links between COPD and lung cancer: A role of microRNA let-7? Nat Rev Cancer. 2014;14:70. doi: 10.1038/nrc3477-c1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Cao Z, Zhang N, Lou T, Jin Y, Wu Y, Ye Z, et al. MicroRNA-183 down-regulates the expression of BKCaβ1 protein that is related to the severity of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Hippokratia. 2014;18:328–32. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Conickx G, Mestdagh P, Avila Cobos F, Verhamme FM, Maes T, Vanaudenaerde BM. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;195:43–56. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201506-1182OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Shi L, Xin Q, Chai R, Liu L, Ma Z. Ectopic expressed miR-203 contributes to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease via targeting TAK1 and PIK3CA. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8:10662–70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hu H, Zhang L, Teng G, Wu Y, Chen Y. A variant in 3'-untranslated region of KRAS compromises its interaction with hsa-let-7g and contributes to the development of lung cancer in patients with COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2015;10:1641–9. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S83596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kim WJ, Hong S, Hong Y, Lee SD, Oh Y. European Respiratory Journal. 2015;46:OA1460. DOI: 10.1183/13993003.congress-2015.OA1460. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hsu AC, Dua K, Starkey MR, Haw TJ, Nair PM, Nichol K, et al. MicroRNA-125a and -b inhibit A20 and MAVS to promote inflammation and impair antiviral response in COPD. JCI Insight. 2017;2:e90443. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.90443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hertig D, Leuenberger C, Rechsteiner T, Soltermann A, Ulrich S, Weder W. European Respiratory Journal. 2015;46:PA583. DOI: 10.1183/13993003.congress-2015.PA583. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lu H, Xu J, Yu Z, Li J, Qiu Y, Zhang W. European Respiratory Journal. 2015;46:PA4360. DOI: 10.1183/13993003.congress-2015.PA4360. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wang LQ, Wang CL, Xu LN, Hua DF. The expression research of miR-210 in the elderly patients with COPD combined with ischemic stroke. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2016;20:4756–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Conickx G, Mestdagh P, Avila Cobos F, Verhamme FM, Maes T, Vanaudenaerde BM. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;195:43–56. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201506-1182OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Li Z, Han N, Tian Y. MicroRNA-130a promotes apoptosis of alveolar epithelia in COPD patients by inhibiting autophagy via the down-regulation of ATG16L expression. Int J Clin Experiment Med. 2016;9:23039–47. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ding Y, Tian Z, Yang H, Yao H, He P, Ouyang Y, et al. MicroRNA expression profiles of whole blood in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int J Clin Experiment Pathol. 2017;10:4860–5. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Shen W, Liu J, Zhao G, Fan M, Song G, Zhang Y, et al. Repression of toll-like receptor-4 by microRNA-149-3p is associated with smoking-related COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2017;12:705–15. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S128031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Liu H, Tao Y, Chen M, Yu J, Li WJ, Tao L, et al. Upregulation of microRNA-214 contributes to the development of vascular remodeling in hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension via targeting CCNL2. Sci Rep. 2016;6:24661. doi: 10.1038/srep24661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Wang R, Xu J, Liu H, Zhao Z. Peripheral leukocyte microRNAs as novel biomarkers for COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2017;12:1101–12. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S130416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Xie L, Yang F, Sun S. Expression of miR-21 in peripheral blood serum and mononuclear cells in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and its clinical significance. Zhong Nan Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban. 2016;41:238–43. doi: 10.11817/j.issn.1672-7347.2016.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Leidinger P, Keller A, Borries A, Huwer H, Rohling M, Huebers J, et al. Specific peripheral miRNA profiles for distinguishing lung cancer from COPD. Lung Cancer. 2011;74:41–7. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2011.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Sanfiorenzo C, Ilie MI, Belaid A, Barlési F, Mouroux J, Marquette CH, et al. Two panels of plasma microRNAs as non-invasive biomarkers for prediction of recurrence in resectable NSCLC. PLoS One. 2013;8:e54596. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Ellis KL, Cameron VA, Troughton RW, Frampton CM, Ellmers LJ, Richards AM, et al. Circulating microRNAs as candidate markers to distinguish heart failure in breathless patients. Eur J Heart Fail. 2013;15:1138–47. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hft078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Saeedi Borujeni MJ, Esfandiary E, Taheripak G, Codoñer-Franch P, Alonso-Iglesias E, Mirzaei H, et al. Molecular aspects of diabetes mellitus: Resistin, microRNA, and exosome. J Cell Biochem. 2018;119:1257–72. doi: 10.1002/jcb.26271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Gordon C, Gudi K, Krause A, Sackrowitz R, Harvey BG, Strulovici-Barel Y, et al. Circulating endothelial microparticles as a measure of early lung destruction in cigarette smokers. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;184:224–32. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201012-2061OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Strulovici-Barel Y, Staudt MR, Krause A, Gordon C, Tilley AE, Harvey BG, et al. Persistence of circulating endothelial microparticles in COPD despite smoking cessation. Thorax. 2016;71:1137–44. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2015-208274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Takahashi T, Kobayashi S, Fujino N, Suzuki T, Ota C, He M, et al. Increased circulating endothelial microparticles in COPD patients: A potential biomarker for COPD exacerbation susceptibility. Thorax. 2012;67:1067–74. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2011-201395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Lacedonia D, Carpagnano GE, Trotta T, Palladino GP, Panaro MA, Zoppo LD, et al. Microparticles in sputum of COPD patients: A potential biomarker of the disease? Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2016;11:527–33. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S99547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Fujita Y, Araya J, Ito S, Kobayashi K, Kosaka N, Yoshioka Y, et al. Suppression of autophagy by extracellular vesicles promotes myofibroblast differentiation in COPD pathogenesis. J Extracell Vesicles. 2015;4:28388. doi: 10.3402/jev.v4.28388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Burke H, Spalluto CM, Cellura D, Staples KJ, Wilkinson TMA. European Respiratory Journal. 2015;46:OA2930. DOI: 10.1183/13993003.congress-2015.OA2930. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Tan DB, Armitage J, Teo TH, Ong NE, Shin H, Moodley YP, et al. Elevated levels of circulating exosome in COPD patients are associated with systemic inflammation. Respir Med. 2017;132:261–4. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2017.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Pearson M. Is the primary mechanism underlying COPD: Inflammation or ischaemia? COPD. 2013;10:536–41. doi: 10.3109/15412555.2013.763781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Barnes PJ, Shapiro SD, Pauwels RA. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Molecular and cellular mechanisms. Eur Respir J. 2003;22:672–88. doi: 10.1183/09031936.03.00040703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Alipoor SD, Mortaz E, Garssen J, Movassaghi M, Mirsaeidi M, Adcock IM, et al. Exosomes and exosomal miRNA in respiratory diseases. Mediators Inflamm. 2016;2016:5628404. doi: 10.1155/2016/5628404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Tüfekci KU, Oner MG, Meuwissen RL, Genç S. The role of microRNAs in human diseases. Methods Mol Biol. 2014;1107:33–50. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-748-8_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Li CJ, Liu Y, Chen Y, Yu D, Williams KJ, Liu ML, et al. Novel proteolytic microvesicles released from human macrophages after exposure to tobacco smoke. Am J Pathol. 2013;182:1552–62. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2013.01.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Moon HG, Kim SH, Gao J, Quan T, Qin Z, Osorio JC, et al. CCN1 secretion and cleavage regulate the lung epithelial cell functions after cigarette smoke. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2014;307:L326–37. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00102.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Chew LP, Huttenlocher D, Kedem K, Kleinberg J. Fast detection of common geometric substructure in proteins. J Comput Biol. 1999;6:313–25. doi: 10.1089/106652799318292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Fujita Y, Kosaka N, Araya J, Kuwano K, Ochiya T. Extracellular vesicles in lung microenvironment and pathogenesis. Trends Mol Med. 2015;21:533–42. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2015.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Fujita N, Jaye DL, Kajita M, Geigerman C, Moreno CS, Wade PA, et al. MTA3, a mi-2/NuRD complex subunit, regulates an invasive growth pathway in breast cancer. Cell. 2003;113:207–19. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00234-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Letsiou E, Sammani S, Zhang W, Zhou T, Quijada H, Moreno-Vinasco L, et al. Pathologic mechanical stress and endotoxin exposure increases lung endothelial microparticle shedding. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2015;52:193–204. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2013-0347OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Takahashi T, Kubo H. The role of microparticles in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2014;9:303–14. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S38931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]