Abstract

Vaccinations are expected to aid in building immunity against pathogens. This objective often requires the addition of an adjuvant with certain vaccine formulations containing weakly immunogenic antigens. Adjuvants can improve antigen processing, presentation, and recognition, thereby improving the immunogenicity of a vaccine by simulating and eliciting an immune response. Chemokines are a group of small chemoattractant proteins that are essential regulators of the immune system. They are involved in almost every aspect of tumorigenesis, antitumor immunity, and antimicrobial activity and also play a critical role in regulating innate and adaptive immune responses. More recently, chemokines have been used as vaccine adjuvants due to their ability to modulate lymphocyte development, priming and effector functions, and enhance protective immunity. Chemokines that are produced naturally by the body’s own immune system could serve as potentially safer and more reliable adjuvant options versus synthetic adjuvants. This review will primarily focus on chemokines and their immunomodulatory activities against various infectious diseases and cancers.

Keywords: Adjuvants, chemokines, cytokines, vaccination, immune responses

Introduction

The goal of vaccination is the generation of strong and long-term protection to a specific pathogen. This is accomplished by eliciting robust immune responses to a targeted antigen which can induce long-term protection against infection. This target antigen could be a laboratory generated or altered pathogen, virus, bacteria, protein, or other foreign substance. These antigens can trigger responses from the host immune system that result in long-term immunity in the process. Certain vaccines, often containing live-attenuated antigens, are effective because they can stimulate the innate immunity to cascade into subsequent adaptive immune responses capable of clearing the targeted pathogens [1]. New developments in the field of vaccinology include DNA vaccines, novel peptides, recombinant viruses and proteins, and conjugates, all of which have been introduced commercially. This new generation of vaccines is safer and has fewer negative reactions or side effects than previous generations of vaccines made from live or whole-inactivated organisms. Conversely, these new advancements are sometimes not effective when a pathogen’s natural infection pathway does not convey long-lasting immunity [2]. To achieve the desired goal of protective immunity in these cases, the addition of a unique adjuvant to the vaccine is needed.

Adjuvants

Adjuvants are molecules or compounds that can enhance immune responses against co-administered antigens. Adjuvants increase immune responses to vaccines, enhance protection against pathogens, increase the speed of primary immune responses, activate the appropriate type of immunity to a given threat, increase the generation of memory responses, and can alter the specificity and breadth of the generated immune responses [3]. Adjuvants can also improve immune responses in populations where responses to vaccines are typically reduced, such as infants, the elderly, and immunocompromised patients. The functional outcomes of enhancing immune responses are manifold, including the allowance for reductions in the quantity of antigen contained in individual vaccine dose. This combination of less antigen and fewer doses can improve the vaccine supply worldwide and reduce the total cost of vaccine production.

There are several adjuvants that are currently in the market or in development but aluminum based adjuvants including aluminum hydroxide, aluminum phosphate, and alum still lead the way. Though alum has been known to cause type-1 hypersensitivity reactions post-administration in a small percentage of patients, it is among the few adjuvants that have been approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for human use [4]. Aluminum salts that have met FDA approval are aluminum hydroxide, aluminum phosphate, potassium aluminate sulfate, and mixed aluminum compounds. A significant number of other identified adjuvants are clearly more potent than alum but toxicity is the single most important impediment in introducing most such adjuvants to human use [5]. Some licensed vaccines containing alum or other adjuvants include: ASO4, comprised of aluminum hydroxide and monophosphoryl lipid A (MPL), is used to treat cervical cancer caused by human papillomavirus (HPV) [6]; AS03, comprised of oil compounds, vitamin E and squalene, is used in an influenza vaccine against H5N1 [7]. In Europe, MF59 is an adjuvant component of influenza vaccine for elderly patients (Fluad, Novartis Vaccines) [8] and AS04 (combination of alum and MPL, GlaxoSmithKline) is the adjuvant for some viral vaccines, e.g. Hepatitis B virus (HBV) and HPV [9].

Downsides of synthetic adjuvants

Aluminum based synthetic adjuvants continue to be the dominant adjuvants used. However, these synthetic adjuvants can sometimes trigger unwanted “hyperactive” immune responses, causing the immune system to over-react to antigens found in the vaccine formulations. This increases the probability of disrupting the host’s self-tolerance, leading the immune system to attack its own cells and tissues. It has been established that vaccine induced inflammatory responses can lead to permanent alterations in immune functionality and increase the risk of developing immunological disorders, including autoimmunity and long-term inflammation. Additionally, despite almost 80 years of widespread use, our knowledge behind the mechanisms of aluminum adjuvants is still remarkably limited. An equally concerning lack of data on the pharmacokinetics and toxicology of these compounds also remains problematic. To date, certain new and innovative adjuvants have shown acceptable safety profiles in clinical trials across a variety of applications and in post-licensure experiences, however many of these adjuvants still possess disadvantages such as high-costs, lack of stability and reliability, and most importantly high-toxicity [10] [11].

Chemokines/cytokines, which are produced naturally by the body’s own immune system, could serve as potentially safer and more reliable adjuvant options versus synthetic adjuvants. Vaccine safety, effectiveness, and toxicity could all be improved by using immunostimulators that are naturally non-toxic, have well understood mechanisms, and are adaptable to many types and modes of vaccines. The current review is concerned with the importance of natural and non-toxic adjuvants and their widespread use in the vaccine industry. Published studies on the relevant topics were analyzed and compared to create a composite view of the topic. In this review, we have emphasized the role of various chemokines as adjuvants in the treatment of many diseases and cancers.

Cytokines and chemokines

Cytokines are a broad category of small proteins (~5–20 kDa) that are important in cell signaling [12]. Cytokines include chemokines, interferons, interleukins, tumor necrosis factor, and lymphokines. Traditional adjuvants’ mode of action is to stimulate the creation of an environment that promotes immunity. For example, aluminum salts and Freund’s adjuvants have been linked to IFN-γ, IL-2, or IL-12 for establishing both innate and adaptive immunity. Instead of using an adjuvant to induce the production of specific cytokines, these cytokines can now be used directly as adjuvants either alone or in combination with other adjuvants [13] [14].

In one of our recent findings, we also studied a novel cytokine, GIFT4, engineered by fusing GM-CSF and IL-4. We observed that GPI-anchored GIFT4 containing virus-like particles (VLPs) induced higher levels of systemic antibody responses with significantly increased binding avidity and improved neutralizing breadth and potency to a panel of selected strains, as well as higher levels of IgG and IgA at several mucosal sites [15].

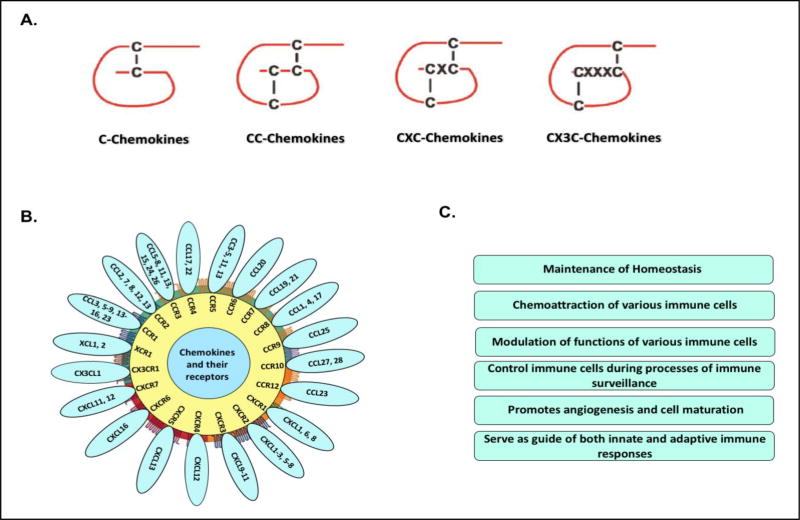

Chemokines are a family of chemoattractant cytokines which play a vital role in cell migration and in induction of cell movement in response to a chemical gradient by a process known as chemotaxis. Chemokines are small proteins (8–10 kDa) and are present in all vertebrate animals as well as in some microbes including bacteria and viruses, but none have yet been identified in other non-vertebrates [16]. Historically, chemokines have been known by various names including the SIS family, SIG family, SCY family, the intercrines, and the PF4 superfamily. The action of a chemokine is mediated through chemokine receptors, members of the G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) family, which can stimulate signal transduction pathways inside the cell when they are activated [17]. To date, there are more than 50 chemokines and 18 chemokine receptors identified. These molecules are classified into four families (CC, CXC, C, and CX3C) based on the way the first two conserved cysteine residues are arranged, creating a structural motif [18, 19]. Chemokines have evolved to become an integral part in the many critical roles involved in regulating innate and adaptive immune responses [20]. Chemokines modulate lymphocyte development, priming and effector functions, and play a vital role in immune surveillance. Many chemokines have been shown to be effective immunological adjuvants in a variety of model systems, enhancing protection induced by viral, bacterial, and parasitic vaccines [21]. These chemokines have also increased various immunological parameters in tumor immunization models and clinical trials [22]. Chemokines types, binding to their respective receptors and their generalized functions have been demonstrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Chemokines at a glance: Figure represent the (A) types of various chemokines; (B) Binding of chemokines with their receptors; and (C) functions of various chemokines.

Immunomodulatory studies of chemokines

More recently, chemokines have found a use as vaccine adjuvants, due to their ability to regulate immune responses and enhance the protective immunity [23–25]. Chemokine adjuvants can modulate the direction and magnitude of induced immune responses generated by DNA, protein, subunit or peptide vaccines. However, most of the chemokine adjuvants are currently struggling with dose-related toxicity issues. Additionally, recombinant chemokines have displayed stability problems, giving them short half-lives and limiting their usefulness as vaccine adjuvants. Some of these limitations can be overcome by utilizing liposome or micro/nanoparticle encapsulation and co-administering chemokine expression vectors with DNA or protein-based vaccines, respectively.

With an array of chemokines and ligands to select from to target on immune cells, it becomes possible to tailor a vaccine’s effects by chemoattracting specific cell types. For example, antigen presenting cell (APCs) targeting approaches have been evaluated for influenza and HIV antigens. In these studies, antigenic delivery with chemokines such as CCL3 have resulted in enhanced immunogenicity and protection against these pathogens. The chemokine CCL3 has demonstrated the ability to attract natural killer (NK) and CD8+ T cells, and has been investigated as an adjuvant for effective vaccines [26].

In the CCL3 study, researchers expressed CCL3 together with a truncated HIV-1 Gag antigen in L. plantarum and observed a significant increased recruitment of T cells. Another finding strongly supports that the co-delivery of CCL3 by an adenovirus-based vaccine improves protection from retrovirus infection [27]. In the Friend retrovirus (FV) mouse model, CCL3 was co-expressed from adenoviral vectors, together with FV Gag and Env antigens. Env and Gag-Pol antigens coadministered with a vector encoding CCL3 induced higher virus-specific antibody titers and CD4+ T cell responses [27].

In addition, vaccine formulations targeting XCR1 on cross-presenting dendritic cells (DCs) using antigen fused to XCL1, the only known ligand for XCR1, induce protective CD8+ T cell responses against influenza virus and strengthen the role of chemokines in modulating host immunity [28].

Recently, we investigated the effects of GPI-anchored CCL28, a chemokine associated with mucosal surfaces, as an adjuvant with influenza VLPs in mice. We observed that the membrane bound form of CCL28 in influenza VLPs acted as a strong immunostimulator at both systemic and mucosal sites, and boosted a significant cross-protection in animals against heterologous viruses across a large distance [29, 30]. It was demonstrated that the use of CCL28 as an adjuvant has unique immunity modulating properties at various mucosal compartments. CCL28 attracts IgA, but not IgG or IgM producing cells, and promotes their migration to different mucosal sites [31]. Because of its specific role in orchestrating the localization of IgA antibody secreting cells (ASCs), we also analyzed the long-lasting mucosal adjuvanticity of GPI-anchored CCL28 co-incorporated in influenza VLPs. Our results suggest that the CCL28 induces significantly higher mucosal antibody responses involved in providing long-term cross-protection against H3N2 influenza viruses when compared to other vaccination groups [29].

In a separate report, rhesus macaques vaccinated with SIV DNA and CCR9L (CCL25) or CCR10L (CCL28/CCL27) adjuvants showed significant protection from multiple low-dose intravaginal challenges with SIVsmE660. In this study, four groups of animals consisting of five female rhesus macaques with pSIVmac239 pol and pSIV sooty mangabey were vaccinated with consensus Env and gag vaccine alone or in combination with CCR9L pCCL25 or CCR10Ls pCCL28 or pCCL27. Sixty-eight percent of all vaccinated animals remained either uninfected or had aborted infection compared to only 14% in the vaccine naïve group. The highest protection was observed in the CCR10L chemokines group, where 6 of 9 animals had aborted infection and two remained uninfected, leading to 89% protection. The induction of mucosal SIV-specific antibodies and neutralization titers correlated with trends in protection and these results indicate the role of chemokine in modulating immune responses [32].

Involvement of many other chemokines in the attraction of various immune cells were also discussed in detail later in the review especially in the ‘Homing of B and T cell’ section.

Chemokines and cancer vaccines

Current cancer vaccine approaches have failed to reliably induce robust B and T cell activation. It is thought that a lack of sufficient physical interaction with the necessary immune cells could be the cause. Chemokines, can increase the recruitment of relevant immune cells, e.g. DCs, macrophages, lymphocytes, and NK cells, directed toward tumor cells through their chemotactic properties. Over the last few decades, chemokines have been found to be involved in almost every aspect of tumorigenesis, antitumor immunity, and antimicrobial activity.

In a cancer immunity study, CCL3- and CCL20-recruited DCs were modified by adenovirus-transduced tumor-associated antigen, MAGE-1, and shown to stimulate anti-tumor immunity specific to gastric cancer ex vivo and in vivo. This system demonstrated the involvement of chemokines in recruiting DCs and may prove to be an efficient strategy for anti-tumor immunotherapy [33].

In another report, mice with a glioma tumor were given DCs pulsed with glioma cell lysate subcutaneously, while simultaneously being given an intratumoral injection of a plasmid coding for CXCL10. The mice given the combination therapy containing CXCL10 displayed significantly increased survival rates. The increased survival or potent antitumor immune responses could be directly correlated with chemotactic properties of CXCL10 towards activated dendritic and T cells [34].

CCL21, which enhances Th1 responses and assists in T cell migration to secondary lymph organs has been another popular cancer vaccine adjuvant. Mice who were injected with CCL21 into a hepatocellular carcinoma displayed improved survival, slowed tumor progression, and increased intratumoral T cell penetration [35]. CCL21 is constitutively expressed in various lymphoid tissues and binds to chemokine receptor CCR7 on mature DC and distinct T and B cell subpopulations. In vivo, CCL21 regulates the encounters between dendritic and T cells and thus is a key regulator of adaptive immune responses. CCL5 primarily controls T cell migration toward inflammation and tissue damage, as well as Th1 differentiation. Mice given tumor lysate followed with CCL5-expresseing vaccinia virus showed significant reductions in tumor growth and increased survival rates. Foundational research into chemokines and cancers have revealed key roles chemokines play in cancer immunity. The examples of research in this field above show how this knowledge is being applied to improve immune-cancer therapies. Table 1 displays the role of chemokines as immunostimulators with respect to various infections and tumors.

Table 1.

Role of Chemokines as adjuvants/ immunostimulators in different diseases

| Chemokines | Other name(s) |

Receptor | Pathogen/Diseases | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| CCL1 | I-309 | CCR8 | HIV/SIV. | [36] |

| TCA-3 | ||||

|

| ||||

| CCL2 | MCP-1 | CCR2 | Arthritis, Autoimmune diseases, neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease, Multiple sclerosis, Ischemic brain injury, HSV, Glioma. | [37] [25] [23] [38] |

|

| ||||

| CCL3 | MIP-1α | CCR1 | HSV, HIV/SIV, Gastric cancer, Influenza, Plasmacytoma, Multiple myeloma, B cell lymphoma. | [25] [23] [24] [33] [39] [40] |

|

| ||||

| CCL4 | MIP-1β | CCR1 | HSV. | [23] |

| CCR5 | ||||

|

| ||||

| CCL5 | RANTES | CCR5 | HSV, Lymphoma, Myelomonocytic leukemia. | [25] [41] [42] |

|

| ||||

| CCL7 | MARC | CCR2 | Melanoma, Human cervical carcinoma, Colorectal cancer, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Mastocytoma. | [43] [44] [45] [46] [47] |

| MCP-3 | ||||

|

| ||||

| CCL16 | LEC | CCR1 | Mammary carcinomas. | [48] |

| NCC-4 | CCR2 | |||

| LMC | CCR5 | |||

| Ckβ12 | CCR8 | |||

|

| ||||

| CCL17 | TARC | CCR4 | Melanoma, Colon carcinoma. | [49] [50] |

| Dendrokine | ||||

| ABCD-2 | ||||

|

| ||||

| CCL19 | ELC | CCR7 | HCV, HBV, Fibrosarcoma, Adenocarcinoma, Breast cancer, Ovarian carcinoma. | [51] [52] [53] [54] [55] |

| Exodus-3 | ||||

| Ckβ11 | ||||

|

| ||||

| CCL20 | LARC | CCR6 | Gastric cancer. | [33] |

| Exodus-1 | ||||

| Ckβ4 | ||||

|

| ||||

| CCL21 | SLC | CCR7 | Colon cancer, Melanoma, Bronchoalveolar carcinoma, Pulmonary adenocarcinomas. | [56] [57] [58] [59] |

| Exodus-2 | ||||

| Ckβ9 | ||||

| TCA-4 | ||||

|

| ||||

| CCL22 | MDC | CCR4 | Melanoma, Lung carcinoma, Ovarian carcinoma. | [49] [60] [61] |

| DC/β-CK | ||||

|

| ||||

| CCL27 | CTACK | CCR10 | Melanoma, HIV-1, Influenza, HCV, HBV. | [49] [62] [30] |

| ILC | ||||

| PESKY | ||||

|

| ||||

| CCL28 | MEC | CCR3 | HIV-1, Influenza, HCV, HBV. | [62] [30] |

| CCR10 | ||||

Possible mechanisms behind the immunomodulation properties of chemokines

(i) Homing of B and T cells

It has been recently discovered that certain chemokines are continuously expressed in lymphoid organs, and that these chemokines can attract both activated and naïve lymphocytes. This subset of chemokines with their corresponding receptors appear to play critical roles in the migration and trafficking of lymphocytes within these lymphoid organs [49, 63, 64].

Both CCL19 and CCL21 are produced by T zone stromal cells and interact with the chemokine receptor CCR7, which is required for DC and T cell trafficking into lymphoid T zones [65]. CCL21 is also made in high endothelial venules (HEVs), the pathway by which most lymphocytes enter the lymph nodes and Peyer’s patches. B cells also express CCR7, and therefore CCL21 plays an important role in trafficking B cells into HEVs, which then progress further into lymph nodes and Peyer’s patches [66].

The CXCL12 and its corresponding receptor CXCR4 are involved in ASCs migration towards both the bone marrow and secondary lymphoid organs. Recent studies have shown that ASCs may migrate out of the spleen or lymph nodes due to a loss in their ability to respond to the CCL19, CCL21, and CXCL13. These cells reach the boundaries of lymphoid compartments, and are then exposed to increased levels of CXCL12, which further influences their migration toward bone marrow and other secondary lymphoid organs [67].

(ii) Chemokines can alter APC and effector cell functions

Chemokines and their respective receptors are responsible for organizing the trafficking pattern between immunocompetent cells and secondary lymph organs. The creation of a successful antibody immune response is dependent on this trafficking. DCs are primarily responsible for either the creation or prevention of immune responses by priming or inducing tolerance in T cells [68].

Chemokines have been shown to play a major role in the recruitment of DCs to desired locations. The iDCs (immature) can be characterized by high levels of both phagocytic ability and MHC molecules, but are lacking in co-stimulatory molecules [69]. Various chemokines such as CCL21, CCL7, and CCL20 cause the migration of iDCs to sites of inflammation. Once iDCs arrive to inflamed or damaged tissue sites, they acquire an antigen, upregulate co-stimulatory molecules and can activate into mDCs (mature) [70]. These iDCs express CCR1, CCR2, CCR5, and CCR6, which are responsible for their chemotactic migration. The mDCs downregulate these same receptors while upregulating CCR7, CCL19 and CCL21 to guide the antigen loaded mDCs to the secondary lymph organs for further processing [71]. The formation of antigen-specific killer cells requires cytotoxic T cells to be primed by DCs and then licensed by CD4+ T cells. As such, naïve CD8+ and CD4+ T cells, are constantly looking for DCs presenting a matching antigen [72]. After receiving an inflammatory or danger signal, DCs begin to mature, and enhance the CCR7 expression [70, 73, 74]. Studies showed that a deficiency of CCR7 or its ligands, CCL19 and CCL21, leads to impaired DC migration [75, 76]. In addition, a recent study indicates that steady-state trafficking of skin DCs to the draining lymph nodes in peripheral tissues is also regulated by CCR7-mediated signaling and demonstrated that CCR7 plays a key role in governing the trafficking of DCs under both inflammatory and steady-state conditions [77].

Several chemokines are essential to this behavior. CCL3 and CCL4 are secreted by DCs in inflamed lymph nodes, which guide CCR5 expressing naïve CD8+ T cells to locations where they can interact with APCs [78]. Simultaneously, mDCs are secreting CCL19 which increases the antigenic response and scanning action of naïve CD4+ T cells [79]. By increasing CD8+ T cells’ interaction with APCs and increasing CD4+ T cells scanning action, the result is effective maturation of cytotoxic T cells. Once the T cells have differentiated, the trafficking pattern needs to return these cells back to the target area. This is accomplished by the downregulation of CCR7 and the upregulation of CCR1, CCR2, CCR3, CCR5, and CXCR3, which are receptors unique to chemokines expressed by cells in the target area [79].

Through this interplay of constitutively expressed chemokines in tissues and the up and down regulation of cell surface receptors, immune cells can migrate to sites of inflammation, acquire an antigen, mature, and then migrate again back into target tissues. The sources of chemokines act as beacons, guiding cells from a distance to an important local area where the environment is conducive to the development of healthy immune responses. We have discussed in detail the functions of various chemokines in context with different diseases including cancers in Table 2.

Table 2.

Different functions of Chemokines

| Chemokines | Functions | References |

|---|---|---|

| CCL1 | CCL1 attracts monocytes, NK cells, immature B cells, and immature dendritic cells by interacting with a cell surface chemokine receptor called CCR8. | [80] |

| CCL2 | CCL2 influences macrophage, monocyte, NK cell, basophil and T lymphocyte infiltration, which express chemokine receptors CCR2. | [81] |

| CCL3 | CCL3 functions as a chemoattractant for inflammatory cells and modulates functions of monocytes, B and T lymphocytes, and also influences hematopoietic stem/progenitor cell growth. | [82, 83] |

| CCL4 | CCL4 is a chemoattractant for natural killer cells, monocytes and a variety of other immune cells. CCL4 is a major HIV-suppressive factor produced by CD8+ T cells. | [84] |

| CCL5 | CCL5 promotes the migration and activation of several types of leukocytes expressing CCR1, CCR3, and CCR5. CCL5 has a strong chemotactic activity towards multiple immune cells, such as eosinophils, basophils, mast cells, monocytes, CTLs, naive CD4+ T cells, stimulated CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, NK cells, memory CD45RO+ T cells and immature DCs. | [85] |

| CCL7 | CCL7 can chemoattract a large panel of leukocytes including monocytes, eosinophils, basophils, DCs, NK cells and activated T lymphocytes by interaction with the CCR1, CCR2 and CCR3 receptors. | [43, 47] |

| CCL16 | CCL16 chemoattracts monocytes, lymphocytes and PMNs by binding to CCR1 and CCR8 receptors. | [86] |

| CCL17 | This chemokine specifically binds and induces chemotaxis in T cells and elicits its effects by interacting with the chemokine receptor CCR4. | |

| CCL19 | CCL19, produced by a subset of DCs and possibly by other nonlymphoid cells in T cell areas of lymphoid tissues, strongly attracts naive T cells and DCs and plays a central role in regulating the encounters between DC and T cells in secondary lymphoid tissues via interaction with CCR7. | [54] |

| CCL20 | CCL20 elicits its effects on its target cells by binding and activating the chemokine receptor CCR6 that is expressed on most B cells, effector/memory T cells and some subsets of DCs. | [87, 88] |

| CCL21 | The CCL21 interaction with CCR7 leads to establishment of the functional secondary lymphoid tissue microenvironment and angiogenesis blockage, respectively. | [89] |

| CCL22 | CCL22 is an active chemokine on DCs, NK cells and Th2 lymphocytes. This chemokine is secreted predominantly by DCs, and exerts its effects by interacting with CCR4. | [90] |

| CCL27 | CCL27 is expressed in the skin and selectively chemoattracts cutaneous lymphocyte-associated Ag (CLA)+ memory T and Langerhans cells. It can regulate migration of skin-homing lymphocytes. | [91] |

| CCL28 | CCL28 plays a role in the physiology of extracutaneous epithelial tissues, including diverse mucosal organs. CCL28 has dual roles in mucosal immunity as a chemoattractant for cells expressing CCR10 and/or CCR3 such as plasma cells and also as a broad-spectrum antimicrobial protein secreted into low-salt body fluids. It drives the mucosal homing of T and B lymphocytes that express CCR10, and the migration of eosinophils expressing CCR3. | [92–95] |

Current advancement in using chemokines as adjuvants

Chemokines display their immunomodulatory functions with many pathogens. In the investigation of these topics, researchers were focused on the various aspects of chemokines in different forms, exhibiting different functions, and applications through various routes of vaccinations.

(i) Chemokine as an adjuvant in different forms

DNA-based vaccines induce antigen-specific cellular and humoral immune responses by encoding a foreign antigen. Despite many advantages, the low-immunogenicity and poor translation from rodent to human trials have revealed a vital necessity for adjuvants.

In many findings, chemokine expression plasmids or DNA based chemokine vaccine formulations showed substantial increases in the antigen-specific immunity. For example, CCL27 and CCL28 were used as adjuvants in the form of an expression plasmid with HIV-1 DNA vaccines and significant enhancement in the protective immune responses were observed [96]. CCL5 expressing plasmid was also used as an adjuvant in some of the studies and showed a significant increase in the antigen-specific immunity in animals. During HSV infection, researchers found that CCL2, CCL3 and CCL4 provide valuable adjuvanticity in mucosal DNA vaccination by providing linkage signals between innate and adaptive immunity. CCL3 as an adjuvant in the form of an expression plasmid was concluded to be a promising target in developing HSV-2 vaccine [97]. CCL21 has been used as a plasmid DNA adjuvant to enhance Tyrosinase related protein 2 (TRP2)-specific immunity in a melanoma cancer vaccine [57].

Another advantage of chemokines versus traditional adjuvants is their malleability. Chemokines are proteins that can be easily modified to add new functionality and form fusion proteins. CXCL10 has been studied as a GPI-anchored fusion protein in an NK based tumor therapy. CXCL10 is secreted by leukocytes and tissue cells and functions as a chemoattractant, mainly for lymphocytes and evokes a range of inflammatory responses. The results suggest enhanced recruitment of NK cells by CXCL10-mucin-GPI. This class of fusion proteins represents a novel adjuvant in cellular immunotherapy [98].

In another study, the CXCL10-mucin-GPI chimera fusion protein showed promising results as a future cellular immunotherapy [99]. The underlying concept of a chemokine head fused to the mucin domain and a GPI anchor signal sequence may be expanded into a broader family of reagents that will allow targeted recruitment of cells in various settings.

Chemokine CXCL10 and CCL7 fused to lymphoma Ig variable regions (sFv) elicited in vitro chemotactic responses and in vivo inflammatory responses. Immunity was not elicited by controls, including fusions with irrelevant sFv; fusions with a truncated chemokine that lacked receptor binding and chemotactic activity, mixtures of free chemokine and sFv proteins, or naked DNA plasmid vaccines encoding unlinked sFv and chemokine. Researchers concluded in their study that sFv-chemokine fusion proteins induce protective and strong T cell dependent antitumor immunity [100] .

Simultaneously, the soluble form of CX3CL1 has also been studied, which helps to recruit lymphocytes, DCs, and NK cells. In this metastatic colon cancer mouse model study, CX3CL1 exerts strong antitumor activity in its soluble form too when compared with other vaccine formulations. CX3CL1 as a soluble protein causes significant increase in the migration of NK cells, cytotoxic T lymphocytes, and macrophages [101].

In our recent finding, we studied a GPI-anchored form of CCL28 in VLPs and compared the results with its soluble form in mice. We observed that the GPI-anchored form provides effective and long-lasting mucosal immunity against H3N2 viruses when compared to the soluble form of CCL28 [30] [29].

The intrinsic attributes of chemokines allow for them to be used as adjuvants in different forms, whether that be a soluble form coadministered with the vaccine, a plasmid DNA adjuvant, or a chimeric recombinant protein. This makes the use of chemokines as adjuvants incredibly adaptable to any vaccine application.

(ii) Chemokines adjuvants delivered through different vaccination routes

The route of vaccination is important in influencing immune responses at the initial site of pathogen invasion where protection is most effective. Immune responses required for protection can differ vastly depending on the individual pathogen, adjuvant used or route of vaccinations [102].

For the generation of effective protective immunity, scientists have used various routes of vaccination when chemokines were used as immunostimulating agents. For instance, CCL2, CCL3, CCL4, CXCL2, CXCL3 and many more chemokines were studied as adjuvants and delivered in animals through the intranasal route, which is one of the best vaccination routes for the development of mucosal immunity [102].

The delivery of vaccine components through other routes such as intradermal, subcutaneous, and intramuscular are also common routes of immunization. In a recent study, CXCL9 and CXCL10 showed significantly higher adjuvanticity when immunized intratumorally [103] . As CCL28 and CCL27 showed immunoprotective effects on mucosal sites and epidermal sites, their applications through various mucosal and skin routes have been studied [96]. In addition, successful vaccination approaches using epicutaneous and microneedle delivery platforms have been thoroughly studied in models of influenza with some of the chemokines.

Again, chemokines make very flexible adjuvants because they can be delivered by any possible vaccination route. In some cases, a chemokine may be particularly well suited to one route or another depending on the immune cells it interacts with. Matching chemokines to their optimal vaccination route provides another area of possibilities in chemokine adjuvant research.

Chemokines and toxicity

Vaccines play an important role in modern medicine in the prevention of diseases including cancers. Most of the available vaccines work under the basic premise that the immune system becomes primed against a possible future exposure upon vaccination, therefore, providing protection to an individual. Developing adjuvants is challenging, and adjuvants are under regulatory scrutiny because of theoretical and reported safety concerns [104].

As mention earlier in the review, the addition of synthetic adjuvants may induce “hyperactive” immune responses and can increase the risk of developing autoimmune diseases (AID). Possible safety concerns have arisen from studies in which adjuvants have induced AID in various animal models and from reports that diverse compounds with adjuvant activity could be associated with silicosis, Gulf war syndrome (GWS), macrophagic myofasciitis (MMF), and post-vaccination phenomena [105]. The recent cases of narcolepsy observed during the 2009 pandemic influenza campaign with an AS03-adjuvanted vaccine have further heightened awareness.

Certain adjuvants have specific receptor targets that strongly stimulate the immune system via pattern recognition receptors (PRRs), including toll-like receptors (TLRs), and stimulating such targets could theoretically increase the risk of initiation or progression of systemic AID [106]. Chemokines are produced naturally by the body’s own immune system, could serve as potentially safer and more reliable adjuvant options versus synthetic adjuvants. The immune “hyperactive” should not be a potential drawback when chemokines, in an optimum dose, are used as adjuvant. Chemokines induced antigen-specific immune responses by two possible mechanism of actions: 1) by recruiting various immune cells at the site of injection, or/and 2) modulating effector functions of these chemoattracted immune cells. These two mechanisms should not generate toxicity. Though the generation of toxicity with some of vaccine studies containing chemokines have been highlighted, this could be related with the high dose of chemokines used in the vaccines’ formulations and more work should be done to identify optimal dosages of chemokine adjuvants.

Therapeutic potential of chemokines

A major role of chemokines is to mediate various immune cell migration through interaction with G-protein-coupled receptors. As a potential therapeutic, various delivery systems have been developed to utilize the chemokine properties for combating disease. Chemokines have been administered through various delivery strategies such as viral and mutant viral vectors expressing chemokines, genetically modified dendritic cells with chemokine or chemokine receptors, engineered chemokine-expressing tumor cells and pDNA encoding chemokines.

In addition, chemokines induce more effective antitumor immunity when used as adjuvants. In this regard, chemokines are codelivered along with antigens or fused as a targeting unit with antigenic moieties. In the current review, we have discussed in detail the immunomodulatory properties of various chemokines with respect to many diseases and cancers. The actions of chemokines may be intrinsically therapeutic or immunomodulatory. For example, it has been shown that epigenetic repression of CXCL9 and CXCL10 is a tumor immune-evasion mechanism. However, removing this repression or otherwise creating high expression of these two chemokines was found to increase T cell tumor infiltration and slowed down tumor progression [107]. Simultaneously, a research group found that a single injection of COAM into a tumor site demonstrates potent anti-tumor properties that were mediated through chemokine induction. COAM both binds to CXCL6 and upregulates the expression of CXCL6. This induction and concentration of CXCL6 subsequently leads to a massive chemotactic recruitment of anti-tumor myeloid cells into the tumor [108].

While the beneficial actions of chemokines revolve around their regulation of immune cell migration, the results of the immune cell migration may be thought of as either therapeutic or of adjuvant properties depending on the application.

Clinical trials with chemokines as adjuvants

The best hope for the prevention of infectious diseases, especially in resource-poor countries, is an effective preventive vaccine. Although generalized adjuvants have long been used to enhance the immune response to vaccines, the use of chemokine adjuvants with specific immune modulatory functions allows for the manipulation of the host response to both enhance overall immunogenicity and direct the nature of the response toward a Th1 or Th2 pathway.

Chemokine formulations with various immunogens are being considered for in vitro studies, pre-clinical and clinical trials. For example, a genetically modified leukemia/lymphoma vaccine that expresses CCL3 plus IL-2 or CCL3 plus GM-CSF has been studied [109]. Intradermal injection of adenovirus-CCL21 transduced class I peptide-pulsed DC [117] and intratumoral autologous DC-adenovirus CCL21 [118] vaccines are in phase I clinical trials for the treatment of malignant melanoma and stage IIIB-IV or recurrent non-small cell lung cancer, respectively. Another chemokine, XCL1 is being studied with IL-2 gene (CHESAT tumor vaccine) and is in phase I/II clinical trials for curing neuroblastoma [119].

Future perspective

Ongoing investigations into chemokines’ roles as adjuvants are producing positive results. Chemokines have the potential to display fewer or no cytotoxic effects as they are produced naturally by the host’s immune system. Several immunological fields have shown great interest in utilizing chemokines as adjuvants. In cancer immunotherapies, chemokines have shown great potential in overcoming tumor tolerance by increasing tumor eradication and enhancing effector cell priming, APC antigen presentation, and memory T cell responses. Several studies utilizing chemokines in cancer immunotherapies have progressed from pre-clinical studies into Phase I and even Phase II trials. Further investigation into which chemokines will yield optimal therapeutic results in response to specific tumors is needed. However, in the next 5 to 10 years we expect to see advances in targeted chemokine based therapies. Treatments for diseases, mostly with mucosal points of origin, have also been shown to be bolstered by chemokine based therapies. We expect to see several combination chemokine therapies progress from pre-clinical trials into clinical trials or progress into further phases in the near future.

Conclusion

The major purpose of this review is to introduce chemokines’ application in preventing or curing various infectious diseases and cancers. Many delivery systems including plasmid DNA encoding chemokines, chemokine targeting of DCs or tumor cells, and chemokine expressing live vaccines have been evaluated in various experimental models. Currently, many studies are showing significant benefits from the use of a combination of various chemokines in combating cancers or infectious diseases. Some studies applied conventional therapies such as cytotoxic chemotherapy together with chemokine-based immunotherapy. The principal aims of combination therapies are to synergistically enhance antibody responses and potentially reduce toxic side-effects.

Chemokine based adjuvants have a great deal of potential. These adjuvants can be fine-tuned with genetic manipulation to produce the ideal chimeric chemokine for the application at hand. The versatility of delivery routes means chemokine adjuvants have to potential to be used in a broad range of applications. Ultimately, the chemotactic signaling of chemokines combined with their flexibility in form and delivery has allowed researchers to begin developing vaccines and cures that would not have been possible before. This potency is evident in the wide spectrum of applications presented within this review: HIV, influenza, HSV, carcinomas, melanomas, and blastomas. As research progresses and data accumulates, chemokines will become more powerful and prevalent tools in immunology, undoubtable usurping the old guard of aluminum based adjuvants in the process.

Acknowledgments

We thank Gilbert X. Gonzalez for his help in reviewing of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of Interests:

There are no known conflicts of interests.

References

- 1.Hoebe K, Janssen E, Beutler B. The interface between innate and adaptive immunity. Nat Immunol. 2004;5(10):971–974. doi: 10.1038/ni1004-971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hilleman MR. Vaccines in historic evolution and perspective: a narrative of vaccine discoveries. Vaccine. 2000;18(15):1436–1447. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(99)00434-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vogel FR. Adjuvants in perspective. Dev Biol Stand. 1998;92:241–248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gupta RK, Rost BE, Relyveld E, Siber GR. Adjuvant properties of aluminum and calcium compounds. Pharm Biotechnol. 1995;6:229–248. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-1823-5_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Edelman R. Vaccine adjuvants. Rev Infect Dis. 1980;2(3):370–383. doi: 10.1093/clinids/2.3.370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tagliabue A, Rappuoli R. Vaccine adjuvants: the dream becomes real. Hum Vaccin. 2008;4(5):347–349. doi: 10.4161/hv.4.5.6438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leroux-Roels G. Prepandemic H5N1 influenza vaccine adjuvanted with AS03: a review of the pre-clinical and clinical data. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2009;9(8):1057–1071. doi: 10.1517/14712590903066695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mulligan MJ, Bernstein DI, Frey S, Winokur P, Rouphael N, Dickey M, Edupuganti S, Spearman P, Anderson E, Graham I, et al. Point-of-Use Mixing of Influenza H5N1 Vaccine and MF59 Adjuvant for Pandemic Vaccination Preparedness: Antibody Responses and Safety. A Phase 1 Clinical Trial. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2014;1(3) doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofu102. ofu102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Monie A, Hung CF, Roden R, Wu TC. Cervarix: a vaccine for the prevention of HPV 16, 18-associated cervical cancer. Biologics. 2008;2(1):97–105. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tomljenovic L, Shaw CA. Aluminum vaccine adjuvants: are they safe? Curr Med Chem. 2011;18(17):2630–2637. doi: 10.2174/092986711795933740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tomljenovic L. Aluminum and Alzheimer’s disease: after a century of controversy, is there a plausible link? J Alzheimers Dis. 2011;23(4):567–598. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-101494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boyaka PN, McGhee JR. Cytokines as adjuvants for the induction of mucosal immunity. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2001;51(1–3):71–79. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(01)00170-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grob PJ, Joller-Jemelka HI, Binswanger U, Zaruba K, Descoeudres C, Fernex M. Interferon as an adjuvant for hepatitis B vaccination in non- and low-responder populations. Eur J Clin Microbiol. 1984;3(3):195–198. doi: 10.1007/BF02014877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim JJ, Yang JS, Manson KH, Weiner DB. Modulation of antigen-specific cellular immune responses to DNA vaccination in rhesus macaques through the use of IL-2, IFN-gamma, or IL-4 gene adjuvants. Vaccine. 2001;19(17–19):2496–2505. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(00)00479-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Feng H, Zhang H, Deng J, Wang L, He Y, Wang S, Seyedtabaei R, Wang Q, Liu L, Galipeau J, et al. Incorporation of a GPI-anchored engineered cytokine as a molecular adjuvant enhances the immunogenicity of HIV VLPs. Sci Rep. 2015;5:11856. doi: 10.1038/srep11856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wiedle G, Dunon D, Imhof BA. Current concepts in lymphocyte homing and recirculation. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. 2001;38(1):1–31. doi: 10.1080/20014091084164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang L, LiWang PJ. Chemokine-receptor interactions: solving the puzzle, piece by piece. Structure. 2014;22(11):1550–1552. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2014.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bachelerie F, Ben-Baruch A, Burkhardt AM, Combadiere C, Farber JM, Graham GJ, Horuk R, Sparre-Ulrich AH, Locati M, Luster AD, et al. International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. [corrected]. LXXXIX. Update on the extended family of chemokine receptors and introducing a new nomenclature for atypical chemokine receptors. Pharmacol Rev. 2014;66(1):1–79. doi: 10.1124/pr.113.007724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bachelerie F, Graham GJ, Locati M, Mantovani A, Murphy PM, Nibbs R, Rot A, Sozzani S, Thelen M. New nomenclature for atypical chemokine receptors. Nat Immunol. 2014;15(3):207–208. doi: 10.1038/ni.2812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mariani M, Panina-Bordignon P. Analysis of homing receptor expression on infiltrating leukocytes in disease states. J Immunol Methods. 2003;273(1–2):103–114. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(02)00503-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smit JJ, Lukacs NW. A closer look at chemokines and their role in asthmatic responses. Eur J Pharmacol. 2006;533(1–3):277–288. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2005.12.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Esche C, Stellato C, Beck LA. Chemokines: key players in innate and adaptive immunity. J Invest Dermatol. 2005;125(4):615–628. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2005.23841.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eo SK, Lee S, Chun S, Rouse BT. Modulation of immunity against herpes simplex virus infection via mucosal genetic transfer of plasmid DNA encoding chemokines. J Virol. 2001;75(2):569–578. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.2.569-578.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lu Y, Xin KQ, Hamajima K, Tsuji T, Aoki I, Yang J, Sasaki S, Fukushima J, Yoshimura T, Toda S, et al. Macrophage inflammatory protein-1alpha (MIP-1alpha) expression plasmid enhances DNA vaccine-induced immune response against HIV-1. Clin Exp Immunol. 1999;115(2):335–341. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1999.00793.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sin J, Kim JJ, Pachuk C, Satishchandran C, Weiner DB. DNA vaccines encoding interleukin-8 and RANTES enhance antigen-specific Th1-type CD4(+) T-cell-mediated protective immunity against herpes simplex virus type 2 in vivo. J Virol. 2000;74(23):11173–11180. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.23.11173-11180.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Allen F, Rauhe P, Askew D, Tong AA, Nthale J, Eid S, Myers JT, Tong C, Huang AY. CCL3 Enhances Antitumor Immune Priming in the Lymph Node via IFNgamma with Dependency on Natural Killer Cells. Front Immunol. 2017;8:1390. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kuczkowska K, Mathiesen G, Eijsink VG, Oynebraten I. Lactobacillus plantarum displaying CCL3 chemokine in fusion with HIV-1 Gag derived antigen causes increased recruitment of T cells. Microb Cell Fact. 2015;14:169. doi: 10.1186/s12934-015-0360-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fossum E, Grodeland G, Terhorst D, Tveita AA, Vikse E, Mjaaland S, Henri S, Malissen B, Bogen B. Vaccine molecules targeting Xcr1 on cross-presenting DCs induce protective CD8+ T-cell responses against influenza virus. Eur J Immunol. 2015;45(2):624–635. doi: 10.1002/eji.201445080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mohan T, Berman Z, Luo Y, Wang C, Wang S, Compans RW, Wang BZ. Chimeric virus-like particles containing influenza HA antigen and GPI-CCL28 induce long-lasting mucosal immunity against H3N2 viruses. Sci Rep. 2017;7:40226. doi: 10.1038/srep40226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mohan T, Kim J, Berman Z, Wang S, Compans RW, Wang BZ. Co-delivery of GPI-anchored CCL28 and influenza HA in chimeric virus-like particles induces cross-protective immunity against H3N2 viruses. J Control Release. 2016;233:208–219. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2016.05.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lazarus NH, Kunkel EJ, Johnston B, Wilson E, Youngman KR, Butcher EC. A common mucosal chemokine (mucosae-associated epithelial chemokine/CCL28) selectively attracts IgA plasmablasts. J Immunol. 2003;170(7):3799–3805. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.7.3799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kutzler MA, Wise MC, Hutnick NA, Moldoveanu Z, Hunter M, Reuter MA, Yuan S, Yan J, Ginsberg AA, Sylvester A, et al. Chemokine-adjuvanted electroporated DNA vaccine induces substantial protection from simian immunodeficiency virus vaginal challenge. Mucosal Immunol. 2016;9(1):13–23. doi: 10.1038/mi.2015.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.He S, Wang L, Wu Y, Li D, Zhang Y. CCL3 and CCL20-recruited dendritic cells modified by melanoma antigen gene-1 induce anti-tumor immunity against gastric cancer ex vivo and in vivo. Journal of experimental & clinical cancer research : CR. 2010;29:37. doi: 10.1186/1756-9966-29-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li B, Li Q, Zhao QL, Wei XB, Zhang XH, Wu CQ, Zhong CP. Murine dendritic cells modified with CXCL10 gene and tumour cell lysate mediate potent antitumour immune responses in mice. Scand J Immunol. 2007;65(1):8–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.2006.01861.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nguyen-Hoai T, Baldenhofer G, Sayed Ahmed MS, Pham-Duc M, Vu MD, Lipp M, Dorken B, Pezzutto A, Westermann J. CCL21 (SLC) improves tumor protection by a DNA vaccine in a Her2/neu mouse tumor model. Cancer Gene Ther. 2012;19(1):69–76. doi: 10.1038/cgt.2011.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tsuji T, Fukushima J, Hamajima K, Ishii N, Aoki I, Bukawa H, Ishigatsubo Y, Tani K, Okubo T, Dorf ME, et al. HIV-1-specific cell-mediated immunity is enhanced by co-inoculation of TCA3 expression plasmid with DNA vaccine. Immunology. 1997;90(1):1–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1997.00117.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bose S, Cho J. Role of chemokine CCL2 and its receptor CCR2 in neurodegenerative diseases. Arch Pharm Res. 2013;36(9):1039–1050. doi: 10.1007/s12272-013-0161-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nagai M, Masuzawa T. Vaccination with MCP-1 cDNA transfectant on human malignant glioma in nude mice induces migration of monocytes and NK cells to the tumor. Int Immunopharmacol. 2001;1(4):657–664. doi: 10.1016/s1567-5769(00)00050-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fredriksen AB, Bogen B. Chemokine-idiotype fusion DNA vaccines are potentiated by bivalency and xenogeneic sequences. Blood. 2007;110(6):1797–1805. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-06-032938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ruffini PA, Grodeland G, Fredriksen AB, Bogen B. Human chemokine MIP1alpha increases efficiency of targeted DNA fusion vaccines. Vaccine. 2010;29(2):191–199. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.10.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kutubuddin M, Federoff HJ, Challita-Eid PM, Halterman M, Day B, Atkinson M, Planelles V, Rosenblatt JD. Eradication of pre-established lymphoma using herpes simplex virus amplicon vectors. Blood. 1999;93(2):643–654. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Inoue H, Iga M, Xin M, Asahi S, Nakamura T, Kurita R, Nakayama M, Nakazaki Y, Takayama K, Nakanishi Y, et al. TARC and RANTES enhance antitumor immunity induced by the GM-CSF-transduced tumor vaccine in a mouse tumor model. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2008;57(9):1399–1411. doi: 10.1007/s00262-008-0476-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wetzel K, Struyf S, Van Damme J, Kayser T, Vecchi A, Sozzani S, Rommelaere J, Cornelis JJ, Dinsart C. MCP-3 (CCL7) delivered by parvovirus MVMp reduces tumorigenicity of mouse melanoma cells through activation of T lymphocytes and NK cells. Int J Cancer. 2007;120(6):1364–1371. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wetzel K, Menten P, Opdenakker G, Van Damme J, Grone HJ, Giese N, Vecchi A, Sozzani S, Cornelis JJ, Rommelaere J, et al. Transduction of human MCP-3 by a parvoviral vector induces leukocyte infiltration and reduces growth of human cervical carcinoma cell xenografts. J Gene Med. 2001;3(4):326–337. doi: 10.1002/jgm.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hu JY, Li GC, Wang WM, Zhu JG, Li YF, Zhou GH, Sun QB. Transfection of colorectal cancer cells with chemokine MCP-3 (monocyte chemotactic protein-3) gene retards tumor growth and inhibits tumor metastasis. World J Gastroenterol. 2002;8(6):1067–1072. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v8.i6.1067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ryan AA, Spratt JM, Britton WJ, Triccas JA. Secretion of functional monocyte chemotactic protein 3 by recombinant Mycobacterium bovis BCG attenuates vaccine virulence and maintains protective efficacy against M. tuberculosis infection. Infect Immun. 2007;75(1):523–526. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00897-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fioretti F, Fradelizi D, Stoppacciaro A, Ramponi S, Ruco L, Minty A, Sozzani S, Garlanda C, Vecchi A, Mantovani A. Reduced tumorigenicity and augmented leukocyte infiltration after monocyte chemotactic protein-3 (MCP-3) gene transfer: perivascular accumulation of dendritic cells in peritumoral tissue and neutrophil recruitment within the tumor. J Immunol. 1998;161(1):342–346. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Giovarelli M, Cappello P, Forni G, Salcedo T, Moore PA, LeFleur DW, Nardelli B, Di Carlo E, Lollini PL, Ruben S, et al. Tumor rejection and immune memory elicited by locally released LEC chemokine are associated with an impressive recruitment of APCs, lymphocytes, and granulocytes. J Immunol. 2000;164(6):3200–3206. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.6.3200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Okada N, Sasaki A, Niwa M, Okada Y, Hatanaka Y, Tani Y, Mizuguchi H, Nakagawa S, Fujita T, Yamamoto A. Tumor suppressive efficacy through augmentation of tumor-infiltrating immune cells by intratumoral injection of chemokine-expressing adenoviral vector. Cancer Gene Ther. 2006;13(4):393–405. doi: 10.1038/sj.cgt.7700903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kanagawa N, Niwa M, Hatanaka Y, Tani Y, Nakagawa S, Fujita T, Yamamoto A, Okada N. CC-chemokine ligand 17 gene therapy induces tumor regression through augmentation of tumor-infiltrating immune cells in a murine model of preexisting CT26 colon carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2007;121(9):2013–2022. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hartoonian C, Sepehrizadeh Z, Tabatabai Yazdi M, Jang YS, Langroudi L, Amir Kalvanagh P, Negahdari B, Karami A, Ebtekar M, Azadmanesh K. Enhancement of Immune Responses by Co-delivery of CCL19/MIP-3beta Chemokine Plasmid With HCV Core DNA/Protein Immunization. Hepat Mon. 2014;14(3):e14611. doi: 10.5812/hepatmon.14611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Westermann J, Nguyen-Hoai T, Baldenhofer G, Hopken UE, Lipp M, Dorken B, Pezzutto A. CCL19 (ELC) as an adjuvant for DNA vaccination: induction of a TH1-type T-cell response and enhancement of antitumor immunity. Cancer Gene Ther. 2007;14(6):523–532. doi: 10.1038/sj.cgt.7701042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hou JM, Zhao X, Tian L, Li G, Zhang R, Yao B, Deng HX, Yang JL, Wei YQ. Immunotherapy of tumors with recombinant adenovirus encoding macrophage inflammatory protein 3beta induces tumor-specific immune response in immunocompetent tumor-bearing mice. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2009;30(3):355–363. doi: 10.1038/aps.2009.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Braun SE, Chen K, Foster RG, Kim CH, Hromas R, Kaplan MH, Broxmeyer HE, Cornetta K. The CC chemokine CK beta-11/MIP-3 beta/ELC/Exodus 3 mediates tumor rejection of murine breast cancer cells through NK cells. J Immunol. 2000;164(8):4025–4031. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.8.4025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gao JQ, Sugita T, Kanagawa N, Iida K, Okada N, Mizuguchi H, Nakayama T, Hayakawa T, Yoshie O, Tsutsumi Y, et al. Anti-tumor responses induced by chemokine CCL19 transfected into an ovarian carcinoma model via fiber-mutant adenovirus vector. Biological & pharmaceutical bulletin. 2005;28(6):1066–1070. doi: 10.1248/bpb.28.1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Flanagan K, Glover RT, Horig H, Yang W, Kaufman HL. Local delivery of recombinant vaccinia virus expressing secondary lymphoid chemokine (SLC) results in a CD4 T-cell dependent antitumor response. Vaccine. 2004;22(21–22):2894–2903. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2003.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yamano T, Kaneda Y, Huang S, Hiramatsu SH, Hoon DS. Enhancement of immunity by a DNA melanoma vaccine against TRP2 with CCL21 as an adjuvant. Mol Ther. 2006;13(1):194–202. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2005.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yang SC, Hillinger S, Riedl K, Zhang L, Zhu L, Huang M, Atianzar K, Kuo BY, Gardner B, Batra RK, et al. Intratumoral administration of dendritic cells overexpressing CCL21 generates systemic antitumor responses and confers tumor immunity. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10(8):2891–2901. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-03-0380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yang SC, Batra RK, Hillinger S, Reckamp KL, Strieter RM, Dubinett SM, Sharma S. Intrapulmonary administration of CCL21 gene-modified dendritic cells reduces tumor burden in spontaneous murine bronchoalveolar cell carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2006;66(6):3205–3213. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Guo J, Wang B, Zhang M, Chen T, Yu Y, Regulier E, Homann HE, Qin Z, Ju DW, Cao X. Macrophage-derived chemokine gene transfer results in tumor regression in murine lung carcinoma model through efficient induction of antitumor immunity. Gene Ther. 2002;9(12):793–803. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gao JQ, Alexandre LS, Tsuda Y, Katayama K, Eto Y, Sekiguchi F, Mizuguchi H, Hayakawa T, Nakayama T, Yoshie O, et al. Tumor-suppressive activities by chemokines introduced into OV-HM cells using fiber-mutant adenovirus vectors. Pharmazie. 2004;59(3):238–239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tyagi M, Kashanchi F. New and novel intrinsic host repressive factors against HIV-1: PAF1 complex, HERC5 and others. Retrovirology. 2012;9:19. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-9-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Miyasaka M, Tanaka T. Lymphocyte trafficking across high endothelial venules: dogmas and enigmas. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4(5):360–370. doi: 10.1038/nri1354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.von Andrian UH, Mempel TR. Homing and cellular traffic in lymph nodes. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3(11):867–878. doi: 10.1038/nri1222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yasuda T, Kuwabara T, Nakano H, Aritomi K, Onodera T, Lipp M, Takahama Y, Kakiuchi T. Chemokines CCL19 and CCL21 promote activation-induced cell death of antigen-responding T cells. Blood. 2007;109(2):449–456. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-04-018101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Okada T, Ngo VN, Ekland EH, Forster R, Lipp M, Littman DR, Cyster JG. Chemokine requirements for B cell entry to lymph nodes and Peyer’s patches. J Exp Med. 2002;196(1):65–75. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Achatz-Straussberger G, Zaborsky N, Konigsberger S, Luger EO, Lamers M, Crameri R, Achatz G. Migration of antibody secreting cells towards CXCL12 depends on the isotype that forms the BCR. Eur J Immunol. 2008;38(11):3167–3177. doi: 10.1002/eji.200838456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Coscia M, Biragyn A. Cancer immunotherapy with chemoattractant peptides. Semin Cancer Biol. 2004;14(3):209–218. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2003.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.McColl SR. Chemokines and dendritic cells: a crucial alliance. Immunol Cell Biol. 2002;80(5):489–496. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1711.2002.01113.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Dieu MC, Vanbervliet B, Vicari A, Bridon JM, Oldham E, Ait-Yahia S, Briere F, Zlotnik A, Lebecque S, Caux C. Selective recruitment of immature and mature dendritic cells by distinct chemokines expressed in different anatomic sites. J Exp Med. 1998;188(2):373–386. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.2.373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sallusto F, Palermo B, Lenig D, Miettinen M, Matikainen S, Julkunen I, Forster R, Burgstahler R, Lipp M, Lanzavecchia A. Distinct patterns and kinetics of chemokine production regulate dendritic cell function. Eur J Immunol. 1999;29(5):1617–1625. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199905)29:05<1617::AID-IMMU1617>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mandl JN, Liou R, Klauschen F, Vrisekoop N, Monteiro JP, Yates AJ, Huang AY, Germain RN. Quantification of lymph node transit times reveals differences in antigen surveillance strategies of naive CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(44):18036–18041. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1211717109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Chan VW, Kothakota S, Rohan MC, Panganiban-Lustan L, Gardner JP, Wachowicz MS, Winter JA, Williams LT. Secondary lymphoid-tissue chemokine (SLC) is chemotactic for mature dendritic cells. Blood. 1999;93(11):3610–3616. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sallusto F, Schaerli P, Loetscher P, Schaniel C, Lenig D, Mackay CR, Qin S, Lanzavecchia A. Rapid and coordinated switch in chemokine receptor expression during dendritic cell maturation. Eur J Immunol. 1998;28(9):2760–2769. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199809)28:09<2760::AID-IMMU2760>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Forster R, Schubel A, Breitfeld D, Kremmer E, Renner-Muller I, Wolf E, Lipp M. CCR7 coordinates the primary immune response by establishing functional microenvironments in secondary lymphoid organs. Cell. 1999;99(1):23–33. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80059-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Gunn MD, Kyuwa S, Tam C, Kakiuchi T, Matsuzawa A, Williams LT, Nakano H. Mice lacking expression of secondary lymphoid organ chemokine have defects in lymphocyte homing and dendritic cell localization. J Exp Med. 1999;189(3):451–460. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.3.451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ohl L, Mohaupt M, Czeloth N, Hintzen G, Kiafard Z, Zwirner J, Blankenstein T, Henning G, Forster R. CCR7 governs skin dendritic cell migration under inflammatory and steady-state conditions. Immunity. 2004;21(2):279–288. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hugues S, Scholer A, Boissonnas A, Nussbaum A, Combadiere C, Amigorena S, Fetler L. Dynamic imaging of chemokine-dependent CD8+ T cell help for CD8+ T cell responses. Nat Immunol. 2007;8(9):921–930. doi: 10.1038/ni1495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kaiser A, Donnadieu E, Abastado JP, Trautmann A, Nardin A. CC chemokine ligand 19 secreted by mature dendritic cells increases naive T cell scanning behavior and their response to rare cognate antigen. J Immunol. 2005;175(4):2349–2356. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.4.2349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Roos RS, Loetscher M, Legler DF, Clark-Lewis I, Baggiolini M, Moser B. Identification of CCR8, the receptor for the human CC chemokine I-309. J Biol Chem. 1997;272(28):17251–17254. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.28.17251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kuroda T, Kitadai Y, Tanaka S, Yang X, Mukaida N, Yoshihara M, Chayama K. Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 transfection induces angiogenesis and tumorigenesis of gastric carcinoma in nude mice via macrophage recruitment. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11(21):7629–7636. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Guan E, Wang J, Norcross MA. Identification of human macrophage inflammatory proteins 1alpha and 1beta as a native secreted heterodimer. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(15):12404–12409. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006327200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Wolpe SD, Davatelis G, Sherry B, Beutler B, Hesse DG, Nguyen HT, Moldawer LL, Nathan CF, Lowry SF, Cerami A. Macrophages secrete a novel heparin-binding protein with inflammatory and neutrophil chemokinetic properties. J Exp Med. 1988;167(2):570–581. doi: 10.1084/jem.167.2.570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Cocchi F, DeVico AL, Garzino-Demo A, Arya SK, Gallo RC, Lusso P. Identification of RANTES, MIP-1 alpha, and MIP-1 beta as the major HIV-suppressive factors produced by CD8+ T cells. Science. 1995;270(5243):1811–1815. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5243.1811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lapteva N, Huang XF. CCL5 as an adjuvant for cancer immunotherapy. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2010;10(5):725–733. doi: 10.1517/14712591003657128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Li J, Hu P, Khawli LA, Epstein AL. LEC/chTNT-3 fusion protein for the immunotherapy of experimental solid tumors. J Immunother. 2003;26(4):320–331. doi: 10.1097/00002371-200307000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Baba M, Imai T, Nishimura M, Kakizaki M, Takagi S, Hieshima K, Nomiyama H, Yoshie O. Identification of CCR6, the specific receptor for a novel lymphocyte-directed CC chemokine LARC. J Biol Chem. 1997;272(23):14893–14898. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.23.14893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Guo H, Chen G, Lu F, Chen H, Zheng H. Immunity induced by DNA vaccine of plasmid encoding the rhoptry protein 1 gene combined with the genetic adjuvant of pcIFN-gamma against Toxoplasma gondii in mice. Chin Med J (Engl) 2001;114(3):317–320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Liang CM, Zhong CP, Sun RX, Liu BB, Huang C, Qin J, Zhou S, Shan J, Liu YK, Ye SL. Local expression of secondary lymphoid tissue chemokine delivered by adeno-associated virus within the tumor bed stimulates strong anti-liver tumor immunity. J Virol. 2007;81(17):9502–9511. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00208-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Vulcano M, Albanesi C, Stoppacciaro A, Bagnati R, D’Amico G, Struyf S, Transidico P, Bonecchi R, Del Prete A, Allavena P, et al. Dendritic cells as a major source of macrophage-derived chemokine/CCL22 in vitro and in vivo. Eur J Immunol. 2001;31(3):812–822. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200103)31:3<812::aid-immu812>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Morales J, Homey B, Vicari AP, Hudak S, Oldham E, Hedrick J, Orozco R, Copeland NG, Jenkins NA, McEvoy LM, et al. CTACK, a skin-associated chemokine that preferentially attracts skin-homing memory T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96(25):14470–14475. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.25.14470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Hieshima K, Ohtani H, Shibano M, Izawa D, Nakayama T, Kawasaki Y, Shiba F, Shiota M, Katou F, Saito T, et al. CCL28 has dual roles in mucosal immunity as a chemokine with broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity. J Immunol. 2003;170(3):1452–1461. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.3.1452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.John AE, Thomas MS, Berlin AA, Lukacs NW. Temporal production of CCL28 corresponds to eosinophil accumulation and airway hyperreactivity in allergic airway inflammation. Am J Pathol. 2005;166(2):345–353. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62258-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kunkel EJ, Kim CH, Lazarus NH, Vierra MA, Soler D, Bowman EP, Butcher EC. CCR10 expression is a common feature of circulating and mucosal epithelial tissue IgA Ab-secreting cells. J Clin Invest. 2003;111(7):1001–1010. doi: 10.1172/JCI17244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Rodriguez MW, Paquet AC, Yang YH, Erle DJ. Differential gene expression by integrin beta 7+ and beta 7- memory T helper cells. BMC Immunol. 2004;5:13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2172-5-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Rainone V, Dubois G, Temchura V, Uberla K, Clivio A, Nebuloni M, Lauri E, Trabattoni D, Veas F, Clerici M. CCL28 induces mucosal homing of HIV-1-specific IgA-secreting plasma cells in mice immunized with HIV-1 virus-like particles. PLoS One. 2011;6(10):e26979. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Harandi AM, Svennerholm B, Holmgren J, Eriksson K. Protective vaccination against genital herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2) infection in mice is associated with a rapid induction of local IFN-gamma-dependent RANTES production following a vaginal viral challenge. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2001;46(6):420–424. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0897.2001.d01-34.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Muenchmeier N, Boecker S, Bankel L, Hinz L, Rieth N, Lapa C, Mendler AN, Noessner E, Mocikat R, Nelson PJ. A novel CXCL10-based GPI-anchored fusion protein as adjuvant in NK-based tumor therapy. PLoS One. 2013;8(8):e72749. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0072749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Nelson PJ, Muenchmeier N. Membrane-anchored chemokine fusion proteins: A novel class of adjuvants for immunotherapy. Oncoimmunology. 2013;2(11):e26619. doi: 10.4161/onci.26619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Biragyn A, Tani K, Grimm MC, Weeks S, Kwak LW. Genetic fusion of chemokines to a self tumor antigen induces protective, T-cell dependent antitumor immunity. Nat Biotechnol. 1999;17(3):253–258. doi: 10.1038/6995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Robinson LA, Nataraj C, Thomas DW, Cosby JM, Griffiths R, Bautch VL, Patel DD, Coffman TM. The chemokine CX3CL1 regulates NK cell activity in vivo. Cell Immunol. 2003;225(2):122–130. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2003.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Belyakov IM, Ahlers JD. What role does the route of immunization play in the generation of protective immunity against mucosal pathogens? J Immunol. 2009;183(11):6883–6892. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Bronger H, Singer J, Windmuller C, Reuning U, Zech D, Delbridge C, Dorn J, Kiechle M, Schmalfeldt B, Schmitt M, et al. CXCL9 and CXCL10 predict survival and are regulated by cyclooxygenase inhibition in advanced serous ovarian cancer. Br J Cancer. 2016;115(5):553–563. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2016.172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Sesardic D, Dobbelaer R. European union regulatory developments for new vaccine adjuvants and delivery systems. Vaccine. 2004;22(19):2452–2456. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2003.11.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Perricone C, Colafrancesco S, Mazor RD, Soriano A, Agmon-Levin N, Shoenfeld Y. Autoimmune/inflammatory syndrome induced by adjuvants (ASIA) 2013: Unveiling the pathogenic, clinical and diagnostic aspects. J Autoimmun. 2013;47:1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2013.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Marshak-Rothstein A. Toll-like receptors in systemic autoimmune disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6(11):823–835. doi: 10.1038/nri1957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Peng D, Kryczek I, Nagarsheth N, Zhao L, Wei S, Wang W, Sun Y, Zhao E, Vatan L, Szeliga W, et al. Epigenetic silencing of TH1-type chemokines shapes tumour immunity and immunotherapy. Nature. 2015;527(7577):249–253. doi: 10.1038/nature15520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Piccard H, Berghmans N, Korpos E, Dillen C, Aelst IV, Li S, Martens E, Liekens S, Noppen S, Damme JV, et al. Glycosaminoglycan mimicry by COAM reduces melanoma growth through chemokine induction and function. Int J Cancer. 2012;131(4):E425–436. doi: 10.1002/ijc.26465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Zibert A, Balzer S, Souquet M, Quang TH, Paris-Scholz C, Roskrow M, Dilloo D. CCL3/MIP-1alpha is a potent immunostimulator when coexpressed with interleukin-2 or granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor in a leukemia/lymphoma vaccine. Hum Gene Ther. 2004;15(1):21–34. doi: 10.1089/10430340460732436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Weber J. [accessed on 20 July 2013];Adenovirus CCL-21 Transduced MART-1/gp100/Tyrosinase/NY-ESO-1 Peptide-Pulsed Dendritic Cells Matured. Available online: http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT007986292012.

- 118.Lee J. [accessed on 20 July 2013];Vaccine Therapy in Treating Patients With Stage IIIB, Stage IV, or Recurrent Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Available online: http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT006010942013.

- 119.Louis C. [accessed on 20 July 2013];A Phase I/II Study Of Immunization With Lymphotactin And Interleukin 2 Gene Modified Neuroblastoma Tumor Cells (CHESAT) Available online: http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT007032222013.