Highlights

-

•

Fresh food can be produced under limited space and energy conditions providing 11 kg m-2 week-1 (leafy greens, herbs, radish, tomato and cucumber).

-

•

Applying spread harvest (weekly harvesting the oldest leaves of leafy greens) and increasing plant density increases fresh food production.

-

•

The quality of leafy greens often deteriorated at higher light intensities (600 μmol m-2 s-1).

-

•

The presented crop growth recipes and management will be applied in a mobile test facility at the Neumayer III Antarctic research station.

Keywords: LED lighting, Resource use efficiency, Spread harvesting, EDEN ISS, Antarctic

Abstract

This paper deals with vegetable cultivation that could be faced in a space mission. This paper focusses on optimization, light, temperature and the harvesting process, while other factors concerning cultivation in space missions, i.e. gravity, radiation, were not addressed. It describes the work done in preparation of the deployment of a mobile test facility for vegetable production of fresh food at the Neumayer III Antarctic research station. A selection of vegetable crops was grown under varying light and temperature conditions to quantify crop yield response to climate factors that determine resource requirement of the production system. Crops were grown at 21 °C or 25 °C under light treatments varying from 200 to 600 μmol m−2 s−1 and simulated the dusk and dawn light spectrum. Fresh food biomass was harvested as spread harvesting (lettuce), before and after regrowth (herbs) and at the end of cultivation.

Lettuce and red mustard responded well to increasing light intensities, by 35–90% with increasing light from 200 to 600 μmol m−2 s−1, while the other crops responded more variably. However, the quality of the leafy greens often deteriorated at higher light intensities. The fruit biomass of both determinate tomato and cucumber increased by 8–15% from 300 to 600 μmol m−2 s−1. With the increase in biomass, the number of tomato fruits also increased, while the number of cucumber fruits decreased, resulting in heavier individual fruits. Increasing the temperature had varied effects on production. While in some cases the production increased, regrowth of herbs often lagged behind in the 25 °C treatment. In terms of fresh food production, the most can be expected from lettuce, cucumber, radish, then tomato, although the 2 fruit vegetables require a considerable amount of crop management. Spread harvesting had a large influence on the amount of harvested biomass per unit area. In particular, yield of the 3 lettuce cultivars and spinach was ca. 400% than single harvesting. Increasing plant density and applying spread harvesting increased fresh food production. This information will be the basis for determining crop growth recipes and management to maximize the amount of fresh food available, in view of the constraints of space and energy requirement of such a production system.

1. Introduction

Production of food is essential in order to realize successful space missions for extended periods of time. As staple crops can be preserved dried for a long time, a priority is production of fresh vegetables, which has also been shown to have beneficial psychological effects for the crew members (Koga and Iwasaki, 2013; Odeh and Guy, 2017). The purpose of the EU-funded EDEN ISS project (Ground Demonstration of Plant Cultivation Technologies and Operation in Space) is to develop a growing system for fresh vegetables, that can operate under the constraints of a space mission. However, plant cultivation during space missions must cope with factors like gravity and radiation, which are difficult to properly address in plant cultivation on earth.

As deep space is still far away, the EDEN ISS project is limited to design and build a mobile test facility (MTF) in which crops can be cultivated for at least one full year, that will be deployed to the Neumayer III Antarctic research station (Zabel et al., 2016). The use of Antarctica as analogue for deep space lies particularly in the hostile external environment, being physically isolated and the limited resources available in terms of crew time, energy and volume. Therefore, it is necessary to define growth conditions and crop management that maximise the productivity of both space and energy, that is electricity to power artificial light and air conditioning. For instance, in order to maximize light use efficiency (LUE) of lettuce, Poulet et al. (2014) made use of targeted lighting, illuminating only the photosynthetic plant tissue. This was achieved by having the plants in fixed spots, which entails a large fraction of unused space during the early stage of the crops. Space is also a very limited resource in space missions, and to mimic this, the cultivation space in the MTF will be 40 racks of 40 × 60 cm, of which 22 are 30 cm high (cultivation space between the top of the rack and lamp), 16 are 80 cm and 2 are 160 cm. The issue is therefore to develop crop growing and management recipes that maximise productivity of both electricity and space. This requires some knowledge of the marginal value (in term of additional production) of both. That was the purpose of the work described here, which was carried out in climate rooms equipped similarly to the growing cabinets of the MTF. The development of these crop growth recipes may also be employed in vertical farming.

The first step is, rather obviously, the selection of suitable crops. While the aspect of human nutrition is obviously an important element in space farming, it has been expressed in earlier studies (Hoff et al., 1982, Massa et al., 2015). Due to the fact that the physical space for plant growth is very limiting in space missions, the focus was placed on the psychological component of a limited amount of fresh food. The desirable characteristics of ready-to-eat fresh vegetable products for their well-being have been expressed by former astronauts and crews that have over-wintered on Antarctica (Mauerer et al., 2016,We developed an objective selection method that differently prioritizes “hard” constraints (for instance, space) and “soft” constraints (such as harvest index or even spiciness) (Dueck et al., 2016). The method resulted in a diverse set of vegetable crops, each with their own specific requirements for optimal growth and production, like light intensity, light spectrum, temperature and humidity.

With a knowledge of the edible biomass that can be harvested per unit area per cultivation cycle of the individual crops, it becomes possible to set-up a crop plan (sowing and harvest dates) to maximise space utilisation; food production and diet variety.

Whereas light intensity (and spectrum) can be adapted in each single tray of the growing unit in the MTF, there will be one temperature and humidity set point. Therefore, the overall objectives of this work were:

-

•

Determine the “marginal” value of resources (light and temperature) in terms of [fresh] yield.

-

•

Collect suitable information for crop management planning that maximises productivity of the unit and ensures a varied diet.

2. Methods

Their limited size and high harvest index, ensure that leafy greens are always at the top of any list for “space vegetables” for fresh food (Hoff et al., 1982; Wheeler, 2004; Chunxiao and Hong, 2008; Massa et al., 2015). Our list was not an exception, although it did include a dwarf variety of tomato and a cocktail cucumber (as fruit crops) and radish as root crop. Besides different cultivars of lettuce, spinach, red mustard, Swiss chard and herbs were included for more taste and quality aspects. Two experiments were conducted to determine the influence of light intensity, and the influence of temperature at 2 different light levels on the growth of the vegetables and regrowth of some crops, harvested during or at the end of the growth period.

2.1. Influence of light intensity on crop growth

2.1.1. Plant material and growth conditions

Two consecutive trials were conducted to accommodate 9 different crops. Five crops were grown in the first trial: lettuce ‘Expertise’ (type Crispy Green; Rijk Zwaan, de Lier, NL) and ‘Outredgeous’ (type red Romaine; Johnny Seeds, Winslow, ME), red mustard ‘Frizzy lizzy’ and radish ‘Lennox’ (Bayer/HILD, DE), and chives ‘Staro’ (Johnny Seeds, Winslow, ME). In the second trial the following crops were grown: lettuce ‘Othilie’ (type Batavia; Rijk Zwaan, de Lier, NL), rocket ‘Rucola Cultivated’ (Seeds from Italy, Harrow, UK), Swiss chard ‘Red ruby’ (Johnny Seeds, Winslow, ME) and spinach ‘Golden Eye’ (Rijk Zwaan, de Lier, NL). Seeds were sown directly onto 2 cm rock wool plugs and were later transplanted into 7 × 7 cm rock wool blocks, or directly onto smaller rock wool blocks (4 × 4 cm) depending on the estimated final plant size. They were placed in 40 × 60 × 10 cm open trays and were given a nutrient solution with an ebb and flow system. The nutrient solution with an EC 1.7 and pH 5.8 was composed of, in mmol l−1: 11.5 NO3-, 1.0 SO4-, 1.25 P-, 1.0 NH4+, 6.75 K+, 2.63 Ca2+, 0.25 Cl- and 1.0 Mg2+; and in μmol l−1: 20 Fe, 25 B, 10 Mn, 5 Zn, 0.75 Cu and 0.5 Mo. The climatic conditions entailed a day/night temperature set points of 21/19 °C, a day/night relative humidity of 75/85%, 750 ppm CO2 and a 17 h photoperiod. The realised climate was 20.7/18.9 °C day/night; 76/83% RH day/night and 744 ppm CO2 during the light period.

2.1.2. Experimental design

Each trial took place within a period of 6 weeks in 2 climate chambers, the first in May/June, followed by the second trial in July/August 2016. Artificial light was supplied by LED lighting modules from Heliospectra AB, Götenburg, Sweden, with 4 programmable channels of blue (446 nm), red (663 nm), far red (736 nm) and white LEDs (5700 K) (Fig. 1). As Fig. 1 shows, the red and blue peak of the lamps correspond with peaks in the relative quantum efficiency of roses (Paradiso et al., 2011) earlier established by McCree (1972) for multiple crops. A choice was made to use one spectrum that covered photosynthetic active radiation (PAR), with relatively more red light than in sunlight and included far red radiation. A large number of studies have been performed with basic red and blue (RB) LED lighting, but recent research (Mazza and Ballaré, 2015; Massa et al., 2016; Park & Runkle, 2017) has indicated that the addition of far red and white or green light enhances plant growth and production in an environment without sunlight. Lin et al. (2013) and Cocetta et al. (2017) have also reported that a spectrum including more wave lengths than only RB also enhanced the plant quality (i.e. crispness, sweetness and shape). Thus a spectrum was chosen of 17% blue (400–500 nm), 12% green (500–600 nm), 71% red (600–700 nm) and 35 μmol m−2 s−1 far red radiation (Fig. 1), which is similar to that in the Advanced Plant Habitat (APH) designed to fly to the ISS in 2017 (Massa et al., 2016).

Fig. 1.

Spectrum of the 4 channel LED lighting assembly at a light intensity of 300 μmol m−2 s−1 (line), and the relative quantum efficiency per incident photon (symbols) (Paradiso et al., 2011).

The four treatments consisted of various light intensities, 200, 300, 450 and 600 μmol m−2 s−1. The average realised light intensities over all shelves and experiments at crop level (and standard deviation) were 198 ± 11, 292 ± 17, 436 ± 25 and 582 ± 42 μmol m−2 s−1. The standard deviation represents the horizontal distribution in the trays. The light intensity was weekly adjusted to maintain the same intensity at the top of the plant canopy.

Light was increased in 2 steps during the first hour of the photoperiod to the desired intensity, and decreased again at the end of the photoperiod. Sunrise and sunset were simulated with a natural a red:far red ratio of 0.7–0.8 (Holmes and Smith, 1977) for 15 min by providing a light intensity of 90 μmol m−2 s−1 with a red:far red ratio of 0.77. Far red (35 μmol m−2 s−1) was maintained during the whole photoperiod while the light intensity was increased, resulting in a red:far red ratio of 4 (at 200 μmol m−2 s−1), 6 (at 300 μmol m−2 s−1), 9 (at 450 μmol m−2 s−1) and 12 (at 600 μmol m−2 s−1). The light strategy is given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Light strategy employed during crop cultivation.

| Time | Light strategy | R:FR ratio |

|---|---|---|

| 04:00–04:15 | Simulation of sunrise, 90 μmol m−2 s−1 | 0.77 |

| 04:15–05:00 | 50% desired light intensity | |

| 05:00–20:00 | 100% desired light intensity | 4–12* |

| 20:00–20:45 | 50% desired light intensity | |

| 20:45–21:00 | Simulation of sunset, 90 μmol m−2 s−1 | 0.77 |

| 21:00–04:00 | Night |

depending on maximum light intensity.

Two types of harvesting treatments were given to the leafy greens under each light treatment, one tray in which a crop was grown for 6 weeks to final harvest (single harvest) and a second tray in which the oldest leaves of the same crop was harvested weekly (spread harvest). The crops were spaced to different densities depending on the crop and crop management. The density was 25 and 123 for lettuce plants m−2 for single and spread harvest respectively. Plant density for the spread harvest of red mustard, radish, rocket, Swiss chard and spinach was 625 plants m−2 and 625, 278, 333, 295, 156 plants m−2 respectively, for the single harvest. Plant density for chives was 1875 plants m−2 for both types of harvesting. After harvesting the chives, the plant stubs on rock wool blocks were placed under 300 μmol m−2 s−-1 for 8 days after which the regrowth was determined.

2.1.3. Measurements

Whole plants (above ground organs) or individual leaves were destructively harvested, single harvest treatments after 6 weeks and the spread harvest treatment intermittently starting 4 weeks after sowing. Radish (single harvest only) was harvested after 4 weeks. The fresh biomass was measured, then dried at 105 °C and dry weights were measured.

2.2. Influence of light intensity and temperature on crop growth and re-growth

In the following experiment, the influence of temperature on the growth rate and production of three leafy green vegetables, radish, two herbs and two fruit vegetables was assessed at 2 light intensities. The climate conditions of each climate chamber were comparable, with the exception of the day/night temperature.

2.2.1. Plant material and growth conditions

Eight crops were grown in this trial: lettuce ‘Expertise’ (type Crispy Green; Rijk Zwaan, de Lier, NL), red mustard ‘Frizzy lizzy’ (Bayer/HILD, DE), rocket ‘Rucola Cultivated’ (Seeds from Italy, Harrow, UK), chives ‘Purly’ (Johnny Seeds, Winslow, ME), parsley ‘Frise vert Fonce-Rina’ (Rijk Zwaan, de Lier, NL); radish ‘Lennox’ (Bayer/HILD, DE); cocktail cucumber ‘Quarto’ (Rijk Zwaan, de Lier, NL) and dwarf tomato F1 2414 (Vreugdenhil, NL).

The seeding procedure and nutrient solution composition are given in Section 2.1.1. The climatic conditions were set at 21/19 °C day/night and a relative humidity of 75%/85% day/night in one climate chamber and 25/23 °C and a relative humidity of 80%/88% day/night in the second climate chamber, both at 750 ppm CO2 and a 17 h photoperiod.

The realised climatic conditions are summarized in Table 2. The main difference between the two is the 4 °C temperature, both day and night.

Table 2.

Realised climate in each climate chamber.

| Climate condition | Chamber 1 |

Chamber 2 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day | Night | Day | Night | |

| Temperature (°C) | 20.8 | 18.9 | 24.8 | 22.9 |

| RH (%) | 76 | 81 | 81 | 89 |

| VPD (mbar) | 6 | 4 | 6 | 3 |

| CO2 (ppm) | 759 | 740 | ||

2.2.2. Experimental design

The experiment was performed during 17 weeks, in which the duration differed per crop: 17 weeks for tomato, cucumber, chives and parsley, 11 weeks for lettuce, and 2 trials of 4 weeks each for radish, rocket and red mustard. The latter 2 trials were repeated sequentially, and took place in August/September and October/November 2016. In each temperature regime, two light intensities were given: 300 and 600 μmol m−2 s−1, with the light spectrum described in Section 2.1.2. The 2 light intensities varied per shelf in each climate chamber and did not influence each other. The average intensities realised were 293 and 582 μmol m−2 s−1. Spread harvesting was performed on lettuce, chives and parsley which were harvested several times and allowed to regrow. The crops were spaced at densities of 83 plants m−2 (lettuce ‘Expertise’), 625 plants m−2 (red mustard radish and parsley) 1875 plants m−2 (chives), 8 plants m−2 (cucumber), 16 plants m−2 (tomato). Radish was started at 625 plants m−2 and spaced to 278 plants m−2 during the last week of cultivation.

2.2.3. Measurements

Whole plants (above ground organs) or individual leaves were destructively harvested; the single harvests after 4 weeks (red mustard, rocket, radish) or 6 weeks (chives, parsley) and spread harvesting intermittently for 11 weeks (lettuce ‘Expertise’). Regrowth of red mustard and rocket was measured after another 2 weeks. Regrowth of chives and parsley was measured several times at intervals of 4, 3.5 and 3 weeks. Harvestable fruits of cucumber and ripe fruits of tomato plants were harvested two times per week and the number and fresh weight of fruits per plant were determined. After 17 weeks whole plants (above ground) were harvested. The fresh biomass of leaves (and stem for cucumber and tomato) and fruits were measured, then dried at 105 °C and the dry weights were measured.

3. Results

3.1. Influence of light intensity on crop growth and regrowth

Shoot biomass production did not increase for all species with increasing light intensity (Table 3). However, the most obvious result observed in Table 3 is the large difference in crop fresh weight production expressed per unit area when spread harvesting was applied. Light intensity had little effect on production while the effect of spread harvesting was much larger.

Table 3.

Mean shoot biomass production (kg FW m−2 ± SE) of lettuce ‘Expertise’, ‘Outredgeous’ and ‘Othilie’, red mustard ‘Frizzy lizzy’, rocket ‘Rucola cultivated’, Swiss chard ‘Red ruby’, spinach ‘Golden eye’ grown under various light intensities and harvested during (spread harvest) or at the end of 42 days cultivation (single harvest). Means of lettuce are based on 6 (single harvest) and 20 (spread harvest) replicates; red mustard, rocket and Swiss chard on 20 replicates; spinach on 10 replicates.

| Mean shoot biomass production (kg FW m−2 ± SE) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Light (μmol m−2 s−1) | 200 | 300 | 450 | 600 | ||

| Crop | Harvest | Density (m−2) | ||||

| Lettuce ‘Expertise’ | single | 25 | 2.31 ± 0.14 | 2.94 ± 0.35 | 3.72 ± 0.19 | 2.90 ± 0.18 |

| spread | 123 | 10.61 ± 0.45 | 12.29 ± 0.63 | 12.18 ± 0.70 | 12.88 ± 0.93 | |

| Lettuce ‘Outredgeous’ | single | 25 | 2.07 ± 0.12 | 2.27 ± 0.24 | 2.40 ± 0.13 | 2.60 ± 0.12 |

| spread | 123 | 7.94 ± 0.33 | 8.82 ± 0.55 | 10.18 ± 0.61 | 10.70 ± 0.63 | |

| Lettuce ‘Othilie’ | single | 25 | 2.23 ± 0.09 | 1.91 ± 0.08 | 1.94 ± 0.21 | 2.19 ± 0.23 |

| spread | 123 | 7.98 ± 0.29 | 8.28 ± 0.22 | 9.26 ± 0.39 | 9.65 ± 0.58 | |

| Red mustard ‘Frizzy lizzy’ | single | 625 | 14.03 ± 1.99 | 9.80 ± 2.16 | 18.56 ± 6.61 | 16.54 ± 3.28 |

| spread | 625 | 9.36 ± 0.77 | 13.93 ± 2.45 | 10.29 ± 1.44 | 17.73 ± 3.32 | |

| Rocket ‘Rucola cultivated’ | single | 333 | 4.68 ± 0.33 | 4.43 ± 0.40 | 4.35 ± 0.61 | 3.38 ± 0.25 |

| spread | 625 | 5.90 ± 0.43 | 6.81 ± 0.51 | 4.91 ± 0.34 | 5.36 ± 0.42 | |

| Swiss chard ‘Ruby red’ | single | 295 | 7.24 ± 0.42 | 7.90 ± 0.72 | 8.07 ± 0.70 | 8.31 ± 0.65 |

| spread | 625 | 14.50 ± 0.81 | 15.83 ± 1.42 | 12.42 ± 0.80 | 14.35 ± 0.96 | |

| Spinach ‘Golden eye’ | single | 156 | 1.57 ± 0.23 | 1.88 ± 0.45 | 1.72 ± 0.17 | 1.54 ± 0.17 |

| spread | 625 | 5.52 ± 0.63 | 5.13 ± 0.79 | 6.82 ± 0.63 | 6.15 ± 0.96 | |

The response of the crops to increased light intensity was variable, even with a decrease in fresh weight production by rocket as the light intensity increased. The maximum increase in biomass between 200 and 600 μmol m−2 s−1 was a factor 1.61 for lettuce ‘Expertise’ and 1.89 for red mustard (Table 4). This varied between the various vegetables, but it appeared that increasing the light intensity up to 600 μmol m−2 s−1 may increase production in lettuce and red mustard, but results in a light energy and production loss for rocket and Swiss chard. High light intensities of 600 μmol m−2 s−1 however, often resulted in quality reduction, especially in the leafy green vegetables which often had harder, stiffer leaves (Fig. 2). In a subjective test by the harvesting crew harder leaves and an unpleasant texture in plants cultivated at 600 μmol m−2 s−1 were observed for rocket and Swiss chard. The only exception was for red mustard; plants became more firm at 450 μmol m−2 s−1 than at the lower light intensities.

Table 4.

Influence of increasing the light intensity above 200 μmol m−2 s−1 on the shoot biomass production (kg FW m−2 ± SE) of 7 vegetable crops, for both single harvests and spread harvests. Numbers indicate proportional shoot biomass fresh weight relative to that at 200 μmol m−2 s−1.

| Proportional shoot biomass relative to the biomass at 200 μmol m−2 s−1 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Light (μmol m−2 s−1) | 200 | 300 | 450 | 600 | |

| Crop | Harvest | ||||

| Lettuce ‘Expertise’ | single | 1 | 1.28 | 1.61 | 1.26 |

| spread | 1 | 1.16 | 1.15 | 1.21 | |

| Lettuce ‘Outredgeous’ | single | 1 | 1.10 | 1.16 | 1.25 |

| spread | 1 | 1.11 | 1.28 | 1.35 | |

| Lettuce ‘Othilie’ | single | 1 | 0.86 | 0.87 | 0.98 |

| spread | 1 | 1.04 | 1.16 | 1.21 | |

| Red mustard ‘Frizzy lizzy’ | single | 1 | 0.70 | 1.32 | 1.18 |

| spread | 1 | 1.49 | 1.10 | 1.89 | |

| Rocket ‘Rucola cultivated’ | single | 1 | 0.94 | 0.93 | 0.72 |

| spread | 1 | 1.15 | 0.83 | 0.91 | |

| Swiss chard ‘Ruby red’ | single | 1 | 1.09 | 1.11 | 1.15 |

| spread | 1 | 1.09 | 0.86 | 0.99 | |

| Spinach ‘Golden eye’ | single | 1 | 1.20 | 1.09 | 0.98 |

| spread | 1 | 0.93 | 1.23 | 1.11 | |

Fig. 2.

Lettuce grown at different light intensities (6 weeks after sowing) showing more compact plants and stiffer leaves at high light intensities.

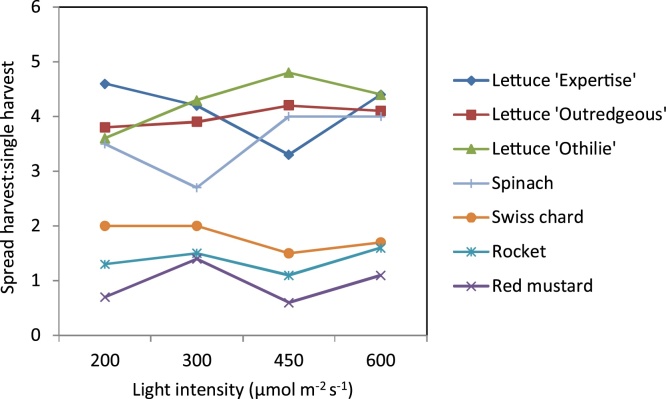

Spread harvesting resulted in an increased production by a factor 3–4 for the lettuce cultivars and spinach, and a factor 1–2 for Swiss chard, red mustard and rocket (Fig. 3). When spread harvesting was performed on the lettuce cultivars, much more fresh biomass was realised than single harvests: 286, 224 and 209 g m−2 per day on average over 6 weeks for spread harvesting compared to 71, 56 and 49 g m−2 per day in single harvests for ‘Expertise’, ‘Outredgeous’ and ‘Othilie’ respectively.

Fig. 3.

Ratio of biomass production of 7 vegetable crops following spread harvest relative to production following single harvest.

As it could be inferred from our observations on the effect of light intensity on the texture of leaves, dry matter content of the shoots increased with light intensity (Table 5), something also observed by Blom-Zandstra et al. (1988) and Kitaya et al. (1998) for lettuce. The dry matter content of lettuce and spinach applying spread harvest was lower compared to plants harvest after 6 weeks (single harvest). By weekly harvesting the oldest leaves (spread harvest), the remaining leaves of the plants were relatively young, which have a lower dry matter content compared to older leaves. (The dry matter content of ‘Expertise’ measured 4 weeks after sowing was on average 5.4% for the 4 light intensities – data not presented - and 7.6% 6 weeks after sowing; Table 5). This was not observed for red mustard, rocket and Swiss chard (Table 5).

Table 5.

Dry matter content (%) of the shoots of lettuce ‘Expertise’, ‘Outredgeous’ and ‘Othilie’), red mustard ‘Frizzy lizzy’, rocket ‘Rucola cultivated’, Swiss chard ‘Red ruby’, spinach ‘Golden eye’ grown under various light intensities and harvested during (spread harvest) or at the end of 42 days cultivation (single harvest). Means of lettuce are based on 6 (single harvest) and 20 (spread harvest) replicates; red mustard, rocket and Swiss chard on 20 replicates; spinach on 10 replicates.

| Dry matter content (%) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Light (μmol m−2 s−1) | 200 | 300 | 450 | 600 | ||

| Crop | Harvest | Density (m−2) | ||||

| Lettuce ‘Expertise’ | single | 25 | 6.7 | 6.9 | 7.6 | 9.1 |

| spread | 123 | 4.9 | 5.3 | 5.9 | 7.1 | |

| Lettuce ‘Outredgeous’ | single | 25 | 7.0 | 7.5 | 8.9 | 10.0 |

| spread | 123 | 5.7 | 6.0 | 6.4 | 7.3 | |

| Lettuce ‘Othilie’ | single | 25 | 5.8 | 6.8 | 7.2 | 8.4 |

| spread | 123 | 4.6 | 5.1 | 5.5 | 6.3 | |

| Red mustard ‘Frizzy lizzy’ | single | 625 | 5.4 | 5.3 | 6.1 | 5.9 |

| spread | 625 | 6.0 | 6.1 | 7.4 | 7.1 | |

| Rocket ‘Rucola cultivated’ | single | 333 | 8.8 | 10.4 | 17.8 | 17.4 |

| spread | 625 | 9.0 | 11.8 | 12.1 | 11.1 | |

| Swiss chard ‘Ruby red’ | single | 295 | 7.8 | 9.4 | 11.8 | 11.2 |

| spread | 625 | 8.7 | 9.6 | 12.1 | 12.0 | |

| Spinach ‘Golden eye’ | single | 156 | 17.3 | 18.5 | 22.5 | 22.6 |

| spread | 625 | 11.8 | 13.5 | 15.9 | 12.0 | |

The smaller 2 crops, radish and chives, were only harvested once when ready for consumption. Increasing the light intensity from 200 to 600 μmol m−2 s−1 resulted in considerable increase in fresh biomass production, a factor 1.7 for radish (Table 6) and 1.5 for chives. In the case of radish, this included both the tap root (1.8 times) and leaf biomass (1.5 times). The tap root diameter desired by breeders and growers at harvest was realised as well, varying from 2.2 cm at 200 μmol m−2 s−1 to 2.8 cm at 600 μmol m−2 s−1.

Table 6.

Mean biomass production (kg FW m−2 ± SE) of radish ‘Lennox’ and chives ‘Staro’ harvested after 28, resp. 42 days, grown under various light intensities. Means are based on 15 (radish) and 20 (chives) replicates.

| Mean biomass production (kg FW m−2 ± SE) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Light (μmol m−2 s−1) | 200 | 300 | 450 | 600 | ||

| Crop | Harvest | Density (m−2) | ||||

| Radish | leaf | 278 | 0.70 ± 0.07 | 0.90 ± 0.14 | 0.77 ± 0.08 | 1.03 ± 0.13 |

| tap root | 278 | 2.03 ± 0.38 | 2.67 ± 0.49 | 2.66 ± 0.37 | 3.67 ± 0.60 | |

| Chives | leaf | 1875 | 1.47 ± 0.09 | 1.18 ± 0.07 | 1.79 ± 0.14 | 2.17 ± 0.12 |

A short additional experiment was performed to assess the regrowth potential of chives. Blocks with chives cultivated under 200–600 μmol m−2 s−1 for 42 days were harvested and then placed under a light intensity of 300 μmol m−2 s−1 for an additional 8 days. The effect of a high light intensity during the initial growth period on regrowth was large (Fig. 4). Plants initially grown at 200 μmol m−2 s−1 produced 90 g m−2 fresh leaves during regrowth and 441 g m−2 after initial growth at 600 μmol m−2 s−1. This suggests that at the higher light intensity during the initial growth phase more light was invested in the growth of the bulb which then was used for the regrowth of new shoots.

Fig. 4.

Regrowth chives at 300 μmol m−2 s−1 for 8 days after initially being cultivated at 200, 300, 450 and 600 μmol m−2 s−1 for 6 weeks. Data are expressed in gram fresh weight m−2. Means are based on 20 replicates.

3.2. Influence of light intensity and temperature

3.2.1. Leafy greens

The production and regrowth of leafy green vegetables is presented in Table 7. Harvesting of the outer leaves of lettuce ‘Expertise’ began 5 weeks after sowing and continued for another 6 weeks. Lettuce yielded on average ca. 200 g fresh leaves per m2 daily from sowing to the end of the cultivation period (spread harvest) and 350–400 g per m2 daily during the period of harvesting (spread harvest started 5 weeks after sowing). When the trial was terminated, growing plants were still present, and were harvested (‘remainder’), yielding another 8–9 kg m−2. A higher temperature of 25 °C did not improve the fresh shoot biomass production of lettuce ‘Expertise’ compared to 21 °C. At both temperatures at 600 μmol m−2 s−1, the leaves were observed to be harder and less palatable, qualitatively less than at 300 μmol m−2 s−1. Most dry matter was produced at 25 °C and 600 μmol m−2 s−1 (1.33 kg m−2 total), indicating a higher dry matter content of lettuce grown at 600 μmol m−2 s−1 compared to 300 μmol m−2 s−1 at both temperatures.

Table 7.

Mean shoot biomass production (kg m−2 FW and DW ± SE) of lettuce ‘Expertise’, red mustard ‘Frizzy lizzy’ and rocket ‘Rucola cultivated’ grown at 2 temperatures under 2 light intensities. Lettuce leaves were regularly harvested during 11 weeks of cultivation (spread harvest), followed by harvesting the remainder at the end of the cultivation period; red mustard and rocket were harvested after 26 and 27 days (single harvest), and then again after 14 days regrowth. Means are based on 20 replicates.

| FW/DW | Mean shoot biomass production (kg m−2 ± SE) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day/night temperature |

21/19 °C |

25/23 °C |

||||

| Light (μmol m−2 s-1) |

300 | 600 | 300 | 600 | ||

| Crop | Harvest | |||||

| FW | Lettuce | Spread | 16.64 ± 1.33 | 12.41 ± 1.22 | 14.60 ± 1.67 | 13.83 ± 0.96 |

| Remainder | 8.57 ± 0.61 | 8.26 ± 0.58 | 8.86 ± 0.78 | 9.15 ± 0.27 | ||

| Total | 25.21 ± 1.90 | 20.67 ± 1.73 | 23.46 ± 2.37 | 22.98 ± 1.13 | ||

| Red mustard | Single | 7.14 ± 0.69 | 9.95 ± 0.34 | 9.75 ± 0.73 | 12.20 ± 0.67 | |

| Regrowth | 2.95 ± 0.66 | 4.75 ± 1.06 | 4.16 ± 0.93 | 4.85 ± 1.09 | ||

| Rocket | Single | 2.80 ± 0.19 | 3.09 ± 0.25 | 3.40 ± 0.33 | 3.28 ± 0.67 | |

| Regrowth | 1.19 ± 0.27 | 0.76 ± 0.17 | 0.54 ± 0.12 | 0.80 ± 0.18 | ||

| DW | Lettuce | Spread | 0.84 ± 0.07 | 0.75 ± 0.08 | 0.71 ± 0.08 | 0.85 ± 0.07 |

| Remainder | 0.43 ± 0.03 | 0.51 ± 0.04 | 0.47 ± 0.04 | 0.56 ± 0.02 | ||

| Total | 1.27 ± 0.10 | 1.27 ± 0.12 | 1.18 ± 0.11 | 1.33 ± 0.08 | ||

| Red mustard | Single | 0.39 ± 0.03 | 0.50 ± 0.04 | 0.46 ± 0.05 | 0.66 ± 0.06 | |

| Rocket | Single | 0.28 ± 0.02 | 0.48 ± 0.04 | 0.37 ± 0.04 | 0.59 ± 0.05 | |

Red mustard reacted positively to the high light intensity and produced ca. 1.4 times more fresh shoot biomass under 600 than under 300 μmol m−2 s−1 at the first harvest and ca. 1.6 times more after another 2 weeks of regrowth at 21 °C (Table 7). The initial production of red mustard was higher at 25 °C than at 21 °C, but resulted in a poorer quality. Overall, red mustard plants with the best appearance were observed under the low light, low temperature and high light, high temperature conditions. A higher temperature of 25 °C increased the fresh shoot biomass of rocket (1.1 times, averaged for both light intensities), but regrowth was less (0.7 times). The effect of high light intensity on fresh biomass production of rocket was only observed at 21 °C (1.1 times) but not at 25 °C (0.96 times).

Light intensity positively affects shoot dry weight of both species at both temperatures. For red mustard the shoot dry weight was increased 1.3 and 1.4 times (respectively at 21 °C and 25 °C) under 600 μmol m−2 s−1 compared to 300 μmol m−2 s−1. For rocket the shoot dry weight is increased 1.7 and 1.6 times (respectively at 21 °C and 25 °C) under 600 μmol m−2 s−1 compared to 300 μmol m−2 s−1. The different effects of light intensity on fresh weight and dry weight indicate that dry matter content was increased at a higher light intensity.

3.2.2. Radish

The tap root of radish is the more important product of this ready-to-eat vegetable, even though the leaves are edible as well. Radish was planted at a density of 625 plants m−2, but after 3 weeks became too crowded and plants were spaced to a final density of 278 plants m−2 for the last week prior to harvesting. Both the diameter as well as the biomass production of the tap root increased under the higher light intensity and in absolute terms the most at 21 °C (Table 8). More leaf biomass was produced at 25 °C compared to 21 °C for 300 μmol m−2 s−1 (10%) and for 600 μmol m−2 s−1 (28%).

Table 8.

Mean biomass production (kg m−2 FW ± SE) and tap root diameter (mm) of radish (Lennox) grown at 2 temperatures under 2 light intensities. Radish was harvested after 28 days cultivation. Means are based on 20 replicates.

| Mean biomass production and tap root diameter |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day/night temperature | 21/19 °C |

25/23 °C |

||

| Light (μmol m−2 s-1) | 300 | 600 | 300 | 600 |

| Leaf FW (kg m−2) | 1.64 ± 0.10 | 1.51 ± 0.11 | 1.81 ± 0.12 | 1.94 ± 0.16 |

| Tap root FW (kg m−2) | 2.90 ± 0.31 | 4.17 ± 0.47 | 2.31 ± 0.28 | 3.67 ± 0.41 |

| Tap root diameter (mm) | 26.3 ± 1.2 | 30.4 ± 1.2 | 23.7 ± 1.4 | 29.2 ± 1.3 |

3.2.3. Herbs

Both chives and parsley were harvested for the first time after 42 days cultivation, followed by regrowth harvests after another 28, then 27, then 22 days. Thus the total cultivation period was 119 days and included 4 harvests. The growth of chives at 600 μmol m−2 s−1 was higher at 25°/23 °C than 21°/19 °C, with more tillering and a healthy root system. At the lower light intensity, parts of the root system died of after the initial harvest, which had a large influence on regrowth (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Cumulative shoot biomass production (kg m−2 FW ± SE) during 119 days of chives ‘Purly’ and parsley ‘Frise vert Fonce-Rina’ grown at 2 temperatures under 2 light intensities. Open symbols indicate production at 600 μmol m−2 s−1, closed symbols indicate production at 300 μmol m−2 s−1. Means are based on 20 replicates.

Parsley grew more rapidly at 21 °C than at 25 °C, producing ca. 17 kg fresh parsley per m2 compared to ca. 10 kg per m2 at 25 °C. At the higher temperature the initial harvest yielded more biomass, but regrowth was poorer as parts of the root system died off after initial harvesting. The light intensity had no significant influence on the growth rate of parsley at either temperature.

3.2.4. Fruit vegetables

Fruiting vegetables like tomato and cucumber generally require a longer cultivation period before harvesting than leafy greens. Although the results presented in Table 9 are averaged over the whole cultivation period, the fruits of tomato and cucumber were only harvested during the last 55 (tomato) and 74 (cucumber) days before the experiment was terminated. The determinate dwarf tomato ‘F1 2414’ yielded more in terms of fresh weight biomass (15%) and fruit numbers (9%) at 600 compared to 300 μmol m−2 s−1. The harvest index (HI) or proportion of edible biomass was 64% and 65% under the 2 light treatments. Although the individual fruit weight and dry matter content at both light intensities was very similar, proportion of dry matter allocated to the fruits was ca. 2.5% higher at 600 μmol m2 s−1 (Table 9).

Table 9.

Mean production parameters of tomato (F1 2414) and cucumber (Quarto) grown under 2 light intensities at a day/night temperature of 25/23 °C. Both fruit vegetable crops were destructively harvested after 116 days cultivation. Means are based on 4 and 6 replicates for tomato and cucumber respectively.

| Mean production parameters |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Light (μmol m−2 s−1) | 300 | 600 | |

| Crop | Parameters | ||

| Tomato | Fruit production (kg m−2) | 10.43 ± 1.00 | 12.00 ± 0.86 |

| Number of fruits (per m2) | 1867 ± 207 | 2038 ± 182 | |

| Fruit weight (g fruit−1) | 5.8 ± 0.2 | 5.7 ± 0.2 | |

| DMC fruits (%) | 9.1 ± 0.3 | 9.0 ± 0.4 | |

| Total plant biomass (kg FW m−2) | 19.38 ± 1.61 | 20.38 ± 0.60 | |

| DM fruit/(DM plant + fruit) (%) | 63.7 ± 1.5 | 65.3 ± 1.0 | |

| Cucumber | Fruit production (kg m−2) | 23.13 ± 1.49 | 25.09 ± 2.12 |

| Number of fruits (per m2) | 239 ± 12 | 223 ± 5 | |

| Fruit weight (g fruit−1) | 96.4 ± 2.8 | 118.1 ± 5.4 | |

| DMC fruits (%) | 2.8 ± 0.2 | 2.9 ± 0.1 | |

| Total plant biomass (kg FW m−2) | 29.15 ± 1.81 | 37.88 ± 1.77 | |

| DM fruit/(DM plant + fruit) (%) | 53.8 ± 2.9 | 40.1 ± 3.0 | |

The effect of light intensity on cucumber production differed to that of tomato, in that while 8% more fruit biomass was produced at 600 μmol m−2 s−1, the number of fruits decreased indicating that the individual fruit weight rose, in this case by more than 22%. The HI for cucumber was much higher at 300 (54%) than at 600 μmol m−2 s−1 (40%) respectively. Here too, production was calculated over the whole cultivation period, while the actual harvesting occurred during the last 74 days prior to termination of the experiment.

4. Discussion

The aim of the research is to realise maximum food production as efficiently as possible (space and energy are limiting factors) by determining the marginal value of light and temperature in terms of fresh yield, and to collect suitable information for crop management planning that maximises productivity.

Because crops vary in their intrinsic light use efficiency and ability to convert light to edible plant biomass, a number of experiments was performed to investigate the influence of LED lighting on plant growth and production on a number of fresh food vegetables. The effect of increasing the light intensity from 200 μmol m−2 s−1 up to 600 μmol m−2 s−1 on food production at a given plant density was not large, generally varying from a factor 0.7–1.9 compared to that at 200 μmol m−2 s−1 (Table 4). Therefore, in order to increase the LUE, some crops were planted at a much higher density and were partially harvested at regular intervals (spread harvest), as manipulation of plant spacing is known to increase light interception and its efficient use in any crop (cf. Papadopoulos and Pararajasingham, 1997). Spread harvesting was begun when plants were at their maximum growth rate in their exponential growth phase and began to touch each other. From then on, 2–3 leaves of the leafy green vegetables were harvested weekly, depending on their growth rate. Calculated per unit area, the amount of fresh food thus produced increased dramatically (a factor between 2 and 4) compared to that in single harvesting. The fresh food production at the South Pole Food Growth Chamber (Patterson et al., 2012) was harvested similarly to the single harvesting in this study, but the production was lower. The production realised in this study is a factor 2–6 higher for lettuce, twice as high for cucumber and more than 10 times higher for tomato. Increasing plant density thus increased crop light use efficiency, as more light was absorbed by the crop, which increased the total photosynthesis at crop level (per unit area), and thus the crop production (Mao et al., 2014). Another reason for the high production is partial harvesting in time. Even though this spread harvesting is realised at the cost of crew member time (another scarce resource), it should be taken into serious consideration, as the resulting food production is at least twice as high, and working hands-on with the plants may well have a positive influence on crew member’s well-being (Koga & Iwasaki, 2013; Lewis, 1994). At the end, it boils down to striking the right expenditure balance among the resources labour; seed; space and electricity.

Even though spread harvesting was applied, the influence of increasing the light intensity to 600 μmol m−2 s−1 remained only marginally higher than that for single harvests at 200 μmol m−2 s−1, a factor 0.83–1.89. Accepted horticultural wisdom is that increasing available light should increase biomass (Marcelis et al., 2006). The fact that this did not happen here suggests that other factors (rather than light) may have been limiting productivity.

The aim of course is to maximise the energy efficiency at a given plant distribution and the contribution and balance of (less) light and temperature should be considered. The temperature conditions in the MTF will have to be the same for all crops. Thus, at a given temperature, the amount of light given will have the largest influence on crop growth and production. In searching for a good balance between light and temperature, 4 of the vegetable crops and 2 herbs were grown at a lower (21/19° day/night) and higher (25/23 °C day/night) temperature. In general, a higher fresh weight biomass for red mustard (1.3 times) and rocket (1.1 times) and a lower biomass for radish (0.8 times) was observed at the higher temperature (values averaged 300 and 600 μmol m−2 s−1), while no difference was observed for lettuce (Tables 7 and 8). The roots of herbs on the other hand, appeared to have suffered from the higher temperature during regrowth. To cultivate all crops in the same unit the regime of 21/19 °C is more productive compared to 25/23 °C. From an energetic point of view it is more profitable to maintain higher temperatures during lighting and lower temperatures during darkness in the MTF in Antarctica because the lamps will provide heat. As crops react on an average temperature (so called ‘temperature integration’, de Koning et al., 1990), a temperature regime of 23/17° (with an average of 20 °C, like 21/19 °C) will be energetically beneficial.

The production of lettuce was very high at 118 k m2 yr−1 (25 kg m2 11 weeks−1 in the experiment; Table 7) compared to commercial cultivation without supplemental lighting (35 kg m2 yr−1) observed in The Netherlands (Anon., 2012). Doubling the light intensity from 300 to 600 μmol m−2 s−1 and thus the amount of energy used for lighting, resulted in ca. 20% less fresh biomass production by lettuce at 21 °C, while it increased the production of the other 3 vegetables by 10–45% (Table 7, Table 8). The overall cost of energy was higher than its benefit, so this might be an argument for cultivation a lower light intensity, saving valuable energy, not only for lighting but for cooling and dehumidification as well, in the MTF (Graamans et al. 2017). For lettuce, the quality reduced at 600 μmol m−2 s−1, which is an important argument to cultivate at a lower light intensity of 300 μmol m−2 s−1. It is possible to use different light intensities on every single tray in the MTF in order to increase the production of a small selected number of crops. So the positive effect of 600 μmol m−2 s−1 on the yield of radish and the initial yield of chives can be worthwhile the costs of more electricity of the lamps providing a higher light intensity. Regrowth of chives, initially grown at 600 μmol m−2 s−1, can also be conducted at a lower light intensity of 300 μmol m−2 s−1 (Fig. 3), which saves energy.

In a separate cultivation trial, the fruiting vegetables, determinate tomato and cucumber, were grown at the higher temperature regime common conditions for both, under 300 and 600 μmol m−2 s−1. The first fruits were ripe 9 (tomato) and 6 (cucumber) weeks after sowing, and were harvested for another 8 and 11 weeks resp., after which the experiment was terminated. The influence of doubling the light intensity on production was 15% and 8% resp., so for these fruiting vegetables, the added value of doubling the light energy input for total production and the harvest index is questionable.

In these trials, cucumber was harvested twice weekly, resulting in heavier fruits and a larger sink strength. This may well have resulted in increasing fruit abortion. Daily harvesting will thus likely reduce flower abortion and increase the number of fruits.

With the data generated from this study and the available shelf space in the MTF, some cautious estimates can be made of the amount of fresh food that can be produced. A part of the 9.6 m2 cultivation area, approximately 40%, will likely be taken up by crops in their juvenile or vegetative stage. That would allow for ca. 6 m2 available as production area. The results shown in this study indicate that, given the conditions and crop management used, 4 kg m−2 of lettuce can be harvested weekly (21 °C, 300 μmol m−2 s−1, spread harvest), 1.4 kg m−2 radish (21 °C, 600 μmol m−2 s−1), 1.3 kg m−2 of tomato, 2.2 kg m−2 of cucumber (25 °C, 300 μmol m−2 s−1), with the other leafy greens yielding 1.2 kg m−2 (21 °C, 300 μmol m−2 s−1) and herbs 150 g m−2 week−1 (21 °C, 300 μmol m−2 s−1) and 1 kg m−2 week−1 including regrowth.

With these data it will be possible for crew members to plan their fresh food production, starting with a sowing scheme, in order to realise a more or less constant and varied flow of fresh food. Each crop has its own germination time, days to first harvest and days to final harvest. With these data available, the fresh food diet for a longer period of time can be established and put into practice.

5. Conclusions

Crop growing and management recipes were developed to maximise productivity of energy and space. Different light, temperature and cultivation (spread harvest) regimes were tested and edible yield was determined. To choose one temperature regime for the whole MTF, the performance of all crops – in terms of yield and quality - should be taken in consideration. Higher temperatures of 25/23 °C increased production of some crops, but regrowth of herbs lagged behind. All crops performed well at a regime of 21/19 °C and at a light intensity of 300 μmol m−2 s−1, with a few like radish, red mustard and chives and to a lesser extent, lettuce and red mustard, growing more rapidly at light intensities up to 600 μmol m−2 s−1. However, the quality of lettuce at 600 μmol m−2 s−1 deteriorated. Light intensity can be chosen per each single tray and makes the cultivation in the MTF flexible per crop and cultivation cycle.

Increasing the plant density increases the light use efficiency and applying spread harvesting increases fresh food production. Increasing plant density is only possible in combination with spread harvesting, and this combination results is a higher biomass production, but at the cost of extra work by crew members and the availability of seeds. The crew’s desire for the maximum amount of fresh food, given the additional effort (work), will likely reflect its importance (psychological effect) on the crew.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported jointly by the EU-H2020 project "Ground Demonstration of Plant Cultivation Technologies and Operation in Space for Safe Food Production on-board ISS and Future Human Space Exploration Vehicles and Planetary Outposts" (EDEN-ISS, grant 636501) and by the Dutch Top Sector Tuinbouw & Uitgangsmaterialen (EU-2016-01). However, no endorsement from the European Commission nor the Dutch Ministry of Economy of the results and conclusions is hereby implied. The authors are grateful to Gerrit Stunnenberg for the preparing the climate rooms and care of the experiments and Willem de Visser, Paul Zabel (DLR) and Johan Steenhuizen for assisting with harvesting. We also thank plant breeders John Verbruggen and Marc Celis (Rijk Zwaan), Jan van Heijst (Vreugdenhil) and Gerard Janssen (Bayer) for their advice before and during plant cultivation.

References

- Anon . In: Quantitative Information for Horticulture 2012-2013 (in Dutch) Vermeulen P.C.M., editor. Wageningen Greenhouse Horticulture; Wageningen: 2012. Report GBT 5032. [Google Scholar]

- Blom-Zandstra M., Lampe J.E.M., Ammerlaan F.H.M. C and N utilization of two lettuce genotypes during growth under non-varying light conditions and after changing the light intensity. Physiol. Plant. 1988;74:147–153. [Google Scholar]

- Chunxiao X., Hong L. Crop candidates for the biogenerative life support systems in China. Acta Astronaut. 2008;63:1076–1080. [Google Scholar]

- Cocetta G., Casciani D., Bulgari R., Musante F., Kolton A., Rossi M., Ferrante A. Light use efficiency for vegetables production in protected and indoor environments. Eur. Phys. J. Plus. 2017;132(43) 15p. [Google Scholar]

- Dueck T., Kempkes F., Meinen E., Stanghellini C. Choosing crops for cultivation in spaceVienna, Austria. ICES-2016-206, 46th Intern. Conf. Environ. Systems, July 10-14, 2016. 2016 8p. [Google Scholar]

- Graamans L., Dobbelsteen A., van den, Meinen E., Stanghellini C. Plant factories: crop transpiration and energy balance. Agric. Syst. 2017;153:138–147. [Google Scholar]

- Hoff J.E., Howe J.M., Mitchell C.A. NASA Contractor Report 166324, 1982. 1982. Nutritional and cultural aspects of plant species selection for a controlled ecological life support system. 122p. [Google Scholar]

- Holmes M.G., Smith H. The function of phytochrome in the natural environment. I. Characterisation of daylight for studies in photomorphogenesis and photoperiodism. Photochem. Plant Biol. 1977;25:533–538. [Google Scholar]

- Kitaya Y., Niu G., Kozai T., Ohashi M. Photosynthetic photon flux, photoperiod, and CO2 concentration affect growth and morphology of lettuce plug transplants. HortScience. 1998;33(6):988–991. [Google Scholar]

- Koga K., Iwasaki Y. Psychological and physiological effect in humans of touching plant foliage-using the semantic differential method and cerebral activity as indicators. J. Physiol. Anthropol. 2013;32:7. doi: 10.1186/1880-6805-32-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Koning A. Long-term temperature integration of tomato. Growth and development un der alternating temperature regimes. Sci. Hortic. 1990;45(1–2):117–127. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis C. Human health and well-being: the psychological, physiological, and sociological effects of plants on people. Hortic. Hum. Life Culture Environ. 1994;391:31–40. [Google Scholar]

- Lin K.-H., Huan M.-Y., Huan W.-D., Hsu M.-H., Yang Z.-W., Yang C.-M. The effects of red, blue and white light-emitting diodes on the growth, development and edible quality of hydroponically grown lettuce (Lactuca sativa L. var. capitata) Sci. Hortic. 2013;150:86–91. [Google Scholar]

- Mao L., Zhang L., Zhao X., Liu S., Van der Werf W., Zhang S., Spiertz H., Li Z. Crop growth, light utilization and yield of relay intercropped cotton as affected by plant density and a plant growth regulator. Field Crops Res. 2014;155:67–76. [Google Scholar]

- Marcelis L.F.M., Broekhuijsen A.G.M., Nijs E.M.F.M., Raaphorst M.G.M. Quantification of the growth response of light quantity of greenhouse grown crops. Acta Hortic. 2006;711:97–103. [Google Scholar]

- Massa G.D., Wheeler R.M., Stutte G.W., Richards J.T., Spencer L.E., Hummerick M.E., Douglas G.L., Sirmons T. Selection of leafy green vegetable varieties for a pick-and-eat diet supplement on ISS Bellevue, Washington. ICES-2015-252. 45th Intern. Conf. Environ. Systems. 2015 July 12-16, 2015. 16p. [Google Scholar]

- Massa G.D., Wheeler R.M., Morrow R.C., Levine H.G. Growth chambers on the International Space Station for large plants. Acta Hortic. 2016;1134:215–221. [Google Scholar]

- Mauerer M., Schubert D., Zabel P., Bamsey M., Kohlberg E., Mengedoht D. Initial survey on fresh fruit and vegetable preferences of Neumayer Station crew members: input to crop selection and psychological benifits of space-based plant production systems. Open Agric. 2016;1(1):179–188. [Google Scholar]

- Mazza C.A., Ballaré C.L. Photoreceptors UVR8 and phytochrome B cooperate to optimize plant growth and defense in patchy canopies. New Phytol. 2015;207:4–9. doi: 10.1111/nph.13332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCree K.J. The action spectrum, absorptance and quantum yield of photosynthesis in crop plants. Agric. Meteorol. 1972;9:191–216. [Google Scholar]

- Odeh R., Guy C.L. Gardening for therapeutic people-plant interactions during long-duration space missions. Open Agric. 2017;2:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Papadopoulos A.P., Pararajasingham S. The influence of plant spacing on light interception and use in greenhouse tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum Mill.): a review. Sci. Hortic. 1997;69:1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Paradiso R., Meinen E., Snel J.F.H., Visser P., de, Ieperen W., van, Hogewoning S.W., Marcelis L.F.M. Spectral depen dence of photosynthesis and light absorptance of single leaves and canopy in rose. Sci. Hortic. 2011;127:548–554. [Google Scholar]

- Park Y., Runkle E.S. Far-red radiation promotes growth of seedlings by increasing leaf expansion and whole-plant net assimilation. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2017;136:41–49. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson R.L., Giacomelli G.A., Kacira M., Sadler P.D., Wheeler R.M. Description, operation and production of the South Pole food growth chamber. Acta Hortic. 2012;952:589–596. [Google Scholar]

- Poulet L., Massa G.D., Morrow R.C., Bourget C.M., Wheeler R.M., Mitchell C.A. Significant reduction in energy for plant-growth lighting in space using targeted LED lighting and spectral manipulation. Life Sci. Space Res. 2014;2:43–53. [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler R.M. Horticulture for Mars. Acta Hortic. 2004;642:201–215. [Google Scholar]

- Zabel P., Bamsey M., Zeidler C., Vrakking V., Schubert D., Romberg O., Boscheri G., Dueck T. The preliminary design of the EDEN ISS mobile test facility – an Antarctic greenhouse Vienna, Austria. ICES-2016-198, 46th Intern. Conf. Environ. Systems, July 10-14, 2016. 2016 20 p. [Google Scholar]