Abstract

Aims/hypothesis

We identified a mouse with a point mutation (Y12STOP) in the KCNJ11 subunit of the KATP channel that is identical to that found in a patient with congenital hyperinsulinism of infancy (HI). We aimed to characterise the phenotype arising from this loss-of-function mutation and to compare it to that of other mouse models and patients with HI.

Methods

An N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea (ENU) induced mutation on a C3H/HeH background (Kcnj11Y12STOP) was phenotyped using intraperitoneal glucose tolerance testing measuring both glucose and insulin plasma concentrations. Insulin secretion and response to incretins was measured on isolated islets.

Results

Homozygous male and female adult Kcnj11Y12STOP mice exhibit impaired glucose tolerance and a defect in insulin secretion measured both in vivo and in vitro. Islets had an impaired incretin response and reduced insulin content.

Conclusions/interpretation

The phenotype of homozygous Kcnj11Y12STOP mice is consistent with that of other Kcnj11 knockout mouse models. In contrast to the patient carrying this mutation homozygously, we did not observe hyperinsulinaemia or hypoglycaemia. It has been reported that HI patients may develop diabetes and our mouse model may reflect this clinical feature. The Kcnj11Y12STOP model may thus be useful in further studies of KATP channel function in various cell types and in the investigation of the development of hyperglycaemia in HI patients.

Keywords: ENU, Hyperinsulinism, KATP-Channel, Kcnj11, Kir6.2

Introduction

Inactivating mutations in the gene encoding Kir6.2 (KCNJ11) result in familial Hyperinsulinism of Infancy (HI). Conversely, activating KCNJ11 mutations cause neonatal diabetes mellitus [1].

Mouse models of HI have been generated by genetic deletion of Kcnj11, or expression of a dominant negative Kcnj11 transgene, in either the whole animal or specifically in the beta cell (reviewed [2]). Global knockout of Kcnj11 produced beta cell depolarization, an increase in basal [Ca2+]i, and a loss of insulin secretion in response to glucose or the KATP channel blocker tolbutamide [3]. Neonates exhibited a transient hypoglycaemia, consistent with predictions from studies on HI patients. Unexpectedly, adult mice exhibited mild glucose intolerance, due to an enhanced insulin sensitivity [3]. Interestingly, mice in which Kcnj11 was deleted heterozygously hypersecreted insulin and showed enhanced glucose tolerance as adults [4].

When a dominant negative Kcnj11 mutation (G132S) was targeted to the beta cell, neonatal mice exhibited high serum insulin and hypoglycaemia but developed severe diabetes (due to a loss of beta cell mass) as adults [5]. In contrast, mice carrying a different beta cell-specific dominant negative mutation (GYG132-134 to AAA; AAA-TG) exhibited hyperinsulinism as adults [6]; however, ~30% of their beta cells had normal KATP channel density. These results suggest that incomplete loss of beta cell KATP function in vivo leads to hyperinsulinism and a complete loss to eventual diabetes.

We identified a Kcnj11 tyrosine to stop codon (Kcnj11Y12STOP) mutation in an ENU mutagenised mouse. This mutation was also found homozygously in a patient exhibiting familial HI [7], and shown to abolish KATP channel activity when expressed heterologously. The patient was only 3.7 years old at the time of publication and was unresponsive to diazoxide (as expected if he lacked functional KATP channels). Thus, a near-total pancreatectomy was performed to control his hyperinsulinism [7]. Both the parents of the proband carried the mutation in the heterozygous state but were asymptomatic.

Methods

Animals

Mice were kept in accordance with U.K. Home Office welfare guidelines, project license restrictions and local ethical approval. Mice were supplied by MRC Harwell, Harwell Science and Innovation Campus, UK.

ENU genotype driven screen

The Harwell ENU-DNA archive was screened for mutations in the Kcnj11 as described previously [8]. Kcnj11Y12STOP animals were generated using frozen sperm samples from the BALB/c x C3H/HeH F1 founder and C3H/HeH eggs [8].

IPGTT and OGTT

Both IPGTT and OGTT tests were carried out according to the EMPReSS protocols for IPGTT and OGTT (http://empress.har.mrc.ac.uk) using 2g glucose/kg. Blood was collected under a local anaesthetic. Plasma insulin was assayed using Mercodia Ultra-sensitive ELISA kits. Plasma glucose was measured using an Analox Glucose Analyser GM9.

Insulin tolerance test (ITT)

Animals were fasted for 5h and a blood sample taken before interperitoneal injection of 1IU insulin per kg of mouse. Subsequent blood samples were taken at 15, 30, 45, 60 and 90 minutes.

Insulin secretion assay

Islets were isolated by liberase digestion and handpicking (for detailed protocol see ESM). Insulin secretion from isolated islets (5 islets/well) was measured during 1h static incubations. Each assay was carried out in triplicate.

Results

We identified a T36A mutation, resulting in a missense amino acid change from tyrosine to a stop at codon 12 (Y12STOP, Kcnj11Y12STOP) of the 390 amino acid protein. RNA was prepared from isolated islets and sequenced to confirm that the mutation is expressed (see Figure S1).

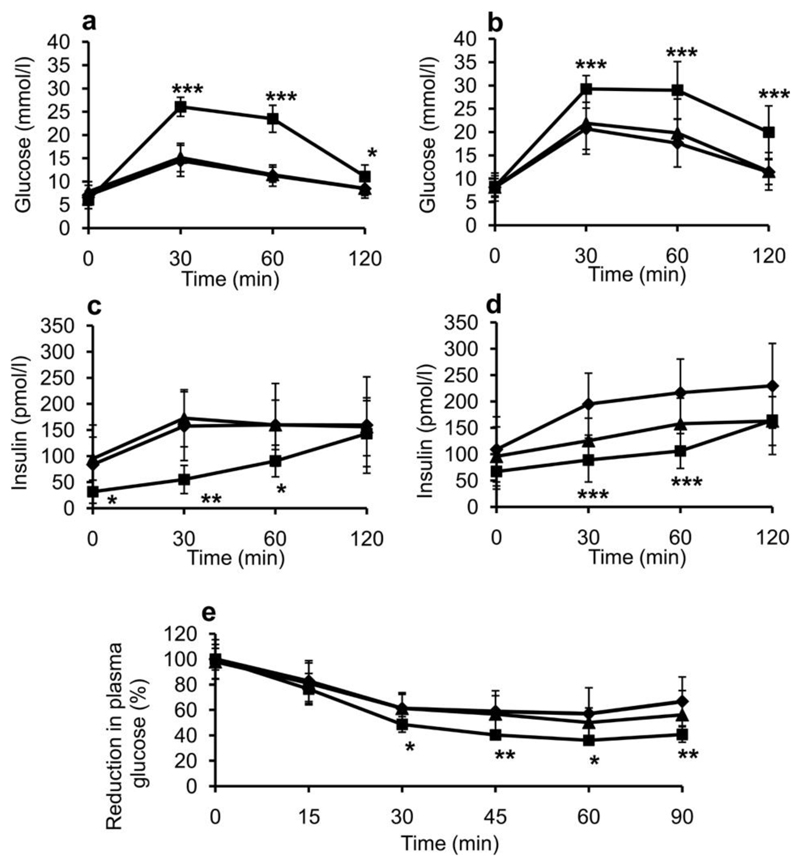

Kcnj11Y12STOP heterozygotes were indistinguishable from wildtype littermates in IPGTT’s at 12 and 20 weeks of age (Figure 1a, 1b, S2a and S2c). In contrast, glucose tolerance was strongly impaired in homozygous mutant mice (Figure 1 and S2). Similar results were observed in an OGTT (Figure S3). Homozygous Kcnj11Y12STOP mice secreted significantly less insulin during an IPGTT than either wildtype or heterozygous littermates at 12 and 20 weeks of age (Figure 1c, 1d, S2b and S2d). ITT’s showed that homozygous mice were relatively more insulin sensitive than wildtype or heterozygous mice (Figure 1e).

Figure 1. Impaired glucose tolerance and increased insulin sensitivity.

Glucose tolerance (a, b), insulin secretion (c, d) and insulin tolerance (e) in homozygous (hom, square line symbols), heterozygous (het, triangular line symbols) and wildtype littermate (wt, diamond line symbols) backcross three Kcnj11Y12STOP mice at 12 weeks of age. (a,c) Female mice, (b,d) Male mice. For (a),(b),(c) and (d) n=9 wt, n=16 het, n=7 hom. (e) Male 8-week mice, n= 12 wt, n=13 het, n=7 hom. Data are given as mean±SD. * = p<0.05, ** = p<0.01 and *** = p<0.001 for Student’s t-test when comparing hom to wt.

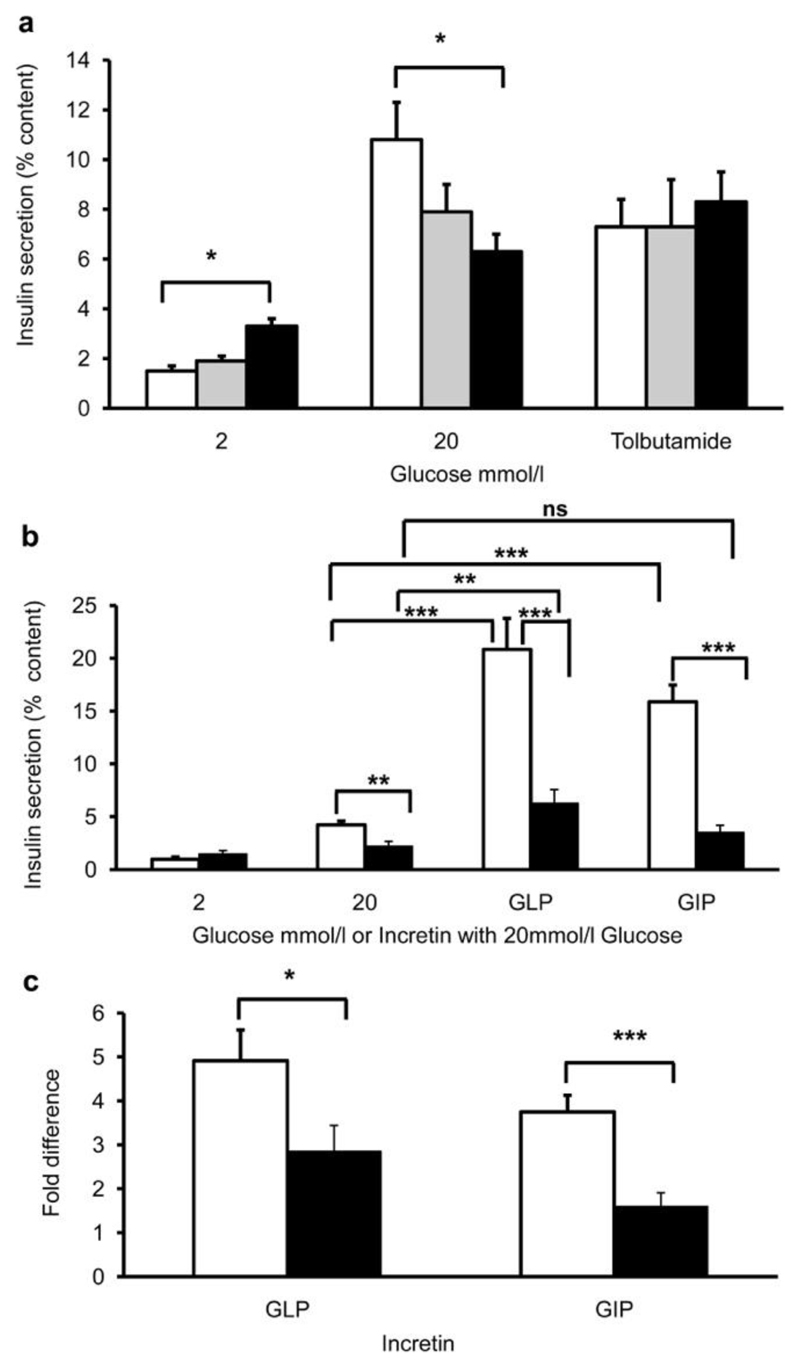

Insulin secretion was measured from islets isolated from 20-week old mice (Figure 2a). Homozygous islets showed significantly elevated basal insulin secretion (at 2mmol/l glucose) and secreted less insulin at 20mmol/l glucose compared with wildtype or heterozygous islets. Tolbutamide elicited similar insulin secretion in all groups of islets (Figure 2a).

Figure 2. Impaired insulin secretion and incretin response in islets isolated from wildtype, heterozygous or homozygous Kcnj11Y12STOP mice.

(a) Insulin secretion, expressed as a percentage of insulin content, in response to 2mmol/l glucose, 20mmol/l glucose or 100µmol/l tolbutamide plus 7mmol/l glucose for islets isolated from wildtype (white bars), heterozygous (grey bars) or homozygous (black bars) littermates. The data are the mean of three separate experiments (i.e. 3 mice), with 5 replicates (each of 5 islets) at each concentration. (b) Insulin secretion, as a percentage of content, in response to the incretins GLP-1 (5µM GLP-1 + 20mmol/l glucose) or GIP (10µM GIP + 20mmol/l glucose). The data represent the mean±SEM of 4 independent experiments from 4 animals per genotype (with 3-8 replicates of 5 islets per animal). (c) Fold increase in insulin secretion produced by 5µM GLP-1 or 10µM GIP (expressed as the amount of insulin secretion induced by 20mmol/l glucose plus the indicated incretin, divided by that produced by 20mmol/l glucose alone). White bars, wildtype islets. Black bars, homozygous islets. (a-c), * = p<0.05, ** = p<0.01, and *** = p<0.001 for Student’s t-test comparing wildtype to homozygote, or comparing the incretin response to the 20mmol/l glucose alone response (as indicated). ns, not significant.

In wildtype islets, addition of glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) or glucose-dependent insulinotropic peptide (GIP) further stimulated insulin secretion induced by 20mmol/l glucose, by 4.9-fold for GLP-1 and 3.7-fold for GIP (Figure 2b,c; white bars). Homozygous mutant islets showed a markedly impaired response compared to wildtype islets, the increase in insulin secretion being only 2.8-fold for GLP-1 and 1.59-fold for GIP (Figure 2b, c; black bars).

Insulin content was substantially lower in islets isolated from 13-week homozygous Kcnj11Y12STOP mice than in their wildtype littermates, whether measured by ELISA (Figure S4a) or by immunoblotting of islet proteins for insulin (Figure S4b). However, measurement of insulin gene transcription did not reveal any differences between genotypes (Figure S4c, d). No difference in islet area, was detected between wildtype (1.02% ± 0.08 SE, n=3 animals and 8 sections each) and homozygous mice (1.06% ± 0.07 SE, n=3 animals and 8 sections each) at 13 weeks of age. Similarly, immunohistochemistry on pancreas sections at 13 weeks of age showed a normal distribution of insulin (beta cell) and glucagon (alpha cell) staining cells (Figure S5). Further, staining with cleaved caspase-3 showed no evidence of significant apoptosis (Figure S5 and summarized in Table S1).

Discussion

Like the Kcnj11 knockout mice [3, 9], homozygous Kcnj11Y12STOP mice show impaired glucose tolerance in vivo, decreased insulin secretion from isolated islets and enhanced insulin sensitivity. Homozygous Kcnj11Y12STOP mice do not recapitulate the human phenotype of hyperinsulinism although they may be useful in understanding the transition to hyperglycaemia in some patients. Similar results have been reported for homozygous Kcnj11 and Sur1 KO mice [2, 10] and inactivating Kcnj11 mutations: they either show only neonatal hypoglycaemia or, at best, mild adult-onset hyperinsulinism - and a total loss of functional Kcnj11 causes hyperglycaemia.

The marked reduction in glucose tolerance in homozygous Kcnj11Y12STOP mice, manifest by lower insulin levels in vivo in response to a glucose challenge, occurred despite an enhanced insulin sensitivity. This suggested insulin secretion was impaired and this was confirmed by the reduced insulin secretory response of Kcnj11Y12STOP isolated islets. The lower insulin secretion results from both a marked reduction in insulin content (up to 50% in 13-week old islets) and impaired stimulus-secretion coupling.

The insulin content of Kcnj11 KO islets was not significantly different to that of islets isolated from 5-month old wildtype mice [9]. Interestingly, Sur1 KO islets have an insulin content of only about 60% that of wildtype [11]. The Kir6.2G132S dominant negative transgenic, which develops hyperglycaemia and hypoinsulinaemia, also shows substantially reduced insulin content between 4 and 16 weeks of age, although insulin content subsequently increases leading to some improvement in glucose tolerance [12].

The reason for the reduced insulin content of Kcnj11Y12STOP islets is unclear. As insulin mRNA levels were unchanged it cannot be the result of lower transcription. Hypersecretion under basal conditions, which could deplete insulin content, was observed in isolated islets (Figure 2a).

Our in vitro data demonstrate a clear impairment of the coupling between glucose metabolism and insulin secretion, because insulin secretion is lower in homozygous Kcnj11Y12STOP islets, when expressed as a percentage of insulin content. This may be related to the increased blood glucose levels, or to long-term elevation of intracellular calcium.

Studies of isolated Kcnj11Y12STOP islets showed a defective incretin response, consistent with Miki et al. (2005) who showed that Kcnj11 knockout islets had a marked reduction in the GLP-1 response and complete unresponsiveness to GIP [13]. Similarly, knockout of Sur1 also impairs the ability of incretins to potentiate glucose-stimulated insulin secretion [11]. It has been hypothesised that this reflects a failure of incretin-induced cAMP stimulation of insulin secretion by a PKA independent mechanism, which is likely to be mediated by Epac [14].

Some HI patients have mutations (homozygous or heterozygous) that result in partially functioning channels and respond to treatment with the KATP channel opener diazoxide or diet alone. Patients with such mutations may progress to diabetes in later life, perhaps reflecting a gradual decline of beta cell mass and insulin secretion like that seen in the AAA-TG mouse. Patients unresponsive to diazoxide are usually treated by partial pancreatectomy, and consequently many develop diabetes at puberty. These individuals often have severe null mutations that are similar in type to the knockout mouse mutations. It is not known if these patients would progress to diabetes if they were not pancreatectomised, as is found for the transgenic mouse models and humans with less severe mutations.

Our homozygous Kcnj11Y12STOP mouse carries the same mutation as that observed homozygously in a human patient [7]. This model may be a useful tool for studying null mutations of the Kir6.2/Kcnj11 gene and the transition from HI to diabetes and its treatment. Further this model will be of use for investigating the function of KATP channels in other cell types and tissues.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank the Mary Lyon Centre staff for their assistance in caring for the mice. We thank the Medical Research Council (AH and RDC), Wellcome Trust, Royal Society (Research Professorship to FMA) for personnel support, and the MRC, and Wellcome Trust for financing the research (RDC, FMA). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- ENU

N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea

- HI

Hyperinsulinism of Infancy

- IPGTT

Intraperitoneal Glucose Tolerance Test

- OGTT

Oral Glucose Tolerance Test

- ITT

Insulin Tolerance Test

- ESM

Electronic Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Duality of Interest

The authors declare that there is no duality of interest associated with this manuscript.

References

- [1].Ashcroft FM. ATP-sensitive potassium channelopathies: focus on insulin secretion. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:2047–2058. doi: 10.1172/JCI25495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Seino S, Iwanaga T, Nagashima K, Miki T. Diverse roles of K(ATP) channels learned from Kir6.2 genetically engineered mice. Diabetes. 2000;49:311–318. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.49.3.311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Miki T, Nagashima K, Tashiro F, et al. Defective insulin secretion and enhanced insulin action in KATP channel-deficient mice. PNAS. 1998;95:10402–10406. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.18.10402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Remedi MS, Rocheleau JV, Tong A, et al. Hyperinsulinism in mice with heterozygous loss of K(ATP) channels. Diabetologia. 2006;49:2368–2378. doi: 10.1007/s00125-006-0367-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Miki T, Tashiro F, Iwanaga T, et al. Abnormalities of pancreatic islets by targeted expression of a dominant-negative KATP channel. PNAS. 1997;94:11969–11973. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.22.11969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Koster JC, Remedi MS, Flagg TP, et al. Hyperinsulinism induced by targeted suppression of beta cell KATP channels. PNAS. 2002;99:16992–16997. doi: 10.1073/pnas.012479199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Nestorowicz A, Inagaki N, Gonoi T, et al. A nonsense mutation in the inward rectifier potassium channel gene, Kir6.2, is associated with familial hyperinsulinism. Diabetes. 1997;46:1743–1748. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.46.11.1743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Quwailid MM, Hugill A, Dear N, et al. A gene-driven ENU-based approach to generating an allelic series in any gene. Mammalian Genome. 2004;15:585–591. doi: 10.1007/s00335-004-2379-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Remedi MS, Koster JC, Markova K, et al. Diet-Induced Glucose Intolerance in Mice With Decreased {beta}-Cell ATP-Sensitive K+ Channels. Diabetes. 2004;53:3159–3167. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.12.3159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Seghers V, Nakazaki M, DeMayo F, Aguilar-Bryan L, Bryan J. Sur1 knockout mice. A model for K(ATP) channel-independent regulation of insulin secretion. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:9270–9277. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.13.9270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Nakazaki M, Crane A, Hu M, et al. cAMP-activated protein kinase-independent potentiation of insulin secretion by cAMP is impaired in SUR1 null islets. Diabetes. 2002;51:3440–3449. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.12.3440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Oyama K, Minami K, Ishizaki K, Fuse M, Miki T, Seino S. Spontaneous Recovery From Hyperglycemia by Regeneration of Pancreatic Î2-Cells in Kir6.2G132S Transgenic Mice. 2006:1930–1938. doi: 10.2337/db05-1459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Miki T, Minami K, Shinozaki H, et al. Distinct effects of glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide and glucagon-like peptide-1 on insulin secretion and gut motility. Diabetes. 2005;54:1056–1063. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.4.1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Kang G, Leech CA, Chepurny OG, Coetzee WA, Holz GG. Role of the cAMP sensor Epac as a determinant of KATP channel ATP sensitivity in human pancreatic beta-cells and rat INS-1 cells. J Physiol. 2008;586:1307–1319. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.143818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.