ARF8.4, an exitron (exonic intron)-retaining splice variant of AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR8, regulates stamen elongation and endothecium lignification via its temporal and tissue-specific expression.

Abstract

In addition to the full-length transcript ARF8.1, a splice variant (ARF8.2) of the auxin response factor gene ARF8 has been reported. Here, we identified an intron-retaining variant of ARF8.2, ARF8.4, whose translated product is imported into the nucleus and has tissue-specific localization in Arabidopsis thaliana. By inducibly expressing each variant in arf8-7 flowers, we show that ARF8.4 fully complements the short-stamen phenotype of the mutant and restores the expression of AUX/IAA19, encoding a key regulator of stamen elongation. By contrast, the expression of ARF8.2 and ARF8.1 had minor or no effects on arf8-7 stamen elongation and AUX/IAA19 expression. Coexpression of ARF8.2 and ARF8.4 in both the wild type and arf8-7 caused premature anther dehiscence: We show that ARF8.2 is responsible for increased expression of the jasmonic acid biosynthetic gene DAD1 and that ARF8.4 is responsible for premature endothecium lignification due to precocious expression of transcription factor gene MYB26. Finally, we show that ARF8.4 binds to specific auxin-related sequences in both the AUX/IAA19 and MYB26 promoters and activates their transcription more efficiently than ARF8.2. Our data suggest that ARF8.4 is a tissue-specific functional splice variant that controls filament elongation and endothecium lignification by directly regulating key genes involved in these processes.

INTRODUCTION

In Arabidopsis thaliana, stamen development consists of an early phase (stages 5 to 9 of flower development) and a late phase, which includes filament elongation, anther dehiscence, and pollen maturation (stages 10 to 13). Both phases are regulated by auxin that is synthesized during stamen morphogenesis, primarily in tissues surrounding the locules (tapetum, middle layer, and endothecium), in the procambium and in microspores: auxin triggers preanthesis filament elongation but has a negative effect on anther dehiscence and pollen maturation (Cecchetti et al., 2008). We previously showed that the expression of AUX/IAA19, an auxin response gene that is involved in stamen elongation (Tashiro et al., 2009), is controlled by cellular auxin levels (Cecchetti et al., 2017). Moreover, auxin exerts its effect on anther dehiscence by negatively acting on the expression of MYB26, encoding a transcription factor that controls endothecium lignification, an early event in anther dehiscence that takes place at stage 11. The MYB26 transcript is detectable in the tapetum and endothecium at late stage 10, and MYB26 protein is localized specifically in the anther endothecium nuclei, where it regulates a number of genes linked to secondary thickening (Yang et al., 2007, 2017). Auxin also negatively controls the biosynthesis of jasmonic acid (JA), which is responsible for stomium opening, the last event of anther dehiscence (Ishiguro et al., 2001; Wilson et al., 2011; Cecchetti et al., 2013). Auxin acts through the auxin response factors (ARFs), which bind to auxin response elements (AuxREs) in auxin-regulated promoters of downstream target genes to control their expression (Ulmasov et al., 1999). Auxin controls ARF activity by regulating the degradation of AUX/IAA transcriptional repressors, which can form heterodimers with ARFs and prevent their binding to AuxRE (Kim et al., 1997). ARFs have a conserved modular structure, with a DNA binding domain at the N terminus followed by a middle region (MR), which determines whether the specific ARF activates or represses target genes (Tiwari et al., 2003), as well as a C-terminal interaction domain (PB1 domain).

Among the different ARFs, ARF6 and ARF8 play a major role in the development of different flower organs, as the arf6 arf8 double mutant has short petals, short stamen filaments, late dehiscent anthers, and immature gynoecia (Nagpal et al., 2005). The delayed anther dehiscence phenotype of arf6 arf8 stamens is possibly caused by the reduced production of JA, as ARF6 and ARF8 indirectly activate DEFECTIVE IN ANTHER DEHISCENCE1 (DAD1), the first gene in JA biosynthesis (Nagpal et al., 2005; Tabata et al., 2010). In addition, ARF6 and ARF8 transcripts are both cleavage targets of the microRNA miR167, whose overexpression mimics arf6 arf8 phenotypes (Wu et al., 2006). This, and the rescue of the decreased fertility of arf8-3 plants by a genomic ARF6 transgene, suggests that ARF6 and ARF8 act partially redundantly (Nagpal et al., 2005). In agreement with this notion, ARF6 and ARF8 have very similar DNA binding and dimerization domains (Ulmasov et al., 1999; Remington et al., 2004), diverging significantly only in the glutamine-rich middle domain.

In contrast to the sterile phenotype of arf6 arf8 flowers, single loss-of-function arf8 flowers show reduced seed production and alterations in stamen development consisting of reduced filament length due to ARF8-specific expression in stamens during late development. ARF8 is also expressed in other floral organs, particularly in petals that, similar to stamens, grow by cell expansion during late flower development (Tabata et al., 2010; Varaud et al., 2011).

Increasing evidence suggests that alternative splicing (AS) plays a role in Arabidopsis flower development. Thousands of transcripts generated by AS, and in particular by intron retention, are differentially expressed between different floral stages (Wang et al., 2014). However, only in a few cases has the expression of splice variants been correlated with the development of flower organs: Jasmonate signaling in stamens is controlled by the splice variant JAZ10.4, which lacks the Jas domain and produces a male-sterile phenotype when overexpressed (Chung and Howe, 2009); cell division and expansion in petals is controlled by the interaction of ARF8 with the transcription factor BIGPETAL, which originates from an intron retention splicing event (Varaud et al., 2011); the ARF4 splice variant, ΔARF4, leading to a truncated protein, has a different function from the full-length ARF4 during carpel development (Finet et al., 2013).

Two different splice variants of ARF8 have been reported (according to TAIR 10 genome annotation), named ARF8.1 and ARF8.2, but their specific functions in stamen development, as well as in other floral organs, remain unclear.

In this study, we report the identification of a novel flower-specific intron-retaining splice variant of ARF8 (ARF8.4) in Arabidopsis and describe its effects on stamen development compared with splice variants ARF8.1 and ARF8.2. Through functional and expression analysis, we demonstrate that ARF8.4 controls stamen elongation and anther dehiscence by directly regulating a specific set of downstream genes.

RESULTS

A New mRNA Splice Variant of ARF8 Is Expressed in Stamens

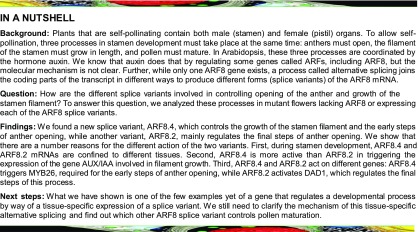

The Arabidopsis gene ARF8 contains 14 exons and generates two distinct mRNAs, the full-length ARF8.1 and the splice variant ARF8.2 (TAIR 10 genome annotation) (Figure 1A). The latter has a splice defect leading to a premature stop codon four nucleotides downstream of the 3′ end of exon 13 (Figure 1A). The putative ARF8.2 protein lacks the last 38 amino acids encoded by exon 14, thus showing a truncated terminal region of the PB1 domain (Figure 1B). We set out to assess whether, like ARF8.1, ARF8.2 is also expressed in flowers at late developmental stages. We thus performed RT-PCR analysis of ARF8.1 and ARF8.2 transcripts levels in flower buds at stages 9 and 10, when ARF8 is known to be expressed (Wu et al., 2006), and found that ARF8.2 transcript levels were ∼2-fold lower than those of ARF8.1 (Figures 1C and 1D; Supplemental Table 1). While cloning ARF8.2, we isolated an additional as yet undescribed splice variant that, like ARF8.2, contained a stop codon at the end of exon 13 but retained an in-frame intron between exons 8 and 9 (Supplemental Figures 1A to 1C). While ARF8 is expressed ubiquitously, the expression of this variant is flower specific (Figure 1E). We designated this variant ARF8.4 (Figure 1A) because a splice variant named ARF8.3, which does not contain a premature stop codon but lacks exon 1 and 34 nucleotides of exon 2, was recently annotated in Araport11 (Cheng et al., 2017). The predicted ARF8.4 protein thus lacks a portion of the PB1 domain (as ARF8.2) and contains an additional leucine-rich sequence of 28 amino acids in the MR (Figure 1B). An alignment of the putative amino acid sequences of ARF8.1, ARF8.2, and ARF8.4 is shown in Supplemental Figure 1D.

Figure 1.

Identification and Expression Analysis of the ARF8 Splice Variant ARF8.4.

(A) Schematic diagram of the splicing variants At5g37020.1, At5g37020.2, and At5g37020.4 encoding ARF8.1, ARF8.2, and ARF8.4, respectively. Rectangles (white, translated; gray, untranslated) represent exons, and black lines represent introns. Asterisks indicate the premature stop codon and the sequence at the splicing site in ARF8.2 and ARF8.4, and the black box indicates intron 8 retention in ARF8.4.

(B) Contribution of intron retention and premature stop codon to ARF8 protein domains. Thirty-eight amino acids in the terminal region of the PB1 domain are deleted in ARF8.2 and ARF8.4, and 28 amino acids are inserted in the ARF8.4 MR.

(C) Schematic diagram of the regions of interest (from exon 8 to 3′ untranslated region) of ARF8.1, ARF8.2, and ARF8.4 transcripts. Primers used for RT-PCR 1, RT-PCR 2, and qRT-PCR are shown. F, forward; R, reverse.

(D) RT-PCR analysis of ARF8.2, ARF8.1, and ARF8.4. Twenty-eight to 35 cycles were used to detect the abundance of each splice variant in wild-type flower buds at stages 9 and 10 using the following primers: 1F and 2R (amplicon size 1540 bp), 1F and 3R (amplicon size 1544 bp), 4F and 3R (amplicon size 1607 bp) for ARF8.1, ARF8.2, and ARF8.4, respectively (upper panel RT-PCR 1). Thirty-five and 40 cycles were used to detect the abundance of ARF8.4 (amplicon size 345 bp) compared with ARF8.1+ARF8.2 (amplicon size 261 bp) in wild-type stamens at stages 9 and 10, using 11F and 11R primers (lower panel RT-PCR 2). M, DNA markers.

(E) Quantitative analysis by qRT-PCR of ARF8.4 transcript in various organs, using 4F and 5R primers, showing negligible expression in organs other than inflorescences (value set to 1). ARF8.4 cDNA levels are relative to actin cDNA. Values are means ± se of nine data points obtained from three biological replicates that were each analyzed in triplicate. Biological replicates were obtained by pooling organs isolated from five independently grown plants or 7-d-old seedlings.

(F) Comparative analysis by qRT-PCR of ARF8.4 and ARF8.1+ARF8.2 transcript levels in wild-type stamens at different developmental stages, using 4F and 5R, and 1F and 5R primers, respectively. ARF8.1+ARF8.2 or ARF8.4 cDNA levels are relative to actin cDNA. Values are means ± se of nine data points obtained from three biological replicates that were each analyzed in triplicate. Biological replicates were obtained by pooling stamens from flowers at different developmental stages isolated from five independently grown plants.

A comparative RT-PCR analysis of flower buds at stages 9 and 10, using specific primers for ARF8.4 (Figure 1C) and verified by sequencing, showed that ARF8.4 was expressed at very low levels (Figure 1D). To confirm the low level of ARF8.4 transcript in stamens, a comparative RT-PCR analysis was performed using the same primer pairs to amplify all three variants, two primers upstream and downstream of intron 8, respectively (Figure 1C; Supplemental Table 1). As shown in Figure 1D, the level of the ARF8.4 amplicon encompassing intron 8 was much lower than that of ARF8.1+ARF8.2. In order to assess the expression patterns of the three splice variants during stamen development, we performed qRT-PCR on stamens at stages 9, 10, 11, and 12. Due to the high degree of nucleotide identity between ARF8.1 and ARF8.2, we could not design primers for this quantitative analysis that would allow us to distinguish ARF8.1 from ARF8.2 and ARF8.2 from ARF8.4 at the same time. Thus, we compared the level of ARF8.4 transcript to that of ARF8.1 and ARF8.2 combined (ARF8.1+ARF8.2; see Figure 1C and Supplemental Table 1). As shown in Figure 1F, ARF8.1+ARF8.2 transcripts were abundant at stage 9, decreased ∼2-fold at stage 10, and decreased an additional eightfold at stages 11 and 12. The expression profile of ARF8.4 was similar to that of ARF8.1+ARF8.2, as the ARF8.4 transcript level was high at stage 9, decreased 7-fold at stage 10, and was low at stages 11 and 12.

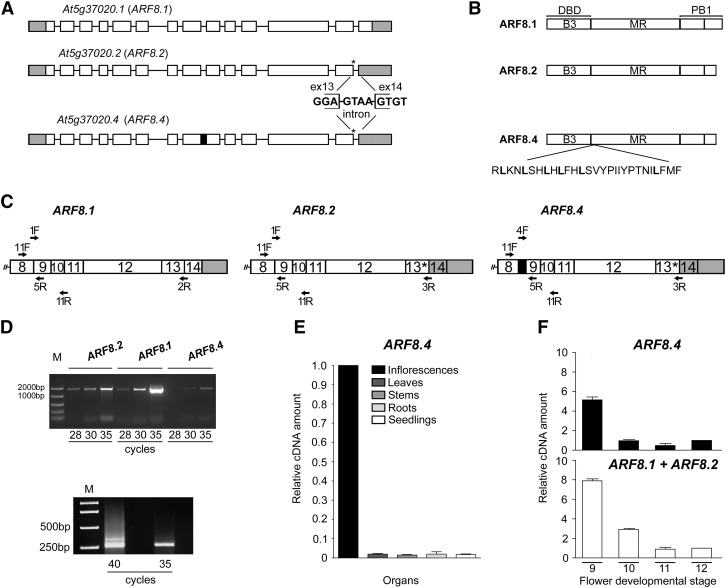

ARF8 expression in different stamen tissues was previously analyzed by RNA in situ hybridizations using probes against the 3′ region (Goetz et al., 2006) or against exon 13 (Wu et al., 2006; Rubio-Somoza and Weigel, 2013): thus, both probes did not allow us to distinguish between the three splice variants. To analyze the tissue-specific localization of ARF8.4 during stamen development, we performed in situ hybridization analysis on sections of flower buds from stages 9 to 12 using an ARF8.4-specific probe (see Methods). As shown in Figure 2 and Supplemental Figure 2, ARF8.4 mRNA was detectable at early stage 9 in anther locules (Figure 2A), at late stage 9 in tissues surrounding the locules (Figure 2B), and at stage 10 in the latter and in the anther procambium (Figure 2C); subsequently, at stage 11 (Figure 2D) and early stage 12 (Figure 2E), the signal was observed only in the procambium. We also performed a comparative expression analysis using a probe that hybridizes to ARF8.1+ARF8.2, but also to ARF8.4 (referred to as ARF8). The signal was observed at late stages 9 (Figure 2G) and 10 (Figure 2I) mainly in the filament procambium, while a very faint signal was also detectable in the tapetum at stage 10 (Figure 2H); a signal was detectable at stage 12 only in pollen grains (Figure 2K). Thus, the localization of ARF8.4 mRNA during late stages of stamen development points to tissue-specific production of the ARF8.4 splice variant during stamen development.

Figure 2.

Analysis of Expression Profile of ARF8.4 in Wild-Type and ARF8ox-arf8 Flower Buds and GFP-ARF8.4/ RFP-ARF8.2 Localization in Tobacco Epidermal Cells.

(A) to (E) RNA in situ hybridization of ARF8.4. Primers used to generate the specific probe are shown on the schematic diagram of the region of interest. Transverse sections of anthers are shown.

(A) Anther at early stage 9. A signal is visible in the locules.

(B) Anther at late stage 9. A signal is visible in the endothecium, middle layer, and tapetum.

(C) Anther at stage 10. A signal is visible in the endothecium, middle layer, tapetum, and procambium.

(D) Anther at stage 11. A signal is visible in the procambium.

(E) Anther at stage 12. A weak signal is visible in the procambium.

(F) to (K) RNA in situ hybridization of ARF8. Primers used to generate the probe are shown on the schematic diagram of the region of interest. Longitudinal and transverse sections of stamens and anthers are shown.

(F) Anther at early stage 9. Signal is absent.

(G) Anther at late stage 9. A very strong signal is visible in the filament procambium.

(H) and (I) Stamen at stage 10. A weak signal is visible in the tapetum (H) and in the filament procambium (I).

(J) Stamen at stage 11. Signal is absent.

(K) Anther at stage 12. A signal is visible in pollen grains. Bars = 20 μm in (A) to (H) and (K) and 10 μm in (I) and (J).

(L) and (M) Confocal microscopy images of the leaf epidermis of tobacco transiently expressing GFP-ARF8.4.

(L) Transmitted light image of epidermal cells.

(M) Green fluorescence due to GFP-ARF8.4 localized specifically in the nucleus. Blue fluorescence is due to chloroplasts. Bar = 20 µm.

(N) to (P) Confocal microscopy images of the leaf epidermis of tobacco transiently expressing GFP-ARF8.4 and RFP-ARF8.2. Bar = 20 µm.

(N) Fluorescence due to GFP-ARF8.4 is efficiently localized in the nucleus.

(O) Fluorescence due to RFP-ARF8.2 is localized in both the cytosol and the nucleus.

(P) Merge of fluorescent signals showing colocalization in the nucleus but not in the surrounding cytosol.

(Q) to (U) RNA in situ hybridization of ARF8.4 in ARF8.4ox-arf8 flowers. The probe used is the one shown on the schematic diagram relative to ARF8.4. Longitudinal and transverse sections of stamens and anthers are shown.

(Q) Anther at early stage 9. A signal is visible in the locules.

(R) Anther at late stage 9. A signal is visible in the endothecium, middle layer, and tapetum.

(S) Anther at stage 10. A signal is visible in the endothecium, middle layer, tapetum, and procambium.

(T) Anther at stage 11. A signal is visible in the procambium.

(U) Anther at stage 12. A signal is visible in the procambium. Bars = 10 µm in (Q) and (S) to (U) and 20 µm in (R).

En, endothecium; Lc, locule; ML, middle layer; P, procambium; PG, pollen grains; T, tapetum.

To assess whether ARF8.4 is translated into a protein, we used ARF8.4 cDNA to generate chimeric constructs tagged with GFP at the N terminus (GFP-ARF8.4) and with GFP or RFP at the C terminus of ARF8.4 (ARF8.4-GFP and -RFP), respectively (Di Sansebastiano et al., 2015). These constructs were utilized for transient expression of ARF8.4 in tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) epidermis (Di Sansebastiano et al., 2004). As shown in Figure 2 and Supplemental Figure 2, ARF8.4 protein was translated from both GFP and RFP fusion constructs. The GFP signal was specifically localized to the nuclei in GFP-ARF8.4-expressing cells, as expected for a fusion protein with a transcription factor (Figures 2L and 2M). ARF8.4-GFP and ARF8.4-RFP proteins were primarily localized to the cytosol, possibly due to folding problems with these fusion proteins (Supplemental Figures 2H to 2K) (Hu et al., 2015; Liu et al., 2017). We also used ARF8.2 cDNA to generate a chimeric construct tagged with RFP at the N terminus (RFP-ARF8.2) and we coexpressed this construct with the nuclear GFP-ARF8.4 construct. As shown in Figures 2N to 2P, the RFP signal was predominantly found in the cytosol, indicating that RFP-ARF8.2 is not transported into the nucleus as efficiently as GFP-ARF8.4.

Furthermore, to rule out the possibility that splicing out of the exitron (exonic intron) from the GFP-ARF8.4 construct would lead to the presence of a GFP-ARF8.2 splice variant, we analyzed the levels of ARF8.4 and ARF8.2 transcripts in tobacco cells transformed with GFP-ARF8.4. qRT-PCR analysis using primers for ARF8.2 and ARF8.4 with comparable activity showed that in GFP-ARF8.4 tobacco cells, the transcript level of ARF8.2 was negligible compared with that of ARF8.4 (Supplemental Figures 2L and 2M). These results confirm that the splice variant ARF8.4 is indeed translated and efficiently transported to the nucleus indicating that intron 8 can be regarded as an exitron (exonic intron; Marquez et al., 2015).

To gain further insight into the function of intron 8, we conducted evolutionary analysis. We compared the Columbia intron 8 sequence to that of the other Arabidopsis accessions to identify a possible functional single nucleotide polymorphism or indel (insertion/deletion; Supplemental File 1). The different ARF8 sequences were downloaded from http://1001genomes.org/ and aligned by Clustal Omega (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalo/). No differences were present in either the 5′ or 3′ splice site or in the entire intron sequence of any of the accessions, suggesting a functional context for exitron (intron 8) inclusion or splicing.

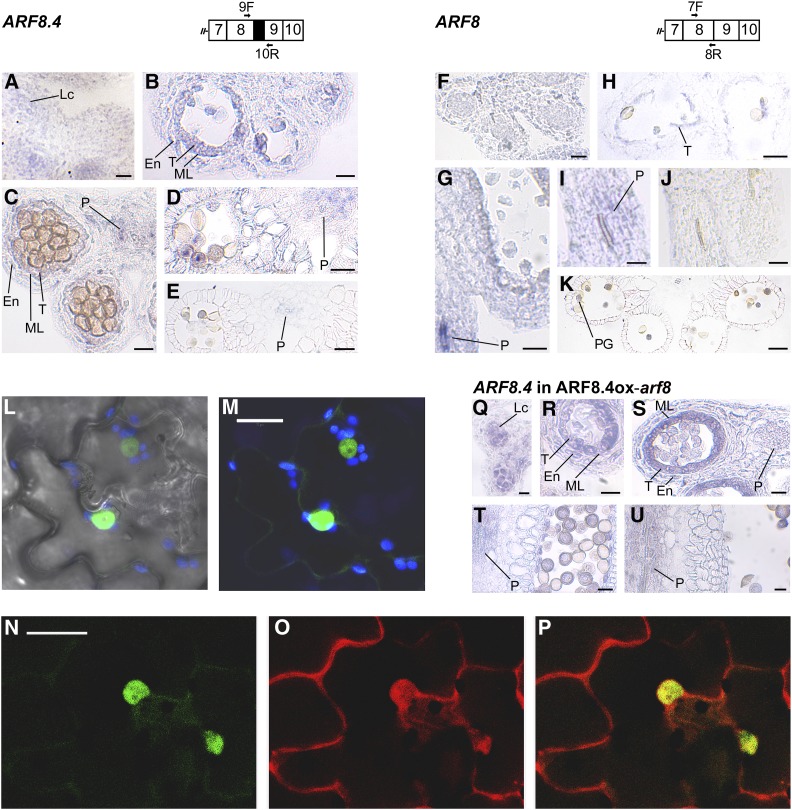

ARF8.4 Plays a Key Role in the Control of Filament Elongation

Several ARF8 mutant alleles have stamen filaments shorter than those of wild-type flowers (Nagpal et al., 2005; Varaud et al., 2011), suggesting a specific role of ARF8 in controlling filament elongation. In this work, we focused on arf8-7, an insertion mutant in intron 3 of ARF8 (Gutierrez et al., 2009) that shows a negligible level of ARF8 transcript (Supplemental Figure 3A). Flowers of the arf8-7 mutant have stamen filaments ∼16% shorter than those of wild-type flowers (Figure 3A) due to a reduced cell length, as determined by microscopy analysis of epidermal cells (Figure 3C), while the timing of anther dehiscence is not affected, occurring at stage 13 as in wild-type flowers (Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

ARF8.4 Expression Rescues the Short-Stamen Phenotype of arf8-7 Flowers by Inducing Cell Elongation and Causes an Increase in Wild-Type Stamen Length.

(A) Wild-type, arf8-7, ARF8.4ox-arf8 (8.4ox-arf8), ARF8.2ox-arf8 (8.2ox-arf8), and ARF8.1ox-arf8 (8.1ox-arf8) flowers at stage 14, showing a reduced stamen length in arf8-7 and estradiol-treated ARF8.1ox-arf8 flowers, a normal stamen length in ARF8.4ox-arf8 flowers, and a slight increase in stamen length, compared with arf8-7, in ARF8.2ox-arf8 flowers. Asterisks indicate a significant difference from the wild-type value: **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001. Means ± se were obtained from flowers isolated from nine independent plants for each genotype.

(B) Comparative analysis by qRT-PCR of ARF8.1+ARF8.2 and ARF8.4 transcript levels in mock- and estradiol-treated arf8-7 inflorescences expressing ARF8.1 and ARF8.2 or ARF8.4. ARF8.1+ARF8.2 or ARF8.4 cDNA levels are relative to actin cDNA. Values are means ± se of nine data points obtained from three biological replicates that were each analyzed in triplicate. Biological replicates were obtained by pooling mock-treated or estradiol-treated inflorescences isolated from five independently grown plants for each genotype. Asterisks indicate a significant difference from the control value (-est): **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001. est, estradiol.

(C) Epidermal cell length in the middle region of wild-type, arf8-7, ARF8.4ox-arf8 (8.4ox-arf8), ARF8.2ox-arf8 (8.2ox-arf8), and ARF8.1ox-arf8 (8.1ox-arf8) stamens from estradiol-treated flowers at stage 14. A reduced cell length (outlined in red) is visible in arf8-7 and estradiol-treated ARF8.1ox-arf8 stamens and an increased cell length is visible in ARF8.4ox-arf8 stamens in comparison to wild-type stamens. A slight increase in cell length, compared with arf8-7, is visible in ARF8.2ox-arf8 stamens from estradiol-treated flowers. Bars = 40 μm.

(D) Stamen length (percentage relative to the wild type) in mock- and estradiol-treated ARF8.1ox (8.1ox), ARF8.2ox (8.2ox), and ARF8.4ox (8.4ox) flowers at stage 14. Means ± se were obtained from wild-type stamens and stamens isolated from mock-treated or estradiol-treated inflorescences of five independent plants for each genotype. Asterisk indicates a significant difference from the control value (-est): *P < 0.05.

To assess a possible specific role of ARF8.4 in stamen development, we transformed three different constructs harboring the ARF8.1, ARF8.2, and ARF8.4 coding sequences under the control of the estradiol-inducible promoter pER8 (Zuo et al., 2000) into arf8-7 lines (Supplemental Figure 3B). Three different homozygous lines for each genotype, ARF8.1ox-arf8, ARF8.2ox-arf8, and ARF8.4ox-arf8, were analyzed for the expression of ARF8 splice variants by qRT-PCR. All genotypes expressed the respective splice variant at comparable levels (Figure 3B). The transcript levels of ARF8.1+ARF8.2 were not significantly increased in arf8 inflorescences expressing ARF8.4ox, indicating that intron 8 is not spliced out, i.e., these lines actually express ARF8.4.

We measured stamen filament length in flowers at stage 14 from mock-treated inflorescences (Supplemental Figure 4A), estradiol-treated inflorescences of ARF8.1ox-arf8, ARF8.2ox-arf8, and ARF8.4ox-arf8 plants, and inflorescences from untreated wild-type plants. As shown in Supplemental Figure 4A and Figure 3A, after estradiol treatment, ARF8.4ox-arf8 stamens were longer than their mock-treated counterparts and equal to wild-type stamens, whereas ARF8.2ox-arf8 stamens were longer than their mock-treated controls but shorter (∼8%) than the wild type. In contrast, no effect on filament length was observed in ARF8.1ox-arf8 flowers. Analysis of stamen filament epidermal cells showed that the promotion of filament growth in ARF8.4ox-arf8 as well as in ARF8.2ox-arf8 stamens was due to an increased cell length (Figure 3C; Supplemental Figure 4B). Thus, only the expression of ARF8.4 is capable of fully complementing the short-stamen phenotype of the arf8-7 mutant, suggesting this splice variant plays a major role in stamen elongation.

To rule out the possibility that the increase in stamen elongation of ARF8.4ox lines is due to ectopic expression of the gene driven by the inducible promoter utilized, we analyzed the tissue-specific localization of ARF8.4 during stamen development in estradiol-treated flowers from ARF8.4ox-arf8 lines. As shown in Figures 2Q to 2U and Supplemental Figure 2, ARF8.4 mRNA was detected at the same stages, i.e., early 9, late 9, 10, 11, and 12, and with the same tissue specificity as in wild-type stamens (Figures 2A to 2E), suggesting that the observed phenotype is not due to the ectopic expression of ARF8.4.

We then transformed the same ARF8.1, ARF8.2, and ARF8.4 inducible constructs into wild-type plants to generate lines overexpressing the individual splice variants in a wild-type background (Supplemental Figure 3C). As shown in Figure 3D, after estradiol induction, the length of ARF8.1ox and ARF8.2ox stamens was equal to that of untransformed wild-type and mock-treated flowers, while ARF8.4ox stamens were significantly longer (∼7%), confirming a specific role for this splice variant in the control of stamen elongation.

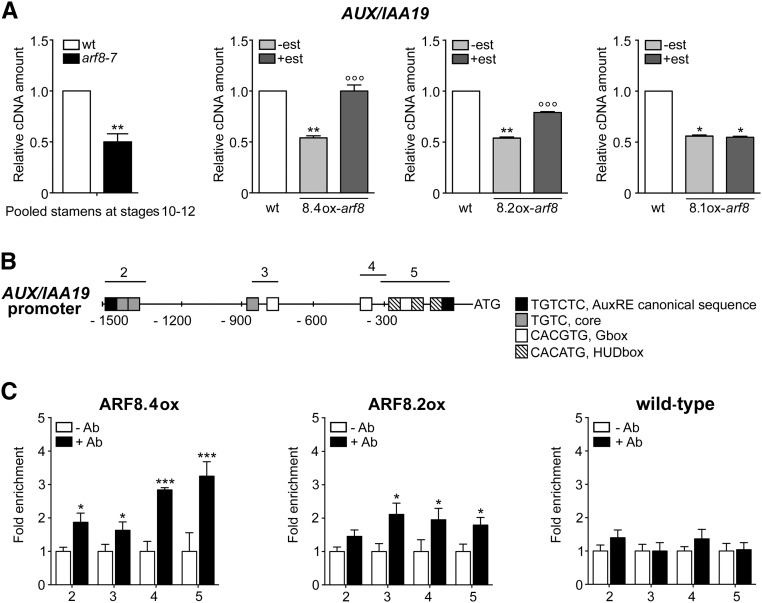

ARF8.4 Controls Stamen Elongation by Directly Regulating AUX/IAA19

In order to identify genes involved in ARF8-mediated control of filament elongation, we performed a transcriptomic analysis of wild-type and arf8-7 stamens at stages 10-12, when filament elongation occurs. A total of 911 genes were upregulated and 217 downregulated in arf8-7 versus the wild type. Since ARF8 is a transcriptional activator (Guilfoyle and Hagen, 2007), we focused on genes that were downregulated in arf8-7. Among the auxin-related genes identified by gene ontology analysis was AUX/IAA19 (Table 1), which is expressed specifically in stamens and is involved in filament elongation (Tashiro et al., 2009; Cecchetti et al., 2017); the downregulation of AUX/IAA19 in arf8-7 was confirmed by qRT-PCR on stage 10-12 stamens (Figure 4A). This suggests the possibility that the above-described increase in filament length observed in estradiol-induced ARF8.4ox-arf8 (and, to a lesser extent, ARF8.2ox-arf8) might be caused by an increase in AUX/IAA19 expression.

Table 1. GO Enrichment Analysis of Auxin Downregulated Genes in arf8-7 Stamens.

| GO ID | GO Term | Gene ID | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| GO:0010928 | Regulation of auxin-mediated signaling pathway | At2g43010 | PHYTOCHROME INTERACTING FACTOR4 |

| At3g59060 | PIF5; PIL6 | ||

| PHYTOCHROME INTERACTING FACTOR3-LIKE6 | |||

| GO:0010252 | Auxin homeostasis | At1g52830 | INDOLE-3-ACETIC ACID6 |

| At2g06850 | XYLOGLUCAN ENDOTRANSGLUCOSYLASE/HYDROLASE4 | ||

| At3g15540 | INDOLE-3-ACETIC ACID INDUCIBLE19 (AUX/IAA19) | ||

| GO:0009733 | Response to auxin | At2g23170 | AUXIN-RESPONSIVE GH3 FAMILY PROTEIN |

Figure 4.

ARF8.4 Expression Restores Normal AUX/IAA19 Transcript Levels in arf8-7 Inflorescences, and ARF8.4 Directly Binds More Efficiently Than ARF8.2 to the AUX/IAA19 Promoter.

(A) Comparative analysis by qRT-PCR of AUX/IAA19 transcript levels in wild-type and arf8-7 stamens at stages 10-12, and in mock- and estradiol-treated arf8-7 inflorescences expressing ARF8.4 (8.4ox), ARF8.2 (8.2ox), or ARF8.1 (8.1ox). AUX/IAA19 cDNA levels are relative to actin cDNA. Values are means ± se of nine data points obtained from three biological replicates that were each analyzed in triplicate. Biological replicates were obtained by pooling either stamens at stages 10-12, wild-type inflorescences, mock- or estradiol-treated inflorescences from five independent plants for each genotype. Asterisks indicate a significant difference from the wild-type value: *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01. Circles indicate a significant difference from the mock-treated value: °°P < 0.01 and °°°P < 0.001. est, estradiol.

(B) Schematic diagram of putative ARF binding sites in the AUX/IAA19 promoter (1500 bp from the transcription start site). The upper black lines indicate fragments amplified in ChIP-qPCR assays.

(C) Chromatin immunoprecipitation analysis of ARF8.4 and ARF8.2 binding to the AUX/IAA19 promoter. Enrichment was observed in all four regions in ARF8.4-overexpressing inflorescences and in regions 3, 4, and 5 in ARF8.2-overexpressing inflorescences. ChIP-qPCR values are means ± se of nine data points obtained from three biological replicates that were each analyzed in triplicate. Biological replicates were obtained by pooling inflorescences isolated from 50 independently grown plants for each genotype. Asterisks indicate a significant difference from the -Ab control value: *P < 0.05 and ***P < 0.001. Ab, antibody.

To test this hypothesis, we measured AUX/IAA19 transcript levels by qRT-PCR in ARF8.4ox-arf8, ARF8.2ox-arf8, and ARF8.1ox-arf8 inflorescences. As shown in Figure 4A, estradiol treatment resulted in a 2-fold increase in AUX/IAA19 transcript levels in ARF8.4ox-arf8, a smaller increase in ARF8.2ox-arf8 (1.5-fold), and no increase in ARF8.1ox-arf8 inflorescences.

To establish whether ARF8.4 (and ARF8.2) directly regulate AUX/IAA19 expression, we tested possible in vivo interactions of these proteins with AUX/IAA19 promoter elements by chromatin immunoprecipitation-quantitative PCR (ChIP-qPCR) assays using lines overexpressing functional HA-FLAG-tagged ARF8.4 or ARF8.2 (Supplemental Figure 5). The AUX/IAA19 promoter contains auxin-related cis-elements, such as AuxRE, G-boxes, and HUD boxes, distributed throughout four regions (2, 3, 4, and 5), as shown in Figure 4B. The results of the ChIP-qPCR analysis using primers for all four regions (Supplemental Table 1) showed that in ARF8.4 flower buds, regions 5, 4, 3, and 2 are enriched (3.25-, 2.84-, 1.80-, and 1.95-fold, respectively). In ARF8.2 flower buds, regions 5 and 4 are enriched, but significantly less so than in ARF8.4 (1.83- and 1.87-fold, respectively), and region 3 is roughly equally represented (2.1-fold), while region 2 is not enriched in these flower buds (Figure 4C).

Thus, ARF8.4 controls stamen elongation by directly regulating the expression of AUX/IAA19. In accordance with its lesser regulatory role in stamen elongation, ARF8.2 binds to the promoter of this gene less efficiently than the ARF8.4 variant.

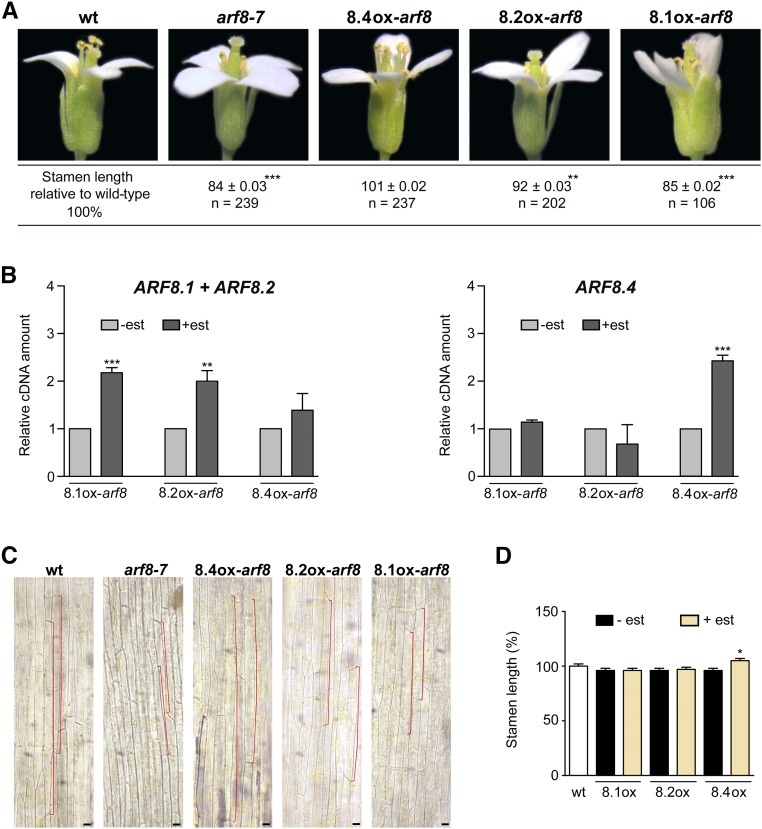

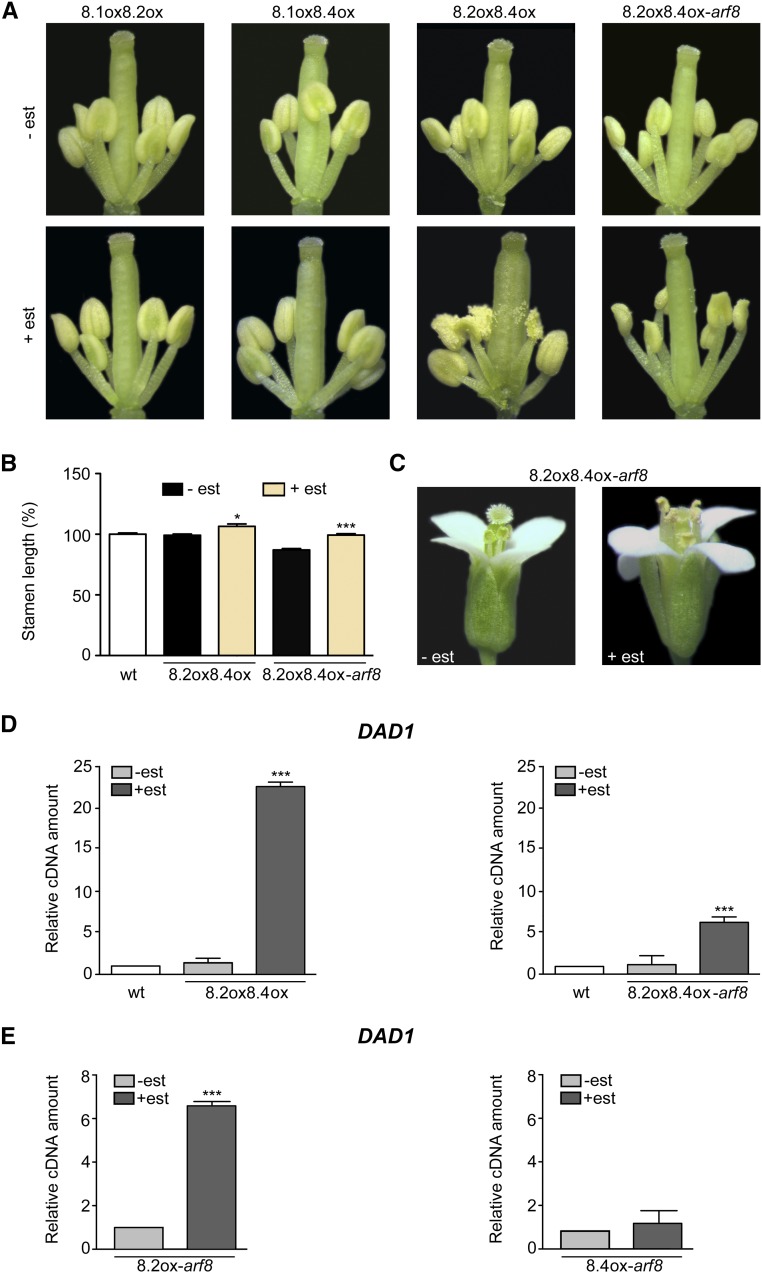

ARF8.4 and ARF8.2 Control the Timing of Anther Dehiscence

Anther dehiscence is delayed in arf6 arf8, while arf8 flowers (including arf8-7) have a normal timing of anther dehiscence (above; Nagpal et al., 2005), possibly due to redundancy of the effects of the two genes. To assess a possible role for ARF8 in anther dehiscence, we compared wild-type and arf8-7 lines harboring estradiol-inducible single splice variants. As shown in Supplemental Figure 6, estradiol-treated flowers expressing ARF8.1, ARF8.2, or ARF8.4 in the wild-type and arf8-7 backgrounds showed a normal timing of anther dehiscence. We then analyzed lines expressing all combinations of the two splice variants. As expected, lines coexpressing ARF8.4 and ARF8.2, both in the wild-type and arf8-7 background, showed an increased stamen filament length when analyzed at stage 14 (Figures 5B and 5C). Importantly, analysis performed in flowers at stage 12 showed precocious dehiscence in these lines (Figure 5A), while all other plants, including ARF8.1oxARF8.2ox-arf8 and ARF8.1oxARF8.4ox-arf8 (Supplemental Figure 6), and ARF8.1oxARF8.2ox and ARF8.1oxARF8.4ox (Figure 5A), showed normal dehiscence timing. These results suggest that ARF8 indeed plays a role in anther dehiscence via the combined action of its two splicing variants, ARF8.4 and ARF8.2.

Figure 5.

Coexpression of ARF8.4 and ARF8.2 Rescues the Short-Stamen Phenotype of arf8-7 Flowers and Causes Precocious Anther Dehiscence, Partly Due to the Increased DAD1 Transcript Level Induced by ARF8.2.

(A) Flowers at early stage 12 from mock- and estradiol-treated inflorescences overexpressing ARF8.1 and ARF8.2 (8.1ox8.2ox), ARF8.1 and ARF8.4 (8.1ox8.4ox), or ARF8.2 and ARF8.4 (8.2ox8.4ox) and from mock- and estradiol-treated arf8-7 inflorescences coexpressing ARF8.2 and ARF8.4 (8.2ox8.4ox-arf8). Mock-treated or estradiol-treated flowers were isolated from five independent plants for each genotype. est, estradiol.

(B) Stamen length (percentage relative to the wild type) in mock- and estradiol-treated ARF8.2ox ARF8.4ox (8.2ox8.4ox) and ARF8.2oxARF8.4ox-arf8 (8.2ox8.4ox-arf8) flowers at stage 14. Means ± se were obtained from wild-type stamens and stamens isolated from mock-treated or estradiol-treated inflorescences of five independent plants for each genotype. Asterisks indicate a significant difference from the control value (-est): *P < 0.05 and ***P < 0.001.

(C) Flowers at stage 14 from mock- and estradiol-treated arf8-7 inflorescences coexpressing ARF8.2 and ARF8.4 (8.2ox8.4ox-arf8).

(D) Comparative analysis by qRT-PCR of DAD1 transcript levels in mock- and estradiol-treated wild-type inflorescences overexpressing ARF8.2 and ARF8.4 (8.2ox8.4ox) and in arf8-7 mock- and estradiol-treated inflorescences coexpressing ARF8.2 and ARF8.4 (8.2ox8.4ox-arf8). DAD1 cDNA levels are relative to actin cDNA. Values are means ± se of nine data points obtained from three biological replicates that were each analyzed in triplicate. Biological replicates were obtained by pooling either wild-type, mock-treated, or estradiol-treated inflorescences from five independent plants for each genotype. Asterisks indicate a significant difference from the control value (-est): ***P < 0.001.

(E) Comparative analysis by qRT-PCR of DAD1 transcript levels in mock- and estradiol-treated arf8-7 inflorescences overexpressing ARF8.2 (8.2ox-arf8) or ARF8.4 (8.4ox-arf8). DAD1 cDNA levels are relative to actin cDNA. Values are means ± se of nine data points obtained from three biological replicates that were each analyzed in triplicate. Biological replicates were obtained by pooling mock-treated or estradiol-treated inflorescences from five independent plants for each genotype. Asterisks indicate a significant difference from the control value (-est): ***P < 0.001.

We previously showed that the timing of anther dehiscence is influenced by both the level of JA and the timing of endothecium lignification (Cecchetti et al., 2013). Thus, the early anther dehiscence of lines coexpressing ARF8.4 and ARF8.2 could be caused by an effect on JA, lignification, or both.

ARF8.2 Regulates the JA Biosynthetic Gene DAD1

We therefore performed qRT-PCR to analyze the expression level of the JA biosynthetic gene DAD1 in mock- and estradiol-treated inflorescences of plants harboring the ARF8.2oxARF8.4ox constructs in the wild-type and arf8-7 background. As shown in Figure 5D, in the ARF8.2oxARF8.4ox and ARF8.2oxARF8.4ox-arf8 lines, DAD1 transcript levels were much higher than in the controls (20- and 6-fold, respectively). To assess the contribution of the individual splice variants to DAD1 expression, we analyzed DAD1 transcript levels in arf8-7 inflorescences individually expressing ARF8.2 or ARF8.4. As shown in Figure 5E, DAD1 transcript levels were much higher in estradiol-treated ARF8.2ox inflorescences than in mock-treated controls, while there was no increase in lines expressing ARF8.4ox. These results suggest that the splice variant ARF8.2 is the one responsible for the control of stomium opening (the last step in anther dehiscence) through its effect on JA biosynthesis.

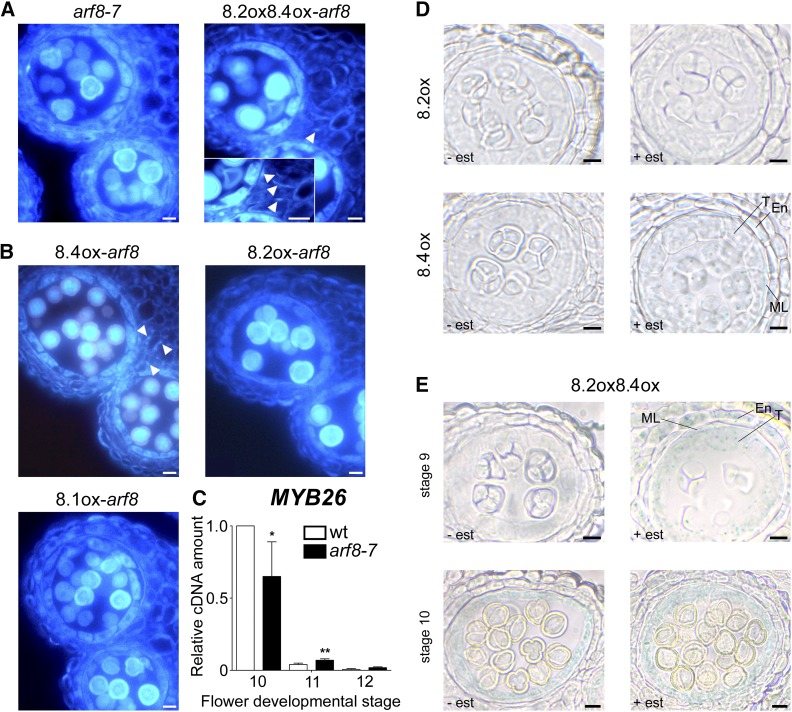

ARF8.4 Regulates the Timing of Endothecium Lignification via MYB26

To investigate endothecium lignification, we performed histological fluorescence analysis of lignin deposition in lines coexpressing ARF8.2 and ARF8.4. After estradiol treatment, a small percentage of anthers, consistent with the percentage of early dehiscent ones reported above, from both ARF8.2oxARF8.4ox-arf8 flower buds, in comparison with arf8-7 anthers (Figure 6A), and ARF8.2oxARF8.4ox flower buds, in comparison with wild-type anthers (Supplemental Figures 7A and 7B), showed precocious lignification. In these anthers, lignin fibrous bands were already visible at stage 10 (Figure 6A), while in the mock-treated controls as well as in the wild type, lignin autofluorescence first became detectable at stage 11 (Supplemental Figure 7A). To assess the contribution of each splice variant in controlling the timing of endothecium lignification, we analyzed lignin deposition in arf8-7 inflorescences individually expressing ARF8.4, ARF8.2, or ARF8.1. As shown in Figure 6B, lignin fibrous bands were visible at stage 10 only in ARF8.4ox-arf8 anthers. In contrast, in ARF8.2ox-arf8 and ARF8.1ox-arf8 anthers, as well as in mock-treated anthers, autofluorescence began to be detectable at stage 11 (Figure 6B; Supplemental Figure 7A), suggesting that endothecium lignification is controlled by the splice variant ARF8.4.

Figure 6.

Endothecium Lignification Is Precocious in arf8-7 Anthers Coexpressing ARF8.2 and ARF8.4 and in Anthers Overexpressing ARF8.4, and Premature ProMYB26:GUS Activity Is Induced by ARF8.4.

(A) Transverse sections of arf8-7 anthers, arf8-7 coexpressing ARF8.2, and ARF8.4 (8.2ox8.4ox-arf8) anthers at stage 10, visualized by fluorescence microscopy. Endothecium lignification is absent in arf8-7 anthers, whereas lignin autofluorescence is visible in the endothecium of arf8-7 anthers coexpressing ARF8.2 and ARF8.4 (arrowhead). Inset: Higher magnification showing a better detail of the lignin fibrous bands in the endothecium (arrowheads). Bars = 10 μm.

(B) Transverse sections of arf8-7 anthers expressing ARF8.4 (8.4ox-arf8), ARF8.2 (8.2ox-arf8), or ARF8.1 (8.1ox-arf8) at stage 10, visualized by fluorescence microscopy. Endothecium lignification is absent in arf8-7 anthers expressing ARF8.2 or ARF8.1, whereas lignin autofluorescence is visible in the endothecium of arf8-7 anthers expressing ARF8.4 (arrowheads). Bars = 10 μm.

(C) Quantitative analysis by qRT-PCR of MYB26 transcript in wild-type and arf8-7 stamens at developmental stages 10, 11, and 12. MYB26 cDNA levels are relative to actin cDNA. Values are means ± se of nine data points obtained from three biological replicates that were each analyzed in triplicate. Biological replicates were obtained by pooling stamens from flowers at different developmental stages isolated from five independently grown plants for each genotype. Asterisks indicate a significant difference from the wild-type value: *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01.

(D) Histochemical analysis of mock- and estradiol-treated ARF8.2ox-ProMYB26:GUS (8.2ox) and ARF8.4ox-ProMYB26:GUS (8.4ox) anthers at early stage 9. GUS staining is absent in 8.2ox but is visible in estradiol-treated 8.4ox anthers, localized in the endothecium, middle layer, and tapetum.

(E) Histochemical analysis of mock- and estradiol-treated ARF8.2oxARF8.4ox-ProMYB26:GUS (8.2ox8.4ox) anthers at early stage 9 and stage 10. GUS staining is visible in estradiol-treated 8.2ox8.4ox anthers at stage 9, localized in the endothecium, middle layer, and tapetum.

En, endothecium; ML, middle layer; T, tapetum. est, estradiol. Bars = 10 µm.

The timing of endothecium lignification is related to that of MYB26 expression, which in anthers peaks at late stage 10 and subsequently decreases at stages 11 and 12 (Yang et al., 2007; Cecchetti et al., 2013). We compared the level of MYB26 transcript in wild-type and arf8-7 stamens at different developmental stages. As shown in Figure 6C, in arf8-7 flowers, MYB26 expression was slightly delayed, since the peak at stage 10 was lower than that of wild-type stamens, while MYB26 transcript levels were significantly higher than in the wild type at stage 11. This delayed expression of MYB26 in arf8-7 stamens suggests that ARF8 controls MYB26 temporal expression and is consistent with the effect of the ARF8.4 variant on the timing of endothecium lignification.

To seek evidence for a specific role of the splice variant ARF8.4 in the regulation of MYB26 expression, we introduced a GUS transcriptional fusion driven by the MYB26 promoter (ProMYB26:GUS) into ARF8.2ox and ARF8.4ox plants, as well as ARF8.2oxARF8.4ox (Supplemental Figures 8A to 8D), and compared MYB26 expression in anthers at different developmental stages. As shown in Figure 6D, in anthers of all types of plants, MYB26 expression was detected in the tapetum, middle layer, and endothecium. In estradiol-treated ARF8.2ox-ProMYB26:GUS as well as mock-treated (Supplemental Figure 8E) and ProMYB26:GUS (Cecchetti et al., 2013) anthers, ProMYB26:GUS activity was visible at stage 10. In contrast, in ARF8.4ox-ProMYB26:GUS and ARF8.2oxARF8.4ox-ProMYB26:GUS anthers, MYB26 expression was detected at stage 9 (Figures 6D and 6E) but with a stronger signal in the latter, specifically localized in the tapetum. These results suggest that ARF8.2 has a minor effect on MYB26 expression, apparently limited to tapetal cells, while the regulation of MYB26 in the endothecium is controlled by the splice variant ARF8.4.

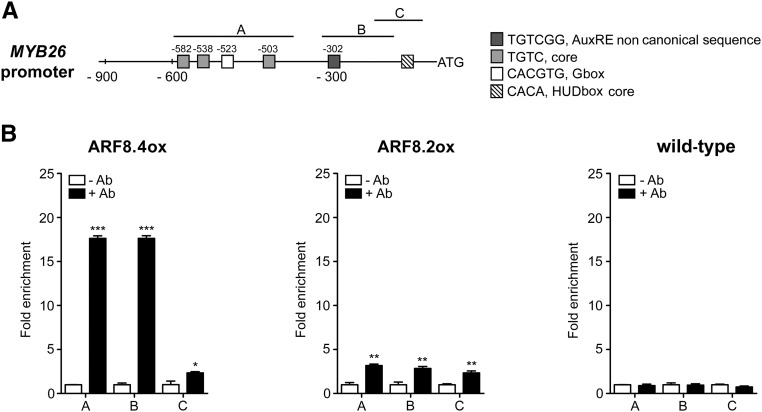

To assess whether ARF8.4, and possibly also ARF8.2, binds in vivo to the MYB26 promoter, we performed a ChIP-qPCR assay. The promoter of MYB26 contains three regions that are enriched in auxin-related cis-elements, as shown in Figure 7A: region C (from −91 to −215), which contains a core HUD box (Michael et al., 2008); region B (from −127 to −315), which contains the AuxRE variant TGTCGG (Boer et al., 2014); and region A, which contains a G-box and three AuxRE core sequences (from −383 to −560).

Figure 7.

ARF8.4 Directly Binds MYB26 Promoter.

(A) Schematic diagram of putative ARF binding sites in the MYB26 promoter (900 bp from the transcription start site). The upper black lines indicate fragments amplified in ChIP-qPCR assays.

(B) Chromatin immunoprecipitation analysis of ARF8.4 and ARF8.2 binding to the MYB26 promoter. A very high fold enrichment was observed in regions A and B in ARF8.4-overexpressing inflorescences and a very low fold enrichment was observed in all three regions in ARF8.2-overexpressing inflorescences. ChIP-qPCR values are means ± se of nine data points obtained from three biological replicates that were each analyzed in triplicate. Biological replicates were obtained by pooling inflorescences isolated from 50 independently grown plants for each genotype. Asterisks indicate a significant difference from the -Ab control value: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001. Ab, antibody.

This analysis, utilizing primers for all three regions (Supplemental Table 1), showed that ARF8.4 directly binds with high efficiency to different regions of the MYB26 promoter containing noncanonical AuxRE (TGTCGG) + or G-box (CACGTG), while ARF8.2 binds to the same regions with a much lower efficiency in accordance to its weaker effect on MYB26 expression (Figure 7B).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we report the identification and functional analysis in Arabidopsis of ARF8.4, a newly identified flower-specific splice variant of the auxin responsive transcription factor ARF8 (Nagpal et al., 2005). Different splice variants have been identified for several ARFs (see Table 2), but their functions have been unclear, with the exception of the truncated ΔARF4 variant that has been suggested to have a function distinct from the full-length ARF4 in carpel development (Finet et al., 2013).

Table 2. Putative Splice Variants Identified in ARF Coding Sequences (Araport 11 Genome Annotation).

| Locus | Gene Name | No. of CDS Splice Variants | AS Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| At1g59750 | ARF1 | 0 | – |

| At5g6200 | ARF2 | 1 | DS |

| At2g33860 | ARF3 | 1 | AFE |

| At5g60450 | ARF4 | 1 | RI |

| At1g19850 | ARF5 | 1 | AFE |

| At1g30330 | ARF6 | 0 | – |

| At5g20730 | ARF7 | 2 | AS; DS; DS |

| At5g37020 | ARF8 | 2 | AFE; DS |

| At4g23980 | ARF9 | 0 | – |

| At2g28350 | ARF10 | 1 | DS |

| At2g46530 | ARF11 | 2 | AS; DS; AFE |

| At1g34310 | ARF12 | 0 | – |

| At1g34170 | ARF13 | 2 | AFE; AS; DS |

| At1g35540 | ARF14 | 0 | – |

| At1g35520 | ARF15 | 0 | – |

| At4g30080 | ARF16 | 0 | – |

| At1g77850 | ARF17 | 1 | DS and ES |

| At3g61830 | ARF18 | 1 | AFE and ES |

| At1g19220 | ARF19 | 0 | – |

| At1g35240 | ARF20 | 0 | – |

| At1g34410 | ARF21 | 0 | – |

| At1g34390 | ARF22 | 0 | – |

| At1g43950 | ARF23 | 0 | – |

Description of AS type (Graveley et al., 2011). DS, donor Site (alternative 5′ splice sites); AS, acceptor site (alternative 3′ splice site); AFE, alternative first exon (different ATG start codon site); IR, intron retention; ES, exon skipping. CDS, coding sequence.

ARF8.4 bears a premature stop codon, similar to the splice variant ARF8.2 (TAIR 2010), but exhibits in-frame intron retention, leading to a 28-amino acid L-rich sequence inserted in the transcriptional activation MR. Here, we show that the intron retained in ARF8.4 has the major characteristics of an exitron, a recently identified class of exon-like introns that can be spliced and contribute substantially to proteome diversity in plants and animals (Marquez et al., 2015).

Exitron-retaining splice variants in Arabidopsis are generally expressed in a tissue-specific manner and translated into a protein, and the intron sequence is conserved in homologs of other Arabidopsis accessions (Marquez et al., 2015). By RT-PCR, qRT-PCR, and in situ hybridization analysis, we showed that ARF8.4 is expressed at the same developmental stages as the two known splice variants, ARF8.1 and ARF8.2, with different tissue-specific localization patterns, and at low levels in both flower buds and stamens. The ARF8.4 transcript is mainly localized in anther tissues surrounding the locules, where ARF8.1 and ARF8.2 transcripts are barely detectable, while in the anther procambium, ARF8.4 is detectable at later flower developmental stages than the two other variants. This is in agreement with a previous in situ analysis performed with probes unable to distinguish between individual splice variants, showing a faint signal in tissues surrounding the locules at stages 9-10 and a strong signal at stages 10-11 in stamen vascular tissue (Goetz et al., 2006; Wu et al., 2006; Rubio-Somoza and Weigel, 2013). By expressing GFP/RFP fusion proteins in tobacco epidermal cells, we demonstrated that ARF8.4 is translated, and its product is efficiently transported into the nucleus, as expected for a transcription factor. In addition, by performing evolutionary analysis, we showed that the intron 8 sequence is conserved in other Arabidopsis accession, corroborating the notion that ARF8.4 is a functional splice variant.

By analyzing the phenotype of the arf8-7 mutant (Gutierrez et al., 2012) and of lines overexpressing each single ARF8 splice variant, and by means of arf8-7 transcriptome analysis and qRT-PCR, we demonstrated that ARF8.4 plays a major role in stamen elongation and that it acts via induction of the master regulator gene of auxin-mediated stamen filament elongation, AUX/IAA19 (Tashiro et al., 2009; Cecchetti et al., 2017). Using estradiol-inducible constructs, we showed that ARF8.4 is the only ARF8 splice variant whose expression fully restores filament elongation in arf8-7 stamens, as well as inducing an increase in stamen length in wild-type flowers. In addition, an increased expression of AUX/IAA19 was observed when we expressed ARF8.4 in flowers of arf8-7, which have reduced levels of AUX/IAA19 transcript. Accordingly, the expression of AUX/IAA19 in wild-type stamens is localized to anthers at stage 11 (Tashiro et al., 2009), when filament elongation occurs and when we detected ARF8.4 transcript. Using ChIP-qPCR, we showed that ARF8.4 directly regulates AUX/IAA19 by binding to the canonical AuxRE (TGTCTC) and to the HUD and G-boxes in its promoter, which are found in most auxin-responsive promoters (Walcher and Nemhauser, 2012). Interestingly, AUX/IAA19 also controls cell elongation during hypocotyl growth (Oh et al., 2014).

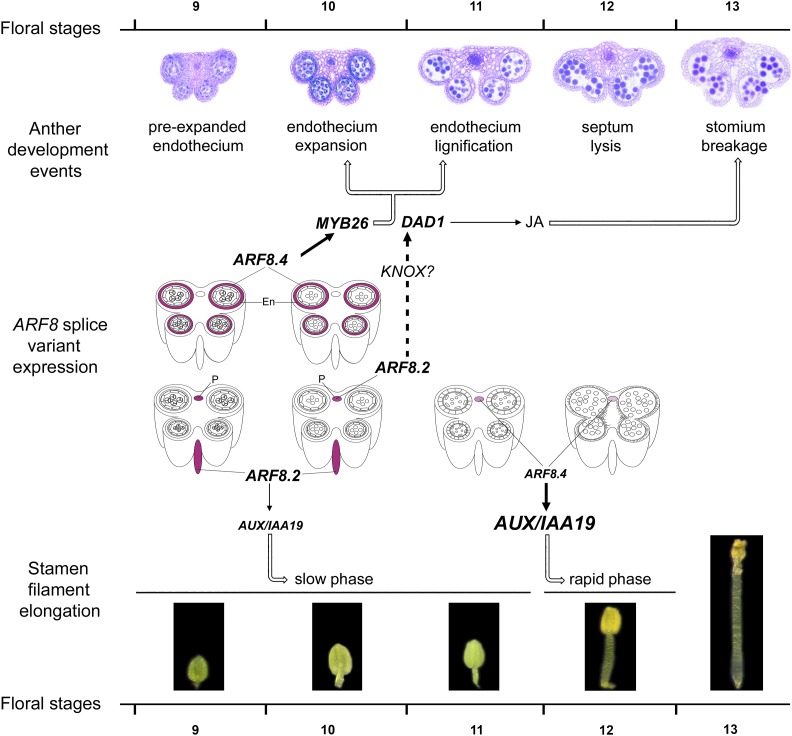

We also detect a minor effect of ARF8.2: Its expression induced the limited elongation of stamen filaments and a slight increase in AUX/IAA19 expression in the arf8-7 background. In agreement with its minor regulatory role, ARF8.2 binds less efficiently to the AUX/IAA19 promoter elements and consequently is much less effective in activating transcription compared with ARF8.4. The different quantitative effects of the inducible expression of ARF8.2 and ARF8.4 on stamen elongation may reflect the specific physiological role of each splice variant in modulating the growth of Arabidopsis stamens. ARF8.2 expression possibly occurring at stages 9 and 10 may contribute to the slow phase of stamen growth, which takes place at stages 9 to 11, while ARF8.4 expression, occurring at later stages (11 and 12), may control the rapid phase of stamen growth that occurs at stages 11 to 13 (Cecchetti et al., 2008; Tashiro et al., 2009). In agreement with these observations, we found that ARF8.4 is specifically expressed in the anther procambium, which is crucial for stamen elongation (Cecchetti et al., 2007; Rubio-Somoza and Weigel, 2013).

By analyzing the phenotypes of arf8-7 stamens expressing each single ARF8 splice variant (or combination of them) via histological analysis and qRT-PCR, we demonstrated that ARF8.4 also plays a crucial role in anther dehiscence. Coexpression of ARF8.4 and ARF8.2, but not ARF8.2 and ARF8.1 or ARF8.4 and ARF8.1, in wild-type and arf8-7 lines caused precocious anther dehiscence. We showed that this is due to a combined effect on both the timing of endothecium lignification and on the production of JA, a hormone that regulates stomium opening (Ishiguro et al., 2001). Using histological fluorescence analysis, we determined that the expression of ARF8.4, but not of ARF8.2, led to precocious endothecium lignification, while ARF8.2 is mainly responsible for stomium opening. In fact, the inducible expression of ARF8.2 but not ARF8.4 induced an increase in the transcript level of the JA biosynthetic gene DAD1 (Tabata et al., 2010; Cecchetti et al., 2013). In addition, the ARF8.2 expression profile is consistent with that of DAD1, which is expressed in the anther procambium at stage 9 and in the stamen filament at stages 10 and 11 (Ito et al., 2007).

These results are in agreement with our previous observation that the early dehiscence of the auxin perception mutant afb1-3 and the triple mutant tir1 afb2 afb3 is due to premature endothecium lignification and is associated with increased expression of DAD1 (Cecchetti et al., 2013). Furthermore, our data are in good agreement with those of Nagpal et al. (2005), which suggest a key role for ARF8 in JA production, as well as with those of Tabata et al. (2010), which show that ARF8 (and ARF6) indirectly act on DAD1 to regulate JA production.

We showed that ARF8.4 controls endothecium lignification by regulating the expression of MYB26, a gene that mediates the control of this process by auxin (Cecchetti et al., 2013). Indeed, a transcriptional ProMYB26:GUS fusion was expressed earlier (stage 9) in the endothecium of ARF8.4-overexpressing anthers than in wild-type and ARF8.2 anthers, where GUS activity was detectable at stage 10. In addition, by performing a ChIP-qPCR assay, we showed that ARF8.4 binds to the HUD and G-boxes, as well as to the noncanonical AuxRE variant TGTCGG, in the MYB26 promoter.

We showed that coexpressing ARF8.4 and ARF8.2 confers, specifically in the tapetum, somewhat stronger GUS staining in stage 9 anthers compared with the expression of ARF8.4 alone, suggesting the regulatory activity of ARF8.2 on MYB26 is limited to this tissue. In agreement with this limited regulatory role, ARF8.2 binds to the same sequences in the MYB26 promoter as ARF8.4 but activates its transcription with a much lower efficiency. The binding of both ARF8 variants to the TGTCGG sequence is in good agreement with the previous finding that other ARF proteins such as ARF1, ARF5, and ARF6 bind very efficiently to this AuxRE variant sequence (Boer et al., 2014; Oh et al., 2014).

The proposed role for ARF8.4 in stamen development is schematically represented in the model shown in Figure 8, where MYB26 transcript is only shown in the endothecium, as this transcript is not functional in the tapetum (Yang et al., 2017). According to this model, the expression of ARF8.4 in the anther endothecium at stages 9 and 10 regulates the timing of endothecium lignification, and ultimately anther dehiscence, by directly activating MYB26. At the same stages (9 to 10), the expression of ARF8.2 in the stamen filament regulates (via DAD1) the JA production necessary for stomium opening and (via AUX/IAA19) the slow phase of stamen elongation. Subsequently, the expression of ARF8.4 in the anther procambium at stages 11 to 12 is responsible for the rapid elongation phase of the stamen filament via the direct activation of AUX/IAA19.

Figure 8.

Model Showing the Role of the Splice Variants ARF8.4 and ARF8.2 in Stamen Elongation and Anther Dehiscence during Late Arabidopsis Development.

Anther developmental events, stamen filament elongation phases, and relevant gene functions (MYB26, DAD1, and AUX/IAA19) from stages 9 to 13 (Bowman, 1994). ARF8.4 and ARF8.2 expression, as inferred from our in situ hybridization data, was simplified, only showing transcript localization in the endothecium and in the anther or stamen filament procambium. En, endothecium; P, procambium.

Further work is needed to establish what causes the increased binding of ARF8.4 protein to target genes compared with ARF8.2. One possible mechanism is that the insertion of the 22 intron 8-encoded amino acids very close to the DNA binding domain region required for ARF dimerization may alter the dimerization specificity of ARF8.4, thus affecting the strength of its binding to target sequences. Alternatively, the presence of the additional 22 amino acid residues encoded by intron 8 in the MR may alter this intrinsically disordered region of the ARF8.4 transcription factor, thus affecting its DNA binding affinity (Roosjen et al., 2018). In agreement with the latter possibility, intrinsically disordered regions have been detected in protein sequences encoded by exitrons (Marquez et al. 2015; Staiger and Simpson, 2015). One additional possibility, however, is that ARF8.2 is less efficiently transported into the nucleus than ARF8.4, as suggested by the cytosolic localization of the RFP signal in tobacco cells transformed with the RFP-ARF8.2 construct.

In conclusion, ARF8.4 is among the first examples of a transcription factor that regulates a developmental process via the tissue-specific expression of an exitron-containing splice variant. This may be a general mechanism in plant organ development, as it was recently shown that intron retention is the major type of alternative splicing in roots and that a minor isoform of the transcription factor AREB2 regulates root maturation (Li et al., 2016).

METHODS

Plant Material, Growth Conditions, and Sample Collection

The Arabidopsis thaliana ecotype Columbia (Col-0) and the arf8-7 mutant (Gutierrez et al., 2012), kindly provided by Catherine Bellini (Department of Plant Physiology, University of Umea), were used in this study. Stamens for RNA-seq analysis were collected according to flower bud size, immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C. Anthers or stamens collected to measure ARF8.1, ARF8.2, ARF8.4, MYB26, or AUX/IAA19 transcript levels by qRT-PCR were severed from flower buds, immediately frozen, and divided into four groups according to their stage as described before (Cecchetti et al., 2013). Plants were grown in a 16 h:8 h, light:dark cycle (light intensity 156 μmol m−2 s−1 using Osram L 36W 840 Lumilux Cool White Fluorescent tubes) at 24°C:21°C until flowering (4 weeks).

To induce ARF8.1, ARF8.2, and ARF8.4 expression, inflorescences were treated with 10 µM estradiol (Sigma-Aldrich) or the equivalent amount of solvent. Twenty-four hours after treatments, flower buds at stages 9, 10, 11, and 12 were collected for qRT-PCR analysis, and flowers at stage 14 were phenotypically analyzed.

Construct Preparation for Confocal Analysis and Agroinfiltration of Tobacco Leaves

The open reading frame of ARF8.4 splicing variant (with intron) was amplified with specific primers (Supplemental Table 1) including Gateway attachment sites (attB1/attB2) and with or without the stop codon. A subsequent BP reaction in pDONR221 (Invitrogen) yielded two different Entry clones. The compatible binary vectors of the Gateway system were acquired from VIB. To generate the final constructs, each Entry clone was recombined with an appropriate pDest vector trough LR reaction (Invitrogen). Vectors pDest pK7WGF2 (N-terminal fusion of GFP) or pK7FWG2 (C-terminal fusion of RFP) were used to generate GFP-ARF8.4 and ARF8.4-RFP. The resulting constructs were used to transform Agrobacterium tumefaciens GV3101 by heat shock in liquid nitrogen. The agroinfiltration protocol was described by Di Sansebastiano et al. (2004). Transformed and untransformed leaf tissue (80 mg) was collected and subjected to total RNA extraction, followed by reverse transcription (Cecchetti et al., 2017). Primers used for qRT-PCR analysis are listed in Supplemental Table 1.

RT-PCR Amplification and Cloning of ARF8 Splice Variants

Total RNA was extracted from 30 mg of flower buds at stages 9 and 10 and reverse transcribed as previously described (Cecchetti et al., 2017). Primers used for expression analysis are listed in Supplemental Table 1.

Amplified products obtained using primers ARF8.2 For and ARF8.2 Rev (indicated in Supplemental Table 1) were digested with XhoI and cloned in the XhoI site of the pBluescript II SK plasmid (Stratagene). Nucleotide sequences were determined for ∼20 recombinant clones.

The full-length nucleotide sequence of ARF8.1 was obtained using primers ARF8.2 For and ARF8.1Y Rev (indicated in Supplemental Table 1), cloned into the pGem-T Easy plasmid (Promega), and verified by sequence analysis.

Generation of Transgenic Plants

To generate ARF8.2ox and ARF8.4ox inducible transgenic lines, the coding sequences were isolated by digesting the pBluescript:ARF8.2 and pBluescript:ARF8.4 plasmids with SalI/ApaI, respectively, and the fragments were cloned into the XhoI/ApaI sites of the pER8 vector (Zuo et al., 2000). To generate inducible transgenic ARF8.1ox lines, the full-length coding sequence was obtained by digesting the pGem:ARF8.1 plasmid with BstXI/ApaI and cloning the fragment into the BstX/ApaI site of pER8:ARF8.2. Recombinant plasmids were confirmed by sequencing.

To generate FLAG-tagged ARF8.2 and ARF8.4 transgenic plants, the full-length ARF8.2 and ARF8.4 coding sequences were amplified from pER8:ARF8.2 (KpnI-AccIII) and pER8:ARF8.4, respectively (using the Gibson strategy) and cloned into the pENTR-3xHA-FLAG vectors. This plasmid was generated by cloning a region encoding the FLAG epitope flanked by the BamHI and KpnI restriction sites between the BamHI and KpnI sites of the vector pENTR-3xHA (Franciosini et al., 2013). The ARF8.2- and ARF8.4-FLAG fragments were recombined into the Gateway vector pH2GW7 containing the CaMV35S promoter (Karimi et al., 2002).

All constructs were introduced into Agrobacterium strain GV3101 and used to transform Arabidopsis Col-0 or arf8-7 plants by the floral dip method (Clough and Bent, 1998). Approximately 15 independent lines were generated per construct. The T1 hygromycin-resistant plants were self-fertilized, and homozygous lines were selected and used for the analyses. Primers are listed in Supplemental Table 1.

To generate ARF8.4ox-ProMYB26:GUS and ARF8.2ox-ProMYB26:GUS lines, ARF8.4ox- and ARF8.2ox-lines were transformed with an Agrobacterium GV3101 strain containing the ProMYB26:GUS construct (Cecchetti et al., 2013). The T1 kanamycin-resistant plants were self-fertilized, and homozygous lines were selected and used for the analyses.

Coexpressing lines in the wild-type and arf8-7 background were produced by crossing with either ARF8.1ox, ARF8.2ox, and ARF8.4ox lines or ARF8.1ox-arf8, ARF8.2ox-arf8, and ARF8.4ox-arf8 lines. F1 lines heterozygous for each parental construct were used for the analyses. Coexpressing lines containing the ProMYB26:GUS construct were produced by crossing ARF8.2ox-ProMYB26:GUS with ARF8.4ox-ProMYB26:GUS, and lines ARF8.2oxARF8.4ox-ProMYB26:GUS were used for the analyses.

RNA Isolation, Sequencing, and Data Mining

Total RNA was extracted from 600 stamens at stages 10-11-12 severed from flowers and pooled together using an RNeasy Plant Mini kit (Qiagen). Yields were estimated by electrophoretic and spectrophotometric analyses (NanoDrop 2000; Thermo Scientific). The RNA integrity number (RIN > 6.5, 28S/18S > 1.0) was verified using a BioAnalyzer 2100 (Agilent Technologies). Illumina TruSeq cDNA libraries were prepared and sequenced in 50-bp paired-end on an Illumina HiSeq 2000 platform. Two biological replicates were analyzed for each genotype with each amplification, yielding between 40 and 46 million raw sequencing reads. Biological replicates were obtained by pooling stamens isolated from 20 independently grown plants for each genotype.

The paired-end reads were aligned to the TAIR10 reference transcriptome (comprehensive for the splicing isoforms) using Bowtie2.2.7. The Bowtie output was elaborated by Samtools 0.1.19 (http://samtools.sourceforge.net) to obtain the number of mapped reads for each gene. The expression level of each transcript was measured by the RPKM (number of reads per kilobase per million reads) method.

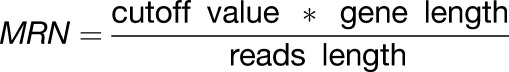

To identify differentially expressed genes (DEGs), a customized pipeline with very strict parameters was designed (Supplemental Figure 9). First, 5× gene coverage was imposed as a minimum cutoff to pass to the subsequent step of the analysis. The minimum reads number (MRN) to pass the cutoff was calculated with the following equation:

|

For example, to pass the 5× cutoff, a 1000-bp gene needed at least 100 reads that align on it. Genes were called “present” when they passed the 5× coverage cutoff, while genes below the threshold were called “absent.” Only the genes that were called “present” in both wild-type and arf8-7 repetitions, or called “present” in both wild-type repetitions and “absent” in both arf8-7 repetitions or vice versa passed to the subsequent steps of the analysis. In the second step, to determine DEGs, the minimum fold change (MFC) was calculated with the following equation:

|

where the minimum RPKM value (MinRPKM) between the two arf8-7 repetitions was divided by the maximum RPKM value (MaxRPKM) of the two wild-type repetitions. Only the genes that had a MFC ≥ 1.7 were considered differentially expressed.

The DEGs were annotated using the TAIR10 (www.arabidopsis.org) gene annotation; Gene Ontology terms enrichment and pathway discovery analyses were performed by EXPath (http://expath.itps.ncku.edu.tw/enrichment/arabidopsis/enrichment_analysis.php).

qRT-PCR Analysis

Total RNA was extracted using an RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen) according to manufacturer’s instructions from 50 mg of flower buds or 120 anthers/stamens at the indicated developmental stages or from five inflorescences and subsequently reverse transcribed. SYBR Green-based quantitative assays were performed as previously described (Cecchetti et al., 2017). Relative expression levels were normalized with that of the ACTIN8 (ACT8) housekeeping gene. cDNAs were amplified using the primers listed in Supplemental Table 1. All quantifications were performed in triplicate.

Morphological, Histological, and Cytological Analysis

Twenty flower buds for each genotype were collected at stage 14 of development and petals removed to measure stamen filament length. Images were acquired under a stereomicroscope (Carl Zeiss) equipped with a ProGres C3 digital camera and filament length measured using ProGres CapturePro v2.6 software (Jenoptik). Inflorescences were embedded in Technovit 7100 (Kulzer), and 8-μm transverse and longitudinal sections were photographed to examine anther lignin autofluorescence.

GUS Analysis

Three independent ARF8.4ox-ProMYB26:GUS, ARF8.2ox-ProMYB26:GUS, and ARF8.4oxARF8.2ox-ProMYB26:GUS lines were used for GUS analysis. Four estradiol-treated or mock-treated inflorescences from five different plants for each genotype were collected, and GUS analysis was performed as previously described (Cecchetti et al., 2008). Microscopy sections were prepared from GUS stained flower buds (see below) and 10-µm sections were photographed.

Statistical Analysis

Two-tailed Student’s t tests were used to evaluate statistical significance. All statistical analyses were performed using Graph Pad Prism 5 (Graph Pad Software).

RNA in Situ Hybridization

In situ hybridization with digoxigenin-labeled probes was performed on 8-µm longitudinal paraffin sections of Arabidopsis inflorescences as described by Ferrándiz et al. (2000), except that detection of hybridized transcripts was performed using a 1:250 dilution of antidigoxigenin Fab fragment (Boeringer). RNA antisense and sense probes were generated from flower buds cDNAs using the primers indicated in Supplemental Table 1 to amplify ARF8 and ARF8.4-specific fragments 159 and 150 bp long, respectively. cDNA fragments were cloned into the vector pGEM using the cloning kit pGEM-T Easy Vector (Promega) and verified by sequencing. Hybridization was performed at 50°C and the signal revealed by a purple/violet precipitate.

ChIP-qPCR Assay

The ChIP-qPCR procedure was performed on 35-d-old inflorescence as described by Haring et al. (2007) with some modifications. Flower bud tissue (300–600 mg) was cross-linked to DNA with formaldehyde. The chromatin was sonicated to obtain an average DNA fragments size between 0.3 and 0.8 kb. The sonication efficiency was checked.

Ten micrograms (diluted 1/1000) of anti-FLAG antibody (Sigma-Aldrich F3165-2mg) was added to the chromatin solution to bind the target. ChIP-qPCR products were used for qRT-PCR using primers listed in Supplemental Table 1. Three independent biological replicates were performed for statistical significance.

Protein Extraction and Immunoblot Analyses

For all experiments with Arabidopsis plant extracts, proteins were extracted in IP buffer as described by Serino et al. (2003). ARF8.2- and ARF8.4-FLAG were detected with monoclonal antibodies to FLAG (see above). Crude extracts were then prepared according to Lee et al. (2009) and subjected to immunodetection.

Accession Numbers

Sequence data from this article can be found in the Arabidopsis Genome Initiative or GenBank/EMBL databases under the following accession numbers: ARF8.1, At5g37020.1; ARF8.2, At5g37020.2; AUX/IAA19, At3g15540; and MYB26, At3g13890. RNA-seq data sets have been stored in the National Center for Biotechnology Information Sequence Read Archive database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) under BioProject accession number PRJNA383483.

Supplemental Data

Supplemental Figure 1. Sequence analysis of ARF8.4 showing the retention of an intron between exons 8 and 9.

Supplemental Figure 2. RNA in situ hybridizations of ARF8.4 and ARF8, localization of ARF8.4-GFP and ARF8.4-RFP fusions, and comparative analysis of ARF8.4 and ARF8.2 transcript levels in agroinfiltrated Nicotiana tabacum epidermal cells.

Supplemental Figure 3. arf8-7 shows a low level of ARF8 transcripts, and ARF8.1, ARF8.2, and ARF8.4 splice variants are expressed in ARF8.1ox, ARF8.2ox, and ARF8.4ox estradiol-treated inflorescences.

Supplemental Figure 4. Stamen and epidermal cell length of ARF8.1ox-arf8, ARF8.2ox-arf8, and ARF8.4ox-arf8 stamens from mock-treated flowers.

Supplemental Figure 5. Protein gel blot analysis showing the presence of expressed ARF8.4-FLAG and ARF8.2-FLAG recombinant proteins.

Supplemental Figure 6. Anther dehiscence has normal timing in mock- and estradiol-treated flowers from ARF8.1ox, ARF8.2ox, ARF8.4ox, ARF8.1ox-arf8, ARF8.2ox-arf8, and ARF8.4ox-arf8 lines and from ARF8.1oxARF8.2ox-arf8 and ARF8.1oxARF8.4ox-arf8 coexpressing lines.

Supplemental Figure 7. Endothecium lignification has normal timing in wild-type and mock-treated flowers from ARF8.1ox-arf8, ARF8.2ox-arf8, and ARF8.4ox-arf8 lines and from ARF8.2oxARF8.4ox-arf8 and ARF8.2oxARF8.4ox coexpressing lines.

Supplemental Figure 8. Molecular analysis by genomic PCR of ARF8.2ox-ProMYB26:GUS, ARF8.4ox-ProMYB26:GUS, and ARF8.2oxARF8.4ox-ProMYB26:GUS lines, and ProMYB26:GUS activity in ARF8.2ox anthers.

Supplemental Figure 9. Pipeline used to detect DEGs.

Supplemental Table 1. List of primers used in this study.

Supplemental File 1. Alignment used to compare the Columbia intron 8 sequence to that of the other Arabidopsis accessions to identify a possible functional single nucleotide polymorphism.

Acknowledgments

This work was partially supported by a research grant to M.C. and G.S from the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Direzione Generale per la Promozione del Sistema Paese) and by a research grant to P.C. and M.C. from the Italian Ministry of Education, University and Research (Progetti di Ricerca di Interesse Nazionale). We thank Giulia Galotto for technical assistance.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

M.C. designed the research and interpreted results. R.G., P.B., and N.N. performed the research and contributed to result interpretation. A.D.P., M.M., and G.A.P. performed experiments and contributed to result interpretation. V.C., F.B., and G.R. performed experiments. G.M. performed bioinformatic analysis. G.S. and T.T. contributed to experimental design. M.C. and P.C. wrote the manuscript.

References

- Boer D.R., Freire-Rios A., van den Berg W.A., Saaki T., Manfield I.W., Kepinski S., López-Vidrieo I., Franco-Zorrilla J.M., de Vries S.C., Solano R., Weijers D., Coll M. (2014). Structural basis for DNA binding specificity by the auxin-dependent ARF transcription factors. Cell 156: 577–589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowman J. (1994). Arabidopsis: An Atlas of Morphology and Development. (New York: Springer-Verlag; ). [Google Scholar]

- Cecchetti V., Celebrin D., Napoli N., Ghelli R., Brunetti P., Costantino P., Cardarelli M. (2017). An auxin maximum in the middle layer controls stamen development and pollen maturation in Arabidopsis. New Phytol. 213: 1194–1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cecchetti V., Altamura M.M., Brunetti P., Petrocelli V., Falasca G., Ljung K., Costantino P., Cardarelli M. (2013). Auxin controls Arabidopsis anther dehiscence by regulating endothecium lignification and jasmonic acid biosynthesis. Plant J. 74: 411–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cecchetti V., Altamura M.M., Falasca G., Costantino P., Cardarelli M. (2008). Auxin regulates Arabidopsis anther dehiscence, pollen maturation, and filament elongation. Plant Cell 20: 1760–1774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cecchetti V., Altamura M.M., Serino G., Pomponi M., Falasca G., Costantino P., Cardarelli M. (2007). ROX1, a gene induced by rolB, is involved in procambial cell proliferation and xylem differentiation in tobacco stamen. Plant J. 49: 27–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng C.Y., Krishnakumar V., Chan A.P., Thibaud-Nissen F., Schobel S., Town C.D. (2017). Araport11: a complete reannotation of the Arabidopsis thaliana reference genome. Plant J. 89: 789–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung H.S., Howe G.A. (2009). A critical role for the TIFY motif in repression of jasmonate signaling by a stabilized splice variant of the JASMONATE ZIM-domain protein JAZ10 in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 21: 131–145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clough S.J., Bent A.F. (1998). Floral dip: a simplified method for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 16: 735–743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Sansebastiano G.P., Rizzello F., Durante M., Caretto S., Nisi R., De Paolis A., Faraco M., Montefusco A., Piro G., Mita G. (2015). Subcellular compartmentalization in protoplasts from Artemisia annua cell cultures: engineering attempts using a modified SNARE protein. J. Biotechnol. 202: 146–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Sansebastiano G.P., Renna L., Piro G., Dalessandro G. (2004). Stubborn GFPs in Nicotiana tabacum vacuoles. Plant Biosyst. 138: 37–42. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrándiz C., Liljegren S.J., Yanofsky M.F. (2000). Negative regulation of the SHATTERPROOF genes by FRUITFULL during Arabidopsis fruit development. Science 289: 436–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finet C., Berne-Dedieu A., Scutt C.P., Marlétaz F. (2013). Evolution of the ARF gene family in land plants: old domains, new tricks. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30: 45–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franciosini A., et al. (2013). The Arabidopsis COP9 SIGNALOSOME INTERACTING F-BOX KELCH 1 protein forms an SCF ubiquitin ligase and regulates hypocotyl elongation. Mol. Plant 6: 1616–1629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graveley B.R., et al. (2011). The developmental transcriptome of Drosophila melanogaster. Nature 471: 473–479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goetz M., Vivian-Smith A., Johnson S.D., Koltunow A.M. (2006). AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR8 is a negative regulator of fruit initiation in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 18: 1873–1886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guilfoyle T.J., Hagen G. (2007). Auxin response factors. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 10: 453–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez L., Mongelard G., Floková K., Pacurar D.I., Novák O., Staswick P., Kowalczyk M., Pacurar M., Demailly H., Geiss G., Bellini C. (2012). Auxin controls Arabidopsis adventitious root initiation by regulating jasmonic acid homeostasis. Plant Cell 24: 2515–2527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez L., Bussell J.D., Pacurar D.I., Schwambach J., Pacurar M., Bellini C. (2009). Phenotypic plasticity of adventitious rooting in Arabidopsis is controlled by complex regulation of AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR transcripts and microRNA abundance. Plant Cell 21: 3119–3132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haring M., Offermann S., Danker T., Horst I., Peterhansel C., Stam M. (2007). Chromatin immunoprecipitation: optimization, quantitative analysis and data normalization. Plant Methods 3: 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y., Han Y.T., Wei W., Li Y.-J., Zhang K., Gao Y.-R., Zhao F.-L., Feng J.Y. (2015). Identification, isolation, and expression analysis of heat shock transcription factors in the diploid woodland strawberry Fragaria vesca. Front. Plant Sci. 6: 736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishiguro S., Kawai-Oda A., Ueda J., Nishida I., Okada K. (2001). The DEFECTIVE IN ANTHER DEHISCIENCE gene encodes a novel phospholipase A1 catalyzing the initial step of jasmonic acid biosynthesis, which synchronizes pollen maturation, anther dehiscence, and flower opening in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 13: 2191–2209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito T., Ng K.H., Lim T.S., Yu H., Meyerowitz E.M. (2007). The homeotic protein AGAMOUS controls late stamen development by regulating a jasmonate biosynthetic gene in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 19: 3516–3529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karimi M., Inzé D., Depicker A. (2002). GATEWAY vectors for Agrobacterium-mediated plant transformation. Trends Plant Sci. 7: 193–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J., Harter K., Theologis A. (1997). Protein-protein interactions among the Aux/IAA proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94: 11786–11791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H.K., Cho S.K., Son O., Xu Z., Hwang I., Kim W.T. (2009). Drought stress-induced Rma1H1, a RING membrane-anchor E3 ubiquitin ligase homolog, regulates aquaporin levels via ubiquitination in transgenic Arabidopsis plants. Plant Cell 21: 622–641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S., Yamada M., Han X., Ohler U., Benfey P.N. (2016). High-resolution expression map of the Arabidopsis root reveals alternative splicing and lincRNA regulation. Dev. Cell 39: 508–522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Yu X., Liu S., Peng H., Mijiti A., Wang Z., Zhang H., Ma H. (2017). A chickpea NAC-type transcription factor, CarNAC6, confers enhanced dehydration tolerance in Arabidopsis. Plant Mol. Biol. Report. 35: 83–96. [Google Scholar]

- Marquez Y., Höpfler M., Ayatollahi Z., Barta A., Kalyna M. (2015). Unmasking alternative splicing inside protein-coding exons defines exitrons and their role in proteome plasticity. Genome Res. 25: 995–1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michael T.P., Breton G., Hazen S.P., Priest H., Mockler T.C., Kay S.A., Chory J. (2008). A morning-specific phytohormone gene expression program underlying rhythmic plant growth. PLoS Biol. 6: e225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagpal P., Ellis C.M., Weber H., Ploense S.E., Barkawi L.S., Guilfoyle T.J., Hagen G., Alonso J.M., Cohen J.D., Farmer E.E., Ecker J.R., Reed J.W. (2005). Auxin response factors ARF6 and ARF8 promote jasmonic acid production and flower maturation. Development 132: 4107–4118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh E., Zhu J.Y., Bai M.Y., Arenhart R.A., Sun Y., Wang Z.Y. (2014). Cell elongation is regulated through a central circuit of interacting transcription factors in the Arabidopsis hypocotyl. eLife 3: e03031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remington D.L., Vision T.J., Guilfoyle T.J., Reed J.W. (2004). Contrasting modes of diversification in the Aux/IAA and ARF gene families. Plant Physiol. 135: 1738–1752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roosjen M., Paque S., Weijers D. (2018). Auxin Response Factors-output control in auxin biology. J. Exp. Bot. 69: 179–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubio-Somoza I., Weigel D. (2013). Coordination of flower maturation by a regulatory circuit of three microRNAs. PLoS Genet. 9: e1003374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]