Abstract

Social isolation is a strong predictor of early all-cause mortality and consistently increases breast cancer risk in both women and animal models. Because social isolation increases body weight, we compared its effects to those caused by a consumption of obesity-inducing diet (OID) in C57BL/6 mice. Social isolation and OID impaired insulin and glucose sensitivity. In socially isolated, OID-fed mice (I-OID), insulin resistance was linked to reduced Pparg expression and increased neuropeptide Y levels, but in group-housed OID fed mice (G-OID), it was linked to increased leptin and reduced adiponectin levels, indicating that the pathways leading to insulin resistance are different. Carcinogen-induced mammary tumorigenesis was significantly higher in I-OID mice than in the other groups, but cancer risk was also increased in socially isolated, control diet-fed mice (I-C) and G-OID mice compared with that in controls. Unfolded protein response (UPR) signaling (GRP78; IRE1) was upregulated in the mammary glands of OID-fed mice, but not in control diet-fed, socially isolated I-C mice. In contrast, expression of BECLIN1, ATG7 and LC3II were increased, and p62 was downregulated by social isolation, indicating increased autophagy. In the mammary glands of socially isolated mice, but not in G-OID mice, mRNA expressions of p53 and the p53-regulated autophagy inducer Dram1 were upregulated, and nuclear p53 staining was strong. Our findings further indicated that autophagy and tumorigenesis were not increased in Atg7+/− mice kept in social isolation and fed OID. Thus, social isolation may increase breast cancer risk by inducing autophagy, independent of changes in body weight.

Keywords: breast cancer, social isolation, autophagy

Introduction

A potential role for stress in breast cancer etiology has been studied extensively in both human populations and animal models. Although some evidence supports a link (Lillberg et al. 2003), most human studies have failed to establish a connection (Achat et al. 2000) and some suggest a reduction in risk (Nielsen et al. 2005). Findings from animal studies are equally contradictory, with one type of stress increasing and another reducing cancer risk (Hilakivi-Clarke et al. 1994). An exception is social isolation stress that consistently elevates cancer risk and mortality. People who are socially isolated have a worse prognosis and are more likely to die from cancer including breast cancer than their socially integrated counterparts (Berkman et al. 2004, Kroenke et al. 2006). Animal studies show that social isolation stress increases the risk of colon cancer (Wu et al. 1999), Ehrlich adenocarcinoma (Villano et al. 2001), hepatocarcinogenesis (Hilakivi-Clarke & Dickson 1995, Liu & Wang 2005) and mammary tumorigenesis (Marchant 1967, Grimm et al. 1996, Strange et al. 2000, Hermes et al. 2009, Williams et al. 2009). The adverse effects of social isolation on cancer risk and mortality are consistent with social isolation being an equally powerful predictor of early all-cause mortality such as smoking, obesity, elevated blood pressure or high cholesterol (Pantell et al. 2013).

Social isolation in humans is measured using validated questionnaires. Individuals are considered as being isolated if they exhibit high social disconnectedness including restricted social networks and social inactivity. High perceived isolation is associated with loneliness and lack of support (Sansoni et al. 2010). In 2004, almost 25% of people in the United States had no social discussion networks and the same percentile had no confidants (McPherson et al. 2006). The estimated rates of social isolation vary among different groups: for example, 10% of health professionals (McGuire et al. 1975) and up to 43% of elderly (Smith & Hirdes 2009, Nicholson 2012) can be considered as being socially isolated. Besides aging, the most common causes of social isolation are family violence or having experienced physical violence, being diagnosed with life-threatening illness, disabilities, loss of spouse, living alone and societal adversity caused by for example poverty, race or being LGBTQ (Cacioppo & Hawkley 2003, Parillo 2008). Causes of social isolation also include post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (PTSD: National Center for PTSD 2014) or being obese (Strauss & Pollack 2003, Lauder et al. 2006). In fact, social isolation in mice is shown to be a preclinical model of PTSD (Pinna 2010). Both obesity (van den Brandt et al. 2000) and PTSD are linked to increased breast cancer risk. Women who worked as nurses during the Vietnam War and developed PTSD were later 3-fold more likely to be diagnosed with breast cancer than nurses who did not develop PTSD (Vin-Raviv et al. 2014).

Stress is widely reported to increase the activation of the sympathetic nervous system, including increased release of catecholamines and activation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenocortical (HPA) axis that increases cortisol secretion. Social isolation also initiates a robust central nervous system and stress hormone reaction (Wirtz et al. 2006). However, the effects of social isolation are unlikely to be mediated through an increase in stress hormones because these changes are transient and normalize during chronic social isolation (Volden et al. 2013). Some studies have reported reduced glucocorticoid levels in chronically isolated animals (Nonogaki et al. 2007). Unlike many stressors that reduce food consumption and body weight, social isolation induces body weight gain in mice (Nonogaki et al. 2007) and in humans (Whisman 2010). An increase in neuropeptide Y (NPY) might be involved in causing this weight gain, as NPY is activated by some stressors and leads to weight gain in an animal model (Kuo et al. 2007, Nonogaki et al. 2007). A recent study found increased NPY levels in the hypothalamus of socially isolated juvenile male rats (Krolow et al. 2013). It is possible that obesity both leads to social isolation and mediates the increase in breast cancer risk seen in socially isolated individuals.

Metabolic abnormalities, including those caused by obesity, lead to endoplasmic reticulum (EnR) stress (Hosogai et al. 2007, Gregor et al. 2009, Chakrabarti et al. 2011). EnR is a central organelle in eukaryotic cells: it stores and regulates calcium release, synthesizes lipids and folds proteins emerging from the ribosome. EnR stress activates unfolded protein response (UPR) that is composed of three arms: PKR-like EnR regulation kinase (PERK), activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6) and inositol-requiring enzyme 1α (IRE1α), each regulated by the master UPR chaperone GRP78 (Parmar et al. 2013). Initially, the UPR functions as an adaptive response to maintain normal physiological functions and to protect the cells from irreversible damage. UPR further induces autophagy that can either eliminate cancer cells (Fulda et al. 2010, Clarke et al. 2012) or create energy for the cells to survive (Levine & Klionsky 2004). Autophagy is initiated by encapsulation of damaged cytoplasmic components, such as excess proteins, within double-membrane-bound vesicles called autophagosomes. When autophagosomes fuse with lysosomes, their contents are degraded, which contribute to cellular energy metabolism. Increased autophagy has been reported in many cancers (Chen & Karantza-Wadsworth 2009, Cook et al. 2011, Cha et al. 2014, Farrow et al. 2014, Lai et al. 2014, Ojha et al. 2014, Titone et al. 2014). Here we studied if social isolation mimics the effects of increased body weight on breast cancer risk and promotes UPR signaling and possibly autophagy.

Materials and methods

Animals

Three types of mice were used: female C57BL/6 mice obtained from Charles River, and Atg7+/− (Komatsu et al. 2005) and wild-type mice obtained from the International Mouse Strain Resource. Wild-type and Atg7+/− mice were in mixed background (C57BL/6 × CBA × FVB/N). Mice were housed in a temperature- and humidity-controlled room and were under a 12-h light-darkness cycle. All animal procedures were approved by the Georgetown University Animal Care and Use Committee and followed the National Institute of Health guidelines for the proper and humane use of animals in biomedical research.

Social isolation and obesity-inducing high-fat diet

At weaning on postnatal day 21, C57BL/6 mice were either group-housed (5 mice/cage) or introduced to social isolation by housing them singly, and then fed either an AIN93G control-based diet containing 17% energy from fat (Harlan Teklad, TD.09029) or an obesity-inducing high-fat diet (OID) containing 59% energy from fat (lard) (Harlan Teklad, TD.09030). The four groups were (i) group-housed mice consuming control diet (G-C), (ii) group-housed mice consuming OID (G-OID), (iii) socially isolated mice consuming control diet (I-C) and (iv) socially isolated mice consuming OID (I-OID). Studies performed using Atg7+/− mice and their wild-type littermates included only G-C and I-OID groups, and they were aged 28 days at the beginning of the study.

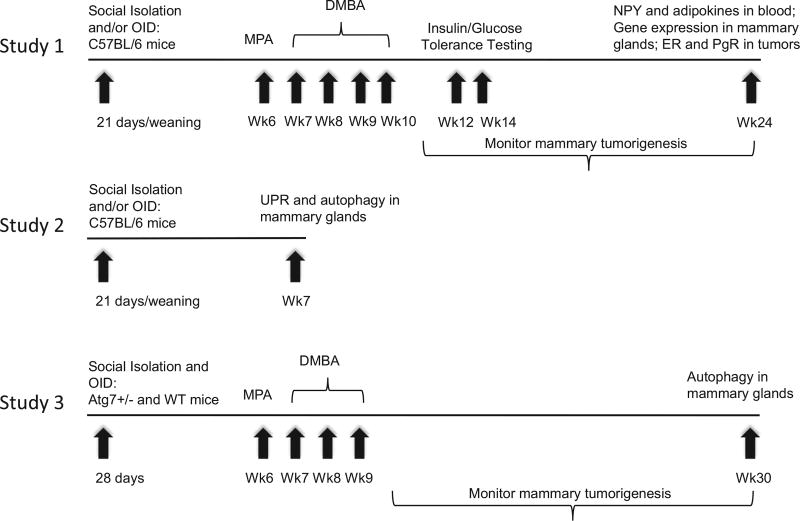

Three separate experiments were performed to study the effects of social isolation and OID. In the first study, their effects on metabolic markers and mammary tumorigenesis were assessed. The metabolic markers included p53 because it regulates metabolism (Puzio-Kuter 2011), is elevated by social isolation (Filipovic et al. 2011, Venna et al. 2014), and is required for social isolation to increase mammary tumorigenesis (Hasen et al. 2010). In the second study, the effects on UPR and autophagy were investigated in mice that were not given carcinogens. Finally, their effects on mammary tumorigenesis and autophagy in Atg7+/− mice were determined. Figure 1 summarizes the three experiments.

Figure 1.

Experimental design. Three separate experiments were performed to assess the effects of social isolation, with or without feeding mice obesity-inducing diet (OID), on mammary tumorigenesis and autophagy.

Experiment 1: effect of social isolation and OID on metabolic markers and mammary tumorigenesis

Mammary tumor induction

Mice were treated with a single subcutaneous dose of 15 mg of medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA, Pfizer) on postnatal week 6 and then exposed to 1 mg 7,12-dimethylbenz[a]anthracene (DMBA, Sigma) on weeks 7, 8, 9 and 10 by oral gavage to induce mammary tumors.

Weight gain and food consumption

Body weight was measured weekly in most, but not all, mice. Body weights in study 1 (Fig. 1) were recorded between weaning on week 3 and postnatal week 16. Body weights were also determined in study 2 from postnatal week 3 to week 7, and in study 3 from postnatal week 4 to 20. In a subgroup of mice (n = 5 cages/group) in study 1, food was weighed every 2–3 days for the first 3 weeks of exposures to OID and social isolation. Caloric intake was calculated using the caloric content of the diets.

Insulin and glucose tolerance testing

When DMBA-treated C57BL/6 mice were aged 12–14 weeks, we assessed the parameters linked to insulin resistance in 4–10 mice per group. None of these mice had tumors yet. After a 6-h fast, mice were injected intraperitoneally with 0.75 U/kg body weight of recombinant human insulin (Sigma) or 2 g/kg 20% glucose in molecular-grade water. Blood samples via tail vein puncture were taken at baseline (0 min) and 30, 60, 90 and 120 min after the insulin/glucose challenge. Blood glucose levels were measured using a FreeStyle portable glucose meter (TheraSense).

Monitoring mammary tumorigenesis

One week after the last DMBA administration, mice were palpated and mammary tumors were measured weekly with calipers. Mice were killed before the end of the monitoring period if the tumor burden exceeded 10% body weight. Otherwise, C57BL/6 mice were monitored for 13 weeks, after receiving the last DMBA dose and then killed. Tumor incidence, latency, multiplicity, size and growth were recorded. Tumor burden was calculated by assessing tumor length and width, obtained by using calibers. Numbers of C57BL/6 mice per group were the following: G-C: 21; G-OID: 19; I-C: 17 and I-OID: 15.

Tissue collection after tumor monitoring period

Blood was obtained via cardiac puncture at killing. Serum was separated, frozen and kept at −20°C until assayed. Mammary glands and tumors were collected at killing. Tissues were either fixed in 10% buffered formalin, embedded into paraffin blocks, sectioned (5 µm) or flash frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C until use.

Mammary tumor histopathology

Tumor sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin to determine histopathology, and classification was assessed by a trained pathologist.

Enzyme immunoassay (EIA)

Adiponectin (Millipore, EZMADP-60K) (n = 4–6/group) and Leptin (Millipore EZML-82K) (n = 7/group) EIAs were performed according to the manufacturer’s protocol. C18 Sep-column and buffers kit (Peninsula Laboratories, S-5000) were used to perform the extraction on the mouse serum samples in preparation for the NPY (Peninsula Laboratories S-1145) EIA by freeze-drying the eluent in a methanol/dry ice bath and then evaporating it with a centrifugal concentrator. Both the extraction and EIA for NPY were completed according to kit instructions (n = 7/group).

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) for Ki67 in mammary glands

Antigen retrieval was achieved using Tris/EDTA, pH 9.0 for 20 min at 100°C followed by a 20-min cooling period. Mammary gland sections (n = 4–7/group) were incubated in Ki67 primary antibody (Novus Biologicals, Littleton, CO, USA, NB600-1252) at a dilution of 1:40 for 1 h. Subsequently, the sections were incubated in HRP-rabbit secondary antibody (Dako, K4003) for 30 min, followed by DAB and counterstaining with hematoxylin. The protein buffer was used as a negative control. Scoring was based on percent-positive staining of the overall tissue.

TUNEL assay in mammary glands

Mammary gland tissue sections (n = 4–7/group) were deparaffinized with xylene and rehydrated through a series of descending graded ethanol. Tissues were then pretreated with 20 µg/mL proteinase K in PBS for 15 min, and then blocked in 3% H2O2 in PBS for 5 min. The ApopTag Plus Peroxidase In Situ Apoptosis Kit (Millipore, S7101) was then followed according to manufacturer’s protocol. Positive controls were included in the kit (Millipore, 90422). Negative controls were not treated with TdT enzyme (reaction buffer only). All washes were performed using Tris-buffered saline with Tween 20 (TBST). They were counterstained with 0.5% methyl green in 0.1 M sodium acetate, pH 4.0. Finally, these sections were washed in three changes of n-butanol for 30 s each, dehydrated in xylene and mounted with Permount. Scoring in the mammary glands was based on the percentage of cells that stained positive in the glands, with an average of six frames (with multiple glands per frame) assessed per slide.

IHC for ERα, PgR and p53

Mammary tumor tissue sections (n = 4–6/group for ERα; n = 9–17/group for PgR) or mammary glands (n = 6–11/group for p53) were deparaffinized with xylene and rehydrated through a series of descending graded ethanol. Antigen retrieval was achieved by microwaving in target retrieval solution citrate buffer, pH 6.0 (Dako, S2369) for 15 min with 20 min of cooling. Blocking was performed using 3% H2O2 in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) for 20 min. Tissue sections were incubated overnight at 4°C in primary antibodies ERα (Santa Cruz, H-184) at a dilution of 1:600, PgR (Dako, A0098) at a dilution of 1:400, or p53 (Cell Signaling, 9282) at a dilution of 1:200 in 3% bovine serum album (BSA) in TBST. A corresponding mouse primary antibody to IgG (Dako, X0931) was used for negative controls. Mouse uterus sections were stained concurrently as a positive control. The LSAB+ System-HRP, DAB+ kit (Dako, K0679) was used to develop the sections as instructed by the manufacturer, and they were counterstained with Harris Hematoxylin (Thermo Fisher Scientific). All washes were performed using TBST. The sections then went through ascending graded ethanol and xylene and mounted using Permount (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Quantification for ERα and PgR was performed by scoring intensity and percentage of positive cells modified from Allred and coworkers (1998). Nuclear p53 staining was assessed in mammary adipocytes by counting all cells per slide exhibiting nuclear staining or cytoplasmic staining. Photographs (40×) and score assessment for ERα, PgR, p53, TUNEL and Ki67 were all performed using brightfield microscopy on an Olympus BX61 with Image-Pro Plus (Media Cybernetics, Rockville, MD, USA) software.

Complementary DNA synthesis and quantitative real-time PCR analysis

Overall, 200 ng of total RNA per sample obtained from mammary glands of DMBA-exposed C57BL/6 mice were used as a template for random primed cDNA synthesis with a recombinant Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase via RNase Inhibitor – High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit with RNase Inhibitor (Life Technologies, 4374967), according to manufacturer’s instructions. An RT enzyme-minus control reaction was also included. The cDNA samples were then used as templates for quantitative real-time PCR analysis with specific primers for the target gene using EvaGreen 2X qPCR MasterMix-ROX (Applied Biological Materials Inc, Richmond, BC, Canada) and an ABI Prism 7900 Sequence Detection System. The primer sequences are shown in Supplementary Table 1, see section on supplementary data given at the end of this article. RNA for these assays was obtained from 4 to 7 mice per group. Each sample was run in triplicate. Absolute gene expression levels were determined using SDS2.3 software (Applied Biosystems) and the standard curve method. Concentration of each sample was normalized to the reference gene HPRT1.

Experiment 2: effect of social isolation and OID on UPR and autophagy

Western blot analysis for markers of UPR and autophagy in mammary glands

In a separate experiment, we investigated the changes in autophagy-related proteins Beclin 1, ATG7, LC3II and p62 in the mammary glands of mice that were not exposed to DMBA. We also investigated the levels of UPR signaling components GRP78, IRE1, PERK and CHOP. In this study, 40 C57BL/6 mice were divided to group-housed mice consuming control diet (G-C), group-housed mice consuming OID (G-OID), socially isolated mice consuming control diet (I-C) and socially isolated mice consuming OID (I-OID), with 10 mice in each group. Four weeks later, all mice were killed and their mammary glands were harvested, snap frozen and stored in −80°C until used for Western blot assays.

Snap-frozen tissues (n = 4–6 for each group) were ground and lysed in RIPA lysis buffer with protease inhibitor pellet (Roche Diagnostics) and 10 mM glycerophosphate (Sigma-Aldrich), 1 mM sodium orthovanadate (Sigma-Aldrich), 5 mM pyrophosphate (Sigma-Aldrich) and 1 mM PMSF (Sigma-Aldrich). The following primary antibodies were used in a 1:1000 dilution: anti-LC3II, ATG7, GRP78, IRE1, PERK, CHOP and Beclin 1 antibodies were from Cell Signaling Technology, anti-β-actin antibody was from Santa Cruz Biotechnology and anti-p62 antibody was obtained from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA, USA). Western blots were developed using chemiluminescent substrate (Denville Scientific, Metuchen, NJ, USA) and quantified with Quantity One software (Bio-Rad). For all Western blots, band intensity was normalized to β-actin.

Experiment 3: effect of social isolation and OID on Atg7+/− mice

Social isolation and obesity-inducing high-fat diet

Studies performed using Atg7+/− mice and their wild-type littermates included only G-C and I-OID groups, and they were aged 28 days at the beginning of the study.

Mammary tumor induction

Mice were treated with a single subcutaneous dose of 15 mg medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA, Pfizer) on postnatal week 6 and then exposed to 1 mg 7,12-dimethylbenz[a]-anthracene (DMBA, Sigma) on weeks 7, 8 and 9 by oral gavage to induce mammary tumors. Atg7+/− mice and their wild-type littermates were exposed to three doses of DMBA because our preliminary study indicated that four doses induced 100% incidence in the group-housed mixed background C57BL/6 mice (which does not allow the detection of a possible increase in mammary tumorigenesis by social isolation). Mammary tumorigenesis was assessed as described in Experiment 1. In this study, we had 19 group-housed wild-type and 16 group-housed Atg7+/− mice receiving control diet (G-C), and 18 wild-type and 20 Atg7+/− mice that were housed in social isolation and fed OID (I-OID).

Western blot analysis for markers of autophagy in mammary glands

LC3I, LC3II and p62 levels were also determined in the mammary glands of Atg7+/− mice (n = 4) and their wild-type littermates (n = 4). Mice in this study were those that had either been group-housed and fed control diet (G-C) or socially isolated and fed OID. All these mice had received MPA + DMBA, and their glands were obtained at the end of tumor monitoring period (20 weeks from the last DMBA dose).

Statistics

The Kaplan–Meier survival curve and log-rank test were used to compare the differences in mammary tumor incidence. In all the other analyses, two-way ANOVA was used to determine the statistically significant differences between the four groups with diet (control or OID) and social isolation (group or isolated housing) as variables. Two-way ANOVA also was used to compare the differences in wild-type and Atg7+/− mice to group housing and social isolation + OID. Pairwise multiple comparison procedures (Holm–Sidak method) were performed to determine post hoc differences when necessary. If data failed normality and/or equal variance tests, data were log transformed before analysis. Repeated-measures ANOVA was performed to determine if body weight gain was different among the groups in Experiment 3. All statistical analyses were carried out using SPSS SigmaStat software, and differences were considered significant if P was less than 0.05. All probabilities are two-tailed.

Results

Experiment 1

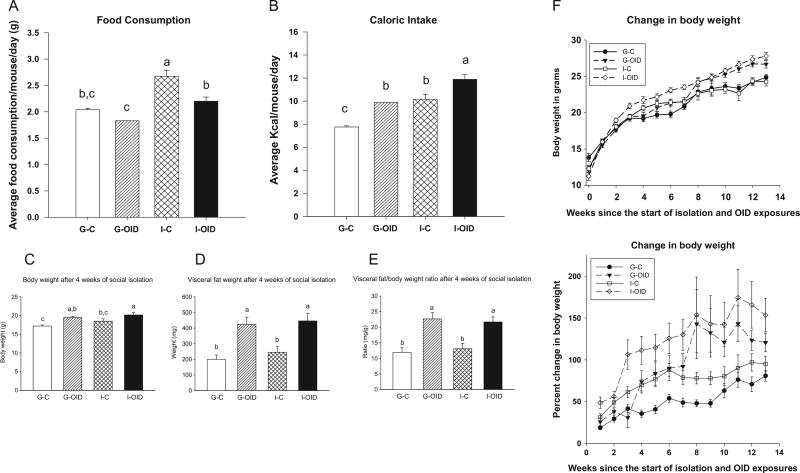

Caloric intake and body weight gain in C57BL/6 mice

As the obesity-inducing diet (OID) contains more energy than the control diet, mice on the control diet ate more grams of food than those on the OID during the first 3 weeks of the OID and social isolation exposures (P < 0.001) (Fig. 2A). The total energy intake was elevated in the OID-fed mice (P < 0.001) (Fig. 2B). Mice housed in social isolation ate more food than group-housed mice (P < 0.001) and consumed more kcal/day even when fed the control diet (P < 0.001). An additive effect was seen between OID and social isolation on caloric intake (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

Effect of OID and social isolation on food consumption, body weight and visceral fat weight. (A) Food consumption in mice that were group-housed and fed control diet (G-C), group-housed and fed obesity-inducing diet (G-OID), socially isolated and fed the control diet (I-C), and socially isolated and fed OID (I-OID). Consumption was measured by weighing the amount of food (g) in the cages every 2–3 days over the first three weeks of dietary and social isolation exposures (n = 5 cages/group). OID reduced food intake: P < 0.001 and social isolation increased it: P < 0.001. (B) Caloric intake (kcal) was calculated based on the amount of food consumed by these mice and the caloric content of the food. During the 3 weeks when measurements were done, both OID: P < 0.001 and social isolation: P < 0.001 increased kcal intake. (C) Body weight after 4 weeks of dietary and social isolation exposures (n = 8–12 mice per group). Body weight was higher by OID: P < 0.001 and social isolation: P = 0.048. (D) Visceral fat weight (epididymal fat pads) in the same mice as shown in (C); it was increased by OID: P < 0.001. (E) Ratio between visceral fat and body weight; it was increased by OID: P < 0.001. (F) Body weight gain from the start of OID and social isolation on week 3 until week 16 (n = 15–21 mice per group), shown as weight in grams per week and as a percentile change. Both measures indicated that body weights were increased by OID: P < 0.001 and social isolation: P < 0.001. In addition, interaction between OID and social isolation was significant (P < 0.001) and indicated that initially social isolation was more potent than OID in increasing body weight, but when G-OID group started to be significantly heavier than the control group, I-C group no longer was heavier than the controls. For details, see ‘Results’ section. Bars marked with different letters are significantly different from each other. Means and standard error of means (s.e.m.) are shown.

After 4 weeks of consuming OID and/or being socially isolated, body weights were significantly increased by OID (P < 0.001) and social isolation (P < 0.048) (Fig. 2C). Visceral fat depots (epididymal fat pads) also were heavier (Fig. 2D), and visceral fat:body weight ratio was increased by OID (P < 0.001) but not by social isolation (Fig. 2E). Figure 2F shows change in body weight between weaning on week 3 and week 16, either as weight in grams or as a percentage from baseline weight. When compared with the G-C control group, body weight gain was increased both by OID (P < 0.001) and social isolation (P < 0.001). In addition, there was a significant interaction between OID and social isolation in affecting body weight gain (P < 0.001). Post hoc analysis indicated that during weeks 4 and 5, the I-C, but not G-OID, group had significantly higher body weight than the G-C control group. During weeks 10 and 13, the G-OID group but not the I-C group was significantly heavier than the controls.

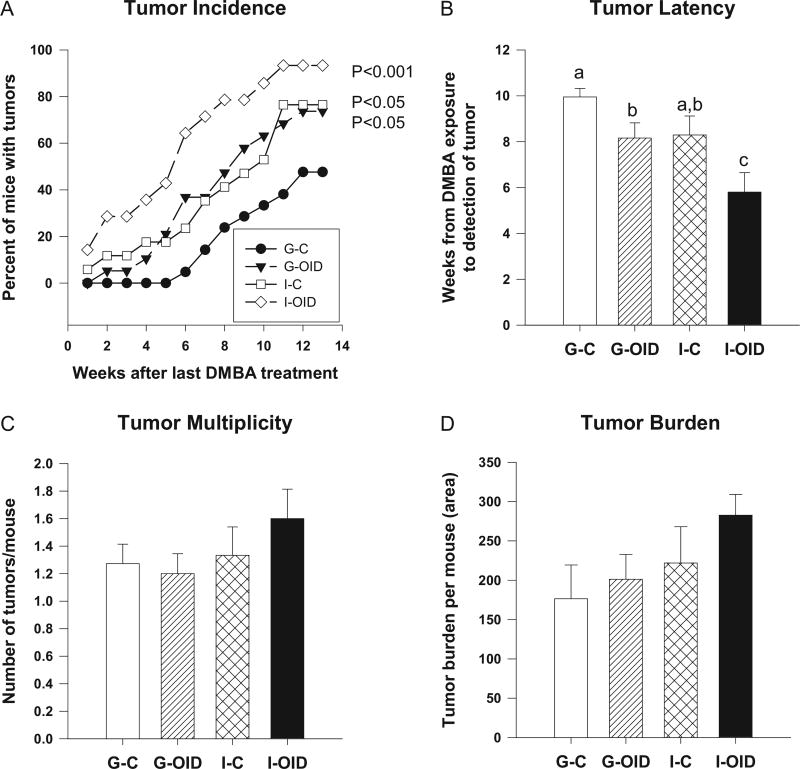

Mammary tumorigenesis in C57BL/6 mice

The socially isolated, OID-fed mice exhibited a significant increase in carcinogen-induced mammary tumor incidence (P < 0.001) and a shortened tumor latency (P = 0.002) compared with the other experimental groups (Fig. 3A and B). Social isolation in the control diet-fed mice increased tumor incidence at a rate similar to group-housed mice fed the OID, and tumor incidence was significantly higher in both groups than in the group-housed control mice (P < 0.05). Additionally, tumor latency was significantly shortened by OID (P = 0.004) (Fig. 3B). No differences were seen in tumor multiplicity (Fig. 3C). Despite a trend showing that social isolation combined with OID intake increased tumor burden, it was not significantly different among the groups due to a large within-group variation (Fig. 3D). Taken together, these data demonstrate that social isolation and OID both increased carcinogen-induced mammary carcinogenesis in female mice, and there was an additive effect between the two.

Figure 3.

Effect of OID and social isolation on mammary tumorigenesis. MPA + DMBA-induced mammary tumorigenesis in mice that were group-housed and fed the control diet (G-C), group-housed and fed obesity-inducing diet (G-OID), socially isolated and fed the control diet (I-C), and socially isolated and fed OID (I-OID) (n = 15–21/group). (A) Tumor incidence, assessed using log-rank test, was significantly higher in the I-OID mice compared with all other groups: P < 0.001, and in G-OID and I-C groups, compared with G-C control group: P < 0.05. (B) Tumor latency was significantly shortened by OID: P = 0.004 and by social isolation: P = 0.002. (C) Tumor multiplicity and (D) tumor burden were not affected. Bars marked with different letters are significantly different from each other. Means and standard error of means (s.e.m.) are shown.

Histopathology, ERα and PgR characterization of mammary tumors in C57BL/6 mice

Mammary tumors were examined by histopathology and all of them were malignant. Adenocarcinomas, some with squamous carcinoma cells and few with myoepithelioma cells were identified at the same proportion in the four groups. Histopathological tumor grade was also similar across the groups (Supplementary Table 2). All tumors in each group were ERα and PgR positive, and no differences in the expression of these receptors by OID or social isolation were seen (Supplementary Fig. 1).

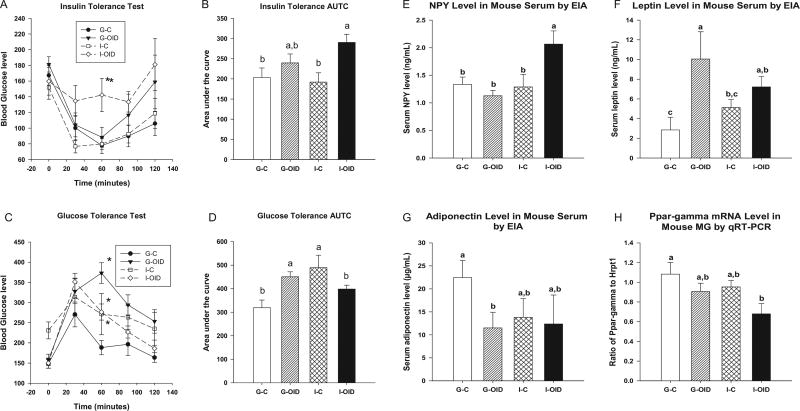

Insulin tolerance in C57BL/6 mice

In our study, only socially isolated OID-fed mice exhibited impaired insulin tolerance. These mice had significantly higher glucose levels at 60 min after insulin injection than the group-housed control mice (P = 0.015) (Fig. 4A). Similarly, the area under the curve (AUC) in the insulin tolerance test was significantly increased in socially isolated mice fed OID (P = 0.021) (Fig. 4B).

Figure 4.

Effect of OID and social isolation on insulin and glucose tolerance, and on neuropeptide Y, PPARγ and adipokine levels. Insulin and glucose tolerance were studied in 12- to 14-week-old mice exposed to MPA + DMBA that were group-housed and fed control diet (G-C), group-housed and fed obesity-inducing diet (G-OID), socially isolated and fed control diet (I-C) and socially isolated and fed OID (I-OID) (n = 4–10 mice per group). Blood glucose levels were determined at baseline (0 min, before injection) and 30, 60, 90 and 120 min after injection. (A) Insulin tolerance: at 60 min, glucose levels were significantly higher in I-OID mice than the G-C mice: P = 0.015 (difference marked with *). (B) Area under the curve (AUTC) in insulin tolerance test was significantly increased in socially isolated OID-fed mice: P = 0.021. (C) Glucose tolerance: At baseline, glucose levels were significantly elevated by social isolation but only in control diet-fed mice: P for interaction = 0.013. At 60 min, OID elevated glucose levels: P = 0.015. In addition, there was a significant interaction between OID and social interaction at 60 min: P = 0.021 (for interaction), 90 min: P = 0.016 (for interaction) and 120 min: P = 0.038 (for interaction), indicating that OID elevated glucose levels in group-housed mice and social isolation in control diet-fed mice (differences marked with *). (D) There was a significant interaction between OID and social isolation in affecting AUTC in glucose tolerance test (P = 0.033). At the end of tumor-monitoring period, serum and mammary tissues were obtained and EIA and qRT-PCR were performed to determine the circulating levels of neuropeptide Y (NPY), leptin and adiponectin and mRNA expression of Pparγ in the mammary glands (n = 4–7 mice per group). (E) NPY levels were significantly elevated in I-OID group; interaction: P = 0.013. (F) Leptin levels were significantly elevated in OID-fed mice: P < 0.001, and (G) adiponectin levels were significantly reduced in OID-fed mice: P = 0.011 and socially isolated mice: P = 0.042, but post hoc analysis indicated that the difference was significant only between G-OID and G-C groups. (H) Pparγ mRNA expression was significantly reduced by OID: P = 0.010 and social isolation: P = 0.036, but post hoc analysis indicated that the difference was significant only between I-OID and G-C groups. Bars marked with different letters are significantly different from each other. Means and standard error of means (s.e.m.) are shown.

Glucose tolerance in C57BL/6 mice

At baseline, isolated mice fed the control diet had higher baseline glucose levels than the other three groups (P for interaction: 0.013). At 60 and 90 min, group-housed OID-fed mice had the highest glucose levels, but the levels also were elevated in socially isolated mice that consumed the control diet (Fig. 4C). At 60 min (P for interaction = 0.021), 90 min (P for interaction = 0.016) and 120 min (P for interaction = 0.038), a significant interaction between OID and social isolation was found: OID-fed group-housed mice and control diet-fed socially isolated mice exhibited glucose intolerance, but the mice housed in social isolation and fed OID did not (Fig. 4C). AUC in this test was also significantly higher in the two groups but not in socially isolated OID-fed mice (P for interaction = 0.033) (Fig. 4D).

NPY and adipokine levels in serum in C57BL/6 mice at the end of tumor monitoring period

In carcinogen-exposed mice that were housed in social isolation for 5 months, NPY was significantly increased by the combination of social isolation and OID but not by OID or social isolation alone (P for interaction: 0.013) (Fig. 4E). In contrast, leptin levels were significantly increased (P < 0.001) and adiponectin levels were reduced by OID (P = 0.011). Although statistical analysis indicated that social isolation also reduced adiponectin levels (P = 0.042), post hoc analysis failed to identify significant differences between the control or OID-fed group-housed mice and isolated mice (Fig. 4F and G). These data show that social isolation and OID had different effects on circulating NPY and adipokine levels.

Expression of NPY- and adiponectin-linked genes in the mammary gland in C57BL/6 mice at the end of tumor monitoring period

To determine if some signaling targets of NPY and adiponectin were affected by OID or social isolation, we measured the mRNA expression of the NPY receptor Y1R, Ppar-γ, Il1b, Il6 and TNFα in the mammary gland (Supplementary Fig. 2). Only Ppar-γ expression was significantly altered: it was reduced by OID (P = 0.010) and social isolation (P = 0.036), but in post hoc analysis, only a combination of social isolation and OID was different from the control group (Fig. 4H).

p53 in C57BL/6 mice at the end of tumor monitoring period

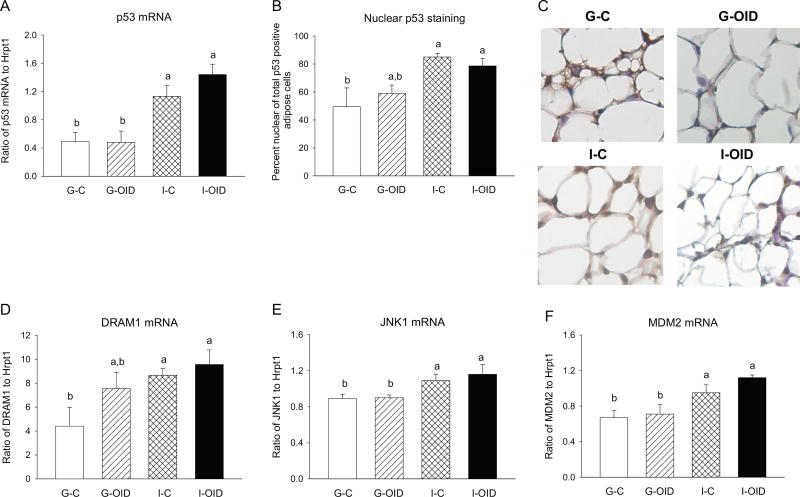

Social isolation (P < 0.001), but not OID, upregulated p53 mRNA expression in the mammary gland (Fig. 5A). Immunohistochemistry showed that p53 staining was strong in the mammary epithelium and located mostly in the cytoplasm in all groups; nuclear staining was also present (Fig. 5B and C). Prior studies indicate that cytosolic p53 expression inhibits, and nuclear expression increases, autophagy (Scherz-Shouval et al. 2010). Due to extensive epithelial staining in all samples, we quantified total and nuclear p53 staining in the mammary adipocytes because p53 staining was lower in the adipocytes than the epithelium. Social isolation (P = 0.016), but not OID, increased the percentage of adipocytes with nuclear staining vs staining in the cytoplasm (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5.

Effect of OID and social isolation on p53, determined in the mammary glands of mice group-housed and fed control diet (G-C), group-housed and fed obesity-inducing high-fat diet (G-OID), socially isolated and fed control diet (I-C), and socially isolated and fed OID (I-OID) (n = 4–7 mice per group for RNA and n = 6–11 mice per group for immunohistochemistry, IHC). All mice were exposed to MPA + DMBA, and glands were collected at the end of tumor monitoring period. (A) Social isolation upregulated Trp53 mRNA levels; social isolation: P < 0.001. (B and C) Nuclear staining of p53 in mammary adipocytes, determined by IHC, was significantly increased by social isolation: P = 0.016. (D) Social isolation increased mRNA levels of Dram1; social isolation: P = 0.003 and (E) Jnk1 (n = 5–7/group); social isolation: P = 0.003. (F) Social isolation also increased mRNA levels of Mdm2; social isolation: P < 0.001.

We then investigated if p53-regulated autophagy pathways may be affected by social isolation and/or OID. DRAM1 is a direct target of p53 that regulates autophagy by participating in the fusion of autophagosomes and lysosomes (Crighton et al. 2006). JNK can induce autophagy (Lorin et al. 2010) by activating Beclin 1 that in turn activates p53 (Li et al. 2009, Park et al. 2009). Social isolation, but not OID, increased the expression of both the DRAM1 (P = 0.003) (Fig. 5D) and JNK1 (P = 0.003) mRNAs (Fig. 5E).

Mdm2 in C57BL/6 mice at the end of tumor monitoring period

Mdm2 interacts closely with p53 to inhibit p53 transcription or direct its degradation (for review (Manfredi 2010)). These interactions can be disrupted by oncogenic signals, allowing p53 to remain elevated even when Mdm2 is upregulated (Senturk & Manfredi 2012). We found that the expression of Mdm2 was significantly higher in the mammary glands of the socially isolated mice than that in group-housed mice (P < 0.001) (Fig. 5F). As these mice also exhibited increased p53 expression, social isolation disrupted the feedback loop between p53 and Mdm2.

Experiment 2

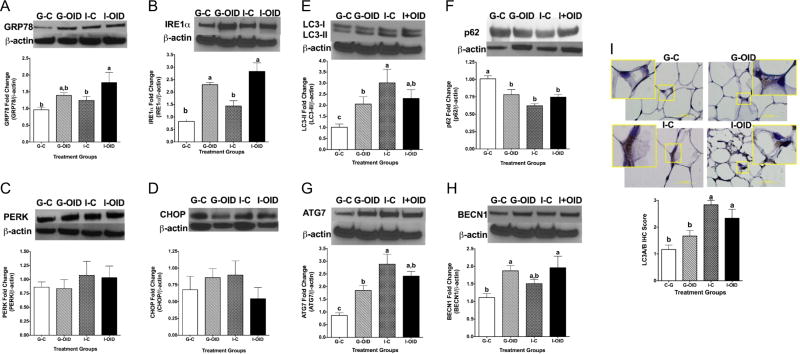

Unfolded protein response in C57BL/6 mice after 4 weeks in social isolation

Next, we determined if UPR pathways are affected by OID and/or social isolation. Protein levels of GRP78, PERK, IRE1 and DNA damage-inducible transcript 3 or C/EBP homologous protein (CHOP) were measured in the mammary glands of mice that were housed in social isolation or fed OID for 4 weeks and that were not treated with the carcinogen. Western blot analysis indicated that a combination of social isolation and OID increased GRP78 levels (P = 0.016) (Fig. 6A), whereas IRE1 was increased both by OID (P < 0.001) and social isolation (P = 0.012) (Fig. 6B). No corresponding changes in PERK (Fig. 6C) or CHOP expression were seen (Fig. 6D). These data suggest a specific regulation of UPR signaling by social isolation and OID that in combination activate the master UPR regulator GRP78 without increasing the primarily proapoptotic stimulus associated with PERK and CHOP activation.

Figure 6.

Effect of OID and social isolation on unfolded protein response (UPR), determined by immunoblotting UPR markers (A) GRP78; increased by OID: P = 0.016, but post hoc analysis indicated that only isolated mice fed OID had significantly higher expression of GRP78 than controls, (B) IRE1; increased by OID: P < 0.001 and social isolation: P = 0.012. (C) PERK; no significant changes, (D) CHOP; no significant changes. Effect of OID and social isolation on autophagy, determined by immunoblotting autophagy markers (H) Beclin1; increased by OID: P = 0.008, (G) Atg7; increased by social isolation: P < 0.0001. Although OID also increased Atg7 expression in group-housed mice, socially isolated mice fed control diet had higher expression than G-OID or I-OID: P for interaction = 0.002, (E) LC3II; increased by social isolation: P = 0.002. Although OID also increased LC3II expression in group-housed mice, socially isolated mice fed control diet had higher expression than G-OID or I-OID: P for interaction = 0.009, and (F) p62; downregulated by social isolation: P < 0.001. Although OID also reduced p62 expression in group-housed mice, socially isolated mice fed control diet had higher expression than G-OID or I-OID: P for interaction = 0.003. (I) LC3A/B puncta staining of mammary glands; increased by social isolation: P < 0.001. Bars marked with different letters are significantly different from each other. Means and standard error of means (s.e.m.) of 4–11 mice per group are shown; these mice were not exposed to DMBA.

Autophagy in C57BL/6 mice after 4 weeks in social isolation

Previous studies have found increased autophagy in adipose tissue of obese individuals (Jansen et al. 2012), and this is proposed to be a response to limit obesity-induced inflammatory changes. To explore a possible link between social isolation and autophagy, the expression levels of proteins associated with autophagy (Beclin 1, Atg7, LC3II and p62) were measured in the mammary glands of the mice used to study UPR. Beclin 1 (Atg6) levels were significantly elevated by OID (P = 0.008) (Fig. 6E). Social isolation strongly increased Atg7 (P = 0.002) (Fig. 6F) and LC3II levels (P = 0.002) (Fig. 6G) and reduced p62 expression (P < 0.001) (Fig. 6H). As these changes were most profound in the control diet-fed and socially isolated mice, but OID did not cause significant changes, P-value for interaction was significant for these three autophagy genes (Atg7: P = 0.002; LC3II: P = 0.009; p62: P = 0.003). Finally, the expression of the autophagy marker LC3A/B was significantly increased in the mammary glands of socially isolated mice (P < 0.001) (Fig. 6I). There was no indication of a combined effect on autophagy by OID and social isolation; in fact, social isolation alone generated the most significant changes in most parameters of autophagy. As none of the UPR genes were significantly altered in the mice that received control diet and were housed in social isolation, social isolation may induce autophagy through other mechanisms than UPR.

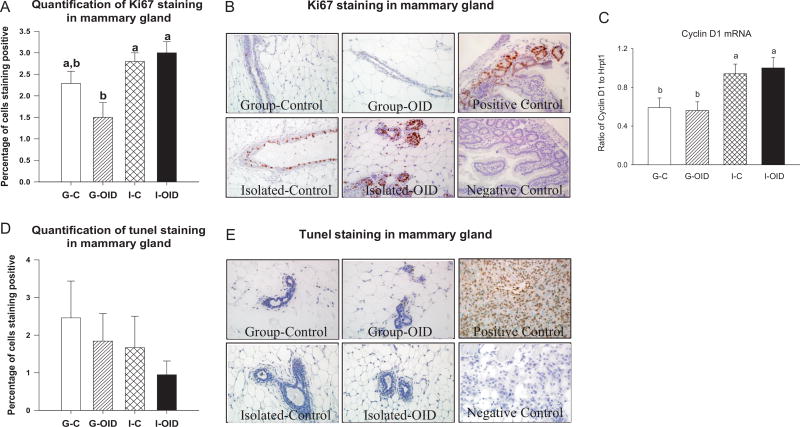

Assessment of proliferation and apoptosis in the mammary glands in C57BL/6 mice at the end of tumor monitoring period

Autophagy can lead not only to cell survival but also to cell cycle arrest and induction of apoptosis. Thus, we measured changes in Ki67 protein levels and the expression of cyclin D1 and p21 mRNAs to determine the changes in cell proliferation. Apoptosis was evaluated using the TUNEL assay. Social isolation (P = 0.002), but not obesity, significantly increased Ki67 levels (Fig. 7A and B) and cyclin D1 expression (P < 0.001) (Fig. 7C). No change in apoptosis was observed by social isolation or OID (Fig. 7D and E), consistent with the lack of changes in proapoptotic PERK and CHOP expression in the UPR pathway. These findings, together with the autophagy results, suggest that social isolation promotes autophagy-induced survival signaling in the mammary gland, whereas the increased autophagy seen in OID-fed mice that are group-housed induces neither apoptosis nor cell proliferation.

Figure 7.

Effect of OID and social isolation on cell proliferation and apoptosis, determined in the mammary glands of mice group-housed and fed control diet (G-C), group-housed and fed obesity-inducing diet (G-OID), socially isolated and fed control diet (I-C), and socially isolated and fed OID (I-OID) (n = 4–10 mice per group). All mice were exposed to MPA + DMBA, and glands were collected at the end of tumor monitoring period. Indicators of cell proliferation were elevated in socially isolated mice: (A and B) assessed by Ki67 staining; social isolation: P = 0.002 and (C) Ccnd1 mRNA; social isolation: P < 0.001. (D and E) Apoptosis was not altered in any of the groups (assessed by TUNEL assay). Bars marked with different letters are significantly different from each other. Means and standard error of means (s.e.m.) are shown.

Experiment 3

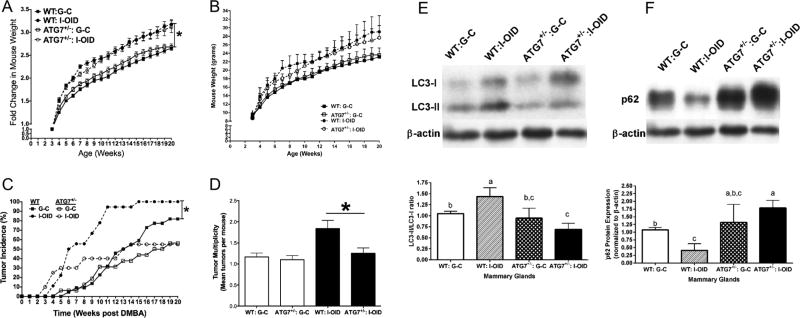

Mammary tumorigenesis in socially isolated Atg7+/− mice

To determine whether an increase in autophagy mediates the effects of social isolation on mammary tumorigenesis, heterozygous Atg7+/− mice and their wild-type control mice were divided into two groups: (1) group-housed and fed control diet or (2) socially isolated and fed OID. Mammary tumors were induced using MPA and DMBA. Body weights were similar in control diet-fed wild-type and Atg7+/− mice and also increased similarly in the two genotypes under OID and social isolation (Fig. 8A and B). The increase was significant when body weight was assessed as a percent change from the baseline – that is, before mice were socially isolated and fed OID (P = 0.023). However, due to large interindividual variations in body weights, the raw data did not reach statistical significance. Social isolation, combined with OID, significantly increased mammary tumorigenesis (incidence: P = 0.037; and multiplicity: P = 0.0014) in wild-type mice, but did not do so in the autophagy-deficient Atg7+/− mice (Fig. 8C and D). There were no baseline differences in mammary tumorigenesis between wild-type and Atg7+/− mice that were group-housed and fed control diet.

Figure 8.

Effect of OID and social isolation on body weight, autophagy and mammary tumorigenesis in Atg7+/− mice. Atg7+/− and their wild-type (WT) littermates were group-housed and fed control diet (G-C) or socially isolated and fed obesity-inducing diet (I-OID). Body weight gain from weaning until week 20 (n = 15–21 mice/group), (A) shown as a fold change from the body weight at weaning and (B) body weight in grams. Fold change in body weights was significantly higher in socially isolated, OID-fed mice than in group-housed mice fed the control diet: P = 0.023. (C) MPA + DMBA-induced mammary tumor incidence was significantly higher in WT mice kept in I-OID than in group-housed G-C mice (P = 0.037), but not in I-OID Atg7+/− mice, compared with G-C Atg7+/− mice (P = 0.267) (n = 16–20 mice/group). (D) Among socially isolated mice fed OID, mammary tumor multiplicity (number of tumors per mice) was significantly higher (P = 0.0014) in WT group than in Atg7+/− mice. Significant differences are marked with *. (E) LC3II or (F) p62 levels were determined in mammary glands at the end of mammary tumor monitoring period, and they were not different in group-housed WT and Atg7+/− mice. Social isolation increased LC3II levels in WT mice and reduced them in Atg7+/− mice, compared with control WT mice (P for interaction = 0.002). Social isolation reduced p62 levels in WT mice but increased them in Atg7+/− mice (P for interaction = 0.006). Bars marked with different letters are significantly different from each other. Means and standard error of means (s.e.m.) are shown.

LC3II and p62 levels in socially isolated Atg7+/− mice

Atg7 is not downregulated in Atg7+/− mice that express one normal and one mutated Atg7 gene (Komatsu et al. 2005). However, under stressed conditions, such as excess body weight, Atg7+/− mice exhibit reduced autophagy (Lim et al. 2014). Our results are in line with these previous findings: no significant differences were seen in LC3II or p62 levels between group-housed and control diet-fed wild-type and Atg7+/− mice (Fig. 8E and F). Social isolation in OID-fed wild-type mice significantly increased LC3II levels (P = 0.001) and reduced p62 levels (P = 0.017), whereas the opposite took place in Atg7+/− mice (P for interaction = 0.002 for LC3II and P for interaction = 0.006 for p62). Taken together, our data indicate that an increase in autophagy mediates at least partly the effects of social isolation on increased mammary tumorigenesis.

Discussion

We determined if social isolation increases breast cancer risk by mimicking the biological changes induced by increased body weight in a mouse model. Similar to previous reports (Lauder et al. 2006, Whisman 2010), social isolation promoted body weight gain, particularly among the mice that also were fed OID. However, after 3 months of social isolation when mammary tumorigenesis was assessed, body weights of mice kept in social isolation and fed with the control diet no longer were higher than those of the control mice. Social isolation was as effective in increasing mammary tumorigenesis as was consumption of OID. Further, socially isolated mice fed OID had significantly higher mammary tumorigenesis than either group-housed OID-fed mice or socially isolated mice fed the control diet. Our findings thus suggest that social isolation and intake of OID is a powerful combination in increasing body weight and breast cancer risk.

To determine if body weight gain induced by social isolation was a key determinant in mediating its effects on increased cancer risk, we compared some breast cancer risk-related effects of consumption of OID to those caused by social isolation, such as insulin resistance (Vona-Davis et al. 2007). As expected, OID induced insulin resistance; that is, it impaired both insulin and glucose tolerance. However, social isolation alone did not alter insulin tolerance, but it impaired glucose tolerance. Mice that were fed OID and were socially isolated exhibited only impaired insulin tolerance but no changes in glucose tolerance. Thus, the effects of social isolation on insulin resistance are both similar and different than those caused by OID.

We also assessed the changes in visceral fat depots, circulating adipokine levels and mammary tissue cytokine expression between OID fed and socially isolated mice, as these end points are linked to insulin resistance (Zimmet et al. 1998, Yamauchi et al. 2001, Iannucci et al. 2007). Consumption of OID for 4 weeks, but not social isolation, increased the weight of epididymal visceral fat depot, consistent with an earlier study that did not find an increase in visceral fat depots by a short-term social isolation (Krolow et al. 2013). However, a long-term social isolation is reported to increase visceral fat (Sakakibara et al. 2012). Serum leptin levels were increased and adiponectin levels were reduced by long-term consumption of OID, consistent with the vast literature regarding the effects of obesity on these adipokines (Staiger et al. 2003). Social isolation had no effect on either adipokine. Previous studies have reported no changes in leptin levels by social isolation in mice and rats (Krolow et al. 2013, Volden et al. 2013) and a reduction in adiponectin levels in mice (Sakakibara et al. 2012). We conclude that changes in adipokines and higher amount of visceral fat likely explain insulin resistance in OID-fed mice, but not in socially isolated mice. As high leptin levels (Surmacz 2007, Grossmann et al. 2008) and low adiponectin levels (Tian et al. 2007) are associated with increased breast cancer risk, they may have contributed to increased mammary tumorigenesis in the OID-fed mice.

Neither OID nor social isolation affected the expression of Il1b, Il6 or Tnfa in the mammary gland. Only in socially isolated mice fed OID, a reduction in mammary nuclear peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (Pparγ) expression and an increase in NPY levels were seen; that is, these changes were not present in group-housed OID-fed mice or socially isolated mice fed a control diet. PPARγ is a master regulator of adipocyte differentiation and function. Through interactions with NFκB and subsequent anti-inflammatory response (Tontonoz & Spiegelman 2008), as well as interactions with adiponectin (Tontonoz & Spiegelman 2008), insulin receptor (Costa et al. 2008) and regulatory T cells (Cipolletta 2014), PPARγ improves insulin sensitivity (Kintscher & Law 2005). Previous studies have reported an increase in PPARγ expression by obesity in adipose tissue in an animal model (Vidal-Puig et al. 1996) and humans (Vidal-Puig et al. 1997), perhaps reflecting an attempt of the increasing adiposity to maintain insulin sensitivity. No such increase was seen in the mammary tissue in our study. The role of PPARγ expression in affecting breast cancer risk remains conflicting, but most studies suggest that low levels are associated with increased breast cancer risk (Grommes et al. 2004, Apostoli et al. 2014). Our finding that Pparg expression was reduced by social isolation in OID-fed mice is consistent with this interpretation and may be linked to their increased mammary tumorigenesis.

Being produced by neurons in the hypothalamus, NPY is not only the most abundant peptide in the brain but also released in peripheral sympathetic nerves during stress (Zukowska-Grojec 1995). One of the main functions of NPY in the brain is appetite control. NPY is reported to induce weight gain and insulin resistance (Kuo et al. 2007, Nonogaki et al. 2007). Leptin inhibits NPY in the hypothalamus (Stephens et al. 1995), and adiponectin receptors and NPY colocalize in the arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus (Guillod-Maximin et al. 2009), insinuating that leptin, adiponectin and NPY may interact. Moreover, NPY plays an integral role in visceral adipose inflammation mediation (Chandrasekharan et al. 2013) and immune responses (Nair et al. 1993). The link between NPY and breast cancer has not been investigated beyond few in vitro studies (Amlal et al. 2006, Sheriff et al. 2010, Medeiros et al. 2012, Medeiros & Jackson 2013). In an earlier study, social isolation led to increased hypothalamic NPY levels (Krolow et al. 2013), in agreement with our study showing increased circulating NPY levels in socially isolated, OID-fed mice. Taken together, reduced Pparγ expression and increased NPY levels could explain insulin resistance in socially isolated mice that also were fed OID.

We next determined if UPR pathways and/or autophagy were affected by OID and/or social isolation. UPR (Hosogai et al. 2007, Gregor et al. 2009) and autophagy (Lavallard et al. 2012, Grijalva et al. 2016) are both known to be activated in adipose tissue by obesity. Consistent with these findings, OID-fed mice in our study exhibited higher levels of UPR, although the increase was significant only in the IRE1α arm. Further, all measures of survival autophagy were altered by OID: Beclin-1, Atg7 and LC3II protein levels were elevated, and p62 protein level was reduced. We found that social isolation, but only when combined with OID, also elevated IRE1α levels and increased the expression of master UPR regulator GRP78. There were no significant changes in the pro-death UPR components PERK and CHOP in the mammary glands of OID-fed or socially isolated mice, or their combination, indicating that activation of the UPR signaling axis in these mice favors cancer cell survival.

In contrast to UPR that was affected mainly by OID, social isolation was more effective in increasing autophagy than OID. The LC3A/B data univocally showed elevated autophagy in the mammary glands of socially isolated mice, but not in group-housed OID-fed mice. No additive effect between OID and social isolation was observed for autophagy.

Autophagy can be modified by several other pathways besides UPR, including nuclear expression of p53 (Levine & Abrams 2008). We found an increased expression of p53 mRNA in the mammary glands of socially isolated mice, consistent with earlier reports that social isolation upregulates p53 (Filipovic et al. 2011, Senturk & Manfredi 2012). Further, nuclear p53 was increased in these mice. The increase in p53 expression was not caused by OID or increased body weight because group-housed OID-fed mice did not exhibit changes in p53 expression. Others have shown that social isolation increases oxidative stress (Zhuravliova et al. 2009, Zlatkovic et al. 2014) and causes metabolic changes (Zhuravliova et al. 2009, Whisman 2010, Volden et al. 2013); these changes might have led to an upregulation of p53. Importantly, heterozygous p53-knockout mice do not exhibit increased mammary tumorigenesis when housed in social isolation (Hasen et al. 2010), indicating that upregulation of p53 mediates the effects of social isolation on mammary tumorigenesis.

When p53 is expressed in the nucleus, stressors are reported to initiate autophagy to promote cell survival via DRAM1 (Scherz-Shouval et al. 2010), which is a direct target of p53 (Crighton et al. 2006). Another p53-associated gene that induces autophagy is JNK (Lorin et al. 2010). JNK activates Beclin 1 that in turn activates p53 (Li et al. 2009, Park et al. 2009). We found that social isolation, but not obesity, led to increased Dram1 and Jnk1 mRNA expression. In a previous study, HK2 was found to be increased in the mammary glands of socially isolated mice (Volden et al. 2013). Importantly, HK2 induces autophagy (Roberts & Miyamoto 2015). Thus, although social isolation did not alter UPR signaling to affect autophagy, the increase in p53, Dram1 and Jnk1 observed here and the increase in HK2 reported earlier (Volden et al. 2013) might explain elevated autophagy in the mammary glands of socially isolated mice.

Social isolation was linked to increased expression of Mdm2 in the mammary gland. Mdm2 is inhibited by p53 (Manfredi 2010), but activated by Ras that is also upregulated by social isolation (Zhuravliova et al. 2009). The increase in Mdm2 mRNA expression in our study could therefore reflect Ras activation and that in turn may explain the disruption of negative feedback between p53 and Mdm2 by social isolation. Mdm2 has also been linked to autophagy (Borthakur et al. 2015). Mdm2 may have contributed to promoting tumor growth (Senturk & Manfredi 2012) in socially isolated mice; the p53-independent mechanisms of Mdm2 include promotion of cell proliferation, inhibition of apoptosis and induction of an epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (Manfredi 2010).

In our last experiment, the causality between increased autophagy and mammary tumorigenesis in socially isolated mice was investigated by comparing mammary cancer risk in wild-type mice and mice with one mutated Atg7 allele. As Atg7+/− mice did not exhibit a significant increase in mammary tumorigenesis when housed in social isolation and fed OID, but wild-type mice did, Atg7-induced autophagy at least partially mediates the effects of social isolation on breast cancer risk. Importantly, social isolation and OID increased autophagy in the mammary glands of wild-type mice, but reduced autophagy in the Atg7+/− mice.

Conclusions

Our data suggest that consumption of OID and a consequent increase in body weight potentiate the effects of social isolation on mammary carcinogenesis, but do not explain why social isolation increases breast cancer risk. Instead, the increase may result from autophagy, perhaps induced by upregulation of p53. As social isolation mimics the effects of PTSD in mice (Pinna 2010) and almost one-quarter of newly diagnosed breast cancer patients suffer from symptoms similar to PTSD (Vin-Raviv et al. 2013), future studies should determine if these patients may experience a worse outcome than patients who are less stressed by their diagnosis due to upregulation of survival autophagy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center (LCCC) Animal Model Shared Resource for help in performing animal studies, the LCCC Histopathology Shared Resource for tissue processing and ERα and Ki67 IHC, and Dr Susana Galli for assessing histopathology of the tumors. The authors also want to thank Dr Jason Tilan for help with the NPY assays.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute (P30-CA51008, RO1-CA164384, U54-CA149147).

Footnotes

This is linked to the online version of the paper at http://dx.doi.org/10.1530/ERC-16-0359.

Declaration of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest for any of the authors that could be perceived as prejudicing the impartiality of the research reported.

Author contribution statement

A Sumis participated in design of the study, performance of most of the animal studies and molecular biology assays, data analysis, preparation of the figures and writing the manuscript. K L Cook participated in design and performance of UPR and autophagy assays, performance of studies involving Atg7+/− mice, data analysis, preparation of the figures and writing the manuscript. F O Andrade participated in design of the study, performance of RNA and protein expression analysis for p53 and its downstream targets and data analysis; R Hu conducted UPR and autophagy assays. E Kidney performed animal studies and molecular biology assays. X Zhang performed some RNA and protein expression analyses, and insulin and glucose sensitivity assays. D Kim performed most of the animal studies and molecular biology assays, data analysis and preparation of the figures. E Carney and N Nguyen performed insulin and glucose sensitivity testing. W Yu performed animal studies for Experiment 2 and participated in insulin and glucose sensitivity testing. K B Bouker determined the p53 expression using immunohistochemistry. I Cruz provided oversight for all animal studies and performed them. R Clarke advised in designing UPR and autophagy assays, and participated in writing the manuscript. L Hilakivi-Clarke helped in the overall study design, study oversight, data analysis, preparation of the figures and manuscript writing.

References

- Achat H, Kawachi I, Byrne C, Hankinson S, Colditz G. A prospective study of job strain and risk of breast cancer. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2000;29:622–628. doi: 10.1093/ije/29.4.622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allred DC, Harvey JM, Berardo M, Clark GM. Prognostic and predictive factors in breast cancer by immunohistochemical analysis. Modern Pathology. 1998;11:155–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amlal H, Faroqui S, Balasubramaniam A, Sheriff S. Estrogen up-regulates neuropeptide Y Y1 receptor expression in a human breast cancer cell line. Cancer Research. 2006;66:3706–3714. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apostoli AJ, Skelhorne-Gross GE, Rubino RE, Peterson NT, Di Lena MA, Schneider MM, SenGupta SK, Nicol CJ. Loss of PPARgamma expression in mammary secretory epithelial cells creates a pro-breast tumorigenic environment. International Journal of Cancer. 2014;134:1055–1066. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkman LF, Melchior M, Chastang JF, Niedhammer I, Leclerc A, Goldberg M. Social integration and mortality: a prospective study of French employees of Electricity of France-Gas of France: the GAZEL Cohort. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2004;159:167–174. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borthakur G, Duvvuri S, Ruvolo V, Tripathi DN, Piya S, Burks J, Jacamo R, Kojima K, Ruvolo P, Fueyo-Margareto J, et al. MDM2 inhibitor, nutlin 3a, induces p53 dependent autophagy in acute leukemia by AMP kinase activation. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0139254. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0139254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacioppo JT, Hawkley LC. Social isolation and health, with an emphasis on underlying mechanisms. Perspectives in Biology and Medicine. 2003;46:S39–S52. doi: 10.1353/pbm.2003.0049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cha YJ, Kim YH, Cho NH, Koo JS. Expression of autophagy related proteins in invasive lobular carcinoma: comparison to invasive ductal carcinoma. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Pathology. 2014;7:3389–3398. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakrabarti A, Chen AW, Varner JD. A review of the mammalian unfolded protein response. Biotechnology and Bioengineering. 2011;108:2777–2793. doi: 10.1002/bit.23282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandrasekharan B, Nezami BG, Srinivasan S. Emerging neuropeptide targets in inflammation: NPY and VIP. American Journal of Physiology: Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology. 2013;304:G949–G957. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00493.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen N, Karantza-Wadsworth V. Role and regulation of autophagy in cancer. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2009;1793:1516–1523. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2008.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cipolletta D. Adipose tissue-resident regulatory T cells: phenotypic specialization, functions and therapeutic potential. Immunology. 2014;142:517–525. doi: 10.1111/imm.12262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke R, Cook KL, Hu R, Facey CO, Tavassoly I, Schwartz JL, Baumann WT, Tyson JJ, Xuan J, Wang Y, et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress, the unfolded protein response, autophagy, and the integrated regulation of breast cancer cell fate. Cancer Research. 2012;72:1321–1331. doi: 10.1158/1538-7445.AM2012-1321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook KL, Shajahan AN, Clarke R. Autophagy and endocrine resistance in breast cancer. Expert Review of Anticancer Therapy. 2011;11:1283–1294. doi: 10.1586/era.11.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa V, Foti D, Paonessa F, Chiefari E, Palaia L, Brunetti G, Gulletta E, Fusco A, Brunetti A. The insulin receptor: a new anticancer target for peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma (PPARgamma) and thiazolidinedione-PPARgamma agonists. Endocrine-Related Cancer. 2008;15:325–335. doi: 10.1677/ERC-07-0226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crighton D, Wilkinson S, O’Prey J, Syed N, Smith P, Harrison PR, Gasco M, Garrone O, Crook T, Ryan KM. DRAM, a p53-induced modulator of autophagy, is critical for apoptosis. Cell. 2006;126:121–134. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.05.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrow JM, Yang JC, Evans CP. Autophagy as a modulator and target in prostate cancer. Nature Reviews Urology. 2014;11:508–516. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2014.196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filipovic D, Zlatkovic J, Inta D, Bjelobaba I, Stojiljkovic M, Gass P. Chronic isolation stress predisposes the frontal cortex but not the hippocampus to the potentially detrimental release of cytochrome c from mitochondria and the activation of caspase-3. Journal of Neuroscience Research. 2011;89:1461–1470. doi: 10.1002/jnr.22687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulda S, Gorman AM, Hori O, Samali A. Cellular stress responses: cell survival and cell death. International Journal of Cell Biology. 2010;2010:214074. doi: 10.1155/2010/214074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregor MF, Yang L, Fabbrini E, Mohammed BS, Eagon JC, Hotamisligil GS, Klein S. Endoplasmic reticulum stress is reduced in tissues of obese subjects after weight loss. Diabetes. 2009;58:693–700. doi: 10.2337/db08-1220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grijalva A, Xu X, Ferrante AW., Jr Autophagy is dispensable for macrophage mediated lipid homeostasis in adipose tissue. Diabetes. 2016;65:967–980. doi: 10.2337/db15-1219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimm MS, Emerman JT, Weinberg J. Effects of social housing condition and behavior on growth of the Shionogi mouse mammary carcinoma. Physiology and Behavior. 1996;59:633–642. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(95)02126-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grommes C, Landreth GE, Heneka MT. Antineoplastic effects of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma agonists. Lancet Oncology. 2004;5:419–429. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(04)01509-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossmann ME, Ray A, Dogan S, Mizuno NK, Cleary MP. Balance of adiponectin and leptin modulates breast cancer cell growth. Cell Research. 2008;18:1154–1156. doi: 10.1038/cr.2008.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillod-Maximin E, Roy AF, Vacher CM, Aubourg A, Bailleux V, Lorsignol A, Pénicaud L, Parquet M, Taouis M. Adiponectin receptors are expressed in hypothalamus and colocalized with proopiomelanocortin and neuropeptide Y in rodent arcuate neurons. Journal of Endocrinology. 2009;200:93–105. doi: 10.1677/JOE-08-0348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasen NS, O’Leary KA, Auger AP, Schuler LA. Social isolation reduces mammary development, tumor incidence, and expression of epigenetic regulators in wild-type and p53-heterozygotic mice. Cancer Prevention Research. 2010;3:620–629. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-09-0225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermes GL, Delgado B, Tretiakova M, Cavigelli SA, Krausz T, Conzen SD, McClintock MK. Social isolation dysregulates endocrine and behavioral stress while increasing malignant burden of spontaneous mammary tumors. PNAS. 2009;106:22393–22398. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910753106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilakivi-Clarke L, Dickson RB. Stress influence on development of hepatocellular tumors in transgenic mice overexpressing TGF alpha. Acta Oncologica. 1995;34:907–912. doi: 10.3109/02841869509127203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilakivi-Clarke L, Rowland J, Clarke R, Lippman ME. Psychosocial factors in the development and progression of breast cancer. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. 1994;29:141–160. doi: 10.1007/BF00665676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosogai N, Fukuhara A, Oshima K, Miyata Y, Tanaka S, Segawa K, Furukawa S, Tochino Y, Komuro R, Matsuda M, et al. Adipose tissue hypoxia in obesity and its impact on adipocytokine dysregulation. Diabetes. 2007;56:901–911. doi: 10.2337/db06-0911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iannucci CV, Capoccia D, Calabria M, Leonetti F. Metabolic syndrome and adipose tissue: new clinical aspects and therapeutic targets. Current Pharmaceutical Design. 2007;13:2148–2168. doi: 10.2174/138161207781039571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansen HJ, van Essen P, Koenen T, Joosten LA, Netea MG, Tack CJ, Stienstra R. Autophagy activity is up-regulated in adipose tissue of obese individuals and modulates proinflammatory cytokine expression. Endocrinology. 2012;153:5866–5874. doi: 10.1210/en.2012-1625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kintscher U, Law RE. PPARgamma-mediated insulin sensitization: the importance of fat versus muscle. American Journal of Physiology: Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2005;288:E287–E291. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00440.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komatsu M, Waguri S, Ueno T, Iwata J, Murata S, Tanida I, Ezaki J, Mizushima N, Ohsumi Y, Uchiyama Y, et al. Impairment of starvation-induced and constitutive autophagy in Atg7-deficient mice. Journal of Cell Biology. 2005;169:425–434. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200412022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke CH, Kubzansky LD, Schernhammer ES, Holmes MD, Kawachi I. Social networks, social support, and survival after breast cancer diagnosis. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2006;24:1105–1111. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.2846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krolow R, Noschang C, Arcego DM, Huffell AP, Marcolin ML, Benitz AN, Lampert C, Fitarelli RD, Dalmaz C. Sex-specific effects of isolation stress and consumption of palatable diet during the prepubertal period on metabolic parameters. Metabolism. 2013;62:1268–1278. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2013.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo LE, Kitlinska JB, Tilan JU, Li L, Baker SB, Johnson MD, Lee EW, Burnett MS, Fricke ST, Kvetnansky R, et al. Neuropeptide Y acts directly in the periphery on fat tissue and mediates stress-induced obesity and metabolic syndrome. Nature Medicine. 2007;13:803–811. doi: 10.1038/nm1611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai K, Killingsworth MC, Lee CS. The significance of autophagy in colorectal cancer pathogenesis and implications for therapy. Journal of Clinical Pathology. 2014;67:854–858. doi: 10.1136/jclinpath-2014-202529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauder W, Mummery K, Jones M, Caperchione C. A comparison of health behaviours in lonely and non-lonely populations. Psychology Health and Medicine. 2006;11:233–245. doi: 10.1080/13548500500266607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavallard VJ, Meijer AJ, Codogno P, Gual P. Autophagy, signaling and obesity. Pharmacological Research. 2012;66:513–525. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2012.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine B, Abrams J. p53: The Janus of autophagy? Nature Cell Biology. 2008;10:637–639. doi: 10.1038/ncb0608-637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine B, Klionsky DJ. Development by self-digestion: molecular mechanisms and biological functions of autophagy. Developmental Cell. 2004;6:463–477. doi: 10.1016/S1534-5807(04)00099-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li DD, Wang LL, Deng R, Tang J, Shen Y, Guo JF, Wang Y, Xia LP, Feng GK, Liu QQ, et al. The pivotal role of c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase-mediated Beclin 1 expression during anticancer agents-induced autophagy in cancer cells. Oncogene. 2009;28:886–898. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lillberg K, Verkasalo PK, Kaprio J, Teppo L, Helenius H, Koskenvuo M. Stressful life events and risk of breast cancer in 10,808 women: a cohort study. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2003;157:415–423. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwg002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim YM, Lim H, Hur KY, Quan W, Lee HY, Cheon H, Ryu D, Koo SH, Kim HL, Kim J, et al. Systemic autophagy insufficiency compromises adaptation to metabolic stress and facilitates progression from obesity to diabetes. Nature Communications. 2014;5:4934. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H, Wang Z. Effects of social isolation stress on immune response and survival time of mouse with liver cancer. World Journal of Gastroenterology. 2005;11:5902–5904. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i37.5902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorin S, Pierron G, Ryan KM, Codogno P, Djavaheri-Mergny M. Evidence for the interplay between JNK and p53-DRAM signalling pathways in the regulation of autophagy. Autophagy. 2010;6:153–154. doi: 10.4161/auto.6.1.10537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manfredi JJ. The Mdm2-p53 relationship evolves: Mdm2 swings both ways as an oncogene and a tumor suppressor. Genes and Development. 2010;24:1580–1589. doi: 10.1101/gad.1941710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchant J. The effects of different social conditions on breast cancer induction in three genetic types of mice by dibenz[a,h]anthracene and a comparison with breast carcinogenesis by 3-methylcholanthrene. British Journal of Cancer. 1967;21:576–585. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1967.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuire WL, Carbone PP, Sears ME, Escher GC. Estrogen receptors in human breast cancer: an overview. In: McGuire WL, Carbone PP, Sears ME, Escher GC, editors. Estrogen Receptors in Human Breast Cancer. New York, NY, USA: Raven Press; 1975. pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- McPherson M, Smith-Lovin L, Brashears ME. Social isolation in America: changes in core discussion networks over two decades. American Sociological Review. 2006;71:353–375. doi: 10.1177/000312240607100301. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Medeiros PJ, Jackson DN. Neuropeptide Y Y5-receptor activation on breast cancer cells acts as a paracrine system that stimulates VEGF expression and secretion to promote angiogenesis. Peptides. 2013;48:106–113. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2013.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medeiros PJ, Al-Khazraji BK, Novielli NM, Postovit LM, Chambers AF, Jackson DN. Neuropeptide Y stimulates proliferation and migration in the 4T1 breast cancer cell line. International Journal of Cancer. 2012;131:276–286. doi: 10.1002/ijc.26350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nair MP, Schwartz SA, Wu K, Kronfol Z. Effect of neuropeptide Y on natural killer activity of normal human lymphocytes. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 1993;7:70–78. doi: 10.1006/brbi.1993.1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson NR. A review of social isolation: an important but underassessed condition in older adults. Journal of Primary Prevention. 2012;33:137–152. doi: 10.1007/s10935-012-0271-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen NR, Zhang ZF, Kristensen TS, Netterstrom B, Schnohr P, Gronbaek M. Self reported stress and risk of breast cancer: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2005;331:548. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38547.638183.06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nonogaki K, Nozue K, Oka Y. Social isolation affects the development of obesity and type 2 diabetes in mice. Endocrinology. 2007;148:4658–4666. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-0296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ojha R, Jha V, Singh SK, Bhattacharyya S. Autophagy inhibition suppresses the tumorigenic potential of cancer stem cell enriched side population in bladder cancer. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2014;1842:2073–2086. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2014.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pantell M, Rehkopf D, Jutte D, Syme SL, Balmes J, Adler N. Social isolation: a predictor of mortality comparable to traditional clinical risk factors. American Journal of Public Health. 2013;103:2056–2062. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parillo VN. Encyclopedia of Social Problems. Thousand Oaks, CA, USA: Sage Publications; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Park KJ, Lee SH, Lee CH, Jang JY, Chung J, Kwon MH, Kim YS. Upregulation of Beclin-1 expression and phosphorylation of Bcl-2 and p53 are involved in the JNK-mediated autophagic cell death. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2009;382:726–729. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.03.095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parmar JH, Cook KL, Shajahan-Haq AN, Clarke PA, Tavassoly I, Clarke R, Tyson JJ, Baumann WT. Modelling the effect of GRP78 on anti-oestrogen sensitivity and resistance in breast cancer. Interface Focus. 2013;3:20130012. doi: 10.1098/rsfs.2013.0012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinna G. In a mouse model relevant for post-traumatic stress disorder, selective brain steroidogenic stimulants (SBSS) improve behavioral deficits by normalizing allopregnanolone biosynthesis. Behavioral Pharmacology. 2010;21:438–450. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e32833d8ba0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PTSD: National Center for PTSD. U.S Department of Veterans Affairs. Washington, DC, USA: 2014. DSM-5 criteria for PTSD. (available at: http://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/PTSD-overview/dsm5_criteria_ptsd.asp#) [Google Scholar]

- Puzio-Kuter AM. The role of p53 in metabolic regulation. Genes Cancer. 2011;2:385–391. doi: 10.1177/1947601911409738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts DJ, Miyamoto S. Hexokinase II integrates energy metabolism and cellular protection: Akting on mitochondria and TORCing to autophagy. Cell Death and Differentiation. 2015;22:364. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2014.208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakakibara H, Suzuki A, Kobayashi A, Motoyama K, Matsui A, Sayama K, Kato A, Ohashi N, Akimoto M, Nakayama T, et al. Social isolation stress induces hepatic hypertrophy in C57BL/6J mice. Journal of Toxicological Sciences. 2012;37:1071–1076. doi: 10.2131/jts.37.1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sansoni J, Marosszeky N, Sansoni E, Fleming G, et al. Final Report: Effective Assessment of Social Isolation. Sydney, Australia: Centre for Health Service Development, University of Wollongong; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Scherz-Shouval R, Weidberg H, Gonen C, Wilder S, Elazar Z, Oren M. p53-dependent regulation of autophagy protein LC3 supports cancer cell survival under prolonged starvation. PNAS. 2010;107:18511–18516. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1006124107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senturk E, Manfredi JJ. Mdm2 and tumorigenesis: evolving theories and unsolved mysteries. Genes Cancer. 2012;3:192–198. doi: 10.1177/1947601912457368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheriff S, Ali M, Yahya A, Haider KH, Balasubramaniam A, Amlal H. Neuropeptide Y Y5 receptor promotes cell growth through extracellular signal-regulated kinase signaling and cyclic AMP inhibition in a human breast cancer cell line. Molecular Cancer Research. 2010;8:604–614. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-09-0301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith TF, Hirdes JP. Predicting social isolation among geriatric psychiatry patients. International Psychogeriatric. 2009;21:50–59. doi: 10.1017/S1041610208007850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staiger H, Tschritter O, Machann J, Thamer C, Fritsche A, Maerker E, Schick F, Häring HU, Stumvoll M. Relationship of serum adiponectin and leptin concentrations with body fat distribution in humans. Obesity Research. 2003;11:368–372. doi: 10.1038/oby.2003.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens TW, Basinski M, Bristow PK, Bue-Valleskey JM, Burgett SG, Craft L, Hale J, Hoffmann J, Hsiung HM, Kriauciunas A, et al. The role of neuropeptide Y in the antiobesity action of the obese gene product. Nature. 1995;377:530–532. doi: 10.1038/377530a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]