Abstract

Novel affinity agents with high specificity are needed to make progress in disease diagnosis and therapy. Over the last several years, peptides have been considered to have fundamental benefits over other affinity agents, such as antibodies, due to their fast blood clearance, low immunogenicity, rapid tissue penetration, and reproducible chemical synthesis. These features make peptides ideal affinity agents for applications in disease diagnostics and therapeutics for a wide variety of afflictions. Virus-derived peptide techniques provide a rapid, robust, and high-throughput way to identify organism-targeting peptides with high affinity and selectivity. Here, we will review viral peptide display techniques, how these techniques have been utilized to select new organism-targeting peptides, and their numerous biomedical applications with an emphasis on targeted imaging, diagnosis, and therapeutic techniques. In the future, these virus-derived peptides may be used as common diagnosis and therapeutics tools in local clinics.

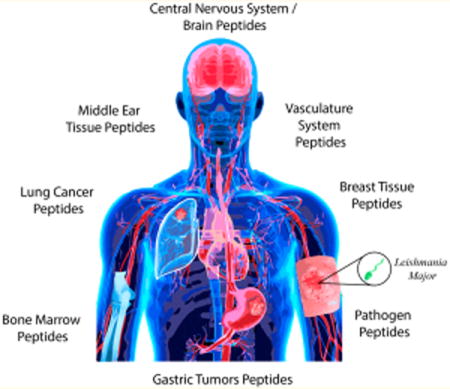

Graphical abstract

1. INTRODUCTION

The proper diagnosis and treatment of illnesses is of vital importance worldwide. For example, cancer is a major cause of human death worldwide.1 In the United States, ∼25% of deaths are caused by cancer. There were a projected 1 660 290 new cancer cases and 580 350 deaths in 2013.2 In China, according to the National Death Survey conducted by the Ministry of Health, cancer is currently the second leading cause of death due to increasing cancer mortality rates in the past few years.3 However, cancer patients are just one of many disease groups that can benefit from swift diagnoses and targeted treatments. Pathogens are another major cause of death. More than 9 million pathogen-related illness diagnoses are due to foodborne pathogens in the United States alone.4 Bacterial pathogens such as Salmonella enterica and Listeria monocytogenes alone account for $3.3 billion and $2.6 billion in medical costs a year in the United States, respectively, and this only scratches the surface. It is estimated that just 14 foodborne pathogens account for $14 billion a year in medical costs for the United States.5 Among other pathogens, fungal infections such as those caused by Candida albicans and Paracoccidioides brasiliensis can also be devastating. It is estimated that the most common fungal diseases in humans affect ∼1.7 billion (or roughly 25%) of the general worldwide population. Despite the current availability of antifungal drugs, invasive fungal infections often have mortality rates exceeding 50%.5 Additionally, viral diseases such as orthopoxviruses (cowpox and monkeypox) infections or avian influenza A, and parasitic illnesses such as malaria or schistosomiasis are also devastating.6–10 Hence, there is an overwhelming need for disease detection and therapeutics. These techniques must be both more effective than currently lacking techniques and cost-effective so that they may be used more widely around the world. This Review will describe cutting edge techniques for disease detection and therapeutics centered around the development of short organism-binding peptide sequences developed through virus-peptide display technology.

Over the past few decades, researchers have devoted a huge effort and investment toward developing affinity agents, including antibodies, proteins, peptides, and nucleic acids.11–19 The use of peptides now has an ever-expanding role with unexpected applications and has even been implicated in virus communication to name just one unique role.20 For example, it has been shown that phages can communicate with each other to make a group decision in regards to their life cycle using a peptide.20 It would be of great importance to discover whether or not more dangerous viruses react in a similar manner. Among these applications, peptides possess several advantages in biomedical applications.21–28 First, peptides can be easily obtained by chemical synthesis with a high yield and low cost. Second, due to their small molecular weight, peptides can enter cells and penetrate tissue easily, can be cleared in the blood rapidly, are quickly metabolized, and have a low immunogenic nature. Another advantage is that peptides do not need to be produced in animals, which makes them more ethical as well as economical than antibody-development techniques.26 These advantages make peptides very appealing for biomedical applications, such as molecular imaging, disease diagnosis, and therapy.

Organism-targeting peptides, which can selectively bind to a specific type of organism with high affinity, have been derived from several different origins. One way to discover organism-targeting peptides is to use peptides that are ligands for specific cell-surface receptors. A good example of this is RGD (Arg-Gly-Asp) and its derivatives.27,29–35 RGD is also one of the first tumor-homing peptides that was discovered by randomly synthesizing portions of the amino acid sequence from fibronectin.36,37 RGD shows a high selectivity and strong affinity to the integrins that are highly expressed on the surface of some kinds of cells such as cancer cells and is useful in a number of applications.38–41 This method of identifying peptides is based on guessing and checking, which can be very cumbersome for larger peptide sequences. Therefore, more efficient methods have gained interest. Some of the most effective strategies for discovering novel targeting peptides are evolutionary screening virus-peptide display techniques.42–48 For example, through biopanning with phage, the well-known RGD motif has been rediscovered by Arap et al. as a longer sequence, CDCRGDCFC.49 This has become a famous sequence now called RGD-4C.41,49,50 Here, we will review these techniques including how they have been utilized to discover new organism-targeting peptides, as well as their applications in diagnosis, detection, and therapy. To date, there has not been a clinically focused review of the use of these virus-derived peptides for diagnosing, detecting, or treating viral, bacterial, parasitic, yeast, and fungal infections as well as other diseases in humans (Figure 1). Despite the massive potential impact of such treatments worldwide, this topic is relatively new and upcoming and has thus not been covered yet. Table 1 gives a few examples of human clinical trials involving virus-derived peptides. Additionally, an overview of the available virus-derived peptides can be found in Tables 2 (pathogen targeting), 3 (human cell-targeting), and 4 (tissue-targeting).

Figure 1.

Overview of clinical applications of virus-derived peptides. (A) Targeted drug transport. Virus-derived peptides can be used in a wide range of targeted treatment strategies. The peptides can provide targeting capabilities and allow for transport across physical barriers such as the blood–brain barrier or tympanic membrane. (B) Vaccines. Deriving a peptide that can serve as a vaccine is a multistep process. Typically, this involves biopanning against antibodies isolated from a diseased patient. The selected peptides, which mimic the original pathogen, are then displayed on a human-safe virus. This safe virus will then generate an immune response that will apply to both the mimetic and original pathogen, thus serving as a vaccine. (C) Pathogen therapeutics. Peptides derived from viruses can have antipathogenic effects. For example, the peptide MAAKYN was shown to inhibit the growth of the pathogen Leishmania major in BALB/c mice.51 (D) Targeted cancer therapies. Virus-derived peptides have been widely implemented in cancer diagnosis and imaging, as well as the targeted delivery of drugs to treat cancer. (E) Targeted gene therapy. Targeting peptides for gene therapy are not only derived from viruses, but in the case of adenovirus biopanning, the same virus selected from the biopanning process is subsequently employed for the gene-therapy application. (F) Disease detection. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) are often used for disease detection. A patient potentially suffering from a disease such as tuberculosis can have his or her serum quickly tested for the presence of this disease. If the disease is present, peptides (displayed on a human-safe virus) selected for binding to the disease specific pathogen will bind to the pathogen in the serum sample. A two-antibody detection system (often also involving horseradish peroxidase and 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine) can then be used to determine if the human-safe virus has bound to the potential target. If the target binding occurs, light is emitted, which can be detected, and the patient is diagnosed to have the disease.

Table 1.

Examples of Virus-Derived Peptides in Clinical Trials for Humans

| status/year | study title | brief description | condition | virus type used to discover peptides | reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| recruiting participants as of November, 2016 | Electro-Phage and Colorimetric Aptamer Sensors for Clinical Staging and Monitoring of Bladder Cancer | seeks to identify a molecular fingerprint (peptide) capable of detecting recurrent bladder cancer using phage-display technology | bladder cancer | phage-display library to be used | 52 |

| not yet recruiting as of July, 2016 | Peptide-Drug-Conjugates for Personalized, Targeted Therapy of Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia | will use phage libraries to isolate phages specifically internalized by chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells taken from newly diagnosed and untreated patients; following treatment options will then be tailored to the specific patient’s results in terms of binding peptides isolated from each patient’s individualized biopanning study | chronic lymphocytic leukemia | phage-display library to be used | 52 |

| study is ongoing as of April, 2014 | Gluten-free Diet in Gluten-Genetically Predisposed Subjects | will measure gluten-dependent humoral immune response by means of phage-display libraries before and after 12 months of a gluten-free diet; seeks to demonstrate the mucosal gluten-dependent response in relation to a gluten-free diet; will also evaluate the targeting specificity of a double staining technique for detecting IgA antitransglutaminase mucosal deposits utilizing antibody fragments developed through phage display | celiac disease | phage-display library to be used | 52 |

| study completed, 2002 | Steps toward Mapping the Human Vasculature by Phage Display | carried out on a 48-year-old male Caucasian patient with the intention of mapping the human vasculature system in terms of finding homing peptides for all tissue targets | intended not for just one condition but to create a molecular targeting map for the human vasculature system usable for future clinical applications | M13 phage CX7C library | 53 |

| study completed, October 2015 (should be noted that there are a large number of clinical trials using this virus derived peptide; this is just one example) | Study of AMG-386 in Combination With Paclitaxel and Carboplatin in Subjects with Ovarian Cancer | Trebananib (AMG-386) is a peptibody discovered through phage display that blocks the interaction between angiopoietin-1 and angiopoietin-2; blocking this interaction reduces angiogenesis and therefore the growth of tumors; evaluated was a combined treatment using AMG-386 with paclitaxel and carboplatin as a treatment for stages II–IV of epithelial ovarian, primary peritoneal, and fallopian tube cancers | stages II–IV of epithelial ovarian, primary peritoneal, and fallopian tube cancers | three filamentous phage libraries were used called TN8-IX, TN12-I, and Linear (1.0 × 1010 independent transformants) | 52, 54 |

| study completed February, 2015 | DNX-2401 (Formerly Known as Delta-24-RGD-4C) for Recurrent Malignant Gliomas | phage library derived sequence CDCRGDCFC (often called DNX-2401 or 24-RGD-4C) homes to multiple tumor types (including carcinoma, sarcoma, and melanoma); study was to determine the highest tolerable dosage and to determine the effect of the peptide on tumors | brain tumors | phage library | 49, 52 |

Table 2.

Pathogen-Targeting Peptides Derived from Virus Libraries

| pathogen | viral library//virus type | targeting peptide sequence | applications | ref | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| parasite | Rhipicephalus (Boophilus) microplus (cattle tick) | fUSE5/15-mer//M13 phage | RNLWPGDLRWVGWH, RLGPLHFLNAWGHDH | potential targeted chemotherapy/vaccination strategies | 55 |

| Plasmodium (the causative agent of malaria) | XCX8CX//M13 phage | PCQRAIFQSICN | inhibited Plasmodium invasion of salivary gland and midgut epithelia to prevent malaria | 56 | |

| Schistosoma japonicum schistosomula | Ph.D.-12//M13 phage | YSGLQDSSLRLR | exhibited potent schistosomicidal activity in vitro; also a possible drug carrier | 57 | |

| Leishmania major | hexapeptide library//M13 phage | MAAKYN | inhibits L. major growth kinetics in vitro and reduces cutaneous lesions | 51 | |

| yeast/fungus | Candida albicans | Ph.D.-12//M13 phage | ELMAVPVPLPPA, SEYTSQLIFTAT, SEFSYIVIDTSL, ELTAILVSPAPL, ELNAQHIMEPKY, ELIPMLIMQSTS, EDYSTIMKTLAH, STPKSPHSVASH, AVQHNPTHPFYP | rapid, highly specific diagnosis of Candida albicans infection | 58 |

| Candida albicans disease biomarker (antisecreted aspartyl proteinase 2 IgG antibody) | antibody M13 phage-display library//M13 phage | VKYTS | highly sensitive diagnosis and detection of Candida albicans infection (indirectly by looking for the immune response) | 59, 60 | |

| Paracoccidioides brasiliensis | CX7C//M13 phage | CGSYGFNAC | selectively kills only virulent Paracoccidioides brasiliensis yeasts to treat Paracoccidioidomycosis | 61 | |

| virus | Avian influenza A H5N1 | VHH library//M13 phage | AAGPLSWYAHEFLEYSGHEYNY, TEHRGFDDNDYVLPALGARAANY, AAPPLPDCYSGSWSPFTDEYNY | diagnosis of H5N1 infection | 62 |

| Avian influenza A H7N2 | VHH library//M13 phage | see ref for full-length sequences | diagnosis of H7N2 infection | 63 | |

| orthopoxviruses | Ph.D.-12//M13 phage | TADKLLYGLFKS | orthopoxvirus detection | 64 | |

| bacteria | Klebsiella pneumoniae | naïve human single chain fragment variable//M13 phage | see ref; sequences not provided. | Klebsiella pneumoniae antibody therapeutics and vaccines | 65 |

| Listeria monocytogenes | VHH library//M13 phage | AARRGPGTSVLSDDYDY, ATTRTPRVRLPTESREYTY | detection and diagnosis of the foodborne pathogen Listeria monocytogenes | 66 | |

| Salmonella | Ph.D.-12//M13 phage | NRPDSAQFWLHH | rapid Salmonella testing | 67 | |

| E. coli and P. aeruginosa | Ph.D.-12//M13 phage | RLLFRKIRRLKR | bactericidal activity against E. coli and P. aeruginosa | 68 | |

| Staphylococcus aureus | Ph.D.-12//M13 phage | VPHNPGLISLQG | detection and diagnosis of Staphylococcus aureus infection | 68 | |

| Mycobacterium leprae | Ph.D.-12//M13 phage | LEQCQES, LEQCQES | diagnosis and potential vaccine for leprocy | 69 | |

| Mycobacterium tuberculosis | Ph.D.-7//M13 phage | WHLPLSL | diagnosis of tuberculosis | 70 |

2. VIRAL LIBRARIES

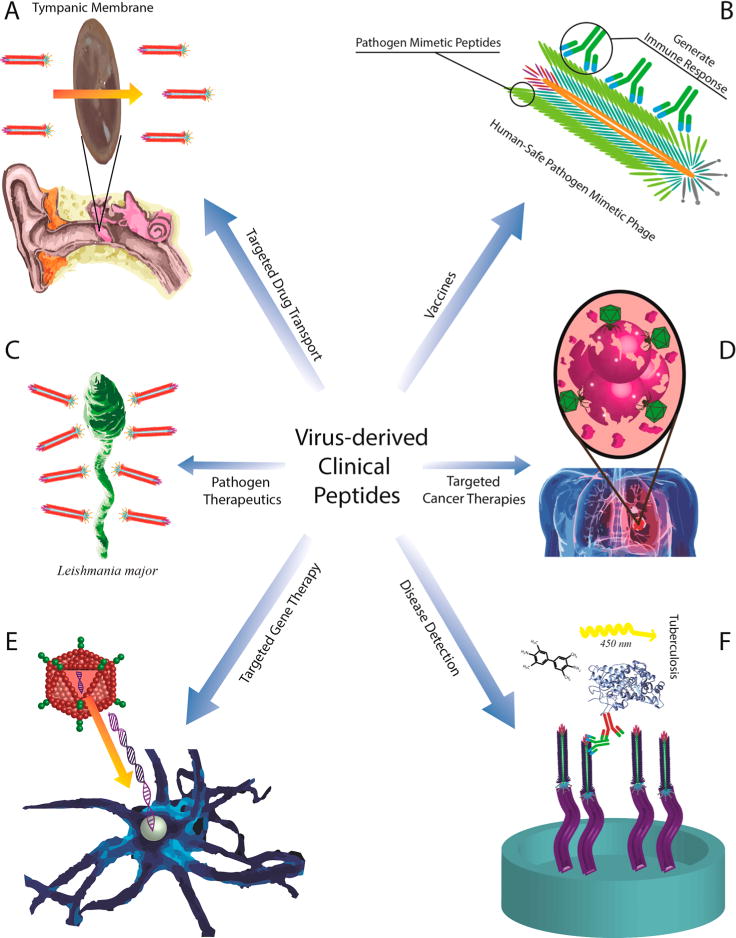

Virus-peptide libraries are a mixture of millions of virus particles where each virus displays a unique and random set of peptides. There are two major types of viral libraries, one based on nonlytic or lytic bacteriophages (phages) and another based on adeno-associated viruses (AAVs). Filamentous fd and M13 phages, which are nonlytic bacteria-specific viruses (and are very similar in structure and morphology to each other), are the most widely adopted phages in phage-display techniques.109–112 They have a rodlike shape that is ∼800 nm in length and ∼6 nm in width (Figure 1).113 The circular, single-stranded DNA genome is surrounded by a protein sheath consisting of ∼2700 copies of one major coat protein (pVIII) and 5 copies each of four minor coat proteins (pIII and pVI on one tip and pVII and pIX on the other tip).114 These coat proteins are encoded by corresponding genes located in the DNA genome. Foreign DNA that encodes for foreign peptide expression can be inserted into the phage genome to display any desired peptides on the surface of the protein sheath.43,115,116 In other words, a foreign peptide can be fused to minor and/or major coat proteins to site-specifically display at the end and/or along the side wall of phage particles by DNA engineering methods. Lytic phages such as T7 phages have also become widely used.117–120 Since phage display was introduced by George P. Smith in 1985,121 this technique has proved to be one of the most powerful approaches for selecting affinity ligands, including cell/tissue and pathogen-targeting peptides.122 Nowadays, phage display has been further developed in combination with other techniques, such as microfluidics or better analysis software, to improve its selection efficiency.74,123–125 The most widely used phages for phage display are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Phage display on M13 and T7 phages. For M13 phage, the 5 copies of pIII are usually utilized in phage libraries for biopanning. After a desired targeting sequence is obtained, that sequence may be genetically engineered into another M13 phage to be displayed on the much more plentiful pVIII. Biopanning is frequently done with pIII rather than pVIII for M13 phages. For T7 phage, the capsid is composed of 415 copies of the coat protein 10A and/or 10B. Through phage display, ∼5–15 copies of the genetically engineered peptide sequence will be displayed on the C-terminus of capsid 10B.126

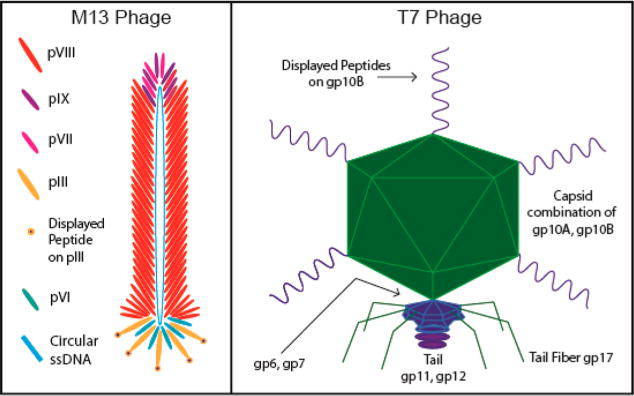

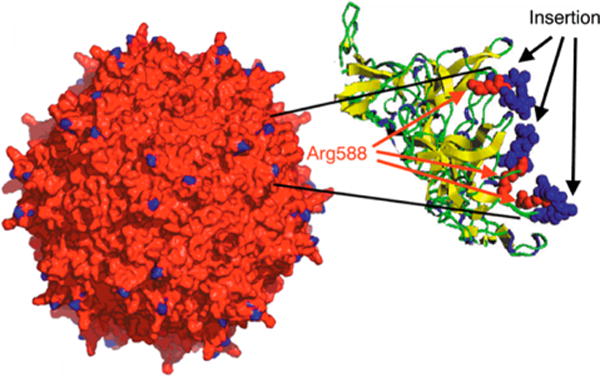

Adeno-associated virus type 2 (AAV2) libraries are an exciting alternative to phage-display libraries.127–131 AAV2 belongs to the family Parvovirdae and measures roughly 22 nm in diameter. This virus does infect humans (and other primates) but is not currently known to cause any diseases and only elicits a very mild immune response in humans as demonstrated by phase I clinical trials.132 AAV2 is also a replication-defective virus (the coding genes for replication are defective, thus preventing further replication and the lytic pathway to cell lysis), making it ideal as a gene-therapy vector.128,133–136 In fact, there are even AAV2 products that are approved (by European Union) for human use in commercial gene therapy, such as Glybera that can control the production of lipoproteinlipase (which is necessary for processing and clearing fat-carrying chylomicron after eating fat-containing foods).137 Incredibly, adenovirus vectors have been used in 22% of all gene-therapy clinical trials to date.138 Several sites are available within the AAV2 capsid that allow for the incorporation of targeting peptides. Such sites enable the use of AAV2 to make a viral library much like phage libraries. AAV2 peptide libraries are primarily used in gene-therapy applications and are typically better for gene-therapy applications than phage libraries. With phages, the peptides discovered may not be used in the same context (attached to phages), and using the free form of these peptides without the phages may cause them to behave differently in terms of binding conformations. With the AAV2, peptides will not behave differently in the actual gene-therapy application because they stay displayed on AAV2 in the same manner as was selected from the AAV2 library (Figure 2) rather than often being used as free peptides (which happens more frequently with phages). That is to say, isolated peptides are synthesized individually rather than grouped together in their conformation on the surface of a virus when it comes to most phage-derived gene-therapy peptides. Additionally, even if a gene-therapy vector is created from a phage, the vector may not internalize properly for gene transduction nearly as well as AAV2 because phages do not naturally infect human cells.128 As AAV2 naturally infects human cells, these problems can be overcome naturally when applied to gene-therapy techniques if the whole virus is used, thus eliminating the issues of not having the targeting peptides in the same spatial context as the selection for targeting was done. With AAV2 libraries, peptides can be selected for a particular gene-therapy target without changing the vector to be used in the actual gene therapy. In addition, recent work has shown that gene-delivery systems using AAV2 can be tuned to have varying efficiencies as desired. For example, Gomez et al. demonstrated a system that can control AAV2 gene-delivery efficiency using a setup that is dependent on an external light stimuli.139 Modulating the ratio of red to far-red light allows for controlling the activation of a light-switchable protein, phytochrome B, as well as a light-dependent interaction partner (phytochrome interacting factor 6). Thus, light can be used to allow tunable control of the efficiency of AAV2 gene delivery from 35% to 600% (relative to unengineered AAV2). This control may be helpful for dosage-related applications. For these reasons, AAV2 libraries are becoming more popular in peptide-targeted gene-therapy applications. A representative example of AAV2 display is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Topology of the AAV2 capsid. Blue indicates position of the seven additional random amino acid residues near the distal portions of the 3-fold spikes on the AAV2 capsid surface. The inset shows a cross section through a spike region at a higher resolution with Arg588 shown in red and the adjacent seven amino acids (derived from the library insertion) shown in blue.128 Adapted with permission from ref128. Copyright 2003 Nature Publishing Group.

There are also hybrid AAV libraries created by shuffling the DNA of the capsid genes of several different AAVs. The commonly used library for this is generated through shuffling the capsid genes for AAV 1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 8, 9, rh8, rh10, rh39, and AAVrh43. This technique allows for a maximum theoretical diversity of 2 × 107 capsids for this library.108 This type of library was designed for the purpose of generating designer vectors, which are capable of transducing a greater variety of cell types during in vivo selection.108 Its greater diversity (compared to traditional AAV2 libraries, which typically have a diversity of 106 for their capsids140) is intended to also help with the inherent heterogeneity that exists between animals of the same species used during each cycle of selection in vivo.108

3. SELECTING ORGANISM-TARGETING PEPTIDES BY VIRUS-PEPTIDE DISPLAY

Organism-targeting peptides can be evolutionarily selected by allowing the aforementioned viral libraries to interact with the target organisms in vitro, ex vivo, or in vivo (Figures 4 and 5). By using such a virus-peptide display technique, virus-derived peptides targeting pathogen (Table 2), human cells (Table 3), and tissues (Table 4) can be discovered and widely applied in human disease diagnosis and therapy.

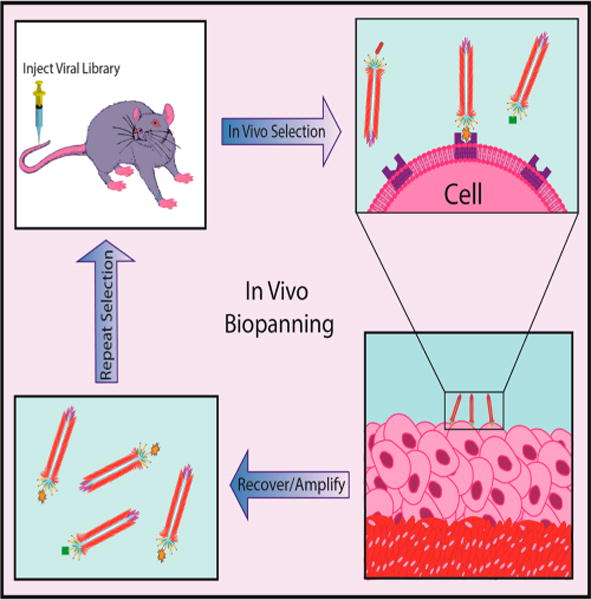

Figure 4.

In vivo phage biopanning concept. A phage library displaying roughly one billion different combinations of peptides is injected into an animal model. Phages can migrate to their target organs, tissues, receptors, disease cells, etc. for which their peptides have the highest affinity. The phages are then recovered from the animal model by harvesting the desired target, such as a specific organ. The phages are then amplified and go through additional rounds of selection. After 3–4 rounds of selection, phages are sequenced to identify the high-affinity peptides achieved.

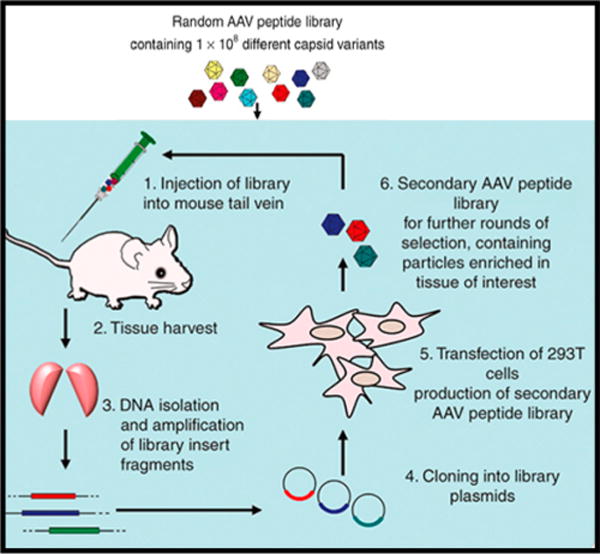

Figure 5.

In vivo peptide-selection strategy using an AAV2 library. First, an AAV2 library is injected into the animal model. The tissue of interest is then harvested after 6 days. Library insert fragments from the AAV2 library in the DNA are isolated and amplified using a polymerase chain reaction. The insert DNA is then cloned into plasmids and transfected into 293T cells to produce a secondary AAV2 library for the next round of selection (typically 2–5 rounds).105 Adapted with permission from ref105. Copyright 2016 Elsevier.

Table 3.

Summary of Human Cell-Targeting Peptides Derived from Virus Libraries

| organism/cell type | viral library | targeting peptide sequence | applications | ref | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cancer cells | human breast carcinoma SKBR-3 | f8/8 landscape//M13 phage | VSSTQDFP | SKBR-3 breast cancer cells internalization | 71 |

| basal cell adhesion molecule (BCAM) and laminin subunit alpha 5 (LAMA5) of human colorectal cancer cells | Ph.D.-7//M13 phage | ASGLLSLTSTLY, SSSLTLKVTSALSRDG | impairs adhesion of KRAS mutant colorectal cancer cells to endothelial cells | 72 | |

| esophageal cancer cells | Ph.D.-12//M13 phage | RALAHPRDHPDL, ATCSMLLSRNEA | early screening of esophageal cancer | 73 | |

| PPC-1 human prostate carcinoma cell | T7 library//T7 phage library | (R/K)XX(R/K) | PPC-1 human prostate carcinoma cell targeting | 74 | |

| PC3 human prostate cancer cells in vitro and in vivo | Ph.D.-12//M13 phage | KQFSALPFNFYT | targeted delivery of doxorubicin to prostate cancer cells | 75 | |

| colon cancer cell line SW480 | Ph.D.-7//M13 phage | VHLGYAT | imaging | 76 | |

| U87MG malignant glial cell line | Ph.D.-12//M13 phage | VTWTPQAWFQWV | drug delivery | 77 | |

| hepatocellular carcinoma cell line BEL-7402 | Ph.D.-12//M13 phage | AGKGTPSLETTP | drug delivery | 78 | |

| cervical carcinoma | CX9C//M13 phage | C(R/Q)L/RT(G/N)XXG(A/V)GC | drug delivery | 79 | |

| human colorectal cell line WiDr | Ph.D.-12//M13 phage | HEWSYLAPYPWF | gene delivery | 80, 81 | |

| neuroblastoma and breast cancer cell | Ph.D.-12//M13 phage | VPWMEPAYQRFL | imaging | 82, 83 | |

| acute myeloid leukemia cells | X7 AAV2//adeno-associated virus 2 | NQVGSWS | acute myeloid leukemia gene therapy | 84 | |

| HO-8910 ovarian cancer cells | Ph.D.-7//M13 phage | NPMIRRQ | potential ovarian cancer diagnosis tool | 85 | |

| human gastric adenocarcinoma cancer cells | Ph.D.-12//M13 phage | ETAPLSTMLSPY | peptide can bind to the surface of gastric adenocarcinoma cancer cells and reverse their multidrug resistance | 86 | |

| IHKDKNAPSLVP | high affinity and specificity binding to gastric adenocarcinoma cancer cells | 87 | |||

| HO-8910 ovarian cancer cells; promiscuous ligand targeting of lung and pancreatic cancer cells | Ph.D.-C7C//M13 phage | SWQIGGN | control of ovarian cancer cell migration, viability, invasion, and adhesion capacity | 88 | |

| F8/9//M13 phage | GSLEEVSTL, GEFDELMTM | promiscuous ligand targeting of lung and pancreatic cancer cells for targeted doxorubicin delivery | 89 | ||

| stem cells | primate embryonic stem cells | Ph.D.-12//M13 phage | APWHLSSQYSRT | imaging | 90 |

| human mesenchymal stem cells | Ph.D.-7//M13 phage | EPLQLKM | recruitment of hMSCs | 91 | |

| human pluripotent stem cell-derived progenitor cell lines | Ph.D.-12//M13 phage | EWLFEFPTPVDA, DWIATWPDAVRS | cell isolation | 92 | |

| adult neural stem cell surface receptors (one or more) | Ph.D.-7//M13 phage | KLPGWSG | enhanced neural stem cell neuronal differentiation in vitro | 93 | |

| human embryonic progenitor cell line W10 | Ph.D.-12//M13 phage | DWLWSFAPNVDT | imaging | 94 |

Table 4.

Summary of Tissue-Targeting Peptides Derived from Virus Libraries in Preclinical or Clinical Trials

| tissue type | viral library | targeting peptide sequence | applications | ref | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| tumor | MDA-MB-435 breast carcinoma xenografts | CX7C//T7 phage | CGNKRTRGC | MDA-MB-435 breast carcinoma xenografts targeting | 95 |

| tissues | p32-expressing breast tumors | CX7C//T7 phage | CKRGARSTC | drug delivery to p32-expressing breast tumors | 96 |

| gastric tumor tissues | Ph.D.-12//M13 phage | AADNAKTKSFPV | imaging | 97 | |

| bladder tumor tissues | CX7C T7//T7 phage | CSNRDARRC | imaging | 98 | |

| Ph.D.-C7C//M13 phage | CSSPIGRHC | imaging | 18 | ||

| vasculature of human gastric cancer | Ph.D.-C7C//M13 phage | CGNSNPKSC | imaging | 99 | |

| human lung adenocarcinoma | CX7C//M13 phage | CAKATCPAC | imaging | 100 | |

| CX7C//M13 phage | LYANSPF | imaging | 101 | ||

| other tissues | brown adipose tissue | mixture of cyclic CX7C and CX8C//M13 phage | CPATAERPC | imaging | 102 |

| normal breast tissue | CX7C//T7 phage | CPGPEGAGC | breast tissue targeting | 103 | |

| ischemic stroke tissue | CX7C//phage T7 | CLEVSRKNC | imaging | 104 | |

| endothelium of the pulmonary vasculature | X7AAV2//adeno-associated virus 2 | ESGHGYF | gene delivery | 105 | |

| tympanic membrane transport to middle ear tissue | Ph.D-12//M13 phage | SADSTKTTHLTL | targeted transportation across the tympanic membrane to the middle ear for patients infected with otitis media | 106 | |

| brain microvasculature endothelial cell tissue | heptapeptide AAV2//adeno-associated virus 2 | NRGTEWD | targeted gene-therapy vector able to ameliorate severe cerebrovascular pathology of incontinentia pigmenti | 107 | |

| central nervous system and other tissues including brain, spinal cord, muscle, pancreas, and lung tissues | AAV capsid library//adeno-associated virus 1 | VDFAVNTEGVYSEPRPIGTRYLTRNL | targeted gene therapy for the central nervous system and other tissues including brain, spinal cord, muscle, pancreas, and lung tissues | 108 | |

| human bone marrow | CX7C//M13 phage | GGG, GFS, LWS, ARL, FGG, GVL, SGT | peptide motifs were isolated from a human patient in vivo to map potential targets of the vasculature system | 53 | |

| human fat tissue | EGG, LLV, LSP, EGR, FGV | ||||

| human prostate tissue | AGG, EGR, GER, GVL | ||||

| human skin | GRR, GGH, GTV, ARL, FGG, FGV, SGT |

Cell/tissue-targeting peptides can be selected from a phage library containing up to 109 phage clones, with each clone displaying a unique and random peptide, through an evolutionary screening process called biopanning.42,115,141,142 The general biopanning procedures for discovering cell/tissue-targeting peptides from a phage library are as follows.71,143–145 First, an input phage library containing billions of phage clones with randomly displayed peptides is incubated with target cells or tissues. Some phages bind to and/or internalize into target cells/tissues while others do not during incubation. Second, a washing buffer is used to remove the weakly bound and unbound phages from the cell/tissue surface. Third, the cell/tissue-targeting phages are eluted from the target cells/tissues using an elution buffer (or cell-internalized targeting phages are isolated from the cells using a lysis buffer). Fourth, the eluted cell/tissue-targeting phages are biologically amplified by infecting E. coli bacteria that are cultured and used to enrich the selected phages. The process from step one to step four is designated as one round of selection. The enriched library is considered as an output for the previous round. The enriched library is used as a new input for the next round of selection. After 3–5 rounds of selection, the foreign DNA insert-coding region in a phage genome is sequenced to determine the peptides that are expressed on the phages. This is possible because the displayed peptides are genetically encoded by the phage genome (Figure 4).

AAV2 libraries contain up to 108 different capsid variants for selection. The overall concept of biopanning is very similar to phage libraries. For AAV2 libraries, the application is typically for tissue-directed gene therapies. Therefore, this example will be for in vivo biopanning. First, an AAV2 library is injected into the animal model. The tissue of interest is then harvested after 48 h. Library insert fragments from the AAV2 library in the DNA are isolated and amplified using a polymerase chain reaction (PCR). The insert DNA is then cloned into plasmids and transfected into 293T cells to produce a secondary AAV2 library for the next round of selection. After 2–5 rounds of selection, dominant (most frequently present) peptides are characterized. An example of AAV2 library biopanning is shown in Figure 5.105

4. VIRAL-INFECTION DETECTION AND DIAGNOSIS

4.1. Avian Influenza A

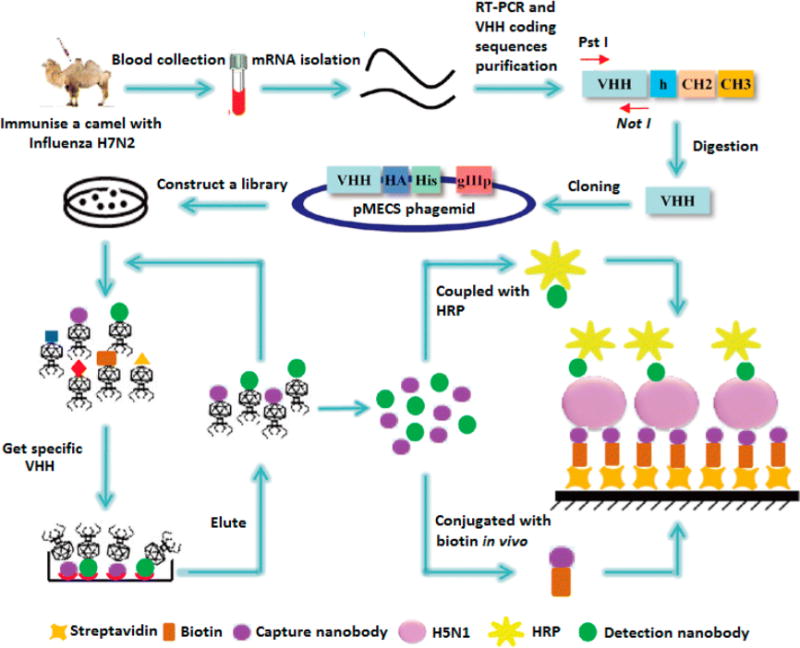

Phage-display technology has contributed a great deal of techniques for the diagnosis and detection of viruses that have plagued human health on a global scale. For example, the influenza virus belonging to the family Orthomyxoviridae contains three genera: influenza A, B, and C. Avian influenza A is of particular interest as it is highly contagious among poultry, birds, and other animals including humans.8,146 The influenza A viruses have been classified into several subtypes for which the rapid and precise diagnosis of these infections can be laborious and time-consuming, demands appropriate laboratory facilities, and is expensive.9 Recently, phage-display technology has been used to create a rapid, sensitive, and low-cost detection system for the influenza strain H5N1.62 Briefly, nanobodies (the targeting peptides specific to the H5N1 virus) were selected using variable fragments of the camelid single-domain antibodies (VHHs) phage-display library. The selected peptide sequences were AAGPLSWYAHEFLEYSGHEYNY, TEHRGFDDNDYVLPALGARAANY, and AAPPLPDCYSGSWSPFTDEYNY. An enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) detection system was then established. To do this, the nanobody was biotinylated and directionally captured by streptavidin-coated ELISA plates capable of specifically capturing the H5N1 virus. Another nanobody conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP) was then used to create the color change associated with detection of H5N1. The full method is illustrated in Figure 6.62 In addition to detecting H5N1, the same group has also developed a system capable of detecting the influenza strains H7N2 and H3N2 using similar methods.7,62,63

Figure 6.

Overview of the selection process for determining VHHs specific to H5N1. All VHH genes specific to H5N1 were selected out of an immunized dromedary. Horseradish peroxidase, along with the various nanobodies coupled to biotin, were used in the detection strategy. The biotinylated nanobodies could be directionally captured by streptavidin in the microtiter plates. Essentially, the biotinylated nanobody (attached to streptavidin) would capture the H5N1 virus, and then another nanobody conjugated to horseradish peroxidase would allow for the detection of the assembly by measuring the absorbance at 450 nm.62 Reproduced with permission from ref62. Copyright 2014 Springer.

4.2. Orthopoxviruses

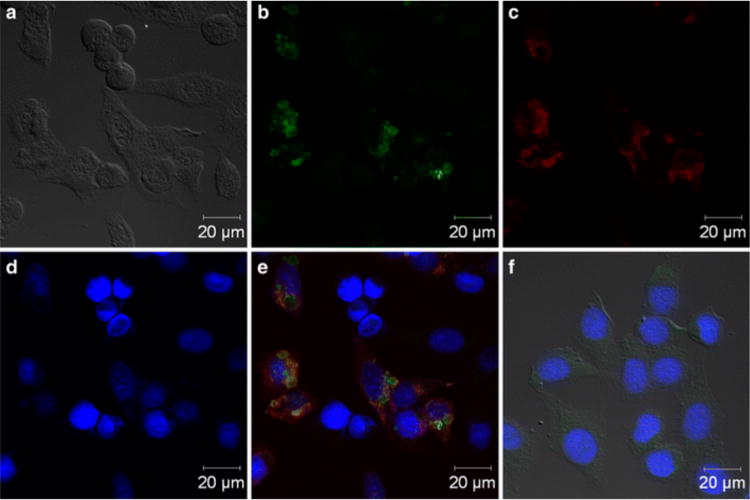

The availability of rapid and reliable detection methods for orthopoxviruses can be highly valuable. After the eradication of the human-specific variola virus (smallpox), only the zoonoses (examples include Ebola virus, salmonellosis, and influenza) are still around. Some orthopoxviruses among the zoonoses, such as cowpox and monkeypox, have the ability to infect nonreservoir species and will transfer to humans.6,146,147 Through phage display and biopanning with a Ph.D.-12 phage-display peptide library kit (M13 phage), a peptide was isolated that was capable of binding orthopoxviruses including vaccinia virus, cowpox virus, monekypox virus, and potentially additional orthopoxviruses. The peptide, TADKLLYGLFKS, was extensively tested for binding by ELISA, surface plasmon resonance, nanoscale liquid chromatographic tandem mass spectrometry, peptide-based immunofluorescence, Western Blot, and electron microscopy. In addition to binding the virus itself, the peptide could also be used to selectively identify cowpox-infected HEp-2 cells by fluorescence microscopy, as shown in Figure 7. These data make the discovered peptide very promising in detecting and diagnosing these dangerous pathogens.64

Figure 7.

Peptide TADKLLYGLFKS can be used in the fluorescence labeling of cowpox-infected HEp-2 cells. (a) Bright-field image of cells. (b) Green fluorescent image of cells on glass slides incubated with the peptide and streptavidin–fluorescein isothiocyanate. (c) Cells were also incubated with a polyclonal anti-D8 antibody coupled to DyLight 649 (shown in red) to assess colocalization. (d) The nuclei of cells were stained by DAPI (blue). (e) Overlay of b, c, and d showing all stains. (f) Noninfected stained HEp-2 cells (control) do not show fluorescence.64 Reproduced with permission from ref64. Copyright 2014 Springer.

5. BACTERIAL INFECTION DIAGNOSIS AND THERAPEUTICS

5.1. Klebsiella pneumoniae

Treating multidrug-resistant bacterial infections has become a major challenge in modern medicine. Gram-negative infections, such as Klebsiella pneumoniae, are among the most problematic because of their multidrug-resistance issues.148 Antimicrobial drugs for Klebsiella pneumoniae are greatly needed.149–151 Multidrug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae infections have now spread worldwide and have left clinicians with few options for current or near-future therapeutic alternatives. To resolve this problem, recent work has turned to phage-display technology to identify potential protective antibody fragments against Klebsiella pneumoniae. Using a naïve human single chain fragment variable-phage library (M13 phage), binding sequences were determined and further investigated to identify their common target antigen to be MrkA.65 MrkA is a major protein within the type III fimbriae complex.65 After the third round of biopanning, the output sequences were batch-converted into a scFV-Fc format, which carried a human IgG1 Fc fragment. This fragment was suitable for the subsequent higher-throughput as well as functional screens that were completed. A detailed approach on how to convert scFvs from biopanning into scFV-Fc fusion proteins expressed in mammalian cell lines can be found in the literature.152 These results were then used to create serotype-independent MrkA antibodies, which were shown to reduce biofilm formation of Klebsiella pneumoniae in vitro (by activating an immune response) and confer protection against Klebsiella pneumoniae in multiple murine pneumonia models. Immunization with purified MrkA proteins in mice was shown to reduce the bacterial burden of Klebsiella pneumoniae, leading to a potential target for therapeutics and vaccines.65

5.2. Listeria monocytogenes

Listeria monocytogenes is a Gram-positive rod-shaped bacterium. This bacterium is commonly present in ready-to-eat foods, which require no further cooking.153,154 It can grow under harsh conditions at temperatures as low as 4 °C, as acidic as pH 4.4, and at salt concentrations ranging up to 10% NaCl.66,155 Infection by Listeria monocytogenes is a leading cause of death among foodborne illnesses. The mortality rate for Listeria monocytogenes ranges from 20 to 30%.66 Recently, two novel Listeria monocytogenes specific phage clones were developed and isolated from a phage-display antibody fragment library (M13 phage) derived from the variable domain of heavy-chain antibodies of immunized alpaca. The resulting antibody fragments (with peptide sequences AARRGPGTSVLSDDYDY and ATTRTPRVRLPTESREYTY) created through phage-display technology were able to detect the three serotypes of Listeria monocytogenes (1/2a, 1/2b, and 4b) responsible for 95% of documented human infections. The method used to detect the pathogen was an ELISA. The detection limit was 1 × 104 colony-forming units per milliliter, providing a new diagnosis and detection tool for Listeria monocytogenes.66 While this technique does not have as low of a detection limit as established PCR techniques, it is cost-effective.66,156

5.3. Salmonella

Salmonella comprises two species, bongori and enterica, and often infects humans through food consumption.157 Of the two, >99% of human Salmonella infections are from the subspecies enterica. While a variety of techniques are available for detecting Salmonella such as antibody techniques and real-time PCR, cheaper, more reliable techniques are still needed.158,159 Recently, phage-display biopanning (with M13 phages) was used to select peptides against gamma-irradiated whole Salmonella cells. After 4 rounds of panning and extensive testing, the sequence NRPDSAQFWLHH was found to be most effective.67 This peptide was then chemically synthesized and coupled to MyOne tosylactivated Dynabeads. The ability of the peptide to capture whole Salmonella cells from nonenriched broth cultures was then quantified by magnetic separation + plate counts, as well as by magnetic separation + Greenlight. Of these methods, the magnetic separation + Greenlight technique allowed for detections as low as 10 Salmonellae per milliliter, which may be sufficient to eliminate the need for pre-enrichment techniques in screening for Salmonella, thus speeding up the detection process (by a minimum of 8 h when compared to prevailing enrichment techniques).67,160 This Greenlight system was developed by Luxcel Biosciences Limited and involves an oxygen-sensitive fluorescent probe (Greenlight probe). The probe’s signal increases when oxygen levels decrease (due to bacteria presence), and a certain threshold time is measured. This threshold time corresponds to the minimum time necessary to get the first measurable change in oxygen levels for the sample compared to a pre-established standard curve for a target bacterium. Thus, after capturing Salmonella on the peptide-coated Dynabeads, the Salmonella could be concentrated by a magnetic separation and the concentration of bacteria could be determined using the Greenlight system (fluorescence levels directly correlate with Salmonella concentration due to oxygen consumption by the Salmonella).67

5.4. Staphylococcus aureus

Staphylococcus aureus is an opportunistic pathogen implicated in life-threatening diseases such as osteomyelitis, toxic shock syndrome, and endocarditis.161 This pathogen is one of the major causes of wound infections and also arises as a complication during transfusion medicine techniques.162 Existing methods for rapid detection are mainly reliant on antibodies and bioprobes, which can be tedious and expensive while having unintended cross-reactions. Recently, a synthetic peptide was developed utilizing phage-display technology (M13 phage) for the detection of Staphylococcus aureus bacteria. The peptide, VPHNPGLISLQG, was evaluated for its potential binding using immunoblot assays, ELISA, and a dot-blot. The diagnostic potential was also evaluated in human platelet samples spiked with Staphyloccus aureus. The peptide was able to detect roughly 100 organisms per milliliter of spiked human platelet samples (in an ELISA), making it a potential clinical diagnostic method for detecting Staphyloccus aureus infections.68

5.5. Leprosy

Leprosy is caused by a chronic granulomatous infection from the bacteria Mycobacterium leprae. The disease affects the skin and peripheral nervous system. Treatment for leprosy is difficult due to a slow growth rate and long incubation periods of 3–10 years as well as their ability to escape a host’s defense mechanism.69 Multiple strains and drug-resistance development have made the problem even worse. In addition, Myobacterium leprae does not grow well in culture media. This makes fully assessing its antigenic structure for producing a vaccine difficult. To circumvent these issues, specific anti-Myobacterium leprae antibodies were isolated from 34 patients suffering from lepromatous leprosy and subsequently used in biopanning with a Ph.D.-12 phage-display library to select peptide sequences that could mimic the bacteria. These peptides can then be used to generate a potential vaccine against leprosy. Their potential was then evaluated for their ability to induce an anti-Leprae humoral response in mice. Specifically, the peptide epitope, LEQCQES, may be capable of being implemented in an early diagnosis technique for leprosy. These peptides were also able to invoke an anti-Leprae immune response in Balb/c mice, demonstrating their potential application as a vaccine.69

5.6. Tuberculosis

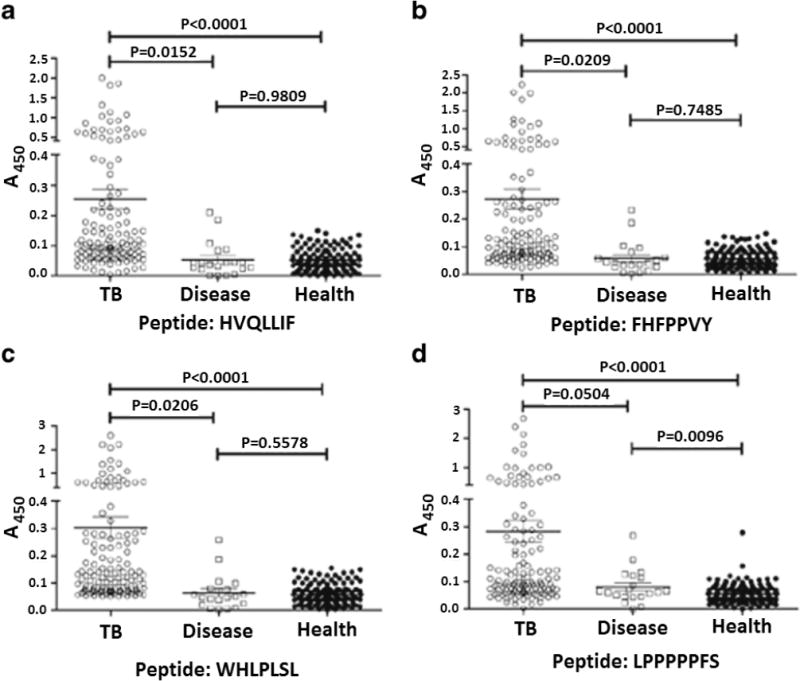

In 2013, tuberculosis was estimated to infect roughly 9 million people and killed 1.5 million people.163 The early diagnosis of tuberculosis is essential in limiting the infection within a person and providing early treatment. Traditional bacteria-culturing diagnosis takes 6–8 weeks. However, serological antibody detection techniques available in more developed countries can be done on a much faster time scale.163 Moreover, current commercially available tuberculosis antibody based tests continue to produce inconsistent results in terms of sensitivity and specificity.163 Therefore, alternative strategies are needed. Recently, phage-display technology was used to develop a short peptide, WHLPLSL, capable of serologically detecting Myobacterium tuberculosis to diagnose tuberculosis.70 The peptide was examined for its detection ability (in an ELISA test) using the sera from 47 tuberculosis patients and 37 healthy individuals. This research group had also determined from previous work that an antigen epitope peptide of a protein called mycobacterium protein 64 and a protein called CFP10/ESAT-6 could serve as an alternative corresponding antigen for the serological detection of tuberculosis. Therefore, out of the selected individuals, 12 tuberculosis patients with negative screening results for these 2 proteins were used as screening target sample controls (these patients had tuberculosis, but the previous CFP10/ESAT-6 method failed to detect it). Additionally, 12 healthy patients with similarly negative screening results for these proteins were selected as reverse screening sample controls (patients that did not have tuberculosis and also were negative for CFP10/ESAT-6). These data could serve as a comparison to see if the new detection method with the peptide WHLPLSL was superior to the previously established method (which sometimes failed to detect tuberculosis) of detecting the proteins mycobacterium protein 64 and CFP10/ESAT-6.70,164 It was demonstrated that the peptide, WHLPLSL, was a sensitive detection probe for the diagnosis of tuberculosis. Additionally, 3 other peptides showed promise but were not as effective as WHLPLSL in an ELISA.70 Effectiveness was measured in terms of specificity (ability to correctly identify those without tuberculosis, who are the negative controls) and sensitivity (ability to correctly identify those patients with tuberculosis, who are the positive controls). Therefore, the best treatment option would have both a high sensitivity and a high specificity. All 4 peptides had >90% specificity, but WHLPLSL had the best sensitivity at 54%. That is to say, all 4 peptides did not misdiagnose healthy patients 90% of the time and the peptide WHLPLSL correctly identified tuberculosis 50% of the time. WHLPLSL is comparable to other existing mimotopes and antigens for detecting tuberculosis. It could be possible to combine the results of this new peptide, WHLPLSL, with the previous method of detecting mycobacterium protein 64 and CFP10/ESAT-6 to create an even more reliable method of detection. This could be done by picking the most consistent result among each test. For example, if two of the tests were positive and one negative, we could say that the positive result is more likely to be correct. This would reduce the chance of error. The results are demonstrated in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Detection of tuberculosis from the sera of tuberculosis patients (n = 130), disease control (control group of nontuberculosis patients that had a respiratory infectious disease) (n = 20), and healthy individuals (n = 134). The mean optical density value for each triplicate sample was read 20 min after the addition of a substrate in an ELISA. The scatter plot represents the distribution of IgG levels with respect to the four potential binding peptides. Plates were coated with 4 μg of peptides per well.70 Adapted with permission from ref70. Copyright 2016 Springer.

5.7. Otitis Media

Otitis media is a disease characterized by inflammation and fluid accumulation in the middle ear. Additional symptoms include ear pain, irritability in infants, and fever.165 Although sometimes caused by viruses, it is primarily caused by infection with the bacteria Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, and Moraxella catarrhalis.106 Traditional treatments involve non-localized treatments such as antibiotics, which have additional undesired side-effects. The reason for the lack of local treatments is that the tympanic membrane, which is very difficult to penetrate by nonsurgical means, must be bypassed in order to get to the middle ear. For this reason, an alternative means to transport across the tympanic membrane of patients suffering from otitis media has recently been developed.106 The technique involves using a peptide, SADSTKTTHLTL, developed through in vivo biopanning with a Ph.D-12 phage-display peptide library. The biopanning was carried out using male Sprague–Dawley rats infected with otitis media causing Haemphilus influenza. The library of phages was injected 2 days after the rats were infected with Haemphilus influenza (confirmed by the presence of fluid in the middle ear cavity). The phages were then collected from the middle ear fluid and counted by a standard plaque assay before entering the next round of biopanning. Validation of internalization and transiting efficiency of the selected peptides was determined by incubating specific phages over the tympanic membranes in vivo for 1 h followed by washings and elutions. The transiting efficiency was calculated by comparing the number of phages recovered from the middle ear fluid to the number of phages on the tympanic membrane input side. Additional transports kinetics, saturation, and competitive binding assays were also carried out on the most effective peptide identified, SADSTKTTHLTL. Overall, this study demonstrated the capability of the peptide SADSTKTTHLTL to transport across the tympanic membrane to the middle ear in otitis media infection. The system has the potential to transport otitis media treating drugs (such as antibiotics) across an intact unperforated tympanic membrane for the localized treatment of otitis media.106

6. PARASITE INFECTION TREATMENT AND PREVENTION

6.1. Rhipicephalus (Boophilus) microplus

Parasite species can be the cause of major health consequences for humans. They can be difficult to combat in our food sources. Additionally, parasites often transfer from insects such as ticks and mosquitos to humans. For example, the cattle tick, Rhipicephalus (Boophilus) microplus, is an ectoparasite (a parasite that lives on the outside of its host) in tropical and subtropical countries. Synthetic acaricides (pesticides toxic to the arachnid subclass, Acari, which includes ticks) and chemotherapy are the current treatments, but certain resistant tick populations have developed. Recently, phage display was used to develop 15-mer peptides (such as RNLWPGDLRWVGWH and RLGPLHFLNAWGHDH) capable of preferentially binding to either the eggs or larvae of the parasite. By identifying these binding peptides, future treatment opportunities will now be able to selectively target this parasite. The result is a proof of concept for utilizing phage-display technology, which could be applied to a wide range of other parasitic species, to provide suitable targets for vaccination and chemotherapy strategies.55

6.2. Malaria

Malaria is a devastating parasite often transmitted through mosquitos to humans and other animals. Plasmodium is a causative agent of malaria necessary to complete the life cycle of malaria in mosquitos, making it a valuable target for malaria prevention. Using phage display, a 12-mer peptide (PCQRAIFQSICN) was developed that is capable of strongly inhibiting the Plasmodium invasion of the salivary gland and midgut epithelia in mosquitos, thus impeding the life cycle of malaria.56 Inhibition was a result of the peptide and sporozoites (the spore-like infective stage in the life cycle of the malaria parasite) recognizing the same ligand necessary for invasion of the salivary gland.

6.3. Schistosomiasis

Schistosomiasis is a tropical parasitic disease. Schistosomiasis infects up to 200 million people worldwide.57 Schistosomiasis is caused by the blood flukes S. hemeetobium, Schistosoma mansoni, and S. japonicum. The parasitic infection is known to cause anemia, impaired cognition, stunted growth, and decreased physical fitness.10 The current leading treatment of Schistosomiasis is chemotherapy with praziquantel.10 Due to the potential of drug resistance and rapid reinfection after treatment, better techniques are necessary for treating the disease. Recently, the peptide sequence YSGLQDSSLRLR was discovered using phage-display techniques (with M13 phage). The biopanning process was carried out with the tegument (outer body covering) of live Schistosoma japonicum schistosomula being the target. Furthermore, both the peptide alone and the peptide conjugated to Rhodamine B were shown to bind and exhibit a potent schistosomicidal effect in vitro. It appears that the peptide negatively effects growth, development, and fecundity of S. japonicum in vivo, but the mechanism of this action is not clear. The system could be further improved by conjugation with probes, drugs, or immunological mediators to provide better diagnostic imaging or longer circulation times of the peptides.57

6.4. Cutaneous Leishmaniasis

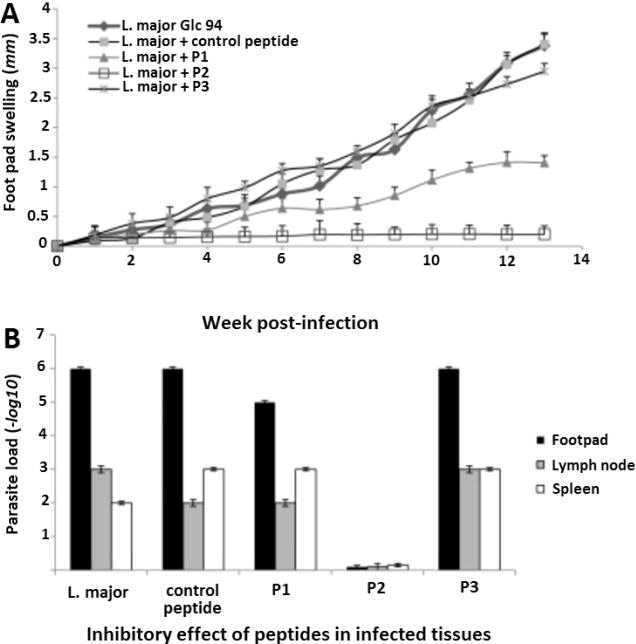

Cutaneous leishmaniasis is caused by parasitic intracellular protozoan pathogens of the genus Leishmania. These Leishmania parasites are responsible for 2 million new infections per year.51 There are no vaccines and limited chemotherapy options for cutaneous leishmaniasis. The very limited drug treatments available are highly toxic, requiring hospitalization.166 In addition, parasites develop drug resistance. With an increasing incidence of therapeutic failures and drug resistance, there is a dire need for new treatments.166 Recently, peptides developed through phage-display technology using a hexapeptide library (M13 phage pIII protein fusion) were found to be binding peptides for metacyclic promastigotes originating from a highly infectious strain of Leishmania major. The developed peptides were assessed in vitro on human monocytes infected with the disease as well as in vivo using a mouse model. The characteristic development of cutaneous lesions was shown to be protected against at a rate of 81.94% by utilizing the peptide MAAKYN in parasite-infected BALB/c mice. The peptide was shown to bind a major surface protease, gp63 (necessary for infection), and inhibit the growth kinetics of Leishmania major. The treatment effects of the peptide are shown in Figure 9. Taken together, this peptide shows great therapeutic promise in the treatment of Leishmania major.51

Figure 9.

Inhibitory effect of selected peptides in infected tissues. (A) Inoculation of BALB/c mice with several virus library derived L. major inhibitory peptide candidates. L. major Glc 94 metacyclic promastigotes (1.0 × 106) were preincubated with 100 μM of peptides P1 (MSKPKQ), P2 (MAAKYN), P3 (MAHYSG), or control peptide, or with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Next, 5 mice per group were inoculated with these preincubated mixtures. The sizes of lesions were monitored with a Vernier caliper. Lesion sizes were calculated by subtracting the size of the contralateral-uninfected footpad. Swellings were monitored over a 13-week observation period every week. The results shown are the mean lesion size of 5 mice per group in millimeters. (B) Parasite burden in infected footpads. The burden was determined after draining the lymph nodes and spleens of mice by a limiting-dilution assay at week 13 postinfection. Results shown are the means ± the standard deviations of log10 dilutions at the three anatomical sites. These results include triplicates for each group with 5 individuals in a group.51 Adapted with permission from ref51. Copyright 2016 Elsevier.

7. YEAST/FUNGAL INFECTION DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENT

7.1. Candida albicans

Peptides have now become a powerful tool for combating yeast/fungal infections.167 Candida albicans is a diploid fungus capable of growing as both yeast and filamentous cells.168 It is a human pathogen growing in the gastrointestinal and genitourinary tracts. Delayed treatments of Candida albicans lead to increased mortality rates.59,169 Established detection techniques can take up to 3 weeks to complete and lack reliability, resulting in an unnecessary treatment with toxic antifungals.58 Recently, phage-display technology (using M13 phages) was used to develop peptides with a high degree of specificity toward the different morphological forms of Candida albicans. For example, the peptide ELMAVPVPLPPA is one of the many peptides that could be used for detecting this pathogen in an ELISA test. Coupled with an ELISA format, the use of these peptides allows for the specific and rapid detection of Candida albicans so that patients can get the appropriate drug therapy faster.58

Additionally, building off of previous work (by Ghadjari et al.),60 our group developed an ultrasensitive, rapid detection virus-based ELISA system for detecting antibody biomarkers that indicate an infection with Candida albicans.59 The viruses double-displayed peptides with targeting specificity toward magnetic nanoparticles and the Candida albicans disease biomarker antibody, antisecreted aspartyl proteinase 2 IgG. The previous work by Ghadjari et al. involved the discovery of the described antibody detecting peptide, VKYTS, by using phage-display library.60 The second, magnetic nanoparticle-targeting sequence, PTYSLVPRLATQPFK, was developed by biopanning with an f88-15mer library using fd phage.59 Together, by double-displaying these peptides on fd phages, the antibody-targeting peptide will bind to the disease biomarker antibody and the magnetic nanoparticle peptide will bind to the nanoparticles. By applying a magnet, the biomarker detection in sera can be greatly enriched by concentrating the biomarkers. This allows for an average detection time of just 6 h compared to the previous gold standard of about 1 week. The detection limit for the new technique (1.1 pg/mL) is nearly 2 orders of magnitude lower than previously established antigen-based techniques.59

7.2. Paracoccidioidomycosis

Paracoccidioidomycosis is a disease caused by the Paracoccidioides brasiliensis fungus endemic in Latin America.170 Recently, a CX7C phage library was utilized to create peptides targeting P. brasiliensis. Amazingly, the peptide CGSYGFNAC (derived from biopanning) was capable of targeting and killing only the virulent fungi. Furthermore, mice infected with P. brasiliensis had a highly significant reduction in lung colony-forming units upon treatment with the peptide. This was a result of the peptide binding to the fungus and preventing implantation of the fungus in the lungs (the primary site of infection for this fungus) and also inhibiting deployment of the fungus. This demonstrated the great potential of using this peptide for the treatment of paracoccidioidomycosis.61

8. DISCOVERY AND APPLICATIONS OF HUMAN CELL/TISSUE TARGETING PEPTIDES

8.1. Virus-Derived Peptides for Drug/Gene Delivery to Human Cells/Tissues

The main barrier for targeted delivery is a poor permeability of the cellular plasma membrane to a drug or gene. Recently, the potential of cell-targeting peptides for targeted delivery is highlighted due to their strong binding affinity and high recognition specificity.171 In addition, their chemical stability and ease of conjugation allow them to be chemically coupled to a lot of therapeutics, including small-molecule chemotherapeutics, liposomes, and proteins. It is also worth mentioning that peptides discovered from one system such as phage display can be incorporated genetically into other systems for applications such as genetic imaging.172 Table 3 summarizes some important human cell-targeting peptides derived from virus libraries and their typical applications.

8.1.1. Virus-Derived Peptides for Treating Cancer by Drug and Gene Delivery

Perhaps the most important aspect of cancer treatment is early detection.88 Ovarian cancer presents particular diagnosis problems due to the absence of reliable biomarkers. Ovarian cancer is also the most common cause of mortality among gynecological malignancies.85 To overcome this issue, Wang et al. have developed an HO-8910 ovarian cancer cell targeting peptide, NPMIRRQ, through biopanning.85 The peptide, derived from an M13 phage Ph.D.-7 library, demonstrated its ability to selectively bind ovarian cancer cells and not cervical cancer by immunofluorescence and immunohistochemical assays. The discovery of this peptide may have great potential in the future for diagnosing ovarian cancer.

Additionally, Zhou et al. have developed another HO-8910 ovarian cancer cell targeting peptide.88 The peptide, SWQIGGN, was selected from a Ph.D.-C7C phage library. The peptide demonstrated an ability to control ovarian cancer cell migration, viability, adhesion capacity, invasion, and tumor growth in vivo. This peptide is in the process of being evaluated for clinical efficacy.88

Zhou et al.173 have also conjugated two lung cancer cell-targeting peptides, TP H1299.1 and TP H2009.1, which were isolated from a 20-mer peptide library,174 to the anticancer drug Doxorubicin, which is widely used in clinics.175 The peptide sequence for TP H1299.1 is VSQTMRQTAVPLLWFWTGSL. The sequence for TP H2009.1 is RGDLATLRQLAQEDGVVGVR. The tetrameric peptide–doxorubicin conjugates could specifically deliver the drug and inhibit cell growth in target cells but not in nontarget control cells. In addition, Du et al.78 exploited the potential of cell-targeting peptides for drug delivery in vivo. They isolated the A54 peptide (AGKGTPSLETTP) by in vivo phage display for hepatocarcinoma and also conjugated it to Doxorubicin for in vivo targeted therapy. The results in the A54-doxorubicin group showed a reduction in tumor size and prolongation of long-term survival compared to the control group. This indicated the effectiveness of the cell-targeting peptide for in vivo drug delivery.

Photodynamic therapy is another form of cancer treatment using light and photoactive compounds (photosensitizers) to kill cells. These photosensitizers produce singlet oxygen to induce cell death under light irradiation. As with many cancer therapies, the difficulty associated with treatment is precision targeting. Recently, a system utilizing the attachment of a photosensitizer, pyropheophorbide-a (PPa) conjugated to an SKBR-3 breast cancer targeting peptide (displayed on the side wall of fd phage) was developed for use in photodynamic therapy.176 The fd phage used overcomes the precision-targeting issue by displaying a cancer-targeting peptide on its side wall constituted by pVIII major coat protein. The photosensitizer is then also conjugated to the N-terminal end of the breast cancer targeting peptides to create a precision targeting delivery system. The novel phage-enabled photosensitizers were able to selectively target and kill SKBR3 tumor cells in vitro. This system clearly demonstrates the power of phage-display technology in cancer treatment.

Acute myeloid leukemia is another deadly disease for which <40% of patients under 60 years of age can be cured.84,177 While chemotherapy remains an option, gene therapy may be a more elegant solution. However, lack of specificity of viral and nonviral gene-therapy vectors to the cancerous cells is a major problem. To circumvent this issue, one group used an AAV2 display library to develop a peptide, NQVGSWS, that specifically targets acute myeloid leukemia cells. As AAV2 itself is already very useful for gene therapy, they were able to use the same virus with the discovered peptide as a targeted gene-therapy disease treatment for acute myeloid leukemia. The resulting vectors were loaded with a suicide gene and shown to selectively kill Kasumi-1 acute myeloid leukemia cells while not killing the control cells (CD34+ primary hematopoietic progenitor and peripheral blood mononuclear cells). Therefore, this technique may be a very promising alternative to existing strategies.84

Esophageal cancer is another common form of cancer.178 Esophageal cancer is particularly challenging to identify early due to its lack of early clinical symptoms. This cancer is typically only diagnosed at an advanced stage and requires surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy. To improve upon diagnosis, two novel peptides, RALAHPRDHPDL and ATCSMLLSRNEA, were discovered through biopanning with a Ph.D.-12 phage-display peptide library.73 The peptides were evaluated and were shown to be a possible tool for early detection by an ELISA, immunofluorescence assay, and immunohistochemistry assay.73 In this ELISA, Eca109 cells and normal esophageal cells were cultured on 96-well plates overnight. Selected phages could then be incubated in the wells for 1 h at 37 °C. After washing away unbound phages, an anti-M13 monoclonal antibody was used along with a goat antimouse secondary antibody conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (HRP) in the presence of its 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) substrate to detect phages at an absorbance of 490 nm. In this way, the phages could be used as a selective tool for detecting the Eca109 cells preferentially over normal esophageal cells.

8.1.2. Virus-Derived Peptides for Gene Delivery/Manipulation of Stem Cells

Human pluripotent stem (hPS) cells are valuable for tissue engineering applications. Their ability to self-renew and differentiate into any cell type makes them invaluable for tissue-engineering applications. However, hPS cells must meet stringent Food and Drug Administration (FDA) requirements in terms of efficacy and safety before they can be used. Inappropriate stem cell types capable of forming tumors can contaminate pluripotent stem cells, presenting a major challenge for therapies involving the transplant of cells into patients. For this reason, Bignone et al. developed peptides through phage display for the identification, isolation, and expansion of desired pluripotent stem cells from a mix of normal and diseased donor-derived hPS cell lines. The selected embryonic progenitor cell-binding peptides, EWLFEFPTPVDA and DWIATWPDAVRS, were shown to preferentially bind to embryonic progenitor cells compared to RGD and biotin peptide controls in an immunofluorescence assay.92

Neural stem/progenitor cells provide a continuous source of new neurons in a healthy adult brain. These cells are particularly useful for repairing brain damage or treating diseases such as idiopathic Parkinson’s disease. However, their ability to compensate for lost cells in damaged regions can be remediated by stimulation, which directs survival or differentiation. Preclinical studies of a peptide, SNQLPQQ, developed using a Ph.D.-7 phage-display library and later expressed on AAV for gene delivery to neural stem/progenitor cells, have shown promise in this area. However, the peptide developed has only been tested in mice so there is a need for a similar strategy in humans.179

8.1.3. Virus-Derived Vasculature Peptides

There is a great deal of diversity among all the receptors in human blood vessels. In light of this diversity, Arap et al. have made great progress by undergoing the first in vivo peptide library screening of a human patient’s vasculature system.53 In this clinical trial, >47 160 motifs were surveyed and found to localize to specific organs nonrandomly using a CX7C random phage-display peptide library after 15 min of circulation in the patient’s vasculature system. Among these, there were several candidates for motifs that bind to bone marrow, fat, skin, muscle, and prostate tissues, as can be found in Table 4. This highly influential study was an important step for virus-derived peptide targeting. With the new targeting motifs discovered, a great deal more is now known about targeting organs and tissues of the human vasculature system.

Strong, sustained gene expression in a specific tissue after a simple injection of a vector is a major challenge. The pulmonary vasculature is a highly relevant tissue target for gene therapy in need of a tissue-targeting gene-delivery technique. Recently, an X7 AAV2 library was utilized for screening peptides that efficiently target and deliver genes to the pulmonary vasculature after intravenous administration. The peptide, ESGHGYF, was selected in vivo using FVB/N mice. After 48 h, the organs of interest were removed and tissue DNA was extracted. Oligonucleotides contained in AAV library particles, which were found to be enriched in the tissue of interest, were then amplified by PCR and used to produce secondary libraries. These secondary libraries were then used for further rounds of selection. Analysis by a luciferase reporter gene expression assay in vivo demonstrated the tissue homing ability of the gene therapy.105 It should be noted that so far this peptide has only reached the preclinical stage, but with more work, strategies such as this will soon develop into the clinical trials stage.

8.1.4. Central Nervous System Virus-Derived Peptides

Central nervous system treatments require a high level of specificity due to the potentially complicated side-effects of such treatments. A peptide, CDCRGDCFC, discovered through phage display is capable of homing to multiple tumor types including carcinoma, sarcoma, and melanoma.34 More recently, phase I clinical trials using this virus-derived peptide were carried out to treat recurrent malignant gliomas in the brain.41 The purpose of the study was to determine the highest possible dosage of the drug, DNX-2401 (using the targeting sequence CDCRGDCFC) for use in tumor treatment. Additionally, DNX-2401 has demonstrated great potential in treating recurrent glioblastoma. For example, one clinical trial on humans showed that a patient has now survived >30 months after treatment with an absence of progression and no signs of needing further treatment. An additional two patients are now still alive after 23 months, but the study is still ongoing.180

Incontinentia pigmenti is the result of a rare X-linked dominant genetic defect.181 The disease is lethal in males. The disease primarily affects the ectodermal tissues such as the central nervous system, skin, teeth, and eyes. It also causes delayed development, paralysis, intellectual disability, muscle spasms, and seizures. Vectors utilizing AAV can greatly improve accessibility to the central nervous system for gene-therapy applications. However, there is a lack of specificity to brain endothelial cells for these vectors. Recently, AAV has been used to develop an efficient brain-homing peptide with a high degree of specificity for this target tissue and endothelial cells.107 The peptide, NRGTEWD, was developed through biopanning utilizing an AAV library. The mutant AAV displaying the targeting peptide was shown to demonstrate efficient, target-specific, long-lasting transgene expression in endothelial cell tissues associated with the blood–brain barrier. The AAV was administered by an intravenous injection, making it clinically easy to administer. As a proof of concept, preclinical trials were carried out to treat mice suffering from the genetic disorder incontinentia pigmenti. Incontinentia pigmenti is considered rare.182 It is an X-linked (caused by a mutation on the X chromosome) genodermatosis, which usually causes anomalies in the skin, appendages, and other organs.182 The gene therapy was shown to ameliorate the severe cerebrovascular pathology associated with incontinentia pigmenti. Not only does this provide a valuable treatment for incontinentia pigmenti, it also provides a proof of concept for a broader range of treatments for neurovascular diseases.183

Alternative central nervous system peptides have also been discovered utilizing an AAV library. For example, the peptide VDFAVNTEGVYSEPRPIGTRYLTRNL has been discovered utilizing an AAV library constructed as a hybrid of AAV 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, 9, rh8, rh10, rh39, and AAVrh43 by shuffling the DNA of their capsid genes.108 The peptide was selected through in vivo biopanning on mice. The peptide (displayed on AAV) was then evaluated for targeted gene-therapy applications using both mice and cat models. The extent of the efficiency of the gene-therapy method was evaluated by the expression of green fluorescent protein in the target tissues. The systemic injection of this new gene-therapy vector was found to result in widespread gene transfection throughout the central nervous system with the transduction of multiple neuronal subpopulations. In addition, the new gene-therapy vector was also shown to have a high efficiency for gene therapy in muscle, brain, spinal cord, lung, and pancreas tissues.108

8.2. Virus-Derived Peptides for Biomedical Imaging of Human Cells

Biomedical molecular imaging is an essential tool for the development of disease diagnostics.95 Recently, much progress has been made in targeted molecular imaging of diseases,184–186 which requires a molecular probe with a high affinity and selectivity. According to the fundamental advantages of peptides as discussed in the Introduction, cell- and tissue-targeting peptides have been widely used as an attractive probe in molecular-imaging applications.

8.2.1. Virus-Derived Stem Cell Imaging Peptides

With all the applications of stem cell therapies, it is also necessary to be able to image stem cells. Recently, Bignone et al.94 discovered three cell-targeting peptides: W10-R2-11, W10-R2-21, and W10-R3-18, for the human embryonic progenitor cell line W10. The most promising peptide sequence was DWLWSFAPNVDT, which was called W10-R3-18. The peptides were discovered through biopanning with a Ph.D.-12 phage library (M13 phage). Each cell-targeting peptide was modified with quantum dots (Qdot) to form a peptide–Qdot complex, which was used to label cells for both quantitative analysis and flow cytometry-based cell separations. The percentage of peptide–Qdot complex-labeled W10 cells data was in accordance with qualitative data observed by fluorescence microscopy. Another example of Qdot-conjugated cell-targeting peptides for targeted imaging is the APW peptide (full peptide sequence from biopanning was APWHLSSQYSRT) for primate embryonic stem cells.90 Confocal laser microscopy results indicated specific targeting of embryonic stem cells through peptide-conjugated Qdot for the first time.

8.2.2. Virus-Derived Cancer Cell Imaging Peptides

Cancer cell imaging is of vital importance for better understanding cancer as well as for providing an early diagnosis. The easiest strategy for cell-targeting peptide-based molecular imaging is to directly synthesize a fluorophore-labeled peptide. Zhang et al.76 developed a CP15 peptide (with a sequence of VHLGYAT), derived from a Ph.D.-7 phage library, for colon cancer cells. The FITC-labeled CP15 peptides were used to image target cells. The fluorescence microscopy data demonstrated CP15 peptide was the most effective peptide in targeting the colon cancer cell lines SW480 and HT29. Kelly et al. identified another colon carcinoma HT29 cell-targeting peptide called RPMrel (having the sequence CPIEDRPMC) from a Ph.D.-CX7C phage library.187 The FITC-conjugated RPMrel peptide only bound to HT29 colon carcinoma cells and colon tumor tissues, not to normal colon and noncolon tissues. Moreover, the conjugate of the RPMrel peptide and mitochondrial toxin showed a cancer-killing ability, demonstrating the usage of the RPMrel peptide in drug delivery.

Radiolabeling of cell-targeting peptides provides an efficient route for in vivo imaging using several techniques. These techniques include positron emission tomography (PET) as well as single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT).188 The OSP-1 peptide (ASGALSPSRLDT) is a 143B osteosarcoma tumor cell targeting peptide derived from a Ph.D.-12 phage library.189 The OSP-1 peptide was first coupled to Cy5.5 fluorescent dye to determine the binding affinity of OSP-1 in vitro and then radiolabeled by 18F for in vivo microPET imaging. Results showed OSP-1 peptide had a high affinity and specificity to osteosarcoma cells both in vitro and in vivo (∼2.5% ID/g), suggesting its potential for osteosarcoma diagnosis and treatment.

8.3. Virus-Derived Peptides for Biomedical Imaging/Treatment of Human Tissues

Apart from the cell-targeting peptides selected from in vitro phage display, some researchers used in vivo phage display to select tissue-targeting peptides. In addition, some cell-targeting peptides can also bind to their corresponding tissues. Several researchers have already applied these peptides for molecular imaging.

8.3.1. Tumor Tissue Imaging/Treatment

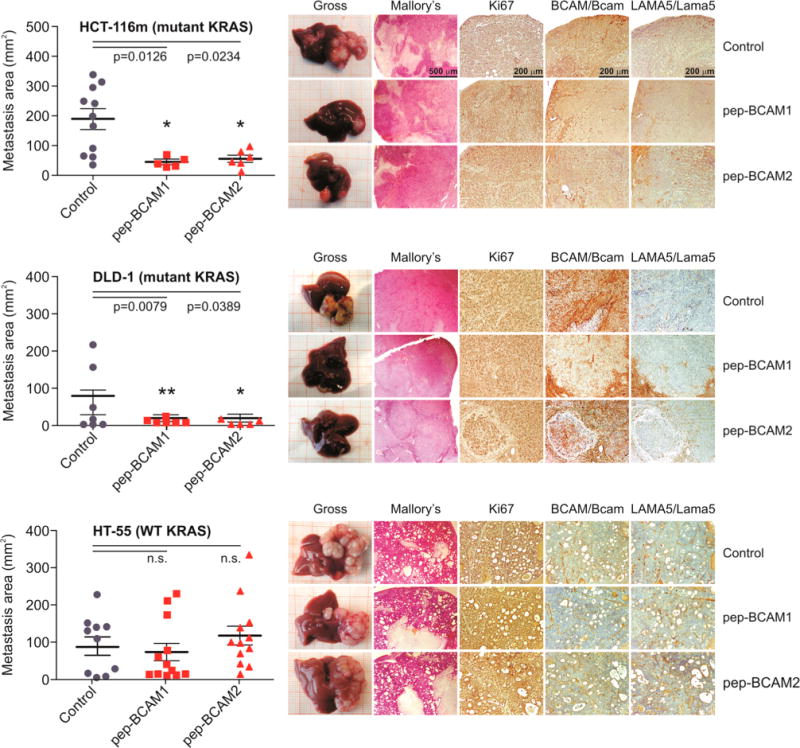

Current treatments for colorectal cancer in a metastatic setting are unsatisfactory.190 Current epidermal growth factor (EGF) receptor targeted therapies are an established treatment method, but 85–90% of patients do not respond to this therapy.72 It is known that mutations in EGF receptor downstream effectors such as KRAS (an oncogene that when mutated can cause normal cells to become cancerous) can cause a constitutive activation of the signaling pathway. This constitutive activation can allow for bypassing of the therapeutic block of the EGF receptor. Direct targeting attempts at KRAS by farnesyl transferase inhibitors have thus far failed.72 Therefore, a better direct targeting method is needed that could lead to a better treatment for colorectal cancer. Bartolini et al. have made use of ex vivo/in vitro phage-display screens (Ph.D.-7 phage-display peptide library kit) to potentially solve this issue and show that basal cell adhesion molecule (BCAM) and laminin subunit alpha 5 (LAMA5) are molecular targets within human tumor cells that, when inhibited, cause impaired adhesion of KRAS mutant colorectal cancer cells to endothelial cells.72 The expression of BCAM and LAMA5 was evaluated in preclinical human hepatic metastasis models (in mice having an intrahepatic implant of human colorectal cancer cell lines) as well as in 71 human patients. Two BCAM-mimetic peptides (ASGLLSLTSTLY and SSSLTLKVTSALSRDG) discovered from biopanning were chosen to be further evaluated and demonstrated antimetastatic efficacy. The two BCAM-mimetic peptides demonstrated efficacy against the hepatic colonization of human KRAS mutant colorectal cancer cells by inhibiting interactions with BCAM and LAMA5. This inhibition resulted in the abrogated adhesion of colorectal cancer cells to endothelial cells. The results are demonstrated in Figure 10.

Figure 10.