Abstract

The appropriate negative margin width for women undergoing breast-conserving surgery for both ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) and invasive carcinoma is controversial. Here we review the available data on margin status for invasive breast cancer and DCIS, and highlight the similarities and differences in tumor biology and standard treatments which impact the local recurrence risk and, therefore, the optimal surgical margin. Consensus guidelines support a negative margin defined as “no ink on tumor” for invasive carcinoma treated with breast-conserving therapy. Given differences in the growth pattern and utilization of systemic therapy, a margin of 2mm has been found to minimize the local recurrence risk for women with DCIS undergoing lumpectomy and radiation therapy. Wider negative margins do not improve local control for DCIS or invasive carcinoma when treated with lumpectomy and radiation therapy. Re-excision for negative margins should be individualized, and the routine practice of performing additional surgery to obtain a wider negative margin is not supported by the literature.

Keywords: breast-conserving therapy, local recurrence, negative margins, margins, breast cancer

INTRODUCTION

There has been considerable controversy regarding the optimal negative margin width to minimize local recurrence (LR) in patients undergoing breast-conserving therapy (BCT) for both invasive and intraductal carcinoma. The only defined microscopic margin width in the prospective randomized trials which established the safety of BCT in invasive carcinoma was no ink on tumor, the margin definition in the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project (NSABP) B06 study.1 Other studies widely perceived as requiring larger negative margins2, 3 defined only gross margin widths and do not contribute to our understanding of the impact of margin width on LR since the actual margin widths are unknown. In the 4 original randomized trials of ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) treated with and without radiotherapy, no ink on tumor was the margin definition used in 3,4–6 while the fourth study did not require negative margins.7 Recently, several factors have led to a re-examination of the issue of margins in BCT. These included the lack of consensus regarding margin width, resulting in high rates of re-excision,8, 9 the recognition that margin measurement is an inexact science, and changes in our understanding of the biology underlying LR.

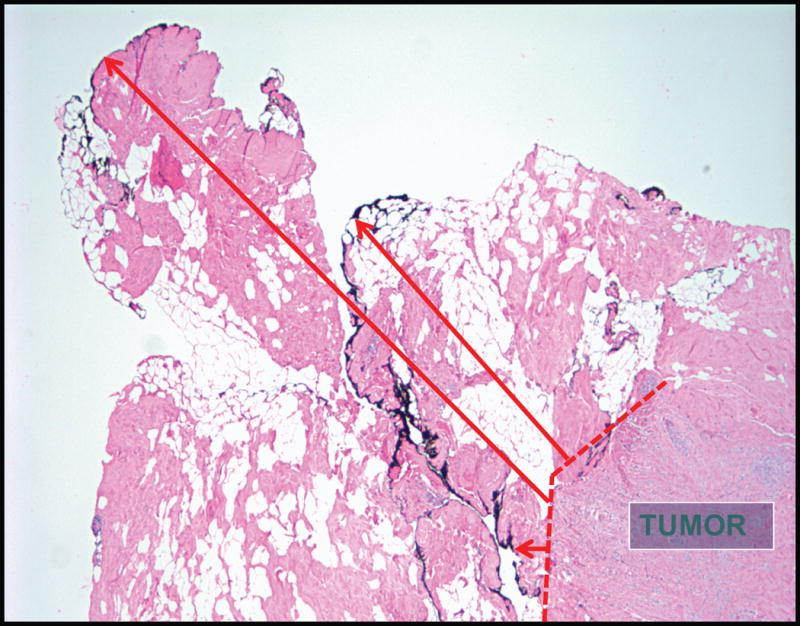

Approximately 25% of patients with invasive carcinoma and one-third of those with DCIS undergo re-excision,9, 10 with about half of the re-excisions done in patients with negative margins (defined as no ink on tumor)—apparently in the belief that a larger negative margin improves patient outcomes. The negative margin width reported by the pathologist is dependent on multiple factors, including the number of sections examined, the technique of margin assessment (perpendicular, shaved, cavity margins), what is defined as the margin when ink tracks through the irregular fatty surface overlying the tumor (Figure 1), and the use of specimen compression devices for radiography. In a study comparing measurement of the anterior-posterior diameter of breast specimens in the operating room and the pathology lab, 46% of the specimen height was lost by the time of measurement in the pathology lab, and this increased with the use of specimen compression devices.11 It has been estimated that 3000 sections would be required to completely examine the margin surfaces of a spherical lumpectomy specimen.12 This, coupled with the fact that a negative margin does not guarantee the absence of residual tumor in the breast,13 suggests that a negative margin is best regarded as one which indicates that the residual tumor burden in the breast is low enough that it is likely to be controlled with radiotherapy.

Figure 1.

Ink used to define the margin surface is seen at various distances from the tumor edge due to the irregular nature of the specimen surface and ink tracking through the breast fat, making reproducible measurement of margin width challenging (Photomicrograph courtesy of Stuart Schnitt, MD).

Changes in our understanding of breast cancer biology and the widespread use of adjuvant systemic therapy for early-stage breast cancers have also influenced attitudes about margins. For many years, tumor burden was thought to be the primary determinant of LR, and the belief that large negative margins improved outcome was a logical extension of this view of biology. It is now clear that the rate of LR varies with hormone receptor (HR) and HER2 status, being lowest among patients with HR+, HER2− tumors, and highest among those with triple negative tumors, regardless of whether treatment is with BCT or mastectomy.14 Among those with HR+, HER2− tumors, the risk of LR also varies significantly with the 21-gene recurrence score.15 Variation in the risk of LR is observed even among the smallest cancers (microinvasive, T1a,b),16 indicating that this is a fundamental tumor characteristic and not one which is acquired over time. Systemic therapy, used in the majority of patients with invasive breast cancer, also significantly impacts the risk of LR. Five years of adjuvant tamoxifen reduces the risk of LR by approximately 50%,17, 18 and newer endocrine therapies, such as the use of aromatase inhibitors and more prolonged treatment duration, provide further risk reductions.18 Conventional cytotoxic chemotherapy in women <50 years of age reduces the relative risk of LR to 0.63 compared to no treatment, and the use of trastuzumab provides a further relative risk reduction of 0.47.18 The practical impact of this is illustrated in 2 retrospective studies of LR outcomes in HER2+ patients.19, 20 In those undergoing BCT, the 3-year rate of LR was 7% prior to the use of adjuvant trastuzumab and decreased to 1% (p=0.01) in the period immediately after adoption of trastuzumab.19 A similar decrease in 5-year LR rates after mastectomy was seen pre-and post trastuzumab (6.6% vs 1.5%, p=0.04).20 Between 1990 and 2011, LR decreased from 30% to 15% of all first recurrences in a study of 86,598 women treated in phase 3 drug trials.21 These findings, coupled with the demonstration that microscopic disease left behind in the axilla is controlled with systemic therapy,22, 23 opened the door to a re-examination of margin width in patients undergoing BCT.

Margin Width and LR Risk in Invasive Cancer

A positive margin, defined as ink on tumor, is associated with a significant increase in LR risk and warrants consideration for additional surgery.24 Houssami and colleagues performed a study-level meta-analysis which included 33 eligible studies and over 28,000 women with early-stage breast cancer. A positive margin was associated with increasing LR (OR for positive versus negative margins 2.44; 95% CI 1.97–3.03; p<0.001), even after controlling for the use of a radiation boost or adjuvant endocrine therapy. Importantly, there was no evidence of a decreased LR risk with increasing negative margin widths from 1mm to 2mm to 5mm (p=0.90).25 These data confirm that even with modern multimodality treatment, a negative margin reduces the risk of LR; however, increasing the size of a negative margin is not significantly associated with improvement in local control.

In 2014 the Society of Surgical Oncology (SSO) and the American Society for Radiation Oncology (ASTRO) convened a multidisciplinary panel to develop a consensus guideline on the appropriate margin width to minimize risk of LR in patients with invasive cancer treated with BCT and whole breast radiation therapy. Using data from the meta-analysis of Houssami et al25 as well as other published literature, the panel concluded that a negative margin of no ink on tumor optimizes local control and that the routine practice of obtaining a more widely negative margin than no ink on tumor is not indicated.26 This negative margin definition was endorsed by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN), the American Society of Clinical Oncology, the American Society of Breast Surgery, and the St. Gallen International Expert Consensus group.27 Of note, the guideline of no ink on tumor does not apply to patients receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy or those treated with partial breast irradiation.

The panel also addressed the need for wider negative margins within select high-risk subsets. Young age and triple negative cancers are both independent risk factors for LR, but the available evidence indicates that it is tumor biology, not the extent of surgical excision, that is associated with a worse outcome, as LR rates are similar among women in these high-risk groups treated with BCT or mastectomy.28 A single-institution series examining margin width and LR among women with triple negative breast cancer found no difference in 5-year LR rates between margins ≤2mm or >2mm (4.7% and 3.7%, respectively, p=0.11).29 Studies performed prior to the routine inking of margins suggested that an extensive intraductal component (EIC) was associated with an increased risk of LR30; however, more recent reports of patients with EIC positive tumors excised to negative margins find LR rates similar to those without an EIC.31, 32 An EIC is an indicator of the potential for a heavy residual burden of DCIS, and post-excision mammography and the extent of DCIS in proximity to the margin are important factors in considering the benefit of re-excision. While the consensus guideline states that margins more widely clear than no ink on tumor are not routinely indicated, it should not be interpreted as meaning that re-excision is never appropriate when a minimal negative margin has been obtained. The patient, tumor, and treatment variables influencing the risk of LR should be considered in determining the need for re-excision. The key point of the consensus statement is that routinely mandating negative margin widths greater than no ink on tumor is not supported by evidence.

The development of the consensus guideline appears to have resulted in a rapid reduction in the use of additional surgery after initial lumpectomy. In a single-institution study, re-excision rates fell from 21% to 15% (p=0.006) in the immediate 10-month window following guideline dissemination.33 In a population-based cohort survey of patients identified from the Georgia and Los Angeles County, California, Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) registries, and treated in the period immediately before and after guideline dissemination and publication (2013–2015), the initial lumpectomy rate (67%) was unchanged; however, additional surgery following initial lumpectomy, including both re-excision and conversion to mastectomy, decreased by 16% (p<.001) over this 2-year period. Overall, the final lumpectomy rate increased by 13%, accompanied by a decrease in both unilateral and bilateral mastectomy (p=0.002). The treating surgeons were surveyed on their attitudes regarding margin width, and 63% endorsed no ink on tumor as an adequate negative margin to avoid re-excision,34 a proportion much greater than the 11% accepting this definition a decade earlier.8 It is estimated that adoption of the margin guideline would save the healthcare system over $18 million annually, not including the time and costs saved by patients and families for missed work.35

Margins in Ductal Carcinoma In Situ

DCIS has a 10-year cause-specific mortality under 1% after BCT,36 but optimizing local control is important, as half of all LR events are invasive cancers37 with an associated increased risk of breast cancer-specific mortality.38 Although the risk of LR following BCT for DCIS is impacted by a number of factors, including young patient age, symptomatic presentation, extent of disease, and presence of necrosis, margin width and use of adjuvant therapy are modifiable risk factors.39–41 The 4 randomized controlled trials examining the benefit of radiation therapy (RT) after lumpectomy for women with DCIS4–7 were not designed to evaluate the association of margin width and LR, and provide minimal guidance on defining the optimal margin width for patients with DCIS, and surveys of surgeons and radiation oncologists report significant heterogeneity regarding what constitutes an acceptable margin width for DCIS treated with BCT, ranging from no ink on tumor to >1cm.8, 42–44 While these findings mirror the experience with invasive carcinoma, there are important differences between DCIS and invasive breast cancer, including the growth pattern of the lesion and the utilization of adjuvant therapy, that must be considered when determining the optimal surgical margin.

DCIS Growth Pattern

Multicentric DCIS is uncommon, but DCIS within one quadrant may be extensive, with 46% of lesions measuring >3cm in one study.13 Faverly and colleagues examined the growth pattern of DCIS and found that while 90% of poorly differentiated lesions grew continuously, 70% of well-differentiated lesions had a multifocal, skip pattern, with 82% of skip lesions measuring between 0mm to 5mm, and only 8% having skip lesions >10mm.45 These studies suggest that that a small negative margin may lie within a skip lesion and may be associated with a substantial residual tumor burden.

In addition to anatomic differences that may impact margin assessment, there are significant differences in utilization of adjuvant therapy between invasive and in situ carcinoma which impact LR. Approximately 55% to 70% of women with DCIS treated with lumpectomy receive adjuvant RT, and only 20% to 50% receive adjuvant endocrine therapy—numbers significantly lower than those seen for invasive carcinoma.36, 39, 46 For women treated with lumpectomy and RT, the optimal margin is that which leaves a subclinical volume of residual microscopic disease within the breast that is likely controlled by RT. For women treated with excision alone, the goal of surgery is to remove all microscopic disease to minimize LR risk, and, therefore, a wider margin may be appropriate.

Margin Width and LR Risk in DCIS Treated with Excision Alone

The proportion of women with DCIS treated by excision alone ranges from 17% to 44%,47 with 31% of those undergoing BCT and reported to SEER between 1988 and 2011 having excision alone.36 An early study by Silverstein et al suggested that a margin of 1 cm or greater negated the benefit of RT;48 however, these findings have not been replicated in subsequent studies.49–51 In a study of 1374 women undergoing excision alone, margin width was significantly associated with LR, with 10-year LR rates ranging from 41% with a positive margin to 16% with a >1cm margin (p=.00003). On multivariable analysis controlling for age, family history, presentation, number of excisions, use of adjuvant endocrine therapy, and year of surgery, incremental increases in margin width were associated with decreasing LR risk (p<.0001).39 In contrast, after 12 years of follow-up in the ECOG-ACRIN (Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group–American College of Radiology Imaging Network) E5194 trial, which included women with low to intermediate grade DCIS ≤2.5cm in size or high-grade DCIS ≤1cm in size treated with excision alone and a negative margin of at least 3mm, no significant relationship between margin widths of <5mm, 5–9mm, or 1cm or larger was observed.52 Table 1 reviews studies examining rates of LR for DCIS treated with excision alone, highlighting that there are cohorts of low-risk patients undergoing excision alone that have low local failure rates with a range of negative margin widths.48, 49, 51–55 The decision for re-excision or radiation therapy for DCIS is multi-factorial, with margin width being one factor that may impact the decision for further risk-reducing therapy. Patient age, size of DCIS, tumor grade, margin width, and patient comfort with recurrence risk are all taken into consideration when deciding whether to omit radiation therapy or return to the operating room, because, as seen in Table 1, there is no uniform negative margin width reported in the literature that is routinely associated with a low recurrence risk among women with DCIS treated with excision alone.

TABLE 1.

Local Recurrence Rates for DCIS Treated with Excision Alone by Margin Status

| Author | Minimum margin required/margin cohorts | Additional inclusion criteria | Patients with margins ≥ 10 mm | Median tumor size | Number of years for reported LR | LR rates |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Silverstein48 | < 1 mm 1–10 mm > 10 mm |

– | 93/256 (36%) |

19 mm 8 mm 9 mm |

8 year | 58% 20% 3% |

| Macdonald54 | 10 mm | – | 272/272 (100%) |

* | 12 year | 14% |

| Van Zee39 | ≤2mm >2–10mm >10mm |

– | 669/1374 (49%) |

Not reported | 10 year | 27% 23% 16% |

| Hughes53 | < 10 mm** ≥ 10 mm |

Low-intermediate grade, tumor size ≤ 2.5 cm | 274/565 (48%) |

6 mm | 5 year | 6% 7% |

| < 10 mm** ≥ 10 mm |

High grade, tumor size < 1 cm | 56/105 (53%) |

5 mm | 7 year | 15% 16% |

|

| Wehner51 | 2 mm | Tumor size ≤ 2 cm, age ≥ 50 years, non-high grade | 119/205 (58%) |

8 mm | 12 year | 8% |

| Wong49 | 10 mm | Low-intermediate grade, tumor size ≤ 2.5 cm | 143/143 (100%) |

8 mmˆ | 10 year | 16% |

| McCormick55 | 3 mm | Low-intermediate grade, tumor size < 2.5 cm | 48/298 (16%) |

5 mm | 7 year | 7% |

| Solin52 | 3 mm | Low-intermediate grade, tumor size ≤ 2.5 cm | 119/561 (21%) |

6 mm | 12 year | 14% |

| High grade, tumor size ≤ 1 cm | 25/104 (24%) |

7 mm | 25% |

Abbreviations: LR, local recurrence; DCIS, ductal carcinoma in situ; NA, not applicable

Tumor size reported as: 72%, ≥ 15 mm; 24%, 15–40 mm; 4% > 40 mm

minimum margin required in study: 3 mm

mammographic size of DCIS

Margin Width and LR Risk in DCIS Treated with Excision and RT

A study-level meta-analysis including 6353 women treated with BCT and RT was conducted to evaluate the impact of margin status on LR. Due to the heterogeneity of the data, both a Bayesian network analysis and a frequentist analysis were used to examine the data. Both analyses confirmed that the odds of LR are reduced by more than 50% with a negative compared to a positive margin (OR 0.45, 95% credible interval [CrI] 0.30–0.62). In the Bayesian analysis relative to a positive margin, significant reductions were seen for all negative margin widths (Table 2).56 When comparing a 2mm margin to a smaller negative margin, a non-significant trend toward a decrease in LR was observed (relative OR 0.72, 95% Crl 0.47–1.08). In the frequentist analysis, a 2mm margin was associated with a significant reduction in LR compared to a smaller negative margin (OR 0.51, 95% CI 0.31–0.85; p=0.01) (Table 2). Importantly, in both analyses, no additional benefit was seen for margins greater than 2mm.56 Subsequently, in 2015 an SSO-ASTRO-ASCO multidisciplinary consensus panel concluded that a 2mm margin minimizes the risk of LR compared with smaller negative margins, but that more widely clear margins do not further reduce the risk of LR.57 Two large, single-institution studies reported on their experience with DCIS treated with BCT, and both found that close margins (<2mm) were not inferior to wider negative margins among women treated with RT.39, 58

TABLE 2.

Estimated Margin Threshold Effects on Local Recurrence in DCIS Treated with Lumpectomy and Radiation Therapy from Meta-Analysis56

| Model | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequentist Model | Threshold distance for negative margins relative to > 0 or 1mm OR and 95% CI adjusted for follow-up |

||||

| > 0 or 1 mm | 2 mm | 3 or 5 mm | 10 mm | p-value | |

| Referent | 0.5 (0.31–0.85) | 0.4 (0.18–0.97) | 0.6 (0.33–1.08) | 0.046 | |

| Bayesian Model | Threshold distance for negative margins relative to positive Mean OR and 95% Crl adjusted for follow-up |

||||

| > 0 or 1 mm | 2 mm | 3 mm | 10 mm | ||

| 0.5 (0.32–0.61) | 0.3 (0.21–0.48) | 0.3 (0.12–0.76) | 0.3 (0.19–0.49) | ||

Abbreviations: OR, odds ratio; CrI, credible interval

Although the meta-analysis discussed above found that a margin of 2mm reduces LR compared to smaller negative margins, the findings of single-institution studies, the favorable long-term outcomes observed in NSABP trials using a margin definition of no ink on tumor, and the recognition that small differences in local control do not impact survival in DCIS led members of the SSO-ASTRO-ASCO DCIS margins consensus panel to emphasize that the decision to perform a re-excision for negative margins <2mm should be individualized based upon multiple factors, including volume of disease near a margin, results of a post-excision mammogram, cosmetic impact of re-excision, patient age, tumor size and grade, life expectancy, and patient tolerance of risk. In particular, it was emphasized that a negative margin <2mm is not by itself an indication for mastectomy.

DCIS and Invasive Cancer: Which Guideline to Use?

The invasive cancer margin guideline endorses no ink on tumor, while the DCIS guideline states that 2mm is an optimal margin. This raises the question of which guideline to apply in microinvasive carcinoma, or when DCIS occurs in association with invasive carcinoma and the DCIS component is in proximity to the margin. The margins consensus panel opted to draw the line for the DCIS guideline at microinvasive cancer, including this with DCIS because most of the lesion is comprised of DCIS, and because small retrospective studies suggest that the behavior of microinvasive carcinoma is more similar to DCIS than invasive cancer,59 and that the use of systemic therapy is more similar to that seen in DCIS. In contrast, invasive cancer with associated DCIS, whether an EIC or lesser amounts, should be managed according to the invasive guideline. In these cases, the biology of the invasive cancer is the primary determinant of outcome and the majority of patients will receive systemic therapy. Additionally, an EIC excised to clear margins does not increase LR,31, 32 although, as discussed previously, it is a potential marker for a heavier residual disease burden.

CONCLUSION

In the modern era of multimodality therapy for invasive and in situ breast carcinoma, margin status is one of a number of factors impacting LR risk, and tumor biology rather than an arbitrary anatomic margin cut-off is the major determinant of LR. For invasive breast cancer, the data support obtaining a negative margin, defined as ‘no ink on tumor’, and do not identify an additional benefit for more widely clear margins. In patients with DCIS receiving RT, a margin of 2mm minimizes LR, but larger margins do not provide added benefit. Adoption of these evidence-based margin guidelines will decrease the burden of surgery for patients and their families, and reduce health care costs.

Condensed abstract.

In today’s era of multimodality therapy for invasive and in situ breast carcinoma, margin status is one of a number of factors impacting local recurrence risk. Current data support a negative margin width of no ink of tumor to minimize local recurrence risk for invasive breast cancer and a margin of 2 mm for women with DCIS treated with lumpectomy and radiation therapy.

Acknowledgments

FUNDING SUPPORT

The preparation of this manuscript was supported by NIH/NCI Cancer Center Support Grant No. P30 CA008748 to Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center.

Footnotes

Anatomic site: Breast

Conflict of interest information: The authors have no conflict of interest disclosures to report, and this manuscript is not under consideration elsewhere.

Invitation indication: Invited

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Melissa L. Pilewskie: Conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, investigation, data curation, writing–original draft, and writing–review and editing.

Monica Morrow: Conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, investigation, data curation, writing–original draft, and writing–review and editing.

References

- 1.Fisher B, Anderson S, Redmond CK, Wolmark N, Wickerham DL, Cronin WM. Reanalysis and results after 12 years of follow-up in a randomized clinical trial comparing total mastectomy with lumpectomy with or without irradiation in the treatment of breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1456–1461. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199511303332203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Veronesi U, Cascinelli N, Mariani L, et al. Twenty-year follow-up of a randomized study comparing breast-conserving surgery with radical mastectomy for early breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1227–1232. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van Dongen JA, Bartelink H, Fentiman IS, et al. Factors influencing local relapse and survival and results of salvage treatment after breast-conserving therapy in operable breast cancer: EORTC trial 10801, breast conservation compared with mastectomy in TNM stage I and II breast cancer. Eur J Cancer. 1992;28A:801–805. doi: 10.1016/0959-8049(92)90118-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fisher B, Dignam J, Wolmark N, et al. Lumpectomy and radiation therapy for the treatment of intraductal breast cancer: findings from National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project B-17. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:441–452. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.2.441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Houghton J, George WD, Cuzick J, et al. Radiotherapy and tamoxifen in women with completely excised ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast in the UK, Australia, and New Zealand: randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2003;362:95–102. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(03)13859-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Julien JP, Bijker N, Fentiman IS, et al. Radiotherapy in breast-conserving treatment for ductal carcinoma in situ: first results of the EORTC randomised phase III trial 10853. EORTC Breast Cancer Cooperative Group and EORTC Radiotherapy Group. Lancet. 2000;355:528–533. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(99)06341-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Emdin SO, Granstrand B, Ringberg A, et al. SweDCIS: Radiotherapy after sector resection for ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast. Results of a randomised trial in a population offered mammography screening. Acta Oncol. 2006;45:536–543. doi: 10.1080/02841860600681569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Azu M, Abrahamse P, Katz SJ, Jagsi R, Morrow M. What is an adequate margin for breast-conserving surgery? Surgeon attitudes and correlates. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:558–563. doi: 10.1245/s10434-009-0765-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morrow M, Jagsi R, Alderman AK, et al. Surgeon recommendations and receipt of mastectomy for treatment of breast cancer. JAMA. 2009;302:1551–1556. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McCahill LE, Single RM, Aiello Bowles EJ, et al. Variability in reexcision following breast conservation surgery. JAMA. 2012;307:467–475. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Graham RA, Homer MJ, Katz J, Rothschild J, Safaii H, Supran S. The pancake phenomenon contributes to the inaccuracy of margin assessment in patients with breast cancer. Am J Surg. 2002;184:89–93. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(02)00902-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carter D. Margins of “lumpectomy” for breast cancer. Hum Pathol. 1986;17:330–332. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(86)80455-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holland R, Veling SH, Mravunac M, Hendriks JH. Histologic multifocality of Tis, T1–2 breast carcinomas. Implications for clinical trials of breast-conserving surgery. Cancer. 1985;56:979–990. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19850901)56:5<979::aid-cncr2820560502>3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lowery AJ, Kell MR, Glynn RW, Kerin MJ, Sweeney KJ. Locoregional recurrence after breast cancer surgery: a systematic review by receptor phenotype. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;133:831–841. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1891-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mamounas EP, Tang G, Fisher B, et al. Association between the 21-gene recurrence score assay and risk of locoregional recurrence in node-negative, estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer: results from NSABP B-14 and NSABP B-20. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:1677–1683. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.7610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cancello G, Maisonneuve P, Rotmensz N, et al. Prognosis in women with small (T1mic,T1a,T1b) node-negative operable breast cancer by immunohistochemically selected subtypes. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;127:713–720. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1465-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Clarke M, Collins R, Darby S, et al. Effects of radiotherapy and of differences in the extent of surgery for early breast cancer on local recurrence and 15-year survival: an overview of the randomised trials. Lancet. 2005;366:2087–2106. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67887-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mannino M, Yarnold JR. Local relapse rates are falling after breast conserving surgery and systemic therapy for early breast cancer: can radiotherapy ever be safely withheld? Radiother Oncol. 2009;90:14–22. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2008.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kiess AP, McArthur HL, Mahoney K, et al. Adjuvant trastuzumab reduces locoregional recurrence in women who receive breast-conservation therapy for lymph node-negative, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive breast cancer. Cancer. 2012;118:1982–1988. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lanning RM, Morrow M, Riaz N, et al. The Effect of Adjuvant Trastuzumab on Locoregional Recurrence of Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2-Positive Breast Cancer Treated with Mastectomy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22:2517–2525. doi: 10.1245/s10434-014-4321-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bouganim N, Tsvetkova E, Clemons M, Amir E. Evolution of sites of recurrence after early breast cancer over the last 20 years: implications for patient care and future research. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2013;139:603–606. doi: 10.1007/s10549-013-2561-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Giuliano AE, Hunt KK, Ballman KV, et al. Axillary dissection vs no axillary dissection in women with invasive breast cancer and sentinel node metastasis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2011;305:569–575. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Galimberti V, Cole BF, Zurrida S, et al. Axillary dissection versus no axillary dissection in patients with sentinel-node micrometastases (IBCSG 23-01): a phase 3 randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:297–305. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70035-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Houssami N, Macaskill P, Marinovich ML, et al. Meta-analysis of the impact of surgical margins on local recurrence in women with early-stage invasive breast cancer treated with breast-conserving therapy. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46:3219–3232. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.07.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Houssami N, Macaskill P, Marinovich ML, Morrow M. The association of surgical margins and local recurrence in women with early-stage invasive breast cancer treated with breast-conserving therapy: a meta-analysis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21:717–730. doi: 10.1245/s10434-014-3480-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moran MS, Schnitt SJ, Giuliano AE, et al. Society of Surgical Oncology-American Society for Radiation Oncology Consensus Guideline on Margins for Breast-Conserving Surgery With Whole-Breast Irradiation in Stages I and II Invasive Breast Cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:1507–1515. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.53.3935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Curigliano G, Burstein HJ, E PW, et al. De-escalating and escalating treatments for early-stage breast cancer: the St. Gallen International Expert Consensus Conference on the Primary Therapy of Early Breast Cancer 2017. Ann Oncol. 2017;28:1700–1712. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdx308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pilewskie M, King TA. Age and molecular subtypes: impact on surgical decisions. J Surg Oncol. 2014;110:8–14. doi: 10.1002/jso.23604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pilewskie M, Ho A, Orell E, et al. Effect of margin width on local recurrence in triple-negative breast cancer patients treated with breast-conserving therapy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21:1209–1214. doi: 10.1245/s10434-013-3416-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Harris JR. Breast-conserving therapy as a model for creating new knowledge in clinical oncology. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1996;35:641–648. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(96)00215-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bartelink H, Horiot JC, Poortmans P, et al. Recurrence rates after treatment of breast cancer with standard radiotherapy with or without additional radiation. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1378–1387. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa010874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Park CC, Mitsumori M, Nixon A, et al. Outcome at 8 years after breast-conserving surgery and radiation therapy for invasive breast cancer: influence of margin status and systemic therapy on local recurrence. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:1668–1675. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.8.1668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rosenberger LH, Mamtani A, Fuzesi S, et al. Early Adoption of the SSO-ASTRO Consensus Guidelines on Margins for Breast-Conserving Surgery with Whole-Breast Irradiation in Stage I and II Invasive Breast Cancer: Initial Experience from Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016;23:3239–3246. doi: 10.1245/s10434-016-5397-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pilewskie M, Morrow M. Axillary Nodal Management Following Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy: A Review. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3:549–555. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.4163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Abe SE, Hill JS, Han Y, et al. Margin re-excision and local recurrence in invasive breast cancer: A cost analysis using a decision tree model. J Surg Oncol. 2015;112:443–448. doi: 10.1002/jso.23990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Narod SA, Iqbal J, Giannakeas V, Sopik V, Sun P. Breast Cancer Mortality After a Diagnosis of Ductal Carcinoma In Situ. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1:888–896. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.2510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative G. Correa C, McGale P, et al. Overview of the randomized trials of radiotherapy in ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2010;2010:162–177. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgq039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wapnir IL, Dignam JJ, Fisher B, et al. Long-term outcomes of invasive ipsilateral breast tumor recurrences after lumpectomy in NSABP B-17 and B-24 randomized clinical trials for DCIS. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103:478–488. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djr027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Van Zee KJ, Subhedar P, Olcese C, Patil S, Morrow M. Relationship Between Margin Width and Recurrence of Ductal Carcinoma In Situ: Analysis of 2996 Women Treated With Breast-conserving Surgery for 30 Years. Ann Surg. 2015;262:623–631. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Donker M, Litiere S, Werutsky G, et al. Breast-conserving treatment with or without radiotherapy in ductal carcinoma In Situ: 15-year recurrence rates and outcome after a recurrence, from the EORTC 10853 randomized phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:4054–4059. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.49.5077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rodrigues N, Carter D, Dillon D, Parisot N, Choi DH, Haffty BG. Correlation of clinical and pathologic features with outcome in patients with ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast treated with breast-conserving surgery and radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2002;54:1331–1335. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(02)03747-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Taghian A, Mohiuddin M, Jagsi R, Goldberg S, Ceilley E, Powell S. Current perceptions regarding surgical margin status after breast-conserving therapy: results of a survey. Ann Surg. 2005;241:629–639. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000157272.04803.1b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Blair SL, Thompson K, Rococco J, Malcarne V, Beitsch PD, Ollila DW. Attaining negative margins in breast-conservation operations: is there a consensus among breast surgeons? J Am Coll Surg. 2009;209:608–613. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2009.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hassani A, Griffith C, Harvey J. Size does matter: High volume breast surgeons accept smaller excision margins for wide local excision–a national survey of the surgical management of wide local excision margins in UK breast cancer patients. Breast. 2013;22:718–722. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2012.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Faverly DR, Burgers L, Bult P, Holland R. Three dimensional imaging of mammary ductal carcinoma in situ: clinical implications. Semin Diagn Pathol. 1994;11:193–198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sagara Y, Freedman RA, Wong SM, et al. Trends in adjuvant therapies after breast-conserving surgery for hormone receptor-positive ductal carcinoma in situ: findings from the National Cancer Database, 2004–2013. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2017 doi: 10.1007/s10549-017-4436-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Smith GL, Smith BD, Haffty BG. Rationalization and regionalization of treatment for ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;65:1397–1403. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Silverstein MJ, Lagios MD, Groshen S, et al. The influence of margin width on local control of ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1455–1461. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199905133401902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wong JS, Chen YH, Gadd MA, et al. Eight-year update of a prospective study of wide excision alone for small low- or intermediate-grade ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2014;143:343–350. doi: 10.1007/s10549-013-2813-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Macdonald HR, Silverstein MJ, Lee LA, et al. Margin width as the sole determinant of local recurrence after breast conservation in patients with ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast. Am J Surg. 2006;192:420–422. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2006.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wehner P, Lagios MD, Silverstein MJ. DCIS treated with excision alone using the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20:3175–3179. doi: 10.1245/s10434-013-3176-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Solin LJ, Gray R, Hughes LL, et al. Surgical Excision Without Radiation for Ductal Carcinoma in Situ of the Breast: 12-Year Results From the ECOG-ACRIN E5194 Study. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:3938–3944. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.60.8588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hughes LL, Wang M, Page DL, et al. Local excision alone without irradiation for ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast: a trial of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:5319–5324. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.21.8560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.MacDonald HR, Silverstein MJ, Mabry H, et al. Local control in ductal carcinoma in situ treated by excision alone: incremental benefit of larger margins. Am J Surg. 2005;190:521–525. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2005.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.McCormick B, Winter K, Hudis C, et al. RTOG 9804: a prospective randomized trial for good-risk ductal carcinoma in situ comparing radiotherapy with observation. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:709–715. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.57.9029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Marinovich ML, Azizi L, Macaskill P, et al. The Association of Surgical Margins and Local Recurrence in Women with Ductal Carcinoma In Situ Treated with Breast-Conserving Therapy: A Meta-Analysis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016;23:3811–3821. doi: 10.1245/s10434-016-5446-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Morrow M, Van Zee KJ, Solin LJ, et al. Society of Surgical Oncology-American Society for Radiation Oncology-American Society of Clinical Oncology Consensus Guideline on Margins for Breast-Conserving Surgery With Whole-Breast Irradiation in Ductal Carcinoma In Situ. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:4040–4046. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.68.3573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kuerer HM, Smith BD, Chavez-MacGregor M, et al. DCIS Margins and Breast Conservation: MD Anderson Cancer Center Multidisciplinary Practice Guidelines and Outcomes. J Cancer. 2017;8:2653–2662. doi: 10.7150/jca.20871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Parikh RR, Haffty BG, Lannin D, Moran MS. Ductal carcinoma in situ with microinvasion: prognostic implications, long-term outcomes, and role of axillary evaluation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;82:7–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]