Abstract

Objective:

The purpose of this study is to measure provincial spending for mental health services in fiscal year (FY) 2013 and to compare these cost estimates to those of FY 2003.

Methods:

This study estimated the costs of publicly funded provincial mental health services in FY 2013 and compared them to the estimates for FY 2003 from a previously published report. Our data were obtained from publicly accessible databases. The cross-year cost comparisons for provincial mental health services were restricted to general and psychiatric hospital inpatients, clinical payments to physicians and psychologists, and prescribed psychotropic medications. Total public expenditures were inflation adjusted and expressed per capita and as a percentage of the total provincial health spending.

Results:

Total public spending for mental health and addiction programs/services was estimated to be $6.75 billion for FY 2013. The largest component of the expenditures was hospital inpatient services ($4.02 billion, 59.6%), followed by clinical payments to physicians or psychologists ($1.69 billion, 25%), and then publicly funded prescribed psychotherapeutic medications ($1.04 billion, 15.4%). Nationally, the portion of total public spending on health that was spent on mental health decreased from FY 2003 to FY 2013 from 5.4% to 4.9%.

Conclusion:

Our results reveal that mental health spending, as a proportion of public health care expenditures, decreased in the decade from FY 2003 to FY 2013. Due to large differences in how the provinces report community mental health services, we still lack a comprehensive picture of the mental health system.

Keywords: public expenditure, mental health services, hospital expenditures, drug costs, physician cost, psychiatrists

Abstract

Objectif:

Le but de cette étude est de mesurer les dépenses provinciales pour les services de santé mentale de l’exercice financier (EF) 2013, et de comparer ces estimations de coûts avec celles de l’EF 2003.

Méthodes:

Cette étude a estimé les coûts des services de santé mentale provinciaux financés par les fonds publics de l’EF 2013, et les a comparés avec les estimations de l’EF 2003 d’après un rapport publié précédemment. Nos données provenaient de bases de données accessibles au public. Les comparaisons de coûts entre années pour les services de santé mentale provinciaux se limitaient aux patients hospitalisés des hôpitaux généraux et psychiatriques, aux paiements cliniques versés aux médecins et aux psychologues, et aux médicaments psychotropes prescrits. Les dépenses publiques totales étaient ajustées en fonction de l’inflation et exprimées per capita, et en pourcentage des dépenses de santé provinciales totales.

Résultats:

Les dépenses publiques totales pour la santé mentale et les programmes/services de toxicomanie étaient estimées à 6,75 milliards de dollars pour l’EF 2013. La portion la plus importante des dépenses était les services aux patients hospitalisés (4,02 milliards de dollars, 59,6%), suivis des paiements cliniques versés aux médecins ou psychologues (1,69 milliard de dollars, 25%), puis des médicaments psychotropes prescrits financés par les fonds publics (1,04 milliard de dollars, 15,4%). À l’échelle nationale, la portion des dépenses publiques totales en santé qui a été allouée à la santé mentale a diminué de l’EF 2003 à l’EF 2013 de 5,4% à 4,9%.

Conclusion:

Nos résultats révèlent que les dépenses de santé mentale, à titre de proportion des dépenses de santé publiques, ont diminué durant la décennie de l’EF 2003 à l’EF 2013. En raison des grandes différences dans la façon dont les provinces rendent compte des services de santé mentale communautaire, il nous manque encore un portrait précis du système de santé mentale.

According to the Canadian Community Health Survey–Mental Health component, conducted by Statistics Canada in 2012, 10.1% or approximately 2.8 million Canadians aged 15 and older experienced at least 1 mental or substance use disorder, including depression, bipolar disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, or alcohol, cannabis, or substance abuse or dependence, in the 12 months prior to the survey. Statistics from the Mental Health Commission of Canada (MHCC)2 revealed that more than 6.7 million people in Canada are currently living with a mental disorder or illness. Even though a number of public services and programs that target this group are provided with funding from a range of health and nonhealth ministries, the magnitude of the expenditures is seldom estimated.

In an article in the Canadian Journal of Psychiatry in 2008, a wide variety of mental health costs per person and mental health expenditures as a percentage of total health expenditures were reported for the provinces. Jacobs et al.1 reported that total public and private mental health expenditures in Canada in 2003-2004 amounted to $6.6 billion, of which $5.5 billion was from public sources. Furthermore, public mental health expenditures, a widely used indicator of mental health service availability, was about 6% of the total public health expenditures, with wide variations occurring between the provinces. In the interceding years, a great deal of attention was paid to this issue in reports by the Senate of Canada,3 the Parliament,4 and the MHCC.2 Nevertheless, any policies or programs to promote mental health were left to be implemented by each province. In this article, we consider the publicly funded health care costs associated with mental illness a decade after Jacobs et al.1 (fiscal year [FY] 2003) estimated expenditures for publicly funded mental health services. We consider data for FY 2013, the most recent year for which data are available, and compare the estimates to those of FY 2003.

Methodology for the Cost Estimates

Expenditure Categories

We adapt a government or public perspective in our cost estimations, focusing on public mental health expenditures. We collected data for the following expenditure categories: general hospital, psychiatric hospital, total clinical payments to physicians, community mental health centers, and pharmaceutical services. We adjusted the 2003-2004 data for expenditures to 2013-2014 dollars using the provincial Consumer Price Index.5 Expenditures for mental health services were expressed per capita and as percentages of total provincial health spending.

Cost Comparison

For Jacobs et al.1 and the present studies, hospital inpatient and physician billing data were obtained from the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI) national databases and they were comparable for the years under examination. In addition, pharmaceutical expenses for the study by Jacobs et al.1 were estimated based on information from provincial drug plans and the health ministries. For the present study, however, pharmaceutical expenses were obtained from the Intercontinental Marketing Services (IMS) health database. To compare the publicly funded proportion of the psychiatric drug costs for FY 2003 and FY 2013, we used the public/private ratio for drug costs in both years in each province from the CIHI’s National Health Expenditure Trends, 1975 to 2016. In the study by Jacobs et al.,1 outpatient mental health services, such as community mental health services, were obtained from provincial sources or from stand-alone reports. Because the relevant information for FY 2013 was not publicly available, it was excluded from the cost comparison in the present study.

Hospitals

Inpatient costs for FY 2013 were estimated from the annual volume and average cost data for mental health hospitalizations in psychiatric and general hospitals. Hospital inpatient costs per inpatient case were estimated using the interactive database, the Patient Cost Estimator (PCE),6 developed by the CIHI. The PCE provides estimated average costs per Case Mixed Group (CMG) and average total length of stay (LOS) by CMG, by province and age group. We included all cases reported in the CIHI national PCE database that were in psychiatric-related CMGs, from CMG 670 to 709. Although the PCE contains only costs for typical patients, we assumed that the costs per day for both typical and atypical cases (i.e., deaths, transfers, sign-outs, and long-stay cases) were the same.

The PCE interactive tool focuses on typical-only inpatients, or hospital patients receiving a normal and expected course of treatment, which represents approximately 84% of all inpatient cases. Atypical outcomes have been excluded from calculations for the estimated average per patient cost (measured by Patient Cost Estimator, CIHI6). Because we wanted to include both typical and atypical inpatient costs, we estimated the total costs in 2 steps: first, an average mental health–related inpatient cost per day was calculated using the total reported typical inpatient costs for psychiatric inpatient cases and average total days reported for provinces. The resulting typical cost per day was used as an approximation for the average total (typical and atypical) cost per day. To estimate the total inpatient costs, we used all inpatient days, including both typical and atypical cases that were in psychiatric-related CMGs, as reported in the CIHI Hospital Mental Health Services Database (HMHDB),7 and multiplied this by the average cost per day. The HMHDB contains data from all provinces in Canada in terms of total days stayed for mental health and addiction inpatient cases. HMHDB data were collected from administrative separation (discharge or death) records of psychiatric and general hospitals.

Clinical Payments to Physicians

Data for clinical payments for mental illness consultations were obtained from the CIHI’s National Physician Database (NPDB),8 2014-2015 data release. The NPDB includes clinical payment data, where total payment refers to the sum of the physicians’ clinical payments from fee-for-service and alternative payment systems, including salary, sessional, capitation, and blended payment methods. Fee-for-service payments are based on billing data submitted to the NPDB; alternative clinical payment data were collected through provincial and territorial Ministry of Health reports. In the NPDB, clinical payments to physicians are a product of services and unit fees.

Physician specialty designations were assigned and grouped by province and territory, although province-specific variations exist in grouping some of the specialists. In addition, the NPDB8 defines physician specialities by payment plan specialty, which refers to a practice area in which the physician was paid for services; for example, psychiatry includes subspecialties such as neuropsychiatry. Physician specialities were grouped by province and territory; the CIHI NPDB groups them according to their national equivalences.

In FY 2013, the CIHI obtained information on fee-for-service payments for all provinces, and the information for alternative physician payments were for seven provinces. The data for alternative payments were missing for Nova Scotia and Alberta.8 Alternative forms of clinical payment for psychiatrists in Nova Scotia and Alberta were thus excluded.

Pharmaceuticals

Psychotropic drugs are defined as including psychotherapeutic outpatient prescription medications, such as antidepressants, major and minor tranquilizers, analeptics, sedatives, and other psychotherapeutic medications. Other psychotropic-related medications, such as medications for neurological disorders, and smoking deterrents were excluded. In addition, medications dispensed in hospitals or in psychiatric institutions were not included in this category.

The data for estimating publicly funded drug expenditures were obtained from IMS Health Canada. IMS Health Canada maintains a national database that measures the number of prescriptions dispensed by Canadian retail pharmacies (IMS Health Canada). We obtained total retail sales volumes and dollar amounts for each province from the IMS CompuScript database. Sales information from IMS contains total psychotherapeutic drug expenditures; medications covered by provincial drug plans were integrated with medications paid privately, either by out of pocket or through third-party private insurers. To distinguish the public portion from the total drug expenditures, we estimated the publicly funded proportion of the prescription drug costs using information from the National Health Expenditure Trends, 1975-2016,9 from CIHI.

Comparison with FY 2003 Results

The cost estimates for the key service categories in this analysis were compared with the FY 2003 results.1 The service categories used in comparing public mental health expenditure were hospital inpatient, drugs, and physician services since this information has been reported consistently across provinces and over the years.

Jacobs et al.1 provided mental health service expenditures based on FY 2003; the cost estimates included pharmaceuticals by private and public sources. Therefore, we estimated the proportion of psychiatric drugs that were publicly funded, based on the public/private ratio of all drug costs (including psychiatric and nonpsychiatric drugs) in each province for FY 2003. We then adjusted the FY 2003 mental health service expenditures to 2013 dollars using the provincial Statistics Canada Consumer Price Index.5 We obtained per capita values for expenditures for both years by adjusting for provincial populations using data from Statistics Canada.10 The results for FY 2003 and FY 2013 were expressed per capita.

Results

Nominal Results

Provincial expenditures for mental health services for FY 2013 are shown in Table 1. Total public spending for the included mental health and addiction programs/services was estimated to be $6.75 billion. Of the estimated spending on mental health services, the largest costs were in hospitalization ($4.02 billion, 59.6%), clinical payments ($1.69 billion, 25%), and then prescribed psychotherapeutic medications ($1.04 billion, 15.4%).

Table 1.

Total Mental Health Service Expenditures, by Province, in Fiscal Year (FY) 2013.

| Mental Health Care Services (2013-2014) | NL | PE | NS | NB | QC | ON | MB | SK | AB | BC | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population estimates, 2013-2014 (in millions) | 0.53 | 0.15 | 0.94 | 0.76 | 8.16 | 13.56 | 1.27 | 1.11 | 4.00 | 4.59 | 35.04 |

| ($000,000) | |||||||||||

| General hospital inpatient costs | 29.7 | 17.2 | 59.6 | 97.5 | 490.7 | 844.7 | 94.5 | 77.9 | 328.0 | 356.4 | 2,396.2 |

| Psychiatric hospital inpatient costs | 19.2 | 1.6 | 39.3 | 111.8 | 203.5 | 889.3 | 15.3 | 46.8 | 260.3 | 40.1 | 1,627.2 |

| Psychiatrist FFS payment | 6.8 | 3.2 | 6.5 | 6.9 | 273.2 | 417.0 | 28.0 | 14.2 | 149.0 | 142.9 | 1,047.7 |

| Psychiatrist alternative payment | 16.7 | 2.4 | n/a | 17.2 | 120.4 | 38.2 | 17.1 | 20.5 | n/a | 49.5 | 281.9 |

| Total clinical payments to GP for psychotherapy/ counselling | 1.8 | n/a | 3.5 | 3.3 | 14.7 | 175.6 | 5.5 | 9.4 | 92.5 | 50.6 | 356.9 |

| Estimated public-paid amount for psychotherapeutic medications | 12.7 | 3.4 | 26.0 | 18.8 | 332.6 | 367.5 | 32.2 | 32.6 | 115.6 | 101.0 | 1,042.4 |

Note: According to Statistics Canada, data for Newfoundland and Labrador have not been finalized for fiscal years 2013-2014 and 2014-2015 and should be considered preliminary. Fee-for-service (FFS) payments are based on data submitted to the National Physician Database, with the exception of Prince Edward Island for 2008-2009 to 2014-2015, as well as Newfoundland and Labrador for 2010-2011 to 2013-2014, which submitted fee-for-service information with alternative clinical payment data collection. GP, general practitioner.

Comparison of Results

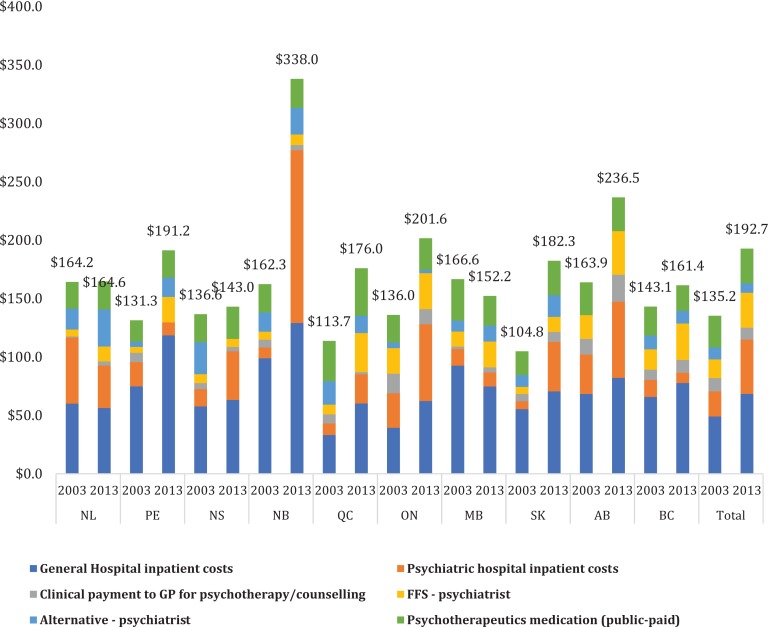

Figure 1 provides an overview comparison of the per capita public mental health expenditures between FY 2003 and FY 2013 by service category, adjusted for inflation. Overall, inflation-adjusted mental health service costs per capita increased from $135.2 to $192.7 over the 10-year period. The increase varied across provinces, with New Brunswick having the largest, due to increases in hospitalization costs.

Figure 1.

Per capita public mental health expenditures by province and in Canada: fiscal year (FY) 2003 versus FY 2013, by category of service. FFS, fee for service; GP, general practitioner.

From 2003 to 2013, mental health–related hospital inpatient costs in Canada substantially increased from $70.4 to $104.2 per capita (Figure 1); moreover, the proportion of inpatient costs to total public mental health costs increased by $1.335 billion to 58.1% in 2013. Variations exist across the provinces in the changes in inpatient costs; for example, the per capita hospital costs in Newfoundland and Labrador, Manitoba, and British Columbia fell or remained constant between 2003 and 2013, while the inpatient costs in other provinces increased substantially during the same period. In addition, fee-for-service clinical payments to psychiatrists significantly increased, while alternative clinical payments to psychiatrists and the cost of psychotherapeutic medication only changed slightly (Figure 1).

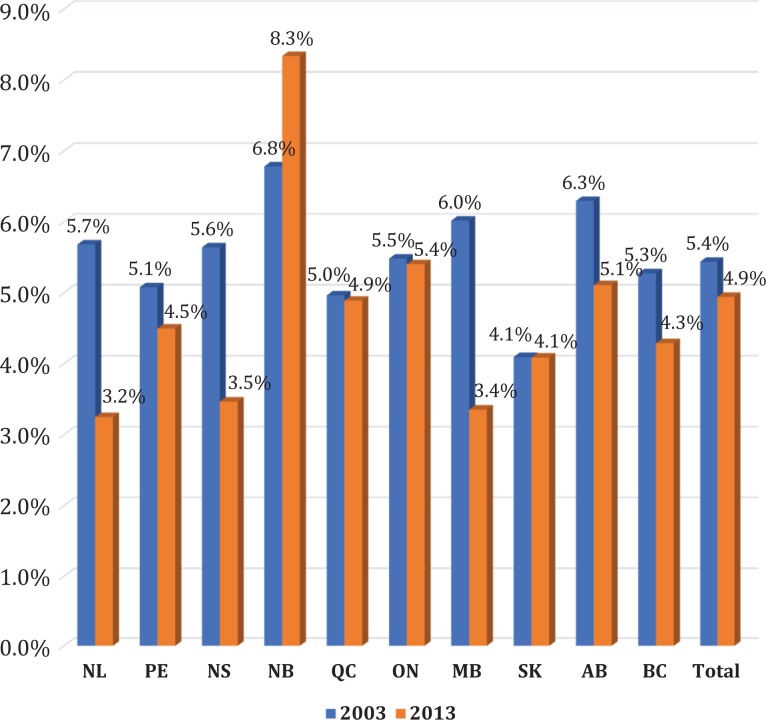

Our results (Figure 2) indicate that overall, mental health services amounted to 4.9% of provincial government health expenditures in FY 2013, compared to 5.4% in FY 2003. Only New Brunswick had an increase, owing to its large increase in mental health hospitalizations.

Figure 2.

Mental health expenditures as a percentage of Canadian and provincial government health expenditure: fiscal year (FY) 2003 versus FY 2013.

Discussion

We measured provincial publicly funded mental health care services for FY 2013, including inpatient services provided by general and psychiatric hospitals, costs of consultations provided by psychiatrists under fee-for-service or alternative payment plans, and prescribed psychotherapeutic medications. Our results during FY 2003 and FY 2013 show that the inflation-adjusted dollar value of public mental health services increased from $135.1 to $192.7 per person. Nevertheless, the percentage of mental health costs with respect to total provincial public health care expenditures decreased overall for the same period, as a national average, from 5.4% to 4.9%.

Compared to the trend in health care expenditures in Canada (CIHI, 2016), inpatient costs for mental health increased by about 6% units, compared to an approximate 0.6% unit increase in the whole health care sector. Physician payments decreased slightly for mental health, while in the whole health care sector, they increased slightly (1.9% units). The relative proportion of publicly funded psychotropic drug costs decreased by about 4.6% units from all mental health costs while the general trend in health care remained unchanged (CIHI, 2016). These trends indicate that in mental health care compared to other sectors of health care, the main cost driver has been inpatient care. In addition, the proportion of psychotropic drug costs decreased likely because of the increased use of generic drugs in mental health care.

We excluded community services and addiction services from our estimates, even though these are important components of a balanced mental health and addictions system that we had assessed previously.1 In our previous report, we collaborated with mental health directorates in each province, but this was not possible in the current study due to budget constraints. Instead, we searched the websites of the health ministries of every Canadian province for data on these services. After reviewing the annual reports from each ministry for FY 2013, 7 of the 10 provinces reported budget funding for community mental health services.11–17 The community mental health expenditures, as a percentage of all public provincial health expenditures for FY 2013, ranged from 0.07% in New Brunswick to 2.4% in Saskatchewan. This indicates a wide variation in the reporting of community services.

The large variation in public spending for community mental health services suggests a lack of standardized definitions for the relevant programs/services. This lack of standardization was identified in the CIHI report on community mental health statistics.18 Public spending for community mental health services in Quebec,16 for example, was estimated to be $463.8 million or $56.9 per capita in FY 2013, which was about 10 times higher than that reported in Ontario ($5.8 per capita). In Quebec, du Ministère de la Santé et des Services Sociaux (MSSS) is responsible for overseeing and funding the delivery of health and social services. The MSSS website provides detailed information on the utilization and cost of mental health services and programs, which is publicly available in French. For the other provinces; however, similar information is not publicly available. Projecting the Quebec amount pro rata to other provinces would bring provincial Canadian community mental services to a total of $1.992 billion and Canadian public mental health expenditures to $8.7 billion, or 6.4% of all public health care expenditures. Further research in this topic is needed.

Our results indicate that, while mental health services have increased in “physical” (inflation-adjusted) terms, they have not kept up with overall health expenditures. As stated, expenditures for community mental health are missing from our analysis. Information about these expenditures is essential for measuring the progress of the mental health systems in terms of de-hospitalization. The move to community-based care is one of the most important phenomena that aggregate studies, such as this one, can address. Without such data, we continue to have an incomplete picture of the Canadian mental health system. At the same time, the federal government recently announced a 10-year, $5 billion mental health transition fund to serve as a lever towards more community care for those who are severely mentally ill or for primary care nested treatment for those who also have a mental disorder.19 More consistent monitoring of mental health spending could be achieved by supporting the provinces to report their community expenditures in a standardized manner. This was the case when the Public Health Agency of Canada reported funding across the provinces using standardized aggregate data for its chronic disease surveillance system, which also covered mental health.20 Standardized reporting for community care will also enable us to conduct a more robust assessment of the policy changes 10 years hence.

Our analysis reveals considerable gaps in information and reporting for mental health services and their costs in Canada. The following main limitations have an impact on the accuracy of our estimates. First, from the publicly accessible data sets, it is difficult to obtain utilization and cost data for persons served or information regarding sex- or age-specific subgroups. This hinders making detailed comparisons for the mental health care among the provinces and between mental health care and other sectors in health care. In addition, some provinces did not collect data on mental health services provided by physicians who are paid through alternative forms of payment, and thus these costs are somewhat underestimated. Finally, the use of standard definitions in mental health services and programs in Canada would make these types of comparisons easier in the future.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge help of Dr. Helen-Maria, Vasiliadis.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Partial funding was provided by Mental Health Commission of Canada.

References

- 1. Jacobs P, Yim R, Ohinmaa A, et al. Expenditures on mental health and addictions for Canadian provinces in 2003 and 2004. Can J Psychiatry. 2008;53(5):306–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mental Health Commission of Canada. Making the case for investing in mental health in Canada Ottawa (ON): Mental Health Commission of Canada; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Out of the shadows at last. Transforming mental health, mental illness and addiction services in Canada; [cited 2017 Apr 20]. Available from: http://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2011/sen/yc17-0/YC17-0-391-2-1-eng.pdf.

- 4. Butlet M, Philips K. Current issues in mental health in Canada: the federal role in mental health (in Brief) Publication No. 2013-76-E Ottawa (ON): Library of Parliament; [cited 2017 Apr 20]. Available from: https://lop.parl.ca/Content/LOP/ResearchPublications/2013-76-e.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Statistics Canada. Consumer Price Index Historical Summary (1997 to 2016) Ottawa (ON): Statistics Canada; [cited 2017 Jun 9]. Available from: http://www.statcan.gc.ca/tables-tableaux/sum-som/l01/cst01/econ46a-eng.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Canadian Institute for Health Information. Patient cost estimator: methodological notes and glossary Ottawa (ON): CIHI; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Canadian Institute for Health Information. Hospital mental health database metadata Ottawa (ON): CIHI; 2017; [cited 2017 Apr 27]. Available from: https://www.cihi.ca/en/hospital-mental-health-database-metadata. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Canadian Institute for Health Information. National Physician Database, 2014-2015 Data Release Core; [cited 2017 Apr 27]. Ottawa (ON): CIHI; 2016. Available from: https://secure.cihi.ca/estore/productFamily.htm?locale=en&pf=PFC3268&&media=0. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Canadian Institute for Health Information. National health expenditure trends, 1975 to 2016: Data tables—Series G Ottawa (ON): CIHI; 2016; [cited 2017 Apr 27]. Available from: https://www.cihi.ca/en/access-data-reports/results?query=National+Health+Expenditure+Trends+%28NHEX%29%2C+1975+to+2016+&Search+Submit=. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Statistics Canada. Population by year, by province and territory Ottawa (ON): Statistics Canada; [cited 2017 Apr 20]. Available from: http://www.statcan.gc.ca/tables-tableaux/sum-som/l01/cst01/demo02a-eng.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Alberta Health Services, Addiction and Mental Health. Performance of the addiction and mental health system in Alberta Health Services 2013-2014 Edmonton (AB): Alberta Health Services; 2015; [cited 2017 Apr 29]. Available from: http://www.albertahealthservices.ca/amh,/Page2773.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Government of New Brunswick. News release. Department of Health Budget Estimates released [Press release] Fredericton (NB): Government of New Brunswick; [cited 2017 Apr 29]. Available from: http://www2.gnb.ca/content/gnb/en/news/news_release.2013.04.0335.html 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Government of Nova Scotia. Balanced budget 2013-14 Halifax (NS): Government of Nova Scotia; [cited 2017 Apr 29]. Available from: http://www.novascotia.ca/finance/site-finance/media/finance/budget2013/better_care_sooner_bulletin.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Government of Prince Edward Island. Annual report 2014-15 Charlottetown (PEI): Government of Prince Edward Island; [cited 2017 Apr 29]. Available from: http://www.gov.pe.ca/photos/original/hpei_ar1415_eng.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Government of Saskatchewan. Annual statistical report for 2013-2014. Regina (SK): Government of Saskatchewan-Ministry of Health Medical Services Branch; 2014. [cited 2017 Apr 27]. Available from: https://www.saskatchewan.ca/government/government-structure/ministries/health/other-reports/annual-report-archive#step-3.

- 16. Santé et services sociaux Québec. Publications du ministère de la Santé et des Services sociaux Montreal (QC): Santé et services sociaux Québec; [cited 2017 Apr 29]. Available from: http://publications.msss.gouv.qc.ca/msss/document-001663/. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Treasury Board Secretariat. Public accounts of Ontario. Financial statements of government organizations, 2014-15. Volume 2A; 2015; [cited 2017 Apr 20]. Available from: http://www.fin.gov.on.ca/en/budget/paccts/2015/15_vol2a.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Canadian Institute for Health Information. Community mental health and addiction information: a snapshot of data collection and reporting in Canada Ottawa (ON): CIHI; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lesage A, Bland R, Musgrave I. The case for a federal mental health transition fund. Can J Psychiatry. 2017;62(1):4–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Public Health Agency of Canada. Canadian chronic disease surveillance system Ottawa (ON): Public Health Agency of Canada; [cited 2017 Jun 29]. Available from: http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/surveillance-eng.php. [Google Scholar]