Abstract

Background

Patients with advanced midgut neuroendocrine tumors who have had disease progression during first-line somatostatin analogue therapy have limited therapeutic options. This randomized, controlled trial evaluated the efficacy and safety of lutetium-177 (177Lu)–Dotatate in patients with advanced, progressive, somatostatin-receptor–positive midgut neuroendocrine tumors.

Methods

We randomly assigned 229 patients who had well-differentiated, metastatic midgut neuroendocrine tumors to receive either 177Lu-Dotatate (116 patients) at a dose of 7.4 GBq every 8 weeks (four intravenous infusions, plus best supportive care including octreotide long-acting repeatable [LAR] administered intramuscularly at a dose of 30 mg) (177Lu-Dotatate group) or octreotide LAR alone (113 patients) administered intramuscularly at a dose of 60 mg every 4 weeks (control group). The primary end point was progressionfree survival. Secondary end points included the objective response rate, overall survival, safety, and the side-effect profile. The final analysis of overall survival will be conducted in the future as specified in the protocol; a prespecified interim analysis of overall survival was conducted and is reported here.

Results

At the data-cutoff date for the primary analysis, the estimated rate of progression-free survival at month 20 was 65.2% (95% confidence interval [CI], 50.0 to 76.8) in the 177Lu-Dotatate group and 10.8% (95% CI, 3.5 to 23.0) in the control group. The response rate was 18% in the 177Lu-Dotatate group versus 3% in the control group (P<0.001). In the planned interim analysis of overall survival, 14 deaths occurred in the 177Lu-Dotatate group and 26 in the control group (P = 0.004). Grade 3 or 4 neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, and lymphopenia occurred in 1%, 2%, and 9%, respectively, of patients in the 177Lu-Dotatate group as compared with no patients in the control group, with no evidence of renal toxic effects during the observed time frame.

Conclusions

Treatment with 177Lu-Dotatate resulted in markedly longer progression-free survival and a significantly higher response rate than high-dose octreotide LAR among patients with advanced midgut neuroendocrine tumors. Preliminary evidence of an overall survival benefit was seen in an interim analysis; confirmation will be required in the planned final analysis. Clinically significant myelosuppression occurred in less than 10% of patients in the 177Lu-Dotatate group. (Funded by Advanced Accelerator Applications; NETTER-1 ClinicalTrials.gov number, NCT01578239; EudraCT number 2011-005049-11.)

Neuroendocrine Tumors of the Midgut (which is defined as the jejunoileum and the proximal colon) commonly metastasize to the mesentery, peritoneum, and liver and are frequently associated with the carcinoid syndrome.1,2 Neuroendocrine tumors of the midgut represent the most common type of malignant gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumors and are associated with 5-year survival rates of less than 50% among persons with metastatic disease.3,4 First-line systemic therapy usually consists of a somatostatin analogue for control of both hormonal secretion and tumor growth.5-7 With the exception of everolimus for the treatment of nonfunctional neuroendocrine tumors,8 no standard second-line systemic treatment options are currently available.8,9

Since 1992,10-15 radiolabeled somatostatin analogue therapy (a form of treatment also known as peptide receptor radionuclide therapy) has shown considerable promise for the treatment of advanced, well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumors, a majority of which express high levels of somatostatin receptors to which somatostatin analogues bind.16 This targeted form of systemic radiotherapy allows the delivery of radionuclides directly to tumor cells. Initial efficacy results were based on very high doses of 111In-DTPA0-octreotide,11 but more promising results were subsequently found with 90Y-DOTA0-Tyr3–octreotide (90Y-DOTATOC)17 and with 177Lu-DOTA0-Tyr3–octreotate (177Lu-Dotatate).12 Lutetium-177 (177Lu) is a beta- and gamma-emitting radionuclide with a maximum particle range of 2 mm and a half-life of 160 hours.18 In a single-group trial of 177Lu-Dotatate involving 310 patients who had gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors, complete tumor remissions occurred in 2% of the patients and partial tumor remissions in 28%.12 The median progression-free survival was 33 months.

We report here results from the phase 3 Neuroendocrine Tumors Therapy (NETTER-1) trial, which evaluated the efficacy and safety of 177Lu-Dotatate as compared with high-dose octreotide long-acting repeatable (LAR) in patients with advanced, progressive, somatostatin-receptor–positive midgut neuroendocrine tumors.

Methods

Patients

This international, multicenter, phase 3 trial was conducted at 41 centers in 8 countries worldwide. Eligible patients were adults who had midgut neuroendocrine tumors that had metastasized or were locally advanced, that were inoperable, that were histologically confirmed and centrally verified, and that showed disease progression (according to Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors [RECIST], version 1.119) on either computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) over the course of a maximum period of 3 years during treatment with octreotide LAR (20 to 30 mg every 3 to 4 weeks for at least 12 weeks before randomization). Patients were required to have a Karnofsky performance-status score of at least 60 (on a scale from 0 to 100, with lower numbers indicating greater disability), a tumor with well-differentiated histologic features, and somatostatin receptors present on all target lesions (as confirmed by blinded, independent central review). Welldifferentiated histologic features were defined as a Ki67 index (the percentage of cells that are positive for Ki67 as determined by immunostaining of the primary tumor) of 20% or less; tumors were assessed as low-grade if they had a Ki67 index of 0 to 2%, intermediate-grade if they had a Ki67 index of 3 to 20%, or high-grade if they had a Ki67 index of greater than 20%, with a lower grade indicating a lower rate of proliferative activity. Target lesions were selected from CT or MRI, and the degree of expression of somatostatin receptors was determined on the basis of the lesion that had the highest uptake of radiotracer observed on planar somatostatin receptor scintigraphy within 24 weeks before randomization. All CT and MRI images were reviewed and evaluated for disease progression (according to RECIST criteria) and somatostatin receptor expression by independent central reviewers who were unaware of the treatment assignments.

Key exclusion criteria were a serum creatinine level of more than 150 μmol per liter (1.7 mg per deciliter) or a creatinine clearance of less than 50 ml per minute; a hemoglobin level of less than 8.0 g per deciliter; a white-cell count of less than 2000 per cubic millimeter; a platelet count of less than 75,000 per cubic millimeter; a total bilirubin level of more than 3 times the upper limit of the normal range; a serum albumin level of more than 3.0 g per deciliter, unless the prothrombin time value was within the normal range; treatment with more than 30 mg of octreotide LAR within 12 weeks before randomization; peptide receptor radionuclide therapy at any time before randomization; and any surgery, liver-directed transarterial therapy, or chemotherapy within 12 weeks before randomization.

Trial Design

In this open-label, phase 3 trial, we randomly assigned patients, in a 1:1 ratio, to receive 177Lu-Dotatate plus best supportive care, consisting of octreotide LAR at a dose of 30 mg every 4 weeks for symptom control (177Lu-Dotatate group) or to receive high-dose octreotide LAR, at a dose of 60 mg every 4 weeks (control group). Randomization was performed with the use of a centralized permuted block (block size of 4) randomization scheme, with stratification according to the highest tumor uptake score on somatostatin receptor scintigraphy (grade 2, 3, or 4 on a scale ranging from 0 [no uptake by tumor] to 4 [very intense uptake by tumor] with higher grades indicating a higher level of expression of somatostatin receptors)12 and according to the length of time that a patient had been receiving a constant dose of octreotide (≤6 months or >6 months).

In the 177Lu-Dotatate group, 7.4 GBq (200 mCi) of 177Lu-Dotatate was infused intravenously over a period of 30 minutes. Patients received four infusions every 8 weeks (cumulative radioactivity, 29.6 GBq [800 mCi]) unless unacceptable toxic effects occurred, centrally confirmed disease progression (according to RECIST) was present on imaging, the patient was unable or unwilling to adhere to trial procedures, the patient withdrew consent, or the patient died. For renal protection, an intravenous amino acid solution (Aminosyn II 10% [21.0 g of lysine and 20.4 g of arginine in 2 liters of solution] or VAMIN-18 [18 g of lysine and 22.6 g of arginine in 2 liters of solution]) was administered concomitantly for at least 4 hours, starting 30 minutes before infusion of the radiopharmaceutical. In the 177Lu-Dotatate group, patients continued to receive supportive care with octreotide LAR, which was administered intramuscularly at a dose of 30 mg approximately 24 hours after each infusion of 177Lu-Dotatate and then monthly after completion of all four treatments. In the control group, octreotide LAR at a dose of 60 mg was administered intramuscularly every 4 weeks. In both treatment groups, patients were allowed to receive subcutaneous rescue injections of octreotide in the event of hormonal symptoms (i.e., diarrhea or flushing) associated with their carcinoid syndrome.

Trial Oversight

This trial was sponsored by Advanced Accelerator Applications and was designed by Advanced Accelerator Applications in collaboration with the last two authors. The trial protocol was approved by the investigational review board or independent ethics committee at each participating institution. Contract research organizations monitored the trial and collected, compiled, maintained, and analyzed the data. The trial was performed in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, International Conference on Harmonisation Good Clinical Practice guidelines, and all applicable regulations. All the patients provided written informed consent. An independent data and safety monitoring board oversaw the conduct of the trial. The first draft of the manuscript was prepared by the first author with assistance from a professional medical writer funded by the sponsor. All the authors contributed to subsequent drafts and agreed to submit the manuscript for publication. All the authors vouch for the accuracy and completeness of the data and the analysis and for the fidelity of the trial to the protocol. The protocol and statistical analysis plan are available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org.

End Points and Assessments

The primary end point was progression-free survival, which was defined as the time from randomization to documented disease progression (as evaluated by independent central review by radiologists who were unaware of the treatment assignments) or death from any cause. Secondary end points included the objective response rate, overall survival (defined as the time from randomization to death from any cause), safety, and the side-effect profile. An objective tumor assessment on CT or MRI was performed every 12 weeks after the date of randomization in both treatment groups. The treatment was considered to have failed if a patient had progressive disease on imaging, according to central assessment with the use of RECIST criteria, and patients with treatment failure proceeded directly to the long-term follow-up phase. We calculated the response rate as the percentage of patients who had a response according to RECIST (sum of partial responses and complete responses). Definitions of all response categories are provided in the protocol.

Safety was assessed (at least every 2 to 12 weeks, depending on the phase of the trial [treatment phase or follow-up phase] and treatment group) on the basis of adverse events (which were graded according to the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, version 4.03), laboratory results (hematologic, chemical, and urologic), physical examinations, vital signs, electrocardiography, and Karnofsky performance status. Additional details are provided in the Supplementary Appendix, available at NEJM.org.

Statistical Analysis

We calculated the required number of patients for the trial assuming that the median progression-free survival would be 30 months in the 177Lu-Dotatate group and 14 months in the control group, the study would have 90% nominal power at an alpha level of 5%, and the prespecified enrollment period and follow-up period for both groups would be 18 months. On the basis of those assumptions, we calculated that we needed a sample of 124 patients, and the analysis of the primary end point was planned to be conducted after at least 74 events of disease progression or death that were centrally confirmed and could be evaluated had occurred. However, the sample size of the trial was adjusted to 230 patients to enable us to detect a statistically significant and clinically relevant difference between the two treatment groups in overall survival as a secondary end point. This calculation was based on the assumption that the median overall survival would be 50 months in the 177Lu-Dotatate group and 32 months in the control group, with 80% nominal power at an alpha level of 5%, and a prespecified enrollment period of 18 months and a long-term follow-up period of 60 months. A prespecified interim analysis of overall survival was conducted at the time of the analysis of progression-free survival. The final analysis of overall survival is planned to be performed either after 158 deaths have occurred or 5 years after the last patient underwent randomization, whichever occurs first.

All patients who underwent randomization were included in the analyses of efficacy, demographics, and baseline characteristics. The safety population, which comprised all patients who underwent randomization and received at least one dose of trial treatment, was used for all safety analyses. The median point estimate and 95% confidence interval for progression-free survival and overall survival were estimated by means of the Kaplan–Meier method. Objective response rates and corresponding 95% confidence intervals were calculated for each treatment group and were compared with the use of Fisher's exact test. Survival curves were compared with the use of an unstratified log-rank test and were tested against the null hypothesis. Hazard ratios were estimated with the use of an unstratified Cox proportional-hazards model.

Results

Patients

From September 2012 through mid-January 2016, a total of 229 patients underwent randomization at 41 sites (27 sites in Europe and 14 in the United States); 221 of the 229 patients who underwent randomization received at least one dose of trial treatment, including 111 patients in the 177Lu-Dotatate group and 110 in the control group (safety population) (Fig. S1 in the Supplementary Appendix). The demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients were well balanced between the two treatment groups; the ileum was the primary tumor site in a majority of patients (73%), and most patients presented with metastases in the liver (83%), the lymph nodes (62%), or both, typically in the mesentery or retroperitoneum (Table 1, and Table S1 in the Supplementary Appendix). The treatment groups were well balanced with respect to tumor grade (low-grade [grade 1] Ki67 proliferation index in 66% of patients in the 177Lu-Dotatate group and in 72% in the control group) and with respect to the highest uptake of tumor somatostatin radiotracer (high-grade [grade 4] uptake in 61% of patients in the 177Lu-Dotatate group and in 59% of patients in the control group). Serum chromogranin A levels and 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid levels in a 24-hour urine specimen were similar in the two treatment groups. Approximately 80% of the patients had undergone previous surgical resection (78% in the 177Lu-Dotatate group and 82% in the control group), and nearly half the patients had undergone a previous form of systemic therapy other than somatostatin analogue therapy (41% of patients in the 177Lu-Dotatate group and 45% in the control group).

Table 1. Demographic and Baseline Clinical Characteristics of All Patients Who Underwent Randomization*.

| Characteristic | 177Lu-Dotatate Group (N = 116) | Control Group (N = 113) |

|---|---|---|

| Sex — no. (%) | ||

| Male | 63 (54) | 53 (47) |

| Female | 53 (46) | 60 (53) |

| Age — yr | 63±9 | 64±10 |

| Body-mass index† | 25±5 | 26±7 |

| Median time since diagnosis — yr | 3.8 | 4.8 |

| Primary tumor site — no. (%) | ||

| Ileum | 86 (74) | 82 (73) |

| Small intestine, not otherwise specified | 11 (9) | 12 (11) |

| Midgut, not otherwise specified | 9 (8) | 7 (6) |

| Jejunum | 6 (5) | 9 (8) |

| Right colon | 3 (3) | 1 (1) |

| Appendix | 1 (1) | 2 (2) |

| Site of metastasis — no. (%) | ||

| Liver | 97 (84) | 94 (83) |

| Lymph nodes | 77 (66) | 65 (58) |

| Mesentery | 17 (15) | 8 (7) |

| Bone | 13 (11) | 12 (11) |

| Other | 15 (13) | 10 (9) |

| Peritoneum | 7 (6) | 10 (9) |

| Lungs | 11 (9) | 5 (4) |

| Ovaries | 1 (1) | 9 (8) |

| Somatostatin receptor scintigraphy, Krenning scale — no. (%)‡ | ||

| Grade 2 | 11 (9) | 12 (11) |

| Grade 3 | 34 (29) | 34 (30) |

| Grade 4 | 71 (61) | 67 (59) |

Plus–minus values are means ±SD. Percentages may not sum to 100 because of rounding.

The body-mass index is the weight in kilograms divided by the square of the height in meters.

The Krenning scale ranges from grade 0 (no uptake by tumor) to grade 4 (very intense uptake by tumor), with higher grades indicating a higher level of expression of somatostatin receptors. The highest grade per patient was reported.

Efficacy

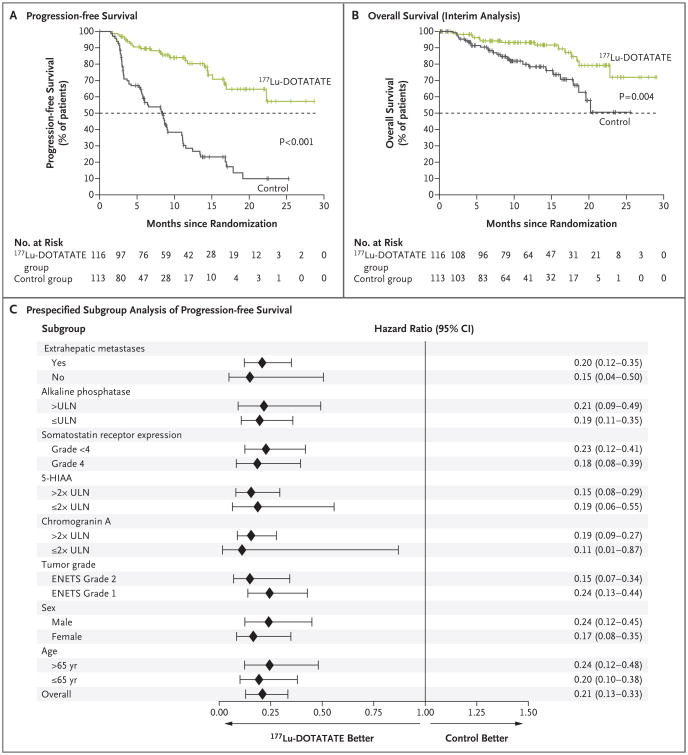

At the time of the data cutoff for the primary analysis (July 24, 2015), 23 events of disease progression or death had occurred in the 177Lu-Dotatate group and 68 such events had occurred in the control group. The estimated rate of progression-free survival at month 20 was 65.2% (95% confidence interval [CI], 50.0 to 76.8) in the 177Lu-Dotatate group and 10.8% (95% CI, 3.5 to 23.0) in the control group. The median progression-free survival had not yet been reached in the 177Lu-Dotatate group and was 8.4 months (95% CI, 5.8 to 9.1) in the control group (hazard ratio for disease progression or death with 177Lu-Dotatate vs. control, 0.21; 95% CI, 0.13 to 0.33; P<0.001), which represented a 79% lower risk of disease progression or death in the 177Lu-Dotatate group than in the control group (Fig. 1A). Consistent treatment benefits associated with 177Lu-Dotatate were observed irrespective of stratification factors and prognostic factors, which included levels of radiotracer uptake on somatostatin receptor scintigraphy, tumor grade, age, sex, and tumor marker levels (Fig. 1C).

Figure 1. Progression-free Survival and Overall Survival.

Panel A shows the results of the Kaplan–Meier analysis of progression-free survival as assessed by independent central reviewers who were unaware of the treatment assignments, and Panel B the results of the planned interim analysis of overall survival. Tick marks in Panel A represent data censored at the last time the patient was known to be alive and without disease progression and tick marks in Panel B represent data censored at the last time the patient was known to be alive. Panel C shows the effect of trial treatment on progression-free survival in prespecified subgroups. European Neuroendocrine Tumor Society (ENETS) grade 1 indicates a low-grade tumor, and ENETS grade 2 indicates an intermediate-grade tumor. The 177Lu-Dotatate group received 177Lu-Dotatate at a dose of 7.4 GBq every 8 weeks (four intravenous infusions, plus best supportive care including octreotide long-acting repeatable [LAR] administered intramuscularly at a dose of 30 mg). The control group received octreotide LAR alone administered intramuscularly at a dose of 60 mg every 4 weeks. 5-HIAA denotes 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid, CI confidence interval, and ULN upper limit of the normal range.

In addition to the analysis of progression-free survival, we performed a planned interim analysis of overall survival. A total of 14 deaths in the 177Lu-Dotatate group and 26 deaths in the control group were observed, which represented an estimated risk of death that was 60% lower in the 177Lu-Dotatate group than in the control group (hazard ratio for death with 177Lu-Dotatate group vs. control, 0.40; P = 0.004) (Fig. 1B). The O'Brien–Fleming threshold for significance at the first interim analysis was 0.000085. Data were not sufficiently mature to provide an estimate of the median overall survival in either treatment group. Within the population of patients who could be evaluated for tumor response (201 patients), the total number of complete and partial responses was 18 in the 177Lu-Dotatate group and 3 in the control group, which corresponded to response rates of 18% and 3%, respectively (P<0.001) (Table 2).

Table 2. Objective Tumor Response*.

| Response Category | 177Lu-Dotatate Group (N = 101) | Control Group (N = 100) | P Value† |

|---|---|---|---|

| Complete response — no. (%) | 1 (1) | 0 | |

| Partial response — no. (%) | 17 (17) | 3 (3) | |

| Objective response | |||

| No. with response | 18 | 3 | |

| Rate — % (95% CI) | 18 (10–25) | 3 (0–6) | <0.001 |

The objective response rate was defined as the percentage of patients who had a response according to Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) (sum of partial responses and complete responses). Patients for whom no post-baseline computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans or central response data were available (15 patients in the 177Lu-Dotatate group and 13 patients in the control group) were excluded from this analysis (trial is still ongoing).

The P value was calculated with the use of Fisher's exact text.

Treatment Administration and Safety

A majority of patients (77%) in the 177Lu-Dotatate group received all four infusions of 177Lu-Dotatate. A total of eight patients required dose reduction. Details regarding patient exposure to treatment are presented in Table S2 in the Supplementary Appendix.

In total, 201 patients (95% of patients in the 177Lu-Dotatate group and 86% of patients in the control group) had at least one adverse event during the trial. Adverse events that were considered by the investigator to be related to trial treatment occurred in 129 patients: 95 patients (86%) in the 177Lu-Dotatate group and 34 patients (31%) in the control group (Table 3). Adverse events that occurred after the start of treatment and subsequently led to premature withdrawal from the trial occurred in 7 patients (6%) in the 177Lu-Dotatate group and in 10 patients (9%) in the control group. The most common adverse events among patients in the 177Lu-Dotatate group were nausea (65 patients [59%]) and vomiting (52 patients [47%]). A majority of these cases (in 42 of the 65 patients [65%] and in 38 of the 52 patients [73%], respectively) were attributable to amino acid infusions that were performed concurrently with administration of 177Lu-Dotatate, and the events resolved once the infusions were completed. Other common adverse events in the 177Lu-Dotatate group included fatigue or asthenia, abdominal pain, and diarrhea; however, a majority of the patients in whom these events were reported (≥97%) had events of grade 1 or 2 (Table 4). Among patients in the control group, the most common adverse events were gastrointestinal disorders and fatigue or asthenia. The rates of grade 3 or 4 adverse events were similar in the two groups; however, grade 3 or 4 neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, and lymphopenia were reported in 1%, 2%, and 9% of patients, respectively, in the 177Lu-Dotatate group versus no patients in the control group. These hematologic events were transient (Fig. S2 in the Supplementary Appendix). No evidence of renal toxic effects was seen among patients in the 177Lu-Dotatate group (Fig. S3 in the Supplementary Appendix) during the observed time frame (median duration of follow-up, 14 months).

Table 3. Overview of Adverse Events (Safety Population)*.

| Event | 177Lu-Dotatate Group (N = 111) | Control Group (N = 110) | P Value† |

|---|---|---|---|

| number of patients (percent) | |||

|

| |||

| Adverse event | |||

|

| |||

| Any | 106 (95) | 95 (86) | 0.02 |

| Related to treatment | 95 (86) | 34 (31) | <0.001 |

|

| |||

| Serious adverse event | |||

|

| |||

| Any | 29 (26) | 26 (24) | 0.76 |

| Related to treatment | 10 (9) | 1 (1) | 0.01 |

|

| |||

| Withdrawal from trial because of adverse event | |||

|

| |||

| Because of any adverse event | 7 (6) | 10 (9) | 0.46 |

| Because of adverse event related to treatment | 5 (5) | 0 | 0.06 |

The safety population included all patients who underwent randomization and received at least one dose of trial treatment.

P values were calculated with the use of Fisher's exact text.

Table 4. Adverse Events (Safety Population).*.

| Event | 177Lu-Dotatate Group (N = 111) | Control Group (N = 110) | P Value† | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any Grade | Grade 3 or 4 | Any Grade | Grade 3 or 4 | Any Grade | |||

| number of patients (percent) | |||||||

| Any adverse event | 105 (95) | 46 (41) | 92 (84) | 36 (33) | 0.01 | ||

| Gastrointestinal disorders | |||||||

| Nausea | 65 (59) | 4 (4) | 13 (12) | 2 (2) | <0.001 | ||

| Vomiting | 52 (47) | 8 (7) | 11 (10) | 1 (1) | <0.001 | ||

| Abdominal pain | 29 (26) | 3 (3) | 29 (26) | 6 (5) | 1.00 | ||

| Diarrhea | 32 (29) | 3 (3) | 21 (19) | 2 (2) | 0.11 | ||

| Distension | 14 (13) | 0 | 15 (14) | 0 | 0.84 | ||

| General disorders | |||||||

| Fatigue or asthenia | 44 (40) | 2 (2) | 28 (25) | 2 (2) | 0.03 | ||

| Edema peripheral | 16 (14) | 0 | 8 (7) | 0 | 0.13 | ||

| Blood disorders | |||||||

| Thrombocytopenia | 28 (25) | 2 (2) | 1 (1) | 0 | <0.001 | ||

| Anemia | 16 (14) | 0 | 6 (5) | 0 | 0.04 | ||

| Lymphopenia | 20 (18) | 10 (9) | 2 (2) | 0 | <0.001 | ||

| Leukopenia | 11 (10) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 | 0.005 | ||

| Neutropenia | 6 (5) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 | 0.12 | ||

| Musculoskeletal disorders | |||||||

| Musculoskeletal pain | 32 (29) | 2 (2) | 22 (20) | 1 (1) | 0.16 | ||

| Nutrition disorders | |||||||

| Decreased appetite | 20 (18) | 0 | 9 (8) | 3 (3) | 0.04 | ||

| Nervous system disorders | |||||||

| Headache | 18 (16) | 0 | 5 (5) | 0 | 0.007 | ||

| Dizziness | 12 (11) | 0 | 6 (5) | 0 | 0.22 | ||

| Vascular disorders | |||||||

| Flushing | 14 (13) | 1 (1) | 10 (9) | 0 | 0.52 | ||

| Skin disorders | |||||||

| Alopecia | 12 (11) | 0 | 2 (2) | 0 | 0.01 | ||

| Respiratory disorders | |||||||

| Cough | 12 (11) | 0 | 6 (5) | 0 | 0.22 | ||

Shown are all adverse events that were reported in at least 10% of the patients in the 177Lu-Dotatate group, with the exception of neutropenia, which was reported in less than 10% of the patients in the 177Lu-Dotatate group. For the individual events, the system organ classes in the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA) hierarchy are shown in bold and are followed by the MedDRA preferred terms (not bold). The safety population included all patients who underwent randomization and received at least one dose of trial treatment.

P values were calculated with the use of Fisher's exact text.

The myelodysplastic syndrome is an adverse event of potential interest in this trial, given the long-term risk of the myelodysplastic syndrome or acute leukemia that has been reported previously in approximately 2% of patients.20,21 Before the data cutoff date, one patient in the 177Lu-Dotatate group of our trial (0.9%) who had a history of monoclonal gammopathy of unknown clinical significance had cytopenias; the patient subsequently underwent a bone marrow biopsy that revealed histologic changes consistent with the myelodysplastic syndrome that were considered by the investigator to be possibly related to the investigational therapy.

Discussion

In this randomized, phase 3 trial involving patients with progressive midgut neuroendocrine tumors, treatment with 177Lu-Dotatate resulted in a risk of progression or death that was 79% lower than the risk associated with high-dose octreotide LAR. The estimated rate of progression-free survival at month 20 was 65.2% (95% CI, 50.0 to 76.8) in the 177Lu-Dotatate group and 10.8% (95% CI, 3.5 to 23.0) in the control group. The median progression-free survival was 8.4 months in the control group and had not yet been reached in the 177Lu-Dotatate group. A subgroup analysis showed consistent benefit across major subgroups. The response rate of 18% in the 177Lu-Dotatate group (as compared with 3% in the control group) is also notable given that response rates above 5% have not been observed in large randomized clinical trials of other systemic therapies in this patient population.22-25 Although our trial has not yet reached the point at which the median overall survival can be calculated, the results of the interim analysis suggest longer overall survival with 177Lu-Dotatate than with high-dose octreotide LAR. The final analysis of overall survival is planned to be performed either after 158 deaths have occurred or 5 years after the last patient underwent randomization, whichever occurs first. 177Lu-Dotatate, when administered concomitantly with a renalprotective agent, was associated with low rates of grade 3 or 4 hematologic toxic effects and showed no evidence of renal toxic effects over the trial time frame (median duration of followup, 14 months).

Radiolabeled somatostatin analogues provide a means of delivering targeted radiation with a high therapeutic index to tumors that express somatostatin receptors.12-15,20,21,26-28 Data from nonrandomized trials of 177Lu-Dotatate have consistently shown high response rates and long durations of median progression-free survival in heterogeneous patient populations with gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors.12,26,29,30 The NETTER-1 trial validates these early-phase data in the context of a prospective, randomized trial.

In summary, 177Lu-Dotatate resulted in markedly longer progression-free survival than high-dose octreotide LAR and was associated with limited acute toxic effects in a population of patients who had progressive neuroendocrine tumors that originated in the midgut.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by Advanced Accelerator Applications.

We thank the participating patients and their families; the global network of research nurses, trial coordinators, and operations staff for their contributions; and the investigators whose patients were enrolled in this trial (a list of the investigators can be found in the Supplementary Appendix).

Appendix.

The authors' full names and academic degrees are as follows: Jonathan Strosberg, M.D., Ghassan El-Haddad, M.D., Edward Wolin, M.D., Andrew Hendifar, M.D., James Yao, M.D., Beth Chasen, M.D., Erik Mittra, M.D., Ph.D., Pamela L. Kunz, M.D., Matthew H. Kulke, M.D., Heather Jacene, M.D., David Bushnell, M.D., Thomas M. O'Dorisio, M.D., Richard P. Baum, M.D., Harshad R. Kulkarni, M.D., Martyn Caplin, M.D., Rachida Lebtahi, M.D., Timothy Hobday, M.D., Ebrahim Delpassand, M.D., Eric Van Cutsem, M.D., Ph.D., Al Benson, M.D., Rajaventhan Srirajaskanthan, M.D., Marianne Pavel, M.D., Jaime Mora, M.D., Jordan Berlin, M.D., Enrique Grande, M.D., Nicholas Reed, M.D., Ettore Seregni, M.D., Kjell Öberg, M.D., Ph.D., Maribel Lopera Sierra, M.D., Paola Santoro, Ph.D., Thomas Thevenet, Pharm.D., Jack L. Erion, Ph.D., Philippe Ruszniewski, M.D., Ph.D., Dik Kwekkeboom, M.D., Ph.D., and Eric Krenning, M.D., Ph.D.

From the Moffitt Cancer Center, Tampa, FL (J.S., G.E.-H.); Markey Cancer Center, University of Kentucky, Lexington (E.W.); Cedars Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles (A.H.), and Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford (E.M., P.L.K.) — both in California; University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center (J.Y., B.C.) and Excel Diagnostics Imaging Clinic (E.D.), Houston; Dana–Farber Cancer Institute, Boston (M.H.K., H.J.); University of Iowa, Iowa City (D.B., T.M.O.); Zentralklinik, Bad Berka (R.P.B., H.R.K.), and Charité-Universitätsmedizin, Berlin (M.P.) — both in Germany; Royal Free Hospital (M.C.) and King's College Hospital NHS Foundation Trust (R.S.), London, and Beatson Oncology Centre, Glasgow (N.R.) — all in the United Kingdom; Hôpital Beaujon, Clichy (R.L., P.R.), and Advanced Accelerator Applications, St. Genis-Pouilly (T.T.) — both in France; Mayo Clinic College of Medicine, Rochester, MN (T.H.); University Hospitals and KU Leuven, Leuven, Belgium (E.V.C.); Robert H. Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Center, Chicago (A.B.); Hospital Universitari de Bellvitge, Barcelona (J.M.), and Hospital Universitario Ramón y Cajal, Madrid (E.G.) — both in Spain; Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville (J.B.); Fondazione Istituto di Ricovero e Cura a Carattere Scientifico Istituto Nazionale dei Tumori, Milan (E.S.); University Hospital, Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden (K.O.); Advanced Accelerator Applications USA, New York (M.L.S., P.S., J.L.E.); and Erasmus Medical Center, Rotterdam, the Netherlands (D.K., E.K.).

Footnotes

Presented in part at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, Chicago, June 3–7, 2016.

Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org.

References

- 1.Kulke MH, Mayer RJ. Carcinoid tumors. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:858–68. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199903183401107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Strosberg JR, Weber JM, Feldman M, Coppola D, Meredith K, Kvols LK. Prognostic validity of the American Joint Committee on Cancer staging classification for midgut neuroendocrine tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:420–5. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.44.5924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yao JC, Hassan M, Phan A, et al. One hundred years after “carcinoid”: epidemiology of and prognostic factors for neuroendocrine tumors in 35,825 cases in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3063–72. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.4377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Modlin IM, Lye KD, Kidd M. A 5-decade analysis of 13,715 carcinoid tumors. Cancer. 2003;97:934–59. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kvols LK, Moertel CG, O'Connell MJ, Schutt AJ, Rubin J, Hahn RG. Treatment of the malignant carcinoid syndrome: evaluation of a long-acting somatostatin analogue. N Engl J Med. 1986;315:663–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198609113151102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rinke A, Müller HH, Schade-Brittinger C, et al. Placebo-controlled, double-blind, prospective, randomized study on the effect of octreotide LAR in the control of tumor growth in patients with metastatic neuroendocrine midgut tumors: a report from the PROMID Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:4656–63. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.8510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caplin ME, Pavel M, Ćwikła JB, et al. Lanreotide in metastatic enteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:224–33. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1316158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yao JC, Fazio N, Singh S, et al. Everolimus for the treatment of advanced, nonfunctional neuroendocrine tumours of the lung or gastrointestinal tract (RADIANT-4): a randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 study. Lancet. 2016;387:968–77. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00817-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kulke MH, Siu LL, Tepper JE, et al. Future directions in the treatment of neuroendocrine tumors: consensus report of the National Cancer Institute Neuroendocrine Tumor clinical trials planning meeting. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:934–43. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.2056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krenning EP, Kooij PP, Bakker WH, et al. Radiotherapy with a radiolabeled somatostatin analogue, [111In-DTPA-D-Phe1]-octreotide: a case history. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1994;733:496–506. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1994.tb17300.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krenning EP, de Jong M, Kooij PP, et al. Radiolabelled somatostatin analogue(s) for peptide receptor scintigraphy and radionuclide therapy. Ann Oncol. 1999;10(2):S23–9. doi: 10.1093/annonc/10.suppl_2.s23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kwekkeboom DJ, de Herder WW, Kam BL, et al. Treatment with the radiolabeled somatostatin analog [177 Lu-DOTA 0,Tyr3]octreotate: toxicity, efficacy, and survival. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:2124–30. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.2553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bodei L, Cremonesi M, Grana CM, et al. Peptide receptor radionuclide therapy with 177Lu-DOTATATE: the IEO phase I-II study. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2011;38:2125–35. doi: 10.1007/s00259-011-1902-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hörsch D, Ezziddin S, Haug A, et al. Effectiveness and side-effects of peptide receptor radionuclide therapy for neuroendocrine neoplasms in Germany: a multiinstitutional registry study with prospective follow-up. Eur J Cancer. 2016;58:41–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2016.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Imhof A, Brunner P, Marincek N, et al. Response, survival, and long-term toxicity after therapy with the radiolabeled somatostatin analogue [90Y-DOTA]-TOC in metastasized neuroendocrine cancers. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:2416–23. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.7873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krenning EP, Kwekkeboom DJ, Bakker WH, et al. Somatostatin receptor scintigraphy with [111In-DTPA-D-Phe1]- and [123I-Tyr3]-octreotide: the Rotterdam experience with more than 1000 patients. Eur J Nucl Med. 1993;20:716–31. doi: 10.1007/BF00181765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Valkema R, Pauwels S, Kvols LK, et al. Survival and response after peptide receptor radionuclide therapy with [90Y-DOTA0,Tyr3]octreotide in patients with advanced gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Semin Nucl Med. 2006;36:147–56. doi: 10.1053/j.semnuclmed.2006.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van der Zwan WA, Bodei L, Mueller-Brand J, de Herder WW, Kvols LK, Kwekkeboom DJ. GEPNETs update: radionuclide therapy in neuroendocrine tumors. Eur J Endocrinol. 2015;172:R1–8. doi: 10.1530/EJE-14-0488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Therasse P, Arbuck SG, Eisenhauer EA, et al. New guidelines to evaluate the response to treatment in solid tumors. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:205–16. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.3.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bodei L, Kidd M, Paganelli G, et al. Long-term tolerability of PRRT in 807 patients with neuroendocrine tumours: the value and limitations of clinical factors. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2015;42:5–19. doi: 10.1007/s00259-014-2893-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sabet A, Ezziddin K, Pape UF, et al. Long-term hematotoxicity after peptide receptor radionuclide therapy with 177Lu-octreotate. J Nucl Med. 2013;54:1857–61. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.112.119347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Janson ET, Oberg K. Long-term management of the carcinoid syndrome: treatment with octreotide alone and in combination with alpha-interferon. Acta Oncol. 1993;32:225–9. doi: 10.3109/02841869309083916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ducreux M, Ruszniewski P, Chayvialle JA, et al. The antitumoral effect of the long-acting somatostatin analog lanreotide in neuroendocrine tumors. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:3276–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.03210.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pavel M, O'Toole D, Costa F, et al. ENETS consensus guidelines update for the management of distant metastatic disease of intestinal, pancreatic, bronchial neuroendocrine neoplasms (NEN) and NEN of unknown primary site. Neuroendocrinology. 2016;103:172–85. doi: 10.1159/000443167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pavel ME, Hainsworth JD, Baudin E, et al. Everolimus plus octreotide longacting repeatable for the treatment of advanced neuroendocrine tumours associated with carcinoid syndrome (RADIANT-2): a randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 study. Lancet. 2011;378:2005–12. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61742-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bodei L, Kwekkeboom DJ, Kidd M, Modlin IM, Krenning EP. Radiolabeled somatostatin analogue therapy of gastroenteropancreatic cancer. Semin Nucl Med. 2016;46:225–38. doi: 10.1053/j.semnuclmed.2015.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bergsma H, Konijnenberg MW, Kam BLR, et al. Subacute haematotoxicity after PRRT with (177)Lu-DOTA-octreotate: prognostic factors, incidence and course. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2016;43:453–63. doi: 10.1007/s00259-015-3193-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bergsma H, Konijnenberg MW, van der Zwan WA, et al. Nephrotoxicity after PRRT with (177)Lu-DOTA-octreotate. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2016;43:1802–11. doi: 10.1007/s00259-016-3382-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ezziddin S, Khalaf F, Vanezi M, et al. Outcome of peptide receptor radionuclide therapy with 177Lu-octreotate in advanced grade 1/2 pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2014;41:925–33. doi: 10.1007/s00259-013-2677-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Delpassand ES, Samarghandi A, Zamanian S, et al. Peptide receptor radionuclide therapy with 177Lu-DOTATATE for patients with somatostatin receptor-expressing neuroendocrine tumors: the first US phase 2 experience. Pancreas. 2014;43:518–25. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0000000000000113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.