Abstract

Atypical polypoid adenomyoma (APA) is a rare uterine lesion, which has a high rate of recurrence and malignant transformation. How to treat this disease is crucial for the prognosis, but there are few reports on it.

We retrospectively reviewed the clinical records of all the patients diagnosed with APA after surgical therapy in our hospital. All the clinical information, pathological results, treatment, and outcome were retrieved from the clinical records.

A total of 43 patients were diagnosed with APA. The median age was 56.0 years (range: 17–71 years). Primary treatments included hysteroscopic transcervical resection (TCR) of the lesions in 34 patients (79.1%), hysterectomy and bilateral salping-oophenrectomy in 5 (11.6%), hysterectomy in 1 (2.3%), and primary cytoreductive surgery for ovary cancer in 3. A total of 42 patients were followed up for a mean period of 26.9 months (range 2–57 months). Three of them recurred. One patient underwent hysterectomy after recurrence, and TCR was performed for the other 2. High-dose progestogen was given to the 2 recurrent patients after TCR.

Hysterectomy is the primary therapeutic choice for postmenopausal patients with APA. Conservative treatment of APA with TCR is safe and efficient.

Keywords: atypical polypoid adenomyoma, endometrial adenocarcinoma, hysterectomy, hysteroscopic transcervical resection, surgery

1. Introduction

Atypical polypoid adenomyoma (APA) is a rare uterine lesion, which was firstly reported by Mazur in 1981.[1] Only about 230 cases have been reported up to now. By immunohistochemistry, APA is composed of glandular and squamous cell proliferation with architectural complexity, cytologic atypia of the glands, and a hypercellular smooth muscle in the stroma. Although APA is categorized as a benign lesion previously, recurrence or residual primary lesion has been reported to occur in 30.1% of the patients who were managed conservatively.[2] Moreover, there are increasing number of APA cases manifesting features of malignant disease with high rates of malignant transformation [2–4], and endometrial carcinoma is detected in 8.8% of the APA patients after treatment with curettage or polypectomy.[2] Therefore, current clinical management for APA may be problematic. Owing to the low incidence of APA, current experiences on managing this disease are still very limited, and the inner mechanism of etiology and pathogenesis of APA is not clear. Therefore, APA management should be more complex and must be very cautious, especially for those nulliparous and premenopausal patients.

In this study, we retrospectively reviewed 43 patients with APA treated in our hospital during a 5-year period from January 2012 to December 2016. Diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up results of these patients with APA were described in this report.

2. Methods

This study was approved by the Ethical Committee of Tianjin Central Obstetrics and Gynecology Hospital (Rf.2016–22). We retrospectively reviewed the clinical records of all the patients diagnosed with APA after surgical therapy in our hospital. All the clinical information, pathological results, treatment, and outcome were retrieved from the clinical records. Pathological specimens were rereviewed by 2 experienced pathologists in our hospital. The diagnosis criteria were based on those described by Longacre et al[5]: a biphasic tumor composed of endometrioid-type glands embedded in a myomatous or fibromyomatous stroma.

3. Results

3.1. Demographics and clinical characteristics

A total of 43 patients were diagnosed with APA in our hospital from January, 2012 to June 2016 (Table 1). The median age of the patients was 56.0 years, with a range from 17 to 71 years. Among them, 22 patients were premenopausal (48.8%); 5 of them were nonparous (11.6%) and 3 (7.0%) married were infertile and under fertility treatment. Thirty-six patients (83.72%) had menorrhagia or abnormal uterine bleeding; 4 patients had secondary anemia, and 3 of them were owing to menorrhagia or menostaxis for 10 years and 1 with uterus bleeding for 8 years owing to polycystic ovary syndrome; the other 3 patients were asymptomatic, but ultrasound showed intrauterine light in these patients. Complications were diabetes mellitus in 8, hypertension in 13, and hyperthyroidism in 1. Nine patients had uterine fibroids, 7 uterine glandular myopathy, and 4 with a history of endometrial polyps resection. One patient had a history of breast cancer (after radical surgery and chemotherapy, and treatment with tamoxifen for 1 year).

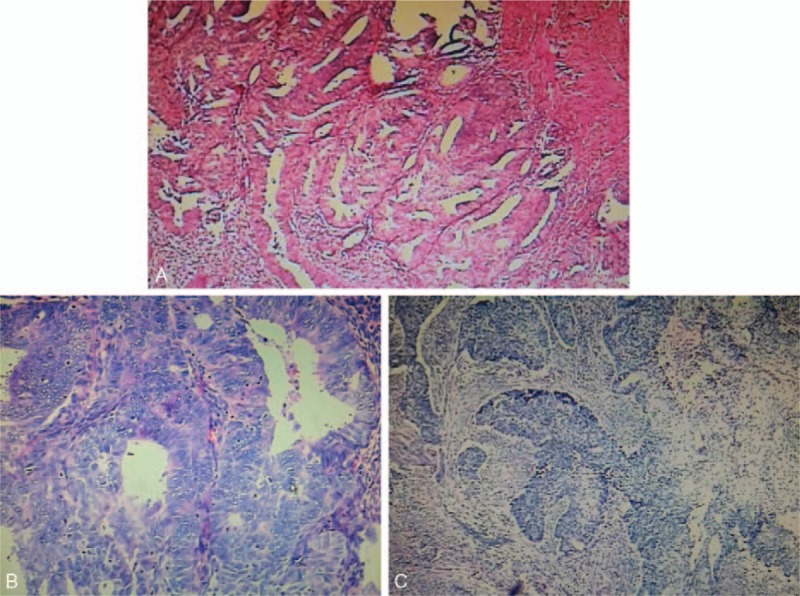

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of the 43 patients with APA of the uterus.

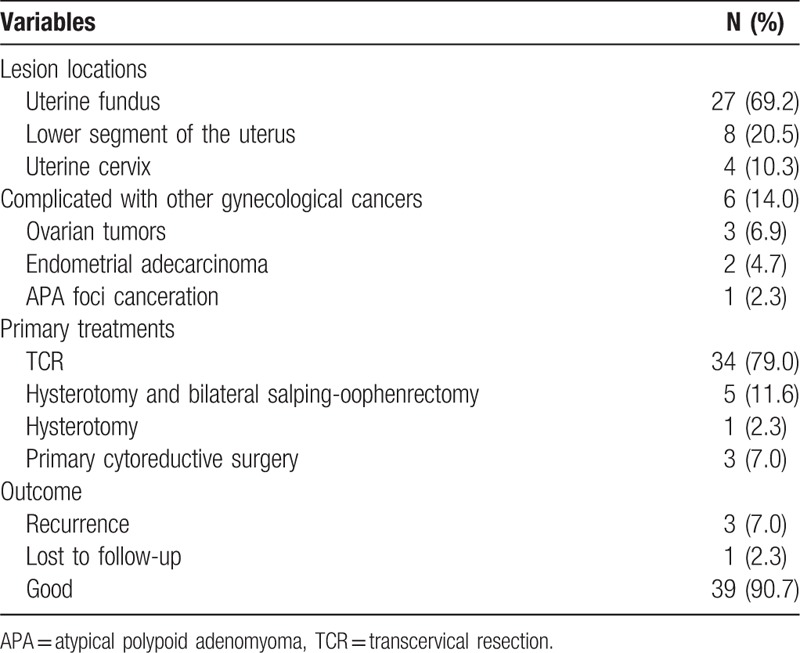

The lesions were mostly located in the uterine fundus (27, 69.2%), followed by the lower segment of the uterus (8, 20.5%) and uterine cervix (4, 10.3%) (T). Figure 1A shows the characteristic lesions of APA under uterine hysteroscopy. The diameters of the lesions ranged from 0.5 to 7.0 cm (mean: 2.0 cm). Three patients were diagnosed by pathological report after surgeries for ovarian tumors (1 serous cystadenocarcinoma, 1 mucinous cystadenocarcinoma, 1 granulosa cell tumor).

Figure 1.

(A) Atypical polypoid adenomyomas (APA) under a hysteroscope. (B) Macroscopic findings of the APA. The lesions have a shape of endometrial polyp (arrow) with or without stalk. The lesions commonly locate in the lower segment of the uterine. (C) The microscopic findings of APA (H&E staining, original magnification ×40). The epithelium of APA is composed with atypical endometrial glands which are interspersed, clustered, or in lobules. The glands derive from endometrium with squamous metaplasia (mulberry-like) and atypical cells at varying degrees. Myofibromatous stroma are present among the glands.

3.2. Treatment

All patients underwent surgeries. Primary treatments included hysteroscopic transcervical resection (TCR) of the lesions in 34 patients (79.1%), hysterectomy and bilateral salping-oophenrectomy in 5 (14.0%), hysterectomy in 1 (2.3%), and primary cytoreductive surgery for ovary cancer in 3. Figure 1B shows the uterus by hysterectomy and macroscopic features of APA. APA takes a shape of endometrial polyp (arrow) with stalk. The surface is smooth. All patients were confirmed with APA by post-surgery histopathological analysis. Figure 1C shows the characteristic microscopic feature of APA by hematoxylin and eosin staining. Immunohistochemical analysis of the lesions by TCR showed that 2 had canceration in the foci of APA, 1 coexisted with endometrial adenocarcinoma; these 3 patients underwent endometrial cancer staging surgery. Postsurgery pathology analysis confirmed that 1 patient with canceration in the foci of APA, 1 with well-differentiated endometrial adenocarcinoma, and 1 with endometrial adenocarcinoma (grade I-II) Figure 2.

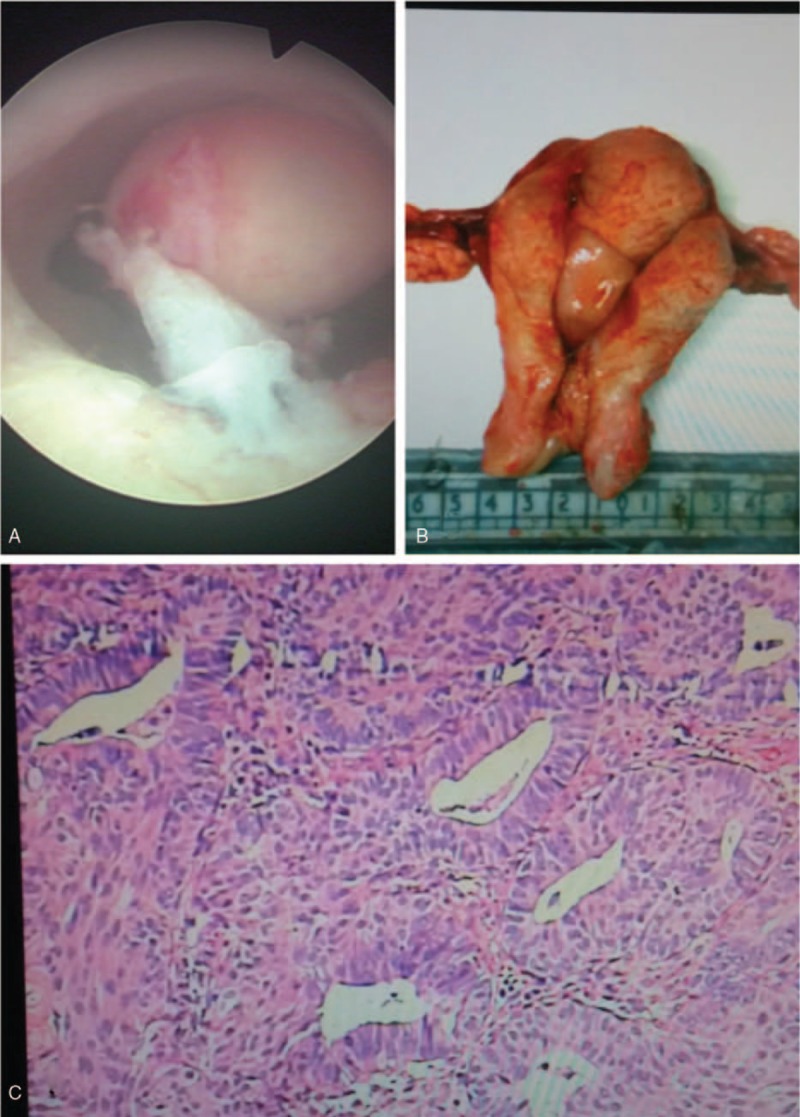

Figure 2.

(A) Atypical polypoid adenomyomas associated with complex atypical hyperplasia of the other endometrium. Foci progressed to be endometrial adenocarcinoma (grade I) and invades into the superficial muscularis (<1/2 of the muscular wall). No obvious vascular cancer emboli found. Immunohistological analysis revealed ER+, PR+, and Ki67 positive rate of 30%, P16 patchy+, P53 ± . (B) Atypical polypoid adenomyomas coexisted with endometrial adenocarcinoma (grade I). Squamous metaplasia of the foci was observed. Cancerous tissue invades into the superficial muscularis (<1/2 of the muscular wall). No obvious vascular cancer emboli were found. Immunohistological analysis revealed that weak ER+, PR+, and P53 ± , P16 diffuse + (H&E staining, original magnification ×40). (C) Atypical polypoid adenomyomas coexisted with endometrial adenocarcinoma (grade I-II). Cancerous tissue invades into superficial muscularis (>1/2 of the muscular wall). No obvious vascular cancer emboli were found. Immunohistological analysis revealed weak ER 60+, PR50%+, and P53 ± (H&E staining, original magnification ×40).

3.3. Follow-up results

Except that 1 patient was lost to follow-up, all patients were followed up for a mean period of 26.9 months (range 2–57 months). These patients were reexamined regularly by transvaginal ultrasonography every 3 to 6 months. Hysteroscopy and endometrial biopsy were also performed if necessary. No pelvic disorders were found in the 12 patients under hysterectomy. Among the other 30 patients treated with only TCR, 3 recurred with a recurrence rate of 7.1%. They recurred at 6 months, 8 months, and 1 year after surgery, respectively. All these 3 patients were in reproductive age, and 1 aged 20 years. Among them, 2 had complex structure of endometrial hyperplasia by pathology analysis. After recurrence, hysterectomy was done for 1 patient and TCR was redone for the other patient who wanted to preserve fertility. Both of them were given with high-dose progestogen after surgery and monitored closely; no recurrence occurred again after a follow-up of 2.5 years and 1.8 years, respectively. The patient aged 20 years had polycystic ovarian syndrome with a history of abnormal uterine bleeding of 8 years; a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system was placed into her uterine after the second TCR and follow-up by hysteroscopy and endometrial biopsy regularly. She also had no recurrence after a follow-up of 1 year.

4. Discussion

APA is an endometrial tumor with low malignant potential and low incidence. APA generally occurs in the reproductive and premenopausal periods, with a reported mean age of about 38 years.[6] Matsumoto et al reported that the majority of patients were nulligravida (75.9%) and nullipara (86.2%). However, about half of our patients were postmenopausal and the mean age of this series of patients was much older than previous reports.[6] The possible reason was that diagnosis of APA in these patients maybe delayed because of mild symptoms or asymptomatic, and some patients were misdiagnosed previously as endometrial polyp or endometrial cancer because of lacking experience in diagnosis of APA.

The most common location of the lesions in our patients was uterine fundus followed by the lower segment of the uterus. The lower uterine segments have been reported to be the most common lesion location.[7] A majority of the patients had an initial presentation of abnormal uterine bleeding, which was consistent with the previous reports.[6]

APA lesion is generally considered as an indicator or precursor for endometrial endometrioid adenocarcinoma or coexisted with endometrioid adenocarcinoma.[4,8–11] The frequency of coexistence of adenocarcinoma in APA was reported to be 8.8%[2] and 17.2%.[6] In our patients, we found 3 patients (6.9%) coexisted with endometrioid adenocarcinoma. The foci of endometrioid adenocarcinoma were found within APA in 2 patients. Up to now, the precise mechanism underlying the development of adenocarcinoma in APA remains poorly understood. Soslow et al found that APA myofibromatous stromal tissue stems from the myofibromatous metaplasia of endometrial stromal cells.[12] It is very difficult to differentiate APA and endometrioid adenocarcinoma by immunophenotyping. Longacre et al suggested that if the lesions of APA exhibit markedly complex glands and severe architectural complexity, these APAs should be designated as “APA of low malignant potential (APA-LMP).”[5] However, Wang et al proposed that the definition of APA-LMP was too obscure, and not revealing the malignancy nature of lesions directly[13]; and it is difficult for the clinicians to master the diagnosis of APA-LMP in practice, and therefore delayed the treatment. There were several APA-LMP cases reported to have myometrial invasion in the uterine section specimens.[4,14] The precise mechanism underlying the development of adenocarcinoma in APA has yet to be understood. Therefore, further studies should be focused on diagnosis and differentiation of those APA lesions with potential of malignancy transformation and those coexisted with adenocarcinoma.

Many studies reported the possible relationship between hormone and APA. APA pathogenesis has been reported to be related with estrogen-related factors.[15–17] Also, there were studies reporting the possible relation between APA with obesity, prolonged estrogenic stimulation, and hormone replacement therapy for Turner syndrome and infertility.[5,15–17] Eight patients had diabetes, and 3 patients were infertile in our study. There were other cases to be detected with APA during infertility treatment. It is still unclear of the causal relationship between APA and infertility, and whether an endocrine environment that causes infertility also causes APA, or whether the 2 situations can coexist.[5]

Hysterectomy is the primary therapeutic choice for postmenopausal patients with APA. For patients who want to preserve their reproductive capacity, conservative treatments were recommended including endometrial curettage and polyectomy and close monitoring. We found that it is very difficult to get consents from the patients to perform hysterectomy if only with APA. Eight patients who were postmenopausal refused hysterectomy and only performed TCR. Therefore, conservative treatment in our clinic is very cautious for these APA patients. We performed hysteroscopic resection based on the techniques used by Di Spiezio Sardo et al.[16] The technique includes 4 stages: the removal of lesions of APA; the removal of endometria adjacent to APA; the removal of myometrium underling to APA; and multiple random endometrial biopsies. For the recurrent cases, the first choice was hysterectomy. However, 2 of the 3 patients recurred were nulliparous and TCR was redone. Nomura et al reported the long-term oncologic outcomes of fertility-preserving hormonal treatment with medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA) in patients with APA.[18] They found that MPA yields a high response rate in APA, and a favorable pregnancy rate can be obtained in younger patients. We therefore prescribed high-dose progesterone for the 2 recurrent patients.

APA is reported to have a high recurrence rate. Heatley et al reported a recurrence rate of 30.1% in postoperative cases, with risks of endometrial carcinoma at 8.8%.[2] The recurrence rate in our patients was lower at 7.0% than other reports,[2,6] and no endometrial carcinoma was found in the recurred patients. No guideline for treating APA is available yet because of limited number of cases. The possible reasons for low recurrence rate of this series of patients were as following: we performed hysteroscopic resection very strictly according to the suggested four-stage technique; the resection was very complete; it may be related to relatively short follow-up period. We grouped the 30 patients by TCR treatment into >3 years (n = 20) and ≤3 years (n = 12). One of the 3 recurrent cases fall into a “>3 years of follow-up period”; these results show recurrent cases may occur after a longer follow-up period. Therefore, close and careful follow-up combining imaging studies and biopsies are important for monitoring recurrence and malignancy transformation.

In conclusion, treatment of APA should be very cautious considering its malignancy potential. Hysterectomy is the primary therapeutic choice for postmenopausal patients with APA. Conservative treatment of APA with TCR is safe and efficient for those patients who required preserve reproductive capacity. Close follow-up with hysteroscopy and biopsy examinations are important for those patients with conservative treatment.

5. Author contributions

Conceptualization: Y. Zhu.

Data curation: B. Ma.

Methodology: B. Ma, Y. Li.

Resources: Y. Zhu, Y. Li.

Supervision: Y. Zhu.

Writing – original draft: Y. Li.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: APA = atypical polypoid adenomyoma, APA-LMP = APA of low malignant potential, MPA = medroxyprogesterone acetate, TCR = transcervical resection.

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- [1].Mazur MT. Atypical polypoid adenomyomas of the endometrium. Am J Surg Pathol 1981;5:473–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Heatley MK. Atypical polypoid adenomyoma: a systematic review of the English literature. Histopathology 2006;48:609–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Buenerd A, Dargent D, Scoazec JY, et al. Carcinomatous transformation of an atypical polypoid adenomyofibroma of the uterus. Ann Pathol 2003;23:63–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Zhang HK, Chen WD. Atypical polypoid adenomyomas progressed to endometrial endometrioid adenocarcinomas. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2012;286:707–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Longacre TA, Chung MH, Jensen DN, et al. Proposed criteria for the diagnosis of welldifferentiated endometrial carcinoma. A diagnostic test for myoinvasion. Am J Surg Pathol 1995;19:371–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Matsumoto T, Hiura M, Baba T, et al. Clinical management of atypical polypoid adenomyoma of the uterus. A clinicopathological review of 29 cases. Gynecol Oncol 2013;129:54–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Satoh H, Kai K, Yabe K, et al. Müllerian tumor (atypical polypoid adenomyoma) with sex-cord differentiation arising from the oviduct in an adolescent cynomolgusmonkey (Macaca fascicularis). Toxicol Pathol 2003;31:179–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Bakalianou K, Salakos N, Iavazzo C, et al. A case of endometrial carcinoma arising in a 36-year-old woman with uterine atypical polypoid adenomyoma (APA). Eur J Gynaecol Oncol 2008;29:298–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Fukuda M, Sakurai N, Yamamoto Y, et al. Case of atypical polypoid adenomyoma that possibly underwent a serial progression from endometrial hyperplasia to carcinoma. J Obstet Gynaecol Res 2011;37:468–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Nejković L, Pazin V, Filimonović D. Atypical polypoid adenomyoma mixed with endometrioid carcinoma: a case report. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol 2013;34:101–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Sugiyama T, Ohta S, Nishida T, et al. Two cases of endometrial adenocarcinoma arising from atypical polypoid adenomyoma. Gynecol Oncol 1998;71:141–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Soslow RA, Chung MH, Rouse RV, et al. Atypical polypoid adenomyofibroma (APA) versus well-differentiated endometrial carcinoma with prominent stromal matrix: an immunohistochemical study. Int J Gynecol Pathol 1996;15:209–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Wang J, Song X, Guo C, et al. Clinicopathological analysis of 14 cases of atypical poplypoid adenomyoma of endometrium with the emphasis on its cancerous transformation. Chin J Obstet Gynecol 2014;49:659–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Hui YZ, Shen DH. APA of low malignant potential: a case report. Zhonghua Bing Li Za Zhi 2002;31:88–9. [Google Scholar]

- [15].Clement PB, Young RH. Atypical polypoid adenomyoma of the uterus associated with Turner's syndrome: a report of three cases, including a review of ‘estrogen-associated’ endometrial neoplasms and neoplasms associated with Turner's syndrome. Int J Gynecol Pathol 1987;6:104–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Di Spiezio, Sardo A, Mazzon I, et al. Hysteroscopic treatment of atypical polypoid adenomyoma diagnosed incidentally in a young infertile woman. Fertil Steril 2008;89:456.e9-e12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Wong AY, Chan KS, Lau WL, et al. Pregnancy outcome of a patient with atypical polypoid adenomyoma. Fertil Steril 2007;88:1438.e7-e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Nomura H, Sugiyama Y, Tanigawa T, et al. Long-term outcomes of fertility-sparing treatment of atypical polypoid adenomyoma with medroxyprogesterone acetate. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2016;293:177–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]