Abstract

Rationale:

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a chronic inflammatory condition characterized by recurrent swollen, deep, and painful abscesses. Several autoimmune conditions have been shown to be associated with HS including inflammatory bowel disease and spondyloarthropathies.

Patient concerns:

40-year-old female with systemic lupus erythematous (SLE) presented with recurrent abscesses and nodules on her extremities.

Diagnosis:

Early considerations related the described dermatologic findings to the dermatologic manifestations of SLE, however findings from lesion biopsy were suggestive of HS.

Interventions:

Prednisone and antibiotic therapy with clindamycin were started. Subsequently upon discharge, the patient was also treated with rifampicin and azathioprine.

Outcome:

In this communication, we demonstrate a case of HS in a patient with SLE that significantly improved under antibiotic and immunosuppressant therapy.

Lessons:

HS can coexist in patients with SLE. Evidence pertinent to the etiology of HS and its association with other autoimmune conditions implies a possible denominator in the disease etiopathogenesis. Increased awareness of the co-occurrence of the two conditions calls for increased efforts to devise better treatment modalities.

Keywords: autoimmune disorders, hidradenitis suppurativa, systemic lupus erythematosus

1. Introduction

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a chronic inflammatory skin condition characterized by recurrent bouts of deep, swollen, painful abscesses, on body areas characterized by apocrine sweat glands abundance.[1] Involved areas most commonly include axillae, groin, perineum, buttocks, and the inframamillary regions in women.[2] Frequently, the disease presents bilaterally with one site being more affected than the other.[3] Initial symptoms include pain, decreased mobility of the involved areas, strictures, and malodorous drainage.[4]

The pathophysiology of the chronic inflammation accompanying HS remains to be elucidated. The current paradigm underscores the integral role of follicular occlusion from hyperkeratosis and hyperplasia of the follicular epithelium at the level of the infundibulum.[5] This subsequently results in dilation and eventual rupture of the hair follicle followed by infection, accumulation of cellular debris, and painful inflammation of the surrounding structures.[6]

The prevalence of HS in the general population is variable depending on myriad of epidemiological studies ranging from 0.03% of the general population in Mali to 4.1% in Denmark.[7,8] HS has a female predilection, and is more prevalent among subjects in the third decade of their life. However, various cases were reported at extremities of age with the earliest reported age of onset of 6 years.[9–11]

Autoimmune diseases have been associated with HS. In inflammatory bowel diseases (IBDs), HS have been demonstrated to occur nine times more common than the general population.[1] Additional rheumatologic disorders have been associated with HS for instance spondyloarthropathies among others.[12] The presence of significant overlap hints towards a possible pathophysiologic link and points toward the possible exposure to auto-antigens.

2. Case description

Our case is of a 40-year-old female patient from Nazareth, Israel. She is married with 2 children, and works as a teacher in a local school. Seventeen years ago, the patient was diagnosed with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), which manifested with malar rash, photosensitivity, polyarthritis, hemolytic anemia, and positive serologic markers, including antidouble-stranded DNA (ds-DNA) and antinuclear antibody (ANA). SLE was diagnosed according to revised diagnostic criteria set by Tan et al[13] in 1982. The course of her disease was complicated by non-provoked deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and five cases of spontaneous abortion raising the possibility for antiphospholipids syndrome (APS) which was later confirmed by positive serologic testing for lupus anticoagulant. Subsequently she developed lupus nephritis which was managed by immunosuppressive agents and prednisone. Currently, she is maintained in a stable clinical status by hydroxycholoroquine.

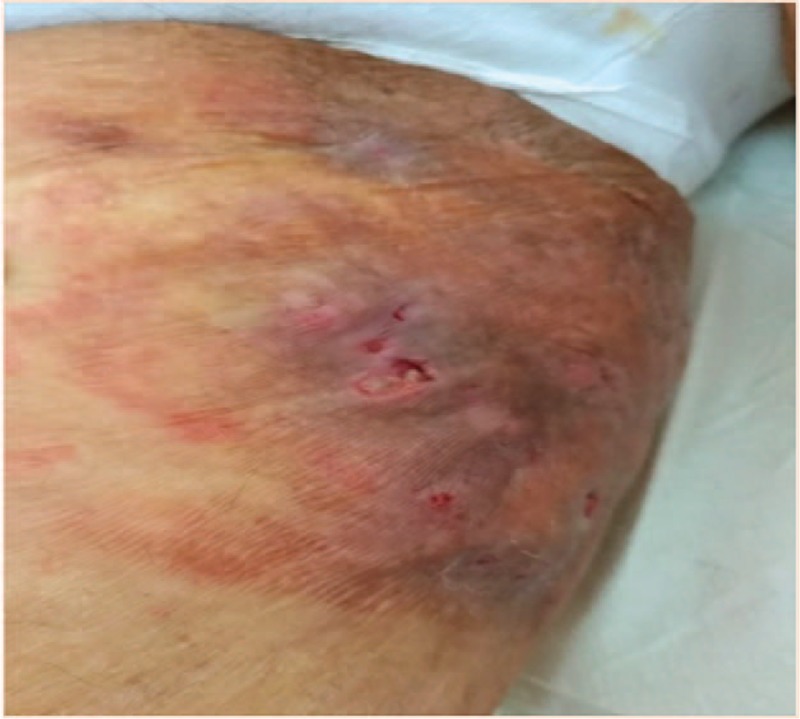

During her initial presentation, physical examination revealed multiple draining cysts and abscesses on her upper extremities and torso which were originally assumed to be a part of the cutaneous spectrum of SLE. On physical examination, nodules were predominantly located in the axilla and upper extremities (Figs. 1–3). Subsequently, similar nodules and cysts appeared in the groin, suprapubic area, and hips. The nodules were purplish in color, and painful to touch. In various regions, confluent lesions and pus secreting sinuses were noted. Furthermore, upon inspection of the abdomen scars were revealed along the torso. The remainder of the physical examination was interpreted as normal.

Figure 1.

Axillary findings: showing characteristic scars and sinuses.

Figure 3.

Two lesions located on the back of the arm.

Figure 2.

Forearm: presence of abscesses and sinuses.

On her complete blood count, hemoglobin level was 8.6 mg/dL. In contrast, leukocyte count approached 11,200/ μL with a neutrophil predominance serum creatinine, liver function, and electrolyte levels were all within normal range.

Upon her hospitalization for further management, a more thorough clinical history and radiographic evaluation was performed. In her past medical history, the patient suffered from dermal abscesses and nodules that were previously treated with drainage and oral antibiotics however, lacking sufficient response.

Of note, the abscesses and nodules usually appeared on the scalp, axilla, and groin regions with a tendency to exacerbate during hot humid weather. These intriguing recurrent findings led our group to seek a cause for her recurrent condition. Biopsy and cultures of several lesions were performed. While under investigation the patient was treated with intravenous clindamycin and prednisone, which led to a significant lesion regression. The patient was then tapered off steroids and discharged with recommendations to continue treatment on an outpatient basis with oral clindamycin, rifampin, and azathioprine.

Several days following her discharge, the biopsy findings raised suspicion for a diagnosis of HS which was confirmed upon consultation with the dermatologic department. Under the mentioned treatment regimen, the patient maintained a significant reduction of her HS lesions without any detectable adverse reactions.

3. Discussion

Our case provides a link between two separate entities, SLE and HS. Several other autoimmune disorders have been shown to be associated with HS; however, there is scarcity of evidence that suggests a concurrence of SLE and HS. In the current medical literature, one case series presented two patients with HS and SLE and in another case report a patient with concurrent pyoderma gangrenosum, HS, and SLE was presented.[14,15]

There are many theories which attempt to explain the development of autoimmune disorders in patients with HS. It has been shown that Crohn disease and pyoderma gangrenosum were related to HS.[16,17] Treatment for Crohn's with anti-TNF-alpha in patients with HS has been shown to reduce the severity of HS thus suggesting a common pathway.[18] Ustekinumab is an IL-12/23 blocker which was demonstrated to lead to an improvement of HS symptoms[19] indicating a role of IL-12 and IL-23 cytokines may play a role in disease pathogenesis. Many other cytokines have been studied and implicated in the development of HS including for instance TNF-alpha, IL-1 beta, IL-10, IL-17, IL-23, IL-12, IL-22, IL-20, IL-6, and IFN-gamma.[20]

The primary challenge in our case involved the choice of appropriate treatment modality. While several therapies previously discussed remain under investigation, adjunctive treatment with TNF-alpha inhibitor has been shown to be beneficial in HS cases not responding to standard antibiotic treatment.[21] Historically, the use of TNF-alpha inhibitors in patients with SLE have been contraindicated due to the potential drug induced lupus development.[22] More recent research revealed that using TNF-alpha inhibitors, may not be as detrimental as once thought in patients with SLE.[23] In a published case-series on HS, two patients with both HS and SLE were treated with adalimumab, in one case it was well tolerated, whereas the other patient had transient arthritis.[15] TNF-alpha induced autoantibodies majorly included innocuous IgM subtype. Studies revealed that injurious IgG subtype occurred only in around 0.5% to 1% of patients treated with TNF-alpha inhibitors.[22] It is important to note that our patient's history was significant for lupus nephritis, a factor which adds an additional potential side effect of TNF-alpha inhibitor. Novel HS therapies combining ustekinumab with other agents provide a key in the treatment of patients with both HS and SLE. There have been successful treatments of HS with its use[12] and reports of successful treatment of cutaneous SLE with psoriasis.[24]

It is our goal to raise awareness to the concurrence of the two conditions and to discuss options for treatment. Emerging evidence pertinent to the etiology of HS and its association with other autoimmune conditions implies a possible denominator in the disease etiopathogenesis and its possible relationship with SLE. Further research is required to better delineate the governing relationship between both disease entities and guide treatment options for these patients

4. Author contributions

Conceptualization: K. Sharif, M. Adawi.

Writing – original draft: C.B. Dvid, K. Sharif.

Writing – review & editing: N.L. Bragazzi, A. Watad, A. Whitby, H. Amital.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: ANA = antinuclear antibody, APS = anti-phospholipids syndrome, dsDNA = anti-double-stranded DNA, DVT = deep vein thrombosis, HS = hidradenitis suppurativa, IBD = inflammatory bowel diseases, SLE = systemic lupus erythematosus.

CBD and NLB contributed equally in the study.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- [1].Jemec GBE. Hidradenitis suppurativa. N Eng J Med 2012;366:158–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Ingram JR. Hidradenitis suppurativa: an update. Clin Med 2016;16:70–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Alikhan A, Lynch PJ, Eisen DB. Hidradenitis suppurativa: a comprehensive review. J Am Acad Dermatol 2009;60:539–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Kagan RJ, Yakuboff KP, Warner P, et al. Surgical treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa: a 10-year experience. Surgery 2005;138:734–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Sellheyer K, Krahl D. What causes acne inversa (or hidradenitis suppurativa)? The debate continues. J Cutan Pathol 2008;35:701–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Prens E, Deckers I. Pathophysiology of hidradenitis suppurativa: An update. J Am Acad Dermatol 2015;73:S8–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Jemec GBE, Heidenheim M, Nielsen NH. The prevalence of hidradenitis suppurativa and its potential precursor lesions. J Am Acad Dermatol 1996;35:191–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Mahé A, Cissé IA, Faye O, et al. Skin diseases in Bamako (Mali). Int J Dermatol 1998;37:673–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Lee EY, Alhusayen R, Lansang P, et al. What is hidradenitis suppurativa? Can Fam Physician 2017;63:114–20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Nazary M, van der Zee HH, Prens EP, et al. Pathogenesis and pharmacotherapy of Hidradenitis suppurativa. Eur J Pharmacol 2011;672:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Randhawa HK, Hamilton J, Pope E. Finasteride for the treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa in children and adolescents. JAMA Dermatol 2013;149:732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].De Souza A. Successful treatment of subacute lupus erythematosus with ustekinumab. Arch Dermatol 2011;147:896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Tan EM, Cohen AS, Fries JF, et al. The 1982 revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 1982;25:1271–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Scheinfeld N. Diseases associated with hidranitis suppurativa: part 2 of a series on hidradenitis. Dermatol Online J 2013;19:18558. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Blanco R, Martínez-Taboada VM, Villa I, et al. Long-term successful adalimumab therapy in severe hidradenitis suppurativa. Arch Dermatol 2009;145: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Hsiao JL, Antaya RJ, Berger T, et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa and concomitant pyoderma gangrenosum. Arch Dermatol 2010;146: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].van der Zee HH, van der Woude CJ, Florencia EF, et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa and inflammatory bowel disease: are they associated? Results of a pilot study. Br J Dermatol 2010;162:195–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Martínez F, Nos P, Benlloch S, et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa and Crohn's disease: response to treatment with infliximab. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2001;7:323–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Blok JL, Li K, Brodmerkel C, et al. Ustekinumab in hidradenitis suppurativa: clinical results and a search for potential biomarkers in serum. Br J Dermatol 2016;174:839–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Kelly G, Sweeney CM, Tobin A-M, et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa: the role of immune dysregulation. Int J Dermatol 2014;53:1186–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Zouboulis CC, Desai N, Emtestam L, et al. European S1 guideline for the treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa/acne inversa. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2015;29:619–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Charles PJ, Smeenk RJT, De Jong J, et al. Assessment of antibodies to double-stranded DNA induced in rheumatoid arthritis patients following treatment with infliximab, a monoclonal antibody to tumor necrosis factor: findings in open-label and randomized placebo-controlled trials. Arthritis Rheum 2000;43:2383–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Aringer M, Smolen JS. Therapeutic blockade of TNF in patients with SLE: promising or crazy? Autoimmun Rev 2012;11:321–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Winchester D, Duffin KC, Hansen C. Response to ustekinumab in a patient with both severe psoriasis and hypertrophic cutaneous lupus. Lupus 2012;21:1007–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]