Abstract

Rationale:

Mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia, a common cause of community-acquired pneumonia in children, is rarely complicated with acute cerebral infarction.

Patient concerns:

We present a 7-year-old boy with severe M pneumoniae pneumonia who developed impaired consciousness, aphasia, and reduced limb muscle power 7 days postadmission.

Diagnoses:

Mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia with concomitant acute cerebral infarction.

Interventions:

The patient recovered with aggressive antibiotic therapy, antiinflammation therapy with methylprednisolone, and gamma immunoglobulin and anticoagulation therapy with aspirin and low molecular weight heparin along with rehabilitation training.

Outcomes:

At 8 days postadmission, his consciousness was improved and at the 6-month follow-up visit, his muscle power of bilateral upper and lower limbs was normal except still poor right handgrip power.

Lessons:

Stroke or cerebral infarction should be considered and promptly managed in rare cases of M pneumoniae pneumonia with neurologic manifestations.

Keywords: cerebral infarction, diagnosis, pneumonia, stroke, therapy

1. Introduction

Mycoplasma pneumoniae is a common cause of community-acquired pneumonia in children and M pneumoniae infection accounts for approximately 20% of pediatric pneumonia patients requiring hospitalization.[1,2]M pneumoniae infection has been reported to cause various neurological complications including aseptic meningitis, transverse myelitis, cerebellar ataxia, Guillain–Barré syndrome,[3] and encephalopathy,[4] which is considered to be an immune-mediated response to injury. Ischemic stroke is very uncommon in children with a reported annual incidence rate of only 0.63 per 100,000 population in children under 14 years of age.[5] The estimated incidence of pediatric stroke between 1998 and 2001 was 2.1 cases per 100,000 children-years among children <15 years of age in Hong Kong.[6] Severe Mycoplasma pneumonia with cerebral infarction is clinically rare with a high morbidity and mortality. Liu et al reported[7] a clinical series of 65 pediatric cases of ischemic stroke and only 1 child had M pneumoniae infection-associated ischemic stroke. In the current paper, we report a case of severe M pneumoniae pneumonia with concomitant cerebral infarction in a 7-year-old boy. The patient successfully recovered after intensive therapies including treatment with antibiotics, inflammation control with methylprednisolone, anticoagulation therapy with aspirin and heparin, and active rehabilitation training.

2. Case report

A 7-year-old body was admitted on November 25, 2016 because of fever and cough for 6 days. On November 19, 2016, the boy started having fever for no apparent reason with the highest body temperature at 39.7 °C. He also had irritative coughs, which were worsened at late night and early morning. The patient did not complain of other symptoms including respiration difficulties, headache, vomiting, and limited movements (right upper limb muscle power, grade 1; right lower extremity muscle power, grade 1; left upper limb muscle power, grade 3; and left lower extremity muscle power, grade 3). Three days before admission, he received cefdinir (50 mg, twice daily) for 2 days, oral azithromycin (0.2 g/day), and unknown intravenous antibiotics at a local hospital.

His history was unremarkable, with no previous contact with infectious disease. He received all vaccinations as scheduled.

On admission, the boy was mentally oriented. His temperature was 37.0 °C, pulse 110/min, and respiration 30/min. The pharynx was congested, and bilateral tonsils were mildly swollen but with no exudation. The lower left lung had diminished vocal fremitus and was dull on percussion, and rales were heard. Neurological examination was unremarkable. There was also no other remarkable abnormality.

Laboratory examinations, including routine blood chemistry and blood count, and C-reactive protein, revealed no abnormality. Chest CT scan revealed left lung solidification with atelectasis of the left upper lobe and left hydrothorax (Fig. 1). Serum M pneumoniae IgM was positive (titer 1:640). Pleural fluid was aspirated and was clear and the protein content in the pleural fluid (37,472.0 mg/L) and LDH content (2340 units/L) in the pleural fluid indicated exudates. The M pneumoniae DNA content in the pleural effusion was 1.0 × 104 copies/mL. A diagnosis of severe M pneumoniae pneumonia was made.

Figure 1.

Chest computed tomography (CT) scan of a 7-year-old boy with Mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia complicated with cerebral infarction reveals solidification of the left lung with atelectasis of the left upper lobe and left pleural effusion.

Considering the antibiotics resistance spectrum of Streptococcus pneumoniae in the region and according to the China Community Acquired Pneumonia (CAP) Treatment Guideline (2013), the boy was given meropenem (20 mg/kg, 3 times daily) and azithromycin (10 mg/kg, once daily). Fever still persisted at 48 hours postadmission and the erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) was 34 mm/hour (normal reference, 0–20 mm/hour), C-reactive protein 138 mg/L (normal reference, 0–8 mg/L), and LDH 720 units/L (normal reference, 120–300 units/L). Methylprednisolone was given intravenously (1.5 mg/kg, twice daily). Temperature was at 39.7 °C. The adenosine deaminase (ADA) content in pleural effusion was 66.1 units/L on December 26, 2016 and 59.6 units/L on December 28, 2016. Given that the ADA content was above the threshold value for tuberculosis (45 units/L) and the region was endemic for tuberculosis, isoniazid and rifampin (10 mg/kg.d, once daily at bedtime) were given prophylactically. Bronchoscopy revealed massive cordlike plugs in the bronchial cavity of the anterior segment of the left upper lobe, the lingua and the posterior basal segment of the left lower lobe (Fig. 2). Pathology confirmed plastic bronchitis type 1 (Fig. 3).

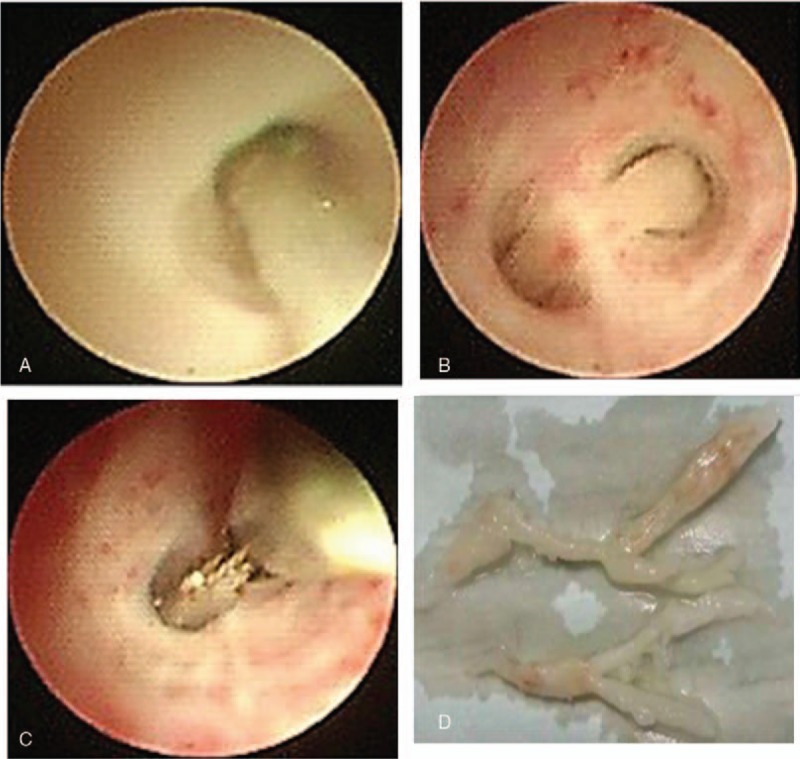

Figure 2.

Bronchoscopy reveals massive cordlike plugs in the bronchial cavity of the anterior segment of the left upper lobe (A), the lingua (B), and the posterior basal segment of the left lower lobe (C). (D) Cords removed during bronchoscopy showing a branching pattern. The longer cord is 2.5 cm with a diameter of 0.4 and the shorter one is 1.2 cm with a diameter of 0.2.

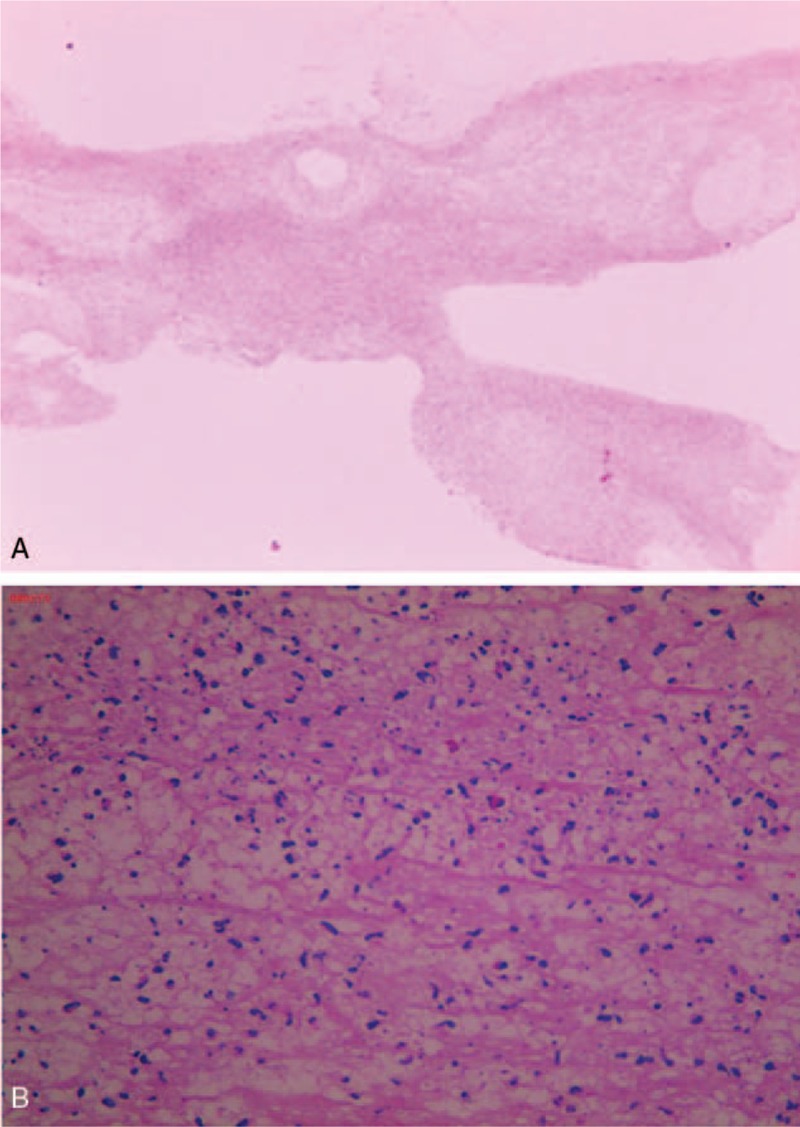

Figure 3.

Pathologic examination of bronchoalveolar lavage fluid shows type 1 plastic bronchitis. Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining. Magnification, 10× (A) and 40× (B).

At day 7 after admission, the patient showed impaired consciousness, aphasia, flattened left nasolabial fold, and left deviation of the protruded tongue. The muscle strength of both the right upper and lower limb was grade 1, and that of both the left upper and lower limb was grade 3. Magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) failed to visualize the left internal carotid artery, the middle cerebral artery (MCA) and its distal branches (Fig. 4A). MRI DWI demonstrated hyperintensity in the left frontoinsular cortex, involving the internal capsule and basal ganglia (Fig. 4B). Cerebral infarction was considered. Severe M pneumoniae pneumonia complicated with cerebral infarction was considered.

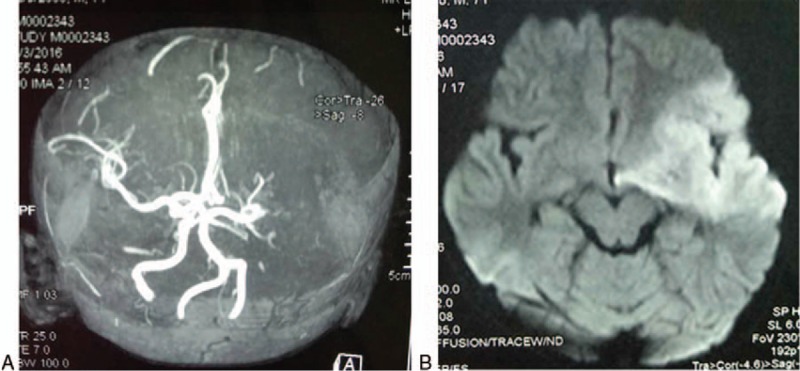

Figure 4.

MRA fails to visualize the left internal carotid artery, the MCA, and its distal branches, suggesting the presence of cerebral infarction (A). MRI DWI demonstrates hyperintensity in the left frontoinsular cortex, involving the internal capsule and basal ganglia (B). MCA = middle cerebral artery, MRA = magnetic resonance angiography.

Coagulation studies revealed increased fibrin D-dimer level (10.4 mg/L; normal reference values, 0–0.3 mg/L). Enteric coated aspirin (4 mg/kg body weight, 3 times per day), low molecular weight heparin calcium (80 IU/kg body weight, once daily), and furosemide and mannitol were administered to lower intracranial pressure and low molecular weight dextran for symptomatic treatment. Methylprednisolone was adjusted to 2 mg/kg body weight, 3 times daily and tapered over 2 weeks and gamma immunoglobulin was given on December 30, 2016 at 1 g/kg body weight, once daily for 2 days. At 8 days postadmission, his body temperature returned to normal, and his consciousness was improved, but the patient still felt drowsy. At 2 weeks postadmission, his fibrin D-dimer level decreased to 1.0 mg/L and the boy spoke, though indistinctly, and had longer wake time. At 1 month, the boy walked with assistance, but still uttered indistinctly. His left upper and lower limb muscle power was normal and the right upper and lower limb muscle power was grade 3. He was discharged from the hospital and prescribed with aspirin (75 mg, once daily). The patient was followed up for 6 months. At the 6-month follow-up visit, the muscle power of bilateral upper and lower limbs was normal except still poor right handgrip power. MRA indicates improved collateral circulation in the patient. Blood chemistries and platelet counts were normal, and aspirin was discontinued.

3. Discussion

M pneumoniae pneumonia is a common cause of community acquired pneumonia in children, with a seroprevalence rate of 10 to 30%.[8] Most infections by M pneumoniae are asymptomatic and self-limited, but may exhibit a myriad of symptoms and signs. In rare and severe cases, M pneumoniae infection may extend beyond the lungs, with the central nervous system a common site of extrapulmonary manifestations of M pneumoniae infection, which are seen in 1.0% to 4.8% of M pneumoniae infections.[9,10] Cerebral infarction is a rare extrapulmonary manifestation of M pneumoniae infection and only anecdotal cases have been reported. Using the census data in Hong Kong, Chung and Wong identified 94 children with stroke among children <15 years of age in Hong Kong from 1998 to 2001, and M pneumoniae infection was not reported to be a cause of pediatric stroke in the patients.[6] In a clinical series of 65 pediatric cases of ischemic stroke from China, only 1 child had M pneumoniae infection-associated ischemic stroke.[7] The current case initially showed manifestations of M pneumoniae pneumonia and despite aggressive antibiotic therapy and antiinflammatory therapy, the patient failed to respond. The onset of neurologic symptoms and MRA findings strongly indicated the development of cerebral infarction in the patient.

The mechanisms underlying M pneumoniae infection-associated cerebral infarction remain unelucidated. It has been speculated that M pneumoniae may disrupt the integrity of the vascular endothelium and upset the equilibrium between coagulation and anticoagulation by eliciting an inflammatory response, which may lead to hypercoagulation and thrombosis.[11] Direct invasion by M pneumoniae, neurotoxin production, immune-mediated mechanisms, and cytokine production have also been implicated.[12] Our patient had normal coagulation, but showed elevated fibrin D-dimer levels, suggesting a hypercoagulable state. Elevated fibrinogen and fibrin D-dimer levels were also reported in an 11-year old girl[13] and a 5-year old girl[14] with M pneumoniae pneumonia complicated with occlusion of the MCA (Table 1). Gu et al[15] reported a series of 6 pediatric cases of M pneumoniae pneumonia, including one case complicated with occlusion of the right MCA and cerebral infarction and one case with occlusion of the basilar artery and posterior cerebral artery and brain infarction. Four of these patients had elevated D-dimer levels. Anticoagulation therapy with aspirin for 6 months and low molecular weight heparin calcium reduced fibrin D-dimer levels to 1.0 mg/L at day 4 postinfarction. Thrombolytic therapy is considered the optimal modality for acute ischemic stroke in adults; however, the optimal approach for managing pediatric stroke remains elusive. Gu et al treated 2 children with cerebral infarction with thrombolytic therapy; one died of brain herniation while the other lost consciousness.[15] The American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines for Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis does not recommend thrombolytic therapy for unimportant minor brain infarcts.[16] In our current case, no thrombolytic therapy was performed given the presence of severe pneumonia and poor tolerance of anesthesia and aspirin and lower molecular weight heparin were given instead.

Table 1.

Summary of reported pediatric cases of M pneumoniae pneumonia complicated with stroke or cerebral infarction.

We reviewed 20 pediatric cases of M pneumoniae pneumonia complicated with stroke or cerebral infarction. The MCA was involved in 13 (65.0%, 13/20) patients, the posterior cerebral artery (PCA) in 4 (20%, 4/20) patients, and the internal carotid artery (ICA) in 5 patients (25%, 5/20) (the ICA and MCA were involved in 2 patients). The predominance of MCA involvement is consistent with previous reports.[17,18] Anatomically, the M1 segment of the MCA begins at the terminal bifurcation of the ICA and ends at the genu, a right-angle bend in the artery as it courses over a small gyrus of the insular cortex, where it is predisposed to thrombosis or occlusion. The early signs of pediatric stroke or cerebral infarction may be subtle and escape notice and only when altered consciousness, hemiplegia, or other neurologic symptoms emerge, involvement of the central nervous system is suspected. MRI DWI, as performed in the current case, can detect brain lesions within 6 hours of onset of stroke and is capable of distinguishing new versus old infarct.

Treatment of M pneumoniae pneumonia complicated with stroke or cerebral infarction requires aggressive antibiotic therapy, anticoagulation therapy as well as antiinflammatory therapy. Symptomatic management like controlling elevated intracranial pressure and rehabilitation training is also important to recovery.

In conclusion, M pneumoniae pneumonia complicated with cerebral infarction in children is clinically rare, and early diagnosis and prompt treatment with multiple modalities are critical to a successful outcome.

Author contribution

Conceptualization: Yingxue Zou.

Data curation: Jia Zhai.

Investigation: Bing Huang.

Writing – original draft: Xingnan Jin.

Writing – review & editing: Jie Liu.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: MCA = middle cerebral artery, MRA = magnetic resonance angiography.

Ethical approval: Informed consent was obtained from the patient's parents in this study.

Funding/support: This study is supported by the key discipline project of Tianjin health and family planning commission (13KG125).

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- [1].Rogozinski LE, Alverson BK, Biondi EA. Diagnosis and treatment of Mycoplasma pneumoniae in children. Minerva Pediatr 2017;69:156–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Waites KB, Talkington DF. Mycoplasma pneumoniae and its role as a human pathogen. Clin Microbiol Rev 2004;17:697–728. Table of contents. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Meyer Sauteur PM, et al. Severe childhood Guillain-Barre syndrome associated with Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection: a case series. J Peripher Nerv Syst 2015;20:72–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Candler PM, Dale RC. Three cases of central nervous system complications associated with Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Pediatr Neurol 2004;31:133–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Schoenberg BS, Mellinger JF, Schoenberg DG. Cerebrovascular disease in infants and children: a study of incidence, clinical features, and survival. Neurology 1978;28:763–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Chung B, Wong V. Pediatric stroke among Hong Kong Chinese subjects. Pediatrics 2004;114:e206–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Liu P, et al. Clinical characteristics and etiology analysis of children with ischemic stroke. J Appl Clin Pediatr 2008;23:1891–3. [Google Scholar]

- [8].Li S, et al. Two case reports: whole genome sequencing of two clinical macrolide-resistant Mycoplasma pneumoniae isolates with different responses to azithromycin. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95:e4963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Kishaba T. Community-acquired pneumonia caused by Mycoplasma pneumoniae: how physical and radiological examination contribute to successful diagnosis. Front Med (Lausanne) 2016;3:28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Wu LX. Complications of pneumonitis pneumoniae pneumonia. Chin J Appl Clin Pediatrics 2013;28:1210–1. [Google Scholar]

- [11].Kalicki B, et al. Absence of inferior vena cava in 14-year old boy associated with deep venous thrombosis and positive Mycoplasma pneumoniae serum antibodies – a case report. BMC Pediatr 2015;15:40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Flateau C, et al. Aortic thrombus and multiple embolisms during a Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection. Infection 2013;41:867–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Fu M, et al. Middle cerebral artery occlusion after recent Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection. J Neurol Sci 1998;157:113–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Kang B, et al. Complete occlusion of the right middle cerebral artery associated with Mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia. Korean J Pediatr 2016;59:149–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Gu HY, et al. Clinical analysis of 6 cases of Mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia complicated with embolism. Chin J Appl Clin Pediatrics 2016;31:288–91. [Google Scholar]

- [16].Guyatt GH, et al. Executive summary: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest 2012;141(2 Suppl):7S–47S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].li TH, et al. Analysis of one case of acute hemiplegia caused by Mycoplasma pneumoniae and review of the literatures of 12 cases. Chin J Pract Pediatrics 2013;210–3. [Google Scholar]

- [18].Yang FH, et al. Cerebral infarction associated with Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection in children. Chin J Appl Clin Pediatrics 2012;27:1869–73. [Google Scholar]

- [19].Garcia Tirado A, et al. Cortical blindness in a child secondary to Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 2017;26:e12–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Garcia AV, et al. Severe Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection requiring extracorporeal membrane oxygenation with concomitant ischemic stroke in a child. Pediatr Pulmonol 2013;48:98–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Kong M, et al. [Clinical characteristics of Mycoplasma pneumoniae-associated ischemic stroke in children, and a literature review]. Zhongguo Dang Dai ErKeZaZhi 2012;14:823–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Parker P, Puck J, Fernandez F. Cerebral infarction associated with Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Pediatrics 1981;67:373–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]