Abstract

The emergence of novel binding proteins or antibody mimetics capable of binding to ligand analytes in a manner analogous to that of the antigen–antibody interaction has spurred increased interest in the biotechnology and bioanalytical communities. The goal is to produce antibody mimetics designed to outperform antibodies with regard to binding affinities, cellular and tumor penetration, large-scale production, and temperature and pH stability. The generation of antibody mimetics with tailored characteristics involves the identification of a naturally occurring protein scaffold as a template that binds to a desired ligand. This scaffold is then engineered to create a superior binder by first creating a library that is then subjected to a series of selection steps. Antibody mimetics have been successfully used in the development of binding assays for the detection of analytes in biological samples, as well as in separation methods, cancer therapy, targeted drug delivery, and in vivo imaging. This review describes recent advances in the field of antibody mimetics and their applications in bioanalytical chemistry, specifically in diagnostics and other analytical methods.

Keywords: antibody mimetics, protein scaffolds, antibodies, molecular imaging, diagnostics, biosensors

INTRODUCTION

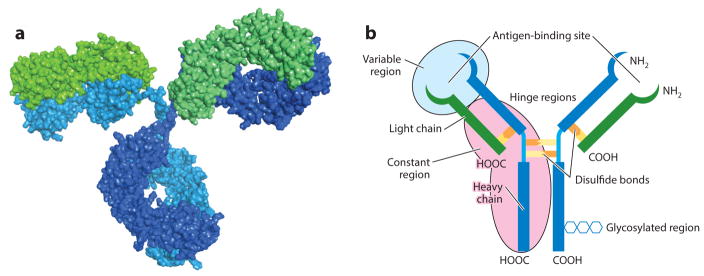

Antibodies are large Y-shaped glycoproteins that are produced by the humoral immune system to combat foreign compounds, i.e., antigens, that enter the body (1). They are generated by the immune cells and can be either polyclonal or monoclonal. Polyclonal antibodies are produced by several different immune cells and have an affinity toward the same antigen. However, their affinities are usually for different epitopes of the same antigen. In contrast, monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) are made using identical immune cells that are clones of a parent cell. Therefore, they have affinities for the same antigen and the same epitope. Antibodies are relatively large (~150 kDa) and consist of two identical heavy and light polypeptide chains that are connected to each other by disulfide bonds (Figure 1) (2). Their main physiological role is to bind and neutralize a very specific region of antigens that are often part of harmful pathogens such as bacteria and viruses (3). The mechanism of antibody–antigen binding, or more accurately, paratope–epitope pairing, is specific and mimics that of a lock and key. The molecular forces involved in the antigen–epitope binding mainly consist of electrostatic forces, hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic interactions, and van der Waals forces; this leads to reversible binding with relative affinities that are dependent on antigen structure and composition. The extraordinary specificity of antibody binding, with affinities ranging from low nanomolar to picomolar values, allowed for their use in a number of analytical, bioengineering, and biomedical technologies. These affinities have found a myriad of applications in diverse fields and have been the focus of extensive literature reviews (4–6).

Figure 1.

(a) The X-ray crystal structure of an antibody. Heavy chains (constant fraction) and light chains (antigen-binding fraction) are shaded in blue/turquoise and green, respectively. (b) Schematic of an antibody with important regions highlighted.

The increased need for recognition molecules such as antibodies to enable technologies prompted their increased use in various applications. Scientists soon started to realize some shortcomings of these amazing binders and started drawing attention to the specific requirements that antibodies do not fulfill. For example, despite their specificity, antibodies can have serious cross-reactivity when two or more antigens are similar in chemical or molecular composition or structure. Furthermore, to cut research costs, antibodies are sometimes used as unpurified sera, which compounds the cross-reactivity issue. Antibodies also have a relatively large size, with four polypeptide chains arranged in a conjoined mirror-image structure held together at the glycosylated heavy chains by several crucial disulfide bridges. These unique structural features limit the postrecombination antibody expression to eukaryotic cell lines in which the proper folding, cysteine oxidation, and posttranslational glycosylation can be achieved (7). Eukaryotic host cell lines also require genomic incorporation of the antibody sequence for long-term expression as well as extensive optimization for manufacturing-level output, leading to a very labor intensive and expensive fermentation when compared to bacteria (8). In addition, the large size of antibodies limits their use in a number of applications where the recognition molecule needs to be genetically or chemically modified, or incorporated into biomaterials, drug delivery systems, or devices. Another challenge that antibodies present is their lack of thermal stability and performance in extreme environments. These drawbacks compromise the length of their shelf lives and limit their storage and transport options as well as the environment and location of their use. For example, it is challenging to use antibodies in remote locations and in developing countries where access to continuous power supply and refrigeration is still difficult. All of these drawbacks have limited the universal use of antibodies and led scientists to search for antibody mimetics that can overcome these inherent limitations of antibodies.

In the search for a smaller-sized antibody that can penetrate tissues, is easier to produce, and is more stable, the first strategy involved truncation of the reading frame of a cloned immunoglobulin (Ig) gene. This enabled the production of only the antigen-binding fractions (Fabs) or single-chain variable fractions (scFvs) that are produced by connecting the VH and VL domains using a short peptide linker (9). ScFvs offer several advantages compared to full-length mAbs. They display improved pharmacokinetic properties and have better tissue penetration and rapid blood clearance (10). These scFvs can penetrate tumors more rapidly and efficiently than full-length antibodies and lack the constant fraction (Fc) region, which reduces their immunogenicity. More importantly, they can be cloned and expressed in bacterial cultures, making them easy to produce in large quantities inexpensively. Despite these advantages, scFvs have some drawbacks that need to be addressed. For example, they usually have a lower binding affinity than their parent antibodies due to their monovalent nature. In vivo scFvs have low retention on their targets, and their off rate is rapid. Their small size, advantageous in tissue penetration, is actually a disadvantage because it leads to a short half-life in serum, which limits the exposure of the tumor to the scFvs (11). Moreover, the length and structure of the peptide linker that connects the VH and VL domains play an important role in the oligomerization of the variable fractions because scFvs usually exhibit a concentration-dependent oligomerization (12). Although scFvs promise great value, the aforementioned disadvantages hinder their widespread use in the analytical and medical fields (13).

The serendipitous discovery of camelid heavy-chain antibodies was greeted with great enthusiasm in the field of antibody-based therapy and diagnostics (14). The camelid antibodies are part of the humoral immune response of camels and llamas and largely consist of heavy-chain antibodies. Also known as VHH or nanobodies, these unique antibodies have been extensively employed in therapy and diagnostics. These antibodies are smaller in size (~15 kDa), single domain, and highly soluble, which means they can be produced recombinantly. Due to their single-domain nature, nanobodies have several advantages over conventional polyclonal and monoclonal antibodies. The libraries generated using nanobodies usually retain their full functionalities. In addition, nanobodies can be engineered with common molecular biology techniques; they are stable toward temperature extremes, extremely soluble, and well expressed; they also penetrate tissues rapidly. Finally, because nanobodies are small, they can access and recognize hidden antigenic sites, such as an active site of an enzyme that may appear buried into the structure. This is also possible because nanobodies are capable of recognizing concave-shaped antigens (15). Unfortunately, nanobodies have the same disadvantages as full-length antibodies with regard to their inability to bind small antigens and peptides (16) and in terms of rapid clearing from the body, a disadvantage when they are employed for the treatment of infections or inflammations (17). Furthermore, nanobodies need to be engineered to improve their pharmacokinetic properties and reduce their immunogenicity.

ANTIBODY MIMETICS

Although various antibody types are standard in various applications, the aforementioned limitations of antibodies led scientists to search for alternative scaffolds that can mimic antibodies. Antibody mimetics are defined as molecules that can bind to antigens similar to antibodies; however, they are not generated by the immune system and have no structural relation to the antibodies. They are mostly unrelated protein scaffolds consisting of α-helices, β-sheets, or random coils that can bind to specific targets and could be designed to incorporate novel binding sites through common protein engineering strategies.

The necessity of harnessing an intact immune system for the production of unique antibody recognition domains led scientists to start investigating unrelated proteins that could be designed to incorporate novel binding sites through common protein engineering strategies. Among these techniques, site-directed or random mutagenesis in conjunction with selection techniques provided the most efficient route to produce novel binding proteins. These designer binding proteins known as antibody mimetics are engineered protein scaffolds that provide advantages over antibodies. The most important advantages are the extraordinary increase in production yield upon incorporation into microbial expression systems as well as the greater inherent stability associated with a less complex structure. These antibody mimetics can also be engineered to incorporate other desired properties, such as higher solubility, resistance to proteases, or stability toward higher temperatures and pH extremes. Characteristics of antibody mimetics versus antibodies are compared in Table 1. Antibody mimetics have become quite attractive for many research applications, especially those focused on therapeutic potential, but the infrastructure, high cost, and manpower involved in generating successful antibody mimetics with optimal characteristics limit their design and production to biotech and pharmaceutical companies that can afford to undertake such studies. Unfortunately, these companies often maintain tight control of the developed antibody mimetics and the intellectual property associated with the vast libraries generated during the selection and screening processes. This has limited researchers’ access to some of these antibody mimetics.

Table 1.

Comparison of antibody mimetics to antibodies

| Antibody mimetics | Antibodies |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

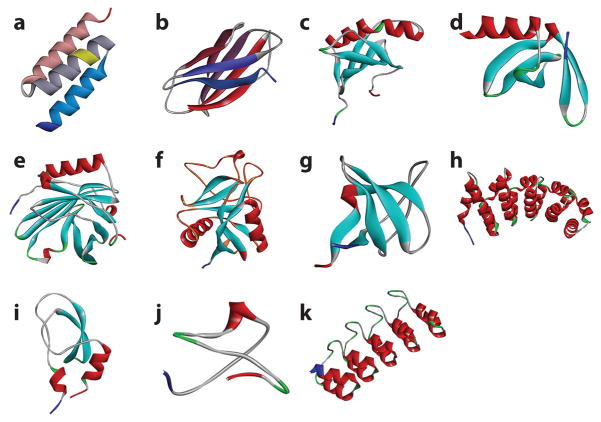

Table 2 lists the most common types of antibody mimetics, with their corresponding X-ray crystal structures shown in Figure 2. Most of these binding elements have been discussed extensively in the literature and are identified by the different protein scaffolds used as starting materials. As seen in Table 2, the number of patents referring to the production of these molecules far exceeds the number of publications describing their preparation and properties, indicating that most of these antibody mimetics were developed for commercial purposes and are not freely available to investigators. This is not surprising given that the main incentive for their development was (and remains) for use in therapeutics.

Table 2.

Types of antibody mimetics and the number of published papers up to 2016 [data from Chemical Abstracts Service (CASR )]

| Antibody mimetic | Total number of referencesa | Number of patents | Number of publications | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adnectins | 179 | 133 | 46 | 7, 18 |

| Affibodies | 734 | 249 | 485 | 19–21 |

| Affilins | 43 | 36 | 7 | 22–25 |

| Affimers | 75 | 7 | 68 | 26–28 |

| Affitins | 19 | 9 | 10 | 29–32 |

| Alphabodies | 16 | 14 | 2 | 33 |

| Anticalins | 245 | 180 | 65 | 34–36 |

| Aptamers | 1,791 | 852 | 939 | 37–39 |

| Armadillo repeat protein– | 575 | 96 | 479 | 40–42 |

| based scaffolds | ||||

| Atrimers | 105 | 80 | 25 | 43 |

| Avimers | 281 | 137 | 144 | 44 |

| DARPins | 231 | 105 | 126 | 45–47 |

| Fynomers | 29 | 22 | 7 | 25, 48, 49 |

| Knottins | 1,426 | 379 | 1,047 | 50–52 |

| Kunitz domain peptides | 102 | 54 | 48 | 53–55 |

| Monobodies | 159 | 62 | 97 | 56–59 |

| Nanofitins | 14 | 10 | 4 | 30, 60, 61 |

The sum of the number of patents and number of publications.

Figure 2.

X-Ray crystal structures of antibody mimetics. (a) An affibody molecule, with the hydroxylamine-susceptible asparagine-glycine residues highlighted in yellow (Protein Data Bank: 1LP1); (b) an adnectin molecule (Protein Data Bank: 3RZW); (c) an affimer molecule (Protein Data Bank: 1NB5); (d ) an affitin molecule (Protein Data Bank: 4CJ2); (e) an anticalin molecule (Protein Data Bank: 4GH7); ( f ) an atrimer molecule, with the flexible loops involved in binding colored in orange (Protein Data Bank: 1TN3); ( g) a fynomer molecule (Protein Data Bank: 1M27); (h) an armadillo repeat protein molecule (Protein Data Bank: 4DB9); (i ) a Kunitz domain inhibitor molecule (Protein Data Bank: 1ZR0); ( j) a knottin molecule (Protein Data Bank: 2IT7); (k) a designed ankyrin repeat protein molecule (Protein Data Bank: 2Q4J).

Protein Engineering Strategies for the Development of Antibody Mimetics

A typical scheme for the development of antibody mimetics is shown in Figure 3 (62–64). The design of a new antibody mimetic usually starts with selection of an appropriate scaffold that is suitable for incorporation of recognition moieties. The scaffold is a well-defined three-dimensional protein structure that is open to mutations and insertions. It must also have enough flexibility in its primary structure that the introduced modifications do not compromise its secondary structure and overall stability. In general, such scaffolds are aimed at improving the limitations of antibodies without compromising affinity and specificity. These new molecules must be small, preferentially thermostable, single-domain proteins without any disulfide bonds or glycosylation. Additionally, it is important to be able to express these proteins rapidly with correct folding in the cytoplasm of prokaryotic expression systems without aggregation or degradation (26, 65).

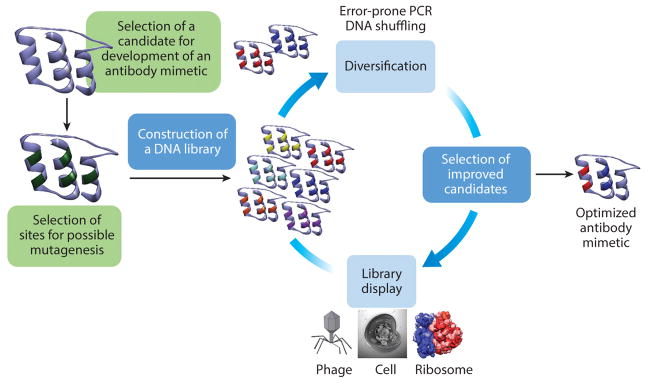

Figure 3.

Directed evolution cycle for isolating novel antibody mimetics. Once the parent binding moiety is decided and the sites have been identified for mutagenesis, a new library is built and displayed using one of the display techniques. The selected candidates are then matured via error-prone shuffling. This process is repeated until the desired binding protein is developed. Abbreviation: PCR, polymerase chain reaction.

After the selection of the appropriate scaffold, the library is designed by employing in silico methods and is constructed via molecular biology protocols. If the starting scaffold has an inherent biomolecular recognition element, the residues involved in this ligand binding are a good starting point for mutagenesis or other modifications. Identification of ligand binder candidates for the newly produced antibody mimetics is achieved by using X-ray crystallography data and molecular modeling. Once the possible candidates for mutagenesis are identified, mutant constructs and libraries of the antibody mimetics can be generated at the DNA level by employing either site-directed or random mutagenesis strategies. Once the library is designed and constructed, the translated protein scaffolds are screened for isolation of mutants with the desired properties. In a typical library of 1012 variants, a high-throughput screening method is required that typically involves a display technique to reduce the time involved in the screening process. The most commonly employed display systems include phage display, ribosome display, mRNA display, yeast display, and bacterial cell-surface display. Commercial kits for display methodologies are available and simple to use, facilitating their widespread use (66–69). After the directed evolution and selection steps, the identified variants of the desired characteristics undergo one or more iterations of selection to increase the diversity of the resulting library. Using this methodology, it is possible to obtain protein scaffolds with as high as femtomolar binding affinities (70).

Table 3 lists some antibody mimetics and their characteristics, such as binding affinities and melting temperatures. Typically, diversity is introduced into the libraries using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) in which error-prone PCR or DNA shuffling can rapidly introduce and expand sequence variants (71, 72). More exotic techniques for increasing diversity exist but are beyond the scope of this review. Interested readers are encouraged to consult References 73–75. Once antibody mimetics are produced, they can be modified further depending on the desired application. For example, antibody mimetics can be modified through genetic and chemical conjugation for introduction of reporters. They have shown low toxicity and immunogenicity and are thus well suited for both diagnostic and imaging applications. A drawback of antibody mimetics includes their labor-intensive and expensive production, which tends to limit their widespread use. This review focuses on the analytical applications of antibody mimetics and more specifically on their use in diagnostics and analysis tools.

Table 3.

Characteristics of selected antibody mimetics

| Scaffold | Parental protein | MW (kDa) | Kd | Temperature (°C) | Company | Ligands |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Affibodies | B-domain of SPA | ~6 | μM–pM | 42–71 | Affibody | Human IgA, Taq DNA polymerase, human apolipoprotein A-1, recombinant human factor VIII, EGFR, HER2, c-Jun, IL-6, TNF, VEGFR2 |

| Adnectins (monobodies) | 10Fn3 | ~10 | μM–pM | 37–73 | Bristol-Myers Squibb | VEGFR2, PCSK9, EGFR, IGF-1R, p19 subunit of IL-23, β-cyclodextrin, SFK |

| Affimers | Stefin A quadruple mutant- Tracy | ~11 | μM–nM | ~80 | Avacta Life Sciences | NS1 protein, CRP, PEDF, osteonectin, CDK2, AGR2 |

| Affitins (nanofitins) | Sac7d | ~7 | μM–sub- nM | Up to 90 | Affilogic | Human IgG, chicken egg lysozyme, secretin PulD, thermophilic CelD |

| Anticalins | Lipocalins | ~20 | Low nM | 53–73 | Pieris | Receptor tyrosine kinase MET, fluorescein derivatives, VEGF-A, CTLA-4, HGFR |

| Atrimers | C-type lectin | 60–70 | Sub-nM | 70–80 | Anaphore | IL-23, DR4 |

| Avimers | A-domain | 4 | Sub-nM | >80 | Amgen | IL-6, HGFR, BAFF |

| Fynomers | SH3 domain of Fyn kinase | 7 | Sub-nM | 70 | Covagen | TNF/IL-17A, HER2 |

| Armadillo repeat proteins | Armadillo domain | 39 | nM–pM | 80 | NA | NA |

| Kunitz domains | Serine protease inhibitor | 7 | nM–pM | 65 | Shire (Dyax) | Kallikrein, neutrophil elastase, plasmin |

| Knottins | Peptide | 3 | Sub-nM– nM | >100 | Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Elan Phar- maceuticals | Ion channels, AChR |

| DARPins | Ankyrin repeats | 14–21 | pM–nM | 66–89 | Molecular Partners, Allergan | VEGF-A, VEGF-A/PDGF-B, VEGF-A/HGF, HER2, EGFR, EpCAM |

Abbreviations: AChR, acetylcholine receptor; AGR2, anterior gradient 2; BAFF, B-cell activating factor; CDK2, cyclin-dependent protein kinase 2; CRP, C-reactive protein; CTLA-4, cytotoxic-T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4; DR4, death receptor 4; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; EpCAM, epithelial cell adhesion molecule; HER2, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2; HGFR, hepatocyte growth factor receptor; Ig, immunoglobulin; IGF-1R, insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor; IL, interleukin; MW, molecular weight; NA, not applicable; PCSK9, proprotein convertase subtilisin kexin-9; PDGF-B, platelet-derived growth factor B; PEDF, epithelium-derived factor; SFK, Src family kinase; SH3, Src-homology domain 3; SPA, staphylococcal protein A; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; VEGF-A, vascular endothelial growth factor A; VEGFR2, human vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2.

Affibody Molecules

Affibody molecules are one of the most important and widely used engineered protein scaffolds originating from the B-domain of staphylococcal protein A (SPA) discovered from Staphylococcus aureus, and it is different from most other scaffolds that are derived from human proteins (76). Since SPA was first discovered in 1984, researchers prepared affibody molecules that show effective binding to a wide range of proteins, including cell-surface receptors, interleukins, immunoglobulins, and enzymes (27, 77). The B-domain of SPA comprises 58 amino acids that rapidly fold into three α-helices, which can bind to the Fc portion of IgG (78). The asparagine–glycine bond that exists within the secondary structure (highlighted in yellow in Figure 2a) of the peptide is cleaved by hydroxylamine, resulting in the loss of the binding capability to its target ligand. To address this problem, Nilsson et al. (79) synthesized an engineered domain, Z-domain, with enhanced stability toward hydroxylamine by replacing the glycine residue with an alanine (77). Feldwisch et al. (80) have further optimized the affibody scaffold protein to improve the thermal and chemical stabilities by optimizing 11 amino acids present in the nonbinding sites of the Z-domain of SPA. Moreover, 13 positions on helices I and II that compose the binding surface were randomized to obtain high affinity and specificity binding with the affibody molecules’ corresponding ligands. Affibody molecules inherited most of the original SPA scaffold residues and the three α-helical structure from the Z-domain of SPA, while differing in 24 residues that help increase stability and create binding diversity (80). Thus, affibody molecules possess the structural stability and rapid folding of the parental protein, with enhanced chemical and thermal stabilities as well as expanded binding versatility.

Compared to antibodies, affibody proteins are smaller in size (only 6.0 kDa), allowing for enhanced tissue penetration. In addition, affibodies have shorter circulation times, higher solubility, and wider thermal stabilities (42–71°C), as well as comparable binding affinities and specificities with the dissociation constants in the micromolar to picomolar range (80, 81). Their small simple structure and fast folding rate result in quick and cost-efficient in vitro production through recombinant expression and solid-phase peptide synthesis (SPPS).This has led to the applications of affibodies in enzyme regulation, immunoassays, microarrays, bioseparations, in vivo imaging, and diagnostic and therapeutic applications (27, 82). For instance, affibody molecules have been incorporated into microarray systems as the capture reagents instead of antibodies to produce miniaturized high-throughput detection systems (83, 84). Renberg et al. (84) have site-specifically introduced active binding groups into affibody proteins to optimize the immobilization strategies on different microarray systems in a random or site-directed fashion, yielding microarrays with detection limits as low as 3 pM for human IgA and 30 pM for Taq DNA polymerase. Affibody proteins have also been used to establish sandwich-type two-site enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) to detect analytes in human serum, which avoids the cross-linking to human heterophilic antianimal Ig antibodies, thus decreasing the background and false-positive rates (85).

Affibodies have also found applications in affinity chromatography methods because of their robust structure and wide resistance to a range of pHs, both of which are desired properties for column regeneration and immobilization processes. Affibody-based columns can stand rigorous conditions, such as repeated cleaning (with 0.5 M NaOH) and regeneration cycles without the loss of affinity and purity, extending their service lives. Examples of such columns include the purification of Taq polymerase, human apolipoprotein A-1, and recombinant human factor VIII from Escherichia coli–derived cell lysates (79, 86).

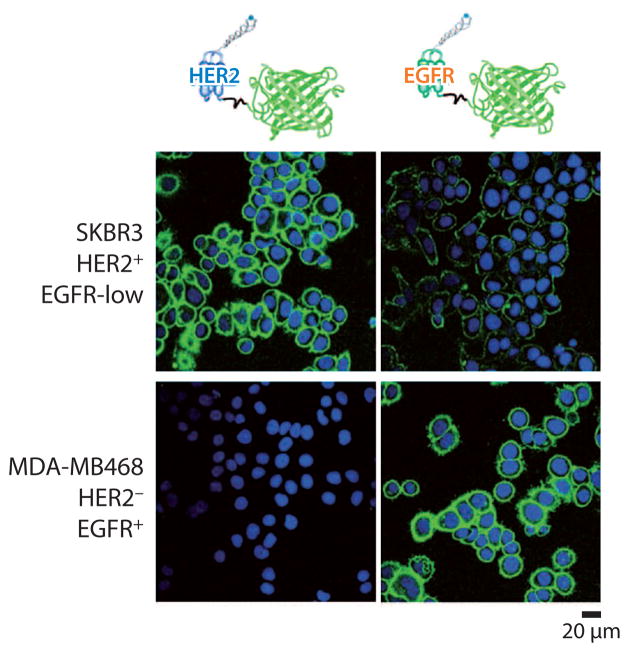

Additionally, affibodies can substitute antibodies in in vitro staining. Affibody proteins were conjugated with fluorescent labels both genetically (87) and chemically (88) for cell staining to image overexpressed cancer cell biomarkers with confocal microscopy. For instance, Lyakhov et al. (87) have designed novel staining reagents for affiprobes through the genetic conjugation of affibodies and fluorescent proteins. Protein constructs comprise an N-terminal His-tag, a targeting affibody specific to epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) or human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2), and a C-terminal fluorescent protein (mCherry) and enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) were expressed in E. coli and purified via affinity chromatography. These affiprobes were applied to stain EGFR-positive (MDA-MB468), HER2-positive (BT474), and double-positive (SKBR3) cells, as well as cells (MCF7) with low expression levels of both biomarkers (Figure 4), demonstrating the high affinities, specificities, and signal-to-noise ratios through flow cytometry and confocal microscopy. Additionally, Lundberg et al. (88) have chemically labeled affibody molecules with fluorescent probes for staining fixed cells. They chemically conjugated an affibody targeting to the oncogenic transcription factor c-Jun protein with the fluorescent probe Alexa 488 by employing well-established methods; they then used the fluorescent affibody conjugate to stain intracellular c-Jun in human malignant melanoma cells (C8161).

Figure 4.

The use of affiprobes to stain cells with different HER2 and EGFR phenotype. The images were taken by a confocal microscope. Adapted with permission from Reference 87. Copyright 2010, John Wiley & Sons. Abbreviations: EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; HER2, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2.

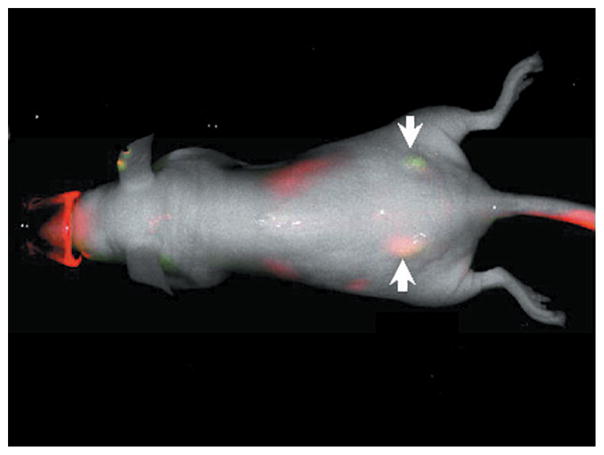

The most investigated and promising affibody molecules for in vivo imaging are the EGFR-and HER2-specific affibodies. These affibodies have been labeled with fluorophores, radiolabels, near-infrared (NIR) probes, and superparamagnetic iron oxide particles, which have assisted cancer diagnostics, tumor localization, and monitoring the efficacy of drugs (89–93). For example, Gong et al. (92) employed EGFR- and HER2-specific affibodies labeled with two different NIR fluorescent probes in in vivo imaging to distinguish between EGFR-overexpressing A431 and HER2-overexpressing SKOV3 tumors. They labeled the EGFR-specific affibody Eaff and the HER2-specific affibody Haff with the NIR fluorescent dyes IBDye800CW and DY-682, respectively, through a thiolmaleimide reaction. They injected both of the conjugates through the tail vein into mice that bore two tumors, A431 and SKOV3, on different sides of their bodies. The entire animal body was imaged by a cooled charge-coupled device camera one day after the injection, successfully distinguishing the two tumors by the emission of different colors (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

In vivo imaging of nude mice bearing tumors with fluorescence-labeled affibodies Eaff682 and Haff800. The EGFR-overexpressing A431 tumor is located on the left side, whereas the HER2-overexpressing SKOV3 tumor is located on the right side. Tumors are indicated by white arrows. Reprinted with permission from Reference 92. Copyright 2010, Elsevier. Abbreviations: EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; HER2, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2.

Adnectins (monobodies)

Adnectin is originally derived from the tenth extracellular domain of human fibronectin type III protein (10Fn3) (18). 10Fn3 contains 94 amino acids that fold into seven β-strands linked by six loops (94). This β-sandwich structure resembles the structure of the variable domain of an antibody, illustrating its potential to be used as an alternative to antibodies (Figure 2b). Among all six hypervariable loops in 10Fn3, three of them (BC, DE, and FG) adopt the structure of the complementary determining region (CDR) of the antibody. Randomization has been performed with these three CDR-like loops to create diversity and specificity (95). This led 10Fn3-based adnectin to possess comparable affinity and specificity to antibodies, although adnectin has a much simpler protein architecture (single domain without free cysteines and disulfide stabilization), thus favoring in vivo applications and in vitro recombinant expression.

To date, various adnectin molecules have been manufactured and investigated for binding to different ligand analytes such as human vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 (VEGFR2), proprotein convertase subtilisin kexin-9 (PCSK9), EGFR, the p19 subunit of interleukin (IL)-23, and β-cyclodextrin (18, 58, 96–98). For example, an Fn3 monobody fused with a cartilage oligomeric matrix protein (COMP) pentamerization domain increases the protein solubility during protein expression and also shows high affinity toward αvβ3 integrin (56). In a variety of diseases, kinases play a critical role in disease progression, and several monobodies have been generated to detect those disease-related kinases or inhibit their activity. Mann et al. (57) generated monobodies by yeast display techniques that are able to bind the common docking domain of the extracellular signal-regulated kinases and the extracellular signal-regulated kinase 2 (Erk2). This monobody can prevent the interaction between Erk2 and its activators, thereby inhibiting the activity of Erk2 and blocking the Erk2-mediated signal transduction.

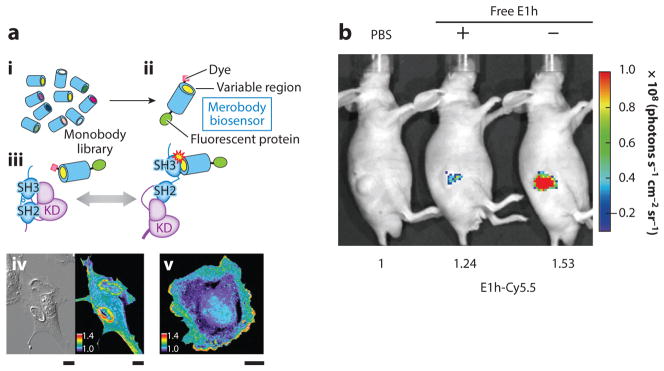

Src family kinases (SFKs) are highly expressed and activated in a variety of cancers and play an important role in cell movement and migration (99, 100). However, the dynamics of SFK activation along the cell edge have not been revealed, which impedes the understanding of their regulation functions. In response to this, Gulyani et al. (101) have designed an adnectin-based fluorescent probe that is sensitive enough to monitor the SFKs’ activation and distribution along the cell edge, as well as the correlation between the activation kinetics and the movement velocity. In this research, the activated SFK-specific adnectin named 1F11 was genetically fused to the C-terminus of a fluorescent protein, mCerulean. The fusion protein 1F11–mCerulean was further decorated with the environment-sensitive fluorophore merocyanine through a single cysteine in 1F11. The binding of the adnectin 1F11 and the activated SFKs increased the fluorescence intensity from the merocyanine dye. Therefore, the SFKs’ activation kinetics can be investigated through analyzing the emission intensity ratios between the fluorescent protein mCerulean and the merocyanine dye (Figure 6a). For the purpose of tumor imaging, another example of generating a high-affinity monobody is the E1h monobody that binds to the membrane-bound hepatocellular receptor tyrosine kinase class A2 (EphA2), which is highly expressed in several types of cancers, including those of the lung, prostate, breast, and colon. In the study, E1h conjugated with NIR fluorescent dye Cy5.5 showed tumor targeting and imaging in a murine model of prostate cancer (102) (Figure 6b).

Figure 6.

(a) Applications of monobodies (adnectins) for in vitro and in vivo imaging. (i ) Schematic of the FN3 monobody library screening for SFK targeting binders; (ii ) biosensing mechanism of the SFK-targeting monobody; (iii ) SFK activation dynamics in living cells. Reproduced with permission from Reference 99. Copyright 2011, Macmillan Publishers. (iv) Differential interference contrast image (left) and ratio image (right) of PDGF-B–stimulated NIH 3T3 MEF cells microinjected with the SFK-targeting monobody. Scale bars are 20 μm. (v) Ratio image of a PTK1 cell microinjected with the biosensor. Scale bar is 20 μm. (b) In vivo targeting of the E1h monobody. Optical images of PC3 tumors after injection of E1h-Cy5.5 into mice. Nude mice were pretreated with nontagged E1h (+) or without (−). Panel reproduced with permission from Reference 102 under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license, http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0. Abbreviations: KD, knockdown; MEF, mouse embryonic fibroblast; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline; PDGF-B, platelet-derived growth factor B; SFK, Src family kinase; SH, Src homology.

Peptide Aptamers and Affimers

The concept of peptide aptamers first emerged in 1996 (103). A peptide aptamer is a combinatorial protein structure satisfying the conditions of a short peptide sequence. It is responsible for affinity binding with an inert and rigid protein scaffold for structure constraining in which both N- and C-termini of the binding peptide are embedded in the inert scaffold. The double-constrained structure is responsible for stabilizing the binding loop and increasing its affinity and specificity. A chemically stable, inert, modifiable scaffold protein with rigid structure is critical in the construction of the peptide aptamer. Colas et al. (103) chose the E. coli protein thioredoxin as the scaffold protein to build the peptide aptamer specific to the cyclin-dependent kinase 2 because of its stable and rigid structure and the capacity of bearing further peptide insertion (104). It is important to note that the rigid scaffold structure has a high capability to tolerate further modifications, including immobilization on detection platforms, which undoubtedly broadens the analytical applications of peptide aptamers.

Later, Stadler et al. (105) manufactured a structure known as SQT (Stefin A quadruple mutant-Tracy) with improved performance, making it the most popular choice as a peptide aptamer protein scaffold. Avacta Life Sciences developed a variety of peptide aptamer products based on the Stefin A variants and registered the trademark-named affimers for their products. Avacta applied their affimer products in various analytical systems, such as ELISA, microarrays, affinity chromatography, and immunohistochemistry (https://www.avacta.com/applications). Recently, Avacta announced the development of one affimer specific for the Zika virus antigen NS1 protein, which could enable the development of ELISA-like diagnostic tests of this threatening disease (https://www.avacta.com/news/avacta-rapidly-generates-affimer-binders-zika-virus-diagnostics).

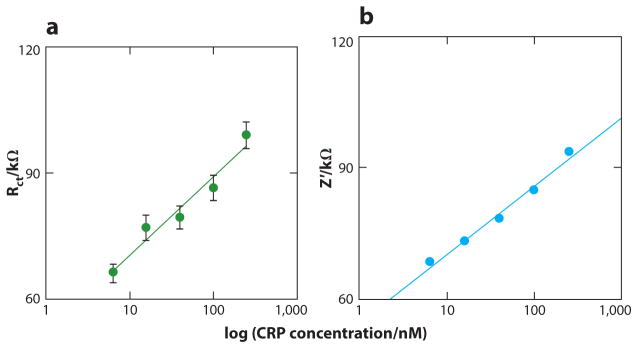

Other examples of the use of affimers include electrochemical impedance spectroscopy-based assays for C-reactive protein (CRP) using CRP-specific affimers, yielding detection limits as low as 300–500 pM (106) (Figure 7). These CRP assays were significantly more sensitive than current clinical diagnostic methods and are capable of monitoring subtle changes in serum CRP. In addition, these affimers showed better functional stability and lower initial charge transfer resistance when immobilized on the gold surface than fragile and bulky antibodies. Straw et al. (107) designed affimers for nine putative profibrotic biomarkers and verified the binding affinities through high-throughput affimer microarrays. Thirty-nine affimers that targeted eight of nine biomarkers showed specific binding capability. Among them, osteonectin and pigment epithelium–derived factor (PEDF)-specific affimers were employed to build both indirect and sandwich-type ELISA systems, respectively, for detection of recombinant PEDF proteins at physiological levels. However, for the detection of osteonectin, only the indirect assays achieved the detection levels needed, whereas the sandwich-type assays failed. This may be because, in this particular assay configuration, the capture and detection affimers bind to the same binding site of osteonectin.

Figure 7.

(a) Redox charge transfer resistance (Rct) plotted against a concentration of C-reactive protein (CRP) on a logarithmic scale for the P7i22 affimer interface. (b) The variance of the real part of impedance with log CRP concentration. Adapted with permission from Reference 106. Copyright 2012, American Chemical Society.

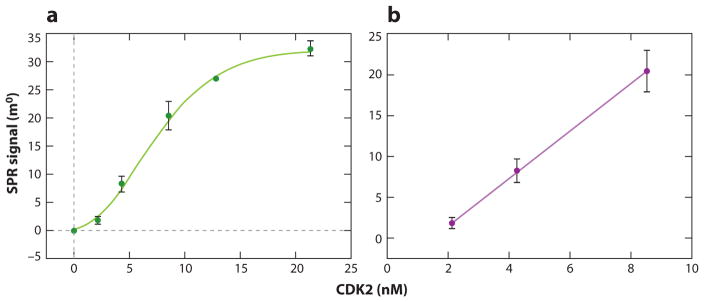

In another example, affimer molecules against cancer biomarker cyclin-dependent protein kinase 2 (CDK2) were utilized to develop sensitive detection assays for the active form of CDK2 via surface plasmon resonance (SPR) that is susceptible to the changes of the boundary surface (108). Davis et al. (108) immobilized the CDK2-specific affimers on a gold electrode or a [2-(2-pyridinyldithio) ethane amine] (PDEA) layer through a sulfhydryl group in the introduced surface cysteine, which controlled the binding orientation, and thus reduced the blockage of the binding sites. This SPR-based assay was able to distinguish the active CDK2 isoform from the nonactive one with a detection limit of 2 nM (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Binding curves of CDK2 on a PDEA-immobilized adlayer. (a) Signal dependence on the aqueous concentration of CDK2 target. (b) Linear range of CDK2 binding; error bars indicate assay reproducibility. Adapted with permission from Reference 108. Copyright 2009, American Chemical Society. Abbreviations: CDK2, cyclin-dependent protein kinase 2; PDEA, 2-(2-pyridinyldithio) ethane amine; SPR, surface plasmon resonance.

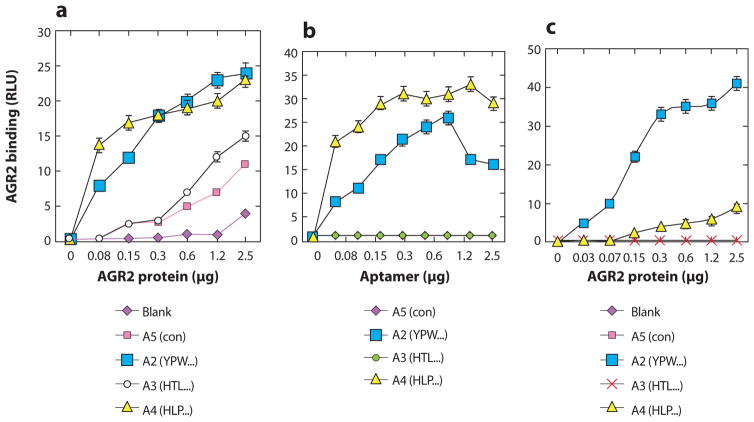

Also, a peptide aptamer specific to the anterior gradient-2 (AGR2) protein was able to effectively bind, purify, and quantify AGR2 protein (a cancer biomarker) from clinical biopsy lysates (109). Murray et al. (109) designed the AGR2-specific peptide aptamers and immobilized them on agarose beads through biotin–streptavidin interactions for the affinity purification of AGR2 in crude tissue lysates, realizing high-efficiency purification in one step. They also utilized the peptide aptamers as the capture reagents together with an anti-AGR2 primary antibody and a fluorescent-labeled secondary antibody to establish sandwich-type microarray assays for the quantification of AGR2 in tissue lysates that showed a linear detection range spanning from 0.03 to 0.5 μg/ml (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Peptide aptamers bind recombinant anterior gradient-2 (AGR2) in an ELISA. (a) AGR2 titration using peptide capture. (b) AGR2 capture using peptide titration. (c) AGR2 binding activity when adsorbed directly onto the solid phase. Adapted with permission from Reference 109. Copyright 2007, American Chemical Society. Abbreviations: ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; RLU, relative light units.

Affitins

Affitins are variants of the DNA binding protein Sac7d that are engineered to obtain specific binding affinities. Sac7d is originally derived from the hyperthermophile archaea Sulfolobus acidocaldarius and binds with DNA to prevent it from thermal denaturation (110). Sac7d contains 66 amino acids, forming an incomplete β-barrel structure composed of a two-stranded β-hairpin at the N-terminus and a three-stranded β-sheet capped by an α-helix at the C-terminus (111) (Figure 2d). Sac7d interacts with DNA through the three-stranded sheet, and thus, affitin proteins with particular binding affinities have been developed through randomization of 14 amino acids in the β-sheet (29, 112, 113). Affitins as the derivatives of Sac7d are highly resistant to a broad range of temperatures (up to 90°C) and pH (0–12) and can be produced in large quantities employing recombinant bacterial technologies (111, 114). For instance, affitins have been used for developing resins for affinity chromatography. Béhar et al. (114) attached affitins to N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS)-activated agarose beads through well-established protocols involving an NHS-amine coupling reaction to prepare affinity purification columns for three proteins: human IgG, bacterial PulD protein, and chicken egg lysozyme. These columns showed high affinity and specificity, yielding an ~95% purity and ~100% recovery. Moreover, the robust structure and outstanding stability of affitins facilitate the cleaning and regeneration procedures of these columns. Also, affitins against the N-domain of the secretin PulD have been used to investigate the structure and functions of the PulD protein both in vivo and in vitro, given that the binding affinity is highly sensitive to the conformational changes of PulD induced by the presence of denaturating compounds and Zwittergent 3–14 (29).

Anticalins

Anticalins are a group of binding proteins with a robust and conservative β-barrel structure found in lipocalins (34). Lipocalins are a class of extracellular proteins comprising one peptide chain (150–190 amino acids) that is in charge of recognition, storage, and transport of various biological molecules such as signaling molecules (115). Lipocalin proteins share a conservative β-barrel structure composed of eight antiparallel β-strands and a C-terminal α-helix. The natural binding surface of lipocalins consists of four exposed hypervariable loops that connect the β-strands pairwisely (116). Thus, anticalins with specific binding properties can be developed through the modification of amino acids of the four hypervariable loops. To date, anticalin molecules have been prepared and employed in bioanalytical and clinical applications against a variety of targets. For example, anticalin against the receptor tyrosine kinase MET was labeled with the radionuclide 89Zr chemically to image MET, a marker molecule overexpressed in cancer cells. This was used to investigate the distribution of the MET-specific anticalin in different organs through positron emission tomography (PET) imaging (117).

Another example involves using the antibody–anticalin fusion proteins in pretargeting applications. Two scFv fragments of the F8 antibody that targets the extra domain A of fibronectin, a tumor biomarker, and a fluorescein derivative-specific anticalin named FluA, were fused genetically to construct a fusion protein scFv(F8)–FluA–scFv(F8). Thus, the fusion protein was able to recognize both fibronectin and fluorescein derivatives, and therefore, could target the fluorescein dyes to tumor cells to implement in vivo imaging in mice (118). The scFv(F8)–FluA–scFv(F8) protein was injected into the mice bearing a subcutaneous F9 murine teratocarcinoma. Twenty-four hours after injection of the fusion protein, the fluorescein-labeled IRDye750 was injected into mice for imaging. The results showed that fluorescein-labeled IRDye750 was captured by the tumor, binding scFv(F8)–FluA–scFv(F8) and enabling in vivo imaging.

Atrimers

Atrimers are a scaffold derived from a trimeric plasma protein known as tetranectin, a family of C-type lectins consisting of three identical units (119). The structure of the C-type lectin domain (CTLD) within the tetranectin has five flexible loops that mediate interaction with targeting molecules (Figure 2f ) (120). The sequence of those loops can be altered without disrupting the overall CTLD structure (121), which allows for the use of phage display technology for selecting binding molecules. Several atrimers have been developed as therapeutic biologics to stimulate or block their specific ligands (43, 122). ATX 3105, the first lead atrimer biologic from Anaphore Inc., inhibits IL-23 receptor–triggered inflammatory signal transduction by blocking the binding of IL-23 by docking to its receptor. In addition, atrimers have lysine-rich unstructured regions at the N-terminus that are potentially suitable for delivering payloads of drugs and imaging reagents. Overall, based on their structural characteristics, atrimers are ideal binding molecules for target ligands that trimerize as a prerequisite for their biological activity. However, atrimers (60–70 kDa) are relatively large compared to other antibody mimetics scaffolds, thus limiting their applications.

Avimers

Avimers are molecules based on the A-domain of extracellular receptors. Typically, the A-domain consists of 35 amino acids (4 kDa) and contains three intramolecular disulfide bonds (123, 124). These molecules are highly resistant to temperature-mediated denaturation due to the presence of disulfide bonds (125). Additionally, avimers are relatively small in comparison to antibody mimetics scaffolds, such as tetranectin (20 kDa), protein A (7 kDa), and lipocalin (20 kDa). Avimers are developed by the sequential selection of individual binding domains that enable generation of multidomain scaffolds to recognize different epitopes in the same ligand, single ligands, or multiple target ligands (44). Avimers have shown high affinity and specificity against their ligands with picomolar binding constants as well as high therapeutic efficiency with IC50 in subpicomolar concentrations (125, 126). Based on this high specificity and the binding constants, avimers may offer advantages in the development of analytical, diagnostic, and therapeutic applications. For example, avimers with the ability to recognize different epitopes of analytes could be useful in the development of ELISA-type assays. In another configuration, bispecific avimers could enable simultaneous binding to cancer cells and immune cells, such as natural killer cells and cytotoxic T cells; the binding triggers cancer cells to undergo apoptosis, thereby killing the tumor cells. However, avimers require calcium to stabilize the binding to their corresponding ligand, which can hinder the efficiency of the recognition and binding process with the ligand in the presence of chelating agents such as EDTA. This agent is likely to be present in blood samples given that it is a commonly used anticoagulant.

Fynomers

Fynomers are small globular proteins (7 kDa) that evolved from amino acids 83–145 of the Src homology domain 3 (SH3) of the human Fyn tyrosine kinase. Their binding scaffolds contain two antiparallel β-sheets and two flexible loops (Figure 2g) (25). Fynomers are attractive binding molecules due to their high thermal stability, cysteine-free scaffold, and human origin, which reduce any potential immunogenicity. Grabulovski et al. (127) generated the Fyn SH3-derived proteins, which can bind the extracellular domain of fibronectin, a marker for tumor angiogenesis. In vitro selections were performed by phage display, and after three rounds of panning, the specific binder, named D3, was able to stain vascular structures in tumor sections by using an immunofluorescence method. This work also demonstrated a remarkable retention time of D3 dimer in tumors compared to D3 monomer in a mouse xenograft tumor model.

Recently, fynomers were fused with a therapeutic antibody to create a bispecific FynomAb to improve therapeutic efficacy. For example, FynomAb COVA322 is a fusion protein of the anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF) antibody adalimumab and a Fyn SH3-derived binding protein that specifically binds to IL-17A (55). Similarly, a bispecific FynomAb COVA208 was designed as a fusion between an anti-HER2 antibody pertuzumab and an anti-HER2 fynomer to endow the resulting fusion protein with the ability to target two different epitopes on the HER2 protein. This increased the binding affinity of this therapeutic agent to HER2 receptors on the surface of cancer cells (128).

Armadillo Repeat Proteins

Armadillo repeat proteins (ARMs) were first characterized in the Drosophila segment polarity protein Armadillo, a mammalian protein homologous to β-catenin. It comprises a repeating 42-amino–acid unit arranged in three α-helices (Figure 2h) (25, 129, 130). ARMs are abundant in eukaryotes and are involved in a broad range of biological processes, especially those related to nuclear transport. ARMs usually consist of three to five internal repeats and two capping elements. They also have a tandem elongated superhelical structure that enables binding with their corresponding peptide ligands in an extended conformation. These unique structural characteristics of ARMs make them attractive as scaffolds for the generation of peptide binders (131). As an example, ARMs have been generated for neurotensin, a 13-amino-acid peptide ligand of the G protein–coupled receptor (42). Due to their specificity as peptide binders, ARMs may provide potential uses in applications related to the detection of peptide-based biomarkers or the neutralization of toxic peptides, such as melittin and ponericin.

Kunitz Domain Inhibitors

Kunitz domain inhibitors are a class of protease inhibitors with irregular secondary structures containing ~60 amino acids with three disulfide bonds and three loops that can be mutated without destabilizing the structural framework (Figure 2i) (25, 132, 133). Kunitz domain inhibitors have been developed as therapeutic agents to target a variety of proteases. For example, ecallantide (DX-88), a plasma kallikrein inhibitor, was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of hereditary angioedema, a potentially life-threatening genetic disorder (134).

Knottins

Cysteine knot miniproteins, or knottins, are typically proteins 30 amino acids in length with a stable tertiary structure comprising three antiparallel β-sheets and constrained loops laced by a disulfide bond, which creates a cysteine knot (Figure 2j) (135, 136). This disulfide network confers a high thermal stability and proteolytic resistance, making knottins attractive for the development of non-antibody-based diagnostic, therapeutic, and bioanalytical methods (25). The best known example of knottins is ω-conotoxin MVIIa, an FDA-approved drug for severe chronic pain, which blocks calcium channels in nerves that transmit pain signals (137). Knottins can also be utilized for molecular imaging. An example involves the use of chlorotoxin conjugated to an NIR dye (Cy5.5) to discriminate between neuroectodermal tumors and healthy tissue in murine models (Figure 10a) (138, 139).

Figure 10.

(a) Detection of autochthonous medulloblastoma in genetically engineered mice. (i ) Biphotonic images of (left) tumor-free wild-type mouse and (right) mouse with medulloblastoma. (ii ) Images of brains from the same mice following necropsy confirm the signal from the tumor. (iii ) Histologic confirmation of medulloblastoma tumor. (iv) Confocal microscopy images from the same brain of mouse with medulloblastoma. Reproduced with permission from Reference 138. Copyright 2016, American Association for Cancer Research. (b) The AF680-EETI 2.5F dye illuminates mouse medulloblastoma in vivo. Mouse with (left) and without (right) tumor. Reproduced with permission from Reference 140. (c) Coronal micropositron emission tomography images of U87MG tumor-bearing mice at 0.5, 1, and 2 h postinjection of the 18F-FP-2.5D dye (top) with cyclic RGD pentapeptides as a blocking agent (bottom). Red arrows indicate tumors. Reproduced with permission from Reference 143 under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license, http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0.

The disulfide-constrained loops of native knottins possess high levels of sequence diversity. Therefore, modification of loop sequences, such as substitutions, additions, and deletions, have no effect on the overall knottin structure, which provides a framework for engineering molecules that bind to a variety of biomedical target ligands (49). Engineered knottin peptides are widely employed in molecular imaging. It is well known that integrin receptors are highly expressed in tumors, which are a suitable target for in vivo imaging. To that end, Moore et al. (140, 141) developed a fluorescent integrin-binding knottin peptide for optical imaging of intracranial medulloblastoma. To create this knottin-based imaging agent, the native binding loop in the knottin is replaced by an engineered integrin-binding loop with high affinity for the integrin receptors. Then, the modified knottin (EETI 2.5F) was conjugated with NIR dyes (AF680) at the N-terminus to create the imaging agent (Figure 10b). To achieve better depth of penetration of the knottin imaging agents, the integrin-binding knottins were conjugated with radioprobes (18F-NFP or 64Cu-DOTA) and employed to image murine glioma models with PET scans (Figure 10c) (142–144).

On the basis of the aforementioned characteristics and structural framework, knottins show several advantages over other binding molecules. Owing to their extraordinary stability, knottins have been considered as scaffolds for oral peptide drugs (145). Because knottins only consist of 30 amino acids, they can be generated chemically using peptide synthesizer, which avoids the cumbersome process of recombinant protein synthesis. Cox et al. (146) incorporated 5-azido-L-norvaline into integrin-targeting knottin peptides using SPPS for gemcitabine conjugation. The knottin–gemcitabine conjugates show high antitumor effects compared to gemcitabine.

Designed Ankyrin Repeat Proteins

Designed ankyrin repeat proteins (DARPins) are artificial scaffolds based on human ankyrin repeat domain proteins, which are abundant intracellular adaptor molecules that mediate a broad range of protein interactions in variety of biological events. DARPins are composed of two to four consensus repeats flanked by the N- and C-terminal capping repeats that are essential for efficient folding to prevent aggregation during protein expression. Each repeat molecule contains a β-turn followed by two antiparallel α-helices and an unstructured loop (Figure 2k) (147). DARPins have been used for various applications in the bioanalytical and biomedical fields due to their high binding constants, rapid clearance, and excellent tissue penetration. In addition, the lack of cysteine residues in DARPins is helpful because it increases solubility of DARPins during protein expression in E. coli. Given the lack of cysteines in their structure, it is possible to introduce a unique cysteine that is surface accessible for conjugation of a variety of molecules, such as drugs, proteins, imaging reagents, and nanomaterials, to the DARPin. The introduction of a unique cysteine into the DARPin structure also allows control of the orientation of conjugates to better diminish potential steric hindrance (148, 149).

DARPins themselves can function as antagonists to block specific signal transduction cascades that are associated with disease progression, especially in cancer and inflammatory diseases. Bis-pecific DARPins, prepared by genetic fusion of two monovalent DARPins that recognize two different epitopes in a target ligand, have also been generated to enhance the binding affinity and increase the therapeutic efficacy (45, 150–152).

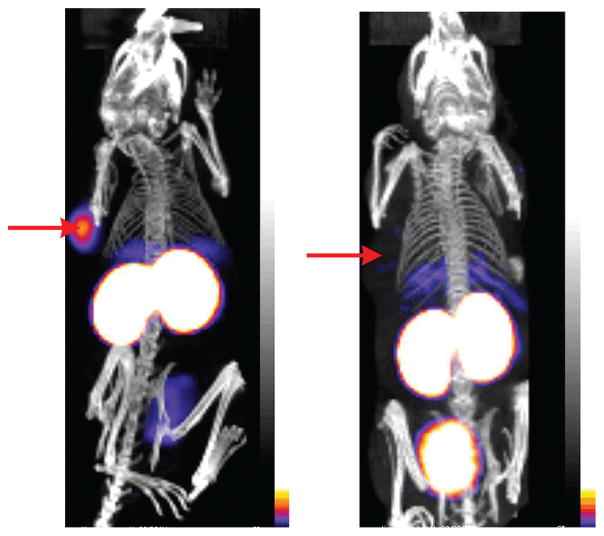

DARPins can play a role as targeting molecules to deliver a payload to target sites for diagnostics, imaging, or therapy. The G3-DARPins specifically target HER2 receptors (which are highly expressed in tumor cells) and have been conjugated with radioactive probes (111In and 125I) via DOTA linked to a C-terminal cysteine for single-photon emission computed tomography/computed tomography tumor imaging (Figure 11) (149). In this study, preadministration of trastuzumab, a therapeutic anti-HER2 monoclonal antibody, shows no interference in the uptake of G3-DARPin by HER2-positive tumors in vivo because trastuzumab and G3-DARPin recognize different epitopes of HER2 receptors, respectively.

Figure 11.

Micro single-photon emission computed tomography/computed tomography scans of [99mTc(CO)3]+-G3 DARPin-His6 at 1 h in SCID mice bearing (a) HER2-positive human breast tumor (arrow) and (b) HER2- negative human breast tumor (arrow). Reprinted with permission from Reference 149 under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license, http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0. Abbreviations: DARPin, designed ankyrin repeat protein; HER2, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2; SCID, severe combined immunodeficient.

The use of virus to deliver nucleic acid–based materials into cells is a promising approach for gene therapy, genome editing, and imaging. To enhance the efficiency of viral delivery systems, displaying DARPins on the surface of viral vectors was investigated by fusing DARPins with virus coat proteins and capsids (153–155). Münch et al. (154) have developed a DARP infused adeno- associated viral delivery system without observing off-targeting effects due to the depletion of DARPin-deficient viral particles by using immobilized metal ion affinity chromatography. Their system has shown the capability of detecting tumors in vivo and circulating tumor cells in blood with high specificity and sensitivity.

Adding diverse functional groups into the same binding protein would increase its functional spectrum for biomedical applications. Site-specific conjugation located away from the active site of the binding protein is the most common strategy to prevent the loss of binding ability to its preferred ligand due to the steric hindrance. In this regard, DARPin is one of most promising binders because its N-cap and C-cap repeat units do not usually involve the interactions with its ligand, which are the suitable sites for bioconjugation with other functional groups (104). Simon et al. (156, 157) have successfully generated bifunctionalized DARPins by introducing a C-terminal cysteine and N-terminal unnatural amino acid (azidohomoalanine) for conjugating different functional modules. In this study, Ec1 DARPin, which specifically targets EpCAM antigen on the surface of tumor cells, was labeled with cytotoxin at the C-terminus as a therapeutic module via maleimide–thiol coupling chemistry. Additionally, the serum albumin was conjugated at the N-terminal DARPin via click chemistry to extend the circulation half-life of the conjugates in vivo.

SUMMARY AND FUTURE CHALLENGES

The biomolecular recognition properties of antibodies have been exploited in various analytical methods and biotechnology since the early 1970s. The inherent selectivity of antibodies toward their antigens (ligand analyte) endows antibodies with ideal characteristics for the development of technologies that take advantage of binding events, such as sensing, immunoassays, separations, target delivery, and imaging. However, as explained throughout this review, immunoglobulins possess inherent limitations. They are large molecules containing three domains (two identical variables and one constant) held together by disulfide bonds. They also require posttranslational modifications, mainly glycosylation, which requires the use of eukaryotic cell lines to ensure proper folding and posttranslation modification of their structure. This results in a higher cost of production. Antibodies, given their large size and complex structure, are susceptible to degradation at extreme conditions of temperature and pH. Moreover, the large size of antibodies limits their ability to penetrate tissues. Modification of antibodies to change or impart additional chemical and/or structural characteristics is challenging, especially in the variable region. For example, the antigen binding site, a highly variable region that is responsible for antibodies’ unique binding capability, is buried within the structure of the complex and is difficult to access for chemical modification. Despite all the challenges and limitations of antibodies, the future with regard to applications of antibody technology is bright, mostly because of their ever-increasing use in targeted immunotherapy. This field has produced important advances in the treatment of different types of cancer and autoimmune diseases and will continue to expand, especially with regard to applications in individualized precise and accurate medicine. However, the aforementioned proven immunogenic responses, cross-reactivity, and other drawbacks of antibodies have spurred an increased interest in identifying alternative biorecognition elements that overcome these limitations.

The search for alternatives to antibodies that can address their shortcomings led to the design of antibody mimetics. Molecular engineering of binding protein scaffolds for use as antibody mimetics has emerged as a powerful strategy in the development of antibody mimetics. As described in this review, several different types of protein scaffolds have been engineered that either match or surpass the binding affinities of antibodies. Antibody mimetics have distinct advantages over antibodies because they have a simpler structure; this usually consists of a single domain with a few, if any, cysteine residues, which allow the preparation of antibody mimetics in soluble form in prokaryotic cells. Additionally, advancements in computational design, library construction, and selection systems have spurred the creation of novel antibody mimetics with exceptional selectivity and affinity. Similar strategies can also be employed to improve other properties of antibody mimetics, such as their stability in extreme temperature and pH environments and their high ionic strength.

Although antibody mimetics are highly desirable, the identification of protein scaffolds suitable for design and modification of mimetic entities to introduce high binding affinity and selectivity is not trivial and can translate into high costs for their development. At present, such a financial risk can only be undertaken by the private sector, mostly in the pharma and biotech areas, which can afford to invest in high R&D expenditure. To allow recovery of the research costs, most antibody mimetics developed are being employed as therapeutic agents in targeted immunotherapy. Despite the proven advantages of antibody mimetics, there remain several problematic issues inherent to their characteristics, such as immunogenicity, lack of effector functions, and short plasma half-life. For antibody mimetics to be competitive with regard to their widespread use in therapeutic applications and bioanalysis, the cost of identifying novel protein scaffolds through combinatorial DNA libraries, the high-throughput selection, and the enrichment process must decrease. Another bottleneck in the use of antibody mimetics for the design of new analytical and biomolecular tools involves their intellectual property protection by their developers in the private sector. The structures and sequences of already developed, patent-protected antibody mimetics are heavily guarded and not accessible to the scientific community, thus hindering potential advancements and use in areas other than therapeutics. Bringing the initial design and preparation of antibody mimetics costs down should remediate some of these problems and improve their accessibility to researchers. As a result, this should increase their use in the development of imaging systems, molecular diagnostics, biosensing, separations, targeted drug delivery systems, and binding assays. We envision that the use of antibody mimetics will continue to grow in bioanalysis and result in new methods that are selective, reproducible, accurate, and precise and that have unprecedented detection limits.

Acknowledgments

S.D. and S.K.D. would like to thank the National Science Foundation (ECC-08017788), Ministry of Defense of Israel, and the National Institutes of Health (R01GM047915 and R21AI124058–01). S.D. is grateful to the Miller School of Medicine of the University of Miami for the Lucille P. Markey Chair in Biochemistry and Molecular Biology.

Glossary

- HER2

human epidermal growth factor receptor 2

- 10Fn3

tenth human fibronectin type III domain

- COMP

cartilage oligomeric matrix protein

- Erk2

extracellular signal-regulated kinase 2

- CRP

C-reactive protein

- PEDF

pigment epithelium–derived factor

- CDK2

cyclin-dependent protein kinase 2

- PDEA

2-(2-pyridinyldithio) ethane amine

- AGR2

anterior gradient-2

- CTLD

C-type lectin domain

- SH3

Src homology domain 3

- ARM

Armadillo repeat protein

- NFP

nod factor perception protein

- DOTA

1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane-1,4,7,10-tetraacetic acid

- DARPin

designed ankyrin repeat protein

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

The authors are not aware of any affiliations, memberships, funding, or financial holdings that might be perceived as affecting the objectivity of this review.

LITERATURE CITED

- 1.Pier GB, Lyczak JB, Wetzler LM. Immunology, Infection, and Immunity. Washington, DC: ASM; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Woof JM, Burton DR. Human antibody-Fc receptor interactions illuminated by crystal structures. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:89–99. doi: 10.1038/nri1266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Litman GW, Rast JP, Shamblott MJ, Haire RN, Hulst M, et al. Phylogenetic diversification of immunoglobulin genes and the antibody repertoire. Mol Biol Evol. 1993;10:60–72. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kuhn P, Fühner V, Unkauf T, Moreira GM, Frenzel A, et al. Recombinant antibodies for di- agnostics and therapy against pathogens and toxins generated by phage display. Proteom Clin Appl. 2016;10:922–48. doi: 10.1002/prca.201600002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Waldmann H. Prospects for the application of antibodies in medicine. Methods Mol Med. 2000;40:63–72. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-076-4:63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rhodes KJ, Trimmer JS. Antibodies as valuable neuroscience research tools versus reagents of mass distraction. J Neurosci. 2006;26:8017–20. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2728-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gebauer M, Skerra A. Engineered protein scaffolds as next-generation antibody therapeutics. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2009;13:245–55. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2009.04.627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Steinmeyer DE, McCormick EL. The art of antibody process development. Drug Discov Today. 2008;13:613–18. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2008.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Holliger P, Hudson PJ. Engineered antibody fragments and the rise of single domains. Nat Biotechnol. 2005;23:1126–36. doi: 10.1038/nbt1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deckert PM. Current constructs and targets in clinical development for antibody-based cancer therapy. Curr Drug Targets. 2009;10:158–75. doi: 10.2174/138945009787354502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weisser NE, Hall JC. Applications of single-chain variable fragment antibodies in therapeutics and diagnostics. Biotechnol Adv. 2009;27:502–20. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2009.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Murali R, Greene MI. Structure based antibody-like peptidomimetics. Pharmaceuticals. 2012;5:209–35. doi: 10.3390/ph5020209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nelson AL. Antibody fragments: hope and hype. mAbs. 2010;2:77–83. doi: 10.4161/mabs.2.1.10786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hamers-Casterman C, Atarhouch T, Muyldermans S, Robinson G, Hamers C, et al. Naturally occurring antibodies devoid of light chains. Nature. 1993;363:446–48. doi: 10.1038/363446a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harmsen MM, De Haard HJ. Properties, production, and applications of camelid single-domain antibody fragments. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2007;77:13–22. doi: 10.1007/s00253-007-1142-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sundberg EJ, Mariuzza RA. Molecular recognition in antibody-antigen complexes. Adv Protein Chem. 2002;61:119–60. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3233(02)61004-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cortez-Retamozo V, Lauwereys M, Hassanzadeh GG, Gobert M, Conrath K, et al. Efficient tumor targeting by single-domain antibody fragments of camels. Int J Cancer. 2002;98:456–62. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lipovsek D. Adnectins: engineered target-binding protein therapeutics. Protein Eng Des Sel. 2011;24:3–9. doi: 10.1093/protein/gzq097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harris MD, Tombelli S, Marazza G, Turner APF. Affibodies as an alternative to antibodies in biosensors for cancer markers. Woodhead Publ Ser Biomater. 2012;45:217–32. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Justino CIL, Duarte AC, Rocha-Santos TAP. Analytical applications of affibodies. Trends Anal Chem. 2015;65:73–82. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fernandez LA. Prokaryotic expression of antibodies and affibodies. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2004;15:364–73. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2004.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mirecka EA, Hey T, Fiedler U, Rudolph R, Hatzfeld M. Affilin molecules selected against the human papillomavirus E7 protein inhibit the proliferation of target cells. J Mol Biol. 2009;390:710–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fiedler E, Fiedler M, Proetzel G, Scheuermann T, Fiedler U, Rudolph R. Affilin molecules: novel ligands for bioseparation. Food Bioprod Process. 2006;84:3–8. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ebersbach H, Fiedler E, Scheuermann T, Fiedler M, Stubbs MT, et al. Affilin-novel binding molecules based on human γ-B-crystallin, an all β-sheet protein. J Mol Biol. 2007;372:172–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.06.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weidle UH, Auer J, Brinkmann U, Georges G, Tiefenthaler G. The emerging role of new protein scaffold-based agents for treatment of cancer. Cancer Genom Proteom. 2013;10:155–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Löfblom J, Frejd FY, Ståhl S. Non-immunoglobulin based protein scaffolds. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2011;22:843–48. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2011.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Škrlec K, Štrukelj B, Berlec A. Non-immunoglobulin scaffolds: a focus on their targets. Trends Biotechnol. 2015;33:408–18. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2015.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Skvortsov VT. Effects of variable peptides (affimers) of human immunoglobulin light chains on DNA synthesis by lymphoid cells in vitro. Immunologiya. 1995;6:18–21. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Krehenbrink M, Chami M, Guilvout I, Alzari PM, Pécorari F, Pugsley AP. Artificial binding proteins (affitins) as probes for conformational changes in secretin PulD. J Mol Biol. 2008;383:1058–68. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miranda FF, Brient-Litzler E, Zidane N, Pécorari F, Bedouelle H. Reagentless fluorescent biosensors from artificial families of antigen binding proteins. Biosens Bioelectron. 2011;26:4184–90. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2011.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Béhar G, Pacheco S, Maillasson M, Mouratou B, Pécorari F. Switching an anti-IgG binding site between archaeal extremophilic proteins results in Affitins with enhanced pH stability. J Biotechnol. 2014;192:123–29. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2014.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Béhar G, Bellinzoni M, Maillasson M, Paillard-Laurance L, Alzari PM, et al. Tolerance of the archaeal Sac7d scaffold protein to alternative library designs: characterization of anti-immunoglobulin G Affitins. Protein Eng Des Sel. 2013;26:267–75. doi: 10.1093/protein/gzs106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Desmet J, Verstraete K, Bloch Y, Lorent E, Wen Y, et al. Structural basis of IL-23 antagonism by an Alphabody protein scaffold. Nat Commun. 2014;5:5237. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Richter A, Eggenstein E, Skerra A. Anticalins: exploiting a non-Ig scaffold with hypervariable loops for the engineering of binding proteins. FEBS Lett. 2014;588:213–18. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2013.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Skerra A. Anticalins as alternative binding proteins for therapeutic use. Curr Opin Mol Ther. 2007;9:336–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weiss GA, Lowman HB. Anticalins versus antibodies: made-to-order binding proteins for small molecules. Chem Biol. 2000;7:R177–84. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(00)00016-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wu X, Chen J, Wu M, Zhao JX. Aptamers: active targeting ligands for cancer diagnosis and therapy. Theranostics. 2015;5:322–44. doi: 10.7150/thno.10257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nezlin R. Aptamers in immunological research. Immunol Lett. 2014;162:252–55. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2014.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li J, Tan S, Chen X, Zhang CY, Zhang Y. Peptide aptamers with biological and therapeutic applications. Curr Med Chem. 2011;18:4215–22. doi: 10.2174/092986711797189583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Coates JC. Armadillo repeat proteins: beyond the animal kingdom. Trends Cell Biol. 2003;13:463–71. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(03)00167-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Parmeggiani F, Pellarin R, Larsen AP, Varadamsetty G, Stumpp MT, et al. Designed armadillo repeat proteins as general peptide-binding scaffolds: consensus design and computational optimization of the hydrophobic core. J Mol Biol. 2008;376:1282–304. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Varadamsetty G, Tremmel D, Hansen S, Parmeggiani F, Pluckthun A. Designed Armadillo repeat proteins: library generation, characterization and selection of peptide binders with high specificity. J Mol Biol. 2012;424:68–87. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2012.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Allen JE, Ferrini R, Dicker DT, Batzer G, Chen E, et al. Targeting TRAIL death receptor 4 with trivalent DR4 atrimer complexes. Mol Cancer Ther. 2012;11:2087–95. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-12-0366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jeong KJ, Mabry R, Georgiou G. Avimers hold their own. Nat Biotechnol. 2005;23:1493–94. doi: 10.1038/nbt1205-1493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Boersma YL, Plückthun A. DARPins and other repeat protein scaffolds: advances in engineering and applications. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2011;22:849–57. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2011.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stumpp MT, Amstutz P. DARPins: a true alternative to antibodies. Curr Opin Drug Discov Dev. 2007;10:153–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tamaskovic R, Simon M, Stefan N, Schwill M, Plückthun A. Designed ankyrin repeat proteins (DARPins) from research to therapy. Methods Enzymol. 2012;503:101–34. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-396962-0.00005-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Banner DW, Gsell B, Benz J, Bertschinger J, Burger D, et al. Mapping the conformational space accessible to BACE2 using surface mutants and cocrystals with Fab fragments, Fynomers and Xaperones. Acta Crystallogr D. 2013;69:1124–37. doi: 10.1107/S0907444913006574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schlatter D, Brack S, Banner DW, Batey S, Benz J, et al. Generation, characterization and structural data of chymase binding proteins based on the human Fyn kinase SH3 domain. MAbs. 2012;4:497–508. doi: 10.4161/mabs.20452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Moore SJ, Leung CL, Cochran JR. Knottins: disulfide-bonded therapeutic and diagnostic peptides. Drug Discov Today Technol. 2012;9:e3–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ddtec.2011.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gracy J, Chiche L. Structure and modeling of knottins, a promising molecular scaffold for drug discovery. Curr Pharm Des. 2011;17:4337–50. doi: 10.2174/138161211798999339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sankaran S, de Ruiter M, Cornelissen JJLM, Jonkheijm P. Supramolecular surface immobilization of knottin derivatives for dynamic display of high affinity binders. Bioconjug Chem. 2015;26:1972–80. doi: 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.5b00419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Demeule M, Currie JC, Bertrand Y, Che C, Nguyen T, et al. Involvement of the low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein in the transcytosis of the brain delivery vector Angiopep-2. J Neurochem. 2008;106:1534–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05492.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Regina A, Demeule M, Che C, Lavallee I, Poirier J, et al. Antitumour activity of ANG1005, a conjugate between paclitaxel and the new brain delivery vector Angiopep-2. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;155:85–97. doi: 10.1038/bjp.2008.260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Silacci M, Lembke W, Woods R, Attinger-Toller I, Baenziger-Tobler N, et al. Discovery and characterization of COVA322, a clinical-stage bispecific TNF/IL-17A inhibitor for the treatment of inflammatory diseases. mAbs. 2016;8:141–49. doi: 10.1080/19420862.2015.1093266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Duan J, Wu J, Valencia CA, Liu R. Fibronectin type III domain based monobody with high avidity. Biochemistry. 2007;46:12656–64. doi: 10.1021/bi701215e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mann JK, Wood JF, Stephan AF, Tzanakakis ES, Ferkey DM, Park S. Epitope-guided engineering of monobody binders for in vivo inhibition of Erk-2 signaling. ACS Chem Biol. 2013;8:608–16. doi: 10.1021/cb300579e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Koide A, Koide S. Monobodies: antibody mimics based on the scaffold of the fibronectin type III domain. Methods Mol Biol. 2007;352:95–109. doi: 10.1385/1-59745-187-8:95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sullivan MA, Brooks LR, Weidenborner P, Domm W, Mattiacio J, et al. Anti-idiotypic monobodies derived from a fibronectin scaffold. Biochemistry. 2013;52:1802–13. doi: 10.1021/bi3016668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Huet S, Gorre H, Perrocheau A, Picot J, Cinier M. Use of the Nanofitin alternative scaffold as a GFP-ready fusion tag. PLOS ONE. 2015;10:e0142304. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0142304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mouratou B, Béhar G, Paillard-Laurance L, Colinet S, Pecorari F. Ribosome display for the selection of Sac7d scaffolds. Methods Mol Biol. 2012;805:315–31. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-379-0_18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Skerra A. Engineered protein scaffolds for molecular recognition. J Mol Recognit. 2000;13:167–87. doi: 10.1002/1099-1352(200007/08)13:4<167::AID-JMR502>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Skerra A. Imitating the humoral immune response. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2003;7:683–93. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2003.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sheridan C. Pharma consolidates its grip on post-antibody landscape. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25:365–66. doi: 10.1038/nbt0407-365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]