Abstract

Background

Hepatocarcinogenicity of Aflatoxin B1 (AFB1) has rarely been studied in populations with hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection and those without hepatitis B virus (HBV) and HCV infection (non-B-non-C). This case-control study nested in a community-based cohort aimed to investigate the HCC risk associated with AFB1 in HCV-infected and non-B-non-C participants.

Methods

Baseline serum AFB1-albumin adduct levels were measured in 100 HCC cases and 1767 controls seronegative for anti-HCV and HBsAg (non-B-non-C), and another 103 HCC cases and 176 controls who were anti-HCV-seropositive and HBsAg-seronegative. Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) were estimated using logistic regression.

Results

In 20 years of follow-up, the follow-up time to newly-developed HCC was significantly shorter in participants with higher serum AFB1-albumin adduct levels in non-B-non-C (p=0.0162) and HCV-infected participants (p<0.0001). Within 8 years of follow-up, HCV infection and AFB1 exposure were independent risk factors for HCC. Elevated serum AFB1-albumin adduct levels were significantly associated with an increased risk of HCC newly-developed within 8 years of follow-up in non-B-non-C participants with habitual alcohol consumption [crude OR (95% CI) for high vs. low/undetectable levels, 4.22 (1.16–15.37)] and HCV-infected participants [3.39 (1.31–8.77)], but not in non-B-non-C participants without alcohol drinking habit. AFB1 exposure remained an independent risk predictor for HCV-related HCC after adjustment for other HCC predictors [multivariate-adjusted OR (95% CI), 3.65 (1.32–10.10)].

Conclusions

AFB1 exposure contributes to the development of HCC in participants with significant risk factors for cirrhosis including alcohol and HCV infection.

Keywords: Aflatoxin B1, albumin adducts, HCC, HCV infection, habitual alcohol drinking

Introduction

Liver cancer is the sixth most prevalent cancer in the world. Due to the poor prognosis and a high mortality-to-incidence ratio of 0.95, it is also ranked as the second leading cause of cancer-related death worldwide with 745,000 deaths in 2012 (9.1% of total) [1]. Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the most common liver cancer (70%–90%) [2]. Viral hepatitis is the major risk factor for HCC. Approximately 80% of HCC cases are associated with chronic infection with hepatitis B virus (HBV) or hepatitis C virus (HCV) [3].

Aflatoxins are a group of naturally occurring mycotoxins produced by Aspergillus fungi [4]. Aflatoxin B1 (AFB1) is one of the most potent chemical liver carcinogens and also an important non-viral risk factor for HCC in humans [5,6]. A previous study estimated that about 5–28% of global HCC cases are attributable to aflatoxin exposure [7]. The major route of AFB1 exposure is ingestion of crops such as corn, peanuts, and rice. Liver is the primary target organ of AFB1 toxicity. AFB1 is preliminarily metabolized and activated by cytochrome P450 enzymes. The epoxidation of AFB1 results in the highly active AFB1 8,9-exo-epoxide which can covalently interact with DNA to form promutagenic AFB1-N7-guanine adducts. AFB1-N7-guanine adducts are released and subsequently excreted in the urine [4]. AFB1 8,9-exo-epoxide can also bind to proteins including albumin to form AFB1-albumin adducts [8].

AFB1-associated risk of HCC has been primarily investigated in populations with a high prevalence of HBV infection [9]. Several cohort studies have demonstrated the strong synergistic interaction between chronic HBV infection and AFB1 exposure [10–13]. The relative risk (RR) of developing HCC was much higher for individuals with both HBsAg seropositivity and detectable urinary levels of aflatoxin metabolites [RR (95% CI), 59.4 (16.6–212.0)] than those with detectable urinary levels of aflatoxin metabolites alone [RR (95% CI), 3.4 (1.1–10.0)] and those with HBsAg seropositivity alone [RR (95% CI), 7.3 (2.2–24.4)] when compared to those without these two risk factors as the referent [RR=1.0] [13]. However, the hepatocarcinogenicity of AFB1 has rarely been studied in populations with HCV infection and those without HBV and HCV infection (non-B-non-C).

Biomarkers of AFB1 exposure include aflatoxin M1 (AFM1), aflatoxin-mercapturic acid, and AFB1-N7-guanine adducts in urine as well as AFB1-albumin adducts in serum [14,15]. Aflatoxin-DNA and aflatoxin-protein adducts are the products of damages to critical molecular targets, which may be used as markers for the biologically effective dose of aflatoxin exposure. In addition to a long half-life of 3-weeks, aflatoxin-albumin adducts in serum samples have also been shown to be stable after long-term storage (at least 25 years) [16], which makes aflatoxin-albumin adducts a suitable biomarker for epidemiological studies.

In Taiwan, the estimated prevalence of antibody against HCV (anti-HCV) is 4.9% in the general population [17,18]. We enrolled a Community-based Cancer Screening Project (CBCSP) cohort in 1991–1992, and all the participants were examined for their serostatus of HBV surface antigen (HBsAg) and anti-HCV. In addition, participants were followed up for newly-diagnosed HCC until 2011. In this case-control study nested in the CBCSP cohort, baseline serum AFB1-albumin adduct levels were measured to evaluate the AFB1 exposure in HBsAg-seronegative participants. We aimed to investigate the impact of AFB1 exposure on the onset time and risk of HCC in HCV-infected and non-B-non-C participants.

Materials and methods

Study cohort

Study participants were selected from the CBCSP cohort established in 1991–1992. A total of 23,820 residents aged 30 to 65 years were recruited from seven townships in Taiwan [11,19]. The study area included four townships located on the main Taiwan Island and three townships located on Penghu Islets, which has the highest HCC mortality rate in Taiwan. A previous survey has shown the peanuts in Penghu were heavily contaminated by aflatoxin [20]. Besides, residents in Penghu had slightly higher seropositive rates of HBsAg [19] and anti-HCV [21] than those of the general population in Taiwan. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the College of Public Health, National Taiwan University, Taipei, Taiwan and all participants provided written informed consent.

At study entry, information on sociodemographic characteristics, habits of alcohol consumption and cigarette smoking, and family history of major diseases was collected through personal interview by trained public health nurses with a structured questionnaire. Habitual alcohol consumption was defined as drinking alcohol-containing products more than 4 days a week for at least 6 months. Habitual cigarette smoking was defined as having smoked more than 4 days a week for at least 6 months. Major diseases collected in the family history were cardiovascular diseases, hypertension, stroke, diabetes mellitus, cirrhosis, and major cancers including liver cancer, lung cancer, stomach cancer, nasopharyngeal cancer, breast cancer, cervical cancer and other cancers. Participants also received a health examination including abdominal ultrasonography and serological tests of HBsAg, hepatitis B e antigen, anti-HCV, and serum levels of alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and α-fetoprotein (AFP).

Follow-up for HCC cases

During the follow-up period from study entry in 1991–1992 to June 30, 2004, participants seropositive for HBsAg or anti-HCV, with elevated serum levels of ALT (≥45 IU/mL), AST (≥40 IU/mL), or AFP (≥20 ng/mL), or with a family history of HCC were regularly followed up by abdominal ultrasonography and serological tests. Newly-developed HCC cases were detected by regular health examinations including abdominal ultrasonography and AFP testing before June 30, 2004 and computerized data linkage to the National Cancer Registry database until December 31, 2011. Medical chart reviews were performed to confirm the diagnosis of HCC. The diagnostic criteria include: (a) histopathologically confirmed HCC lesion; (b) HCC lesion detected by two imaging techniques (abdominal ultrasonography, angiogram, or computed tomography); or (c) HCC lesion detected by one imaging technique in combination with an elevated serum AFP level (≥400 ng/mL).

Study participants

Until December 31, 2011, a total of 506 newly-developed HCC cases were identified from the CBCSP cohort. 2636 controls unaffected by HCC through the follow-up period were matched to the HCC cases on age (±5 years), gender, residence, and date of blood sample collection (±3 months). The control-to-case ratio ranged from two to six. In order to control the potential confounding effect of cirrhosis and HBV infection on HCC, participants with cirrhosis at study entry (31 controls and 40 HCC cases) and seropositive for HBsAg (655 controls and 260 HCC cases) were excluded. Additional 7 controls and 3 HCC cases were excluded due to their missing data for anti-HCV serostatus. A total of 203 newly-developed HCC cases and 1943 controls were included in this study. There were 100 HCC cases and 1767 controls seronegative for both HBsAg and anti-HCV (non-B-non-C), as well as 103 cases and 176 controls who were anti-HCV-seropositive and HBsAg-seronegative (HCV-infected).

Serological test

Blood samples collected at study entry were tested for seropositivity of HBsAg and anti-HCV, and for serum levels of ALT, AST, and AFP. HBsAg, anti-HCV and AFP by immunoassay (Abbott Laboratories). Levels of ALT and AST were determined by serum chemistry autoanalyzer (Model 736, Hitachi Co.) using commercial reagents (Biomerieux).

Determination of serum AFB1-albumin adduct levels

AFB1-albumin adduct levels were measured by ELISA in serum samples collected at study entry as previously described [19,22]. Briefly, 50 μL of proteinase K-digested albumin extract (200 μg) was applied into 96-well plates coated with 3 ng of AFB1 epoxide-modified human serum albumin. The primary and secondary antisera for the ELISA were polyclonal antiserum 7 (1:2×105 dilution) and goat anti-rabbit IgG-alkaline phosphatase (1:750 dilution), respectively. Serial dilutions of enzymatically digested AFB1 epoxide-modified human serum albumin were used for the standard curve for determination of AFB1-albumin adducts concentration. Samples with <15% inhibition were considered undetectable and assigned a value of 1 fmol/mg. All samples were assayed in duplicate with laboratory staff blinded to case status. With each batch of the test samples, a pooled sample of plasma from nonsmoking participants from the United States and serum from a rat treated with 1.5 mg of AFB1 were analyzed as negative and positive controls, respectively. The serum samples were analyzed in three different batches. The percentages of samples with undetectable levels in control participants were 41.3%, 45.6%, and 49.7%. The median detectable adduct levels among the pooled control participants, 21.5 fmol/mg was used as the cutoff for low and high levels of AFB1-albumin adducts.

Statistical analysis

Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was performed to test for the significance of the difference in the frequency distribution of follow-up time to diagnosis in HCC cases with different AFB1-albumin adducts levels. The t-test was used to examine the difference in follow-up time to diagnosis between HCC cases with low/undetectable and high serum levels of AFB1-albumin adducts. For the analysis of association with HCC for various risk factors, univariate logistic regression analysis was performed to estimate the crude odds ratio (cOR) and the 95% confidence interval (CI). Initially, all variables with a p value less than 0.1 were included in the multiple logistic regression model. Further backward selection was performed to obtain the final multivariate logistic regression model from which the adjusted odds ratio (aOR) and the corresponding 95% CI were derived. SAS 9.4 (Cary, NC) was employed for data management and all statistical analyses.

Results

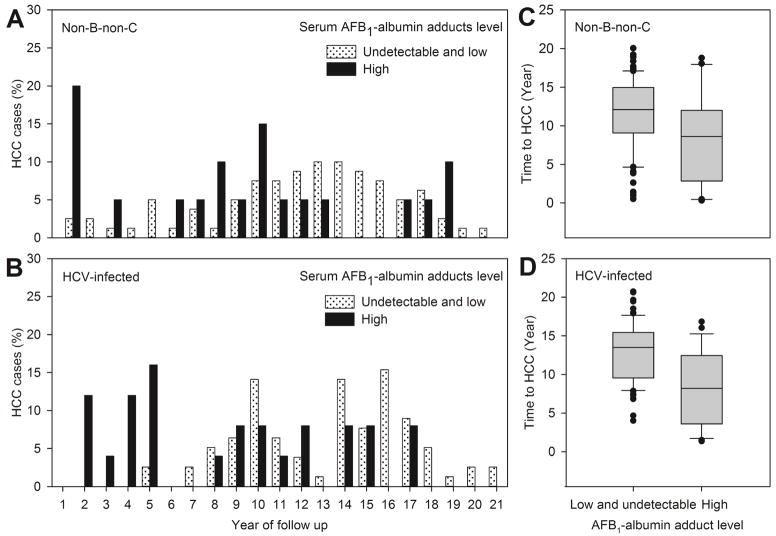

Figure 1 shows the frequency distribution of follow-up time from study entry to diagnosis of newly-developed HCC in non-B-non-C and HCV-infected participants by baseline serum AFB1-albumin adduct levels. As shown in Figure 1A and 1B, significantly higher percentages of participants with high serum levels of AFB1-albumin adducts were diagnosed in earlier years of follow-up compared to those with low/undetectable levels in 100 non-B-non-C participants (p=0.05) and 103 HCV-infected participants (p=0.003). The follow-up years (mean ± standard deviation) to HCC diagnosis in participants with low/undetectable and high serum levels of AFB1-albumin adducts were 11.6 ± 4.6 years and 8.6 ± 6.0 years, respectively, in non-B-non-C participants (Figure 1C), and 12.9 ± 3.8 years and 8.0 ± 4.9 years, respectively, in HCV-infected participants (Figure 1D). The follow-up time to HCC significantly decreased with increasing serum AFB1-albumin adduct levels in non-B-non-C (p=0.0162) and HCV-infected (p<0.0001) participants.

Figure 1. Frequency distribution and box plot of follow-up time from study entry to diagnosis of newly-developed HCC in HCV-infected and non-B-non-C participants by baseline serum AFB1-albumin adduct levels.

(A) Distribution of the follow-up time to HCC in non-B-non-C participants (n=100) (low/undetectable vs. high, p=0.05 for testing equality of distribution). (B) Distribution of the follow-up time to HCC in HCV-infected participants (n=103) (low/undetectable vs. high, p=0.003 for testing equality of distribution). (C) Box plot of follow-up year to HCC diagnosis in non-B-non-C participants (means ± standrad devition of 11.6±4.6 years vs. 8.6±6.0 years for low/undetectable vs. high serum levels of AFB1-albumin adducts. p=0.0162). (D) Box plot of follow-up year to HCC diagnosis in HCV-infected participants (means ± standard deviation of 12.9 ± 3.8 years vs. 8.0 ± 4.9 years for low/undetectable vs. high levels of AFB1-albumin adduct. p<0.0001). In the box plot, the filled circles indicate the outliers lying outside the 10th and 90th percentiles

Because the average follow-up years to HCC diagnosis in participants with high serum levels of AFB1-albumin adducts in non-B-non-C and HCV-infected participants were 8.6 and 8.0 years, respectively, we further examined the associations between the baseline serum AFB1-albumin adduct level and the risk of developing HCC during the entire follow-up period of 20 years and within 8 years of follow-up after study entry, respectively. As shown in Table 1, the baseline serum AFB1-albumin adduct level was not significantly associated with the risk of newly-developed HCC during the entire follow-up period of 20 years [cOR (95% CI), 0.90 (0.63–1.27) for high vs. low/undetectable levels; p=0.54]. However, within 8 years of follow-up after study entry, high baseline serum AFB1-albumin adduct levels were significantly associated with an increased risk of HCC compared to low/undetectable levels [cOR (95% CI), 2.88 (1.58–5.25); p=0.0006]. HCV-infected participants with high serum AFB1-albumin adduct levels had a much higher risk of HCC [cOR (95% CI), 20.04 (8.95–44.89); p<0.0001] than those with high serum AFB1-albumin adduct levels alone [cOR (95% CI), 1.96 (0.85–4.51); p=0.11] or HCV infection alone [cOR (95% CI), 5.91 (2.46–14.23); p<0.0001] in comparison to non-B-non-C participants with low/undetectable serum AFB1-albumin adduct levels as the referent group (cOR=1.00). However, the interaction between AFB1 exposure and HCV infection on HCC risk was not statistically significant on either an additive scale [relative excess risk due to interaction (RERI) (95% CI), 13.17 (−1.50–27.84)] or multiplicative scale (p=0.39).

Table 1.

Association between AFB1 exposure and risk of hepatocellular carcinoma by HCV infection

| Control (%) (n=1943) | 20 years of follow-up | Within 8 years after study entry | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||||

| Case (%) (n=203) | Crude odds ratio (95% CI) | p value | Case (%) (n=44) | Crude odds ratio (95% CI)b, c | p value | ||

| AFB1-albumin levela | |||||||

| Low and undetectable | 1475 (75.9) | 158 (77.8) | 1.00 (Referent) | 23 (52.3) | 1.00 (Referent) | ||

| High | 468 (24.1) | 45 (22.2) | 0.90 (0.63–1.27) | 0.54 | 21 (47.7) | 2.88 (1.58–5.25) | 0.0006 |

| Virus infection|AFB1-albumin levela | |||||||

| Non-B-non-C|Low and undetectable | 1353 (69.6) | 80 (39.4) | 1.00 (Referent) | 15 (34.1) | 1.00 (Referent) | ||

| Non-B-non-C|High | 414 (21.3) | 20 (9.9) | 0.82 (0.49–1.35) | 0.43 | 9 (20.5) | 1.96 (0.85–4.51) | 0.11 |

| HCV-infected|Low and undetectable | 122 (6.3) | 78 (38.4) | 10.82 (7.53–15.54) | <0.0001 | 8 (18.2) | 5.91 (2.46–14.23) | <0.0001 |

| HCV-infected|High | 54 (2.8) | 25 (12.3) | 7.83 (4.63–13.24) | <0.0001 | 12 (27.3) | 20.04 (8.95–44.89) | <0.0001 |

Low, <21.5 fmol/mg; high, ≥21.5 fmol/mg.

Measure of effect modification on additive scale: relative excess risk due to interaction (RERI) (95% CI), 13.17 (−1.50–27.84).

Measure of effect modification on multiplicative scale: p=0.39.

The associations with the risk of HCC developing within 8 years of follow-up were further investigated for documented HCC risk factors. The distributions of age (mean ± standard deviation, 52.9 ± 8.1 vs. 55.3 ± 6.8; p=0.0574) and gender (male, 73.6% vs. 72.7%; p=0.90) were not significantly different between controls and HCC cases. Table 2 shows the crude and multivariate-adjusted ORs with their 95% CIs of each risk predictor for HCC. Habitual cigarette smoking [cOR (95% CI), 1.92 (1.05–3.52); p=0.0355], habitual alcohol drinking [cOR (95% CI), 1.98 (1.01–3.88); p=0.0474], obesity [body mass index ≥27; cOR (95% CI), 2.43 (1.30–4.54); p=0.0053], elevated serum levels of ALT [cOR (95% CI), 5.31 (2.39–11.81); p<0.0001], HCV infection [cOR (95% CI), 8.37 (4.53–15.45); p<0.0001], and high serum levels of AFB1-albumin adducts [cOR (95% CI), 2.88 (1.58–5.25); p=0.0006] were significantly associated with an increased risk of HCC newly developed within 8 years of follow-up. In the multivariate logistic regression model, only habitual alcohol drinking, obesity, HCV infection, and serum AFB1-albumin adduct level remained statistically significant. The aOR (95% CI) of high serum levels of AFB1-albumin adducts compared to low/undetectable levels was 2.43 (1.31–4.52) with a p value of 0.0051.

Table 2.

Crude and multivariate-adjusted odds ratios of risk predictors for hepatocellular carcinoma diagnosed within 8 years of follow-up

| Baseline characteristics | Controls (%) (n=1943) | HCC (%) (n=44) | Crude odds ratio (95% CI) | p value | Final multivariate model | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Adjusted odds ratio (95% CI) | p value | |||||

| Habitual cigarette smokinga | ||||||

| No | 1108 (57.1) | 18 (40.9) | 1.00 (Referent) | |||

| Yes | 834 (43.0) | 26 (59.1) | 1.92 (1.05–3.52) | 0.0355d | (not included in model) | |

| Habitual alcohol drinkingb | ||||||

| No | 1630 (84.1) | 32 (72.7) | 1.00 (Referent) | 1.00 (Referent) | ||

| Yes | 309 (15.9) | 12 (27.3) | 1.98 (1.01–3.88) | 0.0474d | 2.36 (1.16–4.80) | 0.0175 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | ||||||

| <27 | 1573 (81.0) | 28 (63.6) | 1.00 (Referent) | 1.00 (Referent) | ||

| ≥27 | 370 (19.0) | 16 (36.4) | 2.43 (1.30–4.54) | 0.0053d | 2.69 (1.41–5.16) | 0.0028 |

| Serum ALT level (U/L) | ||||||

| <45 | 1865 (96.0) | 36 (81.8) | 1.00 (Referent) | |||

| ≥45 | 78 (4.0) | 8 (18.2) | 5.31 (2.39–11.81) | <0.0001d | (not included in model) | |

| Anti-HCV | ||||||

| Seronegative | 1767 (90.9) | 24 (54.6) | 1.00 (Referent) | 1.00 (Referent) | ||

| Seropositive | 176 (9.1) | 20 (45.5) | 8.37 (4.53–15.45) | <0.0001d | 8.26 (4.40–15.53) | <0.0001 |

| AFB1-albumin adduct levelc | ||||||

| Low and undetectable | 1475 (75.9) | 23 (52.3) | 1.00 (Referent) | 1.00 (Referent) | ||

| High | 468 (24.1) | 21 (47.7) | 2.88 (1.58–5.25) | 0.0006d | 2.43 (1.31–4.52) | 0.0051 |

1 control is missing for data of habitual cigarette smoking status.

4 controls are missing for data of habitual alcohol drinking status.

Low, <21.5 fmol/mg; high, ≥21.5 fmol/mg.

Variables with a p value less than 0.1 were included into the initial multiple logistic regression model for backward selection.

Stratification analyses by HCV infection were further carried out. In non-B-non-C participants, the association between the serum level of AFB1-albumin adducts and the risk of HCC developing within 8 years of follow-up was not statistically significant (Supplementary Table 1). However, elevated AFB1-albumin adduct levels were significantly associated with an increased risk of HCC in non-B-non-C participants with alcohol drinking habit [cOR (95% CI), 4.22 (1.16–15.37); p=0.029] but not in non-B-non-C participants without alcohol drinking habit [cOR, 0.92 (0.25–3.30); p=0.89] (Table 3). Habitual alcohol drinking seemed to be an effect modifier of AFB1 exposure for HCC. However, the interaction term was not statistically significant (p=0.10).

Table 3.

Association between AFB1 exposure and risk of hepatocellular carcinoma diagnosed within 8 years by habitual alcohol drinking status in participants without HBV and HCV infection (non-B-non-C)

| Control (%) (n=1767) | Case (%) (n=24) | Crude odds ratio (95% CI)c, d | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All non-B-non-C | ||||

| AFB1-albumin levela | ||||

| Low and undetectable | 1353 (76.6) | 15 (62.5) | 1.00 (Referent) | |

| High | 414 (23.4) | 9 (37.5) | 1.96 (0.85–4.51) | 0.11 |

|

| ||||

| No habitual alcohol drinkingb | ||||

| AFB1-albumin levela | ||||

| Low and undetectable | 1138 (77.1) | 11 (78.6) | 1.00 (Referent) | |

| High | 339 (23.0) | 3 (21.4) | 0.92 (0.25–3.30) | 0.89 |

|

| ||||

| Habitual alcohol drinkingb | ||||

| AFB1-albumin levela | ||||

| Low and undetectable | 211 (73.8) | 4 (40.0) | 1.00 (Referent) | |

| High | 75 (26.2) | 6 (60.0) | 4.22 (1.16–15.37)e | 0.029 |

Low, <21.5 fmol/mg; high, ≥21.5 fmol/mg.

4 controls are missing for data of habitual alcohol drinking status.

Measure of effect modification on additive scale: relative excess risk due to interaction (RERI) (95% CI), 6.40 (−1.51–14.30).

Measure of effect modification on multiplicative scale: p=0.1.

aOR (95% CI) = 5.60 (1.36–22.96) when adjusted for gender in HCV-uninfected participants with habitual alcohol consumption (p=0.0167).

Among the HCV-infected participants, controls and HCC cases diagnosed within 8 years of follow-up had similar distributions of age (mean ± standard deviation, 53.1 ± 7.8 vs. 56 ± 5.2; p=0.11) and gender (male, 64.8% vs. 70.0%; p=0.64). Table 4 shows crude and multivariate-adjusted ORs for risk predictors of HCC newly developed within 8 years of follow-up in HCV-infected participants. Obesity [cOR (95% CI), 5.07 (1.94–13.28); p=0.001], high serum levels of ALT [cOR (95% CI), 4.03 (1.50–10.83); p=0.0058] and AFB1-albumin adducts [cOR (95% CI), 3.39 (1.31–8.77); p=0.0118] were significantly associated with an increased risk of HCC. In the multivariate logistic regression model, high serum AFB1-albumin adduct levels were still significantly associated with an increased risk of HCC development [aOR (95% CI), 3.65 (1.32–10.10); p=0.0127] after adjustment for obesity and serum ALT level. Among chronic HCV carriers defined as HCV-infected participants with detectable serum levels of HCV RNA, high serum AFB1-albumin adduct level remained a risk predictor for newly-developed HCC [aOR (95% CI), 3.56 (1.11–11.41); p=0.0328] after adjustment for body mass index (Supplementary Table 2).

Table 4.

Crude and multivariate-adjusted odds ratios of risk predictors for hepatocellular carcinoma diagnosed within 8 years of follow-up in HCV-infected participants

| Baseline characteristics | Controls (%) (n=176) | HCC (%) (n=20) | Crude odds ratio (95% CI) | p value | Final multivariate model | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Adjusted odds ratio (95% CI) | p value | |||||

| Habitual cigarette smoking | ||||||

| No | 108 (61.4) | 9 (45.0) | 1.00 (Referent) | |||

| Yes | 68 (38.6) | 11 (55.0) | 1.94 (0.77–4.93) | 0.16 | (not included in model) | |

| Habitual alcohol drinking | ||||||

| No | 153 (86.9) | 18 (90.0) | 1.00 (Referent) | |||

| Yes | 23 (13.1) | 2 (10.0) | 0.74 (0.16–3.40) | 0.70 | (not included in model) | |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | ||||||

| <27 | 147 (83.5) | 10 (50.0) | 1.00 (Referent) | 1.00 (Referent) | ||

| ≥27 | 29 (16.5) | 10 (50.0) | 5.07 (1.94–13.28) | 0.001b | 4.96 (1.78–13.86) | 0.0023 |

| Serum ALT level (U/L) | ||||||

| <45 | 151 (85.8) | 12 (60.0) | 1.00 (Referent) | 1.00 (Referent) | ||

| ≥45 | 25 (14.2) | 8 (40.0) | 4.03 (1.50–10.83) | 0.0058b | 3.10 (1.07–8.96) | 0.0365 |

| AFB1-albumin adduct levela | ||||||

| Low and undetectable | 122 (69.3) | 8 (40.0) | 1.00 (Referent) | 1.00 (Referent) | ||

| High | 54 (30.7) | 12 (60.0) | 3.39 (1.31–8.77) | 0.0118b | 3.65 (1.32–10.10) | 0.0127 |

Low, <21.5 fmol/mg; high, ≥21.5 fmol/mg.

Variables with a p value less than 0.1 were included into the initial multiple logistic regression model for backward selection.

Discussion

In this case-control study nested in a large-scale community-based cohort, the participants were followed up for newly-developed HCC for 20 years. There were 100 and 103 new HCC cases in the non-B-non-C and HCV-infected participants, respectively. We found the follow-up time of newly-developed HCC was significantly shorter in participants with high levels of serum AFB1-albumin adducts than those with low/undetectable levels regardless of their HCV infection status. In our previous study in chronic HBV carriers, higher serum levels of AFB1-albumin adducts were significantly associated with more rapid development of cirrhosis and HCC [23]. With regard to the observed shorter follow-up time to diagnosis of HCC for cases with higher AFB1 exposure at study entry, it seems to suggest that AFB1 exposure may accelerate hepatocarcinogenesis resulting from both viral and non-viral etiology. More in vitro or animal studies will be needed to validate this hypothesis. Although the exact time at HCV infection was not known in this study, both HCV infection status and AFB1 exposure were tested at study entry. The follow-up time for the development of newly-diagnosed HCC was thus defined as the period from study entry to the diagnosis of HCC.

There was a trend of gradual decrease in odd ratios with time (data not shown) and significant dose-dependent associations between serum AFB1-albumin adducts levels with the risk of HCC until 8 years of follow-up, but not with HCC that developed later. The discrepancy may be due to following explanations: (1) A single measurement of serum AFB1-albumin adduct level at study entry may not accurately reflect the cumulative AFB1 exposure over a follow-up period longer than 8 years due to changes in dietary intake or other environmental exposures to AFB1. This limitation may be clarified by the repeated measurement of AFB1-albumin adduct levels in serial serum samples collected at different follow-up time points. (2) The hepatocarcinogenic effect of AFB1 may be more potent at the late stage of liver injury such as cirrhosis. AFB1 exposure at the early stage of liver injury may have less impact on the HCC development resulting from the repair of genetic damages induced by AFB1 by normal hepatocytes. (3) AFB1 exposure may accelerate the progression from chronic inflammation to cirrhosis and lead to the HCC development.

The serostatus of HBsAg and anti-HCV by the time of diagnosis was not recorded in the National Cancer Registry until recently. However, HBV infection was predominantly acquired through perinatal or horizontal transmission in the early childhood in Taiwan [24,25]. As all study participants were recruited into our cohort at the age of 30–65 at study entry in 1991–1992, there was a very small chance for these HCC cases who were HBsAg-seronegative at study entry and became HBsAg-seropositive by the time of diagnosis. As to the HCV infection, our previous study showed that the iatrogenic infection was the primary transmission route for HCV infection [18]. In addition, illicit drug use was infrequent in Taiwan [26,27], particularly in our study cohort recruited from agriculture/fishery townships. After the routine anti-HCV screening in blood donors in early 1990s, the transmission of HCV through blood transfusion has been substantially decreased [28]. Hence, the chance of HCV infection during the follow-up period for anti-HCV-seronegative participants would be very small. Using only the baseline serostatus of HBsAg and anti-HCV without the serostatus at the HCC diagnosis, if there were any serostatus change during the follow-up period, our estimates on the relative HCC risk would be underestimated due to the non-differential misclassification.

The incidence and etiologic factors of HCC vary with geographic location. Chronic HBV infection and AFB1 exposure are major risk factors in resource-constrained regions with a high HCC incidence, while chronic HCV infection is an important risk factor of HCC in the resource-rich regions with a low HCC incidence and low levels of dietary exposure to AFB1 [6]. There has been little focus on association between AFB1 exposure and HCC risk caused by HCV infection. However, there was a significant geographic overlap of aflatoxin exposure and HCV prevalence in Asia and Africa [29]. Hence, assessment of the effect of alfatoxin exposure on HCC in an HCV-infected population is needed. Current findings from limited studies are inconsistent and inconclusive. A positive geographical correlation was reported between prevalence of AFB1-contaminated foods and HCC incidence in HCV-infected patients [30]. But a clinical study in Japan indicated that the role of AFB1 in hepatocarcinogenesis was important in HBV-related and non-B-non-C HCC, but not in HCV-related HCC, showing a positive rate of AFB1-DNA adducts in hepatocytes of the liver of 10%, 16% and 0%, respectively [31]. A community-based case-control study in Taiwan suggested an association between AFB1 exposure and advanced liver disease (liver cirrhosis and HCC) in anti-HCV-seropositive patients [aOR (95% CI), 2.09 (1.09–4.0) for >8 versus ≤8 AFB1-albumin/albumin ratio] [32]. However, another case-control study in India reported a non-significant association between HCV-related HCC and presence of AFB-N7-guanine in urine [33]. The contradictory findings of these two case-control studies may be due to their small number of HCC cases and cross-sectional study design, in which HCC and AFB exposure were examined at the same time.

After ingestion, AFB1 is preliminarily metabolized by cytochrome P450 monooxygenase within the liver microsomes [34,35]. Several studies have shown altered expression of cytochrome P450s including the AFB1 metabolizing enzymes, CYP1A2 and CYP3A4, in patients with liver diseases [36–38]. In a cross-sectional study design, it is difficult to justify the causal temporality between the AFB1 exposure and HCC development because the measured levels of AFB1 metabolites may be affected by the severity of liver disease. In our present longitudinal study, the observed association between serum levels of AFB1-albumin adducts at study entry and risk of HCV-related HCC newly developed during the follow-up period of 8 years may provide stronger evidence for the causality of AFB1-induced HCC in participants with HCV infection.

Although the newly-developed HCC risk for participants with both high serum AFB1-albumin adduct levels and HCV infection (cOR=20.04) was much higher than those with high serum AFB1-albumin adduct levels only (cOR=1.96) and those with HCV infection only (cOR=5.91), the interaction between AFB1 exposure and HCV infection was not statistically significant. This may be partly due to the small number of HCC cases. The incidence of AFB1-induced liver tumors was higher and molecular changes including enhanced inflammatory response and altered lipid metabolism were more profound in HCV transgenic mice than wild-type mice [39]. These results indicate the co-carcinogenic effect of AFB1 and HCV. Potential molecular mechanisms underlying the synergistic interaction between hepatitis viruses and AFB1 have been proposed [40–43]. For example, reactive oxygen species generated during HBV or HCV infection are hypothesized to play a crucial role in the interaction between viral infection and AFB1 by allowing AFB1 to intercalate between the DNA strands with the hydroxyl radicals and lead to DNA damage [43]. Thus, more follow-up studies on a large number of newly-developed HCC cases are needed to elucidate the interactive effect on HCC between HCV infection and AFB1 exposure.

Another mechanism for the interaction between HBV and AFB1 in hepatocarcinogenesis was proposed [40,42]. Chronic HBV infection induces necroinflammation. Continuous cycles of hepatocyte destruction and regeneration ensued and reactive oxygen species generated both increase the likelihood of AFB1-associated promutagenic DNA lesions and selective clonal expansion of the initiated cells. As a result, accumulation of various genetic changes eventually lead to the development of HCC. Our previous study in this cohort showed that urinary AFB1 metabolites level was associated with the risk of HCC in carriers and non-carriers of HBV. In the present study limited to HBsAg-seronegative participants, elevated serum AFB1-albumin adduct level was associated with an increased risk of HCC in HCV-infected participants and non-B-non-C participants with alcohol drinking habit, but not in non-B-non-C participants without alcohol drinking habit. The findings from our community-based cohort demonstrate that individuals with HBV infection, HCV infection or habitual alcohol drinking are much more susceptible to AFB1-associated HCC risk compared to those without these etiological factors. As chronic HCV infection and alcohol drinking habit may also induce chronic inflammation and cause liver injury [44], it is possible that HCV and alcohol consumption modify the hepatocarcinogenic effect of AFB1 via the increased hepatocyte vulnerability to AFB1-induced DNA damage and mutations. Besides hepatitis viruses and alcohol, diabetes and non-alcoholic fatty liver diseases (NAFLD) have also been shown to cause liver injury and contribute to HCC development [44]. It will be interesting to investigate whether the individuals having diabetes or NAFLD are predisposed to AFB1-associated hepatocarcinogenesis in the future.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Effect of AFB1 in HCV-related and non-viral HCC has rarely been studied.

AFB1 increases HCC risk in participants with habitual alcohol drinking and HCV infection.

The follow-up time to HCC diagnosis was significantly shorter in participants with higher AFB1 exposure.

Acknowledgments

Role of the funding source

Analysis of aflatoxin B1-albumin adduct levels was supported by National Institutes of Health [grant numbers: RO1ES005116 and P30ES009089; PI: Regina Santella].

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C, Rebelo M, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer. 2015;136:E359–86. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, Ferlay J, Lortet-Tieulent J, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65:87–108. doi: 10.3322/caac.21262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.El-Serag HB. Epidemiology of viral hepatitis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:1264–73. e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.12.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wild CP, Turner PC. The toxicology of aflatoxins as a basis for public health decisions. Mutagenesis. 2002;17:471–81. doi: 10.1093/mutage/17.6.471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cullen JM, Newberne PM. Acute hepatotoxicity of aflatoxins. In: Eaton DL, Groopman JD, editors. The toxicology of aflatoxins: human health, veterinary, and agricultural significance. London: Academic Press; 1993. pp. 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kew MC. Hepatocellular carcinoma: epidemiology and risk factors. J Hepatocell Carcinoma. 2014;1:115–25. doi: 10.2147/JHC.S44381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu Y, Wu F. Global burden of aflatoxin-induced hepatocellular carcinoma: a risk assessment. Environ Health Perspect. 2010;118:818–24. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0901388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sabbioni G, Skipper PL, Buchi G, Tannenbaum SR. Isolation and characterization of the major serum albumin adduct formed by aflatoxin B1 in vivo in rats. Carcinogenesis. 1987;8:819–24. doi: 10.1093/carcin/8.6.819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu HC, Santella R. The role of aflatoxins in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepat Mon. 2012;12:e7238. doi: 10.5812/hepatmon.7238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ross RK, Yuan JM, Yu MC, Wogan GN, Qian GS, Tu JT, et al. Urinary aflatoxin biomarkers and risk of hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet. 1992;339:943–6. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)91528-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang LY, Hatch M, Chen CJ, Levin B, You SL, Lu SN, et al. Aflatoxin exposure and risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in Taiwan. Int J Cancer. 1996;67:620–5. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19960904)67:5<620::AID-IJC5>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu HC, Wang Q, Yang HI, Ahsan H, Tsai WY, Wang LY, et al. Aflatoxin B1 exposure, hepatitis B virus infection, and hepatocellular carcinoma in Taiwan. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18:846–53. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Qian GS, Ross RK, Yu MC, Yuan JM, Gao YT, Henderson BE, et al. A follow-up study of urinary markers of aflatoxin exposure and liver cancer risk in Shanghai, People’s Republic of China. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1994;3:3–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kensler TW, Roebuck BD, Wogan GN, Groopman JD. Aflatoxin: a 50-year odyssey of mechanistic and translational toxicology. Toxicol Sci. 2011;120(Suppl 1):S28–48. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfq283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wogan GN, Kensler TW, Groopman JD. Present and future directions of translational research on aflatoxin and hepatocellular carcinoma. A review. Food Addit Contam Part A Chem Anal Control Expo Risk Assess. 2012;29:249–57. doi: 10.1080/19440049.2011.563370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scholl PF, Groopman JD. Long-term stability of human aflatoxin B1 albumin adducts assessed by isotope dilution mass spectrometry and high-performance liquid chromatography-fluorescence. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17:1436–9. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-2926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee MH, Yang HI, Yuan Y, L’Italien G, Chen CJ. Epidemiology and natural history of hepatitis C virus infection. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:9270–80. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i28.9270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sun CA, Chen HC, Lu CF, You SL, Mau YC, Ho MS, et al. Transmission of hepatitis C virus in Taiwan: prevalence and risk factors based on a nationwide survey. J Med Virol. 1999;59:290–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen CJ, Wang LY, Lu SN, Wu MH, You SL, Zhang YJ, et al. Elevated aflatoxin exposure and increased risk of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 1996;24:38–42. doi: 10.1002/hep.510240108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li KC, Li HP, Wong SS, Chuang YS. Survey of aflatoxin contaminations in peanuts from various areas in Taiwan. Taichung: Taiwan Agricultural Chemical and Toxic Substances Research Institute; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee MH, Yang HI, Jen CL, Lu SN, Yeh SH, Liu CJ, et al. Community and personal risk factors for hepatitis C virus infection: a survey of 23,820 residents in Taiwan in 1991–2. Gut. 2011;60:688–94. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.220889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wild CP, Jiang YZ, Sabbioni G, Chapot B, Montesano R. Evaluation of methods for quantitation of aflatoxin-albumin adducts and their application to human exposure assessment. Cancer Res. 1990;50:245–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chu YJ, Yang HI, Wu HC, Liu J, Wang LY, Lu SN, et al. Aflatoxin B1 exposure increases the risk of cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma in chronic hepatitis B virus carriers. Int J Cancer. 2017;141:711–20. doi: 10.1002/ijc.30782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beasley RP, Trepo C, Stevens CE, Szmuness W. The e antigen and vertical transmission of hepatitis B surface antigen. Am J Epidemiol. 1977;105:94–8. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McMahon BJ, Alward WL, Hall DB, Heyward WL, Bender TR, Francis DP, et al. Acute hepatitis B virus infection: relation of age to the clinical expression of disease and subsequent development of the carrier state. J Infect Dis. 1985;151:599–603. doi: 10.1093/infdis/151.4.599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen KT, Chen CJ, Fagot-Campagna A, Narayan KM. Tobacco, betel quid, alcohol, and illicit drug use among 13- to 35-year-olds in I-Lan, rural Taiwan: prevalence and risk factors. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:1130–4. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.7.1130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chiang SC, Chen CY, Chang YY, Sun HJ, Chen WJ. Prevalence of heroin and methamphetamine male users in the northern Taiwan, 1999–2002: capture-recapture estimates. BMC Public Health. 2007;7:292. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-7-292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang JT, Wang TH, Lin JT, Lee CZ, Sheu JC, Chen DS. Effect of hepatitis C antibody screening in blood donors on post-transfusion hepatitis in Taiwan. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1995;10:454–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.1995.tb01599.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Palliyaguru DL, Wu F. Global geographical overlap of aflatoxin and hepatitis C: controlling risk factors for liver cancer worldwide. Food Addit Contam Part A Chem Anal Control Expo Risk Assess. 2013;30:534–40. doi: 10.1080/19440049.2012.751630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hifnawy MS, Mangoud AM, Eissa MH, Nor Edin E, Mostafa Y, Abouel-Magd Y, et al. The role of aflatoxin-contaminated food materials and HCV in developing hepatocellular carcinoma in Al-Sharkia Governorate, Egypt. J Egypt Soc Parasitol. 2004;34:479–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shirabe K, Toshima T, Taketomi A, Taguchi K, Yoshizumi T, Uchiyama H, et al. Hepatic aflatoxin B1-DNA adducts and TP53 mutations in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma despite low exposure to aflatoxin B1 in southern Japan. Liver Int. 2011;31:1366–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2011.02572.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen CH, Wang MH, Wang JH, Hung CH, Hu TH, Lee SC, et al. Aflatoxin exposure and hepatitis C virus in advanced liver disease in a hepatitis C virus endemic area in Taiwan. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2007;77:747–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Asim M, Sarma MP, Thayumanavan L, Kar P. Role of aflatoxin B1 as a risk for primary liver cancer in north Indian population. Clin Biochem. 2011;44:1235–40. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2011.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gallagher EP, Kunze KL, Stapleton PL, Eaton DL. The kinetics of aflatoxin B1 oxidation by human cDNA-expressed and human liver microsomal cytochromes P450 1A2 and 3A4. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1996;141:595–606. doi: 10.1006/taap.1996.0326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ueng YF, Shimada T, Yamazaki H, Guengerich FP. Oxidation of aflatoxin B1 by bacterial recombinant human cytochrome P450 enzymes. Chem Res Toxicol. 1995;8:218–25. doi: 10.1021/tx00044a006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fisher CD, Lickteig AJ, Augustine LM, Ranger-Moore J, Jackson JP, Ferguson SS, et al. Hepatic cytochrome P450 enzyme alterations in humans with progressive stages of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Drug Metab Dispos. 2009;37:2087–94. doi: 10.1124/dmd.109.027466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Frye RF, Zgheib NK, Matzke GR, Chaves-Gnecco D, Rabinovitz M, Shaikh OS, et al. Liver disease selectively modulates cytochrome P450--mediated metabolism. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2006;80:235–45. doi: 10.1016/j.clpt.2006.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yan T, Lu L, Xie C, Chen J, Peng X, Zhu L, et al. Severely Impaired and Dysregulated Cytochrome P450 Expression and Activities in Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Implications for Personalized Treatment in Patients. Mol Cancer Ther. 2015;14:2874–86. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-15-0274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jeannot E, Boorman GA, Kosyk O, Bradford BU, Shymoniak S, Tumurbaatar B, et al. Increased incidence of aflatoxin B1-induced liver tumors in hepatitis virus C transgenic mice. Int J Cancer. 2012;130:1347–56. doi: 10.1002/ijc.26140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kew MC. Synergistic Interaction Between Aflatoxin and Hepatitis B Virus in Hepatocarcinogenesis. In: Mehdi R-A, editor. Aflatoxins - Recent Advances and Future Prospects. InTech; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Moudgil V, Redhu D, Dhanda S, Singh J. A review of molecular mechanisms in the development of hepatocellular carcinoma by aflatoxin and hepatitis B and C viruses. J Environ Pathol Toxicol Oncol. 2013;32:165–75. doi: 10.1615/jenvironpatholtoxicoloncol.2013007166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wild CP, Montesano R. A model of interaction: aflatoxins and hepatitis viruses in liver cancer aetiology and prevention. Cancer Lett. 2009;286:22–8. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2009.02.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mossanda KS. Hepatocellular carcinoma: Putative interactive mechanism between aflatoxins and hepatitis viral infections implicating oxidative stress during the onset and progression of cance. Hypothesis. 2015:13. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Farazi PA, DePinho RA. Hepatocellular carcinoma pathogenesis: from genes to environment. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:674–87. doi: 10.1038/nrc1934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.