Abstract

Youth living with HIV in sub-Saharan Africa face numerous challenges in adhering to HIV treatment. The AIDS epidemic has left many of these youth orphaned due to AIDS-related death of one or both parents. It is imperative to understand the family context of youth living with HIV in order to develop responsive interventions to improve adherence to antiretroviral therapy. We conducted qualitative in-depth interviews with 17 HIV-infected AIDS orphans, ages 13–24 years, screened positive for mental health difficulties according to the Patient Health Questionaire-9 (PHQ-9) or UCLA PTSD Reaction Index (PTSD-RI), and receiving outpatient HIV care at an adolescent medical clinic in Moshi, Tanzania. Treatment-related support varied by orphan status. Paternal orphans cared for by their biological mothers and maternal orphans cared for by grandmothers described adherence support such as assistance taking medication and attending clinic. Double orphans did not report adherence support. Several maternal and double orphans faced direct interference from caregivers and household members when they attempted to take their medications. Caregivers play a significant role in treatment adherence and must be considered in interventions to increase medication adherence in HIV-infected orphans. Findings from this study informed caregiver participation in Sauti ya Vijana (The Voice of Youth), a mental health intervention for youth living with HIV in Tanzania.

Keywords: HIV-infected, AIDS orphan, adolescent, medication adherence, caregiver

Introduction

HIV-infected AIDS orphans in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) are vulnerable to delays in HIV treatment initiation (Ntanda et al., 2009) and medication non-adherence (Kikuchi et al., 2012; R. Vreeman, Wiehe, Ayaya, Musick, & Nyandiko, 2008), which can result in virologic failure and drug resistance (Bezabhe, Chalmers, Bereznicki, & Peterson, 2016; WHO, CDC, & Fund, 2017). With one or both parents deceased, HIV-infected orphans are often cared for by extended family members or siblings (Beegle, Filmer, Stokes, & Tiererova, 2010), who themselves often face a myriad of challenges. Many who take in orphaned children report stress and inadequacy in providing for the child and may express anger towards the child (Kidman & Thurman, 2014). A review of qualitative studies on child abuse and neglect found that orphans cared for by extended family members in SSA reported experiences including: intra-household stigma and discrimination, material and educational neglect, exploitation, and physical, psychological, and sexual abuse (Morantz et al., 2013). Maltreatment, including neglect, increases adolescents’ risk of mental health problems (Whetten et al., 2011). Adolescents living with HIV (ALHIV) in SSA exhibit high rates of mental health distress including symptoms of depression (Kamau, Kuria, Mathai, Atwoli, & Kangethe, 2012) that negatively impact antiretroviral therapy (ART) adherence (Dow et al., 2016; Uthman, Magidson, Safren, & Nachega, 2014).

Understanding the lived experiences of orphaned ALHIV is critical to inform the development of relevant and effective interventions to promote treatment adherence. Recent studies on the barriers to and facilitators of adherence among ALHIV have been primarily conducted with caregivers or child/caregiver dyads (Busza, Dauya, Bandason, Mujuru, & Ferrand, 2014; Denison et al., 2015; Kikuchi et al., 2014). Researching adherence from this perspective may bias results and reduce transparency of adherence barriers due to a caregiver or household member. The aim of this study was to explore the role of caregivers in ART adherence support from the perspective of HIV-infected orphans in Tanzania to inform a mental health and adherence intervention designed specifically for ALHIV.

Methods

Study Design

The data reported here were part of a mixed-methods project examining mental health difficulties among ALHIV, 12–24 years of age, attending Kilimanjaro Christian Medical Center (KCMC) in Moshi, Tanzania (Dow et al., 2016; Ramaiya et al., 2016). A convenience sample from the quantitative study participated in qualitative interviews. In order to explore the synergy between orphan status, mental health difficulties, and medication adherence, this sub-analysis included adolescents who were: single or double orphans reporting death of one or both biological parents; ages 13–24 years; prescribed ART; screened positive for mental health difficulties on the quantitative structured survey (Patient Health Questionaire-9 (PHQ-9) score ≥ 10 or UCLA PTSD Reaction Index (PTSD-RI) score ≥ 18 on a modified 4-point Likert scale); and perinatally HIV-infected. Perinatal HIV acquisition was defined as age of HIV diagnosis or ART start date (retrospective chart review) prior to 13 years of age, or documentation that the youth’s mother died because of HIV. Age of HIV disclosure is based on self-report from the quantitative structured survey (Ramos et al., 2017).

Procedures

In-depth interviews were conducted in Swahili in a private room at KCMC. Four English-Swahili bilingual KCMC healthcare staff with training in qualitative research methods completed interviews. The semi-structured interview guide was developed through a literature review of psychosocial issues impacting ALHIV in SSA and consultation with Tanzanian and American medical professionals. The guide was developed in English, translated into Swahili, and then back translated into English. Interview topics included: psychosocial risk and protective factors, mental health symptomatology, and barriers and facilitators to ART adherence (Ramaiya et al., 2016).

Data Analysis

Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim in Swahili, translated into English, and reviewed for accuracy. QSR NVivo software version 10.0 was used for data management and analysis. The qualitative analytic approach was informed by thematic analysis (Guest, MacQueen, & Namey, 2011). Two researchers conducted a deep review of the transcripts and developed the codebook, which was revised as the understanding of the data was refined. When the codebook was finalized, 20% of the transcripts were double coded, with discrepancies discussed until consensus between the researchers was reached. Themes were compared across transcripts to elicit salient patterns. Matrices were developed to stratify results by orphan status and to explore the role of caregiver support and/or interference with ART adherence among ALHIV.

Ethics

This study was approved by the Duke University Medical Center Institutional Review Board, the KCMC Research Ethics Committee, and the Tanzanian National Research Ethics Committee. Participants age 18 years and over provided informed consent. Youth under 18 years of age provided assent, and their guardian provided informed consent.

Results

Participants

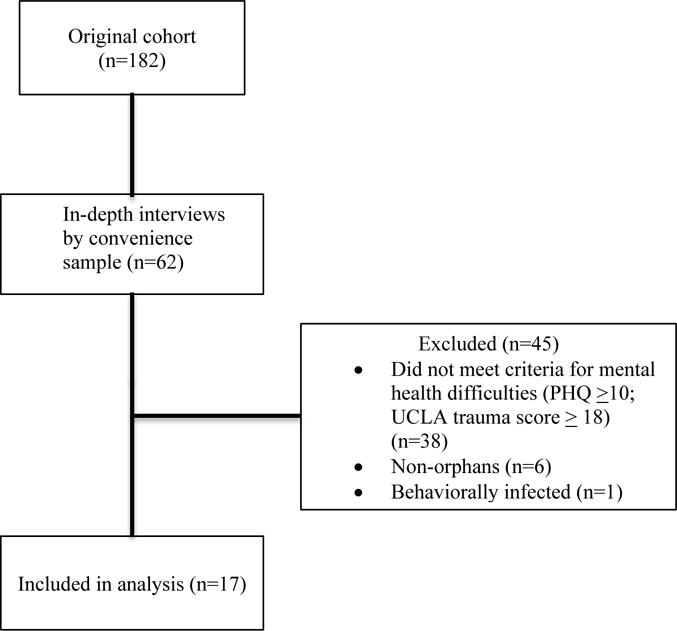

Seventeen adolescents met inclusion criteria and were included in analyses (Figure 1). The mean age was 19 years and the majority of adolescents were female (n=13) (Table 1). The sample was distributed between paternal (n=6), maternal (n=7), and double (n=4) orphans.

Figure 1.

Cohort flow diagram

Table 1.

Characteristics of study participants (N=17)

| Orphan Status* | Total N (%) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal (N= 7) |

Paternal (N=6) |

Double (N=4) |

|||

| Sex | Male | 2 | 2 | – | 4 (24) |

| Female | 5 | 4 | 4 | 13 (76) | |

| Age (years) | 13–19 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 12 (71) |

| 20–24 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 5 (19) | |

| Caregiver | Mother | – | 4 | – | 4 (24) |

| Father | 1 | – | – | 1 (6) | |

| Aunt/Uncle | 2 | 1 | 2 | 5 (29) | |

| Grandmother | 3 | 1 | – | 4 (24) | |

| Sibling | 1 | – | 2 | 3 (17) | |

| Mean age at time of interview (years) | 20.5 (3.3) | 16.8 (3.8) | 19.0 (3.1) | 19.0 (3.4) | |

| Mean age at HIV diagnosis (years) | 12.4 (2.7) | 10.1 (4.0) | 9.2 (6.3) | 10.7 (4.4) | |

| Mean age at self-reported disclosure (years) | 12.8 (1.5) | 11.0 (3.6) | 9.9 (4.8) | 11.3 (3.4) | |

| Mean age at ART initiation (years) | 12.9 (2.1) | 10.4 (4.4) | 9.7 (6.7) | 11.2 (4.5) | |

Maternal orphan, biologic mother died; Paternal orphan, biologic father died; Double orphan, both biologic parents are dead

Caregiver support

Caregiver adherence support varied by orphan status. All paternal orphans living with their mothers described receiving some form of support, with most reporting that their mothers provided direct assistance in taking medications and attending clinic (Table 2). Mothers of paternal orphans were also living with HIV, which suggests they may be empathetic about their child’s HIV status and motivated to help with treatment adherence. They may also remember a time when ART was not available and value access to the medication that has helped keep them and their children alive.

Table 2.

Caregiver support and interference regarding experience with ART adherence

| Orphan experience | |

|---|---|

| Caregiver support |

I: Do you face any difficulties when taking your drugs? P: I am so secretive when taking my drugs. They are always on my handbag and we will be sitting all the three of us. Me, my mother and my young brother have to take our drugs together. I: Your young brother also has HIV? P: Yes, so when we are ready to take them and then we hear a knock on the door, my mother will go on the door and talk to that person while I keep taking out the drugs so that we will take them on time. – Paternal Orphan, 16 years old |

| Caregiver interference |

I: What made you stop using these drugs? P: Things that my step-mother used to say. I used to have drugs that were supposed to be stored in a refrigerator so she used to tell me “take those drugs out of the refrigerator before you kill my children, if you will die just go meet your mother but don’t kill my children” – Maternal Orphan, 22 years old P: Sometimes I would want to take my drugs but then stop taking and think it will be best if I die because I don’t know how my life will be in this world, people treat me like I am nothing and most of the time they refuse to even give me food.” – Maternal Orphan, 16 years old P: One day she [sister] throw them [HIV medication] outside, I told her I am going somewhere but I didn’t know that she didn’t want me to go when I came back she told me to go back to where I am coming from and she took all the drugs and thrown them outside, I had to pick them up and put them in a plastic bag. – Double Orphan, 19 years old |

Maternal and double orphans reported limited adherence support from caregivers. Only one maternal orphan (18 years old) reported treatment support. She stated that her grandmother assisted her by reminding her to take her medication. No double orphans reported receiving any adherence support from guardians.

Caregiver interference

Despite reports of caregiver support, a third of participants (n=6) responded that caregivers or household members either directly or indirectly interfered with their ART adherence. Table 2 includes a quote from a maternal orphan whose stepmother banned her from storing her medication in the refrigerator. The stepmother’s actions and hurtful statements imply potential ignorance and fear regarding the medications. This quote exemplifies stigmatizing behaviors that interfered with ART adherence and may have made the medication ineffective due to lack of refrigeration. A 16-year old maternal orphan reported that her grandmother expressed indifference in her medication use and refused to give her food to take with her medication. She described how the poor treatment from her grandmother, and others, led her to stop taking her medication (Table 2). One other maternal orphan (17 years old), also mentioned that his caregiver withheld food, but he did not indicate that this affected his adherence.

Double orphans stated they were non-adherent because their caregivers refused to give them sufficient transport funds to retrieve their medication from the medical center. Additionally, one double orphan cared for by a sister recalled how her sister threw her medication outside the home (Table 2). The public display placed the adolescent at risk of inadvertent disclosure to neighbors as well as missing doses of her ART medication. No paternal orphans described interference from caregivers that affected their treatment adherence.

Discussion

This study illustrates the complexities surrounding treatment adherence among orphaned ALHIV in Tanzania. Medication interference, to our knowledge, has not been previously reported in the context of ART adherence in orphaned ALHIV, and these findings highlight the extreme challenges faced by some youth. Caregivers and household members appear to play a pivotal role in supporting or hindering medication use.

Medication interference was reported by maternal and double orphans. Participants reported caregiver actions including: barring medication storage, disposing medications, and withholding transport money and food. Such actions suggest HIV-related stigma in the form of negative treatment and denial of resources that enable adherence. Expressed stigma from caregivers of HIV-infected children is associated with lesser knowledge about the care and support needs of HIV-infected children (Hamra, Ross, Karuri, Orrs, & D’Agostino, 2005) which could lead to interference. High levels of external stigma from family members and others has been previously reported for this cohort of ALHIV receiving services from KCMC (Dow et al., 2016; Ramaiya et al., 2016). Mental health difficulties are often associated with both increased stigma (Cluver & Orkin, 2009; Dow et al., 2016) and increased rates of ART non-adherence (Rueda et al., 2016); thus the combination of stigma, mental health difficulties, and orphan status make this population especially vulnerable to non-adherence indicating the need for larger family system assessment, education, engagement of caregivers and household members, and creative alternative medication adherence strategies when family approaches are not feasible.

Congruent with prior research, caregiver support, particularly from mothers, was instrumental in treatment maintenance (Kikuchi et al., 2012). One adolescent reported that she maintained adherence because she took her medications with her mother and sibling. This is particularly important, as studies indicate that caregiver’s non-adherence and poor physical health, may negatively influence child adherence (Ricci, Netto, Luz, Rodamilans, & Brites, 2016; R. C. Vreeman et al., 2009; Williams et al., 2006; Wrubel et al., 2005). While we did not collect information on mother’s treatment adherence, this finding suggests the importance of assessing and targeting HIV-positive caregiver’s adherence in order to improve adolescent’s adherence. Notably, double orphans did not report any direct adherence support, which indicates they may need to cultivate support from other sources.

Findings from this study informed the creation of Sauti ya Vijana (The Voice of Youth), a mental health intervention for ALHIV (NCT02888288). The ten-session program includes two joint caregiver sessions and two individual sessions with home visits using principles of cognitive behavioral therapy, interpersonal psychotherapy, and motivational interviewing. Sessions focus on encouraging caregivers to listen to youth’s experiences with a goal of promoting dialogue about stigma, disclosure, ART adherence, and challenges they face. Improving adolescent mental health and social support from caregivers and household members has the potential to improve ART adherence and the lives of ALHIV.

Limitations

This study had several limitations. The small convenience sample was recruited within an established HIV adolescent clinic, which increases the possibility that youth were engaged in care despite challenges faced from unsupportive caregivers. Our sample was majority female and included a wide age range of adolescents. Caregivers of older adolescents (ages 20–24) may not expect to provide treatment support. However, other research shows that adolescents ages 15–24 are more likely to have an unsuppressed viral load compared to children and adults (Evans et al., 2013), suggesting this group is at high risk of adherence difficulties and may still need treatment support. Finally, our sample only included youth reporting mental health difficulties who are more likely to experience challenges with family or caregivers and ART adherence difficulties.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This research was supported by the Duke University Center for AIDS Research (CFAR), an NIH funded program (P30 AI064518), the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) training grant to the Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Pediatrics, Duke University Medical Center (T32 HD060558) and by NIH Research Training Grant R25 TW009337 and International Scientist Research Development Award (K01 TW-009985) funded by the Fogarty International Center and the National Institute of Mental Health (to DED). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Disclosure statement: The authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

References

- Beegle K, Filmer D, Stokes A, Tiererova L. Orphanhood and the living arrangements of children in sub-Saharan Africa. World Development. 2010;38(12):1727–1746. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2010.06.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bezabhe WM, Chalmers L, Bereznicki LR, Peterson GM. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy and virologic failure: A meta-analysis. Medicine. 2016;95(15):e3361. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000003361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busza J, Dauya E, Bandason T, Mujuru H, Ferrand RA. “I don’t want financial support but verbal support.” How do caregivers manage children’s access to and retention in HIV care in urban Zimbabwe? Journal of the International AIDS Society. 2014;17(1) doi: 10.7448/IAS.17.1.18839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cluver L, Orkin M. Cumulative risk and AIDS-orphanhood: Interactions of stigma, bullying and poverty on child mental health in South Africa. Social science & medicine. 2009;69(8):1186–1193. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.07.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denison JA, Banda H, Dennis AC, Packer C, Nyambe N, Stalter RM, McCarraher DR. “The sky is the limit”: Adhering to antiretroviral therapy and HIV self-management from the perspectives of adolescents living with HIV and their adult caregivers. Journal of the International AIDS Society. 2015;18(1) doi: 10.7448/IAS.18.1.19358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dow DE, Turner EL, Shayo AM, Mmbaga B, Cunningham CK, O’Donnell K. Evaluating mental health difficulties and associated outcomes among HIV-positive adolescents in Tanzania. AIDS Care. 2016;28(7):825–833. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2016.1139043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans D, Menezes C, Mahomed K, Macdonald P, Untiedt S, Levin L, Maskew M. Treatment outcomes of HIV-infected adolescents attending public-sector HIV clinics across Gauteng and Mpumalanga, South Africa. AIDS Research and Human Retroviruses. 2013;29(6):892–900. doi: 10.1089/AID.2012.0215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guest G, MacQueen KM, Namey EE. Applied thematic analysis. Sage; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hamra M, Ross MW, Karuri K, Orrs M, D’Agostino A. The relationship between expressed HIV/AIDS-related stigma and beliefs and knowledge about care and support of people living with AIDS in families caring for HIV-infected children in Kenya. AIDS Care. 2005;17(7):911–922. doi: 10.1080/09540120500100593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamau JW, Kuria W, Mathai M, Atwoli L, Kangethe R. Psychiatric morbidity among HIV-infected children and adolescents in a resource-poor Kenyan urban community. AIDS Care. 2012;24(7):836–842. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2011.644234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kidman R, Thurman TR. Caregiver burden among adults caring for orphaned children in rural South Africa. Vulnerable Child Youth Studies. 2014;9(3):234–246. doi: 10.1080/17450128.2013.871379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kikuchi K, Poudel KC, Muganda J, Majyambere A, Otsuka K, Sato T, Yasuoka J. High risk of ART non-adherence and delay of ART initiation among HIV positive double orphans in Kigali, Rwanda. PLoS One. 2012;7(7):e41998. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0041998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kikuchi K, Poudel KC, Muganda J, Sato T, Mutabazi V, Muhayimpundu R, Jimba M. What makes orphans in Kigali, Rwanda, non-adherent to antiretroviral therapy? Perspectives of their caregivers. Journal of the International AIDS Society. 2014;17:19310. doi: 10.7448/IAS.17.1.19310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morantz G, Cole D, Vreeman R, Ayaya S, Ayuku D, Braitstein P. Child abuse and neglect among orphaned children and youth living in extended families in sub-Saharan Africa: What have we learned from qualitative inquiry? Vulnerable Child Youth Studies. 2013;8(4):338–352. doi: 10.1080/17450128.2013.764476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ntanda H, Olupot-Olupot P, Mugyenyi P, Kityo C, Lowes R, Cooper C, Mills E. Orphanhood predicts delayed access to care in Ugandan children. The Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal. 2009;28(2):153–155. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e318184eeeb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramaiya MK, Sullivan KA, K OD, Cunningham CK, Shayo AM, Mmbaga BT, Dow DE. A qualitative exploration of the mental health and psychosocial contexts of HIV-positive adolescents in Tanzania. PLoS One. 2016;11(11):e0165936. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0165936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos J, Rugulabamu L, Luhanga S, Mmbaga B, Cunningham CK, Dow DE. Modality of primary HIV disclosure and association with mental health, stigma, and antiretroviral therapy adherence in Tanzanian youth living with HIV. Pediatric Academic Society; San Francisco, CA: 2017. May 6–9, [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricci G, Netto EM, Luz E, Rodamilans C, Brites C. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy of Brazilian HIV-infected children and their caregivers. The Brazilian Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2016;20(5):429–436. doi: 10.1016/j.bjid.2016.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rueda S, Mitra S, Chen S, Gogolishvili D, Globerman J, Chambers L, Rourke SB. Examining the associations between HIV-related stigma and health outcomes in people living with HIV/AIDS: a series of meta-analyses. BMJ Open. 2016;6(7):e011453. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uthman OA, Magidson JF, Safren SA, Nachega JB. Depression and adherence to antiretroviral therapy in low-, middle-and high-income countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Current HIV/AIDS Reports. 2014;11(3):291–307. doi: 10.1007/s11904-014-0220-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vreeman R, Wiehe S, Ayaya S, Musick B, Nyandiko W. Association of Antiretroviral and Clinic Adherence With Orphan Status Among HIV-Infected Children in Western Kenya. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2008;49(2):163–170. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318183a996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vreeman RC, Nyandiko WM, Ayaya SO, Walumbe EG, Marrero DG, Inui TS. Factors sustaining pediatric adherence to antiretroviral therapy in western Kenya. Qualitative Health Research. 2009;19(12):1716–1729. doi: 10.1177/1049732309353047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whetten K, Ostermann J, Whetten R, O’Donnell K, Thielman N, Positive Outcomes for Orphans Research, T More than the loss of a parent: potentially traumatic events among orphaned and abandoned children. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2011;24(2):174–182. doi: 10.1002/jts.20625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO, CDC, & The Global Fund. HIV drug resistance report 2017. 2017 Retrieved from http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/drugresistance/hivdr-report-2017/en/

- Williams PL, Storm D, Montepiedra G, Nichols S, Kammerer B, Sirois PA, Team, P. C. Predictors of adherence to antiretroviral medications in children and adolescents with HIV infection. Pediatrics. 2006;118(6):e1745–1757. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-0493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wrubel J, Moskowitz JT, Richards TA, Prakke H, Acree M, Folkman S. Pediatric adherence: perspectives of mothers of children with HIV. Social Science & Medicine. 2005;61(11):2423–2433. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.04.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]