Abstract

The development of three-dimensional culture methods has allowed for the study of developing cortical morphology in human cells. This provides a new tool to study the neurodevelopmental consequences of disease-associated mutations. Here, we study the effects of isogenic DISC1 mutation in cerebral organoids. DISC1 has been implicated in psychiatric disease based on genetic studies, including its interruption by a balanced translocation that increases the risk of major mental illness. Isogenic wild-type and DISC1-disrupted human-induced pluripotent stem cells were used to generate cerebral organoids, which were then examined for morphology and gene expression. We show that DISC1-mutant cerebral organoids display disorganized structural morphology and impaired proliferation, which is phenocopied by WNT agonism and rescued by WNT antagonism. Furthermore, there are many shared changes in gene expression with DISC1 disruption and WNT agonism, including in neural progenitor and cell fate markers, regulators of neuronal migration, and interneuron markers. These shared gene expression changes suggest mechanisms for the observed morphologic dysregulation with DISC1 disruption and points to new avenues for future studies. The shared changes in three-dimensional cerebral organoid morphology and gene expression with DISC1 interruption and WNT agonism further strengthens the link between DISC1 mutation, abnormalities in WNT signaling, and neuropsychiatric disease.

Introduction

Modeling human neurodevelopment is a challenging but essential undertaking for addressing the cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying certain psychiatric diseases. Recent progress in human stem cell technologies allow us to examine developmental processes in human neural cells in a well-controlled system1. Induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) have been derived from patients suffering from a variety of psychiatric diseases, and advances in genome engineering allow for efficient introduction and correction of genetic lesions that increase risk for disease. A number of differentiation protocols exist for directing stem cells to neuronal and astrocyte fates found along the neuraxis, with both monolayer and three-dimensional culture models available. These complementary methods have the potential to provide insights into the effects of gene disruption on neurodevelopmental processes.

Numerous laboratories have optimized monolayer differentiation protocols that efficiently generate neuronal cultures of a variety of fates. The use of these protocols is highly valuable and often essential if consistent and robust phenotypes are to be identified. However, a drawback of these cultures is that certain neurodevelopmental processes can only be examined in a three-dimensional (3D) environment more similar to in vivo development. To study human neurodevelopmental processes in a 3D structure, protocols have been developed to create cerebral organoids from embryonic stem cells and iPSCs2–6. Human stem cells are grown in aggregates, directed to a neural lineage via changes in media composition, and agitated in a spinning bioreactor to allow continued growth of organoids in 3D. Aggregates grow and develop over time, and can be cultured long term for greater than a year. These organoid cultures recapitulate aspects of neurodevelopment that cannot be examined in monolayer cultures. Such protocols are particularly valuable for studying windows of early cortical development such as the formation of certain progenitor zones and the migration of postmitotic precursor cells to recapitulate the inside–out development of cortical layers. Although protocols often result in a high level of variability between organoids, it is possible to identify morphological and regional differences between organoids when a strong genetic and/or pharmacological perturbation is introduced.

We previously have described the generation and characterization of an isogenic hiPSC model with disruption of the gene DISC1 (Disrupted-in-Schizophrenia 1), a gene linked to elevated risk of mental illness7. DISC1 was identified as a gene disrupted by a balanced translocation that increased risk for mental illness in a large Scottish family8. In our study, we showed that disruption of the gene at the site of the balanced translocation resulted in a loss of long DISC1 isoforms, a reduction in the production of TBR2+ neural progenitor cells, and an elevation of baseline WNT signaling7. Early steps of the differentiation protocol employed in that study included the formation of 3D embryoid aggregates, but all data analyses were performed at later stages when cells were plated under monolayer conditions. Here, to better examine the morphological and molecular consequences of DISC1 disruption in a 3D structure, we generated and analyzed cerebral organoids from isogenic hiPSCs with and without DISC1 mutation.

We show that cerebral organoids with DISC1 disruption are morphologically distinct from wild-type organoids. A few weeks after formation, wild-type cerebral organoids display well-defined rosette and ventricle-like structures that contain mitotic neural progenitor cells (NPCs) expressing PAX6 and TBR2. In contrast, cerebral organoids from DISC1-disrupted cells display smaller, disorganized rosette structures. Interestingly, wild-type organoids treated with a WNT agonist appear morphologically similar to DISC1-disrupted organoids, and WNT antagonism rescues the phenotype of DISC1-mutant organoids. DISC1-mutant organoids show a reduction in NPC proliferation, which is rescued by treatment with a WNT antagonist and phenocopied with a WNT agonist. Gene expression analyses in organoids show alterations in expression of genes critical to neuronal development, POU3F2/BRN2 and CALB1. Further, gene expression analyses reveal that similiar gene expression changes are induced by DISC1 mutation and transient treatment of wild-type cells with a WNT agonist. Taken together, these results support the hypothesis that loss of long DISC1 isoforms results in an elevation of baseline WNT signaling in NPCs, resulting in morphological and neurodevelopmental consequences which may include altered cell fate and progenitor migration.

Materials and methods

Cerebral organoid culture

Cerebral organoids were generated largely as described6. IPSCs were dissociated and 3 × 106 cells plated per well in an AggreWell 800 (Stemcell Technologies) centrifuged at 100×g for 3 min in iPSC media with low FGF2, changed to N2 supplement-containing neural induction media and transferred to 24 well plates on day 6. At this point, differentiation rounds were excluded if there was excessive debris present, or if the aggregates failed to form into cohesive organoids. At day 10, organoids were embedded in Matrigel droplets and transferred to N2/B27 supplement-containing media, and then cultured in organoid differentiation media in non-adhesive, 60 mm dishes thereafter. When indicated, cells were treated with 2 μM XAV939 (Stemgent), 3 μM CHIR99021 (Tocris Bioscience), or vehicle (DMSO) during days 6–19 of differentiation.

All cell lines were confirmed to be mycoplasma-free and to have the correct identity using STR profiling (Genetica) both prior to initiation of the study and at the conclusion of the study. Karyotyping was confirmed using the Nanostring Karytoping panel, and no gross chromosomal abnormalities were observed.

Monolayer neuronal differentiation

Neuronal differentiation was performed using a previously described embryoid aggregate-based protocol9. Briefly, iPSC colonies were removed from mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) and cultured as embryoid aggregates in suspension for 4 days in iPSC media, followed by 2 days in N2 neural induction media. Day 7 aggregates were plated onto Matrigel-coated 6 well plates and maintained in N2 neural induction media, forming neuroepithelial structures. Cells were treated with 3 μM CHIR99021 or vehicle (DMSO) during days 7–17 of differentiation. At day 17, neural rosettes were enzymatically isolated using STEMDiff Neural Rosette Selection Reagent (Stemcell Technologies) and cultured in suspension for 7 days in N2/B27 neural induction media containing cAMP (1 μM, Sigma) and IGF-1 (10 ng/ml, Peprotech). Neural aggregates were dissociated using Accutase in the presence of 10 μM ROCK inhibitor and plated for final differentiation at ~85,000 cells/cm2 in neural differentiation media containing cAMP (10 μM, Sigma), IGF-1, BDNF, and GDNF (10 ng/ml, Peprotech). Cells were cultured for another 16 days to day 40.

Immunostaining

Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (Sigma), followed by membrane permeabilization and blocking with 0.2% Triton X-100 (Sigma) and 2% donkey serum (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories). All quantifications were performed blinded to genotype in ImageJ. Antibodies: Nestin (R&D MAB1259), TBR2 (Abcam ab23345), PAX6 (Covance PRB-278P), BRN2 (Abcam Ab137469), PKCλ (BD Transduction Laboratory 610207), Cleaved caspase 3 (R&D Systems AF835), TUNEL (Sigma 12156792910), Acetylated alpha-tubulin (Cell Signaling 5335S), P73 (Abcam Ab40658), and Reelin (Abcam AB5364).

EdU incorporation

Day 6 cerebral organoids were cultured in media containing 2 μM EdU for 2 days, followed by wash out and harvest on day 19. Cells were then fixed as described above, and EdU staining was carried out using the Click-iT EdU imaging kit (Invitrogen). Quantification of EdU+ was performed in a blinded manner: organoids were coded with random numbers such that the person performing the quantification did not know the identity of each sample until the conclusion of the analysis.

Nanostring gene expression analysis

RNA was extracted from day 19 cerebral organoids using TRIzol (Life Technologies) or from day 40 neurons using the Pure Link RNA Mini Kit (Life Technologies), according to manufacturer’s instructions. Organoids were excluded from Nanostring or qPCR analyses if RNA yields were below 10 μg/μl. A custom 150-gene nCounter CodeSet was designed by NanoString Technologies. Data were analyzed with nSolver analysis software (Nanostring Technologies) and normalized to the total gene set. Assays were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

qPCR

RNA was reverse-transcribed, and cDNA was used for qPCR with Fast SYBR Green Master Mix (Life Technologies) on a ViiA 7 system (Life Technologies). Data were normalized to glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) expression using the ddCT method as described previously10. Primer sequences: GAPDH (forward, gggagccaaaagggtcatca; reverse, tggttcacacccatgacgaa), TBR2 (forward, gccatgcttagtgacaccg; reverse, ggactggaggtagtaccgc), Pax6 (forward, tctaatcgaagggccaaatg; reverse, tgtgagggctgtgtctgttc), CALB1 (forward, ggctccatttcgacgctga; reverse, gcccatactgatccacaaaagtt), POU3F2/BRN2 (forward, cggcggatcaaactgggattt; reverse, ttgcgctgcgatcttgtctat), Pancortin/OLMF1 domain B (forward, gctggtgggcctcaacacc; reverse ccgtgaacacatggtctgct); CALB2 (forward, actttgacgcagacggaaatg; reverse, gaagttctcttcggttcccag); NRG1 (forward, cggtgtccatgccttccat; reverse, gtgtcacgagaagtagaggtct), EAAT2 (forward, cctgacggtgtttggtgtcat; reverse, caagcggccactagccttag), FEZF2 (forward, actggccttttccatcgaga; reverse, tccgagtaactgagcagtgtc), VGLUT1 (forward, ctggggctacattgtcactca; reverse, gcaaagccgaaaactctgttg), VGAT (forward, acgtccgtgtccaacaagtc; reverse, aaagtcgaggtcgtcgcaatg).

Data collection and statistics

All iPSC lines used in this study are isogenic apart from the DISC1 locus7. For each analysis, two wt lines and two DISC1 wt/μ lines were used. Numbers for gene expression analyses were chosen based upon initial pilot results examining the variability in gene expression across organoids. Data were analyzed using GraphPad PRISM 7 software. All quantified data in column graphs are expressed as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was tested as indicated in the figure legends.

Results

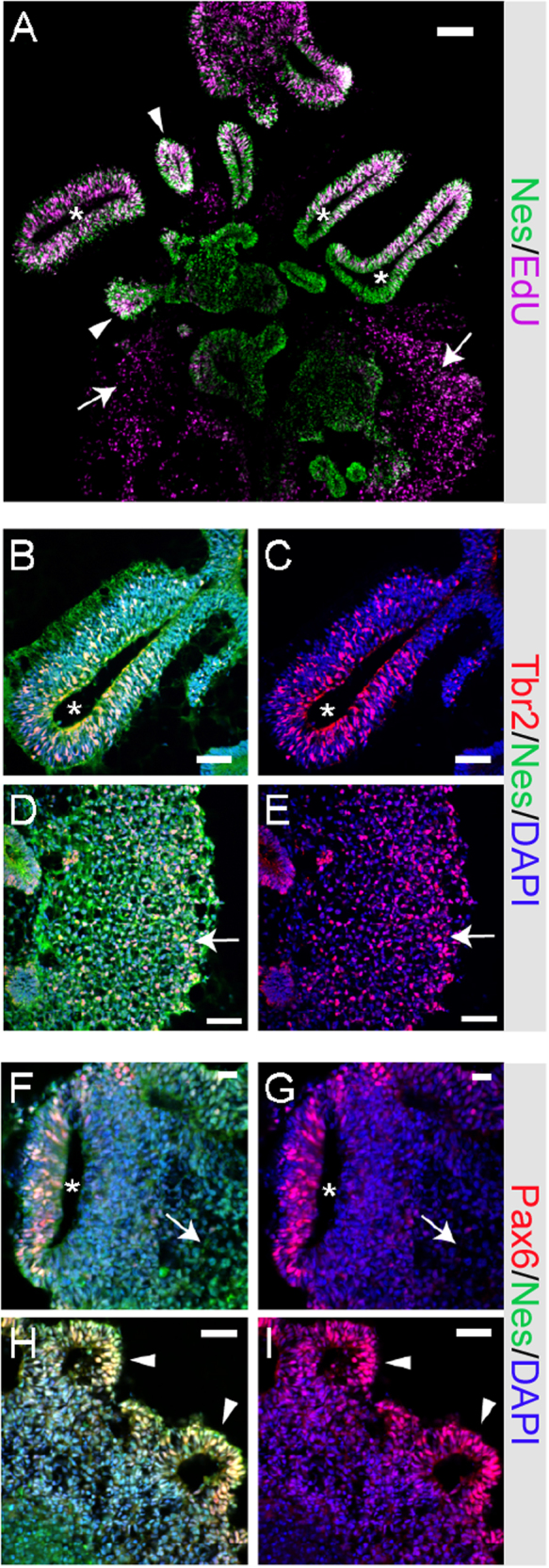

Cerebral organoids express neural progenitor markers with ventricle-like, rosette, and dispersed morphologies

To generate cerebral organoids, we used a protocol similar to that published by the Knoblich lab6 with the following exceptions: we dissociated iPSCs from MEFs using Accutase instead of dispase/trypsin to obtain a single cell suspension, and we used AggreWells for initial embryoid body (EB) formation (3 × 106 cells per Aggrewell) instead of round-bottom plates. To characterize the cultures, organoids were pulsed with EdU during days 6 and 7 of differentiation, then continued in culture for 12 days without EdU. These aggregates were fixed, cryosectioned, and immunostained to examine the morphology of aggregates at this early stage of neurodevelopment. At day 19, wild-type organoids were composed of neural progenitor lineages that line fluid-filled cavities, similar to ventricles, along with regions of neural rosettes. There also were areas of “dispersed” cells that lacked discernible structure. Figure 1a shows a representative organoid stained for EdU and the NPC cytoskeletal marker Nestin (NES), with examples of each type of structural morphology. Interestingly, subsets of cells were found to express a marker of radial glia (PAX6) and a marker of intermediate progenitor cells (TBR2/EOMES) in areas with disparate morphologies including: cells lining the large ventricle-like structures, in rosettes, and in dispersed areas (Fig. 1b–i). This initial characterization revealed that organoids, at this time point, contain forebrain neural progenitors with heterogeneous structural organization.

Fig. 1. Cerebral organoids express neural progenitor markers with ventricle, rosette, and dispersed morphologies.

a Organoids were differentiated to day 19 and pulsed with 2 μM EdU during days 6–7 before being fixed, sectioned, and stained for Nestin and EdU, showing areas of ventricle (asterisk), rosette (arrowhead), and dispersed (arrow) morphology. Day 19 organoids immunostained for b–e Tbr2 and Nestin, or f–i Pax6 and Nestin, showing areas of ventricle (asterisk), rosette (arrowhead), and dispersed (arrow) morphology. Scale bars: 100 μm (a), 50 μm (b–e, j–l), 20 μm (f–i)

DISC1 mutation disrupts cerebral organoid morphology in a manner that is phenocopied by WNT agonism

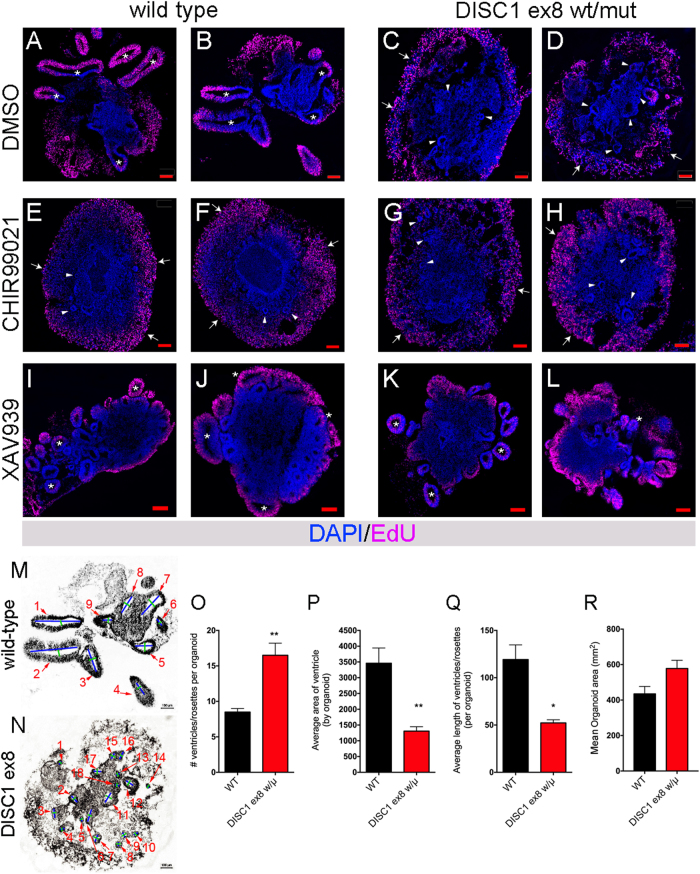

We previously described the generation of isogenic hiPSC lines with DISC1 disruption within exon 87, very near the site of a balanced translocation linked to mental illness in a large Scottish family8. Using TALEN targeting of exon 8, multiple clonal lines were derived that were wild-type or that harbored a premature stop codon within exon 8. Following differentiation to neural progenitor and neuronal fates of the cerebral cortex, we found that long splice variants of DISC1 were reduced by half in heterozygous lines, and eliminated in homozygous lines7. As the balanced translocation leads to elevated risk for mental illness in the heterozygous form (homozygous individuals have not been reported), we chose here to focus upon the model of DISC1 disruption most similar to the disease state, heterozygous exon 8 disruption (DISC1 ex8 wt/μ). To minimize the potential for clone and differentiation-specific effects, two clonal wild-type lines and two clonal DISC1 ex8 wt/μ lines were paired and analyzed over more than 10 differentiations. Unexpectedly, organoids derived from DISC1-mutant iPSCs displayed aberrant morphology (Fig. 2c, d). Mutant organoids lacked large and well-defined ventricle-like structures, and contained more small, disorganized rosette structures, and more areas of dispersed morphology when compared to wild-type organoids (Fig. 2a, b). These morphological changes were quantified for three differentiation rounds by counting the number of ventricles or rosettes present per organoid, average area of ventricles/rosettes per organoid, average length of the long axis of ventricles/rosettes present in each organoid, and total organoid area (Fig. 2o–r). As there are no clear criteria for differentiating rosettes from ventricle-like structures given the 3D structure of organoids, rosettes and ventricle-like structures were pooled for analysis, with example length/width measurements shown in Fig. 2m–n. Quantification revealed significant alterations with DISC1 mutation consistent with visible morphological changes, with increased numbers of rosettes per organoid (Fig. 2o), decreased ventricle/rosette area (Fig. 2p), and decreased length of the long axis of ventricles/rosettes (Fig. 2q). Notably, there was no clear difference in organoid area between wild-type and DISC1-mutant organoids (Fig. 2r).

Fig. 2. DISC1 disruption alters cerebral organoid morphology.

a–l Wild-type and DISC1-disrupted organoids were pulsed with EdU for 2 days (culture days 6–7), then fixed, sectioned, and stained for EdU at day 19. Two representative organoids are shown for wild-type (a, b, e, f, i, j) and DISC1-disrupted (c, d, g, h, k, l) lines treated with either DMSO (vehicle, a–d), WNT agonist CHIR99021 (e–h), or WNT antagonist XAV939 (i–l). Well-defined ventricles/rosettes are labeled with asterisks, small poorly defined rosettes labeled with arrowheads, and areas of dispersed morphology labeled with arrows. Scale bars = 100 μm. Example measurements of ventricles/rosettes (labeled with red arrows) with blue lines labeling length and green lines labeling width, are shown in m (same image as b) and n (same image as d). Morphology of DMSO-treated wild-type or DISC1-disrupted organoids was quantified, blinded, in sections from the middle of the organoid, by counting number of ventricles or rosettes visible per organoid (o), average ventricle/rosette area per organoid (p), average length of the long axis of ventricles/rosettes per organoid (q), and organoid area (r). Data were derived from four independent differentiations. n = 4 (wt), 4 (DISC1 wt/μ). Statistics: two-tailed Student’s t-test. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01. Variances were not significantly different in o, p, and r. Variances were significantly different in q, and t-test was performed with Welch’s correction. See also Supplementary Figure 1 for normalization per total area for each organoid

Multiple studies have previously linked DISC1 function to WNT signaling7,11,12. In our initial report describing DISC1-mutant neural cells in monolayer culture, we found that DISC1 disruption resulted in an elevation in baseline WNT signaling, which caused subtle alterations in cell fate at a neuronal time point (differentiation day 40)7. To examine whether elevated WNT signaling could induce the altered morphology observed in cerebral organoids with DISC1 disruption, organoids were treated with a WNT agonist (GSK3β inhibitor CHIR99021, 3 μM13) during days 6–19 of culture. Interestingly, incubation with the WNT agonist resulted in a structural change in wild-type organoids that phenocopied the effects of DISC1 disruption, including increased areas of dispersed cell morphology, and more small and disorganized rosette structures (Fig. 2e, f). WNT agonism of DISC1-mutant organoids did not have a marked effect on morphology (Fig. 2g, h). Furthermore, WNT antagonism (using tankyrase inhibitor XAV939, 2 μM14) similarly affected both wild-type and DISC1 ex8 wt/μ organoids to produce small, well-defined rosette/ventricle structures (Fig. 2i–l). Quantification showed that WNT antagonism with XAV939 rescued the phenotype of increased ventricle/rosette numbers with DISC1 disruption (normalized to organoid area, Supplemental Figure 1A).

DISC1 disruption reduces proliferation but does not affect apoptosis in early cerebral organoids

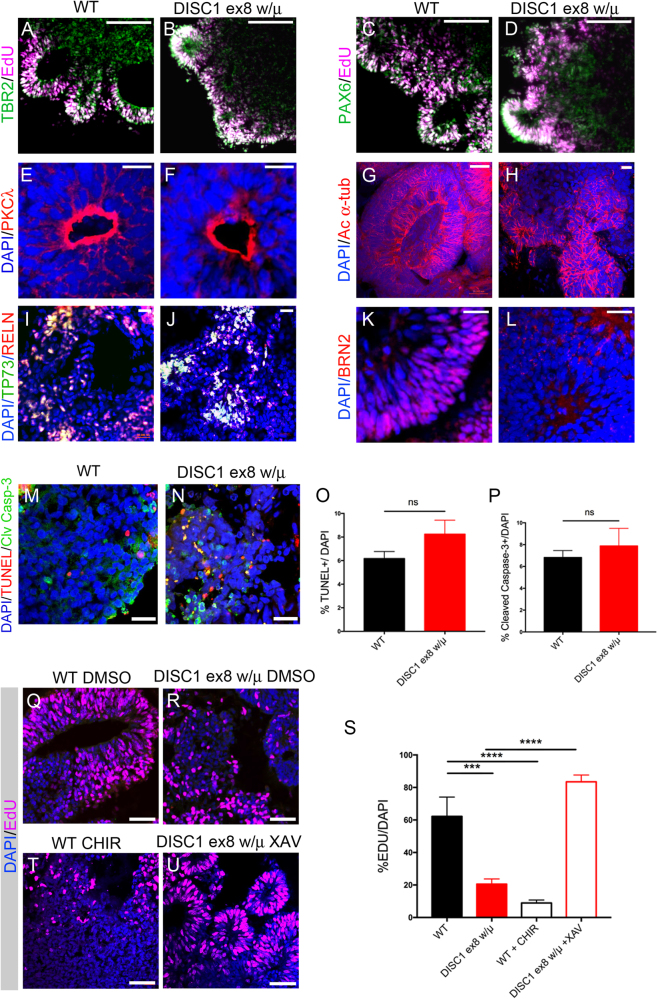

We compared expression of certain cell fate markers in wild-type and DISC1 exon 8-mutant organoids. Subventricular zone (SVZ) intermediate progenitor marker TBR2 and dorsal neocortical and ventricular zone (VZ) progenitor marker PAX615 were expressed similarly in WT and DISC1-disrupted organoids (Fig. 3a–d). The polarity of progenitors in neural rosettes was similar, with apical membranes directed interiorly, as identified by PKCλ and acetylated α-tubulin immunostaining (Fig. 3e–h). Markers of Cajal–Retzius cells, Reelin and p73, were identified in both WT and mutant organoids (Fig. 3i, j). Interestingly, expression of late neocortical progenitor and layer II–V neuronal marker BRN2/POU3F2, which has been shown to be critical for proper cortical lamination16, was markedly decreased with DISC1 mutation (Fig. 3k–l). Expression of neural progenitor markers PAX6 and TBR2 (EOMES), glutamatergic neuronal marker VGLUT1 (SLC17A7) and GABAergic neuronal marker VGAT (SLC32A1) were not significantly changed in d19 DISC1-mutant organoids, as measured by qPCR (Supplemental Figure 2).

Fig. 3. DISC1-mutant organoids exhibit decreased BRN2 expression and reduced proliferation that is rescued by WNT antagonism.

Immunostaining was performed on WT and DISC1-mutant day 19 organoids for EdU incorporation and markers as shown. Expression of cell fate markers TBR2, PAX6, P73, Reelin and polarity markers PKC-λ, and acetylated-α-tubulin were grossly unchanged (a–j). However, immunostaining of BRN2 was markedly reduced in DISC1-mutant organoids (k, l). Scale bars: a–d 100 μm, e–h 20 μm, i–j 50 μm, k–l 20 μm. m, n WT and DISC1 exon 8 wt/μ organoids were immunostained at day 19 for markers of apoptosis (TUNEL and Cleaved Caspase 3). o, p Quantification of percentage of DAPI positive nuclei positive for TUNEL or cleaved caspase-3 shows no difference with DISC1 disruption. q–u WT and DISC1-mutant organoids with WNT agonism (CHIR) or WNT antagonism (XAV) were pulsed with EdU for 2 days (culture days 6–7), then fixed, sectioned, and stained for EdU and DAPI at day 19. One representative image for each condition is shown. s Percentage of EdU-positive nuclei were quantified. Data were derived from three independent differentiations. Statistics: o, p Variance was significantly different between conditions, Welch’s t-test. s Variance was significantly different between conditions, one-way ANOVA with Geiser–Greenhouse correction, Sidak’s multiple comparisons test. ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001. Scale bars: m, n, q, p, t, u: 50 μm

DISC1 mutation does not alter apoptosis but results in a WNT-dependent decrease in EdU incorporation

We next investigated whether perturbations in proliferation or apoptosis were associated with the described morphologic alterations in DISC1-mutant cerebral organoids. To evaluate whether altered apoptosis also contributed to aberrant morphology, day 19 organoids were used for TUNEL immunohistochemistry and immunostaining for activated cleaved Caspase 3. There was no significant difference in the percentage of TUNEL+ or cleaved Caspase-3+ cells with DISC1 mutation, suggesting that altered apoptosis does not significantly contribute to the observed phenotype (Fig. 3m–p).

To examine potential changes in proliferation, cerebral organoids were pulsed with EdU during day 6–7 of differentiation, cultured in the presence of either DMSO, CHIR99021, or XAV939 during days 6–19, and then harvested and imaged at day 19 (Fig. 3q–u). As EdU was found to only incorporate into the outer areas of organoids, likely due to limited permeation of the 3D structure (Fig. 2a–l), EdU quantification was performed in these areas, defined in a blinded manner based on maximal penetration of EdU. Quantification showed that DISC1 disruption, as well as WNT agonism with CHIR99021, resulted in a decreased percentage of EdU-positive cells, whereas treatment of DISC1-mutant organoids with WNT antagonist XAV939 rescued this EdU incorporation phenotype (Fig. 3s). This implicates increased WNT activity as a mechanism resulting in decreased proliferation in DISC1-mutant organoids at this early developmental time point.

DISC1 disruption alters expression of genes implicated in neurodevelopment and migration and is mimicked by WNT agonism

To investigate factors contributing to the altered morphology of DISC1-mutant cerebral organoids, we assayed gene expression in day 19 organoids using a custom Nanostring panel of 150 genes related to neuronal development, maturity, and cell signaling. A heat map of expression of a subset of genes reveals the high organoid-to-organoid variability at the molecular level (Fig. 4a). Genes shown in the heat map mark particular subsets of cells in the central nervous system (CNS), revealing the variety in the cell types present in wild type and mutant organoids at day 19. These include markers of excitatory neurons (GRIA2, GRIK1, GRIN2A, VGLUT1, VGLUT2), inhibitory neurons (GAD1, GLRB), caudally located neurons of the hindbrain and spinal cord (HOXA1, HOXA2, HOXB1, HOXB4, IRX3, ISL1) and neural crest cells (HNK1), as well as cortical layer-specific markers (RELN, SATB1, CUX1, CTIP2, TP73, TBR1).

Fig. 4. DISC1 disruption alters BRN2 levels in organoids and monolayer cultures.

Wild-type and DISC1 ex8 wt/μ organoids were harvested at day 19 and RNA was used for Nanostring analyses. a Heat map of cell type markers for wild type (wt) and DISC1 ex8 wt/μ organoids. b Volcano plot of gene expression changes in DISC1 ex8 wt/μ vs. wild-type organoids are shown. Statistics: Student’s t-test, unadjusted p-values plotted; n = 7 for wild-type, 8 for DISC1 wt/μ, from four independent differentiations. See also Supplementary Table 1. c, d qPCR was performed for BRN2 and CALB1 on RNA derived from day 19 organoids. Data were derived from three independent differentiations. For each differentiation, over five organoids were pooled for analysis. e Wild-type and DISC1 ex8 w/μ iPSCs were differentiated to NPCs using an EB protocol7 and subsequently dissociated and plated as monolayer culture. Day 40 neuronal RNA was harvested and used for Nanostring. Data were derived from three to seven independent differentiations. Statistics: c One-way ANOVA with Sidak multiple comparisons test, d,e Student’s t-test, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ****p < 0.0001. f Table summarizing gene expression changes across both differentiation methods: organoid day 19 qPCR (from c, d and other data not shown) and day 40 monolayer Nanostring data. Asterisks indicate significance by two-tailed Student’s t-test; #indicates data published in ref. 7

Due in part to inherent variability of cerebral organoids at the molecular level, no genes achieved statistical significance with correction for multiple comparisons across the 150 genes examined. Using unadjusted p-values, DISC1 expression was one of the more significant findings, which is consistent with our previous findings of decreased DISC1 expression with this genomic mutation due to nonsense-mediated decay (as previously observed in neural cultures derived from these cells7). Among the other gene changes highlighted by this discovery set were decreased expression of BRN2/POU3F2, Calretinin (CALB2), and EAAT2/SLC1A2, and increased expression of Pancortin (OLFM1), Calbindin (CALB1), FEZF2, and NRG1 (Fig. 4a, b).

To test the validity of observed gene expression changes, a set of replication experiments were performed to measure a selection of genes using qPCR. This confirmed decreased BRN2 and increased CALB1 expression (Fig. 4c, d). Although some other genes showed trends for altered expression in agreement with Nanostring results (decreased EAAT2 and CALB2; increased FEZF2 and OLFM1), these did not reach significance.

Given the variability of organoid cultures, we complemented this assay with a study of neuronal cells differentiated via a similar protocol but with plating of neuroepithelial cells in a monolayer9. Previous reports have shown that non-neural cells can arise using the protocol on which our organoid protocol is based, which could be contributing to our observed variability6. An important difference between our organoid and monolayer protocol is the addition of a purification step to separate the neural from non-neural cells via adherence to Matrigel followed by rosette selection. Indeed, this reduced the heterogeneity in the cell types present between individual cultures, therefore reducing variability at the gene expression level (Fig. 5e, Supplementary Table 2). Interestingly, of the genes highlighted in Fig. 5b, BRN2, EEAT2, and NRG1 expression all were significantly reduced with DISC1 mutation in this monolayer system (Fig. 4e and ref. 7). A summary of organoid qPCR data (Fig. 4c, d and data not shown), as well as monolayer day 40 Nanostring data (Fig. 4e) is shown in Fig. 4f.

Fig. 5. DISC1 disruption alters expression of genes implicated in neurodevelopment and migration and is phenocopied by WNT agonism.

Wild-type and DISC1 ex8 wt/μ iPSCs were differentiated to NPCs and treated with vehicle (DMSO) or WNT agonist CHIR99021 (CHIR) during days 7–17, followed by withdrawal of small molecules and subsequent monolayer culture. Day 40 neuronal RNA was harvested and used for Nanostring. a Venn diagram showing genes with significantly altered expression with shared direction of fold-change compared to wild-type. Number of genes per category is shown within the diagram. Statistics: Student’s t-test with multiple comparisons correction using 2-stage linear step-up procedure of Benjamini, Krieger, and Yekutieli, with Q = 5%. b–d Nanostring data for select genes are shown, including genes associated with cell fate (b), genes associated with glutamatergic neurotransmission (c), and genes associated with interneuron development (d). Statistics: Holm–Sidak; WT n = 15, WT CHIR n = 18, DISC1 ex8 wt/μ n = 7. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001. See also Supplementary Table 2

As WNT agonism phenocopied the organoid morphology of DISC1 disruption, we sought to investigate the shared effects of DISC1 mutation and WNT agonism on gene expression. Neuroepithelial aggregates were cultured with WNT agonist CHIR99021 during days 7–17 of differentiation, followed by withdrawal of the WNT agonist and neuronal culture in traditional differentiation media until day 407. Changes observed at day 40 therefore represent long-lasting changes in cell state that persist more than 20 days after cessation of WNT agonism. Day 40 RNA was harvested and used for the Nanostring assay. A selection of gene expression changes observed under these conditions was published previously7, but here we sought to more globally evaluate changes in gene expression that were shared between DISC1 disruption and WNT agonist treatment. Expression of a subset of general markers of neuronal and astrocyte fates were unchanged with DISC1 mutation or CHIR99021 treatment (Supplementary Table 2, ref. 7). DISC1 exon 8 mutation altered expression of 74 genes, whereas early CHIR99021 treatment of wild-type cells changed expression of 115 genes (Fig. 5a). Strikingly, 51 shared genes were significantly altered with the same directional fold-change from wild-type in each condition. This represents 69% of all genes altered with DISC1 disruption. The marked overlap of gene expression changes with WNT agonism and DISC1 mutation further support a model in which DISC1 disruption leads to downstream changes in neural cells via augmented WNT signaling.

Gene expression changes shared between DISC1 ex8 wt/μ and CHIR99021-treated wild-type cells included many genes important for neurodevelopment and cell fate. A handful of these were published previously (including BRN2 (POU3F2), DAB2, FOXG1, GSX2, HES1, IRX3, SIX3, TBR2, and WNT3A)7. Of those genes that showed a suggestion of alteration in day 19 organoids, BRN2 and EAAT2 were also decreased in neurons with DISC1 mutation and in wild-type neurons exposed to CHIR99021 (EAAT2 shown in Fig. 5c; BRN2 in ref. 7, normalized data in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2). DISC1 mutation and CHIR99021 treatment also led to decreased expression of lower-layer cortical neuronal marker FOXP2 and increased expression of upper-layer marker CUX1 (Fig. 5b). Decreased expression of the immature neuronal marker DCX and increased expression of pro-proliferative protein CCND2 and neural progenitor marker Vimentin (VIM) further pointed to alteration in neural progenitor fates with DISC1 mutation at this later developmental stage (Fig. 5b). We also observed increased expression of DIXDC1, a regulator of neurogenesis (Fig. 5b). Expression of glutamatergic cell markers showed decreased GRIN1 and GRIN2B expression, but increased VGLUT1 (SLC17A7) expression (Fig. 5c). Interestingly, expression of ventral progenitor markers GSX27 and GSX1, and GABAergic cell markers GAD1, GAD2, and VGAT (SLC32A1) were decreased, suggesting perturbed interneuron development (Fig. 5d). Recapitulation of DISC1 ex8 wt/μ expression changes with WNT agonism in wild-type cells was consistent with increased WNT signaling in DISC1-mutant lines causing cell fate and morphologic phenotypes. Overall, these data show that DISC1 disruption alters expression of select genes related to neural development and migration in cerebral organoids and monolayer neurons, many of which are induced by WNT agonism in wild-type cells.

Discussion

The continual evolution of stem cell differentiation methods provides opportunities for investigating human neuropsychiatric disorders in cellular models that recapitulate different aspects of human neurodevelopment. The development of 3D culture methods has allowed the study of disease-linked genetic insults on cellular organization in a model of human cortex. Here, we used this method to investigate effects of a disease-relevant DISC1 mutation in early cerebral organoids. Analyses of organoid morphology showed that DISC1 disruption resulted in disorganization of organoid structure, with an increased number of small and disorganized rosettes in place of the larger rosette and ventricle-like structures in wild-type organoids. This finding highlights the promise of using cerebral organoids for disease modeling, allowing the discovery of morphological phenotypes that cannot be as easily studied with monolayer cultures. This morphologic change was induced in wild-type cells with a WNT agonist, and was partially rescued with a WNT antagonist, suggesting that abnormal WNT signaling in DISC1-disrupted cells contribute to the morphologic phenotype. This disrupted structural organization could represent a developmental defect in neural progenitor proliferation and/or migration. Given that patients with heterozygous DISC1 disruption do not have gross cortical structural defects17,18, this phenotype may be amplified in the organoid system due to the inherent qualities of the system, such as a lack of compensatory mechanisms present in vivo that are lacking in vitro (for example, mechanisms mediated by surrounding support cells such as microglia and cells of the vasculature). Furthermore, protective alleles may exist that prevent manifestation of the neurodevelopmental defects seen in this cell culture system.

The linkage between DISC1, WNT signaling, and NPC proliferation described here in this 3D human neurodevelopmental system is consistent with a number of findings in human subjects and mouse models of DISC1 disruption. In both human and mouse cells, DISC1 variants associated with mental illness reduce NPC proliferation and affect responses to WNT12. In both animal models and human imaging studies, findings are consistent with our data that DISC1 disruption perturbs neurogenesis. Several studies have shown a reduction in cortical volume, enlarged ventricles, and/or thinning of the cortex in animal models with DISC1 disruption19–23. In addition, multiple mouse studies have shown specific reductions in GABAergic neurons in the cortex with DISC1 mutation19,20,24,25. Furthermore, imaging studies in humans have reported linkages between DISC1 variants and cortical thickness in children and adolescents26 and in gray matter density and/or cortical thickness in adults27–33. In a recent imaging study of subjects in the Scottish pedigree harboring the translocation that disrupts DISC1, cortical thickness was significantly reduced in translocation carriers, a phenotype which was shared with SCZ subjects17.

We found that expression of BRN2 was significantly reduced with a DISC1 disruption in both cellular systems (Fig. 4). In organoids, this reduction was rescued by a WNT antagonist and phenocopied by a WNT agonist. BRN2 is a transcription factor that upregulates proneural genes, and has been shown to be required for generation and migration of upper-layer neurons in the rodent neocortex16,34–36. BRN2 directly modulates expression of TBR235, consistent with our previous finding that a DISC1 mutation reduces production of TBR2+ NPCs in monolayer culture7. A genetic interaction between BRN2 and major mental illness has been previously described: SNPs in the BRN2 locus were significantly associated with an interaction between an imaging quantitative trait and schizophrenia diagnosis37. In addition, multiple GWAS studies have shown an association between SNPs near BRN2 and bipolar disease38–40.

A recent study of human iPSC-derived NPCs from autistic individuals with macrencephaly showed reductions in WNT signaling, increases in proliferation and a reduction in BRN2 levels41. Dysregulation of a “β-catenin/BRN2/TBR2 transcriptional cascade” in mice was previously shown to lead to autism-related behavioral changes, as well as to a transient increase in embryonic brain size42. Our results also suggest disruption of this axis with DISC1 mutation, but with an elevation of baseline canonical WNT signaling and reduction of NPC proliferation7. However, in both the autism model and our DISC1-mutant model, BRN2 levels are decreased, suggesting perhaps additional age-dependent and context-dependent outcomes of disruption of this axis. Together, these studies add further evidence to the hypothesis that subsets of autism and schizophrenia are diametrically opposed conditions with regards to their neurodevelopmental basis (ref. 43 and others).

The shared gene expression changes with DISC1 interruption and WNT agonism suggest those genes that may be the best candidates for mediating the shared morphologic changes seen in cerebral organoids with DISC1 mutation and with CHIR99021 treatment. Interestingly, many differentially expressed shared genes have known roles in cortical cell migration in development. Decreased expression of DCX (a marker of newly-generated neurons and regulator of neuronal migration44–46) and increased expression of Vimentin (a marker of neural precursor cells47) may indicate a dysregulation of neural progenitor fate and migration and could contribute to the altered morphology seen in organoids with DISC1 disruption or CHIR99021 treatment. Expression of neuronal layer markers FOXP2 and CUX1 were dysregulated by DISC1 disruption and WNT agonism. FOXP2 expression is modulated by POU3F2, and it is a regulator of radial neuronal migration in the developing cortex48,49 and a marker of deep-layer cortical neurons in the adult brain50,51. Decreased expression of deep-layer cortical markers FOXP252 and increased expression of upper-layer marker CUX153 suggest a perturbation of neurogenesis, increasing the relative generation of upper-layer versus lower-layer neurons.

Certain markers of interneurons were differentially expressed with DISC1 mutation and WNT agonism, and others were altered in DISC1-mutant organoids. The calcium-binding proteins CALB1 and CALB2—altered in organoids—are both implicated in neuronal development of excitatory as well as inhibitory neurons, and are later expressed in subsets of interneurons54–57. Decreased expression of GSX1 (a marker of ventral telencephalic development58,59) and inhibitory neuron markers GAD1, GAD2, and VGAT suggest disrupted interneuron development. This is of particular interest given the linkage of interneuron dysfunction to major mental illnesses60 and prior observed roles of DISC1 in interneurons19,61. NRG1, another gene altered with DISC1 mutation, is known to be a regulator of cortical interneuron migration via interaction with ERBB4 expressed in radial glia62–64. In addition, NRG1 is a genetic susceptibility factor in schizophrenia65,66.

Expression of DIXDC1, a homolog of the WNT pathway genes Axin and Disheveled, was increased in neurons with DISC1 disruption and WNT agonism. This protein has been found to regulate neurogenesis and neuronal migration via interaction with DISC1 by WNT-dependent and WNT-independent mechanisms, respectively11. Increased DIXDC1 expression may represent a compensatory mechanism to regulate neurogenesis and/or migration resulting from loss of DISC1.

Another gene changed with DISC1 disruption is EAAT2, a major glutamate transporter in the human brain, that is expressed in neurons in the developing human cortex and in astrocytes postnatally67,68. Interestingly, EAAT2 polymorphisms and splice variants have been associated with schizophrenia69–72, supporting a role for altered glutamate trafficking. These findings may suggest a common mechanism of disease pathophysiology involving glutamate transmission, but require further study.

Together, altered expression of these genes with DISC1 disruption suggests aberrant human cortical neurogenesis, migration, and interneuron development. These are especially attractive targets for future investigation in a model of human neurodevelopment given prior studies showing roles for DISC1 in cortical neuronal migration and interneuron development in rodents19,61,73–77. This study builds on prior work from our group showing that DISC1-mutant neural progenitors displayed increased basal WNT signaling and alterations in cell fate and gene expression that were rescued by WNT antagonism7. In addition to showing these results in a novel culture system, we show the relevance of this altered signaling to a novel morphologic phenotype in DISC1-mutant cerebral organoids. These findings add to a growing literature implicating WNT signaling in the pathogenesis of psychiatric disease12,78–82.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

We thank Dennis Selkoe, Matthew LaVoie, and Richard Pearse for valuable feedback on this study. This work is supported by funding from the Sackler Scholar Programme in Psychobiology and NIMH grant 1F30MH103890-01A1 (P.S.), a Young Investigator Award from the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation (T.Y.-P.), and NIMH grant R01MH101148 (T.Y.-P.).

Authors’ contributions

V.L. and P.S. performed experiments and data analyses. C.R.M., S.C.R., A.H., W.M.T., M.A., and C.Z. assisted with organoid differentiations and immunostaining. T.Y.-P. and P.S. designed the project and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

These authors contributed equally: Priya Srikanth, Valentina Lagomarsino.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41398-018-0122-x.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Srikanth, P. & Young-Pearse, T. L. Stem cells on the brain: modeling neurodevelopmental and neurodegenerative diseases using human induced pluripotent stem cells. J. Neurogenet.28, 5–29 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Eiraku M, et al. Self-organized formation of polarized cortical tissues from ESCs and its active manipulation by extrinsic signals. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3:519–532. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mariani J, et al. Modeling human cortical development in vitro using induced pluripotent stem cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:12770–12775. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1202944109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kadoshima T, et al. Self-organization of axial polarity, inside-out layer pattern, and species-specific progenitor dynamics in human ES cell-derived neocortex. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:20284–20289. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1315710110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lancaster, M. A. et al. Cerebral organoids model human brain development and microcephaly. Nature501, 373–379 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Lancaster MA, Knoblich JA. Generation of cerebral organoids from human pluripotent stem cells. Nat. Protoc. 2014;9:2329–2340. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2014.158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Srikanth P, et al. Genomic DISC1 disruption in hiPSCs Alters Wnt signaling and neural cell fate. CellReports. 2015;12:1414–1429. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.07.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Millar JK, et al. Disruption of two novel genes by a translocation co-segregating with schizophrenia. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2000;9:1415–1423. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.9.1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Muratore CR, Srikanth P, Callahan DG, Young-Pearse TL. Comparison and optimization of hiPSC forebrain cortical differentiation protocols. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e105807. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0105807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Singh KK, et al. Dixdc1 is a critical regulator of DISC1 and embryonic cortical development. Neuron. 2010;67:33–48. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Singh KK, et al. Common DISC1 polymorphisms disrupt Wnt/GSK3β signaling and brain development. Neuron. 2011;72:545–558. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.09.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Naujok O, Lentes J, Diekmann U, Davenport C, Lenzen S. Cytotoxicity and activation of the Wnt/beta-catenin pathway in mouse embryonic stem cells treated with four GSK3 inhibitors. BMC Res. Notes. 2014;7:273. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-7-273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang, S.-M. A. et al. Tankyrase inhibition stabilizes axin and antagonizes Wnt signalling. Nature461, 614–620 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Molyneaux BJ, Arlotta P, Menezes JRL, Macklis JD. Neuronal subtype specification in the cerebral cortex. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2007;8:427–437. doi: 10.1038/nrn2151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McEvilly RJ, de Diaz MO, Schonemann MD, Hooshmand F, Rosenfeld MG. Transcriptional regulation of cortical neuron migration by POU domain factors. Science. 2002;295:1528–1532. doi: 10.1126/science.1067132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Doyle OM, et al. The cortical thickness phenotype of individuals with DISC1 translocation resembles schizophrenia. J. Clin. Invest. 2015;125:3714–3722. doi: 10.1172/JCI82636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Whalley HC, et al. Effects of a balanced translocation between chromosomes 1 and 11 disrupting the DISC1 locus on white matter integrity. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0130900. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0130900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hikida T, et al. Dominant-negative DISC1 transgenic mice display schizophrenia-associated phenotypes detected by measures translatable to humans. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:14501–14506. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704774104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ayhan Y, et al. Differential effects of prenatal and postnatal expressions of mutant human DISC1 on neurobehavioral phenotypes in transgenic mice: evidence for neurodevelopmental origin of major psychiatric disorders. Mol. Psychiatry. 2011;16:293–306. doi: 10.1038/mp.2009.144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pletnikov MV, et al. Enlargement of the lateral ventricles in mutant DISC1 transgenic mice. Mol. Psychiatry. 2008;13:115. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4002144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shen S, et al. Schizophrenia-related neural and behavioral phenotypes in transgenic mice expressing truncated Disc1. J. Neurosci. 2008;28:10893–10904. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3299-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee FHF, Kaidanovich-Beilin O, Roder JC, Woodgett JR, Wong AHC. Genetic inactivation of GSK3α rescues spine deficits in Disc1-L100P mutant mice. Schizophr. Res. 2011;129:74–79. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2011.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Umeda K, et al. Immunohistochemical evaluation of the GABAergic neuronal system in the prefrontal cortex of a DISC1 knockout mouse model of schizophrenia. Synapse. 2016;70:508–518. doi: 10.1002/syn.21924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nakai T, et al. Alterations of GABAergic and dopaminergic systems in mutant mice with disruption of exons 2 and 3 of the Disc1 gene. Neurochem. Int. 2014;74:74–83. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2014.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Raznahan A, et al. Longitudinally mapping the influence of sex and androgen signaling on the dynamics of human cortical maturation in adolescence. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:16988–16993. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1006025107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hashimoto R, et al. Impact of the DISC1 Ser704Cys polymorphism on risk for major depression, brain morphology and ERK signaling. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2006;15:3024–3033. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Christian CJ, et al. Gray matter structural alterations in obsessive-compulsive disorder: relationship to neuropsychological functions. Psychiatry Res. 2008;164:123–131. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2008.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Callicott JH, et al. Variation in DISC1 affects hippocampal structure and function and increases risk for schizophrenia. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:8627–8632. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500515102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Di Giorgio A, et al. Association of the SerCys DISC1 polymorphism with human hippocampal formation gray matter and function during memory encoding. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2008;28:2129–2136. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2008.06482.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cannon TD, et al. Association of DISC1/TRAX haplotypes with schizophrenia, reduced prefrontal gray matter, and impaired short- and long-term memory. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2005;62:1205–1213. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.11.1205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brauns S, et al. DISC1 is associated with cortical thickness and neural efficiency. Neuroimage. 2011;57:1591–1600. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.05.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Carless MA, et al. Impact of DISC1 variation on neuroanatomical and neurocognitive phenotypes. Mol. Psychiatry. 2011;16:1096–104–1063. doi: 10.1038/mp.2011.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sugitani Y, et al. Brn-1 and Brn-2 share crucial roles in the production and positioning of mouse neocortical neurons. Genes Dev. 2002;16:1760–1765. doi: 10.1101/gad.978002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dominguez MH, Ayoub AE, Rakic P. POU-III transcription factors (Brn1, Brn2, and Oct6) influence neurogenesis, molecular identity, and migratory destination of upper-layer cells of the cerebral cortex. Cereb. Cortex. 2013;23:2632–2643. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhs252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Castro DS, et al. Proneural bHLH and Brn proteins coregulate a neurogenic program through cooperative binding to a conserved DNA motif. Dev. Cell. 2006;11:831–844. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Potkin SG, et al. A genome-wide association study of schizophrenia using brain activation as a quantitative phenotype. Schizophr. Bull. 2009;35:96–108. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbn155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mühleisen TW, et al. Genome-wide association study reveals two new risk loci for bipolar disorder. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:3339. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hou L, Srivastava Y, Jauch R. Molecular basis for the genome engagement by Sox proteins. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2017;63:2–12. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2016.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Charney, A. W. et al. Evidence for genetic heterogeneity between clinical subtypes of bipolar disorder. Transl. Psychiatry7, e993 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41.Marchetto MC, et al. Altered proliferation and networks in neural cells derived from idiopathic autistic individuals. Mol Psychiatry. Mol. Psychiatry. 2017;22:820–835. doi: 10.1038/mp.2016.95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Belinson H, et al. Prenatal β-catenin/Brn2/Tbr2 transcriptional cascade regulates adult social and stereotypic behaviors. Mol. Psychiatry. 2016;21:1417–1433. doi: 10.1038/mp.2015.207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Crespi B, Stead P, Elliot M. Evolution in health and medicine Sackler colloquium: comparative genomics of autism and schizophrenia. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107(Suppl 1):1736–1741. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906080106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Koizumi H, et al. Doublecortin maintains bipolar shape and nuclear translocation during migration in the adult forebrain. Nat. Neurosci. 2006;9:779–786. doi: 10.1038/nn1704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Toriyama M, et al. Phosphorylation of doublecortin by protein kinase A orchestrates microtubule and actin dynamics to promote neuronal progenitor cell migration. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:12691–12702. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.316307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gleeson JG, Lin PT, Flanagan LA, Walsh CA. Doublecortin is a microtubule-associated protein and is expressed widely by migrating neurons. Neuron. 1999;23:257–271. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80778-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Noctor SC, et al. Dividing precursor cells of the embryonic cortical ventricular zone have morphological and molecular characteristics of radial glia. J. Neurosci. 2002;22:3161–3173. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-08-03161.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Clovis YM, et al. Convergent repression of Foxp2 3’UTR by miR-9 and miR-132 in embryonic mouse neocortex: implications for radial migration of neurons. Development. 2012;139:3332–3342. doi: 10.1242/dev.078063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Garcia-Calero E, Botella-Lopez A, Bahamonde O, Perez-Balaguer A, Martinez S. FoxP2 protein levels regulate cell morphology changes and migration patterns in the vertebrate developing telencephalon. Brain Struct. Funct. 2016;221:2905–2917. doi: 10.1007/s00429-015-1079-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ferland RJ, Cherry TJ, Preware PO, Morrisey EE, Walsh CA. Characterization of Foxp2 and Foxp1 mRNA and protein in the developing and mature brain. J. Comp. Neurol. 2003;460:266–279. doi: 10.1002/cne.10654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hisaoka T, Nakamura Y, Senba E, Morikawa Y. The forkhead transcription factors, Foxp1 and Foxp2, identify different subpopulations of projection neurons in the mouse cerebral cortex. Neuroscience. 2010;166:551–563. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.12.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Arlotta P, et al. Neuronal subtype-specific genes that control corticospinal motor neuron development in vivo. Neuron. 2005;45:207–221. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.12.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nieto M, et al. Expression of Cux-1 and Cux-2 in the subventricular zone and upper layers II-IV of the cerebral cortex. J. Comp. Neurol. 2004;479:168–180. doi: 10.1002/cne.20322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Litwinowicz B, et al. Developmental pattern of calbindin D28k protein expression in the rat striatum and cerebral cortex. Folia Morphol. 2003;62:327–329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hof PR, et al. Cellular distribution of the calcium-binding proteins parvalbumin, calbindin, and calretinin in the neocortex of mammals: phylogenetic and developmental patterns. J. Chem. Neuroanat. 1999;16:77–116. doi: 10.1016/S0891-0618(98)00065-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schwaller B. Calretinin: from a “simple” Ca(2+) buffer to a multifunctional protein implicated in many biological processes. Front Neuroanat. Front. 2014;8:3. doi: 10.3389/fnana.2014.00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dávila JC, et al. Embryonic and postnatal development of GABA, calbindin, calretinin, and parvalbumin in the mouse claustral complex. J. Comp. Neurol. 2005;481:42–57. doi: 10.1002/cne.20347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Evans AE, Kelly CM, Precious SV, Rosser AE. Molecular regulation of striatal development: a review. Anat. Res. Int. 2012;2012:106529. doi: 10.1155/2012/106529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pei, Z., Wang, B., Chen, G. & Nagao, M. Homeobox genes Gsx1 and Gsx2 differentially regulate telencephalic progenitor maturation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA108, 1675–1680 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 60.Marín O. Interneuron dysfunction in psychiatric disorders. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2012;13:107–120. doi: 10.1038/nrn3155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Steinecke A, Gampe C, Valkova C, Kaether C, Bolz J. Disrupted-in-schizophrenia 1 (DISC1) is necessary for the correct migration of cortical interneurons. J. Neurosci. 2012;32:738–745. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5036-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Corbin JG, et al. Regulation of neural progenitor cell development in the nervous system. J. Neurochem. 2008;106:2272–2287. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05522.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Huang Z. Molecular regulation of neuronal migration during neocortical development. Mol. Cell Neurosci. 2009;42:11–22. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2009.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Le Magueresse C, Monyer H. GABAergic interneurons shape the functional maturation of the cortex. Neuron. 2013;77:388–405. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Corfas G, Roy K, Buxbaum JD. Neuregulin 1-erbB signaling and the molecular/cellular basis of schizophrenia. Nat. Neurosci. 2004;7:575–580. doi: 10.1038/nn1258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jaaro-Peled H, et al. Neurodevelopmental mechanisms of schizophrenia: understanding disturbed postnatal brain maturation through neuregulin-1-ErbB4 and DISC1. Trends Neurosci. 2009;32:485–495. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2009.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Furuta A, et al. Expression of glutamate transporter subtypes during normal human corticogenesis and type II lissencephaly. Brain Res. Dev. Brain Res. 2005;155:155–164. doi: 10.1016/j.devbrainres.2005.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.DeSilva TM, Borenstein NS, Volpe JJ, Kinney HC, Rosenberg PA. Expression of EAAT2 in neurons and protoplasmic astrocytes during human cortical development. J. Comp. Neurol. 2012;520:3912–3932. doi: 10.1002/cne.23130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.O’Donovan SM, et al. Glutamate transporter splice variant expression in an enriched pyramidal cell population in schizophrenia. Transl. Psychiatry. 2015;5:e579. doi: 10.1038/tp.2015.74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Spangaro M, et al. Cognitive dysfunction and glutamate reuptake: effect of EAAT2 polymorphism in schizophrenia. Neurosci. Lett. 2012;522:151–155. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2012.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Fiorentino, A., Sharp, S. I. & McQuillin, A. Association of rare variation in the glutamate receptor gene SLC1A2 with susceptibility to bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Eur. J. Hum. Genet.23, 1200–1206 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 72.Poletti S, et al. Effect of glutamate transporter EAAT2 gene variants and gray matter deficits on working memory in schizophrenia. Eur. Psychiatry. 2014;29:219–225. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2013.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Young-Pearse TL, Suth S, Luth ES, Sawa A, Selkoe DJ. Biochemical and functional interaction of disrupted-in-schizophrenia 1 and amyloid precursor protein regulates neuronal migration during mammalian cortical development. J. Neurosci. 2010;30:10431–10440. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1445-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kim JY, et al. Interplay between DISC1 and GABA signaling regulates neurogenesis in mice and risk for schizophrenia. Cell. 2012;148:1051–1064. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.12.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kamiya A, et al. A schizophrenia-associated mutation of DISC1 perturbs cerebral cortex development. Nat. Cell. Biol. 2005;7:1167–1178. doi: 10.1038/ncb1328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ishizuka, K. et al. DISC1-dependent switch from progenitor proliferation to migration in the developing cortex. Nature473, 92–96 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 77.Kubo KI, et al. Migration defects by DISC1 knockdown in C57BL/6, 129X1/SvJ, and ICR strains via in utero gene transfer and virus-mediated RNAi. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2010;400:631–637. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.08.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Topol A, et al. Signaling in human induced pluripotent stem cell neural progenitor cells derived from four schizophrenia patients. Biol. Psychiatry. 2015;78:e29–e34. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2014.12.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Su P, et al. A dopamine D2 receptor-DISC1 protein complex may contribute to antipsychotic-like effects. Neuron. 2014;84:1302–1316. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Inestrosa NC, Montecinos-Oliva C, Fuenzalida M. Wnt signaling: role in Alzheimer disease and schizophrenia. J. Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2012;7:788–807. doi: 10.1007/s11481-012-9417-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Mao Y, et al. Disrupted in schizophrenia 1 regulates neuronal progenitor proliferation via modulation of GSK3beta/beta-catenin signaling. Cell. 2009;136:1017–1031. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.12.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Brennand, K. J. et al. Modelling schizophrenia using human induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature473, 221–225 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.