Abstract

The aim of the present study was to examine the causal relationships between psychological and social factors, being independent variables and body image dissatisfaction plus symptoms of eating disorders as dependent variables through the mediation of social comparison and thin-ideal internalization. To conduct the study, 477 high-school students from Tehran were recruited by method of cluster sampling. Next, they filled out Rosenberg Self-esteem Scale (RSES), Physical Appearance Comparison Scale (PACS), Self-Concept Clarity Scale (SCCS), Appearance Perfectionism Scale (APS), Eating Disorder Inventory (EDI), Multidimensional Body Self Relations Questionnaire (MBSRQ) and Sociocultural Attitudes towards Appearance Questionnaire (SATAQ-4). In the end, collected data were analyzed using structural equation modeling. Findings showed that the assumed model perfectly fitted the data after modification and as a result, all the path-coefficients of latent variables (except for the path between self-esteem and thin-ideal internalization) were statistically significant (p>0.05). Also, in this model, 75% of scores' distribution of body dissatisfaction was explained through psychological variables, socio-cultural variables, social comparison and internalization of the thin ideal.

The results of the present study provid experimental basis for the confirmation of proposed causal model. The combination of psychological, social and cultural variables could efficiently predict body image dissatisfaction of young girls in Iran.

Key Words: Thin-ideal Internalization, Social comparison, Body image dissatisfaction, mediating effects model, eating disorder symptoms, psychological factors

Ethical Publication Statement

We confirm that we have read the Journal’s position on issues involved in ethical publication and affirm that this report is consistent with those guidelines.

Eating disorders and body image are the most common and most debilitating clinical problems among adolescent girls and young women.1 In recent years a lot of research has been done to identify factors involved in the development and maintenance of these disorders. One of the most influential models in explaining body dissatisfaction and eating disorders is tripartite influence model,2 which claims that the socio-cultural pressures from the media, friends and family affect the body dissatisfaction and symptoms of eating disorders through two major mechanisms (mediator) of internalizing society's ideals of beauty (e.g., thinness) and social comparison. The results of previous research on the tripartite influence model, have supported mediating role of thin- ideal internalization and social comparison between and socio-cultural pressures from the media, friends and family and body dissatisfaction and eating disorder symptoms,3-5 but literature shows that studies conducted on the tripartite influence model have mostly focused on a part of the model rather than the overall model and multiple comparison methods (such as regression analysis) have been used rather than complex modeling techniques (such as structural equations that allows the simultaneous analysis of complex relationships), that limits the extraction of conclusions from previous studies. Few studies 3,4,6 that examined tripartite influence model using structural equation method indicated that paths or variables have been added, deleted, and amended in the tripartite influence model which was not consistent with the main tripartite influence model.

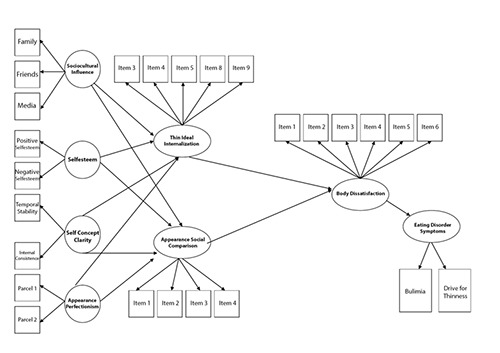

Derrig7 examined the main tripartite influence model using structural equation test and concluded that the tripartite influence model is not fitted to the data. He argued that this result is due to measurement error or theoretical uncertainties. In line with these results and with regard to better fitness of the models which added variables to the tripartite influence model, Derrig7 concluded that the tripartite influence model does not explain womens’ body dissatisfaction, and due to the support of this model from thin-ideal internalization, the social comparison and socio-cultural pressures, it is better to conduct researches by integrating new variables to the tripartite influence model. Given the need to develop a tripartite influence model according to research 4,7 and studies which considered the role of psychological variables in predicting body dissatisfaction through internalizing thinness and social comparison as an important issue.8-10 Now the question is: psychological variables added to the tripartite influence model will increase predictability and better fitness to data? This study investigated psychological variables in Thompson’s tripartite influence model (Figure 1) to answer this question.11-14

Fig 1.

Expansion of Thompson's tripartite influence model: proposed model of the present study

Materials and Methods

Participants

The research method is correlational. The study population consisted of all secondary school students in Tehran in the academic year 2014. Inclusion criteria were the minimum 15 and maximum 17 years of age, because this study focused on high school students. It should be noted that, school principals, students in fourth year of high school was not participated in the study because of exams. Sample size according to Klein (2005), (at least sample size of 5 people for each parameter) was estimated 477 that were selected with multistage cluster sampling (245 first grade, 136 second grade and 96 third grade students). This means that firstly 22 educational districts in Tehran were divided into five geographical regions of North, South, East, West and Central Division and then a region of each was selected. And one school among girls’ high schools was selected from each of these regions and then about 100 people were selected from the students of each school (according to the school authorities’ cooperation).

Self-concept clarity scale:

Self-concept clarity scale15 discusses about that to what extent people have the constant coherent and well defined feeling of them, which contains 12 items that are answered with 5-degree Likert scale from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5). Reliability and validity of this scale has been shown in several studies.15,16 In Iran, after translation into Farsi and translation back into the original language, these tools were observed by two experts and were used in this study after the preliminary execution and confirmation of validity and reliability. In this study, Cronbach's alpha was obtained 0.74.

Appearance Perfectionism scale:

Appearance perfectionism Scale17 contains 10 items and measures the tendency of people to accept very high standards in terms of physical appearance. Item were answered by 7-degree Likert scale from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (7). In Srivastava’s study17 technical features (APS) have been studied. In Iran, after translation into Farsi and translation back into the original language, these tools were observed by two experts and were used in this study after the preliminary execution and confirmation of validity and reliability. In this study, Cronbach's alpha was obtained 0.94.

Self-esteem scale:

To measure self-esteem, ten questions self-esteem scale made by Rosenberg18 was used. Rating of materials was conducted by four-degree scale of strongly agree (3), partly agree (2) partly disagree (1) and strongly disagree (zero). Reliability and validity of this questionnaire have been investigated in Iran by Shapurian, Hojat, and Nayerahmadi19. Cronbach's alpha of the present study was 0.8.

Eating disorder inventory

Eating Disorder Inventory is a 64 item scale built by Garner, Olmsted and polivy 20. Rating method in this case is that scores of 1, 2 and 3 are assigned to the options always, usually and zero is assigned to three choices of sometimes, rarely or never. This questionnaire consists of eight subscales that subscales of drive for thinness and bulimia were used in this study. Reliability and validity of this questionnaire have been studied in Iran by Shayeghian and colleagues 21. In this study, Cronbach's alpha for the subscales of drive for thinness and bulimia have been obtained 0.85 and 0.8, respectively.

Physical Appearance Comparison Scale (PACS)

This scale measures people's tendency for comparing their appearance with others in social situations.22 Which includes 5 items answered with 5-degree Likert scale from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5). Various empirical evidence confirm technical characteristics of PACS.23, 24 Reliability and validity in Iran have been studied by Garousi and Baneshi.25 In this study, Cronbach's alpha of physical appearance scale was obtained 0.84.

Multidimensional body-self relations questionnaire

Multidimensional body-self relations questionnaire26 contains 46 items and six subscales which one of the subscales is appearance evaluation. In this study, this subscale was used to measure body dissatisfaction. This subscale consists of seven items which is answered in 5-degree Likert range from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5). Reliability and validity of this questionnaire in Iran have been examined by Rahati.27 In this study, Cronbach's alpha of appearance evaluation subscale was obtained 0.71. Question 1 of this scale was removed due to cultural restrictions.

Sociocultural Attitudes towards Appearance Questionnaire-4

Sociocultural attitudes towards appearance questionnaire-4 has 22 questions that measures the social and cultural impact on appearance ideals and includes five subscales which one of the subscales is internalization of thinness/low fat. In this study, these subscales were used to measure the thin-ideal internalization. This scale consists of 5 items which are answered by 5 Likert grades from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5). Various empirical evidence has approved technical characteristics of this subscale 28,29. In Iran, after translation into Farsi and translation back into the original language, these tools were observed by two experts and were used in this study after the preliminary execution and confirmation of validity and reliability. In this study, Cronbach's alpha of thinness internalization was obtained 0.85.

Results

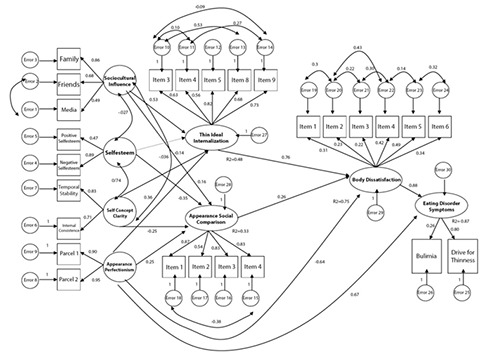

Results of the fitness of proposed model for the goodness of fit index (GFI) and adjusted goodness of fit index (AGFI), comparative fit index (CFI), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) and chi square to its degrees of freedom (χ2 / df) were obtained 0.78, 0.73, 0.75, 0.09 and 5.35 respectively, which shows that the hypothesized model does not have an acceptable fitness with the data, therefore, modification of the model based on statistical findings and theoretical reasoning was necessary, Figures (1-4). According to the Bentler and Chou (1987) and Bentler (1988), it has been noted that characteristic of non-correlation of all errors in a model is rarely proportional with real data. In modifying the model, covariance was created between the remains of error for the items "13 and 10", "14 and 10","14 and 11", "11 and 10", in the latent factor of thin- ideal internalization, between the remains of error for items "18 and 15", in a latent factor of social comparison, between the remains of error for the items "20 and 19", "22 and 20", "22 and 21","24 and 23" "21 and 20", "23 and 22 ", in a latent factor of body dissatisfaction, between the remains of error for the items '2 and 1', in the latent factor of socio-cultural variables. Statements that their error variance is assumed to be correlated together was related to a factor and they had content and conceptual proportionality.

At next step, covariance was created between latent variables of self-esteem and socio-cultural, socio-cultural and self-concept clarity and self-esteem and self-concept clarity. And finally insignificant path of self-esteem to thin-ideal internalization was excluded and two paths from perfectionism to body dissatisfaction and from perfectionism to eating disorder symptoms were added to the final version. Adding the path from perfectionism to body dissatisfaction and eating disorder symptoms reduced chi-square value as much as possible, Figure 2. For the modified model, the goodness of fit index (GFI) and comparative goodness of fit index (AGFI), comparative fit index (CFI), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) and chi square to its degrees of freedom (χ2 / df) were obtained 0.88, 0.85, 0.90, 0.06 and 2.82 respectively. Careful review of goodness of fit Index of structural model shows that the model mentioned have an acceptable fitness with the data after the modification. In this model, 75% of the distribution of body dissatisfaction scores was expressed through psychological, socio-cultural variables, social comparison and thin-ideal internalization. In the modified model, the entire path coefficients (except the insignificant path of self-esteem toward ideal internalization in the modified model removed) between latent variables were statistically significant. In this model, the latent factors of perfectionism appearance and socio-cultural variables were positively and significantly correlated with thin ideal internalization, the relationship between self- concept clarity and thin-ideal internalization was negative and significant, the latent factors of self-esteem and self-concept clarity were negatively and significantly correlated with social comparison, appearance perfectionism and latent factor of socio-cultural variables were positively and significantly correlated with social comparison, the relationship between perfectionism and body dissatisfaction was negative and significant, the relationship between perfectionism and eating disorder symptoms was positive and significant, thin-ideal internalization and social comparison were positively and significantly correlated with body dissatisfaction and the relationship between body dissatisfaction and eating disorder symptoms was significantly positive.

Fig 2.

Final model

Discussion

As mentioned above, the proposed study has good fit with the data after modification, and explains 75 percent of the variance in body dissatisfaction. In possible explanation of this finding, different nature of two mediators of Thompson’s tripartite influence model can be noted. In the case of the mediator of thin-ideal internalization, the socio-cultural variable was the most important predictor variable; this finding is consistent with Thompson’s findings.2 In the possible explanation for this finding it can be said that more encountering with socio-cultural pressures for thinness, internalization of these ideals are naturally higher. But for the mediator of social comparison, psychological variables had more explanatory power than socio-cultural variables. However, Thompson’s original socio-cultural model is considered as the only variable to predict social comparison and adding psychological variables to the Thompson’s original model in this study can increase the predictability of body dissatisfaction variable. To explain why psychological variables have a greater participation in predicting social comparison Festinger's theory 30 can be pointed out. According to Festinger’s theory 30 social comparisons occurs more in people who are not sure of themselves. All three psychological variables used in this study were associated with a lack of self-confidence.8,12,31 Among the proposed modified models applied in previous studies on the tripartite influence model,5,32,33 predictability of this in predicting body dissatisfaction (75%) was higher. This finding can be attributed to selection of psychological variables that have a higher correlation with body dissatisfaction. The final modified model showed what factors directly and indirectly contribute to body dissatisfaction. Instead of simple linear relationships, socio-cultural factors, and psychological factors are intertwined on body dissatisfaction. The applied concept of this result is that, consideration of socio-cultural and psychological factors together is necessary to design and develop interventions to reduce body dissatisfaction. In addition, the implementation of the study of Iran’s Islamic culture that women cover their bodies from the perspective of forbidden men is the innovative aspect of this research that increases the richness of previous research. Due to the high volume of variables the structures used in the study model have been investigated one-dimensionally which is one of the limitations of this study, while according to the literature, each of them can be considered as a multi-dimensional case. Due to lack of cooperation by school authorities, measuring body mass index was not possible, it is suggested that body mass index should be considered in the future research. Increased self-esteem and adjusted perfectionism in order to solve the problems of body dissatisfaction in adolescent girls should be specifically considered.

Acknowledgments and Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Acknowledgments and Funding

We thank participants for their contributions. Funding: None

List of acronyms

- RSES

Rosenberg Self-esteem Scale

- PACS

Physical Appearance Comparison Scale

- SCCS

Self-Concept Clarity Scale

- APS

Appearance Perfectionism Scale

- EDI

Eating Disorder Inventory

- MBSRQ

Multidimensional Body Self Relations Questionnaire

- SATAQ

Sociocultural Attitudes towards Appearance Questionnaire

Contributor Information

Shima Shahyad, Email: shima.shahyad@gmail.com.

Shahla Pakdaman, Email: pakdaman.shahla@gmail.com.

Omid Shokri, Email: oshokri@yahoo.com.

References

- 1.Thompson JK, Smolak L. Body image, eating disorders, and obesity in youth: Assessment, prevention, and treatment: Taylor & Francis; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thompson JK, Heinberg LJ, Altabe M, et al. Exacting beauty: Theory, assessment, and treatment of body image disturbance: American Psychological Association 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Keery H, Van den Berg P, Thompson JK. An evaluation of the Tripartite Influence Model of body dissatisfaction and eating disturbance with adolescent girls. Body image 2004;1(3):237-251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shroff H, Thompson JK. The tripartite influence model of body image and eating disturbance: A replication with adolescent girls. Body Image 2006;3(1):17-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van den Berg P, Thompson JK, Obremski-Brandon K, et al. The Tripartite Influence model of body image and eating disturbance: a covariance structure modeling investigation testing the mediational role of appearance comparison. J Psychosom Res 2002;53(5):1007-1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rodgers R, Chabrol H, Paxton SJ. An exploration of the tripartite influence model of body dissatisfaction and disordered eating among Australian and French college women. Body Image 2011;8(3):208-215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Geriatric Nursing (New York NYD, Coda Calico Jasmine. Model Fit Comparison for Two Competing Models of Body Dissatisfaction. University of Akron; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vartanian LR, Dey S. Self-concept clarity, thin-ideal internalization, and appearance-related social comparison as predictors of body dissatisfaction. Body Image 2013;10(4):495-500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Francisco R, Espinoza P, Gonzalez ML, et al. Body dissatisfaction and disordered eating among Portuguese and Spanish adolescents: The role of individual characteristics and internalisation of sociocultural ideals. J Adolesc 2015;41:7-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pokrajac-Bulian A, Ambrosi-Randić N, Kukić M. Thin-ideal internalization and comparison process as mediators of social influence and psychological functioning in the development of disturbed eating habits in Croatian college females. Psihologijske teme 2008;17(2):221-245. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol 1986;51(6):1173-1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bardone-Cone AM, Wonderlich SA, Frost RO, et al. Perfectionism and eating disorders: current status and future directions. Clin Psychol Rev 2007;27(3):384-405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boone L, Soenens B, Braet C. Perfectionism, body dissatisfaction, and bulimic symptoms: The intervening role of perceived pressure to be thin and thin ideal internalization. J Soc Clin Psychol 2011;30(10):1043. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Furnham A, Badmin N, Sneade I. Body image dissatisfaction: gender differences in eating attitudes, self-esteem, and reasons for exercise. J Psychol 2002;136(6):581-596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Campbell JD, Trapnell PD, Heine SJ, et al. Self-concept clarity: Measurement, personality correlates, and cultural boundaries. J Pers Soc Psychol 1996;70(1):141. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vartanian LR. When the body defines the self: Self-concept clarity, internalization, and body image. J Soc Clin Psychol 2009;28(1):94. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Srivastava K. Conceptualization and development of the appearance perfectionism scale: Preliminary evidence for validity and utility in a college student population. Citeseer 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rosenberg M. Society and the adolescent self-image 1965. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shapurian R, Hojat M, Nayerahmadi H. Psychometric characteristics and dimensionality of a Persian version of Rosenberg Self-esteem Scale. Percept Mot Skills 1987;65(1):27-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Garner DM, Olmstead MP, Polivy J. Development and validation of a multidimensional eating disorder inventory for anorexia nervosa and bulimia. Int J Eat Disord 1983;2(2):15-34. [Google Scholar]

- 21.K szavMaRT. The Mediating Role of Maladaptive Core Beliefs and Eating Di.sorder Beliefs in the Relationship between Parental Bonding and Eating Disorder Symptoms. Advances in Cognitive Science, 2010;11:4. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thompson JK, Heinberg L, Tantleff-Dunn S. The physical appearance comparison scale. The Behavior Therapist 1991;14:174. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Keery H, Boutelle K, van den Berg P, et al. The impact of appearance-related teasing by family members. J Adolesc Health 2005;37(2):120-127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jackson T, Chen H. Sociocultural predictors of physical appearance concerns among adolescent girls and young women from China. Sex Roles 2008;58(5-6):402-411. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Garrusi B Baneshi MR.. Eating Disorders and Their Associated Risk Factors among Iranian Population – A Community Based Study. Global Journal of Health Science 2013;5(1):193-202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cash TF. The body image workbook: An 8-step program for learning to like your looks: New Harbinger Publications, Inc 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 27.A R. Evolutionary Study of body image and its relationship with self-esteem based on comparison between adolescent, middle age and old people[Dissertation in persian]. Tehran: Shahed University; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schaefer LM, Burke NL, Thompson JK, et al. Development and validation of the Sociocultural Attitudes Towards Appearance Questionnaire-4 (SATAQ-4). Psychol Assess 2015;27(1):54-67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Llorente E, Gleaves DH, Warren CS, et al. Translation and validation of a Spanish version of the Sociocultural Attitudes Towards Appearance Questionnaire-4 (SATAQ-4). Int J Eat Disord 2015;48(2):170-175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Festinger L. A theory of social comparison processes. Human relations 1954;7(2):117-140. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Patrick H, Neighbors C, Knee CR. Appearance-related social comparisons: the role of contingent self-esteem and self-perceptions of attractiveness. Pers Soc Psychol Bull 2004;30(4):501-514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Durkin SJ, Paxton SJ, Sorbello M. An integrative model of the impact of exposure to idealized female images on adolescent girls’ body satisfaction1. J Appl Soc Psychol 2007;37(5):1092-1117. [Google Scholar]

- 33.van den Berg P, Paxton SJ, Keery H, et al. Body dissatisfaction and body comparison with media images in males and females. Body Image 2007;4(3):257-268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]