Abstract

Traumatic brain injuries (TBIs) affect 2.5 million Americans per year and survivors of TBI can develop long-term impairments in physical, cognitive, and psychosocial functions. Currently, there are no treatments available to stop the long-term effects of TBI. Although the primary injury can only be prevented, there is an opportunity for intervention during the secondary injury, which persists over the course of hours to years after the initial injury. One promising strategy is to modulate destructive pathways using nucleic acid therapeutics, which can downregulate “undruggable” targets considered difficult to inhibit with small molecules; however, the delivery of these materials to the central nervous system is challenging. We engineered a neuron-targeting nanoparticle which can mediate intracellular trafficking of siRNA cargo and achieve silencing of mRNA and protein levels in cultured cells. We hypothesized that soon after an injury, nanoparticles in the bloodstream may be able to infiltrate brain tissue in the vicinity of areas with a compromised blood brain barrier (BBB). We find that, when administered systemically into animals with brain injuries, neuron-targeted nanoparticles can accumulate into the tissue adjacent to the injured site and downregulate a therapeutic candidate.

Keywords: Traumatic brain injury, nucleic acid delivery, nanoparticle, peptide, neuron targeting

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is a leading cause of death and disability for young people and it is estimated that 5.3 million people in the US live with a TBI-related disability.1 Survivors of TBI can develop life-long impairment in physical, cognitive, and psychosocial functions. Currently, clinical care of TBI patients is palliative due to the lack of therapeutics available to prevent long-term effects, indicating there is a need to develop new technology. In the sequence of events after an injury, the primary injury can only be prevented however there is an opportunity for intervention during the secondary injury. Secondary injuries can develop over the course of hours to years after the initial insult, during which a cascade of destructive pathways (e.g. glutamate excitotoxicity and inflammation) ultimately leads to cell death of neurons and glia, either as a direct result of the injury or as collateral damage.2–3 These destructive pathways can be chronically activated leading to long-term deterioration of cell populations in the brain4. As more molecular responses to dysregulated homeostasis in the brain are uncovered, one promising strategy is to mitigate destructive pathways or promote protective pathways using nucleic acid therapeutics. In particular, delivery of siRNA can downregulate gene candidates which do not have small molecule antagonists in order to exert neuroprotective properties, or as a tool to screen for potential therapeutic targets in animal models before time- and cost-intensive small molecule development is initiated. In addition to the delivery of siRNA, an increasing number of therapeutic microRNAs have been identified for intervention in brain injuries.5–7

Traversing the intact blood brain barrier (BBB) in a healthy brain remains a significant hurdle for macromolecule interventions designed to function in the central nervous system.8 Beyond entry into the tissue, siRNA cargos in particular must also navigate into cell types of interest, and escape from intracellular vesicles into the cytoplasm where they can engage the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) machinery. Nanoparticles offer a solution to achieve trafficking of systemically-administered nucleic acids, as they can protect the sensitive cargo in the vasculature and encode functions to overcome bottlenecks in both the extracellular and intracellular transport pathway. Viruses such as herpes simplex virus9 and rabies virus10 have evolved mechanisms to bypass the tightly regulated layer of endothelial cells that separates the brain from the vasculature, by hijacking retrograde transport machinery to infiltrate the brain. Even without this BBB-bypassing activity, in the context of traumatic brain injury, resulting physical breaches in vasculature may offer a window during which small molecule drugs can diffuse through the otherwise difficult-to-traverse BBB11. This strategy can also apply to the transport of nanoparticulate materials.12–13 Our group has previously engineered a peptide-based nanoparticle system for siRNA delivery that is both targeted and can mediate endosomal escape after cellular internalization using components inspired by biological systems such as viruses.14–15 This nanoparticle system was built by complexing siRNA with a peptide that incorporates in tandem two components: a membrane-interactive peptide and a targeting peptide. The application of a tumor-targeting version of this technology decreased tumor burden when applied to a model of orthotopic disseminated ovarian cancer.14 We hypothesized that these tandem peptide nanoparticles could be adapted for use in delivery of nucleic acid cargos to impact secondary cellular damage that arises in areas surrounded by compromised vasculature following TBIs.

After a TBI, neurons are a particularly vulnerable population, and their loss is thought to be responsible for the many negative repercussions found in TBI survivors.16 Nanoparticles can be encoded with the ability to target specific cell types,17–20 and once in these cells, to traffic cargo to the cytosol, which is an important consideration for siRNA delivery to engage the RISC silencing machinery. In order to target therapeutic nucleic acid cargoes to neurons, we re-engineered our tumor-targeted peptide-based delivery system to include a neuron-targeting peptide that was taken from the coat protein of rabies virus.21–22 Our re-engineered tandem peptide nanoparticle system was targeted to neurons in a modular design, and retained its ability to form sub-100 nm particles while attaining the ability to downregulate genes in neuronal cells in culture. In a mouse model of penetrating TBI, we delineated the transient time window during which nanoparticles administered intravenously are able to infiltrate into the injury site and translocate into neurons. Furthermore, nanoparticles carrying a potential therapeutic, siRNA against caspase 3, achieved downregulation of protein levels in the injured brain.

Results and Discussion

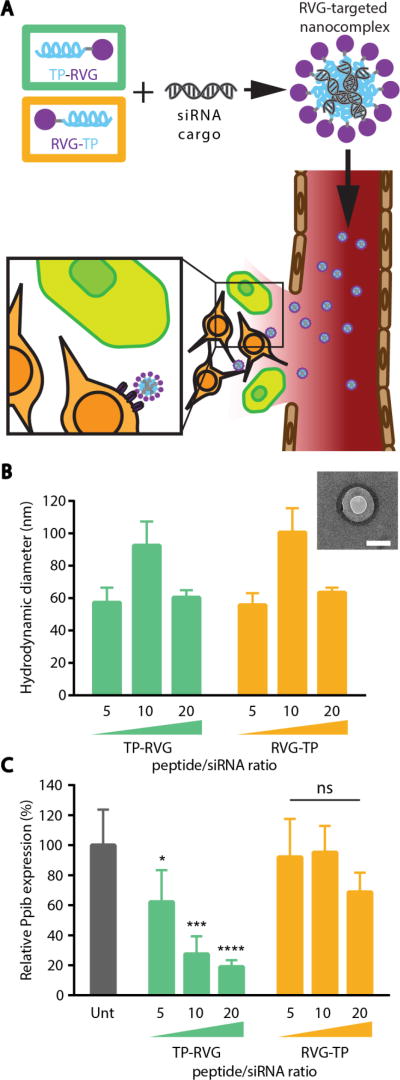

Our goal was to build a nanoparticle system that could infiltrate brain tissue by leveraging the transient access to the brain tissue that arises after a TBI23 to deliver siRNA cargo into neurons (Figure 1A). In order to target neuronal populations, a tandem peptide nanoparticle system developed in our lab was re-engineered to incorporate the targeting peptide from rabies virus, RVG.21 The optimal configuration between targeting peptide and an intracellular trafficking peptide, transportan (TP), was investigated by synthesizing either an N-terminal transportan (TP-RVG) or an N-terminal targeting peptide (RVG-TP; Figure 1A). These cationic peptides were used to determine amounts of peptide required to complex siRNA into nanoparticles. The hydrodynamic diameter of nanoparticles were measured after formulation at 20:1, 10:1, and 5:1 peptide:siRNA ratios (charge ratios of 2.86, 1.43, and 0.71, respectively). Regardless of which peptide was at the N-terminus of the tandem peptide, particles formed at the same ratio resulted in the same hydrodynamic diameters (Figure 1B), which was expected because the physicochemical properties of the peptides remain the same in both orientations. Particles increased in size at a peptide:siRNA ratio of 10:1, likely due to the phenomenon of colloid aggregation that occurs with neutral surface charges.24 Next, the particles were evaluated for their ability to mediate gene silencing of a model endogenous gene, peptidylprolyl isomerase B (Ppib), in the mouse neuroblastoma cell line, Neuro-2a (Figure 1C). Despite the two peptides forming particles at the same ratio, the formulation that incorporated transportan at the N-terminus had significantly improved gene silencing activity compared to when this peptide was located at the C-terminus.

Figure 1. Optimization of neuron-targeted nanoparticles.

(A) Schematic of neuron-targeted nanoparticle formulation with tandem peptides and siRNA and entry into injured tissue. (B) Hydrodynamic diameter of nanoparticles formulated at various peptide:siRNA ratios. Inset: TEM image of TP-RVG particle formed at 20 peptide/siRNA ratio. Scale bar represents 100 nm. (C) Knockdown activity of nanoparticles formulated at various peptide/siRNA ratios analyzed by RT-qPCR. Error bars represent SD, One-way ANOVA *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001.

A series of experiments were designed to determine why peptide with N-terminally located transportan and C-terminally located targeting peptide was more efficient at delivering siRNA. We first tested the hypothesis that this configuration of transportan and targeting peptide led to a greater binding and uptake of material by cells. Cells were incubated with the designated concentrations of nanocomplexes to determine the amount of material associated with cells when internalization pathways are active (37 °C, binding and uptake; Figure 2A) or not active (4 °C, binding only; Figure 2B). The amount of nanoparticle association was measured using flow cytometry by detecting the fluorescence of 5-carboxyfluorescein (FAM)-labeled peptide. We observed elevated cell association of nanocomplexes with N-terminal targeting peptides at both temperatures, indicating that increased particle binding and uptake was not likely to be responsible for the improved silencing efficiency mediated by N-terminal transportan conformation. Next, we tested whether the orientation of transportan influences nanoparticle escape from intracellular vesicles after internalization, by performing the assay in the presence or absence of the small molecule chloroquine. It is known that chloroquine disrupts endosomal acidification and can therefore aid in escape of nanoparticles trapped in endocytic vesicles after internalization.25 The addition of chloroquine resulted in similar levels of gene silencing for both peptide configurations with no statistical difference between the two formulations at matched peptide:siRNA ratios, as determined by one-way ANOVA analysis (Figure 2C), indicating that the N-terminal position of transportan plays a role in cytosolic delivery. The importance of N- or C-terminal orientation has been observed for other membrane-active peptides, such as melittin,26 presumably because membrane interaction is dictated by certain residues, and naturally-occurring peptides are found in specific orientations of the native protein. We also noted that in previous work, RVG was located on the N-terminus,21 but the activity of the intracellular trafficking peptide was the driving factor that dictated ~50% of the gene silencing activity in our targeted delivery system, as estimated based on our chloroquine transfection study.

Figure 2. Investigation of intracellular trafficking mechanism of tandem peptide nanoparticles.

Flow cytometric analysis of Neuro-2a cells incubated with fluorescently labeled nanoparticles at (A) 4 °C and (B) 37 °C. (C) Knockdown activity of nanoparticles in the presence of chloroquine analyzed by RT-qPCR. There was no statistical difference between knockdown with or without chloroquine at matched peptide:siRNA ratios as determined by analysis with One-way ANOVA.

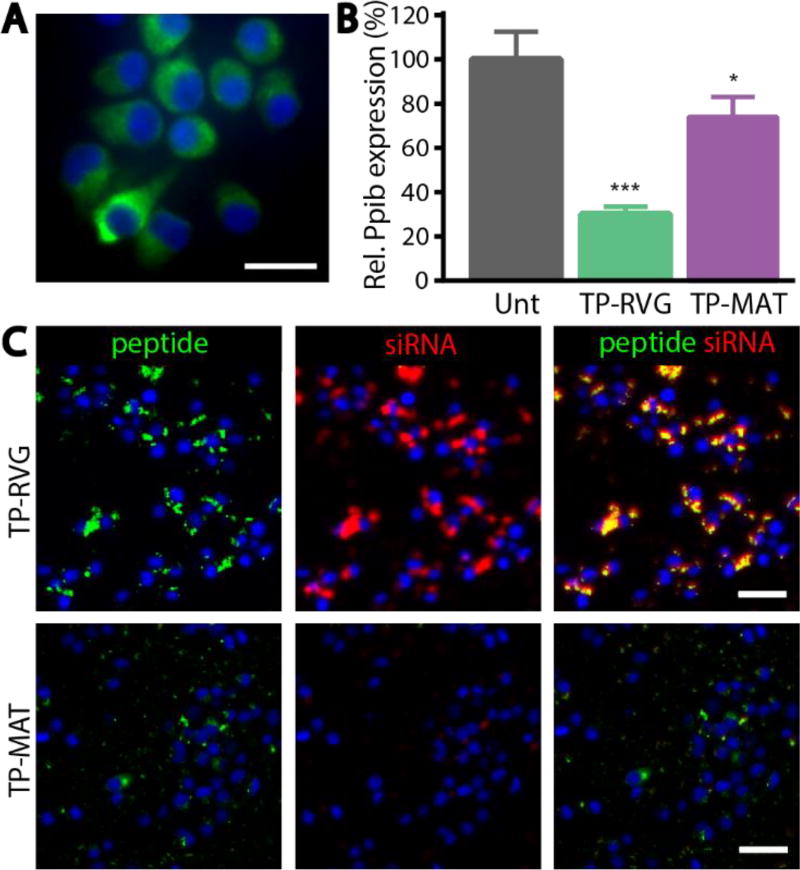

Using the optimal configuration of transportan and targeting peptide, the importance of the targeting ligand was evaluated in a neuronal cell line, Neuro-2a. Neuro-2a cells express the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (Figure 3A), a receptor that is thought to be primarily responsible for rabies virus glycoprotein binding.27 Nanoparticles were targeted with either RVG or a control peptide (MAT), a sequence taken from a different portion of the same rabies virus glycoprotein as RVG, and applied to Neuro-2a cells. MAT-targeted nanoparticles mediated significantly less knockdown of Pbib, compared with RVG-targeted nanoparticles (Figure 3B). When uptake of nanoparticles was evaluated using fluorescence microscopy by tracking FAM labeled peptides and Dylight-647 labeled siRNA, significantly less uptake of both peptide and siRNA was seen when particles were targeted with MAT compared with RVG (Figure 3C).

Figure 3. RVG peptide targeting of nanoparticles.

(A) Staining of Neuro-2a cells for expression of alpha acetylcholine receptor (green) counterstained with Hoechst (blue). Scale bar represents 20 µm. (B) Knockdown mediated by RVG and MAT targeted nanoparticles in Neuro-2a cells analyzed by RT-qPCR. Error bars represent SD, One-way ANOVA *p<0.05, ***p<0.001. (C) Accumulation of nanoparticles made with RVG or MAT peptide (green) and siRNA (red) in Neuro-2a cells after 2 hours. Scale bar represents 50 µm.

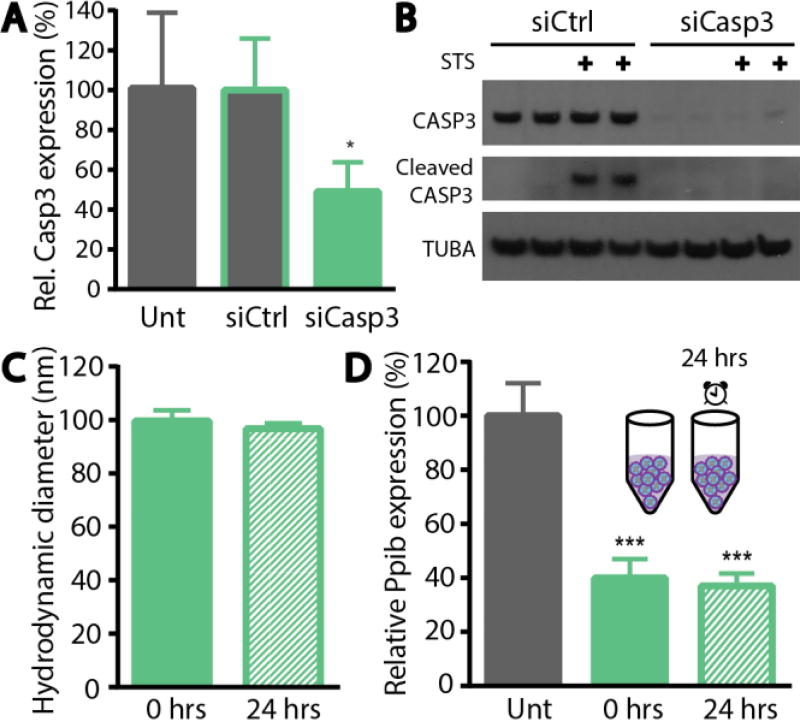

The optimized targeted nanoparticle formulation was then applied to deliver siRNA against a potential therapeutic gene. In TBIs, the secondary injuries that arise in response to the primary event include dysregulation of the BBB, edema, ectopic release of excitatory neurotransmitters, and inflammation.4 These indirect effects can occur chronically and cause widespread death of neurons in the brain over the course of hours to years after the initial injury. To prevent the apoptosis of neurons caused by the secondary injury, we delivered siRNA against caspase 3. Caspase 3 is known to be a main player in apoptosis after TBIs28 and small molecule and peptide therapies targeted to caspase 3 have been explored29–30. We first validated siRNA sequences against caspase 3 and found that levels of mRNA after caspase 3 knockdown were decreased to approximately 50% after 48 hours (Figure 4A). Since the mediator of damage is CASP3 protein, we then evaluated the ability of our targeted nanocomplex to suppress CASP3 protein levels by Western blot (Figure 4B). We found a more extensive decrease in protein levels compared with mRNA levels, with over 90% of the CASP3 protein levels decreased after siRNA treatment. To simulate neurons in apoptotic states, we probed the levels of CASP3 protein in the presence of the chemotherapeutic staurosporine, a well-documented inducer of apoptosis. Activation of the apoptotic cascade can be inferred based on the presence of the activated fragments of cleaved CASP3 (17KDa and 19KDa) in Neuro-2a cells treated with staurosporine (Figure 4B). When siCasp3 was delivered, both the zymogen and activated forms of CASP3 were significantly decreased.

Figure 4. Knockdown of therapeutic protein, CASP3.

RVG-targeted nanoparticle mediated knockdown of Caspase 3 (A) mRNA analyzed by RT-qPCR and (B) protein analyzed by western blotting. Stability of (C) hydrodynamic diameter and (D) silencing activity of RVG-targeted nanoparticle after 24 hour incubation at room temperature. Error bars represent SD, One-way ANOVA *p<0.05, ***p<0.001.

In the presented platform, neuron-targeted nanoparticles were designed to leverage the transiently compromised vasculature after a traumatic brain injury to gain access to brain tissue. Because this breach in the BBB offers only temporary access to the brain tissue, a nanoparticle treatment would be best administered within 24 hours after injury. To enable a formulation that could be deployable in the field, or wherever patients experience trauma, we tested the stability of our RVG targeted nanoparticles when stored in ambient conditions. Nanoparticles were able to maintain their size (Figure 4C) and their knockdown activity (Figure 4D) after 24 hours of storage at room temperature. Furthermore, nanoparticles stored for up to 7 days maintain their size, and likely their activity since the cargo should be protected in nanoparticle form (SI Figure 1).

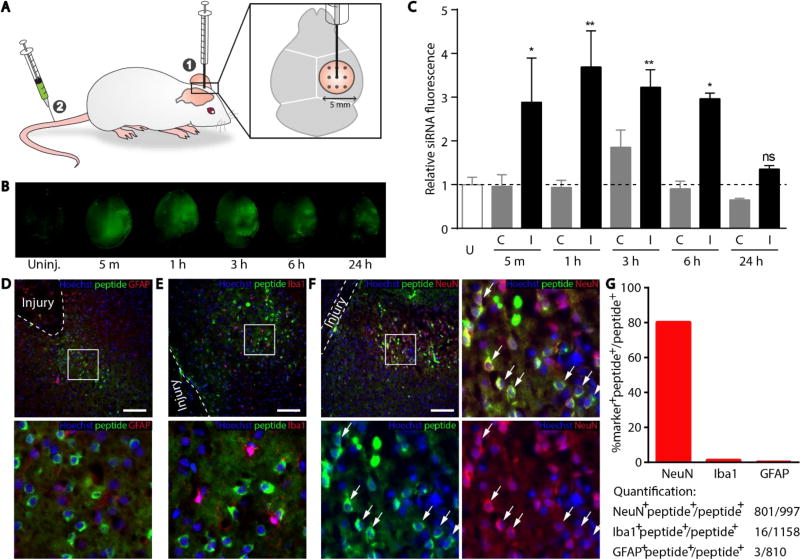

With the basic criteria of our platform credentialed in vitro, we applied our siRNA delivery carrier to an animal model of TBI. We modeled the TBI to mimic penetrating injuries using a series of needle stick wounds applied in a controlled manner via a stereotaxic apparatus (Figure 5A). The wounds were inflicted on the cortex and hippocampus of mice on only one hemisphere of the brain, whereas the contralateral hemisphere of the brain was not directly injured to serve as a control. One important caveat is that the uninjured contralateral tissue may be indirectly affected by signaling pathways that are activated in response to injury; for example changes in vascular permeability at the whole brain level have been observed in response to injury, although the mechanisms are currently unknown.12, 23 The siRNA/peptide nanocomplexes were labeled with a far-red dye, VivoTag 750, to enable sensitive detection of material in animal tissue. Sham injuries were performed by removing the skull but not inducing shear injuries in the brain tissue, in order to discriminate surgery-mediated particle accumulation from that attributable to the deeper shear injuries (SI Figure 2). When nanoparticles were administered into the circulation 5 minutes after the sham injury, we observed a modest signal increase concentrated in a ring where the skull was removed, likely caused by damaged vasculature on the dura made by the drill. There was no evidence of peptide accumulation in the deeper brain tissue in sham injured animals. In order to quantitatively observe the kinetics of vascular permeability to nanoparticles, nanoparticles were delivered intravenously 5 minutes, 1 hour, 3 hours, 6 hours, and 24 hours after injury, and brains were collected 1 hour after each delivery to assess nanoparticle infiltration (Figure 5B, 5C). Notably, the contralateral side of the injured brain displayed similar levels of nanoparticle accumulation to that observed in completely uninjured mice, supporting the interpretation that material uptake is largely driven by the conditions at the immediate injury site at least in the early response. We do note a slight increase in accumulation on the contralateral side of the brain at 1 hour after injury. Although this result was not statistically significant, it may be that the biological response to injury increases vascular permeability beyond the local site of the damaged tissue.12 We also noted that free siRNA accumulated into injured tissue to greater levels than observed with complexed siRNA, likely due to the small size and negative charge of free siRNA which prevents binding and sequestration into off-target tissue (SI Figure 3). However, free unmodified siRNA has negligible silencing activity (SI Figure 4) and is vulnerable to degradation when unprotected in the vasculature. The differential distribution between free siRNA and siRNA-nanoparticles also suggests that the nanoparticles are stable in vivo, such that the majority of siRNA remains complexed with peptide in the vasculature. On the injured hemisphere of the brain, we observed nanoparticle accumulation at the injury site up to 6 hours, followed by a significant decrease at 24 hours. This observation is consistent with other models of brain injury, where infiltration of macromolecules into the brain tissue from the blood is maximal at 6 hours after the injury, likely mitigated by progression of edema that increases local pressure.31

Figure 5. Accumulation of RVG-targeted nanoparticles in the injured brain.

(A) Schematic of the simulated TBI in mice. (B) Accumulation of fluorescently labeled particles in the injured hemisphere (right) when administered intravenously 5 min, 1 h, 3 h, 6, h and 24 h after injury. Uninjured brain administered particles serves as a control. (C) Quantification of nanoparticle accumulation in the contralateral (C) versus injured (I) hemisphere. Dotted line represents an uninjured (U) animal injected with nanoparticles. Error bars represent SEM, One-way ANOVA, n=3 *p<0.05, **p<0.01. 10 µm sections taken from brain administered nanoparticles 5 minutes after injury and stained for nuclei (blue), FAM-labeled peptide (green), and (D) astrocytes (red; GFAP), (E) microglia (red; Iba1), or (F) neurons (red; NeuN). White dashed line markers the boundary of shear injury, the box indicates magnified inset (bottom), and arrows denote cells which stain positively for both NeuN and peptide. Scale bar represents 100 µm. (G) Quantification of total counts and percentages of NeuN, Iba1, and GFAP positive populations from images.

To more specifically localize the delivered material within the brain tissue, brains were sectioned and stained for peptide using an anti-fluorescein antibody combined with staining for glia using the marker glial fibrillary acid protein (GFAP; Figure 5D), microglia using the marker ionized calcium binding adaptor molecule 1 (Iba1; Figure 5E), or neurons using the marker NeuN (Figure 5F). There was no detectable peptide material observed in glia and microglia (Figure 5D–E). In contrast, inspecting the neuronal population in the cortex near sites of the injury revealed that although not all neurons at the injured site are associated with detectable levels of peptide, the majority of peptide signal localized with neurons (Figure 5F). The reputed receptor for rabies virus, and presumably RVG peptide, is the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor27. We stained sections with a fluorophore-labeled α-bungarotoxin, a high affinity ligand for the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor, and found that while some co-localization of peptide with α-bungarotoxin positive cells was evident, we also observed examples of peptide localized in cells not positive for α-bungarotoxin (SI Figure 5). Possible explanations for this observation are: alternative protein complexes are thought to have a role in rabies virus binding and entry32, and the peptide from the rabies virus used in our particles may not be sufficient to confer the same specificity as the full protein. In order to quantitatively support the microscopy images, we counted GFAP+, Iba1+, and NeuN+ cells that co-stained peptide+ cells observed in several fields of view from brain sections of three different mice (Figure 5G). The peptide+NeuN+ double positive cells were 80% of the total peptide+ population, whereas peptide+GFAP+ and peptide+Iba1+ double positive cells were less than 2% each of the total peptide+ population, supporting that the majority of material was trafficked to neuronal cells.

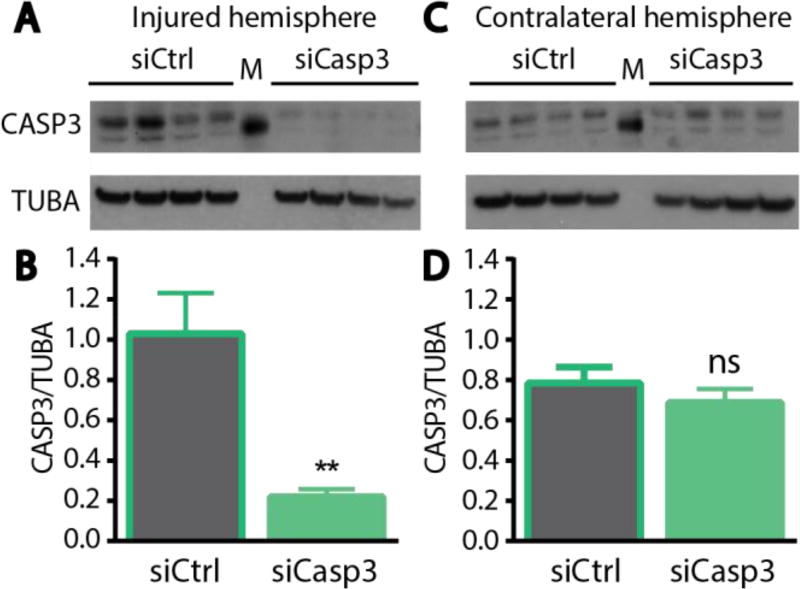

Based on the observations that neuron-targeted nanocomplexes accumulated at the site of injury and delivered material was taken up by neurons, we administered nanocomplexes carrying a therapeutic gene and evaluated their ability to mediate protein knockdown in regions proximal to the injury site. We employed the same penetrating injury model of TBI used above, and nanoparticles carrying either control siRNA or siRNA against CASP3 were delivered intravenously 5 minutes after the injury. Three days post-injury, brains were dissected to isolate the injured area of the cortex, as well as the corresponding tissue region on the contralateral uninjured hemisphere. The resulting tissue samples were processed for analysis of protein expression by Western blotting. A decrease in CASP3 protein levels was observed in the injured hemisphere when siCasp3 was administered, relative to the delivery of siCtrl (Figure 6A). Quantification of these results showed ~80% knockdown of CASP3 in the damaged region of the injured hemisphere (Figure 6B). By contrast, in the contralateral hemisphere, no knockdown was observed following either nanoparticle treatment (Figure 6C, D). Lack of silencing in the contralateral hemisphere was consistent with the limited particle accumulation observed in this side of the brain (Figure 5C).

Figure 6. In vivo knockdown of CASP3 in a mouse model of traumatic brain injury.

Western blot of lysates and quantification of blots from the (A, B) injured hemisphere or the (C, D) contralateral hemisphere. Error bars represent SEM, Student’s t-test **p<0.01, ns = not significant.

Conclusions

TBI remains a major cause of disability with no therapeutic treatments available. The delivery of nanoparticles into the central nervous system for nucleic acid delivery has remained a challenge due to the poor permeability of the BBB to nanoparticles and the requirement to localize nucleic acid cargoes to the cytosol or nucleus of cells. Existing approaches have focused on local delivery of material, either into the cerebrospinal fluid reservoirs33–34 or direct administration into the brain tissue.35–36 Other approaches include the use of small molecules37 or ultrasound38–39 to alter the BBB to induce transient permeabilization of the BBB for nanoparticle transport. In the presented work, we envisioned a therapeutic that could take advantage of the BBB breach arising immediately after a penetrating injury and therefore could be administered in the field via an intravenous delivery route. We designed a targeted nanoparticle inspired by previous technology from our lab developed for cancer therapeutics which utilizes an intracellular trafficking peptide and a targeting peptide joined in tandem to self-assemble with siRNA into nanometer-sized structures. Re-engineering these nanoparticles to target neurons using a peptide ligand produced a system capable of mediating silencing in cultured cells that express the proposed target receptor. Intravenous application of these nanoparticles to an in vivo model of TBI transiently allows significant accumulation of nanoparticles if administered within a 6 hour window after the onset of injury. Observations in the literature suggest that this window is limited in the short-term by biological cascades that are produced by the injury such as intravascular coagulation and edema.31, 40 Furthermore, targeted nanoparticles were found to accumulate in neurons and were able to silence a candidate therapeutic gene in the region proximal to the injury. The RVG targeting ligand has been used previously to mediate transport of nanostructured materials across an intact BBB when decorated on electrostatic complexed nanoparticles21, 37 and exosomes22, 41. Another aspect of CNS delivery that is being explored is the delivery of targeted materials in disease states,42–43 where there may be altered BBB permeability. In this work we sought to characterize nanoparticle infiltration from the systemic vasculature when administered in the context of a TBI and furthermore, the ability to deliver nucleic acid cargo to targeted cell populations. We observed that there was significantly increased accumulation of nanoparticles in injured brain tissue compared to uninjured brains after intravenous delivery (Figure 5C), and in this context, a targeting ligand could achieve neuron-specific uptake. Future studies could explore long-term effects of therapeutic siRNA delivery in animals, such as looking at retention of neuronal populations and performance in behavioral tasks. Altering vascularization to coordinate nanoparticle accumulation has been harnessed in the context of tumor delivery in our lab and others,43–45 but this strategy has not been explored extensively in the context of the central nervous system, to date. Because our tandem peptide system is modular, siRNA against new targets can be rapidly synthesized and incorporated into nanoparticles to mitigate long-term effects of TBI.

Methods

Cell culture

Neuro-2a cells were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection and maintained in EMEM supplemented with 10% FBS.

Nanoparticle complexation

The appropriate molar ratio of peptide:siRNA were formulated into nanoparticles by adding peptide solutions to equivolume of siRNA in water and mixing rapidly. TP-RVG (GGWTLNSAGYLLGKINLKALAALAKKILGGK(FAM)GGYTIWMPENPRPGTPCDIFTNSRGKRASNG), RVG-TP (YTIWMPENPRPGTPCDIFTNSRGKRASNGGGK (FAM) GGGGWTLNSAGYLLGKINLKALAALAKKIL) and TP-MAT (GGWTLNSAGYLLGKINLKALAALAKKILGGK (FAM) GGMNLLRKIVKNRRDEDTQKSSPASAPLDDG) were synthesized by CPC Scientific with N-terminal myristic acid. siRNA were synthesized by Dharmacon (siCtrl = CUUACGCUGAGUACUUCGA (sequence against firefly luciferase), siPPIB 1 = CAAGUUCCAUCGUGUCAUC, siPPIB 2 = GAAAGAGCAUCUAUGGUGA, CASP3 1 = GGAUAGUGUUUCUAAGGAA, CASP3 2 = CGCACAAGCUAGAAUUUAU).

Dynamic Light Scattering and Transmission Electron Microscopy

Nanoparticle solutions were incubated for 10 minutes after formulation. Hydrodynamic diameters were measured in a Malvern Zetasizer in water. Particles were deposited on a 200 mesh Formvar/Carbon mesh (Ted Pella Inc.) and dried. Particles were imaged on a JEOL 2100 FEG TEM.

Transfection

Neuro-2a cells were plated at 80K cells per well in 24-well plates coated with 10 ug/mL Poly-D-Lysine 24 hours before transfection. Nanocomplexes were added to cells in OptiMEM at a final concentration of 100 nM and four hours after addition, the media was replaced with full culture medium. Cells were collected for downstream RT-qPCR or western blot analysis 48 hours after transfection. For relative protein quantification of western blots, films were analyzed using the Gels tool in ImageJ by calculating the area under the curve of sample lanes converted to 2D plots. For transfections done in the presence of chloroquine, nanoparticles were co-incubated with 100 nM chloroquine for 4 hours before the media was changed.

Cell association studies

Cells were co-incubated with nanoparticles with the designated final peptide concentrations as described in the transfection. For 4 °C association studies, plates were incubated on ice for 30 minutes before the addition of nanoparticles. Cells were harvested using trypsin and analyzed for positive FAM fluorescence on the peptides. For microscopic examination, Dylight-647 siRNA was used to make complexes. After 4 hours of incubation, cells were fixed, counterstained with Hoechst (Sigma-Aldrich) and visualized on a Nikon Eclipse Ti.

Injury model

All animal protocols were done in accordance with the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. 6–8 week old C57BL/6 mice were obtained from Taconic and were fitted into a stereotaxic device. A 5 mm diameter portion of the skull was removed and a 19G needle was used to make a series of shear injuries 3 mm deep and 1 mm apart. For biodistribution, 1 nmole of siRNA labeled with VivoTag750 on the 5’ end of the sense strand was used. At the times designated, mice were anesthetized with isoflurane and perfused with 10% formalin and the brains were imaged on a LI-COR Odyssey using the 800 channel. For knockdown studies, 2 nmoles of siRNA were administered via the tail-vein after the injury in a solution of 5% dextrose 5 minutes following the injury. Mice were sacrificed via CO2 asphyxiation 72 hours after administration of particles, and fresh tissue was collected and immediately frozen for protein analysis. The injured cortex was dissected along with the uninjured contralateral tissue for western blotting. Western blots were probed with antibodies against caspase 3 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.; 1:500), cleaved caspase 3 (Cell Signaling Technology; 1:1000), and alpha-tubulin (Invitrogen; 1:1000).

Staining of brain sections and quantification

Mice were perfused with fixative and brains were fixed for an additional 16 hours. Brains were equilibrated into 30% sucrose solution, embedded into Optimum Cutting Temperature compound (Sakura Finetek), frozen on dry ice, and cut into 10 µm sections. Sections were blocked in 10% goat serum, 2% BSA, 0.1% TritonX-100 in PBS and probed with anti-NeuN (Millipore; 1:800), anti-GFAP (Abcam, 1:500), anti-Iba1 (Abcam, 1:500), and anti-fluorescein (Thermo Fisher; 1:200) antibodies. Appropriate fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibodies (Jackson Immunolabs) were used to visualize primary antibodies. Several fields of view were imaged using fluorescence microscopy and counting of NeuN, Iba1, and GFAP and peptide double positive populations was done in ImageJ.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the Koch Institute Swanson Biotechnology Center (MIT) for assistance with TEM imaging, specifically Dr. Dong Soo Yun, and tissue sectioning, specifically Michael Brown and Kathleen Cormier. We thank Dr. Heather Fleming (MIT) for critical reading and editing of the manuscript. This work was supported in part by the Marie-D. & Pierre Casimir-Lambert Fund, and a Koch Institute Support Grant P30-CA14051 from the National Cancer Institute (Swanson Biotechnology Center) and a Core Center Grant P30-ES002109 from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences. This work was also supported by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency under Cooperative Agreement HR0011-13-2-0017. The content of the information within this document does not necessarily reflect the position or the policy of the Government. E. Kwon acknowledges support from the Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award (1F32CA177094-01). S. Bhatia is an HHMI Investigator.

Footnotes

Author Contributions

The manuscript was written through contributions of all authors. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

Supporting Information Available: Free siRNA distribution in the injured brain. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Roozenbeek B, Maas AI, Menon DK. Changing Patterns in the Epidemiology of Traumatic Brain Injury. Nat Rev Neurol. 2013;9(4):231–6. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2013.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xiong Y, Mahmood A, Chopp M. Animal Models of Traumatic Brain Injury. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2013;14(2):128–42. doi: 10.1038/nrn3407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cernak I, Noble-Haeusslein LJ. Traumatic Brain Injury: An Overview of Pathobiology with Emphasis on Military Populations. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2010;30(2):255–66. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2009.203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Werner C, Engelhard K. Pathophysiology of Traumatic Brain Injury. Br J Anaesth. 2007;99(1):4–9. doi: 10.1093/bja/aem131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ge XT, Lei P, Wang HC, Zhang AL, Han ZL, Chen X, Li SH, Jiang RC, Kang CS, Zhang JN. miR-21 Improves the Neurological Outcome after Traumatic Brain Injury in Rats. Sci Rep. 2014;4:6718. doi: 10.1038/srep06718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bhalala OG, Srikanth M, Kessler JA. The Emerging Roles of MicroRNAs in CNS Injuries. Nat Rev Neurol. 2013;9(6):328–39. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2013.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saugstad JA. MicroRNAs as Effectors of Brain Function with Roles in Ischemia and Injury, Neuroprotection, and Neurodegeneration. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2010;30(9):1564–76. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2010.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pardridge WM. Drug Transport across the Blood-Brain Barrier. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2012;32(11):1959–72. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2012.126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sodeik B, Ebersold MW, Helenius A. Microtubule-Mediated Transport of Incoming Herpes Simplex Virus 1 Capsids to the Nucleus. J Cell Biol. 1997;136(5):1007–21. doi: 10.1083/jcb.136.5.1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schnell MJ, McGettigan JP, Wirblich C, Papaneri A. The Cell Biology of Rabies Virus: Using Stealth to Reach the Brain. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2010;8(1):51–61. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shlosberg D, Benifla M, Kaufer D, Friedman A. Blood-Brain Barrier Breakdown as a Therapeutic Target in Traumatic Brain Injury. Nat Rev Neurol. 2010;6(7):393–403. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2010.74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith NM, Gachulincova I, Ho D, Bailey C, Bartlett CA, Norret M, Murphy J, Buckley A, Rigby PJ, House MJ, St Pierre T, Fitzgerald M, Iyer KS, Dunlop SA. An Unexpected Transient Breakdown of the Blood Brain Barrier Triggers Passage of Large Intravenously Administered Nanoparticles. Sci Rep. 2016;6:22595. doi: 10.1038/srep22595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cruz LJ, Stammes MA, Que I, van Beek ER, Knol-Blankevoort VT, Snoeks TJ, Chan A, Kaijzel EL, Lowik CW. Effect of PLGA NP Size on Efficiency to Target Traumatic Brain Injury. J Control Release. 2016;223:31–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2015.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ren Y, Cheung HW, von Maltzhan G, Agrawal A, Cowley GS, Weir BA, Boehm JS, Tamayo P, Karst AM, Liu JF, Hirsch MS, Mesirov JP, Drapkin R, Root DE, Lo J, Fogal V, Ruoslahti E, Hahn WC, Bhatia SN. Targeted Tumor-Penetrating siRNA Nanocomplexes for Credentialing the Ovarian Cancer Oncogene ID4. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4(147):147ra112. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ren Y, Hauert S, Lo JH, Bhatia SN. Identification and Characterization of Receptor-Specific Peptides for siRNA Delivery. ACS Nano. 2012;6(10):8620–31. doi: 10.1021/nn301975s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Raghupathi R. Cell Death Mechanisms Following Traumatic Brain Injury. Brain Pathol. 2004;14(2):215–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2004.tb00056.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Davis ME, Zuckerman JE, Choi CH, Seligson D, Tolcher A, Alabi CA, Yen Y, Heidel JD, Ribas A. Evidence of RNAi in Humans from Systemically Administered siRNA via Targeted Nanoparticles. Nature. 2010;464(7291):1067–70. doi: 10.1038/nature08956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schroeder A, Heller DA, Winslow MM, Dahlman JE, Pratt GW, Langer R, Jacks T, Anderson DG. Treating Metastatic Cancer with Nanotechnology. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12(1):39–50. doi: 10.1038/nrc3180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Choi CH, Alabi CA, Webster P, Davis ME. Mechanism of Active Targeting in Solid Tumors with Transferrin-Containing Gold Nanoparticles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(3):1235–40. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914140107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ruoslahti E, Bhatia SN, Sailor MJ. Targeting of Drugs and Nanoparticles to Tumors. J Cell Biol. 2010;188(6):759–68. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200910104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kumar P, Wu H, McBride JL, Jung KE, Kim MH, Davidson BL, Lee SK, Shankar P, Manjunath N. Transvascular Delivery of Small Interfering RNA to the Central Nervous System. Nature. 2007;448(7149):39–43. doi: 10.1038/nature05901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alvarez-Erviti L, Seow Y, Yin H, Betts C, Lakhal S, Wood MJ. Delivery of siRNA to the Mouse Brain by Systemic Injection of Targeted Exosomes. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29(4):341–5. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Price L, Wilson C, Grant G. Blood-Brain Barrier Pathophysiology Following Traumatic Brain Injury. In: Laskowitz D, Grant G, editors. Translational Research in Traumatic Brain Injury. Boca Raton (FL): 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.El Badawy AM, Luxton TP, Silva RG, Scheckel KG, Suidan MT, Tolaymat TM. Impact of Environmental Conditions (pH, Ionic Strength, and Electrolyte Type) on the Surface Charge and Aggregation of Silver Nanoparticles Suspensions. Environ Sci Technol. 2010;44(4):1260–6. doi: 10.1021/es902240k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cheng J, Zeidan R, Mishra S, Liu A, Pun SH, Kulkarni RP, Jensen GS, Bellocq NC, Davis ME. Structure-Function Correlation of Chloroquine and Analogues as Transgene Expression Enhancers in Nonviral Gene Delivery. J Med Chem. 2006;49(22):6522–31. doi: 10.1021/jm060736s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boeckle S, Wagner E, Ogris M. C-versus N-Terminally Linked Melittin-Polyethylenimine Conjugates: The Site of Linkage Strongly Influences Activity of DNA Polyplexes. J Gene Med. 2005;7(10):1335–47. doi: 10.1002/jgm.783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hanham CA, Zhao F, Tignor GH. Evidence from the Anti-Idiotypic Network That the Acetylcholine Receptor Is a Rabies Virus Receptor. J Virol. 1993;67(1):530–42. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.1.530-542.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Clark RS, Kochanek PM, Watkins SC, Chen M, Dixon CE, Seidberg NA, Melick J, Loeffert JE, Nathaniel PD, Jin KL, Graham SH. Caspase-3 Mediated Neuronal Death after Traumatic Brain Injury in Rats. J Neurochem. 2000;74(2):740–53. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.740740.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cheng Y, Deshmukh M, D'Costa A, Demaro JA, Gidday JM, Shah A, Sun Y, Jacquin MF, Johnson EM, Holtzman DM. Caspase Inhibitor Affords Neuroprotection with Delayed Administration in a Rat Model of Neonatal Hypoxic-Ischemic Brain Injury. J Clin Invest. 1998;101(9):1992–9. doi: 10.1172/JCI2169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Han BH, Xu D, Choi J, Han Y, Xanthoudakis S, Roy S, Tam J, Vaillancourt J, Colucci J, Siman R, Giroux A, Robertson GS, Zamboni R, Nicholson DW, Holtzman DM. Selective, Reversible Caspase-3 Inhibitor Is Neuroprotective and Reveals Distinct Pathways of Cell Death after Neonatal Hypoxic-Ischemic Brain Injury. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(33):30128–36. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202931200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baskaya MK, Rao AM, Dogan A, Donaldson D, Dempsey RJ. The Biphasic Opening of the Blood-Brain Barrier in the Cortex and Hippocampus after Traumatic Brain Injury in Rats. Neurosci Lett. 1997;226(1):33–6. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(97)00239-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lafon M. Rabies Virus Receptors. J Neurovirol. 2005;11(1):82–7. doi: 10.1080/13550280590900427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kwon EJ, Lasiene J, Jacobson BE, Park IK, Horner PJ, Pun SH. Targeted Nonviral Delivery Vehicles to Neural Progenitor Cells in the Mouse Subventricular Zone. Biomaterials. 2010;31(8):2417–24. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.11.086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bharali DJ, Klejbor I, Stachowiak EK, Dutta P, Roy I, Kaur N, Bergey EJ, Prasad PN, Stachowiak MK. Organically Modified Silica Nanoparticles: A Nonviral Vector for In Vivo Gene Delivery and Expression in the Brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(32):11539–44. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504926102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rungta RL, Choi HB, Lin PJ, Ko RW, Ashby D, Nair J, Manoharan M, Cullis PR, Macvicar BA. Lipid Nanoparticle Delivery of siRNA to Silence Neuronal Gene Expression in the Brain. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids. 2013;2:e136. doi: 10.1038/mtna.2013.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Al-Jamal KT, Gherardini L, Bardi G, Nunes A, Guo C, Bussy C, Herrero MA, Bianco A, Prato M, Kostarelos K, Pizzorusso T. Functional Motor Recovery from Brain Ischemic Insult by Carbon Nanotube-Mediated siRNA Silencing. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(27):10952–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1100930108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hwang do W, Son S, Jang J, Youn H, Lee S, Lee D, Lee YS, Jeong JM, Kim WJ, Lee DS. A Brain-Targeted Rabies Virus Glycoprotein-Disulfide Linked PEI Nanocarrier for Delivery of Neurogenic MicroRNA. Biomaterials. 2011;32(21):4968–75. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.03.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nance E, Timbie K, Miller GW, Song J, Louttit C, Klibanov AL, Shih TY, Swaminathan G, Tamargo RJ, Woodworth GF, Hanes J, Price RJ. Non-Invasive Delivery of Stealth, Brain-Penetrating Nanoparticles across the Blood-Brain Barrier Using MRI-Guided Focused Ultrasound. J Control Release. 2014;189:123–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2014.06.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mulik RS, Bing C, Ladouceur-Wodzak M, Munaweera I, Chopra R, Corbin IR. Localized Delivery of Low-Density Lipoprotein Docosahexaenoic Acid Nanoparticles to the Rat Brain Using Focused Ultrasound. Biomaterials. 2016;83:257–68. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2016.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chodobski A, Zink BJ, Szmydynger-Chodobska J. Blood-Brain Barrier Pathophysiology in Traumatic Brain Injury. Transl Stroke Res. 2011;2(4):492–516. doi: 10.1007/s12975-011-0125-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu Y, Li D, Liu Z, Zhou Y, Chu D, Li X, Jiang X, Hou D, Chen X, Chen Y, Yang Z, Jin L, Jiang W, Tian C, Zhou G, Zen K, Zhang J, Zhang Y, Li J, Zhang CY. Targeted Exosome-Mediated Delivery of Opioid Receptor Mu siRNA for the Treatment of Morphine Relapse. Sci Rep. 2015;5:17543. doi: 10.1038/srep17543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lee J, Min HS, You DG, Kim K, Kwon IC, Rhim T, Lee KY. Theranostic Gas-Generating Nanoparticles for Targeted Ultrasound Imaging and Treatment of Neuroblastoma. J Control Release. 2016;223:197–206. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2015.12.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu Y, Guo Y, An S, Kuang Y, He X, Ma H, Li J, Lu J, Zhang N, Jiang C. Targeting Caspase-3 as Dual Therapeutic Benefits by RNAi Facilitating Brain-Targeted Nanoparticles in a Rat Model of Parkinson's Disease. PLoS One. 2013;8(5):e62905. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lin KY, Kwon EJ, Lo JH, Bhatia SN. Drug-Induced Amplification of Nanoparticle Targeting to Tumors. Nano Today. 2014;9(5):550–559. doi: 10.1016/j.nantod.2014.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chauhan VP, Stylianopoulos T, Martin JD, Popovic Z, Chen O, Kamoun WS, Bawendi MG, Fukumura D, Jain RK. Normalization of Tumour Blood Vessels Improves the Delivery of Nanomedicines in a Size-Dependent Manner. Nat Nanotechnol. 2012;7(6):383–8. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2012.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.