Abstract

Background

Breast cancer is the most frequent cancer among women worldwide. Biomarkers for early detection and prognosis of these patients are needed. We hypothesized that deafness, autosomal dominant 5 (DFNA5) may be a valuable biomarker, based upon strong indications for its role as tumor suppressor gene and its function in regulated cell death. In this study, we aimed to analyze DFNA5 methylation and expression in the largest breast cancer cohort to date using publicly available data from TCGA, in order to further unravel the role of DFNA5 as detection and/or prognostic marker in breast cancer. We analyzed Infinium HumanMethylation450k data, covering 22 different CpGs in the DFNA5 gene (668 breast adenocarcinomas and 85 normal breast samples) and DFNA5 expression (Agilent 244K Custom Gene Expression: 476 breast adenocarcinomas and 56 normal breast samples; RNA-sequencing: 666 breast adenocarcinomas and 71 normal breast samples).

Results

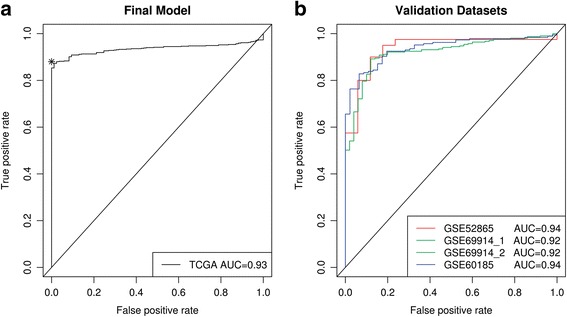

DFNA5 methylation and expression were significantly different between breast cancer and normal breast samples. Overall, breast cancer samples showed higher DFNA5 methylation in the putative gene promoter compared to normal breast samples, whereas in the gene body and upstream of the putative gene promoter, the opposite is true. Furthermore, DFNA5 methylation, in 10 out of 22 CpGs, and expression were significantly higher in lobular compared to ductal breast cancers. An important result of this study was the identification of a combination of one CpG in the gene promoter (CpG07504598) and one CpG in the gene body (CpG12922093) of DFNA5, which was able to discriminate between breast cancer and normal breast samples (AUC = 0.93). This model was externally validated in three independent datasets. Moreover, we showed that estrogen receptor state is associated with DFNA5 methylation and expression. Finally, we were able to find a significant effect of DFNA5 gene body methylation on a 5-year overall survival time.

Conclusions

We conclude that DFNA5 methylation shows strong potential as detection and prognostic biomarker for breast cancer.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s13148-018-0479-y) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: DFNA5, Methylation, Breast cancer, Detection biomarker, Prognostic biomarker, TCGA

Background

Breast cancer is the most frequent cancer among women, with nearly 1.67 million new cases diagnosed in 2012 [1]. It is a heterogeneous disease consisting of two main histological subtypes, ductal and lobular adenocarcinomas, that differ with respect to clinical presentation, morphological and molecular features, and clinical behavior [2–5]. Breast cancer ranks as the most frequent and second most frequent cause of cancer-related mortality in women in less developed and more developed regions, respectively [1]. The high mortality can partly be explained by late detection. Therefore, the World Health Organization emphasizes that: “early diagnosis in order to improve breast cancer outcome and survival remains the cornerstone of breast cancer control” [6]. Until now, the only early detection method for breast cancer with proven efficacy is mammography screening. Although there is evidence that mammography screening programs can reduce breast cancer mortality, there is a narrow balance of benefits compared with harms, particularly in respect to overdiagnosis and overtreatment [7]. Therefore, identification of new highly specific biomarkers enabling early detection is much needed.

Over the last years, increasing evidence for a role of epigenetic mechanisms in (breast) cancer development and progression has been obtained. Inactivation of tumor suppressor genes through DNA methylation and histone modifications, together with global hypomethylation leading to increased genomic instability, are hallmarks of cancer [8–14]. Moreover, epigenetic modifications are believed to be early events in breast cancer development due to their presence even in carcinoma in situ lesions, which makes them very suitable as early detection biomarkers [15–21]. The identification of methylation markers that are sensitive and specific for (breast) cancer may contribute to early detection. We hypothesize that DFNA5 may be a valuable epigenetic biomarker, based upon large differences in DFNA5 methylation between breast cancer and healthy breast tissues, strong indications for its role as tumor suppressor gene, and its function in regulated cell death.

The deafness, autosomal dominant 5 (DFNA5; also known as ICERE or GSDME) gene was identified in our lab in 1998 [22]. We have demonstrated that DFNA5 has the capacity to induce regulated cell death [23–25]. Recently, DFNA5 has been in the spotlight as Rogers et al. showed that caspase-3 cleaves DFNA5 to generate a necrotic DFNA5-N fragment. This fragment targets the plasma membrane and permeabilizes it by forming DFNA5 pores. Thereby, DFNA5 induces secondary necrosis, which is a lytic and inflammatory phase that occurs when apoptotic cells are not scavenged [26]. Soon after Rogers’ publication, several other papers pointed towards an important role for DFNA5 in secondary necrosis and its possible pathophysiological and therapeutic implications, especially in cancer [27–30]. Moreover, genomic methylation screens unveiled DFNA5 as a possible tumor suppressor gene [31–33]. Epigenetic silencing through DFNA5 methylation was previously shown in gastric [31], colorectal [32, 34], and breast cancer [35] on a limited number of samples. Recently, we performed methylation analysis on four CpGs in the DFNA5 promoter region using bisulphite pyrosequencing on 123 primary breast adenocarcinomas, 16 histologically normal breast tissues adjacent to the tumor, and 24 breast reduction tissues from women without cancer [36] (Fig. 2). Significantly higher methylation percentages were seen in the adenocarcinoma samples compared to those in the healthy breast reduction samples. A receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve for DFNA5 methylation showed a sensitivity of 61.8% for the detection of breast cancer with a specificity of 100% [36]. We concluded that DFNA5 methylation shows strong potential as biomarker for detection of breast cancer. However, the number of samples, the number of CpGs analyzed, the correlation with DFNA5 expression, and the associations with survival parameters were still limited.

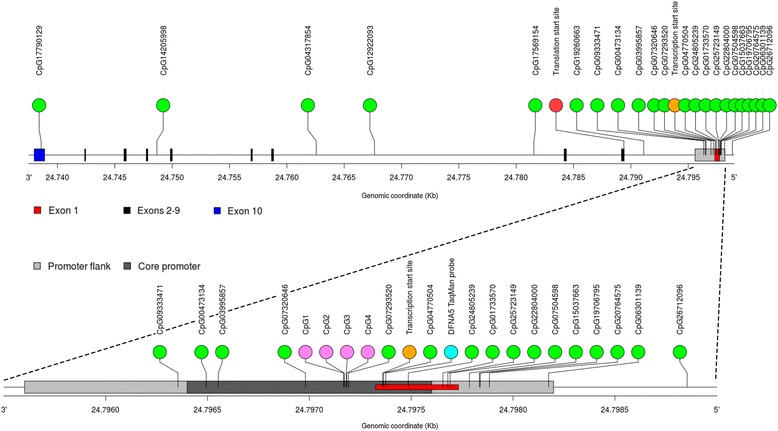

Fig. 2.

The DFNA5 gene with annotation of the 22 CpGs. The 10 exons and the promoter and gene body region of the DFNA5 gene are indicated. These annotations (GRCh37) were made based on the “Regulatory build of the DFNA5 gene” in Ensembl. We considered the core promoter (7:24796400-24797601) together with the flanking regions (7:24795602-24798199) as the putative promoter of DFNA5. On basis of this annotation, six CpGs are located in the DFNA5 gene body, 15 CpGs are located in the DFNA5 promoter, and one CpG is located upstream of the DFNA5 promoter. Using these annotations, CpG06301139 strictly belongs to the promoter of DFNA5. However, in this study, we considered CpG06301139 still part of the upstream promoter region because the methylation pattern is clearly different from the other promoter CpGs and it is located 24 base pairs from the border of the flanking region of the DFNA5 promoter. In addition to the 22 CpGs analyzed in this study (green dots), the four CpGs analyzed in our previous study (pink dots, [36]) and the TaqMan probe (6FAM 5′-ATTCGACCCCGCGAAAAAACGCCGCT-3′-TAMRA) of the study of Kim et al. (blue dot, [35]) are annotated. The transcription start site and the translation start site are indicated with an orange dot and a red dot, respectively

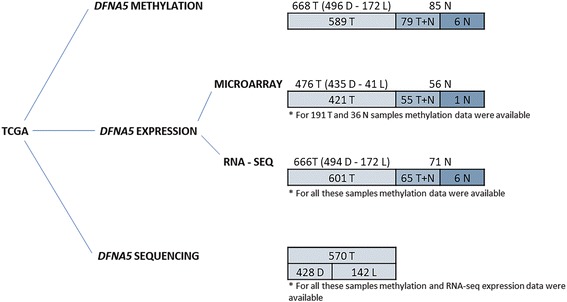

In this study, we aimed to analyze DFNA5 methylation and expression in the largest breast adenocarcinoma patient cohort to date (Fig. 1) using publicly available data from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) in order to further unravel the role of DFNA5 as detection and/or prognostic marker in breast cancer [37].

Fig. 1.

The number of samples for DFNA5 methylation, expression, and sequencing. DFNA5 methylation data were available for 668 unique, primary, untreated, female, well-characterized breast adenocarcinomas (T) (496 ductal (D)–172 lobular (L)) and 85 unique, untreated, female histologically normal breast tissues at a distance of the tumor (N). For 79 of these patients, both a tumor and a normal breast sample were available (paired samples (T+N)). DFNA5 microarray expression data were available for 476 T (435 D–41 L) and 56 N. For 55 of these patients, both a tumor and a normal breast sample were available (T+N). For 191 of these T and 36 of these N, both DFNA5 methylation and expression data were available. DFNA5 RNA-seq expression data were available for 666 T (494 D–172 L) and 71 N. For 65 of these patients, both a tumor and a normal breast sample were available (T+N). For all these samples, also methylation data were available. DFNA5 sequencing data were available for 570 T (428 D–142 L). For all these samples, methylation and RNA-seq expression data were also available

Methods

Study population and tissue samples

All analyses in this manuscript were performed using TCGA data. We selected female, ductal and lobular breast samples that were not neoadjuvantly treated for our analyses. DFNA5 methylation, expression, and sequencing data were downloaded from the TCGA data portal using an in-house developed Python script. The number of samples in each group are shown in Fig. 1. Characteristics of the study populations are shown in Table 1. The mean age of the patients was 57.8 ± 13.0 years (range 26–90 years). A batch number is assigned to a set of related analytes from the same disease that has been distributed to one of the Genome Sequencing Centers.

Table 1.

Clinicopathological features of the TCGA breast adenocarcinomas

| Clinicopathological parameter | Methylation (N = 668) | Expression–microarray (N = 476) | Expression–RNA-seq (N = 666) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number (%) | P value (range) | Number (%) | P value | Number (%) | P value | |

| ER | 2.2 × 10−22–0.049 (20/22 CpGs) | 0.038 | 3.3 × 10− 3 | |||

| ER+ | 490 (73.3) | 362 (76.0) | 488 (73.3) | |||

| ER− | 142 (21.3) | 107 (22.5) | 142 (21.3) | |||

| Unknown | 36 (5.4) | 7 (1.5) | 36 (5.4) | |||

| PR | 9.7 × 10−15–3.0 × 10−3 (15/22 CpGs) | N.S. | N.S. | |||

| PR+ | 428 (64.1) | 310 (65.1) | 427 (64.1) | |||

| PR− | 201 (30.1) | 158 (33.2) | 200 (30.0) | |||

| Unknown | 39 (5.8) | 8 (1.7) | 39 (5.9) | |||

| HER2 | 0.023 (1/22 CpGs) | N.S. | N.S. | |||

| HER2+ | 32 (4.8) | 45 (9.4) | 32 (4.8) | |||

| HER2− | 195 (29.2) | 166 (34.9) | 195 (29.3) | |||

| Unknown | 441 (66.0) | 265 (55.7) | 439 (65.9) | |||

| Tumor stage | 1.9 × 10−4–0.020 (5/22 CpGs) | N.S. | N.S. | |||

| I | 109 (16.3) | 83 (17.5) | 107 (16.1) | |||

| II | 378 (56.6) | 269 (56.5) | 378 (56.8) | |||

| III | 166 (24.9) | 99 (20.8) | 166 (24.9) | |||

| IV | 9 (1.3) | 12 (2.5) | 9 (1.3) | |||

| Unknown | 6 (0.9) | 13 (2.7) | 6 (0.9) | |||

| Histological diagnosis | 1.0 × 10−4–0.038 (10/22 CpGs) | 4.2 × 10−4 | 3.2 × 10−4 | |||

| Ductal | 496 (74.3) | 435 (91.4) | 494 (74.2) | |||

| Lobular | 172 (25.7) | 41 (8.6) | 172 (25.8) | |||

Important clinicopathological parameters, such as ER status, PR status, HER2 status, tumor stage (I–IV), and histological diagnosis are reported for the breast adenocarcinomas. The numbers of adenocarcinomas in each category are reported for the methylation and expression (both microarray and RNA-seq) dataset. The significant p values for the association analysis with either DFNA5 methylation, DFNA5 microarray expression, or DFNA5 RNA-seq expression are reported

N.S. not significant

Methylation data

TCGA methylation data (level 3) were obtained using Infinium HumanMethylation450 BeadChip® microarrays (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). Twenty-two different CpGs throughout the DFNA5 gene were available. The genomic coordinates of the CpGs are based on GRCh37 (Fig. 2). All methylation values are expressed as β values, which is the ratio of the methylated probe intensity to the overall intensity (the sum of methylated and unmethylated probe intensities).

Expression data

TCGA expression data (level 3) were obtained using both Agilent 244K Custom Gene Expression G4502A-07® microarrays (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA) and the IlluminaHiSeq_RNASeqV2 platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). The Agilent microarray contains two probes for DFNA5 (A_23_P82448 [36.3:chr.7:24705001-24705060] and A_23_P82449 [36.3:chr.7:24705092-24705151]), covering the three most abundant DFNA5 transcripts (NM_004403.2, NM_001127454.1, and NM_001127453.1). All microarray expression values are expressed as log2 fc (fold change) relative to the Universal Human Reference RNA (Stratagene). The DFNA5 transcript NM_004403.2 was most abundant in the ribonucleic acid sequencing (RNA-seq) data. The expression of the other transcripts was negligible. RNA-Seq by Expectation Maximization (RSEM) was used as the algorithm for quantifying transcript abundances from RNA-seq data [38]. All RNA-seq expression values are log2 transformed.

Clinicopathological parameters

We selected the following clinicopathological parameters from the TCGA Clinical Patient Data files to perform association analyses: age at diagnosis, estrogen receptor (ER) status determined by immunohistochemistry (IHC) (positive–negative), progesterone receptor (PR) status determined by IHC (positive–negative), human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) status determined by fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) (positive – negative), American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) pathological tumor stage (I–IV), and histological diagnosis (ductal–lobular) (Table 1).

Validation datasets

Three additional methylation datasets were downloaded from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) [39] (GEO accession numbers: GSE52865, GSE69914, and GSE60185). The number of samples used from each dataset are shown in Additional file 1: Table S14.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were carried out using the statistical package R, version 3.1.2 [40]. All p values are two-sided, and p values ≤0.05 were considered statistically significant.

To account for possible batch effects, association tests accounted for the non-independence between individuals from the same batch by fitting a linear mixed model including a random effect for batch number. The significance of the fixed effects was tested via the F-test with a Kenwardroger correction for the number of degrees of freedom. Throughout the regression models, age was accounted for as a covariate, but it was removed from the model if the effect on the outcome was not significant.

Linear mixed models were fit using the lme4 package [41]. Cox proportional hazard models were fit using the survival package [42], to model 5-year overall survival (OS) time based upon either DFNA5 methylation or DFNA5 expression (microarray or RNA-seq), accounting for age. Models with separate baseline hazards for the four tumor stages were fit. Individuals who died without a tumor were considered “lost to follow-up”. Moreover, individuals who died 5 years (1826 days) or more after first diagnosis were censored. For these individuals, follow-up time was set to 1826 days. False discovery rates (FDRs) were calculated using the q-value package [43]. In the quantile-quantile (Q-Q) plots, the distribution of the 22 observed p values is compared to the uniform distribution (U(0,1)), which is expected in the absence of any true association signal. The relative contribution of the methylation of a CpG to 5-year OS time was estimated by comparing the concordance between two Cox proportional hazard models: one baseline model with only tumor stage and age as covariates, and five models to which one of the five CpGs were added as explanatory variable.

Results

DFNA5 methylation and expression in primary breast adenocarcinomas and paired histologically normal breast tissues at a distance of the tumor

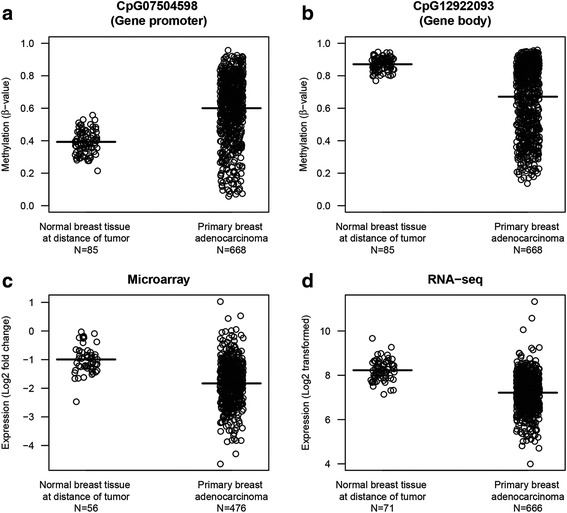

DFNA5 methylation values were plotted for the primary breast adenocarcinomas and normal breast tissues in two CpGs, one in the gene promoter (CpG07504598) and one in the gene body (CpG12922093), as typical example of DFNA5 methylation (Fig. 3a, b). The mean DFNA5 methylation for CpG07504598 was 0.60 (95% CI 0.58–0.62) for the breast adenocarcinomas and 0.39 (95% CI 0.38–0.40) for the normal breast tissues (Fig. 3a). For DFNA5 CpG12922093, the mean methylation was 0.67 (95% CI 0.65–0.69) for the breast adenocarcinomas and 0.87 (95% CI 0.86–0.88) for the normal breast tissues (Fig. 3b). Using a paired samples t test, DFNA5 methylation was investigated in 79 paired breast adenocarcinoma and normal breast samples (Additional file 1: Figure S1A, B). Our analysis showed a significant difference between primary tumor and paired normal breast samples for all 22 CpGs (Additional file 1: Table S1). Overall, breast adenocarcinomas showed higher methylation of CpGs located in the gene promoter compared to normal breast samples. The opposite is true for CpGs located in the gene body (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

DFNA5 methylation and expression in breast adenocarcinomas and normal breast tissues. Panels a and b DFNA5 methylation values are reported for the primary breast adenocarcinomas and normal breast tissues at a distance of the tumor in two CpGs, as a typical example of DFNA5 methylation. Panels c and d DFNA5 expression values are reported for microarray (panel c) and RNA-seq (panel d) experiments for both the primary breast adenocarcinomas and normal breast tissues at a distance of the tumor. Negative expression values for the microarray data indicate a downregulation relative to the Universal Human Reference RNA (Stratagene). The means are indicated with a bold line

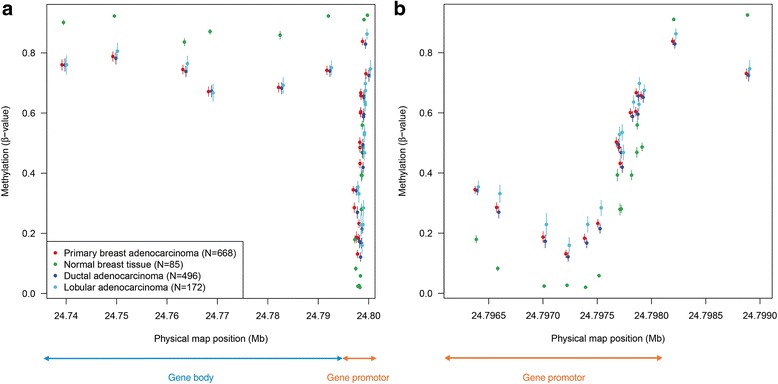

Fig. 4.

Physical map of the 22 CpGs in DFNA5, plotting chromosomal location versus average methylation values. Different subgroups (tumor vs normal; ductal vs lobular) have been plotted. Both the gene body and the putative gene promoter region of DFNA5 are indicated. These figures clearly indicate that normal samples have higher methylation values in the gene body, compared to tumor samples (panel a). The opposite is true for the promoter of DFNA5 (panel b). Moreover, the lobular breast adenocarcinomas showed higher mean DFNA5 methylation values compared to the ductal breast adenocarcinomas in or upstream from the putative gene promoter region. Panel b (gene promoter region) is a magnification of panel a

Moreover, DFNA5 expression was significantly lower in breast adenocarcinomas compared to normal breast samples. The mean DFNA5 microarray expression (log2 fold change (fc)) was − 1.8 (95% CI − 1.9 to − 1.8) for the breast adenocarcinomas and − 0.99 (95% CI − 1.1 to − 0.87) for the normal breast tissues (Fig. 3c). Microarray data showed an observed mean log2 fc difference in DFNA5 expression between normal and tumor sample within the same patient of 0.75 (95% CI 0.53–0.96) (p = 1.8 × 10−09) (Additional file 1: Figure S1C). The mean DFNA5 RNA-seq expression (log2) for the breast adenocarcinomas was 7.2 (95% CI 7.2–7.3) and for the normal breast tissues the mean DFNA5 RNA-seq expression was 8.2 (95% CI 8.1–8.3) (Fig. 3d). The observed mean log2 difference in DFNA5 RNA-seq expression between normal and tumor sample within the same patient was 0.90 (95% CI 0.69–1.12) (p = 2.2 × 10−16) (Additional file 1: Figure S1D).

We also investigated the correlation between DFNA5 microarray and RNA-seq expression data for both 189 breast adenocarcinomas and 35 normal breast samples, for which both microarray and RNA-seq DFNA5 expression data were available. The results are shown in Additional file 1: Figure S2.

Physical mapping of the 22 CpGs in the DFNA5 gene

We plotted the average DFNA5 methylation for all 22 CpGs against their physical map position on chromosome 7 for both primary breast adenocarcinomas and histologically normal breast tissues at a distance of the tumor, and ductal and lobular adenocarcinomas (Fig. 4). A clustering of the methylation values at the different positions could be observed. On the basis of these DFNA5 methylation values, a clear difference exists between the gene body and gene promoter region. The first six CpGs are located in the gene body region, where the mean DFNA5 methylation values of the cancer samples were lower than those of the normal samples. On the other hand, the 14 CpGs which are located in the putative gene promoter region had a higher methylation value in the cancer compared to that in the normal samples. For the last two CpGs this pattern reversed again. We believe that these CpGs are located upstream of the putative gene promoter region (Fig. 2).

Association between DFNA5 methylation and expression

We examined whether DFNA5 methylation is associated with DFNA5 expression, first by calculating the spearman correlation coefficient for DFNA5 expression and methylation for each of the individual 22 CpGs and secondly by fitting a stepwise backward linear regression of the expression data on all 22 CpG methylation values for both breast adenocarcinoma and normal breast samples. All analyses were performed with the microarray and RNA-seq expression data.

First, Spearman correlation coefficients were calculated for samples of which both DFNA5 methylation and expression data were available (Fig. 1). None of the correlations were strong (all < 0.35), which implies that the methylation status of none of the CpGs alone allows an accurate prediction of the DFNA5 expression, neither microarray nor RNA-seq (data not shown).

To predict the expression based upon the methylation of one or more CpGs, multiple linear regression models were fit. For the breast adenocarcinomas, about 20% of the variance in DFNA5 expression is attributable to DFNA5 methylation (microarray: Additional file 1: Table S2; RNA-seq: Additional file 1: Table S3). For the normal breast samples, a regression model was fit for the microarray expression data only (Additional file 1: Table S2). For the RNA-seq expression data, none of the 22 CpGs showed a significant association with DFNA5 expression in the normal samples, and therefore no multiple regression model could be built (data not shown). For the normal samples, these results are somewhat divergent and therefore it is hard to estimate the contribution of DFNA5 methylation on the expression level of these samples. In general, we conclude there is no clear association between DFNA5 methylation and expression.

DFNA5 methylation and expression as detection biomarker for breast cancer

We investigated whether a specific combination of the 22 CpGs analyzed can be used as detection biomarker for breast cancer. Therefore, we analyzed which CpGs discriminate best between primary breast adenocarcinomas (N = 668) and normal breast samples (N = 85). Using stepwise logistic regression, we searched for a model to predict the tumor status of a given tissue using the area under the curve (AUC) as a criterion. Several models reached an AUC in the range of 0.93–0.95. Among these models, we chose a model with high specificity. The model including one CpG in the gene body (CpG12922093) and one CpG in the gene promoter (CpG07504598) as predictors had a tenfold cross-validated AUC of 0.93 (95% CI 0.92–0.95). With the methylation (β) values of these two CpGs, the predicted probability can be calculated:

Sensitivities and specificities at the different cutoff values for the predicted probabilities are shown in Fig. 5. At a predicted probability of 0.87, a sensitivity of 85.3% for detection of breast adenocarcinomas is reached without false positives, with an overall accuracy of 87.0% in our dataset. To further externally validate our findings, we applied our model to three independent methylation datasets to predict the tumor status of a given tissue (Additional file 1: Table S14). We were able to successfully predict the tumor status of the tissues in all three datasets with AUCs comparable to that of the original TCGA dataset (Fig. 5). In general, the model exhibited a high predictive power and good generalizability over different datasets.

Fig. 5.

DFNA5 methylation as biomarker for breast cancer. Panel a One CpG in the gene body (CpG12922093) and one CpG in the gene promoter (CpG07504598) were used as predictors. Sensitivity and specificity at various cutoff values for our dataset are shown. The diagonal line represents the line of no discrimination between breast adenocarcinoma and normal breast samples. The predicted probability (cutoff) of 0.87 is indicated with an asterisk. Panel b Three independent datasets, originating from GEO (GSE52865, GSE69914, and GSE60185), were used to validate our model. Two analyses were performed using GSE69914. First, the analysis was performed on 305 breast cancers and 50 normal breast tissues from healthy women (GSE69914_1). Secondly, 305 breast cancers and 42 normal breast tissues, adjacent to the tumor were used to perform the analysis (GSE69914_2). The AUCs for both are almost identical, and the curves are fully overlapping

Moreover, we investigated whether DFNA5 expression (either microarray or RNA-seq) could be a detection biomarker for breast cancer. For DFNA5 microarray expression, we obtained a ROC with a tenfold cross-validated AUC of 0.82 (95% CI 0.78–0.87) (Additional file 1: Figure S3A). For the DFNA5 RNA-seq expression, a ROC with a tenfold cross-validated AUC of 0.88 (95% CI 0.85–0.91) was reached (Additional file 1: Figure S3B).

DFNA5 methylation and expression in ductal breast adenocarcinomas compared to lobular breast adenocarcinomas

We investigated the difference between ductal and lobular breast adenocarcinomas for both DFNA5 methylation and expression (either microarray or RNA-seq), by fitting a linear mixed model. In 10 out of 22 CpGs, the lobular adenocarcinomas showed significantly higher mean DFNA5 methylation values compared to the ductal adenocarcinomas (Table 1; Fig. 4; Additional file 1: Table S4). All of these 10 CpGs are located in (9/10) or upstream (1/10) from the putative gene promoter region.

Moreover, the lobular adenocarcinomas had a significantly higher DFNA5 expression compared to the ductal adenocarcinomas (Table 1). For the microarray expression values, the mean log2 fc DFNA5 expression for the ductal adenocarcinomas was − 1.86 (95% CI − 1.87 to − 1.86) and for the lobular adenocarcinomas − 1.48 (95% CI − 1.52 to − 1.45). For the RNA-seq expression values, the mean log2 DFNA5 expression for the ductal adenocarcinomas was 7.15 (95% CI 7.08–7.23) and for the lobular adenocarcinomas 7.39 (95% CI 7.29–7.50).

Associations between DFNA5 methylation or expression and clinicopathological parameters

We tested the effect of four clinicopathological parameters (ER status, PR status, HER2 status, or tumor stage (I–IV)) on DFNA5 methylation or expression, both on microarray and RNA-seq data, by fitting a linear mixed model (Table 1). Association analysis showed a significant association between ER status and DFNA5 methylation in 20/22 CpGs (Additional file 1: Table S5) and DFNA5 expression, both with the microarray and the RNA-seq data. The DFNA5 expression was higher in the ER− compared to the ER+ breast adenocarcinomas (Additional file 1: Table S6). In 15/22 CpGs, a significant association between PR status and DFNA5 methylation was observed (Additional file 1: Table S5). Only methylation of CpG04317854 was significantly associated with HER2 amplification (Additional file 1: Table S5). Furthermore, tumor stage was significantly associated with DFNA5 methylation in 5 out of 22 CpGs (Additional file 1: Table S7). There were only nine patients with a stage IV breast adenocarcinoma; these were not included in the analysis. None of these clinicopathological parameters (PR, HER2, and tumor stage) showed a significant association with DFNA5 expression, with neither microarray nor with RNA-seq data.

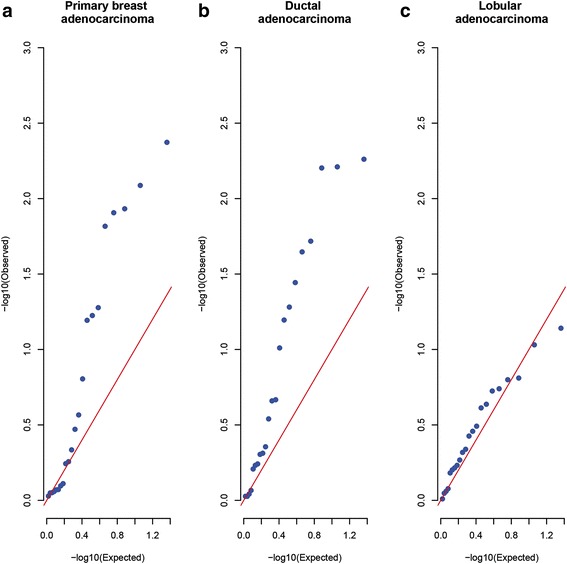

Associations between DFNA5 methylation or expression and 5-year overall survival

Overall survival (OS) was investigated by fitting Cox proportional hazard models over a 5-year period to determine the prognostic value of DFNA5 methylation or expression, using either microarray or RNA-seq data, in breast adenocarcinoma patients. Follow-up data were not available for all patients (Additional file 1: Table S8). Cox proportional hazard models were fit to model the survival time based upon either DFNA5 methylation or DFNA5 expression (microarray or RNA-seq). Models were fit on all breast adenocarcinoma patients, only the ductal, or only the lobular adenocarcinoma patients.

Survival analysis on all breast adenocarcinoma patients showed a significant association between 5-year OS time and DFNA5 methylation in 5/22 CpGs (Table 2). Since a Bonferroni correction for multiple testing would not be appropriate due to the strong correlation in methylation between the CpG islands (data not shown), we tested for an enrichment in low p values using Q-Q plots (Fig. 6) and performed a false discovery rate (FDR) analysis (Additional file 1: Table S9). The Q-Q plot clearly indicates an increase in significant p values compared to the expected null distribution. Therefore, the FDR analysis shows that it is very likely that some of the significant p values represent genuine association signals. This suggests that the methylation of the CpGs as a whole contains information on 5-year OS time and strengthens the potential of DFNA5 methylation as a prognostic marker. A very similar observation was made when studying the ductal adenocarcinoma patients only, with one additional significant CpG, located upstream from the putative gene promoter of DFNA5 (Table 2). In the lobular adenocarcinoma patients, the enrichment of low p values was not observed, but it cannot be excluded that this is due to the lower number of observations in this latter subset (Table 2; Fig. 6; Additional file 1: Table S8).

Table 2.

The effect of methylation of every of the 22 CpGs on 5-year OS time

| CpG | Genomic coordinate (GRCh37) | All breast adenocarcinomas | Ductal adenocarcinomas | Lobular adenocarcinomas | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regression coefficient | S.E. | P value | Regression coefficient | S.E. | P value | Regression coefficient | S.E. | P value | ||

| CpG17790129 | 24738572 | 5.1 | 1.9 | 8.2 × 10−3 * | 6.0 | 2.5 | 0.019 * | 2.3 | 3.8 | 0.54 |

| CpG14205998 | 24748668 | 5.1 | 2.1 | 0.015 * | 4.9 | 2.1 | 0.023 * | 13.9 | 11.9 | 0.24 |

| CpG04317854 | 24762562 | 1.8 | 1.3 | 0.16 | 2.6 | 1.4 | 0.064 | − 2.6 | 3.5 | 0.46 |

| CpG12922093 | 24767644 | 3.1 | 1.2 | 0.012 * | 3.8 | 1.4 | 6.2 × 10−3 * | − 1.9 | 4.2 | 0.66 |

| CpG17569154 | 24781545 | 3.0 | 1.2 | 0.012 * | 3.6 | 1.3 | 6.3 × 10−3 * | − 2.3 | 4.4 | 0.61 |

| CpG19260663 | 24791121 | 5.3 | 1.9 | 4.2 × 10−3 * | 5.7 | 2.0 | 5.5 × 10−3 * | 7.5 | 6.3 | 0.23 |

| CpG09333471 | 24796355 | 2.5 | 1.3 | 0.059 | 1.7 | 1.4 | 0.22 | 11.4 | 6.8 | 0.093 |

| CpG00473134 | 24796494 | 0.81 | 1.4 | 0.57 | 0.78 | 1.6 | 0.62 | 4.3 | 4.8 | 0.37 |

| CpG03995857 | 24796553 | − 0.19 | 1.0 | 0.85 | − 0.75 | 1.1 | 0.49 | 7.4 | 5.2 | 0.16 |

| CpG07320646 | 24796981 | − 0.49 | 0.84 | 0.55 | − 1.3 | 1.0 | 0.22 | 7.0 | 5.3 | 0.19 |

| CpG07293520 | 24797192 | − 0.17 | 1.2 | 0.89 | − 1.7 | 1.6 | 0.29 | 9.5 | 5.3 | 0.072 |

| CpG04770504 | 24797363 | − 1.3 | 1.2 | 0.27 | − 2.4 | 1.4 | 0.098 | 11.7 | 8.8 | 0.18 |

| CpG24805239 | 24797486 | − 0.19 | 1.2 | 0.87 | − 0.91 | 1.3 | 0.49 | 6.4 | 4.5 | 0.16 |

| CpG01733570 | 24797656 | 0.97 | 1.0 | 0.34 | 0.77 | 1.0 | 0.44 | 3.9 | 3.9 | 0.32 |

| CpG25723149 | 24797680 | 0.14 | 1.0 | 0.89 | 0.18 | 1.0 | 0.86 | 2.2 | 4.1 | 0.59 |

| CpG22804000 | 24797691 | − 0.092 | 1.1 | 0.93 | 0.087 | 1.1 | 0.94 | 0.51 | 3.9 | 0.90 |

| CpG07504598 | 24797786 | − 0.31 | 1.1 | 0.77 | − 0.13 | 1.1 | 0.91 | 0.87 | 4.2 | 0.83 |

| CpG15037663 | 24797835 | − 0.21 | 1.1 | 0.85 | − 0.086 | 1.1 | 0.94 | 3.4 | 4.8 | 0.48 |

| CpG19706795 | 24797839 | 0.29 | 1.2 | 0.80 | 0.67 | 1.2 | 0.58 | 0.13 | 4.3 | 0.98 |

| CpG20764575 | 24797884 | − 0.77 | 1.1 | 0.46 | − 0.60 | 1.1 | 0.57 | 0.84 | 5.0 | 0.87 |

| CpG06301139 | 24798175 | 4.2 | 2.3 | 0.064 | 5.0 | 2.6 | 0.052 | 2.9 | 5.9 | 0.63 |

| CpG26712096 | 24798855 | 2.4 | 1.2 | 0.053 | 2.7 | 1.3 | 0.036 * | 3.9 | 4.2 | 0.35 |

For each of the 22 CpGs, the effect size (= regression coefficient) with standard error (S.E.) and the p value (likelihood ratio test) are reported for the effect on 5-year OS time in all breast adenocarcinoma patients, only the ductal, or only the lobular carcinoma patients. CpG17790129–CpG19260663 are located in the gene body, CpG09333471–CpG20764575 are located in the putative gene promoter, and the last two CpGs, CpG06301139 and CpG26712096, are located upstream from the putative gene promoter

*Significant p values

Fig. 6.

Q-Q plots of the 22 p values for the 5-year OS analysis. Under the null hypothesis of no association, p values follow a uniform distribution between 0 and 1. The diagonal line shows this expected distribution of p values. The points on the plot show the p values observed in the survival analysis. For all breast adenocarcinomas together (panel a) and only the ductal adenocarcinomas (panel b), the presence of many points above the diagonal line indicates a substantial enrichment in low p values. The p values in the lobular subset (panel c) are closely following the expected distribution of the p values, indicating no enrichment in low p values there

Remarkably, the five CpGs with methylation values significantly associated with 5-year OS time are all located in the gene body region of DFNA5. Moreover, the positive regression coefficients indicate that higher methylation values are associated with a decrease in survival time (Table 2). The contribution of each of the five significant CpGs to 5-year OS time was investigated in a Cox proportional hazard frame work. Due to the limited number of patients in stages I and IV, this contribution could only be studied for stages II and III. For stage II, adding DFNA5 methylation to the survival model lead to an increase in concordance of 7.0–11.1%, while for stage III, this increase in concordance was 4.9–11.0%, depending on which of the five CpGs was used (Additional file 1: Table S10). We conclude that the increase in concordance of the five significant CpGs to 5-year OS time was very similar. This is not surprising, since the methylation of the five significant CpGs (all located within the gene body) are strongly correlated (data not shown). Similar results are obtained for the ductal adenocarcinoma patients only (Additional file 1: Table S11).

Survival analysis showed no significant association between DFNA5 expression and 5-year OS time, neither microarray nor RNA-seq, for all breast adenocarcinoma patients or ductal and lobular adenocarcinoma patients only (Additional file 1: Table S8).

Discussion

In this study, we evaluated the potential use of DFNA5 methylation and expression as detection and prognostic biomarker in breast cancer, on basis of data obtained from TCGA. DFNA5 methylation was significantly different between primary breast adenocarcinomas and normal breast samples for all 22 CpGs analyzed. Overall, breast adenocarcinomas showed a higher DFNA5 methylation in the putative gene promoter compared to normal breast samples, whereas in the gene body and upstream of the putative gene promoter, the opposite is true. We can conclude that DFNA5 follows the classical cancer methylation paradigm of hypermethylation of the CpG island promoter and global genomic hypomethylation [8]. These results are in line with those obtained in our previous study [36] and the study of Kim et al. [35], where only DFNA5 promoter methylation was analyzed and different CpGs were investigated using pyrosequencing and TaqMan-methylation-specific PCR (TaqMan-MSP), respectively (Additional file 1: Table S12). DFNA5 expression was significantly lower in breast adenocarcinomas compared to normal breast samples, for both microarray and RNA-seq data. These results were in line with those obtained by Kim et al. [35] and Stoll et al. [27].

Despite the clear difference between primary breast adenocarcinomas and normal breast tissues for both DFNA5 methylation and expression, no clear association between DFNA5 methylation and expression could be found. In literature, it has already been demonstrated that the relationship between epigenetics and gene expression can be more ambiguous than previously thought [44]. Moreover, Stoll et al. also concluded that DNA hypermethylation did not affect the expression of DFNA5 [27]. This is in contrast to the study of Akino et al. in gastric cancer [31]. However, Akino et al. analyzed the methylation of different CpGs in DFNA5, which are not present on the Infinium HumanMethylation450 BeadChip® microarrays that TCGA used. Perhaps it is possible that methylation of specific CpGs in DFNA5 may be necessary to influence its expression. However, different reasons exist why no association could be found. One reason could be that current data do not allow to discriminate between DFNA5 DNA hydroxymethylation from methylation [45, 46]. Another confounding factor could be the expression of microRNAs (miRNAs) that regulate DFNA5 expression. Mir_3p and mir26b_5p are two miRNAs that may interfere with DFNA5 expression [47, 48]. Expression data of both miRNAs were available in TCGA. However, no association between DFNA5 expression and mir_3p or mir26b_5p expression could be found (data not shown). Another possibility could be the existence of deleterious somatic DFNA5 variants occurring in the breast adenocarcinomas. Analysis of TCGA whole exome sequencing data revealed only five (of a total of 570) patients with a somatic DFNA5 variation (3 missense and 2 silent variants) (Additional file 1: Table S13). This is in line with the observation that mutations in pro-necrotic genes, including DFNA5, are infrequent and that reduction in copy numbers are observed in less than 2% of breast cancers [27]. Moreover, other (epigenetic) factors, such as histone modifications, could possibly also have an impact on (DFNA5) gene expression. Another possibility is chemical modification of the RNA, which can also regulate the expression of genes, the so called epitranscriptome [49–51]. It is clear that gene expression is a complex process and the interplay between many different genetic, epigenetic, and epitranscriptomic factors determines the expression level of a gene [11, 52–55]. Lastly, tumor heterogeneity may also be a reason why no association between DFNA5 methylation and expression could be found. The tissue slices used for methylation and expression analysis are not identical, as they originate from a different part of the tumor. Moreover, as the percentage of the tumor cells is never 100% (TCGA uses samples with at least 60% tumor cells), the ratio of tumor versus normal cells can differ between those slices.

A major result of this study is the identification of a combination of two CpGs, one CpG in the promoter (CpG07504598) and one CpG in the gene body (CpG12922093) of DFNA5, which was able to discriminate between primary breast adenocarcinomas and normal breast samples. The model with those two CpGs as predictors had a tenfold cross-validated AUC of 0.93. Moreover, our model was externally validated in three independent datasets from the GEO database. The AUC values for these datasets were very similar to that of the original dataset, which confirms the validity of our model and its generalizability over external cohorts. All together, these results suggest a strong potential for DFNA5 methylation as biomarker for the detection of breast cancer.

We found that DFNA5 methylation was significantly higher in 10 out of 22 CpGs analyzed in lobular compared to ductal adenocarcinomas. Remarkably, those 10 CpGs are all located in or upstream of the putative gene promoter region and not in the gene body of DFNA5. Despite the higher DFNA5 promoter methylation in the lobular adenocarcinomas, the DFNA5 expression was also significantly higher in the lobular compared to the ductal adenocarcinomas.

We analyzed the association of DFNA5 methylation and expression with four clinicopathological parameters. In line with the previous study of Thompson and Weigel [56], an inverse correlation between ER status and DFNA5 expression could be found. Moreover, DFNA5 methylation was also significantly associated with ER status in 20 out of 22 CpGs. DFNA5 methylation in the putative gene promoter was always higher in the ER+ breast adenocarcinomas compared to the ER− breast adenocarcinomas and in the gene body region the opposite was true. This is in contrast to the study of Kim et al. [35] and our previous study [36] (Additional file 1: Table S12). However, in these studies, they analyzed a few CpGs which are not present on the Infinium HumanMethylation450 BeadChip® microarrays that TCGA used. Thompson and Weigel concluded that the pattern of DFNA5 (ICERE-1) expression suggests that DFNA5 may be involved in tumor biology specific to hormonally unresponsive breast cancers, and therefore, DFNA5 expression may be a useful marker for this type of breast cancer [56].

Finally, despite the limited number of events, we were able to find a significant effect of methylation in the DFNA5 gene body on 5-year OS time, for all breast adenocarcinoma patients together as well as for the ductal adenocarcinoma patients only (Additional file 1: Table S12). Remarkably, the five CpGs with a significant p value were all located in the gene body region of DFNA5 and their positive regression coefficients indicate that higher methylation of these CpGs was associated with a decrease in survival time. The regulatory role of gene body methylation is still unclear, but could prevent spurious transcription initiation, may promote (alternative) splicing, or represent a higher order chromatin topologically associating domain to guide regulatory elements to the DFNA5 promoter [52, 57–60]. Among those five CpGs located in the gene body, the most significant association with 5-year OS time was found for CpG19260663 in all breast adenocarcinoma patients together as well as in the ductal adenocarcinoma patients only. From the concordance tables, we can conclude that, in addition to the age of the patient, DFNA5 gene body methylation has an added value of around 9% to predict 5-year OS time. The enrichment in low p values, shown in Q-Q plots and the FDR calculations, suggests that the methylation of the CpGs as a whole contain information on the survival time and strengthens the potential of DFNA5 gene body methylation as a prognostic marker. Large prospective studies, with a homogeneous breast adenocarcinoma population (in terms of treatment), are needed to confirm the prognostic role of DFNA5 gene body methylation in breast adenocarcinoma. The effect of DFNA5 expression on 5-year OS time was not significant, corroborating previous findings [27].

Conclusions

We conclude that DFNA5 methylation shows strong potential as detection and prognostic biomarker for breast cancer. In order to evaluate the potential of DFNA5 methylation as early biomarker, the analysis of in situ carcinoma samples could be a good strategy [15–21]. A next step to further investigate and develop DFNA5 methylation as biomarker for breast cancer could be the analysis of DFNA5 methylation in liquid biopsies. Several studies have provided proof of principle for the detection of promoter hypermethylation of tumor-derived DNA in liquid biopsies [61–66]. Using liquid biopsies, DFNA5 methylation has the potential to be a suitable low invasive detection and prognostic biomarker for breast cancer.

Additional files

Table S1. Mean difference in DFNA5 methylation between the paired tumor and normal breast sample in 79 patients for every of the 22 CpGs. Figure S1. DFNA5 methylation (in the gene promoter and in the gene body) and expression (microarray and RNA-seq) in paired tumor and normal breast samples. Figure S2. Correlation between microarray and RNA-seq expression data. Table S2. Stepwise linear regression models of DFNA5 microarray expression on DFNA5 methylation for both breast adenocarcinoma and normal breast samples. Table S3. Stepwise linear regression model of DFNA5 RNA-seq expression on DFNA5 methylation for the breast adenocarcinomas. Figure S3. DFNA5 expression as biomarker for breast adenocarcinomas. Table S4. Mean DFNA5 methylation for the ductal and the lobular breast adenocarcinomas for every of the 22 CpGs. Table S5. Mean DFNA5 methylation for ER status, PR status, and HER2 status for every of the 22 CpGs. Table S6. Mean DFNA5 expression for ER+ and ER− breast adenocarcinomas. Table S7. Mean DFNA5 methylation for the four tumor stages for every of the 22 CpGs. Table S8.Vital status of the breast adenocarcinoma patients after 5 years of follow-up. Table S9. False discovery rate (FDR) for 5-year OS analysis on all breast adenocarcinomas and ductal breast adenocarcinomas. Table S10. Concordance for 5-year OS analysis on all breast adenocarcinomas. Table S11. Concordance for 5-year OS analysis on ductal breast adenocarcinomas. Table S12. Similarities and differences between three studies investigating DFNA5 methylation in breast cancer. Table S13. Single nucleotide variants in the DFNA5 gene with corresponding changes in the amino acid sequence of DFNA5. Table S14. Three methylation datasets from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) for validation of our model to predict the tumor status. (DOCX 629 kb)

Acknowledgements

The results shown in this manuscript are based upon the data generated by the TCGA Research Network: http://cancergenome.nih.gov/.

Funding

Lieselot Croes has a Ph.D. fellowship of the Research Foundation–Flanders (FWO; 11Y9815N).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available in the following open access repositories:

TCGA, https://cancergenome.nih.gov/

GEO, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/ (GEO accession numbers: GSE52865, GSE69914 and GSE60185)

miRTarBase, http://mirtarbase.mbc.nctu.edu.tw/index.php.

Abbreviations

- AJCC

American Joint Committee on Cancer

- AUC

Area under the curve

- DFNA5

Deafness, autosomal dominant 5

- ER

Estrogen receptor

- fc

Fold change

- FDR

False discovery rate

- FISH

Fluorescent in situ hybridization

- GEO

Gene Expression Omnibus

- GSDME

Gasdermin E

- HER2

Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2

- ICERE

Inversely correlated with estrogen receptor expression

- IHC

Immunohistochemistry

- miRNA

MicroRNA

- N.S.

Not significant

- OS

Overall survival

- PR

Progesterone receptor

- Q-Q

Quantile-quantile

- RNA-seq

Ribonucleic acid sequencing

- ROC

Receiver operating characteristic

- RSEM

RNA-Seq by Expectation Maximization

- S.E.

Standard error

- TaqMan-MSP

TaqMan–methylation-specific polymerase chain reaction

- TCGA

The Cancer Genome Atlas

Authors’ contributions

LC and EF analyzed the TCGA data. LC, KoDB, and GVC designed and supervised the study and wrote the manuscript. MB and EF performed the bioinformatic analyses. JI performed the validation experiment on GEO data. All authors read and contributed, with their critical revision, to the final version of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval has been obtained by The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s13148-018-0479-y) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Contributor Information

Lieselot Croes, Email: lieselot.croes@uantwerpen.be.

Matthias Beyens, Email: matthias.beyens@uantwerpen.be.

Erik Fransen, Email: erik.fransen@uantwerpen.be.

Joe Ibrahim, Email: joe.ibrahim@uantwerpen.be.

Wim Vanden Berghe, Email: wim.vandenberghe@uantwerpen.be.

Arvid Suls, Email: arvid.suls@uantwerpen.be.

Marc Peeters, Email: Marc.Peeters@uza.be.

Patrick Pauwels, Email: Patrick.Pauwels@uza.be.

Guy Van Camp, Phone: +3232759762, Email: guy.vancamp@uantwerpen.be.

Ken Op de Beeck, Email: ken.opdebeeck@uantwerpen.be.

References

- 1.Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer. 2015;136:E359. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ciriello G, Pastore A, Zhang H, McLellan M, Yau C, Kandoth C, et al. Comprehensive molecular portraits of invasive lobular breast cancer. Cell. 2015;163:506. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.09.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rakha EA, Reis-Filho JS, Baehner F, Dabbs DJ, Decker T, Eusebi V, et al. Breast cancer prognostic classification in the molecular era: the role of histological grade. Breast Cancer Res. 2010;12(4):207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Li CI, Anderson BO, Daling JR, Moe RE. Trends in incidence rates of invasive lobular and ductal breast carcinoma. JAMA. 2003;289:1421. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.11.1421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li CI, Daling JR. Changes in breast cancer incidence rates in the United States by histologic subtype and race/ethnicity, 1995 to 2004. Cancer Epidemiol Prev Biomarkers. 2007;16:2773. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization (WHO). Breast cancer: prevention and control. http://www.who.int/cancer/detection/breastcancer/en/. Accessed 2 Oct 2017.

- 7.Gøtzsche PC, Jørgensen KJ. Screening for breast cancer with mammography. 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Esteller M. Epigenetics in cancer. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1148. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra072067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ohlsson R, Henikoff S. The epigenetic progenitor origin of human cancer. Nat Rev Genet. 2006;7:21. doi: 10.1038/nrg1748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Feinberg AP, Tycko B. The history of cancer epigenetics. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:143–153. doi: 10.1038/nrc1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jones PA, Baylin SB. The epigenomics of cancer. Cell. 2007;128:683–692. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Berdasco M, Esteller M. Aberrant epigenetic landscape in cancer: how cellular identity goes awry. Dev Cell. 2010;19:698–711. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Esteller M. Cancer epigenomics: DNA methylomes and histone-modification maps. Nat Rev Genet. 2007;8:286. doi: 10.1038/nrg2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Esteller M. Epigenetic gene silencing in cancer: the DNA hypermethylome. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16(Spec 1):R50–R59. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoque MO, Prencipe M, Poeta ML, Barbano R. Changes in CpG islands promoter methylation patterns during ductal breast carcinoma progression. Cancer Epidemiology and Prevention Biomarkers. 2009;18:2694. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Balch C, Montgomery JS, Paik H-I, Kim S, Kim S, Huang TH-M, et al. New anti-cancer strategies: epigenetic therapies and biomarkers. Front Biosci. 2005;10:1897–1931. doi: 10.2741/1668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Umbricht CB, Evron E, Gabrielson E, Ferguson A, Marks J, Sukumar S. Hypermethylation of 14-3-3 sigma (stratifin) is an early event in breast cancer. Oncogene. 2001;20:3348–3353. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johnson KC, Koestler DC, Fleischer T, Chen P, Jenson EG, Marotti JD, et al. DNA methylation in ductal carcinoma in situ related with future development of invasive breast cancer. Clin Epigenetics. 2015;7:75. doi: 10.1186/s13148-015-0094-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fleischer T, Frigessi A, Johnson KC, Edvardsen H, Touleimat N, Klajic J, et al. Genome-wide DNA methylation profiles in progression to in situ and invasive carcinoma of the breast with impact on gene transcription and prognosis. Genome Biol. 2014;15:435. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0435-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Feinberg AP, Ohlsson R. The epigenetic progenitor origin of human cancer. Nat Rev Genet. 2006;7(1):21–33. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Sharma S, Kelly TK, Jones PA. Epigenetics in cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2010;31(1):27–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Van Laer L, Huizing EH, Verstreken M, van Zuijlen D, Wauters JG, Bossuyt PJ, et al. Nonsyndromic hearing impairment is associated with a mutation in DFNA5. Nat Genet. 1998;20:194–197. doi: 10.1038/2503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Op de Beeck K, Van Camp G, Thys S, Cools N, Callebaut I, Vrijens K, et al. The DFNA5 gene, responsible for hearing loss and involved in cancer, encodes a novel apoptosis-inducing protein. Eur J Hum Genet. 2011;19:965–973. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2011.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Van Rossom S, de Beeck KO, Franssens V, Swinnen E, Schepers A, Ghillebert R, et al. The splicing mutant of the human tumor suppressor protein DFNA5 induces programmed cell death when expressed in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Front Oncol. 2012;2:77. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2012.00077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Van Rossom S, de Beeck KO, Hristovska V, Winderickx J, Van Camp G. The deafness gene DFNA5 induces programmed cell death through mitochondria and MAPK-related pathways. Front Cell Neurosci. 2015;9:231. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2015.00231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rogers C, Fernandes-Alnemri T, Mayes L, Alnemri D, Cingolani G, Alnemri ES. Cleavage of DFNA5 by caspase-3 during apoptosis mediates progression to secondary necrotic/pyroptotic cell death. Nat Commun. 2017;8:14128. doi: 10.1038/ncomms14128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stoll G, Ma Y, Yang H, Kepp O, Zitvogel L, Kroemer G. Pro-necrotic molecules impact local immunosurveillance in human breast cancer. Oncoimmunology. 2017;6:e1299302. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2017.1299302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang Y, Gao W, Shi X, Ding J, Liu W, He H, et al. Chemotherapy drugs induce pyroptosis through caspase-3 cleavage of a gasdermin. Nature. 2017;547:99–103. doi: 10.1038/nature22393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Strzyz P. Cell death: pulling the apoptotic trigger for necrosis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2017;18:72. doi: 10.1038/nrm.2017.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Galluzzi L, Kroemer G. Secondary necrosis: accidental no more. Trends Cancer. 2017;3:1–2. doi: 10.1016/j.trecan.2016.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Akino K, Toyota M, Suzuki H, Imai T, Maruyama R, Kusano M, et al. Identification of DFNA5 as a target of epigenetic inactivation in gastric cancer. Cancer Sci. 2006;98:88–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2006.00351.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim MS, Chang X, Yamashita K, Nagpal JK, Baek JH, Wu G, et al. Aberrant promoter methylation and tumor suppressive activity of the DFNA5 gene in colorectal carcinoma. Oncogene. 2008;27:3624–3634. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1211021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fujikane T, Nishikawa N, Toyota M, Suzuki H, Nojima M, Maruyama R, et al. Genomic screening for genes upregulated by demethylation revealed novel targets of epigenetic silencing in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009;122:699–710. doi: 10.1007/s10549-009-0600-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yokomizo K, Harada Y, Kijima K, Shinmura K, Sakata M, Sakuraba K, et al. Methylation of the DFNA5 gene is frequently detected in colorectal cancer. Anticancer Res. International Institute of Anticancer Research. 2012;32:1319–1322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim MS, Lebron C, Nagpal JK, Chae YK, Chang X, Huang Y, et al. Methylation of the DFNA5 increases risk of lymph node metastasis in human breast cancer. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;370:38–43. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.03.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Croes L, de Beeck KO, Pauwels P, Berghe WV, Peeters M, Fransen E, et al. DFNA5 promoter methylation a marker for breast tumorigenesis. Oncotarget. 2017;8:31948–31958. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.16654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) Research Network. https://cancergenome.nih.gov/. Accessed 18 Mar 2016.

- 38.Li B, Dewey CN. RSEM: accurate transcript quantification from RNA-Seq data with or without a reference genome. BMC Bioinform. 2011;12:323. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/. Accessed 16 Oct 2017.

- 40.Team RC. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bates D, Maechler M, Bolker BM, Walker SC. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. Springer texts in Statistics 2015;67:1–48.

- 42.Therneau T. A Package for Survival Analysis in S. version 2.38; 2015. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=survival.

- 43.Dabney A, Storey JD, Warnes GR. qvalue: Q-value estimation for false discovery rate control. R package version 1.38; 2011.

- 44.Yamada L, Chong S. Epigenetic studies in developmental origins of health and disease: pitfalls and key considerations for study design and interpretation. J Dev Orig Health Dis. 2017;8:30. doi: 10.1017/S2040174416000507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ehrlich M, Ehrlich KC. DNA cytosine methylation and hydroxymethylation at the borders. Epigenomics. 2014;6:563–566. doi: 10.2217/epi.14.48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ponnaluri VKC, Ehrlich KC, Zhang G, Lacey M, Johnston D, Pradhan S, et al. Association of 5-hydroxymethylation and 5-methylation of DNA cytosine with tissue-specific gene expression. Epigenetics. 2016;12:123–138. doi: 10.1080/15592294.2016.1265713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chou C-H, Chang N-W, Shrestha S, Hsu S-D, Lin Y-L, Lee W-H, et al. miRTarBase 2016: updates to the experimentally validated miRNA-target interactions database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;44:D239–D247. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.miRTarBase: the experimentally validated microRNA-target interactions database. http://mirtarbase.mbc.nctu.edu.tw/index.php. Accessed 7 Nov 2016.

- 49.Meyer KD, Jaffrey SR. The dynamic epitranscriptome: N6-methyladenosine and gene expression control. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2014;15:313. doi: 10.1038/nrm3785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fu Y, Dominissini D, Rechavi G. Gene expression regulation mediated through reversible m6A RNA methylation. Nat Rev Genet. 2014;15:293. doi: 10.1038/nrg3724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Song J, Yi C. Chemical modifications to RNA: a new layer of gene expression regulation. ACS Chem Biol. 2017;12:316. doi: 10.1021/acschembio.6b00960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jones PA. Functions of DNA methylation: islands, start sites, gene bodies and beyond. Nat Rev Genet. 2012;13:484. doi: 10.1038/nrg3230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yamada L, Chong S. Epigenetic studies in developmental origins of health and disease: pitfalls and key considerations for study design and interpretation. J Dev Orig Health Dis. 2016;8:30–43. doi: 10.1017/S2040174416000507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lin I-H, Chen D-T, Chang Y-F, Lee Y-L, Su C-H, Cheng C, et al. Hierarchical clustering of breast cancer methylomes revealed differentially methylated and expressed breast cancer genes. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0118453. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0118453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gibney ER, Nolan CM. Epigenetics and gene expression. Heredity (Edinb) 2010;105:4–13. doi: 10.1038/hdy.2010.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Thompson DA, Weigel RJ. Characterization of a gene that is inversely correlated with estrogen receptor expression (ICERE-1) in breast carcinomas. Eur J Biochem. 1998;252:169–177. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1998.2520169.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lupiáñez DG, Spielmann M, Mundlos S. Breaking TADs: how alterations of chromatin domains result in disease. Trends Genet. 2016;32:225–237. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2016.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Maor GL, Yearim A, Ast G. The alternative role of DNA methylation in splicing regulation. Trends Genet. 2015;31:274–280. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2015.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yang X, Han H, De Carvalho DD, Lay FD, Jones PA. Gene body methylation can alter gene expression and is a therapeutic target in cancer. Cancer cell. 2014;26(4):577–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 60.Neri F, Rapelli S, Krepelova A, Incarnato D, Parlato C, Intragenic DNA. Methylation prevents spurious transcription initiation. Nature. 2017;543(7643):72–77. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 61.Hoque MO, Feng Q, Toure P, Dem A, Critchlow CW, Hawes SE, et al. Detection of aberrant methylation of four genes in plasma DNA for the detection of breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;24:4262–4269. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.3516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Shan M, Yin H, Li J, Li X, Wang D, Su Y, et al. Detection of aberrant methylation of a six-gene panel in serum DNA for diagnosis of breast cancer. Oncotarget. 2016;7:18485–18494. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.7608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wittenberger T, Sleigh S, Reisel D, Zikan M, Wahl B, Alunni-Fabbroni M, et al. DNA methylation markers for early detection of women's cancer: promise and challenges. Epigenomics. 2014;6:311–327. doi: 10.2217/epi.14.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Garrigou S, Perkins G, Garlan F, Normand C, Didelot A, Le Corre D, et al. A study of hypermethylated circulating tumor DNA as a universal colorectal cancer biomarker. Clin Chem. 2016;62:1129–1139. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2015.253609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Roperch J-P, Incitti R, Forbin S, Bard F, Mansour H, Mesli F, et al. Aberrant methylation of NPY, PENK, and WIF1 as a promising marker for blood-based diagnosis of colorectal cancer. BMC Cancer. 2013;13:566. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-13-566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Warton K, Mahon KL, Samimi G. Methylated circulating tumor DNA in blood: power in cancer prognosis and response. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2016;23:R157–R171. doi: 10.1530/ERC-15-0369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Mean difference in DFNA5 methylation between the paired tumor and normal breast sample in 79 patients for every of the 22 CpGs. Figure S1. DFNA5 methylation (in the gene promoter and in the gene body) and expression (microarray and RNA-seq) in paired tumor and normal breast samples. Figure S2. Correlation between microarray and RNA-seq expression data. Table S2. Stepwise linear regression models of DFNA5 microarray expression on DFNA5 methylation for both breast adenocarcinoma and normal breast samples. Table S3. Stepwise linear regression model of DFNA5 RNA-seq expression on DFNA5 methylation for the breast adenocarcinomas. Figure S3. DFNA5 expression as biomarker for breast adenocarcinomas. Table S4. Mean DFNA5 methylation for the ductal and the lobular breast adenocarcinomas for every of the 22 CpGs. Table S5. Mean DFNA5 methylation for ER status, PR status, and HER2 status for every of the 22 CpGs. Table S6. Mean DFNA5 expression for ER+ and ER− breast adenocarcinomas. Table S7. Mean DFNA5 methylation for the four tumor stages for every of the 22 CpGs. Table S8.Vital status of the breast adenocarcinoma patients after 5 years of follow-up. Table S9. False discovery rate (FDR) for 5-year OS analysis on all breast adenocarcinomas and ductal breast adenocarcinomas. Table S10. Concordance for 5-year OS analysis on all breast adenocarcinomas. Table S11. Concordance for 5-year OS analysis on ductal breast adenocarcinomas. Table S12. Similarities and differences between three studies investigating DFNA5 methylation in breast cancer. Table S13. Single nucleotide variants in the DFNA5 gene with corresponding changes in the amino acid sequence of DFNA5. Table S14. Three methylation datasets from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) for validation of our model to predict the tumor status. (DOCX 629 kb)

Data Availability Statement

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available in the following open access repositories:

TCGA, https://cancergenome.nih.gov/

GEO, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/ (GEO accession numbers: GSE52865, GSE69914 and GSE60185)

miRTarBase, http://mirtarbase.mbc.nctu.edu.tw/index.php.