Abstract

Background

Sexual assault is a global concern with PTSD one of the common sequelae. Early intervention can help prevent PTSD, making identification of those at high risk for the disorder a priority. Lack of representative sampling of both sexual assault survivors and sexual assaults in prior studies might have reduced the ability to develop accurate prediction models for early identification of high-risk sexual assault survivors.

Methods

Data come from 12 face-to-face, cross-sectional surveys of community-dwelling adults conducted in 11 countries. Analysis was based on the data from the 411 women from these surveys for whom sexual assault was the randomly selected lifetime traumatic event (TE). Seven classes of predictors were assessed: socio-demographics, characteristics of the assault, the respondent’s retrospective perception that she could have prevented the assault, other prior lifetime TEs, exposure to childhood family adversities and prior mental disorders.

Results

Prevalence of DSM-IV PTSD associated with randomly-selected sexual assaults was 20.2%. PTSD was more common for repeated than single-occurrence victimization and positively associated with prior TEs and childhood adversities. Respondent perception that she could have prevented the assault interacted with history of mental disorder such that it reduced odds of PTSD but only among women without prior disorders (OR 0.2, 95% CI 0.1-0.9). The final model estimated that 40.3% of women with PTSD would be found among the 10% with the highest predicted risk.

Conclusions

Whether counterfactual preventability cognitions are adaptive may depend on mental health history. Predictive modelling may be useful in targeting high-risk women for preventive interventions.

Keywords: posttraumatic stress disorder, PTSD, sexual assault

Introduction

Sexual assault, a term that includes child and adult sexual abuse, rape and intimate partner sexual violence, is a global public health concern (Dartnall and Jewkes 2013; Abrahams et al. 2014) with the potential for a wide range of physical and mental health consequences (Gilbert et al. 2009; Jina and Thomas 2013). Among the mental health consequences, there is a particularly robust association between sexual assault and the development of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (Kessler et al. 1995; Maniglio 2009) (Breslau et al. 1998; Chen et al. 2010). The fact that not all of those who experience sexual assault go on to develop PTSD has made identifying the predictors of PTSD development among those exposed to sexual assault a research priority. This kind of research has practical application because although interventions exist to prevent PTSD after sexual assault (Kearns et al. 2012; Rothbaum et al. 2012) they are resource-intensive, highlighting the importance of understanding who is most in need of treatment.

Prior research has identified a range of predictors of PTSD among sexual assault survivors including socio-demographics (younger age, female, less education), assault characteristics (perpetrator known to victim, high perceived threat, violence), prior mental disorders, prior trauma history, and post-assault cognitions including self-blame (Nishith et al. 2000; Ullman and Filipas 2001; Ozer et al. 2003; Ullman et al. 2007; Maikovich et al. 2009; Najdowski and Ullman 2009; Armour et al. 2012; Möller et al. 2014). However, methodological limitations may have biased assessments of these predictors, as many prior studies were based on clinical or other self-selected samples of sexual assault survivors (Ullman et al. 2007; Armour et al. 2012; Möller et al. 2014). Although community surveys have been used to address this problem, the majority of community surveys assess PTSD based on the ‘worst event’ method. That is, respondents are asked whether they have experienced a number of different traumatic events and then asked to identify their worst event. PTSD is then assessed in relation to the worst event. This approach often overestimates conditional risk of PTSD in relation to sexual assault because worst traumas are atypical and presumably have a higher risk of PTSD compared with more typical traumas (Breslau et al. 1998; Norris et al. 2003). In the present study, this problem was addressed by assessing PTSD in relation to a computer-generated random traumatic event selected from among the respondent’s lifetime traumatic events. The results here are thus reported in relation to a representative sample of sexual assaults that more accurately reflect the range of such experiences in the population.

One further limitation of prior population based studies is that they came largely from high income countries, limiting generalizability of findings. The present study examines prevalence and predictors of PTSD related to randomly-selected sexual assaults in general population samples of women in 11 high, middle and low income countries in the WHO World Mental Health (WMH) Survey Initiative (www.hcp.med.harvard.edu/wmh).

Methods

Samples

The WMH surveys are community epidemiological surveys using consistent field procedures and instruments (Kessler and Ustun 2008). The data reported here come from a subset of 12 WMH surveys in 11 countries (see Table 1) that used an expanded assessment of sexual assault. A total of 17,970 women in these surveys were asked about lifetime TE exposure. Those who reported TE exposure had one lifetime occurrence of one TE selected using a probability procedure (their randomly-selected TE). Sexual assault was the randomly-selected TE for 411 women. These cases were weighted by the inverse of their probability of selection to generate a representative sample of sexual assaults. Each survey was based on household residents using a multi-stage clustered area probability sample design. Response rates ranged from 50.6% (Belgium) to 97.2% (Colombia) and had a weighted mean of 71.4% across surveys. WMH sampling procedures are described in more detail elsewhere (Heeringa et al. 2008).

Table 1.

Distribution of lifetime exposure to traumatic experiences (TEs) and sexual assault among Part II female respondents in the participating WMH surveys (n=17,970)a

| Proportion of respondents exposed to any lifetime TE

|

Proportion of respondents exposed to any lifetime sexual assault

|

Mean number of sexual assaults among those exposed to any sexual assault

|

Sexual assaults as a proportion of all lifetime TEs

|

(n) of randomly selected sexual assaults | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | (SE) | % | (SE) | Mean | (SE) | % | (SE) | ||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

| I. High income countries | |||||||||

| Belgium | 63.3 | (3.7) | 6.5 | (1.6) | 2.2 | (0.3) | 7.0 | (1.6) | (7) |

| Germany | 65.8 | (3.0) | 13.5 | (1.8) | 2.1 | (0.2) | 11.7 | (2.2) | (21) |

| Netherlands | 65.3 | (3.1) | 9.5 | (1.2) | 2.7 | (0.2) | 12.1 | (1.7) | (22) |

| Northern Ireland | 56.9 | (1.8) | 9.1 | (0.8) | 2.7 | (0.4) | 12.9 | (1.9) | (18) |

| Spain | 50.1 | (1.8) | 1.8 | (0.5) | 1.9 | (0.1) | 2.9 | (0.7) | (7) |

| Spain – Murcia | 63.2 | (3.4) | 4.0 | (0.9) | 3.3 | (0.4) | 8.9 | (2.1) | (10) |

| United States | 80.8 | (1.2) | 26.1 | (1.3) | 2.6 | (0.1) | 16.6 | (0.6) | (201) |

| Total | 67.8 | (0.9) | 14.5 | (0.7) | 2.6 | (0.5) | 13.9 | (0.5) | (286) |

| II. Low or middle income countries | |||||||||

| Colombia – Medellin | 70.4 | (3.2) | 14.6 | (1.5) | 2.2 | (0.2) | 8.9 | (1.3) | (57) |

| Lebanon | 82.2 | (3.1) | 3.5 | (0.7) | 1.6 | (0.1) | 1.8 | (0.4) | (6) |

| Mexico | 67.0 | (1.9) | 12.7 | (1.3) | 2.1 | (0.2) | 10.8 | (1.4) | (29) |

| South Africa | 72.9 | (1.5) | 5.4 | (0.6) | 1.6 | (0.1) | 3.1 | (0.4) | (11) |

| Ukraine | 84.0 | (1.8) | 10.3 | (1.2) | 1.8 | (0.2) | 5.6 | (0.8) | (22) |

| Total | 73.9 | (1.0) | 8.9 | (0.5) | 1.9 | (0.1) | 5.9 | (0.4) | (125) |

| III. Total | 70.4 | (0.7) | 12.1 | (0.5) | 2.4 | (0.3) | 10.2 | (0.3) | (411) |

A total of 17,970 women were asked about lifetime TE exposure in these 12 surveys. Eight additional surveys also asked about lifetime TEs but were excluded because there were no cases of PTSD associated with randomly selected sexual assaults in those surveys. The numbers of randomly-selected sexual assaults were small in these surveys: Brazil (n=4), Colombia (n=26), Israel (n=13), Japan (n=4), Peru (n=17), Romania (n=5), France (n=8), Italy (n=7). Male respondents were excluded because of the small number across surveys whose randomly-selected event was a sexual assault victimization (n=32).

Field procedures

Interviews were administered face-to-face by trained lay interviewers in respondent homes. All procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. The interview schedule was developed in English and translated into other languages using an extensive WHO protocol that involved forwards translation, the convening of an expert panel to review the translation and conduct pre-testing and cognitive interviewing, then independent backwards translation with emphasis on conceptual rather than literal equivalence (Harkness et al. 2008). Interviews were in two parts. Part I, administered to all respondents, assessed core DSM-IV mental disorders (n=51,002 respondents across all surveys). Part II assessed additional disorders and correlates, including questions about traumatic events and PTSD, and was administered to 100% of Part I respondents who met lifetime criteria for any Part I disorder and a probability subsample of other Part I respondents (n=25,819). Part II respondents were weighted to adjust for differential within and between household selection, selection into Part II, and deviations between the sample and population demographic-geographic distributions (Heeringa et al. 2008).

Measures

Traumatic events (TEs)

Part II respondents were asked about lifetime exposure to 27 types of TEs in addition to exposure to“any other” TE and to a private TE that the respondent did not want to name out of embarrassment. A listing of the TEs can be found elsewhere (Benjet et al. 2016). Information was obtained on age when the TE first happened and number of lifetime occurrences. One occurrence of one lifetime TE was selected for each respondent from among the TEs reported using a probability procedure. Retrospective reports were used to assess PTSD associated with this randomly-selected TE.

Characteristics of sexual assaults

Two of the TE questions asked about sexual assault. The preamble in introducing these questions was: “The next two questions are about sexual assault. The first is about rape. We define this as either having sexual intercourse with you or penetrating your body with a finger or object when you did not want them to either by threatening you or using force, or when you were so young that you didn’t know what was happening. Did this ever happen to you?” The next question asked: “Other than rape, were you ever sexually assaulted, where someone touched you inappropriately, or when you did not want them to?” Respondents for whom rape or sexual assault was their randomly-selected TE were then asked: their age when they first experienced the sexual assault; the identity of the perpetrator (spouse/partner, parent/guardian, step-relative, other relative, anyone else that the respondent knew, and a stranger); whether the assault was a repeated or one-time occurrence; and whether, as they looked back on it, “realistically (emphasis in original) was there anything you could have done to prevent this from happening?”

Mental disorders

Lifetime mental disorders were assessed with the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI)(Kessler and Ustun 2004), a fully-structured interview administered by trained lay interviewers. The CIDI assessed lifetime DSM-IV mood disorders (major depressive disorder, dysthymic disorder, bipolar disorder), lifetime anxiety disorders (panic disorder, agoraphobia, specific phobia, social phobia, generalized anxiety disorder, prior [to the randomly selected TE] posttraumatic stress disorder, and separation anxiety disorder), disruptive behaviour disorders (attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, oppositional-defiant disorder, conduct disorder, and intermittent explosive disorder), and substance disorders (alcohol abuse with or without dependence; drug abuse with or without dependence). Age-of-onset (AOO) of each disorder was assessed using special probing techniques shown experimentally to improve recall accuracy (Knauper et al. 1999). This allowed us to determine based on retrospective AOO reports whether each respondent had a history of each disorder prior to the age of occurrence of the randomly selected TE. DSM-IV organic exclusion rules and diagnostic hierarchy rules were used (other than for ODD, which was defined with or without CD, and substance abuse, which was defined with or without dependence). Agoraphobia was combined with panic disorder because of low prevalence. Dysthymic disorder was combined with major depressive disorder for the same reason. These aggregations resulted in information being available on 14 prior (to age of the randomly selected TE) lifetime disorders (one of which was prior PTSD). As detailed elsewhere (Haro et al. 2006), generally good concordance was found between these CIDI diagnoses and blinded clinical diagnoses based on clinical reappraisal interviews with the SCID.

PTSD

Blinded clinical reappraisal interviews with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID) conducted in four WMH countries found CIDI-SCID concordance for DSM-IV PTSD to be moderate (AUC=.69)(Haro et al. 2006). Sensitivity and specificity were .38 and .99, respectively, resulting in a likelihood ratio positive (LR+) of 42.0, which is well above the threshold of 10 typically used to consider screening scale diagnoses definitive (Altman et al. 2000). Consistent with the high LR+, the proportion of CIDI cases confirmed by the SCID was 86.1%, suggesting that the vast majority of CIDI/DSM-IV PTSD cases would independently be judged to have DSM-IV PTSD by trained clinicians.

Other predictors of PTSD

Seven classes of predictors were investigated. The first three were described above: characteristics of the sexual assault, perceived preventability, and respondent’s history of prior DSM-IV mental disorders. The fourth was socio-demographics: age, education, marital status, each defined at the time of the randomly-selected TE, and gender. The final three were vulnerabilities present at the time of the TE: prior lifetime history of sexual assault; exposure to other lifetime TEs; and exposure to each of 12 childhood (occurring before age 18) family adversities (including three types of interpersonal loss [parental death, parental divorce, other separation from parents], four types of parental maladjustment [mental illness, substance misuse, criminality, violence], three types of maltreatment [physical abuse, sexual abuse, neglect] and two other childhood adversities [life-threatening respondent physical illness, family economic adversity]. Details on measurement of the childhood adversities (CAs) are presented elsewhere (Kessler et al. 2010).

Analysis Methods

As noted above, each randomly-selected TE was weighted by the inverse of its probability of selection. For example, a respondent who reported 3 TE types and 2 occurrences of the randomly-selected type would receive a TE weight of 6.0. The product of the Part II weight with the TE weight was used in analyses, yielding a sample that is representative of all lifetime TEs occurring to all respondents. Respondents with a randomly-selected sexual assault are the focus of this report. The sum of the consolidated weights across this subset of respondents was standardized in each country for purposes of pooled cross-national analysis to equal the observed number of respondents with randomly-selected sexual assaults.

Logistic regression was used to examine predictors of PTSD after the randomly-selected sexual assault pooled across surveys, including dummy control variables for surveys. Predictors were entered in blocks, beginning with socio-demographics (Model 1), followed in sequence by sexual assault characteristics (Model 2), prior TE and CA exposure (Model 3), and prior mental disorders (Model 4). We also evaluated interactions of sexual assault characteristics and perceived preventability with prior vulnerability factors (Model 5). We evaluated the significance of between-survey differences in coefficients with interaction tests. Statistical significance was evaluated using .05-level two-sided tests. The design-based Taylor series method (Wolter 2007) implemented in the SAS software system (Institute 2011) was used to adjust for weighting and clustering. Design-based Wald F tests were used to evaluate significance of predictor sets.

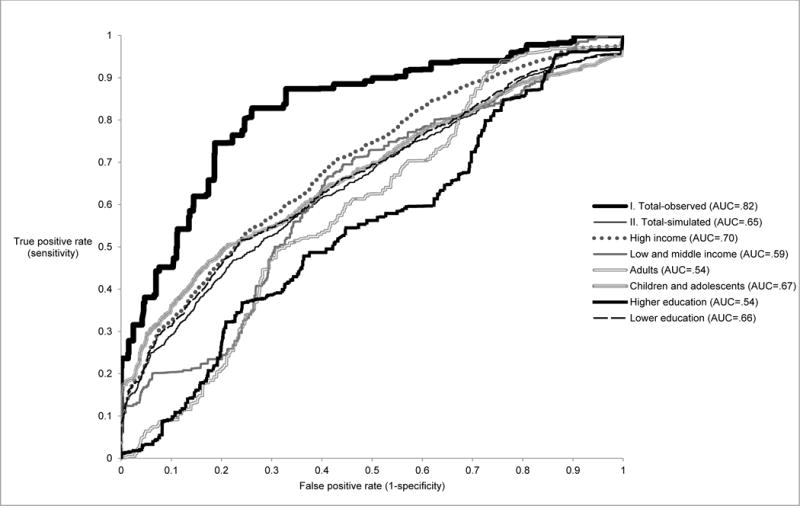

Once the final model (Model 5) was estimated, a predicted probability of PTSD was generated for each respondent from model coefficients. A receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was then calculated from this summary predicted probability (Zou et al. 2007) to quantify overall prediction accuracy (Hanley and McNeil 1983). We used the method of replicated 10-fold cross-validation with 20 replicates (i.e., 200 separate estimates of model coefficients) to correct for the over-estimation of prediction accuracy when both estimating and evaluating model fit in a single sample (Smith et al. 2014).

Results

Traumatic event exposure

A weighted 70.4% of female respondents across surveys reported lifetime TE exposure (Table 1). Sexual assaults were reported by 12.1% of female respondents, ranging from 1.8% in Spain to 26.1% in the US, with a mean of 2.4 occurrences per respondent. These assaults accounted for 10.2% of all lifetime TEs among women.

Prevalence of PTSD associated with sexual assault

Prevalence of PTSD associated with the randomly-selected sexual assaults averaged 20.2% (n=108) across surveys (Table 2) and was significantly higher in high than low/middle income countries (24.0% vs. 11.7%; χ21=5.4, p=.020).

Table 2.

Prevalence of DSM-IV/CIDI PTSD associated with sexual assault among female respondents with randomly selected sexual assault by survey (n=411)a

| % PTSD | (95% CI) | Number with PTSDb | Total sample sizeb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| I. High income countries | ||||

| Belgium | 96.9 | (60.7-99.8) | (4) | (7) |

| Germany | 5.3 | (1.0-23.4) | (4) | (21) |

| Netherlands | 13.3 | (3.6-38.9) | (5) | (22) |

| Northern Ireland | 19.7 | (6.0-48.4) | (4) | (18) |

| Spain | 55.5 | (23.9-83.2) | (4) | (7) |

| Spain – Murcia | 17.2 | (4.1-50.3) | (1) | (10) |

| United States | 24.2 | (15.2-33.1) | (68) | (201) |

| Total | 24.0 | (16.2-31.7) | (90) | (286) |

| II. Low or middle income countries | ||||

| Colombia – Medellin | 8.4 | (3.1-20.8) | (6) | (57) |

| Lebanon | 21.9 | (4.8-60.9) | (1) | (6) |

| Mexico | 11.1 | (2.8-35.0) | (6) | (29) |

| South Africa | 17.8 | (5.0-47.3) | (3) | (11) |

| Ukraine | 15.0 | (3.6-45.4) | (2) | (22) |

| Total | 11.7 | (3.9-19.5) | (18) | (125) |

| III. Total | 20.2 | (14.3-26.1) | (108) | (411) |

| High vs low or middle difference χ21 | 5.4 |

Each respondent who reported lifetime exposure to one or more Traumatic Event (TEs) had one occurrence of one such experience selected at random for detailed assessment. Each of these randomly selected TEs was weighted by the inverse of its probability of selection at the respondent level to create a weighted sample of TEs that was representative of all TEs in the population. The randomly selected sexual assaults were the subset of these randomly selected TEs involving sexual assault. The sum of weights of the randomly selected sexual assaults was standardized within surveys to sum to the observed number of female respondents whose randomly selected TE was a sexual assault. The n reported in the last column of this table represents that number of respondents. The results reported here are for the surveys where at least one female respondent with a randomly selected sexual assault met DSM-IV/CIDI criteria for PTSD related to that TE. Eight surveys were excluded because there were no cases of PTSD associated with the randomly selected sexual assault: Brazil (n=4), Colombia (n=26), Israel (n=13), Japan (n=4), Peru (n=17), Romania (n=5), France (n=8), Italy (n=7). Male respondents were excluded because of the small number of men across surveys whose randomly-selected TE was sexual assault (n=32).

The reported sample sizes are unweighted. The unweighted proportions of respondents with PTSD do not match the prevalence estimates in the first column because the latter were based on weighted data. Confidence intervals that include 0.0% as the lower bound were estimated using the Wilson-score method.35

Predictors of PTSD

Models 1 and 2

Respondent age, education, and marital status at time of assault were not significant predictors of PTSD (Table 3). Two sexual assault characteristics were associated with elevated odds of PTSD: the identity of the perpetrator, with respondents refusing to disclose this identity (5.3% of respondents) having significantly elevated odds of PTSD (OR 4.8; 95% CI 1.0-23.7), and repeated occurrences (42.4% of respondents) associated with significantly elevated odds (OR 4.6; 95% CI 2.3-9.2). The distinction between rape and other sexual assault was not significant in model 2 although rape had higher odds of PTSD in the model that did not control for other assault characteristics. Perceived preventability was not a significant predictor of PTSD. We elaborated the model to include a control for number of years between age at assault and age at interview (to adjust for biased recall related to length of the recall period) and found it was not significant (OR 0.9; 95% CI 0.7-1.2).

Table 3.

Associations of socio-demographic, trauma characteristics and prior stressors with PTSD (n=411)a

| Bivariate model

|

Model 1

|

Model 2

|

Model 3

|

Model 4d

|

Model 5 d

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

| I. Socio-demographics | ||||||||||||

| Age in decades | 0.8 | (0.5-1.2) | 0.8 | (0.5-1.5) | 0.9 | (0.5-1.7) | 0.8 | (0.4-1.6) | 0.7 | (0.3-1.4) | 0.7 | (0.3-1.3) |

| Educationb | 0.8 | (0.6-1.1) | 0.8 | (0.5-1.2) | 0.9 | (0.5-1.4) | 1.0 | (0.6-1.6) | 0.9 | (0.5-1.6) | 1.0 | (0.5-1.7) |

| Never (vs. ever) married | 0.8 | (0.3-2.0) | 0.5 | (0.2-1.4) | 0.5 | (0.2-1.5) | 0.6 | (0.2-1.8) | 0.6 | (0.2-1.8) | 0.6 | (0.2-1.9) |

| II. Trauma characteristics | ||||||||||||

| Rape (vs. sexual assault) | 1.7* | (1.1-2.7) | 1.7* | (1.1-2.7) | 1.7 | (0.9-3.4) | 1.8 | (0.9-3.7) | 1.7 | (0.8-3.5) | 1.9* | (1.0-3.7) |

| Perpetrator refused (vs other) | 5.0 | (1.0-26.1) | – | – | 4.8* | (1.0-23.7) | 4.9* | (1.0-24.0) | 5.1* | (1.0-25.9) | 5.4* | (1.1-26.7) |

| Repeated occurrence (vs. single) | 4.7* | (2.5-8.6) | – | – | 4.6* | (2.3-9.2) | 4.8* | (2.3-9.8) | 5.0* | (2.5-10.1) | 4.5* | (2.1-9.4) |

| III. Perceived preventability | ||||||||||||

| Perception R could have prevented assault | ||||||||||||

| Total | 0.5 | (0.2-1.3) | – | – | 0.5 | (0.2-1.4) | 0.5 | (0.2-1.5) | 0.6 | (0.2-1.6) | – | – |

| Without prior mental disorders | 0.2* | (0.1-0.7) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.2 | (0.0-1.1) |

| With at least one prior mental disorder | 1.3 | (0.5-3.6) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1.2 | (0.4-4.4) |

| IV. Prior vulnerability factors | ||||||||||||

| Prior exposure to any traumatic event | 3.3* | (1.8-6.1) | – | – | – | – | 2.1* | (1.0-4.4) | 1.7 | (0.8-3.7) | 2.0 | (0.9-4.1) |

| Maladaptive family functioning CAs | 1.4* | (1.0-2.1) | – | – | – | – | 1.6* | (1.1-2.4) | 1.5 | (1.0-2.3) | 1.6* | (1.0-2.5) |

| Prior mental disorders | 1.5* | (1.1-2.0) | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1.5* | (1.0-2.3) | 1.2 | (0.8-2.0) |

| F(7,70) (9,68) (10,67) (11,66)c | – | – | 2.7* | p=.036 | 3.8* | p=.002 | 5.0* | p<.001 | 4.6* | p<.001 | 6.5* | p<.001 |

| AUC | .69 | .78 | .80 | .82 | .83 | |||||||

Significant at the .05 level, two-sided test.

Models were based on weighted data. See the text for details. Each model included dummy variable controls for WMH survey.

Values for education ranged from 1 to 4 (low, low-average, high-average, and high using a country-specific coding scheme described elsewhere.36

Design-based F tests were used to evaluate significance of predictor sets, with numerator degrees of freedom equal to number of predictors and denominator degrees of freedom equal to number of geographically-clustered sampling error calculation units containing randomly-selected sexual assaults across surveys (n=249) minus the sum of primary sample units from which these sampling error calculation units were selected (n=173) and one less than the number of variables in the predictor set,35 resulting in 76 denominator degrees of freedom in evaluating bivariate associations and fewer in evaluating multivariate associations.

Model 4 was expanded to evaluate 6 interactions between 2 characteristics of the trauma (repeated occurrence; R could have prevented) and 3 prior stress measures (any prior TE; number of MFF CA's, and prior mental disorders). The global significance associated for these six interaction terms was F6,71=1.1; p=.36. Individual significance was associated twice, using traditional p-values and again using p-values adjusted for false discovery rate (FDR): Repeated occurrence X any prior TE (p=.70; pFDR=.99); Repeated occurrence X number of MFF CA's (p=.91; pFDR=.99); Repeated occurrence X prior mental disorders (p=.30; pFDR=.81); R could have prevented X any prior TE (p=.99; pFDR=.99); R could have prevented X number of MFF CA's (p=.41; pFDR=.81);R could have prevented X prior mental disorders (p=.023; pFDR=.14).

Model 3

Preliminary analyses of the joint associations between prior exposure to the 29 TEs and PTSD after the focal sexual assault found that the most stable specification had a single predictor for prior exposure to any TE (71.6% of respondents). Net of the predictors in Model 2, this dichotomy had OR 2.1; 95% CI 1.0-4.4 predicting PTSD. Preliminary analyses of the joint associations between CAs and PTSD after the focal sexual assault found that a count of maladaptive family functioning childhood adversities (27.5% of respondents had 1 and 29.7% 2+) was the most parsimonious measure, with OR 1.6; 95% CI 1.1-2.4.

Model 4

Preliminary analyses of the joint associations between prior lifetime DSM-IV/CIDI disorders and PTSD after the focal sexual assault found that a count of number of mental disorders (57.4% of respondents had 0, 22.1% 1, and 20.4% 2+) was the most parsimonious measure, with OR 1.5; 95% CI 1.0-2.3. The introduction of this variable into Model 4 led to the OR for prior TEs to become nonsignificant, suggesting that the association of prior TEs with PTSD was partly mediated by intervening mental disorders.

Model 5

We investigated interactions of trauma characteristics and perceived preventability with prior vulnerability factors. The only significant interaction was between prior mental disorders and perceived preventability of the assault (χ21 = 6.0, p=.016). Perceived preventability was associated with reduced odds of PTSD among respondents with no history of prior mental disorders (OR 0.2; 95% CI 0.1-1.1) and increased odds of PTSD among those with such a history (OR 1.2; 95% CI 0.4-4.0), neither of which is significant even though the difference between the two is significant. However, the inverse association of perceived preventability with PTSD among respondents with no prior mental disorder was significant in the bivariate model (OR 0.2; 95% CI 0.1-0.7). Caution is needed in interpreting this result, though, as the set of six interactions was not significant overall (F6,71 = 1.1, p=.36) and the interaction between perceived preventability and prior mental disorder was only significant at the 0.14 level when we adjusted for multiple comparisons using the false discovery rate method (Benjamini and Hochberg 1995). The distinction between rape and other sexual assault was also significant in this model.

Consistency and strength of overall model predictions

We compared overall model fit in subsamples by calculating individual-level predicted probabilities from Model 5, estimating ROC curves from these predicted probabilities (Figure 1), and calculating subsample AUCs. As noted earlier, we adjusted for over-fitting by estimating AUC with 20 simulated replicates of 10-fold cross-validated predictions. AUC was .83 in the total observed sample, .64 in the total simulated sample, and .54-.69 in simulated subsamples defined by respondent sex, age, and education. Although the latter AUC values are weak to intermediate overall, the steep slope of the simulated ROC curves when the false negative rate is low means that we would expect a high proportion of cases in other samples to be found by focusing on respondents with high predicted risk. Specifically, we estimate that 30.6% of all women with PTSD (sensitivity) would be found among the 10% of women with highest predicted risk if the model coefficients were applied to an independent sample (compared to an observed 40.3% in the WMH data) (Table 4). Among the 10% of women with highest predicted risk, we would expect 43.7% (49.6% in the WMH data) to develop PTSD in the absence of a targeted preventive intervention (positive predictive value).

Fig. 1.

Receiver operating characteristic curves for the prediction equation in the total sample and subsamples

Table 4.

Observed sensitivity and positive predictive value of PTSD in the top 10th percentile of predicted PTSD in the total sample and projected values of these statistics in independent samples based on 20 replications of 10-fold cross-validation

| Sensitivitya

|

Positive Predictive Valueb

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % PTSD | (SE) | % PTSD | (SE) | |

|

|

|

|||

| I. Observed | ||||

| Total sample | 40.3 | (5.1) | 49.6 | (8.3) |

| II. Simulated | ||||

| Total sample | 30.6 | (4.9) | 43.7 | (8.2) |

| Country income | ||||

| High | 36.9 | (5.0) | 48.2 | (8.7) |

| Low or middle | 1.3 | (0.3) | 3.2 | (1.0) |

| Age | ||||

| 18+ years old | 8.5 | (4.4) | 18.4 | (9.5) |

| < 18 years old | 36.8 | (7.5) | 47.9 | (8.9) |

| Education | ||||

| Low/low-average | 35.4 | (6.1) | 45.4 | (8.5) |

| High/high-average | 4.3 | (1.5) | 15.9 | (8.5) |

Sensitivity is the proportion of all PTSD found among the 10% of respondents with the highest predicted probabilities based on Model 5 in Table 3.

Positive predictive value is the prevalence of PTSD among respondents in the row who are among the 10% in the total sample with the highest predicted probabilities based on the Model 5 in Table 3.

As model fit would be weaker if the coefficients from this model were applied to an independent sample 20 replicates of 10-fold cross-validation were used to simulate the expected values of sensitivity and positive predicted value in an independent sample if the coefficients estimated in the current sample were applied to that hypothetical sample. See Smith GC, Seaman SR, Wood AM, Royston P & White IR (2014)34 for a discussion.

Sensitivity analysis

Given that AUC was lower for respondents with adult than child-adolescent ages of exposure and those with low/low-average educations in low/middle income countries, we elaborated the final model (Table 3, Model 5) to include interactions between each of these 3 potentially important specifiers and the significant predictors in the final model. While global interactions were significant with both age-at-exposure and county income, only one interaction was significant in each set (prior TEs with age-at-exposure; could have prevented with country income) and both of those interactions were highly unstable (OR 42.7; 95% CI 3.5-525.5 for TEs × older age-at-exposure; OR 208.2; 95% CI 11.7-3721.0 for could have prevented x high country income) and replicated cross-validated model performance was not improved by using this more complex specification than Model 5.

Discussion

These results should be considered in light of the study limitations. One significant limitation relates to the sample of sexual assault survivors. This was not large enough to allow the development of a fine-grained prediction model and due to the low prevalence of sexual assaults among males in the sample this analysis could focus on women only. A second significant limitation is the cross-sectional nature of the data with reliance on retrospective reporting of sexual assaults and mental disorders. Sexual assaults are known to be quite substantially under-reported (Williams 1994; Widom and Morris 1997) with unknown effects on the estimates of associated mental health outcomes. The use of face-to-face interviews may have increased the likelihood of non-disclosure of sexual assaults. Retrospective reports of mental disorders also underestimate prevalence (Takayanagi et al. 2014) and may result in inaccuracies in onset timing (Simon and Von Korff 1995). Recall of prior lifetime TE exposures and/or mental disorders may also have differed among those with PTSD versus those without PTSD (Zoellner et al. 2000; Brewin 2011). It is difficult to determine the effects of these multiple biases on the predictive modelling but they underscore the fact that this study must be considered exploratory in nature with confirmation required in prospective designs. A third important limitation is that the WMH surveys did not assess include other potentially important predictors of PTSD following sexual assault such as perceived life threat, other post-assault cognitions and social factors.

Nonetheless, this is a rare general population study of PTSD associated with a representative sample of sexual assaults, and the largest such study to date. We are aware of only one prior study of randomly-selected traumas and PTSD: the Detroit Area Survey of Trauma (Breslau et al. 1998), The Detroit study, based on 59 sexual assault survivors, found higher PTSD prevalence of 49% among rape survivors and 24% among other sexual assault survivors, compared with 20.2% for rape and sexual assault combined in this study. The higher prevalence of PTSD in the Detroit study may reflect its setting (urban Detroit) and lower up age bound. The other important difference is that this is an international study and we found PTSD prevalence in general (that is, not just among sexual assault survivors) to be lower in the lower income countries, bringing the average prevalence of PTSD across countries down. It should be noted that this cross-national pattern is not confined to PTSD but is evident in the prevalence of many of the mental disorders assessed in the WMH surveys; it may reflect a wide range of methodological and/or substantive factors (Scott et al. Forthcoming).

We found perpetrator identity was a significant predictor of PTSD, although only the undisclosed (refused) type. If we assume that refused disclosure is indicative of a perpetrator who is known to the victim, then this finding is consistent with prior research showing greater PTSD risk when perpetrators are intimates of victims(Ullman et al. 2006; Temple et al. 2007; Campbell et al. 2009), possibly due to feelings of shame and self-blame. Although we did not find elevated PTSD risk associated with other known perpetrators (e.g., spouse, relatives), this may be due to the inclusion in models of an indicator of repeated occurrence of the assault, as repeat assaults are usually perpetrated by intimates of victims.

It is notable that we did not find prior sexual assaults associated with increased PTSD risk which is inconsistent with prior studies (Nishith et al. 2000; Chen et al. 2010). But we did find that a wide range of prior trauma exposures, including but not limited to prior sexual assaults, were significant predictors of PTSD. It is also noteworthy that maladaptive family functioning childhood adversities were independent predictors of PTSD; sexual assault by a family member was included in the composite scale of these childhood adversities. But our detailed preliminary modeling of both the TE data and childhood adversities data suggest that the role of prior sexual assault history is difficult to disentangle from other related TEs and childhood adversities, consistent with prior research (Mullen et al. 1993; Mullen et al. 1996).

We found that respondent perception that they could have prevented the assault was associated with reduced risk of PTSD among women without prior mental disorder, but no such protective effect was found among women with prior mental disorder. Counterfactual theory (Roese 1997) poses that after events that provoke negative emotions, people reflect on how things might have been different. These reflections take the form of either ‘upwards counterfactuals’ that focus on how things could have turned out better (“if only…”) or ‘downwards counterfactuals’ that focus on how things could have turned out worse (“at least…”) (Roese 1997). Upwards counterfactual thinking is hypothesized to be distressing in the short-term but adaptive in the longer term because it leads to the development of behavioral intentions that generated a sense of future control (Roese 1997). Research among sexual assault survivors has not generally supported this hypothesis (Branscombe et al. 2003; Miller et al. 2010) but at least one study (not among sexual assault survivors) suggests that whether upwards counterfactuals are adaptive may depend on mental health status (Markman and Miller 2006). This might explain why we found that positive endorsement of an item tapping counterfactual preventability thinking was associated with reduced risk of PTSD only among women without prior mental disorder. But this needs confirmation in a prospective study of sexual assault survivors utilizing more comprehensive assessment of counterfactual preventability cognitions. .

The final result of note is that our multivariate model suggests that 40.3% (30.6% in the simulation) of sexual assault victims with PTSD would be found among the 10% of victims with highest predicted risk, and that 49.6% (43.7% in the simulation) of those in the model-classified highest risk group would go on to develop PTSD. These findings are consistent with other more general studies showing that PTSD can be predicted in the peritraumatic period from information about pre-trauma risk factors, trauma characteristics, and early trauma responses (Galatzer-Levy et al. 2014; Kessler et al. 2014; Karstoft et al. 2015). These expectations are, of course, based on the possibly incorrect assumption that the associations found here in the retrospective WMH data would also hold in prospective analyses. We are unable to evaluate the plausibility of this assumption here, but the results are nonetheless useful in showing strong enough associations to warrant future prospective studies that test and refine this kind of model.

In conclusion, given the limitations of the retrospective data the value of this study is less in the specific predictors identified by our model than in the fact that our study shows that it might be possible in a prospective analysis to develop a prediction model that targets sexual assault victims at high risk of developing PTSD. If this ability of multivariate modelling to predict those at risk of PTSD following sexual assault is borne out in prospective data it will be of great practical value in the development of screening assessments to identify those sexual assault survivors most in need of preventive interventions. This is a necessary step in optimizing the clinical utility of the resource-intensive preventive interventions for sexual assault survivors.

Acknowledgments

In the past 3 years, Dr. Kessler received support for his epidemiological studies from Sanofi Aventis, was a consultant for Johnson & Johnson Wellness and Prevention, and served on an advisory board for the Johnson & Johnson Services Inc. Lake Nona Life Project. Kessler is a co-owner of DataStat, Inc., a market research firm that carries out healthcare research. In the past 3 years, Dr. Stein has received research grants and/or consultancy honoraria from AMBRF, Biocodex, Cipla, Lundbeck, National Responsible Gambling Foundation, Novartis, Servier, and Sun.

Funding/Support: This work was carried out in conjunction with the World Health Organization World Mental Health (WMH) Survey Initiative which is supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH; R01 MH070884 and R01 MH093612-01), the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the Pfizer Foundation, the US Public Health Service (R13-MH066849, R01-MH069864, and R01 DA016558), the Fogarty International Center (FIRCA R03-TW006481), the Pan American Health Organization, Eli Lilly and Company, Ortho-McNeil Pharmaceutical, Inc., GlaxoSmithKline, and Bristol-Myers Squibb. We thank the staff of the WMH Data Collection and Data Analysis Coordination Centres for assistance with instrumentation, fieldwork, and consultation on data analysis. None of the funders had any role in the design, analysis, interpretation of results, or preparation of this paper. A complete list of all within-country and cross-national WMH publications can be found at http://www.hcp.med.harvard.edu/wmh/. The Mental Health Study Medellín – Colombia was carried out and supported jointly by the Center for Excellence on Research in Mental Health (CES University) and the Secretary of Health of Medellín. The ESEMeD project is funded by the European Commission (Contracts QLG5-1999-01042; SANCO 2004123, and EAHC 20081308), the Piedmont Region (Italy)), Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria, Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Spain (FIS 00/0028), Ministerio de Ciencia y Tecnología, Spain (SAF 2000-158-CE), Departament de Salut, Generalitat de Catalunya, Spain, Instituto de Salud Carlos III (CIBER CB06/02/0046, RETICS RD06/0011 REM-TAP), and other local agencies and by an unrestricted educational grant from GlaxoSmithKline. The Lebanese National Mental Health Survey (L.E.B.A.N.O.N.) is supported by the Lebanese Ministry of Public Health, the WHO (Lebanon), National Institute of Health/Fogarty International Center (R03 TW006481-01), Sheikh Hamdan Bin Rashid Al Maktoum Award for Medical Sciences, anonymous private donations to IDRAAC, Lebanon, and unrestricted grants from AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, Hikma Pharmaceuticals, Janssen Cilag, Lundbeck, Novartis, and Servier. The Mexican National Comorbidity Survey (MNCS) is supported by The National Institute of Psychiatry Ramon de la Fuente (INPRFMDIES 4280) and by the National Council on Science and Technology (CONACyT-G30544- H), with supplemental support from the PanAmerican Health Organization (PAHO). The Northern Ireland Study of Mental Health was funded by the Health & Social Care Research & Development Division of the Public Health Agency. The Psychiatric Enquiry to General Population in Southeast Spain – Murcia (PEGASUS-Murcia) Project has been financed by the Regional Health Authorities of Murcia (Servicio Murciano de Salud and Consejería de Sanidad y Política Social) and Fundación para la Formación e Investigación Sanitarias (FFIS) of Murcia. The South Africa Stress and Health Study (SASH) is supported by the US National Institute of Mental Health (R01-MH059575) and National Institute of Drug Abuse with supplemental funding from the South African Department of Health and the University of Michigan. Dr. Stein is supported by the Medical Research Council of South Africa (MRC). The Ukraine Comorbid Mental Disorders during Periods of Social Disruption (CMDPSD) study is funded by the US National Institute of Mental Health (RO1-MH61905). The US National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) is supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH; U01-MH60220) with supplemental support from the National Institute of Drug Abuse (NIDA), the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF; Grant 044708), and the John W. Alden Trust.

Role of Funder/Sponsor: The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

The WHO World Mental Health Survey collaborators are Sergio Aguilar-Gaxiola, MD, PhD, Ali Al-Hamzawi, MD, Mohammed Salih Al-Kaisy, MD, Jordi Alonso, MD, PhD, Laura Helena Andrade, MD, PhD, Corina Benjet, PhD, Guilherme Borges, ScD, Evelyn J. Bromet, PhD, Ronny Bruffaerts, PhD, Brendan Bunting, PhD, Jose Miguel Caldas de Almeida, MD, PhD, Graca Cardoso, MD, PhD, Somnath Chatterji, MD, Alfredo H. Cia, MD, Louisa Degenhardt, PhD, Koen Demyttenaere, MD, PhD, John Fayyad, MD, Silvia Florescu, MD, PhD, Giovanni de Girolamo, MD, Oye Gureje, PhD, DSc, FRCPsych, Josep Maria Haro, MD, PhD, Yanling He, MD, Hristo Hinkov, MD, Chi-yi Hu, PhD, MD, Yueqin Huang, MD, MPH, Peter de Jonge, PhD, Aimee Nasser Karam, PhD, Elie G. Karam, MD, Norito Kawakami, MD, DMSc, Ronald C. Kessler, PhD, Andrzej Kiejna, MD, PhD, Viviane Kovess-Masfety, MD, PhD, Sing Lee, PhD, Jean-Pierre Lepine, MD, Daphna Levinson, PhD, John McGrath, MD, PhD, Maria Elena Medina-Mora, PhD, Jacek Moskalewicz, DrPH, Fernando Navarro-Mateu, MD, PhD, Beth-Ellen Pennell, MA, Marina Piazza, MPH, ScD, Jose Posada-Villa, MD, Kate M. Scott, PhD, Tim Slade, PhD, Juan Carlos Stagnaro, MD, PhD, Dan J. Stein, FRCPC, PhD, Margreet ten Have, PhD, Yolanda Torres, MPH, Dra.HC, Maria Carmen Viana, MD, PhD, Harvey Whiteford, PhD, David R. Williams, MPH, PhD, Bogdan Wojtyniak, ScD.

List of abbreviations

- AOO

age-of-onset

- AUC

area under the curve

- BPD, BP-I, BP-II

broadly-defined bipolar disorder, bipolar disorder I, bipolar disorder II

- CA

childhood family adversity

- CI

confidence interval

- CIDI

Composite International Diagnostic Interview

- DALY

disability adjusted life years

- DSM-IV

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders IV

- ICD-10

International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th revision

- LR+

likelihood ratio positive

- MFF

Maladaptive Family Functioning

- MVC

motor vehicle collision

- ODD

oppositional defiant disorder

- OR

odds ratio

- PTSD

post-traumatic stress disorder

- ROC

receiver operating characteristic curve

- SCID

Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV

- TE

traumatic event

- WHO

World Health Organization

- WMH

World Mental Health Survey

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: The other authors report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Kate M. Scott, Department of Psychological Medicine, University of Otago, Dunedin, Otago, New Zealand.

Karestan C. Koenen, Department of Epidemiology, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, Massachusetts, USA.

Andrew King, Department of Health Care Policy, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts, USA.

Maria V. Petukhova, Department of Health Care Policy, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts, USA.

Jordi Alonso, Health Services Research Unit, IMIM-Hospital del Mar Medical Research Institute; Pompeu Fabra University (UPF); CIBER en Epidemiología y Salud Pública (CIBERESP), Barcelona, Spain.

Evelyn J. Bromet, Department of Psychiatry, Stony Brook University School of Medicine, Stony Brook, New York, USA.

Ronny Bruffaerts, Universitair Psychiatrisch Centrum - Katholieke Universiteit Leuven (UPC-KUL), Campus Gasthuisberg, Leuven, Belgium.

Brendan Bunting, School of Psychology, Ulster University, Londonderry, Northern Ireland.

Peter de Jonge, Developmental Psychology, Department of Psychology, Rijksuniversiteit Groningen, Groningen, NL; Interdisciplinary Center Psychopathology and Emotion Regulation, Department of Psychiatry, University Medical Center Groningen, Groningen, Netherlands.

Josep Maria Haro, Parc Sanitari Sant Joan de Déu, CIBERSAM, Universitat de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain.

Elie G. Karam, Department of Psychiatry and Clinical Psychology, Faculty of Medicine, Balamand University, Beirut, Lebanon; Department of Psychiatry and Clinical Psychology, St George Hospital University Medical Center, Beirut, Lebanon; Institute for Development Research Advocacy and Applied Care (IDRAAC), Beirut, Lebanon.

Sing Lee, Department of Psychiatry, Chinese University of Hong Kong, Tai Po, Hong Kong.

Maria Elena Medina-Mora, National Institute of Psychiatry Ramón de la Fuente, Mexico, D.F.

Fernando Navarro-Mateu, IMIB-Arrixaca, CIBERESP-Murcia, Subdirección General de Salud Mental y Asistencia Psiquiátrica, Servicio Murciano de Salud, El Palmar (Murcia), Murcia, Spain.

Nancy A. Sampson, Department of Health Care Policy, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts, USA.

Victoria Shahly, Department of Health Care Policy, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts, USA.

Dan J. Stein, Department of Psychiatry and Mental Health, University of Cape Town, Cape Town, Republic of South Africa (Stein).

Yolanda Torres, Center for Excellence on Research in Mental Health, CES University, Medellin, Colombia.

Alan M. Zaslavsky, Department of Health Care Policy, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts, USA.

Ronald C. Kessler, Department of Health Care Policy, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts, USA.

References

- Abrahams N, Devries K, Watts C, Pallitto C, Petzold M, Shamu S, García-Moreno C. Worldwide prevalence of non-partner sexual violence: a systematic review. The Lancet. 2014;383:1648–1654. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62243-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altman D, Machin D, Bryant T, Gardner S. Statistics with confidence: confidence interval and statistical guidelines. BMJ Books; Bristol: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Armour C, Shevlin M, Elklit A, Mroczek D. A latent growth mixture modeling approach to PTSD symptoms in rape victims. Traumatology. 2012;18:20–28. doi: 10.1177/1534765610395627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society B. 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Benjet C, Bromet E, Karam E, Kessler R, McLaughlin K, Ruscio A, Shahly V, Stein D, Petukhova M, Hill E, Alonso J, Atwoli L, Bunting B, Bruffaerts R, Caldas-de-Almeida JM, de Girolamo G, Florescu S, Gureje O, Huang Y, Lepine J, Kawakami N, Kovess-Masfety V, Medina-Mora M, Navarro-Mateu F, Piazza M, Posada-Villa J, Scott KM, Shalev A, Slade T, ten Have M, Torres Y, Viana M, Zarkov M, Koenen KC. The epidemiology of traumatic event exposure worldwide: results from the World Mental Health Survey Consortium. Psychological Medicine. 2016;46:327–343. doi: 10.1017/S0033291715001981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branscombe NR, Wohl MJ, Owen S, Allison JA, N’gbala A. Counterfactual thinking, blame assignment, and well-being in rape victims. Basic and Applied Social Psychology. 2003;25:265–273. [Google Scholar]

- Breslau N, Kessler RC, Chilcoat HD, Schultz LR, Davis GC, Andreski P. Trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder in the community: the 1996 Detroit Area Survey of Trauma. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1998;55:626–632. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.7.626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewin CR. The nature and significance of memory disturbance in posttraumatic stress disorder. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2011;7:203–227. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032210-104544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell R, Dworkin E, Cabral G. An ecological model of the impact of sexual assault on women’s mental health. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 2009 doi: 10.1177/1524838009334456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen LP, Murad MH, Paras ML, Colbenson KM, Sattler AL, Goranson EN, Elamin MB, Seime RJ, Shinozaki G, Prokop LJ. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. Elsevier; 2010. Sexual abuse and lifetime diagnosis of psychiatric disorders: systematic review and meta-analysis; pp. 618–629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dartnall E, Jewkes R. Sexual violence against women: the scope of the problem. Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 2013;27:3–13. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2012.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galatzer-Levy IR, Karstoft K-I, Statnikov A, Shalev AY. Quantitative forecasting of PTSD from early trauma responses: A machine learning application. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2014;59:68–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2014.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert R, Widom CS, Browne K, Fergusson DM, Webb E, Janson S. Child maltreatment I. Burden and consequences of child maltreatment in high-income countries. The Lancet. 2009;373:68–81. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61706-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanley JA, McNeil BJ. A method of comparing the areas under receiver operating characteristic curves derived from the same cases. Radiology. 1983;148:839–843. doi: 10.1148/radiology.148.3.6878708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harkness J, Pennell B, Villar A, Gebler N, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Bilgen I. Translation procedures and translation assessment in the World Mental Health Survey Initiative. The WHO World Mental Health Surveys: Global Perspectives on the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders. 2008:91–113. [Google Scholar]

- Haro JM, Arbabzadeh-Bouchez S, Brugha TS, de Girolamo G, Guyer ME, Jin R, Lepine J-P, Mazzi F, Reneses B, Vilagut G, Sampson NA, Kessler RC. Concordance of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview Version 3.0 (CIDI 3.0) with standardized clinical assessments in the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2006;15:167–180. doi: 10.1002/mpr.196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heeringa SG, Wells JE, Hubbard F, Mneimneh Z, Chiu WT, Sampson NA, Berglund PA. Sample designs and sampling procedures. In: Kessler RC, Üstün TB, editors. The WHO World Mental Health Surveys: Global Perspectives on the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, UK: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Institute S. SAS/IML 9.3 user’s guide. SAS Institute; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Jina R, Thomas LS. Health consequences of sexual violence against women. Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 2013;27:15–26. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2012.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karstoft K-I, Galatzer-Levy IR, Statnikov A, Li Z, Shalev AY. Bridging a translational gap: using machine learning to improve the prediction of PTSD. BMC Psychiatry. 2015;15:30. doi: 10.1186/s12888-015-0399-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kearns MC, Ressler KJ, Zatzick D, Rothbaum BO. Early interventions for PTSD: a review. Depression and Anxiety. 2012;29:833–842. doi: 10.1002/da.21997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, McLaughlin KA, Green JG, Gruber MJ, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Alhamzawi AO, Alonso J, Angermeyer M, Benjet C, Bromet E, Chatterji S, de Girolamo G, Demyttenaere K, Fayyad J, Florescu S, Gal G, Gureje O, Haro JM, Hu C-y, Karam EG, Kawakami N, Lee S, Lépine J-P, Ormel J, Posada-Villa J, Sagar R, Tsang A, Üstün TB, Vassilev S, Viana MC, Williams DR. Childhood adversities and adult psychopathology in the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2010;197:378–385. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.110.080499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Rose S, Koenen KC, Karam EG, Stang PE, Stein DJ, Heeringa SG, Hill ED, Liberzon I, McLaughlin KA. How well can post‐traumatic stress disorder be predicted from pre‐trauma risk factors? An exploratory study in the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. World Psychiatry. 2014;13:265–274. doi: 10.1002/wps.20150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Sonnega A, Bromet EJ, Hughes M, Nelson CB. Posttraumatic stress disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1995;52:1048–60. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950240066012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Ustun B. The World Mental Health (WMH) Survey Initiative version of the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2004;13:93–121. doi: 10.1002/mpr.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Ustun TB, editors. The WHO World Mental Health Surveys: Global Perspectives on the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders. Cambridge University Press; New York: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Knauper B, Cannell CF, Bruce ML, Kessler RC. Improving accuracy of major depression age-of-onset reports in the US National Comorbidity Survey. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 1999;8:39–48. [Google Scholar]

- Maikovich AK, Koenen KC, Jaffee SR. Posttraumatic stress symptoms and trajectories in child sexual abuse victims: An analysis of sex differences using the National Survey of Child and Adolescent Well-Being. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2009;37:727–737. doi: 10.1007/s10802-009-9300-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maniglio R. The impact of child sexual abuse on health: A systematic review of reviews. Clinical Psychology Review. 2009;29:647–657. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markman KD, Miller AK. Depression, control, and counterfactual thinking: Functional for whom? Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2006;25:210–227. [Google Scholar]

- Miller AK, Handley IM, Markman KD, Miller JH. Deconstructing self-blame following sexual assault: The critical roles of cognitive content and process. Violence Against Women. 2010;16:1120–1137. doi: 10.1177/1077801210382874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Möller AT, Bäckström T, Söndergaard HP, Helström L. Identifying risk factors for PTSD in women seeking medical help after rape. PloS One. 2014;9:e111136. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0111136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullen PE, Martin JL, Anderson JC, Romans SE, Herbison GP. Childhood sexual abuse and mental health in adult life. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1993;163:721–732. doi: 10.1192/bjp.163.6.721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullen PE, Martin JL, Anderson JC, Romans SE, Herbison GP. The long-term impact of the physical, emotional, and sexual abuse of children: A community study. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1996;20:7–21. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(95)00112-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Najdowski CJ, Ullman SE. PTSD symptoms and self‐rated recovery among adult sexual assault survivors: the effects of traumatic life events and psychosocial variables. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2009;33:43–53. [Google Scholar]

- Nishith P, Mechanic MB, Resick PA. Prior interpersonal trauma: The contribution to current PTSD symptoms in female rape victims. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2000;109:20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris FH, Murphy AD, Baker CK, Perilla JL, Rodriguez FG, Rodriguez JdJG. Epidemiology of trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder in Mexico. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2003;112:646. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.112.4.646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozer EJ, Best SR, Lipsey TL, Weiss DS. Predictors of posttraumatic stress disorder and symptoms in adults: a meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 2003;129:52. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.1.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roese NJ. Counterfactual thinking. Psychological Bulletin. 1997;121:133–148. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.121.1.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothbaum BO, Kearns MC, Price M, Malcoun E, Davis M, Ressler KJ, Lang D, Houry D. Early intervention may prevent the development of posttraumatic stress disorder: a randomized pilot civilian study with modified prolonged exposure. Biological Psychiatry. 2012;72:957–963. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott KM, de Jonge P, Stein DJ, Kessler RC, editors. The Cross-National Epidemiology of Mental Disorders: Facts and Figures from the World Mental Health Surveys. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: (Forthcoming) [Google Scholar]

- Simon GE, Von Korff M. Recall of psychiatric history in cross-sectional surveys: implications for epidemiological research. Epidemiological Reviews. 1995;17:221–227. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a036180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith GC, Seaman SR, Wood AM, Royston P, White IR. Correcting for optimistic prediction in small data sets. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2014;180:318–324. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwu140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takayanagi Y, Spira AP, Roth KB, Gallo JJ, Eaton WW, Mojtabai R. Accuracy of reports of lifetime mental and physical disorders: Results from the Baltimore Epidemiological Catchment Area Study. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71:273–280. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.3579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Temple JR, Weston R, Rodriguez BF, Marshall LL. Differing effects of partner and nonpartner sexual assault on women’s mental health. Violence Against Women. 2007;13:285–297. doi: 10.1177/1077801206297437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullman SE, Filipas HH. Predictors of PTSD symptom severity and social reactions in sexual assault victims. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2001;14:369–389. doi: 10.1023/A:1011125220522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullman SE, Filipas HH, Townsend SM, Starzynski LL. The role of victim-offender relationship in women’s sexual assault experiences. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2006;21:798–819. doi: 10.1177/0886260506288590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullman SE, Filipas HH, Townsend SM, Starzynski LL. Psychosocial correlates of PTSD symptom severity in sexual assault survivors. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2007;20:821–831. doi: 10.1002/jts.20290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widom CS, Morris S. Accuracy of adult recollections of childhood victimization: Part 2. childhood sexual abuse. Psychological Assessment. 1997;9:34–46. [Google Scholar]

- Williams LM. Recall of childhood trauma: a prospective study of women’s memories of childhood sexual abuse. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1994;62:1167–1176. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.62.6.1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolter K. Introduction to Variance Estimation. Springer Science & Business Media; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Zoellner LA, Foa EB, Brigidi BD, Przeworski A. Are trauma victims susceptible to" false memories?". Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2000;109:517. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.109.3.517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou KH, O’Malley AJ, Mauri L. Receiver-operating characteristic analysis for evaluating diagnostic tests and predictive models. Circulation. 2007;115:654–657. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.594929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]