Abstract

We use molecular simulations to probe local viscoelasticity of an entangled polymer melt by tracking the motion of embedded non-sticky nanoparticles (NPs). As in conventional microrheology, the generalized Stokes-Einstein relation is employed to extract an effective stress relaxation function GGSE(t) from the mean square displacement of NPs. GGSE(t) for different NP diameters d are compared with the stress relaxation function G(t) of a pure polymer melt. The deviation of GGSE(t) from G(t) reflects the incomplete coupling between NPs and the dynamic modes of the melt. For linear polymers, a plateau in GGSE(t) emerges as d exceeds the entanglement mesh size a and approaches the entanglement plateau in G(t) for a pure melt with increasing d. For ring polymers, as d increases towards the spanning size R of ring polymers, GGSE(t) approaches G(t) of ring melt with no entanglement plateau.

Microrheology is a powerful technique to measure the viscoelasticity of a medium through tracking the motion of embedded probe particles[1]. The particles are often much larger than any structural length scale of the medium, and their motion is coupled to the bulk viscoelasticity [2–4]. In this Letter, we use molecular simulations to explore the extension of microrheology to nanorheology, in which nanoparticles (NPs) smaller than or comparable to the structural length scales of the medium are used instead of micron-size beads. Specifically, we study NPs in a melt of entangled polymers. A key question is how viscoelastic modes of the melt affect the NP motion and how it is related to the diameter d of NPs and the structural length scales of the polymer melt, such as the average spacing a between polymer entanglements and the average size R of polymers.

Diffusion of NPs in a polymer melt is an essential process during the fabrication of polymer nanocomposites, a prominent class of hybrid materials [5, 6]. Experiments [7–10] and simulations [6, 11–13] have demonstrated that NP diffusion in a melt of entangled linear polymers depends on the relation between d and a. The mobility of NPs with d < a is higher than the prediction of the Stokes-Einstein relation [12, 13]. Scaling theory [14] argues that these NPs are coupled only to the unentangled dynamics of local chain segments with sizes up to ≈ d. The mobility of NPs with d > a is suppressed due to the confinement of the entanglement network [12, 13]. While sufficiently large NPs are trapped by the network and cannot freely diffuse until the terminal relaxation of the network, NPs with d moderately larger than a can overcome the entanglement confinement through the hopping diffusion mechanism [15].

Recently, NP diffusion in an entangled melt of non-concatenated ring polymers has also been studied using simulations and scaling theory [13]. The motion of NPs with d > a in ring polymers is not as strongly suppressed as in linear polymers of the same lengths, as there is no entanglement network in a ring polymer melt. The comparison of NP diffusion in entangled linear chains and non-concatenated rings exemplifies the effects of polymer architecture on the dynamical coupling between NPs and polymer melts.

One measure of viscoelasticity is the stress relaxation modulus G(t) as a function of time t. In microrheology, G(t) is linked to the mean squared displacement (MSD) of tracer particles 〈Δr2(t)〉 through the generalized Stokes-Einstein (GSE) relation [1, 2]. In the domain of Laplace frequency s, the GSE relation is

| (1) |

in which G̃(s) and are the unilateral Laplace transforms of G(t) and 〈Δr2(t)〉. f = 3 or 2 depending on whether the particle-medium boundaries are stick or slip.

We employ the GSE relation to convert the simulation data of NP MSD in a polymer melt to an effective stress relaxation function GGSE(t). The results of GGSE(t) for NPs with different diameters d are compared with the stress relaxation function of the corresponding pure polymer melt GGK(t), which is obtained using the Green-Kubo formula. This comparison is performed for NPs in entangled linear polymers and non-concatenated ring polymers. Through this comparison, we examine the coupling between NP motion and the bulk melt viscoelasticity and the dependence of the coupling on d.

The models of polymers and NPs are similar to those in previous molecular dynamics (MD) simulations [6, 12, 13, 16–19]. Lennard-Jones units σ, m and ε are used for length, mass and energy, respectively. For the entangled linear polymer melt, the number of monomers per entanglement strand Ne ≈ 28 [20, 21], the average spacing between entanglements a ≈ 5σ [21], and the entanglement time τe ≈ 4000τ [22] with . The number of monomers in a polymer is N = 800 for both linear chains and rings. NP diameter d ranges from 3σ < a to 15σ ≈ 3a, and the volume fraction of NPs ϕNP ≈ 10%. Previous simulations [6] have shown that the viscosity of a NP linear polymer composite is reduced with respected to that of the corresponding pure polymer melt if d < a, almost unchanged if d ≈ a, while enhanced if d > a. The relative change of composite viscosity with respect to pure melt viscosity can be up to ≈ 25% at ϕNP ≈ 10%. For NP-ring systems, our simulation results show that the composite viscosity at ϕNP ≈ 10% also changes by up to ≈ 25% depending on d. All samples were equilibrated at pressure P = 0 and temperature T = 10ε/kB. Subsequent simulations were run at constant volume V for up to 108τ. MSDs 〈Δr2(t)〉 of NPs in the simulations have been reported in a previous paper [13]. Additional simulation details are presented in Supplemental Material (SM).

The stress relaxation modulus for a pure polymer melt is calculated using the Green-Kubo formula

| (2) |

where is the pre-averaged stress [23], and i and j are Cartesian indices with i ≠ j. GGK(t) is computed as the average of with ij = xy, xz and yz.

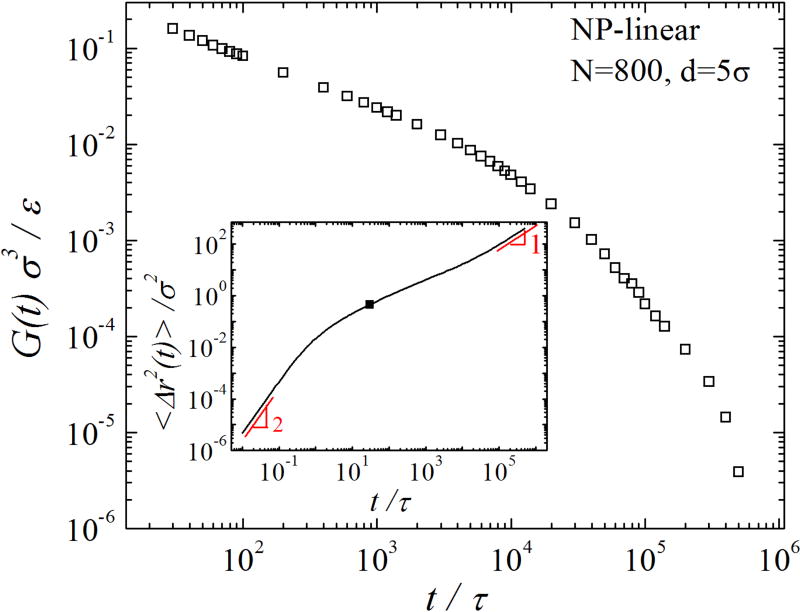

We use the GSE relation (Eq. 1) to convert 〈Δr2(t)〉 to GGSE(t). The conversion is done using the method developed by Mason [24]. One example of the conversion is given in Fig. 1. The early-time part of 〈Δr2(t)〉 is excluded from the conversion, as the inertialess GSE relation (Eq. 1) is not applicable to the regime of ballistic motion and the subsequent crossover to thermal motion [25]. As shown in the inset of Fig. 1, a typical MSD curve starts with a ballistic regime where the log-log slope α = d log 〈Δr2(t)〉 /d log t = 2, then it crosses over to a sub-diffusive regime with α < 1, and eventually enters the Fickian regime with α = 1. We estimate that the crossover from ballistic to thermal motion ends at the inflection point of α vs. log t. The black square in the inset of Fig. 1 indicates the end of the crossover at τ* ≈ 30τ for d = 5σ. A detailed discussion of this criterion for τ* can be found in SM. Only 〈Δr2(t)〉 for t > τ* is used in the conversion to GGSE(t).

FIG. 1.

GGSE(t) (open squares) for d = 5σ in linear polymers with N = 800. The corresponding 〈Δr2(t)〉 is shown in the inset (see black line). The log-log slope α = 2 for the ballistic regime and α = 1 for the Fickian regime are indicated. The estimated end of the crossover between ballistic and thermal motion is indicated by the black square.

Throughout the paper, we use f = 2 for the GSE relation, which corresponds to slip NP-polymer boundaries. The slip boundary results from the slip length Ls(t) being larger than d for t > τ*. Previous simulations [26] have demonstrated that Ls for a bulk polymer melt scales linearly with the melt viscosity η. To estimate Ls(t) in the present simulations, a similar scaling relation Ls(t) ≈ b [η (t)/η0], in which monomer size b ≈ σ and monomeric viscosity η0 ≈ τkBT/σ3, is used. In SM, we estimate η(t) from and demonstrate that the condition Ls(t) > Ls(τ*) > d for t > τ* is satisfied in all simulated NP-polymer systems (see Fig. S1), justifying the slip NP-polymer boundaries.

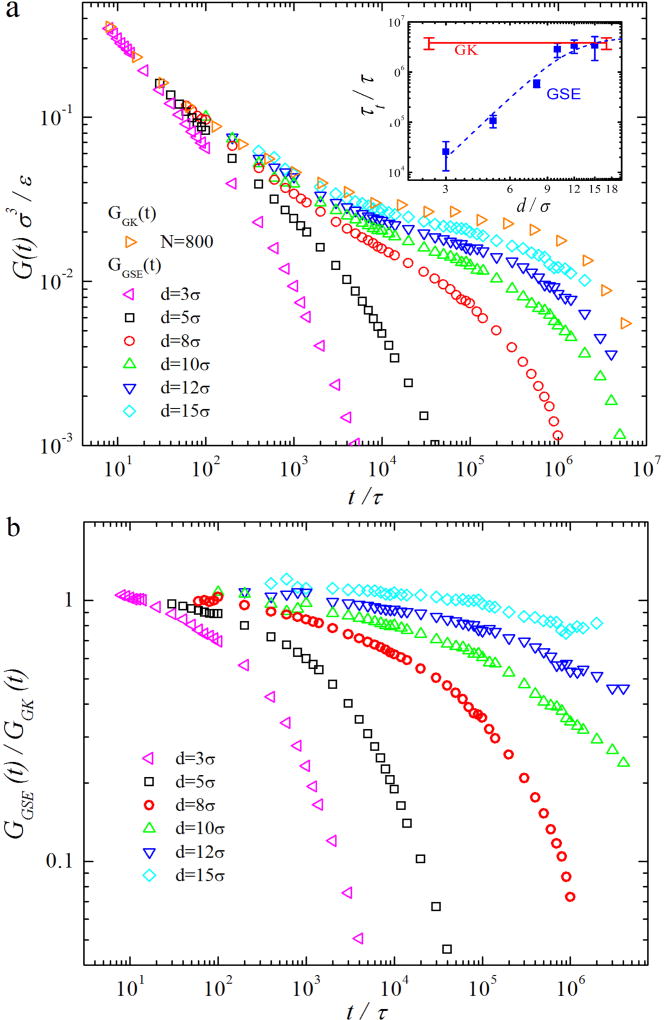

Results of GGK(t) and GGSE(t) for linear polymers are shown in Fig. 2(a). For GGK(t), there is first a power-law decay, then the development of entanglement plateau, and finally the regime of terminal relaxation. At t ≈ 6.5 × 104τ with the smallest log-log slope |−d log G(t)/d log t| ≈ 0.07, G(t) ≈ 2.6×10−2ε/ σ3, which is close to the theoretical prediction [27] of the entanglement plateau Ge ≈ 4ρkBT/5Ne ≈ 2.5 × 10−2ε/σ3 with melt density ρ = 0.89σ−3 and Ne ≈ 28. The power-law decrease can be described using the Rouse modes of short unentangled sections of polymer, and is predicted to scale as G(t) ~ t−1/2 [28]. The entanglement plateau has been successfully understood based on the phenomenological tube model [27, 28], in which entangled chains are confined in their respective tubes with average diameter ≈ a. For Z = N/Ne ≈ 30 as in the present simulations, dynamic processes such as Rouse-type relaxation along the tube, tube length fluctuation and constraint release contribute to the partial stress relaxation prior to the terminal relaxation [29], and results in the deviation of the plateau from a horizontal line. To compare the simulation data of GGK(t) with theories for polymer stress relaxation, we fit GGK(t) to the theoretical expression proposed by Likhtman and McLeish [29]. The details of the fitting are presented in SM. The parameters of the best fit are N/Ne = Z = 33 ± 1, Ne = 24 ± 1, τe = (1.9 ± 0.1) × 103τ, and Ge = (0.030 ± 0.002) ε/σ3.

FIG. 2.

(a) GGSE(t) for NPs with different d in linear polymers with N = 800 compared to GGK(t) for the pure linear polymer melt. Inset shows τt vs. d for GGSE(t) (blue squares) and τt for GGK(t) (red line) with error bars. The dashed blue line indicates the best fit to the scaling theory prediction [15]. (b) The ratio GGSE(t)/GGK(t) for the same systems as in (a).

The melt viscoelasticity that affects the thermal NP motion in linear chains depends on d, as demonstrated in the d-dependence of GGSE(t) in Fig. 2(a). For d = 3σ < a and d = 5σ ≈ a, there is no plateau in GGSE(t). The dynamic modes of local chain segments that control the motion of NPs with d ≤ a contribute to GGSE(t). The degree of coupling between NP motion and these dynamic modes is quantified by the ratio GGSE(t)/GGK(t) (see Fig. 2(b)). As t increases, GGSE(t)/GGK(t) drops below 1, indicating reduced degree of coupling between NP motion and the corresponding dynamic modes. The decrease of GGSE(t)/GGK(t) is less rapid for d = 5σ than for d = 3σ, indicating stronger coupling between NP motion and the melt viscoelasticity with increasing d. Scaling theory [14] predicts that the motion of a NP with d < a is coupled to the Rouse modes of chain segments with sizes up to d. Motivated by the theory, we compare GGSE(t) for d ≤ a with

| (3) |

which is the sum of the modes with Rouse time τR and mode indices pc ≤ p ≤ N. N = 800 and N/pc is the number of monomers in the largest chain segment that affects NP motion. The comparison is presented in SM.

As d exceeds a, a plateau regime emerges as indicated by the inflection in the log-log plot of GGSE(t). The presence of a plateau means that NPs with d > a are affected by the confinement of the entanglement network. The confinement is stronger for larger d, and the coupling between NP motion and melt viscoelasticity is enhanced with increasing d, as shown in Fig. 2(b). However, for the largest d = 15σ, the coupling is still not complete with GGSE(t)/GGK(t) < 1. We fit GGSE(t) for d > a to the Likhtman-McLeish expression [29] (eq. S1). As shown in SM, the best-fit value of the number of entanglements per chain Z increases with d, but stays below Z = 33 for the bulk melt. The reason of the partial coupling for 8σ ≤ d ≤ 15σ has been attributed to the hopping diffusion [13, 15] for d moderately larger than a.

The terminal regime of G(t) in Fig. 2(a) is fit to an exponential decay with G(t) ~ exp (−t/τt), where τt is the characteristic decay time. While τt characterizes terminal stress relaxation in the pure melt, τt for GGSE(t) is essentially the terminal diffusion time of NP motion. The results of τt for GGSE(t) and GGK(t) are shown in the inset of Fig. 2(a). τt for GGSE(t) increases with d and then saturates around τt for GGK(t) as d exceeds 10σ. Despite the saturation of τt, GGSE(t) is still below GGK(t) for d ≥ 10σ. This suggests that NPs with d ≥ 10σ are coupled to the melt dynamics up to the longest terminal relaxation mode, though the coupling is not complete. Scaling theory [15] predicts that τt ~ d4 for d < a, τt ~ exp (d/a) for hopping diffusion, and finally τt saturates at the terminal relaxation time of the melt in the large d limit. The best fit of the d-dependence of τt to an analytical function motivated by the theory is shown by the dashed line in the inset of Fig. 2a. Details about the fitting and the terminal regimes are in SM.

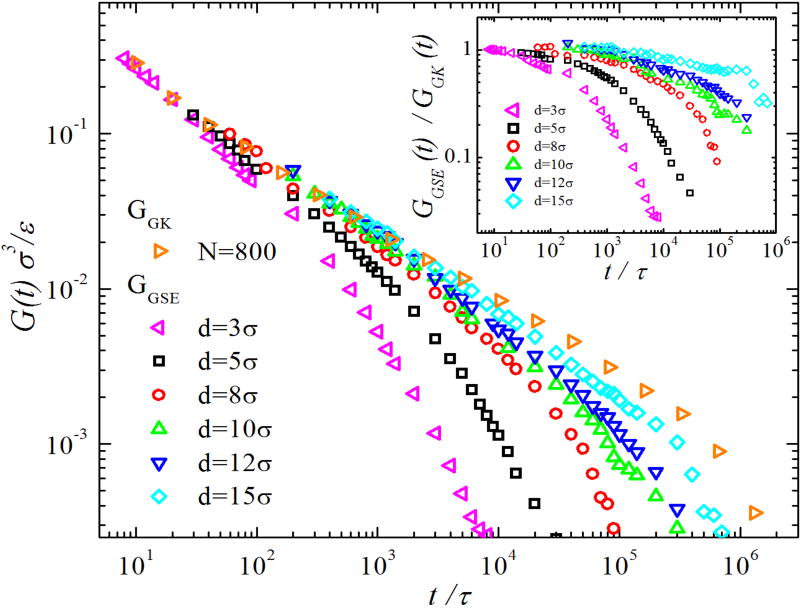

Results of GGK(t) and GGSE(t) for ring polymers are shown in Fig. 3. Unlike GGK(t) for linear polymers, GGK(t) for ring polymers has no entanglement plateau, as there is no long-lived entanglement network [30]. The melt viscoelasticity that determines the diffusion of NPs in rings depends on d, as demonstrated by the d-dependence of GGSE(t) in Fig. 3. As d increases, GGSE(t) for NPs in rings approaches GGK(t) for pure rings, and the ratio GGSE(t)/GGK(t) deviates from 1 less rapidly with increasing t (see the inset of Fig. 3). These results show that NP motion is coupled to the melt viscoelasticity over a wider spectrum of relaxation modes with increasing d, and the coupling is stronger for larger d. Scaling theory [13] predicts that NP motion is coupled to the dynamics of ring sections with sizes up to d, which is smaller than the size of an entire ring polymer.

FIG. 3.

GGSE(t) for NPs with different d in ring polymers with N = 800 compared to GGK(t) for the pure linear polymer melt. Inset shows the ratio GGSE(t)/GGK(t).

The motion of NPs with sufficiently large d is expected to be completely coupled to the terminal relaxation of the polymer melt, and the corresponding GGSE(t) excluding the early-time part affected by NP inertia is expected to agree with GGK(t). Previously, based on the examination of the d-dependence of the diffusion coefficient D for the same simulations [13], it is estimated that the Stokes-Einstein (SE) relation D = kBT/2πηd, where η is the melt viscosity, is recovered for d > dc ≈ 20σ in NP-linear systems (N = 800), and for d > dc ≈ 30σ in NP-ring systems (N = 800). Since the recovery of SE relation corresponds to a complete coupling between Fickian NP motion and the melt viscoelasticity, we expect that the threshold NP size dc for the agreement between GGSE(t) and GGK(t) is also 20σ and 30σ for NP-linear and NP-ring systems (N = 800), respectively.

The important length scale that determines the agreement between GGSE(t) and GGK(t) differs for NPs in linear and ring polymers. d is compared with the entanglement spacing a to determine whether GGSE(t) and GGK(t) agrees for NPs in linear chains. According to the hopping diffusion model [15], the hopping probability decreases as ~ exp (−d/a). Hopping diffusion is suppressed for d sufficiently larger than a, and therefore the NP motion is completely coupled to the relaxation of the entanglement network even for d smaller than the size of linear chains. In the present simulation, the estimated dc ≈ 4a for the complete coupling between NPs and linear polymers. By contrast, d is compared with the average spanning size 〈R2〉1/2 of ring polymers to determine the agreement between GGSE(t) and GGK(t). As there is no long-lived entanglement network to confine NPs in ring polymers, NP motion is increasingly coupled to ring dynamics at longer time scales and larger length scales as d increases towards 〈R2〉1/2. In the present simulations, 〈R2〉1/2 ≈ 15σ, and the estimated dc ≈ 2 〈R2〉1/2 for the coupling between NPs and the entire relaxation dynamics of rings. dc ≈ 2 〈R2〉1/2 results from the broad distribution of R around the average 〈R2〉1/2. Our analysis in SM shows that 33% of all R are larger than 〈R2〉1/2, while almost all (99%) R are smaller than d = 2 〈R2〉1/2. This explains why NPs with d = 15σ are not completely coupled to the entire ring dynamics, whereas NPs with d > 2 〈R2〉1/2 are anticipated to be almost completely coupled.

Another important length scale for NP-polymer coupling is the slip length Ls at NP-polymer boundaries. Present simulations correspond to slip boundary condition with Ls > d. If d > Ls, the boundary condition becomes stick. There would be a scaling regime where NP motion is fully coupled to all relaxation modes of polymers but with stick NP-polymer boundaries. Fig. S9 shows the scaling theory prediction for such a regime depending on d and polymer size. The existence of two length scales dc and Ls suggests a two-stage coupling of NPs to entire polymer dynamics with increasing d. NPs are first coupled to all relaxation modes with slip NP-polymer boundaries as d exceeds dc. Subsequently, the boundary conditions change from slip to stick as d further increases above Ls.

To summarize, on the basis of molecular simulations, we compare the stress relaxation moduli GGSE(t) converted from NP MSD through the generalized Stokes-Einstein relation and GGK(t) for pure entangled polymer melts calculated using the Green-Kubo formula. The deviation of GGSE(t) from GGK(t) results from the incomplete coupling of NP motion to the relaxation modes of polymer melt. The threshold NP size dc for the agreement between GGSE(t) and GGK(t) is compared to the entanglement mesh size for NP-linear systems whereas to the polymer size for NP-ring systems in which there are no entanglement networks. Our simulations correspond to slip NP-polymer boundaries, but a change from slip to stick boundaries as d increases above the slip length Ls is anticipated. NP-polymer coupling with increasing d is proposed to be a two-stage process depending on dc and Ls. Our study should help extend the well-established micro-rheology procedures to nanorheology, which would advance the study of local viscoelasticity that controls the dynamics of nano-scale objects in a viscoelastic medium, such as NPs in polymer nanocomposites and NP-based drug carriers in living cells.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

M. R. acknowledges financial support from the National Science Foundation under Grants DMR-1309892, DMR-1436201, and DMR-1121107, the National Institutes of Health under Grants P01-HL108808 and 1UH2HL123645, and the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation. This research used resources at the National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center, which is supported by the Office of Science of the United States Department of Energy under Contract No. DE-AC02-05CH11231. This work was performed, in part, at the Center for Integrated Nanotechnologies, an Office of Science User Facility operated for the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science. Sandia National Laboratories is a multimission laboratory managed and operated by National Technology and Engineering Solutions of Sandia, LLC., a wholly owned subsidiary of Honeywell International, Inc., for the U.S. Department of Energys National Nuclear Security Administration under contract DE-NA-0003525.

References

- 1.Squires TM, Mason TG. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 2010;42:413. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mason TG, Weitz DA. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1995;74:1250. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.74.1250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dasgupta BR, Tee SY, Crocker JC, Frisken BJ, Weitz DA. Phys. Rev. E. 2002;65:051505. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.65.051505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van Zanten JH, Amin S, Abdala AA. Macromolecules. 2004;37:3874. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Balazs AC, Emrick T, Russell TP. Science. 2006;314:1107. doi: 10.1126/science.1130557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kalathi JT, Grest GS, Kumar SK. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2012;109:198301. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.109.198301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Szymanski J, Patkowski A, Wilk A, Garstecki P, Holyst R. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2006;110:25593. doi: 10.1021/jp0666784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guo H, Bourret G, Lennox RB, Sutton M, Harden JL, Leheny RL. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2012;109:055901. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.109.055901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grabowski CA, Mukhopadhyay A. Macromolecules. 2014;47:7238. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mangal R, Srivastava S, Narayanan S, Archer LA. Macromolecules. 2016;32:596. doi: 10.1021/acs.langmuir.5b03311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu J, Cao D, Zhang L. J. Phys. Chem. 2008;112:6653. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kalathi JT, Yamamoto U, Schweizer KS, Grest GS, Kumar SK. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2014;112:108301. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.112.108301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ge T, Kalathi JT, Halverson JD, Grest GS, Rubinstein M. Macromolecules. 2017;50:1749. doi: 10.1021/acs.macromol.6b02632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cai LH, Panyukov S, Rubinstein M. Macromolecules. 2011;44:7853. doi: 10.1021/ma201583q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cai LH, Panyukov S, Rubinstein M. Macromolecules. 2014;48:847. doi: 10.1021/ma501608x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Halverson JD, Lee WB, Grest GS, Grosberg YA, Kremer K. J. Chem. Phys. 2011;134:204904. doi: 10.1063/1.3587137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Halverson JD, Lee WB, Grest GS, Grosberg YA, Kremer K. J. Chem. Phys. 2011;134:204905. doi: 10.1063/1.3587138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kremer K, Grest GS. J. Chem. Phys. 1990;92:5057. [Google Scholar]

- 19.in’t Veld PJ, Plimpton SJ, Grest GS. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2008;179:320. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Everaers R, Sukumaran SK, Grest GS, Svaneborg C, Sivasubramanian A, Kremer K. Science. 2004;303:823. doi: 10.1126/science.1091215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hsu H-P, Kremer K. J. Chem. Phys. 2016;144:154907. doi: 10.1063/1.4946033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ge T, Robbins MO, Perahia D, Grest GS. Phys. Rev. E. 2014;90:012602. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.90.012602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee WB, Kremer K. Macromolecules. 2009;42:6270. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mason TG. Rheol Acta. 2000;39:371. [Google Scholar]

- 25.The effects of the inertia of both probe particle and viscoelastic medium on particle-based passive rheology have been examined in recent theoretical [31] and computational [32, 33] work.

- 26.Priezjev NV, Troian SM. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2004;92:018302. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.92.018302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Doi M, Edwards SF. The Theory of Polymer Dynamics. Clarendon Press; Oxford: 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rubinstein M, Colby RH. Polymer Physics. Oxford: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Likhtman AE, McLeish TCB. Macromolecules. 2002;35:6332. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kapnistos M, Lang M, Vlassopoulos D, Pyckhout-Hintzen W, Richter D, Cho D, Chang T, Rubin-stein M. Nat. Mater. 2008;7:997. doi: 10.1038/nmat2292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Indei T, Schieber JD, Córdoba A, Pilyugina E. Phys. Rev. E. 2012;85:021504. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.85.021504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Karim M, Kohale SC, Indei T, Schieber JD, Khare R. Phys. Rev. E. 2012;86:051501. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.86.051501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Karim M, Indei T, Schieber JD, Khare R. Phys. Rev. E. 2016;93:012501. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.93.012501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.