Abstract

Background

The currently available chemotherapeutic regimens do not use a specifically designed drug delivery system. The objective of this study was to compare outcome measures, adverse effects, and cost of FOLFOX4 and FOLFIRINOX treatments in rectal cancer patients.

Material/Methods

We enrolled patients who, after surgery, did not undergo chemotherapy or radiotherapy (Control group); were administered 200 mg/m2 folinic acid, 400 mg/m2 fluorouracil, and 85 mg/m2 oxaliplatin (FFO group); or were administered 400 mg/m2 folinic acid, 400 mg/m2 fluorouracil, 180 mg/m2 irinotecan, and 85 mg/m2 oxaliplatin (FFIO group). We recorded tumor and nodal staging, carbohydrate antigen 19-9, serum carcinoembryonic antigen, total cost of treatment, disease recurrence, overall survival, and adverse effects. We used the 2-tailed paired t test following Turkey post hoc test for adverse effects, recurrence analysis, and cost of treatment at 95% of confidence level.

Results

Surgery (p=0.00089), FOLFOX4 (p=0.000167), and FOLFIRINOX (p=0.00013) improved disease-free conditions. Only surgery failed to maintain carbohydrate antigen and carcinoembryonic antigen 19-9 levels. The cost of chemotherapeutic treatments was in the order of FFIO group > FFO group > Control group. Non-fatal treatment-emergent adverse effects were due to chemotherapeutic drugs. However, fatal chemotherapeutic treatment-emergent adverse effects were observed only in the FFIO group. Overall survival, irrespective of cancerous condition, was higher in the FFO group.

Conclusions

FOLFIRINOX had less total cancer recurrence than FOLFOX4. However, FOLFIRINOX had more fatal treatment-emergent adverse effects and excessive cost of treatment than FOLFOX4 regimen.

MeSH Keywords: Antigens, Tumor-Associated, Carbohydrate; Carcinoembryonic Antigen; Neoplasm Recurrence, Local; Neoplasm Staging; Rectal Neoplasms

Background

The Central Research Ethics Committee for Oncology Society of China has concluded that rectal cancer is a major fatal condition in PR China. In 2011, there were more than 50 000 new patients with various stages of rectal cancer [1].

Rectal cancers are found in lymph nodes and rectal walls and are difficult to cure [2]. The current option for treatment is total mesorectal excision or blunt rectal surgical techniques with preoperative or postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy following radiotherapy. Historical studies suggest that adjunct chemotherapy reduces local recurrence [3].

The current standard chemotherapy in rectal cancer is 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) [4]. Folinic acid (FA) modulates the action of 5-FU and increased survival of patients [5]. Moreover, oxaliplatin (OP) possesses synergistic action with 5-FU and FA [4]. Irinotecan (IT) is a topoisomerase I inhibitor with augmented efficacy with 5-FU in rectal cancer [6].

There are several regimens used as chemotherapy in rectal cancer, such as FOLFOX (FA, 5-FU, and OP), FOLFIRI (FA, 5-FU, and IT) [7], and FOLFIRINOX (FA, 5-FU, IT, and OP) [8]. There are also 2 regimens for FOLFOX: FOLFOX4 and FOLFOX6. In FOLFOX4, drugs are administered as 12 cycles and cycle/2-weeks [4]. In FOLFOX6, the drugs are administered as 12 cycles and cycle/weeks [9]. These regimens are not targeted, self-engineered, or tailor-made drug delivery systems. They have lethal effects on humans and an increased mortality rate [10]. However, use of chemoradiotherapy after surgery has an effect on local recurrences [11] and overall survival [12] of the patient. Therefore, it is necessary to know the advantages and disadvantages of each chemotherapy regimen.

The objective of this study was to compare outcome measures, treatment-emergent adverse effects, and cost of treatment of FOLFOX4 and FOLFIRINOX regimens in rectal cancer patients undergoing cancer treatment.

Material and Methods

Materials

Hematoxylin, eosin, normal saline, and formalin were purchased from Wuhan Heng Heda Pharm Co., Ltd. Hubei, China. FA, 5-FU, OP, and IT were purchased from Shandong Sino Pharmaceutical Technology Co., Ltd., Shandong, China, Wuhan Honor Bio-Pharm Co., Ltd., Wuhan, China, Shanghai Yijing Industrial Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China, and Qingdao Fraken International Trading Co., Ltd., Shandong, China, respectively.

Ethical statement

The Research Ethics Committee For Oncology of Huzhou Central Hospital, China, approved the experimental protocol, and the ethics guidelines for oncology research on human subjects in accordance with the Chinese law were followed [13].

Diagnosis and surgical resection

Patients suspected to have rectal cancer underwent rectal colonoscopy [14], CT-scan, and high-resolution rectal MRI [15]. During the diagnosis process, patients who were found to have rectal tumors and who required surgical resection were recommended for surgery. After getting written informed consent from the patients or their relatives, the patients underwent rectal surgery [16].

Detection of stage of cancer

Analysis of KRAS gene mutation

Tumors removed by surgical resection was frozen in a Dwc-196 liquid nitrogen refrigeration low-temperature chamber (HST Group Co., Ltd., Shandong, China). The DNA from tumors was extracted using a blood and tissue DNA extraction mini kit (Guangzhou Changyu Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Guangzhou, China), then polymerase chain reaction and exon 1 and 3 were sequenced. Direct sequencing was carried out using the CA-40212E kit (Changsha Aube Didactic Equipment Co., Ltd., Hunan, China) [6].

Histopathology

We collected a 4-mm sample of tissue from the surgically resected tumor. The sample was fixed in 10% formalin. The specimen was stained with hematoxylin and eosin and observed under a binocular stereo microscope with top and bottom light illumination (M633c, Chongqing Dontop Optics Co., Ltd., Chongqing, China) under 10× and 45× [15].

In the above pathological and clinical data, biopsies and autopsies were considered for analysis. By using the TNM rectal carcinoma staging system, the stage of cancer was detected at baseline (Table 1) [17].

Table 1.

Rectal carcinoma staging as per TNM system.

| T: Tumor | N: Nodes | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| T0 | No evidence of primary tumor | NO | No evidence of node |

| T1 | Site specific tumor (small) | N1 | Site specific tumor (small) |

| T2 | Site specific tumor (medium) | N2 | Site specific tumor (medium) |

| T3 | Site specific tumor (large) | N3 | Site specific tumor (large) |

| T4a | tumor infiltrates the serosa | ||

| T4b | Site specific tumor adjacent to tissue | ||

Aim

Primary aim

Clinicopathology. The primary aim of the study was the clinicopathological response of the patients’ body after chemotherapeutic treatment.

Secondary aim

Treatment-emergent adverse effects. A secondary aim of the study was overall survival, cancer-free conditions, and toxicities.

Inclusion criteria

We included rectal cancer patients with advanced adenocarcinoma of the rectum who were admitted to the Department of Anorectal Surgery and the Department of Hepatobiliary Surgery, Huzhou Central Hospital, Huzhou, China during January 2008 to March 2017, and who were age 18–70 years, had a 0–8 cm distance margin of the tumor from the anal verge, and had no prior chemotherapy exposure. All subjects were over 18 years of age and gave informed consent for chemotherapeutic treatment and publication in educational magazines, journals, textbooks in any form or medium (including all forms of electronic publication or distribution) anywhere in the world without time limit. Data were available from patients’ DCOIM files of Huzhou Central Hospital, Zhejiang, China.

Exclusion criteria

We excluded patients who had impaired renal function, liver function, or and inadequate blood cell counts were excluded from the study as were patients who refused MRI or surgery, or who had incomplete histopathology and KRAS gene mutation data.

Chemotherapy treatment and sample size

The demographical parameters of the patients involved in the study are reported in Table 2. After surgery, those patients who were refused and were not administered chemotherapy and radiotherapy after surgery were included in the control group. Those patients who received FOLFOX4 chemotherapeutic regimen (200 mg/m2 FA, 400 mg/m2 5-FU, and 85 mg/m2 OP) as 2 h infusion for 12 cycles and cycle/2weeks following radiotherapy after surgery [4] were included in the FFO group. Those patients who received FOLFIRINOX chemotherapeutic regimen (400 mg/m2 FA, 400 mg/m2 5-FU, 180 mg/m2 IT, and 85 mg/m2 OP) as 2 h infusion for 25 cycles and cycle/2 weeks following radiotherapy [18] were included in the FFIO group.

Table 2.

Anatomical characteristics of enrolled patients.

| Characteristics | Group | Control | FFO | FFIO | p Value for variations among the groups |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample size | 115 | 115 | 115 | ||

| Surgical resection | Abdominal-perianal | 79 (69) | 77 (67) | 71 (62) | 0.5142 |

| Anterior | 36 (31) | 38 (33) | 44 (38) | ||

| Time from surgery to treatment | 20–40 days | 66 (57) | 48 (42) | 50 (43) | 0.1148 |

| ≥41 days | 49 (43) | 67 (58) | 65 (57) | ||

| Gender | Male | 76 (66) | 72 (63) | 69 (60) | 0.6337 |

| Female | 39 (34) | 43 (37) | 46 (40) | ||

| Age (years) (mean ±SD) | 57.95±2.61 | 58.52±2.01 | 56.42±2.69 | 0.1283 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) (mean ±SD) | 24.12±1.12 | 25.22±1.45 | 23.56±1.35 | 0.4562 | |

| Distance margin of tumor from anal verge (cm) | 0–5 | 83 (72) | 67 (58) | 65 (57) | 0.1059 |

| 5–8 | 32 (28) | 48 (42) | 50 (43) | ||

| Tumor differentiation | Poorly differentiated | 8 (7) | 9 (8) | 11 (10) | 0.4904 |

| Moderately differentiated | 88 (77) | 83 (72) | 87 (76) | ||

| Well differentiated | 19 (16) | 23 (20) | 17 (14) |

Data were represented as Number (Percentage). No changes for anatomical and cancerous characteristics of enrolled patients between groups.

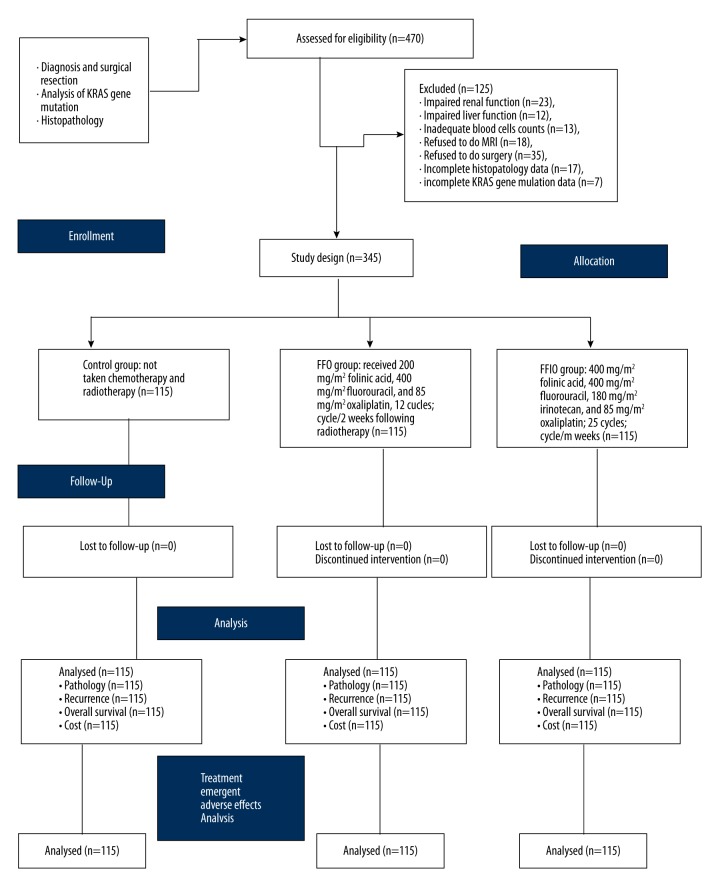

For optimum statistical analysis, the sample size was 150 for each group. The flow chart of chemotherapeutic treatment is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Chemotherapeutic treatment arms of the clinical experimental study.

Pathological response

In rectal cancer, carbohydrate antigen 19-9 and serum carcinoembryonic antigen are tumor markers [19]. A blood sample of patients was collected after each cycle of chemotherapy. Carbohydrate antigen 19-9 and serum carcinoembryonic antigen in blood samples were evaluated by a pathologist who was blind to the chemotherapeutic treatments [20].

Cost of treatment

The total cost of treatment included costs related to diagnosis before surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, follow-up visits, and diagnosis in follow-up. However, the charges did not include the treatment of adverse effects and related hospitalization. Travel costs from home to hospital were not counted in the cost of treatment. A bootstrap procedure was used for evaluating the cost of treatment in all groups [21].

Treatment-emergent adverse effects

Approval from the Central Research Ethics Committee for the Oncology Society of China was obtained for evaluation and analysis of treatment-emergent adverse effects. Fatal and non-fatal and treatment-emergent adverse effects of chemotherapy such as neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, nausea, vomiting, stomatitis, diarrhea, hepatic diseases, fatigue, peripheral neurotoxicity, skin rashes, and pulmonary complications were evaluated during follow-up. Neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, pulmonary complications, and hepatic diseases were evaluated from a blood sample collected and using the 3-Part Blood Cell Counter (Henan Forever Medical Co., Ltd. Henan, China). Peripheral neurotoxicity was evaluated by an expert neurologist available in the hospital. Nausea, vomiting, skin rashes, stomatitis, diarrhea, and fatigue were assessed by a questionnaire administered to patients [4].

Cancer recurrence

After completion of chemotherapy, all radiological and pathological data were evaluated every 6 months. The liver is the most prominent site for metastasis in rectal cancer [5]. Recurrence was considered if patients had a positive rectal, liver, pulmonary, or colon tumor. To check the recurrence, rectal biopsy or autopsy were carried out every 6 months [13]. The response of tumor recurrence to chemotherapy was evaluated by RECIST (Response Evaluation Criteria In Solid Tumors) guidelines [22].

Overall survival

Overall survival irrespective of cancer-free conditions was also evaluated after completion of treatments for each group during follow-up [7].

Statistical analysis

Ordinary ANOVA was performed for tumor staging, nodal-staging, and pathological responses before surgery among the groups. Two-tailed t tests (considering β=0.1 and α=0.05) [23] following Turkey post hoc test (considering q>3.331 for significant) were used for anatomical characteristics of enrolled patients, fatal and non-fatal chemotherapeutic treatment-emergent adverse effects after complication of all cycles, total cancer recurrence analysis, only rectal cancer recurrence analysis, and cost of treatment. Wilcoxon rank sum test (considering q>3.331 for significant) was performed for tumor and nodal staging and clinicopathological responses between before surgery and after completion of total treatment(s) [24]. All statistical tests were performed using InstatGraphPad software (GraphPad Software, Inc., CA). The results of parameters were considered significant at 99% confidence level for anatomical characteristics, tumor staging, nodal staging, and pathological responses of enrolled patients before surgery. However, the results of parameters were considered significant at 95% confidence level for fatal and non-fatal chemotherapeutic treatment-emergent adverse effects, tumor staging, cost of treatment, overall survival irrespective of cancer-free condition, total cancer, and only rectal recurrence analysis after treatment.

Results

There were no differences between groups in anatomical or cancerous characteristics of enrolled patients at baseline (p≥0.05 for all characteristics).

There was no difference in tumor staging (p=0.1248) and nodal staging (p=0.2516) among the group before surgery. After surgery or chemotherapy after surgery, following radiotherapy there were improved disease-free conditions according to tumor staging and nodal staging in enrolled patients (p≤0.05 for both, Table 3).

Table 3.

Tumor staging according to American Joint Committee on Cancer classification system for oncology before and after chemotherapy following radiotherapy treatment.

| Group | Control) | FFO | FFIO | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level | BL | EP | p | q | BL | EP | p | q | BL | EP | p | q |

| Sample size | 115 | 115 | 115 | 115 | 115 | 115 | ||||||

| Tumor-staging | ||||||||||||

| T0 | 0 (0) | 6 (5) | 0.00089 | 14.606 | 0 (0) | 21 (18) | 0.000167 | 18.455 | 0 (0) | 25 (22) | 0.00013 | 31.559 |

| T1 | 0 (0) | 19 (17) | 0 (0) | 19 (17) | 0 (0) | 41 (36) | ||||||

| T2 | 0 (0) | 31 (30) | 0 (0) | 37 (32) | 0 (0) | 33 (29) | ||||||

| T3 | 83 (72) | 44 (38) | 79 (69) | 29 (25) | 73 (63) | 12 (10) | ||||||

| T4a | 21 (18) | 10 (7) | 22 (19) | 7 (6) | 19 (17) | 3 (3) | ||||||

| T4b | 11 (10) | 3 (3) | 14 (12) | 2 (2) | 23 (20) | 1 (1) | ||||||

| Nodal-staging | ||||||||||||

| N0 | 28 (24) | 47 (41) | 0.00019 | 4.379 | 26 (23) | 44 (38) | 0.0002 | 6.279 | 23 (20) | 59 (51) | 0.00001 | 11.261 |

| N1 | 17 (15) | 16 (14) | 18 (16) | 27 (23) | 17 (15) | 11 (10) | ||||||

| N2 | 61 (53) | 44 (38) | 58 (50) | 35 (30) | 63 (55) | 43 (37) | ||||||

| N3 | 9 (8) | 8 (7) | 13 (11) | 9 (8) | 12 (10) | 2 (2) | ||||||

BL – before surgery; EP – after completion of total treatment(s). Data were represented as Number (Percentage). p value for Wilcoxon rank sum test; q value for Turkey post hoc test.

Surgery only did not sufficiently decrease elevated levels of carbohydrate antigen (p=0.0653) and carcinoembryonic antigen 19-9 (p=0.0592). However, after surgery, chemotherapy following radiotherapy succeeded in maintaining elevated levels of carbohydrate antigen and carcinoembryonic antigen 19-9 (p≤0.05 for both, Table 4).

Table 4.

Effect of chemotherapeutic treatment on clinicopathological responses after complication of treatment.

| Pathological parameters | Group | Control | FFO | FFIO | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level | BL | EP | BL | EP | BL | EP | ||||||

| Sample size | 115 | 115 | p | 115 | 115 | p | q | 115 | 115 | p | q | |

| CA19-9 | ≤27 ng/L | 17 (15) | 37 (32) | 0.0653 | 21 (18) | 67 (58) | 0.0029 | 5.432 | 14 (12) | 94 (82) | 0.0018 | 7.532 |

| >27 ng/L | 98 (85) | 78 (68) | 94 (82) | 48 (42) | 101 (88) | 21 (18) | ||||||

| CEA | ≤5 ng/L | 34 (30) | 49 (43) | 0.0592 | 23 (20) | 87 (77) | 0.0031 | 6.321 | 27 (23) | 93 (81) | 0.00098 | 8.534 |

| >5 ng/L | 81 (70) | 66 (57) | 92 (80) | 28 (23) | 88 (67) | 22 (19) | ||||||

Data were represented as Number (Percentage). BL – before surgery; EP – after completion of total treatment(s). p value for Wilcoxon rank sum test; q value for Turkey post hoc test. CA19-9: carbohydrate antigen; CEA – carcinoembryonic antigen.

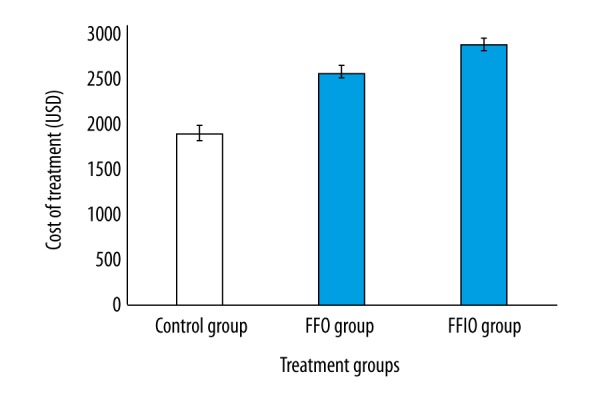

The cost of chemotherapeutic treatments was in the order of FFIO group > FFO group > control group (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Cost of chemotherapeutic treatments. n=150 for all groups. Data are represented as mean ±SD. Bootstrap procedure.

Non-fatal treatment-emergent adverse effects were due to chemotherapeutic drugs only (p≤0.05 for all effects). However, fatal chemotherapeutic treatment-emergent adverse effects were observed only in the FFIO group (p=0.00001 for all effects, Table 5).

Table 5.

Fatal and non-fatal chemotherapeutic treatment emergent adverse effects after complication of treatment.

| Type | Group | 1 (Control) | 2 (FFO) | 1 vs. 2 | 3 (FFIO) | 1 vs. 3 | 2 vs. 3 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample size | 115 | 115 | p | q | 115 | p | q | p | q | |

| Fatal treatment emergent adverse effect | Neutropenia | 0 (0) | 3 (3) | 0.083 | 1.545 | 9 (8) | 0.0024 | 4.634 | 0.0137 | 3.089 |

| Thrombocytopenia | 0 (0) | 5 (4) | 0.0247 | 2.384 | 9 (8) | 0.0024 | 4.294 | 0.045 | 1.907 | |

| Hepatic diseases | 0 (0) | 7 (6) | 0.0076 | 2.97 | 11 (10) | 0.0007 | 4.667 | 0.045 | 1.697 | |

| Peripheral neurotoxicity | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 0.3194 | 0.542 | 8 (7) | 0.0042 | 5.420 | 0.0076 | 4.878 | |

| Pulmonary complications | 0 (0) | 9 (8) | 0.0024 | 3.039 | 22 (19) | 0.00001 | 7.428 | 0.0002 | 4.389 | |

| Non-fatal treatment emergent adverse effect | Nausea* | 9 (8) | 75 (65) | 0.00001 | 16.806 | 108 (94) | 0.00001 | 26.409 | 0.00001 | 9.603 |

| Vomiting* | 1 (1) | 35 (30) | 0.00001 | 8.131 | 42 (37) | 0.00001 | 9.805 | 0.0002 | 1.674 | |

| Stomatitis | 1 (1) | 17 (15) | 0.00001 | 4.74 | 23 (20) | 0.00001 | 6.518 | 0.0004 | 1.778 | |

| Diarrhea | 3 (3) | 8 (7) | 0.0247 | 1.73 | 17 (15) | 0.00001 | 4.843 | 0.0001 | 3.113 | |

| Fatigue | 4 (3) | 15 (13) | 0.007 | 4.29 | 27 (23) | 0.00001 | 8.971 | 0.0001 | 4.681 | |

| skin rashes | 0 (0) | 12 (10) | 0.0042 | 3.723 | 23 (20) | 0.00001 | 8.272 | 0.0001 | 4.55 | |

Data were represented as Number (Percentage). p value for two tailed t-tests; q value for Turkey post hoc test. For statistical analysis presence of adverse effect was considered as 1 and absence of that was considered as 0.

Patients had already taken anti-emetic.

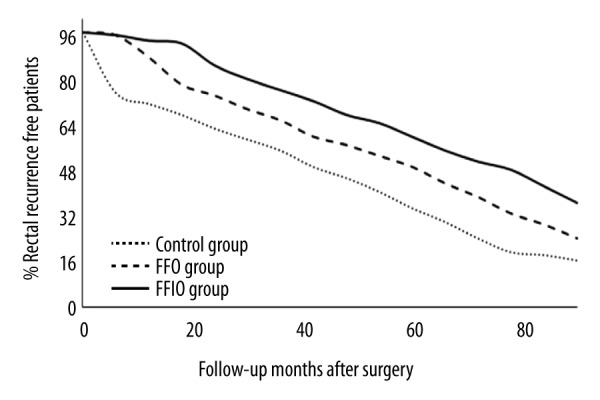

The FFIO group had more rectal cancer-free patients than in the FFO and Control groups during 90 months of follow-up (p≤0.05, Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Only rectal cancer recurrence analysis as per treatment. For statistical analysis, the rectal cancer condition of the patient was considered as 1 and rectal cancer-free condition of the patient was considered as 0. RECIST guidelines evaluation. Scores were higher in the FFIO group than in the FFO and Control groups during follow-up (p≤0.05).

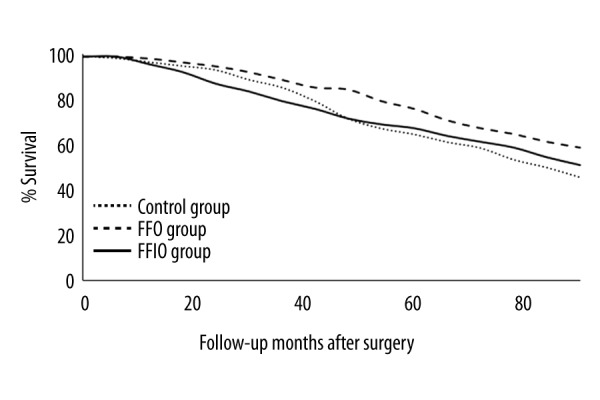

Overall survival irrespective of diseased condition was higher in the FFO group than in the Control and FFIO groups during 90 months of follow-up (p≤0.05, Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Overall survival irrespective of cancerous condition analysis as per treatment. For statistical analysis, survival, irrespective of disease condition, was considered as 0, and death due to any condition was considered as 1. Scores were higher in the FFO group than in the Control and FFIO groups (p≤0.05).

Total cancer-free conditions were decreased as the follow-up time increased in all 3 groups (p≤0.05, Table 6).

Table 6.

Total cancer recurrence analysis as per treatment.

| Follow-up time (months) | Total cancer free patients (%) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | |||||||||

| 1 (Control) | 2 (FFO) | 1 vs. 2 | 3 (FFIO) | 1 vs. 3 | 2 vs. 3 | ||||

| p | q | p | q | p | q | ||||

| At EP | 115 (100) | 115 (100) | N/A | N/A | 115 (100) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 6 | 85 (74) | 110 (96) | 0.00001 | 8.155 | 114 (99) | 0.000001 | 9.46 | 0.045 | 1.305 |

| 12 | 68 (47) | 101 (88) | 0.00002 | 8.496 | 110 (96) | 0.000002 | 10.813 | 0.0024 | 2.317 |

| 18 | 50 (43) | 92 (80) | 0.00003 | 9.697 | 105 (91) | 0.000003 | 12.698 | 0.0002 | 3.001 |

| 24 | 45 (39) | 85 (74) | 0.00006 | 8.667 | 99 (86) | 0.000004 | 11.701 | 0.0001 | 3.034 |

| 30 | 40 (35) | 80 (70) | 0.00005 | 8.314 | 92 (80) | 0.000005 | 10.808 | 0.0004 | 2.494 |

| 36 | 36 (31) | 77 (67) | 0.000035 | 8.313 | 85 (74) | 0.000006 | 9.935 | 0.0042 | 1.622 |

| 42 | 34 (30) | 72 (63) | 0.000045 | 7.519 | 78 (68) | 0.000007 | 8.706 | 0.0137 | 1.187 |

| 48 | 33 (29) | 68 (59) | 0.000051 | 7.016 | 71 (62) | 0.000008 | 7.406 | 0.083 | 0.39 |

| 54 | 31 (27) | 61 (53) | 0.000041 | 5.801 | 65 (57) | 0.000009 | 6.574 | 0.045 | 0.773 |

| 60 | 28 (24) | 58 (50) | 0.000062 | 5.833 | 59 (51) | 0.00006 | 6.028 | 0.0833 | 0.194 |

| 66 | 25 (22) | 49 (43) | 0.000058 | 4.742 | 51 (44) | 0.000054 | 5.335 | 0.1582 | 0.593 |

| 72 | 20 (17) | 41 (36) | 0.000053 | 4.509 | 45 (39) | 0.000049 | 5.329 | 0.045 | 0.82 |

| 78 | 19 (17) | 35 (30) | 0.000036 | 3.556 | 44 (38) | 0.000033 | 5.438 | 0.0024 | 1.882 |

| 84 | 18 (16) | 31 (27) | 0.0002 | 2.996 | 41 (36) | 0.00003 | 5.136 | 0.0013 | 2.14 |

| 90 | 15 (13) | 29 (25) | 0.0001 | 1.163 | 38 (33) | 0.000025 | 5.438 | 0.1582 | 4.185 |

EP: after successful completion of treatment. Data were represented as Number (Percentage). N/A – not applicable. p value for two tailed t-tests; q value for Turkey post hoc test. For statistical analysis, the cancerous condition of the patient was considered as 1 and total cancer free condition of the patient was considered as 0. RECIST guidelines evaluation.

Discussion

FOLFOX4 and FOLFIRINOX regimens satisfactorily controlled elevated levels of carbohydrate antigen and carcinoembryonic antigen in Chinese rectal cancer patients. Surgery only failed to control pathological responses of cancerous conditions [20]. The data were identical with the use of these regimens in the other cancer treatment [25]. To the best of our knowledge, the present study is the first to succeed in maintaining pathological responses in cancerous conditions in a Chinese population.

The cost of chemotherapeutic treatments was high, and overall survival irrespective of cancerous condition was less in the FFIO group than in the FFO group. FFIO regimens have more of cycles, more chemotherapeutic drugs, and higher scheduled and unscheduled costs than the FFO regimen [21]. The cost and overall survival analyses can assist decision-making in the selection of chemotherapeutic treatment regimens in rectal cancer.

There were more deaths in the FFIO group as compared to the FFO group. FOLFIRINOX is an aggressive regimen in rectal cancer, which has high rate of fatal chemotherapeutic treatment-emergent adverse effects [16]. In respect to selecting the FOLFIRINOX chemotherapeutic regimen, FOLFIRINOX should be used in advanced rectal cancer to control tumors.

There were more deaths in the Control group than in the FFO and FFIO groups. Surgery after diagnosis of rectal cancer or surgery following chemotherapy and radiotherapy is necessary for improvement of tumor staging and nodal-staging in rectal cancer patients [2]. However, surgical resection only leads to more chance of recurrence [7]. With respect to the choice of treatment for rectal cancer, chemotherapy improved the overall survival of patients, irrespective of disease condition.

There were fewer total cancer recurrence patients in the FFIO group than in the Control and FFO groups. The FOLFIRINOX regimen is predominantly used when patients have a high risk of metastasis [16] and was found to be safer safe than and superior to gemcitabine [26]. However, the FOLFOX4 regimen is used as the standard first-line chemotherapeutic treatment in rectal cancer [4], and surgical resection is the standard of care for rectal cancer [13]. In considering the analysis of outcome measures and treatment-emergent adverse effects, our study provides useful information for selection of a suitable regimen of chemotherapeutic agents according to stage of rectal cancer.

Limitations of the present study include the fact that the secondary effects of the combination of FOLFIRINOX and gemcitabine or FOLFOX4 and gemcitabine were not evaluated. The study was focussed on chemotherapeutic regimens only. The study did not evaluate radiological parameters related to treatment-emergent adverse effects and did not provide bifurcations of the cost of treatment. Sensitivity analyses testing was not reported in the manuscript. The survival data were generated to provide information on whether there was a systemic relapse.

Conclusions

The published ethical guidelines for oncologists conclude that FOLFOX4 or FOLFIRINOX are necessary after rectal cancer surgery to overcome recurrence. Total cancer recurrence was less in the FOLFIRINOX group than in the FOLFOX4 group. However, fatal treatment-emergent adverse effects and cost of treatment were higher in the FOLFIRINOX group than in the FOLFOX4 group. However, overall survival, irrespective of cancerous condition, was higher in the FOLFOX4 group than in the FOLFIRINOX group. Specifically designed chemotherapeutic regimens are required fit the patient profile.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all the individuals, healthcare providers, technicians, and administrative staff of Huzhou Central Hospital, China who enabled this work to be carried out.

Footnotes

Source of support: Departmental sources

Conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Yao Y-F, Du C-Z, Chen N, et al. Expression of HER-2 in rectal cancers treated with preoperative radiotherapy: A potential biomarker predictive of metastasis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2013;57:602–7. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000000107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Trakarnsanga A, Ithimakin S, Weiser MR. Treatment of locally advanced rectal cancer: Controversies and questions. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:5521–32. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i39.5521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Petersen SH, Harling H, Kirkeby LT, et al. Postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy in rectal cancer operated for cure. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(3):CD004078. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004078.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Park SH, Sung JY, Han S-H, et al. Oxaliplatin, folinic acid and 5-fluorouracil (FOLFOX-4) combination chemotherapy as second-line treatment in advanced colorectal cancer patients with irinotecan failure: A Korean single-center Experience. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2005;35:531–35. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyi140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wasan HS, Gibbs P, Sharma NK, et al. FOXFIRE trial investigators, SIRFLOX trial investigators, FOXFIRE-Global trial investigators. Hazel GV, Sharma RA. First-line selective internal radiotherapy plus chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone in patients with liver metastases from colorectal cancer (FOXFIRE, SIRFLOX, and FOXFIRE-Global): A combined analysis of three multicenter, randomized, phase 3 trials. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18(9):1159–71. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30457-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim SY, Hong YS, Kim DY, et al. Preoperative chemoradiation with cetuximab, irinotecan, and capecitabine in patients with locally advanced resectable rectal cancer: A multicenter phase II study. Int J Radiation Oncology Biol Phys. 2011;81:677–83. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.06.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stanel SC, Sjoberg J, Salmonson T, et al. European medicines agency approval summary: Zaltrap for the treatment of patients with oxaliplatin-resistant metastatic colorectal cancer. ESMO Open. 2017;2(2):e000190. doi: 10.1136/esmoopen-2017-000190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Milinis K, Thornton M, Montazeri A, Rooney PS. Adjuvant chemotherapy for rectal cancer: Is it needed? World J Clin Oncol. 2015;6:225–36. doi: 10.5306/wjco.v6.i6.225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tsuji K, Yasui H, Onozawa Y, et al. Modified FOLFOX-6 therapy for heavily pretreated advanced gastric cancer refractory to fluorouracil, irinotecan, cisplatin, and taxanes: A retrospective study. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2012;42:686–90. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hys084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smalley SR, Benedetti JK, Williamson SK, et al. Phase III trial of fluorouracil-based chemotherapy regimens plus radiotherapy in postoperative adjuvant rectal cancer: GI INT 0144. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3542–47. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.9544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wolpin BM, Meyerhardt JA, Mamon HJ, Mayer RJ. Adjuvant treatment of colorectal cancer. CA-Cancer J Clin. 2009;57:168–85. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.57.3.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wong RKS, Tandan V, De Silva S, Figueredo A. Pre-operative radiotherapy and curative surgery for the management of localized rectal carcinoma (review) Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(2):CD002102. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002102.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gonzalez-Flores E, Losa F, Pericay C, et al. SEOM Clinical Guideline of localized rectal cancer (2016) Clin Transl Oncol. 2016;18:1163–71. doi: 10.1007/s12094-016-1591-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Balyasnikova S, Brown G. Optimal imaging strategies for rectal cancer staging and ongoing management. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2016;17(6):32. doi: 10.1007/s11864-016-0403-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yu SK, Bhangu A, Tait DM, et al. Chemoradiotherapy response in recurrent rectal cancer. Cancer Med. 2014;3:111–17. doi: 10.1002/cam4.169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ostwal V, Engineer R, Ramaswamy A, et al. Surgical outcomes of post chemoradiotherapy unresectable locally advanced rectal cancers improve with interim chemotherapy, is FOLFIRINOX better than CAPOX? J Gastrointest Oncol. 2016;7:958–67. doi: 10.21037/jgo.2016.08.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Edge SB, Compton CC. The American Joint Committee on Cancer: The 7th Edition of the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual and the Future of TNM. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:1471–74. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-0985-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schneitler S, Kropil P, Riemer J, et al. Metastasized pancreatic carcinoma with neoadjuvant FOLFIRINOX therapy and R0 resection. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:6384–90. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i20.6384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tokunaga R, Sakamoto Y, Nakagawa S, et al. The utility of tumor marker combination, including serum P53 antibody, in colorectal cancer treatment. Surg Today. 2016;47:636–42. doi: 10.1007/s00595-016-1464-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang LN, Xiao W-W, Xi SY, et al. Pathological assessment of the AJCC tumor regression grading system after preoperative chemoradiotherapy for Chinese locally advanced rectal cancer. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95(3):e2272. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000002272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tse VC, Ng WT, Lee V, et al. Cost-analysis of XELOX and FOLFOX4 for treatment of colorectal cancer to assist decision making on reimbursement. BMC Cancer. 2011;11:288. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-11-288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stattaus J. Oncological imaging for therapy response assessment. Radiologe. 2014;54:69–78. doi: 10.1007/s00117-013-2586-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ferrone CR, Marchegiani G, Hong TS, et al. Radiological and surgical implications of neoadjuvant treatment with FOLFIRINOX for locally advanced and borderline resectable pancreatic cancer. Ann Surg. 2015;261:12–17. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rouanet P, Rullier E, Lelong B, et al. the GRECCAR Study Group. Tailored treatment strategy for locally advanced rectal carcinoma based on the tumor response to induction chemotherapy: Preliminary results of the French phase II multicenter GRECCAR4 trial. Dis Colon Rectum. 2017;60:653–63. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000000849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Christians KK, Tsai S, Mahmoud A, et al. Neoadjuvant FOLFIRINOX for borderline resectable pancreas cancer: A new treatment paradigm? Oncologist. 2014;19:266–74. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2013-0273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peixoto RD, Ho M, Renouf DJ, et al. Eligibility of metastatic pancreatic cancer patients for first-line palliative intent nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine versus FOLFIRINOX. Am J Clin Oncol. 2015 doi: 10.1097/COC.0000000000000193. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]