Abstract

Introduction:

Most women who quit smoking during pregnancy will relapse postpartum. Interventions for sustained postpartum abstinence can benefit from understanding prenatal characteristics associated with treatment response. Given that individuals with psychiatric disorders or elevated depressive symptoms have difficulty quitting smoking and that increases in depressive symptoms prenatally are common, we examined the relevance of psychiatric diagnoses, prenatal depressive symptoms, and stress to postpartum relapse prevention intervention response.

Methods:

Pregnant women (N = 300) who quit smoking during pregnancy received intervention (with specialized focus on mood, weight, and stress [STARTS] or a comparison [SUPPORT]) to prevent postpartum relapse. As previously published, nearly one-third and one-quarter of women achieved biochemically-confirmed sustained abstinence at 24- and 52-weeks postpartum, with no difference in abstinence rates between the interventions. Women completed psychiatric interviews and questionnaires during pregnancy. Smoking was assessed in pregnancy, and 24- and 52-weeks postpartum.

Results:

Psychiatric disorders did not predict sustained abstinence or treatment response. However, treatment response was moderated by end-of-pregnancy depressive symptoms (χ2 = 9.98, p = .002) and stress (χ2 = 6.90, p = .01) at 24- and 52-weeks postpartum and remained significant after including covariates. Women with low distress achieved higher abstinence rates in SUPPORT than in STARTS (37% vs. 19% for depressive symptoms; 36% vs. 19% for stress), with no difference for women with high symptoms.

Conclusions:

Prenatal depressive symptoms and stress predicted differential treatment efficacy in women with low symptoms, not in women with high symptoms. Diagnostic history did not predict treatment differences. Future research to address prenatal distress may help tailor postpartum relapse prevention interventions.

Implications:

We examined prenatal history of psychiatric disorders and psychiatric distress as moderators of response to postpartum smoking relapse prevention intervention that either included or did not include added content on mood, stress, and weight concerns. For women with lower psychiatric distress, the added focus is not necessary, as these women achieved greater sustained abstinence in the less-intensive treatment. Understanding which women need which level of care to sustain abstinence can help allocate resources for all postpartum former smokers. These findings underscore the importance of perinatal symptom monitoring and promoting behavioral health more broadly in pregnant and postpartum women.

Introduction

A majority of cigarette smokers who quit as a result of pregnancy will resume smoking within the first 6 months postpartum. Recent systematic reviews have determined that psychosocial interventions effectively promote smoking cessation during pregnancy,1 and not enough data exist to determine whether pharmacotherapies are effective with prenatal (ie, during pregnancy, before delivery) smoking cessation.2 Notably, despite quitting during pregnancy, many women relapse: by 1 year postpartum, more than 65%3–6 and as many as 90%7 of women who quit during pregnancy will resume smoking without intervention. Postpartum maternal smoking is associated with myriad negative health consequences for women,8–12 infants,13,14 and children,15–17 and preventing postpartum relapse can capitalize on the high rates of prenatal smoking cessation and have a large impact on maternal and offspring health.18 Although some interventions designed to prevent postpartum relapse have increased the duration of postpartum smoking abstinence,5,19,20 no postpartum relapse prevention strategies have been published that report biochemically-validated abstinence by 1 year postpartum. In our recent trial of two cognitive-behavioral relapse prevention interventions delivered 6 months postpartum, we found high rates (24%) of biochemically-validated abstinence at 1 year postpartum, although no differences between the intervention conditions.21 Our finding was similar to results from a recent trial comparing intensive smoking abstinence intervention to an information-only control condition.22 In that trial, intervention and control content were delivered in the third trimester and throughout the first postpartum year, and no difference was found between conditions.22 The authors found that women’s level of risk for relapse moderated response to intervention.22 We sought to examine maternal characteristics that increase vulnerability to relapse and, particularly, to focus on potentially modifiable psychosocial factors.

In general, psychiatric distress is linked to smoking23 and rates of psychiatric disorders are high among individuals who smoke.24–28 Rates of psychiatric disorders also are high among pregnant women29,30 and associated with perinatal (ie, before and after delivery, including the prenatal and postpartum periods) smoking. For example, 45% of pregnant smokers also had at least one psychiatric disorder,31 and interview-assessed rates of current mood and anxiety disorders have been linked to smoking among pregnant women maintained on methadone.32 Pregnant women also report substantial psychological distress,33 which is related to perinatal smoking during the perinatal period.33,34 However, pregnant women with comorbid psychiatric conditions can and do quit smoking.35 Given that psychiatric comorbidity is associated with smoking generally and among women in the perinatal period, we reasoned that the presence of prenatal psychiatric conditions or the experience of significant prenatal psychiatric symptoms might interfere with postpartum abstinence.

Our work36,37 and that of others6,20,38–40 has documented that changes in mood, the experience of stress, and concerns about weight relate to women’s smoking behavior postpartum. For example, pregnant women who reported feeling able to manage their weight without smoking also reported confidence in their ability to remain abstinent postpartum.36 In a qualitative review of postpartum smoking relapse, stress was a commonly-reported reason for relapse, including use of smoking for stress management.41 Moreover, positive affect and concerns about smoking-related weight gain prospectively predicted a rapid return to smoking postpartum,37 which was, in turn, associated with lower weight postpartum.42 Similarly perinatal anxiety, depressive symptoms,40 and stress43 have been identified as risk factors for postpartum smoking relapse. Thus, psychiatric disorders and measures of psychiatric distress have been linked to smoking and may specifically affect postpartum smoking relapse and response to relapse prevention interventions.

Although treatments to address perinatal smoking have not consistently been successful in preventing relapse postpartum,44 results of our recent trial21 suggest interventions adapted to the specific demands on women during the postpartum period increase rates of sustained abstinence. In that trial, two behavioral smoking relapse prevention interventions were evaluated. One included additional cognitive-behavioral intervention with specialized focus on postpartum mood, smoking-related weight concerns and stress, whereas the other intervention provided a supportive attention-controlled comparator. Rates of biochemically-confirmed sustained abstinence were 34% and 24% at 24- and 52-weeks postpartum across the two interventions and there were no differences in rates of sustained abstinence between the interventions. Notably, a recent meta-analysis of relapse prevention interventions delivered during pregnancy found that across studies with 6-month data (ie, 24-weeks postpartum), approximately 74% of women had resumed smoking.45 Thus, our interventions achieved a higher rate of sustained abstinence, suggesting postpartum-adapted relapse prevention intervention can help women. Although the interventions in our trial did not differ overall in efficacy, we reasoned that maternal characteristics might be related to intervention response. Specifically, we posited that psychiatric disorders and symptoms might moderate intervention response, as these have been linked to difficulty quitting and are common among women during the postpartum period.40

We found high rates of lifetime psychiatric disorders among pregnant former smokers, with approximately half of the women (56.94%) reporting symptoms consistent with at least one psychiatric disorder.46 Thus, we sought to examine the relative efficacy of two postpartum-adapted smoking relapse prevention programs based on women’s prenatal reports about (1) whether they had a lifetime history of a psychiatric disorder, (2) the specific category of psychiatric disorder, and (3) their level of prenatal psychiatric distress. We hypothesized that women with a history of psychiatric disorders would be more likely to relapse postpartum, but an intervention that addressed mood, stress, and other postpartum psychological concerns that precipitate relapse might help women with mood and anxiety disorders more than a time- and attention-controlled comparison. Finally, given the impact of depressive symptoms and stress on relapse among nonpregnant adults,47 we also evaluated the role of these symptoms on intervention response, reasoning that women with higher psychiatric distress might benefit more from the cognitive-behavioral strategies for mood management and stress reduction than from the supportive control condition, while women with lower distress may not need the added mood and stress emphasis.

Methods

Participants

Participants were 300 pregnant former smokers (between 34 and 38 weeks gestation) enrolled in a larger randomized controlled trial investigating the efficacy of postpartum smoking relapse prevention interventions. Eligibility for the larger study, as detailed elsewhere,48 required women to have stopped smoking during or immediately prior to this pregnancy. Smoking cessation was documented prior to enrollment using the timeline follow-back methodology and an expired-air carbon monoxide (CO) level less than or equal to 8 parts per million (ppm). Descriptive information for the sample has been previously reported (see Levine et al.46).

Women who had quit smoking for their current pregnancy completed baseline assessments during their third trimester of pregnancy. Women were then randomly assigned to receive intervention with added focus on mood, stress, and weight concerns (Strategies to Avoid Returning to Smoking; STARTS) or a supportive, time- and attention-controlled comparison without this added focus (SUPPORT) during the first 6 months postpartum.

Interventions

Women in both the STARTS and SUPPORT interventions received cognitive-behavioral smoking relapse prevention techniques. Women in both interventions also were asked to monitor urges to smoke and received behavioral support to address cravings and high-risk situations. Additionally, women in both interventions received education about healthy postpartum weight loss and the use of physical activity as an alternative to smoking.

However, the interventions differed in the approach to psychiatric distress. SUPPORT focused only on behavioral urges to smoke whereas STARTS incorporated additional cognitive-behavioral techniques to address psychosocial issues related to smoking urges. Women in STARTS were asked to track situations, thoughts, and feelings related to mood and stress in addition to smoking urges.48,49 Thoughts and beliefs were challenged and cognitive-behavioral strategies for addressing these, such as increasing social contacts and balancing their needs with those of their new baby, were discussed. Similarly, smoking-specific weight concerns were targeted in STARTS, which previously has been shown to be related to relapse.48,50

Assessments

Demographic and Pregnancy-related Information

Women reported demographic and pregnancy-related information, including age, race, income, education, and parity at study enrollment.

Lifetime Psychiatric Diagnoses

Lifetime history of psychiatric disorders was assessed by trained clinicians using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Non-Patient Edition (SCID-I/NP).51 The SCID-I/NP is a widely used semi-structured interview that provides information on the presence or absence of both current and historical disorders in every category of psychiatric disorder, including, mood, anxiety, eating, and substance use disorders. Although the psychiatric diagnoses included in this study were scored based on DSM-IV-TR criteria, the categories of disorders are reported using DSM-5. For instance, obsessive compulsive disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder were treated as individual categories of disorders rather than included with the overall anxiety disorders. Interviews were administered by assessors trained to conduct SCID-I/NP interviews and who had achieved at least a priori level of 90% adherence to standardized administration and scoring on the SCID-I/NP prior to conducting the first research assessment for this project. To maintain the fidelity over time, supervision and feedback were provided weekly. This measure was added after initial study enrollment had begun. To maximize participation, and in light of our interest in lifetime psychiatric disorders, women who had already delivered (n = 66) were contacted postpartum to complete the SCID-I/NP within 55 weeks of delivery. However, the majority of women completed the interview, prenatally, at study enrollment (n = 215; see Levine et al.21). Diagnostic interviews that occurred during pregnancy were completed between 33 and 41 weeks gestation. Women who were assessed during pregnancy and those assessed postpartum did not differ in demographic variables, or rates of psychiatric disorders (ps > .32).46

Prenatal Psychiatric Distress

Psychiatric distress was measured using self-reported depressive symptoms and stress. Depressive symptoms were assessed using the Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression Scale (CES-D),52 which is less sensitive than other depression scales to somatic symptoms that may be common during the postpartum period.53 Women also completed the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS),54 a 14-item scale that has been used in other smoking cessation studies55 and assesses the degree to which an individual appraises situations as stressful.

Smoking Behavior

Because women were required to be abstinent at study enrollment, women were asked to think back to the last time they had smoked every day for at least 1 month and complete the Fagerstrom Test of Nicotine Dependence. Women also provided information on the number of cigarettes smoked prior to quitting, the number of years they had been smoking, and when and how they had quit smoking for their current pregnancy.

Smoking Status

At each assessment, women were interviewed about any smoking since their last assessment using a timeline follow-back format,56 and expired-air CO and a salivary cotinine sample were collected. Relapse was defined as the self-report of seven consecutive days of smoking, a CO > 8 ppm, or a cotinine level > 15 µg/L.57,58 In all cases where CO or cotinine indicated smoking, women were coded as relapsed. Women who dropped out of treatment were considered to have relapsed as of the day following the last visit on which abstinence was verified. Women were queried about smoking using a time line follow-back format and self-report of nonsmoking was confirmed by both expired-air CO and salivary cotinine. Relapse was defined as seven consecutive days of smoking or a CO greater than 8 ppm.58,57

Data Analyses

First, using Chi-square tests based on intention-to-treat, we compared the proportions of women with and without a history of psychiatric disorder in STARTS and SUPPORT who maintained abstinence at 24- and 52-weeks postpartum. Next, using generalized mixed model analyses, we evaluated the role of lifetime prevalence of disorder on relapse while including treatment condition (STARTS vs. SUPPORT), adjusting for other pretreatment factors previously related to postpartum relapse (age, race, education, and length of time quit prior to delivery), and evaluating the potential moderation of psychiatric disorder on treatment outcome by modeling the interaction of history of psychiatric disorders and treatment group. We repeated these analyses for specific categories of disorders to determine the relative strength of relations among the most common disorders (depressive, substance use, and anxiety disorders), and for depressive symptoms and stress, given their relevance to postpartum relapse and their distinction from frank psychiatric disorders.

Results

Among the women with a history of at least one psychiatric disorder, (n = 156, 56%), the most common disorder categories were depressive disorders (32%), substance use disorders (31%), and anxiety disorders (15%; see Levine et al.46 for details on the lifetime rates by psychiatric disorder).

Relationships Between Lifetime Psychiatric Disorders and Outcome of Interventions

Across intervention conditions, a lifetime history of psychiatric disorder was not associated with risk of relapse at either 24- or 52-weeks postpartum (ps > .60). As presented in Table 1, when examining differential treatment response, no significant effect was found for women with a history of psychiatric disorder (χ2(1) = 0.06, p = .80). However, among women without a lifetime history of psychiatric disorder (n = 120), those who were randomized to SUPPORT were more likely to sustain abstinence through 24- and 52-weeks postpartum than were those in STARTS (44% vs. 27% at 24-weeks, χ2(1) = 3.75, p = .05; 40% vs. 14% at 52-weeks, χ2(1) = 10.40, p = .001). In the model with covariates, the interaction between lifetime disorder and treatment group was not significant (p = .48) at 24-weeks postpartum (β = 1.81, p = .25), although it was more strongly associated at 52-weeks postpartum (β = 3.26, p = .02). Moreover, the overall moderation effect was not significant (χ2 = 2.78, p = .10).

Table 1.

Sustained Abstinence Rates Within Each Treatment Condition by Psychiatric Diagnosis and Distress Level

| % Sustained abstinence at 24-weeks postpartum | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Status | SUPPORT | STARTS | Statistic | p |

| History of psychiatric disorder | Yes | 36% abstinent (30/83) | 34% abstinent (25/73) | χ2(1) = 0.06 | .80 |

| No | 44% abstinent (25/57) | 27% abstinent (17/63) | χ2(1) = 3.75 | .05 | |

| History of mood disorder | Yes | 36% abstinent (17/47) | 31% abstinent (13/42) | χ2(1) = 0.27 | .60 |

| No | 41% abstinent (38/93) | 31% abstinent (29/94) | χ2(1) = 2.04 | .15 | |

| History of substance use disorder | Yes | 43% abstinent (18/42) | 40% abstinent (17/42) | χ2(1) = 0.05 | .82 |

| No | 38% abstinent (37/91) | 27% abstinent (25/94) | χ2(1) = 2.90 | .09 | |

| History of anxiety disorder | Yes | 53% abstinent (8/15) | 48% abstinent (12/25) | χ2(1) = 0.11 | .74 |

| No | 38% abstinent (47/124) | 27% abstinent (30/111) | χ2(1) = 3.14 | .08 | |

| Depressive symptoms | High | 25% abstinent (17/69) | 30% abstinent (18/60) | χ2(1) = 0.47 | .49 |

| Low | 49% abstinent (40/81) | 29% abstinent (26/90) | χ2(1) = 7.55 | .006 | |

| Perceived stress | High | 25% abstinent (19/77) | 31% abstinent (20/65) | χ2(1) = 0.66 | .42 |

| Low | 52% abstinent (38/73) | 28% abstinent (24/85) | χ2(1) = 9.34 | .002 | |

| % Sustained abstinence at 52-weeks postpartum | |||||

| History of psychiatric disorder | Yes | 20% abstinent (17/83) | 29% abstinent (21/73) | χ2(1) = 1.45 | .23 |

| No | 40% abstinent (23/57) | 14% abstinent (9/63) | χ2(1) = 10.40 | .001 | |

| History of mood disorder | Yes | 21% abstinent (10/47) | 26% abstinent (11/42) | χ2(1) = 0.30 | .59 |

| No | 32% abstinent (30/93) | 20% abstinent (19/94) | χ2(1) = 3.51 | .06 | |

| History of substance use disorder | Yes | 21% abstinent (9/42) | 33% abstinent (14/42) | χ2(1) = 1.50 | .22 |

| No | 32% abstinent (31/97) | 17% abstinent (16/94) | χ2(1) = 5.74 | .02 | |

| History of anxiety disorder | Yes | 33% abstinent (5/15) | 40% abstinent (10/25) | χ2(1) = 0.18 | .67 |

| No | 28% abstinent (35/124) | 18% abstinent (20/111) | χ2(1) = 3.40 | .07 | |

| Depressive symptoms | High | 14% abstinent (10/69) | 25% abstinent (15/60) | χ2(1) = 2.27 | .13 |

| Low | 37% abstinent (30/81) | 19% abstinent (17/90) | χ2(1) = 7.05 | .008 | |

| Perceived stress | High | 18% abstinent (14/77) | 25% abstinent (16/65) | χ2(1) = 0.88 | .35 |

| Low | 36% abstinent (26/73) | 19% abstinent (16/85) | χ2(1) = 5.67 | .02 | |

Relationships With Specific Categories of Psychiatric Disorders and Outcome of Interventions

No effect was found for lifetime history of mood disorders or anxiety disorders in Chi-square or regression analyses (ps > .06). The only significant effect found for history of substance use disorders was at 52-weeks postpartum: among women without a history of substance use disorders, those in SUPPORT achieved greater rates of abstinence than those in STARTS (32% vs. 17%, χ2(1) = 5.74, p = .02). However, this difference no longer remained after adjusting for covariates (β = 1.83, p = .13), and the overall moderation effect was not significant (χ2 = 0.14, p = .71).

Relationships Between Psychiatric Distress and Outcome of Interventions

Given that depressive symptoms, stress, and smoking-related weight concerns were specifically targeted in the STARTS treatment, we examined the role of depressive symptoms and stress as moderators of treatment response, especially because women may experience a range of depressive symptoms and stress without meeting criteria for a psychiatric diagnosis. Using the continuous measures, women with fewer depressive symptoms and less stress at the end of pregnancy were more likely to achieve sustained abstinence in SUPPORT than in STARTS at 24- and 52-weeks, and the moderation effects remained significant after adjusting for relevant covariates (χ2 = 9.98, p = .002 for depressive symptoms; χ2 = 6.90, p = .009 for stress).

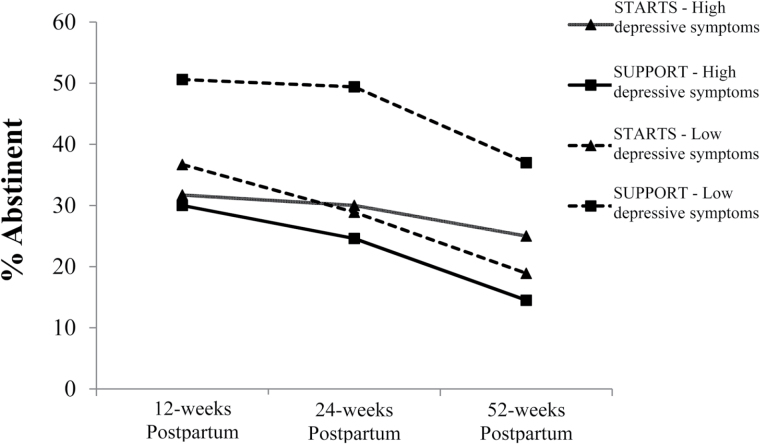

To illustrate the moderator interactions, we dichotomized women into those with and without clinically significant distress. For prenatal depressive symptoms, we used a cutoff of 16 on the CES-D.52 STARTS and SUPPORT were not differentially efficacious among women with high prenatal depressive symptoms (ps > .13), but differences in relapse were observed for those with low depressive symptoms. Specifically, women with low depressive symptoms at the end of pregnancy were more likely to remain abstinent through 24- and 52-weeks postpartum in the SUPPORT intervention than in STARTS with 49% versus 29% achieving sustained abstinence at 24 weeks (χ2(1) = 7.55, p = .006) and 37% vs. 19% achieving sustained abstinence at 52 weeks (χ2(1) = 7.04, p = .008) (see Figure 1). After adjusting for race, age, number of weeks quit, and education, the effect of depressive symptoms (above vs. below the cutoff) still significantly moderated the effect of treatment on cessation at 24- (β = 2.62, p = .02) and 52-weeks (β = 2.55, p = .02). Again, for those with low depressive symptoms, the odds of relapse at 24 weeks for the women who received STARTS was 2.6 times the odds of the women who received SUPPORT folks (p = .01). Moreover, the odds of relapse remained higher for women in STARTS than in SUPPORT (odds ratio [OR] = 2.5, p = .02) at 52-weeks postpartum.

Figure 1.

Abstinence by depressive symptom cut-off score and intervention group over time.

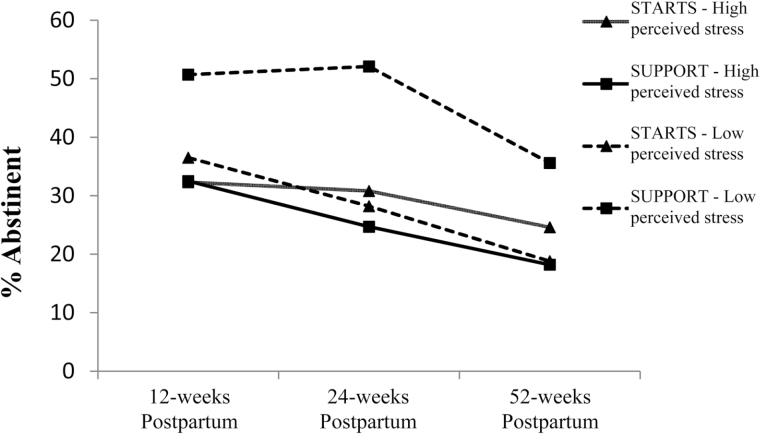

We observed similar patterns for stress, using a cutoff of 24 on the PSS based on a median-split in our sample, as there is not an identified cutoff score because it is not a diagnostic measure.59 Among women with high stress, no group differences emerged in treatment response at 24- or 52-weeks postpartum (ps > .35). Among women with low stress, sustained abstinence rates were higher in SUPPORT than in STARTS with 52% versus 28% achieving sustained abstinence at 24 weeks (χ2(1) = 9.35, p = .002) and 36% vs. 19% achieving sustained abstinence at 52 weeks (χ2(1) = 5.67, p = .02) (see Figure 2). The adjusted moderator effect was significant for women with low stress at 24 weeks (β = 2.52, p = .03) but not at 52 weeks (β = 1.94, p = .13), and the only group difference that emerged was found at 24 weeks among women with low stress (OR = 2.5, p = .03).

Figure 2.

Abstinence by perceived stress and intervention group over time.

Discussion

This study presents the first data on the role of lifetime psychiatric disorders and psychiatric distress in relation to sustained abstinence following postpartum intervention among women who quit smoking during pregnancy. Our results did not support use of lifetime psychiatric disorder history or any particular disorder as a moderator of treatment response. Rather, our results suggest prenatal depressive symptoms and stress may predict response to postpartum relapse treatment. Specifically, we found that women with fewer depressive symptoms and less stress are more likely to achieve sustained abstinence in a less-intensive, supportive intervention than one with added cognitive-behavioral techniques for mood, stress, and weight concerns.

The finding that lifetime psychiatric history was not associated with relapse was contrary to our hypotheses. There are mixed findings regarding relations between psychiatric disorders and relapse prevention in non-perinatal individuals, with some data indicating that present psychiatric disorders predicted smoking status, not history of psychiatric disorder. Given that women with a psychiatric disorder history responded similarly to both the STARTS and SUPPORT interventions, it is likely that the behavioral strategies and interaction with supportive staff (ie, common treatment elements) were helpful for women with a psychiatric disorder history.

The finding that recent depressive symptoms and stress moderated response to postpartum relapse prevention intervention, even after adjusting for covariates known to predict relapse, suggest that these measures may help identify women for whom a supportive behavioral, postpartum-adapted intervention will yield greater outcomes. For women with low levels of psychiatric distress, an intervention that offers support and behavioral techniques to sustain abstinence, designed for postpartum women and delivered during the first 6 months in the postpartum year is helpful. Interestingly, the more intensive intervention with added cognitive-behavioral techniques to address postpartum mood, stress, and weight concerns was found to be less effective in this group. The present results suggest that for women with low psychiatric distress, such added focus is unnecessary.

One possible explanation for the better abstinence rates in women with low distress in SUPPORT is that there was less effort involved with engaging in treatment (eg, less emphasis on and homework related to addressing psychosocial concerns). Although attendance rates were the same for each intervention (see Levine et al.21), it is possible that women were better able to engage in the less intensive, supportive behavioral intervention in the context of the postpartum period. Future studies that include qualitative data to better understand the treatment process and women’s reactions to postpartum behavioral relapse prevention intervention are warranted. In this era of promoting personalized medicine, our findings support tailoring treatment based on individuals’ symptom levels; in this case, the STARTS intervention, with the added content on managing mood, stress, and weight concerns, was beyond necessary for women with low psychiatric distress. Thus, the behavioral strategies for managing cravings and addressing changes in the postpartum period, delivered in a fashion adapted to the time demands of new mothers in SUPPORT were more likely to yield sustained smoking abstinence for women with low psychiatric distress.

Notably, we did not find a moderator effect among women with high depressive symptoms or stress. This was in contrast to a previous study, which found that women with higher baseline levels of prenatal depressive symptoms achieved greater abstinence rates postpartum in a cognitive-behavioral depression-focused intervention compared to a health and wellness control condition.44 Of note, the interventions in the previous research were delivered prenatally and thus the baseline symptom assessment and treatment delivery overlapped, whereas our baseline prenatal depressive symptom assessments occurred several months prior to postpartum intervention delivery. Furthermore, as we have previously reported,21 depressive symptoms improved for women in both STARTS and SUPPORT, and perhaps engagement in either intervention was helpful for participants with higher psychiatric distress.

Given that our measures of psychiatric distress were not pregnancy-specific or adapted to address the perinatal period, those women who were identified as having high distress may represent a group with mixed levels of symptomatology, particularly as higher scores on the CES-D can be related to fatigue or other pregnancy-related symptoms, rather than depressive symptoms alone. As pregnancy and psychiatric distress both involve physical symptoms, it may be necessary to distinguish women with higher distress who may benefit from intervention with greater mood and stress management from those who respond to less-intensive supportive intervention. It is possible that assessment tools designed to evaluate perinatal distress would be more sensitive to pregnancy-specific symptoms and determine whether women with psychiatric symptoms warrant additional treatment content to increase their likelihood of achieving sustained abstinence postpartum.

Importantly, the assessments of depressive symptoms and stress used herein were self-report questionnaires that can be easily completed by women, and easily collected, scored, and interpreted by health care providers. These questionnaires offer advantages over semi-structured clinical interviews conducted by trained staff and that require additional time and supervision to determine psychiatric diagnoses. For example, a brief questionnaire about depressive symptoms or stress may be implemented by prenatal care providers to screen patients who quit smoking during pregnancy and help to (1) identify women with low or high psychiatric distress, and (2) refer women with low distress to supportive behavioral relapse prevention intervention. For women with high psychiatric distress, screening may increase their referral to and engagement in intervention for smoking relapse prevention and indicated psychiatric issues.

There are several strengths of the study, including the large and diverse sample, characterization of psychiatric disorders and distress using validated semi-structured interviews and questionnaires, randomization to interventions, prospective data collection, evaluation of baseline prenatal variables as moderators of postpartum intervention response, and repeated measurements of biochemically-confirmed sustained abstinence over the first postpartum year. There are limitations to note, including that while we obtained lifetime history of psychiatric disorders, our measurement of psychiatric distress symptoms only focuses on the past several weeks. Repeated measurement of recent symptoms may identify meaningful trajectories (eg, women who have consistent vs. fluctuating levels of distress) that enhance our ability to predict treatment response based on patterns of distress throughout pregnancy, rather than a single timepoint for prenatal assessment. Additionally, diagnostic criteria for psychiatric disorders were evaluated by an interview using DSM-IV criteria, as the DSM-5 was published during data collection. Although we categorized the reported information using DSM-5 criteria when possible, the rates of lifetime history of psychiatric disorders and subsequent interaction with treatment response may have yielded different relapse rates if a DSM-5 interview had been used. Furthermore, this study did not include information about the severity of lifetime psychiatric illness, such as level of care received (eg, prior hospitalizations and outpatient sessions). It is also worthwhile to note that the measure of cotinine testing includes e-cigarette use as smoking, meaning that there may have been false positives for relapse. E-cigarette use and other nicotine replacement therapy were recorded as additional treatments, although these did not affect the outcomes.

Helping women to quit smoking and sustain abstinence, especially during the perinatal period, offers a unique and important window for improving the health of mothers and their children. Our data suggest that assessing self-reported psychiatric distress may help identify interventions for sustaining postpartum smoking abstinence for women with minimal psychiatric distress. Thus, these findings underscore the importance of perinatal symptom monitoring and highlight future directions of research related to addressing psychiatric symptoms and promoting behavioral health more broadly in pregnant and postpartum women.

Funding

This research was supported by National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01 DA 021608) and National Institute of Mental Health (T32 MH018269). ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT00757068.

Declaration of Interests

None declared.

References

- 1. Chamberlain C, O’Mara-Eves A, Oliver S, et al. Psychosocial interventions for supporting women to stop smoking in pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;10:CD001055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Coleman T, Chamberlain C, Davey MA, Cooper SE, Leonardi-Bee J. Pharmacological interventions for promoting smoking cessation during pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;9:CD010078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fingerhut LA, Kleinman JC, Kendrick JS. Smoking before, during, and after pregnancy. Am J Public Health. 1990;80(5):541–544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mullen PD, Quinn VP, Ershoff DH. Maintenance of nonsmoking postpartum by women who stopped smoking during pregnancy. Am J Public Health. 1990;80(8):992–994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ratner PA, Johnson JL, Bottorff JL, Dahinten S, Hall W. Twelve-month follow-up of a smoking relapse prevention intervention for postpartum women. Addict Behav. 2000;25(1):81–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. McBride CM, Pirie PL. Postpartum smoking relapse. Addict Behav. 1990;15(2):165–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hannöver W, Thyrian JR, Röske K, et al. Smoking cessation and relapse prevention for postpartum women: results from a randomized controlled trial at 6, 12, 18 and 24 months. Addict Behav. 2009;34(1):1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Zang EA, Wynder EL. Differences in lung cancer risk between men and women: examination of the evidence. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1996;88(3–4):183–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Castelao JE, Yuan JM, Skipper PL, et al. Gender- and smoking-related bladder cancer risk. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93(7):538–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Castle PE, Wacholder S, Lorincz AT, et al. A prospective study of high-grade cervical neoplasia risk among human papillomavirus-infected women. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94(18):1406–1414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Baron JA, La Vecchia C, Levi F. The antiestrogenic effect of cigarette smoking in women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1990;162(2):504–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Prescott E, Hippe M, Schnohr P, Hein HO, Vestbo J. Smoking and risk of myocardial infarction in women and men: longitudinal population study. BMJ. 1998;316(7137):1043–1047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dybing E, Sanner T. Passive smoking, sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) and childhood infections. Hum Exp Toxicol. 1999;18(4):202–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ey JL, Holberg CJ, Aldous MB, Wright AL, Martinez FD, Taussig LM. Passive smoke exposure and otitis media in the first year of life. Group Health Medical Associates. Pediatrics. 1995;95(5):670–677. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Maughan B, Taylor C, Taylor A, Butler N, Bynner J. Pregnancy smoking and childhood conduct problems: a causal association? J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2001;42(8):1021–1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cornelius MD, Day NL. The effects of tobacco use during and after pregnancy on exposed children. Alcohol Res Health. 2000;24(4):242–249. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kahn RS, Zuckerman B, Bauchner H, Homer CJ, Wise PH. Women’s health after pregnancy and child outcomes at age 3 years: a prospective cohort study. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(8):1312–1318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Involuntary Exposure to Tobacco Smoke: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Coordinating Center for Health Promotion, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 19. McBride CM, Curry SJ, Lando HA, Pirie PL, Grothaus LC, Nelson JC. Prevention of relapse in women who quit smoking during pregnancy. Am J Public Health. 1999;89(5):706–711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Severson HH, Andrews JA, Lichtenstein E, Wall M, Akers L. Reducing maternal smoking and relapse: long-term evaluation of a pediatric intervention. Prev Med. 1997;26(1):120–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Levine MD, Cheng Y, Marcus MD, Kalarchian MA, Emery RL. Preventing postpartum smoking relapse: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(4):443–452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Pollak KI, Fish LJ, Lyna P, et al. Efficacy of a nurse-delivered intervention to prevent and delay postpartum return to smoking: the quit for two trial. Nicotine Tob Res. 2016;18(10):1960–1966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hughes JR, Hatsukami DK, Mitchell JE, Dahlgren LA. Prevalence of smoking among psychiatric outpatients. Am J Psychiatry. 1986;143(8): 993–997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Smith PH, Mazure CM, McKee SA. Smoking and mental illness in the U.S. population. Tob Control. 2014;23(e2):e147–e153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Aubin HJ, Rollema H, Svensson TH, Winterer G. Smoking, quitting, and psychiatric disease: a review. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2012;36(1):271–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lasser K, Boyd JW, Woolhandler S, Himmelstein DU, McCormick D, Bor DH. Smoking and mental illness: a population-based prevalence study. JAMA. 2000;284(20):2606–2610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ziedonis D, Hitsman B, Beckham JC, et al. Tobacco use and cessation in psychiatric disorders: National Institute of Mental Health report. Nicotine Tob Res. 2008;10(12):1691–1715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Niaura R, Britt DM, Shadel WG, Goldstein M, Abrams D, Brown R. Symptoms of depression and survival experience among three samples of smokers trying to quit. Psychol Addict Behav. 2001;15(1):13–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Vesga-López O, Blanco C, Keyes K, Olfson M, Grant BF, Hasin DS. Psychiatric disorders in pregnant and postpartum women in the United States. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65(7):805–815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Andersson L, Sundström-Poromaa I, Bixo M, Wulff M, Bondestam K, åStröm M. Point prevalence of psychiatric disorders during the second trimester of pregnancy: a population-based study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189(1):148–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Goodwin RD, Keyes K, Simuro N. Mental disorders and nicotine dependence among pregnant women in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109(4):875–883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Chisolm MS, Tuten M, Brigham EC, Strain EC, Jones HE. Relationship between cigarette use and mood/anxiety disorders among pregnant methadone-maintained patients. Am J Addict. 2009;18(5):422–429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Glasheen C, Colpe L, Hoffman V, Warren LK. Prevalence of serious psychological distress and mental health treatment in a national sample of pregnant and postpartum women. Matern Child Health J. 2015;19(1):204–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Orr ST, Blazer DG, Orr CA. Maternal prenatal depressive symptoms, nicotine addiction, and smoking-related knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors. Matern Child Health J. 2012;16(5):973–978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Flick LH, Cook CA, Homan SM, McSweeney M, Campbell C, Parnell L. Persistent tobacco use during pregnancy and the likelihood of psychiatric disorders. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(10):1799–1807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Levine MD, Marcus MD, Kalarchian MA, Weissfeld L, Qin L. Weight concerns affect motivation to remain abstinent from smoking postpartum. Ann Behav Med. 2006;32(2):147–153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Levine MD, Marcus MD, Kalarchian MA, Houck PR, Cheng Y. Weight concerns, mood, and postpartum smoking relapse. Am J Prev Med. 2010;39(4):345–351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Carmichael SL, Ahluwalia IB. Correlates of postpartum smoking relapse. Results from the Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS). Am J Prev Med. 2000;19(3):193–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Park ER, Chang Y, Quinn VP, Ross K, Rigotti NA. Perceived support to stay quit: what happens after delivery? Addict Behav. 2009;34(12):1000–1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Correa-Fernández V, Ji L, Castro Y, et al. Mediators of the association of major depressive syndrome and anxiety syndrome with postpartum smoking relapse. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2012;80(4):636–648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Notley C, Blyth A, Craig J, Edwards A, Holland R. Postpartum smoking relapse–a thematic synthesis of qualitative studies. Addiction. 2015;110(11):1712–1723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Levine MD, Cheng Y, Marcus MD, Kalarchian MA. Relapse to smoking and postpartum weight retention among women who quit smoking during pregnancy. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2012;20(2):457–459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Correa JB, Simmons VN, Sutton SK, Meltzer LR, Brandon TH. A content analysis of attributions for resuming smoking or maintaining abstinence in the post-partum period. Matern Child Health J. 2015;19(3):664–674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Cinciripini PM, Blalock JA, Minnix JA, et al. Effects of an intensive depression-focused intervention for smoking cessation in pregnancy. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2010;78(1):44–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Jones M, Lewis S, Parrott S, Wormall S, Coleman T. Re-starting smoking in the postpartum period after receiving a smoking cessation intervention: a systematic review. Addiction. 2016;111(6):981–990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Levine MD, Cheng Y, Marcus MD, Emery RL. Psychiatric disorders and gestational weight gain among women who quit smoking during pregnancy. J Psychosom Res. 2015;78(5):504–508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Buczkowski K, Marcinowicz L, Czachowski S, Piszczek E. Motivations toward smoking cessation, reasons for relapse, and modes of quitting: results from a qualitative study among former and current smokers. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2014;8:1353–1363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Levine MD, Marcus MD, Kalarchian MA, Cheng Y. Strategies to Avoid Returning to Smoking (STARTS): a randomized controlled trial of postpartum smoking relapse prevention interventions. Contemp Clin Trials. 2013;36(2):565–573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Hall SM, Muñoz RF, Reus VI, et al. Mood management and nicotine gum in smoking treatment: a therapeutic contact and placebo-controlled study. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1996;64(5):1003–1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Levine MD, Perkins KA, Kalarchian MA, et al. Bupropion and cognitive behavioral therapy for weight-concerned women smokers. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(6):543–550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders, Research Version, Non-patient Edition. (SCID-I/NP). New York, NY: Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Radloff L. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Measur. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Coyle CP, Roberge JJ. The psychometric properties of the Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression Scale (CES-D) when used with adults with physical disabilities. Psychol Health. 1992;7(1):69–81. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983;24(4):385–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Cohen S. Contrasting the hassles scale and the perceived stress scale: who’s really measuring appraised stress? Am Psychol. 1986;41(6):716–718. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Brown RS, Burgess ES, Sales SD, Whiteley JA, Evans DM, Miller IW. Reliability and validity of a smoking timeline follow-back interview. Psychol Addict Behav. 1998;12(2):101–112. [Google Scholar]

- 57. Ossip-Klein DJ, Bigelow G, Parker SR, Curry S, Hall S, Kirkland S. Classification and assessment of smoking behavior. Health Psychol. 1986;5(suppl):3–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Hughes JR, Keely JP, Niaura RS, Ossip-Klein DJ, Richmond RL, Swan GE. Measures of abstinence in clinical trials: issues and recommendations. Nicotine Tob Res. 2003;5(1):13–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Cohen S. Scales. Carnegie Mellon University website www.psy.cmu.edu/~scohen/scales.html Updated February 19, 2015. Accessed June 15, 2016.