Abstract

Introduction

During the 2000s the number of adolescents who became new smokers in the United States declined while the number of young adults who did so increased. However, we do not know among which demographic groups these changes occurred.

Methods

We analyzed data from the 2006 to 2013 National Survey of Drug Use and Health (n = 180 079). Multivariate linear regression models were used to assess annual trends in smoking onset and log-binomial regression models to assess changes over time in the risk of smoking onset among young adults (18- to 25-years-old) relative adolescents (12- to 17-years-old).

Results

From 2006 to 2013, the rate of onset among young adults (6.3%) was greater than among adolescents (1.9%). Time trends demonstrated that annual declines in smoking onset occurred among white young adult males and females. Rates of smoking onset increased among black and Hispanic young adult males with a lower rate of decline among black and Hispanic young adult females. There was a greater risk of smoking onset among young adults relative to adolescents that did not change over time.

Conclusions

Smoking onset is becoming more concentrated in the young adult than adolescent years. Despite this trend, there were annual declines in young adult smoking onset but not uniformly across racial/ethnic groups. More effective strategies to prevent young adult smoking onset may contribute to a further decline in adult smoking and a reduction in tobacco-related health disparities.

Implications

Smoking onset is becoming more concentrated in the young adult years across sex and racial/ethnic groups. The United States may be experiencing a period of increasing age of smoking onset and must develop tobacco control policies and practices informed by these changes.

Introduction

Cigarette smoking continues to be the leading cause of preventable death in the United States.1 Although the number of adolescents who start smoking has decreased or remained stable during the 2000s,2,3 the number of young adults who do so has doubled.2 Relative to what we know about smoking onset among adolescents, we know very little about onset among young adults. In a systematic review of the literature on smoking onset, thousands of articles were identified on onset among adolescents compared to tens of articles among young adults.4

We do know that nearly all young adults onset smoking occurs between the ages of 18 and 255 and that females and racial/ethnic minorities have relatively high rates of smoking onset during the young adult years.5–8 One national study found that one-third of women who smoke initiate during the young adult years compared to one-quarter of men9 and the gap in smoking onset during young adulthood is greater among racial/ethnic minority females.5,7,10 Another national study found that of women who smoke, nearly half of black women initiate smoking in adulthood, with most onset occurring during the young adult years.5

The extent to which these demographic characteristics of smoking onset have changed during the 2000s is not known. Yet significant youth focused tobacco control activity has occurred in recent decades that has contributed to a decline in adolescent smoking onset11 but may have had limited effect on young adults.12,13 For example, the Synar Amendment required that for states to receive certain federal grants they had to prohibit the sale of cigarettes to minors under the age of 18.14 The Tobacco Master Settlement Agreement imposed restrictions on marketing and advertising to adolescents and funded the youth-targeted anti-smoking truth campaign which was associated with an estimated 450 000 fewer adolescents initiating cigarette smoking during the early 2000s.15,16

Knowledge on the demographic trends in smoking onset among young adults is necessary to target policies and resources more effectively, particularly for women and racial/ethnic minorities who have a relatively high risk of young adult onset smoking and most vulnerable to tobacco-related health disparities.17 For example, when women initiate smoking they are less likely than men to quit18,19 and are more likely to develop health problems.20 Although African Americans are less likely to ever smoke, if they do initiate smoking they carry a disproportionate burden of tobacco-related diseases such as cancer.17,21,22

The purpose of this study is to examine time trends in smoking onset among adolescents and young adults by sex and race/ethnicity from 2006 to 2013. We first examine smoking onset among successive annual cohorts of adolescent and young adult males and females by race/ethnicity from 2006 to 2013. We then examine whether the risk of smoking onset among young adults relative to adolescents changed between cohorts and whether changes varied by sex and race/ethnicity.

Youth focused tobacco control activities from the early 2000s such as the truth campaign were associated with a reduction in smoking onset among adolescents.15,23 By examining smoking onset among annual cohorts of adolescents and young adults from 2006 to 2013, we will be able to determine whether the reductions in adolescent smoking onset from the early to mid-2000s16,23 were sustained among (1) more recent cohorts of adolescents, and (2) young adults who were adolescents during the early 2000s when youth focused tobacco control activities were more intense.24

We use data from the 2006 to 2013 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), a series of annual, nationally representative, cross-sectional surveys of the US civilian, non-institutionalized population 12 years of age and older residing within the United States.

Methods

NSDUH was designed to provide prevalence estimates of drug use in the household population of the United States aged 12 and older. NSDUH uses a multistage probability sample. Black/African Americans, Hispanics, and young adults (18- to 25-years-old) were oversampled to increase the precision of estimates for these groups. Surveys were administered in the home by trained interviewers. Interviewees were offered a monetary incentive for completion of the survey. Detailed survey methodology is available elsewhere.25

To anticipate medical and behavioral health service needs in the short and long term, policymakers are particularly interested in trends in recent smoking onset,2 defined as smoking onset in the past year.2 To estimate recent smoking onset, we examine smoking behaviors among adolescents (12- to 17-years-old) and young adults (18- to 25-years-old) who had never smoked 12 months prior to the date of survey interview. Nearly all adolescents (84.6%) and less than half (43.7%) of young adults who participated in the 2006 to 2013 surveys never smoked 12 months prior to the date of their interview.

We also limited our sample to adolescents and young adults who identified as white, non-Hispanic, black, non-Hispanic, Hispanic, Asian/Pacific Islander, non-Hispanic, due to potential estimate bias because of the small sample size of adolescent and young adults from the remaining racial/ethnic groups. Ninety-seven percent (97.2%) of adolescents and ninety-eight percent (97.8%) of young adults who participated in the 2006 to 2013 surveys identified as one of the four racial/ethnic groups (eg, American Indian or Alaska Native (AIAN)).

The final study sample was 180 079, with yearly survey sample sizes for adolescents ranging from 14 027 to 15 888 and young adults, ranging from 6813 to 8192.

Study Measures

Smoking Onset

The primary study outcome was smoking onset among successive annual cohorts of young adults and adolescents from 2006 to 2013. Daily smoking behaviors are shown to increase the risk of developing tobacco-related disease26 for which health services are needed. While many adolescents and young adults have smoked a cigarette, not all—less than half (44.8%) according to our analysis of 2006 to 2013 NSDUH data—escalate to the daily smoking behaviors shown to increase the risk of disease.26 Therefore, smoking onset—our primary study outcome—was defined as never smoking prior to 12 months of the survey and in the past 12 months (1) smoking part or all of a cigarette and (2) doing so every day for a period of at least 30 days.

We also present data on the average age of smoking onset. Age of smoking onset was the response to the question, “How old were you when you first started smoking cigarettes every day?”

Independent Variable

Study predictor variables were sex (male, female), race/ethnicity (white, non-Hispanic, black, non-Hispanic, Hispanic, Asian/Pacific Islander) and successive annual cohorts of adolescents and young adult from 2006 to 2013. Adolescents were defined as individuals between the ages of 12 and 17 and young adults, between the ages of 18 and 25. Adolescent and young adult definitions were based on age groups targeted by federal tobacco control efforts. Preventing tobacco use among individuals as young as 12 became an emphasis of federal tobacco control policy during the early 1990’s when data emerged on the (1) relationship between early age of onset and an increased risk of tobacco-related disease and (2) peer influence on smoking particularly within school environments.27 These and other observations from this period including that nearly all smoking onset occurs in adolescence, led to the establishment in 1992 of the national minimum legal age to purchase cigarettes of 18.14 During the 2000s, data emerged that nearly all smoking onset occurs by age 25.27 Therefore, the cutoff age for young adults was 25.

Data for these variables were acquired from the 2006 to 2013 NSDUH databases.

Statistical Analysis

The study addressed the following research questions: (1) Was there a change in the rate of smoking onset among successive annual cohorts of adolescents and young adults from 2006 to 2013? (2) Did young adults from more recent cohorts experience an increase in the risk of smoking onset relative to adolescents? (3) Did any of these changes vary by sex and race/ethnicity?

We first estimated the rate and mean age of smoking onset among the study sample. T-tests were used to compare the mean age of smoking onset between males and females, race/ethnic groups and survey periods (2006–2009 & 2010–2013). We then estimated the rate of smoking onset and used Chi-square tests to compare the rate of smoking onset between adolescents and young adults, males and females and race/ethnic groups.

To assess whether there were changes in the rate of smoking onset among successive annual cohorts of adolescents and young adults from 2006 and 2013, we used multivariate linear regression models. We created four models, one for each age by sex group: (adolescent males, adolescent females, young adult males, adolescent females). For each model, we first conducted a marginal analysis to estimate the rate of smoking onset per year and by race/ethnicity. The dependent variable was the rate of smoking onset per year and independent variables were annual cohort (year of the survey interview and race/ethnicity. To assess whether there were race/ethnic differences in changes in the annual rate of smoking onset, we included a race/ethnicity × survey year interaction term. Information on the number of people who have experienced smoking onset is useful for anticipating future service needs. For example, patterns of decline in smoking onset might translate into fewer new cases of people with heart disease or lung cancer.2 Therefore, we also estimate the number of adolescents and young adults who have experienced recent smoking onset and the average annual change in that number.

To assess whether young adults from more recent cohorts experienced an increase in the risk of smoking onset relative to adolescents, we used log-binomial regression models. We created two models, one for males and the other for females. The dependent variable was the relative risk (RR) of smoking onset and independent variables race/ethnicity and cohort. Adolescents and young adults were grouped into two cohorts, with the more recent cohorts being adolescents and young adults who participated in the 2010 to 2013 surveys. The more recent cohorts were exposed to the 2009 increase in the federal excise tax that was associated with declines in adolescent and young adult smoking onset.28 To test for race/ethnic differences, we included a three-way interaction between age group, race/ethnicity and cohorts.

All analyses (eg, rate of smoking onset, mean age of smoking onset, number of adolescents and young adults who experienced smoking onset) were weighted with weights provided by NSDUH to approximate the US population of individuals between the ages of 12–25.

Results

Table 1 presents rates and average age of smoking onset by cohort, sex and race/ethnicity. Smoking onset occurred among 3.7% of the study sample. The average age of smoking onset was 17.9 years. Whites (17.7 years) had a younger age of smoking onset than blacks (18.7 years), Hispanics (18.1 years) and Asian/PIs (18.9 years). The age of smoking onset increased slightly between cohorts who were 12- to 25-years-old during the period of 2006 to 2009 (17.8 years) and those who were 12- to 25-years-old during the period of 2010 to 2013 (18.1 years).

Table 1.

Percent and Mean Age of Past Year Smoking Onset by Time Period, Sex and Race/Ethnicity Among 12- to 25-Year Olds Who Never Smoked 12 Months Prior to the Survey: NSDUH 2006–2013

| Entire sample %100 | 2006–2009 period 48.2% | 2010–2013 period 51.8% | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 180 079) | (n = 86 602) | (n = 93 477) | ||||

| % | Mean age (CI) | % | Mean age (CI) | % | Mean age (CI) | |

| Entire sample | 3.7 | 17.9 (17.8–18.0) | 4.2 | 17.8 (17.6–17.9) | 3.2+++ | 18.1 (18.0–18.2)+ |

| White | 4.7 | 17.7 (17.6–17.8) | 5.3 | 17.5 (17.4–17.7) | 4.1++ | 17.9 (17.8–18.1) |

| Black | 2.5⌃⌃⌃ | 18.7 (18.4–18.9)⌃⌃ | 2.7⌃⌃⌃ | 18.3 (18.0–18.6)⌃⌃⌃ | 2.3⌃⌃⌃ | 19.1 (18.8–19.5)⌃⌃⌃ |

| Hispanic | 2.5⌃⌃⌃ | 18.1 (17.9–18.4)⌃⌃ | 2.8⌃⌃⌃ | 18.1 (17.7–18.5)⌃⌃ | 2.3⌃⌃⌃ | 18.2 (17.9–18.5) |

| Asian | 2.1⌃⌃⌃ | 18.9 (18.4–19.3)⌃⌃⌃ | 2.6⌃⌃⌃ | 19.1 (18.5–19.8)⌃⌃⌃ | 1.8⌃⌃⌃ | 18.6 (18.0–19.3)⌃ |

| Male | 4.2 | 18.0 (17.9–18.1) | 4.5 | 17.8 (17.7–18.0) | 3.8+++ | 18.2 (18.0–18.4)++ |

| White | 5.2 | 17.9 (17.7–18.0) | 5.7 | 17.7 (17.5–17.9) | 4.7 | 18.0 (17.8–18.2)+ |

| Black | 2.6⌃⌃⌃ | 18.5 (18.2–18.8)⌃⌃⌃ | 2.6⌃⌃⌃ | 18.0 (17.6–18.4) | 2.7⌃⌃⌃ | 18.9 (18.4–19.4)⌃⌃++ |

| Hispanic | 3.1⌃⌃⌃ | 18.1 (17.8–18.4) | 3.2⌃⌃⌃ | 17.8 (17.4–18.3) | 3.0⌃⌃⌃ | 18.4 (18.0–18.8) |

| Asian | 2.1⌃⌃⌃ | 19.1 (18.4–19.8)⌃⌃⌃ | 2.5⌃⌃⌃ | 19.4 (18.1–19.6)⌃⌃ | 1.7⌃⌃⌃ | 18.7 (18.1–19.4)⌃ |

| Female | 3.3*** | 17.8 (17.7–17.9)* | 4.0** | 17.7 (17.5–17.9) | 2.7***+++ | 18.0 (17.8–18.2)+ |

| White | 4.2*** | 17.5 (17.4–17.7)* | 5.0* | 17.4 (17.2–17.5) | 3.5***+++ | 17.7 (17.5–18.0)++ |

| Black | 2.4⌃⌃⌃ | 18.9 (18.5–19.2)⌃⌃⌃ | 2.8⌃⌃⌃ | 18.5 (18.0–19.0)⌃⌃⌃ | 1.9*⌃⌃⌃++ | 19.4 (18.9–19.9)⌃⌃⌃++ |

| Hispanic | 2.1***⌃⌃⌃ | 18.1 (17.7–18.6)⌃⌃ | 2.5⌃⌃⌃ | 18.4 (17.8–19.0)⌃⌃ | 1.7***⌃⌃⌃++ | 17.8 (17.3–18.3) |

| Asian | 2.2⌃⌃⌃ | 18.7 (18.1–19.3)⌃⌃⌃ | 2.6⌃⌃ | 18.8 (18.1–19.6)⌃⌃⌃ | 1.9⌃⌃ | 18.6 (17.6–19.5) |

NSDUH = National Survey of Drug Use and Health. Never smokers were persons who reported “no” to ever smoking a cigarette 12 months prior to participating in the survey. Smoking onset was persons who reported smoking part or a whole cigarette for the first time within 12 months of the survey and doing so every day. Age of onset is the age at which respondents reported first smoking cigarettes on a daily basis. Sample limited to adolescents and young adults who identified as white, black, Hispanic, and Asian. Data were weighted with weights provided by NSDUH to approximate the US population of persons between the ages of 12–25. Adolescents were persons between 12 and 17 and young adults between 18 and 25. T tests were used to assess differences in mean age of smoking onset between (1) males and females, (2) whites and other race/ethnic groups, and 2006–2009 and 2010 and 2013 time periods.

Different from males at the following levels:p < .05

p < .01

p < .001.

Different from whites at the following levels:p < .05

p < .01

p < .001.

Different from the 2006 to 2009 time period at the following level:p < .05

p < .01

p < .001.

All racial/ethnic differences in rates of smoking onset are statistically significant at the p < .001.

Table 2 presents rates of smoking onset among adolescents and young adults by sex and race/ethnicity. All differences in smoking onset were statistically different at the 0.001 level. Young adults exceeded adolescents in the rate of smoking onset (6.3% vs. 1.9%, respectively) and smoking onset among young adults was higher among white males and females than their racial/ethnic minority counterparts. For example, smoking onset occurred among 9.6% of white young adult males compared 3.8% to 5.7% of racial/ethnic minority young adult males. Smoking onset occurred among 6.7% of white young adult females compared to 3.3%–3.8% of racial/ethnic minority young adult females.

Table 2.

Percent of Smoking Onset by Sex and Race/Ethnicity Among Adolescents and Young Adults Who Never Smoked 12 Months Prior to the Survey: NSDUH 2006–2013

| Adolescents | White | Black | Hispanic | Asian | Young adults | White | Black | Hispanic | Asian | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 58.8% | 58.4% | 15.4% | 21.0% | 5.2% | 41.2% | 52,6% | 18.9% | 21.1% | 7.3% | |

| (n = 117 563) | (n = 72 518) | (n = 17 543) | (n = 22 602) | (n = 4900) | (n = 62 516) | (n = 34 206) | (n = 11 708) | (n = 12 656) | (n = 3946) | |

| Entire Sample | 1.9 | 2.6 | 0.9 | 1.2 | 0.6 | 6.3 | 8.1 | 4.4 | 4.4 | 3.7 |

| Male | 2.0 | 2.6 | 0.9 | 1.4 | 0.7 | 7.6 | 9.6 | 5.1 | 5.7 | 3.8 |

| Female | 1.9 | 2.6 | 0.9 | 1.1 | 0.6 | 5.1 | 6.7 | 3.8 | 3.3 | 3.6 |

NSDUH = National Survey of Drug Use and Health. Never smokers were persons who reported “no” to ever smoking a cigarette 12 months prior to participating in the survey. Smoking onset was persons who reported smoking part or a whole cigarette for the first time within 12 months of the survey and doing so every day. Sample limited to adolescents and young adults who identified as white, black, Hispanic, and Asian. Data were weighted with weights provided by NSDUH to approximate the US population of persons between the ages of 12–25. Adolescents were persons between 12 and 17 and young adults between 18 and 25. Chi-square tests were used to assess differences between adolescents and young adults and racial/ethnic differences among adolescents and young adults. All differences are statistically significant at the 0.001.

Trends in Smoking Onset

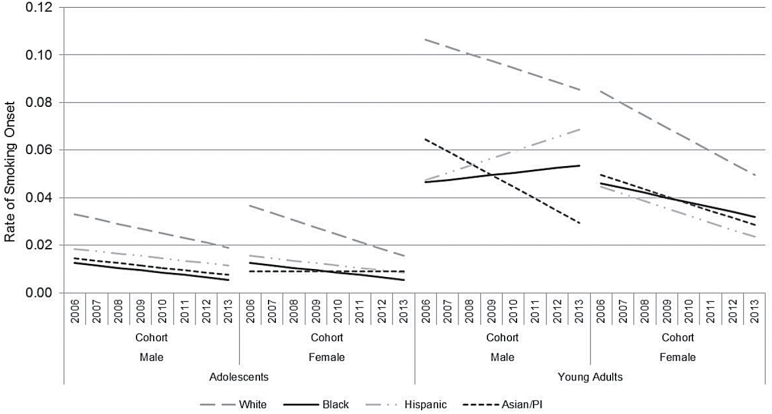

Table 3 and Figure 1 present estimates from multivariate regression models of smoking onset among successive annual cohorts of adolescents and young adults from 2006 to 2013. The “constant” (elevation) in the model represents the rate of smoking onset from 2006 to 2013 among whites; “cohort” is the annual rate of change (slope) in smoking onset among whites; “race/ethnicity” is the difference from whites in the rate of smoking onset (elevation) from 2006 to 2013; and “cohort × race/ethnicity” is the difference from whites in the annual rate of change (slopes) in smoking onset. For ease of presentation, the number of individuals who experienced smoking onset is rounded to two significant digits.

Table 3.

Estimates from multivariate regression models for trends in smoking onset by sex, race/ethnicity and annual cohort among adolescents and young adults who never smoked 12 months prior to the survey: NSDUH, 2006–2013

| Males | Females | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Β (SE) | p | Β (SE) | p | |

| Adolescent | ||||

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| Black | −0.017 | <.001 | −0.017 | <.001 |

| Hispanic | −0.011 | <.001 | −0.014 | <.001 |

| Asian/PI | −0.015 | <.001 | −0.017 | <.001 |

| Annual cohort | −0.002 | <.001 | −0.003 | <.001 |

| Race/ethnicity × cohort | ||||

| Black | 0.001 | .049 | 0.002 | .001 |

| Hispanic | 0.001 | .141 | 0.002 | .001 |

| Asian/PI | 0.001 | .365 | 0.003 | <.001 |

| Constant | 0.026 | 0.026 | ||

| R2 | 0.7397 | 0.8556 | ||

| N | 32 | 32 | ||

| Young adult | ||||

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| Black | −0.046 | <.001 | −0.028 | <.001 |

| Hispanic | −0.038 | <.001 | −0.033 | <.001 |

| Asian/PI | −0.049 | <.001 | −0.028 | <.001 |

| Annual cohort | −0.003 | <.001 | −0.005 | <.001 |

| Race/ethnicity × cohort | ||||

| Black | 0.004 | .011 | 0.003 | .014 |

| Hispanic | 0.006 | .001 | 0.002 | .036 |

| Asian/PI | −0.002 | .567 | 0.002 | .482 |

| Constant | 0.096 | 0.067 | ||

| R2 | 0.6338 | 0.6985 | ||

| N | 32 | 32 | ||

NSDUH = National Survey of Drug Use and Health. Never smokers were persons who reported “no” to ever smoking a cigarette 12 months prior to participating in the survey. Smoking onset were persons who reported smoking part or a whole cigarette for the first time within 12 months of the survey and doing so every day. Adolescents were persons between 12 and 17 and young adults between 18 and 25. “Cohort” is the slope for successive annual cohorts of White adolescents or young adults from 2006 to 2013. “Race/ethnicity × cohort” is the difference from the slope of successive annual cohorts of White adolescents or young adults from 2006 to 2013. Constant is the elevation of White, non-Hispanics. “Race/ethnicity” is the difference from Whites in elevation.

Figure 1.

Estimates from multivariate regression models for trends in smoking onset by sex, race/ethnicity and annual cohort among adolescents and young adults who never smoked 12 months prior to the survey: NSDUH, 2006–2013. National Survey of Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) Never smokers were persons who reported “no” to ever smoking a cigarette 12 months prior to participating in the survey. Smoking onset was persons who reported smoking part or a whole cigarette for the first time within 12 months of the survey and doing so every day. Adolescents were persons between 12 and 17 and young adults between 18 and 25. Annual cohorts were adolescents or young adults at the year of the survey interview. Changes in smoking onset among successive cohorts of: (1) black adolescent males were different from white adolescent males at a statistically significant level. (2) black, Hispanic, and Asian adolescent females were different from white adolescent females at a statistically significant level. (3) black and Hispanic young adult males were different from white young adult males at a statistically significant level. (4) black and Hispanic young adult females were different from white young adult females at a statistically significant level.

Adolescent Males

The annual rate of smoking onset during the period of 2006–2013 for adolescent White males were 0.026 (1.3 million adolescent white males) and lower for black (β = −0.017, <0.001; 0.009 or 120 000 adolescent black males), Hispanic (β = −0.011, <0.001; 0.015 or 270 000 adolescent Hispanic males) and Asian/PI (β = −0.015, <0.001; 0.011 or 49 000 adolescent Asian/PI males) adolescent males.

There was a 0.2 percentage point decline in smoking onset among each successive annual cohort of adolescent white males (β = −0.002, p < .001), that translates into smoking onset occurring among 13 000 fewer adolescent white males per year. There was a significant interaction between year and race/ethnicity such that the rate of annual decline among adolescent black males was not as great (β = 0.001, p = .049) as adolescent white males, there was a 0.1% percentage point decline or smoking onset occurring among 1600 fewer adolescent black males per year.

Adolescent Females

The rate of smoking onset during the period of 2006–2013 for adolescent white females was 0.026 (1.3 million adolescent white females) and lower among black (β = −0.017, <0.001; 0.009 or 120 000 adolescent black females), Hispanic (β = −0.014, <0.001; 0.012 or 210 000 adolescent Hispanic females) and Asian/PI (β = −0.017, <0.001; 0.009 or 39 000 adolescent Asian/PI females) adolescent females.

There was a 0.3 percentage point decline in smoking onset among each successive annual cohort of adolescent white females (β = −0.003, p < .001), that translates into smoking onset occurring among 18 000 fewer adolescent white females per year. There were significant interactions between year and race/ethnicity such that the rate of annual decline among adolescent black (β = 0.002, p = .001; 0.1 percentage point decline or 1600 fewer adolescent black females per year) and Hispanic (β = 0.002, p = .001; 0.1 percentage point decline or 2200 fewer adolescent Hispanic females per year) females was not as great as adolescent white females. There was no annual rate of change in smoking onset among adolescent Asian/PI females (β = 0.003, p < .001).

Young Adult Males

The rate of smoking onset during the period of 2006–2013 for young adult white males was 0.096 (2.9 million young adult white males) and lower among black (β = −0.046, p < .001; 0.050 or 480 000 young adult black males), Hispanic (β = −0.038, p < .001; 0.058 or 660 000 young adult Hispanic males) and Asian/PI (β = −0.049, <0.001; 0.047 or 180 000 young adult Asian/PI males) young adult males.

There was a 0.3 percentage point decline in smoking onset among each successive annual cohort of young adult white males (β = −0.003, p < .001), that translates into smoking onset occurring among 11 000 fewer young adult white males per year. There were significant interactions between year and race/ethnicity such that there was an increase in smoking onset among successive annual cohorts of black (β = 0.004, p = .011; 0.1 percentage point increase or 1200 more young adult black males per year) and Hispanic (β = 0.006, p = .001; 0.3 percentage point increase or 4300 more young adult Hispanic males per year) young adult males.

Young Adult Females

The rate of smoking onset during the period of 2006–2013 for young adult white females was 0.067 (2.2 million young adult white females) and lower among black (β = −0.028, p < .001; 0.039 or 490 000 young adult black females), Hispanic (β = −0.033, p < .001; 0.034 or 460 000 young adult Hispanic females) and Asian/PI (β = −0.028, <0.001; 0.039 or 190 000 young adult Asian/PI females) young adult females.

There was a 0.5 percentage point decline in smoking onset among each successive annual cohort of young adult white females (β = −0.005, p < .001), that translates into smoking onset occurring among 20 000 fewer young adult white females per year. There were significant interactions between year and race/ethnicity such that rate of annual decline among young adult black (β = 0.003, p = .014; 0.2 percentage point decline or 3200 fewer young adult black females per year) and Hispanic (β = 0.002, p = .036; 0.3 percentage point decline or 5000 fewer young adult Hispanic females per year) females was not as great as young adult white females.

RR of smoking Onset

We found sex differences in the relative risk of smoking onset (analysis not shown), the risk of smoking onset among young adults relative to adolescents was greater among males than females (RR: 1.36, CI: 1.15–1.61, p < .001). Therefore, all subsequent analysis was stratified by sex.

Table 4 presents the risks of smoking onset by sex, race/ethnicity and period cohort among young adults relative to adolescents.

Table 4.

Relative Risks From Log-Binomial Regression Models for Smoking Onset by Sex, Race/Ethnicity and Period Cohort Among Adolescents and Young Adults Who Never Smoked 12 Months Prior to the Survey: NSDUH, 2006–2013: NSDUH, 2006–2013

| Male (n = 87 324) | Female (n = 92 755) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RR (CI) | p | RR (CI) | p | |

| Age group | ||||

| Adolescent | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Young adult | 3.47 (3.04–3.97) | <.001 | 2.45 (2.14–2.82) | <.001 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| White | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Black | 0.36 (0.26–0.51) | <.001 | 0.39 (0.28–0.55) | .001 |

| Hispanic | 0.56 (0.43–0.74) | <.001 | 0.37 (0.26–0.53) | <.001 |

| Asian/PI | 0.30 (0.12–0.76) | .012 | 0.20 (0.08–0.52) | <.001 |

| Cohort | ||||

| 2006–2009 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| 2010–2013 | 0.72 (0.61–0.85) | <.001 | 0.61 (0.52–0.72) | <.001 |

| Race/ethnicity × 2010–2013 | ||||

| Black | 0.82 (0.46–1.47) | .508 | 0.68 (0.37–1.22) | .195 |

| Hispanic | 0.92 (0.56–1.49) | .727 | 1.39 (0.84–2.31) | .200 |

| Asian/PI | 0.70 (0.17–2.97) | .633 | 1.38 (0.33–5.73) | .653 |

| Young adult × 2010–2013 Cohort | 1.19 (0.97–1.47) | .843 | 1.15 (0.92–1.43) | .208 |

| Young adult × race/ethnicity | ||||

| Black | 1.31 (0.85–2.00) | .219 | 1.44 (0.96–2.19) | .081 |

| Hispanic | 0.95 (0.65–1.39) | .791 | 1.43 (0.93–1.93) | .113 |

| Asian/PI | 1.54 (0.54–4.34) | .417 | 2.61 (0.92–7.40) | .071 |

| Young adult × 2010–2013 cohort × race/ethnicity | ||||

| Black | 1.50 (0.77–2.94) | .234 | 1.53 (0.77–3.02) | .222 |

| Hispanic | 1.35 (0.74–2.46) | .331 | 0.63 (0.34–1.18) | .148 |

| Asian/PI | 1.05 (0.22–5.14) | .950 | 0.75 (0.16–3.56) | .715 |

NSDUH = National Survey of Drug Use and Health. Never smokers were persons who reported “no” to ever smoking a cigarette 12 months prior to participating in the survey. Smoking onset were persons who reported smoking part or a whole cigarette for the first time within 12 months of the survey and doing so every day. Adolescents were persons between 12 and 17 and young adults between 18 and 25. Period cohorts were adolescents or young adults at the date of the 2006–2009 or 2010–2013 survey interview. Data were weighted with weights provided by NSDUH to approximate the US population of persons between the ages of 12–25.

Males

The risk of smoking onset was more than three times greater among young adult males relative to adolescent males (RR: 3.47, CI: 3.04–3.97, p < .001). The risk of smoking onset was lower among racial/ethnic minority males relative to white males (blacks = RR: 0.36, CI: 0.26–0.51; Hispanic = RR: 0.56, CI: 0.43–0.74, p < .001; Asian/PI = RR: 0.30, CI: 0.12–0.55, p = .012). The risk of smoking onset was lower during the 2010 to 2013 than the 2009 to 2006 period (RR: 0.72, CI: 0.61–0.85, p < .001). The greater risk of smoking onset among young adults relative adolescents did not differ between periods or race/ethnicity.

Females

The risk of smoking onset was more than two times greater among young adult females relative to adolescent females (RR: 2.45, CI: 2.14–2.82, p < .001). The risk of smoking onset was lower among racial/ethnic minority females relative white females (Blacks = RR: 0.39, CI: 0.28–0.55; Hispanic = RR: 0.37, CI: 0.26–0.53, p < .001; Asian/PI = RR: 0.20, CI: 0.08–0.52, p < .001). The risk of smoking onset was lower during the 2010 to 2013 than the 2009 to 2006 period (RR: 0.61, CI: 0.52–0.72, p < .001). The greater risk of smoking onset among young adults relative adolescents did not differ between periods or race/ethnicity.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to examine time trends in smoking onset among adolescents and young adults by sex and race/ethnicity. Specifically, we examined smoking onset among successive annual cohorts of adolescents and young adults from 2006 to 2013. Significant tobacco control activity occurred during the 2000s that resulted in a decline in adolescent smoking.15,16 We found that not only did the rate of smoking onset decline among adolescents during the period of 2006 to 2013 but young adults well. However, these declines were not uniform across demographic groups. Although racial/ethnic minority adolescents and young adults had lower rates of smoking onset, they experienced no decline or increases in the rate of smoking onset. We also found that the greater risk of smoking onset among young adults relative to adolescents did not change over time (ie, after the increase in 2009 of the federal excise cigarette tax) and was higher among young adult males than females.

The higher risk of young adult relative to adolescent smoking onset occurred during a period of increasing social unacceptability of tobacco use, a result of nearly a half century of comprehensive tobacco control efforts.1 The young adults in our analysis were adolescents during the 1990s, a period when one major underpinning of tobacco control policy was the recognition that virtually all new users of tobacco products are under 18.29 Consequently, a central policy focus was on restricting the distribution and sale as well as the advertising and marketing of tobacco products to adolescents.29 Although these policies contributed to a decline in smoking onset among adolescents, they may be contributing to a shift in the age of smoking onset to the young adult years.

Age of smoking onset is not stable and has decreased over time.2,8,30 It was not until the 1990’s that smoking onset became characterized as a behavior of adolescents.31 The use of drugs among adolescents became a behavior to avoid at all cost and thus the implementation of policies to prevent use during that developmental period.32 A series of policies were implemented to prevent drug use among adolescence,32 most recently the Synar Amendment establishing 18 as the minimum legal age to purchase cigarettes.14 We may now be in a period of increase in the age of smoking onset not only in the United States but other countries as well,33 and must develop programs and policies informed by these changes.

Another underpinning of current federal tobacco control policy is that tobacco products are legal products available for use by adults (≥18-years-old).29 Accordingly, an assumption is that by 18, most people have the skills and knowledge to reject tobacco as an unhealthy practice and thus, a policy focus is to warn about the dangers of tobacco use and support smokers who want to quit.29 While some young adults choose to smoke cigarettes knowing the dangers of use, studies indicate that younger adults are less informed about the health risks and addictiveness of smoking34 and more likely to be exposed and susceptible to social influences of smoking.34,35 Policies that make tobacco more difficult to use in social settings such as making virtually all work places (eg, restaurants, bars, parks) smoke free might help to reduce the social influences of smoking among young adults.35 Some states have implemented tobacco free policies in social settings but a number of states allow smoking in these venues. This exposes young adults to smoking and perhaps contradicts common social norms about the unacceptability of smoking. Future research should seek to understand how young adults who become new smokers comprehend these contradictions.

Broad based policies focused on the prevention of smoking onset among young adults may also contribute to a reduction in tobacco-related health disparities. Women are more likely than men to initiate smoking in young adulthood,5,20 and this is particularly the case for black and Asian women. Black and Asian females generally have a later age of onset than white females 5–7 and studies do find health advantages among smokers who initiate at later ages.36–38 However, studies are beginning to emerge indicating that the health of women who initiate in adulthood is worse than men who initiate smoking during the same development period and similar to women who initiate in adolescence.20 Moreover, preventing smoking onset among young adult racial/ethnic minority women may also contributes to reduction in disparities in children’s health. Infants and toddlers exposed to second hand smoke are at an increased risk of poor health outcomes. Studies suggest that a majority of black women who start smoking do so in young adulthood and of those women, starting to smoke soon after the birth of their first child.39

More restrictive tobacco control policies, such as increasing the minimum legal age to purchase cigarettes, might be particularly effective in reducing smoking among racial/ethnic minorities. Already, racial/ethnic minority adolescents and young adults and their parents report higher levels than whites of smoking disapproval.35–38 It is thought that there is a greater desire by racial/ethnic minorities to adhere to norms, rules and laws43,44 out of concern for reinforcing negative stereotypes about their racial/ethnic group such as those related to being a drug user45 and to avoid the disparate consequences of use.46,47 These attitudes likely contribute to the relatively low rate of smoking among racial/ethnic adolescents and relatively high rate of smoking onset in adulthood when the restrictive barriers of smoking diminish. Future research should investigate reasons for onset within this more restrictive context (ie, youthful experimentation, coping with hardships).48

Our findings should be considered in the context of a few limitations. First, our primary smoking outcome was smoking onset within the 12 months of the survey interview. Thus, smoking onset that was classified as occurring in young adulthood (18–25 years old) could have occurred at age 17. However, the mean age at which daily smoking onset was close to 18 (17.9 years), which indicates that young adult smoking onset most likely occurred around 18 years of age. We did not assess smoking onset behaviors that took longer than one year. Progression from first cigarette to smoking onset can take multiple years. However, most progression to smoking onset occurs within one year.49 Moreover, our findings were sensitive to definitions of adolescents and young adults. For example, if we defined adolescents as individuals between the ages of 14 to 17 rather than 12 to 17, age group differences in smoking onset might not have been as great. Our findings were also sensitive to definitions of smoking onset. For example, if smoking onset was defined as smoking once a week rather than daily, similarly age group differences in smoking onset might not have been as great. While our definitions might have affected our findings on differences between age groups, our definitions did not affect our findings on changes within age groups. Our analysis on changes in smoking onset among successive annual cohorts of adolescents and young adults was conducted within each age group using a single definition of smoking onset.

In conclusion, programs and policies to prevent smoking onset in adolescence are well established and are imperative to maintain. However, the findings from this study strongly suggest that efforts to prevent smoking should be extended to young adults to reflect the increasing age of smoking onset. Efforts to prevent smoking among young adults may help to accelerate the decline in adult smoking rates,50 particularly among racial/ethnic minorities.

Funding

This study was supported by the Building Interdisciplinary Research Careers in Women’s Health (BIRCWH) Program (Carolyn Mazure, PI), National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), Office of Research on Women’s Health (ORWH), Office of the Director, National Institutes of Health (OD) and the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) (NIH K12DA031050) [ABT] and the ORWH and NIDA, (NIH P50DA033945) [SAM].

Declaration of Interests

None declared.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to acknowledge the many valuable suggestions made by Samuel Ball and the Yale BIRCWH writing group.

References

- 1. National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (US) Office on Smoking and Health. The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US); 2014. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK179276/ Accessed October 24, 2015 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lipar R, Kroutil L, Pemberton Michael. Risk and Protective Factors and Initiation of Substance Use: Results from the 2014 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future: National Results on Adolescent Drug Use: 2012 Overview of Key Findings on Adolescent Drug Use. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan, Institute for Social Research; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Freedman KS, Nelson NM, Feldman LL. Smoking initiation among young adults in the United States and Canada, 1998–2010: a systematic review. Prev Chronic Dis. 2012;9(110037):E05. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Moon-Howard J. African American women and smoking: starting later. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(3):418–420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Trinidad DR, Gilpin EA, Lee L, Pierce JP. Do the majority of Asian-American and African-American smokers start as adults?Am J Prev Med. 2004;26(2):156–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Thompson AB, Moon-Howard J, Messeri PA. Smoking cessation advantage among adult initiators: does it apply to black women?Nicotine Tob Res. 2011;13(1):15–21. doi:10.1093/ntr/ntq200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Burns DM, Lee L, Shen LZ, et al. Cigarette Smoking Behavior in the United States. Changes in Cigarette-Related Disease Risks and Their Implication for Prevention and Control. 1997:13–42. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jha P, Ramasundarahettige C, Landsman V, et al. 21st-century hazards of smoking and benefits of cessation in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(4):341–350. doi:10.1056/NEJMsa1211128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. King G, Bendel R, Delaronde SR. Social heterogeneity in smoking among African Americans. Am J Public Health. 1998;88(7):1081–1085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Farrelly MC, Loomis BR, Han B, et al. A comprehensive examination of the influence of state tobacco control programs and policies on youth smoking. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(3):549–555. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2012.300948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lantz PM. Smoking on the rise among young adults: implications for research and policy. Tob Control. 2003;12(suppl 1):i60–i70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Glied S. Is smoking delayed smoking averted?Am J Public Health. 2003;93(3):412–416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Grucza RA, Plunk AD, Hipp PR, et al. Long-term effects of laws governing youth access to tobacco. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(8):1493–1499. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2012.301123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Richardson AK, Green M, Xiao H, Sokol N, Vallone D. Evidence for truth®: the young adult response to a youth-focused anti-smoking media campaign. Am J Prev Med. 2010;39(6):500–506. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2010.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Farrelly MC, Nonnemaker J, Davis KC, Hussin A. The Influence of the National truth campaign on smoking initiation. Am J Prev Med. 2009;36(5):379–384. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2009.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. USDHHS. Health Consequences of Tobacco Use among Four Racial/Ethnic Minority Groups. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 18. King G, Polednak A, Bendel RB, Vilsaint MC, Nahata SB. Disparities in smoking cessation between African Americans and Whites: 1990-2000. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(11):1965–1971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. USDHHS. Women and Smoking: A Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, MD: Public Health Services; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Thompson AB, Tebes JK, McKee SA. Gender differences in age of smoking initiation and its association with health. Addict Res Theory. 2015;23(5):413–420. doi:10.3109/16066359.2015.1022159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Brown M, Howe H, E W, Ries L, et al. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1975–2002, featuring population-based trends in cancer treatment. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97(1):1407–1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Haiman CA, Stram DO, Wilkens LR, et al. Ethnic and racial differences in the smoking-related risk of lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(4):333–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chen X, Lin F, Stanton B, Zhang X. APC modeling of smoking prevalence among US adolescents and young adults. Am J Health Behav. 2011;35(4):416–427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Emery S, Kim Y, Choi YK, Szczypka G, Wakefield M, Chaloupka FJ. The effects of smoking-related television advertising on smoking and intentions to quit among adults in the United States: 1999–2007. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(4):751–757. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2011.300443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Results from the 2013 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National Findings, NSDUH Series H-48, HHS Publication No. (SMA) 14–4863. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Thun MJ, Carter BD, Feskanich D, et al. 50-Year trends in smoking-related mortality in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(4):351–364. doi:10.1056/NEJMsa1211127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. General S. Preventing Tobacco Use Among Youth and Young Adults. Atlanta, GA: Dep Health Hum Serv Cent Dis Control Prev; 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. van Hasselt M, Kruger J, Han B, et al. The relation between tobacco taxes and youth and young adult smoking: what happened following the 2009 U.S. federal tax increase on cigarettes?Addict Behav. 2015;45(45):104–109. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.01.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Center for Tobacco Products. Compliance, Enforcement & Training - Tobacco Control Act Overview. www.fda.gov/TobaccoProducts/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/ucm298595.htm Accessed October 24, 2015

- 30. Terry-McElrath YM, O’Malley PM. Trends and timing of cigarette smoking uptake among US young adults: survival analysis using annual national cohorts from 1976 to 2005. Addict Abingdon Engl. 2015;110(7):1171–1181. doi:10.1111/add.12926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Elders MJ, Perry CL, Eriksen MP, Giovino GA. The report of the Surgeon General: preventing tobacco use among young people. Am J Public Health. 1994;84(4):543–547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lassiter MD. Impossible criminals: the suburban imperatives of America’s war on drugs. J Am Hist. 2015;102(1):126–140. doi:10.1093/jahist/jav243. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Edwards R, Carter K, Peace J, Blakely T. An examination of smoking initiation rates by age: results from a large longitudinal study in New Zealand. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2013;37(6):516–519. doi:10.1111/1753–6405.12105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Gifford H, Tautolo el-S, Erick S, Hoek J, Gray R, Edwards R. A qualitative analysis of Māori and Pacific smokers’ views on informed choice and smoking. BMJ Open. 2016;6(5):e011415. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2016–011415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Gray RJ, Hoek J, Edwards R. A qualitative analysis of informed choice among young adult smokers. Tob Control. 2016;25(1):46–51. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014–051793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ajdacic-Gross V, Landolt K, Angst J, et al. Adult versus adolescent onset of smoking: how are mood disorders and other risk factors involved?Addiction. 2009;104(8):1411–1419. doi:ADD2640 [pii] 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02640.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Breslau N. Daily cigarette consumption in early adulthood: age of smoking initiation and duration of smoking. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1993;33(3):287–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Khuder SA, Dayal HH, Mutgi AB. Age at smoking onset and its effect on smoking cessation. Addict Behav. 1999;24(5):673–677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Thompson AB. Smoking initiation after marriage and parenting among Black and White women. Am J Health Behav. 2014;38(4):577–585. doi:10.5993/AJHB.38.4.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Skinner ML, Haggerty KP, Catalano RF. Parental and peer influences on teen smoking: Are White and Black families different?Nicotine Tob Res. 2009;11(5):558–563. doi:10.1093/ntr/ntp034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Clark PI, Scarisbrick-Hauser A, Gautam SP, Wirk SJ. Anti-tobacco socialization in homes of African-American and white parents, and smoking and nonsmoking parents. J Adolesc Health. 1999;24(5):329–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ellickson PL, Perlman M, Klein DJ. Explaining racial/ethnic differences in smoking during the transition to adulthood. Addict Behav. 2003;28(5):915–931. doi:S0306460301002854 [pii]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Garcia Coll CT, Meyer EC, Brillon L. Ethnic and minority parenting. In: Bornstein Marc H. (ed) Handbook of Parenting, Vol. 2: Biology and Ecology of Parenting. Hillsdale, England: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc;1995:189–209. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Friedman SR, Cooper HL, Osborne AH. Structural and social contexts of HIV risk Among African Americans. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(6):1002–1008. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2008.140327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Burston BW, Jones D, Robertson-Saunders P. Drug use and African Americans: myth versus reality. J Alcohol Drug Educ. 1995;40(2):19–39. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Curtis R. The improbable transformation of inner-city neighborhoods: Crime, violence, drugs, and youth in the 1990s. J Crim Law Criminol. 1998;88(4):1233–1276. doi:10.2307/1144256. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Flom PL, Friedman SR, Jose B, Curtis R. Peer norms regarding drug use and drug selling among household youth in a low-income drug supermarket urban neighborhood. Drugs Educ Prev Policy. 2001;8(3):219–232. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Jackson CL, Hu FB, Kawachi I, Williams DR, Mukamal KJ, Rimm EB. Black-white differences in the relationship between alcohol drinking patterns and mortality Among US men and women. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(Suppl 3):S534–43. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2015.302615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Kandel DB, Kiros GE, Schaffran C, Hu MC. Racial/ethnic differences in cigarette smoking initiation and progression to daily smoking: a multilevel analysis. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(1):128–135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Vital signs: current cigarette smoking among adults aged ≥18 years with mental illness - United States, 2009–2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62(5):81–87. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]