Abstract

Introduction

No studies have examined the longitudinal relationship between e-cigarette use and elevated depressive symptoms among young adults. The main objective of the current study was to establish a potential bi-directional relationship between e-cigarette use and elevated depressive symptoms among college students in Texas, across a 1 year period of time.

Methods

A survey of 5445 college students in Texas was conducted with 6-month and 1-year follow-ups. A longitudinal cross-lagged model was used to simultaneously examine the bi-directional relationships between current, or past 30-day, e-cigarette use and elevated depressive symptoms across the three study waves. Depressive symptoms were measured using a 10-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) with a cutpoint of ≥ 10 to measure elevated depressive symptoms. Covariates included baseline age, gender, college type (2- or 4-year), and other alternative tobacco products used.

Results

E-cigarette use did not predict elevated depressive symptoms at 6-month and 1-year follow-ups. However, depressive symptoms predicted e-cigarette use at both 6-month and 1-year follow-ups.

Conclusions

The current study indicates that depressive symptoms predict subsequent e-cigarette use and not vice versa. Future studies are needed to replicate current findings and also further establish the mechanisms for causality, which could inform Food and Drug Administration regulatory planning.

Implications

There has been recent evidence for cross-sectional associations between e-cigarette use and elevated depressive symptoms and mental health problems. There have been no studies examining these associations using longitudinal designs. This study established a temporal relationship, such that elevated depressive symptoms predicted e-cigarette use 6 months later among college students. Future research is needed to establish the mechanisms of association as well as causality.

Introduction

To date, only two studies have examined the association between e-cigarette use and depressive symptoms or poor mental health symptoms.1,2 One national cross-sectional study by Cummins and colleagues2 found that persons with poor mental health symptoms were more likely to use e-cigarettes than persons without poor mental health symptoms. In another population-based study of college students in Texas, Bandiera and colleagues found a positive association between e-cigarette use and elevated depressive symptoms.1 Because the only two studies establishing an association between e-cigarette use and mental health problems are cross-sectional1,2 it is not possible to disentangle the direction of effects between e-cigarette use and depressive symptoms. Rather, longitudinal studies among general populations, such as college students, are needed to determine if depressive symptoms lead to the use of e-cigarettes and/or if e-cigarette use leads to elevated levels of depressive symptoms.

The association between cigarette use and depression is well established. However, the exact nature of this association is not clear. It is possible that persons with mental health problems smoke cigarettes to alleviate their poor mental health symptoms and therefore “self-medicate,”3 and it is possible that the use of cigarettes predicts the onset of depression.4 Studies in rodents have suggested that administration of nicotine during adolescence leads to depression in adulthood, thus nicotine may be a mechanism linking cigarette smoking to depression.5 Despite a lack of understanding of the exact etiology, it is reasonable to hypothesize that use of nicotine delivering devices, including e-cigarettes, may be associated with elevated levels of depressive symptoms.

The purpose of the present study was to examine the longitudinal associations between e-cigarette use and elevated depressive symptoms among college students in Texas. We expected that the associations between e-cigarette use and depressive symptoms would be analogous to those for cigarette use and depressive symptoms. Thus, “we hypothesized that there would be bi-directional associations, such that e-cigarette use would predict subsequent elevated depressive symptoms and elevated depressive symptoms would predict subsequent e-cigarette use.”

Methods

Participants

Participants were 5445 young adult students drawn from the first three waves of the Marketing and Promotions across Colleges in Texas project (Project M-PACT). Project M-PACT, a rapid response surveillance study, includes a cohort of 5482 18–29 year old students who were initially assessed in November, 2014–February, 2015 and every 6 months thereafter for two subsequent waves (waves 2 and 3). Of the 5482 students, 79% participated again at wave 2 (n = 4326) and wave 3 (n = 4321). The 5445 students in this study were initially 18–29 years old, averaged 20.5 years of age at wave 1, and almost two-thirds were women (63.8%). Regarding race/ethnicity, students were primarily non-Hispanic white and Hispanic/Latino, with small proportions reporting African American/Black, Asian, another race/ethnicity or two or more races/ethnicities (see Table 1 for socio-demographic and other descriptive information). The present study excludes data from an additional 37 students who were missing data on the wave 1 socio-demographic variables and on the other tobacco products variable.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for All Study Variables by Data Collection Wave

| Wave 1 | Wave 2 6 months after wave 1 | Wave 3 12 months after wave 1 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 5445) | (n = 4303) | (n = 4293) | |

| Mean age (SD) | 20.5 (2.4) | 20.4 (2.3) | 20.5 (2.3) |

| % Female | 63.8 | 64.4 | 64.5 |

| % White | 36.3 | 35.9 | 35.9 |

| % Four-year college | 92.6 | 93.2 | 93.3 |

| % Number of other tobacco products used | |||

| 0 | 67.1 | 72.3 | 72.7 |

| 1 | 19.9 | 18.4 | 18.7 |

| 2 | 9.3 | 7.1 | 6.6 |

| 3 | 3.1 | 1.7 | 1.7 |

| 4 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.4 |

| % Current (past-month) e-cigarette use | 17.0 | 14.5 | 12.3 |

| % Past week high depressive symptoms | 30.9 | 23.7 | 33.1 |

Procedure

Participants were recruited from 24 colleges located in the five counties surrounding Austin, Dallas/Fort Worth, Houston, and San Antonio, Texas. To enroll in the project, participants were required to be 18–29 years old and full- or part-time degree- or certificate- seeking undergraduate students attending a 4-year college or a vocational/technical program at a 2-year college (see6). More than 13 000 students (n = 13 714) were eligible to participate in the study and of these, 40% (n = 5482) provided consent and completed the baseline online survey.

Measures

Socio-Demographic Covariates.

Sex (0 = male; 1 = female), age, type of college (0 = 2-year; 1 = 4-year), and race/ethnicity (coded as white, Hispanic or Latino/a, black or African American, Asian, American Indian or Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander, and other race/ethnicity or more than one race/ethnicity).

Current Other Tobacco Use.

Use of four types of tobacco products at wave 1, besides e-cigarettes, was included as covariate in the present study. The items were adapted from the Youth Tobacco Survey7 and the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health Study,8 and assessed current or past 30-day use of cigarettes, smokeless/snus tobacco, large cigars/cigarillos/little cigars, and hookah. Participants reporting use of a product on one or more days in the past 30 days were given a score of 1 for that product. Scores for the four items were summed to create an index of the number of other tobacco products used in past 30 days (range = 0–4).

Current E-Cigarette Use.

Current use of e-cigarette use was assessed with the question “During the past 30 days, have you used any ENDS product (ie, an e-cigarette, vape pen, or e-hookah), even one or two puffs, as intended (ie, with nicotine cartridges and/or e-liquid/e-juice)?” The item was scored 0 (used on 0 days in the past 30 days) or 1 (used on 1 or more days in the past 30 days). The item was adapted from the Youth Tobacco Survey7 and the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) Study.8

Depressive Symptoms.

Depressive symptoms were assessed with the 10-item short-form Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression 10 Scale (CES-D 10).9 This scale assesses frequency of symptoms of depression occurring over the past week, including depressed affect, positive affect, and somatic complaints. Each of the items is scored on a scale from 0 “rarely (less than 1 day)” to 3 “most of the time (5–7 days).” The 10 items were summed and higher scores reflected higher levels of depressive symptoms. A cutoff score of 10 was used to create two groups; one that reported clinically significant symptoms of a depression (score of 10 or more) and one that did not (score of 9 or less). The CES-D 10 is a reliable and valid measure of depressive symptoms for community-based adolescents10 and older adults.9 For the present sample, internal consistency reliability was 0.81.

Data Analysis

A three-panel cross-lagged panel analysis was used to examine the bi-directional associations between current e-cigarette use and depressive symptoms across three study waves (see Figure 1). Analyses were conducted in Mplus 7.3 using the Weighted Least Squares with Mean and Variance adjustment estimation procedure, which is the best option for modeling categorical data and, which accommodates missing data. However, participants missing information on the exogenous socio-demographic covariates of age, gender, race/ethnicity, school type (2-year vs. 4-year), and number of other products used during the past 30 days were excluded from analysis (n = 37), leaving a final sample size of 5445. To account for the nested data structure (ie, students nested within colleges), college was included as a clustering variable.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model showing the cross-lagged associations between current e-cigarette use and depressive symptoms across three study waves, with 6 months between each wave.

To test the hypothesized model in Figure 1, we estimated 10 paths from each of the socio-demographic and number of past 30-day tobacco use covariates to baseline e-cigarette use and depression. Cross-lagged associations were assessed with direct paths from e-cigarette use to depression in the subsequent wave (6 months later) and from depression to e-cigarette use in the subsequent wave (6 months later). Four stability paths from each variable to their respective subsequent follow-up outcome variables (eg, wave 1 depressive symptoms to wave 2 depressive symptoms) were also included. Thus, findings for the cross-lagged paths can be interpreted as being over and above the influence of the stability paths. Finally, covariances were estimated between e-cigarette use and depressive symptoms within each wave to account for potential cross-sectional relationships between the variables.

Results

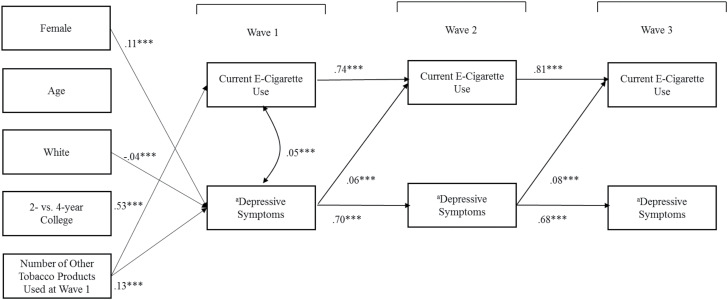

As shown in Table 1, between 23.7% and 33.1% of participants reported a score of 10 or more on the CES-D across the three study waves. Similarly, 12.3%–14.5% of participants reported current e-cigarette use. Figure 2 shows the results from the cross-lagged path analysis of the associations between current e-cigarette use and depressive symptoms. Four of the ten paths from each of the exogenous covariates to the wave 1 depressive symptoms and wave 1 e-cigarette use variables were significant (gender to depression; race/ethnicity to depression; number of tobacco products used to depressive symptoms and to e-cigarette use). Of the three within-wave covariances, only the covariance between wave 1 depressive symptoms and wave 1 e-cigarette use was significant. In addition, all four stability paths were positive and significant, indicating that e-cigarette use and depression were predictive of their respective constructs 6 months later. The strongest associations were observed for the cross-time stability of e-cigarette use (β = 0.74–0.81, p < .01), followed by the cross-time stability of depressive symptoms (β = 0.68–0.70, p < .01). Despite inclusion of the covariates and the large stability paths, two of the four cross-lagged paths were significant: the paths from baseline depressive symptoms to wave 2 current e-cigarette use (β = 0.06, p < .01) and from wave 2 depressive symptoms to wave 3 e-cigarette use (β = 0.08, p < .01). These findings indicate that high levels of depressive symptoms predict e-cigarette use 6 months later, but e-cigarette use does not predict high levels of depressive symptoms.

Figure 2.

Cross-lagged path model examining bidirectional associations between current e-cigarette use and depressive symptoms among college students across three study waves, with 6 months between each wave. X2(5445) = 114.854, p < .001.; CFI = 0.962; TLI = 0.929; RMSEA = 0.026. Estimates are from completely standardized solution (STDYX). Only significant paths are shown. aRecoded into a dichotomous scale = scores of 1–9 and 1 = scores of 10 or more. ***p < .01.

Discussion

This is the first study to establish a longitudinal relationship between elevated depressive symptoms and e-cigarette use. We found that elevated depressive symptoms predicted e-cigarette use 6 months later among a young adult college population, even after controlling for a variety of socio-demographics and number of tobacco products used. However, we found no evidence that e-cigarette use predicted elevated depressive symptoms. Despite the high levels of stability across time of depressive symptoms and e-cigarette use (betas > 0.70), depressive symptoms were robust predictors of subsequent e-cigarette use 6 months later.

The current study conceptually replicates the two cross-sectional studies indicating a positive association between e-cigarette use and elevated depressive symptoms and mental health problems, and extends these studies by establishing temporality. Contrary to what was hypothesized, e-cigarette use did not predict elevated depressive symptoms; and thus, depression may not be the result of e-cigarette use. It should be noted that we did not know the nicotine content or amount in the e-cigarettes, because this was not measured in the current study. However, since e-cigarettes typically deliver less nicotine per puff than cigarettes,11 it is possible that the lower content of nicotine in e-cigarettes could explain the null findings.

There may be several explanations for why elevated depressive symptoms predicted e-cigarette use. First, college students may be using e-cigarettes to temporarily alleviate mental distress and therefore “self-medicate” as has been shown with cigarette smoking.12 Another possibility is that college students with elevated levels of depressive symptoms may be using e-cigarettes as a smoking cessation device to quit smoking cigarettes.

Although the current analysis is based on a large study, the findings must be interpreted with caution. First, the current study only sampled college students in Texas and thus future studies should replicate our findings in the general young adult population. Second, although the CES-D9 is widely used, well validated, and reliable, it does not provide a clinical diagnosis of depression. Despite these limitations, our findings are unique and important because they indicate that even after controlling for all types of tobacco products used and a variety of socio-demographics, elevated depressive symptoms predicted e-cigarette use. As the FDA is now regulating all forms of tobacco and nicotine products, they are particularly interested in understanding etiological associations with e-cigarette use as well as vulnerable populations such as depressed persons and special populations such as young adults and college students. Nonetheless, future research is needed to also explore the mechanisms that lead depressed persons to use e-cigarettes. When the consequences or benefits of e-cigarette use among depressed college students are established, then this may inform FDA regulatory action as well as other policymakers and healthcare providers who serve depressed college students and young adults. This knowledge can also inform policy action and behavioral interventions taken at universities and healthcare settings such as in mental health and pediatric treatment to optimize the health of college students.

Funding

Research reported in this publication was supported by grant number [1 P50 CA180906] from the National Cancer Institute and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Center for Tobacco Products. Frank Bandiera is also a recipient of an early career award from Robert Wood Johnson Foundation New Connections Program.

Declaration of Interests

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH or the FDA. The authors have no conflicts to disclose.

References

- 1. Bandiera FC, Loukas A, Wilkinson AV, Perry CL. Associations between tobacco and nicotine product use and depressive symptoms among college students in Texas. Addict Behav. 2016;63:19–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cummins SE, Zhu SH, Tedeschi GJ, Gamst AC, Myers MG. Use of e-cigarettes by individuals with mental health conditions. Tob control. 2014;23(suppl 3):iii48–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gehricke JG, Loughlin SE, Whalen CK, et al. Smoking to self-medicate attentional and emotional dysfunctions. Nicotine Tob Res. 2007;9(suppl 4):S523–S536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Boden JM, Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ. Cigarette smoking and depression: tests of causal linkages using a longitudinal birth cohort. Br J Psychiatry. 2010;196(6):440–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Iñiguez SD, Warren BL, Parise EM, et al. Nicotine exposure during adolescence induces a depression-like state in adulthood. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;34(6):1609–1624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Loukas A, Chow S, Pasch KE, et al. College students’ polytobacco use, cigarette cessation, and dependence. Am J Health Behav. 2016;40(4):514–522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Starr G, Rogers T, Schooley M, Porter S, Wiesen E, Jamison N. Key Outcome Indicators for Evaluating Comprehensive Tobacco Control Programs. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 8. National Institutes of Health. Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health 2015. https://pathstudyinfo.nih.gov/UI/HomeMobile.aspx Accessed August 31, 2015.

- 9. Andresen EM, Malmgren JA, Carter WB, Patrick DL. Screening for depression in well older adults: evaluation of a short form of the CES-D (Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale). Am J Prev Med. 1994;10(2):77–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bradley KL, Bagnell AL, Brannen CL. Factorial validity of the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression 10 in adolescents. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2010;31(6):408–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Schroeder MJ, Hoffman AC. Electronic cigarettes and nicotine clinical pharmacology. Tob control. 2014;23(suppl 2):ii30–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Prochaska JJ. Smoking and mental illness–breaking the link. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(3):196–198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]