Abstract

Introduction

This study replicated and extended results of a previous trial, which found that combination varenicline/bupropion treatment increased smoking abstinence in smokers who were male, highly dependent, and who did not respond to prequit nicotine patch treatment with a >50% reduction in expired-air carbon monoxide in the first week.

Methods

One hundred and twenty-two male nicotine patch nonresponders and 52 responders were identified. Smokers in each group were randomized to receive 12 weeks of varenicline plus bupropion treatment versus varenicline plus placebo. The primary outcome was continuous smoking abstinence at weeks 8–11 after the target quit date.

Results

For smokers with a high level of dependence, judged by having a baseline Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND) score ≥ 6 and cigarette consumption ≥ 20/d, combination varenicline/bupropion treatment increased the abstinence rate relative to varenicline alone: 71.0% versus 43.8% (odds ratio = 3.14; 95% confidence interval = 1.11–8.92, p [one tailed] = .016). In contrast, less dependent smokers did not show a benefit of combination treatment relative to varenicline (abstinence rates of 32.1% vs. 45.6%, respectively); there was a significant interaction of treatment and dependence level. Patch nonresponders tended to benefit the most from combination treatment, which was well tolerated overall.

Conclusions

Combination varenicline/bupropion treatment proved significantly more efficacious than varenicline alone among highly dependent male smokers. These results, together with prior studies, support an adaptive treatment paradigm that assigns smoking cessation treatment according to baseline smoker characteristics and initial response to nicotine patch treatment.

Implications

This study replicated, in a prospective manner, an important and surprising retrospective finding from a previous clinical trial, which showed that a specific subpopulation of smokers benefited substantially from receiving a combination treatment of varenicline plus bupropion, relative to varenicline plus placebo. Specifically, male smokers having high baseline nicotine dependence (FTND score ≥ 6 and cigarette consumption ≥ 20/d), showed a marked increase in smoking abstinence rate on combination pharmacotherapy. The present study likewise found an enhancement in end-of-treatment abstinence rate in this subgroup, from 43.8% to 71.0%. The adaptive treatment paradigm, which classifies smokers based on initial dependence level and response to prequit nicotine patch treatment, may be used to identify target populations of smokers whose success can be enhanced by intervening with combination pharmacotherapy before the quit-smoking date.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01806779.

Introduction

Despite efforts to reduce the prevalence of cigarette smoking in the United States, the estimated annual toll of premature death from smoking stands at 540,000 deaths/y.1 Current pharmacotherapies generally yield only 10%–25% abstinence rates 1 year after treatment,2 and thus, more effective smoking cessation treatments are urgently needed.

We have previously reported3,4 a promising adaptive treatment approach that (1) identifies smokers who are unlikely to succeed with nicotine replacement alone and (2) provides alternative treatments for these individuals. In this approach, nicotine patch treatment is initiated 2 weeks prior to a target quit date, and based on the reduction in ad libitum smoking during the first week of prequit patch treatment, smokers are classified as patch “responders” or “nonresponders,” according to whether their expired-air carbon monoxide (CO) decreases by >50% or ≤50%. Responders are allowed to remain on the patch, while nonresponders are switched to an alternative treatment, such as bupropion and varenicline.

In one study, we found that approximately 10% of nicotine patch nonresponders who would have failed to quit smoking could be rescued by switching them from nicotine patch treatment to varenicline or augmenting their nicotine patch treatment with bupropion sustained-release.3 In a follow-up study using a similar adaptive treatment algorithm,4 combination varenicline/bupropion proved more efficacious than varenicline alone as a rescue treatment for subpopulations of patch nonresponders, specifically male smokers and highly dependent smokers (assessed by a baseline Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence [FTND] score ≥ 6 or baseline cigarette consumption ≥ 20/d). Ebbert et al.5 also reported that highly dependent smokers showed significantly higher abstinence rates using combination varenicline/bupropion treatment than with varenicline alone.

In the current study, we sought to replicate the superior efficacy of combination varenicline/bupropion treatment versus varenicline in a sample of male smokers who were classified as nicotine patch nonresponders. In addition, we sought to replicate the previously observed relationship between the efficacy of varenicline/bupropion treatment and baseline nicotine dependence. Finally, unlike the previous study that only randomized patch nonresponders to the two treatments, in this study, we also compared treatment outcomes among nicotine patch responders.

Methods

Study Design

This double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-arm trial, randomly assigned smokers to receive varenicline plus bupropion sustained-release or varenicline plus placebo treatments. Prior to randomization, all participants received precessation nicotine patch treatment and were instructed to smoke as little or as much as they wished during the first week. Participants were categorized as patch responders or nonresponders based on whether their end-expired-air CO concentrations showed a >50% decrease at the end of this week.

Study Procedures

The study was approved by the Duke University Medical Center Institutional Review Board. Adult smokers were eligible if they were 18–65 years of age, reported smoking an average of ≥10 cigarettes/d for three cumulative years, and displayed end-expired-air CO ≥ 10 ppm. After a history, physical exam and laboratory evaluation, written informed consent was obtained from participants, who were compensated up to $350 for study participation.

After screening and enrollment, participants visited the research center weekly for 2 weeks before the quit date and at four sessions held 1, 3, 7, and 11 weeks after the quit date. Brief (<15 minutes) support was provided at each session. At each session, clinical trial materials were dispensed, smoking diaries were collected, and expired-air CO were measured.

After the first week of prequit nicotine patch treatment, all patch nonresponders received varenicline pills and were additionally randomized to taking either bupropion sustained-release tablets or placebo tablets that were identical in appearance. The recommended dosing titration schedule was used for both varenicline (0.5 mg once daily on days 1–3, 0.5 mg twice daily on days 4–7, followed by 1 mg twice daily through 12 weeks) and for bupropion (150 mg daily for 3 days, followed by 150 mg twice daily through 12 weeks).

Initial nicotine patch dosing was based on initial expired-air CO reading; participants with CO > 30 ppm at baseline received 42 mg/d (two 21 mg/d patches, the first applied in the morning and the second at noon), and the remaining participants wore a single 21 mg/d patch applied each morning. This personalized dosing regimen was based on previous research.6

Dose reductions for medications were allowed in the event of adverse effects. Adverse effect ratings were collected at each session using 7-point rating scales. Questionnaires assessing smoking withdrawal symptoms, nicotine dependence, and rewarding effects of smoking were also administered.

Statistical Analyses

The primary dependent measure was continuous 4-week abstinence assessed during weeks 8–11 after the target quit-smoking date. Abstinence was defined as a self-report of not smoking confirmed by expired-air CO < 10 ppm. Dropouts were considered to be nonabstinent, an assumption supported by previous studies.7

To evaluate the hypothesis that combination varenicline plus bupropion treatment would enhance abstinence rates over varenicline plus placebo, for highly dependent nicotine patch nonresponders (ie, those having an FTND score ≥ 6 and baseline cigarettes/d ≥ 20), logistic regression was used to compare the two treatments on abstinence outcomes. A one-tailed comparison (alpha = 0.05) was specified a priori, in view of the clear prediction based on the previously published study.4

Additional exploratory analyses examined abstinence outcomes in all subjects, using a logistic regression model that included the following terms: Treatment (varenicline plus bupropion sustained-release, varenicline plus placebo), Dependence (high, low), Patch responder category (responder, nonresponder), and all two- and three-way interactions between these factors.

The incidence of adverse effects was tabulated and compared between treatment conditions using Fisher’s exact test. In view of the potentially large Type II error rate if a correction for multiple comparisons were to be made, no correction was made. Additionally, the large Type I error accompanying a large number of side effect comparisons implies that p values were interpreted with caution and primarily used to “flag” potential symptoms for future study.8

Statistical Power

The initial study design entailed recruiting and randomizing 160 male patch nonresponders; however, funding for the project ended before this target recruitment was completed, and therefore, results were analyzed for subjects enrolled prior to study termination (N = 173, including 121 patch nonresponders and 52 patch responders. One additional subject was found to have received the incorrect medication assignment on some sessions and was censored from the analyses, but this did not affect the conclusion).

The sample size of 121 patch nonresponders yielded approximately 78% for detecting an overall enhancement in 4-week continuous abstinence from 20% (varenicline plus placebo) to 40% (varenicline plus bupropion). For the subgroup of male patch nonresponders with high dependence, the prior study showed an enhancement in abstinence rate from 14% to 61%; the present study, with 43 high dependence patch nonresponders, had a power greater than 90% to replicate this effect.

Results

Participant Disposition and Characteristics

The CONSORT chart (Supplementary Figure S1) describes the disposition of participants. Of 399 smokers screened, 197 participants were entered into the study. Twenty-three subjects withdrew from the study prior to randomization, leaving 174 participants who received the assigned treatment conditions (122 nicotine patch nonresponders and 52 responders). There was no relationship between discontinuation of treatment and treatment condition (28.6% in varenicline plus bupropion condition vs. 25.8% in varenicline plus placebo condition).

The demographic characteristics and smoking histories of participants were similar across the treatment conditions (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline Participant Characteristics

| Characteristics | Varenicline + bupropion | Varenicline + placebo |

|---|---|---|

| n = 84 | n = 90 | |

| Age, mean (SD) | 43.1 (10.6) | 44.8 (11.4) |

| Men, n (%) | 84 (100) | 90 (100) |

| Race, n (%) | ||

| White | 57 (67.9) | 66 (73.3) |

| Black | 26 (31.0) | 20 (22.2) |

| Other | 1 (1.2) | 4 (4.4) |

| Number of years smoked, mean (SD) | 23.1 (10.6) | 24.4 (11.1) |

| Number of cigarettes/d, mean (SD) | 20.2 (7.7) | 19.8 (7.1) |

| FTND score, mean (SD) | 5.6 (1.8) | 5.4 (1.9) |

| Number of prior attempts to quit, mean (SD) | 8.6 (15.4) | 9.8 (18.2) |

| Expired-air CO (ppm), mean (SD) | 28.2 (12.0) | 27.3 (10.8) |

| Number of participants (%) having CO > 30 ppm (42-mg patch dose wk 1) | 29 (34.5) | 30 (33.3) |

FTND = Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence.

Efficacy

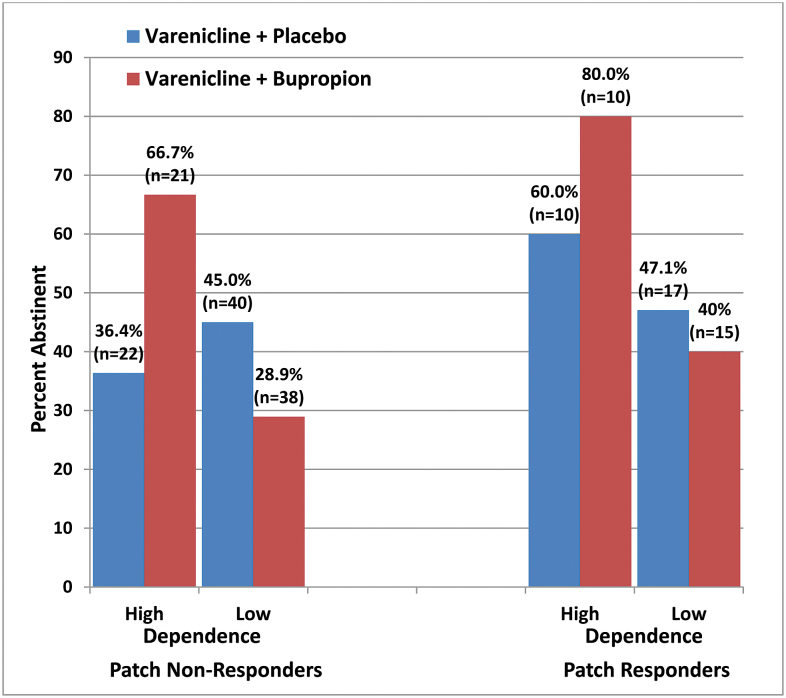

For the group of nicotine patch nonresponders, the analysis of weeks 8–11 abstinence showed no overall effect of combination treatment versus monotherapy. However, for the subgroup of nicotine patch nonresponders with high nicotine dependence, combination varenicline plus bupropion treatment yielded a significantly higher abstinence rate than varenicline alone: 66.7% versus 36.4% (odds ratio = 3.50, 95% confidence interval = 1.00–12.29, p [one tailed] = .025). For all subjects with high dependence (including both patch responders and nonresponders), combination treatment significantly increased the abstinence rate relative to varenicline alone (odds ratio = 3.14, 95% confidence interval = 1.11–8.92, p [one tailed] = .016). The overall logistic regression model showed a two-way interaction between Dependence level and Treatment (p = .03, two tailed), indicating that treatment efficacy was moderated by dependence level. Figure 1 depicts the abstinence rates in the various subgroups and shows the substantial differential effect of combination treatment in highly dependent smokers as well as a nonsignificant trend for a greater effect in patch nonresponders.

Figure 1.

End-of-treatment (weeks 8–11 postquit date) abstinence rates by treatment condition, patch responder status, and dependence level (high = Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence [FTND] score ≥ 6 and baseline cigarettes/d ≥ 20).

Safety, Tolerability, and Compliance

One serious adverse event thought likely to be related to medication condition occurred in the varenicline plus bupropion condition; the participant suffered an allergic reaction accompanied by swelling of the tongue and throat and shortness of breath. Symptoms resolved on discontinuation of study medications. Five other serious adverse events were considered not likely to be related to study medication based on detailed investigation of the surrounding circumstances.

Other adverse events occurring in greater than 5% of the participants in either condition are listed in Supplementary Table S1, although most did not interfere with continuing treatment. A total of 15 subjects in the varenicline plus placebo condition and 9 subjects in the varenicline plus bupropion condition had dose reductions at some point during treatment. Only two participants discontinued medications due to adverse effects that were considered likely related to treatment (one in the varenicline condition due to insomnia and one in the varenicline plus bupropion condition due to the above-mentioned allergic reaction). No differences between conditions reached statistical significance, with the exception of “change in taste,” which occurred more often in the varenicline plus bupropion condition (Fisher’s exact p = .002).

Based on daily diary counts, compliance was fairly high, with 85.1% of the total number of oral medication doses taken in the varenicline plus bupropion condition and 79.2% of doses taken in the varenicline plus placebo condition. Nicotine patch compliance in week 1 was also high, averaging 86.1% of patches worn. There were no significant differences as a function of level of dependence or patch responder status.

Discussion

The study results provided a replication of our previous finding of a substantially superior efficacy of varenicline/bupropion treatment for highly dependent male smokers, particularly among nicotine patch nonresponders, that is, individuals who do not respond with greater than 50% reduction in ad libitum smoking during the first week of prequit date nicotine patch treatment. We speculate that nicotine patch nonresponders may show a greater benefit from the addition of bupropion to varenicline treatment because both nicotine and varenicline act on high-affinity nicotinic receptors, whereas bupropion and its metabolites have an additional mechanism of action that includes enhancing dopaminergic and noradrenergic transmission through blocking neurotransmitter reuptake at the synapse.9,10 This speculation is tempered by the absence of a statistically significant three-way interaction between Treatment, Dependence, and Patch responder status in the relatively small sample of the current study. However, the significant two-way interaction between Dependence and Treatment found in this study is consistent with that observed in two previous clinical trials.4, 5 Dependence has been linked to a deficit in striatal dopamine receptors11, 12 that may be relevant to nicotine dependence as well as to the therapeutic action of bupropion. Male smokers also show a deficit in striatal dopamine transmission that may be relevant to bupropion’s efficacy.13 Further research will be needed to determine whether the interaction of combination varenicline/bupropion treatment with level of dependence holds in female smokers and in patch responders.

The index of nicotine patch responsiveness used in the current study was the percent decrease in expired-air CO. However, the decrease in the number of cigarettes smoked per day also shows a strong relationship to abstinence outcomes.3 Thus, the present findings may be translated into clinical environments where CO monitoring may not be feasible, using a simple self-report of cigarettes smoked per day.

In summary, the present results, along with previous studies, reinforce the conclusion that combination varenicline/bupropion treatment can substantially benefit specific subpopulations of smokers, particularly smokers who exhibit high levels of nicotine dependence. For these smokers, the enhancement in abstinence rate was substantial, from 43.8% to 71.0% (averaging across patch responders and nonresponders). In our previous study4 of patch nonresponders, a substantial enhancement in abstinence rate was also seen for the subgroup with a high level of dependence. Thus, a readily identifiable fraction of the smoking population seeking treatment could potentially obtain a substantial benefit from combination varenicline/bupropion treatment.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary data are available at Nicotine & Tobacco Research online.

Funding

This study was supported by grant 1P50 DA027840 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse and a grant from Philip Morris, USA. The sponsors had no role in the planning or execution of the study, data analysis, or publication of results.

Declaration of Interests

The authors disclose consulting and patent purchase agreements with Philip Morris International relating to reduced risk tobacco products.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Many members of the Duke Center for Smoking Cessation contributed to the successful completion of the research described in this report. In particular, the authors acknowledge the invaluable assistance of Susan Claerhout, Tanaia Loeback, Amanda Mitchell, Wendy Roberts, Al Salley, Michael Siernos, Kay Scime, and Eric Westman in supervising the conduct of this study. Active bupropion sustained-release and placebo tablets were supplied by Murty Pharmaceuticals, Inc (Lexington, KY), under contract from the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

References

- 1. Carter BD, Freedman ND, Jacobs EJ. Smoking and mortality—beyond established causes. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(22):2170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gonzales D, Rennard SI, Nides M, et al. ; Varenicline Phase 3 Study Group Varenicline, an alpha4beta2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor partial agonist, vs sustained-release bupropion and placebo for smoking cessation: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2006;296(1):47–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rose JE, Behm FM. Adapting smoking sessation treatment according to initial response to precessation nicotine patch. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(8):860–867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rose JE, Behm FM. Combination treatment with varenicline and bupropion in an adaptive smoking cessation paradigm. Am J Psychiatry. 2014;171(11):1199–1205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ebbert JO, Hatsukami DK, Croghan IT, et al. Combination varenicline and bupropion SR for tobacco-dependence treatment in cigarette smokers: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2014;311(2):155–163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dale LC, Hurt RD, Offord KP, Lawson GM, Croghan IT, Schroeder DR. High-dose nicotine patch therapy. Percentage of replacement and smoking cessation. JAMA. 1995;274(17):1353–1358. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Foulds J, Stapleton J, Hayward M, et al. Transdermal nicotine patches with low-intensity support to aid smoking cessation in outpatients in a general hospital. A placebo-controlled trial. Arch Fam Med. 1993;2(4):417–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. ICH Harmonised Tripartite Guideline. Statistical principles for clinical trials. International Conference on Harmonisation E9 Expert Working Group. Stat Med. 1999;18(15):1905–1942. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Damaj MI, Carroll FI, Eaton JB, et al. Enantioselective effects of hydroxy metabolites of bupropion on behavior and on function of monoamine transporters and nicotinic receptors. Mol Pharmacol. 2004;66(3):675–682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Paterson NE, Balfour DJ, Markou A. Chronic bupropion attenuated the anhedonic component of nicotine withdrawal in rats via inhibition of dopamine reuptake in the nucleus accumbens shell. Eur J Neurosci. 2007;25(10):3099–3108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dagher A, Bleicher C, Aston JA, Gunn RN, Clarke PB, Cumming P. Reduced dopamine D1 receptor binding in the ventral striatum of cigarette smokers. Synapse. 2001;42(1):48–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fehr C, Yakushev I, Hohmann N, et al. Association of low striatal dopamine d2 receptor availability with nicotine dependence similar to that seen with other drugs of abuse. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(4):507–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Brown AK, Mandelkern MA, Farahi J, et al. Sex differences in striatal dopamine D2/D3 receptor availability in smokers and non-smokers. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2012;15(7):989–994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.