Abstract

Introduction

This study examined the relationships between experiences of childhood and adulthood victimization and current smoking among heterosexual and sexual minority women. The main hypothesis was that victimization experiences would predict current smoking status. Further, we hypothesized that the effect of childhood victimization on self-reported smoker status would be mediated by adult victimization.

Methods

Data are from two studies conducted in the United States that used similar methods and questionnaires in order to conduct a comparative analysis of women based on sexual orientation. Data from Wave 1 (2000–2001) of the Chicago Health and Life Experiences of Women (CHLEW) study and from Wave 5 (2001) of the National Study of Health and Life Experiences of Women (NSHLEW) study were used in these analyses.

Results

Twenty-eight percent of the sample reported current smoking. Victimization experiences were common, with 63.4% of participants reporting at least one type of victimization in childhood and 40.2% reporting at least one type in adulthood. Women who identified as heterosexual were less likely to be victimized during childhood than were women who identified as lesbian or bisexual. Adult victimization had a significant effect on current smoker status, and the effect of childhood victimization on smoker status was mediated by adult victimization. When examined by sexual orientation, this indirect relationship remained significant only among bisexual women in the sample.

Conclusions

Study findings make a valuable contribution to the literature on victimization and health risk behaviors such as smoking. Given the negative and long-term impact of victimization on women, strategies are needed that reduce the likelihood of victimization and subsequent engagement in health risk behaviors such as smoking.

Implications

The study findings make a valuable contribution to the literature on sexual minority women’s health on the influence of victimization on health risk behaviors. With the goal of reducing the likelihood of adult victimization and subsequent engagement in health risk behaviors, programs and policies aimed at preventing victimization of women are warranted. Providers and community health agencies should assess and target physically and sexually abused sexual minority youth for mental health intervention with the goal of interrupting the progression from childhood victimization to adult victimization and subsequent engagement in health risk behaviors.

Introduction

The prevalence of cigarette smoking among women in the United States has decreased substantially in recent decades.1 However, smoking rates among sexual-minority women (SMW; lesbian, bisexual) remain elevated compared to those of heterosexual women.2–4 Population-based studies suggest that SMW smoke at rates 1.5–2 times the rate of heterosexual women and that these disparities are observed across the lifespan.5 To date, few studies have focused on the etiology of the elevated rates of smoking among SMW.6 Given the known negative health consequences associated with smoking, further research is needed to identify the mechanisms that influence smoking behaviors among this population of women.

Psychosocial factors such as stress associated with traumatic life events play a role in the risk behaviors of women, with smoking as a response to stressful life events being well established.7 An important yet under-researched source of traumatic stress among SMW is the experience of victimization. Compared to heterosexual women, SMW report elevated rates of trauma, including stressful childhood experiences such as physical, sexual, and emotional abuse and neglect.8–12 Comparisons of adult victimization experiences among heterosexual women and SMW are less consistent. For example, two studies comparing sexual minorities with heterosexual siblings found greater risk of adult sexual assault among lesbian and bisexual women than among their female siblings.11,13 Moracco et al.14 found that lesbian or bisexual women were more likely than heterosexual women to report both sexual assault by a stranger and sexual assault by a known person. No differences were found, however, in a study using a national population-based sample15 or in a study using a community-based sample of demographically matched lesbian and heterosexual women.16 Study results associated with sexual orientation and physical abuse mirror those of sexual abuse, with the majority of findings suggesting an elevated risk among SMW for physical victimization in both childhood and adulthood.12,13,17

Among women in general, victimization has been shown to increase risk of tobacco initiation and dependence.18–20 Data from the Nebraska Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (Adverse Childhood Experiences module) indicate that the relative risk for smoking ranged from 1.5 to 2.7 times higher among individuals with direct (eg, physical, sexual, or verbal) and indirect (eg, witnessing abuse of other children or violence between parents or other adults) exposures to adverse childhood experiences.21 To date, little is known about the relationship between victimization and smoking among SMW. In one recent study, Lehavot and Simoni22 reported on the associations between childhood victimization and smoking using an Internet-based sample of SMW. Results of structural equation analyses demonstrated an association between childhood sexual abuse and increased risk of smoking in adulthood. This large and well-conceived study makes an important contribution to the literature; however, the sample did not include a heterosexual comparison group and was primarily limited to white SMW. Given elevated rates of victimization across the lifespan among SMW, it is important to replicate this earlier research in a large and diverse sample of women with varying sexual orientations.

Hypothesized Relationships Among Victimization, Sexual Orientation and Smoking

The extant literature consistently demonstrates that victimization experiences in childhood and adulthood are associated with an elevated risk of smoking behaviors among adults.18–21 As such, we anticipate that regardless of sexual orientation, victimization experiences will be associated with increased risk for current smoking. However, an important yet unanswered research question is whether the strength of the association between victimization experiences and smoking varies based on sexual orientation. The scientific foundation for this research question lies with known variations in rates of victimization based on sexual orientation. Specifically, compared with heterosexual women, SMW report higher rates of multiple forms of victimization at various stages of the life cycle which may compound their risk for negative health risk behaviors. Further, victimization in childhood is a known risk factor for re-victimization in both childhood and in adulthood. As such, another unanswered question is whether—in addition to the hypothesized direct effects—there are also indirect effects of childhood victimization on self-reported smoker status. That is, childhood victimization may increase the likelihood of adult victimization, which may in turn influence adult smoking status. These hypothesized relationships are consistent with extant literature linking childhood victimization to further victimization experiences in adulthood23 and victimization experiences to increased risk for smoking.20,24

Specific Aims

The purpose of this study was to examine the relationships between childhood and adulthood victimization and current smoking status among heterosexual and SMW. The main hypothesis was that victimization experiences would predict current smoking status and that the strength of this association would differ based on sexual orientation. Further, we hypothesized that the effect of childhood victimization on self-reported smoking status would be mediated by adult victimization.

Methods

Study Samples and Interviews

We used data from two studies that used similar survey methods and interview questionnaires: The Chicago Health and Life Experiences of Women (CHLEW) study and the National Study of Health and Life Experiences of Women (NSHLEW). The NSHLEW is a 20-year longitudinal study of drinking behaviors and problems among a nationally representative sample of adult women in the United States every 5 years (1981 and 2001).25–27 The CHLEW is a 17-year longitudinal study (1999–2016) that replicated and extended the NSHLEW with SMW in the greater Chicago metropolitan area. (See Hughes et al.28 and Wilsnack et al.29 for more detailed information about the studies.) The CHLEW study was advertised in local newspapers, on Internet listservs, and on flyers posted in churches and bookstores and distributed to individuals and organizations via formal and informal social events and social networks. Eligibility criteria included being age 18 or older, English-speaking, identifying as lesbian and residence in Chicago or surrounding suburbs. Candidates meeting basic eligibility requirements in a telephone interview were invited to participate in the semi-structured interview. Although women who identified as bisexual in the telephone screening were excluded, 11 women identified as bisexual in the actual interview.

Trained female interviewers conducted 90-minute face-to-face interviews in the participants’ homes or other private settings. Questions about potentially sensitive topics such as physical and sexual abuse were asked toward the end of the interview, when rapport was well established. Women in the CHLEW provided written consent to participate. The Institutional Review Boards at the NSHLEW and CHLEW principal investigators’ home institutions approved procedures for obtaining informed consent and protecting confidentiality.

Measures

Smoker Status

Current smoking status was based on responses to the following question, “Do you currently smoke cigarettes?” Responses were coded Yes = 1 and No = 0.

Childhood Victimization Experiences

We assessed three forms of childhood victimization experienced prior to age 18: childhood sexual abuse, childhood physical abuse, and parental neglect.

Childhood sexual abuse was assessed using questions about eight types of sexual activities before age 18, ranging from exposure and fondling to anal and vaginal penetration. Sexual abuse prior to 18 was defined as Childhood sexual abuse based on Gail Wyatt’s work as:30 any intra-familial sexual activity before age 18 that was unwanted by the participant or that involved a family member five or more years older than the participant; or any extra-familial sexual activity that occurred before age 18 and was unwanted, or that occurred before age 13 and involved another person five or more years older than the participant. Responses were used to create a dichotomous variable indicating whether or not the participant reported experiences that met Wyatt’s criteria.

To measure childhood physical abuse we asked participants, “When you were growing up, were you physically hurt or injured by your parents or other family members?” Response options were never, rarely, sometimes, often and very often. Participants who reported being physically hurt or injured (any response other than “never”) were asked the follow-up question, “Do you feel that you were physically abused by your parents or other family members when you were growing up?” “Yes” or “no” responses to the follow-up question were used as a dichotomous measure of whether the participant had experienced childhood physical abuse.

Parental neglect was assessed using the question, “Thinking back to when you were about 10 years old, what were your parents’ usual methods of disciplining you?” Response options were (1) explained to me why something was wrong; (2) put me in time-out or sent me to my room; (3) took away privileges or grounded me; (4) neglected my basic needs (food, clothing, shelter, love); (5) shouted, yelled, or screamed; (6) spanked me with bare hand; (7) spanked or hit with belt, switch, or other object; and (8) beat up, punched, choked, or threw me down. Participants who indicated that their parents’ usual method of discipline was neglect of their basic needs were categorized as experiencing parental neglect. Responses were dichotomized to differentiate experiences of parental neglect: none versus any.

Adult Victimization Experiences

We assessed three forms of adult victimization (ie, experienced when the participant was age 18 or older): adult sexual assault, adult physical assault, and intimate partner violence.

Adult sexual assault was measured with the question “Since you were 18 years old, was there a time when someone forced you to have sexual activity that you really did not want? This might have been intercourse or other forms of sexual activity, and might have happened with husbands, partners, lovers, or friends, as well as with more distant persons and strangers.” Responses were dichotomized to reflect any versus no adult sexual assault.

Adult physical assault was assessed by the questions, “Not counting experiences involving conflicts with your partner or unwanted sexual experiences, has anyone other than your partner attacked you with a gun, knife, or some other weapon, whether you reported it or not?” and “Has anyone, excluding your partner, ever attacked you without a weapon but with the intent to kill or seriously injure you?” Affirmative responses to one or both of these questions were used to indicate any (vs. no) adult physical assault.

Questions used to assess intimate partner violence (IPV) in the CHLEW asked participants whether their most recent partner ever “threw something at you, pushed you, or hit you” or “threatened to kill you, with a weapon or in some other way?” Follow-up questions asked whether these experiences had happened in the previous 12 months. In the 2001 NSHLEW, IPV was assessed using open-ended responses to a question that asked participants to describe the “most physically aggressive thing done to you during the last 2 years by someone who was or had been in a close romantic relationship with you.” Each response was reviewed and coded into one of several categories. Responses most closely matching the two CHLEW questions described above were included in the current analyses. For example, NSHLEW participants who used descriptors such as “pushed me,” “grabbed me,” “hit me,” “beat me,” “choked me,” and “kicked me” were coded as having experienced IPV. Although wording of the questions and the timeframes differed in the CHLEW and NSHLEW studies, the responses in each study provide an overall indicator of any versus no recent IPV experienced by participants.

The dichotomous variables for each of the three indicators of adult and child victimization were summed separately creating two scores which ranged from 0 (no victimization) to 3 (all three types of victimization experienced).

Control Variables

Control variables included participant’s age in years, race/ethnicity (African American, Hispanic, and white), education (high school or less, some college, college degree, graduate or professional degree), income (5 ordinal levels: <$10 000, $10 000–$29 999, $30 000–$39 999, $40 000–$59 999, or ≥$60 000 annually), sexual identity (heterosexual, lesbian, or non-heterosexual, non-lesbian), parental drinking problems, and study (CHLEW vs. NSHLEW).

Self-reported sexual identity of participants was classified into one of three categories: heterosexual, lesbian, and non-heterosexual, non-lesbian (NHNL), women. Because of the small number of bisexual women in the CHLEW and NSHLEW we included women who identified as “mostly heterosexual” or “mostly lesbian” with those who identified as NHNL. This classification was based on the distribution and preliminary analyses that showed no significant differences on outcome measures between women who identify as “mostly heterosexual” or “mostly lesbian” or “bisexual.”

Our measure of parental drinking problems was based on the question, “Did your [father/mother] ever have any problems due to [his/her] drinking, such as marriage or family problems, problems with the law, problems with work or health—any kind of problems related to [his/her] drinking?” Responses to separate questions about father and mother were combined into a dichotomous indicator of any versus no parental drinking problems. Because the CHLEW study recruited participants from the Chicago metropolitan area, it included only urban/suburban participants. The NSHLEW used a national probability sampling design, resulting in both urban/suburban and rural participants. We restricted the NSHLEW sample to exclude participants who lived in a rural area so that both the NSHLEW and the CHLEW study samples represent women who lived in an urban/suburban area. Also because the age inclusion criteria for NSHLEW was age 21 and older (compared to 18 and older for CHLEW), we restricted the sample to include only participants aged 21 and older.

Analysis

Using Mplus statistical software, we conducted path analyses with observed variables to examine the effects of childhood and adulthood victimization on current smoker status in each of three sexual orientation groups. We first fitted the model with all participants to examine group differences (ie, lesbian, NHNL vs. heterosexual women) in the likelihood of reporting childhood and adulthood victimization, in their current smoker status, and in the effect of childhood victimization on smoker status mediated by adult victimization. Then, we conducted multi-group analyses to evaluate these relationships within each sexual orientation group. We assessed overall model fit using the model fit chi-square test, root mean squared error of approximation (RMSEA), and comparative fit index (CFI).31,32

We used the mean and variance adjusted weighted least-squares method (WLSMV estimator) suitable for models that include categorical endogenous variables33 to estimate the model fit. The regression coefficients obtained by the WLSMV estimator, however, were not directly interpretable. Hence, we used the STATA GSEM module to estimate logit/ordered logit regression coefficients with odds ratios (OR) and effect size (d).34 All analyses (except indirect effect analysis with the STATA binary mediation module that uses a bootstrapping method to calculate standard errors) were based on weighted data to reflect selection probabilities and oversampling of heavier drinkers in the NSHLEW sample. Data from Wave 1 (2000–2001) of the CHLEW study and data from Wave 5 (2001) of the NSHLEW study were used in these analyses.

Results

Model Fit

All three fit statistics indicated an excellent overall model fit for both the total sample model and the multigroup model. For the total sample model, the p-value for the model fit chi-square (X2 = 0.10, df = 1) was .75, and CFI and RMSEA were 1.0 and 0.0, respectively. The p-value for the model fit chi-square (X2 = 0.17, df = 3) for the multigroup model was .98, and CFI and RMSEA for this model were 1.0 and 0.0, respectively.

Sample Characteristics

Descriptive statistics for variables included in the model are presented in Table 1. The sample included 953 women. The mean age of the study sample was 40.0 (SD = 12.3). The majority of the sample was white (54.6%) with at least some college education (69.7%). More than half of the participants identified as heterosexual (52.7%); 31.8% identified as lesbian and the other 15.5% identified as bisexual, mostly lesbian or mostly heterosexual (the NHNL group). Twenty-eight percent of the sample reported being a current smoker.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Study Sample (N = 953)

| Variables | N a | % or mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|

| Smoker status | ||

| Yes | 270 | 28.4 |

| No | 682 | 71.6 |

| Childhood victimization | ||

| 0 | 330 | 36.6 |

| 1 | 329 | 36.4 |

| 2 | 209 | 23.1 |

| 3 | 35 | 3.9 |

| Adulthood victimization | ||

| 0 | 560 | 59.8 |

| 1 | 267 | 28.5 |

| 2 | 97 | 10.4 |

| 3 | 12 | 1.3 |

| Age (Mean) | 953 | 40.0 (12.3) |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| White | 521 | 54.6 |

| African American | 240 | 25.2 |

| Hispanic | 192 | 20.2 |

| Education | ||

| High school or less | 310 | 32.6 |

| Some college | 353 | 37.1 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 165 | 17.3 |

| Grad/professional degree | 124 | 13.0 |

| Annual income | ||

| <$10 000 | 110 | 11.6 |

| $10 000–$29 999 | 240 | 25.5 |

| $30 000–$39 999 | 135 | 14.3 |

| $40 000–$59 999 | 180 | 19.1 |

| ≥$60 000 | 278 | 29.2 |

| Parental drinking problem | ||

| Yes | 288 | 31.8 |

| No | 618 | 68.2 |

| Sexual Orientation | ||

| Heterosexual | 502 | 52.7 |

| Lesbian | 303 | 31.8 |

| Non-heterosexual, Non-lesbian | 148 | 15.5 |

| Study | ||

| CHLEW | 405 | 42.5 |

| NSHLEW | 548 | 57.5 |

CHLEW = Chicago Health and Life Experiences of Women; NSHLEW = National Study of Health and Life Experiences of Women.

a Ns vary due to missing data.

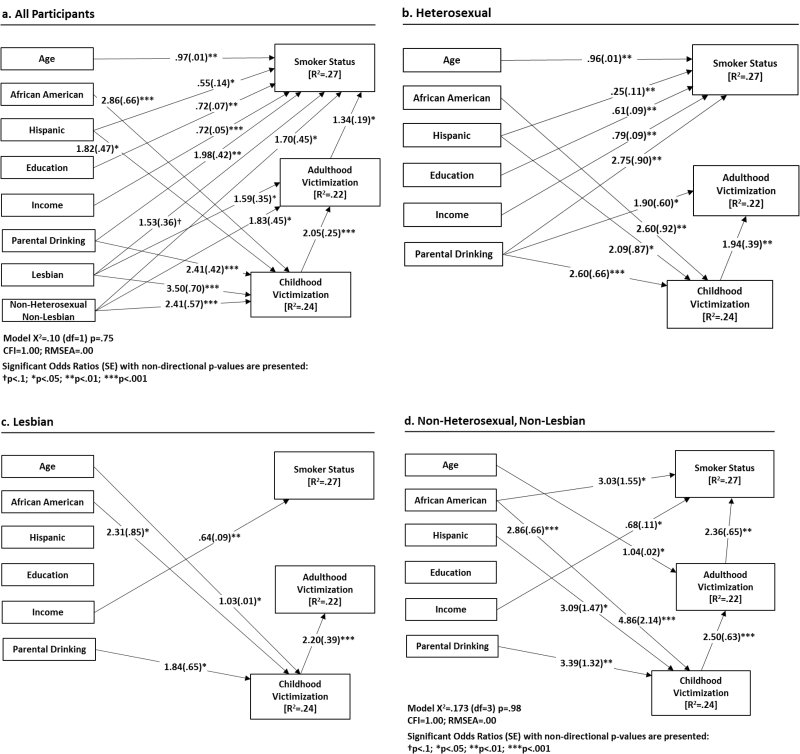

As shown in Figure 1a, all of the background characteristics were directly related to smoking status in the full sample. As age increased, the odds of being a current smoker decreased (OR = 0.97, SE = 0.01, p = .002; d = −0.01). Hispanics were less likely to smoke currently than whites (OR = 0.55, SE = 0.14, p = .022; d = −0.33), and higher education and income levels decreased the odds of being a current smoker (OR = 0.72, SE = 0.07, p = .001; d = −0.18, and OR = 0.72, SE = 0.042, p < .001; d = −0.18, respectively). Women who reported parental drinking problems were more likely to be current smokers (OR = 1.98, SE = 0.42, p = .001; d = 0.38). Compared to heterosexual women, the bisexual group had higher odds of being current smokers (OR = 1.70, SE = 0.45, p = .048; d = 0.29).

Figure 1.

A path model of victimization and smoker status (N = 898).

Based on the multi-group analysis, however, background characteristics that were directly related with smoker status were found to be different. While age, race/ethnicity, education, income and parental drinking were all significant predictors of smoker status among heterosexual women (p’s < .05), income and being African American were the only significant predictors of smoker status among women included in the NHNL group. Income was found to be the only significant predictor of smoker status among women who identified as exclusively lesbian (See Figure 1b, 1c, and 1d).

Predictors of Victimization Experiences

Victimization experiences were common, with 63.4% of participants reporting at least one form of childhood victimization and 40.2% reporting at least one form of victimization in adulthood. As shown in Figure 1a, childhood victimization was associated with race/ethnicity, parental drinking problems, and sexual identity. African American (OR = 2.86, SE = 0.66, p < .001; d = 0.58) and Hispanic women (OR = 1.82, SE = 0.47, p = .019; d = 0.33), compared to white women, were more likely to report childhood victimization. Having one or both parents who had a drinking problem was a significant predictor of childhood victimization (OR = 2.41, SE = 0.42, p < .001; d = 0.48). The bisexual and lesbian groups were more likely than the heterosexual group to report childhood victimization (OR = 2.41 (d = 0.49) for the bisexual group and OR = 3.50 (d = 0.69) for the lesbian group, p’s < .001). When estimated within each sexual orientation group, there was no difference between Hispanics and whites in childhood victimization among lesbians as shown in Figure 1d. In the lesbian group, age was a significant predictor of childhood victimization with older lesbians more likely to report experiences of childhood victimization compared to young lesbians (OR = 1.03, SE = 0.01, p = .013; d = 0.02).

Women in the bisexual and lesbian groups were more likely than those in the heterosexual group to report adult victimization (OR = 1.83, SE = 0.45; d = 0.33 for the bisexual group, and OR = 1.59, SE = 0.35; d = 0.26 for the lesbian group; p’s = .015 and .035, respectively). Other variables were not significantly related with adult victimization, but when relationships were assessed within each sexual orientation group, parental drinking problems were associated with adult victimization among heterosexual women (OR = 1.90, SE = 0.60, p = .042; d = 0.35) as shown in Figure 1b.

Relationship Between Victimization Experiences and Smoking Status

As Figure 1a illustrates, women victimized in childhood were more likely to be re-victimized during adulthood (OR = 2.05, SE = 0.25, p < .001; d = 0.39), and adult victimization had a direct effect on current smoker status (OR = 1.34, SE = 0.19, p = .041; d = 0.16). Childhood victimization was not related directly to smoker status; rather, the effect of childhood victimization on self-reported smoker status was mediated by adult victimization (indirect effect, β = 0.05, SE = 0.016, p = .03). In other words, childhood victimization was indirectly related to current smoking through victimization in adulthood. In multi-group analyses, this indirect relationship remained significant only among women included in the non-hetero, non-lesbian group (indirect effect, β = 0.12, SE = 0.05, p = .02).

Discussion

Our results support previous research findings15,35 showing high rates of victimization experiences among SMW. More than 60% of the sample reported at least one form of childhood victimization and 40% reported at least one form of victimization in adulthood. Consistent with the extant literature, women in the bisexual and lesbian groups were more likely than those in the heterosexual group to report both childhood and adult victimization. Risk factors for victimization also differed based on sexual identity. Among all women, having one or both parents who had a drinking problem was a significant predictor of childhood victimization. In addition, African American and Hispanic women compared to white women, were more likely to report childhood victimization. However, among lesbians, age was a significant predictor of childhood victimization with older lesbians more likely to report experiences of childhood victimization compared to young lesbians. Although not the central focus of the current study, variations in victimization risk factors based on sexual identity suggest the need for a more comprehensive study examining this research question.

An important contribution of this study is that for the first time, we demonstrate in a sample of heterosexual and SMW women the association between victimization experiences and current smoking status. Study hypotheses regarding the relationships between victimization and smoking behaviors were only partly confirmed. Consistent with study hypotheses, among all study participants (full model), adult victimization was directly associated with an increased likelihood of current smoking. A key research question was whether there were both direct and indirect effects of childhood victimization on smoking status. Counter to hypotheses, a direct relationship between childhood victimization and smoking was not observed. However, an indirect relationship was observed. We found that the effect of childhood victimization on self-reported smoker status was mediated by adult victimization; that is, childhood victimization increased the likelihood of victimization as an adult, and adult victimization influenced smoking status. This mediation effect was especially robust among those study participants who reported higher levels of childhood victimization. These findings are consistent with the extant literature linking childhood victimization to further victimization experiences in adulthood23 and victimization experiences to an increased risk for smoking.20,24 Model testing for each sexual orientation identity separately suggests that the relationship between victimization and smoking only held for women included in the bisexual group who reported a high level of childhood victimization. These findings suggest that the impact of adverse childhood experiences on adult smoking behaviors varied based on the higher levels of victimization and sexual orientation, indicating the need for further investigation of these risk factors as drivers of known health and behavioral risk disparities among SMW.

Given the increased likelihood of victimization among SMW and the known associations between victimization and a range of health-compromising behaviors, additional research is needed to identify risk and protective factors for SMW and to develop effective violence prevention and treatment programs. Of note was the consistent and detrimental impact of parental drinking on smoking behaviors and victimization among women in our sample. Childhood exposure to parental addiction is relatively common in the United States.36 In a study of harmful childhood experiences, substance abuse by a household member was the most common type of exposure reported.24 Consistent with the negative consequences of parental drinking observed in the current sample, previous research has demonstrated that having a parent with substance abuse or addiction contributes to a range of challenges during childhood.37–39 For example, children of parents who abuse alcohol are more likely to be victims of violence and to experience parental violence, family break-up, and drug addiction themselves.40 Hussong and colleagues41 found that compared with control subjects, children of alcoholics were at greater risk for negative stressors, more likely to report experiencing these stressors repeatedly, and more likely to show higher rates of distress and poor coping. In this study, participants who reported parental drinking problems were more likely to be current smokers and to have experienced victimization in both childhood and adulthood, with the effect being most consistent among heterosexual women. At least one study has shown higher rates of substance use among the parents of lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults.42 Additional research is needed to determine base-rates of exposure to parental alcohol abuse among SMW and to further explore the impact of parental drinking on the elevated rates of childhood victimization experiences in this population.

Compared to the general population, rates of smoking in this sample were elevated, with twenty-eight percent of the sample meeting criteria for current smoker. Consistent with prior studies, compared to heterosexual women, the bisexual and lesbian groups had slightly higher odds of being current smokers.43 Data for Wave 1 of the CHLEW sample were collected in 2000–2001 and Wave 5 from the NSHLEW sample were collected in 2001. Rates of smoking among women have decreased substantially since the 1990s, when the number of smoking among adults was over 25%.44 Although analyses from these combined samples provide a rich and unique opportunity to compare SMW to a probability sample of heterosexual women using similar measures, questions exist as to why the often-reported large disparities in smoking rates by sexual orientation was not observed in the current study. As the goal of the present study was to identify predictors of smoking behaviors and not to establish smoking prevalence rates, so our results still have important implications for understanding smoking behaviors among women with differing sexual orientations.

Beyond victimization experiences, basic demographic factors associated with smoking also predicted smoking in this sample.45 However, these relationships were primarily observed among heterosexual women. Specifically, older age, non-Hispanic white ethnicity, and higher education and income decreased the odds of being a current smoker. Only income level was associated with smoking status across all three samples. Recent studies have suggested the continued high risk for smoking among individuals from lower socioeconomic backgrounds.46 Risk factors influencing this relationship appear to be the reduced likelihood of successful attempts at quitting combined with reduced social support for quitting, low motivation and self-efficacy for quitting, higher levels of nicotine dependency, and less access and adherence to smoking cessation treatments.46 As for women in general, larger-scale tobacco prevention and control efforts in the SMW community will need to include specific outreach to individuals of lower socioeconomic status.

Limitations

The CHLEW sample was selected using non-probability methods. Although probability samples are preferable, probability surveys of SMW typically over-represent white, middle-class SMW who are comfortable disclosing their sexual orientation.47 An important limitation of the study is the fact that it included a very small number of women who identified as bisexual. Because of this, we combined bisexually identified women with those who identified as mostly lesbian and mostly heterosexual. Although research has shown that each of these intermediate groups is at heightened risk for a variety of health-threatening behaviors and negative health outcomes, relative to heterosexual women48 too little is known about them to determine whether they are more similar to bisexual women than to exclusively lesbian or exclusively heterosexual women, respectively. Additional research is needed that includes large groups of self-identified bisexual women. Further, men were excluded from the study. Research on mixed or male samples would be needed to examine whether these relationships generalize to men.

Another limitation was our reliance on self-reports for smoking status; however, self-report has been established as a reliable indicator of smoking status.49 The data analyzed here were collected as part of a larger study of SMW’s health. Although tobacco use behaviors were assessed, these measures did not include standardized measures of nicotine dependency, interest and self-efficacy for quitting, parental smoking behavior or factors associated with maintaining smoking behaviors. To enhance the methodological rigor, future studies should include standardized measures of smoking behaviors. Our data are from two important longitudinal studies of women’s life experiences. However, these data were collected more than a decade ago and should be replicated with data that are more recent. The focus of the present study was not on determining smoking prevalence or overall rates of victimization, factors that may change over time. As such, we anticipate that the observed patterns of relationships would be replicated with a more current data set. Finally, the cross-sectional design limits evaluation of causality, so it is not possible to determine whether smoking began before or after victimization (especially in the case of adult victimization).

Conclusions

This study is among the first to examine the influence of childhood and adult victimization experiences on smoking status in a sample of heterosexual and SMW. Study findings make a valuable contribution to the literature on the influence of adverse experiences on health risk behaviors. Given the negative and long-term impact of experiences of victimization on women’s health and well-being, programs and policies aimed at preventing victimization of women are warranted. Providers and community health agencies should assess and target physically and sexually abused sexual minority youth for mental health intervention with the goal of interrupting the progression from childhood victimization to adult victimization and subsequent engagement in health risk behaviors.

Funding

This research was supported by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism grants K01 AA00266 and R01 AA13328 (to TLH), and R01 AA004610 (to SCW) and National Institute on Drug Abuse, R01 DA023935-01A2 to Dr. AKM. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism or the National Institutes of Health.

Declaration of Interests

None declared.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the women who participated in the CHLEW and NSHLEW studies.

References

- 1. Agaku IT, King BA, Dube SR. Current cigarette smoking among adults-United States, 2005–2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63(2):29–34. www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6302a2.htm?s_cid = mm6302a2_w Accessed June 17, 2014. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lee JG, Griffin GK, Melvin CL. Tobacco use among sexual minorities in the USA, 1987 to May 2007: a systematic review. Tob Control. 2009;18(4):275–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. King BA, Dube SR, Tynan MA. Current tobacco use among adults in the United States: findings from the National Adult Tobacco Survey. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(11):e93–e100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Conron KJ, Mimiaga MJ, Landers SJ. A population-based study of sexual orientation identity and gender differences in adult health. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(10):1953–1960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fredriksen-Goldsen KI, Kim HJ, Barkan SE, Muraco A, Hoy-Ellis CP. Health disparities among lesbian, gay, and bisexual older adults: results from a population-based study. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(10):1802–1809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Blosnich J, Lee JG, Horn K. A systematic review of the aetiology of tobacco disparities for sexual minorities. Tob Control. 2013;22(2):66–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983;24(4):385–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Schneeberger AR, Dietl MF, Muenzenmaier KH, Huber CG, Lang UE. Stressful childhood experiences and health outcomes in sexual minority populations: a systematic review. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2014;49(9):1427–1445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Austin SB, Roberts AL, Corliss HL, Molnar BE. Sexual violence victimization history and sexual risk indicators in a community-based urban cohort of “mostly heterosexual” and heterosexual young women. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(6):1015–1020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lehavot K, Molina Y, Simoni JM. Childhood trauma, adult sexual assault, and adult gender expression among lesbian and bisexual women. Sex Roles. 2012;67(5−6):272–284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Balsam KF, Rothblum ED, Beauchaine TP. Victimization over the life span: A comparison of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and heterosexual siblings. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2005;73(3):477–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Friedman MS, Marshal MP, Guadamuz TE, et al. A meta-analysis of disparities in childhood sexual abuse, parental physical abuse, and peer victimization among sexual minority and sexual nonminority individuals. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(8):1481–1494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Stoddard JP, Dibble SL, Fineman N. Sexual and physical abuse: a comparison between lesbians and their heterosexual sisters. J Homosex. 2009;56(4):407–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Moracco KE, Runyan CW, Bowling JM, Earp JA. Women’s experiences with violence: a national study. Womens Health Issues. 2007;17(1):3–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hughes T, McCabe SE, Wilsnack SC, West BT, Boyd CJ. Victimization and substance use disorders in a national sample of heterosexual and sexual minority women and men. Addiction. 2010;105(12):2130–2140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hughes TL, Johnson T, Wilsnack SC. Sexual assault and alcohol abuse: a comparison of lesbians and heterosexual women. J Subst Abuse. 2001;13(4):515–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Pettingell EAR, Bearinger L, Resnick M, Murphy A, Combs L. Hazards of stigma: The sexual and physical abuse of gay, lesbian, and bisexual adolescents in the United States and Canada. Child Welfare. 2006;85(2)195–213. http://web.b.ebscohost.com/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfvie wer?vid = 1&sid = 1f9b7e41-eae0-4ece-999c-771f3134392d%40sessio nmgr111&hid = 106 Accessed October 6, 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Anda RF, Croft JB, Felitti VJ, et al. Adverse childhood experiences and smoking during adolescence and adulthood. JAMA. 1999;282(17):1652–1658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Topitzes J, Mersky JP, Reynolds AJ. Child maltreatment and adult cigarette smoking: a long-term developmental model. J Pediatr Psychol. 2010;35(5):484–498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ford ES, Anda RF, Edwards VJ, et al. Adverse childhood experiences and smoking status in five states. Prev Med. 2011;53(3):188–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Yeoman K, Safranek T, Buss B, Cadwell BL, Mannino D. Adverse childhood experiences and adult smoking, Nebraska, 2011. Prev Chronic Dis. 2013;10:E159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lehavot K, Simoni JM. The impact of minority stress on mental health and substance use among sexual minority women. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2011;79(2):159–170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Widom CS, Czaja SJ, Dutton MA. Childhood victimization and lifetime revictimization. Child Abuse Negl. 2008;32(8):785–796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, et al. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. Am J Prev Med. 1998;14(4):245–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wilsnack RW, Wilsnack SC, Klassen AD. Women’s drinking and drinking problems: patterns from a 1981 national survey. Am J Public Health. 1984;74(11):1231–1238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wilsnack RW, Kristjanson AF, Wilsnack SC, Crosby RD. Are U.S. women drinking less (or more)? Historical and aging trends, 1981-2001. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2006;67(3):341–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wilsnack SC, Klassen AD, Schur BE, Wilsnack RW. Predicting onset and chronicity of women’s problem drinking: a five-year longitudinal analysis. Am J Public Health. 1991;81(3):305–318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hughes TL, Wilsnack SC, Szalacha LA, et al. Age and racial/ethnic differences in drinking and drinking-related problems in a community sample of lesbians. J Stud Alcohol. 2006;67(4):579–590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wilsnack SC, Hughes TL, Johnson TP, et al. Drinking and drinking-related problems among heterosexual and sexual minority women. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2008;69(1):129–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wyatt GE. The sexual abuse of Afro-American and white-American women in childhood. Child Abuse Negl. 1985;9(4):507–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Jöreskog KG, Sörbom D. Lisrel V: Estimation of Linear Structural Equation Systems by Maximum Likelihood Methods. Chicago, IL: International Education Services; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Fan X, Thompson B, Wang L. Effects of sample size, estimation methods, and model specification on structural equation modeling fit indexes. Struct Equ Modeling. 1999;6(1):56–83. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Muthén B, Du Toit SH, Spisic D. Robust inference using weighted least squares and quadratic estimating equations in latent variable modeling with categorical and continuous outcomes. Psychometrika. 1997;75(1):1–45. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JPT, Rothstein HR. Introduction to Meta-Analysis. West Sussex, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Drabble L, Trocki KF, Hughes TL, Korcha RA, Lown AE. Sexual orientation differences in the relationship between victimization and hazardous drinking among women in the National Alcohol Survey. Psychol Addict Behav. 2013;27(3):639–648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Dube SR, Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Croft JB, Edwards VJ, Giles WH. Growing up with parental alcohol abuse: exposure to childhood abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction. Child Abuse Negl. 2001;25(12):1627–1640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Springer KW, Sheridan J, Kuo D, Carnes M. Long-term physical and mental health consequences of childhood physical abuse: results from a large population-based sample of men and women. Child Abuse Negl. 2007;31(5):517–530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Batten SV, Aslan M, Maciejewski PK, Mazure CM. Childhood maltreatment as a risk factor for adult cardiovascular disease and depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(2):249–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Draper B, Pfaff JJ, Pirkis J, et al. ; Depression and Early Prevention of Suicide in General Practice Study Group. Long-term effects of childhood abuse on the quality of life and health of older people: results from the Depression and Early Prevention of Suicide in General Practice Project. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(2):262–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Christoffersen MN, Soothill K. The long-term consequences of parental alcohol abuse: a cohort study of children in Denmark. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2003;25(2):107–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Hussong AM, Bauer DJ, Huang W, Chassin L, Sher KJ, Zucker RA. Characterizing the life stressors of children of alcoholic parents. J Fam Psychol. 2008;22(6):819–832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. McCabe SE, West BT, Hughes TL, Boyd CJ. Sexual orientation and substance abuse treatment utilization in the United States: results from a national survey. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2013;44(1):4–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Balsam KF, Beadnell B, Riggs KR. Understanding sexual orientation health disparities in smoking: a population-based analysis. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2012;82(4):482–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Centers for Disease Control (CDC). Cigarette smoking among adults--United States, 1990. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1992;41(20):354–355, 361–362. www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/00016738.htm Accessed November 5, 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Garrett BE, Dube SR, Winder C, Caraballo RS. Cigarette smoking—United States, 2006–2008 and 2009–2010. CDC Health Disparities and Inequalities Report—United States, 2013. 2013;62(3):81 www.cdc.gov/MMWr/pdf/other/su6203.pdf#page = 83 Accessed December 6, 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Hiscock R, Bauld L, Amos A, Fidler JA, Munafò M. Socioeconomic status and smoking: a review. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2012;1248:107–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Bowen DJ, Bradford JB, Powers D, et al. Comparing women of differing sexual orientations using population-based sampling. Women Health. 2005;40(3):19–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Hughes TL, Wilsnack SC, Kristjanson AF. Substance use and related problems among U.S. women who identify as mostly heterosexual. BMC Public Health. 2015;15(1):803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Vartiainen E, Seppälä T, Lillsunde P, Puska P. Validation of self reported smoking by serum cotinine measurement in a community-based study. J Epidemiol Commun Health. 2002;56(3):167–170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]