Abstract

Introduction:

Warning labels for cigarettes proposed by Food and Drug Administration (FDA) were rejected by the courts partly because they were thought to be emotionally evocative but have no educational value. To address this issue, we compared three types of smoking warnings: (1) FDA-proposed warnings with pictures illustrating the smoking hazards; (2) warnings with the same text information paired with equally aversive but smoking-irrelevant images; and (3) text-only warnings.

Methods:

Smokers recruited through Amazon’s Mechanical Turk were randomly assigned to one of the three conditions. They reported how many cigarettes they smoked per day (CPD) during the past week and then viewed eight different warnings. After viewing each warning, they rated its believability and perceived ability to motivate quitting. One week later, 62.3% of participants again reported CPD during the past week, rated how the warnings they viewed the week before changed their feeling about smoking, rated their intention to quit in the next 30 days, and recalled as much as they could about each of the warnings they viewed.

Results:

Compared to the irrelevant image and text-only warnings, FDA warnings were seen as more believable and able to motivate quitting and at the follow-up, produced lower CPD, worse feeling about smoking, and more memory for warning information, controlling for age and baseline CPD.

Conclusions:

Emotionally evocative warning images are not effective in communicating the risks of smoking, unless they pertain to smoking-related hazards. In future versions of warning labels, pictorial contents should be pretested for the ability to enhance the health-hazard message.

Implications:

Our study shows that contrary to court opinions, FDA-proposed pictorial warnings for cigarettes are more effective in communicating smoking-related hazards than warnings that merely contain emotionally aversive but smoking-irrelevant images. The suggestion that FDA’s proposed warnings employed emotionally arousing pictures with no information value was not supported. Pictures that illustrate the risk carry information that enhances the persuasiveness of the warning. The congruence between pictures and text should be a criterion for selecting warning images in the future.

Introduction

In 2011, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) proposed a set of nine warning labels for cigarette packs sold in the United States, each containing a text message paired with a picture depicting the specific health hazard of smoking (eg, diseased lungs, a cancerous mouth). This action was taken under the authority of the Family Smoking Prevention Act of 2009, which mandated the use of nine health-warning statements to be placed on the front and back of cigarette packs. The Act’s authority to impose pictorial warnings was upheld in a ruling by the US Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit.1,2 However, separate court rulings by the US Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia found that the specific images proposed by FDA were likely a violation of free speech rights because they required the industry to place what the court considered to be emotionally evocative images without any educational value. In their opinion, the court claimed that “the images do not convey any warning information at all…[and] are unabashed attempts to evoke emotion (and perhaps embarrassment) and browbeat consumers into quitting.”3

Since the release of those court opinions, research has confirmed that the images proposed by FDA are not only more emotionally evocative but that they also serve the important function of making the warnings more memorable and likely to communicate the risks of smoking.4–7 Emotional information more readily grabs attention and is better remembered than neutral information.8–10 Nevertheless, the argument that such images are merely attempts to make the product appear aversive suggests that any unpleasant image placed on a cigarette pack will have this function. We challenge this interpretation by testing the alternative hypothesis that the images used as warnings must reinforce and truly illustrate the risks of the product. We predict that merely placing an unpleasant image on the product will not serve the purpose of the warning as the courts suggested.

We based this hypothesis on research showing that exposure to task-relevant emotions improves performance on many tasks,11,12 whereas task-irrelevant emotions are potent distracters that easily interfere with goal-relevant activities.13 A classic example is the emotional Stroop task, in which naming the color of emotion-laden words and pictures is significantly slower than naming the color of neutral stimuli.14,15 Such interference is thought to be partly mediated by the irrelevant thoughts elicited by emotional stimuli.16 In addition, regulating interfering emotions is effortful and consumes cognitive resources.17,18 Thus, one would expect that the emotions elicited by irrelevant images will interfere with the processing of the text and make it less memorable

Taken together, previous findings highlight the potentially detrimental effects of emotional but irrelevant pictures in warnings for cigarettes. Specifically, we predicted that emotionally arousing images will decrease the effectiveness of smoking-cessation warnings if the images themselves are not relevant to the text in the warning. Furthermore, when emotionally evocative images are illustrative of the text, we expected that they will reinforce the warning messages and make them more memorable than text alone.

In order to test these hypotheses, we compared the effectiveness of three types of smoking warnings that contained identical text information about smoking-related hazards. The first was the warnings proposed by FDA that paired text information with emotionally evocative images that pertained to smoking-related hazards (FDA). The second paired text information with images that were equally emotionally upsetting as those in the FDA warnings, but were irrelevant to smoking (Irrelevant). The third type of warnings contained only text information with no image (Text-only). We predicted that the FDA warnings, in which the content of the emotionally arousing images was congruent with the text, would be the most effective in communicating the risks of smoking, including both the immediate response to the warnings as well as the memorability of the warning information, measured approximately 7 days after exposure to the warnings. We also explored whether the FDA warnings would increase the intention to quit smoking and reduce smoking during the intervening week, potentially mediated by differences in warning impact as assessed by message persuasiveness and negative feelings about smoking. In contrast, we predicted that the irrelevant warnings would be the least effective due to the interference caused by the arousing but smoking-irrelevant images.

Methods

Participants

Five hundred twenty-four smokers aged 18 and older who reported smoking at least 100 cigarettes in their lifetimes and had smoked a cigarette in the last 30 days participated in an online survey at Time 1 recruited via Amazon Mechanical Turk (MTurk). This recruitment vehicle has been found to yield survey responses that are comparable to other online survey methods19 and enabled tests of our hypothesis given random assignment to conditions. We excluded 10 participants who had incomplete responses, resulting in a total of 514 participants (214 female, mean age = 33.61 years). We randomly assigned smokers to one of three conditions: FDA, Irrelevant, and Text-only (N = 176, 172, and 176, respectively). All three conditions used the eight text warnings that presented negatively-valenced risks of smoking. The Irrelevant warnings consisted of warnings with the same text information as contained in the FDA warnings, but paired with pictures selected to match the FDA images in valence and arousal as described below. The Text-only warnings only contained text information about smoking-related hazards.

We invited all participants to complete a second survey 1 week later. We retained those who responded within 4 days (N = 320, or 62.3%) in the follow-up analysis (see Table 1). All participants consented to participate when enrolling in the study, which was approved by the University of Pennsylvania Institutional Review Board.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics

| FDA | Irrelevant | Text-only | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time 1 | |||

| N | 168 | 173 | 173 |

| Male gender | 92 | 106 | 100 (2 other) |

| Years of age (M ± SD) | 33.38 ± 10.77 | 35.07 ± 11.72 | 32.36 ± 9.77 |

| Race | |||

| White | 145 | 147 | 146 |

| African American | 8 | 10 | 14 |

| Asian | 13 | 11 | 6 |

| Native American | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| Two or more races | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Other | 2 | 2 | 5 |

| Hispanic ethnicity | 11 | 12 | 17 |

| Baseline CPD (M ± SD) | 1.79 ± 0.87 | 1.83 ± 0.92 | 1.60 ± 0.80 |

| Time 2 | |||

| Days from Time 1 (M ± SD) | 7.37 ± 0.82 | 7.47 ± 0.89 | 7.34 ± 0.77 |

| N | 102 | 117 | 101 |

| Male gender | 49 | 66 | 60 (2 other) |

| Years of age (M ± SD) | 33.86 ± 10.69 | 35.21 ± 11.91 | 33.24 ± 10.21 |

| Race | |||

| White | 88 | 103 | 89 |

| African American | 6 | 6 | 5 |

| Asian | 8 | 6 | 3 |

| Native American | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Two or more races | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Other | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| Hispanic ethnicity | 6 | 9 | 9 |

| Baseline CPD (M ± SD) | 1.79 ± 0.90 | 1.81 ± 0.89 | 1.53 ± 0.74 |

CPD = cigarettes per day; FDA = Food and Drug Administration; SD = standard deviation.

Stimuli

The warnings proposed by FDA consisted of nine warnings that contained both text and pictorial information about smoking-related hazards. The positively-valenced warning advising users that “Quitting smoking now greatly reduces serious risks to your health” was not included in the test. An independent sample of 302 adult smokers recruited through MTurk rated the emotional valence and arousal of the FDA images with text removed as well as a battery of 61 images taken from the International Affective Picture System (IAPS) collection20 (http://csea.phhp.ufl.edu/Media.html). The IAPS images spanned the range of positive and negative images. We excluded the images that pertained to smoking-related hazards, contained sexually explicit content, or had poor quality. Ratings were collected using the Self-Assessment Manikin (SAM) system.20 For the rating of valence, SAM includes five cartoon images of a person that ranges from a smiling and happy figure to a frowning and unhappy figure. For the rating of arousal, SAM includes five images ranging from an excited and wide-eyed figure to a relaxed and sleepy figure. Participants could select any of the five figures on each scale that best described their own emotion, or they could select a point between any two adjacent figures if their emotion fell between the depictions of the two figures, resulting in a nine-point scale for both valence and arousal.20 To create the Irrelevant condition, we selected pictures from the 61 pretested IAPS images (eg, depictions of a car accident, a decapitated animal, and snakes, etc.) that matched as closely as possible the arousal and valence ratings of the FDA images. The two sets of pictures did not differ in valence (Mean ± SD = 3.15 ± 0.50 vs. 3.57 ± 0.57), t(14) = −1.58, p = 0.14, or arousal (4.99 ± 0.61 vs. 5.06 ± 0.41), t(14) = −0.26, p = 0.80 for FDA versus Irrelevant conditions respectively. All three conditions contained identical text information.

Procedure

At Time 1, participants first provided demographic information (age, gender, race, and Hispanic ethnicity) and reported how many cigarettes they smoked on average per day during the past week (baseline CPD) by choosing from “≤10,” “11–20,” “21–30,” or “≥31,” which corresponded to a score from 1 to 4. We then showed them eight different warnings presented in a random order. After viewing each warning, they rated how much the warning made them want to quit smoking (“ability to motivate quitting”),21 and how much they believed that the information in the warning was true (“believability”),5,6 both on a 7-point scale (1 = Not at all, 7 = Completely). We created indices for each rating by averaging the ratings across the eight warnings (Cronbach αs > 0.88). At Time 2 (ie, 1 week after Time 1), participants again reported CPD for the past week, rated how the warnings they viewed during Time 1 changed their feelings about smoking on a 7-point scale (“feeling about smoking”; 1 = feel much worse, 7 = feel much better),6,22 and rated how likely it is that they would try to stop smoking in the next 30 days on a 4-point scale (“quit intention”; 1 = very unlikely, 4 = very likely).6,23 In addition, participants recalled as much as they could about each of the warnings they viewed the week before (“memorability”).6,24,25 Following the procedure in Evans et al.,6 they typed their recollection of message content in nine boxes labeled with the word “Warning.”

Data Analysis

We used SPSS 22 (IBM Corp. 2013) for data analysis. Believability scores were heavily skewed (skewness = −1.57) and were thus dichotomized with a cutoff of 6.70 on the 7-point scale. Memorability was determined by a coder trained to identify correct message recall, that is, those that matched the text or image information in the warnings, while blinded to message condition.6 The inter-coder reliability on a random subset of 30 cases with a second coder was high (Krippendorf α = 0.89). We examined the differences between the three conditions using two orthogonal planned contrasts: (1, −0.5, −0.5) that tested the effect of the FDA versus two other types of warnings, and (0, −1, 1) that tested the effect of Text-only versus Irrelevant warnings. The two regressors were entered in the linear regression model to examine effects on continuous dependent variables (ie, ability to motivate quitting, subsequent CPD, feeling about smoking, quit intention, and memorability), and in the logistic regression model to examine the effect on the dichotomous measure of warning believability. We conducted mediation analyses to determine potential mediators of effects on changes in CPD following exposure to the warnings using a bias-corrected bootstrap approximation with 50 000 iterations implemented in the PROCESS macro for SPSS 22. 26,27

Results

The three conditions did not differ in sample size, number of female participants, race, Hispanic ethnicity, or interval between Time 1 and Time 2 (ps > .09). There was a trend for significant difference in age (F(2,511) = 2.79, p = .06), and a significant difference in baseline CPD (F(2,511) = 3.64, p = .03), both of which were controlled as covariates in subsequent analyses. Participants that completed the Time 1 survey did not differ from those that completed the Time 2 survey in gender, race, Hispanic ethnicity, age, or baseline CPD (ps > .4). (See Table 1.)

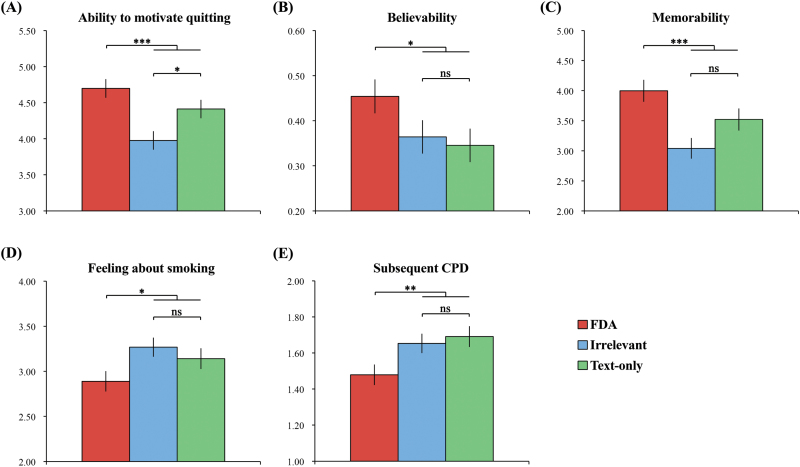

We found that compared to the other two conditions, the FDA warnings were rated as higher in ability to motivate quitting (β = 0.14, t(509) = 3.18, p = .002) and more believable (eB = 1.32, Wald χ2(1) = 4.68, p = .03). In addition, they were more memorable at follow-up (β = .18, t(315) = 3.23, p = .001), created more negative feelings about smoking (β = −0.13, t(315) = −2.29, p = .02), and lower subsequent CPD (β = −0.11, t(315) = −2.77, p = .006) (see Figure 1). Participants also saw the Irrelevant warnings as less able to motivate quitting than the Text-only warnings (β = 0.10, t(509) = −2.39, p = .02), but the two conditions did not differ on other measures (ps > .06). Quit intentions did not differ across conditions (ps > .3).

Figure 1.

Differences between the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), Irrelevant, and Text-only conditions on (A) ability to motivate quitting, (B) believability, (C) memorability, (D) feeling about smoking, and (E) subsequent cigarettes per day (CPD), adjusted for age and baseline CPD. Error bar: standard error of mean. */**/***: p < .05/.01/.005; ns: non-significant.

Mediation analysis showed that feelings about smoking mediated the impact of FDA versus other conditions on subsequent CPD (indirect effect = −0.014, bootstrap SE = 0.010, bootstrap p = .04, 95% bootstrap confidence interval (CI) = [−0.042, −0.001]). The direct effect remained significant (direct effect = −0.11, SE = 0.05, t(315) = −2.45, p = .01), suggesting partial mediation. Similar analysis showed marginally significant partial mediation by ability to motivate quitting (indirect effect = −0.010, bootstrap SE = 0.009, bootstrap p = .08, 95% bootstrap CI = [−0.036, 0.001]; direct effect = −0.12, SE = 0.05, t(315) = −2.53, p = .01). Mediation by memorability was not significant (indirect effect = 0.000, bootstrap SE = 0.008, bootstrap p > .5, 95% bootstrap CI = [−0.013, −0.018]; direct effect = −0.13, SE = 0.05, t(315) = −2.71, p = .007).

Discussion

This study supported the hypothesis that the images included in the FDA-proposed warnings did not merely serve to evoke unpleasant emotion. Indeed, when eight text messages that highlighted the risks of smoking were paired with images of comparable emotional valence and arousal to the FDA images but with no relevance to the messages, smokers found the warnings less able to motivate quitting than either text alone or the FDA warnings. In addition, smokers found the warnings less believable than the FDA warnings and less likely to remember the information in the warnings 7 days later. Furthermore, the FDA warnings produced more negative feelings about smoking, an effect that partially mediated reports of less smoking during the week following their presentation than the irrelevant and text-only warnings.

These findings suggest that images that illustrate the textual warning carry information that enhances the persuasiveness of the warning, giving smokers a stronger sense of the risks of smoking that remain at least 7 days after initial exposure. Our data did not support the court’s concern that irrelevant but emotionally arousing images might deter smokers from their habit without communicating risks of the product, in that there was no observable decline in smoking following exposure to those warnings. Indeed, they were just about as effective as text alone in influencing actual reports of smoking during the 7-day follow-up period. However, they were less effective than text alone in communicating motivation to quit smoking, a finding that was consistent with the emotional interference mechanism that was postulated to reduce the impact of emotionally irrelevant images.

The results also suggest that in the future design of warning labels, the pictures used to illustrate the risks of smoking should be pretested for ability to enhance the message. Although the FDA images were clearly more congruent with the text than in the irrelevant condition, we did not directly assess this characteristic. However, we anticipate that the effectiveness of warning messages could be enhanced by more carefully selecting images that cogently illustrate the risk of smoking in a way that is congruent with accompanying text messages. Instead, merely increasing the fear arousal (or other forms of emotional evocativeness) of pictorial warnings without considering their congruence is unlikely to improve their effectiveness.

We tested the ability of the warnings to reduce smoking during the 7-day follow-up because one might expect a stronger message to produce this effect. Nevertheless, this effect has seldom been observed, partially because follow-up studies are rare and field studies are not sensitive enough to detect such short-term effects. Indeed, we did not observe an effect on intention to quit smoking in the next 30 days at the follow-up, a finding that has been seen in prior studies that included emotional reactions as mediators and had smokers of different demographic characteristics from the present study (eg, greater proportion of non-white participants or exclusively adolescents).6,28 Thus, the reduction in smoking we observed was probably not considered to be part of a plan to quit among smokers in the FDA condition. They nevertheless did show a tendency to reduce their consumption at least as far as their self-reports are concerned.

We found that the effect of the FDA warnings on subsequent smoking was mediated by the change in feelings about smoking, and to a lesser degree by the ability of the warnings to motivate quitting. Participants saw the FDA warnings as more able to motivate quitting and produced worse feelings about smoking at the 1-week follow-up, which in turn predicted reduced smoking. However, such mediations were only partial, as the link between exposure to the FDA warnings and reduced subsequent smoking remained significant after controlling for the mediators. Therefore, there could be other intermediate mechanisms that were involved in this effect such as reduced cue-induced craving for cigarettes,7 reduced satisfaction with smoking, and enhanced perceptions of smoking risk,6 which the current study did not assess.

It should be noted that although we found the FDA warnings to be more effective than the other two types of warnings, some prior studies suggest that warnings with fear appeals can induce defensive responses such as denial and avoidance that may impede effective health communication.29–31 Unfortunately, the design of the present study did not allow us to test whether the stronger outcome of the FDA warnings was achieved by reducing defensive responses. Nevertheless, it is possible the effectiveness of the FDA warnings (or in general warnings that contain fear appeals) can be further improved by using defensiveness reduction strategies. For example, defensive responses can be reduced by having participants reflect on personally relevant interests and values, a technique known as self-affirmation.32–34 Another way of reducing defensiveness is to accompany fear appeals with strong efficacy messages to help recipients believe that they are able to change their behavior.23,35,36

There have been other smoking-cessation interventions that can supplement pictorial warning labels. For example, a recent study shows that messages delivered in cigarette package inserts as used in Canada might enhance exterior warnings.37 Although the present study only focused on exterior warnings, the rule of image-text congruency should also apply to inserts. Another intervention is the implementation of plain packaging,38,39 which can also enhance the effectiveness of exterior warnings.40 We believe that integrating these different approaches also deserves attention as ways to potentiate the effectiveness of pictorial warnings.

There are limitations to our findings that should be recognized. First, our findings were based on one-time viewing, and we had a relatively short (ie, 7-day) follow-up period. It is possible that regular doses of exposure to the warning labels would amplify the effects on smoking-related cognition and actual smoking behavior and potentially make those effects last longer. Secondly, the study employed self-reports in measuring smoking behavior and other variables. Nevertheless, our memorability measurement, which entailed free recall instead of rating scales, yielded results that are congruent with other measures. It thus suggests that our findings are unlikely due to mere response biases in the use of rating scales. Thirdly, our sample of smokers recruited through Amazon’s Mechanical Turk was younger than the average adult smoker and likely to be more amenable to quitting. Thus, our findings may not completely generalize to older smokers, especially in regard to less smoking during the 1-week follow-up. Nevertheless, differences between experimental conditions were robust after controlling for age. It would be interesting for future studies to test whether repeated exposure to the warning labels would enhance the effect on memorability of these labels and reduction in smoking, how long the observed effects would last beyond the 7-day time window, and whether these findings apply to older smokers. Future studies may also examine whether the self-reports of reduced smoking behavior could be validated by objective biological indices, such as levels exhaled carbon monoxide or urine cotinine.

In conclusion, despite some limitations, our findings provide strong evidence in favor of pictorial cigarette warnings with emotionally evocative images that appropriately illustrate the risks of smoking, compared to those without images or with images that are merely evocative but do not address smoking-related hazards. Future research should examine the ability of image congruence to enhance the persuasiveness of images in warnings for cigarettes.

Funding

This research was funded by the Annenberg Public Policy Center and a grant from the National Cancer Institute (NCI) and the Food and Drug Administration (CA157824). However, neither NCI nor FDA necessarily endorses the conclusions drawn from the research. This work was also supported by the Vartan Gregorian post-doctoral fellowship of the Annenberg Public Policy Center and the NIH T32 post-doctoral fellowship (DA028874-05) awarded to ZS, and a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship awarded to LFE.

Declaration of Interests

None declared.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge Daniel D. Langleben and Ellen Peters for their helpful suggestions regarding the study.

References

- 1. Discount Tobacco City & Lottery, Inc, et al. v. United States, et al. 674 F.3d 509(U.S. Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit). 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Food and Drug Administration. Required warnings for cigarette packages and advertisements. Final rule. Fed Regist. 2011;76(120):36628–36777. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company, et al. v. Food & Drug Administration, et al. 696 F.3d 1205(U.S. Court of Appeals for the DC Circuit). 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Strasser AA, Tang KZ, Romer D, Jepson C, Cappella JN. Graphic warning labels in cigarette advertisements: recall and viewing patterns. Am J Prev Med. 2012;43(1):41–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Emery LF, Romer D, Sheerin KM, Jamieson KH, Peters E. Affective and cognitive mediators of the impact of cigarette warning labels. Nicotine Tob Res. 2014;16(3):263–269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Evans AT, Peters E, Strasser AA, Emery LF, Sheerin KM, Romer D. Graphic warning labels elicit affective and thoughtful responses from smokers: results of a randomized clinical trial. PLoS One. 2015;10(12):e0142879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wang AL, Romer D, Elman I, Turetsky BI, Gur RC, Langleben DD. Emotional graphic cigarette warning labels reduce the electrophysiological brain response to smoking cues. Addict Biol. 2015;20(2):368–376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ochsner KN. Are affective events richly recollected or simply familiar? The experience and process of recognizing feelings past. J Exp Psychol Gen. 2000;129(2):242–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sharot T, Delgado MR, Phelps EA. How emotion enhances the feeling of remembering. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7(12):1376–1380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Vuilleumier P. How brains beware: neural mechanisms of emotional attention. Trends Cogn Sci. 2005;9(12):585–594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bosmans A, Baumgartner H. Goal-relevant emotional information: when extraneous affect leads to persuasion and when it does not. J Cons Res. 2005;32(3):424–434. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fischer H, Andersson JL, Furmark T, Wik G, Fredrikson M. Right-sided human prefrontal brain activation during acquisition of conditioned fear. Emotion. 2002;2(3):233–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mathews A, MacLeod C. Cognitive approaches to emotion and emotional disorders. Annu Rev Psychol. 1994;45:25–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Williams JM, Mathews A, MacLeod C. The emotional Stroop task and psychopathology. Psychol Bull. 1996;120(1):3–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Constantine R, McNally RJ, Hornig CD. Snake fear and the pictorial emotional Stroop paradigm. Cognit Ther Res. 2001;25(6):757–764. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Seibert PS, Ellis HC. Irrelevant thoughts, emotional mood states, and cognitive task performance. M&C. 1991;19(5):507–513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Dolcos F, Kragel P, Wang L, McCarthy G. Role of the inferior frontal cortex in coping with distracting emotions. Neuroreport. 2006;17(15):1591–1594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Baumeister RF, Bratslavsky E, Muraven M, Tice DM. Ego depletion: is the active self a limited resource? J Pers Soc Psychol. 1998;74(5):1252–1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Buhrmester M, Kwang T, Gosling SD. Amazon’s mechanical turk: a new source of inexpensive, yet high-quality, data? Perspect Psychol Sci. 2011;6(1):3–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lang PJ, Bradley MM, Cuthbert BN. International Affective Picture System (IAPS): Affective Ratings of Pictures and Instruction Manual. Gainesville, FL: University of Florida; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Pepper JK, Cameron LD, Reiter PL, McRee AL, Brewer NT. Non-smoking male adolescents’ reactions to cigarette warnings. PLoS One. 2013;8(8):e65533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Peters E, Romer D, Slovic P, et al. The impact and acceptability of Canadian-style cigarette warning labels among U.S. smokers and nonsmokers. Nicotine Tob Res. 2007;9(4):473–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Romer D, Peters E, Strasser AA, Langleben D. Desire versus efficacy in smokers’ paradoxical reactions to pictorial health warnings for cigarettes. PLoS One. 2013;8(1):e54937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kensinger EA, Schacter DL. When the Red Sox shocked the Yankees: comparing negative and positive memories. Psychon Bull Rev. 2006;13(5):757–763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kees J, Burton S, Andrews C, Kozup J. Understanding how graphic visual warnings work on cigarette packaging. J Public Policy Market. 2010;29(2):265–276. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav Res Methods. 2008;40(3):879–891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hayes AF. An index and test of linear moderated mediation. Multivar Behav Res. 2015;50(1):1–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Andrews JC, Netemeyer RG, Kees J, Burton S. How graphic visual health warnings affect young smokers’ thoughts of quitting. J Marketing Res. 2014;51(2):165–183. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kessels LT, Ruiter RA, Wouters L, Jansma BM. Neuroscientific evidence for defensive avoidance of fear appeals. Int J Psychol. 2014;49(2):80–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. van’t Riet J, Ruiter RA. Defensive reactions to health-promoting information: an overview and implications for future research. Health Psychol Rev. 2013;7(supp1):S104–S136. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kessels LT, Ruiter RA, Jansma BM. Increased attention but more efficient disengagement: neuroscientific evidence for defensive processing of threatening health information. Health Psychol. 2010;29(4):346–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sherman DK, Cohen GL. Accepting threatening information: self–affirmation and the reduction of defensive biases. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2002;11(4):119–123. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sherman DA, Nelson LD, Steele CM. Do messages about health risks threaten the self? Increasing the acceptance of threatening health messages via self-affirmation. Person Soc Psychol Bull. 2000;26(9):1046–1058. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Falk EB, O’Donnell MB, Cascio CN, et al. Self-affirmation alters the brain’s response to health messages and subsequent behavior change. Proc Nat Acad Sci. 2015;112(7):1977–1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Rogers RW, Mewborn CR. Fear appeals and attitude change: effects of a threat’s noxiousness, probability of occurrence, and the efficacy of coping responses. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1976;34(1):54–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Witte K, Allen M. A meta-analysis of fear appeals: implications for effective public health campaigns. Health Educ Behav. 2000;27(5):591–615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Thrasher JF, Swayampakala K, Cummings KM, et al. Cigarette package inserts can promote efficacy beliefs and sustained smoking cessation attempts: a longitudinal assessment of an innovative policy in Canada. Prev Med. 2016;88:59–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Young JM, Stacey I, Dobbins TA, Dunlop S, Dessaix AL, Currow DC. Association between tobacco plain packaging and Quitline calls: a population-based, interrupted time-series analysis. Med J Aust. 2014;200(1):29–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wakefield MA, Hayes L, Durkin S, Borland R. Introduction effects of the Australian plain packaging policy on adult smokers: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2013;3(7):e003175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Thrasher JF, Rousu MC, Hammond D, Navarro A, Corrigan JR. Estimating the impact of pictorial health warnings and plain cigarette packaging: evidence from experimental auctions among adult smokers in the United States. Health Policy. 2011;102(1):41–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]