Abstract

Introduction

This study examined the association of sociodemographic characteristics, tobacco and substance use behaviors, and reasons to use cigars in young adults’ flavored and non-flavored cigar use.

Methods

Participants were 523, 18- to 29- year-old young adult college students (60.4% male; 40.9% non-Hispanic white) who reported current (past 30-day) cigar use.

Results

Almost 75% of the sample regularly chose flavored cigar products. Multilevel logistic regression analyses indicated that younger, female, and racial/ethnic minority cigar users had significantly greater odds of using flavored cigars than their counterparts. Current marijuana smokers, ever-blunt smokers, and students who reported using cigars because they were affordable and/or available in flavors they liked had a greater odds of flavored cigar use compared to their counterparts. Moreover, among dual users of cigars and cigarettes, those who cited using cigars because they were cheaper than cigarettes and because cigars felt like smoking regular cigarettes had greater odds of using flavored cigars compared to their peers. Number of days cigars were smoked and current use of other tobacco products were not associated with flavored cigar use.

Conclusions

Appealing attributes of flavored cigars have the potential to contribute to the tobacco use and subsequent nicotine addiction of younger, female, and racial/ethnic minority young adults. The wide variety of cigar flavors, their attractive price, and similarity to cigarette smoking underscore the need for additional research that links these unique traits to sustained tobacco use, and underscore the need for regulation of flavored products.

Implications

This study extends the current literature by finding that younger, female, and racial/ethnic minorities have greater odds of flavored cigar use than their peers. Flavored cigars have characteristics that appeal to members of these populations, which can contribute to their long-term use and potential for addiction.

Introduction

Young adulthood is a developmental period marked by many transitions, as well as a time for increased experimentation with products that have addictive qualities, such as those with nicotine.1,2 Alternative tobacco products—those other than cigarettes—appeal to young adults, particularly 18- to 24- year-olds.3,4 This age group comprises the largest number of alternative product users, with over 18% reporting ever-use of at least one of the following: snus, hookah, or electronic cigarettes.3 Cigars are alternative tobacco products that are rising in popularity among young adults. Cigar sales more than doubled between 2000 and 2011,5 and these products remain the second most prevalent combustible tobacco product used after cigarettes, with 5.4% of all adults in the United States reporting “every day,” “some days,” or “rare” cigar use between 2013 and 2014.4 Among young adults, almost 40% report ever cigar use,6 with anywhere from 9% to 17% reporting current (past 30-day) use.7–9 The recently finalized deeming rule provides the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) oversight over the manufacturing, distribution, and marketing of cigar products,10 however these changes do not extend to the use of characterizing flavors in the wide range of cigar products. Young adults have a demonstrated preference for flavored tobacco products compared to older adults,11 creating unique appeal in cigars that is not available in cigarettes. Additionally, cigars are relatively more affordable than cigarettes, as they are currently taxed at lower rates than cigarettes and are allowed to be purchased individually.7,12,13

Three primary types of cigars comprise this growing market. Traditional cigars are the largest in size, followed by cigarillos, which are typically slimmer than large cigars.14 Little filtered cigars are virtually indistinguishable from cigarettes in size and shape, although they are wrapped in tobacco leaves instead of paper.14,15 The Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act of 2009 banned the use of characterizing flavors in cigarettes (with the exception of menthol),16 but this regulatory authority has not been extended to cigar products. Flavors are known to mask the harshness of smoking, facilitating inhalation14 and increasing their appeal to newer and less-experienced tobacco users, such as youth and young adults.17–19 Perhaps not surprisingly, over 57% of 18- to 24- year-old young adult cigar smokers use flavored cigar products.20

Despite the rise in popularity of flavored cigars, limited research focuses on the sociodemographic differences among non-flavored and flavored cigar product users, and even fewer studies describe the specific types of cigar products used and reasons for their use. A significant preference for flavored cigars has been demonstrated among young adults, females, African Americans,19,20 and other racial/ethnic minorities, as well as those with a lower household income.20 Additionally, more daily cigar smokers report usual use of flavored cigars than those who only smoke cigars occasionally.19 Although research has also demonstrated significant correlates between current cigar product use and the likelihood of cigarette smoking, alcohol use, and marijuana use,21–23 no research has examined the associations between substance use and flavored cigar use. While cigars play a direct role in marijuana practices like blunting,24 the role of flavors in these behaviors is less well understood, though research has suggested a preference for flavored cigars among those who smoke blunts and those who smoke cigars more frequently.19

The current study extends existing research by examining sociodemographic and behavioral differences between flavored versus non-flavored cigars users in a diverse sample of 2- and 4-year college students. We examined the prevalence of flavored cigar product use, and if sociodemographic characteristics, tobacco and other substance use behaviors, and reason to use cigars were associated with flavored cigar use. Based on the prior literature, we hypothesized that: (1) younger, female, and non-white racial/ethnic minorities would have a greater odds of flavored cigar use than their counterparts; (2) more days smoking a cigar in the past 30 days and current use of other tobacco products would be associated with greater odds of flavored cigar use; and (3) current marijuana users would have greater odds of flavored cigar use. We also examined the association between flavored cigar use and reasons to use cigars as well as the association between flavored cigar use and binge drinking behavior. Findings from this study may provide evidence that attributes of flavored cigars potentially increase the numbers of users of these products, who may eventually become nicotine-addicted tobacco users.

Methods

Participants

Participants were current cigar users drawn from the baseline wave (November 2014–February 2015) of the Marketing and Promotions across Colleges in Texas project (Project M-PACT), a rapid response, web-based survey assessing the tobacco use behaviors of 18- to 29- year-old college students. Of the 5482 participants in Project M-PACT, 2010 (36.7%) reported using a cigar product in their lifetime and 529 (9.7%) reported past 30-day (current) cigar use. Six of the 529 current cigar users did not provide any answers to flavored or non-flavored cigar use, resulting in 523 cases in the current study sample. Participants had an average age of 21.3 years old (SD = 2.5 years) and were 60.4% male. Regarding race/ethnicity, 40.9% of students were non-Hispanic white, 31.2% were Hispanic/Latino, 10.3% were African American/black, 9.4% were Asian, and 8.2% reported another race/ethnicity or two or more races/ethnicities. Four-year university attendees, compared with 2-year, comprised 92.0% of the sample, and 87.2% of participants had at least one parent with a greater-than-high school education.

To participate in Project M-PACT, participants were required to be full- or part-time degree- or certificate-seeking undergraduate students, attending a 4-year college or a vocational/technical program at a 2-year college. Recruitment at 2-year colleges was limited to students enrolled in vocational/technical programs (eg, welding, air conditioning, and heating, etc.), because they have an elevated prevalence of cigarette use,25 and as such are at elevated risk for the use of alternative tobacco products. Participants were also required to be 18–29 years old. For those who were 26–29 years old, recruitment was restricted to lifetime tobacco users. Lifetime tobacco use was defined by having ever smoked at least 100 cigarettes, at least 20 cigars, or having ever used smokeless/spit/chewing tobacco at least 20 times. Because the larger project aimed to examine transitions in tobacco use, and since initiation is unlikely to occur after the age of 26,26 lifetime non-tobacco users over the age of 26 were excluded from participation. To further ensure adequate numbers of tobacco users, 347 18- to 25-year-old lifetime tobacco users were oversampled.

Procedure

Participants were recruited from 24 2- and 4-year colleges in the five counties around four target cities (Austin, Dallas/Fort Worth, Houston, and San Antonio) in Texas. Email addresses were obtained through public records requests, and project staff emailed invitations to students at 15 colleges. The remaining nine colleges did not provide student addresses to project staff, and instead the colleges emailed students a participation invitation on the project’s behalf. Eligible students who wished to participate in the study provided informed consent and then completed the online survey. All participants were compensated with a $10 e-gift card and entered into a drawing to win one of twenty $50 e-gift cards. More than 13 000 students (n = 13 714) were eligible to participate in the study and of these, 5482 students (40%) provided consent and completed the survey. This rate of participation is similar to, or exceeds, those of other online surveillance studies of young adult college students.27–29

Measures

The 175-item survey was modeled after national tobacco assessment instruments, primarily the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH)30 study and the National Youth Tobacco Survey (NYTS).31 Measures for Project M-PACT were initially reviewed by nine tobacco control experts, and all final survey modifications were completed after an iterative process of cognitive interviewing with a separate sample of 25 young adults.32

Sociodemographic Characteristics

Questions related to sociodemographic characteristics were treated as categorical variables. These included age, sex, race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, Hispanic/Latino, African American/black, Asian, and other/multiple), and school type (either 4-year university or 2-year vocational). Age was analyzed as two groups, younger (18–24 years old) versus older (25–29 years old). Additionally, the highest level of parental education of a participant’s mother or father was analyzed as a dichotomous variable. Students whose parents completed high school or less were coded as 0 and those whose parents held an associate’s degree or higher were coded as 1.

Cigar Use

Research indicates that some respondents have difficulty reporting the type of cigar product they smoke.33 For this reason, brand names (eg, Phillie Blunts, Backwoods) were included in the cigar section opening description as well as cigar questions. Ever-cigar use was assessed by asking “Have you ever tried either of these cigar product types as intended (ie, with tobacco), even one or two puffs? (1) Large cigars like Macanudo, Romeo y Julieta, Arturo Fuente, Garcia y Vega, Backwoods, etc. (2) Cigarillos or little filtered cigars like Black and Mild, Swisher Sweets, Dutch Masters, Phillie Blunts, Santa Fe, etc.” Days of current cigar use were then ascertained of ever-users by asking how many of the past 30 days they smoked a cigar product. Those who reported smoking cigars on one or more of the past 30 days comprised our study sample. In analyses, number of days smoking a cigar in the past 30 days was treated as a continuous variable. To establish the type of cigar currently used, participants selected one photograph of the product that most closely resembled the type of cigar smoked most often in the past 30 days, choosing among photos of large cigars, slimmer cigarillos, or little filtered cigars, which closely resemble cigarettes. The use of flavored cigars was assessed by asking current users to check all of their usual flavors among cigar products flavored to taste like: “tobacco,” “menthol or mint,” “fruit (eg, grape),” “spices (eg, cloves),” “coffee or an alcoholic drink (eg, wine, cognac),” “other,” and “I don’t remember, but I know it is flavored.” These questions were recoded into dichotomous variables, distinguishing cigar smokers who reported using any flavors (coded as 1) from those who did not choose any flavors (coded as 0). Exclusive selection of “tobacco” flavor was categorized as non-flavored use, while any other selection designated flavored use.

Other Tobacco Use

Current, or past 30-day, use of four other products (cigarettes, smokeless tobacco, hookah, and e-cigarettes) was assessed with items adapted from the NYTS and PATH surveys. Current use of cigarettes and smokeless tobacco were assessed with the questions, “During the past 30 days, on how many days did you smoke/use _____?” Current use of hookah was assessed with the question, “During the past 30 days, how many days did you smoke hookah as intended (ie, with tobacco)?” Current use of e-cigarettes was assessed with the question, “During the past 30 days, have you used any ENDS product (ie, an e-cigarette, vape pen, or e-hookah), even one or two puffs, as intended (ie, with nicotine cartridges and/or e-liquid/e-juice)?” The phrase “as intended” was used to emphasize the product role as tobacco/nicotine delivery, not marijuana or other substances. These questions were each recoded into dichotomous variables for past 30-day use: those who reported using the product one or more days in the past 30 days (current users, coded as 1) and those who had not used the product on any of the past 30 days (coded as 0).

Substance Use

Participants were asked, “During the past 30 days, how many occasions, or times, if any, have you used marijuana? (Other names for marijuana are pot and weed).” Answer options were “0 times,” “1–2 times,” “3–5 times,” “6–9 times,” “10–19 times,” “20–39 times,” or “40 or more times.” Current marijuana use was coded as 1 (smoked marijuana on one or more of the past 30 days) or 0 (smoked marijuana on zero of the past 30 days). Ever use of smoking marijuana in a cigar was ascertained by asking “Have you ever smoked marijuana in a large cigar, cigarillo, or ‘blunt’?” and coded as 1 (yes) or 0 (no). Finally, binge drinking behavior in the past 14 days was established by asking, “During the past 14 days, on how many days did you have 5 or more drinks of alcohol in a row?” Answer choices were “0 days,” “1 or 2 days,” “3 to 5 days,” “6 to 9 days,” or “10 to 14 days.” Binge drinking was coded as 1 (reported binge drinking behavior on one or more of the past 14 days) or 0 (binge drinking behavior was reported on zero of the past 14 days.)

Reasons to Use Cigars

All current cigar users were asked to choose among seven reasons for smoking cigar products, adapted from the PATH survey: “my friends use them,” “I like the way they look,” “they are affordable,” “people in the media or other public figures use them,” “they come in flavors I like,” “the advertising for cigar products appeals to me,” and “other.” Each reason was then coded as 1 (a selected reason) or 0 (not selected). Participants who reported both current cigarette and current cigar use were asked an additional question with seven reasons to smoke cigars as compared to cigarettes: “they seem less harmful than regular cigarettes,” “they seem less harmful to people around me than regular cigarettes,” “I want to quit or cut down on smoking regular cigarettes,” “using cigar products feels like smoking regular cigarettes,” “I want to use them instead of other tobacco products,” “they are cheaper than regular cigarettes,” and “other.” Each of these reasons was also coded 1 (a selected reason) or 0 (not selected).

Data Analysis

To test the three study hypotheses and determine if the study variables were associated with current flavored cigar use, multiple sets of multilevel logistic regression analyses, one for each independent variable, were conducted using R 3.2. Multilevel analyses accommodated the non-independence, or clustering, of participants in the 24 colleges by including school in each model as a random effect. Current flavored versus non-flavored cigar use served as the dependent variable in each model. The first analyses used sociodemographic characteristics as independent variables to determine their association with flavored cigar use. Subsequent analyses used tobacco use behavior, other substance use behavior, and reasons to use cigars as independent variables while including sociodemographic characteristics as covariates. Reasons to use cigars were assessed in two sets: one for all current users of cigars and a second set for current dual users of cigars and cigarettes.

Results

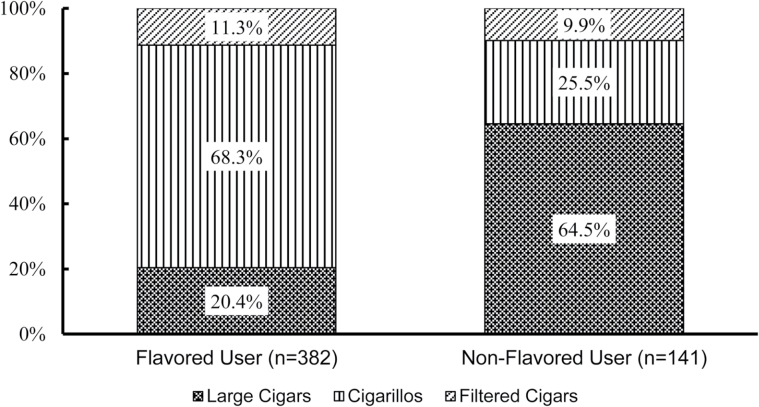

Prior to examining study hypotheses, flavored cigar use was examined. As reported in Figure 1, 73.0% of the sample reported usually smoking flavored cigars (n = 382) with the remainder usually smoking only tobacco flavor. Among the multiple cigar flavors participants could choose smoking in the past month, fruit flavor was the most popularly endorsed (66.2%), followed by coffee/alcoholic drinks (31.9%), spices (eg, clove) (28%) and finally menthol/mint (22%). The majority of flavored cigar users reported smoking cigarillos (68.3%), while most non-flavored cigar users reported smoking large cigars (64.5%). Multilevel logistic regression indicated a lower odds of flavored cigar use among large cigar users (OR = 0.12, 95% CI = 0.07–0.19) and little filtered cigar users (OR = 0.43, 95% CI = 0.21–0.86) compared to cigarillo users.

Figure 1.

Types of cigar products primarily used by young adult current flavored and non-flavored cigar users (N=523).

Sociodemographic Characteristics

As reported in Table 1, younger participants (ages 18–24) had 2.17 greater odds (95% CI = 1.13–4.17) of choosing flavored cigars compared to older participants aged 25–29 years old. While more than half of flavored cigar users were male, they had significantly lower odds of choosing flavored cigars than females (AOR = 0.28, 95% CI = 0.18–0.45). Additionally, Hispanic participants had 2.22 greater odds (95% CI = 1.36–3.64), African American participants had 3.24 times greater odds (95% CI = 1.43–7.37), and Asian participants had 2.21 greater odds (95% CI = 1.05–4.65), of choosing flavored cigars over non-flavored cigars as compared to their non-Hispanic white cigar smoking peers.

Table 1.

Multilevel Logistic Regression of Current Flavored Cigar Use Regressed on Sociodemographic Characteristics Among Current Young Adult Cigar Product Users (N = 523)

| Overall N = 523 | Flavored n = 382 | Non-flavored n = 141 | Odds ratio of flavored use | 95 % CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||||

| 25–29 years old | 9.6 | 7.9 | 14.2 | REF | |

| 18–24 years old | 90.4 | 92.1 | 85.8 | 2.17 | (1.13–4.17) |

| Sex | |||||

| Female | 39.5 | 46.8 | 19.9 | REF | |

| Male | 60.5 | 53.3 | 80.1 | 0.28 | (0.18–0.45) |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 40.9 | 35.3 | 56.0 | REF | |

| Hispanic | 31.2 | 34.3 | 22.7 | 2.22 | (1.36–3.64) |

| African American/black | 10.3 | 12.0 | 5.7 | 3.24 | (1.43–7.37) |

| Asian | 9.4 | 9.9 | 7.8 | 2.21 | (1.05–4.65) |

| Other/Multiple | 8.2 | 8.4 | 7.8 | 1.55 | (0.73–3.32) |

| School type | |||||

| 2 year | 8.0 | 9.4 | 4.3 | REF | |

| 4 year | 92.0 | 90.6 | 95.7 | 0.41 | (0.15–1.12) |

| Parental education | |||||

| Lower (high school graduate and below) | 11.8 | 12.2 | 10.7 | REF | |

| Higher (at least some college) | 88.2 | 87.8 | 89.3 | 1.00 | (0.53–1.90) |

Each independent variable (sociodemographic characteristic) is a separate multilevel model. Each model accommodates the clustering of students within the 24 schools.

Tobacco Use Behaviors

Number of days of cigar use in the past 30 days was not associated with flavored cigar use (see Table 2). Regarding other tobacco use, 432 (82.6%) participants reported currently using another tobacco product in addition to cigars. Of these poly-users, 74.1% were flavored cigar users and 25.9% were non-flavored cigar users. However, there were no associations between the current use of any other tobacco product and flavored cigar use (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Multilevel Logistic Regression of Current Flavored Cigar Use Regressed on Current Tobacco Use, Substance Use, and Reasons to Use Cigars Among Young Adult Cigar Product Users (N = 523)

| Overall N = 523 | Flavored n = 382 | Non-flavored n = 141 | Adjusted odds ratio of flavored use | 95 % CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tobacco use (%) | |||||

| Days of cigar use in past 30 days: mean (SD) | 3.8 (5.55) | 4.2 (5.86) | 2.72 (4.45) | 1.04 | (0.99–1.10) |

| Current cigarette use | 57.2 | 59.4 | 51.1 | 1.25 | (0.82–1.92) |

| Current ENDS use | 44.2 | 45.0 | 41.8 | 1.02 | (0.66–1.56) |

| Current hookah use | 45.7 | 47.9 | 39.7 | 1.31 | (0.85–2.01) |

| Current smokeless use | 11.9 | 10.6 | 15.6 | 0.91 | (0.49–1.70) |

| Substance use (%) | |||||

| Current marijuana use | 55.6 | 60.7 | 41.8 | 1.84 | (1.20–2.83) |

| Ever used marijuana in a cigar | 49.6 | 55.4 | 34.0 | 2.17 | (1.40–3.36) |

| Past 14 days binge drinking | 57.6 | 56.8 | 59.6 | 1.00 | (0.65–1.54) |

| Reasons to use cigars (% endorsing each reason) | |||||

| Friends use | 42.8 | 44.0 | 39.7 | 1.25 | (0.81–1.91) |

| Like the way they look | 18.9 | 17.5 | 22.7 | 1.05 | (0.62–1.77) |

| Affordable | 33.8 | 39.8 | 17.7 | 2.76 | (1.66–4.58) |

| People in media or public figures use | 4.6 | 3.9 | 6.4 | 0.71 | (0.28–1.85) |

| Come in flavors I like | 45.5 | 54.7 | 20.6 | 5.01 | (3.06–8.21) |

| Appealing advertising | 3.3 | 3.9 | 1.4 | 2.96 | (0.63–13.81) |

| Other | 32.3 | 26.4 | 48.2 | 0.43 | (0.27–0.66) |

Each behavior and reason is a separate model, adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, school type, and parental education. Each multilevel model accommodates the clustering of students within the 24 schools.

Substance Use Behaviors

Over half of all current cigar smokers currently used marijuana and had participated in binge drinking behavior in the past 14 days (see Table 2). Those who reported marijuana use in the past 30 days had 1.84 times greater odds (95% CI = 1.20–2.83) of currently smoking flavored cigars as their non-marijuana-smoking peers. Participants who reported ever smoking marijuana in a cigar had 2.17 times greater odds (95% CI = 1.40–3.36) of currently smoking flavored cigars compared to their peers. There was no significant association between binge drinking behavior in the past 14 days and flavored cigar use.

Reasons to Smoke Cigars

The first set of analyses regarding reasons to use cigars was asked of the full sample (see Table 2). Compared to their peers, cigar smokers who endorsed affordability as a reason to smoke cigars had 2.76 times greater odds (95% CI = 1.66–4.58) of currently smoking flavored cigars. Participants who chose the reason “because they come in flavors I like” had 5.01 greater odds (95% CI = 3.06–8.21) of smoking flavored cigars compared to participants who did not endorse this as a reason.

The second set of analyses regarding reasons to smoke cigars as they compared to cigarettes was asked of dual users of cigars and cigarettes (n = 299, Table 3). Participants who endorsed the reason “because it is like smoking cigarettes” had 5.63 times greater odds (95% CI = 1.62–19.61) of being flavored cigar smokers than their peers. Participants who chose the reason that cigars were “cheaper than cigarettes” had 6.24 greater odds (95% CI = 1.84–21.16) of currently smoking flavored cigars than participants who did not choose this reason.

Table 3.

Multilevel logistic regression of current flavored cigar use on reasons to use cigars compared with cigarettes among dual users of cigars and cigarettes (N=299)

| Overall (N = 299) % | Current users of flavored cigars (n = 227) % | Current users of non-flavored cigars (n = 72) % | Adjusted odds ratio of flavored use | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Less harmful than cigarettes | 16.4 | 18.9 | 8.3 | 2.47 | (0.95–6.41) |

| Less harmful to others than cigarettes | 6.7 | 7.5 | 4.2 | 2.58 | (0.55–12.03) |

| To quit/cut down on cigarettes | 5.0 | 5.3 | 4.2 | 1.54 | (0.38–6.21) |

| Like smoking cigarettes | 14.4 | 17.6 | 4.2 | 5.63 | (1.62–19.61) |

| To use instead of other tobacco products | 25.4 | 25.1 | 26.4 | 1.15 | (0.60–2.19) |

| Cheaper than cigarettes | 20.7 | 26.0 | 4.2 | 6.24 | (1.84–21.16) |

| Other | 48.8 | 44.1 | 63.9 | 0.41 | (0.23–0.75) |

Each reason is a separate model, adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, school type, and parental education. Each multilevel model accommodates the clustering of students within the 24 schools.

Discussion

This study extends existing research by examining the sociodemographic and behavioral correlates of flavored cigar use in a diverse sample of young adult college students. Consistent with other research19,20 and our hypotheses, analyses demonstrated that flavored cigars were popular among this sample of young adults, and that sociodemographic characteristics, marijuana use behaviors, and certain reasons for using cigars were associated with flavored cigar use. Younger participants had significantly greater odds of using flavored cigar products than their older peers, which aligns with previous research indicating a preference for flavored products among young users that declines with age,19 and also aligns with research that documents direct marketing of these products to youth and young adults.18,34 While more male participants reported both flavored and non-flavored cigar use compared to females, findings demonstrated that females had a greater odds than males of being flavored cigar users. Flavors may therefore play a role in diminishing sex differences in cigar use, as female cigar smokers may be more likely to select cigars if they are available in flavors. Furthermore, flavors are added to tobacco to mask the harshness of smoking and increase appeal for new and inexperienced smokers.18 The use of flavored cigars may lead to regular use and potentially create lifetime-addicted smokers who might not otherwise choose to smoke, including young female smokers. Lastly, advertising that targets racial and ethnic minorities may help explain the preference for flavored cigars among racial/ethnic minority participants in this sample.17 Racial and ethnic minority groups have a well-documented history of bearing a greater proportional morbidity and mortality from tobacco use than their White counterparts,35 and these analyses suggest flavored use as a possible contributor to this elevated tobacco burden.

Contrary to our hypotheses, there was no association between number of days cigars were smoked in the past 30 days and the odds of being a flavored cigar user. This is surprising in light of the overwhelming preference for cigarillos among flavored cigar users in this sample. Cigarillos are associated with more frequent use19,36 compared to large cigars, which may be smoked infrequently or on special occasions.23 Regardless, research demonstrates that even intermittent smoking leads to symptoms of dependence37,38 particularly during young adulthood when addiction is solidified.39 Therefore, any cigar use during this developmental period poses risks for subsequent nicotine addiction. Furthermore, the lack of association between days smoked and flavored use may be related to findings regarding dual- or poly-tobacco use. While the use of multiple tobacco products was not associated with flavored cigar use, over 80% of the entire cigar-using sample reported concurrent use of other tobacco products. Poly-tobacco use is increasingly prevalent among young adults and of major concern for public health officials.6 Despite misperceptions among many users that cigars are less harmful and more natural than cigarettes,40–42 they are not considered a safe alternative to cigarettes, and their use is associated with similarly serious negative health outcomes.20,43 Concurrent use of cigars and at least one other product, particularly another combustible product like cigarettes, may therefore result in negative health effects that are additive or even multiplicative. Studies that examine type of cigar smoked and longitudinal changes in tobacco use patterns will be valuable in elucidating the role of cigar type in the smoking behaviors of young adults.

Although there was no association between binge drinking behavior and flavored cigar use, the association between marijuana use behaviors and flavored cigar use was significant. Current marijuana smokers and those who reported ever having used a cigar to smoke marijuana, (ie, blunting) had greater odds of using flavored cigars than their peers. Previous research has also demonstrated a preference for flavored cigar products among blunt smokers.21 Smoking blunts may also contribute to the dual- and poly-tobacco use of this sample, as some research highlights the popularity of “blunt chasing,” where users smoke little filtered cigars or cigarettes immediately after smoking a marijuana blunt.44

Only a few reasons to smoke cigars appeared distinctly associated with flavored cigar use. Among all cigar smokers, the odds of being a flavored cigar user were significantly greater for those who chose affordability as a reason to smoke cigars, which may be due in part to smoking cigarillos versus large cigars. That is, cigarillos are often sold individually or in packs of two for less than $17 whereas large cigars tend to be more expensive. Additionally, when examining reasons for cigar use among current dual users of cigars and cigarettes, reasons related to cigarette substitution appeared evident. Students who smoked cigars because they were similar to cigarettes or cheaper than cigarettes had greater odds of being flavored users. Existing research indicates that users frequently substituted cigars for cigarettes following restrictions of the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act,13 a substitution that may also be evident in this sample.

This study fills some gaps in the existing literature by highlighting behavioral correlates of flavored cigar smoking and features of flavored cigars and that set these products apart from non-flavored cigars, but results should be considered in light of some limitations. These data are cross-sectional; thus, it remains to be seen if flavored cigars uniquely contribute to increased or sustained tobacco use or other negative health outcomes. Additionally, although our sample is racially/ethnically diverse and drawn from 24 2- and 4-year colleges, it is not a representative sample and findings may not be generalizable to other college students, nor to the population of young adults ages 18–29 who do not attend college. Small group sizes also limit the generalizability of findings, and research focused on larger and more diverse samples of cigar users would strengthen reported conclusions. Additional longitudinal research with nationally representative samples of college students and other young adults is needed to replicate study findings and identify other correlates of flavored cigar use, as well as differences among flavored and non-flavored cigar users.

Alternative tobacco products such as cigars have the potential to “re-normalize” cigarette use,45 helping established smokers sustain their nicotine habit or generate new lifetime nicotine habits,3 especially among those who initiate tobacco use at a younger age.46 Younger, female, and racial/ethnic minority cigar smokers with demonstrated preferences for flavored cigars can become dependent upon nicotine through their use of flavored products, especially when cigars are available for purchase singly or in small packs of two and three.7 Future research that emphasizes how flavors contribute to the sustained use of cigar products and poly-use of other tobacco products will be valuable in tailoring intervention efforts, as will exploring potentially distinct user groups by types of cigars smoked. Until recently, cigars have been an unregulated alternative tobacco product that pose significant risks to health,43 and they possess attributes like flavors that appeal to young adults in large numbers, which likely contributes to the tobacco burden that persists despite declining rates of cigarette use. Findings from this study provide evidence that the newly finalized regulations that extend FDA authority to the manufacturing, distribution, and marketing of cigars would be strengthened by including regulations of flavors, an important step in protecting the health of potential users of these products, particularly younger, female, and racial/ethnic minority young adults.

Funding

Research reported in this publication was supported by grant number [1 P50 CA180906] from the National Cancer Institute and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Center for Tobacco Products. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH or the FDA.

Declaration of Interests

None declared.

References

- 1. Moss HB, Chen CM, Yi HY. Early adolescent patterns of alcohol, cigarettes, and marijuana polysubstance use and young adult substance use outcomes in a nationally representative sample. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014;136:51–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ling PM, Glantz SA. Why and how the tobacco industry sells cigarettes to young adults: evidence from industry documents. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(6):908–916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. McMillen R, Maduka J, Winickoff J. Use of emerging tobacco products in the United States. J Environ Public Health. 2012;2012:989474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hu SS, Neff L, Agaku IT, et al. Tobacco product use among adults - United States, 2013-2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(27):685–691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Centers for Disease Conrol and Prevention. Consumption of cigarettes and combustible tobacco-United States, 2000–2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61(30):565–569. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Richardson A, Williams V, Rath J, Villanti AC, Vallone D. The next generation of users: prevalence and longitudinal patterns of tobacco use among US young adults. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(8):1429–1436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Milam AJ, Bone LR, Byron MJ, et al. Cigarillo use among high-risk urban young adults. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2013;24(4):1657–1665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Agaku IT, King BA, Husten CG, et al. ; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Tobacco product use among adults–United States, 2012-2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63(25):542–547. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Messer K, White MM, Strong DR, et al. Trends in use of little cigars or cigarillos and cigarettes among U.S. smokers, 2002-2011. Nicotine Tob Res. 2015;17(5):515–523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Food and Drug Administration. Extending Authorities to All Tobacco Products, Including E-Cigarettes, Cigars, and Hookah www.fda.gov/TobaccoProducts/Labeling/ucm388395.htm Accessed May 7, 2016.

- 11. Smith DM, Bansal-Travers M, Huang J, Barker D, Hyland AJ, Chaloupka F. Association between use of flavoured tobacco products and quit behaviours: findings from a cross-sectional survey of US adult tobacco users. Tob Control. 2016;25(suppl 2):ii73–ii80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids. Fact Sheets www.tobaccofreekids.org/facts_issues/fact_sheets/toll/tobacco_kids/marketing/ Accessed February 3, 2016.

- 13. Delnevo CD. Smokers’ choice: what explains the steady growth of cigar use in the U.S.?Public Health Rep. 2006;121(2):116–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kostygina G, Glantz SA, Ling PM. Tobacco industry use of flavours to recruit new users of little cigars and cigarillos. Tob Control. 2016;25(1):66–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Delnevo CD, Hrywna M. A whole nother smoke or a cigarette in disguise: how RJ Reynolds reframed the image of little cigars. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(8):1368–1375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. United States Congress. Committee on Energy and Commerce. Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act (H.R. 1256). Washington, DC: U.S. G.P.O; 2009. http://congressional.proquest.com/congcomp/getdoc?CRDC-ID=CMP-2009-HEC-0014 Accessed February 4, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Connolly GN. Sweet and spicy flavours: new brands for minorities and youth. Tob Control. 2004;13(3):211–212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Carpenter CM, Wayne GF, Pauly JL, Koh HK, Connolly GN. New cigarette brands with flavors that appeal to youth: tobacco marketing strategies. Health Aff (Millwood). 2005;24(6):1601–1610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Delnevo CD, Giovenco DP, Ambrose BK, Corey CG, Conway KP. Preference for flavoured cigar brands among youth, young adults and adults in the USA. Tob Control. 2015;24(4):389–394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. King BA, Dube SR, Tynan MA. Flavored cigar smoking among U.S. adults: findings from the 2009-2010 National Adult Tobacco Survey. Nicotine Tob Res. 2013;15(2):608–614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sterling K, Berg CJ, Thomas AN, Glantz SA, Ahluwalia JS. Factors associated with small cigar use among college students. Am J Health Behav. 2013;37(3):325–333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cullen J, Mowery P, Delnevo C, et al. Seven-year patterns in US cigar use epidemiology among young adults aged 18-25 years: a focus on race/ethnicity and brand. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(10):1955–1962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Richardson A, Rath J, Ganz O, Xiao H, Vallone D. Primary and dual users of little cigars/cigarillos and large cigars: demographic and tobacco use profiles. Nicotine Tob Res. 2013;15(10):1729–1736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Soldz S, Huyser DJ, Dorsey E. The cigar as a drug delivery device: youth use of blunts. Addiction. 2003;98(10):1379–1386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Loukas A, Murphy JL, Gottlieb NH. Cigarette smoking and cessation among trade or technical school students in Texas. J Am Coll Health. 2008;56(4):401–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Preventing tobacco use among youth and young adults: A report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2012. www. surgeongeneral.gov/library/preventing-youth-tobacco-use/full-report.pdf Accessed May 8, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Berg CJ, Haardoerfer R, Escoffery C, Zheng P, Kegler M. Cigarette users’ interest in using or switching to electronic nicotine delivery systems for smokeless tobacco for harm reduction, cessation, or novelty: a cross-sectional survey of US adults. Nicotine Tob Res. 2015;17(2):245–255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Berg CJ, Haardörfer R, Lewis M, et al. DECOY: documenting experiences with cigarettes and other tobacco in young adults. Am J Health Behav. 2016;40(3):310–321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Velazquez CE, Pasch KE, Laska MN, Lust K, Story M, Ehlinger EP. Differential prevalence of alcohol use among 2-year and 4-year college students. Addict Behav. 2011;36(12):1353–1356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. National Institutes of Health. Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) 2013. https://pathstudyinfo.nih.gov/UI/HomeMobile.aspx Accessed November 2, 2013.

- 31. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Youth Tobacco Survey (NYTS) 2013. www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/surveys/nyts/index.htm Accessed November 2, 2013.

- 32. Hinds JT, III, Loukas A, Chow S, et al. Using cognitive interviewing to better assess young adult e-cigarette use. Nicotine Tob Res. 2016;18(10):1998–2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Terchek JJ, Larkin EM, Male ML, Frank SH. Measuring cigar use in adolescents: inclusion of a brand-specific item. Nicotine Tob Res. 2009;11(7):842–846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lewis MJ, Wackowski O. Dealing with an innovative industry: a look at flavored cigarettes promoted by mainstream brands. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(2):244–251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The health consequences of smoking - 50 years of progress: A report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2014. www.surgeongeneral.gov/library/reports/50-years-of-progress/exec-summary.pdf Accessed May 8, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Corey CG, King BA, Coleman BN, et al. ; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Little filtered cigar, cigarillo, and premium cigar smoking among adults–United States, 2012-2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63(30):650–654. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. DiFranza JR, Savageau JA, Rigotti NA, et al. Development of symptoms of tobacco dependence in youths: 30 month follow up data from the DANDY study. Tob Control. 2002;11(3):228–235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Caraballo RS, Novak SP, Asman K. Linking quantity and frequency profiles of cigarette smoking to the presence of nicotine dependence symptoms among adolescent smokers: findings from the 2004 National Youth Tobacco Survey. Nicotine Tob Res. 2009;11(1):49–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Sussman S, Arnett JJ. Emerging Adulthood: Developmental Period Facilitative of the Addictions. Eval Health Prof. 2014;37(2):147–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Jolly DH. Exploring the use of little cigars by students at a historically black university. Prev Chronic Dis. 2008;5(3):A82. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Malone RE, Yerger V, Pearson C. Cigar risk perceptions in focus groups of urban African American youth. J Subst Abuse. 2001;13(4):549–561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Page J, Evans S. Cigars, cigarillos, and youth: emergent patterns in subcultural complexes. J Ethn Subst Abuse. 2004;2(4):63–76. [Google Scholar]

- 43. National Cancer Institute (U.S.). Cigars: Health Effects and Trends. Bethesda, Md: U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute; 1998, no. 98–4302. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Sifaneck SJ, Johnson BD, Dunlap E. Cigars-for-blunts: choice of tobacco products by blunt smokers. J Ethn Subst Abuse. 2005;4(3–4):23–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Cobb C, Ward KD, Maziak W, Shihadeh AL, Eissenberg T. Waterpipe tobacco smoking: an emerging health crisis in the United States. Am J Health Behav. 2010;34(3):275–285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Villanti AC, Richardson A, Vallone DM, Rath JM. Flavored tobacco product use among U.S. young adults. Am J Prev Med. 2013;44(4):388–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]