Abstract

Introduction:

Relative risks (RRs) for coronary heart disease (CHD) by cigarettes/day exhibit a concave pattern, implying the RR increase with each additional cigarette/day consumed decreases with greater intensity. Interpreting this pattern faces limitations, since cigarettes/day alone does not fully characterize smoking-related exposure. A more complete understanding of smoking and CHD risk requires a more comprehensive representation of smoking.

Methods:

Using Poisson regression, we applied a RR model in pack-years and cigarettes/day to analyze two diverse cohorts, the US Agricultural Health Study, with 4396 CHD events and 1 425 976 person-years of follow-up, and the Finnish Alpha-Tocopherol, Beta-Carotene Cancer Prevention Study, with 5979 CHD events and 486 643 person-years.

Results:

In both cohorts, the concave RR pattern with cigarettes/day was consistent with cigarettes/day modifying a linear RR association for CHD by pack-years within categories of cigarettes/day, indicating that strength of the pack-years association depended on cigarettes/day (p < .01). For example, at 50 pack-years (365 000 total cigarettes), estimated RRs of CHD were 2.1 for accrual at 20 cigarettes/day and 1.5 for accrual at 50 cigarettes/day.

Conclusions:

RRs for CHD increased with pack-years with smoking intensities affecting the strength of association. For equal pack-years, smoking fewer cigarettes/day for longer duration was more deleterious than smoking more cigarettes/day for shorter duration. We have now observed inverse smoking intensity effects in multiple cohorts with differing smoking patterns and other characteristics, suggesting a common underlying phenomenon.

Implications:

Risk of CHD increases with pack-years of smoking, but accrual intensity strongly influences the strength of the association, such that smoking fewer cigarettes/day for longer duration is more deleterious than smoking more cigarettes/day for shorter duration. This observation offers clues to better understanding biological mechanisms, and reinforces the importance of cessation rather than smoking less to reduce CHD risk.

Introduction

Investigators have consistently reported a concave relationship for the relative risk (RR) of coronary heart disease (CHD) with increasing cigarettes/day.1–3 This pattern implies that the RR increase for each additional cigarette/day consumed decreases with greater intensity. While this concave pattern for the RRs by cigarettes/day occurs frequently, the precise smoking rate-dependent biologic mechanisms responsible for the nonlinearity remain uncertain.1–8

One possible impediment to an improved understanding is that cigarettes/day, and indeed any single metric, provides an incomplete characterization of smoking-related exposure and hence disease risk. A comprehensive description of smoking-related risks requires a more comprehensive representation of exposure. Analysis of cigarette smoking typically calculates RRs by individual metrics, cigarettes/day, smoking duration, and pack-years, then proceeds either to adjust one metric for another or to cross-tabulate RRs for two factors with never-smokers as referent. The most common approach computes joint RRs for cigarettes/day and smoking duration, although this choice leads to problems of interpretation.9–11 For example, in a log-linear RR model with cigarettes/day and duration, the cigarettes/day parameter represents a unit increase in the ln(RR) per cigarette/day with duration held fixed. Because duration is fixed, RRs for increasing cigarettes/day necessarily embed increasing pack-years. For 30 years of smoking, RRs at 20 and 30 cigarettes/day include not only different smoking intensities but also different total exposures, that is, 30 and 45 pack-years, respectively, or 110 000 (≈ 15 × 20 × 365.25) additional cigarettes. Similarly, for a fixed cigarettes/day, RRs at different durations embed effects of increased pack-years. Hence, one cannot interpret the cigarettes/day and duration parameters as distinct, unrelated effects.

Our approach jointly analyzes pack-years and cigarettes/day, which reflects the extent that smoking rates modify the RR trend with pack-years. Cigarettes/day then represents the relative influence of exposure accrual on the RR for a given pack-years, that is, the RR differential at a fixed pack-years when delivered at lower smoking intensities for longer durations or higher intensities for shorter durations. This characterization reinterprets the nonlinear RRs with cigarettes/day as a “delivery rate” effect. For example, our analysis estimates different RRs for individuals who smoked 20 cigarettes/day for 50 years or 30 cigarettes/day for 33.3 years or 50 cigarettes/day for 20 years, even though total exposure is equivalent, 50 pack-years (~365 000 cigarettes).

An analysis of data from the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study indicated that the concave pattern with cigarettes/day reflected an inverse delivery rate effect embedded within pack-years associated linear RRs, that is, for a given number of pack-years, smoking at lower intensity for longer duration incurred a greater risk than smoking at higher intensity for shorter duration.12 In the current article, we examine data from two diverse cohorts to evaluate whether the inverse smoking intensity effect occurs for CHD in other populations, thus suggesting a more general phenomenon.

Material and Methods

Agricultural Health Study

The Agricultural Health Study (AHS) is a prospective cohort study of licensed pesticide applicators and their spouses residing in North Carolina and Iowa (n = 89 656).13 Between 1993 and 1997, the study enrolled private pesticide applicators (mainly farmers, n = 52 394), their spouses (n = 32 246) and commercial pesticide applicators (n = 4916). Pesticide applicator enrollees completed a self-administered questionnaire, covering pesticide use, farming activities, demographics and health, when they applied for or renewed their restricted-use pesticide licenses. Spouses enrolled upon completion of take-home questionnaires given to married private applicators. In 1999–2003 (phase 2), 2005–2010 (phase 3) and 2013–2015 (phase 4), study personnel administered to private applicators and spouses either a computer-assisted telephone interview (phases 2 and 3) or mail questionnaire (phase 4) that included questions on medical history (phases 2–4) and smoking characteristics (phases 3 and 4). Personnel also re-contacted commercial applicators in 2004–2005 (phase 2). Questionnaires and further details are available at http://aghealth.nih.gov/. This analysis used AHS data releases P1REL201506.00, P2REL201407.00, P3REL201101.00, and AHSREL201506.00.

AHS investigators ascertained both incident and fatal CHD events. We defined an incident CHD event and age at its occurrence with positive responses to the questions, “Has a doctor ever told you that you had (been diagnosed with) a myocardial infarction (heart attack)?” and “At what age were you first diagnosed?”. Additionally, we acquired information on fatal events by linking the study roster to state and national mortality registries and identified CHD events using International Classification of Diseases codes 410–414 for the 9th Revision and codes I20–I25 for the 10th Revision. Analyses excluded participants with a CHD event prior to enrollment. We present results for follow-up from enrollment to the earliest date of incidence or death, loss to follow-up or December 31, 2013. We omitted 1047 participants with pre-enrollment CHD and 7346 with missing or incomplete data and analyzed 81 263 participants who incurred 4396 CHD events in 1 425 976 person-years of observation. We conducted two supplemental analyses, one of incident CHD events for participants who completed at least one of the phase 2–4 questionnaires (69 208 participants and 2967 events) and another of death certificate identified CHD events (83 250 participants and 1922 CHD deaths). In addition, we assessed the potential impact of competing risks by analyzing data with participants censored at date of incidence for a smoking-related cancer (larynx, lung, oropharynx, bladder, liver, esophagus, kidney, and pancreas) if it occurred prior to the CHD event, where we identified cancers through state cancer registries. The censoring affected 2397 individuals who had a post-enrollment cancer or had moved out of state, eliminating 8093 person-years, and 179 individuals with a pre-enrollment cancer, eliminating an additional 2108 person-years. Allowing for missing data, there were 4282 CHD events and 1 415 775 person-years. Results for these supplemental analyses were similar (not shown).

The enrollment questionnaire obtained quantitative information for duration of smoking and categorical information on cigarettes/day (1–10, 11–20, 21–40, and >40) and smoking status (never [consumed < 100 total cigarettes], former or current). The phase 2 questionnaire provided information only on smoking status. Phase 3 and 4 questionnaires collected detailed smoking information, including smoking status, quantitative cigarettes/day and ages at starting and, for former smokers, stopping of smoking. Using data from phases 3 and/or 4, we imputed a quantitative cigarettes/day value to represent the phase 1 response. We randomly selected a value from the empirical distribution of continuous cigarettes/day within cigarettes/day category, conditional on cigarettes/day category at enrollment, state, race (white, non-white), occurrence of a pre-enrollment smoking-related cancer, age at enrollment (<55, 55–59, 60–64, 65–69, ≥70) and sex. For empirical distributions with <100 participants, we collapsed age and race categories. Other factors, for example, farm-related characteristics, enrollment year and non-farm employment, did not inform the imputation. We similarly imputed ages at start of smoking for phase 1—only former smokers—and used smoking durations to calculate years since smoking cessation.

Alpha-Tocopherol, Beta-Carotene Prevention Study

The Alpha-Tocopherol, Beta-Carotene Prevention Study (ATBC) was a double blind, placebo-controlled prevention trial. Between 1985 and 1988, investigators enrolled 29 133 male smokers aged 50–69 years from 14 areas in southwestern Finland who consumed 5 or more cigarettes/day and who did not have a prior cancer or serious illness that limited their ability to participate.14,15 The trial ended April 30, 1993. Investigators continued post-intervention follow-up by annual linkage to the Finnish Cancer Registry and the National Register of Causes of Death.16 Additional details are at http://atbcstudy.cancer.gov/.

Investigators administered questionnaires at baseline and at 4-month intervals during the active intervention period. Collection of covariate information ceased with the active intervention. We assumed that smoking characteristics at last contact remained unchanged during the post-intervention period.

Follow-up included time from randomization through December 31, 2012 or death, whichever occurred earlier. The analysis included 29 133 male smokers who incurred 5979 CHD deaths in 486 643 person-years of follow-up. As with the AHS, we conducted supplemental analyses that censored participants at the date of an incident smoking-related cancer. The censoring affected 2355 individuals with a smoking-related cancer prior to death. Allowing for April 30, 1993 as end of study date, data included 5801 CHD events and 138 787 person-years. Results were similar (not shown).

Data Structure

For each cohort, we used Poisson regression to estimate RRs with follow-up summarized in a multidimensional person-years table. For the AHS, the multiway contingency table included attained age (<50, 50–54,…, 75–79, ≥80), follow-up year (1993–1999, 2000–2004, 2005–2009, 2000–2014), pack-years (0, 1–9, 10–19,…, 60–69, ≥70), cigarettes/day (0, 1–4, 5–9,…, 35–39, 40–49, ≥50), years since last smoked (<2, 2–24, 25–34, ≥35), age at start of smoking (<15, 15–17, 18–19, 20–22, 23–24, ≥25 years), state, physician-diagnosed hypertension (yes/no) and diabetes (yes/no), regularly consumed alcohol (yes/no), and body mass index at enrollment (<25, 25–29, 30–34, ≥35, missing). For the ATBC, the person-years table included attained age (50–54,…, 75–79, ≥80), calendar year of follow-up (<1988, 1988–1989,…, 2002–2004), pack-years (<10, 10–11,…, 88–89, 90–94, 95–99, 100–109, 110–119, ≥120), cigarettes/day (<6, 6–7,…, 38–39, 40–44, 45–49, ≥50), years since last cigarette (0, 1–2, 3–4, ≥5 years), and age at start of smoking (<15, 15–17, 18–19, 20–22, 23–24, ≥25 years). For each cell, we accumulated person-time and CHD events and computed person-years weighted means for continuous variables. We accounted for the AHS imputations by creating M = 5 related person-years tables and combining replications.17

The ATBC Study enrolled only current smokers. We estimated male never-smoker CHD mortality rates based on age-specific death rates from Statistics Finland (available at http://pxnet2.stat.fi/PXWeb/pxweb/en/Eurostat/), which we included in the regression as a fixed offset.18,19 We estimated never-smoker rates by multiplying each age and year-specific rate by 1.0/(1-p[ever-smoked] + p[ever-smoked] × RRsmk), where RRsmk was the RR for CHD of ever smoked compared with never smoked. We set RRsmk equal to 2.0 and assumed that 0.70 of Finish males ever smoked.20,21

RR Modeling

We modeled disease rate with where z and α were vectors of adjustment variables and parameters, respectively. For categories of cigarettes/day (n) and pack-years (d), we used the standard exponential form for RRs, with never-smokers as the referent. For joint RRs, we found that RR trends with pack-years were approximately linear within each category of cigarettes/day. Our goal was to characterize the variations of the linear trends with cigarettes/day. For continuous pack-years, we initially fitted a linear model,

| (1) |

where β was the slope parameter, that is, the excess relative risk/pack-year (ERR/PKY). Since linearity occurred only within cigarettes/day categories, we extended equation 1 for S categories of cigarettes/day, s = 1,…,S:

| (2) |

where ds equaled d within category s and zero otherwise and β1,…, βS were slope parameters.

The slope measured the strength of the pack-years association for CHD relative to never-smokers within cigarette/day category, while variations of the slopes (β’s) reflected the impact of smoking intensity on the strength of association. We modeled variations of the slope as:

| (3) |

with β g(n) representing the slope at n cigarettes/day. We considered various forms for ln[g(.)], including cubic splines and parametric functions using combinations of n, n2, ln(n) and ln(n)2. We used the power relationship with since it fitted the data well for both cohorts. This function had the minimum Akaike Information Criterion (AIC)22 for the AHS, suggesting it was the preferred form, and was nearly the minimum for the ATBC, which occurred for (Supplementary Table S1).

We evaluated effect modification by extending equation 3 for categories of a variable, for example, years since smoking cessation. For categorical factor x with levels f = 1,…, F, we fitted

| (4) |

where replaced β d g(n). The difference in the deviances of equations 3 and 4 provided a likelihood ratio test of no effect modification.

For the AHS, adjustment variables (z) included state, sex, body mass index, regularly consumed alcohol, participant-reported hypertension, diabetes and calendar year of follow-up. Hypertension, diabetes, alcohol consumption, and body mass index reflected status at enrollment. In addition, we adjusted for age with six continuous variables, age, age squared and its natural logarithm for males and for females. For the ATBC, we adjusted for age and calendar year through the offset (Supplementary Material).

Analyses used the Epicure software package.23

Institutional review boards of participating institutions approved the AHS study and the ATBC Study.

Results

Marginal and Adjusted RRs for Cigarette Smoking Variables

For each cohort, the RRs for CHD increased with cigarettes/day and with pack-years, with RRs in the ATBC data somewhat larger (Table 1). Inclusion of a second smoking variable improved model fit (p < .01). After adjustment for the main effects of cigarettes/day, RRs by pack-years (reflecting 1–9 cigarettes/day as described in footnote c) continued to exhibit an increasing trend. After adjustment for pack-years, RRs decreased significantly with cigarettes/day, indicating a stronger pack-years association at lower cigarettes/day, although the pattern was non-monotonic for the ATBC data.

Table 1.

Numbers of Reported Incident Myocardial Infarctions and Fatal Coronary Heart Disease (CHD) Deaths for the Agricultural Health Study (AHS) and CHD Deaths for the Alpha-Tocopherol, Beta-Carotene (ATBC) Cancer Prevention Study, Person-Years (P-yrs) At Risk, Relative Risks (RRs) With 95% Confidence Intervals (CI) for Pack-Years of Cigarette Smoking and Cigarettes Smoked per day, Individually and Jointly

| Eventsa | P-yrs | RRb | 95% CI | RRb | 95% CI | RRb,c | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AHS cohort | ||||||||

| Never-smoker | 1941 | 885273.0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Pack-years of smoking | ||||||||

| 1–19 | 1009 | 311082.0 | 1.26 | (1.17,1.36) | 1.25 | (1.10,1.41) | ||

| 20–29 | 338 | 76202.8 | 1.59 | (1.41,1.79) | 1.61 | (1.34,1.94) | ||

| 30–39 | 303 | 55397.2 | 1.67 | (1.46,1.92) | 1.77 | (1.43,2.18) | ||

| 40–49 | 247 | 36000.6 | 1.98 | (1.71,2.30) | 2.18 | (1.79,2.64) | ||

| 50–59 | 154 | 20566.6 | 2.18 | (1.752.71) | 2.42 | (1.81,3.25) | ||

| ≥60 | 404 | 41453.8 | 2.26 | (1.96,2.60) | 2.75 | (2.22,3.41) | ||

| pd | <.01 | <.01 | ||||||

| Cigarettes/day | ||||||||

| 1–9 | 314 | 94722.4 | 1.24 | (1.10,1.42) | 1 | |||

| 10–19 | 455 | 128144.0 | 1.53 | (1.27,1.84) | 1.09 | (0.88,1.33) | ||

| 20–29 | 918 | 188401.0 | 1.55 | (1.37,1.76) | 0.95 | (0.81,1.11) | ||

| 30–39 | 302 | 54168.9 | 1.80 | (1.58,2.04) | 0.87 | (0.72,1.06) | ||

| ≥40 | 466 | 75266.9 | 1.80 | (1.59,2.04) | 0.78 | (0.63,0.97) | ||

| pd | <.01 | .02 | ||||||

| ATBC cohort | ||||||||

| Never-smoker | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Pack-years of smoking | ||||||||

| 1–19 | 568 | 65513.1 | 1.54 | (1.42,1.68) | 1.54 | (1.41,1.68) | ||

| 20–29 | 799 | 69219.1 | 2.01 | (1.87,2.15) | 1.99 | (1.78,2.23) | ||

| 30–39 | 991 | 91442.3 | 2.10 | (1.97,2.24) | 2.10 | (1.84,2.40) | ||

| 40–49 | 1143 | 99164.1 | 2.11 | (2.00,2.24) | 2.17 | (1.90,2.48) | ||

| 50–59 | 996 | 70317.6 | 2.34 | (2.20,2.49) | 2.46 | (2.14,2.83) | ||

| ≥60 | 1482 | 90987.0 | 2.63 | (2.50,2.77) | 2.85 | (2.46,3.31) | ||

| pd | <.01 | <.01 | ||||||

| Cigarettes/day | ||||||||

| 1–9 | 619 | 54339.7 | 1.67 | (1.54,1.81) | 1 | |||

| 10–19 | 2499 | 190647.0 | 2.14 | (2.06,2.22) | 1.02 | (0.91,1.15) | ||

| 20–29 | 2193 | 185687.0 | 2.28 | (2.18,2.37) | 0.93 | (0.81,1.06) | ||

| 30–39 | 488 | 42109.4 | 2.43 | (2.23,2.66) | 0.87 | (0.74,1.03) | ||

| ≥40 | 180 | 13860.1 | 2.87 | (2.48,3.32) | 1.01 | (0.82,1.24) | ||

| pd | .01 | .01 | ||||||

aNumbers for events reflect smoking status at cohort exit and for AHS categories at one imputation.

bFor the AHS cohort, RRs in relation to never-smokers adjusted for age, calendar year, sex, state, body mass index, physician diagnosed hypertension, diabetes and regular use of alcohol, with entries based on M = 5 imputations. For the ATBC cohort, RRs in relation to Finnish mortality rates adjusted to represent never-smokers.

cModel includes main effects for both pack-years and cigarettes/day, with the RR for 1–9 cigarettes/day set to one for identifiability.

d p value for test of no linear trend.

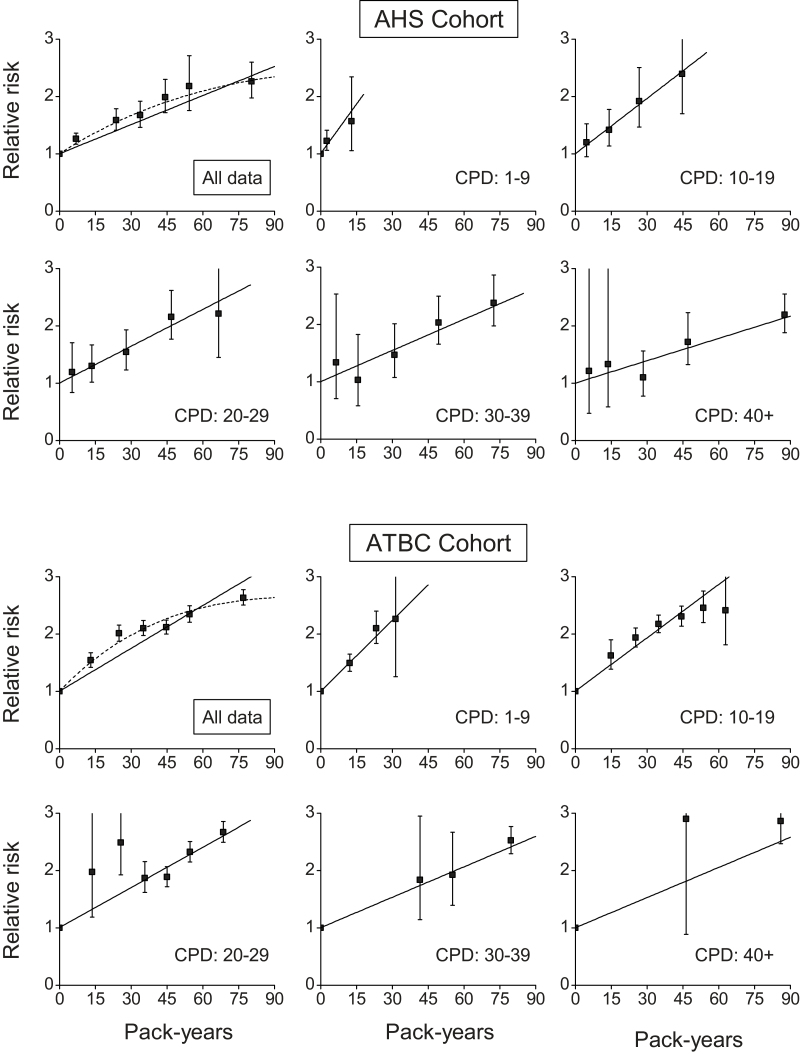

Joint RRs for Pack-Years and Cigarettes/Day

RRs increased with total pack-years in both cohorts, but with a significant departure from linearity (p < .01) (Figure 1, upper left panel, dash line). For the joint association, RRs by pack-years increased within each cigarettes/day category. Notably, within each cigarette/day category, the trend with increasing pack-years was consistent with linearity, except for the ATBC 10–19 cigarettes/day category (p < .01). However, using equation 3, which allowed a fuller account of variations with intensity, the test of no departure from linearity in pack-years was not rejected overall or within any of the cigarettes/day categories. For the respective cigarettes/day categories, estimates of ERR/PKY (β’s) were 0.058, 0.032, 0.021, 0.018, and 0.013 for the AHS and 0.041, 0.031, 0.023, 0.018, and 0.018 for the ATBC, showing a declining strength of association with increasing cigarettes/day (p < .01 for the test of γ = 0 in equation 3 for each cohort).

Figure 1.

Relative risks of coronary heart disease for categories of pack-years of cigarette smoking (solid symbol) relative to never-smokers for all data (upper left panels) and within categories of cigarettes/day (CPD) and fitted models, including: linear (solid line) and linear-exponential (dash line). Data are from the Agricultural Health Study (AHS), with the figure showing one imputation, and the Alpha-Tocopherol, Beta-Carotene Prevention Study (ATBC).

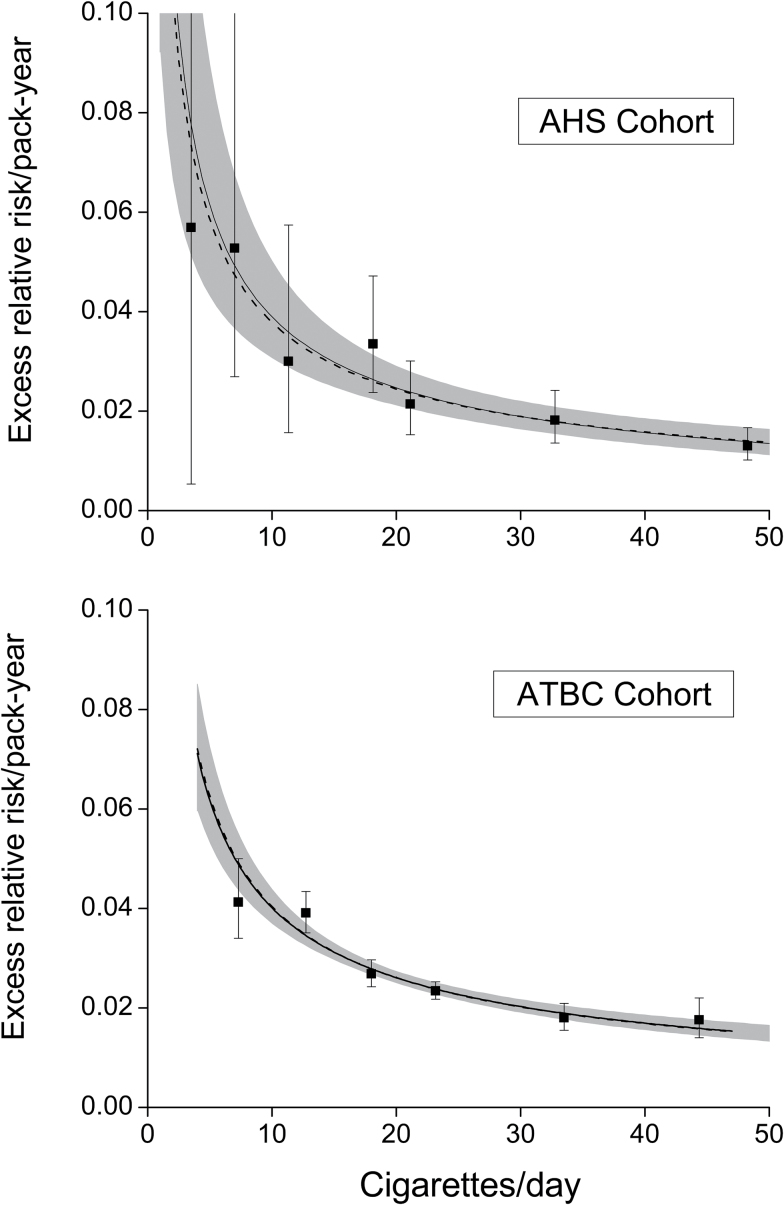

Allowing additional categories, we plotted each slope estimate by mean cigarettes/day and found deceasing strengths of association across the full range of cigarettes/day (Figure 2). The fitted equation 3 followed the patterns closely (solid line) (see Supplementary Table S2 for parameter estimates).

Figure 2.

Estimated excess relative risk/pack-year (ERR/PKY) for coronary heart disease within categories of cigarettes/day (solid symbol, with 95% confidence interval) and fitted models for pack-years and cigarettes/day for each cohort (solid line, with shaded area identifying the pointwise 95% confidence interval) and for a model using the inverse variance weighted parameters (dash line). Data are from the Agricultural Health Study (AHS), with the figure showing one imputation, and the Alpha-Tocopherol, Beta-Carotene Prevention Study (ATBC).

Although characteristics of the two cohorts differed, estimates of the two smoking intensity effects (γ) were consistent with homogeneity (p = .76). Equation 3 with γ fixed at the inverse variance weighted mean of the two study-specific γ estimates and with the two β’s estimated closely fitted the smoking data (Figure 2 dash line).

Effect Modification by Smoking-Related Factors

For the AHS, RRs with pack-years increased within level of each factor, although strengths of the association varied (Table 2). The fitted ERR/PKY at 20 cigarette/day declined with years since cessation of smoking (p < .01), and did not exhibit a well-defined variation with age started smoking (p = .15) (Table 2). For the ATBC, there was also a decreased strength of association with smoking cessation; however, since we had smoking cessation information only during active follow-up, we limited follow-up through 1993. For all ATBC data, age at start of smoking significantly modified the smoking risk, with enhanced risks for younger initiators. The Supplementary Material provides parameter estimates (Supplementary Table S2) and plots results (Supplementary Figures S1–S4).

Table 2.

Estimated Relative Risks (RRs) for a Reported Incident or Fatal Coronary Heart Disease Death (CHD) by Pack-Years With Never Cigarette Smokers as Referent and the Fitted Excess Relative Risk per Pack-Year (ERR/PKY) at 20 Cigarettes/day (CPD) Within Level of Smoking-Related Modifiersa

| Summary of fitted model | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimated RRs by pack-years | ERR/PKY @ 20 CPDb | ||||||||

| Modifier | Casesc | 1–9 | 10–19 | 20–39 | 40–59 | ≥60 | Estimate | 95% CI | p d |

| AHS cohort | |||||||||

| Age started smoking | |||||||||

| <15 | 282 | 1.24 | 1.28 | 1.29 | 2.19 | 2.28 | 0.023 | (0.015,0.036) | .15 |

| 15–17 | 761 | 1.14 | 1.13 | 1.39 | 1.78 | 2.14 | 0.017 | (0.011,0.026) | |

| 18–19 | 663 | 1.14 | 1.26 | 1.54 | 1.88 | 2.10 | 0.022 | (0.016,0.031) | |

| 20–22 | 378 | 1.24 | 1.53 | 1.67 | 2.24 | 2.39 | 0.028 | (0.021,0.037) | |

| ≥23 | 371 | 1.46 | 1.74 | 2.06 | 2.00 | 2.32 | 0.031 | (0.023,0.040) | |

| Smoking cessation (y) | |||||||||

| <2 | 875 | 1.73 | 2.09 | 2.42 | 2.59 | 2.66 | 0.031 | (0.027,0.037) | <.01 |

| 2–24 | 542 | 1.40 | 1.26 | 1.39 | 1.59 | 1.92 | 0.015 | (0.012,0.022) | |

| ≥25 | 1038 | 1.12 | 1.17 | 1.16 | 1.23 | 1.34 | 0.008 | (0.006,0.012) | |

| ATBC cohort | |||||||||

| Age started smoking | |||||||||

| <15 | 369 | 1.87 | 2.54 | 2.55 | 2.86 | 2.78 | 0.031 | (0.027,0.037) | .01 |

| 15–17 | 1611 | 1.71 | 2.16 | 2.27 | 2.35 | 2.83 | 0.029 | (0.026,0.030) | |

| 18–19 | 1297 | 1.36 | 2.03 | 2.04 | 2.33 | 2.51 | 0.024 | (0.022,0.027) | |

| 20–22 | 1757 | 1.51 | 2.07 | 2.05 | 2.27 | 2.53 | 0.025 | (0.023,0.028) | |

| ≥23 | 945 | 1.59 | 1.92 | 1.99 | 2.26 | 2.25 | 0.024 | (0.021,0.028) | |

| Smoking cessation (y)e | |||||||||

| <1 | 1556 | 1.48 | 1.93 | 1.81 | 1.85 | 2.22 | 0.021 | (0.019,0.023) | .03 |

| ≥1 | 135 | 0.89 | 1.55 | 1.53 | 1.36 | 2.03 | 0.012 | (0.007,0.021) | |

CI = confidence interval. Data from the AHS and the Alpha-Tocopherol, Beta-Carotene (ATBC) Cancer Prevention Study.

aAHS models adjusted for center, race, birth year, age, sex, education, alcohol consumption, high blood pressure, diabetes mellitus, total cholesterol, body mass index and use of cigars or pipe exclusively with entries based on M = 5 imputations. For AHS, categories reflected one imputation. RRs computed relative to never-smokers. For ATBC, CHD rates in never-smokers derived from the CHD mortality rate in Finnish males, assuming a 0.7 proportion of ever-smokers and a RR by ever smoked of 2.0.

bFor continuous pack-years (d) and cigarettes/day (n) with categorical modifying factor x with F levels, data fitted using: with ERR/PKY estimate at 20 cigarettes/day given as For overall data, the ERR/PKY at 20 cigarettes/day was 0.025 (0.021, 0.029) for AHS data based on parameter estimates β = 0.177 and γ = −0.659 and 0.026 (0.025, 0.027) for ATBC data based on parameter estimates β = 0.169 and γ = −0.624.

cCHD events in smokers only.

d p value for test of homogeneity of smoking effects across factor f, ie, β1 =…= βF and γ1 =…= γF.

eData restricted to the active follow-up period through 1994.

Discussion

Interpretation of the observed concave pattern of RRs for CHD by cigarettes/day, with the RR per cigarette/day decreasing with increasing cigarettes/day, is challenging.1–3 One reason is that cigarettes/day represents only exposure rate and not a quantitative measure of exposure to inhaled cigarette smoke. A single metric, cigarettes/day, smoking duration or pack-years, does not fully characterize smoking-related risks. Our analyses were consistent with earlier results from the ARIC Study12 and revealed inverse smoking rate patterns in two additional cohorts, whereby smoking fewer cigarettes/day for longer duration was more deleterious than smoking more cigarettes/day for shorter duration. For the AHS with β = 0.177 and γ = −0.659 in equation 3 (Supplementary Table S2), for 50 pack-years, the fitted RRs of CHD were if exposure accrued at 20 cigarettes/day and 1.7 if exposure accrued at 50 cigarettes/day. For the ATBC with β = 0.169 and γ = −0.624, the fitted RRs were 2.3 and 1.7.

Several reviews have suggested smoking-rate dependent pathophysiologic mechanisms for smoking-related CHD, and in particular the nonlinear RRs for cigarettes/day.1–8 Suggested possibilities have included nicotine stimulation resulting in enhanced oxygen demand and vasoconstriction, carbon monoxide induced hemodynamic effects, increased inflammation as a consequence of reduced anti-oxidants, particulates and other constituents of tobacco smoke, insulin sensitivity, and alterations in lipid profiles.1,7,8 For example, carbon monoxide, a combustion product of cigarette smoke, has an affinity for hemoglobin and exhibits smoking rate-dependent effects. Among current smokers, the ratio of serum carboxyhemoglobin (COHb) to cigarettes/day decreased with greater smoking intensity.24 Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, including benzo[a]pyrene, result from incomplete combustion of tobacco and other organics, and are associated with increased CHD risk.7,8 Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon exposure can activate the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) pathway and thereby induce a vascular inflammatory response, including the progression of atherosclerosis.7,8,25–27 Moreover, DNA adduct levels per unit polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon exposure were higher in environmentally exposed individuals than in workers exposed at occupational levels.28,29 Cigarette smoking intensity may also impact risk through nontobacco risk factors. For example, inflammation-related platelet aggregation dominates at low smoking intensities while other mechanisms (eg, increased fibrinogen and reduced high-density lipoprotein cholesterol) dominate at higher intensities.3

It is thought that cigarette smoking may have both long-term and short-term effects on CHD risk.7,8 Our approach provides an analytic method for assessing this distinction. The inverse smoking rate pattern, whereby smoking fewer cigarettes/day for longer duration results in an increased risk, suggests long-term effects may have an increased consequence.

Exposure misclassification may have influenced the inverse smoking rate pattern, whereby heavy smokers inhaled less vigorously following nicotine satiation, resulting in reduced potency, with the cigarettes/day metric increasingly overestimating internal exposure. Using cotinine as a biomarker of smoking rate, studies have shown that cotinine levels increased approximately linearly through about 15–20 cigarettes/day.24,30–39 However, associations at higher smoking rates have varied. Trends continued to increase in some studies,31,34,36,37,40,41 while in others they diminished,24,30–32,35,38 leveled or declined.30,31,33,38 As described previously,12 we conducted a sensitivity analysis that adjusted cigarettes/day based on a variety of possible associations with urinary cotinine. Since the reported cigarettes/day, and thus pack-years, may have reflected an overestimate of “true” exposure, the cotinine-adjusted estimates of ERR/PKY within smoking rate categories increased. Nevertheless, the adjustment had minimal impact on the overall shape of the inverse smoking rate effect, since correction for an overestimation of cigarettes/day lowered the “true” intensity but increased the ERR/PKY, leaving the overall pattern unchanged. More importantly, in our two cohorts the inverse smoking rate pattern occurred across the full range of cigarettes/day, which was incompatible with any presumed inhalation bias starting at 15–20 cigarettes/day.

For the ATBC analysis, we used a RR of 2.0 for ever-smokers in our adjustment of population rates of CHD in Finnish males to estimate rates in never-smokers.20,21 In a sensitivity analysis, we considered alternative adjustment values, RR = 1.6 and 1.8, which resulted in higher CHD rates for never-smokers and thus reduced RRs for pack-years and cigarettes/day compared to Table 1. However, the choice did not fundamentally alter the inverse exposure rate pattern exhibited in Figure 2, since patterns represented relationships among smokers.

While the AHS and ATBC cohorts were well-defined and represented large subgroups of their respective populations, Finnish male smokers and farmers and their spouses in mid-western and southeastern states in the United States, they were not representative samples of adults in either country. However, the inverse smoking rate pattern—smoking at a lower intensity for a longer duration is more deleterious than smoking at a higher intensity for a shorter duration—across the full range of intensities have been observed in these two very diverse cohorts and in the ARIC cohort which was conducted in four varied areas of the United States.12 The consistency of the results suggests that the effect may apply broadly.

We observed the inverse smoking intensity pattern across the full range of cigarettes/day; however, substantial uncertainties remain at the lowest intensities due to the limited range of pack-years, although we have now observed similar inverse associations with CHD in three independent datasets. Our analysis did not adjust for exposure to environmental tobacco smoke, in either never-smokers or smokers. This may have underestimated smoking risks, although we would anticipate that additional adjustment for environmental tobacco smoke exposure would have relatively minor impact on the overall smoking rate patterns.

In summary, current results confirm the previous observation in the ARIC data. While RRs for CHD increase with pack-years, the precise strength of association depends on the rate of exposure accrual. Across the full range of cigarettes/day, smoking fewer cigarettes/day for longer durations was more deleterious than smoking more cigarettes/day for shorter durations. The precise reasons for this inverse smoking intensity pattern still need elucidation.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Tables 1 and 2 and Figures S1–S4 can be found online at http://www.ntr.oxfordjournals.org

Funding

The Agricultural Health Study is supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, the National Cancer Institute, Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics (Z01CP010119) and by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (Z01ES049030). The Alpha-Tocopherol, Beta-Carotene Cancer Prevention Study is supported by the Intramural Research Program of the US National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, and by US Public Health Service contract HHSN261201500005C from the National Cancer Institute, Department of Health and Human Services. The authors maintained full control over the management, analysis and interpretation of the data; the preparation, review, and approval of the manuscript; and were independent of funders.

Declaration of Interests

None declared.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

DA and SJW are PIs for the ATBC study and LEBF, DPS and HC are PIs for the AHS and provide scientific and administrative leadership. All authors collaborated on analysis, interpretation of results and editing of the manuscript. JHL provided overall direction for analysis and manuscript preparation.

References

- 1. Benowitz NL. Cigarette smoking and cardiovascular disease: pathophysiology and implications for treatment. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2003;46(1):91–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Burns DM. Epidemiology of smoking-induced cardiovascular disease. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2003;46(1):11–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Law MR, Wald NJ. Environmental tobacco smoke and ischemic heart disease. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2003;46(1):31–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Csordas A, Bernhard D. The biology behind the atherothrombotic effects of cigarette smoke. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2013;10(4):219–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Pant R, Marok R, Klein LW. Pathophysiology of coronary vascular remodeling: relationship with traditional risk factors for coronary artery disease. Cardiol Rev. 2014;22(1):13–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ambrose JA, Barua RS. The pathophysiology of cigarette smoking and cardiovascular disease: an update. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43(10):1731–1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. How Tobacco Smoke Causes Disease: The Biology and Behavioral Basis for Smoking-Attributable Disease: A Report of the Surgeon General. Washington, DC: U. S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 8. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Smoking -- 50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Peto J. That the effects of smoking should be measured in pack-years: misconceptions 4. Br J Cancer. 2012;107(3):406–407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lubin JH, Caporaso NE. Misunderstandings in the misconception on the use of pack-years in analysis of smoking. Br J Cancer. 2013;108(5):1218–1220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Thomas DC. Invited commentary: is it time to retire the “pack-years” variable? Maybe not! Am J Epidemiol. 2014;179(3):299–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lubin JH, Couper D, Lutsey PL, Woodward M, Yatsuya H, Huxley RR. Risk of cardiovascular disease from cumulative cigarette use and the impact of smoking intensity. Epidemiology. 2016;27(3):395–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Alavanja MC, Sandler DP, McMaster SB, et al. The agricultural health study. Environ Health Perspect. 1996;104(4):362–369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. The Alpha-Tocopherol Beta-Carotene Cancer Prevention Study G. The effect of vitamin E and beta carotene on the incidence of lung cancer and other cancers in male smokers. New England J Med. 1994;330(15):1029–1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. The Alpha-Tocopherol Beta-Carotene Cancer Prevention Study G. The alpha-tocopherol, beta-carotene lung cancer prevention study: design, methods, participant characteristics, and compliance. Ann Epidemiol. 1994;4(1):1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Korhonen P, Malila N, Pukkala E, Teppo L, Albanes D, Virtamo J. The Finnish Cancer Registry as follow-up source of a large trial cohort–accuracy and delay. Acta Oncol. 2002;41(4):381–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rubin DB. Multiple Imputation for Nonresponse in Surveys. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Breslow NE, Day NE. Statistical Methods in Cancer Research Volume II - The Design and Analysis of Cohort Studies. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 1987. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Breslow NE, Lubin JH, Marek P, Langholz B. Multiplicative models and cohort analysis. J Amer Stat Assoc. 1983;78(381):1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mons U, Mueezzinler A, Gellert C, et al. Impact of smoking and smoking cessation on cardiovascular events and mortality among older adults: meta-analysis of individual participant data from prospective cohort studies of the CHANCES consortium. BMJ. 2015;350:h1551. doi:10.1136/bmj.h1551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Iversen B, Jacobsen BK, Løchen ML. Active and passive smoking and the risk of myocardial infarction in 24,968 men and women during 11 year of follow-up: the Tromsø Study. Eur J Epidemiol. 2013;28(8):659–667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Akaike H. A new look at the statistical model identification. IEEE Trans Automatic Control. 1974;19:716–723. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Preston DL, Lubin JH, Pierce DA, McConney ME. Epicure User’s Guide. Seattle, WA: HiroSoft International Corporation; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Law MR, Morris JK, Watt HC, Wald NJ. The dose-response relationship between cigarette consumption, biochemical markers and risk of lung cancer. Br J Cancer. 1997;75(11):1690–1693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wu D, Nishimura N, Kuo V, et al. Activation of aryl hydrocarbon receptor induces vascular inflammation and promotes atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E-/- mice. Arterioscler Thromb. 2011;31(6):1260–1261U1237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lewtas J. Air pollution combustion emissions: characterization of causative agents and mechanisms associated with cancer, reproductive, and cardiovascular effects. Mutat Res-Rev in Mutat Res. 2007;636(1–3):95–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Alshaarawy O, Zhu M, Ducatman A, Conway B, Andrew ME. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon biomarkers and serum markers of inflammation. A positive association that is more evident in men. Environ Res. 2013;126:98–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Phillips DH. Smoking-related DNA and protein adducts in human tissues. Carcinogenesis. 2002;23(12):1979–2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lewtas J, Walsh D, Williams R, Dobias L. Air pollution exposure DNA adduct dosimetry in humans and rodents: evidence for non-linearity at high doses. Mutat Res-Fundam Mol Mech Mutagen. 1997;378(1–2):51–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Joseph AM, Hecht SS, Murphy SE, et al. Relationships between cigarette consumption and biomarkers of tobacco toxin exposure. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14(12):2963–2968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Blackford AL, Yang G, Hernandez-Avila M, et al. Cotinine concentration in smokers from different countries: relationship with amount smoked and cigarette type. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15(10):1799–1804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Campuzano JC, Hernandez-Avila M, Jaakkola MS, et al. Determinants of salivary cotinine levels among current smokers in Mexico. Nicotine Tob Res. 2004;6(6):997–1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Etter JF, Perneger TV. Measurement of self reported active exposure to cigarette smoke. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2001;55(9):674–680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lewis SJ, Cherry NM, McL Niven R, Barber PV, Wilde K, Povey AC. Cotinine levels and self-reported smoking status in patients attending a bronchoscopy clinic. Biomarkers. 2003;8(3–4):218–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. O’Connor RJ, Giovino GA, Kozlowski LT, et al. Changes in nicotine intake and cigarette use over time in two nationally representative cross-sectional samples of smokers. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;164(8):750–759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Olivieri M, Poli A, Zuccaro P, et al. Tobacco smoke exposure and serum cotinine in a random sample of adults living in Verona, Italy. Arch Environ Health. 2002;57(4):355–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Richie JP, Jr, Carmella SG, Muscat JE, Scott DG, Akerkar SA, Hecht SS. Differences in the urinary metabolites of the tobacco-specific lung carcinogen 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone in black and white smokers. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1997;6(10):783–790. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lubin JH, Alavanja MC, Caporaso N, et al. Cigarette smoking and cancer risk: modeling total exposure and intensity. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;166(4):479–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Woodward M, Tunstall-Pedoe H, Smith WC, Tavendale R. Smoking characteristics and inhalation biochemistry in the Scottish population. J Clin Epidemiol. 1991;44(12):1405–1410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Xia Y, Bernert JT, Jain RB, Ashley DL, Pirkle JL. Tobacco-specific nitrosamine 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanol (NNAL) in smokers in the United States: NHANES 2007-2008. Biomarkers. 2011;16(2):112–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Nagano T, Shimizu M, Kiyotani K, et al. Biomonitoring of urinary cotinine concentrations associated with plasma levels of nicotine metabolites after daily cigarette smoking in a male Japanese population. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2010;7(7):2953–2964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.