Abstract

Objective

Examine unique forms of peer relations (i.e., peer group vs. friendships) in relation to patterns of youth’s resilience and challenge-related growth in the context of cancer.

Methods

In all, 279 youth (cancer, n = 156; control, n = 123) completed measures of posttraumatic stress, depression, anxiety, posttraumatic growth (PTG), and perceived positive changes. Youth also reported on their peer relations. Latent profile analysis (LPA) was used to examine patterns of youth’s adjustment. Peer relations were examined as predictors of youth’s adjustment.

Results

LPA revealed three profiles (42.1% resilient high growth, 21.4% resilient low growth, and 36.5% mild distress with growth). Youth’s peer relations, demographic factors, and disease-related factors predicted assignment to profiles. Differences in adjustment emerged depending on youth’s connection with their peers versus their friends.

Summary

Peer relations serve an important role in youth’s adjustment to stressful life events. Assessment of peer and friend support may provide a more nuanced understanding of adjustment processes.

Keywords: cancer and oncology, children, peers, posttraumatic stress, resilience, social support

Pediatric cancer 5-year survival rates have increased substantially over the past several decades to >80% currently (Howlader etal., 2013). Despite the increase in survival rates, the diagnosis and treatment of cancer are stressful and require an emotional and physical adjustment period. Variability exists in how youth adjust to potentially traumatic events, with the majority of youth following a stable trajectory of resilience (Bonanno, Westphal, & Mancini, 2011; Hong etal., 2014). Similar patterns also exist for youth diagnosed with cancer. Compared with healthy counterparts, youth reporting cancer as their most stressful life event are more likely to evidence a pattern of resilience (i.e., lower levels of distress) that also includes higher levels of challenge-related growth (i.e., positive changes resulting from the challenge-related event; citation withheld).

Psychosocial processes, particularly those involving family and parent–child relationships, have been highlighted as a mechanism to promote resilience and foster challenge-related growth (Hammen, Shih, & Brennan, 2004; Robinson, Gerhardt, Vannatta, & Noll, 2007; Varni, Katz, Colegrove, & Dolgin, 1993). Although studied less, other social systems such as peers may contribute to youth’s adjustment to cancer. Interpersonal relations within the peer context are critically important to youth’s general social and emotional development (Ladd & Price, 1987; Parker & Asher, 1987; Waldrip, Malcolm, & Jensen-Campbell, 2008). Missed days of school, weakened immune systems, illness owing to treatment, and being fatigued can certainly have an impact on youth’s interactions with their peers, including social status within the peer network. Thus, it is important to understand how peer social processes are associated with youth’s adjustment following a cancer diagnosis. Peer social processes are complex, and researchers have come to conceptualize various forms of them and the interplay of these different forms (Rubin, Bukowski, & Parker, 2006). For the present research, disentangling important developmental peer relationships (i.e., friendships) from the broader peer group may elucidate how forms of relations might differentially foster resilience and promote challenge-related growth in the context of cancer.

Much of the research on youth’s adjustment to cancer has focused on the role of the peer group. Being liked and being perceived as “popular” by the broader peer network has been shown to buffer the relation between stressful life events and psychopathology (Bukowski etal., 2009; Criss, Pettit, Bates, Dodge, & Lapp, 2002; Kim & Cicchetti, 2010). Further, youth identified their broader peer network as sources of support following a cancer diagnosis (Trask etal., 2003), which was highlighted as an indicator of positive adjustment immediately following the diagnosis of cancer (Varni etal., 1993). In short, peers play an important role in promoting resilience through previously established acceptance (i.e., popularity and liking) and by providing support following the diagnosis of cancer.

Unlike the role of evaluations within the peer group, friendships are characterized by shared affection, reciprocity, and intimacy (Rubin etal., 2006). Friends support the acquisition of (both positive and negative) social skills and social understanding including conflict resolution, self-identity, and understanding of the needs of others (e.g., for review, see Hartup & Stevens, 1997). Further, feeling connected to one’s friends plays an important role in reducing the association between stressful life events and maladjustment (Bolger, Patterson, Kupersmidt, 1998; Rubin etal., 2006). Limited research exists on understanding the role of friendships—specifically in promoting resilience—in the context of cancer. It is likely that, similar to healthy counterparts, high-quality friendships serve an important role in reducing distress for youth with cancer.

Support from the broader peer network and connectedness within friendship relationships may promote resilience by assuaging distress. Little research has examined the role of social support within the peer network, as it relates to challenge-related growth, and those studies have provided mixed results (Meyerson, Grant, Carter, & Kilmer, 2011). Inconsistency in the relation between challenge-related growth and supportive peer networks is perhaps owing, in part, to examining only the peer group and not also considering the role of friends.

The primary aim of the study was to assess processes of peer relations in terms of both the peer group and friendships, as they relate to patterns of youth’s resilience and challenge-related growth. Prior research with the same sample used in the present study examined baseline profiles of posttraumatic stress (PTS) and posttraumatic growth (PTG) (citation withheld), and found three profiles of adjustment with the majority of youth falling into a resilient profile. Specifically, 47% of youth were relatively unaffected by their stressful event, reporting low levels of both PTS and PTG. Approximately a third of the participants fell into a profile characterized by resilience (i.e., low levels of PTS) but higher levels of PTG. A small portion of the participants fell into a profile classified as distressed (i.e., high levels of PTS), but also reported high levels of PTG. As a secondary aim, the present research sought to examine similar profiles 1 year after baseline assessment and to expand the indicators of adjustment (i.e., depression, anxiety, perceptions of positive changes).

Importantly, because youth with cancer do not always perceive cancer as their most stressful life event (Phipps etal., 2014), the present research examined whether peer relations served similar roles for children with cancer who believed cancer was their most stressful experience and children with cancer who reported another event as their most stressful event. Further, owing to the nature of the cancer experience, including missed days of school and side effects of treatment, including changes in appearance, it is possible peer relations may be functionally different for youth with cancer in comparison with the normative experiences of healthy peers. As such, a healthy comparison group was also included. Finally, youth’s adjustment following a cancer diagnosis has been linked to demographic factors (Barakat, Alderfer, & Kazak, 2006; Currier, Hermes, & Phipps, 2009; Langeveld, Grootenhuis, Voute, De Haan, & Van Den Bos, 2004; Zebrack etal., 2012) and to medical factors (Currier etal., 2009; Zebrack etal., 2012), although this research has resulted in inconsistent findings. Given the potential, but uncertain, impact of these factors, they were included as covariates in the present research.

We hypothesized that similar profiles of resilience and challenge-related growth would emerge as they did in previous research (citation withheld). Consistent with the developmental literature (Bolger etal., 1998; Bukowski etal., 2009; Criss etal., 2002; Kim & Cicchetti, 2010), we posited that positive peer and friendship relations would be related to profiles characterized by lower levels of distress, that is, greater resilience. The link between challenge-related growth and peer and friendship relations is unclear (Meyerson etal., 2011); thus, this examination was exploratory in nature.

Methods

Procedures

Participants were patients recruited from outpatient clinics at a large children’s hospital as a part of a larger longitudinal study examining stress, adjustment, and growth in children and families with children who have been diagnosed with cancer. Participants were included if they were (a) a least 1 month from diagnosis, (b) able to speak and read English, (c) did not have any significant cognitive or sensory deficit, and (d) a parent/legal guardian was willing to participate and provide assent for their child. Patient participants were recruited in one of four strata derived from elapsed time since their cancer diagnosis (1–6 months; 6–24 months; 2–5 years; > 5 years). At baseline (Time 1), 378 children with cancer were approached regarding participation in the study, and 258 (68%) agreed to participate. Three participants failed to provide useable data and were removed from analyses, resulting in 255 participants at baseline. Participants and nonparticipants at Time 1 did not differ statistically by age, gender, race/ethnicity, diagnostic category, or categorized time since diagnosis.

Control group participants (a) did not have a history of chronic or life-threatening illness, (b) were able to speak and read English, (c) did not have any significant cognitive or sensory deficits, and (d) both parent and child were willing to participate and provide consent/assent. Children were recruited in a two-part process from public elementary, middle, and high schools from a three-state area surrounding the hospital. In the first step, permission slips were distributed through the schools, and returned permission slips included information on child age, gender, race/ethnicity, and parental education and occupation. The returned data were used to create a pool of potential control participants, who were subsequently contacted based on demographic match, using a frequency matching approach designed to obtain samples that are comparable on specific demographic variables. The demographic matching variables included age, race, gender, and socioeconomic status (SES). The majority (86%) of potential control participants that were contacted based on demographic match agreed to participate and completed measures.

Data for the present research were derived from the second time point only for a secondary analysis of the data. The second time point (Time 2) occurred approximately 1 year following the collection of Time 1 data. Approximately 63% (n = 279) of participants who completed data at Time 1 completed data at Time 2 and were included for analyses. Those participants who did not provide data at Time 2 missed the cut-point (i.e., beyond 1 year from the baseline visit) for completing data at Time 2 (61%), declined to participate a second time (24%), or had not yet reached the 1-year time point for data collection (15%). Participants who completed measures at Time 2 did not differ statistically on age (t (440) = −0.73), gender (χ2 (1,442) = 0.47), race (χ2 (5,442) = 2.10), diagnostic category (χ2 (4,442) =0 .89), or SES strata (χ2 (4,442) = 3.812) than those who did not complete Time 2 data.

Participants in the study met with trained psychology staff at the hospital’s outpatient psychology clinic. Each participant came with one parent, who also participated as a part of the larger study. At Time 2, youth participants were administered measures to assess PTS, anxiety, depression, PTG, and perceived positive change. Measures were also collected to assess youth’s friendship and peer-related functioning.

Participants

Participants included 279 youth (cancer group, n = 156; control group, n = 123) and a primary caregiver for each. Demographic and medical information are presented in Table I.

Table I.

Descriptive Statistics for Study Data at Second Time Point

| Variable | Patient group, n = 156 | Control group, n = 123 |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| % Female | 49.4 | 53.7 |

| % Male | 50.6 | 46.3 |

| Age | ||

| Mean (SD) | 13.96 (2.97) | 13.13 (3.06) |

| Range | 8–19 | 8–19 |

| Race | ||

| % White | 71.8 | 74.0 |

| % Black | 23.7 | 22.0 |

| % Other | 4.5 | 4.0 |

| Parent child reporting on | ||

| % Mom | 85.3 | 89.4 |

| % Dad | 9.6 | 10.6 |

| % Other | 5.1 | 0.0 |

| Diagnosis | ||

| % Acute lymphoblastic leukemia | 22.4 | – |

| % Other leukemia | 7.7 | – |

| % Hodgkin’s & non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma | 12.8 | – |

| % Solid tumor | 39.8 | – |

| % Brain tumor | 17.3 | – |

| % Healthy comparison | – | 100.0 |

| Treatment intensity | ||

| Mean (SD) | 2.76 (0.50) | – |

| Range | 1–4 | – |

| Years since diagnosis | ||

| Mean (SD) | 5.38 (4.69) | – |

| On therapy | ||

| % Yes | 52.4% | – |

| Relapse | ||

| %Yes | 6.2% | – |

Participants with a history of cancer did not differ from healthy controls on gender (χ2 (1, N = 279) = 0.25, p = .62) or ethnicity (χ2 (2, N = 279) = 0.17, p = .92). However, youth with cancer were slightly older (M =13.96, SD = 2.97) than healthy comparisons (M =13.13, SD = 3.06, F(1, 278) = 5.25, p =.02). Healthy comparisons evidenced slightly higher SES scores (M =47.73, SD = 9.59), as assessed by the Barratt Simplified Measure of Social Status (Barratt, 2006), than youth with cancer (M =42.85, SD = 13.12, F(1, 278) = 11.99, p =.001). Given the demographic discrepancies, these variables were examined as covariates in the present research.

Measures

Youth PTS

The UCLA PTSD Reaction Index for DSM-IV (Pynoos, Rodriguez, Steinberg, Stuber, & Frederick, 1998) is a 22-item measure that was used to assess DSM-IV Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) criteria in youth. The items are grouped into the PTSD criterion clusters: Re-experiencing/Intrusion (criteria B), Avoidance/Numbing (criteria C), and Arousal (criteria D). An overall score above 38 on this measure has been used as an indication of clinically significant PTS (Steinberg, Brymer, Decker, & Pynoos, 2004). Youth responded to questions based on their self-identified most stressful life event. Just over half of youth with cancer (56%) reported a cancer-related event as their most stressful event, and the remainder of youth with cancer (44%) reported a non-cancer-related event (e.g., unexpected loss of a loved one, being homeless, displacement following natural disaster, car accidents, and domestic violence). These events were similar for the healthy comparison group. The measure has excellent psychometric properties including high internal and test–retest reliability (Steinberg etal., 2004). Only the overall score was used in the present study and exhibited adequate internal reliability (α = .91).

Youth PTG

The Benefit Finding/Burden Scale for Children (Phipps, Long, & Ogden, 2007) is a 20-item measure assessing youth’s perceptions of positive and negative growth as a result of a traumatic experience. Two subscales are derived from this measure: benefit (“Has helped me become a stronger person.”) and burden (“I am not able to enjoy myself the way I used to.”). Youth were asked to respond on a 5-point scale from “Not at all” to “Very Much” the degree to which they have experienced change as a result of their cancer experience. The Benefit Finding subscale, which assesses a child’s perception of personal growth as a result of a self-identified significant life event (i.e., the same event identified in the UCLA) was used for the current study and evidenced adequate internal consistency (benefit α = .90).

Youth Perceived Positive Change

The Perception of Changes in Self Scale (Barakat etal., 2006) was used as an additional measure of PTG. Youth were asked whether changes have occurred as a result of their self-identified most stressful life event across nine domains (e.g., “The way I treat other people,” “How I make friends,” and “How I think about life”), and if so, whether the change was for the better or worse. The score reflects the total number of positive changes. Internal reliability was acceptable, α = .78.

Youth Anxiety and Depression

The Behavioral Assessment System for Children, Second Edition (BASC-2;Reynolds & Kamphaus, 2004) is a widely used broad-band behavior rating schedule for youth. Youth’s self-reported scales for anxiety and depression were used as additional measures of adjustment. The BASC-2 has evidenced adequate psychometric properties across self, parent, and teacher reports including reliability (α’s ranging around .80), convergent validity, and discriminative validity (Reynolds & Kamphaus, 2004).

Friend and Peer Functioning

To assess peer and friend connectedness, the Hemingway Measure of Adolescent Connectedness (HMAC) was used. The HMAC (Karcher, 2009, 2010) is a 57-item youth-reported scale that measures positive connections to youth’s social environment. The measure consists of 10 subscales assessing five broader domains of connectedness: (1) school (school and teacher); (2) family (parents and siblings); (3) peers (friends and peers); (4) neighborhood; and (5) self (present self, future self, reading). For the present study, the friends (e.g., “I have friends I’m really close to and trust completely.”) and peers (e.g., “I get along well with other students in my class.”) subscale scores were used. Although the HMAC was created and validated with adolescents (Karcher, 2005; Karcher & Sass, 2010), it has also been used with children as young as 9 years old with adequate reliability (Karcher, 2008; Karcher, Davidson, Rhodes, & Herrera, 2010). Cronbach’s α’s for the Friends subscale was .79 and for the Peers subscale .76.

Demographic Information

Age, gender, race, and sex were collected through medical chart reviews and confirmed with primary caregivers. For the patient group, medical diagnosis, relapse, time since diagnosis and whether the patient was on treatment were ascertained from medical chart reviews. The Intensity of Treatment Rating Scale 2.0 (ITR-2; Werba, Hobbie, Kazak, Ittenbach, Reilly, & Meadows, 2007) was used to provide an overall rating of treatment intensity. The ITR-2 uses information regarding diagnosis, stage or risk level, and treatment modality to produce an overall rating with four levels, ranging from least intensive to most intensive treatments, with interrater reliability reported at .87. Socioeconomic status was measured using the Barratt simplified measure of social status (Barratt, 2006).

Analyses

Latent profile analyses (LPAs) were conducted using Mplus 7.3 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998-2012) to identify empirically derived profiles of youth’s adjustment to their most stressful experience (for review see Berlin, Parra, & Williams, 2014; Berlin, Williams, & Parra, 2014). Indicators of the latent profile included PTS, depression, anxiety, PTG, and perceived positive change. Several indices were used to determine the optimal fit of the data: Bayesian information criterion (BIC; Schwarz, 1978), with lower values indicating better fit; entropy values, with values closer to 1 indicating that individuals were classified with higher accuracy (Berlin, Williams, & Parra 2014); sample size of the classes within each profile; and interpretability of the classes. The Lo–Mendell–Rubin test (LMR; Lo, Mendell, & Rubin, 2001) and the Bootstrap Likelihood Ratio Test (McLachlan & Peel, 2000) were used to assess improvement in model fit.

The model was specified with uncorrelated indicators, and the variances were freely estimated across classes. To determine whether the profiles were related to children’s demographic factors, self-report of peer relations, and teacher report of peer relations, the three-step approach was used to compare identified classes on these variables (Asparouhov & Muthén, 2013) in addition to chi-square analyses with exported BCH weights. Also, interactions between peer relations and group status (i.e., healthy control vs. patient participant) and interactions between peer relations and event type (i.e., cancer participant reporting cancer, cancer participant reporting non-cancer event, and healthy control) were computed and examined to see if these interactions predicted youth’s adjustment. None of the interactions emerged as statistically significant, and thus, interactions were removed from the final analyses.

Results

Overall, a three-class LPA model provided the most interpretable and adequate fit to the data (see Table II). Although a six-class solution provided the best fit in terms BIC values, the sample sizes of some of the classes (∼5%; see Table II) were too small and the LMR value was nonsignificant. Given that the LMR value tends to overestimate the number of classes, Nylund, Asparouhov, & Muthén (2007) recommended not increasing class size once the LRM value becomes nonsignificant. A four-class model and the addition of a new class (i.e., five-class, six-class, etc.) provided a nonsignificant LMR value. Though a four-class model provided a nearly significant LMR, in an effort to be conservative with the actual number of classes existing, only the two and three class models were furthered analyzed. According to the LMR values in the present study, a two- or three-class model provided the best fit to the data, and meaningful class sizes. Because the three-class model provided a lower BIC value and a higher entropy value than the two-class model, the three-class model was selected as the best fitting model.

Table II.

Comparison of Model Fit for Latent Profile Analyses

| N-classes | Akaike information | Bayesian information criterion | Entropy | Lo–Mendell–Rubin | Bootstrap likelihood ratio test | N-class size range |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 3,440.64 | 3,516.89 | 0.83 | p < .001 | p < .001 | 109–170 |

| 3 | 3,237.84 | 3,392.04 | 0.87 | p = .004 | p < .001 | 60–118 |

| 4 | 3,199.34 | 3,355.57 | 0.87 | p = .05 | p < .001 | 31–114 |

| 5 | 3,149.24 | 3,345.32 | 0.88 | p = .12 | p < .001 | 14–103 |

| 6 | 3,108.84 | 3,344.87 | 0.86 | p = .40 | p < .001 | 13–89 |

| 7 | 3,086.44 | 3,353.41 | 0.86 | p = .24 | p < .001 | 13–74 |

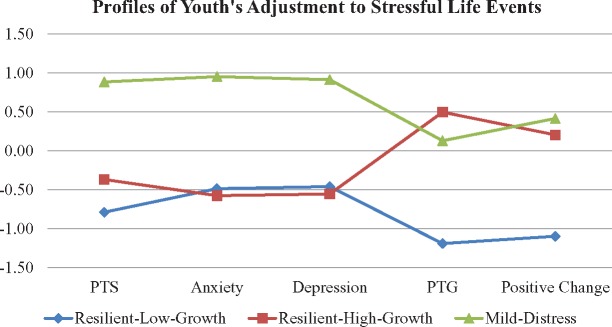

The majority of the youth (63.5%) in this study fell into two resilient profiles, with 21.4% of the sample falling into a “resilient-low-growth” (RLG) profile, and 42.1% falling into a “resilient-high-growth” (RHG) profile; while 36.5% of youth fell into a “mild-distress-with-growth” profile (MDG; see Figure 1). Means and standard deviations for the indicators of the profiles are presented in Table III.

Figure 1.

Latent profiles of children’s standardized PTS, anxiety, depression, PTG, and positive change scores. Note. PTS = posttraumatic stress; PTG = posttraumatic growth; PSC = perceived positive changes.

Table III.

Means and Standard Deviations for the Model Indicators Across Profiles

| Resilient low growth |

Resilient high growth |

Mild distress growth |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD |

| PTS | 7.05 | 5.40 | 13.60 | 7.53 | 32.62 | 15.44 |

| Anxiety | 42.84 | 7.46 | 42.03 | 5.70 | 58.97 | 8.93 |

| Depression | 43.16 | 5.15 | 42.00 | 3.48 | 57.99 | 11.69 |

| PTG | 15.85 | 4.36 | 33.97 | 8.81 | 30.23 | 8.61 |

| PSC | 0.68 | 0.65 | 4.16 | 2.40 | 4.78 | 2.48 |

Note. PTS = posttraumatic stress; PTG = posttraumatic growth; PSC = perceived positive changes.

Predictors of Child Adjustment Profiles

Demographic Predictors of Classes

Race, age, sex, and SES differentiated the profile to which youth were more likely to be assigned (see Table IV). Being Black (compared with being White or “Other” ethnicity) increased youth’s odds of falling into the RHG profile than the RLG profile by 4.37 (p = .02). Regarding age, a one-unit increase in age increased youth’s odds of falling into the RHG compared with RLG by 1.14 (p = .04) and the MDG profile compared with the RLG profile by 1.15 (p = .02). Being female increased youth’s odds of falling into the MDG profile compared with the RLG profile by 1.73 (p = .01). Finally, a one-unit increase in SES increased odds of falling into the RHG compared with the MDG profile by a factor of 1.02 (p = .03).

Table IV.

Parameter and Predictor Estimates

| Parameter | Estimate | S.E. | Est./S.E. | Two-Tailed p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameterization using reference class resilient low growth | ||||||

| Resilient high growth | ||||||

| Demographics | ||||||

| Healthy controls vs. patients | −0.466 | 0.200 | −2.333 | .020 | ||

| Sex (male vs. female) | −0.342 | 0.194 | −1.760 | .078 | ||

| Black vs. White and other | 1.475 | 0.639 | 2.310 | .021 | ||

| White vs. Black and other | 0.786 | 0.591 | 1.330 | .184 | ||

| Other vs. Black and white | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1.000 | ||

| Age | 0.128 | 0.061 | 2.09 | .037 | ||

| SES | 0.024 | 0.016 | 1.488 | .137 | ||

| Self-report peer functioning | ||||||

| HMAC–friend connectedness | 1.252 | 0.569 | 2.200 | .028 | ||

| HMAC–peer connectedness | −1.054 | 0.744 | −1.417 | .156 | ||

| Parameterization using reference class resilient low growth | ||||||

| Mild distress group | ||||||

| Demographics | ||||||

| Healthy controls vs. patients | −0.089 | 0.194 | −0.458 | .647 | ||

| Sex (male vs. female) | −0.546 | 0.190 | −2.880 | .004 | ||

| Black vs. White and other | 0.536 | 0.491 | 1.092 | .275 | ||

| White vs. Black and other | −0.089 | 0.427 | −0.209 | .834 | ||

| Other vs. Black and White | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1.000 | ||

| Age | 0.146 | 0.064 | 2.294 | .022 | ||

| SES | −0.006 | 0.016 | −0.396 | .692 | ||

| Self-report peer functioning | ||||||

| HMAC–friend connectedness | 0.772 | 0.645 | 1.197 | .231 | ||

| HMAC–peer connectedness | −1.993 | 0.756 | −2.636 | .008 | ||

| Parameterization using reference class resilient high growth | ||||||

| Mild distress | ||||||

| Demographics | ||||||

| Healthy controls vs. patients | 0.377 | 0.171 | 2.206 | .027 | ||

| Sex (male vs. female) | −0.204 | 0.160 | −1.273 | .203 | ||

| Black vs. White and other | −0.940 | 0.582 | −1.615 | .106 | ||

| White vs. Black and other | −0.875 | 0.560 | −1.561 | .119 | ||

| Other vs. Black and White | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1.000 | ||

| Age | 0.018 | 0.054 | 0.337 | .736 | ||

| SES | −0.031 | 0.014 | −2.217 | .027 | ||

| Self-report peer functioning | ||||||

| HMAC–friend connectedness | −0.480 | 0.369 | −1.303 | .193 | ||

| HMAC–peer connectedness | −0.939 | 0.354 | −2.653 | .008 | ||

Note. PTS = posttraumatic stress; PTG = posttraumatic growth; HMAC= Hemmingway Measure of Adolescent Connectedness; BASC = Behavioral Assessment for Children; SRP = Self-Report of Personality.

Event Type

Significant differences emerged between type of event (e.g., youth with cancer reporting cancer as their most stressful event, youth with cancer reporting another event as their most stressful event, and healthy comparisons) and the profiles youth were assigned to (χ2 (4, N = 279) = 17.76, p < .001). Specifically, the majority of youth with cancer reporting cancer as their most stressful event (56%) fell into the RHG profile (RLG, 8%; MDG, 36%). Youth with cancer reporting a non-cancer event (RLG, 30%; RHG, 39%; MDG, 31%) and healthy comparisons (RLG, 27%; RHG, 34%; MDG, 39%) were evenly distributed across all profiles.

Self-Reported Peer Relations

A one-unit increase in youth’s self-report of friend connectedness increased odds of falling into the RHG profile compared with the RLG profile by 3.50 (p = .03). However, friend connectedness did not distinguish between youth in the RHG profile and the MDG profile nor the MDG profile and the RLG profile (see Table IV).

Regarding peer connectedness, the RLG and RHG profiles did not differ. However, a one-unit increase in reports of peer connectedness increased the odds of being assigned to one of the two resilient profiles compared with the MDG profile (RLG vs. MDG, odds = 7.33, p = .01; RHG vs. MDG, odds = 2.55, p = .01; Table IV).

Discussion

Stressful life events such as the diagnosis of cancer present a serious adjustment challenge for youth. Youth experience a wide range of emotional responses, some of which are considered negative (e.g., depression, anxiety, PTS) and some positive (e.g., perceptions of positive changes, PTG). Overall, the majority of youth in this study (63.5%) fell into a resilient profile characterized by low levels of distress (21.4% in the RLG profile; 42.1% in the RHG profile; 36.5% in the MDG profile). These findings were consistent with patterns of PTS and PTG examined at baseline within this population (citation withheld), perhaps indicating the stability of resilience over time following a stressful life event. Further, youth who believe their cancer is the most stressful event were no more likely to experience distress than youth who encounter other stressful life events. It appears that what is unique about the cancer journey is the increased likelihood of experiencing challenge-related growth.

Equally important to understanding how youth adjust to stressful life events, such as the diagnosis of cancer, is understanding factors that predict how youth will adjust. Perhaps the most interesting finding of the present research was the different effects of friend connectedness versus peer connectedness. As noted in the Introduction, friendships are characterized by shared affection, reciprocity, and intimacy. For the broader peer group, which subsumes a variety of dyadic relationships that are not necessarily voluntary, reciprocal, or emotionally intimate (Rubin etal., 2006), connectedness concerns issues of group standing and likeability.

The findings of the present research indicate that youth with higher perceptions of friend connectedness were more likely to fall into a profile categorized by perceptions of positive changes and growth (i.e., RHG) than a profile characterized by low challenge-related growth (i.e., RLG). Higher perceptions of peer connectedness increased the odds of youth assigned to profiles characterized by low distress. Thus, feeling supported by the broader peer network may be enough to reduce distress following a stressful life event. However, friendships provide validation and set the stage for stronger beliefs of self-concept (Bukowski etal., 2009). Perhaps connectedness within friendships bolsters positive growth by providing the space to share and cognitively process events on a more intimate level by those who are more likely to know the personal details of their distress. Through this mechanism, there are also more opportunities for perceptions of feeling validated.

The role of friend connectedness versus peer connectedness also highlights that although friendships and peer group relations are related, these social contexts also offer unique contributions to children’s social adjustment (Hinde, 1992). To continue our understanding of psychosocial processes that result in reduced distress and positive changes following a stressful life event, it will be important for future research to distinguish between the peer group, friendships, and patterns of interactions among youth and their peers.

Youth were more likely to be assigned to the RHG profile if they believed cancer to be their most stressful event. In fact, high levels of perceived growth were characteristic of youth referencing a cancer event, as only 8% fell into the RLG class. This is consistent with prior research reporting higher levels of perceived benefit in children with cancer (Phipps etal., 2014), and may be a distinctive feature of the cancer experience owing to the unique social support children and families receive following a pediatric cancer diagnosis or to the multiple opportunities children have to experience mastery of challenging, but manageable, daily stressors. There was a lack of significant interactions between group status (cancer vs. healthy comparison) and peer functioning as well as type of event (cancer vs. non-cancer event) and peer functioning in predicting profile membership. These findings indicate that, to some extent, peer relations were equally important in predicting emotional responses regardless of whether youth experienced cancer.

Demographic factors such as race, age, sex, and SES were associated with youth’s adjustment to stressful life events. Race was distinguished between profiles, with Black youth more likely to be assigned to profiles described by higher levels of positive growth. This is consistent with Zebrack and colleagues’ (2012) findings that non-White youth were more likely to experience positive growth related to their cancer experience. Little research exists within the child and adult literature explaining why Black youth are more likely to experience adjustment characterized with some level of PTG. Some have posited religious coping, which is more prominent in Black communities (Bean, Perry, & Bedell, 2002) and related to PTG (Linley & Joseph, 2004) to be a factor. Others have suggested the cultural context of hardship and experience of racism might explain greater levels of PTG (Pole, Gone, & Kulkarni, 2008) within these communities. Certainly, these questions should be addressed both within the larger PTG research area as well within oncology populations. Age increased the odds of youth being assigned to a profile described by positive growth and in some cases higher distress. Positive growth or positive change requires one to have established schemas around factors that are important and meaningful for them to change following a stressful life event. These preexisting schemas (Tedeschi & Calhoun, 2004) are less likely to be established in younger children. Finally, sex also was associated with youth’s adjustment. Females were more likely to fall into the MDG profile compared with the other profiles. This seems to be consistent with the broader developmental literature indicating females report more distress following a stressful life event (Langeveld etal., 2004).

Limitations and Future Research

It is important to consider the present findings in light of a few limitations to the present research and areas for future research. First, we were unable to obtain peer reports of youth functioning within the peer group. Although self-reported peer relations added uniquely to our understanding of youth’s functioning, peers would provide a valuable perspective (see Fabes, Martin, & Hanish, 2011). Also, the correlational design precludes establishing causal links between peer relations and adjustment. Other methodologies would help disentangle the temporal sequencing of factors and promote generalization of findings. Despite the continuity between the standardized means across anxiety, depression, and PTS, the anxiety and depression questionnaires were not event specific. As such, it is difficult to determine definitively that these responses were related to the identified event. Finally, the construct and definition of resilience is complex. Consistent with previous research (Bonanno & Mancini, 2012; Hilliard, McQuaid, Nabors, & Hood, 2015), we have conceptualized resilience in terms of low levels of distress following a stressful life event, that is, as an outcome. However, we recognize that others have different perspectives, and resilience may be defined in a number of ways, including as a trait or a process (Rosenberg & Yi-Frazier, 2016; Southwick, Bonanno, Masten, Panter-Brick, & Yehuda, 2014). The current findings suggest the ability to acquire and maintain positive peer relations and friendships during stressful journeys is a marker of resilience and should be examined in future research.

In short, a stressful life event, in particular the diagnosis of cancer, can engender a variety of emotional experiences, both negative and positive. The majority of youth appear to be resilient or experiencing low levels of distress. Even those youth experiencing distress perceived positive changes as a result of their stressful life event. Disentangling peer-group connectedness from friendship relationship connectedness provided a more nuanced understanding of adjustment to cancer and other stressful events. Peer relations seem to predict how youth adjust, with those experiencing greater connectedness to peers evidencing adjustment characterized by patterns of resilience, and those reporting more connection with their friends demonstrating a pattern of resilience and also challenge-related growth.

Funding

NIH RO1 CA136782, and the American Lebanese-Syrian Associated Charities (ALSAC).

References

- Asparouhov T., Muthén B. O. (2013). Auxiliary variables in mixture modeling: A 3-step approach using Mplus [Online web notes]. Retrieved from http://statmodel.com/examples/webnotes AuxMixture_submitted_corrected_webnote.pdf.

- Barakat L. P., Alderfer M. A., Kazak A. E. (2006). Posttraumatic growth in adolescent survivors of cancer and their mothers and fathers. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 31, 413–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barratt W. (2006). The Barratt Simplified Measure of Social Status (BSMSS) measuring SES. Unpublished manuscript. Indiana State University. Retrieved from http://wbarratt.indstate.edu/socialclass/Barratt_Simplified_Measure_of_Social_Status.pdf

- Bean R., Perry B., Bedell T. (2002). Developing culturally competent marriage and family therapists: Treatment guidelines for non-African American therapists working with African American families. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 28, 153–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berlin K. S., Parra G. R., Williams N. A. (2014). An introduction to latent variable mixture modeling (part 2): Longitudinal latent class growth analysis and growth mixture models. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 39, 188–203. doi:10.1093/jpepsy/jst085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berlin K. S., Williams N. A., Parra G. R. (2014). An introduction to latent variable mixture modeling (part 1): Overview and cross-sectional latent class and latent profile analyses. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 39, 174–187. doi:10.1093/jpepsy/jst084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger K. E., Patterson C. J., Kupersmidt J. B. (1998). Peer relationships and self‐esteem among children who have been maltreated. Child Development, 69, 1171–1197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno G. A., Mancini A. D. (2012). Beyond resilience and PTSD: Mapping the heterogeneity of responses to potential trauma. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 4, 74. [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno G. A., Westphal M., Mancini A. D. (2011). Resilience to loss and potential trauma. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 7, 511–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bukowski W. M., Motzoi C., Meyer F. (2009). Friendship as process, function, and outcome. Handbook of peer interactions, relationships, and groups, 217–231. New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Criss M. M., Pettit G. S., Bates J. E., Dodge K. A., Lapp A. L. (2002). Family adversity, positive peer relationships, and children’s externalizing behavior: A longitudinal perspective on risk and resilience. Child Development, 73, 1220–1237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Currier J. M., Hermes S., Phipps S. (2009). Brief report: Children's response to serious illness: Perceptions of benefit and burden in a pediatric cancer population. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 34, 1129–1134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabes R. A., Martin C. L., Hanish L. D. (2011). Children's behaviors and interactions with peers In Rubin K. H., Bukowski W. M. (Eds.), Handbook of peer interactions, relationships, and groups. New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C., Shih J. H., Brennan P. A. (2004). Intergenerational transmission of depression: Test of an interpersonal stress model in a community sample. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 72, 511.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartup W. W., Stevens N. (1997). Friendships and adaptation in the life course. Psychological Bulletin, 121, 355–370. [Google Scholar]

- Hilliard M. E., McQuaid E. L., Nabors L., Hood K. K. (2015). Resilience in youth and families living with pediatric health and developmental conditions: Introduction to the special issue on resilience. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 40, 835–839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinde R. A. (1992). Human social development: An ethological relationship perspective In H. Mc Gurk (Ed.), Childhood social development: Contemporary perspectives (pp. 13–30). Hove UK: Lawrence Erlbaum Association. [Google Scholar]

- Hong S. B., Youssef G. J., Song S. H., Choi N. H., Ryu J., McDermott B., Cobham V., Park S., Kim J. W., Shin M. S., Yoo H. J., Cho S. C., Kim B. N. (2014). Different clinical courses of children exposed to a single incident of psychological trauma: A 30 month prospective follow up study. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 55, 1226–1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howlader N., Noone A. M., Krapcho M., Garshell J., Miller D., Altekruse S. F., Kosary C. L., Yu M., Ruhl J., Tatalovich Z., Mariotto A., Lewis D. R., Chen H. S., Feuer E. J., Cronin K. A. (2013). SEER cancer statistics review. Retrieved from http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2011/

- Karcher M. J. (2005). The hemingway: Measure of adolescent connectedness: A manual for scoring and interpretation. Unpublished manuscript. San Antonio: University of Texas.

- Karcher M. J. (2008). The cross-age mentoring program: A developmental intervention for promoting students' connectedness across grade levels. Professional School Counseling, 12, 137–143. [Google Scholar]

- Karcher M. J. (2009). Increases in academic connectedness and self-esteem among high school students who serve as cross-age peer mentors. Professional School Counseling, 12, 292–299. [Google Scholar]

- Karcher M. J., Davidson A. J., Rhodes J. E., Herrera C. (2010). Pygmalion in the program: The role of teenage peer mentors' attitudes in shaping their mentees' outcomes. Applied Developmental Science, 14, 212–227. [Google Scholar]

- Karcher M. J., Sass D. (2010). A multicultural assessment of adolescent connectedness: Testing measurement invariance across gender and ethnicity. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 57(3), 274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J., Cicchetti D. (2010). Longitudinal pathways linking child maltreatment, emotion regulation, peer relations, and psychopathology. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 51, 706–716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladd G. W., Price J. M. (1987). Predicting children's social and school adjustment following the transition from preschool to kindergarten. Child Development, 58, 1168–1189. [Google Scholar]

- Langeveld N. E., Grootenhuis M. A., Voute P. A., De Haan R. J., Van Den Bos C. (2004). Quality of life, self‐esteem and worries in young adult survivors of childhood cancer. Psycho‐Oncology, 13, 867–881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linley P. A., Joseph S. (2004). Positive changes following trauma and adversity: A review. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 17, 11–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo Y., Mendell N. R., Rubin D. B. (2001). Testing the number of components in a normal mixture. Biometrika, 88, 767–778. [Google Scholar]

- Meyerson D. A., Grant K. E., Carter J. S., Kilmer R. P. (2011). Posttraumatic growth among children and adolescents: A systematic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 31, 949–964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLachlan G., Peel D. (2000).Finite Mixture Models. New York, NY: Wiley [Google Scholar]

- Muthén L. K., Muthén B. O. (1998-2012). Mplus User’s Guide (7th ed). Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- Nylund K. L., Asparouhov T., Muthén B. O. (2007). Deciding on the number of classes in latent class analysis and growth mixture modeling: A Monte Carlo simulation study. Structural Equation Modeling, 14, 535–569. [Google Scholar]

- Parker J. G., Asher S. R. (1987). Peer relations and later personal adjustment: Are low accepted children at risk? Psychological Bulletin, 102, 357.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phipps S., Klosky J. L., Ogden J.. , Long, A., Hudson, M. M., Huang, Q., Zhang, H., & Noll, R. B. (2014). Posttraumatic stress and psychological growth in children with cancer: Has the traumatic impact of cancer been overestimated?. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 32(7), 641–646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phipps S., Long A. M., Ogden J. (2007). Benefit finding scale for children: Preliminary findings from a childhood cancer population. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 32, 1264–1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pole N., Gone J. P., Kulkarni M. (2008). Posttraumatic stress disorder among ethnoracial minorities in the United States. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 15, 35–61. [Google Scholar]

- Pynoos R., Rodriguez N., Steinberg N., Stuber M., Frederick C. (1998). UCLA PTSD index for DSMIV, Los Angeles, CA: UCLA Trauma Psychiatry Service, unpublished manual.

- Reynolds C. R., Kamphaus R. W. (2004) Behavior assessment system for children (2nd ed.). Manual. Circle Pines, MN: AGS Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson K. E., Gerhardt C. A., Vannatta K., Noll R. B. (2007). Parent and family factors associated with child adjustment to pediatric cancer. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 32, 400–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg A. R., Yi-Frazier J. P. (2016). Commentary: Resilience defined: An alternative perspective. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 41, 506–509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin K. H., Bukowski W., Parker J. G. (2006). Peer interactions, relationships, and groups In Damon W., Lerner R. M., Eisenberg N. (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 3, Social, emotional, and Personality Development (6th ed., pp. 571–645). New York, NY: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz G. (1978). Estimating the dimension of a model. The Annals of Statistics, 6, 461–464. [Google Scholar]

- Southwick S. M., Bonanno G. A., Masten A. S., Panter-Brick C., Yehuda R. (2014). Resilience definitions, theory, and challenges: Interdisciplinary perspectives. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 5, 25338.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg A. M., Brymer M. J., Decker K. B., Pynoos R. S. (2004). The University of California at Los Angeles post-traumatic stress disorder reaction index. Current Psychiatry Reports, 6, 96–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tedeschi R. G., Calhoun L. G. (2004). Posttraumatic growth: Conceptual foundations and empirical evidence. Psychological Inquiry, 15, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Trask P. C., Paterson A. G., Trask C. L., Bares C. B., Birt J., Maan C. (2003). Parent and adolescent adjustment to pediatric cancer: Associations with coping, social support, and family function. Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing, 20, 36–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varni J. W., Katz E. R., Colegrove R., Dolgin M. (1993). The impact of social skills training on the adjustment of children with newly diagnosed cancer. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 18, 751–767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldrip A. M., Malcolm K. T., Jensen‐Campbell L. A. (2008). With a little help from your friends: The importance of high‐quality friendships on early adolescent adjustment. Social Development, 17, 832–852. [Google Scholar]

- Werba B. E., Hobbie W., Kazak A. E., Ittenbach R. F., Reilly A. F., Meadows A. T. (2007). Classifying the intensity of pediatric cancer treatment protocols: The intensity of treatment rating scale 2.0 (ITR‐2). Pediatric Bood and Cancer, 48, 673–677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zebrack B. J., Stuber M. L., Meeske K. A., Phipps S., Krull K. R., Liu Q., Yasui Y., Parry C., Hamilton R., Robison L. L., Zeltzer L. K. (2012). Perceived positive impact of cancer among long‐term survivors of childhood cancer: A report from the childhood cancer survivor study. Psycho‐Oncology, 21, 630–639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]