Abstract

Objectives

Parenting young children with type 1 diabetes (YC-T1D) entails pervasive challenges; parental coping may influence child and parent outcomes. This study used a qualitative descriptive design to describe these challenges comprehensively to inform the user-centered design of an Internet coping resource for parents.

Methods

A “Parent Crowd” of 153 parents of children with T1D onset at ≤ 5 years old submitted textual responses online to open-ended questions about parenting YC-T1D. Systematic coding organized responses into domains, themes, and examples. A supplemental focus group of racial/ethnic minority parents enhanced the sample’s diversity and validated findings from the Parent Crowd.

Results

Similar domains and themes emerged from responses of crowdsourcing and focus group participants. In each domain, parenting YC-T1D was challenging, but there was also substantial evidence of positive coping strategies and adaptability.

Conclusions

The study yielded rich data to inform user-centered design of an Internet resource for parents of YC-T1D.

Keywords: crowdsourcing, parental coping, social support, type 1 diabetes, young children

The incidence of type 1 diabetes (T1D) is increasing among young children (Patterson, Dahlquist, Gyürüs, Green, & Soltész, 2009; Vehik et al., 2007). Young children (aged ≤ 5 years) have limited cognitive, behavioral, and social-emotional capacities, and so, they depend exclusively on their parents for daily T1D care including frequent blood glucose (BG) monitoring, insulin administration, and diet/physical activity regulation to minimize acute and chronic complications of T1D (Diabetes Control and Complications Trial Research Group, 1994; Silverstein et al., 2005). Yet, 73% of the young children exceed the pediatric American Diabetes Association Hemoglobin A1C (HbA1c) target of <7.5% (Chiang, Kirkman, Laffel, & Peters, 2014; Wood et al., 2013), indicating that parents encounter substantial challenges in managing T1D in this age-group. Assisting parents in caring for young children with T1D (YC-T1D) is essential because these patients will have T1D longer, enduring more exposure to risks of complications. Also, hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia may lead to adverse neurocognitive effects such as learning disorders and executive functioning deficits (Cameron, 2015).

Parents of YC-T1D strive to achieve adequate T1D care while meeting typical parenting challenges. Labile self-regulation may impede the consistency of T1D care for young children due to their highly variable and unpredictable behavior, emotions, physical activity, eating, and sleep (Archbold, Pituch, Panahi, & Chervin, 2002; Cathey & Gaylord, 2004; Cole, Dennis, Smith-Simon, & Cohen, 2009; and Pate, O’Neill & Mitchell, 2010). Also, YC-T1D are unable to accurately identify and report symptoms of hypoglycemia or hyperglycemia or understand why daily, unpleasant T1D management tasks are required (Silverstein et al., 2005).

The psychosocial impact of daily care for YC-T1D on parents is substantial. Parents of YC-T1D are at elevated risk of psychiatric symptoms such as depression, anxiety, and sleep disorders, as well as T1D-specific parenting stress and fear of hypoglycemia (Streisand & Monaghan, 2014). Measures of general psychiatric symptoms and T1D-specific adjustment appear to be interrelated (Streisand & Monaghan, 2014). In qualitative studies on psychosocial adaptation in parents of YC-T1D, Sullivan-Bolyai, Deatrick, Gruppuso, Tamborlane, and Grey (2003) and Sullivan-Bolyai, Rosenberg, and Bayard (2006) described the “constant vigilance” required of parents for daily care of YC-T1D. Smaldone and Ritholz (2011) illustrated some of the systemic difficulties that parents of YC-T1D encounter, including kindergarten entry and confusion regarding the role of the child’s primary care physician in diagnosis and treatment. Moreover, some studies suggest that greater parental psychosocial difficulties may negatively impact health and psychosocial outcomes in YC-T1D (Hilliard, Monaghan, Cogen, & Streisand, 2011; Jaser, Whittemore, Ambrosino, Lindemann, & Grey, 2009; Stallwood, 2005). The generalizability of existing qualitative studies is limited by small, convenience samples over-representing White and college-educated parents and, for Smaldone and Ritholz (2011), a retrospective design. More research is needed, using larger, more diverse samples of parents who are raising YC-T1D, to better understand their day-to-day experiences and guide interventions.

Several social support and coping skills training interventions have been tested, yielding mixed effects in terms of improvements in parental psychosocial functioning (Pierce, Kozikowski, Lee, & Wysocki, 2015). Methodological limitations of these studies include the use of homogenous and geographically restricted samples (Sullivan-Bolyai et al., 2010; Patton, Odar, Midyett, & Clements, 2014); lack of stakeholder engagement to guide intervention design and development (Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute, 2016); and broad age/developmental ranges for YC-T1D (e.g., 1–12 years) (Grey, Jaser, Whittemore, Jeon, & Lindemann, 2011; Sullivan-Bolyai et al., 2010). Validation of carefully designed interventions that focus on improving parenting skills and children’s health and behavioral outcomes is clearly needed (Lohan, Morawska, & Mitchell, 2015). The existing quantitative and qualitative research on parenting YC-T1D has not yielded a comprehensive perspective of the daily affective, behavioral, and cognitive challenges that parents identify as the issues for which they most want and need information, help, and support. A deeper understanding of the psychological landscape surrounding early-onset T1D is needed to better inform interventions that improve parental adjustment and parenting skills to enhance outcomes of care (Streisand & Monaghan, 2014).

During the work described in this article, it became clear that Internet delivery of an intervention targeting coping among parents of YC-T1D may be advantageous. Although its incidence may be increasing (Patterson et al., 2009; Vehik et al., 2007), T1D is still uncommon among young children (Dabelea et al., 2007), and so, it is likely that few centers have enough patients who are YC-T1D to populate an ongoing support group for their parents. Even if a thriving support group were created, it is difficult for parents of YC-T1D to attend regularly due to practical obstacles including the challenges of transporting young children, anxiety about separation from their YC-T1D and reluctance to trust others with care of their YC-T1D, availability of child care for their other children, intrusion of other minor illnesses common in this age range, and early bedtimes for children in this age range. Support groups for broader age ranges of children with T1D often do not address the specific issues that concern parents of YC-T1D. While support groups can generate helpful solutions and coping strategies, few, if any, T1D support groups are structured in such a way that coping strategies are archived for future access or evaluated systematically by parents who use them, features that could be incorporated readily into an Internet-based coping resource. Similarly, parents who seek solutions to relatively unique problems may have difficulty finding them in a typical support group unless a parent attending the same session happens to have addressed that same problem successfully. A searchable Internet resource could direct them to coping strategies suggested by other parents who have faced the same or similar problem in the past. Although most of the parents we interacted with during this study use the Internet frequently for T1D-related information, many expressed dissatisfaction that the Internet provides little or no helpful or credible information that is specific to the needs of YC-T1D or their parents. For all of these reasons, the researchers began the present initiative to design, build, and evaluate an Internet coping resource conceived by and for parents of YC-T1D.

The present study describes the first phase of this research in which we characterized parents’ day-to-day experiences and concerns about raising YC-T1D and explored how care for this complex condition has effects that reverberate among YC-T1D and their parents, family members, social networks, and broader communities. We applied a qualitative descriptive design using online crowdsourcing and focus group methods to comprehensively describe the perspectives of a large sample of parents about influences on their lives as parents of YC-T1D. Crowdsourcing is a flexible online activity (Brabham, 2013) that has been applied to problems in diverse fields, including public health, comprising four elements (Brabham, Ribisi, Kirchner, & Bernhardt, 2014): (1) an organization that has a task it needs to be performed (e.g., design an Internet resource meeting YC-T1D parents’ specifications); (2) a community, or crowd, that contributes to achieving those specifications; (3) an online environment that facilitates collaboration between the crowd and the organization; and (4) mutual benefit for the organization and the crowd (e.g., better YC-T1D outcomes, less family distress, and better quality of life). Qualitative description was chosen because it focuses on gaining insights from informants about poorly understood phenomena without interpreting or inferring from the data (Neergaard, Olsen, Andersen, & Sondergaard, 2009). The authors selected the crowdsourcing approach as described in the Methods section because it appeared to offer a way to obtain substantial information from eligible YC-T1D parents efficiently. We expected the crowdsourcing and focus group methods to yield the content domain for the planned Internet coping intervention and provide extensive information of interest to health care providers who care for children with T1D and their families.

Method

Two methods elicited responses to open-ended question from parents: Parent Crowd and Diversity Focus Group. An institutional review board reviewed and approved this protocol, including the process of obtaining electronic informed consent from participants.

Parent Crowd

Participants

Recruitment methods included e-mail contact with eligible parents of patients followed within a multisite children’s health system spanning North Florida, Central Florida, and the Delaware Valley, diabetes-focused Web sites, blogs, and Facebook groups, or contacts with North American T1D clinicians. Any parent or legal guardian of a child with T1D currently ≤9 years old and diagnosed at ≤5 years old was eligible. Prospective participants received an e-mail or online announcement with basic information about the project and a link to an electronic informed consent form, which, when submitted, presented an online demographic information form for completion. Participants reported their age, gender, race, ethnicity, educational attainment, occupational category, and degree of use of the Internet and social media in general and specifically about T1D, as well as the child’s age, gender, race, ethnicity, date of T1D diagnosis, and insulin delivery modality. Participants provided an e-mail address and contact information to enable contact during the study and compensation. Given that many more mothers registered than fathers, we encouraged mothers to share the online announcement with their spouse or significant other (if applicable), which increased the number of father participants from 10 fathers in the first few weeks to a final total of 22.

Yammer (www.yammer.com) is an online, private social network that was used for distributing questions to participants and obtaining their typed response narratives. Yammer was chosen because our institution has successfully used this platform for its Parent Virtual Family Advisory Council. Using Yammer allowed parents to view and reply to each other’s responses (i.e., to interact as part of a “crowd”), consistent with the crowdsourcing elements listed previously. On completion of demographic information and verification of eligibility, parents were invited to join the Yammer network via e-mail and then followed instructions to register as members of the Parent Crowd. Of note, Yammer is the platform being used to obtain stakeholder feedback while developing and designing the proposed intervention; a novel Web site will be systematically developed and designed as the intervention.

A total of 218 parents authenticated the electronic informed consent form. Of these, 30 were ineligible, due to providing no e-mail address or contact information, the child’s current age ≥10 years, or the child’s age at diagnosis ≥6 years. Of the remaining 188 eligible parents, 18 did not register on Yammer and another 17 did not respond to any questions, yielding a sample of 153 active Parent Crowd participants. Chi-square, Fisher’s exact, and t-tests revealed that there were no significant differences on any demographic or clinical variables between the 35 parents who did not participate actively and the 153 who did.

Table I shows demographic characteristics of the 153 Parent Crowd participants and their 139 YC-T1D. The parents were predominantly Non-Hispanic Caucasian (90.2%), mothers (84.6%), and the sample reflected above average status in terms of educational and occupational attainment, household income, and frequency of general and T1D-specific Internet use. Most of their children with T1D were using insulin pumps (67.6%) and/or continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) (69.1%), and parents reported an average most recent HbA1c of 7.7% (SD = 1.0%). There was no active effort to recruit internationally, but 15 participants were from countries other than the United States, including Canada (7), Australia (1), Russia (2), Greece (1), Northern Ireland (1), Israel (2), and Macedonia (1). One-third of the children (33.4%) were currently >6 years, but <10 years old. Those parents were asked to respond to questions based on when their children were <6 years.

Table I.

Demographic Characteristics of Parent Participants and Their Children With T1D

| Parent Crowd Group |

Diversity Focus Group |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child characteristics | n | Mean (SD)/percent | n | Mean (SD)/percent | |

| Age (years) | 139 | 5.50 (2.00) | 8 | 4.75 (1.39) | |

| Age at diagnosis (years) | 138 | 2.63 (1.45) | 8 | 2.63 (1.30) | |

| Duration of T1D (years) | 138 | 2.43 (1.97) | 8 | 1.63 (1.19) | |

| Most recent HbA1c (%) | 134 | 7.69 (0.92) | 7 | 8.43 (0.09) | |

| Male/female | 65/72 | 46.8/51.8 | 3/5 | 37.5/62.5 | |

| Race | Caucasian | 123 | 88.5 | 2 | 25.0 |

| African American | 2 | 1.4 | 5 | 62.5 | |

| Other/Multiple | 13 | 9.4 | 1 | 12.5 | |

| Ethnicity | Hispanic/Other | 9 | 6.5 | 3 | 37.5 |

| Non-Hispanic | 124 | 89.2 | 5 | 62.5 | |

| Insulin regimen | Insulin pump | 94 | 67.6 | 3 | 34.5 |

| Multiple daily injections | 38 | 27.3 | 5 | 62.5 | |

| Conventional/sliding scale | 4 | 2.9 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Use of continuous glucose monitor (Y/N) | 96/42 | 69.1/30.2 | 5/2 | 62.5/25.0 | |

| Participant characteristicsa | |||||

| Age (years) | 153 | 36.39 (5.57) | 12 | 34.42 (7.04) | |

| Relationship to child | Biological mother | 129 | 84.6 | 8 | 61.5 |

| Biological father | 22 | 14.4 | 3 | 23.1 | |

| Other | 2 | 1.4 | 2 | 15.4 | |

| Education | HS diploma | 12 | 7.8 | 4 | 33.3 |

| Some college/technical school | 41 | 26.8 | 5 | 41.7 | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 54 | 35.3 | 1 | 8.3 | |

| Advanced degree | 45 | 29.4 | 2 | 16.7 | |

| Occupation | Not employed outside home | 44 | 28.8 | 4 | 33.3 |

| Operational/technical level | 29 | 19.0 | 4 | 33.3 | |

| Managerial level | 48 | 31.4 | 3 | 25.0 | |

| Professional level | 26 | 17.0 | 1 | 8.3 | |

| Household annual income | <$50k | 32 | 20.9 | 5 | 41.7 |

| $51k–$100k | 63 | 41.2 | 5 | 41.7 | |

| $101k-$150k | 34 | 22.2 | 2 | 16.7 | |

| >$150k | 17 | 11.1 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Internet use, general | Daily | 103 | 67.3 | 4 | 33.3 |

| Often | 23 | 15.0 | 2 | 16.7 | |

| Sometimes | 19 | 12.4 | 4 | 33.3 | |

| Never | 3 | 2.0 | 1 | 8.3 | |

| Internet use, T1D-related | Daily | 60 | 29.2 | 2 | 16.7 |

| Often | 45 | 29.4 | 1 | 8.3 | |

| Sometimes | 27 | 17.6 | 5 | 41.7 | |

| Never | 11 | 7.2 | 2 | 16.7 | |

One grandmother provided minimal information.

Procedures

The researchers met monthly by conference call with six Family Advisors, who were also members of the Parent Crowd, for discussion of all research plans and editing of draft questions and other study documents. Questions were open-ended queries requiring free-text, typed replies. A total of 19 questions were sent to participants on Yammer in the order shown in Table II during five separate 1-week periods distributed over about 4 months. Clusters of three to five questions were posted and left open for 7 days. A staggered approach was used to minimize response burden for participants and to provide time for the research team to conduct qualitative analysis of responses (see below). Of the 19 questions, 13 were specified a priori by the researchers to inquire about parental burden, emotional impact on parents, impact on the child, family, and other social relationships, and health care system interactions. The remaining six questions were added after reviewing responses to earlier questions, such as some parents spontaneously describing a “benefit-finding” phenomenon and others mentioning the impact raising YC-T1D has on emotional and physical intimacy. The researchers therefore added six questions focused on such topics. Participants were paid $1–$5 on a reloadable prepaid debit card, depending on question complexity, for replying to a given question.

Table II.

Open-Ended Questions Distributed via the Internet to Crowdsourcing Participants

| Week 1 |

|---|

| Q1. In what ways has your life changed since your child was diagnosed with type 1 diabetes? (n = 126 replies; 82.3%) |

| Q2. What challenges are you facing in managing your child’s diabetes? (n = 132 replies; 86.2%) |

| Q3. What do you do now that helps you cope with those challenges? (n = 129 replies 84.3%) |

| Q4. How does being a parent of a young child with diabetes affect your relationships with others? (n = 129 replies; 84.3%) |

|

Week 2 |

| Q5. In what ways has your child’s life changed since he/she was diagnosed with T1D? (n = 127 replies; 83.0%) |

| Q6. How does your child’s behavior or temperament affect your ability to take care of diabetes? (n = 132 replies; 86.2%) |

| Q7. How has taking care of your child’s diabetes affected your other children, if you have any? (n = 129 replies; 84.3%) |

| Q8. How do you fit diabetes care into your daily family life? If your child is currently ≥6, how did you fit diabetes care into your daily family life when he/she was ≤5? (n = 128 replies; 83.6%) |

| Q9. How have you fit your child’s diabetes care into special occasions (holidays, birthdays, travel)? (n = 132 replies; 86.2%) |

|

Week 3 |

| Q10. What could your diabetes care team do to be more helpful to you in caring for your child? (n = 131 replies; 85.6%) |

| Q11. Looking back, is there some aspect of caring for your child that you could have been better prepared for? (n = 130 replies; 85.0%) |

| Q12. Knowing what you know now, what is the most important advice you would give to a parent whose young child was just diagnosed? (n = 133; 86.9%) |

| Q13. What advice or information about treating young children, toddlers, and infants with T1D would you give to your child’s doctor or health care team? What would you like them to know? (n = 128 replies; 83.7%) |

|

Week 4 |

| Q14. In what ways, if any, has raising a young child with diabetes been a positive experience for you? (n = 118 replies; 77.1%) |

| Q15. In what ways, if any, has diabetes been a positive experience for your young child? (n = 118 replies; 77.1%) |

| Q16. What else would you like us to know about your experience raising a young child with T1D that was not addressed in the questions you have already answered? (n = 115 replies; 75.2%) |

|

Week 5 |

| For those living with a spouse or partner: |

| Q17. How do you and your spouse or partner divide responsibility for your child’s diabetes care? How acceptable is this arrangement to each of you? |

| Q18. In what ways has your child’s diabetes affected the emotional intimacy or closeness of your relationship with your spouse or partner? |

| Q19. In what ways has your child’s diabetes affected the physical intimacy or closeness of your relationship with your spouse or partner? |

| For those not living with a spouse or partner: |

| Q17. How successful have you been in finding others who you trust to care for your child with T1D? |

| Q18. In what ways do you do things just for yourself, to give yourself a break? |

| Q19. In what ways has your child’s diabetes affected your life in the areas of dating and romance? |

| (n = 94 replies to either set of questions; 61.4%) |

Each question was preceded by a reminder to focus on the experience of parenting a child with T1D who is < 6 years old. Participants responded in free-text narrative comments.

Qualitative Coding

Consistent with the qualitative descriptive design, qualitative content analysis was used to code the data by tagging data segments with descriptive, low-inference codes that allowed grouping and sorting similar topics and perspectives (Neergaard et al., 2009). A cadre of 11 qualitative coders with previous behavioral T1D and qualitative research training and experience, including three of the authors and eight research specialists, was assigned to three- to four-person teams. After a given cluster of three to five questions was completed, a research specialist created a de-identified document consisting of all participants’ responses to those questions. The principal investigators assigned each coding team an equal number of pages from the text document for qualitative coding. Individual members of a given team independently reviewed the assigned transcript pages and identified primary themes and examples of each. Consistent with qualitative research methods, which achieve rigor by using a systematic and transparent process and obtaining multiple perspectives from a team approach to coding qualitative data (Wu, Thompson, Aroian, McQuaid, & Deatrick, 2016), team members met after independently coding the data to discuss discrepancies and achieve consensus on the themes for each assigned question. Coding team leaders brought the results of their team’s work to the researchers for compilation and integration.

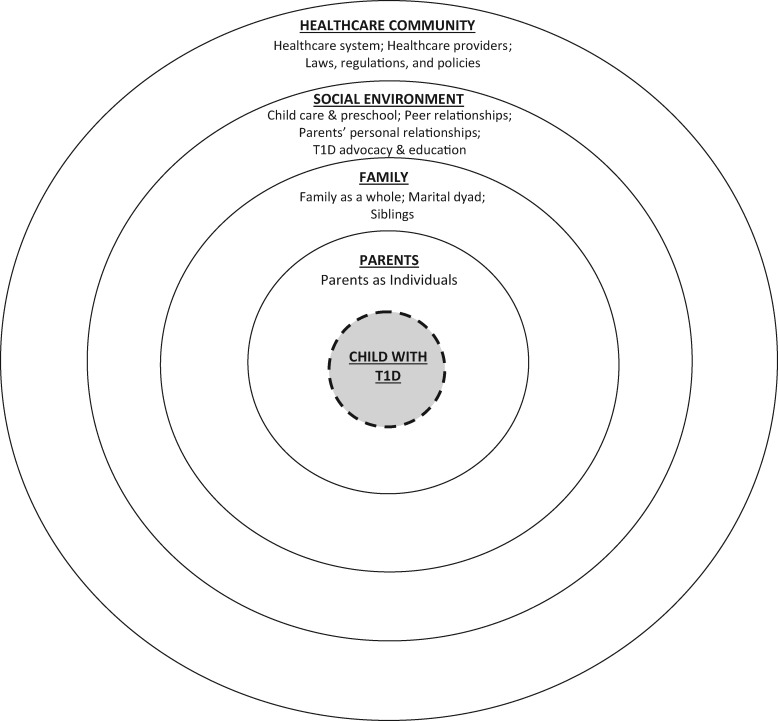

After coding the first 2 weeks of questions (nine questions total; Table II), the research team recognized that the coding results could be organized into a taxonomic “social-ecological model” (Figure 1) that summarized the various levels of influence that affect, and are affected by, the experience of parenting YC-T1D. For each level of this social-ecological model, the team identified themes subsumed in that level and identified examples illustrating the diversity and scope of coping challenges faced by these families. Two drafts of the social-ecological model and corresponding taxonomy were distributed to crowdsourcing participants for feedback. The initial draft was presented and organized in the same way as is presented in Figure 1 (social-ecological model) and the Supplementary Material (corresponding taxonomy). Consistent with Lincoln and Guba’s (1985) procedure for member checking, Parent Crowd participants were asked to review the themes and examples for completeness, make suggestions for additions or subtractions, and provide suggestions for rewording of the material. Forty-six participants provided feedback; most had suggestions regarding additional examples that could be integrated into existing themes, although several new themes were added. For example, the theme “Conflicting Treatment Goals” along with several new examples was added to the taxonomy after the first round of participant feedback. Three members of the research team reviewed participant feedback and integrated it into a second draft of the taxonomy. For the second draft, participants were informed that their feedback from the last draft was integrated and asked to provide any additional feedback. No participants provided feedback, and a final version of the model and taxonomy was posted on Yammer for participants to view at any time.

Figure 1.

A social-ecological framework of the domains of influence affecting the health and quality of life of young children with type 1 diabetes and their families.

Diversity Focus Group

Because the Parent Crowd sample was predominantly Non-Hispanic Caucasian, the research team implemented an additional effort to validate the emerging social-ecological framework in parents of YC-T1D who were more demographically diverse. After distributing the 19 questions to the Parent Crowd, we engaged a separate group of parents of YC-T1D who participated in a “Diversity Focus Group.” The goals of the Diversity Focus Group were to explore whether the social-ecological framework obtained from the Parent Crowd fit focus group participants’ experiences and to gain a preliminary sense of whether there were key issues that had not been introduced by the Parent Crowd.

Participants

Diversity Focus Group participants were 13 parents of eight children with T1D who were ≤7 years old (M = 4.75, SD = 1.39), diagnosed with T1D before age 6 (Range = 1–5 years; M = 2.63, SD = 1.30), Hispanic (n = 3) or African American (n = 5), and receiving T1D care at one of three sites of the children’s health care system in North Florida, Central Florida, or Delaware. Table I presents demographic characteristics of the focus group parent participants and their children with T1D.

Procedures

The researchers used an electronic medical record query to identify 114 patients of the children’s health system who were currently ≤9 years old, diagnosed with T1D at ≤5 years, and whose parents reported that the child was any race except Caucasian or any ethnicity except Non-Hispanic. Based on the literature on focus group methodology (Krueger & Casey, 2009), 15 participants (five at each site) were desired, given that a larger group might have inhibited some parents from participating actively. To account for possible no-shows, we over-recruited potential participants. Parents were contacted by telephone or e-mail and invited to participate in the focus group until 27 caregivers of 15 YC-T1D agreed to attend the focus group. Of those, 13 parents of eight YC-T1D attended. Although no effort was made to inquire about reasons for not attending, several parents called research coordinators before the focus group to inform them that their child care plans fell through and they therefore could not make it. Understandably, those parents did not feel comfortable leaving their YC-T1D with our child care personnel (see below).

A single focus group was conducted by video conference with participants and group leaders convening at each of the three sites simultaneously. Parents gave informed consent before the focus group. The prior 19 crowdsourcing questions were combined into six questions for the focus group, covering the same content. The focus group was audio-recorded and each group leader took detailed notes. Each of the three sites had a focus group facilitator (all Non-Hispanic, White), who alternated asking questions to the entire group and also ensured that participants who wished to speak were acknowledged. The focus group was conducted in the evening and child care was provided for YC-T1D and their siblings. Participants were invited to join the Parent Crowd and contribute responses to future questions. Four of the participants who were parents of four separate YC-T1D accepted this invitation.

Qualitative Coding

Two researchers (who were also two of the focus group facilitators) and two research specialists with extensive involvement in coding the Parent Crowd data independently reviewed focus group audio recordings. The purpose of this was to determine whether the themes and examples in the tentative social-ecological framework derived from the crowdsourcing methods adequately captured the perspectives of the focus group participants.

Results

The results presented below summarize the validated social-ecological framework and taxonomy that will guide the future design and development of the Web site so that, when introduced, the Web site is ready to address many common challenges for parents of YC-T1D and to be adaptable to addressing other challenges that were not specifically anticipated during the design phase. As this work proceeds to making concrete decisions about the structure, content, and features of the planned Web site, the social-ecological framework (Figure 1) will be revisited continuously with ongoing Parent Crowd feedback to ensure that the team designs a Web site that meets the expressed needs of parents of YC-T1D and that it is sufficiently flexible to enable continued evolution of the Web site in response to the needs of future users.

Parent Crowd

Between 94 and 133 (61.4–86.9%) of the 153 Parent Crowd participants submitted replies to the 19 questions, 65 participants (42.4%) answered every question, and 100 participants (65.3%) submitted replies to at least 15 questions. Replies on Yammer averaged 105.6 words in length (Median = 126 words).

Diversity Focus Group

Each of the four research team members who reviewed focus group recordings aligned the focus group participant reports with the coding scheme derived from the Parent Crowd data. They independently concluded that, although some new examples of certain themes were identified during the focus group, no new themes or domains emerged and all new examples could be subsumed under existing themes and integrated into the taxonomy. The 13 participants were asked directly how being a member of a racial or ethnic minority may have affected their experiences or feelings as parents of YC-T1D. No parent offered any such examples and several had slightly negative reactions to being asked this question, a position that received considerable nonverbal support from other participants. The focus group findings therefore confirmed the emerging perspective obtained via crowdsourcing and the findings below reflect parents’ perspectives regardless of participation format.

Overview of Results

Findings were organized using a social-ecological framework (Figure 1) with several domains of influence emanating outwardly from YC-T1D at the center, to parents as individuals, the family system, the family’s social network, and the broader health care community. Many examples contributed by parents guided the research team’s construction of a taxonomy of issues confronted by these families (see Supplementary Material). Consistent with standard qualitative research practices, rather than quantifying endorsement of themes, differing perspectives were qualified when they occurred (Elo, Kääriäinen, Kanste, Pölkki, Utriainen, & Kyngäs, 2014; Wu et al. 2016). Most parent perspectives were virtually universal and those that were not are identified by qualifying terms like “some parents” and specifying the varying perspectives.

The Child With T1D

In response to questions about parenting YC-T1D, parents provided rich details about how managing T1D was often complicated by the developmental characteristics of children in this age-group. They indicated that the cognitive capacity of young children limited their YC-T1D’s understanding of the necessity for T1D care and their ability to recognize and report hypoglycemia. Growth spurts, labile glucose metabolism, and variable eating and activity all complicated the care of YC-T1D. Parents emphasized YC-T1D’s limited comprehension of the necessity of T1D requirements and their increasing awareness that other children do not face those demands, which quickly develops. Some parents reported that their YC-T1D reacted negatively to food and play restrictions and painful procedures. Routine T1D tasks, frequent medical appointments, and the need for constant adult supervision limited spontaneity in eating and play. Some parents expressed that T1D “robbed” their children of a “carefree spirit” and “just being a kid” and others feared that inadequate T1D control could affect their children’s cognitive development.

Many parents also identified positive effects on their YC-T1D, including resilience, self-efficacy, self-control, social maturity, responsibility, empathy toward others with special needs, health consciousness, better math and nutrition knowledge, and positive attention from others. Others argued that there is nothing positive about their child being afflicted by T1D and a few were slightly offended by questions about positive effects. For example, a mother wrote, “I’m sorry, I can’t give a positive answer. Unlike other responders, I’m not going to lie or look for some silver lining. After 2.5 years and no end in sight with this horrible disease, it has been a total nightmare.”

Parents as Individuals

T1D care had a pervasive impact on parents’ personal and work lives. They reported fatigue from constant vigilance and sleep deprivation, lack of social support, and an unremitting focus on the child’s eating. They mourned the loss of a more spontaneous lifestyle, felt isolated, and expressed grief, guilt, anger, and worry about the child’s future. Some parents reported that they suffered from mental health problems (e.g., depression, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress) and wanted better access to appropriate mental health services.

A major parenting concern was how to discipline YC-T1D, specifically how to balance empathy for their YC-T1D with teaching them to be responsible for their actions. Distinguishing negative affect and acting out behavior from symptoms of T1D (i.e., high and low BGs) was difficult and generated parents’ uncertainty as to whether to discipline behavior that could be a reflection of the child’s BG level. Some parents admitted to being lax with discipline because YC-T1D “have enough to deal with.”

Virtually all parents vividly recounted their experiences and feelings regarding the new diagnosis of T1D. On news of their children’s diagnosis of T1D, parents reported feeling “shocked,” overwhelmed with T1D responsibilities, and unprepared to master complex T1D knowledge and skills. Over time, parents adapted, achieving what several called “a new normal.” Most accepted that BG levels were capricious, even with careful adherence. Most parents achieved a balance between striving for “perfect” control and living as normally as possible. For many, adopting an insulin pump and/or CGM restored some flexibility and normalcy.

T1D care also had employment implications for parents such as taking less demanding jobs, turning down promotions, or choosing not to work outside the home. For some working parents, employers and coworkers understood the difficulty of balancing work with T1D care. A few parents expressed guilt about receiving special concessions, while others reported poor work performance due to T1D demands.

Parents used diverse coping methods such as recognizing that new technology greatly improved T1D care and quality of life, savoring uncommon moments when T1D did not dominate the child’s life, and engaging in T1D advocacy and educational initiatives. Some parents objected to the notion that they had to “cope” with their children’s T1D, as this suggested that YC-T1D were a liability rather than children they deeply love.

Parents universally agreed that life without T1D would be preferable, but many also noted positive effects (i.e., improved organization and time management and enhanced attentiveness, assertiveness, and empathy). Parents reported that they made healthier choices for their families and achieved better work–family balance. They developed a unique bond with their children and were inspired by their strength and resilience. Some parents reported adopting a deeper faith and spirituality and greater appreciation for the “important things in life.” Being involved in the diabetes community led to forming new friendships and deriving meaning from advocacy efforts. However, like some parents’ reactions to the question about positive child effects, a few parents could not relate to the idea of positive parent effects.

The Family

Family includes the family as a whole and the marital dyad and siblings as family subsystems. When more than one family member had T1D, impact on the family was even greater.

The Family as a Whole

The financial impact of T1D often limited family “extras,” such as vacations, gifts, and investments to “make ends meet.” Family activities (e.g., meals, outings) required extra planning to accommodate T1D care. Unplanned T1D-related incidents (e.g., hypoglycemia) often interrupted family events. Special occasions (e.g., birthdays, holidays) required new ways of celebrating. Many replaced food as a focal point of family celebrations with some other focus. Again, positive effects of T1D were reported, including family togetherness, improved family communication, and a healthier family lifestyle.

The Marital Dyad

Many parents reported that their constant focus on T1D care challenged their physical and emotional intimacy. Parents who were married or partnered struggled to spend time alone as a couple and single parents noted obstacles to dating. Domination of the couple’s conversations by T1D disrupted emotional intimacy, while sleep disruption and exhaustion impeded physical intimacy. For some, T1D seemed to strengthen their trust and reliance on each other and frequent communication and shared decision making about T1D seemed to improve communication in general.

Single parents emphasized the burden of sole responsibility for daily T1D care. For couples, family management of T1D tasks and responsibilities ranged from sole responsibility to equal sharing. Reactions to unequal divisions of labor also varied, ranging from acceptance to resentment. Sharing responsibility and working together as a couple was fulfilling for some parents, whereas others described disagreement about T1D goals. The care and financial demands of raising YC-T1D also impacted some parents’ decisions about having more children.

Siblings

Effort devoted to T1D care also affected siblings. Parents reported being less attentive to, and having limited “quality time” with, their other children. Some siblings showed resentment through attention seeking, like pretending to have T1D or teasing the child with T1D. Witnessing T1D tasks or severe hypoglycemia was upsetting for many siblings, and some worried that T1D was their fault and/or that they might also develop T1D. Many parents addressed such problems by giving siblings a special T1D caretaking role or involving them in advocacy initiatives. Parents also acknowledged positive sibling effects, such as developing caring behaviors for the YC-T1D and compassion for children with medical issues. Siblings also learned that “the world does not revolve around them.”

The Social Environment

The social environment for these families includes relationships with child care and preschool staff, peers of YC-T1D and their parents, and adult relatives and friends.

Child Care and Preschool

Parents reported major difficulty engaging babysitters, daycare programs, and preschools who would accept responsibility for T1D care. Child care options were constrained by the capacity of babysitters to learn and carry out T1D tasks and by parents’ confidence that the babysitter could do so. For most families, only a few relatives, often grandparents, met these criteria, but many did not live near relatives and some parents were concerned about excessive imposition on relatives who did live near them. Nearly all parents reported anguish about relinquishing control of their child’s T1D care. They gradually learned to trust others to make good decisions for their children, but only after lengthy, close communication about their children’s BG levels, insulin dosing, and eating. Parents dedicated hours to training others, being available by phone, and some parents often left work to perform T1D tasks instead of relying on others. Parents expressed optimism about emerging technologies that enable remote monitoring of their children’s BG levels.

Parents struggled to find safe and willing daycare providers or preschools. Most facilities were not legally required to accommodate children with special needs and so they often refuse responsibility for YC-T1D. Medical daycare facilities were limited and expensive. Kindergarten entry created anxiety for parents, and many were torn between homeschooling versus sending the child to school. Parents who chose the latter had to advocate assertively to obtain appropriate accommodations for their YC-T1D, such as access to a full-time school nurse. Parents of YC-T1D who attended kindergarten reported that they missed more class time and school days than their peers.

Peer Relationships

Relationships of YC-T1D with their peers and peers’ parents also raised issues. Peers of YC-T1D sometimes worried about “catching” T1D or flaunted the child’s dietary constraints, making the child feel stigmatized and isolated. Independent play dates were problematic for older YC-T1D because this required either enlisting other children’s parents to supervise and manage their T1D or restricting these events to their own homes. The latter option was the most common, in part because parents of YC-T1D were reluctant to delegate T1D responsibilities to other children’s parents and, in part, because few friends’ parents were comfortable taking on T1D care.

Parents’ Personal Relationships

Parents’ responsibilities for T1D care also affected their relationships with relatives and friends. Many parents explained that some friends lacked empathy about the demands of raising YC-T1D and judged them for “overprotecting” the child and “venting” about T1D-related stress. Parents were displeased with friends and relatives who defined their children solely in terms of T1D rather than showing interest in other areas of their lives. Some acknowledged resenting parents whose young children did not have T1D. Parents revealed that soon after diagnosis, their “true friends” revealed themselves. Many parents found helpful support in relationships with relatives with T1D and other parents of YC-T1D, experiencing camaraderie and understanding rarely evident with other adults. This empathy normalized their situations and allowed parents to share advice and vulnerabilities. Many of these relationships were online. When parents reported in-person friendships with other parents of YC-T1D, an added benefit was the opportunity for YC-T1D to play together, which diminished their isolation and resentment about diet and play restrictions.

T1D Advocacy and Education

Many parents reported deriving considerable satisfaction and a sense of personal meaning through their involvement in T1D advocacy and education activities. Educational efforts included educating other adults with correct factual information about T1D causes, treatment, and irreversibility and its differentiation from other forms of diabetes. Several parents noted that they had essentially become diabetes educators due to repeated interactions of this kind. Many parents felt an obligation to become actively involved in T1D advocacy efforts such as fundraising, participation in health fairs and T1D awareness campaigns, and lobbying of government and institutional officials on behalf of children with T1D. Many parents noted that they had established deep, lasting friendships with other parents of YC-T1D through their involvement in such advocacy efforts.

The Health Care Community

The relevant health care community includes the health care system (policies and procedures in health care settings, pharmacies, and insurance companies), health care providers (the T1D specialty care team and other health care providers), and the legal/regulatory environment.

The Health Care System

Policies and procedures of health care facilities, clinical practices, pharmacies, and insurance plans often created frustration for parents. Clinic policies that prohibited starting insulin pumps and CGMs until children reach a certain age were particularly trying. Scheduling difficulties and long periods in waiting rooms were typical. Parents recommended better care coordination and communication to minimize unnecessary health care visits and seemingly contradictory advice from different members of the T1D care team. Frustrations with health care systems were compounded by organizations that do not accommodate the needs of young children and their families (e.g., published content and guidelines specific to YC-T1D were not available or easily located).

Parents devoted much effort to dealing with insurance companies to understand seemingly illogical coverage restrictions, obtain authorizations, document the need for frequent procedures (e.g., BG checks, injections), appeal denials of coverage, and obtain reimbursements. Parents desired more help from health care providers around those issues. Pharmacies were similarly aggravating, often not providing timely refills and not carrying necessary supplies (e.g., diluted insulin). Some parents were concerned that the profitability of medical devices and pharmaceuticals may impede progress toward a cure.

Health Care Providers

Most parents greatly appreciated T1D specialty health care providers for their expertise and dedication, but also wanted more support, as exemplified below. T1D specialists sometimes failed to grasp the perseverance and emotional support parents need to care for YC-T1D. Parents desired greater empathy, praise, and confidence-building, as well as appreciation that managing YC-T1D is complex and often capricious. Some parents felt judged unfairly by T1D specialists and sought individualized approaches to care rather than a “one size fits all” approach. Objection to a standard regimen was most evident about eating. Given the variable eating habits of young children, T1D specialists who expected rigid dietary adherence were particularly dismaying. Parents also expected T1D specialists to inform them about community resources for nonmedical issues, such as school and social support, and to be well informed about new technology (e.g., CGM and smart-phone applications). Many parents also wanted T1D specialists to discuss mental health topics and to provide better access, or referrals, to mental health services.

Soon after the T1D diagnosis, parents desired more accessibility, personal attention, follow-up appointments, and check-ins from T1D specialists. Some parents preferred a greater depth of T1D education earlier on; others were satisfied with the “basics” to allow time for assimilating new information and skills. Many parents felt strongly that T1D specialists should inform parents about, and be willing to prescribe, pumps/CGM sooner after diagnosis. In contrast to their views of T1D medical specialists, parents were quite dissatisfied with primary care providers and non-T1D specialists (e.g., ophthalmologists, otolaryngologists, and emergency medicine physicians). These providers often conveyed ignorance about T1D, confused type 1 and type 2 diabetes, and attributed symptoms of T1D in young children to normal development. Emergency Departments were often seen as poorly prepared to manage T1D emergencies.

Laws, Regulations, and Policies

Parents reported that laws, regulations, and policies such as those concerning family medical leave, public assistance for medical expenditures, and school accommodations required learning a “new language.” Many thought this process was overwhelming, but often felt empowered once they understood the “system” and could advocate for their YC-T1Ds’ rights. Some reported that they wanted and needed guidance in becoming more effective advocates for their children.

Discussion

This study sought to describe the perceived needs, challenges, and coping methods of parents of YC-T1D in multiple life domains. Parent perspectives were elicited through open-ended questions delivered via online crowdsourcing or focus group methods. Their voluminous responses were organized into a social-ecological taxonomy that placed the child with T1D at the center and identified challenges at the levels of parents as individuals, family systems, social networks, and the broader health care community and health care system. As this work proceeds, crowdsourcing will permit iterative reevaluation and refinement of this taxonomy.

In each life domain, parenting YC-T1D was described as extremely complex and challenging. The impact of T1D pervades daily life for these families. Parents struggled to normalize their personal and family life and balance controlling T1D with helping YC-T1D regain the spontaneity and carefree spirit enjoyed by children without T1D. Although parents faced new dilemmas as YC-T1D grew older (e.g., starting kindergarten, playing away from home), adjusting to the new diagnosis of YC-T1D was uniquely challenging. Parents had many recommendations for health care systems that could have facilitated initial adjustment to T1D by their families. Most parents eventually achieved a “new normal” through positive reframing (e.g., emphasizing personal growth in themselves, the child with T1D, and their other children) and putting greater emphasis on their family life and relationships with other families with T1D. They often experienced disappointment and frustration with others who did not appreciate the unique needs of YC-T1D and their parents.

In addition to a thorough portrayal of the complex challenges faced by parents of YC-T1D, the present study also revealed substantial evidence of positive coping strategies used by most of these parents and of their admirable adaptability. These included the concept of achieving a “new normal,” in which the requirements of T1D care become so ingrained in the family’s routines that they take on a level of emotional significance similar to that of other “normal” demands placed on families by daily life. Other evidence of parents’ and families’ adaptability can be seen in their numerous creative solutions to common practical problems in ensuring safe and effective care for their YC-T1D, the substantial “benefit-finding” that parents expressed, and the resistance of some parents to the idea that parenting YC-T1D is so onerous that it requires “coping.”

Many of the study findings were consistent with prior research. Parents of YC-T1D experience many challenges adjusting to life after the diagnosis. The information we obtained about parents’ psychological distress, fear of hypoglycemia, sleep disruption, and social isolation has been identified by others (Pierce et al., 2015; Streisand & Monaghan, 2014). Also consistent with existing research, our findings indicate that parents of YC-T1D are faced with physiological and developmental challenges related to this age range, including anticipation of neurocognitive consequences, labile child self-regulation, and limited cognitive and linguistic capacity, as well as concern about the YC-T1D coping abilities and emotional adjustment of YC-T1D (Pierce et al., 2015; Streisand & Monaghan, 2014). The pervasive impact of T1D on parents’ personal, family, and social relationships and professional lives due to their need to closely monitor their child was also consistent with findings from the Sullivan-Bolyai et al. (2003) qualitative study emphasizing that these parents’ lives are marked by constant vigilance.

This work introduces the use of crowdsourcing (Brabham, 2013; Brabham et al., 2014) as an efficient and viable method of obtaining the perspectives of potential Web site users that enabled the research team to develop a thorough depiction of the psychological landscape encountered by these families. In this study, the crowdsourcing methods were supplemented with implementation of a Diversity Focus Group in an effort to address their missing representation in our crowdsourcing approach. The findings from the Diversity Focus Group validated that the perspectives obtained from the broader Parent Crowd also fit their experiences. However, using a single focus group to obtain the perspectives of minority parents rather than replicating the crowdsourced design with a larger sample of racial and ethnic minorities likely precluded determining whether minorities have unique experiences not captured by this study. Although it is tempting to conclude that the challenges that were identified by both groups, the crowdsourcing and focus groups, are human challenges faced ubiquitously by parents of YC-T1D regardless of their racial or ethnic backgrounds, future research using crowdsourcing methods should include methods to ensure proportional representation of parents from diverse backgrounds including racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic status as well as levels of health literacy and Internet fluency.

Our findings contribute new perspectives on raising YC-T1D and valuable insights for future quantitative studies and intervention trials. First, this is the only study that has used crowdsourcing methods to collect and organize a large amount of qualitative data regarding daily experiences of a specific clinical population. This study demonstrates that qualitative research can be achieved with a sample size typical of quantitative studies in pediatric psychology rather than only a few dozen participants. Without the constraints of having selected a narrow range of psychological variables for study, the open-ended assessment approach taken here illuminated many parental perspectives that have not been reported elsewhere. Compared with previous studies, this study had a comparatively larger sample size and a broader focus on the psychosocial landscape surrounding the complex challenges these families face. Parents contributed numerous examples of these challenges.

Second, our findings underscore the pervasiveness of daily challenges faced by parents of YC-T1D. Our study confirms Sullivan-Bolyai et al.’s (2003) “constant vigilance” concept in a larger sample of parents and yielded many pertinent examples of those challenges. In this study, the pervasive impact of raising YC-T1D was evident across all facets of parents’ day-to-day lives. Moreover, this constant vigilance has persisted despite recent advances in technology (e.g., CGM, smart-phone applications) that facilitate remote monitoring by parents. Our findings confirm that an accessible coping resource for parents of YC-T1D could be extremely helpful.

Third, our findings illustrate that YC-T1D care can impact parents’ relationships with others. The value of shared responsibility for care between parents has been reported elsewhere (Sullivan-Bolyai et al., 2006; Smaldone & Ritholz, 2011), but our larger sample provides insight into the variability in T1D collaboration between parents, and its impact on emotional and physical intimacy. While many parents share responsibilities for T1D management equitably, in many other families, one parent exerts primary or even exclusive responsibility for T1D care. Division of responsibility for most families, whether negotiated explicitly or not, tends to fall somewhere along this spectrum. For some couples, T1D care is a substantial barrier to emotional and physical intimacy, whereas others note that it has had positive effects on their relationships with spouses or partners. Couples adapt to the demands of T1D care in diverse ways and it seems important for couples to evaluate and communicate about whether their particular arrangement is effective and acceptable to both partners.

Our findings also revealed other challenges that parents face in cultivating social relationships and social support. Smaldone and Ritholz (2011) showed that parents of YC-T1D often experience social isolation. Our findings also show that many parents experience deterioration in family relationships and friendships due to difficulty relating to, and relying on, them for support and caretaking. Parents in our study relied heavily on support from other parents with YC-T1D through support groups and diabetes online forums, although many note that these are not readily accessible.

Fourth, few studies have examined positive effects of T1D on young children or their parents. Our study identified several positive outcomes of dealing with the challenges of T1D in early childhood. Prior studies have explored protective factors and resilience in families with YC-T1D (Monaghan, Clary, Stern, Hilliard, & Streisand, 2015) but our study is the first to describe how the onus of daily T1D care itself may encourage protective factors such as enhanced self-control, social maturity and responsibility, and daily focus on health, which may yield general and T1D-specific benefits. Longitudinal studies examining this “benefit-finding” by YC-T1D and their parents are necessary, but this study suggests that cultivating these skills may be a fruitful point of intervention.

Finally, our study provides important information regarding parental experiences with broader systems such as school, the workplace, the health care system, and insurance. Our study revealed the difficulties that parents face in finding daycare and preschool settings that can provide acceptable care. Parents need help in navigating this system. The impact of these challenges on parents’ work lives reveals a need for support in career decision making. We also identified the importance of educating health care providers (pediatricians, specialists, and emergency medicine practitioners and staff) on the nuances of T1D. Most parents believe that health care systems do a poor job of normalizing, screening for, and providing resources to address mental health issues for their YC-T1D and themselves. Parents would greatly value a resource that equips health care professionals to seek and use mental health providers skilled in treating families with chronic medical conditions.

Qualitative interview or focus group studies that use small sample sizes and recruitment from single centers invite criticisms of external validity. Crowdsourced data have been obtained effectively in health, medical, and behavioral research (Brabham, 2013; Brabham et al., 2014), but it has not been used to develop a social support intervention by and for its target population. This novel data collection method engaged a larger, geographically diverse sample to obtain a holistic perspective of the complex challenges faced by parents of YC-T1D. The initial Parent Crowd sample had limited racial/ethnic diversity and self-selected to participate, thus clearly limiting the extent to which the findings can be generalized to the entire population of parents of YC-T1D. The sample reflected a preponderance of non-Hispanic Caucasians (89%), with above average status in income, occupation, and education and frequent Internet use. The crowdsourcing format required participants to submit written responses to open-ended questions, requiring Internet fluency that some parents may not possess, perhaps discouraging their participation. We recruited an additional sample of racial/ethnic minority parents to participate in a focus group. The perspectives of these participants consistently confirmed those obtained previously from the larger Parent Crowd sample. Despite the limited socioeconomic diversity, we achieved a broad geographic representation of parents from across the United States and internationally. Our sample was composed of primarily women (86.8%), although efforts to recruit more fathers increased the proportion of fathers by >50% relative to our early recruitment experience. Additionally, the majority of the parent participants had YC-T1D who used insulin pumps and continuous glucose monitors and also had a lower-than-average mean HbA1c (Miller et al., 2015). This limitation raises concerns about generalizability of findings across parents who have YC-T1D who are prescribed more conventional, less-intensive insulin regimens. Finally, about one-third of the participants had children who were between ages 6 and 10 years and were asked to report on their experiences before their child turned 6. For these parents, data were retrospective and may introduce response bias. Development of the Internet-based intervention will aggressively emphasize reaching racial and ethnic minorities and people with low health literacy so that this resource also accommodates their Internet fluency and meets their expressed needs via purposive sampling of these groups for Web site usability testing (i.e., the process of iteratively evaluating and modifying Web site content and functions via qualitative and quantitative feedback from representative users; Neilson, 2012). For example, the Web site could accommodate low health literacy users by using plain language at basic reading levels, offering audiovisual presentation of selected concepts to supplement the written word, providing a glossary of T1D terms in plain language, and by enabling users to submit questions to the research team or clinical experts.

Compiling a taxonomy of challenges faced by YC-T1D was the first major step in building and then testing an Internet coping resource designed by and for parents of YC-T1D. Having obtained a comprehensive characterization of the many challenges faced by these parents, the research team will now ensure that parents’ needs and perspectives drive translation of this knowledge into a functioning Web site. The overarching goal of this initiative is to build an Internet resource that provides parents of YC-T1D with the information, help, and support they want and need to raise safe, healthy, and well-adjusted children, while preserving their own well-being and quality of life. The research team will rely on these same Parent Crowd members to guide this continuing process by obtaining Parent Crowd perspectives on the planned resource so that parents of YC-T1D can quickly find what they need to meet the special challenges they face. The team has generated preliminary ideas about Web site structure and features, which are likely to include a social media function enabling users to connect with each other around shared concerns, an informational function providing expert summaries of treatment or research advances, and separate sections detailing problem-solving solutions contributed by parents and by health professionals for addressing commonly encountered barriers to optimal care for these children. Once the Web site is completed and functional, the researchers will initiate recruitment of a new set of parents of YC-T1D for a randomized controlled trial of the effects of Web site access and use on a wide range of pertinent child and parent outcomes.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary data can be found at Journal of Pediatric Psychology online.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Grant DP3DK10819801 awarded to the first and last authors as Multiple Principal Investigators.

Conflicts of interest: None declared.

Supplementary Material

References

- Archbold K. H., Pituch K. J., Panahi P., Chervin R. D. (2002). Symptoms of sleep disturbances among children at two general pediatric clinics. Journal of Pediatrics, 140, 97–102. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2002.119990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brabham D. C. (2013). Crowdsourcing. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press Essential Knowledge Series. [Google Scholar]

- Brabham D. C., Ribisi K. M., Kirchner T. R., Bernhardt J. M. (2014). Crowdsourcing applications for public health. American Journal of Public Health, 46, 179–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron F. J. (2015). The impact of diabetes on brain function in childhood and adolescence. Pediatric Clinics of North America, 62, 911–927. doi: 10.1016/J.pcl.2015.004.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cathey M., Gaylord N. (2004). Picky eating: A toddler's approach to mealtime. Pediatric Nursing, 30, 101.. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang J. L., Kirkman M. S., Laffel L. M., Peters A. L.; Type 1 Diabetes Sourcebook Authors. (2014). Type 1 diabetes through the life span: A position statement of the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care, 37, 2034–2054. doi: 10.2337/dc14-1140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole P. M., Dennis T. A., Smith‐Simon K. E., Cohen L. H. (2009). Preschoolers' emotion regulation strategy understanding: Relations with emotion socialization and child self‐regulation. Social Development, 18, 324–352. [Google Scholar]

- Dabelea D., Bell R. A., D’Agostino R. B., Imperatore G., Johanse J. M…, Waitzfelder B. (2007). Incidence of diabetes in youth in the United States. JAMA, 297, 2716–2724. doi:10.1001/jama.2014.3201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diabetes Control and Complications Trial Research Group. (1994). Effect of intensive treatment on the development and progression of long-term complications in adolescents with insulin dependent diabetes mellitus. Journal of Pediatrics, 125, 177–188. doi:10.1056/NEJM199309303291401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elo S., Kääriäinen M., Kanste O., Pölkki T., Utriainen K., Kyngäs H (2014). Qualitative content analysis. Sage Open. doi: 10.1177/2158244014522633. [Google Scholar]

- Grey M., Jaser S. S., Whittemore R., Jeon S., Lindemann E. (2011). Coping skills training for parents of children with type 1 diabetes: 12-month outcomes. Nursing Research, 60, 173–181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilliard M. E., Monaghan M., Cogen F. R., Streisand R. (2011). Parent stress and child behaviour among young children with type 1 diabetes. Child Care, Health and Development,3.224–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaser S. S., Whittemore R., Ambrosino J. M., Lindemann E., Grey M. (2009). Coping and psychosocial adjustment in mothers of young children with type 1 diabetes. Child Health Care, 38, 91–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger R. A., Casey M. A. (2009). Focus groups: A practical guide for applied research (4th ed.), Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln Y. S., Guba E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Lohan A., Morawska A., Mitchell A. (2015). A systematic review of parenting interventions for parents of children with type 1 diabetes. Child Care Health and Development, 41, 803–817. doi: 10.1111/cch.12278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monaghan M., Clary L., Stern A., Hilliard M., Streisand R. (2015). Protective factors in young children with type 1 diabetes. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 40, 878–887. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsv041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neergaard M. A., Olsen F., Andersen R. S., Sondergaard J. (2009). Qualitative description – the poor cousin of health research? BMC Medical Research Methodology, 9, 52. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-9-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neilson J. (2012). Usability 101: Introduction to usability. Retrieved from: https://www.nngroup.com/articles/usability-101-introduction-to-usability/

- Miller K. M., Foster N. C., Beck R. W., Bergenstal R. M., DuBose S. N., DiMeglio L. A…, Tamborlane W. V.; T1D Exchange Clinic Network (2015). Current state of type 1 diabetes treatment in the U.S.: updated data from the T1D Exchange clinic registry. Diabetes Care, 386, 971–978. doi: 10.2337/dc15-0078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pate R. R., O'Neill J. R., Mitchell J. (2010). Measurement of physical activity in preschool children. Medical Science in Sports and Exercise, 42, 508–512. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181cea116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute. (2016). About us. Retrieved from http://www.pcori.org/about-us

- Patterson C. C., Dahlquist G. G., Gyürüs E., Green A., Soltész G. (2009). Incidence trends for childhood type 1 diabetes in Europe during 1989–2003 and predicted new cases 2005–2020: A multicentre prospective registration study. Lancet, 373, 2027–2033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton S. R., Odar C., Midyett L. K., Clements M. A. (2014). Pilot study results for a novel behavior plus nutrition intervention for caregivers of young children with type 1 diabetes. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior, 46, 429–433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce J. S., Kozikowski K., Lee J., Wysocki T. (2017). Type 1 diabetes in very young children: A model of parent and child influences on management and outcomes. Pediatric Diabetes, 18, 17–25. [Epub ahead of print], doi: 10.1111/pedi.12351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverstein J., Klingensmith G., Copeland K., Plotnick L., Kaufman F., Laffel L., Deeb L, Grey M, Anderson B, Holzmeister L. A, Clark N. (2005). Care of children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care, 28, 186–212. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.1.186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smaldone A., Ritholz M. D. (2011). Perceptions of parenting children with type 1 diabetes diagnosed in early childhood. Journal of Pediatric Health Care, 25, 87–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stallwood L. (2005). Influence of caregiver stress and coping on glycemic control of young children with diabetes. Journal of Pediatric Health Care, 19, 293–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streisand R., Monaghan M. (2014). Young children with type 1 diabetes: Challenges, research, and future directions. Current Diabetes Reports, 14, 520.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan-Bolyai S., Bova C., Leung K., Trudeau A., Lee M., Gruppuso P. (2010). Social Support to Empower Parents (STEP): An intervention for parents of young children newly diagnosed with type 1 diabetes. The Diabetes Educator, 36, 88–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan-Bolyai S., Deatrick J., Gruppuso P., Tamborlane W., Grey M. (2003). Constant vigilance: Mothers' work parenting young children with type 1 diabetes. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 18, 21–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan-Bolyai S., Rosenberg R., Bayard M. (2006). Fathers' reflections on parenting young children with type 1 diabetes. The American Journal of Maternal/Child Nursing, 31, 24–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vehik K., Hamman R. F., Lezotte D., Norris J. M., Klingensmith G., Bloch C., Rewers M, Dabelea D (2007). Increasing incidence of type 1 diabetes in 0- to 17-year-old Colorado youth. Diabetes Care, 30, 503–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood J. R., Miller K. M., Maahs D. M., Beck R. W., DiMeglio L. A., Libman I. M., Woerner S. E. (2013). Most youth with type 1 diabetes in the T1D Exchange Clinic Registry do not meet American Diabetes Association or International Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Diabetes clinical guidelines. Diabetes Care, 36, 2035–2037. [PubMed: 23340893] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y. P., Thompson D., Aroian K. J., McQuaid E. L., Deatrick J. (2016). Commentary: Writing and evaluating qualitative research reports. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 41, 493–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.