Erlotinib plus gemcitabine has an acceptable safety and efficacy profile in pancreatic cancer. Interstitial lung disease remains a concern; patients should be assessed for risk factors prior to and during treatment.

Keywords: erlotinib, gemcitabine, pancreatic cancer, Japanese, surveillance

Abstract

Objective

Erlotinib plus gemcitabine is approved in Japan for the treatment of metastatic pancreatic cancer. The POLARIS surveillance study investigated safety (focusing on interstitial lung disease [ILD]) and efficacy of erlotinib plus gemcitabine in Japanese pancreatic cancer patients.

Methods

Patients receiving erlotinib plus gemcitabine for pancreatic cancer in Japan between July 2011 and August 2012 were enrolled. ILD-like events were independently confirmed by a review committee. Overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) were assessed, and risk factors for ILD occurrence were analyzed by multivariate Cox regression analysis.

Results

Safety data were available for 843 patients and efficacy data for 841. Adverse drug reactions were reported in 83.5% of patients, no new safety signals were identified. ILD events were confirmed by the review committee in 52 patients (6.2%), with two fatal cases (0.2%). Median time from initial erlotinib treatment to ILD events was 70.5 days. Of the 52 patients with ILD events, 86.5% improved or fully recovered from ILD (median time 24 days). Multivariate analysis identified previous or concurrent lung disease (hazard ratio [HR], 2.2; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.0–4.5; P = 0.0365) and ≥3 organs with metastases (HR, 4.2; 95% CI, 2.2–8.2; P < 0.0001) as potential ILD risk factors. Accumulated OS rate at 28 weeks was 68.2%, and median PFS was 92 days (95% CI, 86–101).

Conclusions

Erlotinib plus gemcitabine has an acceptable safety and efficacy profile in pancreatic cancer; however, patients should be assessed for previous/concurrent lung disease and metastatic burden, before and during treatment.

Introduction

Over 300 000 individuals were diagnosed with pancreatic cancer worldwide in 2012 (1). A total of 31 046 patients in Japan died from pancreatic cancer in 2012, making it the fourth leading cause of cancer death in Japan (1). Current recommended treatments for pancreatic cancer are gemcitabine regimens. A median overall survival (OS) of 5.7 months has been reported with single-agent gemcitabine in chemonaïve patients with pancreatic cancer (2). Several combinations of gemcitabine with cytotoxic agents and biological agents have been investigated; however, most have not significantly improved survival versus gemcitabine alone (3–16). Current recommended treatments for metastatic pancreatic cancer in Japan are FOLFIRINOX therapy (leucovorin, fluorouracil, irinotecan and oxaliplatin) and gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel therapy. However, in cases where treatment with FOLFIRINOX or gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel is not suitable, gemcitabine monotherapy, concomitant gemcitabine with erlotinib or S-1 chemotherapy are recommended (17–20).

Erlotinib is an epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine-kinase inhibitor approved as primarily first-line therapy in combination with gemcitabine (GE) for unresectable pancreatic cancer (21–24). GE was well tolerated in a Japanese phase II pancreatic cancer trial (22), and in the pivotal international phase III PA.3 trial, with mild-to-moderate rash and diarrhea being the most common adverse events (AEs) (21). In the Japanese pancreatic cancer study, interstitial lung disease (ILD), a heterogeneous group of parenchymal lung diseases, was reported in 8.5% of patients (9/106) and was highlighted as an adverse drug reaction (ADR) of particular concern (22). Consequently, a prospective observational study investigated erlotinib safety (focusing on ILD) and efficacy in Japanese patients with pancreatic cancer. A similar Japanese postmarketing surveillance study in non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients treated with erlotinib, which evaluated ILD, has also been completed (25). The POLARIS (POst-Launch All-patient-RegIstration Surveillance in erlotinib-treated pancreatic cancer patients) study investigated the occurrence of ILD and risk factors for onset of ILD, and evaluated other ADRs in all Japanese patients with pancreatic cancer treated with GE in Japan.

Methods

Surveillance study design and treatment

All Japanese patients with advanced pancreatic cancer treated with GE (gemcitabine 1000 mg/m2 weekly for 3 weeks, followed by a 1-week rest; erlotinib 100 mg orally, once daily) were enrolled from 1 July 2011 to 31 August 2012. A 28-week observation period was used, based on a median duration of erlotinib treatment of 102.5 days and peak ILD incidence at 187 days in the phase II trial (22). The surveillance period was 1 July 2011 to 31 December 2013, on which date case report forms were collected. The planned sample size was 800 patients, with planned surveillance duration of 42 months from the date of erlotinib approval in pancreatic cancer in Japan (1 July 2011). All patients provided informed consent and all appropriate ethical guidelines were followed during the study.

Safety assessments

Demographic and baseline data including gender, age, body mass index, tumor histology, disease stage, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (ECOG PS), smoking history, treatment status, metastases, medical history (including lung disorders, e.g. emphysema, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [COPD], lung infection and ILD), concomitant medications and history of chemotherapy were collected. Safety and efficacy data were collected at 8, 16 and 28 weeks after treatment initiation. AEs were graded using the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for AEs version 4.0 (Japanese version JCOG/JSCO edition, May 2009). Any AE possibly related to erlotinib was termed an ADR, with ADRs of particular interest for erlotinib also being identified (ILD, skin disorders, hepatic dysfunction, diarrhea, eye disorders, hemorrhage, microangiopathy, myocardial infarction/ischemic heart disease and cerebrovascular disorders). Patients with previous or current history of ILD were excluded as much as possible for safety measures. Patients with confirmed ILD events were treated, if required, using treatments such as steroid pulse therapy. ILD-like events were reported through Case Report Forms by a physician, based on periodic evaluation of chest imaging or CT scans. All reported ILD-like events were assessed by an independent review committee (IRC) of pulmonologists, chest radiologists, pancreatic oncologists and pathologists based on medical and pathologic findings, periodic evaluation of chest imaging or CT scans.

Efficacy assessments

Efficacy was evaluated by OS and physician-assessed progression-free survival (PFS), using Kaplan–Meier methodology. Disease progression was assessed according to treating physicians’ standard practices, without centralized independent assessment.

Statistical analyses

Assuming an ILD incidence of 8.5% (9/106 patients) (22), a planned sample size of 800 patients was established. This would detect background factors, with a risk ratio of the occurrence of ILD of ≥2 among patients with risk factors, and statistical difference with a P-value of <0.05.

The primary endpoint was the pattern of occurrence of ILD and risk factors for ILD. The outcome of ILD and time to ILD onset from the first erlotinib dose were also analyzed. The incidences of ILD and fatal ILD were expressed per 100 patient-weeks. Secondary endpoints included the pattern of other ADRs, and the overall safety and efficacy of erlotinib.

Multivariate Cox regression analysis with a stepwise model with forward selection method was conducted to determine ILD risk factors. Occurrence/nonoccurrence of ILD was the dependent variable. Exploratory variables included: gender, age, number of organs with metastases (<3 vs. ≥3), previous/concurrent lung disease, smoking history, ECOG PS and previous chemotherapy regimens. These baseline demographics were selected as ILD risk factors because they were previously reported as risk factors in Japan (26), or had a P-value of <0.05 in the univariate analyses. Additional multivariate analyses were conducted on risk factors identified to investigate two-factor interactions (statistical significance: P < 0.05). Statistical analyses used Statistical Analysis Software (version 9.1 and 9.3; SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

The safety population comprised all GE-treated patients with case report form data available. The efficacy population comprised the safety population, except those where gemcitabine therapy was not prescribed concomitantly at the time of this study.

Results

Patient population

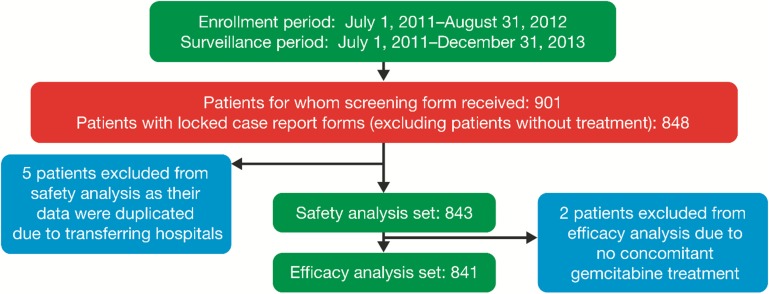

A total of 901 patients received enrollment forms between 1 July 2011 and 31 August 2012. Data from 848 patients with locked case report forms were obtained by the data cut-off of 31 December 2013. Safety data were available for 843 patients (5 patients were excluded because their data were duplicated due to hospital transfers). Efficacy data were available for 841 patients (2 more patients were excluded due to not receiving concomitant gemcitabine; Fig. 1). Regarding baseline characteristics (Table 1), 58.1% of patients enrolled were male, 44.1% had any smoking history, 70.5% had stage IVb cancer and 69.2% had an ECOG PS of 0. At the start of treatment, 50.7% were 65 years or older and 83.5% had metastases.

Figure 1.

Patient population distribution.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics (n = 843)

| Characteristic | Patients, n (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 490 (58.1) |

| Female | 353 (41.9) |

| Age at start of erlotinib treatment | |

| <65 years | 416 (49.3) |

| ≥65 years | 427 (50.7) |

| Histological type | |

| Adenocarcinoma | 631 (74.9) |

| Other | 12 (1.4) |

| Unknown | 200 (23.7) |

| Stage of pancreatic cancer | |

| Postoperative recurrence | 83 (9.8) |

| IVa | 154 (18.3) |

| IVb | 594 (70.5) |

| Other | 5 (0.6) |

| Unknown | 7 (0.8) |

| Site of primary tumor | |

| Head of pancreas | 348 (41.3) |

| Body of pancreas | 329 (39.0) |

| Tail of pancreas | 200 (23.7) |

| Other | 7 (0.8) |

| Metastases | |

| No | 137 (16.3) |

| Yes | 704 (83.5) |

| Unknown | 2 (0.2) |

| Site of metastatic foci | |

| Liver | 448 (63.6) |

| Peritoneal | 165 (23.4) |

| Lymph node | 263 (37.4) |

| Lung | 118 (16.8) |

| Bone | 28 (4.0) |

| Brain | 2 (0.3) |

| Other | 37 (5.3) |

| Previous or concurrent lung disease | |

| Lung infection: No | 805 (95.5) |

| Lung infection: Yes | 31 (3.7) |

| Unknown | 7 (0.8) |

| ILD: No | 833 (98.8) |

| ILD: Yes | 3 (0.4) |

| Unknown | 7 (0.8) |

| Lung emphysema or COPD: No | 816 (96.8) |

| Lung emphysema or COPD: Yes | 20 (2.4) |

| Unknown | 7 (0.8) |

| Asthma: No | 819 (97.2) |

| Asthma: Yes | 18 (2.1) |

| Unknown | 6 (0.7) |

| Tuberculosis: No | 826 (98.0) |

| Tuberculosis: Yes | 10 (1.2) |

| Unknown | 7 (0.8) |

| Smoking history | |

| No | 467 (55.4) |

| Yes | 372 (44.1) |

| Current smoker | 56 (15.0) |

| Past smoker | 313 (84.1) |

| Unknown | 3 (0.8) |

| Unknown | 4 (0.5) |

| ECOG PS | |

| 0 | 583 (69.2) |

| 1 | 251 (29.8) |

| 2 | 7 (0.8) |

| Unknown | 2 (0.2) |

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; ILD, interstitial lung disease.

Safety

Incidence of ADRs

ADRs were reported in 83.5% of patients (704 /843), the most common were skin disorders (69.9%), including rash (63.6%) and diarrhea (17.6%; Table 2). No new safety signals were identified. Most ADRs were mild in severity (grades 1–2; Table 3). Median time from initial erlotinib treatment to onset of an ADR was 8.5 days for rash, 10 days for liver disorders and 14 days for diarrhea. Most patients with these ADRs improved or recovered, and the majority were able to continue erlotinib treatment (data not shown).

Table 2.

Incidence of ADRs (n = 843)

| ADR, n (%) | All grades | Grade ≥3 |

|---|---|---|

| ILD (IRC confirmed) | 52 (6.1) | 20 (2.4) |

| Rash | 536 (63.6) | 34 (4.0) |

| Dry skin | 51 (6.0) | 1 (0.1) |

| Pruritus | 25 (3.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Paronychia | 90 (10.7) | 7 (0.8) |

| Liver disorders | 107 (12.7) | 33 (3.9) |

| Diarrhea | 148 (17.6) | 14 (1.7) |

| Eye disorders | 15 (1.8) | 0 (0.0) |

| Hemorrhage | 42 (5.0) | 15 (1.8) |

| Cerebrovascular disorder | 5 (0.6) | 3 (0.4) |

| Myocardial infarction | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Thrombotic microangiopathy | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Gastrointestinal perforation | 2 (0.2) | 1 (0.1) |

| Gastrointestinal ulcer | 9 (1.1) | 4 (0.5) |

| Acute renal failure | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) |

ADR, adverse drug reaction; IRC, independent review committee.

Table 3.

Incidence of prespecified ADRs by grade (n = 843)

| ADR, n (%) | Grade 1 | Grade 2 | Grade 3 | Grade 4 | Grade 5 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ILD (IRC confirmed) | 19 (2.3) | 13 (1.5) | 17 (2.0) | 1 (0.1) | 2 (0.2) | 52 (6.2) |

| Skin disorders | 309 (36.7) | 234 (27.8) | 44 (5.2) | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 589 (69.9) |

| Rash | 304 (36.1) | 197 (23.4) | 34 (4.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 536 (63.6) |

| Dry skin | 38 (4.5) | 12 (1.4) | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 51 (6.0) |

| Pruritus | 20 (2.4) | 5 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 25 (2.9) |

| Paronychia | 38 (4.5) | 45 (5.3) | 7 (0.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 90 (10.7) |

| Liver disorder | 41 (4.9) | 33 (3.9) | 31 (3.7) | 2 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 107 (12.7) |

| Diarrhea | 85 (10.8) | 49 (5.8) | 13 (1.5) | 2 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 148 (17.6) |

| Eye disorders | 12 (1.4) | 3 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 15 (1.8) |

| Hemorrhage | 23 (2.7) | 4 (0.5) | 9 (1.1) | 2 (0.2) | 4 (0.5) | 42 (5.0) |

| Thrombotic microangiopathy | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Myocardial infarction | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Cerebral disorders | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.2) | 5 (0.6) |

| Gastrointestinal perforation | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.2) |

| Gastrointestinal ulcer | 1 (0.1) | 4 (0.5) | 4 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 9 (1.1) |

| Renal failure | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) |

Interstitial lung disease

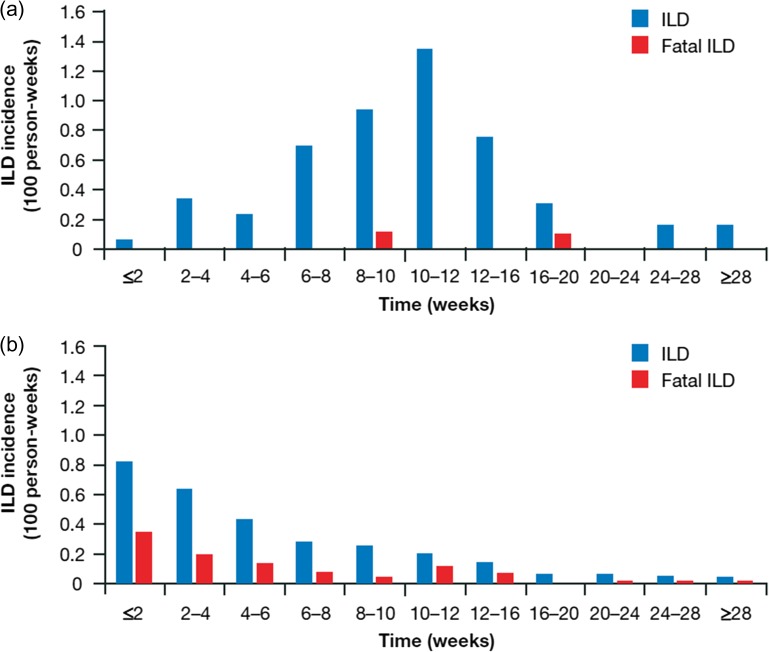

Reported ILD-like events (n = 57) included ILD (n = 50) and pneumonitis (n = 7). ILD events were confirmed by an independent review committee in 52 patients (6.2%), with two fatal (grade 5) ILD events (0.2% of the overall population, 3.8% of patients with a confirmed ILD event). Grade ≥3 ILD events were confirmed in 20 patients (2.4% of the safety population). In the 52 patients with confirmed ILD events, the median time from initial erlotinib treatment to the onset of ILD events was 70.5 days (range 13.0–212.0). Outcomes of ILD events were: 23 patients (44.2%) recovered; 22 (42.3%) improved; 3 (5.7%) did not recover; 1 patient (1.9%) had a sequela and the outcome was unknown for 1 patient (1.9%). Of these patients, 86.5% improved or fully recovered from ILD in a median time of 24 days. A total of 92.3% of patients with confirmed ILD events discontinued erlotinib treatment. The highest incidence rate per 100 patient-weeks for ILD event onset was 10–12 weeks after starting treatment, with an incidence per 100 patient-weeks of 1.4 (Fig. 2a).

Figure 2.

(a) Time to onset and outcome of ILD in the pancreatic POLARIS study. (b) Time to onset and outcome of ILD in the non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) POLARSTAR study (25).

Risk factors for ILD onset

In the univariate analysis, smoking history (P = 0.0298) and ≥3 organs with metastases (P < 0.0001) were identified as significant risk factors for developing ILD (Table 4). In the multivariate analysis, previous or concurrent lung disease (hazard ratio [HR], 2.2, 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.0–4.5; P = 0.0365) and ≥3 organs with metastases (HR, 4.2, 95% CI, 2.2–8.2; P < 0.0001) were identified as significant risk factors for onset of ILD (Table 4).

Table 4.

Univariate and multivariate analysis of risk factors for developing ILD

| Exploratory variables Criterion variable Evaluation variable |

Total number of patients | Incidence of ILD, % | Univariate analysisa | Multivariate analysisb | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | P-value | HR | 95% CI | P-value | |||

| Overall | 829 | 6.3 | ||||||

| Gender | 1.3 | 0.7–2.2 | 0.4033 | |||||

| Female | 346 | 5.5 | ||||||

| Male | 483 | 6.8 | ||||||

| Age, years | ||||||||

| <75 | 722 | 5.7 | 1.8 | 0.9–3.6 | 0.0719 | |||

| ≥75 | 107 | 10.3 | ||||||

| Previous or concurrent lung disease | ||||||||

| No | 746 | 5.8 | 1.9 | 0.9–3.9 | 0.0849 | 2.2 | 1.0–4.5 | 0.0365 |

| Yes | 83 | 10.8 | ||||||

| Smoking history | ||||||||

| No | 460 | 4.6 | 1.8 | 1.1–3.2 | 0.0298 | |||

| Yes | 369 | 8.4 | ||||||

| ECOG PS | ||||||||

| 0 | 572 | 6.1 | 1.5 | 0.9–2.7 | 0.1495 | |||

| ≥1 | 257 | 6.6 | ||||||

| Number of chemotherapy regimens for primary disease: two categories | ||||||||

| ≥1 | 162 | 2.5 | 2.6 | 0.9–7.2 | 0.0667 | |||

| 0 | 667 | 7.2 | ||||||

| Number of affected organs: two categories | ||||||||

| 0 or ≤2 | 748 | 5.3 | 3.9 | 2.1–7.5 | <0.0001 | 4.2 | 2.2–8.2 | <0.0001 |

| ≥3 | 81 | 14.8 | ||||||

CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio.

aFourteen patients for whom not all exploratory variable data were obtained were excluded from the univariate and multivariate analyses.

bExploratory variables included: gender, age, number of organs affected by metastases (categorical variable <3 vs. ≥3), previous/concurrent lung disease, smoking history, ECOG PS and previous chemotherapy regimens. These baseline demographics were selected as ILD risk factors because they were previously reported as ILD risk factors in Japan (26) or were statistically different with a P-value of <0.05 in univariate analyses. 75 years was selected as the exploratory variable for age because it had a higher univariate HR compared with 65 years.

Efficacy

Accumulated survival rates at 8, 16 and 28 weeks were 95.3%, 85.0% and 68.2%, respectively. Physician-assessed median PFS, as evaluated by each site physician, was 92 days (3.0 months; 95% CI, 86–101 days). Subgroup analysis, as shown in Table 5, demonstrated that patients without additional affected organs had longer median physician-assessed PFS (176 days) than those with 1–2 organs affected (87 days) or ≥3 organs affected (63 days), and patients with grade 2 rash had longer physician-assessed median PFS (125 days) than those with grade 0–1 rash (85 days). Accumulated PFS rates at 8, 16 and 28 weeks were 70.9%, 42.7% and 23.4%, respectively.

Table 5.

Physician-assessed median PFS by subgroup

| Subgroup | Median PFS (95% CI), days |

|---|---|

| Overall | 92 (86–101) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 87 (79–99) |

| Female | 100 (90–115) |

| Age, years | |

| <65 | 97 (87–113) |

| ≥65 | 89 (80–100) |

| Metastatic sitesa | |

| Liver | 69 (63–79) |

| Peritoneum | 99 (78–114) |

| Lymph nodes | 92 (79–106) |

| Lung | 91 (69–105) |

| Number of additional affected organs | |

| 0 | 176 (148–213) |

| <2 | 87 (79–94) |

| ≥3 | 63 (53–89) |

| Smoking history | |

| Yes | 91 (85–97) |

| No | 92 (84–105) |

| Rash | |

| Grade 0–1 | 85 (76–91) |

| Grade 2 | 125 (110–152) |

PFS, progression-free survival.

aPatients may have multiple metastases.

Discussion

Final data from the POLARIS surveillance study confirm that the GE regimen has an acceptable safety and efficacy profile in Japanese patients with pancreatic cancer. Compared with a previous Japanese phase II pancreatic cancer study, no new risk information for ILD onset was identified here (22). In the phase II study, rash was the most common ADR, seen in 93.4% of patients; ILD occurred in 8.5% of patients, all cases were grade ≤3 and all patients improved or fully recovered (22).

In POLARIS, the ILD incidence was 6.2%, with an overall mortality rate of 0.2% (n = 2), which was 3.8% among patients with confirmed ILD. This incidence rate of ILD events was similar to that in the Japanese phase II pancreatic cancer study, reporting an incidence of 8.5% with no fatal cases (22). This is similar to all grades of ILD events reported in 429 patients (4.3%), grade ≥3 ILD events reported in 257 patients (2.6%), and grade 5 ILD events experienced by 153 patients (1.5%) in the Japanese postmarketing POLARSTAR surveillance study in 9 909 NSCLC patients (25). A surveillance study in Japanese patients with pancreatic cancer treated with gemcitabine alone (n = 855) demonstrated an incidence of ILD of 0.7% (n = 6), suggesting that the combination with erlotinib may result in a higher incidence of ILD (27). Occurrence of ILD in patients with pancreatic cancer was most common at 10–12 weeks following the start of GE treatment in POLARIS. This was in contrast to data from NSCLC POLARSTAR patients, where ILD was most commonly seen within 2 weeks of commencing erlotinib (incidence rate per 100 patient-weeks of 0.8; Fig. 2b) (25). This difference concerning ILD incidence rate between NSCLC and pancreatic cancer may be due to a cytotoxic reaction associated with combination therapy in a dose-dependent manner or due to drug induced activation of certain immune cells linked with development of pulmonary disorders (28–30). Alternatively, this difference in time of onset of ILD may be due to differences in tumor characteristics.

In the NSCLC POLARSTAR study, of the confirmed cases of ILD, 75 (17.5%) patients fully recovered, 154 (35.9%) patients improved, 32 (7.5%) patients did not recover, 5 (1.2%) patients had sequelae, 153 (35.7%) patients died and 10 (2.3%) patients had unknown outcomes (25). Although the ILD incidence rate in POLARIS exceeded that in the final POLARSTAR analysis, the ILD mortality rate was lower in patients with pancreatic cancer, perhaps reflecting the lower incidence of confounding lung disease or reduced normal lung area on computed tomography scan in patients with pancreatic cancer. In POLARIS, 86.5% of patients with an ILD event improved or fully recovered from ILD, compared with 53.4% of patients with ILD from POLARSTAR. This again may be due to differences in tumor characteristics or confounding lung disease that may affect the severity of ILD.

The two risk factors for ILD onset identified by the Cox regression multivariate analysis in POLARIS were previous or concurrent lung disease and ≥3 organs with metastases. However, previous/concurrent ILD and previous/concurrent emphysema/COPD, which were included in the exploratory variables for the NSCLC POLARSTAR study, were excluded from the exploratory variables in POLARIS and tabulated as ‘lung disease’ because few patients with those variables received erlotinib on the basis of erlotinib safety measures. Therefore, the authors suggest administering erlotinib to patients with the following risk factors only after careful consideration and with thorough observation of patient status: concurrent or previous ILD, concurrent or previous emphysema or COPD and concurrent or previous pulmonary infection.

In a study reviewing records of patients with NSCLC or pancreatic cancer treated with gemcitabine alone, pre-existing pulmonary fibrosis and prior thoracic radiotherapy were identified as risk factors for developing ILD, suggesting prior lung conditions may be a risk factor independent of erlotinib treatment (26). After reviewing the POLARIS data, the ILD review committee recommended that patients with pancreatic cancer should be evaluated for the risk factors identified here prior to beginning GE treatment. During GE treatment, it is necessary to continually monitor for early symptoms of ILD (dry cough, dyspnea, pyrexia) and perform regular chest computed tomography scans, as ILD onset can occur throughout the treatment course. If ILD symptoms occur, discontinuation of GE is recommended.

Erlotinib was generally well tolerated in POLARIS, with rash and diarrhea being the most frequently observed ADRs, which is consistent with phase III trials of GE for pancreatic cancer. These events were predominantly grades 1–2, manageable and their frequency was comparable to that reported in the Japanese phase II pancreatic cancer clinical trial of erlotinib (22).

Efficacy in terms of physician-assessed median PFS in POLARIS (3.0 months) was similar to previously reported studies of GE in pancreatic cancer. The PA.3 study reported median PFS of 3.8 months with GE versus 3.6 months with gemcitabine plus placebo, while the AViTA study reported median PFS of 3.6 months with GE (21,23). In a Japanese population, a phase II pancreatic cancer study demonstrated a median PFS of 3.5 months with GE (22). Subgroup analysis in POLARIS suggested that patients with higher grade of rash may benefit more in terms of physician-assessed median PFS than those who do not experience rash. This is consistent with results from the global studies AViTA and PA.3, and the Japanese phase II pancreatic cancer study, showing that rash correlates with improved efficacy outcomes with GE (21–23).

Limitations to consider include the single-arm nature of this observational trial without a control group. Unlike a clinical trial, this analysis was regulated to have a maximum observation period of 28 weeks and could not estimate median OS despite the existence of accumulated survival rate. Additionally, there was a lack of specific patient selection criteria for enrollment, including no specification regarding history of ILD, which could potentially affect the ILD risk factor analysis.

The POLARIS postmarketing surveillance study showed that GE has an acceptable safety and efficacy profile in Japanese patients with pancreatic cancer. No new safety signals were detected and the risk/benefit balance of GE was considered favorable, suggesting that GE is a generally well tolerated treatment option for Japanese patients with pancreatic cancer. However, patients should be carefully monitored for the risk factors identified in this surveillance study, both before and during treatment.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all participating physicians and registered patients, the ILD review committee (Hiroaki Arakawa, Masahito Ebina, Yuh Fukuda, Yoshikazu Inoue, Takeshi Johkoh, Terufumi Kato, Masahiko Kusumoto, Kazuyoshi Kuwano, Yoshinobu Saito, Fumikazu Sakai, Hiroyuki Taniguchi) and Masahiko Ando for their helpful advice.

Funding

This study was sponsored by Chugai Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd. Third-party writing assistance was provided under the direction of the authors by Joanna Musgrove, MRes of Gardiner-Caldwell Communications, funded by Chugai Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd.

Conflict of interest statement

All authors report nonfinancial support from Gardiner-Caldwell Communications during this work. Dr Furuse reports personal fees from Chugai during the study; grants from Chugai and Eli Lilly outside this work. Dr Gemma reports personal fees from Chugai during the study. Dr Ichikawa reports personal fees from Chugai during the study; grants and personal fees from Taiho Pharmaceutical, Takeda Pharmaceutical, Merck Serono, Chugai, Ono Pharmaceutical, Shionogi and Co., Daiichi Sankyo, grants from Eisai, personal fees from Nippon Kayaku, Sawai Pharmaceutical, Zeria Pharmaceutical, outside this work. Dr Okusaka reports personal fees from Chugai during the study; personal fees from Eli Lilly, grants and personal fees from Chugai, Pfizer, Ono Pharmaceutical, Novartis, Yakuruto Honsha, Sceti Medical Labo, OncoTherapy Science Inc., Kyowa Hakko Kirin Jana Inc., Taiho Pharmaceutical, Eisai, AstraZeneca, Dainippon Sumitomo, Merck Serono, Kowa, Nippon Boehringer Ingelheim, Bayer Yakuhin, and grants from Takeda Bio Development Center, Otsuka Pharmaceutical and Shizuoka Industry, outside this work. Mr Ishii and Mr Seki are employees of Chugai.

References

- 1. World Health Organization , GLOBOCAN 2012 (http: //globocan.iarc.fr/). Last accessed 15 February 2017.

- 2. Burris HA III, Moore MJ, Andersen J, et al. . Improvements in survival and clinical benefit with gemcitabine as first-line therapy for patients with advanced pancreas cancer: a randomized trial. J Clin Oncol 1997;15:2403–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Berlin JD, Catalano P, Thomas JP, et al. . Phase III study of gemcitabine in combination with fluorouracil versus gemcitabine alone in patients with advanced pancreatic carcinoma: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Trial E2297. J Clin Oncol 2002;20:3270–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Colucci G, Giuliani F, Gebbia V, et al. . Gemcitabine alone or with cisplatin for the treatment of patients with locally advanced and/or metastatic pancreatic carcinoma: a prospective, randomized phase III study of the Gruppo Oncologia dell'Italia Meridionale. Cancer 2002;94:902–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rocha Lima CM, Green MR, Rotche R, et al. . Irinotecan plus gemcitabine results in no survival advantage compared with gemcitabine monotherapy in patients with locally advanced or metastatic pancreatic cancer despite increased tumor response rate. J Clin Oncol 2004;22:3776–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Louvet C, Labianca R, Hammel P, et al. . Gemcitabine in combination with oxaliplatin compared with gemcitabine alone in locally advanced or metastatic pancreatic cancer: results of a GERCOR and GISCAD phase III trial. J Clin Oncol 2005;23:3509–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Oettle H, Richards D, Ramanathan RK, et al. . A phase III trial of pemetrexed plus gemcitabine versus gemcitabine in patients with unresectable or metastatic pancreatic cancer. Ann Oncol 2005;16:1639–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Abou-Alfa GK, Letourneau R, Harker G, et al. . Randomized phase III study of exatecan and gemcitabine compared with gemcitabine alone in untreated advanced pancreatic cancer. J Clin Oncol 2006;24:4441–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Heinemann V, Quietzsch D, Gieseler F, et al. . Randomized phase III trial of gemcitabine plus cisplatin compared with gemcitabine alone in advanced pancreatic cancer. J Clin Oncol 2006;24:3946–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Stathopoulos GP, Syrigos K, Aravantinos G, et al. . A multicenter phase III trial comparing irinotecan gemcitabine (IG) with gemcitabine (G) monotherapy as first-line treatment in patients with locally advanced or metastatic pancreatic cancer. Br J Cancer 2006;95:587–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Herrmann R, Bodoky G, Ruhstaller T, et al. . Gemcitabine plus capecitabine compared with gemcitabine alone in advanced pancreatic cancer: a randomized, multicenter, phase III trial of the Swiss Group for Clinical Cancer Research and the Central European Cooperative Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol 2007;25:2212–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Van Cutsem E, van de Velde H, Karasek P, et al. . Phase III trial of gemcitabine plus tipifarnib compared with gemcitabine plus placebo in advanced pancreatic cancer. J Clin Oncol 2004;22:1430–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bramhall SR, Rosemurgy A, Brown PD, et al. . Marimastat as first-line therapy for patients with unresectable pancreatic cancer: a randomized trial. J Clin Oncol 2001;19:3447–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Moore M, Hamm J, Dancey J, et al. . Comparison of gemcitabine versus the matrix metalloproteinase inhibitor BAY 12-9566 in patients with advanced or metastatic adenocarcinoma of the pancreas: a phase III trial of the National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group. J Clin Oncol 2003;21:3296–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Philip PA, Benedetti J, Fenoglio-Preiser C, et al. . Phase III study of gemcitabine [G] plus cetuximab [C] versus gemcitabine in patients [pts] with locally advanced or metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma [Pca]: SWOG S0205 study. J Clin Oncol 2007;25:199s Abstract LBA4509. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kindler HL, Niedzwiecki D, Hollis E, et al. . A double-blind, placebo controlled, randomized phase III trial of gemcitabine (G) plus bevacizumab (B) versus gemcitabine plus placebo (P) in patients (pts) with advanced pancreatic cancer (PC): a preliminary analysis of Cancer and Leukemia Group B (CALGB). J Clin Oncol 2007;25:199s Abstract 4508. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Conroy T, Destine F, Chou M, et al. . FOLFIRINOX versus gemcitabine for metastatic pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med 2011;364:1817–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Von Hoff DD, Ervin T, Arena FP, et al. . Increased survival in pancreatic cancer with nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine. N Engl J Med 2013;369:1691–703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Burris HA, Moore MJ, Anderson J, et al. . Improvements in survival and clinical benefit with gemcitabine as first-line therapy for patients with advanced pancreas cancer: a randomized trial. J Clin Oncol 1997;16:2403–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ueno H, Ioka T, Ikeda M, et al. . Randomised phase III study of gemcitabine alone in patients with locally advanced and metastatic pancreatic cancer in Japan and Taiwan: GEST study. J Clin Oncol 2013;31:1640–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Moore MJ, Goldstein D, Hamm J, et al. . Erlotinib plus gemcitabine compared with gemcitabine alone in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer: a phase III trial of the National Cancer Institute of Canada. J Clin Oncol 2007;25:1960–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Okusaka T, Furuse J, Funakoshi A, et al. . Phase II study of erlotinib plus gemcitabine in Japanese patients with unresectable pancreatic cancer. Cancer Sci 2011;102:425–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Van Cutsem E, Vervenne WL, Bennouna J, et al. . Phase III trial of bevacizumab in combination with gemcitabine and erlotinib in patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:2231–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Nakai Y, Isayama H, Sasaki T, et al. . A multicentre randomised phase II trial of gemcitabine alone vs gemcitabine and S-1 combination therapy in advanced pancreatic cancer: GEMSAP study. Br J Cancer 2012;106:1934–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gemma A, Kudoh A, Ando M, et al. . Final safety and efficacy of erlotinib in the phase 4 POLARSTAR surveillance study of 10708 Japanese patients with non-small-cell lung cancer. Cancer Sci 2014;105:1584–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Umemura S, Yamane H, Suwaki T, et al. . Interstitial lung disease associated with gemcitabine treatment in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer and pancreatic cancer. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2011;137:1469–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ioka T, Katayama K, Tanaka S, et al. . Safety and effectiveness of gemcitabine in 855 patients with pancreatic cancer under Japanese clinical practice based on post-marketing surveillance in Japan. Jpn J Clin Oncol 2013;43:139–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Limer AH, Rosenow EC. Drug-induced pulmonary disease In: Murray J, Nadel J, Mason R, Boushey A, editors. Textbook of Respiratory Medicine. Philadelphia: Saunders, 2000;1971–94. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Naba T, Tanaka K, Hoshino T, et al. . Suppression of expression of heat shock protein 70 by gefitinib and its contribution to pulmonary fibrosis. PLoS One 2011;6:e27296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Tanaka K, Tanaka Y, Namba T, et al. . Heat shock protein 70 protects against bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis in mice. Biochem Pharmacol 2010;80:920–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]