Follicular lymphoma is the most common indolent lymphoma worldwide. Rituximab plus bendamustine (R‐B) has been shown to improve outcome and reduce toxicity compared with rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and prednisone (R‐CHOP) in follicular lymphoma; however, in clinical practice in many centers, R‐CHOP is still the preferred treatment. This article reports the results of a study that assessed patients with follicular lymphoma grade 3A treated with either RCHOP or R‐B in five European cancer centers.

Keywords: Follicular lymphoma, grade 3A, Bendamustine, Rituximab

Abstract

Background.

Rituximab plus bendamustine (R‐B) has been demonstrated to improve outcomes and reduce toxicity compared with rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and prednisone (R‐CHOP) in follicular lymphoma (FL). Nevertheless, in clinical practice, many centers still prefer R‐CHOP to R‐B in patients with FL grade 3A (FL3A). Therefore, we retrospectively assessed patients with FL3A treated with either R‐CHOP or R‐B in five European cancer centers and compared their outcomes.

Materials and Methods.

We retrospectively assessed 132 patients affected by FL grade 3A treated with either R‐B or R‐CHOP in the first line and evaluated outcome and toxicity according to the type of treatment. This study included 101 patients who were a subgroup of a previously published cohort.

Results.

R‐B was less toxic and achieved a similar percentage of complete remissions compared with R‐CHOP (97% vs. 96%, p = .3). During follow‐up, 10 (16%) patients relapsed after R‐B and 29 (41%) after R‐CHOP (p = .001), leading to a median progression‐free survival (PFS) of 15 versus 11.7 years, respectively (p = .03). Furthermore, R‐B overcame the negative prognostic impact of BCL2 expression (15 vs. 4.8 years; p = .001). However, median overall survival was similar between both groups (not reached for both; p = .8).

Conclusion.

R‐B as a first‐line treatment of FL3A is better tolerated than R‐CHOP and seems to induce more profound responses, leading to a significantly lower relapse rate and prolonged PFS. Therefore, R‐B is a valid treatment option for FL grade 3A.

Implications for Practice.

Rituximab plus bendamustine (R‐B) has shown to be less toxic and more effective than rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and prednisone (R‐CHOP) in follicular lymphoma grade 3A. Although both regimens can induce a complete remission in >95% of patients, relapses occur more frequently after R‐CHOP than R‐B, leading to a significantly longer progression‐free survival in the latter. R‐B is also able to overcome the impact of negative prognosticators, such as BCL2 expression. However, because of the indolent course of this disease and efficient salvage treatments, overall survival was similar in both treatment groups. Therefore, R‐B is a valid treatment option in this patient setting.

Introduction

Follicular lymphoma (FL) is the most common indolent lymphoma worldwide [1], [2]. A histologic grading was first proposed by Mann and Berard [3] and subsequently adopted by the World Health Organization (WHO) [4], [5]. It is based on the number of admixed centroblasts within the neoplastic follicles and recognizes three cytological grades [3], [5]. FL grade 3 (FL3) is further subdivided into 3A (FL3A) and 3B (FL3B) subtypes based on the presence of some residual centrocytes in FL3A. Molecular studies have suggested that FL grades 1, 2, and 3A represent a clinical and biological continuum, whereas FL3B is more like de novo diffuse large B‐cell lymphoma [6], [7], [8].

FL grades 1 and 2 are characterized by an indolent clinical course [1], whereas, in the prerituximab era, FL3 commonly led to worse overall survival [9], [10], [11], [12]. Some authors suggested that anthracycline‐containing chemotherapy might improve outcomes for this more aggressive subgroup [9], [10], [11], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17], [18], [19]. After the introduction of rituximab into clinical routine, immunochemotherapy regimens, such as rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (R‐CHOP) and rituximab, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and prednisolone (R‐CVP), were considered the standard of care for first‐line treatment of patients with symptomatic advanced FL [20], [21], [22]. Recently, two trials demonstrated the superiority of rituximab and bendamustine (R‐B) to R‐CHOP in terms of outcome and toxicity, leading to improved survival [23], [24]. In both trials, the positive impact of R‐B was independent from other prognosticators such as age, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels, and the follicular lymphoma international prognostic index (FLIPI). Moreover, these positive results were confirmed in a real‐life analysis [25]. However, until now, no published data comparing R‐CHOP with R‐B as a first‐line treatment in patients affected by FL3A were available. Therefore, despite the so‐far promising results in favor of R‐B, in clinical practice many centers still prefer R‐CHOP to R‐B in patients with FL3A, relying on the published evidence. To shed some light on this open question, we retrospectively assessed patients with FL3A treated with either R‐CHOP or R‐B in five European cancer centers and compared their outcomes.

Materials and Methods

Patients

We retrospectively assessed 132 patients affected by FL grade 3A treated in one Austrian and four Italian cancer centers from November 1997 to February 2016. The data presented herein were a subgroup analysis of a previously published cohort [25] and included only those patients who were affected by FL grade 3A [25]. To increase the statistical power, 31 consecutive patients treated in Naples who met the inclusion criteria of the primary analysis were added. Histologic diagnosis was performed according to the international diagnostic criteria by an expert pathologist of each participating cancer center [4], [5], [26], [27].

BCL2 and BCL6 protein expression was evaluated in all patients using a monoclonal anti‐BCL2 antibody (Clone 124, Dakocytomation, Milan, Italy), an anti‐BCL6 antibody (Clone PG‐B6p, Dakocytomation, Milan, Italy), and standard immunohistochemical methods. The formalin‐fixed, paraffin‐embedded tissue slides underwent deparaffinization and heat‐induced antigen retrieval techniques. An endogenous biotin‐blocking kit (Ventana, Oro Valley, AZ) was used to decrease background staining. After antigen retrieval and primary antibody incubation, the reaction was completed in a Ventana ES instrument using a diaminobenzidine immunoperoxidase detection kit (Ventana, Oro Valley, AZ). Tumors were considered positive if more than 20% of tumor cells expressed BCL2 or BCL6 protein [28].

Data collection and analysis was approved by the local ethical committee as previously described [25]. Because of the retrospective and anonymous data collection, informed consent was not necessary.

Treatment Plan

All patients underwent immunochemotherapy, consisting of rituximab in association with either bendamustine or cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (CHOP), according to the treatment guidelines of the participating center. The standard rituximab dose was the same for both groups: 375 mg/m2 on day 1 of each cycle. Bendamustine was delivered at the same dose as in the prospective trials (90 mg/m2) on days 1 and 2 every 4 weeks for up to six cycles [23], [24]. CHOP was administered at standard doses every 3 weeks for a maximum of six cycles [23], [24].

No maintenance or consolidation treatment was given. The use of granulocyte‐colony stimulating factors was allowed at the investigator's discretion.

All patients were evaluated for response to therapy according to international criteria [29], [30], and toxicity was classified according to the National Cancer Institute's Common Toxicity Criteria. Treatment response was assessed about 1 month after completion of the treatment by a full physical examination, blood testing, bone marrow aspirate, and biopsy in case of bone marrow involvement at diagnosis, as well as imaging studies with computed tomography. Follow‐up visits were performed every 3–6 months for 5 years and annually thereafter in all participating centers.

Statistical Analysis

A chi‐square test was performed to assess the significance of differences between categorical variables. Overall survival (OS) and progression‐free survival (PFS) were plotted as curves using the Kaplan‐Meier method and were defined according to previously published criteria [29], [30]. A log‐rank test was employed to assess the impact on survival of categorical variables. Statistical analyses were performed with MedCalc (version 11.0; MedCalc Software Acacialaan, Ostend, Belgium) software and the GraphPad Prism (version 5.0; GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA) package. The limit of significance for all analyses was defined as p < .05.

Results

Clinical Characteristics at Time of Diagnosis

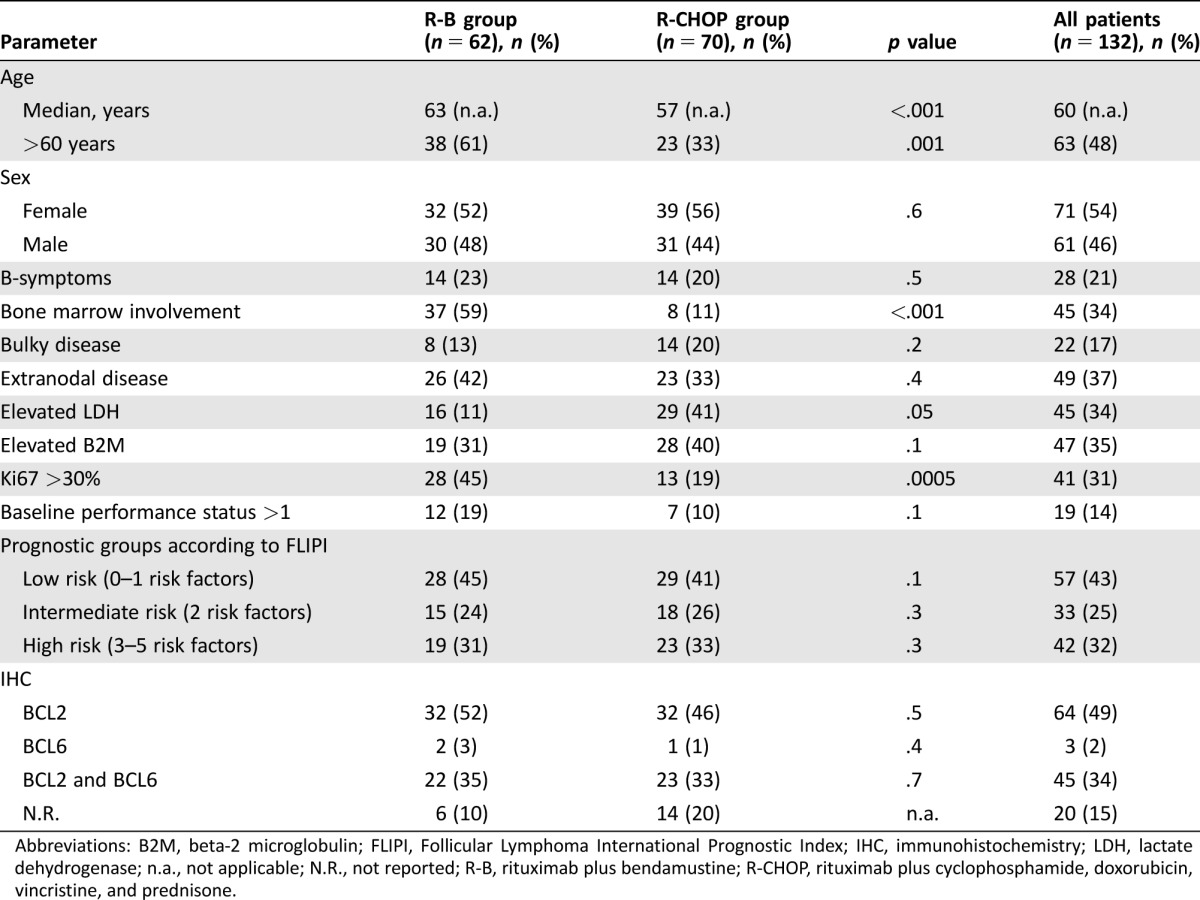

Clinical features of the two different treatment groups are summarized in Table 1. In the R‐B group, the median age at time of diagnosis was 63 years (range 45–87 years) compared with 57 years (range 29–80 years) in the R‐CHOP cohort (p < .001). Other negative prognosticators, such as bone marrow involvement and Ki67 >30%, were significantly more often registered in the R‐B group than in the R‐CHOP group (59% vs. 11%; p < .001 and 45% vs. 19%; p < .001). No significant differences in distribution of the patients among the FLIPI [31] risk groups were recorded. BCL2 expression, either alone or coexpressed with BCL6, was predominantly observed by immunohistochemistry (52% vs. 46%; p = .5 and 35% vs. 33%; p = .7).

Table 1. Patient characteristics.

Abbreviations: B2M, beta‐2 microglobulin; FLIPI, Follicular Lymphoma International Prognostic Index; IHC, immunohistochemistry; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; n.a., not applicable; N.R., not reported; R‐B, rituximab plus bendamustine; R‐CHOP, rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone.

Treatment and Response

Sixty‐two patients were treated with R‐B and 70 with R‐CHOP. Overall, 353 cycles of R‐B (median 5 cycles; range 2–6) and 429 of R‐CHOP (median 6 cycles; range 4–8) were delivered. Dose reduction was necessary in 1% and 12% of patients who underwent R‐B and R‐CHOP, respectively (p = .004). Overall response rate (ORR) was 97% for the R‐B treatment group and 96% for the standard treatment group (p = .3). The percentages of complete remission (CR) were similar for both groups: 77% after R‐B and 80% after R‐CHOP (p = .4). Also, the rates of partial remissions (15% vs. 10%; p = .9) and stable disease (5% vs. 6%; p = .6) were comparable. Progressive disease was encountered in 3% and 4% of patients who underwent R‐B and R‐CHOP, respectively.

Toxicity was mainly hematological and significantly less frequent in the R‐B group. Grade 1 or 2 neutropenia occurred in 6% of patients treated with R‐B versus 30% in the R‐CHOP group (p < .001) and grade 3 or 4 toxicity in 10% versus 26% (p < 0.01). This contributed to a higher incidence of infections in the R‐CHOP arm (35% vs. 5%; p < .006). Anemia of grade 1 or 2 was recorded in 2% versus 13% (p = .01) and of grade 3 or 4 in 4% vs. 14% (p = .02). Grade 1 or 2 thrombocytopenia occurred in both groups (5% vs. 16%; p = .04), and no grade 3 or 4 events were registered in the R‐B group, compared with 11% in patients treated with R‐CHOP (p = .005). Also, nonhematological toxicity was more frequent in the R‐CHOP group. Alopecia occurred in all R‐CHOP treated patients (100%) but not in the R‐B group. Peripheral neuropathy (1% vs. 45%; p < .001) and drug‐associated erythematous skin reaction (urticaria, rash; 3% vs. 15%; p = .005) were significantly less common in the R‐B group as well. Overall, dose reduction of immunochemotherapy was necessary in 12% of patients treated with R‐CHOP compared with only 1% in the R‐B group (p = .004). Late toxicity in terms of secondary malignancies occurred in two patients treated with R‐B compared with nine in the R‐CHOP group (3% vs. 13%; p = .04). Tumors in the former group consisted of one myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) and one breast cancer and in the latter of two acute myeloid leukemias, one MDS, two melanomas, one colon cancer, two prostatic cancers, and one pancreatic cancer.

Follow‐up

The median follow‐up was 14.8 years (range 6 months to 20 years) and 15.2 years (range 5 months to 19 years) for the R‐CHOP and R‐B groups, respectively. During the observation period, 10 (16%) R‐B‐treated patients relapsed compared with 29 (41%) in the R‐CHOP group (p = .001). In the former, 6 patients underwent a salvage treatment; in the latter, 23. Four patients (6%) died in the R‐B group and 14 (20%) in the R‐CHOP group (p = .009). The cause of death was late toxicity in nine patients, one in the R‐B group and eight in the R‐CHOP group (p = .02). The remaining nine were lymphoma‐related (3 in R‐B vs. 6 in R‐CHOP; p = .8).

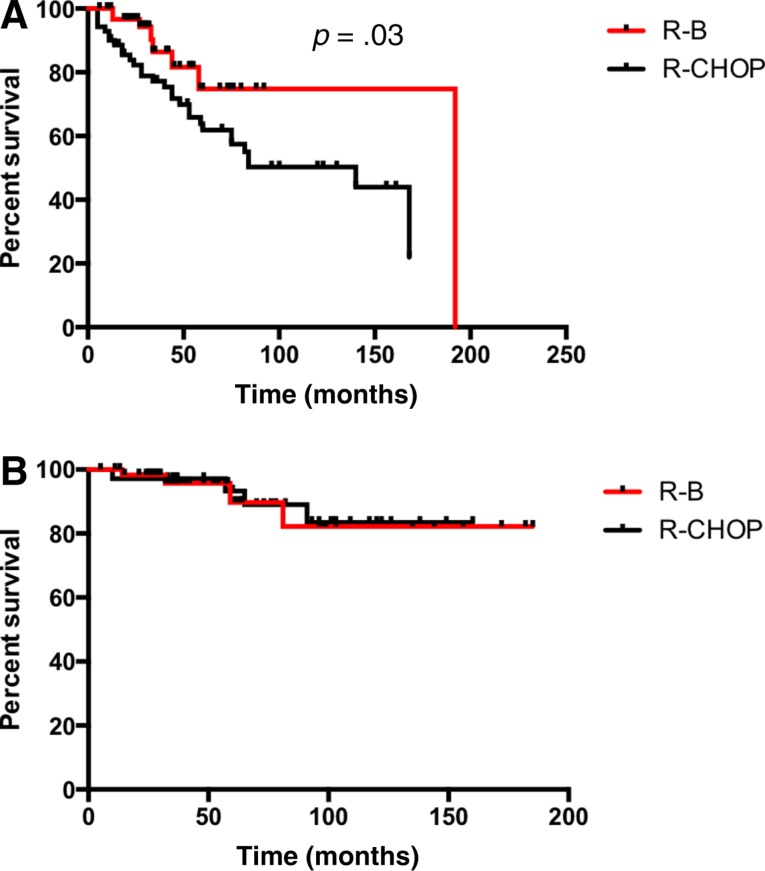

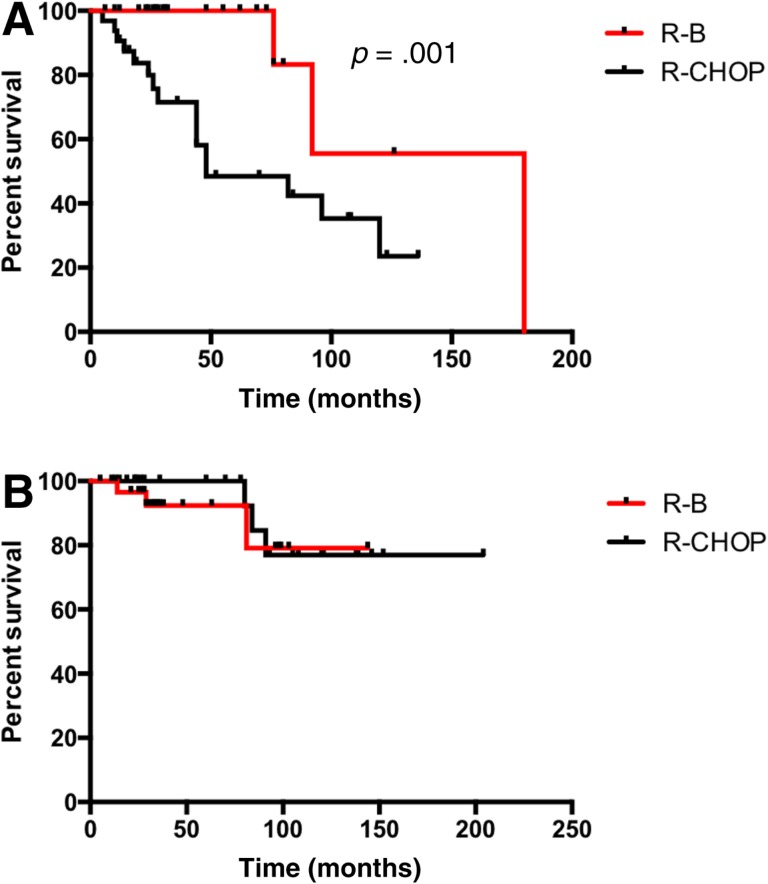

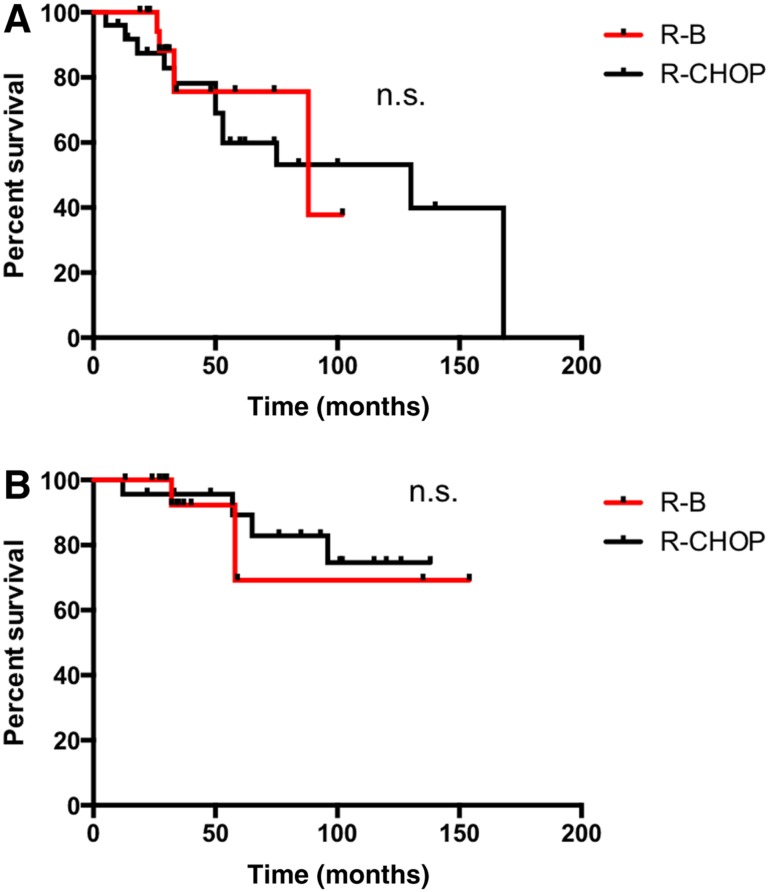

Median PFS of patients treated with R‐B was significantly longer in comparison with the R‐CHOP group (15 vs. 11.7 years; p = .03; Fig. 1A). Patients with BCL2 expression presented a superior PFS if treated with R‐B compared with R‐CHOP (15 vs. 4.8 years; p = .001; Fig. 2A). However, no difference was observed in patients with coexpression of BCL2 and BCL6 (88 vs. 130 months; p = .7; Fig. 3A). Median OS was not reached and did not differ between the treatment groups (p = .8; Fig. 1B). Sole BCL2 expression (not reached; p = .6; Fig. 2B) or BCL2 in combination with BCL6 did not influence OS (not reached; p = .7; Fig. 3B).

Figure 1.

Progression‐free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) in follicular lymphoma grade 3A. (A): PFS. (B): OS.

Abbreviations: R‐B, rituximab plus bendamustine; R‐CHOP, rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone.

Figure 2.

Progression‐free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) in follicular lymphoma grade 3A with BCL2 expression. (A): PFS. (B): OS.

Abbreviations: R‐B, rituximab plus bendamustine; R‐CHOP, rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone.

Figure 3.

Progression‐free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) in follicular lymphoma grade 3A with BCL2 and BCL6 expression. (A): PFS. (B): OS.

Abbreviations: n.s., non significant; R‐B, rituximab plus bendamustine; R‐CHOP, rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone.

Discussion

In the past few years, the standard of care of FL has changed because prospective and retrospective data favor R‐B over R‐CHOP [23], [24], [25]. However, while patients affected by FL3B are mainly treated according to the standard for aggressive B‐cell lymphomas, the best treatment strategy for FL3A remains a matter of debate. Therefore, we performed a subgroup analysis of our previous real‐life comparison of patients with FL who underwent either R‐B or R‐CHOP in the first line. Although the present analysis is retrospective, we provide evidence that the R‐B regimen seems to be more efficient and less toxic than R‐CHOP as a first‐treatment line in patients with FL3A.

The strengths of this study were the relatively large number of cases in a multicenter setting, the long follow‐up time, and the homogeneity of analyzed patients. Of note, “real‐life” studies provide important data because they avoid the known overestimation effects observed in pivotal trials [32]. The main limitations of this study were the same as those of every retrospective study: a mostly long accrual period, incomplete information on some variables considered for analysis, and the absence of a central pathology review. However, all participating centers have a lengthy experience in lymphoma diagnosis and management. Only recently, Laurent et al. [33] evaluated the importance of a central pathology revision in various hematologic malignancies and demonstrated that in FL the concordance rate between experts (99.05%) was significantly higher than reported in older analyses [34], [35], [36], [37], especially those conducted before the introduction of WHO classification [27], [38]. This likely reflects improvements in consistency among the experts themselves as a result of a more accurate diagnostic criteria, as well as new tools, including novel antibodies, polymerase chain reaction assays, and the fluorescence in situ hybridization test applicable on routine formalin‐fixed paraffin‐embedded samples [4]. Nevertheless, the long time frame of this study predated modern assessment of grade. Despite the promising results recently published by Laurent et al. [33], other authors [37], [39] provide more contradictory data regarding the reliability of local pathology reviews.

In the present analysis, we included only patients with FL grade 3A from a previously published cohort [25]. To improve the statistical power, 31 consecutive patients treated in Naples were added. Despite the higher number of patients with an unfavorable risk profile at time of diagnosis, ORR was similar in the two regimen groups (97% vs. 96% for the R‐B and standard treatment groups, respectively), suggesting that the two‐drug combination can overcome the negative impact of at least some of these factors. These results are comparable to those of the StiL trial, which included FL of grades 1 and 2 [23], showing an ORR of 93% versus 91% in patients treated with R‐B and R‐CHOP, respectively. However, these data differ from the BRIGHT trial [24], in which R‐B was superior to R‐CHOP (ORR 97% vs. 91%, respectively). The CR rate in the present analysis was higher than in both prospective trials (40% vs. 30% in the StiL trial [23] and 31% vs. 25% in the BRIGHT trial [24]), probably because of differences in patient population: our study included only patients with FL grade 3A, while Rummel et al. [23] and Flinn et al. [24] included different types of indolent non‐Hodgkin lymphomas (NHLs).

Similar to what was observed in the two prospective studies [23], [24], R‐B was clearly less toxic than R‐CHOP. Grade 3 and 4 neutropenia was significantly less frequent in the R‐B treatment group, translating into a significantly reduced occurrence of infections in comparison with R‐CHOP. Also, nonhematologic toxicities, such as neuropathy, skin reactions, alopecia, and nausea, were more frequently observed in patients treated with R‐CHOP. These findings are in line with the StiL trial [23], but they differ from the BRIGHT study [24], in which patients treated with R‐B had a higher incidence of nausea, vomiting, and skin reactions. The overall more favorable R‐B toxicity profile translated into a higher feasibility. In the StiL trial, a dose reduction was required in 4% of R‐B treated patients, compared with 11.2% of R‐CHOP [23], which is in line with the present experience. In contrast, fewer dose reductions were performed in the BRIGHT trial (6% vs. 4%) [24]. Unlike the StiL trial [23], we observed a late toxicity in terms of secondary primary malignancies occurring less often in the R‐B group compared with R‐CHOP (3% vs. 13%; p = .04).

Relapses were encountered less frequently in R‐B‐treated patients (16% vs. 41%), and this was in line with Rummel et al (39% vs. 57%) [23]. This finding could be attributed to a possibly better eradication of disease with the two‐drug combination. Prospective trials evaluating the presence of minimal residual disease are needed to elucidate this observation. The lower relapse rate led to a significant prolongation of PFS after R‐B versus R‐CHOP. This advantage was seen in patients who were BCL2 positive, but not in those with coexpression of BCL2 and BCL6. These two proteins are frequently found in B‐cell NHL, and both should be considered as reliable prognostic markers. Although some reports failed to show any impact of BCL2 protein expression on survival [40], [41], subsequent studies have reported that BCL2‐positive cases have a worse prognosis [42], [43], [44], [45], which is in line with the data presented herein for patients who underwent R‐B immunochemotherapy. Until now, published data regarding expression of BCL6 were conflicting because some authors observed a negative impact on the outcome of B‐cell lymphoma [46], [47], [48], whereas others did not [28], [49], [50], [51].

A PFS improvement after R‐B was previously reported by the StiL trial [23], suggesting a similar positive effect of this treatment on patients affected by FL3A as well as those of all grades. However, patients treated with R‐CHOP presented significantly higher LDH levels, which could be suspicious for transformation into an aggressive NHL. Positron emission tomography imaging could have provided more insight because high standardized uptake values are indicative of a possible transformation [52]. However, the biopsy performed at diagnosis in each patient did not confirm this suspicion. In the case of transformation into an aggressive lymphoma, R‐CHOP is considered the standard of care [53]. As previously reported [23], [25], the observed PFS prolongation did not translate into a OS advantage of R‐B over R‐CHOP. This could be because of the indolent clinical course of FL even after a relapse and the availability of efficient salvage treatments.

Conclusion

Our results suggest that R‐B as first‐line treatment in FL3A is better tolerated than R‐CHOP and induces more profound responses, leading consequently to a significantly lower relapse rate and prolonged PFS. Therefore, R‐B seems to be a valid treatment option for FL3A, although R‐CHOP must be preferred in case of any concern of transformation.

Footnotes

For Further Reading: Jennifer R. Brown, Florence Cymbalista, Jeff Sharman et al. The Role of Rituximab in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia Treatment and the Potential Utility of Biosimilars. The Oncologist 2018;23:288–296; first published on December 6, 2017.

Implications for Practice: Front‐line treatments for chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) include chemotherapy in combination with an anti‐CD20 monoclonal antibody (e.g., rituximab, ofatumumab, or obinutuzumab) or ibrutinib as single agent. Despite the evolving treatment paradigm, it is likely rituximab (plus chemotherapy) and targeted agents undergoing clinical evaluation will retain a significant role in CLL treatment. However, patents for many biologics, including rituximab, have expired or will expire in the near future and, in many regions, access to rituximab remains challenging. Together, these concerns have prompted the development of safe and effective rituximab biosimilars, with the potential to increase access to more affordable treatments.

Author Contributions

Conception/design: Patrizia Mondello

Provision of study material or patients: Patrizia Mondello, Normann Steiner, Wolfgang Willenbacher, Claudio Cerchione, Davide Nappi, Endri Mauro, Simone Ferrero, Salvatore Cuzzocrea, Michael Mian

Collection and/or assembly of data: Patrizia Mondello

Data analysis and interpretation: Patrizia Mondello, Michael Mian

Manuscript writing: Patrizia Mondello, Michael Mian

Final approval of manuscript: Patrizia Mondello, Normann Steiner, Wolfgang Willenbacher, Claudio Cerchione, Davide Nappi, Endri Mauro, Simone Ferrero, Salvatore Cuzzocrea, Michael Mian

Disclosures

Simone Ferrero: Janssen, Pfizer (C/A); Mundipharma (H). The other authors indicated no financial relationships.

(C/A) Consulting/advisory relationship; (RF) Research funding; (E) Employment; (ET) Expert testimony; (H) Honoraria received; (OI) Ownership interests; (IP) Intellectual property rights/inventor/patent holder; (SAB) Scientific advisory board

References

- 1. Harris NL, Jaffe ES, Diebold J et al. The World Health Organization classification of neoplastic diseases of the haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues: Report of the Clinical Advisory Committee Meeting, Airlie House, Virginia, November 1997. Histopathology 2000;36:69–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ganti AK, Bociek RG, Bierman PJ et al. Follicular lymphoma: Expanding therapeutic options. Oncology (Williston Park) 2005;19:213–228; discussion 228, 233–236, 239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mann RB, Berard CW. Criteria for the cytologic subclassification of follicular lymphomas: A proposed alternative method. Hematol Oncol; 1:187–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.A clinical evaluation of the International Lymphoma Study Group classification of non‐Hodgkin's lymphoma. The Non‐Hodgkin's Lymphoma Classification Project. Blood 1997;89:3909–3918. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Campo E, Swerdlow SH, Harris NL et al. The 2008 WHO classification of lymphoid neoplasms and beyond: Evolving concepts and practical applications. Blood 2011;117:5019–5032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ott G, Katzenberger T, Lohr A et al. Cytomorphologic, immunohistochemical, and cytogenetic profiles of follicular lymphoma: 2 types of follicular lymphoma grade 3. Blood 2002;99:3806–3812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Katzenberger T, Ott G, Klein T et al. Cytogenetic alterations affecting BCL6 are predominantly found in follicular lymphomas grade 3B with a diffuse large B‐cell component. Am J Pathol 2004;165:481–490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bosga‐Bouwer AG, van Imhoff GW, Boonstra R et al. Follicular lymphoma grade 3B includes 3 cytogenetically defined subgroups with primary t(14;18), 3q27, or other translocations: t(14;18) and 3q27 are mutually exclusive. Blood 2003;101:1149–1154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rodriguez J, McLaughlin P, Hagemeister FB et al. Follicular large cell lymphoma: An aggressive lymphoma that often presents with favorable prognostic features. Blood 1999;93:2202–2207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rodriguez J, McLaughlin P, Fayad L et al. Follicular large cell lymphoma: Long‐term follow‐up of 62 patients treated between 1973–1981. Ann Oncol 2000;11:1551–1556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Anderson JR, Vose JM, Bierman PJ et al. Clinical features and prognosis of follicular large‐cell lymphoma: A report from the Nebraska Lymphoma Study Group. J Clin Oncol 1993;11:218–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hans CP, Weisenburger DD, Vose JM et al. A significant diffuse component predicts for inferior survival in grade 3 follicular lymphoma, but cytologic subtypes do not predict survival. Blood 2003;101:2363–2367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bartlett NL, Rizeq M, Dorfman RF et al. Follicular large‐cell lymphoma: Intermediate or low grade? J Clin Oncol 1994;12:1349–1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wendum D, Sebban C, Gaulard P et al. Follicular large‐cell lymphoma treated with intensive chemotherapy: An analysis of 89 cases included in the LNH87 trial and comparison with the outcome of diffuse large B‐cell lymphoma. Groupe d'Etude des Lymphomes de l'Adulte. J Clin Oncol 1997;15:1654–1663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ganti AK, Weisenburger DD, Smith LM et al. Patients with grade 3 follicular lymphoma have prolonged relapse‐free survival following anthracycline‐based chemotherapy: The Nebraska Lymphoma Study Group Experience. Ann Oncol 2006;17:920–927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Miller TP, LeBlanc M, Grogan TM et al. Follicular lymphomas: Do histologic subtypes predict outcome? Hematol Oncol Clin North Am 1997;11:893–900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chau I, Jones R, Cunningham D et al. Outcome of follicular lymphoma grade 3: Is anthracycline necessary as front‐line therapy? Br J Cancer 2003;89:36–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hsi ED, Mirza I, Lozanski G et al. A clinicopathologic evaluation of follicular lymphoma grade 3A versus grade 3B reveals no survival differences. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2004;128:863–868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Horn H, Ziepert M, Becher C et al. MYC status in concert with BCL2 and BCL6 expression predicts outcome in diffuse large B‐cell lymphoma. Blood 2013;121:2253–2263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hiddemann W, Kneba M, Dreyling M et al. Frontline therapy with rituximab added to the combination of cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (CHOP) significantly improves the outcome for patients with advanced‐stage follicular lymphoma compared with therapy with CHOP alone: Results of a prospective randomized study of the German Low‐Grade Lymphoma Study Group. Blood 2005;106:3725–3732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Herold M, Haas A, Srock S et al. Rituximab added to first‐line mitoxantrone, chlorambucil, and prednisolone chemotherapy followed by interferon maintenance prolongs survival in patients with advanced follicular lymphoma: An East German Study Group hematology and oncology study. J Clin Oncol 2007;25:1986–1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Marcus R, Imrie K, Solal‐Celigny P et al. Phase III study of R‐CVP compared with cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and prednisone alone in patients with previously untreated advanced follicular lymphoma. J Clin Oncol 2008;26:4579–4586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Rummel MJ, Niederle N, Maschmeyer G et al. Bendamustine plus rituximab versus CHOP plus rituximab as first‐line treatment for patients with indolent and mantle‐cell lymphomas: An open‐label, multicentre, randomised, phase 3 non‐inferiority trial. Lancet 2013;381:1203–1210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Flinn IW, van der Jagt R, Kahl BS et al. Randomized trial of bendamustine‐rituximab or R‐CHOP/R‐CVP in first‐line treatment of indolent NHL or MCL: The BRIGHT study. Blood 2014;123:2944–2952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mondello P, Steiner N, Willenbacher W et al. Bendamustine plus rituximab versus R‐CHOP as first‐line treatment for patients with indolent non‐Hodgkin's lymphoma: Evidence from a multicenter, retrospective study. Ann Hematol 2016;95:1107–1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Harris NL, Jaffe ES, Stein H et al. A revised European‐American classification of lymphoid neoplasms: A proposal from the International Lymphoma Study Group. Blood 1994;84:1361–1392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Pileri SA et al. The 2016 revision of the World Health Organization classification of lymphoid neoplasms. Blood 2016;127:2375–2390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Höller S, Horn H, Lohr A et al. A cytomorphological and immunohistochemical profile of aggressive B‐cell lymphoma: High clinical impact of a cumulative immunohistochemical outcome predictor score. J Hematop 2009;2:187–194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Cheson BD, Horning SJ, Coiffier B et al. Report of an international workshop to standardize response criteria for non‐Hodgkin's lymphomas. NCI Sponsored International Working Group. J Clin Oncol 1999;17:1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Cheson BD, Pfistner B, Juweid ME et al. Revised response criteria for malignant lymphoma. J Clin Oncol 2007;25:579–586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Solal‐Céligny P, Roy P, Colombat P et al. Follicular lymphoma international prognostic index. Blood 2004;104:1258–1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Singal AG, Higgins PD, Waljee AK. A primer on effectiveness and efficacy trials. Clin Transl Gastroenterol 2014;5:e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Laurent C, Baron M, Amara N et al. Impact of expert pathologic review of lymphoma diagnosis: Study of patients from the French Lymphopath Network. J Clin Oncol 2017;35:2008– 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bowen JM, Perry AM, Laurini JA et al. Lymphoma diagnosis at an academic centre: Rate of revision and impact on patient care. Br J Haematol 2014;166:202–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lester JF, Dojcinov SD, Attanoos RL et al. The clinical impact of expert pathological review on lymphoma management: A regional experience. Br J Haematol 2003;123:463–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Proctor IE, McNamara C, Rodriguez‐Justo M et al. Importance of expert central review in the diagnosis of lymphoid malignancies in a regional cancer network. J Clin Oncol 2011;29:1431–1435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. LaCasce AS, Kho ME, Friedberg JW et al. Comparison of referring and final pathology for patients with non‐Hodgkin's lymphoma in the National Comprehensive Cancer Network. J Clin Oncol 2008;26:5107–5112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Campo E, Swerdlow SH, Harris NL et al. The 2008 WHO classification of lymphoid neoplasms and beyond: Evolving concepts and practical applications. Blood 2011;117:5019–5032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Smith LB. Pathology review of outside material: When does it help and when can it hurt? J Clin Oncol 2011;29:2724–2727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Llanos M, Alvarez‐Argüelles H, Alemán R et al. Prognostic significance of Ki‐67 nuclear proliferative antigen, bcl‐2 protein, and p53 expression in follicular and diffuse large B‐cell lymphoma. Med Oncol 2001;18:15–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Tang SC, Visser L, Hepperle B et al. Clinical significance of bcl‐2‐MBR gene rearrangement and protein expression in diffuse large‐cell non‐Hodgkin's lymphoma: An analysis of 83 cases. J Clin Oncol 1994;12:149–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Hadzi‐Pecova L, Petrusevska G, Stojanovic A. Non‐Hodgkin's lymphomas: Immunologic prognostic studies. Prilozi 2007;28:39–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Piris MA, Pezzella F, Martinez‐Montero JC et al. p53 and bcl‐2 expression in high‐grade B‐cell lymphomas: Correlation with survival time. Br J Cancer 1994;69:337–341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Hallack Neto AE, Siqueira SA, Dulley FL et al. Bcl‐2 protein frequency in patients with high‐risk diffuse large B‐cell lymphoma. Sao Paulo Med J 2010;128:14–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Mahmoud HM, El‐Sakhawy YN. Significance of Bcl‐2 and Bcl‐6 immunostaining in B‐non Hodgkin's lymphoma. Hematol Rep 2011;3:e26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Barrans SL, O'Connor SJ, Evans PA et al. Rearrangement of the BCL6 locus at 3q27 is an independent poor prognostic factor in nodal diffuse large B‐cell lymphoma. Br J Haematol 2002;117:322–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Lossos IS, Alizadeh AA, Eisen MB et al. Ongoing immunoglobulin somatic mutation in germinal center B cell‐like but not in activated B cell‐like diffuse large cell lymphomas. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2000;97:10209–10213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Berglund M, Thunberg U, Amini RM et al. Evaluation of immunophenotype in diffuse large B‐cell lymphoma and its impact on prognosis. Mod Pathol 2005;18:1113–1120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. de Leval L, Harris NL. Variability in immunophenotype in diffuse large B‐cell lymphoma and its clinical relevance. Histopathology 2003;43:509–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Dogan A, Bagdi E, Munson P et al. CD10 and BCL‐6 expression in paraffin sections of normal lymphoid tissue and B‐cell lymphomas. Am J Surg Pathol 2000;24:846–852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Colomo L, López‐Guillermo A, Perales M et al. Clinical impact of the differentiation profile assessed by immunophenotyping in patients with diffuse large B‐cell lymphoma. Blood 2003;101:78–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Noy A, Schöder H, Gönen M et al. The majority of transformed lymphomas have high standardized uptake values (SUVs) on positron emission tomography (PET) scanning similar to diffuse large B‐cell lymphoma (DLBCL). Ann Oncol 2008;20:508–512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Bastion Y, Sebban C, Berger F et al. Incidence, predictive factors, and outcome of lymphoma transformation in follicular lymphoma patients. J Clin Oncol 1997;15:1587–1594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]