Abstract

Introduction:

The extensive use of antibiotics has led to the emergence of multi-resistant strains in some species of the genus Acinetobacter.

Objective:

To investigate the molecular characteristics of multidrug-resistant of Acinetobacter ssp. strains isolated from 52 patients collected between March 2009 and July 2010 in medical intensive care units in Cali - Colombia.

Methods:

The susceptibility to various classes of antibiotics was determined by disc diffusion method, and the determination of the genomic species was carried out using amplified ribosomal DNA restriction analysis (ARDRA) and by sequencing of the 16s rDNA gene. Also, the genes of beta-lactamases as well as, integrases IntI1 and IntI2 were analyzed by PCR method.

Results:

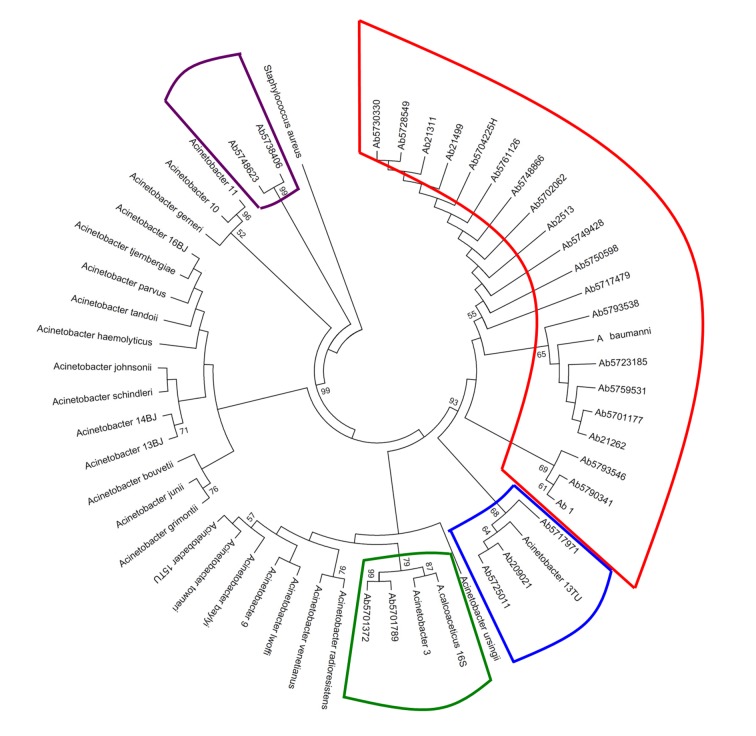

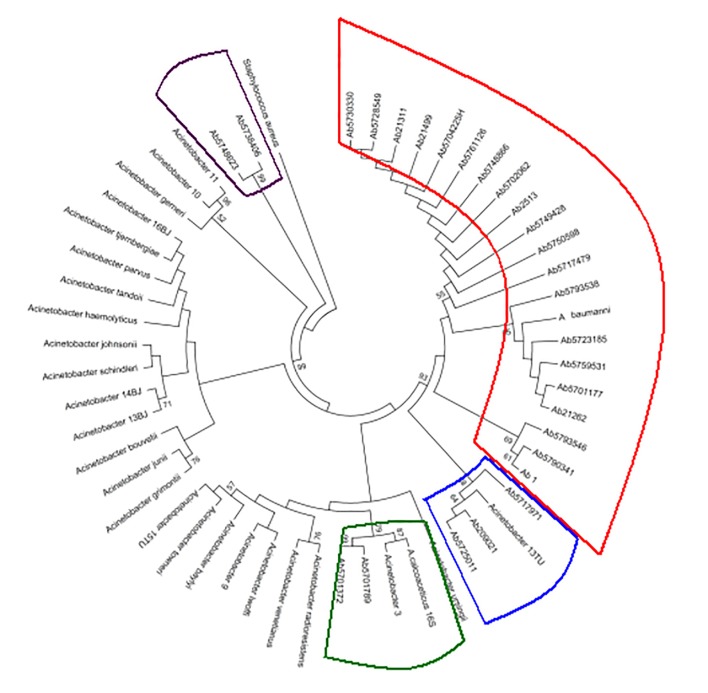

The phenotypic identification showed that the isolates belong mainly to A. calcoaceticus- A. baumannii complex. All of them were multi-resistant to almost the whole antibiotics except to tigecycline and sulperazon, and they were grouped into five (I to V) different antibiotypes, being the antibiotype I the most common (50.0%). The percent of beta-lactamases detected was: blaTEM (17.3%), blaCTX-M (9.6%), blaVIM (21.2%), blaIMP (7.7%), blaOXA-58 (21.2%), and blaOXA-51 (21.2%). The phylogenetic tree analysis showed that the isolates were clustering to A. baumannii (74.1%), A. nosocomialis (11.1%) and A. calcoaceticus (7.4 %). Besides, the integron class 1 and class 2 were detected in 23.1% and 17.3% respectively.

Conclusion:

The isolates were identified to species A. baumanii mainly, and they were multiresistant. The resistance to beta-lactams may be by for presence of beta-lactamases in the majority of the isolates.

Keywords: Acinetobacter Infections, Multiple Drug Resistance, 16S Ribosomal RNA, Healthcare Associated Infections

Resumen

Introducción:

El uso extensivo de antibióticos ha llevado a la emergencia de cepas multirresistentes en algunas especies del género Acinetobacter.

Objetivo:

Investigar las características moleculares de resistencia a múltiples fármacos de cepas aisladas de Acinetobacter spp. colectadas entre marzo de 2009 y julio de 2010 en 52 pacientes de unidades de cuidados intensivos en Cali - Colombia.

Métodos:

La susceptibilidad a diversas clases de antibióticos se determinó mediante el método de difusión de disco, y la determinación de la especie genómica se llevó a cabo usando un análisis de restricción de ADN ribosómico amplificado (ARDRA) y mediante la secuenciación del gen 16s de ADNr. Además, se analizaron por el método de PCR los genes de las beta-lactamasas, como también, las integrasas IntI1 e IntI2.

Resultados:

La identificación fenotípica mostró que los aislamientos pertenecen principalmente al complejo A. calcoaceticus - A. baumannii. Todos ellos eran multirresistentes a casi todos los antibióticos excepto tigeciclina y sulperazón, y se agruparon en cinco (I a V) antibitipos diferentes, siendo el antibiotipo I el más común (50%). El porcentaje de betalactamasas detectadas fue: blaTEM (17,3%), blaCTX-M (9,6%), blaVIM (21,2%), blaIMP (7,7%), blaOXA-58 (21,2%), blaOXA- 51 (21.2%). El análisis del árbol filogenético mostró que los aislados se agrupaban en A. baumannii (74.1%), A. nosocomialis (11.1%) y A. calcoaceticus (7.4%). Además, el integrón clase 1 y clase 2 se detectaron en 23.1% y 17.3% respectivamente.

Conclusión:

los aislamientos se identificaron principalmente como la especie A. baumanii, y fueron multirresistentes. La resistencia a los betalactámicos puede deberse a la presencia de betalactamasas en la mayoría de los aislamientos.

Palabras clave: Infecciones, Acinetobacter, resistencia, medicamentos, ARN ribosomal 16S, cuidado de la salud.

Introduction

Acinetobacter spp. is reported to be involved in hospital-acquired infections with increasing frequency 1 . The extensive use of antimicrobial chemotherapy in clinical environments has contributed to the emergence and dissemination of nosocomial Acinetobacter spp infections 2 . The species belonging to the A. calcoaceticus-A. baumannii complex (ACB complex) is mostly antibiotic-resistant Acinetobacter strains 3 . This complex has been implicated as the cause of a broad spectrum of infectious diseases such as pneumonia, meningitis, bacteremia, urinary tract infections, and device-related infections, especially in intensive care units (ICUs), and high mortality rates were associated 4 . Due to the organism's multidrug-resistant (MDR) phenotype, these infections are difficult to treat, which includes resistance to beta-lactams, aminoglycosides, fluoroquinolones, and carbapenems 5 , 6 . A significant nosocomial outbreak of MDR ACB complex in Colombia has occurred in the last years 7 .

Resistance to beta-lactam agents, including carbapenems in the ACB complex is due mainly to the production of the extended-spectrum beta-lactamases (ESBLs), but can also result from several other mechanisms including alterations in outer membrane proteins and penicillin binding proteins and increased activity of efflux pumps 8 . ESBLs with carbapenemases, such as metallo-beta-lactamases (MBL) or oxacillinases, represent the most concern due to the chance of rapid dissemination 9 . Whereas MBL found are of IMP and VIM types in A. baumannii 5 , the oxacillinases present four main OXA subgroups are the chromosomally located intrinsic OXA-51-like; the acquired OXA-23-like; OXA-40-like; and OXA-58-like 9 - 12 .

Most genes encoding these ESBLs are found on plasmids, or in the form of a gene cassette in an integron. Integrons are genetic elements that possess a particular recombination site, known as attI1, into which resistance genes can be inserted by site-specific recombination in the form of gene cassettes 13 . Different integron classes have been described, and the classes 1, 2 and 3 have been associated with antibiotic resistance 13 , 14 . Dissemination of these antibiotic resistance integrons, which are unable to promote their mobilization, is mainly linked to transposons and plasmids. Different reports exist which have identified integrons as responsible for the presence and acquisition of antibiotic resistance A. baumannii have been published 13 , 14 . There is limited data on the global epidemiology of A. baumannii in our region. However, the distribution of class 2 integron is highly frequent in A. baumannii clinical isolates from Argentina, Chile, and Brazil 14 , 15 .

The objectives of the present study were to analyze the phenotypic and molecular characteristics of ACB complex and antibiotic resistance in clinical isolates in a Colombian tertiary-care hospital. As well as determine the antimicrobials resistance profiles of the isolated strains. We also tested for the presence of MBL or ESBL producing Acinetobacter spp.

To test the hypothesis that most genes encoding MBL or ESBL are found on gene cassettes of integrons, we have examined representative isolates for the presence of class 1 and class 2 integrons and the associated antimicrobial resistance genes by PCR. Knowledge on the epidemiology and molecular mechanisms of antimicrobial resistance in this important pathogen are essential to implement intervention strategies.

Material and Methods

A descriptive study was carried out and was endorsed by the ethics committee of the hospital.

Bacterial strains clinical samples

The study included 52 Acinetobacter ssp strains collected from clinical specimens, previously identified by the Vitek GNI card (bioMeriex Vitek Inc., Hazelwood, MO) that they grew on standard MacConkey agar at 37° C for 48 h, between March 2009 and July 2010 of a medical intensive care unit at Rafael Uribe Uribe University Hospital from Cali - Colombia. The clinical samples were obtained from: the nasal swabs, 24 (46.2%); wounds, 12 (26.1%); catheter tip, 6 (11.6%); the urinary tract, 6 (11.6%); and 4 (7.7%) blood. All of the samples were stored at −80° C in nutrient broth with 15% glycerol. From the 52 Acinetobacter spp clinical isolates strains, 24 (46.2%) were obtained.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing

The susceptibility to various classes of antibiotics was determined by disc diffusion method on a Mueller-Hinton (MH) agar (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, MI, USA), by the Clinical and Laboratory Standard Institute (CLSI) guidelines 16 . Both strains Acinetobacter baumannii (ATCC® 19606(tm)), and Escherichia coli (ATCC® 25922(tm)) were used as quality control strains. The antibiotic discs (Oxoid ®) tested were the follows: trimetroprim/sulfametoxazol (SXT, 23.75 μg/1.25 μg); ticarcillin/clavulanato (TIM, 75μg/10 μg); gentamicin (GEN, 10 μg); tobramycin (TOB, 10 μg); ciprofloxacin (CIP, 5 μg); ceftazidime (CAZ, 30 μg); cefepime (FEP, 30 μg); aztreonam (ATM, 30 μg); imipenem (IMP, 10 μg); meropenem (MEM, 10 μg); ampicillin/sulbactam (SAM, 10 μg/10 μg); amikacin (AMK, 10 μg); cefoprazone/sulbactam (sulperazona, SUL, 75 μg/30 μg); and tigecycline (TIG, 15 μg). According to Manchanda et al. 17 , the MDR Acinetobacter spp have defined whether the isolates are resistant to three antibiotics different to ceftazidime, such as ciprofloxacin, gentamicin, and imipenem.

Identification of isolates of Acinetobacter spp: Amplified Ribosomal DNA Restriction Analysis (ARDRA)

The genomic species of Acinetobacter spp were determined by ARDRA, according to Vaneechoutte et al. 18 . In brief, the DNA from an overnight culture in LB broth at 37° C was extracted using the "Easy-DNATM" kit (Invitrogen, life technologies ®) according to the manufacturer's instructions. After to electrophoresis, the gel was stained with ethidium bromide (1.5 μg/mL) and analyzed on a FOTO/Analyst(r) Investigator/FX Systems (FOTODYNE Incorporated). For each sample, the PCR reaction was performed for 16S rDNA amplification using the following primer pair: Acf5´-TGG CTC AGA TTG AAC GCT GGC GGC-3´ and Acr5´-TAC CTT GTT ACG ACT TCA CCC CA-3´. The PCR products were digested with the following enzymes: CfoI; Alu; Mbo; and MspI (Fermentas(tm)) and separated by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE 8.0%).

The last restriction profiles were compared to strain library database (http://users.ugent.be/~mvaneech/ARDRA/Acinetobacter.html) to identify the species according to Dijkshoorn et al 19 . The A. baumannii (ATCC® 19606(tm)) strain was used as controls.

Identification of clinical isolates of Acinetobacter spp by 16S rDNA PCR-sequencing

The 27 PCR products to 16S rDNA gene were purified using the High Pure PCR product Purification Kit Version 20 kit, according to company instruction (Roche Applied Science®) and then, each purified PCR products were direct sequencing by Sanger dideoxy method using an ABI 3730XL sequencer. The 16S rDNA sequences were aligned with 27 Acinetobacter reference sequences harbored in the GenBank-NCBI dataset.

The phylogenetic tree was done using the MEGA software v.5 under Maximum Likelihood model with the Kimura-2-parameters, and Gamma distribution assuming invariable sites (K2+G+I). The robustness of phylogenetic tree was calculated by a bootstrap no parametric with 1,000 replicates 20 , 21 . A Staphylococcus aureus sequence was used as outgroup.

Detection of ESBL genes by PCR

ESBL genes, such as blaTEM; blaSHV; blaOXA; blaCTX-M; blaIMP; and blaVIM, were detected by PCR using the primers are listed in Table 1 22 - 30 ). The PCR reaction final volume of 50 μl with 5-10 ng (genomic DNA) reaction buffer, 1 U of Taq polymerase (Bioline, London, United Kingdom), 200 µM each deoxynucleoside triphosphate, 1.5 or 2.5 mM MgCl2, 10 pmol of each primer. Thermocycler temperature was 94° C for 5 min; 94° C for 30 s by 35 cycles. To blaTEM, 52° C for 45 s; blaOXA-51 and blaOXA-58, 62° C for 1 min; blaCXT-M, 51° C for 45 s; blaVIM and blaIMP 51° C for 1 min; and 72° C for 60 s. The final step of 10 min at 72° C.

Table 1: Primers used in the study.

| Primer | Oligonucleotide sequences | Size (bp) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| rDNA16S AC | F-5'_TGGCTCAGATTGAACGCTGGCGGC_3' | 1,500 | 18 |

| R-5'_TACCTTGTTACGACTTCACCCCA_3' | |||

| blaTEM | F-5´_ATGAGTATTCAACAT TTCCG_3´ | 956 | 23 |

| R-5´_CTGACAGTTACCAATGCTTA_3´ | |||

| bla VIM | F-5´_AAAGTTATGCCGCACTCACC_3´ | 865 | 24 |

| R-5´_TGCAACTTCATGTTATGCCG_3´ | |||

| bla IMP | F- 5´_ATGAGCAAGTTATCCTTATTC_3´ | 741 | 25 |

| R- 5´_GCTGCAACGACTTGTTAG_3´ | |||

| blaCTX-M-9 | F -5´_GTGACAAAGAGAGTGCAACGG_3´ | 856 | 26 |

| R-5´_ATGATTCTCGCCGCTGAAGCC_3´ | |||

| blaOXA-51 | F-5´_CGGAGAACGACTCCTCATTAAAAA_3´ | 431 | 27 |

| R-5´_TTTAGCTCGTCGTATTGGACTTGA_3´ | |||

| blaOXA-58 | F-5´_AAGTATTGGGGCTTGTGCTG_3´ | 599 | 28 |

| R-5´_CCCCTCTGCGCTCTACATAC_3´ | |||

| Int1 | F-5´_CAGTGGACATAAGCCTGTTC_3´ | 160 | 29 |

| R-5'_CCCGAGGCATAGACTGTA_3´ | |||

| Int2 | F-5´_TTGCGAGTATCCATAACCTG_3´ | 288 | 29 |

| R-5´_TTACCTGCACTGGATTAAGC_3´ | |||

| CS | R-5´_GGCATCCAAGCAGCAAG_3´ | Variable | 29 |

| F-5´_AAGCAGACTTGACCTGA_3´ | |||

| hep35 | R-5´_TGCGGGTYAARGATBTKGATTT_3´ | 491 | 30 |

| hep36 | F-5´_CARCACATGCGTRTARAT_3´ |

Detection of integrase genes by PCR

The integrase class 1 (intI) and 2 (intII) genes were amplified as previously described 15 , 30 . Amplification for each one was done in 50 µL volumes using 5-10 ng (genomic DNA) reaction buffer, 2 U of Taq polymerase (Bioline, London, United Kingdom), 200 µM each deoxynucleoside triphosphate, 2,0 mM MgCl2, 10 pmol of each primer. PCR conditions were as follows: a hot start at 94° C for 5 min; 94° C for 30 s by 35 cycles, 30 s at both 55° C; and a final step of 10 min at 72° C.

The reaction mixture to the degenerate primers hep35 and hep36 were equivalents to the previous except for the concentration of each primer (2.0 µM), and for the PCR extension steps (72o C and 2 min).

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed using Stata version 11.0 (Stata Corp, College Station, Tex). Categorical variables were analyzed using χ2 test. All tests were two-tailed with p <0.05 considered significant.

Results

Antibiotic susceptibility

Antibiotyping tested by disk diffusion method showed multi-resistance to a large range of antibiotics. Most isolates of Acinetobacter spp. were resistant to trimethoprim /sulfamethoxazole, gentamicin, amikacin, tobramycin, ticarcillin/clavulanic acid, cefepime, ceftazidime, and imipenem. They were resistance rates of 100% while presenting variable susceptibility to ciprofloxacin (51/52, 98.1%), levofloxacin (45/52, 86.5%), ampicillin-sulbactam (49/52, 94.2%) and meropenem (50/52, 96.2%). The antimicrobial agents to which Acinetobacter spp strains were most susceptible were tigecycline and sulperozone. In contrast, 21.2% (11/52) and 28.8% (15/52) of them were resistant to tigecycline and sulperozone, respectively. In addition, all isolates were resistant to at least three classes of antibiotics (imipenem o meropenem, amikacin o tobramycin and extended-spectrum cephalosporins.), hence meeting the criteria for multidrug resistance 17 . Remarkable, from the isolates circulated in July and September 2009, 10 isolates (19.3%) were considered Pan Drug Resistant (PDR) according to with Falagas et al. 31 , demonstrating resistance to all antibiotics tested in this study.

A common antibiotype in unrelated co-circulating strains

Depending upon their susceptibilities to 14 different antimicrobial drugs, the 52 isolates of ACB complex were grouped into five (I to V) different antibiotypes. Most the isolates belonging to antibiotype I (50.0%), with fewer isolates belonging to antibiotype IV (19.3%), antibiotype II (17.3%) and antibiotype V, with only 1.9% of all the isolates. Interestingly, the isolates belonging to antibiotype I were susceptible to tigecycline and sulperozone, and most clinically significant isolates were found in nasal swabs (57.7%), followed by wound and catheter tips (23.1% and 15.4%, respectively) (p <0.05) (Table 2). Twenty-five isolates were collected between June and November of 2009. Only one isolate was detected in May 2010.

Table 2. Antibiotypes of A. baumannii-calcoaceticus complex isolates by sample site, resistance and susceptibility profiles.

| Antibiotype | Isolates n (%) | Sample Site | Resistance profile | Susceptibility profile | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nt n (%) | Bl n (%) | Ct n (%) | Wd n (%) | Ur n (%) | Us n (%) | ||||

| I | 26 (50.0) | 15 (57.7) | 1 (3.8) | 4 (15.4) | 6 (23.1) | - | - | AMK, GEN, TOB, CIP, LVX, SXT, SAM, TIC/AC, FEP, CAZ, IMP, MEM | TIG, SUL |

| II | 9 (17.3) | 6 (66.7) | - | 2 (22.2) | - | 1 (11.1) | - | AMK, GEN, TOB, CIP, SXT, TIC/AC, FEP, CAZ, IMP | TIG, SUL/ LVX, SAM o MEM |

| III | 6 (11.5) | 1 (16.7) | 2 (33.3) | - | 1 (16.7) | 2 (33.3) | - | AMK, GEN, TOB, CIP, LVX, SXT, SAM, TIC/AC, FEP, CAZ, IMP, MEM | TIG ó SUL |

| IV | 10(19.3)* | 2 (20.0) | - | - | 5 (50.0)** | 1 (10.0) | 2 (20.0) | AMK, GEN, TOB, CIP, LVX, SXT, SAM, TIC/AC, FEP, CAZ, IMP, MEM, TIG, SUL | - |

| V | 1 (1.9) | - | 1 (100) | - | - | - | - | AMK, GEN, TOB, SXT, SAM, TIC/AC, FEP, CAZ, IMP, MEM | TIG, SUL, CIP, LVX |

| Total | 52 (100) | 24 (46.2) | 4 (7.7) | 6 (11.5) | 12 (23.1) | 4 (7.7) | 2 (3.8) | ||

The antibiotype IV significantly grouped the PDR (19.3%) isolates (p <0.05) and was detected more frequently in wound (50%; OR = 5.000; p= 0.025). This antibiotype was first detected in March of 2009 and appeared again in July, August, and November of the same year, as well in April, May, and June of 2010. As shown in Table 2, 27 isolates of A. baumannii (37.1%) exhibited five distinct antibiotypes. Twelve of the isolates (54.5%) were classified as having antibiotype I, two (9.1%) isolates to antibiotype III, and four (18.2%) isolates to antibiotype and one (5%) isolate to antibiotype V. Four strains of A. calcoaceticus revealed two distinct antibiotypes, and three strains of 13TU showed three different antibiotypes.

Identification of isolates of Acinetobacter spp

The genomic identification of 52 strains belonging to the ACB complex was performed using the ARDRA method and sequencing (Table 3, 4 ).

Table 3. Distribution and molecular characterization of A. baumannii-calcoaceticus complex isolates.

| Code | Sample Site | Antibiotype | Bla Genes | Integron | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OXA-51 | TEM | CTXM-9 | VIM-2 | IMP-1 | OXA-58 | ||||

| 5790341 | Nasal trace | 1 | + | ||||||

| 5793548 | Nasal trace | 1 | + | + | + | ||||

| 21262 | Urine | 2 | + | ||||||

| 5701177 | Wound | 1 | + | + | + | ||||

| 1 | Wound | 4 | + | + | + | ||||

| 5793546 | Nasal trace | 1 | + | + | + | ||||

| 5702062 | Nasal trace | 2 | + | ||||||

| 5701373 | Wound | 1 | + | + | + | + | |||

| 5704225H | Wound | 4 | + | + | |||||

| 5717479 | Nasal trace | 1 | + | ||||||

| 5718164 | Nasal trace | 2 | + | + | + | ||||

| 21311 | Wound | 1 | + | + | |||||

| 5728549 | Wound | 3 | + | + | + | ||||

| 21499 | Nasal trace | 1 | + | + | |||||

| 5730330 | Catheter tips | 1 | + | + | + | ||||

| 5748866 | Blood | 5 | + | ||||||

| 5749428 | Nasal trace | 1 | + | + | + | ||||

| 5761126 | Catheter tips | 1 | + | + | |||||

| 5750598 | U. secretion | 4 | + | + | |||||

| 5723185 | Nasal trace | 1 | + | + | |||||

| 2513 | Urine | 3 | + | + | + | + | |||

| 5759531 | Nasal trace | 4 | + | + | + | + | |||

| 209021(13TU) | Nasal trace | 3 | + | ||||||

| 5725011 (13TU) | Nasal trace | 2 | + | + | |||||

| 5717971 (13TU) | Nasal trace | 1 | + | + | + | ||||

| Ab3 (A. calcoaceticus) | Wound | 1 | + | + | + | ||||

| 5701789 (A. calcoaceticus) | Nasal trace | 4 | + | + | |||||

| 5701372 (A. calcoaceticus) | Nasal trace | 1 | |||||||

| 85.7% | 21.4% | 10.7% | 25.0% | 10.7% | 53.6% | 28.6% | |||

Table 4. A. baumannii-calcoaceticus complex profiles obtained by amplified rRNA gene restriction analysis (ARDRA).

| No. | Genotype Sequence | ARDRA Profile | Isolates | Enzymes | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CfoI | AluI | MboI | MspI | ||||

| 1 | AB | AB | 5704225H | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 2 | AB | AB | Ab19606 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 3 | AB | AB | 2513 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 4 | AB | AB | 5748866 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 5 | AB | AB | 5790341 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 6 | AB | AB | 5730330 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 7 | AB | AB | Ab21499 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 9 | AB | AB | Ab21311 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 10 | AB | AB | 5728549 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 11 | AB | AB | 5717479 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 12 | AB | AB | 5793538 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 13 | AB | AB | 5761126 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 14 | AB | AB | 5702062 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 16 | AB | AB | 21262 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 17 | AB | AB | Ab1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| 18 | AB | AB | 5701177 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| 19 | AB | AB | 5759531 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| 20 | AB | AB | 5750598 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| 21 | 13TU | AB | 209021 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 22 | 13TU | AB | 5725011 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 23 | 13 TU | AB | 5717971 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| 24 | UD | AB | 5704581 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 25 | Calcoaceticus | 13TU | 5701372 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| 26 | Calcoaceticus | 13TU | 5701789 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 27 | UD | 13TU | 5748623 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 28 | AB | 3U | 5793546 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 3 |

| 29 | UD | 3U | 5738406 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 1 |

| 30 | UD | UD | NAC51 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 1 |

The resistance profile were: Calcoaceticus=A. calcoaceticus (2 2 1 3); AB= A. baumannii (1 1 1 1 / 1 1 1 3); 3U= Acinetobacter 3U (2 1 3 3); A. haemolyticus (1 4 1 2); 13TU= Acinetobacter 13TU (2 1 1 1 / 2 1 1 3); UD= undefined

The results revealed that 23 (44.0%) isolates had the combined profile '1 1 1 2 3' or '1 1 1 2 1' for the several enzymes CfoI, AluI, MboI, RsaI, and MspI. According to the library of references profiles strains identified the organisms as species 2 (A. baumannii), three (5.8%) were A. nosocomialis (13TU), two were A. calcoaceticus, and two were A. pitti (genospecies 3).

For the NCBI-BLAST analysis, 27 strains were queried using sequences of a 1,500 bp fragment of the 16S rDNA. This identification of all clinical isolates to the species level showed that all amplicons had sequence concordance of 61 to 99% 32 .

In Figure 1, shown the Acinetobacter genospecies phylogenetic tree by 16s rDNA sequencing analysis. From all isolates, 74.1% (20/27) were clustering with A. baumannii while A. nosocomialis constituted 11.1% (3/27) of the total. However, we find ambiguity between the two methods when defining the genospecies A. calcoaceticus, Acinetobacter 3U, Acinetobacter 13U as shown in Table 4.

Figure 1. Acinetobacter genospecies phylogenetic tree by 16s rDNA sequencing analysis. In total, 27 clinical isolates were compared with Acinetobacter 16s rDNA16 sequences reported in the GenBank-NCBI. The phylogenetic tree was done using the MEGA software v.5 under Maximum Likelihood model with the Kimura-2-parameters, and Gamma distribution assuming invariable sites (K2+G+I). The robustness of phylogenetic tree was calculated by a bootstrap no parametric with 1000 replicates.

Molecular characterization of ESBL genes

All ESBL-producing isolates in ACB complex were subjected to PCR experiments to detect the ESBL genes, including blaTEM, blaSHV, blaCTX-M, blaOXA-51, blaOXA-58, blaVIM, and blaIMP. Thirty-nine isolates (75.0%) carried several bla genes (up to two genes).

PCR amplification of class A beta-lactamase genes revealed that 17.3% (9/52) of the isolates carried blaTEM-1 and five (9.6%) isolates contained blaCTXM-9, while blaOXA-58 was found significantly in all carbapenem-resistant A. baumannii strains (p <0.05). The blaTEM-1 gene was identified in four isolates of A. baumannii, and one isolate of A. calcoaceticus. The blaCTXM-9 gene was detected in two isolates of A. calcoaceticus, two isolates of A. baumannii, and one isolate of 13TU, the blaOXA-58 gene was detected in once an isolate of A. baumanni, two isolates of A. calcoaceticus, and one isolate of 13TU. All A. baumannii isolates were positive for blaOXA-51-like genes. PCR did not detect the blaOXA-23 and blaSHV genes.

Among MBL-producing isolates in ACB complex, blaVIM-2 and blaIMP-1 were found in 21.2%, and 7.7% of isolates, respectively. In 30.0% of the A. baumannii strains were detected the blaVIM-2 gene, and all were obtained from nasal swabs.

Detection of integrons by PCR

PCR detection of the intI1, intI2, and integrase genes demonstrated the presence of integrons in Acinetobacter species isolated. PCR performed the determination of the size of any inserted gene cassette within the genome. Overall, PCR of the integrase gene resulted in a frequency of integron-positive isolates of 38.5% (20/52) with various insert sizes within the ACB complex, in according to with previous studies that have reported a high frequency of multiresistant gram-negative isolates containing integrons (13-15,25,30).

Class 1 integrons were found in 23.1% (12/52) of the isolates of ACB complex. The length the amplicons of variable regions ranged between 0.75 to 2.5 kb; 0.75 kb (13.0%), 2.5 kb (5.0%) and (0.75 +2.5 kb) (7.0%). Further, PCR could be helpful to determine their gene cassette assortments. The most number of isolates with integrons belonging to antibiotype I and were found in nasal swabs and wounds. The intI2 gene of class 2 integrons were detected in 17.3% (9/52) of the isolates. The presence of class 2 integrons, in six isolates, which also contained a class 1 integron was statistically significant (p <0.05).

Class 1 and 2 integrons were detected in two isolates belonging to antibiotype I and IV with blaTEM-1 and blaOXA genes. Additionally, isolates belonging to antibiotype II and III also contained integrons. In contrast, no integrin-positive isolates were found in antibiotype V.

The integrons were found in 30.0% (7/23) isolates of A. baumannii. Class 1 integrons were detected in 26.1% (6/23) of the A. baumannii isolates, whereas only one A. baumannii strain contained a class 2 integron (Table 3). Integrons were detected in four (13.6%) A. baumannii isolates obtained from nasal swabs, two from (9.1%) from wounds, and one (4.5%) from urinary tracts, although the association was not statistically significant (p <0.05). Also, the integron-positive A. baumannii isolates contained blaTEM-1and blaVIM-2 genes.

Discussion

Nosocomial infections due to A. baumannii have been reported throughout the world 5 , 33 . However, there is little information about the epidemiological behavior of the isolates circulating within the city of Cali. In this regard, the availability of 52 nosocomial isolates has offered the opportunity to assess the susceptibility profiles, the determinants of resistance to antibiotics and their mechanisms of resistance. The majority of the isolates of the ACB complex were more frequent in nasal tracking (46.2%), and of these, 63.6% corresponds to A. baumannii in patients admitted to the ICU. This finding is significant because the nasal colonization in patients older than 65 years with pre-existing lung disease or any debilitating diseases especially in the ICU has a higher risk to develop a Health care-associated infections (HAIs) 34 , 35 .

On the other hand, it concerns that all the 52 isolates were multidrug resistant to antibiotics, and tigecycline only sulperazona maintained the antimicrobial activity against the majority of the isolates evaluated (80.0%). Also, we identified PDR isolates (19.3%), with a statistically significant value (p <0.05), a result similar to the one reported by some authors in Brazil in the same years of this study, where we found isolates with this feature in 11.0% 31 .

In Colombia, the resistance reported in A. baumannii has increased in recent years. Specifically, in Bogotá between the years 2001 and 2008, there were isolated strains sensitive to carbapenems, quinolones, and next-generation cephalosporins and aminoglycosides in 30% of the cases 36 . Also, Pinzon et al. 37 for that same year, reported strains sensitive to carbapenems (35.8%); however, in 2012, the number of isolates with resistance to carbapenems had increased, still more than 90% 38 .

In 2009, the PAHO reported in countries of Latin America percentages of carbapenem resistance above 70%, and similar results in the behavior of the resistance to aminoglycosides, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole in several countries of Central and South America 39 .

The reports of the SENTRY in countries of Latin America, Europe, and the United States indicate that Acinetobacter spp. present high rates of resistance even to carbapenem. A multicenter study conducted by Higgins et al. 33 in the year 2010 showed that 100% of the isolates of A. baumannii were resistant to imipenem, by the data obtained in this study for the same period. All of the isolated ACB complexes were multidrug resistant, including the isolates of A. baumannii, with percentages of carbapenem resistance more than 96%, which shows an increase in the resistance to antibiotics in the past few years. These findings are disturbing because the new antibacterial agents developed, such as doripenem, ceftobiprole, and ceftaroline, do not show activity against A. baumannii resistant to cephalosporins and carbapenems 40 . Boo et al. 41 , raise the possibility that a co-selection of isolates resistant to carbapenems occurs by the acquisition of carbapenemase OXA class D type. Our study showed that all isolates of A. baumannii presented the ability to hydrolyse broad-spectrum cephalosporins (ceftazidime and cefepime) and carbapenems (imipenem and meropenem). We detected the presence of beta-lactamase type OXA-51 and OXA-58, which would explain the resistance so marked to carbapenem, similarly reported by Gales et al 42 .

This study demonstrated the poor capacity of Acinetobacter species identification by the Vitek-2 GNI system. It highlights the need to regard such results as preliminary data. Accurate identification using molecular methods is not only important in the investigation of outbreaks caused by Acinetobacter species, but also is relevant in epidemiological studies such as this report. Our results are like the reports published in other geographic regions 43 and coincide with the reports of Karageorgopoulos et al. 44 , who found sensitivity to tigecycline lower than 90% of the isolates of Acinetobacter spp. They make it a potentially useful treatment option against highly resistant bacteria; however, few of these bacteria also present resistance to tigecycline.

Within multiresistant isolates of the ACB complex and those of A. baumannii, bla (TEM-1, CTX-9, OXA-58, IMP-1 and VIM-2) was detected. Although the presence of the beta-lactamase TEM-1 is reported as one of the leading causes of resistance to beta-lactamic antibiotics in the A. baumannii isolates, in this study, only 22.7 % of the isolates were carriers of the gene blaTEM-1. In recent years the trend has changed; the increase in the resistance to carbapenems is mainly due to the presence of metallo beta-lactamases and class D type carbapenemase OXA, whose overexpression is regulated by the presence of upstream insertion elements, such as ISAba1 11 .

In this study, 38.5% of the isolates of ACB complex and 50.0% of A. baumannii presented beta-lactamases type OXA-58. Despite that, some reports have suggested that genes of OXA type beta-lactamases are transported in integrons 37 , 38 , our results showed that 82% of the isolates of the ACB complex and A. baumannii that contained these genes type did not show related to integrons. These results are consistent with those reported by Poirel et al. 45 , who said that these genes are not usually found in the form of gene cassettes and, according to the same author, these genes are carried on plasmids or are associated with a process of homologous recombination.

The presence of integrons (class 1 and 2) in 40% of the isolates was statistically significant; both classes of integrons have been described between the members of the genus Acinetobacter isolated in both clinical and environmental settings 14 . It is reported that the epidemic strains of A. baumannii tend to contain a greater number of integrons that are non-epidemic, and affirms that the use of antibiotics has a high impact on the development of the diversity and maintenance of these strains in the ICU 46 .

The class 1 integron presents multiple cassettes, which confers resistance towards several antibiotics, as a distinctive phenotypic stamp on the isolates of A. baumanni 13 - 15 , 30 , which would explain the multidrug resistance detected in isolates of the ACB complex and A. baumannii. The integration of these elements in the bacterial chromosome can affect the expression of genes such as blaOXA-51, which encodes an Amp c, b, and the chromosomal carbapenemase. In this study, all 22 isolates of A. baumannii showed resistance to cephalosporins and carbapenems; however, only 25% of them detected integrons within the genome. Of the ACB complex, 32 isolates were not integrons, by which the multidrug resistance to antibiotics in these isolates must be related to other mechanisms of resistance which may be plasmid-mediated or through the reduction of the cell membrane or wall permeability 47 . The largest numbers of integrons were detected in isolates obtained from sample tracking and nasal surgical wounds. These results do not agree with those obtained by Koleman et al. 29 , whereas that the largest number of integrons was detected in isolates from blood and secretion; this discrepancy is probably due to the greater number of isolates of this study that were obtained from nasal colonization and absence of infections.

Acknowledgments

We thank the University Clinic Rafael Uribe Uribe for allowing us to do this study with clinical isolates of their patients, to CIDEIM (Centro International de Entrenamiento e Investigaciones Medicas) for the gift us the 3386 strain of Pseudomonas aeruginosa used how to control and to Universidad Libre Seccional Cali for finance this study.

References

- 1.Peleg AY, Seifert H, Paterson DL. Acinetobacter baumannii Emergence of a Successful Pathogen. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2008;21:538–582. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00058-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maragakis LL, Perl TM. Acinetobacter baumannii Epidemiology, Antimicrobial Resistance and Treatment Options. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:1254–1263. doi: 10.1086/529198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scott P, Deye A, Srinivasan C, Murray K, Moran E. Hulten J et al An outbreak of multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii-calcoaceticus complex infection in the US military health care system associated with military operations in Iraq. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:1577–1584. doi: 10.1086/518170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sunenshine R, Wright L, Maragakis AD, Harris X, Song J. Hebden SE et al Multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter infection mortality rate and length of hospitalization. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13:97–103. doi: 10.3201/eid1301.060716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Perez F, Hujer AM, Hujer KM, Decker BK, Rather PN, Bonomo RA. Global challenge of multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007;51:3471–3484. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01464-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ledeboer N, Hodinka R. Molecular Detection of Resistance Determinants. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49(9) Suppl:S20–S24. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saavedra SY, Nuñez JC, Pulido IY, González EB, Valenzuela EM, Reguero MT. Characterization of carbapenem resistant Acinetobacter calcoaceticus-A baumannii complex isolates in a third level hospital in Bogotá, Colombia. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2008;31(4):389–391. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2007.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Giamarellou H, Antoniadou A, Kanellakopoulou K. Acinetobacter baumannii a universal threat to public health? Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2008;32:106–119. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2008.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Villegas MV, Kattan J, Correa A, Lolans K, Guzman AM, Woodford N. Dissemination of Acinetobacter baumannii Clones with OXA-23 Carbapenemase in Colombian Hospitals. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007;51:2001–2004. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00226-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Touati M, Diene SM, Racherache A, Dekhil M, Djahoudi A, Rolain JM. Emergence of blaOXA-23 and blaOXA-58 carbapenemase-encoding genes in multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii isolates from University Hospital of Annaba, Algeria. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2012;40:89–91. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2012.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mugnier P, Poirel L, Nordmann P. Functional analysis of insertion sequence ISAba1, responsible for genomic plasticity of Acinetobacter baumannii. J Bacteriol. 2009;191:2414–2418. doi: 10.1128/JB.01258-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aubert D, Naas T, Héritier C, Poirel L, Nordmann P. Functional characterization of IS1999, an IS4 family element involved in mobilization and expression of beta-lactam resistance genes. J Bacteriol. 2006;188(Supl 18):6506–6514. doi: 10.1128/JB.00375-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mazel D. Integrons agents of bacterial evolution. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2006;4:608–620. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ramírez MS, Stietz MS, Vilacoba E, Jeric P, Limansky AS, Catalano M. Increasing frequency of class 1 and 2 integrons in multidrug-resistant clones of Acinetobacter baumannii reveals the need for continuous molecular surveillance. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2011;37:175–177. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2010.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ramirez MS, Pineiro S, Centron D. Novel insights about class 2 integrons from experimental and genomic epidemiology. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54:699–706. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01392-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute . Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. Wayne, PA, USA: CLSI; 2013. Twenty-third Informational Supplement. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Manchanda V, Sanchaita S, Singh NP. Multidrug Resistant Acinetobacter. J Glob Infect Dis. 2010;2(3):291–304. doi: 10.4103/0974-777X.68538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vaneechoutte M, Dijishoorn L, Tjernberg I, Elaichouni A, de Vos P, Claeys G, Verschraegen G. Identification of Acinetobacter genomic species by amplified ribosomal DNA restriction analysis. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:11–15. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.1.11-15.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dijkshoorn L, Van Harsselaar B, Tjernberg I, Bouvet PJ, Vaneechoutte M. Evaluation of amplified ribosomal DNA restriction analysis for identification of Acinetobacter genomic species. Syst Appl Microbiol. 1998;21:33–39. doi: 10.1016/S0723-2020(98)80006-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kimura MA. Simple method for estimating evolutionary rates of base substitutions through comparative studies of nucleotide sequences. J Mol Evol. 1980;16:111–120. doi: 10.1007/BF01731581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol Biol Evol. 2011;28:2731–2739. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vaneechoutte M, Dijkshoorn L, Tjernberg I, Elaichouni A, de Vos P, Claeys G, Verschraegen G. Identification of Acinetobacter genomic species by amplified ribosomal DNA restriction analysis. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33(1):11–15. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.1.11-15.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sundsfjord A, Simonsen GS, Haldorsen BC, Haaheim SO, Hjelmevoll SO, Littauer P, Dahl KH. Genetic methods for detection of antimicrobial resistance. APMIS. 2004;112:815–837. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0463.2004.apm11211-1208.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Queenan AM, Bush K. Carbapenemases the versatile beta-lactamases. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2007;20:440–458. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00001-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Walsh TR, Toleman MA, Hryniewicz W, Bennett PM, Jones RN. Evolution of an integron carrying blaVIM-2 in Eastern Europe report from the SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Program. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2003;52:116–119. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkg299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cantón R, Oliver A, Coque TM. Varela M del C.Pérez-Díaz JC.Baquero F Epidemiology of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacter isolates in a spanish hospital during a 12-year period. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40(4):1237–1243. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.4.1237-1243.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chuang YC, Chang SC, Wang WK. High and Increasing Oxa-51 DNA Load Predict Mortality in Acinetobacter baumannii Bacteremia Implication for Pathogenesis and Evaluation of Therapy. Horsburgh MJ, ed. PLoS One. 2010;5(11):e14133. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Turton JF, Woodford N, Glover J, Yarde S, Kaufmann ME, Pitt TL. Identification of Acinetobacter baumannii by Detection of the blaOXA-51-like Carbapenemase Gene Intrinsic to This Species. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44(8):2974–2976. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01021-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Koeleman JG, Stoof J. Van Der Bijl MW.Vandenbroucke Grauls CM.Savelkoul PH Identification of epidemic strains of Acinetobacter baumannii by integrase gene PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 2001;39:8–13. doi: 10.1128/JCM.39.1.8-13.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gu B, Tong M, Zhao W, Liu G, Ning M, Pan S, Zhao W. Prevalence and Characterization of Class I Integrons among Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Acinetobacter baumannii Isolates from Patients in Nanjing, China. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45(1):241–243. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01318-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Falagas ME, Kolets PK, Bliziotis IA. The diversity of definitions of multidrug-resistant and pandrug-resistant (PDR) Acinetobacter baumannii and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Med Microbiol. 2006;55:1619–1629. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.46747-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.La Scola B, Bui LTM, Baranton G, Khamis A, Raoult D. Partial rpoB gene sequencing for identification of Leptospira species. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2007;263(2):142–147. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2006.00377.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Higgins PG, Dammhayn C, Hackel M, Seifert H. Global spread of carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2010;65:233–238. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkp428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Montero JC, Ortiz E, Fernandez T, Cayuela A, Marque J, García A. Acinetobacter baumannii ventilator-associated pneumonia epidemiological and clinical findings. Intensive Care Med. 2005;31:649–655. doi: 10.1007/s00134-005-2598-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Garnacho J, Ortiz C, Fernández E, Aldabo T, Cayuela A. Acinetobacter baumanni ventilator- associated pneumonia Epidemiological and clinical findings. Intensive Care Med. 2005;31:649–655. doi: 10.1007/s00134-005-2598-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cortes JA, Leal AL, Montañez AM, Buitrago G, Castillo JS, Guzman L. Frequency of microorganisms isolated in patients with bacteremia in intensive care units in Colombia and their resistance profiles. Braz j infect dis. 2013;17(3):346–352. doi: 10.1016/j.bjid.2012.10.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pinzón JO, Mantilla JR, Valenzuela EM, Fernández F, Álvarez CA, Osorio E. Molecular characterization of Acinetobacter baumannii isolations from a burns unit in a third level attention hospital in Bogotá. Infectio. 2006;10:71–78. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Martínez P, Mattar S. Imipenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii carrying the IsaBA1-BlaOXA-23, 51 and IsaB1-BlaaDC-7 genes in Monteria, Colombia. Braz J Microbiol. 2012;43(4):1274–1280. doi: 10.1590/S1517-83822012000400006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Organización Panamericana de Salud . Informe anual de la Red de Monitoreo de Vigilancia de la Resistencia a los Antibióticos. Washington, D.C: Organización Panamericana de la Salud; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Curcio D. Multidrug-resistant gram-negative bacterial infections Are you ready for the challenge? Curr Clin Pharmacol. 2014;9:27–38. doi: 10.2174/15748847113089990062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Boo TW, Walsh F, Crowley B. Molecular characterization of carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter species in an Irish university hospital predominance of Acinetobacter genomic species. J Med Microbiol. 2009;58(2):209–216. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.004911-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gales AC, Castanheira M, Jones RN, Sader HS. Antimicrobial resistance among Gram-negative bacilli isolated from Latin America results from SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Program (Latin America, 2008-2010) Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2012;73:354–360. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2012.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dijkshoorn L, Nemec A, Seifert H. An increasing threat in hospitals multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2007;5:939–951. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Karageorgopoulos DE, Kelesidis T, Kelesidis I, Falagas ME. Tigecycline for the treatment of multidrug-resistant (including carbapenem-resistant) Acinetobacter infections a review of the scientific evidence. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2008;62(1):45–55. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkn165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Poirel L, Nordmann P. Genetic structures at the origin of acquisition and expression of the carbapenem-hydrolyzing oxacillinase gene blaOXA-58 in Acinetobacter baumannii. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2006;50:1442–1448. doi: 10.1128/AAC.50.4.1442-1448.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hrenovica J, Durnb G, Goic-Barisicc I, Kovacicd A. Occurrence of an Environmental Acinetobacter baumannii Strain Similar to a Clinical Isolate in Paleosol from Croatia. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2014;80:2860–2866. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00312-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Poirel L, Nordmann P. Carbapenem resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii: mechanisms and epidemiology. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2006;12:826–836. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2006.01456.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]