Abstract

Objective Inconsistent links between posttraumatic stress symptoms (PTS) and posttraumatic growth (PTG) in youth following a stressful life event have been observed in previous literature. Latent profile analysis (LPA) provides a novel approach to examine the heterogeneity of relations between these constructs. Method Participants were 435 youth (cancer group = 253; healthy comparisons = 182) and one parent. Children completed measures of PTS, PTG, and a life-events checklist. Parents reported on their own PTS and PTG. LPA was conducted to identify distinct adjustment classes. Results LPA revealed three profiles. The majority of youth (83%) fell into two resilient groups differing by levels of PTG. Several factors predicted youth’s profile membership. Conclusions PTS and PTG appear to be relatively independent constructs, and their relation is dependent on contextual factors. The majority of youth appear to be resilient, and even those who experience significant distress were able to find benefit.

Keywords: childhood cancer, growth, life events, posttraumatic stress, profiles, resilience

Potentially traumatic events (PTE) are common during middle childhood and adolescence ( Copeland, Keeler, Angold, & Costello, 2007 ). Following a PTE, a small subset of youth (13.4%) experiences posttraumatic stress symptoms (PTS), with even fewer (<1%) meeting criteria for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD; Copeland et al., 2007 ). Childhood cancer has been examined as a PTE, with rates of PTS and PTSD in youth with cancer commensurate to those in healthy youth ( Kazak et al., 1997 ; Phipps, Jurbergs, & Long, 2009 ; Phipps et al., 2014 ). Thus, although a subset of youth experiences emotional distress following a trauma, variability exists between these responses, with resilience being the modal response ( Bonanno & Diminich, 2013 ).

PTEs also have the potential to alter preconceived schemas in positive ways, which may result in changes in life priorities, a greater sense of spiritual well-being, and stronger friend and family relations. These positive psychosocial changes have been referred to as posttraumatic growth (PTG; Tedeschi & Callhoun, 2004 ). Rates of PTG among adolescents also vary widely (30%–75%) following a PTE ( Laufer & Solomon, 2006 ; Milam, Ritt-Olson, Tan, Unger, & Nezami, 2005 ). These findings also extend to youth with cancer, with the majority of youth with cancer reporting at least one positive change resulting from their cancer experience ( Arpawong, Oland, Milam, Ruccione, & Meeske, 2013 ; Barakat, Alderfer, & Kazak, 2006 ; Phipps, Long & Ogden, 2007 ). Similar to rates of PTS following a PTE, PTG is experienced at various levels, suggesting heterogeneity in PTG responses.

It appears that youth’s response to their cancer diagnosis can be experienced with variable negativity (e.g., PTS) and positivity (e.g., PTG). Indeed, the extant literature on the relation between PTS and PTG has highlighted an inconsistent, or perhaps complex, relationship between the two constructs. Tedeschi and Calhoun (2004) suggested that PTG only develops from stress responses that serve to alter previously established schemas. Some evidence in youth with cancer supports the idea that PTS and PTG are positively linked to each other ( Barakat et al., 2006 ). However, other research has found a curvilinear relation between PTS and PTG ( Kleim & Ehlers, 2009 ), or a small or null relation ( Klosky et al., 2014 ; Michel, Taylor, Absolom, & Eiser, 2010 ; Phipps et al., 2007 ). The inconsistent link between PTS and PTG has led some to argue that PTS and PTG should be viewed as independent constructs, and attention should be paid to the variability in how the two constructs are related ( Linley & Joseph, 2004 ). Yet, little research has empirically examined the links between PTS and PTG in this way, particularly in pediatric populations.

Following a traumatic event, PTS has been associated with lower quality of life ( Alisic, Van der Schoot, van Ginkel, & Kleber, 2008 ) and decreased adherence to medical regimens ( Vranceanu et al., 2008 ). PTG has been linked to positive affect, less negative affect, and general life satisfaction ( Chaves, Vazquez, & Hervas, 2013 ). Given the link between PTS and PTG, prior research has focused on understanding factors that promote or inhibit youth’s growth and distress responses. Previous theoretical models of PTS and PTG provide a framework for understanding factors associated with these outcomes in youth ( Bruce, 2006 ; Meyerson, Grant, Carter, & Kilmer, 2011 ). The development of PTS and PTG is certainly complex, and current theory has noted the importance of premorbid characteristics, including demographic factors and prior stressful life events. Although these focus on individual factors, systemic and family functioning, particularly parental adjustment, also predict variability in youth’s adjustment ( Bruce, 2006 ; Kazak et al., 2004 ).

Demographic factors have been inconsistently linked to PTS and PTG. Gender, age, race, and socioeconomic status (SES) are sometimes positively related, negatively related, or not at all related to PTS and PTG ( Barakat et al., 2006 ; Bruce, 2006 ; Currier, Herman & Phipps., 2009 ; Phipps et al., 2007 ; Zebrack et al., 2012 ). Previous life stressors have emerged as an important and salient predictor of youth’s adjustment to future stressful life events. Cumulative lifetime adversity has been associated with incrementally poorer adjustment outcomes ( Brown, Madan-Swain, & Lambert, 2003 ; Currier, Jobe-Shields, & Phipps, 2009 ). However, prior lifetime adversity may act as a “vaccine” to current stressful life events and in some cases promote resilience. Seery, Holman, and Silver (2010) , suggested a “U”-shape relation between prior stressful life events and adjustment, noting that no adversity and high adversity predict poorer adjustment outcomes than moderate adversity, which promotes resilience. Thus, youth who have experienced moderate levels of adversity may adjust better than youth that have experienced minimal or high adversity.

Following the PTE of childhood cancer, parents must struggle to adjust and cope as well ( Kazak et al., 2004 ), and parental distress is predictive of child distress responses ( Clawson, Jurbergs, Lindwall, & Phipps, 2013 ; Magal-Vardi et al., 2004 ). Little research has examined the link between positive parental adjustment and youth’s positive adjustment. The extant literature in this area seems to suggest that positive parental adjustment is predictive of youth’s positive adjustment following a stressful life event ( Taylor, Larsen-Rife, Conger, Widaman, & Cutrona, 2010 ), which may translate to PTG.

The primary aim of this study was to explore the relation between PTS and PTG by examining if distinctive subgroups of youth exist based on their PTS and PTG patterns. Given inconsistent past findings, we anticipate that different profiles will emerge, highlighting unique relations between PTS and PTG; however, the nature of the relations is unclear. As a second aim, we examined whether youth with cancer differed from healthy comparisons in their profiles of PTS and PTG. Specifically, we examined if the profiles differed between youth with cancer reporting cancer as their most stressful event, youth with cancer reporting another event as their most stressful life event, and healthy comparisons reporting on their most stressful life event. Finally, we examined the role of demographic factors, prior stressful life events, parental PTS, and parent PTG in predicting youth’s profile membership. We anticipate that moderate levels of previous stressful life events will be indicative of better outcomes than low or high levels of previous stressful life events ( Seery et al., 2010 ). Further, we hypothesize that parental PTS and PTG responses will be associated with youth’s PTS and PTG responses.

Method

Participants

Participants included 435 children and adolescents (patient participants n = 253). One primary caregiver of each child and adolescent also participated (mother, 85%; father, 12%; other adult participant, 3%). Youth participants ranged in age from 8 to 17 years ( M = 12.41, SD = 2.91), and nearly half were female (49%). The sample was predominately White (72%; 22% Black; 6% other). Using the Barratt Simplified Measure of Social Status ( Barratt, 2006 ), the sample was predominately middle class ( M = 3.07, SD = 1.20; range = 1–5). Demographic and medical information is presented in Table I . Patient participants and healthy comparison participants did not significantly differ based on age, gender, or ethnicity; however, the groups significantly differed in SES, with fewer healthy comparisons falling into lower SES categories (χ 2 (4, n = 435) = 10.77, p = .03).

Table I.

Demographic Information Across Study Group

| Patient group | Control group | |

|---|---|---|

| Variable | n = 253 | n = 182 |

| Gender | ||

| % Female | 48.6 | 51.1 |

| % Male | 51.4 | 48.9 |

| Age | ||

| Mean ( SD ) | 12.61 (2.88) | 12.14 (2.94) |

| Range | 8–17 | 8–17 |

| Race | ||

| % White | 72.7 | 74.2 |

| % Black | 22.5 | 22.5 |

| % Other | 4.8 | 3.3 |

| SES* | ||

| % Group 1 | 12.3 | 12.1 |

| % Group 2 | 15.1 | 23.6 |

| % Group 3 | 32.1 | 31.9 |

| % Group 4 | 23.8 | 24.7 |

| % Group 5 | 16.7 | 7.7 |

Medical information for patient participants ( n = 255).

Diagnosis

% Acute lymphoblastic leukemia 24.1

% Other leukemia 6.3

% Hodgkin’s and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma 13.4

% Solid tumor 38.7

% Brain tumor 17.5

Procedure

Patients were recruited from outpatient cancer clinics of a major children’s hospital, hospital as a part of a larger longitudinal study examining stress, adjustment, and growth in children and families with children who have been diagnosed with cancer. Participants were eligible if they were (a) aged 8–17 years; (b) at least 1-month from diagnosis, (c) able to speak and read English, and (d) did not have any significant cognitive or sensory deficit that would preclude completion of study measures. Patient participants were recruited from outpatient clinics stratified by time from their cancer diagnosis (1–6 months; 6–24 months; 2–5 years; >5 years). A total of 378 children with cancer were approached regarding participation in the study, and 258 (68%) agreed to participate. Five patients’ responses were subsequently found to be inevaluable, leaving a final sample of 253. Participants and nonparticipants did not differ by age, gender, or race/ethnicity, diagnostic category, or time since diagnosis.

Healthy comparison participants were recruited from schools in a three-state area surrounding the hospital. Permission slips were distributed through the schools, and returned permission slips included information on child age, gender, race/ethnicity, and parental education and occupation. The returned data were used to create a pool of potential control participants, who were subsequently contacted, based on frequency matching according to demographics. Participants were eligible if they were (a) 8–17 years of age; (b) able to speak and read English, (c) did not have any significant cognitive or sensory deficits, and (d) did not have a history of chronic or life-threatening illness. Participation rate in the healthy comparison sample was 86%. All procedures were approved by the hospital institutional review board, and informed consent/assent was obtained from all participants.

Measures

Youth PTS

The UCLA PTSD Reaction Index for DSM-IV ( Pynoos, Rodriguez, Steinberg, Stuber, & Frederick, 1998 ) is a 22-item measure assessing PTS in youth according to DSM-IV criteria. Youth self-identified the most traumatic stressful event they had experienced and answered questions regarding that event on the frequency of symptoms they have experienced during the past month (rated from 0 = none of the time to 4 = most of the time ). Youth with cancer reported a cancer-related event ( n = 134) or a non-cancer-related event ( n = 119) as their most stressful. The measure has excellent psychometric properties including high internal and test–retest reliability ( Steinberg, Brymer, Decker, & Pynoos, 2004 ). Only the overall score was used in the present study (α = .90).

Youth PTG

The Benefit Finding/Burden Scale for Children ( Currier, Hermes, & Phipps, 2009 ; Phipps et al., 2007 ) is a 20-item measure assessing children’s perceptions of positive and negative effects of a traumatic experience. The benefit subscale was used in this study. Youth were asked to respond on a 5-point scale from “ Not at all ” to “ Very Much ” the degree to which they have experienced positive changes as a result of the same traumatic experience they identified on the UCLA child-report measure. The benefit subscale evidenced good internal reliability (benefit α = .89).

Life Events

Youth completed the Life Events Scale ( Johnston, Steele, Herrera, & Phipps, 2003 ), a modified version of the Coddington Life Events Questionnaire ( Coddington, 1972 ). The measure is composed of events that have been identified as meeting A1 criteria from the DSM-IV, as well as other events that do not meet A1 criteria, but might be expected to have a significantly stressful impact (e.g., parental divorce). Previous research using this sample has found both A1 and non-A1 criteria to be associated with PTS ( Willard, Long, & Phipps, 2015 ). The total number of events experienced was summed for the present study.

Parental Posttraumatic Stress and Growth

Impact of Events Scale, Revised (IES-R; Weiss, 2004 ) is a 22-item measure of PTS symptoms based on DSM-IV criteria. Parents report on their experience within the past 7 days associated with the event identified as the most traumatic in their lives. It has adequate internal reliability and test–retest reliability ( Weiss, 2004 ). In the present study, the sum of all the items was used as a total indicator of the distress associated with the event identified as most traumatic by the parents. This measure also evidenced adequate internal consistency (α = .94).

The Benefit Finding Scale (BFS; Antoni et al., 2001 ) is a 17-item BFS in which participants were asked to respond on a 5-point scale, from “ Not at all ” to “ Very Much ” the degree to which they have experienced change (e.g., “Has led me to be more accepting of things,” “Has brought my family closer”) in response to the traumatic event the parent identified in the IES-R. A total score was used for the BFS (α = .92).

Statistical Analyses

For the preliminary analyses, the sample was separated into: youth with cancer reporting cancer as their most stressful event, youth with cancer reporting a non-cancer event as most stressful, and healthy comparisons. Correlations between PTS and PTG were examined separately for each group. Fischer r to z transformations were performed to determine whether the association between PTS and PTG differed between each group.

Latent Profile Analyses were conducted using Mplus 7.3 ( Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2014 ) to empirically derive profiles of adjustment. Latent profile analysis (LPA) is a person-centered analytic technique that derives classes (i.e., subgroups) of individuals based on similar characteristic patterns (profiles) that differentiate homogeneous subgroups within the heterogeneous sample ( Berlin, Williams, & Parra, 2013 ). Several indices were used to determine the optimal fit of the data: Bayesian information criterion (BIC; Schwartz, 1978 ), with lower values indicating better fit; entropy values, with values closer to 1 indicating greater accuracy ( Berlin et al., 2013 ); the Lo–Mendell–Rubin test (LMR; Lo, Mendell, & Rubin, 2001 ) and the Bootstrap Likelihood Ratio Test (BLRT; McLachlan & Peel, 2000 ), which indicate whether adding a class significantly improves model fit to the data. To determine whether the profiles were related to children’s demographic factors, stressful life events, and parental adjustment (PTS and PTG), the three-step approach was used to compare identified classes on these variables ( Asparouhov & Muthén, 2014 ).

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Descriptive statistics for the study variables are provided in Table II . Correlation analyses between PTS and PTG were performed separately for the entire sample, youth with cancer reporting cancer as their most stressful event, youth with cancer reporting another event as their most stressful event, and healthy comparisons. Variability emerged in correlation size between the groups (entire sample, r = .17, p < .001; youth with cancer reporting on cancer, r = .15, p = .08; youth with cancer reporting a non-cancer event r = .26, p < .01; healthy comparisons, r = .20, p < .01). A Fisher r-to- z transformation was used to compare PTS and PTG correlations between the three groups, and no significant differences were observed.

Table II.

Means and Standard Deviation of Study Variables for the Entire Sample

| Measure | Mean | SD | Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Child-PTS | 18.67 | 14.34 | 0.0–76.0 |

| Child-PTG | 27.76 | 10.42 | 10.00–50.00 |

| Parent-PTS | 23.26 | 17.80 | 0.00–85.00 |

| Parent-PTG | 63.76 | 13.82 | 17.00–85.00 |

| Child #life events | 7.26 | 3.44 | 0.00–21.00 |

Note . N = 435. PTS = Child-PTS = child-reported posttraumatic stress symptoms; Child-PTG = child-reported posttraumatic growth symptoms, Parent-PTS = reported posttraumatic stress symptoms; Parent-PTG = parent-reported posttraumatic growth symptoms; Child # Life events = number of stressful life events endorsed by the child participant.

Primary Analyses

Overall, a three-class LPA model provided the best fit to the data ( Table III ). The three-class model provided a smaller BIC than the two-class model, and the LMR and BLRT indicated significant improvement in fit with the addition of a third class over a two-class model. Although the four-class model provided a slightly more preferable BIC and significant BLRT, the four-class model produced a nonsignificant LMR value. Nylund, Asparouhov, & Muthén (2007) recommend stopping the addition of classes when the LMR becomes nonsignificant. As such, the three-class model was retained.

Table III.

Comparison of Model Fit for Latent Profile Analyses

| Classes per model | Bayesian information criteria | Entropy | Lo–Mendell–Rubin test p -value | Bootstrap likelihood ratio test p -value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 2406.87 | .85 | .0000 | .0000 (1 vs. 2 classes) |

| 3 | 2387.13 | .72 | .0044 | .0000 (2 vs. 3 classes) |

| 4 | 2372.13 | .74 | .1692 | .0000 (3 vs. 4 classes) |

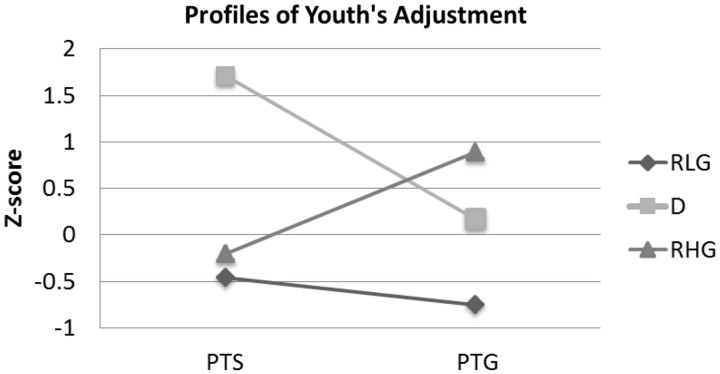

The majority of the youth in this study fell into resilient profiles, with 47% falling into a “resilient low growth” (RLG) profile, 36% falling into a “resilient high-growth” (RHG) profile, and 17% falling into a distressed (D) profile, while showing intermediate levels of growth ( Figure 1 ). To confirm that differences among classes were driven by multiple constructs and not a unitary variable, mean differences across profiles for each indicator were examined by creating additional copies of the indicators and treating them as auxiliary variables ( Berlin et al., 2013 ). Profiles differed on mean levels of PTS (RLG vs. RHG, χ 2 = 11.74, p < .01; RLG vs. D, χ 2 = 428.34, p < .001; RHG vs. D, χ 2 = 311.40, p < .001) and on PTG (RLG vs. RHG, χ 2 = 447.87, p < .001; RLG vs. D, χ 2 = 64.60, p < .001; RHG vs. D, χ 2 = 33.02, p < .001). Approximately 64% of the participants in the D group obtained PTSS scores above the clinically significant cutoff of 38, whereas none of the participants in the RHG or RLG group obtained scores >38.

Figure 1.

Latent profiles of children’s PTS and PTG. Note . PTS = posttraumatic stress symptoms; PTG = posttraumatic growth; RLG = resilient, low growth; RHG = resilient high growth; D = distressed.

As noted previously, youth were classified into one of three categories, youth with cancer reporting cancer as their most stressful event, youth with cancer reporting a non-cancer-related event as the most stressful life event, and healthy comparisons. Chi-square analyses revealed that youth’s event category significantly differentiated class membership (χ 2 (4, n = 435) = 31.84, p < .001; φ = .27; see Table IV ). Youth with cancer and the healthy comparison groups had a similar proportion of youth identified as resilient. Youth with cancer reporting a non-cancer event and healthy comparison youth had similar profiles, with the majority falling in the RLG class. Youth with cancer reporting a cancer event were distinct based on their level of perceived growth, with a higher proportion in the RHG class, and lower proportion in the RLG class relative to the other groups.

Table IV.

Percentage of Participant Groups Falling Into Adjustment Profiles

| Profile |

Type of event

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Cancer: reporting cancer event | Cancer: reporting non-cancer event | Healthy comparisons | |

| Resilient-high-growth | 54% ( n = 73) | 24% ( n = 28) | 29% ( n = 53) |

| Resilient-low-growth | 33% ( n = 44) | 56% ( n = 67) | 52% ( n = 95) |

| Distressed | 13% ( n = 17) | 20% ( n = 24) | 19% ( n = 34) |

| Total | 100% ( n = 134) | 100% ( n = 119) | 100% ( n = 182) |

Predictors of Child Adjustment Profiles

Demographic Predictors of Classes

Participants in each class did not differ based on gender, SES, or race. Youth in the RHG class were older than youth in the RLG class (odds ratio = 1.21, z = 3.79, p < .001; RHG age M = 13.48, SD = 2.83; RLG age M = 11.59, SD = 2.63) and the D class (odds ratio = 1.17, z = 2.64, p < .001; D age M = 12.47, SD = 3.15).

Stressful Life Events

Regarding cumulative stressful life events, youth in the RLG class reported fewer stressful life events than in the RHG class (odds ratio = 1.10; z = 2.09, p < .001; RLG, M = 6.23, SD = 3.01; RHG, M = 7.68, SD = 3.19) and D class (odds ratio = 1.30, z = −5.03, p < .001; D M = 12.47, SD = 3.15). Youth in the D class also reported more stressful life events than youth in the RHG group as well (odds ratio = 0.85; z = −3.31, p < .01).

Parental Adjustment

Profile membership did not differ based on parental PTS. However, membership differed according to parent benefit-finding. Specifically, parents of youth in the RHG class endorsed more benefit-finding than youth in the RLG class (odds ratio = 1.03, z = −.03, p < .05; RLG M = 61.56, SD = 14.43; RHG M = 66.72, SD = 13.04).

Discussion

Prior research has demonstrated heterogeneity in youth’s adjustment following a PTE, as well as the variability in the relation between PTS and psychological growth (PG) ( Linley & Joseph, 2004 ). The current findings suggest that, despite a small, but significant, positive correlation between PTS and PTG, they are more appropriately viewed as relatively independent constructs, and their relation depends on the context in which they are being examined. The presence of a substantial subset of youth reporting low levels of PTS and high levels of PTG suggests that the experience of PTS is not a necessary precursor to the development of PG following PTE. Conversely, higher levels of PTS do not preclude the development of growth, as even the most distressed group in the sample experienced moderate levels of PTG.

Perhaps the most striking finding of the study is the high level of resilience observed, as the overwhelming majority (83%) of youth fell into a class that was characterized by low PTS. This is consistent with the findings of Bonanno and others ( Bonanno & Diminich, 2013 ) that minimal impact resilience is the modal response to most PTE’s, and suggests that such resilience may be even more common in children ( Masten, 2014 ). The term PTG may be applicable to only a small subset of those reporting growth, and an alternative, such as “challenge-related growth” may be more appropriate and applicable. We use the more generic, PG in reference to this outcome for the remainder of the discussion.

In addition to examining PTS and PG from a multidimensional framework, we sought to examine factors associated with youth’s membership within a particular profile. Youth identifying cancer as their most stressful life event were more likely to evidence both resilience and positive growth compared with youth with cancer reporting a non-cancer event and healthy comparisons. This suggests that within the context of cancer, youth are more likely to experience growth without experiencing PTS. This perhaps could be attributable to the unique aspects of the cancer experience and/or the specialized multidisciplinary services received at most major pediatric oncology units. Also, there is not a group reporting distress in the absence of growth. It is noteworthy that even the distress group is reporting moderate levels of growth, pointing to the ability of children to find benefit even in the context of distress.

We examined the role of demographics, prior stressful life events, and parent adjustment as potential risk and protective factors that could influence the profiles of PTS and PG. Consistent with some prior research ( Bruce, 2006 ; Currier et al., 2009 ; Phipps et al., 2007 ), demographic factors were not associated with youth’s adjustment profile with the exception of age. Youth within the RLG group were younger than youth in the RHG and D classes. This may be because PTG requires a change in one’s preexisting schemas ( Tedeschi & Calhoun, 2004 ), which are less likely to be established in younger children.

A history of stressful life events has been shown to both exacerbate and protect individuals from experiencing distress following a PTE ( Seery et al., 2010 ). That is, too few or too many stressful life events can intensify distressful emotional responses following a PTE, but a moderate amount can serve to increase one’s capacity to cope with life challenges. Consistent with what might be expected based on Seery’s work, we found those reporting the highest levels of cumulative life events were likely to belong to the D group. However, children reporting intermediate levels of cumulative life events reported low distress, but interestingly, they also reported better functioning in terms of PG. This suggests that moderate levels of adverse life events may be associated with overall better adjustment outcomes. Future research should examine possible curvilinear relations between PTE and PG in this setting.

Prior research has highlighted the predictive link between parental adjustment and youth’s adjustment to stressful life events, including childhood cancer ( Clawson et al., 2013 ; Magal-Vardi et al., 2004 ). Surprisingly, parental PTS did not predict child adjustment. However, higher levels of benefit-finding were reported by parents of youth in the RHG group, which suggests that parents’ ability to make meaning of and find positive benefit from an adverse event may foster similar abilities in their children. Little research exists on the link between positive parental adjustment and youth’s adjustment following a PTE. Perhaps parents are facilitating these strategies through modeling and conversations about adverse events ( Eisenberg, Cumberland, & Spinrad, 1998 ).

The present findings should be considered in light of some limitations and areas for future research. The cross-sectional and correlational design limits the ability to examine causal conclusions and generalization of these findings. Resilience and growth are best studied longitudinally ( Bonano & Diminich, 2013 ), thus future research should examine risk and protective factors as they relate to adjustment over time. Further, adjustment to stressful life events spans across multiple domains (school, neighborhood, etc.), and a comprehensive assessment would include additional constructs not examined in the present research. Also, little is known about the transactional nature between positive parental adjustment and youth positive adjustment. As highlighted in the present study, parental PG is linked to youth experiences of low PTS and high PG. Examining this pattern between parents and youth may be a fruitful avenue to explore in future research. Finally, the study was designed before the release of the DSM-V ( APA, 2013 ), and PTS assessments were based on the DSM-IV criteria. Given notable changes in criteria, future research is required to replicate these findings based on currently recognized symptom clusters and diagnostic criteria.

In sum, the results provide a novel examination of the complex interplay between PTS and PTG following stressful life events, and suggest independence between the two constructs. Notably, most youth appear to be resilient and experience low levels of distress following an adverse event. Yet, even youth who experience significant emotional distress are able to find benefit from their experience.

Funding

Supported in part by NIH R01 CA136782, and by the American Lebanese-Syrian Associated Charities (ALSAC).

Conflicts of interest : None declared.

References

- Alisic E., Van der Schoot T. A., van Ginkel J. R., Kleber R. J. ( 2008. ). Looking beyond posttraumatic stress disorder in children: Posttraumatic stress reactions, posttraumatic growth, and quality of life in a general population sample . Journal of Clinical Psychiatry , 69 , 1455 – 1461 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association . ( 2013. ). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders ( 5th ed. ). Washington, DC: : American Psychiatric Association; . [Google Scholar]

- Antoni M. H., Lehman J. M., Kilbourn K. M., Boyers A. E., Culver J. L, Alferi S. M., Yount S. E., McGregor B. A., Arena P. L., Harris S. D., Price A. A., Carver C. S. ( 2001. ). Cognitive-behavioral stress management intervention decreases the prevalence of depression and enhances benefit finding among women under treatment for early-stage breast cancer . Health Psychology , 20 , 20 – 32 . Doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.20.1.20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arpawong T. E., Oland A., Milam J. E., Ruccione K., Meeske K. A. ( 2013. ). Post-traumatic growth among an ethnically diverse sample of adolescent and young adult cancer survivors . Psycho-Oncology , 22 , 2235 – 2244 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asparouhov T., Muthen B. ( 2014. ). Auxiliary variables in mixture modeling: A 3-step approach using Mplus . Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal , 21 , 329 – 341 . doi 10.1080/10705511.2014.915181 [Google Scholar]

- Barakat L. P., Alderfer M. A., Kazak A. E. ( 2006. ). Posttraumatic growth in adolescent survivors of cancer and their mothers and fathers . Journal of Pediatric Psychology , 31 , 413 – 419 . doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsj058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barratt W. ( 2006. ). The Barratt Simplified Measure of Social Status (BSMSS) Measuring SES, Unpublished manuscript, Indiana State University, Retrieved from http://wbarratt.indstate.edu/socialclass/Barratt_Simplified_Measure_of_Social_Status.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Berlin K. S., Williams N. A., Parra G. R. ( 2013. ). An introduction to latent variable mixture modeling (part 1): Overview and cross-sectional latent class and latent profile analyses . Journal of Pediatric Psychology , 39 , 174 – 187 . doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jst084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno G. A., Diminich E. D. ( 2013. ). Annual research review: Positive adjustment to adversity-trajectories of minimal impact resilience and emergent resilience . Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry , 54 , 378 – 401 . doi: 10.1111/jccp.12021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce M. ( 2006. ). A systematic and conceptual review of posttraumatic stress in childhood cancer survivors and their parents . Clinical Psychology Review , 26 , 233 – 256 . doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2005.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown R. T., Madan-Swain A., Lambert R. ( 2003. ). Posttraumatic stress symptoms in adolescent survivors of childhood cancer and their mothers . Journal of Traumatic Stress , 16 , 309 – 318 . doi: 10.1023/A:1024465415620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaves C., Vazquez C., Hervas G. ( 2013. ). Benefit finding and well-being in children with life threatening illnesses: An integrative study . Terapia PsicolÓgica , 31 , 59 – 68 . [Google Scholar]

- Clawson A. H., Jurbergs N., Lindwall J., Phipps S. ( 2013. ). Concordance of parent proxy report and child self-report of posttraumatic stress in children with cancer and healthy children: influence of parental posttraumatic stress . Psycho-Oncology , 22 , 2593 – 2600 . doi: 10.1002/pon.3321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coddington R. D. ( 1972. ). The significance of life events as etiologic factors in the diseases of children. II. A study of a normal population . Journal of Psychosomatic Research , 16 , 205 – 213 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copeland W. E., Keeler G., Angold A., Costello E. J. ( 2007. ). Traumatic events and posttraumatic stress in childhood . Archives of General Psychiatry , 64 , 577 – 584 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Currier J. M., Hermes S., Phipps S. ( 2009. ). Brief report: Children's response to serious illness: Perceptions of benefit and burden in a pediatric cancer population . Journal of Pediatric Psychology , 34 , 1129 – 1134 . doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsp021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Currier J. M., Jobe-Shields L. E., Phipps S. ( 2009. ). Stressful life events and posttraumatic stress symptoms in children with cancer . Journal of traumatic stress , 22 , 28 – 35 . doi: 10.1002/jts.20382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N., Cumberland A., Spinrad T. L. ( 1998. ). Parental socialization of emotion . Psychological Inquiry , 9 , 241 – 273 . doi:10.1207/s15327965pli0904_1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston C. A., Steele R. G., Herrera E. A., Phipps S. ( 2003. ). Parent and child reporting of negative life events: Discrepancy and agreement across pediatric samples . Journal of Pediatric Psychology , 28 , 579 – 588 . doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsg048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazak A., Barakat L., Meeske K., Christakis D., Meadows A., Casey R., Penati B., Stuber M. L. ( 1997. ). Posttraumatic stress, family functioning, and social support in survivors of childhood leukemia and their mothers and fathers . Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology , 65 , 120.– . 10.1037/0022-006X.65.1.120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazak A. E., Alderfer M., Rourke M. T., Simms S., Streisand R., Grossman J. R. ( 2004. ). Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and posttraumatic stress symptoms (PTSS) in families of adolescent childhood cancer survivors . Journal of Pediatric Psychology , 29 , 211 – 219 . doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsh022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleim B., Ehlers A. ( 2009. ). Evidence for a curvilinear relationship between posttraumatic growth and posttrauma depression and PTSD in assault survivors . Journal of Traumatic Stress , 22 , 45 – 52 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klosky J. L., Krull K. R., Kawashima T., Leisenring W., Randolph M. E., Zebrack B., Stuber M. L., Robison L. L., Phipps S. ( 2014. ). Relations between posttraumatic stress and posttraumatic growth in long-term survivors of childhood cancer: A report from the childhood cancer survivor study . Health Psychology , 33 , 8787 – 8882 . doi:10.1037/hea0000076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laufer A., Solomon Z. ( 2006. ). Posttraumatic symptoms and growth among Israeli youth exposed to terror incidents . Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology , 25 , 429 – 447 . [Google Scholar]

- Linley P. A., Joseph S. ( 2004. ). Positive change following trauma and adversity: Areview . Journal of Traumatic Stress , 17 , 11 – 21 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo Y., Mendell N. R., Rubin D. B. ( 2001. ). Testing the number of components in a normal mixture . Biometrika , 88 , 767 – 778 . doi: 10.1093/biomet/88.3.767 [Google Scholar]

- Magal-Vardi O., Laor N., Toren A., Strauss L., Wolmer L., Bielorai B., Rechavi G., Toren P. ( 2004. ). Psychiatric morbidity and quality of life in children with malignancies and their parents . The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease , 192 , 872 – 875 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masten A. S. ( 2014. ). Ordinary magic: Resilience in development . New York, NY: : Guilford Press; . [Google Scholar]

- McLachlan G., Peel D. ( 2000. ). Finite mixture models . New York, NY: : Wiley; . [Google Scholar]

- Meyerson D. A., Grant K. E., Carter J. S., Kilmer R. P. ( 2011. ). Posttraumatic growth among children and adolescents: A systematic review . Clinical Psychology Review , 31 , 949 – 964 . doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2011.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén L., Muthén B. ( 1998-2014. ). Mplus user’s guide ( 5th ed. ). Los Angeles, CA: : Muthén & Muthén; . [Google Scholar]

- Michel G., Taylor N., Absolom K., Eiser C. ( 2010. ). Benefit finding in survivors of childhood cancer and their parents: Further empirical support for the Benefit Finding Scale for Children . Child: Care, Health and Development , 36 , 123 – 129 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milam J., Ritt-Olson A., Tan S., Unger J., Nezami E. ( 2005. ). The September 11th 2001 Terrorist Attacks and Reports of Posttraumatic Growth among a Multi-Ethnic Sample of Adolescents . Traumatology , 11 , 233 . [Google Scholar]

- Nylund K. L., Asparouhov T., Muthén B. O. ( 2007. ). Deciding on the number of classes in latent class analysis and growth mixture modeling: A Monte Carlo simulation study . Structural Equation Modeling , 14 , 535 – 569 . doi:10.1080/10705510701575396 [Google Scholar]

- Phipps S., Jurbergs N., Long A. ( 2009. ). Symptoms of posttraumatic stress in children with cancer: Does personality trump health status? Psychooncology , 18 , 992 – 1002 . doi:10.1002/pon.1496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phipps S., Klosky J. L., Long A., Hudson M. M., Huang Q., Zhang H. ( 2014. ). Posttraumatic stress and psychological growth in children with cancer: Has the traumatic impact of cancer been overestimated? Journal of Clinical Oncology , 32 , 641 – 646 . doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.49.8212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phipps S., Long A. M., Ogden J. ( 2007. ). Benefit finding scale for children: Preliminary findings from a childhood cancer population . Journal of Pediatric Psychology , 32 , 1264 – 1271 . doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsl052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pynoos R., Rodriguez N., Steinberg N., Stuber M., Frederick C. ( 1998. ). UCLA PTSD Index for DSMIV , Unpublished manual, UCLA Trauma Psychiatry Service . [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz G. ( 1978. ). Estimating the dimension of a model . The Annals of Statistics , 6 ( 2 ), 461 – 464 . [Google Scholar]

- Seery M.D., Holman E.A., Silver R.C. ( 2010. ). Whatever does not kill us: Cumulative lifetime adversity, vulnerability, and resilience . Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , 99 , 1025 – 1041 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg A. M., Brymer M. J., Decker K. B., Pynoos R. S. ( 2004. ). The University of California at Los Angeles post-traumatic stress disorder reaction index . Current Psychiatry Reports , 6 , 96 – 100 . doi: 10.1007/s11920-004-0048-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor Z. E., Larsen-Rife D., Conger R. D., Widaman K. F., Cutrona C. E. ( 2010. ). Life stress, maternal optimism, and adolescent competence in single mother, African American families . Journal of Family Psychology , 24 , 468 . doi: 10.1037/a0019870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tedeschi R. G., Calhoun L. G. ( 2004. ). Posttraumatic Growth: Conceptual Foundations and Empirical Evidence . Psychological Inquiry , 15 ( 1 ), 1 – 18 . doi: 10.1207/s15327965pli1501_01 [Google Scholar]

- Vranceanu A. M., Safren S. A., Lu M., Coady W. M., Skolnik P. R., Rogers W. H., Wilson I. B. ( 2008. ). The relationship of post-traumatic stress disorder and depression to antiretroviral medication adherence in persons with HIV . AIDS patient care and STDs , 22 , 313 – 321 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss D. S. ( 2004. ). The impact of event scale-revised . In Wilson J. P., Keane T. M. (Eds.), Assessing psychological trauma and PTSD: A practitioner’s handbook ( 2nd ed , pp. 168 – 189 ). New York, NY: : Guilford Press; . doi:10.1016/j.jad.2009.09.019 [Google Scholar]

- Willard V. W., Long A., Phipps S. ( 2015. ). Life stress versus traumatic stress: The impact of life events on psychological functioning in children with and without serious illness . Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy . Advance online publication. 10.1037/tra0000017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zebrack B. J., Stuber M. L., Meeske K. A., Phipps S., Krull K. R., Liu Q., Yasui Y., Parry C., Hamilton R., Robison L. L., Zeltzer L. K. ( 2012. ). Perceived positive impact of cancer among long-term survivors of childhood cancer: A report from the childhood cancer survivor study . Psycho-Oncology , 21 , 630 – 639 . doi: 10.1002/pon.1959 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]